1. Introduction

Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) is a prototype member of

Hepadinaviridae and the only one in this family that infects humans [

1,

2]. HBV infection may lead to a broad spectrum of liver diseases ranging from acute self-limiting hepatitis, asymptomatic carrier state, to chronic hepatitis and progressing to liver cirrhosis and Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [

3]. Two important features make HBV unique; first, its way of replication, where it uses the pregenomic RNA as an intermediate step for reverse transcription [

4,

5,

6] and second, the efficient utilization of its compact genome for the production of seven different proteins from 4 open reading frames (ORFs) [

4,

7]. These translation products include three Surface envelope glycoproteins PreS1, PreS2, and S; core (C) and e antigens (HBcAg and HBeAg); viral polymerase (Pol); and the X protein (HBx) [

8,

9,

10]. Mutations within the HBV ORFs, driven by the virus’s lack of proofreading activity during replication, may alter viral protein expression and replication dynamics, thereby influencing disease progression and management outcomes. [

7,

11].

HBV genome that differs >8% from other HBV genomes and >4% in

S gene is classified as a new genotype [

12,

13,

14,

15]. To date there are 10 HBV genotypes (A-J) identified worldwide, with different geographical distribution, clinical outcomes, disease progression [

12,

14,

16], risk of HCC and populations vulnerable to the infection [

17]. In Africa, genotypes A, D, and E are known to be predominant at various proportions in many parts [

12,

15]. In Eastern Africa, Genotypes A and D are endemic in Kenya [

18,

19,

20,

21], Uganda [

22], and Tanzania. [

23,

24] In Sudan, genotype D and E are predominant [

25,

26]. In settings where multiple HBV genotypes co-circulate, intergenotypic recombination occurs and contributes significantly to HBV genetic diversity and molecular epidemiology. [

21,

27,

28]. HBV genotypes and viral variants have been associated with specific clinical features of HBV-related liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma, although their influence on clinical outcomes is not fully established, genotypes A and D have been linked to increased disease severity and reduced treatment response [

3,

29].

To date, Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection remains a major cause of liver disease and cancer worldwide with approximately 1.2 million new HBV cases reported annually and an estimated 1.1 million deaths each year [

30]. In Kenya, the national prevalence is estimated at 3.5% [

31] with areas of the North Rift recording a high prevalence of >10.0% [

21] and the Kenya Cancer Registry listed liver cancer as the third cause of mortality [

32] This study aimed to characterize HBV among patients seeking medical care in HBV-endemic regions in Kenya and to identify circulating genotypes and ORF mutations.

2. Materials and Methods

HBsAg-positive blood samples of patients seeking medical services at outpatient departments of Marigat subcounty referral hospital and in Moi teaching and referral hospital (MTRH), Eldoret, were collected. These regions are in the North and Central Rift Valley respectively and have reported high prevalence of HBV [

21,

31]. Approval to carry out the study was obtained from Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI)-Scientific Ethical Research Unit (KEMRI-SERU) SERU/SSC No.2436, Maseno University (MSU) ethical committee (MSU/DRPI/MUERC/01121/22), and National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation (NACOSTI/P/23/31205). Similarly, written informed consent was obtained from all participants, with the consent process conducted by trained personnel at the facility. The selected HBsAg positive samples were temporally stored at -20 °C at the facility before they were transported to KEMRI in a cold chain for further processing.

HBV-DNA Extraction and Amplification

Viral DNA from the serum was extracted using QIAGEN

® blood DNA extraction kit following the manufacturer’s protocol. The HBV complete genome was amplified using primers given in

Table 1 and as previously described by Günther et al.

, 1995 [

33]. Briefly, 5 µL of DNA extract was used in a 25 µL PCR master mix containing the Expand High Fidelity assay (Roche), 1.5 mM MgCl

2, 1.25mM dNTP (Qiagen), and 20µM primer P1-P2 in 10 µL of 5X buffer. The amplification reactions were carried out as a ‘‘hot start’’ PCR and thermocycling conditions as described by Günther et al.

, 1995 [

33]. The amplicons were visualized on a 2% agarose gel electrophoresis, and any PCR-negative sample was re-amplified in the second stage. Five microliters (5 µL) of the first stage PCR was used in the nested PCR using FLG1 and FLG2 primers given in

Table 1 as described by Osiowy et al. 2006 [

34]. The recipe for the master mix and the thermocycling conditions were as in stage 1.

The pre-core and BCP region were amplified by nested Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) using primers given in

Table 1, and as previously described by [

35]. Five microliters of the first-stage PCR amplicons were used for the second amplification with S2 and C2 primers for HBsAg and BCP/PC, respectively. The master mix and PCR profile were similar to those in the first round. All 1st and 2nd round amplicons were gel-purified before sequencing and the sequences were treated as previously described by Kowalec et al.,2013 [

36]. One microliter of nested PCR product for BCP and S-gene was analyzed on a 1.2% agarose gel in 1X TBE buffer stained with SYBR Green (Invitrogen

®).

HBV- Isolates Sequencing

All PCR-positive amplicons were purified using the Qiagen Gel purification kit according to the manufacturer’s recommended protocol. Purified DNA was quantified with Nanodrop (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, USA), and purified DNA (50ng) was then sequenced using an automated ABI 3750 XL Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies). Sequencing conditions were specified in the protocol for the Taq DyeDeoxy Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit. Directly amplified sequences were assembled and analysed using DNA sequence analysis software (Lasergene software suite v7.1.0, DNASTAR). Sequences were aligned and edited separately using ClustalX v2.0.1 [

37] and databases were aligned using MAFFT [

38] respectively.

Determination of HBV genotypes and sequence analysis

Genotypes were determined based on phylogenetic analysis of complete surface region sequences or using the NCBI genotyping tool (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/genotyping/). Phylogenetic analysis was carried out using MEGA 12.0.14, trees were constructed by Kimura 2-parameter matrix and trees were viewed by tree view program [

39]. All sequences were analyzed in both forward and backward directions. Mutations were determined by aligning the obtained sequences with known wild type gene bank sequences using clustalW and BioEdit software. Mutations on the functional regions of the BCP (1750-1795), pre-core mRNA initiation sites (1788-1791), pre-genomic RNA (1817-1821) and other upstream mutations were analyzed. Complete S-gene alignment with respective genotypes was also done. PreS1, PreS2, Surface and part of the polymerase spanning from catalytic domain A-E was analyzed for mutations. Determination of the genotype alignment was carried out using a wild-type genotype specific nucleotide downloaded from NCBI data bank.

3. Results

Out of 85 HBsAg positive samples selected, 32 and 38 samples were successfully amplified and sequenced for the surface and BCP/pre-core regions of the virus, respectively. Of the sequenced samples, only 26 samples yielded high-quality sequences suitable for analysis. Using the NCBI HBV genotyping tool [

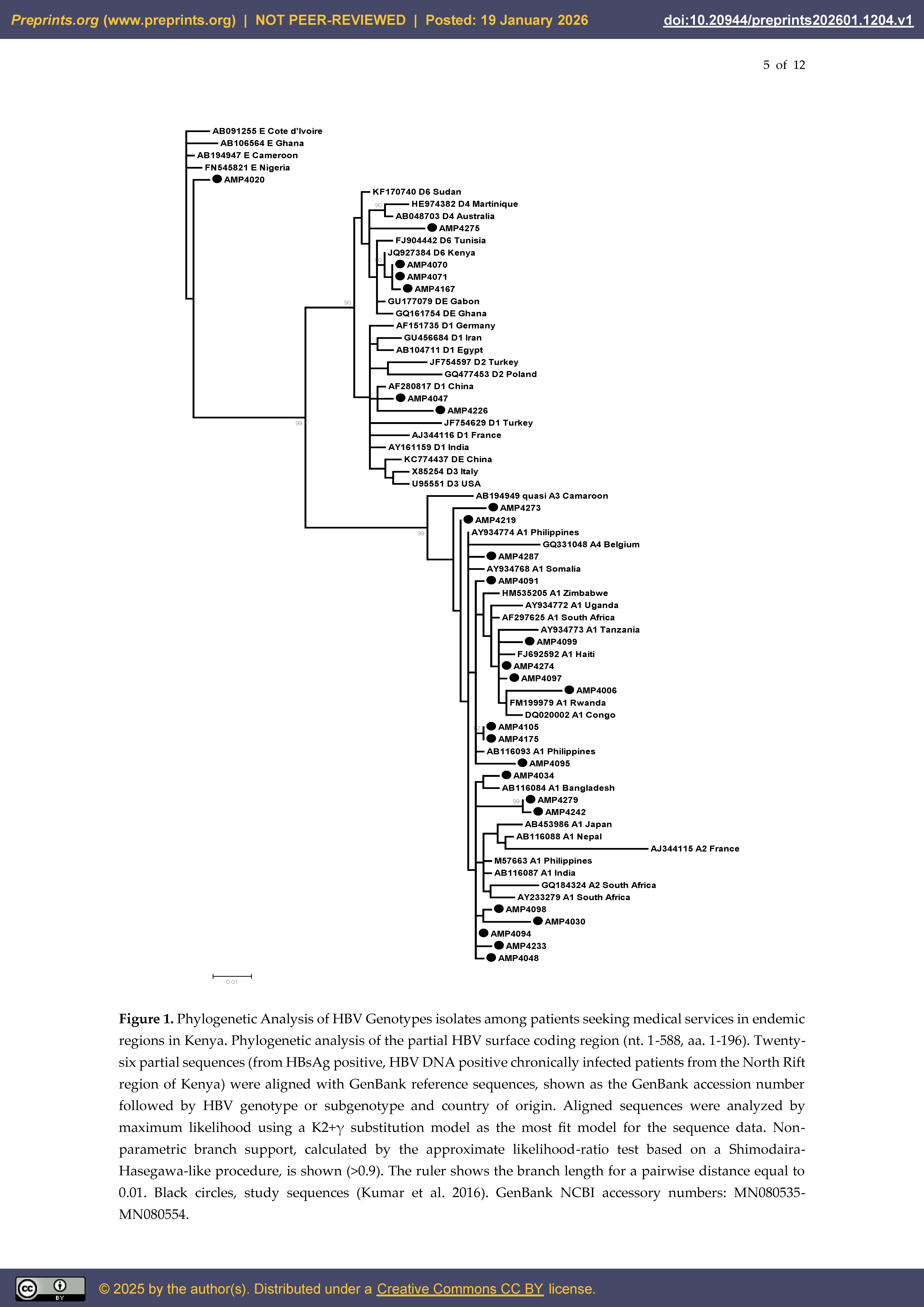

40], analysis of the viral surface region sequences revealed that 73.1% (19/26) of the isolates belonged to genotype A, 23.1% (6/26) to genotype D or D/A recombinant forms, and 3.8% (1/26) to genotype E.

3.1. HBV Genotype A Circulating in Kenya

Following phylogenetic analysis using both neighbor-joining and Maximum likelihood, it was observed that all HBV genotype A isolated were subtype A1. There was no clear distinction between A1 Asia and Africa subtypes, the isolates clustered with isolates from across the globe (

Figure 1). For those isolates that clustered with African subtypes, they clustered with isolates from Tanzania, Rwanda, Congo and Somalia. For the Asian subtypes our isolates clustered with Philippines and Bangladesh. It was interesting to note that 5/19 isolates (AMP4098, AMP4030, AMP4094, AMP4233, and AMP4048) did not cluster closely with any sequence, however they distantly clustered with sequences from Asia and South Africa. Similarly, 4/19 isolates (AMP 4099, AMP4274, AMP4097 and AMP4006 clustered with sequences from Tanzania, Rwanda, Congo and Haiti (

Figure 1). Samples collected from the same locality and family clustered together with >92% bootstraps (AMP4279 and AMP4242, AMP4105 and AMP4175, AMP4098 and AMP4030) (

Figure 1).

3.2. HBV Genotype D, E and Their Recombinants

The predominant HBV/D sub-genotypes circulating in these areas were sub-genotype D6; 4/6 (66.7%), followed by D1 2/6 (33.3%) and the rest were recombinants of genotype D 1(16.7%) (

Figure 1). All the HBV genotype D6 isolates closely clustered with sequences from West Africa mainly Tunisia whereas those of D1 clustered with sequences from Asia, Iran, Lebanon and China. HBV Genotype E closely clustered with sequences from Senegal and Côte d’Ivoire (

Figure 1).

3.3. Identification and Profile of Mutations in in Open Reading Frames of HBV Genotype D and E

Mutations observed in HBV/D and E in the Pre-S2 and S regions did not follow a specific pattern, with each patient exhibiting a unique mutation profile. However, BCP/PC regions there was a pattern (

Table 2). All HBV/D and E patients were

ayw2 and

ayw4 serotypes respectively and harbored at least two mutations in the ORF. Notably, we did not observe any mutations in polymerase and Pre-S/S regions of two patients (AMP4070 and AMP4071). Three mutations were prevalent in HBV/D and E BCP/PC gene; 5/7(71.4%) had G1757A 4/7(57.1%) had G1896A. Other specific mutations were a 9-nucleotide insertion at 1687 (sample AMP4275) and double mutation A1762T/G1764A (sample AMP4167) (

Table 2). Few mutations were detected in the polymerase and Pre-S/S regions; however, two patients (AMP4226 and AMP4275) had up to four mutations within the surface region. The only mutation observed in the polymerase region was V191I (

Table 2).

3.4. Mutations Occurring in HBV Genotype A1

All the samples were adw2 serotype. Of the 19 HBV/A samples, 11 (57.9%) had mutations. In PreS2, none of the samples had mutations, while in the Polymerase gene, mutation A194T was observed in one sample (AMP4242). No consistent mutation pattern was observed in the HBsAg determinant region, with three patients (AMP4006, AMP4242, AMP4279) having up to three different mutations in the area (

Table 2).

3.5. Mutations that Co-Existence with Each Other in Pre-Core and BCP Mutations

A higher number of mutations was observed in the BCP/PC region of HBV/D and HBV/E compared with HBV/A1; therefore, mutation profiles of the basal core promoter and Pre-core regions (nucleotides 1750–1900) were further analyzed in HBV/D and HBV/E. We identified varying frequencies and patterns of the mutations (

Table 3). Of clinical note, one patient (AMP4167) with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) exhibited a complex mutation profile including T1753C, A1762T/G1764A, C1858T, G1896A, and T1768A (

Table 3). Similarly, the single genotype E isolate contained a unique insertion of AACAATT, at position 2698 of the viral polyprotein.

4. Discussion

HBV remains a significant global public health challenge and has been prioritized by the World Health Organization for elimination by 2030. A central policy objective of this strategy is the timely identification of new cases of chronic hepatitis B infection to enable linkage to care and prevent transmission. Kenya is categorized as a middle endemic zone with HBV rate of 3.5% [

31] and Rift Valley region of Kenya is among the areas with high prevalence of hepatitis B, estimated at 92.9% among patients presenting with jaundice [

21] and 6.3–13% in the general population [

31,

41].

Phylogenetic analysis of HBV partial S-gene sequences revealed a heterogeneous viral population comprising genotypes A, D, and E, consistent with the diversity reported across Eastern Africa. HBV genotype A1 remains the predominant genotype in Kenya among patients and blood donors [

18,

19,

20,

21]. This is consistent with the well-established predominance of A1 in East and Southern Africa [

15,

42]. A subset of genotype A isolates including clustered with Central African, Caribbean Europe and Japan reference sequences, reflecting the broader global dispersal patterns attributed to historical human migration or regional strain importation. Genotype D isolates formed well-supported clusters aligning with reference sequences from the West Africa, Middle East, North Africa, and Europe. The pattern is consistent with the known broad distribution of genotype D [

25,

26]. We identified HBV genotype E, which is a predominant genotype confined to West Africa (Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Cameroon, and Nigeria) and rarely reported in East Africa [

43]. Our findings suggest either potential cross-regional viral introduction or the presence of previously undetected minority HBV genotype E lineages circulating within the community.

Studies from the southern regions of Kenya indicate that HBV genotype A is the sole circulating genotype, [

18,

44,

45,

46] consistent with the predominant genotypes reported in neighboring countries [

23,

24,

47]. In this study, the prevalence of HBV genotypes D and E was observed among communities in northern regions where these genotypes are known to predominate [

25,

48]. This clustering pattern reflects the geographic origins, cross-border transmissions and evolutionary trajectories of these genotypes. Unlike previous studies that demonstrated a clear distinction between Asian and African HBV genotype A1 clades [

18], the present study shows that HBV/A1 isolates cluster randomly with sequences from both Asia and Africa, regions where this genotype is prevalent.

Sequences from patients originating from the same locality clustered together with high bootstrap support, indicating community-level clustering and localized HBV transmission, particularly in endemic areas with high prevalence of genotypes D and A. This finding is consistent with community and familial transmission recently observed in this region during the implementation of community-level HBV control strategies [

41]. These findings emphasize the need for targeted community-based interventions, especially to understand transmission of genotypes E and the circulating recombinants.

Viruses co-evolve within human hosts and continually diverge through mutation, a key factor in the persistence and success of viral infections [

49]. HBV exhibits a high mutation rate driven by its replication strategy, with important implications for viral fitness and antiviral resistance [

50]. With estimated substitution rates of ~2 × 10

−4 per site per year or higher, and a lack of proofreading activity, this underscores HBV’s substantial genetic variability [

34,

51]. The data presented in this study showed mutations in genotype A, D, and E isolates in the BCP, PreS, overlapping S gene and polymerase gene. On BCP/pre-core the nucleotide exchange mutation of prominence were double A1762T (A=T; changing lysine to methionine) and G1764A (G=A; changing valine to isoleucine), which have also been detected in severe liver disease patients and is associated with HCC [

52,

53] and reduced expression of HBeAg but enhanced viral genome replication [

54,

55]. Other studies found out that the mutation emerges sometimes earlier before the onset of HCC [

56]. This mutation, which is predominant in HBV genotype D, can be detected up to eight years before HCC diagnosis and, either alone or in combination with other viral mutations, predicts HCC development in approximately 80% of cases [

57].

V191I and A194T HBV polymerase region mutations observed in this study, have been implicated in altered viral behavior and clinical outcomes; while A194T has been reported in the context of tenofovir treatment failure and polymerase variability, V191I has emerged in some cases with virologic breakthrough and may act as a secondary/resistance-associated variant [

58,

59]. These findings highlight the need for further investigation beyond identification to clarify their impact on treatment outcomes and viral persistence

This study observed a high mutation frequency in the HBsAg region compared to other ORFs investigated. Mutations in this region can alter HBsAg antigenicity, resulting in immune escape from anti-HBs antibodies, vaccine- or HBIG-induced immunity, or causing diagnostic escape [

60]. We identified mutations within the “a” determinant (amino acids 124–147), including G130S and F134L, which are associated with MHR variability and immune-escape phenotypes [

60,

61,

62]. The impact of the other mutations identified in this study remains unclear; however, occult hepatitis infection has previously been reported in these communities. [

63].

Conclusion: HBV genotypes A and D predominate among chronic infections in Kenya. The detection of point mutations in viral ORFs among patients in care highlights the need for molecular surveillance to inform clinical and public health responses.

Limitation of the study: Most samples failed to amplify or sequence the BCP/PC or S-region genes despite repeated attempts, likely due to low viral concentrations in serum.

5. Conclusions

HBV genotypes A and D predominate among chronic infections in Kenya. The detection of point mutations in viral ORFs among patients in care highlights the need for molecular surveillance to inform clinical and public health responses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: MO, JO. Methodology, JO, MO, GT, LO. Writing—original draft MO, JO. Validation, MO, JO. Formal Analysis, MO, JO, LO. Investigation, GT, JO, MO. Resources; MO. Data Curation: MO, GT. Writing—Original draft preparation: MO, JO. Writing—Review & editing, JO, MO, GT, LO. Visualization: JO, LO. Supervision, LO, MO. Project Administration: MO, LO. Funding Acquisition: MO. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially supported by The Gilead Sciences, Inc. The grant was awarded to Missiani Ochwoto in 2022 under Research Scholar Program (RSP) Award.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by Kenya Medical Research Institute’s (KEMRI’s) Scientific and Ethics Review Unit (SERU) Protocol No. SERU/SSC No.2436, Maseno University (MSU) ethical committee (MSU/DRPI/MUERC/01121/22), and National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation (NACOSTI/P/23/31205). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Any research article describing a study involving humans should contain this statement. Please add “Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.” OR “Patient consent was waived due to REASON (please provide a detailed justification).” OR “Not applicable.” for studies not involving humans. You might also choose to exclude this statement if the study did not involve humans. Written informed consent for publication must be obtained from participating patients who can be identified (including by the patients themselves). Please state “Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper” if applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All clinical data generated or analyzed during this study is confidential and is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The sequences generated and analyzed were deposited at GenBank NCBI accessory numbers: MN080535-MN080554.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the participants who agreed to participate in the study. We thank the managements of Marigat Subcounty Hospital, and that of Kenya Medical research Institute (KEMRI) for their support, the Maseno University and Gilead Research Scholar Program (RSP) Award for their financial support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors of this publication have no competing interest in this paper.:

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BCP/PC |

Basal core promoter gene/Pre-Core |

| dNTP |

Deoxynucleotide Triphosphate |

| DNA |

Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| HBV |

Hepatitis B virus |

| HBV/A1 |

Hepatitis B virus Genotype A1 |

| HBV/D |

Hepatitis B virus Genotype D |

| HBV/E |

Hepatitis B virus Genotype E |

| HCC |

Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| HBsAg |

Hepatitis B surface antigen |

| KEMRI |

Kenya Medical Research Institute’s |

| LMIC |

Low- and middle-income countries |

| ORFs |

Open Reading Frames |

| PCR |

Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

References

- Kramvis, A; Arakawa, K; Yu, MC; Nogueira, R; Stram, DO; Kew, MC. Relationship of serological subtype, basic core promoter and precore mutations to genotypes/subgenotypes of hepatitis B virus. Journal of medical virology 2008, 80(1), 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health O. Global hepatitis report 2024: action for access in low- and middle-income countries; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Datfar, T; Doulberis, M; Papaefthymiou, A; Hines, IN; Manzini, G. Viral Hepatitis and Hepatocellular Carcinoma: State of the Art. Pathogens 2021, 10(11), 1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quasdorff, M; Protzer, U. Control of hepatitis B virus at the level of transcription. J Viral Hepat. 2010, 17(8), 527–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giersch, K; Allweiss, L; Volz, T; Dandri, M; Lütgehetmann, M. Serum HBV pgRNA as a clinical marker for cccDNA activity. J Hepatol. 2017, 66(2), 460–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, K; Rydell, GE; Larsson, SB; Andersson, M; Norkrans, G; Norder, H; et al. High serum levels of pregenomic RNA reflect frequently failing reverse transcription in hepatitis B virus particles. Virol J 2018, 15(1), 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoulim, F; Chen, PJ; Dandri, M; Kennedy, PT; Seeger, C. Hepatitis B virus DNA integration: Implications for diagnostics, therapy, and outcome. J Hepatol 2024, 81(6), 1087–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, HE; Gerok, W; Vyas, GN. The molecular biology of hepatitis B virus. Trends Genet. 1989, 5(5), 154–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckwold, VE; Xu, Z; Chen, M; Yen, TS; Ou, JH. Effects of a naturally occurring mutation in the hepatitis B virus basal core promoter on precore gene expression and viral replication. J Virol. 1996, 70(9), 5845–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R. Review on hepatitis B virus precore/core promoter mutations and their correlation with genotypes and liver disease severity. World J Hepatol. 2022, 14(4), 708–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheldon, J; Rodès, B; Zoulim, F; Bartholomeusz, A; Soriano, V. Mutations affecting the replication capacity of the hepatitis B virus. J Viral Hepat. 2006, 13(7), 427–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramvis, A; Kew, M; François, G. Hepatitis B virus genotypes. Vaccine 2005, 23(19), 2409–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, MF; Lai, CL. Hepatitis B virus genotypes: natural history and implications for treatment. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007, 1(2), 321–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatematsu, K; Tanaka, Y; Kurbanov, F; Sugauchi, F; Mano, S; Maeshiro, T; et al. A genetic variant of hepatitis B virus divergent from known human and ape genotypes isolated from a Japanese patient and provisionally assigned to new genotype J. J Virol. 2009, 83(20), 10538–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramvis, A; Kew, MC. Epidemiology of hepatitis B virus in Africa, its genotypes and clinical associations of genotypes. Hepatol Res. 2007, 37(s1), S9–s19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, CL; Kao, JH. Hepatitis B virus genotypes and variants. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2015, 5(5), a021436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S; Wang, Z; Li, Y; Ding, G. Adaptive evolution of proteins in hepatitis B virus during divergence of genotypes. Scientific Reports 2017, 7(1), 1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochwoto, M; Chauhan, R; Gopalakrishnan, D; Chen, CY; Ng’ang’a, Z; Okoth, F; et al. Genotyping and molecular characterization of hepatitis B virus in liver disease patients in Kenya. Infect Genet Evol. 2013, 20, 103–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwange, SO; Budambula, NL; Kiptoo, MK; Okoth, F; Ochwoto, M; Oduor, M; et al. Hepatitis B virus subgenotype A1, occurrence of subgenotype D4, and S gene mutations among voluntary blood donors in Kenya. Virus Genes. 2013, 47(3), 448–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langat, BK; Ochwedo, KO; Borlang, J; Osiowy, C; Mutai, A; Okoth, F; et al. Genetic diversity, haplotype analysis, and prevalence of Hepatitis B virus MHR mutations among isolates from Kenyan blood donors. PLoS One 2023, 18(11), e0291378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochwoto, M; Kimotho, JH; Oyugi, J; Okoth, F; Kioko, H; Mining, S; et al. Hepatitis B infection is highly prevalent among patients presenting with jaundice in Kenya. BMC Infectious Diseases 2016, 16(1), 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zirabamuzale, JT; Opio, CK; Bwanga, F; Seremba, E; Apica, BS; Colebunders, R; et al. Hepatitis B virus genotypes A and D in Uganda. J Virus Erad. 2016, 2(1), 19–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbi, JC; Dillon, M; Purdy, MA; Drammeh, BS; Tejada-Strop, A; McGovern, D; et al. Molecular epidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection in Tanzania. Journal of General Virology 2017, 98(5), 1048–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mlewa, M; Henerico, S; Nyawale, HA; Mangowi, I; Shangali, AR; Manisha, AM; et al. The pattern change of hepatitis B virus genetic diversity in Northwestern Tanzania. Scientific Reports 2025, 15(1), 8021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahgoub, S; Candotti, D; El Ekiaby, M; Allain, JP. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection and recombination between HBV genotypes D and E in asymptomatic blood donors from Khartoum, Sudan. J Clin Microbiol. 2011, 49(1), 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousif, M; Mudawi, H; Hussein, W; Mukhtar, M; Nemeri, O; Glebe, D; et al. Genotyping and virological characteristics of hepatitis B virus in HIV-infected individuals in Sudan. Int J Infect Dis. 2014, 29, 125–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurbanov, F; Tanaka, Y; Mizokami, M. Geographical and genetic diversity of the human hepatitis B virus. Hepatol Res. 2010, 40(1), 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croagh, C; Desmond, P; Bell, S. Genotypes and viral variants in chronic hepatitis B: A review of epidemiology and clinical relevance. World Journal of Hepatology 2015, 7(3), 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, K; Yotsuyanagi, H; Yatsuhashi, H; Karino, Y; Takikawa, Y; Saito, T; et al. Risk factors for long-term persistence of serum hepatitis B surface antigen following acute hepatitis B virus infection in Japanese adults. Hepatology 2014, 59(1), 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization WH. Global hepatitis report 2024: action for access in low-and middle-income countries; World Health Organization, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ondondo, RO; Muthusi, J; Oramisi, V; Kimani, D; Ochwoto, M; Young, P; et al. Prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection in Kenya: A study nested in the Kenya Population-based HIV Impact Assessment 2018. Plos one 2024, 19(11), e0310923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korir, A; Okerosi, N; Ronoh, V; Mutuma, G; Parkin, M. Incidence of cancer in N airobi, K enya (2004–2008). International journal of cancer 2015, 137(9), 2053–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günther, S; Li, BC; Miska, S; Krüger, DH; Meisel, H; Will, H. A novel method for efficient amplification of whole hepatitis B virus genomes permits rapid functional analysis and reveals deletion mutants in immunosuppressed patients. J Virol. 1995, 69(9), 5437–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osiowy, C; Giles, E; Tanaka, Y; Mizokami, M; Minuk, GY. Molecular evolution of hepatitis B virus over 25 years. J Virol. 2006, 80(21), 10307–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osiowy, C; Kaita, K; Solar, K; Mendoza, K. Molecular characterization of hepatitis B virus and a 9-year clinical profile in a patient infected with genotype I. J Med Virol. 2010, 82(6), 942–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalec, K; Minuk, GY; Børresen, ML; Koch, A; McMahon, BJ; Simons, B; et al. Genetic diversity of hepatitis B virus genotypes B6, D and F among circumpolar indigenous individuals. Journal of Viral Hepatitis 2013, 20(2), 122–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larkin, MA; Blackshields, G; Brown, NP; Chenna, R; McGettigan, PA; McWilliam, H; et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 2007, 23(21), 2947–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K; Misawa, K; Kuma, K; Miyata, T. MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30(14), 3059–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S; Stecher, G; Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 7.0 for Bigger Datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016, 33(7), 1870–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozanov, M; Plikat, U; Chappey, C; Kochergin, A; Tatusova, T. A web-based genotyping resource for viral sequences. Nucleic Acids Research 2004, 32 suppl_2, W654–W9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochwoto, M; Ondondo, RO; Matoke, LM; Tuitoek, G; Ogwora, EK; Omari, SW; et al. Predictors, and Trends of Hepatitis B Virus in Selected Regions of Kenya. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNaughton, AL; Revill, PA; Littlejohn, M; Matthews, PC; Ansari, MA. Analysis of genomic-length HBV sequences to determine genotype and subgenotype reference sequences. Journal of General Virology 2020, 101(3), 271–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toyé, RM; Loureiro, CL; Jaspe, RC; Zoulim, F; Pujol, FH; Chemin, I. The Hepatitis B Virus Genotypes E to J: The Overlooked Genotypes. Microorganisms 2023, 11(8), 1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aluora, PO; Muturi, MW; Gachara, G. Seroprevalence and genotypic characterization of HBV among low risk voluntary blood donors in Nairobi, Kenya. Virol J 2020, 17(1), 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibaya, RM; Lihana, RW; Kiptoo, M; Songok, EM; Ng’ang’a, Z; Osman, S; et al. Characterization of HBV Among HBV/HIV-1 Co-Infected Injecting Drug Users from Mombasa, Kenya. Curr HIV Res. 2015, 13(4), 292–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mabeya, SN; Ngugi, C; Lihana, RW; Khamadi, SA; Nyamache, AK. Predominance of Hepatitis B Virus Genotype A Among Treated HIV Infected Patients Experiencing High Hepatitis B Virus Drug Resistance in Nairobi, Kenya. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2017, 33(9), 966–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbi, JC; Ben-Ayed, Y; Xia, GL; Vaughan, G; Drobeniuc, J; Switzer, WM; et al. Disparate distribution of hepatitis B virus genotypes in four sub-Saharan African countries. J Clin Virol. 2013, 58(1), 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hundie, GB; Stalin Raj, V; Gebre Michael, D; Pas, SD; Koopmans, MP; Osterhaus, AD; et al. A novel hepatitis B virus subgenotype D10 circulating in Ethiopia. J Viral Hepat. 2017, 24(2), 163–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geoghegan, JL; Duchêne, S; Holmes, EC. Comparative analysis estimates the relative frequencies of co-divergence and cross-species transmission within viral families. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13(2), e1006215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caligiuri, P; Cerruti, R; Icardi, G; Bruzzone, B. Overview of hepatitis B virus mutations and their implications in the management of infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2016, 22(1), 145–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yano, Y; Azuma, T; Hayashi, Y. Variations and mutations in the hepatitis B virus genome and their associations with clinical characteristics. World J Hepatol. 2015, 7(3), 583–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, M; Kramvis, A; Kew, MC. High prevalence of 1762T 1764A mutations in the basic core promoter of hepatitis B virus isolated from black Africans with hepatocellular carcinoma compared with asymptomatic carriers. Hepatology 1999, 29(3), 946–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, CJ; Kao, JH. Core promoter mutations of hepatitis B virus and hepatocellular carcinoma: story beyond A1762T/G1764A mutations; Wiley Online Library, 2008; pp. 347–50. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, MJ; Blatt, LM; Kao, JH; Cheng, JT; Corey, WG. Basal core promoter T1762/A1764 and precore A1896 gene mutations in hepatitis B surface antigen-positive hepatocellular carcinoma: a comparison with chronic carriers. Liver International 2007, 27(10), 1356–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, R; Kazim, SN; Bhattacharjee, J; Sakhuja, P; Sarin, SK. Basal core promoter, precore region mutations of HBV and their association with e antigen, genotype, and severity of liver disease in patients with chronic hepatitis B in India. Journal of medical virology 2006, 78(8), 1047–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X; Jin, Y; Qian, G; Tu, H. Sequential accumulation of the mutations in core promoter of hepatitis B virus is associated with the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in Qidong, China. J Hepatol. 2008, 49(5), 718–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z; Zhuang, L; Lu, Y; Xu, Q; Tang, B; Chen, X. Naturally occurring basal core promoter A1762T/G1764A dual mutations increase the risk of HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Oncotarget 2016, 7(11), 12525–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y; Chang, S; Martin, R; Flaherty, J; Mo, H; Feierbach, B. Characterization of Hepatitis B virus polymerase mutations A194T and CYEI and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate or tenofovir alafenamide resistance. J Viral Hepat. 2021, 28(1), 30–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahiya, M; Tai, T; Hussaini, T; Ritchie, G; Matic, N; Yoshida, EM; et al. Virological Response to Lamivudine and Tenofovir Treatment in a Mono-infected Chronic Hepatitis B Patient with Potential Tenofovir Resistance: A Case Report. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2025, 13(1), 84–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, N; Onorato, L; Minichini, C; Di Caprio, G; Starace, M; Sagnelli, C; et al. Clinical significance of hepatitis B surface antigen mutants. World J Hepatol. 2015, 7(27), 2729–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, CH; Yuan, Q; Chen, PJ; Zhang, YL; Chen, CR; Zheng, QB; et al. Influence of mutations in hepatitis B virus surface protein on viral antigenicity and phenotype in occult HBV strains from blood donors. J Hepatol. 2012, 57(4), 720–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarevic, I; Banko, A; Miljanovic, D; Cupic, M. Immune-Escape Hepatitis B Virus Mutations Associated with Viral Reactivation upon Immunosuppression. Viruses 2019, 11(9). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jepkemei, KB; Ochwoto, M; Swidinsky, K; Day, J; Gebrebrhan, H; McKinnon, LR; et al. Characterization of occult hepatitis B in high-risk populations in Kenya. PLoS One 2020, 15(5), e0233727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).