1. Introduction

Dogs show tremendous variation between breeds, as the result of careful selection over time and rigorous breed standards. As has been demonstrated for coat color (Brancalion et al., 2022) and coat length (Housley & Venta, 2006), simple genetics explain most of the variation seen. For dog breeds there are three main coat variations that are factored into breed standards; coat color, hair length and hair type. Because breed standards have specific hair length, incorrect hair length can be a reason for excluding dogs from breed programs.

It was discovered in 2006 that hair length in dogs is due to variations in the

FGF5 gene (Housley & Venta, 2006). The wild type variant of the

FGF5 gene produces short hair and any combination of the known mutations in the

FGF5 gene results in dogs with a long hair phenotype. In other species such as cats, donkeys, and humans,

FGF5 also has been found to play a crucial role in hair length (Drögemüller et al., 2007; Higgins et al., 2014; Legrand et al., 2014). To date, in dogs five different variants have been discovered named Lh1 to Lh5 (see

https://omia.org/OMIA000439/9615/ (Nicholas, 2025)). Variant Lh1 is found in exon 1, Lh2, Lh3, and Lh4 are nucleotide changes in exon 3, and Lh5 is a variant in intron 1 (Dierks et al., 2013). For more details on these variants, see

Table 1.

These five FGF5 variants (Lh1–Lh5) have been used to predict the hair length phenotype in dogs, but recent Tibetan Mastiff cases showed discrepancies between the observed hair phenotype and the results of the standard Lh1–Lh5 genotyping. As Tibetan Mastiffs are known for their thick and dense coats with medium to long hair, a retrospective analysis of data from the FGF5 gene exon regions was performed to discover whether other DNA variants were present that could account for this discrepancy.

2. Materials and Methods

Animals. Twenty-four Tibetan Mastiff dogs and one mixed breed dog were sent in for testing for FGF5 variants. Of these dogs, twenty-two of the Tibetan Mastiff dogs and the mixed breed dog showed hair length longer than that predicted by their FGF5 genotype and were selected for an in-depth analysis of the FGF5 exonic regions after obtaining owner consent. Hair length for a subset of these 23 dogs was measured (in inches) at the shoulders using a ruler. In addition, genotype data for the known and new FGF5 variants for another 714 dogs was also collected for comparison.

DNA extraction and sequencing. Genomic DNA was extracted from buccal-swab samples (DNA Genotek Inc., Stittsville, ON, Canada) using the Puregene Extraction Kit following the manufacturer’s protocol (QIAGEN, Inc., Germantown, MD, USA). DNA sequencing libraries were prepared using manufacturer’s protocols from 150 ng of genomic DNA using the Twist Library Prep Kit EF 2.0 kit with the Twist Universal Adapter kit (Twist Bioscience, San Francisco, CA, USA). Subsequently an overnight hybridization capture reaction, with 16 samples per pool, was performed with the Standard Hybridization Reagent Kit (Twist Bioscience, San Francisco, CA, USA) using manufacturer’s protocol with the addition of canine Hybloc DNA (Applied Genetics, Melbourne, FL, USA). Sequencing was performed on a P2 flow cell using 2 × 150 bp sequencing on a NextSeq1000 instrument (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) as per manufacturer’s protocol. Probe sequences for the

FGF5 exons in which the known and novel variants are located are provided in Supplemental

Table 1.

Data analysis. All sequence reads were trimmed of adapter sequences using cutadapt. The resulting sequences had base call quality scores ≥ Q30 and read depth >40× for all regions under investigation after alignment to canFam6.0 (Dog10K_Boxer/Tasha) (Jagannathan et al., 2021) using BWA-MEM2 (Vasimuddin M. et al., 2019). After alignment to the genome, the data was processed using an in-house variant caller pipeline based on samtools (Danecek et al., 2021) and the genotype result for the coat, color, health, parentage, and ancestry were reported out in vcf format. For this current report, Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) version 2.16.2 (Robinson et al., 2011) was then used to screen the resulting bam files for the presence of unknown variants in the

FGF5 coding region on chromosome 32. All genome positions in this communication are based on canFam6.0 unless otherwise noted. Novel variants were analyzed for predicted significance using PolyPhen-2 (

http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/) and SIFT (

https://sift.bii.a-star.edu.sg/).

For a global analysis, data for the known (Lh1-Lh5) and new long hair alleles (Lh6-Lh9) was extracted from vcf files for another 714 previously genotyped animals and used to assess allele frequencies and breed specificities.

3. Results

For the twenty-three dogs with a discrepancy between the actual and predicted phenotype based on their FGF5 genotype, we discovered four putative new functional variants in the coding region of the FGF5 gene. To ascertain whether these variants were present in other dogs, we extracted the genotypes for these nine variants in total from the respective bam files for 714 additional dogs (Supplemental Table 3). All variants were covered by a minimum of 40x read depth for these samples. The Lh1 allele was the most frequent with an allele frequency of 30%, while Lh7, Lh8 and Lh9 were a distant second with approx. 1% frequency. The latter could be biased due to the fact this study contained many Tibetan Mastiffs. Of the putatively new variants, only Lh7 was seen in another breed, the Anatolian shepherd.

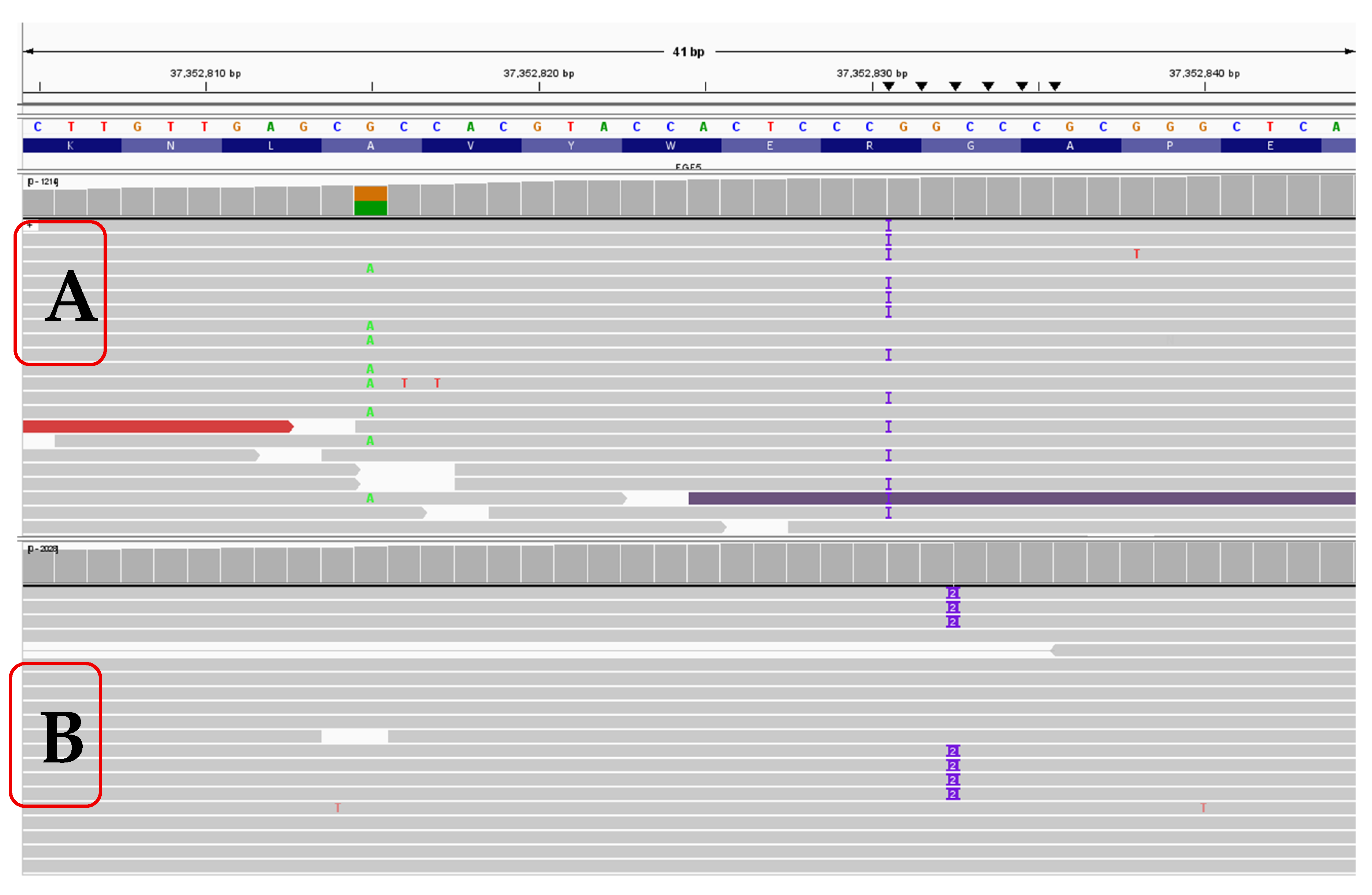

Putative Lh6 variant in dog of unknown heritage

A dog with a mixed ancestry of Poodle, Rottweiler, German Shepherd, and Cocker Spaniel (See Supplemental

Figure 1) was genotyped and showed only a single

FGF5 long-hair allele (Lh2/Sh). Under a recessive model, this genotype should not produce long hair; nevertheless, the dog possessed long hair with hair length at shoulders and breaches measuring >2 inches. (See

Figure 1A). Analysis of the raw bam files using IGV showed this dog had a single copy of the Lh2 variant, NC_006614.4:g.37352815G>A, and a previously unknown variant just in front of β sheet 9 of the

FGF5 protein, with an insertion of a G nucleotide at NC_006614.4:g.37352830-37352831insG; NM_001048129:c.562_563insC; NP_001041594.1:p.(R188fxX12) (

Figure 2, Supplemental

Figure 2). This variant causes a frameshift change. Based on the insertion of a C nucleotide in the coding sequence, this variant is tentatively assigned p.R188PfsX12. This C insertion variant in the coding sequence is in very close proximity and similar to the Lh4 variant, which is an insertion of CC in the coding sequence, at position NC_006614.4:g.37352832-37352833insGG, and is also located within the 16 bp deletion of the Lh3 variant. We tentatively call this G insertion variant Lh6. This variant was not seen in any of the other 738 dogs analyzed.

Tibetan Mastiff

From twenty-four Tibetan Mastiff dogs tested for known

FGF5 variants, two dogs were homozygous Lh1/Lh1 genotype and thus a long-haired phenotype. For the other 22 dogs the genotype results, based on known alleles of the

FGF5 gene, would be indicative of a short-haired phenotype for their coat length as they either had a single known variant (N=9), or no known variant at all (N=13). However, the hair length was measured at a minimum of 5 inches at the shoulder (Supplemental

Figure 3), and the shawl (i.e., manes around the neck) exceeded 7 inches in length. Because Tibetan Mastiffs are phenotypically long-haired (as per AKC standards), review of the bam files for the region containing the

FGF5 gene was performed and three new putative long hair variants were discovered.

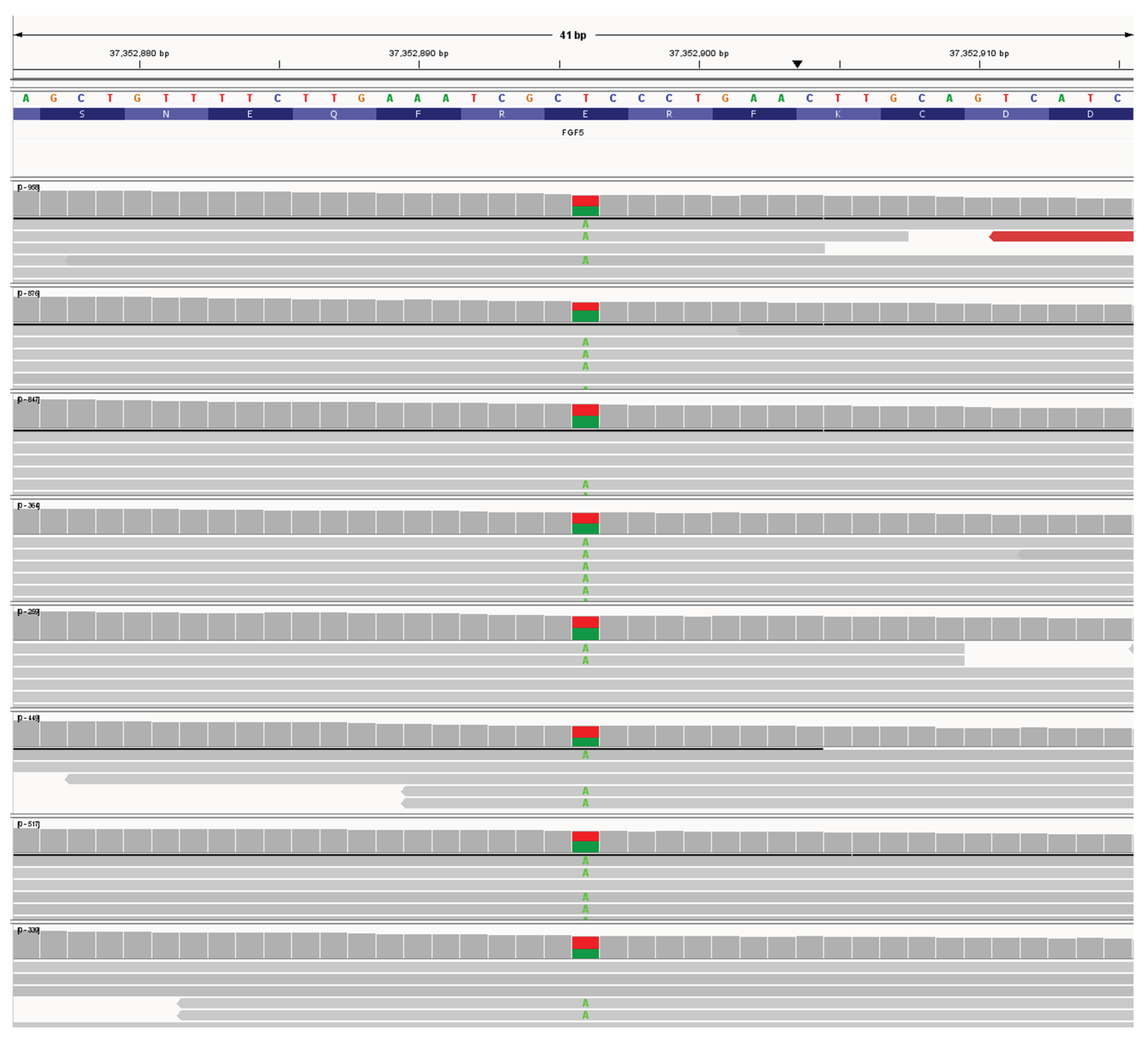

Putative Lh7 variant

There were 13 dogs heterozygous for NC_006614.4:g.37352896T>A; NM_001048129:c.497A>T NP_001041594.1:p.(E166V). See

Figure 3. The variant NC_006614.4:g.37352896 is a T>A variant in exon 3 causing a Glutamic acid to Valine substitution in amino acid 166 (See Supplemental

Figure 4) in β sheet 7 of the

FGF5 protein. Substitution of a glutamic acid with a valine likely results in a significant change in the protein structure as glutamic acid is hydrophilic whereas valine is a hydrophobic amino acid. Analyzing the variant NC_006614.4:g.37352896T>A by PolyPheno2 (score 0.999) and SIFT analysis (score .000) showed this variant as “Probably damaging”. This variant, tentatively called Lh7, was also seen in an Anatolian Shepherd. An example of an Lh7/Lh9 dog is shown in

Figure 1B.

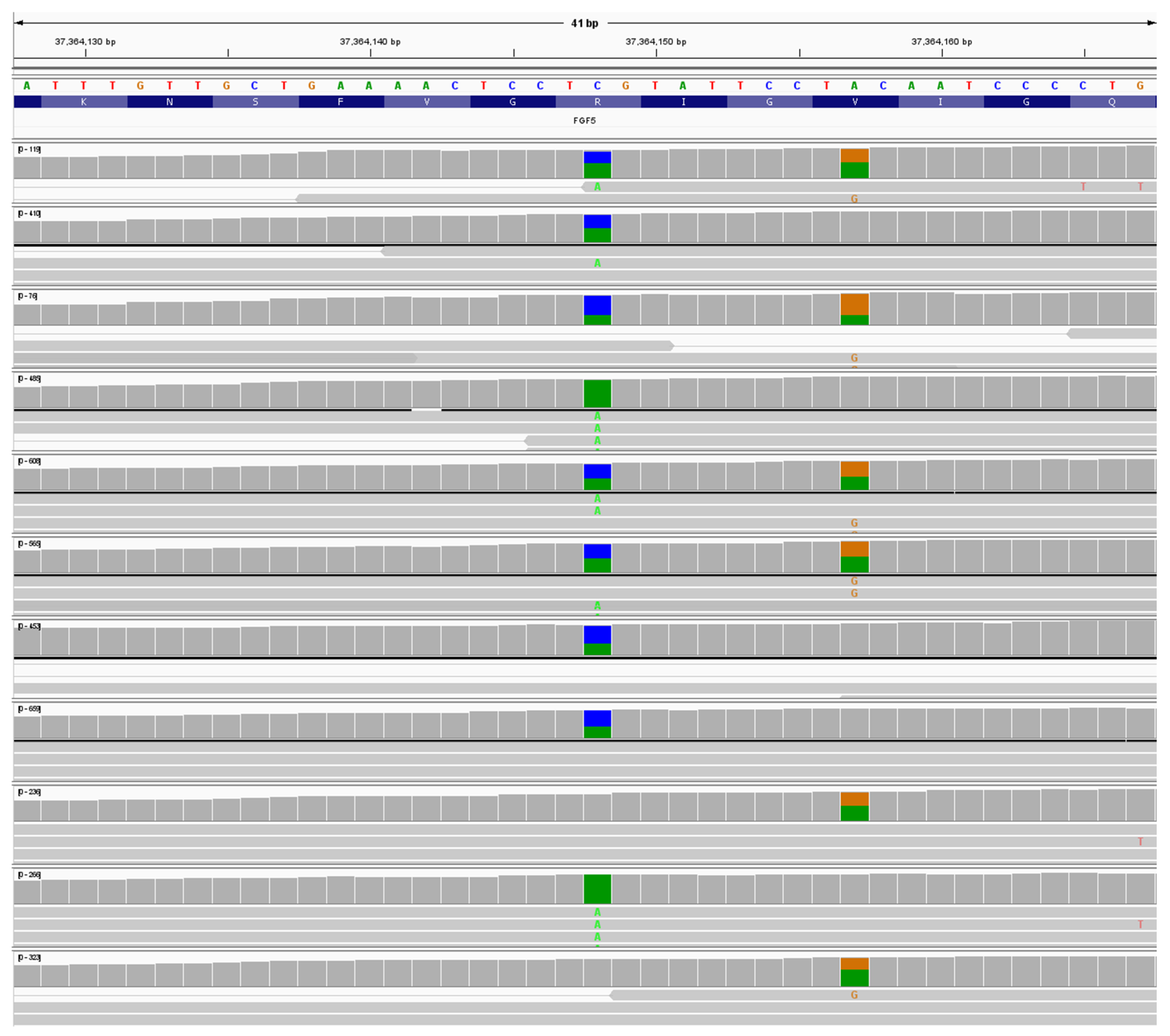

Putative Lh8 variant

There were 13 heterozygous dogs, and two homozygous dogs for NC_006614.4:g.37364148C>A; NM_001048129:c.410G>T; NP_001041594.1:p.(R137L). See

Figure 4. The variant NC_006614.4:g.37364148 is a Cytosine to Adenosine variant causing an Arginine to Leucine substitution in amino acid 136 (See Supplemental

Figure 5) in β sheet 4 of the

FGF5 protein. Analysis of the resulting protein with PolyPheno2 (score 0.991) and SIFT analysis (score .001) showed this variant as “Probably damaging”. This variant is tentatively called Lh8 and was not seen in any of the other 715 dogs analyzed. An example of an Lh8/Lh8 dog is shown in

Figure 1C.

Putative Lh9

Lastly 11 dogs were heterozygous and one dog was homozygous for NC_006614.4:g.37364157A>G; NM_001048129:c.398T>C; NP_001041594.1:p.(V133A). See

Figure 4. The variant NC_006614.4: g.37364157 is an A>G variant causing a Valine to Alanine substitution in amino acid 133 (V133A) (See Supplemental Figure 6) in β sheet 4 of the

FGF5 protein. PolyPheno2 (score 1.000) and SIFT analysis (score .000) showed this variant as “Probably damaging”. This variant is tentatively called Lh9 and was not seen in any of the other 715 dogs analyzed. An example of an Lh9/Lh9 dog is shown in

Figure 1D.

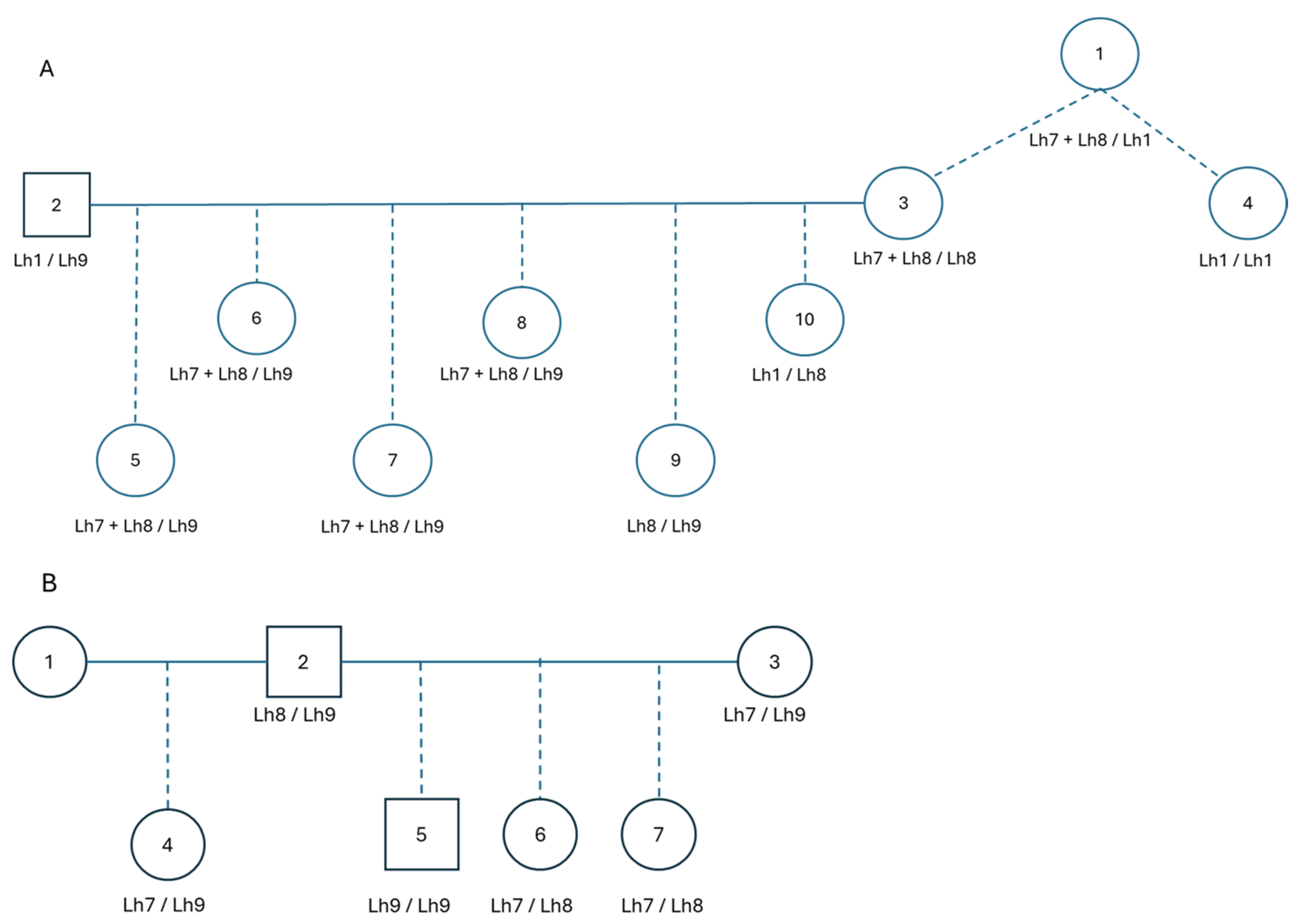

The majority of the dogs had only 2 variants present, either a known variant from Lh1 through Lh5, and a new variant from Lh6 through Lh9, or only new variant alleles Lh6 through Lh9. As the FGF5 variants are known to be recessive, i.e., only cause long hair if at least 2 variants are present, it is highly likely these new variants are causative variants as evidenced by thirteen of the 24 long-haired Tibetan Mastiffs showing only a combination of the new putative alleles Lh6 through Lh9.

Additionally, eight dogs presented three

FGF5 variants in their genotype results. As can be seen in

Figure 5, there were families where either three (A) or two (B) variants are segregating in the pedigree. As the pedigree in

Figure 5A showed animal 4 to be homozygous Lh1/Lh1, it was deduced that the Lh7 and Lh8 variants in animal 1 were on the same parental chromosome. This was also observed in its offspring (animal 3) and its offspring (animals 5-10). The variants Lh7 and Lh8 were also present without other variants on a parental chromosome, as can be seen in the family in

Figure 5B.

4. Discussion

Currently there are five known long hair variants for

FGF5 that have been observed in dog breeds with long hair phenotypes. However, our analysis of 24 long-haired Tibetan Mastiff dogs, and one mixed breed dog, showed only two dogs homozygous for Lh1, nine heterozygous for Lh1 only, one dog heterozygous for Lh2, and 13 dogs without a known Lh1 through Lh5 allele (Supplemental

Table 2). The majority of these dogs (23 of 25 dogs) would be considered short-haired based on the known

FGF5 long hair variants. Owner feedback, pictures of the dogs in question, and measurement of the hair length clearly showed that the animals in question were phenotypically long-haired. We therefore analyzed the whole

FGF5 exonic region and found three different variants present in Tibetan Mastiff dogs that are all predicted to have a severe impact on the protein structure according to PolyPhen-2 and SIFT (

Table 2). In the one dog of mixed breed that was genotyped as Lh2/n, analysis of the

FGF5 coding regions showed the animal harbored an insertion of a G nucleotide in the vicinity of the Lh4 allele, the latter being an insertion of two C nucleotides. The effect of this insertion is a similarly altered protein sequence. See Supplemental Figure 7 for an alignment of all nine variants.

Unexpectedly, eight dogs presented with three variants in the FGF5 gene. In six dogs it was deduced from the pedigree information that the Lh7 and Lh8 were on the same parental chromosome, approx. 11 kb apart. The other two dogs, based on pedigree analysis, were related to the six dogs within 2-3 generations and it was assumed they also carried the Lh7 and Lh8 on the same chromosome. This may present a problem for genotyping as dogs that carry a Lh7 and Lh8 variant could be carrying both variants on the same chromosome. A similar situation has been observed for the B locus, where the bc and bd variants have been found to be on the same chromosome in certain breeds (Letko & Drögemüller, 2017).

The four new variants presented here are likely not as prevalent as some of the previously identified alleles, but will help in providing more accurate phenotype predictions for hair type in certain breeds that have been derived in part from the Tibetan Mastiff. Tibetan Mastiffs are an ancient breed and may have been brought into Europe in the 1300s. They are a founder animal for large breeds such as Anatolian Shepherd, Old English Shepherd, Rottweiler and Saint Bernard (Li et al., 2011), and as such these new alleles might be present in these breeds too, as was shown for the Anatolian Shepherd (

Table 3). All the prior known

FGF5 variants Lh1 - Lh5 as well as the newly discovered variants Lh6-Lh9 are located in or near the β sheets of the

FGF5 protein (Supplementary Figure 7). These β sheets are the structures within the FGF5 protein that allow it to fold correctly. Alterations to these β sheets likely inhibit the correct folding and render the protein less effective at its primary function of hair cycle regulation.

5. Conclusion

Our study has identified four new variants in the FGF5 gene in dogs that possessed long hair but they were reported as short-haired using genotypes composed of known variants Lh1 through Lh5 variants. Although the long hair variants in the FGF5 gene inherit as an autosomal recessive trait, there have been reports of dogs where an incomplete dominant inheritance was expected based on the five known variants. Perhaps screening for these (or other) new variants may reveal they may be missing variants. The new alleles Lh7 through Lh9 have only been found in dogs of Tibetan Mastiff ancestry and more studies are warranted in larger sample sets to see their real prevalence. In the case of the Lh6 allele in the mixed breed dog, examining a larger cohort is needed. This dog was of mixed Poodle, Rottweiler, German Shepherd and Cocker Spaniel ancestry, all breeds known to carry Lh1. Overall, genotyping these new variants in larger dog populations will provide better understanding of their breed prevalence.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.E.E.; methodology, R.E.E.; software, G.F., T.R., C.K.; validation, R.E.E., G.F., and R.C.; formal analysis, R.E.E., R.C., C.K. and G.F.; investigation, R.E.E., R.C., and G.F.; resources R.E.E., C.L.; data curation, R.E.E., R.C., and T.R.; writing—original draft preparation, R.E.E.; writing—review and editing, R.E.E., C.L., R.C., T.R., C.K., G.F.; visualization, R.E.E.; supervision, R.E.E.; project administration, R.E.E. and C.L.; funding acquisition, C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All experiments and obtained dog samples followed the International Guiding Principles for Biomedical Research Involving Animals.

Ethics Statement

The dogs in this study were privately owned and saliva samples for diagnostic purposes were provided by, and with the consent of, their owners. The research did not involve invasive or harmful experiments on living animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The variant data for this study have been deposited in the European Variation Archive (EVA) at EMBL-EBI under accession number PRJEB98564.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Deborah Mayer, Abby Parr, April Slack, and Taylor Steele, collectively “the dog owners” who provided the dog pictures and the dog samples. Without your dogs and your willingness to help, none of this would be possible.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors are affiliated with AlphaDogDNA by Etalon, Inc., which offers diagnostic testing for coat color, ancestry and disease testing.

References

- Brancalion, L.; Haase, B.; Wade, C. M. Canine coat pigmentation genetics: a review. In Animal Genetics; John Wiley and Sons Inc, 2022; Vol. 53, Issue 1, pp. 3–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danecek, P.; Bonfield, J. K.; Liddle, J.; Marshall, J.; Ohan, V.; Pollard, M. O.; Whitwham, A.; Keane, T.; McCarthy, S. A.; Davies, R. M. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. GigaScience 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dierks, C.; Mömke, S.; Philipp, U.; Distl, O. Allelic heterogeneity of FGF5 mutations causes the long-hair phenotype in dogs. Animal Genetics 2013, 44, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drögemüller, C.; Rüfenacht, S.; Wichert, B.; Leeb, T. Mutations within the FGF5 gene are associated with hair length in cats. Animal Genetics 2007, 38, 218–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, C. A.; Petukhova, L.; Harel, S.; Ho, Y. Y.; Drill, E.; Shapiro, L.; Wajid, M.; Christiano, A. M. FGF5 is a crucial regulator of hair length in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2014, 111, 10648–10653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Housley, D. J. E.; Venta, P. J. The long and the short of it: Evidence that FGF5 is a major determinant of canine ’hair’-itability. Animal Genetics 2006, 37, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jagannathan, V.; Hitte, C.; Kidd, J. M.; Masterson, P.; Murphy, T. D.; Emery, S.; Davis, B.; Buckley, R. M.; Liu, Y. H.; Zhang, X. Q.; Leeb, T.; Zhang, Y. P.; Ostrander, E. A.; Wang, G. D. Dog10k_boxer_tasha_1.0: A long-read assembly of the dog reference genome. Genes 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legrand, R.; Tiret, L.; Abitbol, M. Two recessive mutations in fgf5 are associated with the long-hair phenotype in donkeys. Genetics Selection Evolution 2014, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letko, A.; Drögemüller, C. Two brown coat colour-associated TYRP variants (bc and bd) occur in Leonberger dogs. Animal Genetics 2017, 48, 732–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, X.; Pan, Z.; Xie, Z.; Liu, H.; Xu, Y.; Li, Q. The origin of the Tibetan Mastiff and species identification of Canis based on mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit i (COI) gene and COI barcoding. Animal 2011, 5, 1868–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholas, F. W.T. I.; S. I., H. Online Mendelian Inheritance in Animals (OMIA) 2025.

- Robinson, J. T.; Thorvaldsdóttir, H.; Winckler, W.; Guttman, M.; Lander, E. S.; Getz, G.; Mesirov, J. P. Integrative Genomics Viewer. Nature Biotechnology 2011, 29, 2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasimuddin, M.; Sanchit, M.; Heng, L.; Aluru, S. Efficient Architecture-Aware Acceleration of BWA-MEM for Multicore Systems. IEEE Parallel and Distributed Processing Symposium (IPDPS), 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).