Submitted:

14 January 2026

Posted:

16 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Designing sensor infrastructure providing room-level localization accuracy above 95% using infrared technology.

- Developing a three-stream data architecture with end-to-end latency below 10 seconds for critical events, bandwidth efficiency (over 70% reduction), and maintaining full time resolution (1-second granularity).

- Implementing edge computing with local machine learning on specialized hardware for real-time anomaly detection without cloud dependency.

- Analyzing architectural feasibility of federated learning for joint model development across multiple institutions.

- Validating technical performance through real-world residential deployment and analyzing economic viability through cost modeling.

2. Related Work

2.1. Clinical Context and Sensor-Based Approaches

2.2. Sensor Modalities and Architectures

2.3. Indoor Localization Technologies

Room-Level Localization

2.4. Edge Computing for Health Monitoring

2.5. Federated Learning for Privacy-Preserving Healthcare

2.6. Existing Home Monitoring Systems

2.7. Gap Analysis

- 6.

- Three-stream data architecture – a new pipeline system simultaneously meets requirements for real-time visualization (1-minute aggregates), machine learning model training (lossless event logs with 1-second resolution), and low latency for critical events (under 7 seconds end-to-end). The architecture achieves 41.2% bandwidth reduction while preserving complete temporal information.

- 7.

- Edge ML on standard hardware – local inference on ESP32-S3 microcontrollers with latency under 50 ms is demonstrated, enabling critical event detection (falls) without cloud infrastructure dependency. This provides real-time response and represents significant advantage over existing systems.

- 8.

- Federated training architecture – a monitoring system designed for inter-institutional collaboration while strictly maintaining confidentiality is presented. The approach addresses GDPR-imposed restrictions. Although validated only in simulated environment, it establishes conceptual and technical foundations for future real-world implementation.

- 9.

- Economic feasibility – estimated costs of €490 for initial implementation and €55 monthly operation are 5–10 times lower than existing research systems, making the solution suitable for large-scale implementation in real clinical and social settings.

3. System Architecture

3.1. Architectural Requirements

3.1.1. Functional Requirements

3.1.2. Technical Performance Requirements

3.1.3. Confidentiality and Security Requirements

3.1.4. Regulatory Requirements

3.1.5. Economic Viability Requirements

3.1.6. Clinical Applicability Requirements

3.2. Hardware Components

3.2.1. Wearable Sensor Devices

3.2.2. Edge Computing Gateways

3.3. Software Architecture

3.3.1. Edge Gateway Software

3.3.2. Cloud Infrastructure

3.4. Three-Tier Data Architecture

3.4.1. Stream 1: Aggregated Statistical Descriptors

3.4.2. Stream 2: Compressed Event Logs

3.4.3. Stream 3: Critical Real-Time Alerts

3.4.4. Derivative Aggregates

3.5. Deduplication with Multiple Gateways

3.5.1. Deduplication of Aggregated Descriptors (Stream 1)

3.5.2. Merging Event Logs (Stream 2)

3.5.3. Deduplication of Critical Alarms (Stream 3)

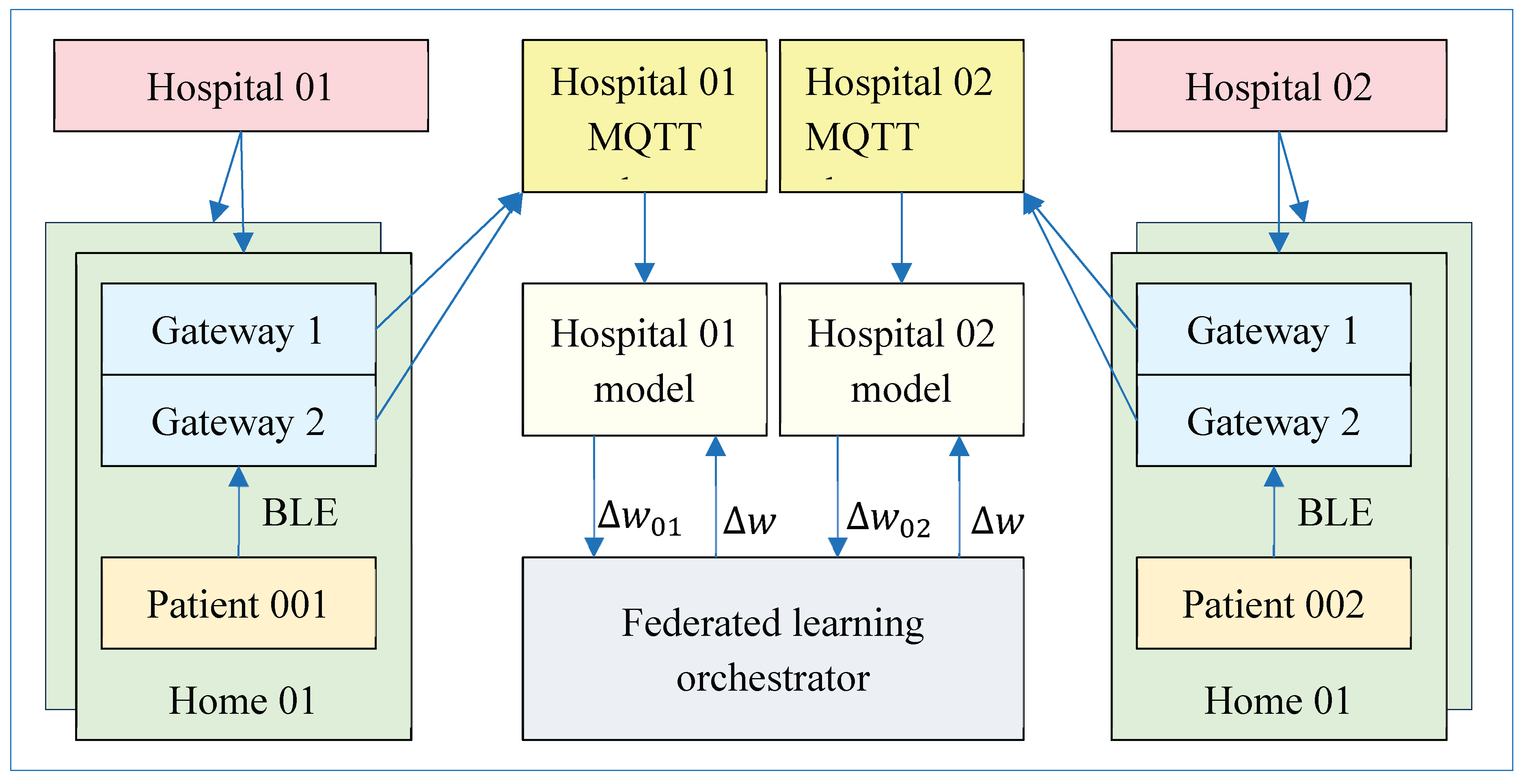

4. Federated Learning Design

4.1. Motivation and Requirements

4.2. Architecture of the Federated Learning System

4.2.1. Federated Learning Orchestrator

4.2.2. Local Training Servers

- Feature extraction from MongoDB hourly_aggregates or event logs collections for training set. Features include statistical moments of motor activity, spatial indicators, circadian parameters, and behavioral anomalies (episodes of long-term immobility, nocturnal activity).

- Local model training on institutional dataset for fixed number of epochs (typically 5-10). Deep recurrent neural network (LSTM) architecture with two layers of 64 and 32 units, dropout layers with probability 0.3 for regularization, and dense output layer for risk classification is used. Model is trained with Adam optimizer (learning rate = 0.001) and binary cross-entropy loss.

- Parametric update calculation: After local training, server calculates difference between local weights

- and global weights

- 4.

- This parametric update (typically ~200 KB for LSTM model) is serialized and sent to orchestrator via secure gRPC channel.

4.2.3. Federated Averaging Algorithm

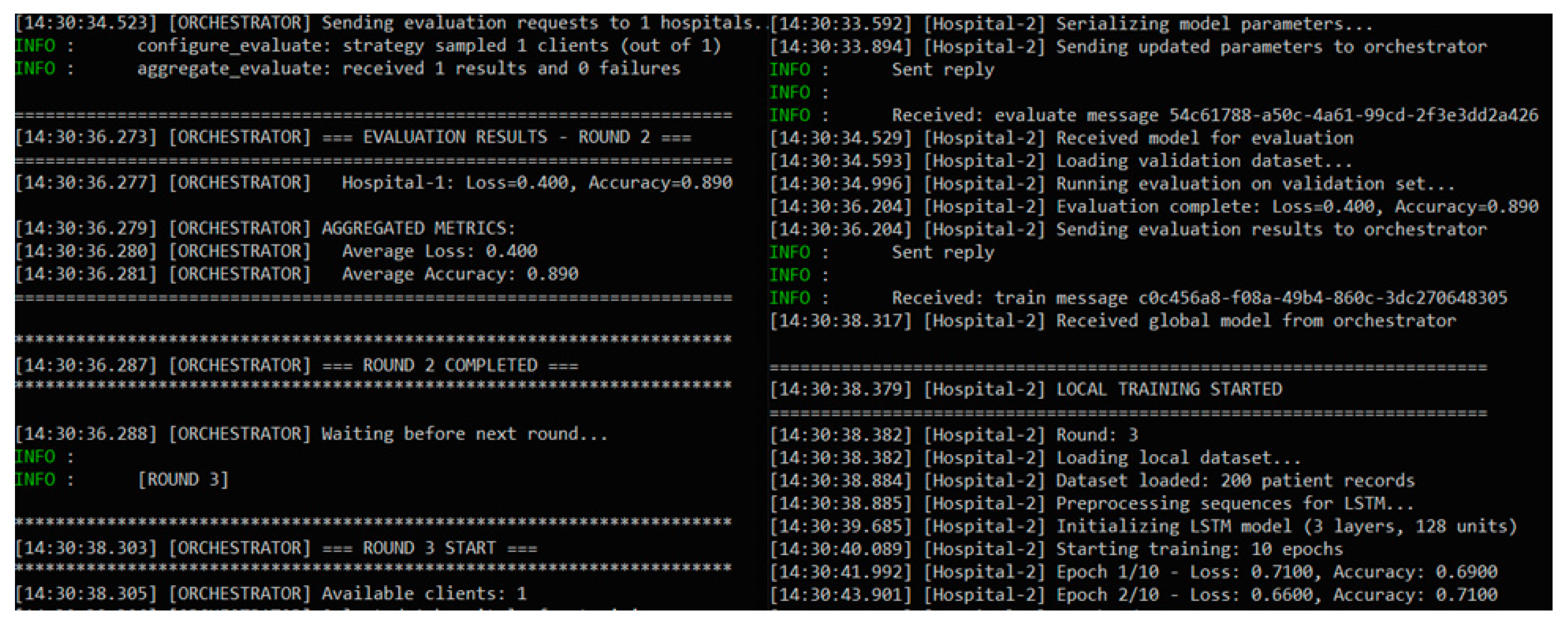

4.3. Implementation with the Flower framework

4.3.1. Architectural Advantages of Flower

4.3.2. Client Implementation

- 5.

- get_parameters() retrieves current parameters of local model as list of NumPy arrays. This operation is called at beginning of each round when orchestrator wants to obtain current state of local model.

- 6.

- fit(parameters, config) accepts global parameters from orchestrator, updates local model, performs local training for configured number of epochs, and returns updated parameters along with metadata (number of examples used, local loss). Only parameter updates leave institution—raw data and gradients remain local.

- 7.

- evaluate(parameters, config) evaluates global model on local validation set and returns quality metrics (accuracy, loss). This allows orchestrator to track global performance without accessing data.

4.3.3. Server Configuration

4.3.4. Communication Efficiency

- Downlink (orchestrator → institutions): 5 rounds × 3 institutions × 200 KB = 3 MB;

- Uplink (institutions → orchestrator): 5 rounds × 3 institutions × 200 KB = 3 MB;

- Total: 6 MB for complete federated process.

4.4. Confidentiality Guarantees

4.4.1. Communication Efficiency

4.4.2. Transport Level Encryption

4.4.3. Protection Against Byzantine Attacks

- Statistical filtering excludes updates that are statistical outliers by calculating Euclidean distance between each pair of updates and rejecting updates with median distance above certain threshold.

- Robust aggregation uses algorithms such as Krum (selects update with smallest sum of distances to nearest neighbors) or Trimmed Mean (excludes most extreme α% updates before averaging) instead of direct averaging.

- Reputation system tracks historical client performance and reduces weights of institutions whose updates consistently worsen global validation accuracy.

5. Technical Validation

5.1. Scope and Objectives of Validation

- Localization accuracy - verification of infrared system to achieve room-level localization accuracy.

- BLE communication characteristics - measurement of packet delivery reliability, RSSI, and coverage.

- Compression efficiency - validation of network traffic reduction while maintaining information completeness.

- Deduplication performance - assessment of accuracy in multi-gateway configurations.

- End-to-end latency - verification of requirement for under 10 seconds for critical event delivery.

- Architectural feasibility of federated learning - demonstration of federated learning in simulated environment.

5.2. Experimental Setup

5.2.1. Test environment

5.2.2. Hardware Implementation

5.2.3. Participants

5.3. Technical Results

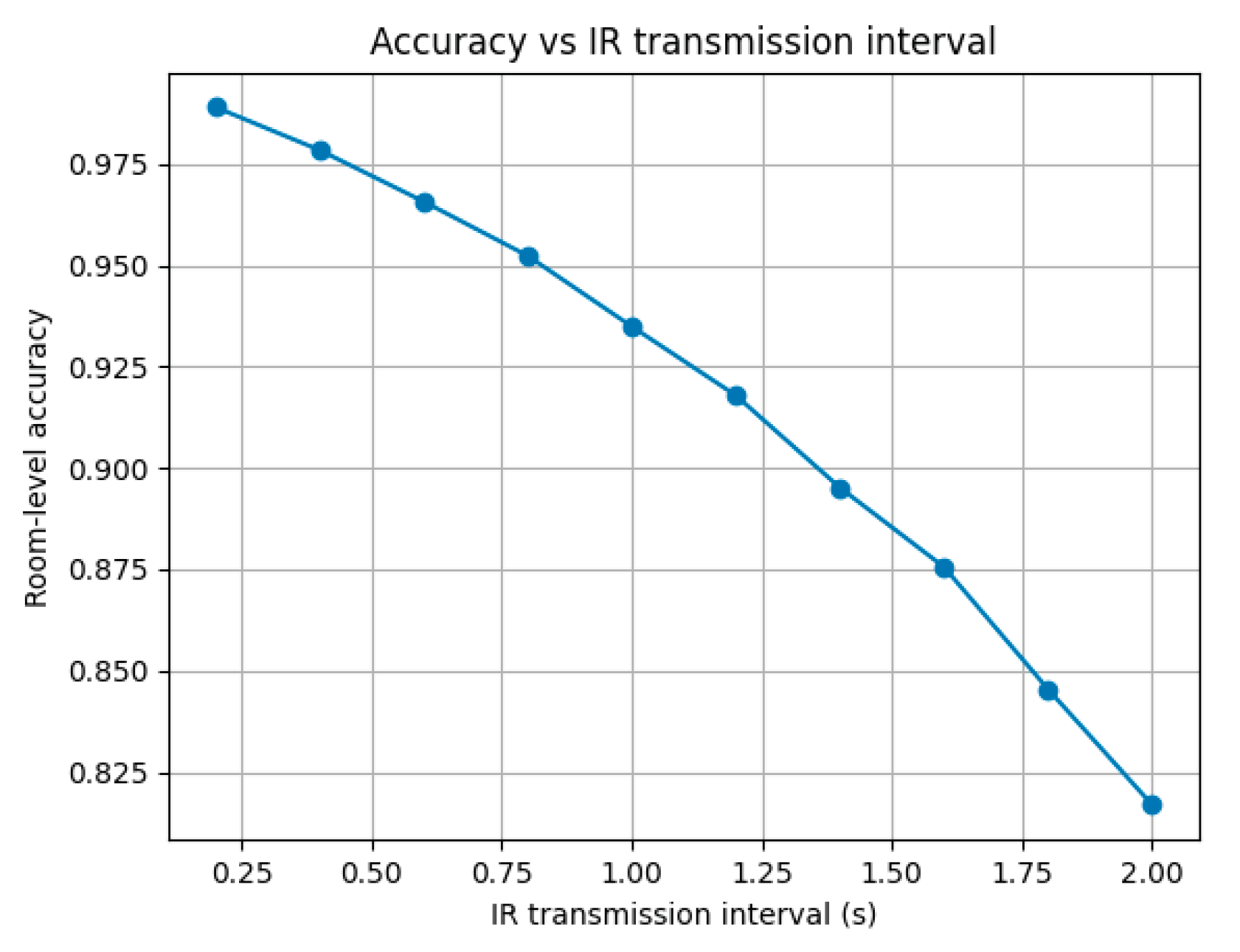

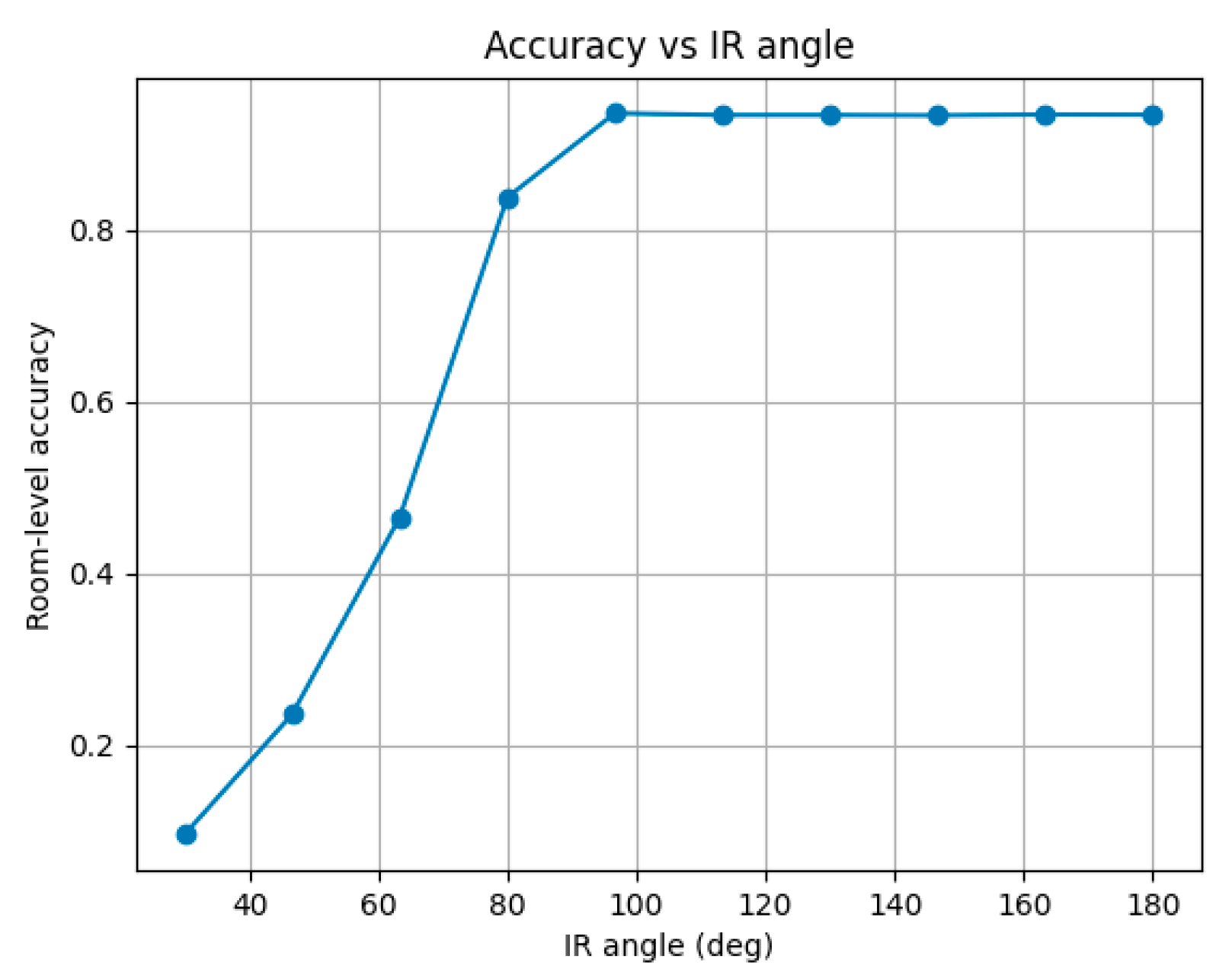

5.3.1. Accuracy of Infrared Localization

- Generate

- random initial positions uniformly in room.

- For each position, simulate exponentially distributed stay time

- 3.

- Discretize time with Δt and apply logic for and TTL.

- 4.

- Accuracy is estimated as fraction of time during which coincides with actual visitor position.

5.3.2. BLE Communication

5.3.3. Effectiveness of the Three-Channel Architecture

5.3.4. Deduplication Performance

5.3.5. End-to-End Latency

5.3.6. Architectural Proof-of-Concept for Federated Learning

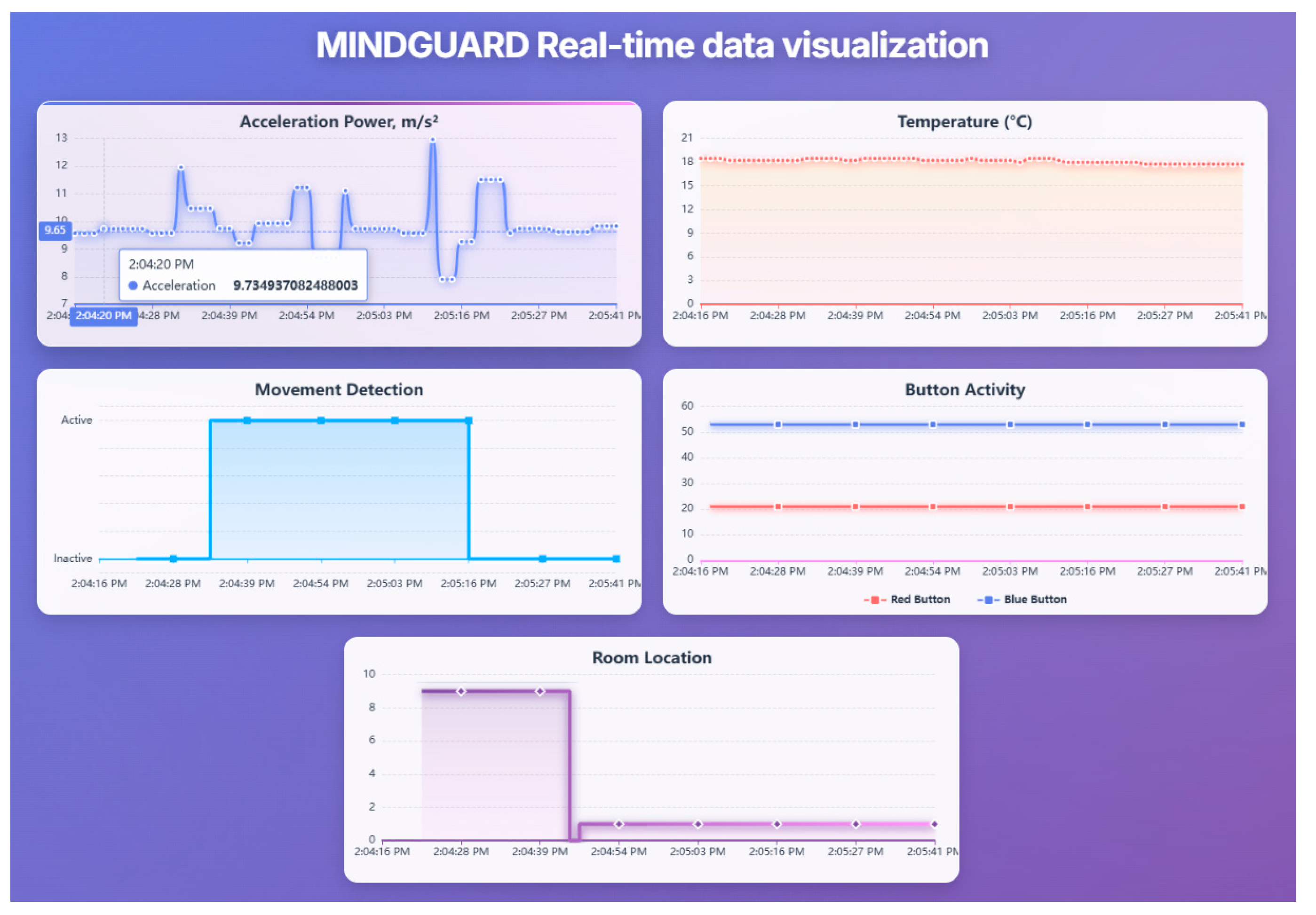

5.3.7. Real-Time Visualization of Data from Wearable Devices

6. Discussion

6.1. Key Technical Contributions

6.2. Positioning Relative to the Current State

6.3. Limitations and Guidelines for Future Development

6.3.1. Current Technical Limitations

6.3.2. Guidelines for Clinical Implementation

- Phase 1: Extended technical validation (6–12 months) – testing with 50–100 participants in real, diverse home environments for minimum three months continuous operation, covering different home types and demographic profiles (ages 65 to over 85, different education levels and technological literacy). Includes systematic failure analysis with targeted provocation of edge cases (battery depletion, connectivity loss, extreme usage patterns) and assessment of long-term hardware component reliability.

- Phase 2: Clinical pilot study (12–18 months) – ethics committee-approved protocol with ~150 participants in three groups: 50 individuals with MCI, 50 with mild dementia, 50 healthy controls. Includes baseline and quarterly neuropsychological assessments (MMSE, MoCA, CERAD-Plus) and reference clinical diagnosis. Effectiveness assessment covers diagnostic indicators (sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive value) for MCI classification versus healthy controls and analysis of predictive ability for MCI to dementia within 12 months.

- Phase 3: Multicenter federated deployment (18–24 months) – real federated training between ≥5 institutions, each with cohort of 50–100 patients. Objectives are technical integration in heterogeneous institutional IT environments, demonstration that federated learning model achieves equal or higher accuracy versus single-institution models, official confidentiality audit confirming GDPR compliance, and proof of operational stability with continuous operation over six months without critical incidents.

- Phase 4: Priority technical improvements – integration of PPG sensor for cardiovascular monitoring, optional GPS module for outdoor tracking (periodic mode for energy efficiency), and implementation of Byzantine-fault-tolerant aggregation methods (Krum, Trimmed Mean) with differential privacy mechanisms providing formal guarantees for data protection.

6.3.3. Open Research Questions

6.4. Broader Impact and Applicability

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

References

- World Health Organization. Dementia. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia, 2023.

- McKhann, G.M.; Knopman, D.S.; Chertkow, H.; Hyman, B.T.; Jack, C.R.; Kawas, C.H.; Klunk, W.E.; Koroshetz, W.J.; Manly, J.J.; Mayeux, R.; et al. The Diagnosis of Dementia Due to Alzheimer’s Disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association Workgroups on Diagnostic Guidelines for Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimer’s and Dementia 2011, 7, 263–269. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, T.; Nonaka, T.; Ohtani, R.; Hasegawa, M.; Hori, Y.; Tomita, T.; Kurita, R. Hindering Tau Fibrillization by Disrupting Transient Precursor Clusters. Neuroscience Research 2025, 220. [CrossRef]

- Nasreddine, Z.S.; Phillips, N.A.; Bédirian, V.; Charbonneau, S.; Whitehead, V.; Collin, I.; Cummings, J.L.; Chertkow, H. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A Brief Screening Tool for Mild Cognitive Impairment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2005, 53, 695–699. [CrossRef]

- Jack, C.R.; Bennett, D.A.; Blennow, K.; Carrillo, M.C.; Dunn, B.; Haeberlein, S.B.; Holtzman, D.M.; Jagust, W.; Jessen, F.; Karlawish, J.; et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a Biological Definition of Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimer’s and Dementia 2018, 14, 535–562.

- Dubois, B.; Hampel, H.; Feldman, H.H.; Scheltens, P.; Aisen, P.; Andrieu, S.; Bakardjian, H.; Benali, H.; Bertram, L.; Blennow, K.; et al. Preclinical Alzheimer’s Disease: Definition, Natural History, and Diagnostic Criteria. Alzheimer’s and Dementia 2016, 12, 292–323.

- Kaye, J.; Mattek, N.; Dodge, H.H.; Campbell, I.; Hayes, T.; Austin, D.; Hatt, W.; Wild, K.; Jimison, H.; Pavel, M. Unobtrusive Measurement of Daily Computer Use to Detect Mild Cognitive Impairment. Alzheimer’s and Dementia 2014, 10, 10–17. [CrossRef]

- Müller, K.; Fröhlich, S.; Germano, A.M.C.; Kondragunta, J.; Agoitia Hurtado, M.F.D.C.; Rudisch, J.; Schmidt, D.; Hirtz, G.; Stollmann, P.; Voelcker-Rehage, C. Sensor-Based Systems for Early Detection of Dementia (SENDA): A Study Protocol for a Prospective Cohort Sequential Study. BMC Neurology 2020, 20. [CrossRef]

- Jonell, P.; Moëll, B.; Håkansson, K.; Henter, G.E.; Kuchurenko, T.; Mikheeva, O.; Hagman, G.; Holleman, J.; Kivipelto, M.; Kjellström, H.; et al. Multimodal Capture of Patient Behaviour for Improved Detection of Early Dementia: Clinical Feasibility and Preliminary Results. Frontiers in Computer Science 2021, 3. [CrossRef]

- Yurdem, B.; Kuzlu, M.; Gullu, M.K.; Catak, F.O.; Tabassum, M. Federated Learning: Overview, Strategies, Applications, Tools and Future Directions. Heliyon 2024, 10.

- Li, H.; Li, C.; Wang, J.; Yang, A.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Hua, D. Review on Security of Federated Learning and Its Application in Healthcare. Future Generation Computer Systems 2023, 144, 271–290. [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.M. Federated Learning Models for Privacy-Preserving Ai in Enterprise Decision Systems. International Journal of Business and Economics Insights 2025, 05, 238–269. [CrossRef]

- Addae, S.; Kim, J.; Smith, A.; Rajana, P.; Kang, M. Smart Solutions for Detecting, Predicting, Monitoring, and Managing Dementia in the Elderly: A Survey. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 100026–100056. [CrossRef]

- Thaliath, A.; Pillai, J.A. Non-Cognitive Symptoms in Alzheimer’s Disease and Their Likely Impact on Patient Outcomes. A Scoping Review. Current Treatment Options in Neurology 2025, 27.

- Ghayvat, H.; Gope, P. Smart Aging Monitoring and Early Dementia Recognition (SAMEDR): Uncovering the Hidden Wellness Parameter for Preventive Well-Being Monitoring to Categorize Cognitive Impairment and Dementia in Community-Dwelling Elderly Subjects through AI. Neural Computing and Applications 2023, 35, 23739–23751.

- Deters, J. K.; Janus, S.; Silva, J.A.L.; Wörtche, H.J.; Zuidema, S.U. Sensor-Based Agitation Prediction in Institutionalized People with Dementia A Systematic Review. Pervasive and Mobile Computing 2024, 98.

- Anikwe, C. V.; Friday Nweke, H.; Chukwu Ikegwu, A.; Adolphus Egwuonwu, C.; Uchenna Onu, F.; Rita Alo, U.; Wah Teh, Y. Mobile and Wearable Sensors for Data-Driven Health Monitoring System: State-of-the-Art and Future Prospect. Expert Systems with Applications 2022, 202.

- Gabrielli, D.; Prenkaj, B.; Velardi, P.; Faralli, S. AI on the Pulse: Real-Time Health Anomaly Detection with Wearable and Ambient Intelligence. In Proceedings of the CIKM 2025 - Proceedings of the 34th ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management; 2025; pp. 4717–4721.

- Assaad, R.H.; Mohammadi, M.; Poudel, O. Developing an Intelligent IoT-Enabled Wearable Multimodal Biosensing Device and Cloud-Based Digital Dashboard for Real-Time and Comprehensive Health, Physiological, Emotional, and Cognitive Monitoring Using Multi-Sensor Fusion Technologies. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical 2025, 381. [CrossRef]

- Teoh, J.R.; Dong, J.; Zuo, X.; Lai, K.W.; Hasikin, K.; Wu, X. Advancing Healthcare through Multimodal Data Fusion: A Comprehensive Review of Techniques and Applications. PeerJ Computer Science 2024, 10.

- Johnson, B.B. Noninvasive Patient Monitoring With Ambient Sensors To Monitor Physical and Cognitive Health for Individuals Living With Alzheimer’S Disease. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 Design of Medical Devices Conference, DMD 2024; 2024.

- Bijlani, N.; Maldonado, O.M.; Nilforooshan, R.; Barnaghi, P.; Kouchaki, S. Utilizing Graph Neural Networks for Adverse Health Detection and Personalized Decision Making in Sensor-Based Remote Monitoring for Dementia Care. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2024, 183. [CrossRef]

- Obeidat, H.; Shuaieb, W.; Obeidat, O.; Abd-Alhameed, R. A Review of Indoor Localization Techniques and Wireless Technologies. Wireless Personal Communications 2021, 119, 289–327.

- Leitch, S.G.; Ahmed, Q.Z.; Abbas, W. Bin; Hafeez, M.; Laziridis, P.I.; Sureephong, P.; Alade, T. On Indoor Localization Using WiFi, BLE, UWB, and IMU Technologies. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland) 2023, 23. [CrossRef]

- Casha, O. A Comparative Analysis and Review of Indoor Positioning Systems and Technologies. In Innovations in Indoor Positioning Systems (IPS); 2024.

- Biehl, J.T.; Girgensohn, A.; Patel, M. Achieving Accurate Room-Level Indoor Location Estimation with Emerging IoT Networks. In Proceedings of the ACM International Conference Proceeding Series; 2019.

- García-Paterna, P.J.; Martínez-Sala, A.S.; Sánchez-Aarnoutse, J.C. Empirical Study of a Room-Level Localization System Based on Bluetooth Low Energy Beacons. Sensors 2021, 21. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y. A Room-Level Indoor Localization Using an Energy-Harvesting BLE Tag. Electronics (Switzerland) 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Karabey Aksakalli, I.; Bayındır, L. Enhancing Indoor Localization with Room-to-Room Transition Time: A Multi-Dataset Study. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2025, 15. [CrossRef]

- Tegou, T.; Kalamaras, I.; Votis, K.; Tzovaras, D. A Low-Cost Room-Level Indoor Localization System with Easy Setup for Medical Applications. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2018 11th IFIP Wireless and Mobile Networking Conference, WMNC 2018; 2018.

- Alzu’Bi, A.; Alomar, A.; Alkhaza’Leh, S.; Abuarqoub, A.; Hammoudeh, M. A Review of Privacy and Security of Edge Computing in Smart Healthcare Systems: Issues, Challenges, and Research Directions. Tsinghua Science and Technology 2024, 29, 1152–1180. [CrossRef]

- Islam, U.; Alatawi, M.N.; Alqazzaz, A.; Alamro, S.; Shah, B.; Moreira, F. A Hybrid Fog-Edge Computing Architecture for Real-Time Health Monitoring in IoMT Systems with Optimized Latency and Threat Resilience. Scientific Reports 2025, 15. [CrossRef]

- Rancea, A.; Anghel, I.; Cioara, T. Edge Computing in Healthcare: Innovations, Opportunities, and Challenges. Future Internet 2024, 16.

- Ali, M. S., Ahsan, M. M., Tasnim, L., Afrin, S., Biswas, K., Hossain, M. M., ... & Raman, S. Federated Learning in Healthcare: Model Misconducts, Security, Challenges, Applications, and Future Research Directions--A Systematic Review. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.13832 2024.

- Pati, S.; Kumar, S.; Varma, A.; Edwards, B.; Lu, C.; Qu, L.; Wang, J.J.; Lakshminarayanan, A.; Wang, S. han; Sheller, M.J.; et al. Privacy Preservation for Federated Learning in Health Care. Patterns 2024, 5.

- Dhade, P.; Shirke, P. Federated Learning for Healthcare: A Comprehensive Review. Engineering Proceedings 2023, 59. [CrossRef]

- Lyons, B.E.; Austin, D.; Seelye, A.; Petersen, J.; Yeargers, J.; Riley, T.; Sharma, N.; Mattek, N.; Wild, K.; Dodge, H.; et al. Pervasive Computing Technologies to Continuously Assess Alzheimer’s Disease Progression and Intervention Efficacy. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 2015, 7. [CrossRef]

- Gothard, S.; Nunnerley, M.; Rodrigues, N.; Wu, C.Y.; Mattek, N.; Hughes, A.M.; Kaye, J.A.; Beattie, Z. Study Participant Self-Installed Deployment of a Home-Based Digital Assessment Platform for Dementia Research. Alzheimer’s & dementia: the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association 2021, 17, e055724. [CrossRef]

- Narasimhan, R.; Gopalan, M.; Sikkandar, M.Y.; Alassaf, A.; AlMohimeed, I.; Alhussaini, K.; Aleid, A.; Sheik, S.B. Employing Deep-Learning Approach for the Early Detection of Mild Cognitive Impairment Transitions through the Analysis of Digital Biomarkers. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland) 2023, 23. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Cheon, S.; Lim, J. IoT-Based Unobtrusive Physical Activity Monitoring System for Predicting Dementia. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 26078–26089. [CrossRef]

- Beutel, D.J.; Topal, T.; Mathur, A.; Qiu, X.; Fernandez-Marques, J.; Gao, Y.; Sani, L.; Li, K.H.; Parcollet, T.; de Gusmão, P.P.B.; et al. Flower: A Friendly Federated Learning Research Framework. arXiv preprint arXiv:2007.14390 2022.

| System | Localization | Monitoring Type | Edge ML | Fed. Learning | Clinical Validation | Est. Cost | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORCATECH [37,38] | Zone-level (PIR) | Passive + episodic digital | No | No | Extensive (10+ years) | Hight | Zone-level localization insufficient for disorientation |

| SENDA [8] | None | Active (periodic testing) | No | No | Ongoing protocol | Hight | Requires active participation; episodic (8-month) |

| Kim et al. [40] | Zone-level (PIR) | Passive IR only | No | No | Limited (AUC 0.99) | Medium | No wearables; zone-level only |

| Ghayvat & Gope [15] | None | Passive sensors + transfer learning | No | No | Real-world (43 weeks) | Medium | No spatial tracking |

| Bijlani et al. [22] | Ambient only | Passive graph-based | Yes | No | Real deployment (227 participant) | Medium | No wearables; no room-level |

| This work | Room-level (IR) | Passive 24/7 | Yes (ESP32-S3) | Yes (simulated) | Technical only | 490€ + 55€/month | No clinical validation yet |

| Stage | Format | Frequency | Size | Retention | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BLE packets (raw) | Manufacturer-specific binary | 2 Hz (telemetry), 1 Hz (location) | 20-30 bytes/packet | Transient | - |

| Stream 1 | JSON (aggregates) | 1/minute | 1.8-2.2 KB | Transient | Statistical descriptors |

| Stream 2 | JSON + gzip | 1/ minute | 1.3-1.7 KB (compressed) | Transient | Compressed event sequences |

| Stream 3 | JSON (alerts) | On-demand (~10/day) | 0.4-0.6 KB | Transient | Critical events |

| InfluxDB (hot data) | Line Protocol | 1 record/ minute | 200-300 bytes | 7 days | Real-time dashboards |

| MongoDB (event logs) | BSON (gzip blob) | 1 doc/ minute | 1.5-2 KB | 90 days | ML |

| MongoDB (critical alerts) | BSON | On-demand (~10/day) | 0.5-0.8 KB | Unlimited period | Audit trail |

| MongoDB (hourly aggregates) | BSON | 1 doc/hour | 2.5-3 KB | 90 days | Fast ML |

| MongoDB (daily summaries) | BSON | 1 doc/day | 2-3 KB | Unlimited period | Baseline models, reports |

| Distance | Condition | Average RSSI (dBm) | σ (dBm) | Attenuation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 m | Reference | -69 | 2 | - |

| 5 m | Line-of-sight | -70 | 3 | ~1 dB |

| 5 m | One wall | -76 | 4-5 | 6-8 dB |

| 5 m | One wall | -76 | 4-5 | 6-8 dB |

| 15 m | One wall | -91 | 7 | ~22 dB |

| Stream | Compression | Size | Reduction | Temporal Resolution | Lossless |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (raw BLE) | None | 5,160 B | - | 1 s | yes |

| Stream 1 (aggregates) | Statistical | 2,000 B | 61.2% | 60 s | no |

| Stream 3 (aggregates) | Diff + gzip | 1,036 B | 79.9% | 1 s | yes |

| Stream 1 (alarms) | Contextual enrichment | 500 B | On-demand | Event | yes |

| Combined (Stream1+Stream2) | Hybrid | 3,036 B | 41.2% | Hybrid | Partial |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).