Submitted:

15 January 2026

Posted:

16 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

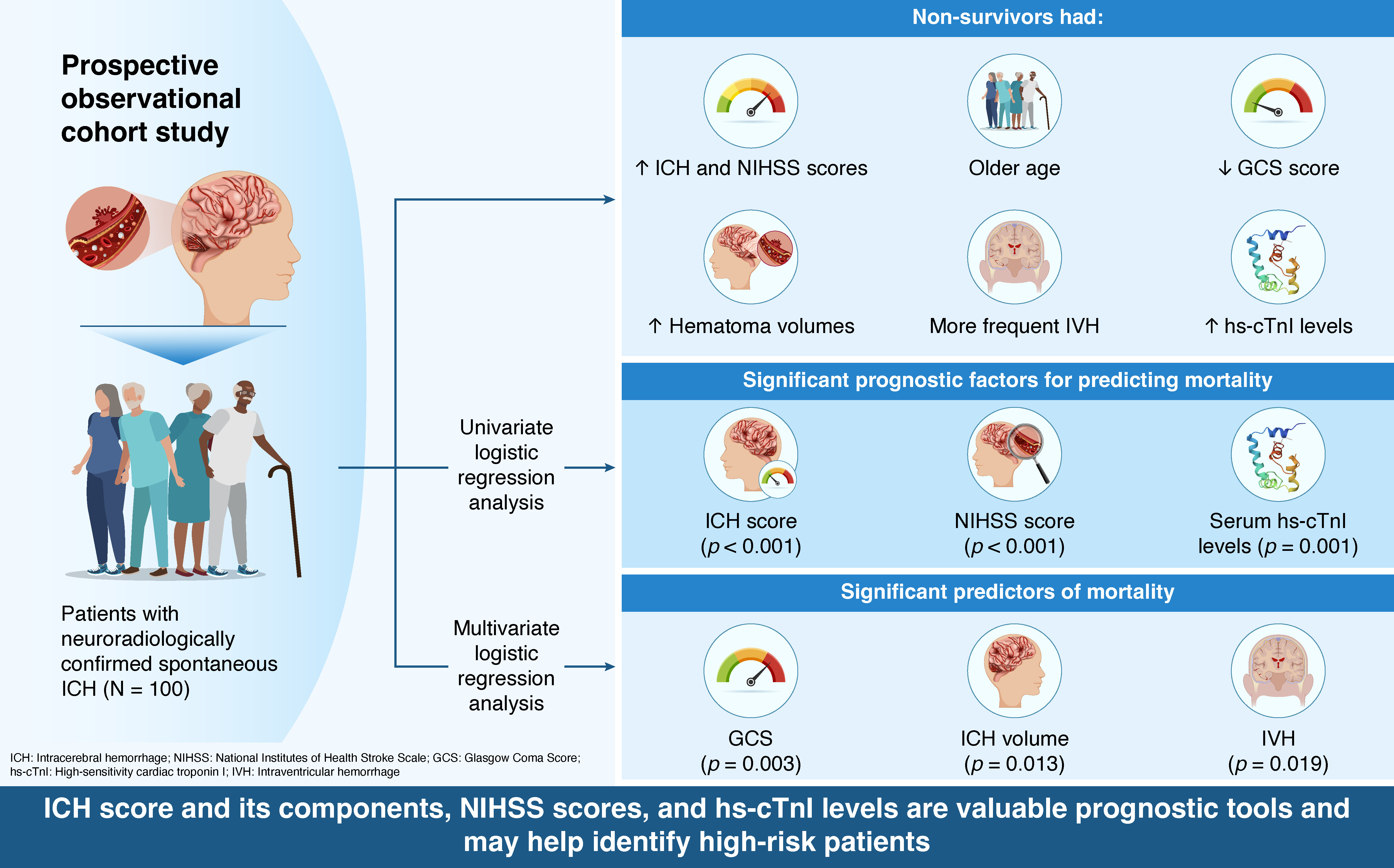

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Outcome-Based Comparison of Clinical and Radiological Parameters

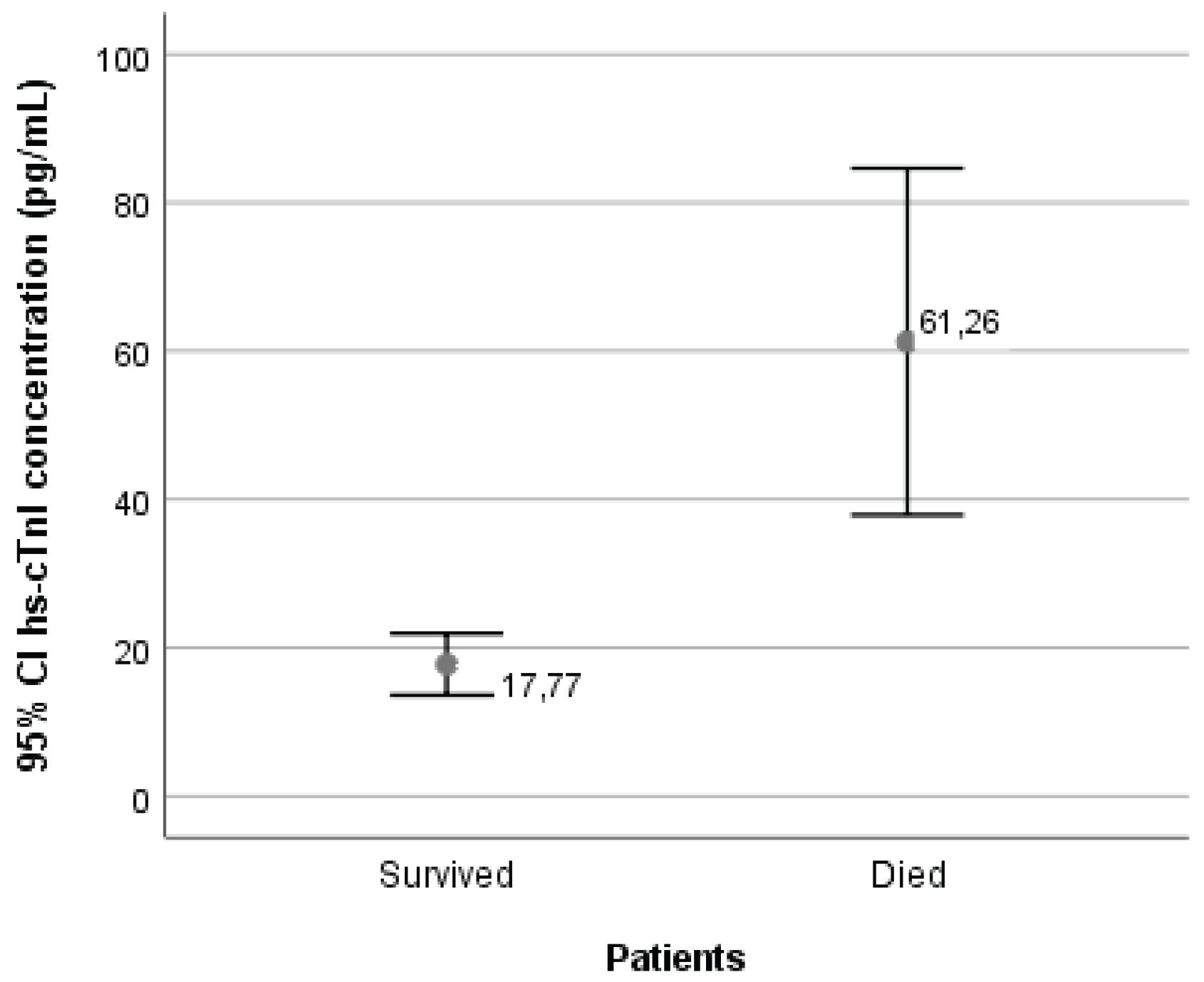

3.2. Serum Concentrations of High-Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin I

3.3. Correlation Values

3.4. Predictors of Mortality

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| cTn | Cardiac troponin |

| GCS | Glasgow Coma Scale |

| hs-cTnI | High-sensitivity cardiac troponin I |

| ICH | Intracerebral hemorrhage |

| IVH | Intraventricular hemorrhage |

| NIHSS | National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale |

| sICH | Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage |

| UHC | University Hospital Center |

References

- Al-Shahi Salman, R.; Frantzias, J.; Lee, R.J.; Lyden, P.D.; Battey, T.W.K.; Ayres, A.M.; Goldstein, J.N.; Mayer, S.A.; Steiner, T.; Wang, X.; et al. Absolute risk and predictors of the growth of acute spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient dana. Lancet Neurol 2018, 17, 885–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feigin, V.L.; Lawes, C.M.M.; Bennett, D.A.; Barker-Collo, S.L.; Parag, V. Worldwide stroke incidence and early case fatality reported in 56 population-based studies: a systematic review. Lancet Neurol 2009, 8, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Asch, C.J.; Luitse, M.J.; Rinkel, G.J.; van der Tweel, I.; Algra, A.; Klijn, C.J. Incidence, case fatality, and functional outcome of intracerebral haemorrhage over time, according to age, sex, and ethnic origin: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol 2010, 9, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.J.; Kim, T.J.; Yoon, B.W. Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Clinical Features of Intracerebral Hemorrhage: An Update. J Stroke 2017, 19, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariesen, M.J.; Claus, S.P.; Rinkel, G.J.; Algra, A. Risk factors for intracerebral hemorrhage in the general population: a systematic review. Stroke 2003, 34, 2060–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, M. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy: emerging concepts. J Stroke 2015, 17, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hostettler, I.C.; Seiffge, D.J.; Werring, D.J. Intracerebral hemorrhage: an update on diagnosis and treatment. Expert Rev Neurother 2019, 19, 679–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, R.; Biller, J. Recent advances in spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. F1000Res 2019, 8, F1000 Faculty Rev–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.S.; Hsieh, C.F.; Chau, T.T.; Yang, C.D.; Chen, Y.W. Risk factors of in-hospital mortality of intracerebral hemorrhage and comparison of ICH scores in a Taiwanese population. Eur Neurol 2011, 66, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Wu, L.; Song, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Kuang, H.; Zhu, Y.; Zeng, C.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, H.; Xu, Z.; et al. Hematoma, Perihematomal Edema, and Total Lesion Predict Outcome in Patients With Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Brain Behav 2025, 15, e70340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyagi, T.; Koga, M.; Yamagami, H.; Okuda, S.; Okada, Y.; Kimura, K.; Shiokawa, Y.; Nakagawara, J.; Furui, E.; Hasegawa, Y.; et al. Reduced estimated glomerular filtration rate affects outcomes 3 months after intracerebral hemorrhage: the stroke acute management with urgent risk-factor assessment and improvement-intracerebral hemorrhage study. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2015, 24, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Zhang, Q.; Xia, Z.; Cui, W.; Guo, J. Predictors of poor outcomes in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage. Front Neurol 2025, 16, 1517760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diringer, M.N.; Skolnick, B.E.; Mayer, S.A.; Steiner, T.; Davis, S.M.; Brun, N.C.; Broderick, J.P. Thromboembolic events with recombinant activated factor VII in spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: results from the Factor Seven for Acute Hemorrhagic Stroke (FAST) trial. Stroke 2010, 41, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Wei, L.; Zhou, X.; Yang, B.; Meng, J.; Wang, P. Risk factors for poor outcomes of spontaneous supratentorial cerebral hemorrhage after surgery. J Neurol 2022, 269, 3015–3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemphill, J.C.; Bonovich, D.C.; Besmertis, L.; Manley, G.T.; Johnston, S.C. The ICH score: a simple, reliable grading scale for intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke 2001, 32, 891–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyden, P.; Brott, T.; Tilley, B.; Welch, K.M.; Mascha, E.J.; Levine, S.; Haley, E.C.; Grotta, J.; Marler, J. Improved reliability of the NIH Stroke Scale using video training. NINDS TPA Stroke Study Group. Stroke 1994, 25, 2220–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiambeng, T.N.; Tucholski, T.; Wu, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Mitchell, S.D.; Roberts, D.S.; Jin, Y.; Ge, Y. Analysis of cardiac troponin proteoforms by top-down mass spectrometry. Methods Enzymol 2019, 626, 347–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apple, F.S.; Sandoval, Y.; Jaffe, A.S.; Ordonez-Llanos, J. IFCC Task Force on Clinical Applications of Cardiac Bio-markers. Cardiac Troponin Assays: Guide to Understanding Analytical Characteristics and Their Impact on Clinical Care. Clin Chem 2017, 63, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thygesen, K.; Alpert, J.S.; Jaffe, A.S.; Chaitman, B.R.; Bax, J.J.; Morrow, D.A.; White, H.D.; Executive Group on behalf of the Joint European Society of Cardiology (ESC)/American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA)/World Heart Federation (WHF) Task Force for the Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction. Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction (2018). J Am Coll Cardiol 2018, 72, 2231–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerner, S.T.; Auerbeck, K.; Sprügel, M.I.; Sembill, J.A.; Madžar, D.; Gölitz, P.; Hoelter, P.; Kuramatsu, J.B.; Schwab, S.; Huttner, H.B. Peak Troponin I Levels Are Associated with Functional Outcome in Intraerebral Hemorrhage. Cerebrovasc Dis 2018, 46, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualandro, D.M.; Puelacher, C.; Mueller, C. High-sensitivity cardiac troponin in acute conditions. Curr Opin Crit Care 2014, 20, 472–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lesch, H.; Haucke, L.; Kruska, M.; Ebert, A.; Becker, L.; Szabo, K.; Akin, I.; Alonso, A.; Fastner, C. Myocardial injury in spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage is not predicted by prior cardiac disease or neurological status: results from the Mannheim Stroke database. Front Neurol 2025, 16, 1510361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulia, A.; Srivastava, M.; Kumar, P. Elevated troponin levels as a predictor of mortality in patients with acute stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Neurol 2024, 15, 1351925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wettersten, N.; Maisel, A. Role of cardiac troponin levels in acute heart failure. Card Fail Rev 2015, 1, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesch, H.; Kruska, M.; Marx, A.; Haucke, L.; Ebert, A.; Becker, L.; Szabo, K.; Akin, I.; Alonso, A.; Fastner, C. The phenomenon of dynamic change of cardiac troponin levels in patients with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage increases in-hospital mortality independent of macrovascular coronary artery disease. J Neurol Sci 2025, 476, 123633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosso, M.; Stengl, H.; Scheitz, J.F.; Lewey, J.; Mayer, S.A.; Yaghi, S.; Kasner, S.E.; Witsch, J. Acute myocardial injury in spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: a secondary observational analysis of the FAST trial. J Am Heart Assoc 2024, 13, e035053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, A.; Diringer, M.N. Elevated troponin levels are associated with higher mortality following intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology 2006, 66, 1330–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maramattom, B.V.; Manno, E.M.; Fulgham, J.R.; Jaffe, A.S.; Wijdicks, E.F.M. Clinical importance of cardiac troponin release and cardiac abnormalities in patients with supratentorial cerebral hemorrhages. Mayo Clin Proc 2006, 81, 192–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safatli, D.A.; Günther, A.; Schlattmann, P.; Schwarz, F.; Kalff, R.; Ewald, C. Predictors of 30-day mortality in patients with spontaneous primary intracerebral hemorrhage. Surg Neurol Int 2016, 7 Supplement 18, S510–S517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulger, H.; Icme, F.; Parlatan, C.; Avci, B.S.; Aksay, E.; Avci, A. Prognostic relationship between high sensitivity troponin I level, hematoma volume and glasgow coma score in patients diagnosed with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Ir J Med Sci 2024, 193, 2559–2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rosa, L.; Manara, R.; Vodret, F.; Kulyk, C.; Montano, F.; Pieroni, A.; Viaro, F.; Zedde, M.L.; Napoletano, R.; Ermani, M.; et al. The “SALPARE study” of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: part 1. Neurol Res Pract 2023, 5, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, S.K.; Sadekur Rahman Sarkar, M.; Ahmed, K.M.A.; Hasan, M.; Esteak, T.; Uddin, M.N.; Alam, J.A.J.; Hasan, F.M.M.; Chowdhury, M.T.I.; Mondal, M.B.A. Predicting 30-Day Outcomes in Primary Intracerebral Hemorrhage Using the Intracerebral Hemorrhage Score: A Study in Bangladesh. Cureus 2024, 16, e73227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rådholm, K.; Arima, H.; Lindley, R.I.; Wang, J.; Tzourio, C.; Robinson, T.; Heeley, E.; Anderson, C.S.; Chalmers, J.; INTERACT2 Investigators. Older age is a strong predictor for poor outcome in intracerebral haemorrhage: the INTERACT2 study. Age Ageing 2015, 44, 422–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahrami, M.; Keyhanifard, M.; Afzali, M. Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage, initial computed tomography (CT) scan findings, clinical manifestations and possible risk factors. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2022, 12, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Béjot, Y.; Cordonnier, C.; Durier, J.; Aboa-Eboulé, C.; Rouaud, O.; Giroud, M. Intracerebral haemorrhage profiles are changing: results from the Dijon population-based study. Brain 2013, 136, 658–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Kim, B.J.; Ryu, W.S.; Kim, C.K.; Kim, N.; Park, B.J.; Yoon, B.W. White matter lesions and poor outcome after intracerebral hemorrhage: a nationwide cohort study. Neurology 2010, 74, 1502–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakar, B.; Akkaya, S.; Say, B.; Yuksel, U.; Alhan, A.; Turğut, E.; Ogden, M.; Ergun, U. In spontaneous intracerebral hematoma patients, prediction of the hematoma expansion risk and mortality risk using radiological and clinical markers and a newly developed scale. Neurol Res 2021, 43, 482–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrete-Araujo, A.M.; Egea-Guerrero, J.J.; Vilches-Arenas, Á.; Godoy, D.A.; Murillo-Cabezas, F. Predictors of mortality and poor functional outcome in severe spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: a prospective observational study. Med Intensiva 2015, 39, 422–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, S.B.; Moradiya, Y.; Dawson, J.; Lees, K.R.; Hanley, D.F.; Ziai, W.C.; VISTA-ICH Collaborators. Perihematomal Edema and Functional Outcomes in Intracerebral Hemorrhage: Influence of Hematoma Volume and Location. Stroke 2015, 46, 3088–3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.J.; Li, Q.; Tang, J.H.; Reis, C.; Araujo, C.; Feng, R.; Yuan, M.H.; Jin, L.Y.; Cheng, Y.L.; Jia, Y.J.; et al. The risk factors and prognosis of delayed perihematomal edema in patients with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. CNS Neurosci Ther 2019, 25, 1189–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.Y.; Sharma, G.; Strbian, D.; Putaala, J.; Desmond, P.M.; Tatlisumak, T.; Davis, S.M.; Meretoja, A. Natural History of Perihematomal Edema and Impact on Outcome After Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Stroke 2017, 48, 873–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, M.T.C.; Fonville, A.F.; Al-Shahi Salman, R. Long-term prognosis after intracerebral haemorrhage: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2014, 85, 660–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasongko, A.B.; Perdana Wahjoepramono, P.O.; Halim, D.; Aviani, J.K.; Adam, A.; Tsai, Y.T.; Wahjoepramono, E.J.; July, J.; Achmad, T.H. Potential blood biomarkers that can be used as prognosticators of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS One 2025, 20, e0315333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; He, H.; Shen, D.; Ye, X.; Chen, Z.; Zou, S.; Zhou, K.; Ye, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, H.; et al. Usefulness of Serum NOX4 as a Potential Biomarker to Predict Early Neurological Deterioration and Poor Outcome of Spontaneous Intracerebral Hemorrhage: A Prospective Observational Study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2025, 21, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, M.C.; Komotar, R.J.; Starke, R.M.; Doshi, D.; Otten, M.L.; Connolly, E.S. Elevated troponin levels are predictive of mortality in surgical intracerebral hemorrhage patients. Neurocrit Care 2010, 12, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheitz, J.F.; Sposato, L.A.; Schulz-Menger, J.; Nolte, C.H.; Backs, J.; Endres, M. Stroke-Heart Syndrome: Recent Advances and Challenges. J Am Heart Assoc 2022, 11, e026528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, P.W.; Won, Y.S.; Kwon, Y.J.; Choi, C.S.; Kim, B.M. Initial troponin level as a predictor of prognosis in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 2009, 45, 355–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemphill, J.C.; Greenberg, S.M.; Anderson, C.S.; Becker, K.; Bendok, B.R.; Cushman, M.; Fung, G.L.; Goldstein, J.N.; Macdonald, R.L.; Mitchell, P.H.; et al. Guidelines for the Management of Spontaneous Intracerebral Hemorrhage: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2015, 46, 2032–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheitz, J.F.; Nolte, C.H.; Doehner, W.; Hachinski, V.; Endres, M. Stroke-heart syndrome: clinical presentation and underlying mechanisms. Lancet Neurol 2018, 17, 1109–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, G.; Dai, C.; Feng, S.; Wu, G. Changes of Electrocardiogram and Myocardial Enzymes in Patients with Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Dis Markers 2022, 2022, 9309444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.; Lin, J.; Wang, D.; Liu, M.; Hao, Z.; Lei, C. Cardiac troponin and cerebral herniation in acute intracerebral hemorrhage. Brain Behav 2017, 7, e00697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marins, F.R.; Limborço-Filho, M.; D’Abreu, B.F.; Machado de Almeida, P.W.; Gavioli, M.; Xavier, C.H.; Oppenheimer, S.M.; Guatimosim, S.; Fontes, M.A.P. Autonomic and cardiovascular consequences resulting from experimental hemorrhagic stroke in the left or right intermediate insular cortex in rats. Auton Neurosci 2020, 227, 102695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.H.; Tang, S.C.; Lee, D.Y.; Shieh, J.S.; Lai, D.M.; Wu, A.Y.; Jeng, J.S. Impact of Supratentorial Cerebral Hemorrhage on the Complexity of Heart Rate Variability in Acute Stroke. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 11473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etgen, T.; Baum, H.; Sander, K.; Sander, D. Cardiac troponins and N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide in acute ischemic stroke do not relate to clinical prognosis. Stroke 2005, 36, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdi, S.; Oveis-Gharan, S.; Sinaei, F.; Ghorbani, A. Elevated troponin T after acute ischemic stroke: Association with severity and location of infarction. Iran J Neurol 2015, 14, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Component | Criteria | Points |

|---|---|---|

| GCS score | 3–4 | 2 |

| 5–12 | 1 | |

| 13–15 | 0 | |

| ICH volume | ≥30 mL | 1 |

| <30 mL | 0 | |

| IVH | Present | 1 |

| Absent | 0 | |

| Infratentorial origin | Yes | 1 |

| No | 0 | |

| Age | ≥80 years | 1 |

| <80 years | 0 | |

| Total Score Range | 0-6 | |

| Estimated 30-day mortality risk: 0 points: 0%, 1 point: 13%, 2 points: 26%, 3 points: 72%, 4 points: 97%, 5-6 points: 100% | ||

| Variable | Survived N=65 (%) |

Died N=35 (%) |

p |

| GCS score | <0.001A | ||

| 3-4 | 2 (3.1) | 11 (31.4) | |

| 5-12 | 9 (13.8) | 11 (31.4) | |

| 13-15 | 54 (83.1) | 13 (37.2) | |

| ICH volume (mL) | <0.001B | ||

| <30 | 47 (72.3) | 9 (25.7) | |

| ≥30 | 18 (27.7) | 26 (74.3) | |

| IVH | <0.001B | ||

| Yes | 15 (23.1) | 26 (74.3) | |

| No | 50 (76.9) | 9 (25.7) | |

| Infratentorial origin | 0.304B | ||

| Yes | 8 (12.3) | 7 (20.0) | |

| No | 57 (87.7) | 28 (80.0) | |

| Age (years) | 71.35±13.16 | 77.74±10.34 | 0.015C |

| ICH score | <0.001A | ||

| 0 | 17 (26.2) | 2 (5.7) | |

| 1 | 26 (40.0) | 2 (5.7) | |

| 2 | 11 (16.9) | 5 (14.3) | |

| 3 | 7 (10.8) | 13 (37.1) | |

| 4 | 4 (6.1) | 6 (17.2) | |

| 5 | 0 (0.0) | 3 (8.6) | |

| 6 | 0 (0.0) | 4 (11.4) | |

| NIHSS | 7.06±5.06 | 23.11±8.60 | <0.001C |

| Variable | Serum levels of hs-cTnI | |

| r | p | |

| ICH score | 0.311 | 0.002 |

| GCS score | -0.262 | 0.009 |

| ICH volume | 0.347 | <0.001 |

| IVH | 0.342 | 0.001 |

| Infratentorial origin | 0.119 | 0.240 |

| Age | 0.031 | 0.762 |

| NIHSS | 0.381 | <0.001 |

| Model | Variable | B | Exp (B) | 95% CI | p |

| 1 | ICH score | 1.017 | 2.764 | 1.829-4.178 | <0.001 |

| 2 | NIHSS | 0.367 | 1.443 | 1.241-1.679 | <0.001 |

| 3 | Serum hs-cTnI levels | 0.027 | 1.028 | 1.012-1.044 | 0.001 |

| Variable | B | Exp (B) | 95% CI | p |

| GCS score | -0.227 | 0.797 | 0.686-0.925 | 0.003 |

| ICH volume | 0.017 | 1.017 | 1.004-1.031 | 0.013 |

| IVH | 1.507 | 4.514 | 1.277-15.958 | 0.019 |

| Infratentorial origin | -0.183 | 0.833 | 0.139-4.996 | 0.841 |

| Age | 0.044 | 1.045 | 0.989-1.104 | 0.116 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).