1. Introduction

Actinic keratoses (AKs) represent the clinical manifestation of cutaneous field cancerization and are biologically positioned along a continuum that may culminate in squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Their natural history is characterized by marked histopathological heterogeneity, variable clinical presentation (grades I–III), and the frequent presence of subclinical lesions within chronically photodamaged skin, all of which complicate the assessment of true disease burden and progression risk1.

Field-directed therapies, including photodynamic therapy (PDT), 5-fluorouracil, imiquimod, tirbanibulin, and diclofenac, are specifically designed to target both clinically visible lesions and the surrounding subclinical disease within the cancerized field2. In routine clinical practice, treatment response is primarily evaluated through clinical inspection and dermoscopy. However, growing evidence indicates that clinical clearance does not necessarily reflect complete biological resolution. Histopathological persistence has been reported in up to 40–60% of lesions that appear clinically resolved, highlighting a substantial discrepancy between visible improvement and residual intraepidermal atypia.

Although dermoscopy is widely accessible, rapid, and highly effective in the diagnostic differentiation between AK and SCC, its performance in treatment monitoring is more limited. Morphological criteria of response may be subtle, transient, or nonspecific, particularly in thin AKs or following field therapies, reducing its sensitivity for detecting minimal residual disease3. As a result, dermoscopy alone may underestimate persistent subclinical alterations within the treated field.

This clinicopathological mismatch underscores the need for non-invasive imaging tools capable of documenting epidermal architectural normalization, reduction of keratinocyte atypia, and quantitative changes in the superficial dermis. High-resolution imaging techniques such as reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM), line-field confocal optical coherence tomography (LC-OCT), and high-frequency ultrasound (HFUS), together with emerging optical approaches such as in vivo Raman spectroscopy, have been proposed to address this unmet need by enabling a more comprehensive evaluation of treatment response, residual subclinical disease, and potentially recurrence risk. Importantly, these imaging-derived parameters may complement established clinical trial endpoints, such as complete clearance rates, Actinic Keratosis Area and Severity Index (AKASI), and recurrence, by providing a more sensitive, biologically grounded assessment of response beyond macroscopic appearance.

RCM and LC-OCT provide complementary cellular-to-architectural information, allowing in vivo visualization of epidermal disorganization, keratinocyte atypia, and their dynamic modification following therapy4,5. HFUS, while lacking cellular resolution, captures quantitative dermal changes, such as variations in subepidermal low-echogenic band (SLEB) thickness and dermal echogenicity, that reflect the evolution of the photodamaged field after treatment6. More recently, Raman spectroscopy has emerged as a potential tool for probing tissue biochemical composition, offering the possibility of identifying optical biomarkers associated with keratinization, dysplasia, and treatment-induced molecular changes7.

In this narrative review, we propose a clinically oriented multimodal framework for monitoring treatment response in AK. Specifically, we aim to: (i) clarify the strengths and limitations of clinical assessment and dermoscopy in post-treatment follow-up; (ii) synthesize current evidence on response criteria derived from RCM, LC-OCT, and HFUS, with practical considerations regarding timing and standardization; and (iii) discuss the emerging, yet still exploratory, role of Raman spectroscopy as a potential surrogate molecular endpoint. Finally, we outline a pragmatic follow-up algorithm and a research roadmap to support future validation of non-invasive response criteria against clinically meaningful outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

This work was designed as an evidence-informed narrative review aimed at summarizing the current state of the art and the clinical applicability of non-invasive imaging techniques for monitoring treatment response in actinic keratosis (AK) treated with field-directed therapies.

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

A structured literature search was conducted in PubMed and Scopus, covering publications from January 2010 to December 2025. For the PubMed search, official Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) were used when available, including “Keratosis, Actinic”, “Microscopy, Confocal”, “Tomography, Optical Coherence”, “Ultrasonography”, and “Dermoscopy”. These terms were combined with free-text keywords referring to imaging techniques without a dedicated MeSH term, such as “LC-OCT”, “high-frequency ultrasound”, “Raman spectroscopy”, “reflectance confocal”, “RCM”, “OCT”, and “HFUS”.Keywords related to treatment response assessment were searched as free text and included “treatment response”, “monitoring”, “follow-up”, “post-treatment”, and “therapy”.

The complete PubMed search string was as follows:

("Keratosis, Actinic"[MeSH Terms] OR "actinic keratosis"[Title/Abstract] OR AK[Title/Abstract]) AND ("Microscopy, Confocal"[MeSH Terms] OR "reflectance confocal"[Title/Abstract] OR RCM[Title/Abstract] OR "Tomography, Optical Coherence"[MeSH Terms] OR OCT[Title/Abstract] OR "LC-OCT"[Title/Abstract] OR "Ultrasonography"[MeSH Terms] OR "high frequency ultrasound"[Title/Abstract] OR HFUS[Title/Abstract] OR "Dermoscopy"[MeSH Terms] OR dermoscopy[Title/Abstract] OR "Raman spectroscopy"[Title/Abstract] OR Raman[Title/Abstract]) AND ("treatment response"[Title/Abstract] OR monitoring[Title/Abstract] OR "follow up"[Title/Abstract] OR therapy[Title/Abstract] OR "post treatment"[Title/Abstract])

The search was complemented by manual screening of the reference lists of selected articles. When appropriate, expert input from clinicians with experience in the management of AK and field cancerization was used to contextualize imaging findings. This expert input was limited to interpretative and contextual purposes and did not influence study selection or data extraction.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria and Study Selection

In PubMed, article types relevant to primary research were considered, including Clinical Study, Observational Study, Evaluation Study, Comparative Study, and Clinical Trial. Case reports and systematic reviews were excluded, in line with the predefined eligibility criteria.

Systematic reviews were excluded because the primary objective of the present work was to analyze original imaging-based response criteria, follow-up timing, and modality-specific performance rather than to summarize aggregated outcomes across heterogeneous study designs.

Eligible studies included investigations conducted in adult patients with AK treated with field-directed therapies such as photodynamic therapy, 5-fluorouracil, imiquimod, tirbanibulin, or diclofenac. To be included, studies were required to report treatment response assessed using at least one of the following non-invasive techniques: dermoscopy, reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM), line-field confocal optical coherence tomography (LC-OCT), high-frequency ultrasound (HFUS), or Raman spectroscopy, with evaluations performed both before and after treatment.

Studies were excluded if they consisted solely of isolated case reports, addressed diagnostic performance without post-treatment follow-up, were conducted exclusively on non-human skin, or lacked a full-text version available in English or Italian.

2.3. Data Extraction and Synthesis

Study selection was performed independently by two reviewers (F.R. and G.P.). For each included study, data were extracted on study design, type of field-directed therapy, number of patients or lesions evaluated, follow-up timing, and imaging-based criteria used to define treatment response or persistence of disease.

Given the narrative and non-systematic nature of this review, several intrinsic methodological limitations are acknowledged. Study inclusion, although based on predefined criteria, was influenced by the quality of reporting, full-text availability, and heterogeneity in terminology used to index imaging techniques, resulting in an unavoidable risk of selection bias. Furthermore, substantial variability in acquisition protocols, device-specific parameters, and definitions of response across studies introduced marked heterogeneity, precluding quantitative comparison of outcomes and rendering formal meta-analysis inappropriate. Publication bias is also likely, as studies reporting higher diagnostic performance or favorable results may be preferentially published.

Results were therefore synthesized using a descriptive and comparative approach, with particular emphasis on the ability of each imaging modality to detect disease resolution or persistent subclinical alterations, and on their potential role within a personalized follow-up strategy for field cancerization.

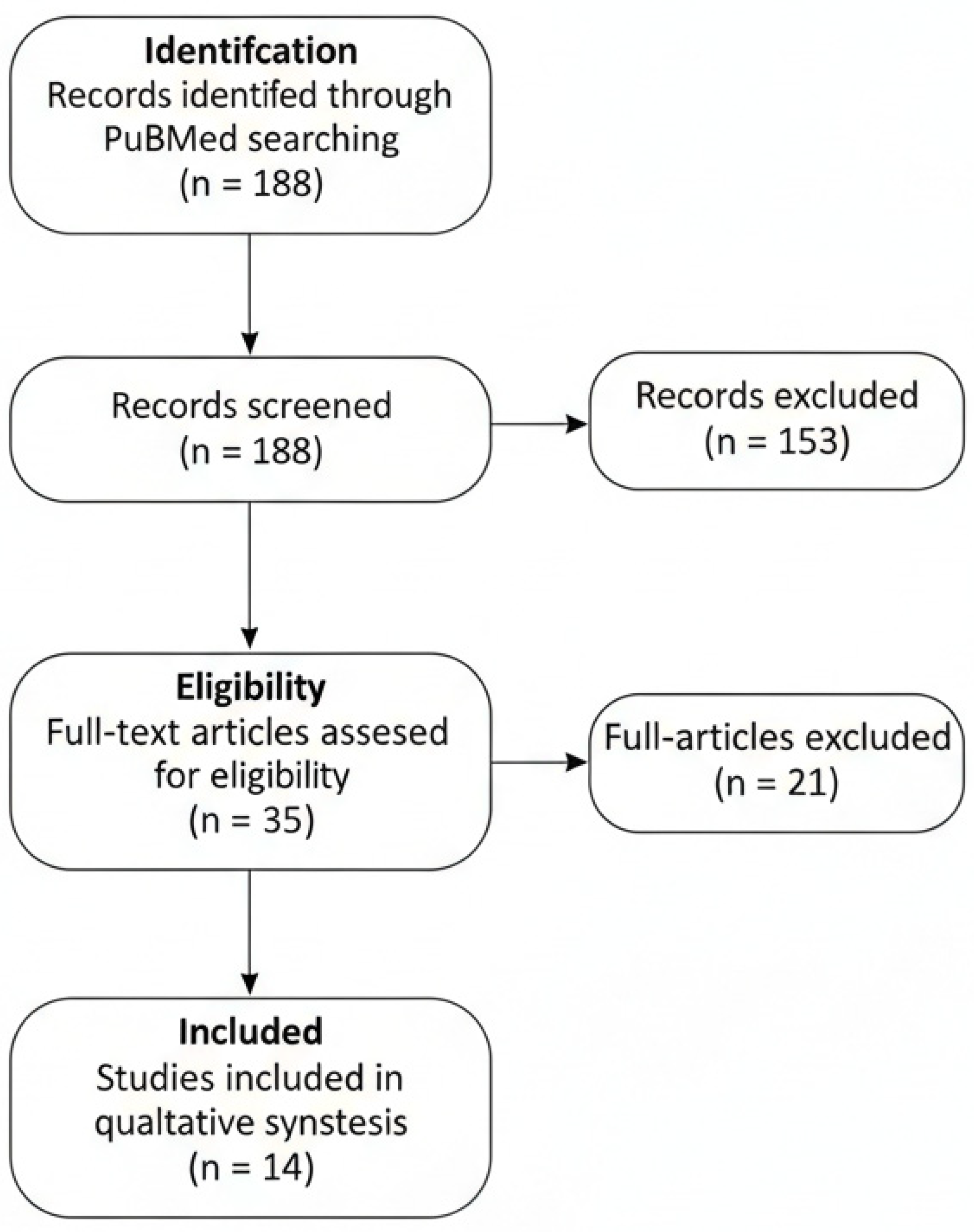

To enhance transparency and traceability of the study selection process, the phases of identification, screening, eligibility assessment, and inclusion were summarized using a PRISMA-adapted flow diagram, tailored to the requirements of a narrative review.

A limited number of key background references not retrieved through the structured search were manually added to provide contextual information on imaging techniques; these references were not included in the reviewed study pool.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection and Evidence Overview

The literature search identified a total of 188 records. After screening for study type, language, and exclusion of preprints, 35 articles remained eligible for full-text assessment. Of these, 14 studies met the predefined inclusion criteria by reporting a pre- and post-treatment evaluation using at least one non-invasive imaging modality and were therefore analyzed in detail (

Figure 1). Most available evidence derives from studies based on RCM and LC-OCT, whereas data on HFUS and Raman spectroscopy remain quantitatively limited.

3.2. Clinical Assessment and Dermoscopy: Strengths and Limitations

Clinical evaluation remains the first-line approach for follow-up after field-directed therapies in AK. In routine practice and in most registration trials, treatment success is commonly defined by the macroscopic regression of erythema, scaling, and surface roughness. However, several studies have demonstrated that clinical healing does not necessarily correspond to histological clearance, with persistence of subclinical disease reported within the cancerized field8.

Dermoscopy provides a second level of resolution, allowing visualization of structural disorganization beyond naked-eye inspection. Its widespread availability, rapid execution, and high reproducibility make it particularly suitable for systematic monitoring of both individual lesions and the surrounding field. High diagnostic accuracy has been reported for AK, with sensitivities up to 98.7% and specificities around 95%9.

From a diagnostic standpoint, dermoscopy improves discrimination between AK, pigmented AK (PAK), and SCC in situ through well-established criteria. Non-pigmented AKs typically display adherent white scales, an erythematous pseudonetwork, perifollicular keratinization, and the characteristic “strawberry pattern” whereas PAKs more often show gray–brown granules and globules, annular–granular structures, and an irregular pigmented pseudonetwork. SCC (both in situ and invasive) more frequently exhibits prominent hyperkeratosis, structureless white areas, irregular linear or glomerular vessels, and a higher degree of architectural disorganization.

Dermoscopy-associated signs of response include reduction or disappearance of keratin scales, attenuation of the erythematous pseudonetwork or strawberry pattern, resolution of superficial erosions or micro-ulcerations, and reduction of disorganized vascular structures. Owing to its immediacy, dermoscopy enables sequential assessment of post-treatment changes and may facilitate early detection of incomplete responses or progression toward SCC.

Nevertheless, dermoscopy may fail to detect minimal residual intraepidermal atypia or heterogeneous keratinocyte proliferation, particularly in initially thin lesions or after partially effective field therapies. As such, dermoscopy represents an excellent macroscopic and semiological tool, but is insufficient to definitively document biological resolution of disease10,11,12,13.

3.3. Reflectance Confocal Microscopy (RCM)

RCM enables in vivo visualization of epidermal microarchitecture and the papillary dermis with near-cellular resolution. In AK, multiple studies have shown that RCM can capture dynamic patterns of response to field-directed therapies.

Before treatment, typical RCM findings include mosaic hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis, disruption of the epidermal “honeycomb” pattern, keratinocyte atypia of variable degree and distribution (dyskeratosis), blurring or loss of dermo–epidermal junction (DEJ) definition, increased superficial vascularization, and scattered inflammatory cells at the DEJ14,15,16. Following effective treatment, RCM commonly demonstrates restoration of a regular honeycomb pattern, increased uniformity of keratinocyte size and shape, reduction or disappearance of atypical keratinocytes, decreased inflammatory infiltrate, and normalization of superficial vascular structures4,12,17,18,19,20,21,22.

Among RCM response criteria, it is possible to distinguish well-validated features, supported by histopathological correlation and prognostic relevance, from promising but less consolidated findings. Validated criteria include normalization of the honeycomb pattern, significant reduction of keratinocyte atypia, reconstitution of the DEJ, and disappearance of intraepidermal inflammatory cells. These parameters have shown reproducible association with histological clearance and reduced recurrence risk.

Other findings, such as changes in superficial vascular architecture, inflammatory dynamics, or subtle intraepidermal micro-variants, remain less consistently validated and require further investigation to establish their prognostic value.

Importantly, architectural normalization observed by RCM has been associated with a lower risk of recurrence20,23 supporting a prognostic, not merely diagnostic, role. In this context, RCM provides a functional surrogate of histological healing without the need for tissue sampling. Reported diagnostic performance of RCM in AK ranges from 79–100% sensitivity and 78–100% specificity24.

3.4. Line-Field Confocal Optical Coherence Tomography (LC-OCT)

LC-OCT combines features of confocal microscopy and conventional OCT, enabling three-dimensional visualization of epithelial structures with near-micrometric resolution, albeit with lower cellular detail than RCM. It is particularly suited for quantifying epidermal structural changes before, during, and after treatment.

In pre-treatment AK, LC-OCT typically reveals increased thickness of the stratum corneum and epidermis (hyperkeratosis with parakeratosis and acanthosis), an irregular DEJ profile, hyperreflective inflammatory cells at the DEJ, and marked keratinocyte heterogeneity in intermediate layers (dyskeratosis), consistent with histopathological correlations25. After treatment, progressive reduction of epidermal thickness, sharper and more continuous DEJ contours, increased keratinocyte uniformity, and decreased intraepidermal and junctional inflammatory cells have been documented in follow-up studies, particularly after tirbanibulin and other field therapies26,27.

From an operational perspective, it is essential to distinguish parameters directly available on the device from those requiring dedicated post-processing. In routine practice, LC-OCT currently allows direct measurement of basic structural features, most notably epidermal thickness derived from vertical scans. More advanced quantitative parameters, such as automated assessment of keratinocyte atypia or numerical estimation of DEJ regularity, are not yet available in real time and require post-processing through manufacturer software or dedicated algorithms.

Within this context, the PRO-score, a composite AI-derived index combining multiple LC-OCT morphological features into a single atypia score, represents a promising but still investigational tool, currently limited to post-processing workflows and not integrated into standard clinical practice29,30,31.

Recent studies on tirbanibulin-treated AK have reported early morphological normalization on LC-OCT (7–14 days), preceding visible clinical improvement typically observed at 4–8 weeks. Reported sensitivity and specificity for detecting AK-related structural abnormalities range from 85–90% and 82–89%, respectively25,26. These findings suggest that LC-OCT may identify subclinical residual disease and response dynamics earlier than dermoscopy and, in some settings, earlier than RCM, making it particularly valuable for short-course therapies.

3.5. High-Frequency Ultrasound (HFUS)

High-frequency ultrasound (HFUS) is a non-invasive imaging modality capable of exploring the superficial dermis at frequencies of approximately 20–50 MHz. Although it lacks cellular resolution, HFUS is particularly useful for assessing global changes within the cancerized field, especially after therapies such as PDT or topical 5-fluorouracil.

Pre-treatment HFUS findings typically include thickening of the subepidermal low-echogenic band (SLEB), a marker of chronic UV damage and collagen alteration, together with reduced echogenicity of the superficial dermis and, in some cases, non-quantifiable epidermal thickening, as reported in trials using HFUS as an outcome measure33.

Following effective field therapy, HFUS commonly demonstrates a progressive reduction in SLEB thickness, often detectable within 4–8 weeks, accompanied by increased dermal echogenicity, interpreted as an indicator of improved tissue quality and dermal matrix reorganization. These changes have been shown to correlate with clinical and dermoscopic improvement and may remain stable over time.

Despite its value in assessing field cancerization, HFUS has important limitations. Epidermal resolution is insufficient to identify residual keratinocyte atypia or confirm complete lesion clearance, rendering cellular assessment of treatment response impossible. The technique is of limited utility in thin or minimally hyperkeratotic AK, where ultrasonographic parameters may be subtle or undetectable. Moreover, the lack of standardized response criteria and the strong influence of baseline photodamage introduce substantial heterogeneity across studies.

Overall, HFUS is most informative in patients with marked chronic actinic damage, where improvement in global skin quality represents a relevant therapeutic goal alongside lesion clearance. Its role remains complementary to higher-resolution epidermal techniques such as RCM and LC-OCT and requires further standardization to contribute more robustly to response assessment.

3.6. Raman Spectroscopy: Emerging Optical Biomarkers

Table 1.

Summary of included studies on non-invasive imaging for monitoring treatment response in actinic keratosis.

Table 1.

Summary of included studies on non-invasive imaging for monitoring treatment response in actinic keratosis.

| First author, year |

Imaging technique |

Therapy |

Size |

Primary outcome |

Main findings |

| Banzhaf 2014 |

OCT |

imiquimod |

20 patients (11 AK) |

the ability of OCT to predict treatment outcome |

OCT showed thinning of AKs indicating effect of treatment |

| Fredman 2024 |

D-OCT |

daylight photodynamic therapy |

38 patients (62 AK) |

Quantitative vascular parameters on dynamic OCT to differentiate treatment-resistant vs. cleared AK. |

D-OCT holds potential to identify treatment-resistant AKs. |

| Themstrup 2014 |

OCT |

MAL-PDT |

18 patients (4 AK) |

describe the OCT morphology of in vivo NMSC lesions during PDT treatment and to investigate the use of OCT in evaluating the response of PDT treated NMSC lesions. |

OCT is most suitable in the diagnosis and follow-up of NMSC treatment. |

| Seyed Jafari 2016 |

RCM |

DL-PDT |

20 patients (40 AK) |

Use a new RCM atypia scoring system to evaluate efficacy of DL-PDT |

This study confirms that in vivo RCM technology might be an additional technique to monitor the efficacy of DL-PDT for AK |

| Ulrich 2010 |

RCM |

imiquimod |

11 patients |

applicability of RCM for noninvasive monitoring of AK |

RCM allows noninvasive monitoring of treatment response in vivo and permits early detection of subclinical AK |

| Qiao 2023 |

RCM |

PDT + microneedling, fractional CO2 laser, and cryotherapy |

129 patients |

Complete response rate |

RCM more sensitive than dermoscopy for identifying residual atypia. Shows superior cellular-level clearance with combination therapies, particularly cryotherapy + PDT. |

| Ishioka 2018 |

RCM |

5-fluorouracil |

50 lesions |

RCM accuracy, sensibility and specificity for actinic keratosis |

RCM is a non-invasive method capable of monitoring actinic keratosis therapeutic response to 5-fluorouracil, presenting efficacy comparable to histological examination |

| Pasquali 2018 |

RCM |

IM and cryotherapy |

26 patients |

RCM-monitored treatment response |

IM + Cryo shows fewer LSR; both sequences effective |

| Ruini 2019 |

RCT and OCT |

ingenol mebutate |

20 patients (120 lesions) |

evaluate the changes in the field cancerization undergoing treatment by combining RCM and OCT |

Both OCT and RCM allow the morphological representation of field cancerization including subclinical lesions and provide complementary information. |

| Richtig 2010 |

RCM |

Shave biopsy |

10 lesions |

applicability of RCM for the follow-up of AK after shave biopsy |

RCM might be a useful tool in the follow-up of AK after shave biopsy |

| Caccavale 2024 |

RCM |

n-DL-PDT without curettage but preceded by application of keratolytics |

39 patients |

evaluate efficacy, based on RCM assessments of the therapy |

curettage is not necessary to obtain the full treatment effect of n-DL-PDT |

| Arisi 2020 |

HFUS |

MAL-PDT, IMB, DHA |

90 patients |

Evaluate dermoscopical and high-frequency ultrasound (HFUS) changes after therapies |

MAL-PDT improves all HFUS features of chronic photodamages of the dermis of the skin underlying and surrounding the AK spots. |

| Ishioka 2015 |

RCM |

fluorouracil |

13 patients |

confocal microscopy enabled visualization of focal areas of atypical honeycomb pattern in the epidermis indicating therapeutic failure |

RCM may be a tool for diagnosis and therapeutic control of actinic keratosis |

| Scola 2012 |

OCT |

PDT and CO(2) |

20 patients |

To compare PDT and carbon dioxide (CO(2) ) LA in the management of multiple AK |

AK features as assessed by OCT imaging were also significantly reduced by both procedures. |

Raman spectroscopy enables acquisition of an in vivo molecular fingerprint of the skin, providing information on tissue biochemical composition. In the context of AK follow-up, this technique may detect changes related to keratinization, dysplasia, and inflammatory processes, potentially allowing monitoring of treatment response through dynamic spectral modifications.

Initial studies exploring Raman spectroscopy in post-treatment monitoring have reported preliminary response-associated patterns. In a case report7 and a study34, spectral analysis following PDT, tirbanibulin, or 5-fluorouracil revealed changes in bands attributed to elastin (≈1680–1690 cm−1) and tyrosine/keratin (≈1610–1620 cm−1). Progressive reduction of these signals, combined with multivariate models such as principal component analysis (PCA) or partial least squares (PLS), was preliminarily associated with biochemical regression of the lesion, in some cases preceding clinically visible changes.

While Raman spectroscopy represents a promising approach for defining a non-invasive biological endpoint complementary to morphological imaging, current evidence remains exploratory, limited to small cohorts, and lacks validated, reproducible criteria. Further controlled studies are required before routine clinical implementation can be considered.

4. Discussion

Assessing treatment response in actinic keratosis (AK) after field-directed therapies remains a central clinical challenge in the management of field cancerization. In both routine practice and clinical trials, clinical clearance is still the most frequently adopted endpoint; however, a substantial body of evidence indicates that visible normalization does not necessarily correspond to true biological or histological resolution. A study35 reported histological persistence in up to 60% of clinically “cleared” AK, highlighting a clinically relevant mismatch between macroscopic outcomes and the underlying intraepidermal disease status. This dissociation plausibly contributes to the variability in recurrence rates reported across field treatments such as photodynamic therapy (PDT), 5-fluorouracil, imiquimod, and tirbanibulin, where outcome estimates depend heavily on the definition of response and on the depth and sensitivity of post-treatment assessment.

Within this framework, dermoscopy remains an indispensable first-line tool. Its diagnostic performance at baseline is high (sensitivity up to 98.7% and specificity approximately 95%)9, and it is uniquely positioned for wide implementation due to accessibility, speed, and reproducibility. Dermoscopy also supports structured assessment of lesion morphology and facilitates early recognition of features suspicious for progression toward squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Nonetheless, its role in treatment-response monitoring is intrinsically constrained by the limited ability to detect minimal residual intraepidermal atypia or heterogeneous subclinical persistence within the treated field. In keeping with this limitation, Peppelman et al. reported histological persistence in approximately 40% of lesions no longer visible on dermoscopic examination. These observations support the concept that dermoscopy, while effective as a clinical decision tool, is not sufficient as a stand-alone surrogate of biological clearance when the clinical question is residual subclinical disease after field therapy.

High-resolution, non-invasive imaging techniques address this gap by providing objective or semi-objective criteria closer to histopathology, while maintaining a non-invasive workflow. Reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) is particularly relevant in this setting because it offers near-cellular visualization of epidermal architecture and superficial dermis and can document therapy-induced changes in a manner that is interpretable against known histologic correlates. Reported diagnostic performance for AK spans a sensitivity of 79–100% and specificity of 78–100%24. Beyond diagnosis, follow-up studies indicate that RCM detects persistent subclinical alterations in a clinically meaningful proportion of cases judged as cleared by clinical inspection, with higher concordance with histopathology than dermoscopy. Pellacani et al. observed that RCM can identify persistence in approximately 30–50% of clinically resolved cases. Importantly, the restoration of a regular honeycomb pattern and reduction of keratinocyte atypia have been repeatedly associated with histological clearance20,23, supporting the use of RCM-derived architectural normalization as a pragmatic surrogate endpoint for “biological response.” These data position RCM as a technique capable of moving response assessment beyond macroscopic appearance toward a microstructural definition that may better align with recurrence risk.

Line-field confocal optical coherence tomography (LC-OCT) occupies a complementary position. By combining high axial resolution with the ability to interrogate tissue in three dimensions, LC-OCT enables serial quantification of epidermal and junctional morphology while retaining a clinically feasible acquisition process. In clinical studies, LC-OCT has shown sensitivity around 85–90% and specificity approximately 82–89% for AK-related abnormalities25,26. A consistent finding across follow-up series is that LC-OCT may reveal structural normalization early after therapy initiation, in some reports within the first 1–2 weeks, potentially preceding the timepoint at which clinical normalization becomes apparent. This characteristic is particularly relevant in short-course regimens, where early discrimination between expected inflammatory remodeling and incomplete response may influence follow-up strategy. Also a report28 further supports the concept that dynamic OCT-based assessment can capture early reduction of epithelial alterations during tirbanibulin treatment. At the same time, it remains essential to distinguish what is currently achievable in routine LC-OCT workflows from what is only possible with advanced post-processing. Although basic structural measurements such as epidermal thickness can be derived directly from standard acquisitions, composite or automated indices of atypia (including AI-derived scores such as the PRO-score) are not uniformly available in real time and remain in validation phases in many settings. As such, LC-OCT can be framed as a high-resolution structural follow-up tool with strong potential for standardization, while avoiding overstatement regarding automated quantification until broader validation and implementation are available.

High-frequency ultrasound (HFUS) provides a different, complementary layer of information by focusing on dermal changes that reflect chronic photodamage and field remodeling rather than keratinocyte-level atypia. Several studies28 have described reductions of the subepidermal low-echogenic band (SLEB) on the order of 20–25% and increases in dermal echogenicity after PDT, correlating with improvement in the photo-damaged dermal matrix. Although formal sensitivity and specificity values for detecting subclinical residual AK are generally not available for HFUS, its contribution lies in quantifying field-level dermal recovery and offering a potential imaging correlate of “field improvement” beyond lesion clearance. This may be clinically meaningful in patients with extensive actinic damage, where therapeutic goals include not only clearance of visible AK but also reduction in the propensity to develop new lesions. Nevertheless, HFUS should be considered complementary rather than confirmatory for lesion-level clearance, because epidermal resolution is insufficient to directly evaluate residual intraepidermal atypia.

Raman spectroscopy represents an emerging approach aimed at capturing biochemical signatures of tissue state in vivo. Preliminary reports7,34 suggest that dynamic changes in spectral bands related to keratin, elastin, and inflammatory pathways may accompany, and in some instances precede, clinically apparent response. While this is conceptually attractive as a potential molecular surrogate endpoint, the evidence base is currently early-stage, often limited by small sample sizes, heterogeneous acquisition protocols, and limited reproducibility across devices and analytical pipelines. Accordingly, Raman should be positioned as an investigational modality with potential utility in research settings and trial endpoints, rather than as a technique ready for routine response assessment.

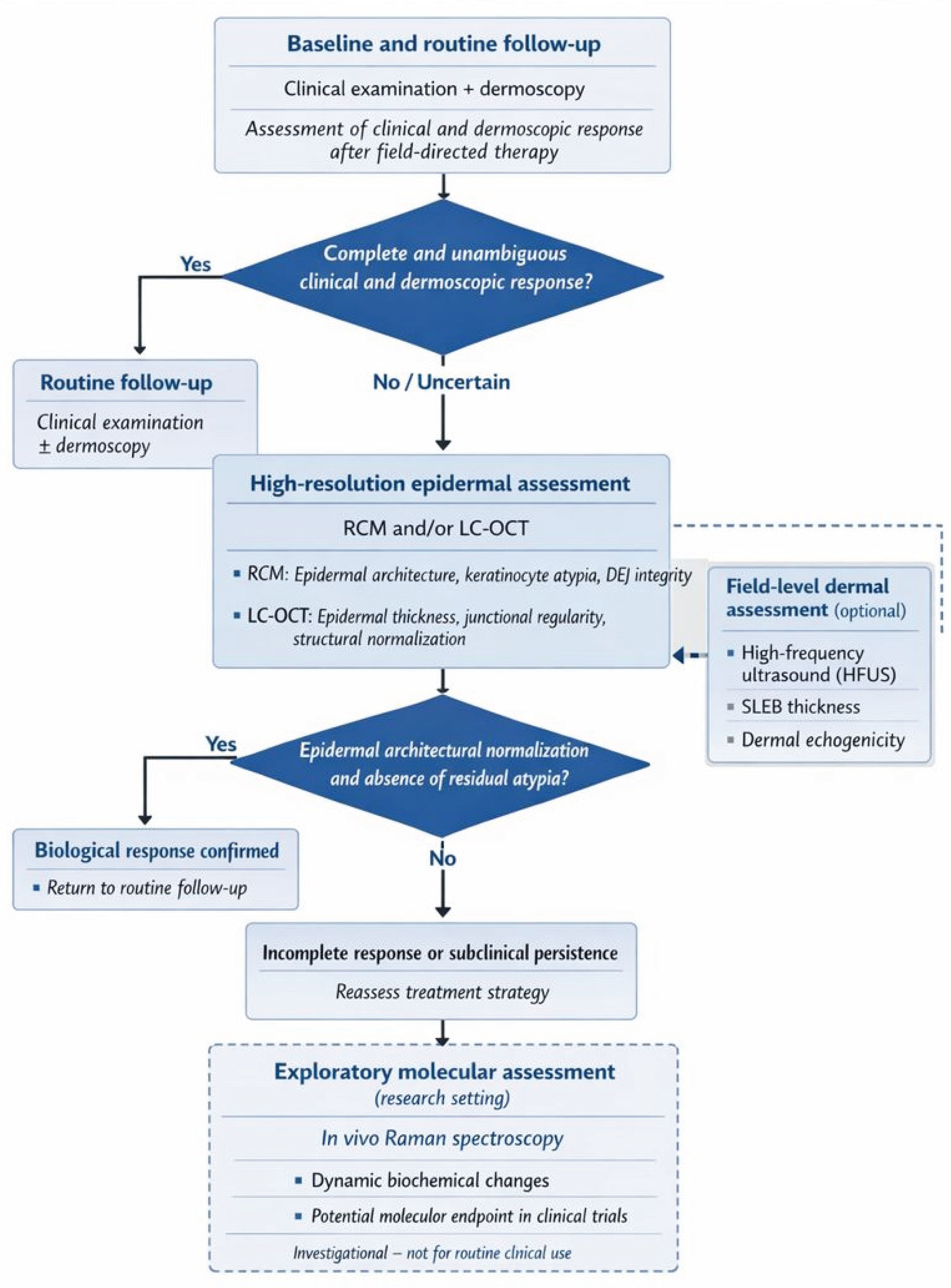

Taken together, these modalities should not be framed as interchangeable alternatives, but as tools with distinct strengths that can be integrated into a rational follow-up strategy. Clinical evaluation and dermoscopy remain the foundation for screening, baseline characterization, and routine follow-up. RCM and LC-OCT can be deployed when the clinical question is whether residual subclinical disease persists despite apparent clinical response, or when a higher-confidence, microstructural definition of response is required (e.g., high-risk sites, recurrent disease, immunosuppression, or equivocal post-treatment findings). HFUS can add value by characterizing dermal field remodeling and monitoring broader photodamage-related changes. Raman spectroscopy, at present, is best reserved for exploratory applications and for the development of future biochemical endpoints within controlled studies.

The implementation of non-invasive imaging in AK follow-up is associated with limitations that should be explicitly acknowledged. From a technical standpoint, marked hyperkeratosis, severe photodamage, and alterations of the dermo–epidermal junction may impair image quality and reduce the ability to detect subtle residual disease. From an organizational and economic standpoint, cost, limited availability to specialized centers, acquisition time, and the requirement for advanced training constitute relevant barriers to broad implementation. A further limitation is the lack of standardized acquisition protocols and response definitions across devices and research groups, which limits comparability and hampers the development of shared decision pathways. Finally, the current evidence base is frequently derived from monocentric cohorts with modest sample sizes and relatively short follow-up, which constrains the strength and generalizability of conclusions regarding recurrence prediction and long-term outcomes.

Future progress in this field will depend on standardization and validation. Priority directions include: (i) consensus definitions of imaging-based response criteria for each modality, anchored to clinically meaningful outcomes and, where appropriate, histological correlation; (ii) harmonized acquisition and reporting standards to improve reproducibility across centers; (iii) prospective multicenter studies designed to evaluate whether imaging-guided follow-up reduces recurrence, enables earlier identification of incomplete response, or optimizes retreatment timing; and (iv) careful evaluation of AI-assisted metrics (including LC-OCT composite scores) with transparent methodology, external validation, and clinically interpretable thresholds. Within this roadmap, a multimodal approach has the potential to improve the precision of response assessment beyond clinical clearance alone, while maintaining feasibility and proportionality in real-world dermatology workflows.

From a practical standpoint, these findings suggest that non-invasive imaging should be applied in a risk-adapted and question-driven manner rather than uniformly in all patients. In everyday clinical practice, most AK can continue to be managed and followed with clinical examination and dermoscopy alone. Advanced imaging modalities become most relevant when clinical response is equivocal, when treatment is performed on high-risk anatomical sites, or when patients present with factors associated with increased recurrence risk, such as extensive field cancerization or immunosuppression. In this context, selective integration of RCM or LC-OCT may enhance confidence in response assessment and inform retreatment decisions, while HFUS may support longitudinal monitoring of field recovery. Such a proportional approach balances diagnostic accuracy with feasibility and resource utilization, facilitating translation of multimodal follow-up strategies into routine dermatologic care. Based on these considerations, we propose a clinically oriented, multimodal follow-up algorithm designed to support post-treatment decision-making in actinic keratosis. This framework is intended as a conceptual and pragmatic tool, rather than a validated guideline, and should be applied in a risk-adapted, question-driven manner (

Figure 2).

Table 2.

Sensitivity, specificity and capability of non-invasive techniques in detecting subclinical AK after field therapy.

Table 2.

Sensitivity, specificity and capability of non-invasive techniques in detecting subclinical AK after field therapy.

| Method |

Sensitivity (%) |

Specificity (%) |

Subclinical Residue Detection/Notes |

Main Sources |

| Dermoscopy |

85–98.7 |

82–95 |

High diagnostic accuracy at baseline. Limited ability to detect subclinical persistence (~40% histologic residue with normal dermoscopy). |

Zalaudek 2013; Peppelman 2015 |

| Reflectance Confocal Microscopy (RCM) |

79–100 |

78–100 |

Most accurate technique for detecting subclinical residue. Identifies 30–50% persistence in clinically ’cleared’ AK. Architectural normalization correlates with histologic clearance. |

Malvehy 2016; Ishioka 2018; Longo 2017 |

| Line-Field Optical Coherence Tomography (LC-OCT) |

85–90 |

82–89 |

Detects minimal residual abnormalities; early structural normalization (7–14 days). Particularly useful for short-course therapies. |

Cinotti 2020; Lacarrubba 2023; Cantisani 2024 |

| High-Frequency Ultrasound (HFUS) |

n.d. |

n.d. |

Does not detect cellular atypia; quantifies dermal recovery (SLEB reduction 20–25%; echogenicity ↑ 15–20%). |

Crisan 2014; Pellacani 2016 |

| Raman spectroscopy |

80–92* |

78–90* |

Preliminary evidence only. Molecular bands (1610–1690 cm−1) predict early biochemical response. *Values from ML models.* |

Zhu 2024; Zhao 2024 |

5. Conclusions

Follow-up of actinic keratosis should extend beyond clinical inspection and dermoscopy, which document visible regression but do not reliably confirm biological clearance. Non-invasive imaging techniques - reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM), line-field confocal optical coherence tomography (LC-OCT), and high-frequency ultrasound (HFUS) - provide complementary information by improving detection of epidermal normalization, subclinical persistence, and changes within the cancerized field. Raman spectroscopy, although still exploratory, further expands this framework by offering access to tissue-level biochemical changes.

An effective follow-up strategy is therefore multimodal, with each technique fulfilling a specific role: RCM for near-cellular assessment of keratinocyte atypia, LC-OCT for quantitative structural evaluation, HFUS for dermal field remodeling, and Raman spectroscopy as a potential molecular endpoint in research settings. Integrated use of these modalities can enhance response assessment and reduce the risk of unrecognized residual disease.

Future efforts should focus on standardizing response criteria, validating imaging endpoints in multicenter studies, and developing robust morphological and biochemical biomarkers, including those supported by artificial intelligence, to enable more reliable and sustainable monitoring of actinic keratosis in clinical practice.

Author Contributions

Gianluca Pistore conducted the literature search, wrote the original draft of the manuscript, prepared tables and figures, and developed the final flowchart. Luca Ambrosio contributed to manuscript writing, participated in the preparation of tables and figures, and contributed to the development of the final flowchart. Francesco Ricci conceptualized the work, conducted the literature search, defined the eligibility criteria, critically revised the manuscript, and contributed to the final flowchart. Antonio Di Guardo critically revised the manuscript. Luca Fania critically revised the manuscript, served as corresponding author, and contributed to the final flowchart. Anna Rita Panebianco, Giovanni Di Lella, Claudio Conforti, Giovanni Pellacani, Francesco Moro, and Paolo Marchetti critically revised the manuscript. Damiano Abeni critically revised the manuscript and contributed specifically to the Materials and Methods section. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article..

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| TLA |

Three letter acronym |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

References

- Marques E, Chen TM. Actinic Keratosis. [Updated 2023 Aug 17]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-.

- Worley, B., Harikumar, V., Reynolds, K. et al. Treatment of actinic keratosis: a systematic review. Arch Dermatol Res 315, 1099–1108 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Conforti C, Ambrosio L, Retrosi C, et al. Clinical and Dermoscopic Diagnosis of Actinic Keratosis. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2024;14(S1):e2024147S. [CrossRef]

- Curiel-Lewandrowski, C.; Myrdal, C.N.; Saboda, K.; Hu, C.; Arzberger, E.; Pellacani, G.; Legat, F.J.; Ulrich, M.; Hochfellner, P.; Oliviero, M.C.; et al. In Vivo Reflectance Confocal Microscopy as a Response Monitoring Tool for Actinic Keratoses Undergoing Cryotherapy and Photodynamic Therapy. Cancers 2021, 13, 5488. [CrossRef]

- Thamm, J.R., Welzel, J. and Schuh, S. (2025), AI-based and LC-OCT-guided follow-up of actinic keratoses under treatment with tirbanibulin 1%. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol, 39: e35-e38. [CrossRef]

- Korecka, K.; Slian, A.; Czajkowska, J.; Dańczak-Pazdrowska, A.; Polańska, A. The Application of High-Frequency Ultrasonography in Post-Therapeutic Assessment of Actinic Keratosis After Photodynamic Therapy. Cancers 2024, 16, 3778. [CrossRef]

- Rongyi Zhu, Shiyi Yang, Na Yu, Rongjun Zhang, Minfeng Wu, Raman spectroscopy assisted diagnosis and photodynamic therapy efficacy evaluation of actinic keratosis: Case report, Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy, Volume 53, 2025, 104624, ISSN 1572-1000. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H., Won, C.Y., Kim, G.M. and Kim, S.Y. (2014), Dermoscopic features of actinic keratosis and follow up with dermoscopy: A pilot study. J Dermatol, 41: 487-493. [CrossRef]

- Huerta-Brogeras M, Olmos O, Borbujo J, Hernández-Núñez A, Castaño E, Romero-Maté A, Martínez-Sánchez D, Martínez-Morán C. Validation of dermoscopy as a real-time noninvasive diagnostic imaging technique for actinic keratosis. Arch Dermatol. 2012 Oct;148(10):1159-64. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitfalls in the clinical and dermoscopic diagnosis of pigmented actinic keratosis Zalaudek, Iris et al. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, Volume 53, Issue 6, 1071 - 1074.

- Xiaoqin Y, Chan H, Long W, et al. Dermoscopic Monitoring for Treatment and Follow-Up of Actinic Keratosis With 5-Aminolaevulinic Acid Photodynamic Therapy. Technology in Cancer Research & Treatment. 2018;17. [CrossRef]

- Benati, E., Longhitano, S., Pampena, R., Mirra, M., Raucci, M., Pellacani, G. and Longo, C. (2020), Digital follow-up by means of dermatoscopy and reflectance confocal microscopy of actinic keratosis treated with Imiquimod 3.75% cream. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol, 34: 1471-1477. [CrossRef]

- Pampena R, Condorelli A, Cornacchia L, et al. Treatment monitoring of 5-fluorouracil 0.5%/salicylic acid 10% lesion-directed therapy for actinic keratosis using dermoscopy and in-vivo reflectance confocal microscopy. Dermatologic Therapy. 2020; 33:e13744. [CrossRef]

- Pellacani G, Ulrich M, Casari A, Prow TW, Cannillo F, Benati E, Losi A, Cesinaro AM, Longo C, Argenziano G, Soyer HP. Grading keratinocyte atypia in actinic keratosis: a correlation of reflectance confocal microscopy and histopathology. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015 Nov;29(11):2216-21. Epub 2015 Aug 14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moscarella E, Rabinovitz H, Zalaudek I, Piana S, Stanganelli I, Oliviero MC, Lallas A, Ardigo M, Cota C, Catricalà C, Mazzoni L, Pellacani G, Argenziano G, Longo C. Dermoscopy and reflectance confocal microscopy of pigmented actinic keratoses: a morphological study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015 Feb;29(2):307-314. Epub 2014 Apr 22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghassi, David et al. Confocal laser microscopic imaging of actinic keratoses in vivo: A preliminary report. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, Volume 43, Issue 1, 42 - 48.

- López Estebaranz JL, Pampín Franco A, Gamo Villegas R, Floristán U. Monitoring Ingenol Mebutate Gel Treatment of Actinic Keratoses by Reflectance Confocal Microscopy. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017 May 8;97(5):646-648. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazur E, Reich A. Photodynamic Therapy is an Effective Treatment of Facial Pigmented Actinic Keratosis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2023 Jun;13(6):1265-1276. Epub 2023 May 10. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Seyed Jafari SM, Timchik T, Hunger RE. In vivo confocal microscopy efficacy assessment of daylight photodynamic therapy in actinic keratosis patients. Br J Dermatol. 2016 Aug;175(2):375-81. Epub 2016 May 30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malvehy J, Alarcon I, Montoya J, Rodríguez-Azeredo R, Puig S. Treatment monitoring of 0.5% 5-fluorouracil and 10% salicylic acid in clinical and subclinical actinic keratoses with the combination of optical coherence tomography and reflectance confocal microscopy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016 Feb;30(2):258-65. Epub 2015 Nov 4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maier T, Cekovic D, Ruzicka T, Sattler EC, Berking C. Treatment monitoring of topical ingenol mebutate in actinic keratoses with the combination of optical coherence tomography and reflectance confocal microscopy: a case series. Br J Dermatol. 2015 Mar;172(3):816-8. Epub 2015 Jan 22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruini, Cristel & Hartmann, Daniela & Bastian, Mike & Ruzicka, Thomas & French, Lars & Berking, Carola & Braunmühl, Tanja. (2019). Non-invasive monitoring of subclinical and clinical actinic keratosis of face and scalp under topical treatment with ingenol mebutate gel 150 mcg/g by means of reflectance confocal microscopy and optical coherence tomography: New perspectives and comparison of diagnostic techniques. Journal of Biophotonics. 12. [CrossRef]

- Ishioka P, Maia M, Rodrigues SB, Lellis RF, Hirata SH. In vivo Confocal Laser Microscopy for monitoring of actinic keratosis treatment: a comparison with histopathologic assessment after treatment with topical 5% 5-fluorouracil. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018 Jul;32(7):1155-1163. Epub 2018 Jan 23. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, K.P., Peppelman, M., Hoogedoorn, L. et al. The current role of in vivo reflectance confocal microscopy within the continuum of actinic keratosis and squamous cell carcinoma: a systematic review. Eur J Dermatol 26, 549–565 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Cinotti E, Tognetti L, Fiorani D, et al. Line-field confocal optical coherence tomography for the diagnosis of actinic keratosis: correlation with histopathology. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(9):1993–2000.

- Lacarrubba F, Verzì AE, Micali G. Line-field confocal optical coherence tomography for the assessment of actinic keratosis treated with tirbanibulin 1% ointment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023;37(4):e587–e589.

- Thamm K, Ruini C, Ardigo M, et al. Artificial intelligence-assisted LC-OCT monitoring of tirbanibulin-treated actinic keratosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2025.

- Cantisani, C., Musolff, N., Azzella, G., Gargano, L., Di Guardo, A., Longo, C., Guida, S., Rossi, G., Rovaldi, E., Rega, F., Cocci Grifoni, G., Kiss, N., Ambrosio, L., Pellacani, G., Tirbanibulin 1% Ointment Effectiveness for Actinic Keratosis Treatment Evaluated by Dynamic Optical Coherence Tomography, Dermatologic Therapy, 2024, 1018395, 7 pages, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Pathak GN, Sanabria B, Caetano VD, Rafiq B, Rao BK. Evaluation and treatment monitoring of actinic keratosis using line-field confocal optical coherence tomography. Skin Res Technol. 2024 May;30(5):e13726. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Daxenberger F, Deußing M, Eijkenboom Q, Gust C, Thamm J, Hartmann D, French LE, Welzel J, Schuh S, Sattler EC. Innovation in Actinic Keratosis Assessment: Artificial Intelligence-Based Approach to LC-OCT PRO Score Evaluation. Cancers (Basel). 2023 Sep 7;15(18):4457. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Thamm JR, Welzel J, Schuh S. AI-based and LC-OCT-guided follow-up of actinic keratoses under treatment with tirbanibulin 1. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2025 Jan;39(1):e35-e38. Epub 2024 May 4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pathak P, et al. Practical considerations in follow-up of actinic keratosis with line-field confocal optical coherence tomography. Skin Res Technol. 2024; (online ahead of print).

- Arisi M, Zane C, Polonioli M, Tomasi C, Moggio E, Cozzi C, Soglia S, Caravello S, Calzavara-Pinton I, Venturini M, Rossi MT, Calzavara-Pinton PG. Effects of MAL-PDT, ingenol mebutate and diclofenac plus hyaluronate gel monitored by high-frequency ultrasound and digital dermoscopy in actinic keratosis - a randomized trial. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020 Jun;34(6):1225-1232. Epub 2020 Jan 6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao J, Lin K, Xu Y, et al. Improving skin cancer detection by Raman spectroscopy using convolutional neural networks and data augmentation. Front Oncol. 2024;14:1320220.

- Ferrándiz C, Malvehy J, Guillén C, Ferrándiz-Pulido C, Fernández-Figueras M. Precancerous Skin Lesions. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017 Jan-Feb;108(1):31-41. English, Spanish. Epub 2016 Sep 20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulrich M, Krueger-Corcoran D, Roewert-Huber J, Sterry W, Stockfleth E, Astner S. Reflectance confocal microscopy for noninvasive monitoring of therapy and detection of subclinical actinic keratoses. Dermatology. 2010;220(1):15-24. Epub 2009 Nov 11. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malvehy J, Pellacani G, Segura S, et al. Monitoring field cancerization treatment with reflectance confocal microscopy and high-definition optical coherence tomography. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30(6):1041–1049.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).