1. Introduction

In real-world edge deployment scenarios, drones continuously collect data highly relevant to mission execution, including flight status information, onboard perception images, and multi-source telemetry data [

1,

2,

3]. This type of data typically contains sensitive operational details and restricted environmental characteristics, making it difficult to centrally aggregate under multiple constraints such as privacy protection, security control, and regulatory compliance [

4,

5]. This weakens the feasibility of traditional centralized model training paradigms in drone applications. Meanwhile, this mission data is crucial for improving drones’ capabilities in autonomous flight, path planning, and intelligent decision-making, but it is often scattered across different fleets, operating entities, and deployment areas [

6,

7]. This means that the data held by a single node is insufficient in terms of scale and diversity to meet the demands of high-capacity model training [

8,

9,

10,

11].

FL provides a distributed training mechanism for collaborative modeling in UAV scenarios, eliminating the need for centralized raw data [

12,

13,

14,

15]. This allows UAVs or edge nodes to participate in collaborative model updates while maintaining the privacy of their local data. In this mechanism, each node independently trains its model based on its own onboard data and submits only the updated results to the coordinating node for aggregation. Through multiple rounds of interaction, a shared global model is gradually formed. This allows the model to integrate knowledge from different fleets and mission scenarios without compromising data sovereignty and privacy boundaries [

16,

17]. This provides a feasible foundation for UAV collaborative intelligence under privacy-constrained conditions and supports the adaptation of large-scale and multimodal models at the edge [

18,

19].

While federated learning offers new possibilities for collaborative modeling in UAV scenarios, it still faces significant security and reliability challenges under Arm-based embedded edge platforms and intermittent air-to-ground links [

20]. Model updates during sharing may leak mission-sensitive information such as flight trajectories or scene features, and are susceptible to injection of forged updates by abnormal or malicious nodes, thereby disrupting the aggregation process and weakening model convergence performance [

21,

22,

23]. These risks are further amplified in UAV scenarios: the instability of air-to-ground communication limits high-frequency security verification; the limited computing power and energy consumption budget of edge nodes makes it difficult to deploy complex protection mechanisms; and the heterogeneity of equipment brought about by cross-fleet collaboration places higher demands on the credibility and integrity of update sources. Therefore, ensuring mission data privacy, verifying model update protection, and maintaining system efficiency under resource constraints are critical challenges for UAV federated learning [

24].

To address the aforementioned issues, this paper proposes a secure and verifiable federated learning framework for UAV scenarios. This framework introduces homomorphic encryption during model update generation, transmission, and aggregation to prevent gradient or adapter parameter leaks of sensitive task information. Furthermore, it ensures the isolation and integrity of aggregation computation by deploying a remotely authenticated TEE on the server side. Simultaneously, an aggregation signature mechanism enables efficient verification of the identities and update consistency of participating nodes, and by packaging and sparsifying model updates, communication and energy consumption overhead are further reduced.

The proposed solution contributes as follows:

We propose a secure and verifiable edge federated learning framework for UAV scenarios. The framework mitigates gradient inversion and membership inference risks caused by plaintext exposure in existing HE-based schemes. Device-side updates are protected with homomorphic encryption, and server-side decryption and aggregation are confined to a remotely attested Trusted Execution Environment. Plaintext access to model updates is restricted at the server side.

We introduce an aggregate-signature-based verification mechanism for federated aggregation. The mechanism addresses the lack of source authentication and update integrity in existing HE-based federated learning schemes. Participant identity and update integrity are enforced before aggregation. Malicious or tampered updates are prevented from entering the aggregation process.

We evaluate the proposed framework through extensive experimental simulations. The results show an approximately 3% improvement in model accuracy over comparative schemes. Computational overhead is reduced by about 20%. Stable convergence is maintained under packet loss and device heterogeneity.

2. Related Work

Privacy-preserving FL at the edge typically adopts differential privacy (DP), secure multi-party computation (MPC), or HE to protect updates while keeping raw data local on UAVs or edge devices [

25,

26,

27,

28]. Among these, HE is especially appealing for embedded edge deployments because it supports computation directly over encrypted updates and aligns with strict airspace and mission-data regulations [

29]. Meanwhile, shared model updates (gradients or weights) can still leak operational details such as flight trajectories, target features, or environmental imagery if left unprotected.

For UAV collaborative training, several HE-based schemes inform design choices under edge constraints. Zhang et al. [

30,

31] proposed BatchCrypt, combining gradient quantization with batch encoding to reduce computation and bandwidth without sacrificing accuracy—techniques well suited to bandwidth-limited UAV swarms. Li et al. [

32] presented an IoT-oriented FL framework with a threshold Paillier cryptosystem, whose resilience to untrusted participants extends to cross-fleet UAV operations. He et al. [

33] optimized Paillier and aggregation at the edge to lower latency, a key requirement for time-sensitive aerial missions with intermittent air-ground links and tight energy budgets.

Privacy-preserving mechanisms based on cryptographic gradients have been extensively studied in the field of distributed artificial intelligence and have provided important references for embedded edge applications. Zhang et al. [

34] combined masking with HE to construct an end-to-end privacy-preserving IoT training process, suitable for UAV-Ground collaborative scenarios; Wang et al. [

35] proposed PPFLHE, which combines HE with trust assessment to support dynamic access control during the aggregation process, which is particularly important for multi-fleet and multi-operator collaboration; Firdaus et al. [

36] introduced blockchain to achieve decentralized federated learning, enhancing the auditability and multi-party collaboration capabilities of the system; Mantey et al.’s research shows that cryptographic gradients can still effectively improve model performance in recommendation tasks [

37], further confirming the feasibility of HE in utility-preserving privacy protection.

In summary, existing research still has three key shortcomings in UAV FL: first, model updates may still leak mission-sensitive information such as flight trajectories and scene features during the sharing process, making it difficult to guarantee privacy protection under edge conditions. Second, traditional federated learning lacks credible assumptions to support the server aggregation process, and the aggregation computation is susceptible to tampering or inconsistent execution, making it difficult to provide continuous verifiability across rounds. Third, in collaborative training environments involving multiple fleets and cross-operating entities, the identities of participating nodes are complex and dynamically changing, making it difficult to efficiently verify the credibility of the model update source and the consistency of global model distribution under limited computing power, bandwidth, and energy consumption conditions. To address the aforementioned issues, this paper constructs a secure and verifiable federated learning framework for UAV scenarios. On the device side, a homomorphic encryption mechanism is introduced to encrypt local gradients or LoRA updates throughout the process, preventing model updates from leaking sensitive task information. Packaging and sparsity techniques are combined to reduce encrypted communication and energy consumption. On the server side, aggregation computation is deployed in a remotely authenticated trusted execution environment, ensuring the aggregation process executes correctly according to the protocol through hardware isolation and integrity verification. Simultaneously, an aggregation signature mechanism is introduced to perform batch verification of the integrity proof of model updates, achieving authentication of participating nodes, binding of update sources, and cross-user model consistency verification. Through this collaborative design, the framework achieves a balance between privacy protection, verifiable aggregation, and stable convergence under constrained edge conditions, providing a deployable solution for multi-fleet collaborative training of UAVs and large-scale model adaptation at the edge.

3. Preliminary

3.1. Homomorphic Encryption

HE systems are usually composed of key generation algorithms, encryption algorithms, decryption algorithms, and algorithmic rules. Among them, the key generation algorithm is used to generate a public key for encryption and a private key for decryption; the encryption algorithm and decryption are used to transform plaintext data and ciphertext. The operational rules define which operations can be performed on ciphertext to ensure a homomorphic property. This property guarantees that the result of the ciphertext operation corresponds to the result of the plaintext operation. The definition of a homomorphism is as follows:

Definition 1: In HE’s arithmetic rules, homomorphisms generally include additive homomorphisms and multiplicative homomorphisms:

For additive HE: If the encryption function

corresponds to the addition operation. For any plaintext

and

, encrypted ciphertexts

and

satisfy:

where, ⨁ is the addition operation of the ciphertext.

For multiplicative HE: If the encryption function

corresponds to a multiplication operation, for any plaintext

and

, encrypted ciphertexts

and

satisfy:

Currently, HE technology has become a commonly used technology in privacy-preserving computing, encrypted computing, cloud computing, etc., providing strong security for related fields.

3.2. Trusted Execution Environment

TEE provides a secure, isolated operating environment to protect sensitive data and code from malware and unauthorized access [

38]. Its core goal is to create a hardware or software-isolated space where programs can run independently from the OS and regular applications, ensuring data confidentiality and integrity. TEE typically includes a trusted execution area, such as Intel SGX’s Enclave, separate from the Rich Execution Environment(REE). This isolation offers higher security than conventional OS, safeguarding user data and processes. TEE also consists of the TEE Application, which handles sensitive tasks like encryption, and the TEE Manager, which manages the environment, applications, and resources, providing an interface to the outside world. Key features of TEE are outlined in [

39].

(1) Isolation: TEE realizes physical isolation of sensitive information through a combination of hardware and software. Even if the operating system or application program is attacked, the sensitive data can still remain safe.

(2) Protection of data confidentiality and integrity: TEE prevents data leakage or tampering during transmission and storage. It uses encryption, digital signatures, and other means to ensure data integrity.

(3) Support for Trusted Computing: TEE provides trusted computing services for applications. It ensures that the computational process remains free from external interference and guarantees the credibility of the results.

(4) Hardware acceleration: TEE usually relies on the security features provided by hardware (ARM’s TrustZone, Intel’s SGX, etc.), and is therefore more powerful than pure software security measures.

These benefits have led to a wide range of applications for TEE, especially in the areas of mobile devices, payment security, cloud computing, and the Internet of Things.

3.3. Schnorr Aggregated Signature

Schnorr Aggregate Signature is an extension of the Schnorr signature algorithm, designed to enhance the efficiency of processing multiple signatures, especially in scenarios with multiple participants signing the same message. It combines multiple independent Schnorr signatures into a single “aggregated signature,” allowing the verifier to check just one combined signature, greatly improving verification efficiency. The key mechanism involves using aggregated challenge values to merge data from multiple signatures, enabling the entire set to be verified in a single step. The flow of a Schnorr aggregate signature is as follows:

(1) Individual Signature Generation

For each signer , Suppose its private key is , The public key is , the signer generates the signature using a similar approach to the Schnorr signature : selects a random number , and calculates , , , Then send to the server.

(2) Aggregate Signature Generation

The server calculates the sum of the challenge values for all signers , Weighted sum of all signatures and the sum of the common points of all signers , and get the aggregated signature , subsequently send the aggregated signature to the verifier.

(3) Aggregate Signature Verification

For verification, the verifier needs to verify only one aggregated signature, not each individual signature. The verification process is similar to the verification of individual Schnorr signatures, but requires the use of the aggregated common point and the aggregated challenge value to compute the , and calculate the sum of the public keys of all signers . Finally, verify whether the equation holds, if so, the verification passes.

4. Secure and Verifiable Edge-Federated Learning for UAV Applications with HE and TEE

The trusted federated learning framework proposed in this chapter targets UAV-based LLM adaptation and edge applications. It encrypts on-device gradients, or LoRA updates with HE, and applies packing and sparsification to reduce payload and bandwidth. Server aggregation executes inside a remotely attested TEE, providing hardware-rooted isolation and integrity, while aggregate signatures authenticate participants and bind updates to their sources for low-overhead, end-to-end verifiability across rounds. Together, these mechanisms safeguard mission data confidentiality and preserve global model integrity in cross-fleet collaborative training over intermittent air-to-ground links on heterogeneous Arm-based devices.

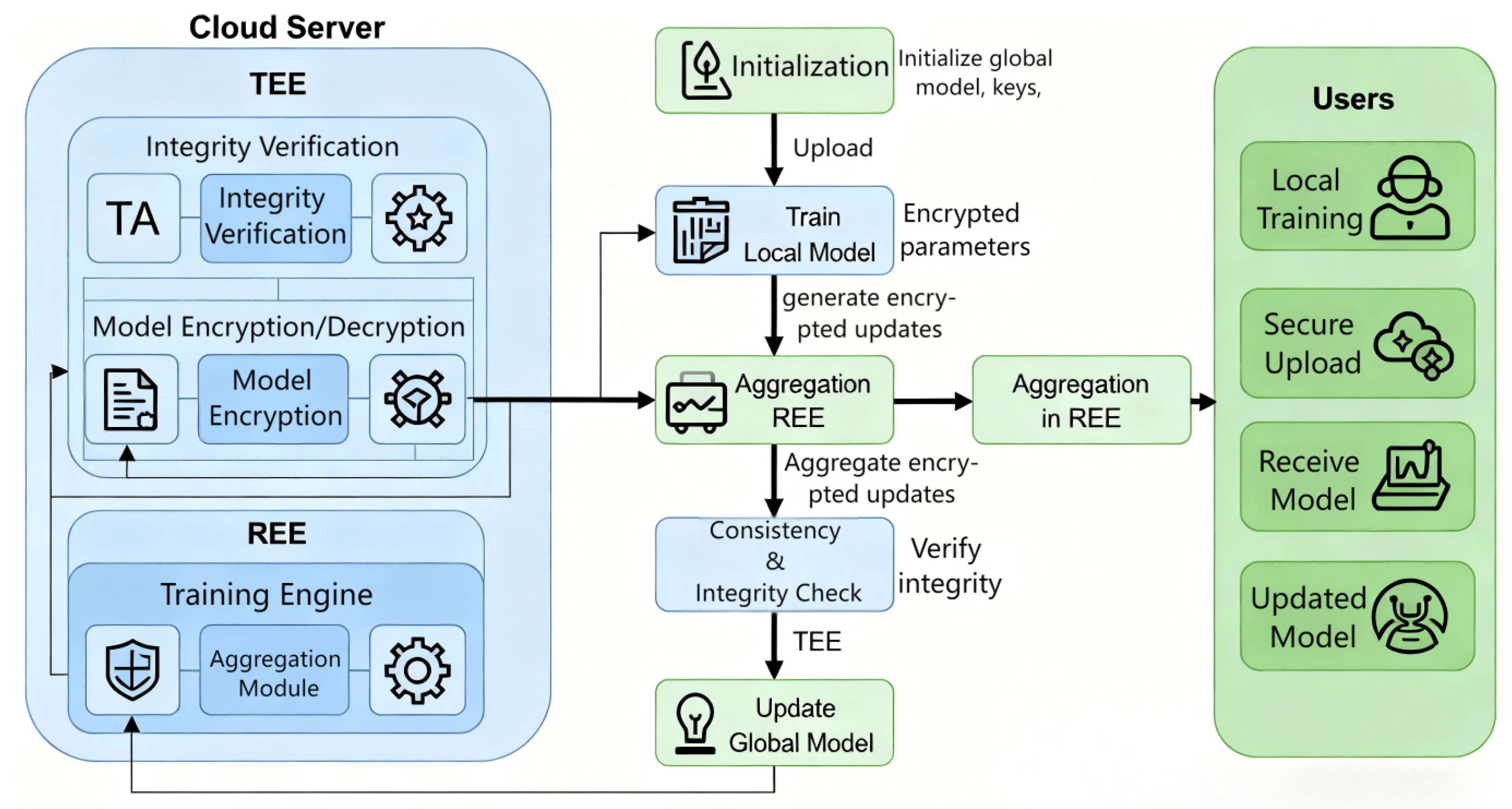

4.1. System Model

This study introduces a trusted computing framework for federated learning in UAV scenarios. The framework combines homomorphic encryption and an optimized aggregate signature mechanism, delivering dual-layer security for distributed training. The scheme uses the CKKS algorithm for local model parameters and generates integrity proofs of model parameter ciphertexts with aggregated signatures. As shown in

Figure 1, the scheme involves two participant entities: users and the cloud server.

User: In federated learning, users own the local task data, typically represented by drones participating in the collaborative training. Each drone uses the task data it collects onboard to train its local model and uploads the updated local model results to a cloud server to complete the federated learning process. To ensure the privacy and security of the onboard task data, users encrypt the local model parameters using HE technology. Furthermore, to prevent the local model parameters from being tampered with or corrupted during transmission via the air-to-ground link, users also generate an integrity certificate for the encrypted model parameters. This certificate, built using digital signature technology, is sent to the server along with the encrypted parameters for subsequent integrity and legitimacy verification.

Cloud servers: The cloud server is responsible for executing the federated learning process and providing aggregation and verification services to participating nodes. Internally, the server is divided into TEE and REE, where the TEE offers an isolated and trusted computing space, while the remaining system resources operate in the REE. In the proposed framework, a Trusted Application (TA) is deployed within the TEE to perform integrity and consistency verification of model parameters. In addition, the TA plays a central role in secure identity management: the user identifier (ID) is not a public label but is securely negotiated between the TA and each user through a confidential channel during system initialization and is known only to these two parties. The negotiated ID is cryptographically bound to protocol requests and responses via digital signatures, enabling the TA to verify message authenticity and integrity. To prevent replay attacks, nonces and timestamps are incorporated into the signed messages, ensuring freshness and uniqueness. During protocol execution, the TA can perform individual or aggregated verification based on ID-bound signature keys without explicitly revealing user identities, thereby supporting multi-party verification while preserving user privacy.

Although HE introduces non-negligible cryptographic overhead, our design carefully confines its usage to on-device model updates and avoids repeated key generation and expensive ciphertext operations on UAV platforms. The key pairs are generated once during system initialization and reused across training rounds, thereby amortizing the associated cost over long-running federated learning processes. In addition, lightweight update representations are employed to significantly reduce encrypted payload sizes, effectively mitigating both computation and communication overhead on resource-constrained Arm-based edge devices. To further balance security and efficiency, the proposed framework deliberately minimizes the trusted computing base (TCB) by avoiding the execution of all cryptographic operations inside the TEE. Specifically, only aggregation and integrity verification are performed within the TEE, while encryption, communication, and other non-sensitive operations remain in the REE. This selective deployment substantially reduces enclave entry and exit frequency, alleviates trusted–untrusted context-switching overhead, and ensures that strong security guarantees are achieved with minimal performance degradation.

4.2. Security Aggregation and Authentication Mechanism

4.2.1. System Initialization

First, the TA deployed in the TEE selects a common point G, the Collision Resistant Hash Function (CRHF) , and shares , G and with all Federated Learning users. Thus, the server and all federated learning users use the same parameters for generating and verifying integrity proofs.

TA selects its private key , Calculate the corresponding public key , and select a random integer x. Subsequently, the TA generates detection requests for each of the N federated learning users . Detecting a request is a tuple of three elements, , where is the identity of the federated learning user .

After consultation among all participants, it was agreed to encrypt the user’s local model parameters using the HE function to generate the public and private keys required to perform HE. Subsequently, the server generates the initial global model parameter and distributes it to each user together with .

4.2.2. Local Model Training and Parameter Upload

For users in the Federal Learning System, After receiving the initial global model parameter from the server, it will be loaded into the local model and trained. When is satisfied with the trained model, it will first encrypt its own local model parameter using to obtain the ciphertext of the local model parameter. Subsequently, generates an integrity proof for

For , it chooses a private key and a corresponding public key . After receiving the request , first checks if the is correct, and then generates the response . This phase consists of four basic steps.

User checks the correctness of by checking if the user identification () in is correct. If it is correct, the is considered valid, otherwise the is discarded. in a subsequent step, the integrity proof is generated using and .

The user chooses a random integer and obtains . Note that and are time-sensitive values that will only be used once.

User

generates the signature of the ciphertext

of the local model parameters, denoted as

, which serves as the integrity proof of

.

The user generates the response and sends it back to the TA in response to the TA’s check request. The response is a tuple containing three elements, , and also sends to the server.

4.2.3. Local Model Parameter Integrity Validation

In existing HE-based privacy-preserving federated learning schemes, the system directly aggregates and decrypts the encrypted parameters uploaded by participants. However, these parameters may be corrupted during transmission. In our scheme, the system first verifies the integrity of the uploaded parameters, using only those that pass verification for model aggregation. This approach enhances the trustworthiness of the federated learning system.

To ensure the authenticity of parameters in the aggregation process, the integrity of the local model parameter ciphertexts uploaded by users must be verified. Verifying each ciphertext individually would incur significant computational overhead. Therefore, the TA uses an aggregation verification method, combining all integrity proofs (user signatures) into a single aggregated signature. This allows the TA to verify the integrity of the received ciphertexts by checking only the aggregated signature. Specifically, given a set of response collections and local model parameter ciphers , the system follows these steps to complete the aggregation verification process.

The REE initiates a parameter integrity verification request to the TA and sends its own received to the TA.

TA aggregates the signatures and R of each user in the response set RES to obtain .

-

TA perform the following calculations and determine if the equation holds true.

If Equation (

4) holds, the ciphertexts received by the server for all users’ local model parameters are complete, and the TA sends the message

to the REE, which receives and acknowledges it and performs the ciphertext aggregation computation to obtain the aggregated ciphertext

.

-

If the calculation yields that Equation (

4) does not hold, the TA starts a lookup of the corrupted local model parameters. Depending on the size of

N, this scheme provides two methods of lookup.

Sequential lookup: If

N is small, the TA can verify each element in

individually, one by one, to verify the integrity of

to compute

If Equation (

5) above holds, the integrity of

can be determined. However, as mentioned earlier, the individual-by-individual verification approach results in a high computational overhead when

N is large. Instead, it is obvious that aggregate verification can be performed on any corresponding subset of the response set

and the ciphertext set

C. This allows the TA to divide a set of integrity proofs into multiple subsets for aggregate verification.

Bisection Lookup: When the number of users N is large, the idea of bisection lookup can be borrowed to iteratively split the response set into two subsets on average, and verify the aggregation of these subsets. The specific process includes the following basic steps:

Given a response set

and a ciphertext set

C, first check if Equation (

4) holds. If it holds, it indicates that there is no data corruption in

C and the localization process ends. If Equation (

4) does not hold and

, then the only copy of data currently in

C is corrupted.

If

and Equation (

4) still does not hold, it indicates that C contains multiple model parameter ciphers, at least one of which is corrupted. At this point,

C and

are partitioned into two corresponding subsets, denoted as

,

,

and

.

Repeat steps 5 and 6 for and , respectively, until all corrupted model parameter ciphertexts have been successfully localized.

Through the binary lookup process, all corrupted model parameter ciphertexts can be efficiently identified in a larger response set. Once the corrupted parameters are located, the TA removes them from the ciphertext set and returns the updated set to the for normal ciphertext aggregation, yielding the result . As shown in Section 3.3.3, the aggregation decryption result remains unaffected after removing the corrupted ciphertexts.

4.2.4. Global Model Parameter Consistency Check

After the obtains the ciphertext aggregation result , it sends to the TEE for partial decryption. The partial decryption result is then used for aggregation decryption to obtain the new global model parameter W, which is sent to each user. To protect user rights, the TA verifies the consistency of the global model parameters received by all users. To prevent the REE from sending incorrect parameters to specific users, a consistency verification mechanism is introduced. This mechanism checks whether any two users receive identical global model parameters, ensuring fair distribution across all participants.

TA sends a detection request to , where is the identity of the new global model parameter W.

After confirming that the received reqREE is valid, the selects its private key and the corresponding public key . and selects a random integer to obtain .

-

generates an integrity proof of

W, denoted as

, which is used to perform a consistency check of the global model parameters, where

-

After user

receives the

from REE, it first performs the integrity proof of

W, and calculates

= If Equation (

7) holds,

determines that its received

W is complete and subsequently sends

to the TA for consistency verification.

Let the signatures received by the TA from any two different users and be and . Since the global model parameters obtained by users and are the same in the normal case, it is certain that the users receive the same global model parameters if .

5. Security Analysis

Our scheme ensures the trustworthiness of the federated learning process by means of an integrity verification method for model parameters based on aggregated signatures. This section will focus on the in-depth analysis of the security of this integrity verification method.

5.1. Correctness

5.1.1. Individual Verification of Method Correctness

In

Section 4, Equations (5) and (7) use the separate verification method. This section uses Equation (

5) as an example for the correctness analysis of the separate verification method. In Equation (

5),

is the signature generated by the federated learning system user

using his private key and the local model parameter ciphertext

via Equation (

3). Thus,

is the basis for integrity verification. If the model cipher parameters received by the server are not corrupted, then the following should hold:

From Equation (

8), it can be shown that the separate verification methods in the program are effective.

5.1.2. Aggregate Validation Method Correctness

The aggregated verification method is used in Equation (

4) in Section 4.3, given the set of responses

and the set of ciphertexts

C of size

N and the sum of the signatures of all the users

. If all the ciphertexts of the model parameters received by the server are complete, then there is a proof similar to that of the separate verification method:

The aggregated verification method is used in Equation (

4) in Section 4.3, given the set of responses

and the set of ciphertexts

C of size

N and the sum of the signatures of all the users

. If all the ciphertexts of the model parameters received by the server are complete, then there is a proof similar to that of the separate verification method:

From Eqs. 9, it can be demonstrated that the aggregation verification method in the scheme is effective.

5.2. Anti-Forgery Attacks

Theorem 1: In the case where the cryptographic hash function is a collision-resistant hash function, and the ECDLP complexity assumptions hold, ciphertext data of model parameters or ciphertext data integrity proofs forged by an external attacker cannot be verified by a non-negligible margin.

Prove: The proof of the theorem needs to consider the following two scenarios: 1) Attacker intercepts the ciphertext of the model parameters of user , generates a forged ciphertext and sends it to the server, and 2) Attacker intercepts and checks the proof of validity of , which generates a forged proof of data integrity .

Scenario 1: In this case,

obtains the forged ciphertext data

by corrupting

, or by generating it by itself and sends it to the server, and according to Equation (

5), the necessary condition for

to be able to pass the authentication at TA is:

holds, but since

, then if Eqs. 10 hold, it implies that

produces the same hash value for two different inputs, which conflicts with the fact that

is collision resistant.

-

Scenario 2: In this case,

chooses and generates its own public-private key pair

and

.

then intercepts a valid proof

for user

and forges an integrity proof for

based on

.

According to Equations (3) and (5), if we want the forged

to pass the verification of TA, we need to make

, which is because the hash function

is a one-way function that contains

,and thus it is impossible to change the hash value or R_k in Equation (

3). In orden to forge the integrity proof

must know s

and

However, as mentioned earlier, s

and

are held separately and undisclosed by

, and the attacker

can only obtain the corresponding public keys

and

Nevertheless, if

has a non-negligible advantage in obtaining

and

through

and

,respectively, this will violate the ECDLP complexity assumption. In summary, our scheme guarantees security against forgery attacks.

5.3. Anti-Collusion Attack

The aggregation algorithm of the verification scheme has to be reliable against collusion attacks. According to Theorem 4.1, if a single user-generated integrity proof is proved to be unforgeable under the ECDLP difficulty assumption, the individual verification methods in the scheme are reliable, and this section proves the reliability of the aggregated verification methods in the scheme.

Theorem 2: Assuming that is a collision-resistant hash function, given the aggregation verification algorithm of our scheme, an aggregation integrity proof generated by a set containing at least one invalid integrity proof is also invalid.

Prove: Assuming that is an adversary that can launch a collusion attack, construct a simulator to respond to ’s query, and the interaction between and is as follows.

(1) Initialization phase: given a common point G on an elliptic curve ec, and an anti-collision hash function , B simulates the initialization algorithm of TA to generate public-private key pairs , and chooses a random integer x. Subsequently, B generates a request set , and sends to .

(2) Query stage: Given the above public parameters, performs the following operations:

Key query. B receives such a query from A on user and runs a key generation algorithm to generate a key pair and returns it to A.

Forgery. forges an individual integrity proof for a set of users after using the received keys of each user , which is signed in the ciphertext set under the ciphertext set . Subsequently A generates the forged aggregation integrity proofs and .

Aggregation Verification Query. generates a response set using the key pairs received from each user, and sends the RES together with the ciphertext set C to for an aggregate verification query. receives the response and simulates the aggregate verification algorithm to determine whether is valid. then returns the validation result to .

can win the game if the following requirements are met.

1)

is a valid proof of aggregation integrity, which means that

2) At least one user’s individual integrity proof

fails to pass the verification algorithm, at least one honest user

does not collude with

. Then

is the only honest user and

denotes the forged invalid individual integrity proof. Then, if

is valid, it means

From Equation (

14), we have

, so Equation (

12) clearly does not hold, or else it would conflict with the collision resistance of

. Therefore, the only way that the aggregation verification method of our scheme is guaranteed to generate valid aggregation integrity proofs is to feed all valid individual integrity proofs into the aggregation algorithm. In summary, our scheme guarantees security in the face of collusion attacks.

6. Experiments And Analysis

6.1. Efficiency Analysis

This section analyzes the computational overhead of the proposed scheme to evaluate its efficiency. It focuses on the initialization, parameter uploading, integrity verification, and consistency checking phases, specifically examining the overhead of point addition, point multiplication, and hash operations on the elliptic curve

. Algebraic addition and multiplication overheads are not included, as they are negligible compared to the point and hash operations. The analysis results, assuming

n model parameter ciphertexts, are shown in

Table 1.

Table 1 shows that our scheme does not impose excessive computational overhead on the federated learning server or the user. In the parameter upload phase, the operation of generating integrity proofs for the model parameter ciphertexts by the user imposes the main computational overhead in this phase. Each user performs only one hash operation, one dot-addition, and two dot-multiplications, which guarantees the efficiency of this scheme on the user side.

In the integrity verification phase, this scheme uses the aggregation verification method to check n model parameter ciphertexts with only dot multiplications. Compared with individual verification, it replaces nearly half of the dot multiplications with the less costly dot additions, thus reducing computation. As a result, the aggregated signature-based verification imposes only minor overhead on the server, ensuring efficiency.

The sequential localization method in the integrity verification phase has the same computational overhead as individual verification, so only the dichotomous search-based localization method is analyzed. Table 1 examines the worst-case scenario with all user model parameter ciphertexts corrupted. In most practical cases, only a few ciphertexts are corrupted, leading to performance similar to aggregation verification, as shown in the next section’s experiments. The consistency verification phase combines the first three phases, with both server and user operating on a single aggregated parameter cipher, unaffected by n.

6.2. Experiment

This section analyzes the effectiveness and efficiency of our scheme through simulation experiments. Unlike our approach, most existing parameter integrity verification methods for federated learning probabilistically verify data integrity by randomly selecting a subset of data blocks from each parameter message. We compare our scheme with two methods: one using RSA-based homomorphic functions for per-integrity proofs, and the other using BLS signatures. Both methods generate integrity proofs for each sampled data block, which are then transmitted to the server for verification.

We compare our scheme with RSA-based [

40] and BLS-based [

41] schemes to evaluate its effectiveness and efficiency. Effectiveness is defined by the accuracy in detecting corruption in model parameter messages, with a higher detection probability indicating better performance. Efficiency is measured by computational overhead, with lower computation time indicating better efficiency.

6.2.1. Experimental Setup

The large-scale federated learning simulations and server-side aggregation were conducted on a desktop computer equipped with an Intel(R) Xeon(R) Gold 6226R CPU at 2.90 GHz with 20 GB of memory, running Ubuntu Server 18.04 LTS. To evaluate the feasibility of the proposed framework in realistic UAV edge environments, additional experiments were performed on an Arm-based edge node emulating typical onboard computing platforms, focusing on edge-side operations such as encrypted model update generation, communication overhead, and resource consumption under constrained settings. On the server side, Intel SGX was adopted as the TEE for secure aggregation and verification, providing a hardware-enforced enclave for executing security-critical functions; the experiments were conducted using SGX driver version 2.11 and SGX SDK version 2.12.

The simulations were conducted on a desktop computer with an Intel(R) Xeon(R) Gold 6226R @ 2.90GHz CPU and 20GB of operating memory. Ubuntu Server 18.04 LTS was used as the server-side operating system and Ubuntu 18.04 LTS was used as the user-side operating system. Tested using Intel SGX as the TEE technology, SGX provides a safe area in memory called an enclave for running functions.SGX driver version 2.11 and SGX SDK version 2.12.

CKKS Parameter Configuration: In our implementation, we adopt the CKKS approximate homomorphic encryption scheme to protect local model updates. Specifically, the polynomial modulus degree is set to N = , which provides approximately 128-bit security, according to the standard RLWE security estimates. The coefficient modulus q is composed of a chain of 60-bit primes, yielding a total modulus size of 218 bits. The initial scaling factor is set to .

For the RSA-based scheme, a 512-bit prime is used to generate the integrity proof, with a prime generation determinism of . Both the BLS-based and our scheme use SHA-256 for integrity proof generation and - elliptic curve, which provides security similar to 3072-bit RSA/DSA but with 256-bit points. The curve is defined by and . To simulate corrupted model parameter messages, 1% of data blocks (each 16 KB) are altered to random values based on the local model size.

6.2.2. Model Accuracy Analysis

Model accuracy is a key metric in federated learning performance. We evaluate our scheme using the MNIST dataset, consisting of 70,000 handwritten digit samples (60,000 for training and 10,000 for testing), with 10 digit classes (0-9) and 28x28 grayscale images. The dataset is automatically loaded, split among participants, and 10,000 test samples are sent to the aggregation server. We use a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) with two convolutional layers, two fully connected layers, a 5x5 convolutional kernel, a batch size of 64, and ReLU activation. The output layer uses softmax, and the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.01 is applied for 20 local training epochs. The FedAvg method aggregates user models by averaging parameters on the server.

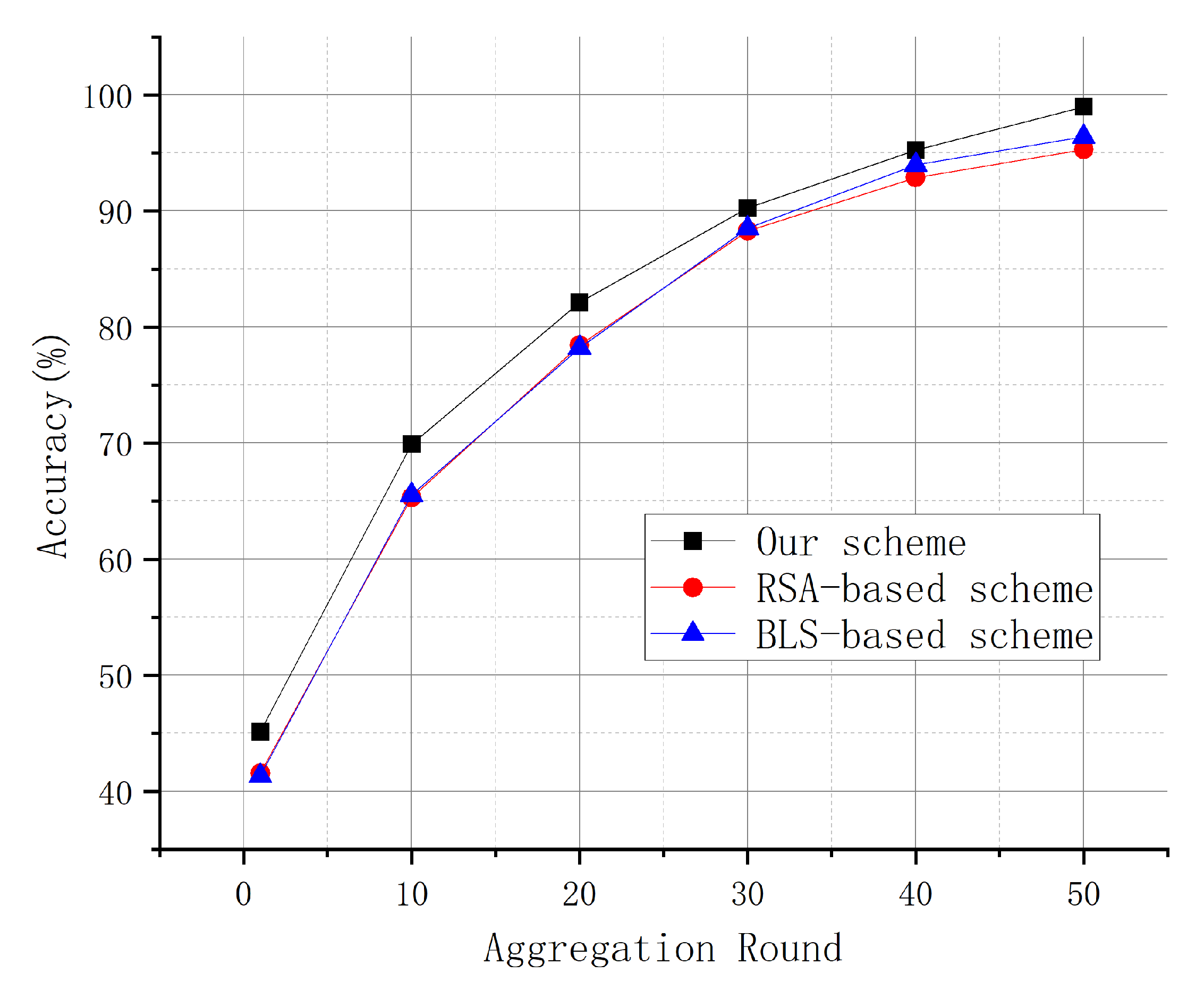

We evaluate the model accuracy of the proposed scheme and compare it with RSA-based and BLS-based federated learning schemes across different aggregation rounds. The results are shown in

Figure 2.

As shown in

Figure 2, we compare the model accuracy of the proposed scheme with RSA-based and BLS-based federated learning schemes across different aggregation rounds. The proposed scheme achieves approximately 3% higher accuracy than the other schemes with relatively low computational overhead. Our scheme demonstrates faster convergence in the early rounds and maintains an accuracy advantage as the number of aggregation rounds increases. After 30 aggregation rounds, the accuracy of all schemes converges and stabilizes. These results show that the proposed scheme improves model performance while maintaining relatively low computational overhead and providing enhanced privacy and security guarantees.

6.2.3. Experimental Analysis of Program Availability

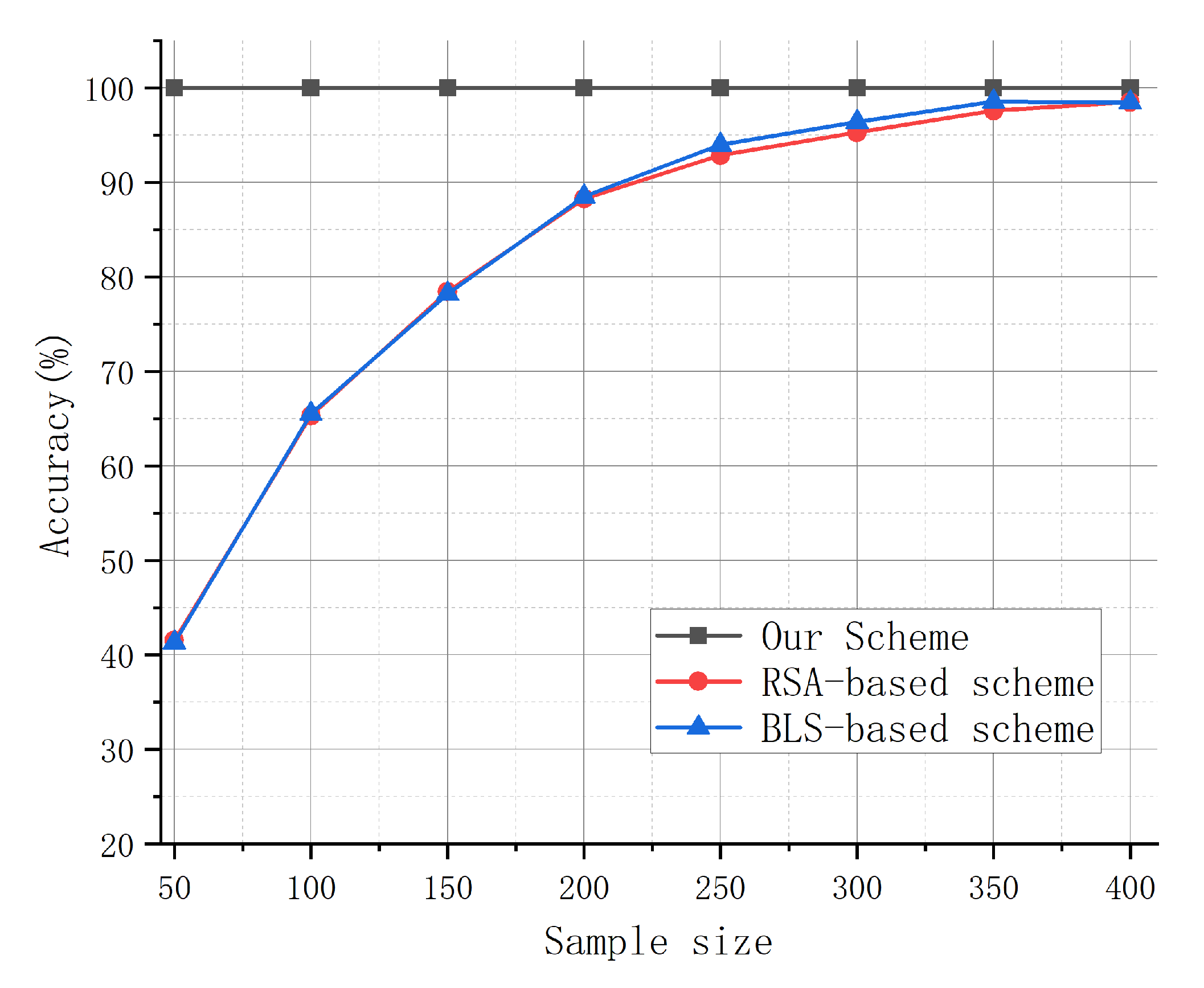

This section compares the effectiveness of our scheme with the RSA-based and BLS-based schemes in detecting data corruption and analyzes their usability in terms of overall computational overhead. While both the RSA and BLS schemes sample a small portion of the data block for inspection, our scheme verifies the entire model parameter message.

Figure 3 compares the inspection accuracies of the three methods with different sample sizes. Our scheme consistently achieves the highest accuracy by checking the entire model parameter message, ensuring complete integrity. In contrast, the accuracy of the RSA-based and BLS-based schemes depends on the sample size and improves as the sample size increases. Both schemes achieve accuracy over 98% when the sample size reaches 400, similar to our scheme, but at the cost of significantly higher computational overhead.

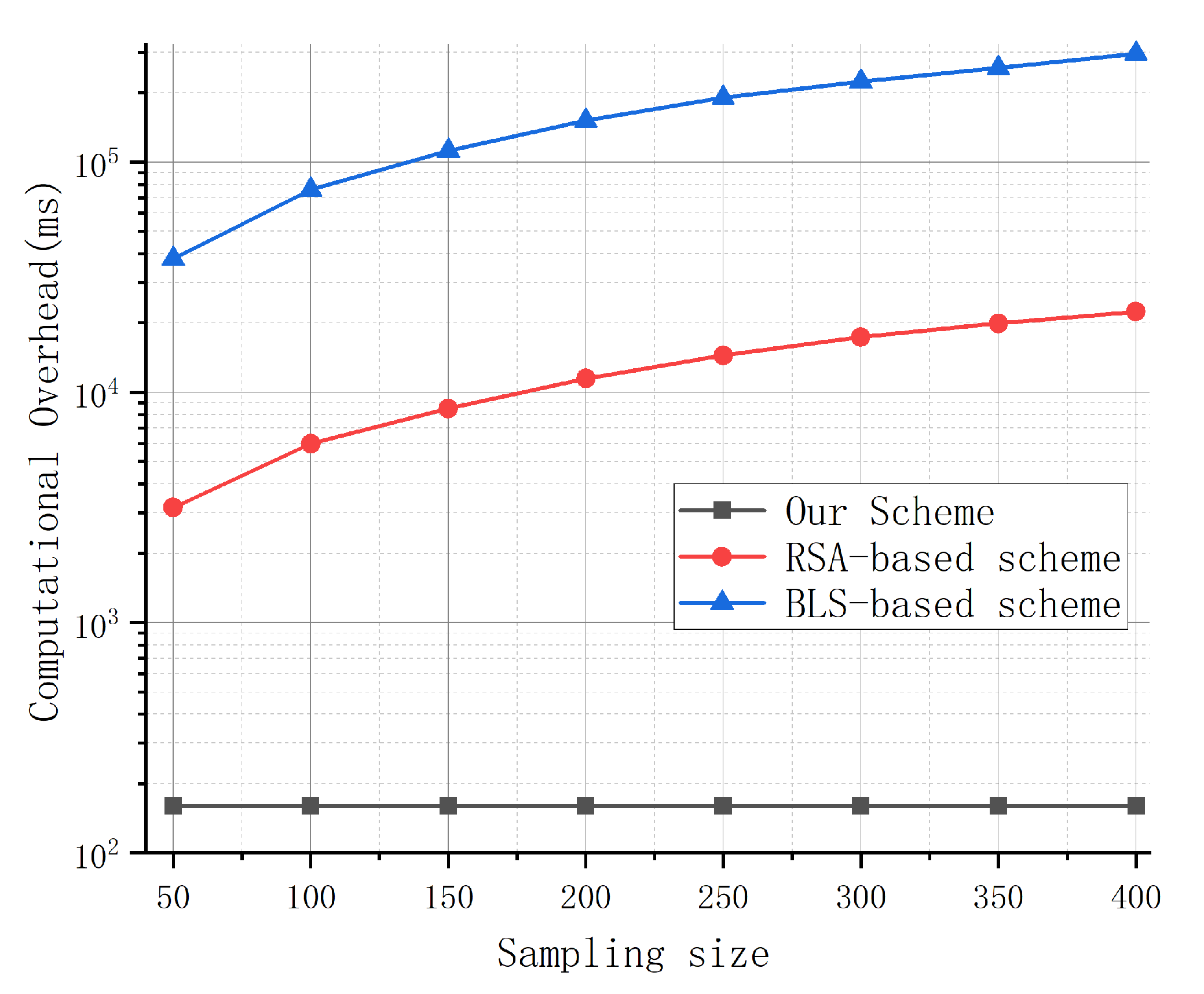

As shown in

Figure 4, the computational overhead of the RSA-based and BLS-based schemes increases rapidly with the sampling size. When the sample size reaches 400, their accuracy approaches that of our scheme, but the computational overhead is too high for efficient inspection. In contrast, the time consumption of our scheme remains stable as the sample size increases, highlighting its better usability. A detailed analysis of its efficiency will be provided in the next section.

6.2.4. Experimental Analysis of Program Efficiency

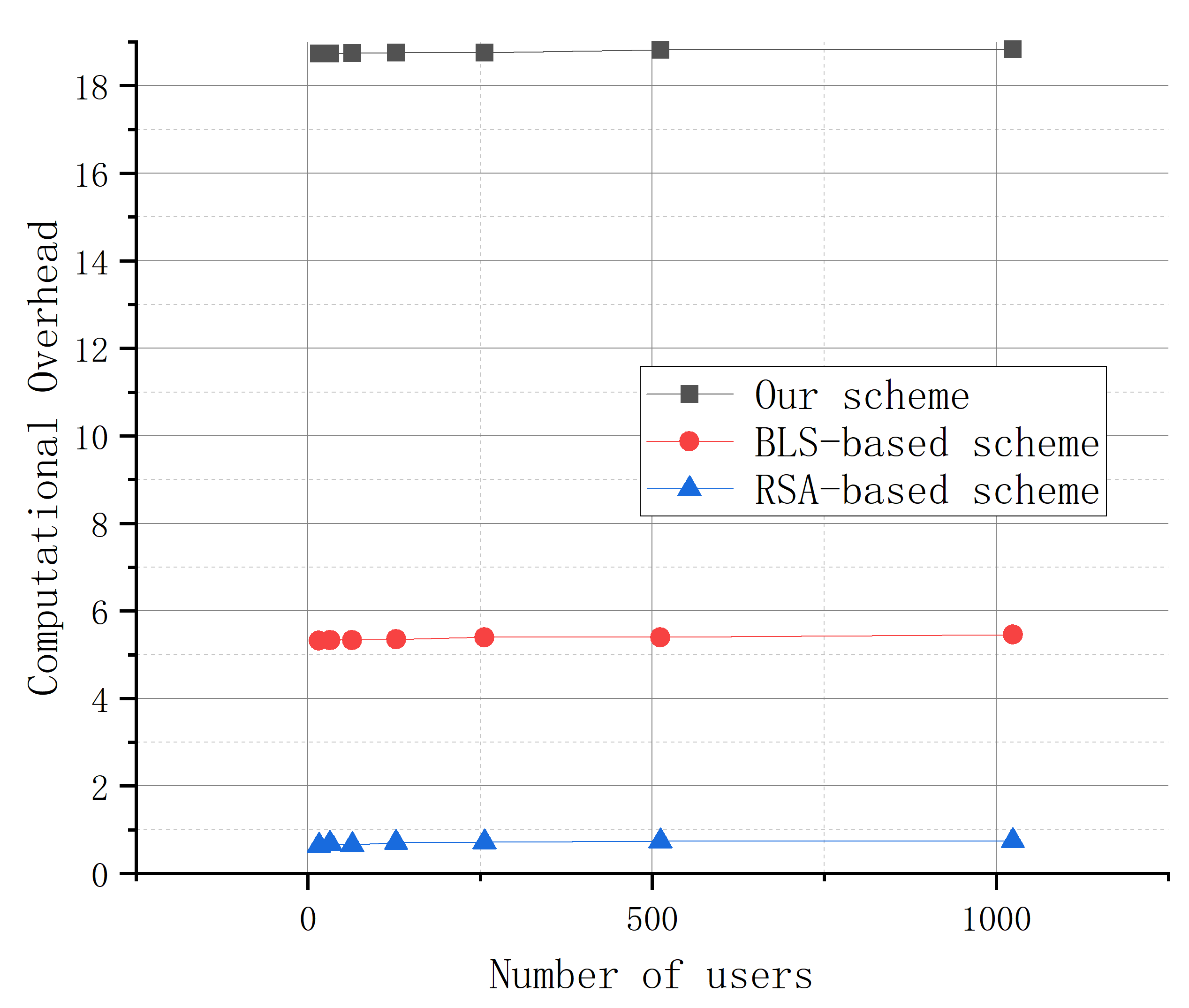

This section compares the efficiency of the RSA-based scheme, the BLS-based scheme, and our scheme, and investigates the impact of the number of users, the size of messages to be verified, and the corruption rate on our scheme. Since the RSA-based scheme and the BLS-based scheme do not have satisfactory localization and consistency detection capabilities, this section analyzes the efficiency of the three schemes in the initialization phase, the parameter upload phase, and the integrity verification phase.

In the initialization phase, all three methods require parameter initialization and inspection request generation, with minimal overhead (less than 0.1ms). The efficiency of generating and sending requests depends on the total number of users.

Figure 5 shows that the RSA- and BLS-based schemes have lower overhead than ours, as our scheme requires generating the server’s private and public keys, which can be pre-computed for efficiency. The number of users has minimal impact on any method’s efficiency. Our scheme takes 18.7ms on average to generate requests, compared to 0.7ms for the RSA-based scheme and 5.3ms for the BLS-based scheme. However, the initialization phase overhead in our scheme is negligible when combined with other phases.

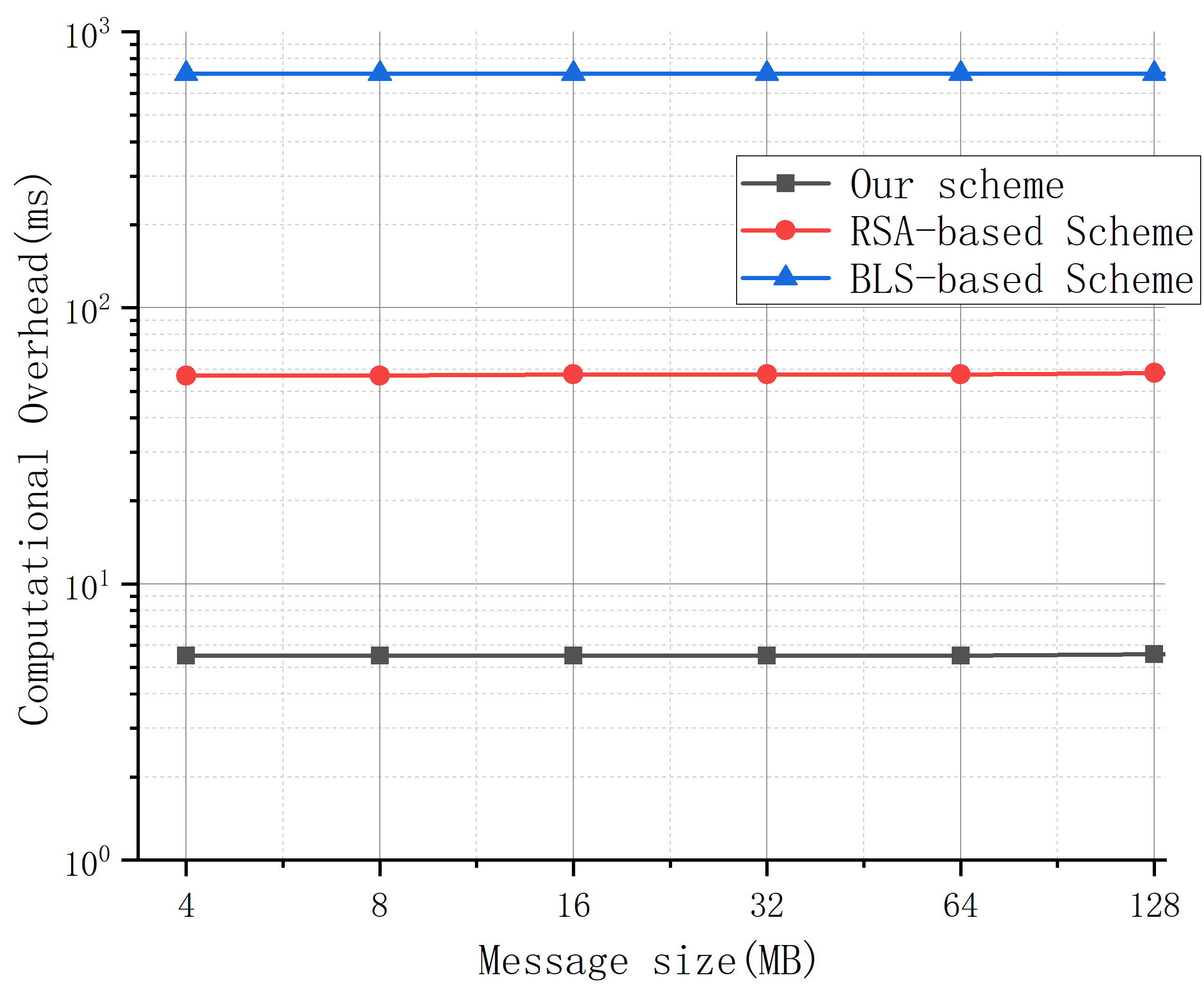

During the parameter upload phase, each user generates an integrity proof for its model parameter message and sends it to the server. Our scheme incurs computational overhead based on the message size, as it generates proofs for the entire message, unlike the RSA- and BLS-based schemes, which only sample a few data blocks. With a fixed sampling ratio, the overhead of the RSA- and BLS-based schemes remains constant.

Figure 6 shows the average overhead when the message size increases from 4MB to 128MB, with 128 users and a sample size of 100. The results indicate that our scheme has significantly lower overhead than the RSA- and BLS-based schemes, taking only 5.7 ms on average, compared to 59.1 ms and 708.2 ms for the RSA and BLS schemes, respectively. This confirms the efficiency of our scheme at the user side.

7. Conclusions

We introduce a secure and verifiable framework for edge federated learning in UAV scenarios. It combines HE, TEE, and aggregate signatures to address key security challenges such as gradient inversion, member inference, and malicious update injection. The framework ensures model update privacy, prevents unauthorized updates, and enhances aggregation integrity with minimal computational overhead. Experimental results demonstrate that, compared to existing schemes, the proposed method provides improved accuracy and efficiency, making it a practical solution for resource-constrained UAV edge environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.S. and Y.Z.; methodology, H.S.; software, Y.Z.; validation, Y.Z., W.Z. and H.Z.; formal analysis, W.Z.; investigation, H.Z.; resources, S.H.; data curation, S.H.; writing—original draft preparation, H.S.; writing—review and editing, Y.Z.; visualization, W.Z.; supervision, H.Z.; project administration, H.S.; funding acquisition, Y.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China grant number L2324126; and Undergraduate Innovation and Entrepreneurship Program (Project Title: Applications of Secret Sharing–Based Privacy-Preserving Federated Learning) grant number XJDC202510300547.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhang C., Xie Y., Bai H. and others. A survey on federated learning. Knowledge-Based Systems 2021, 216, 106775. [CrossRef]

- Kairouz P., McMahan H. B., Avent B. and others. Advances and open problems in federated learning. Foundations and Trends in Machine Learning 2021, 14(1–2), 1–210. [CrossRef]

- Jia N., Qu Z., Ye B., Wang Y., Hu S., Guo S. Federated learning: Strategies for improving communication efficiency. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2025.

- Ferrag M. A., Tihanyi N., Debbah M. Reasoning beyond limits: Advances and open problems for llms. ICT Express 2025.

- Zhang C., Ekanut S., Zhen L. and others. Federated learning: Challenges, methods, and applications. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2022.

- Xie Q., Jiang S., Jiang L. and others. Efficient federated learning with homomorphic encryption for privacy-preserving AI. IEEE Transactions on Artificial Intelligence 2023.

- Wang Y. Optimizing Distributed Computing Resources with Federated Learning: Task Scheduling and Communication Efficiency. Journal of Computer Technology and Software 2025, 4(3).

- Aghaei M., Nikfar A., Shamsolmoali P. and others. Security and privacy in AI systems: Implications of GDPR. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 2021.

- Li X., He Z., Xu F. and others. Federated learning: A privacy-preserving approach to machine learning. IEEE Transactions on Artificial Intelligence 2021.

- Qin L., Zhu T., Zhou W., Yu P. S. Knowledge distillation in federated learning: A survey on long lasting challenges and new solutions. International Journal of Intelligent Systems 2025, 2025(1), pp. 7406934. [CrossRef]

- Ren Y., Leng Y., Cheng Y., Wang J. Secure data storage based on blockchain and coding in edge computing. Math. Biosci. Eng 2019, 16(4), pp. 1874–1892. [CrossRef]

- Dimlioglu T., Choromanska A. Communication-Efficient Distributed Training for Collaborative Flat Optima Recovery in Deep Learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2507.20424 2025. [CrossRef]

- Aubinais E., Gassiat E., Piantanida P. Fundamental limits of membership inference attacks on machine learning models. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2025, 26(263), pp. 1–54.

- Park S., Ye J. C. Multi-task distributed learning using vision transformer with random patch permutation. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 2022, 42(7), 2091–2105. [CrossRef]

- Lu W., Wang J., Chen Y. and others. Personalized federated learning with adaptive batchnorm for healthcare. IEEE Transactions on Big Data 2022.

- Ren Y., Leng Y., Qi J., Sharma P. K., Wang J., Almakhadmeh Z., Tolba A. Multiple cloud storage mechanism based on blockchain in smart homes. Future Generation Computer Systems 2021, 115, pp. 304–313. [CrossRef]

- Thakur A., Sharma P., Clifton D. A. Dynamic neural graphs based federated reptile for semi-supervised multi-tasking in healthcare applications. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 2021, 26(4), 1761–1772. [CrossRef]

- Li J., Jiang M., Qin Y. and others. Intelligent depression detection with asynchronous federated optimization. Complex & Intelligent Systems 2023, 9(1), 115–131.

- Nowroozi E., Haider I., Taheri R., Conti M. Federated learning under attack: Exposing vulnerabilities through data poisoning attacks in computer networks. IEEE Transactions on Network and Service Management 2025.

- Fan X., Wang Y., Huo Y. and others. BEV-SGD: Best effort voting SGD against Byzantine attacks for analog-aggregation-based federated learning over the air. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2022, 9(19), 18946–18959. [CrossRef]

- Jaswal R., Panda S. N., Khullar V. Federated learning: An approach for managing data privacy and security in collaborative learning. Recent Advances in Electrical & Electronic Engineering 2025.

- Zhang K., Song X., Zhang C., Yu S. Challenges and future directions of secure federated learning: A survey. Frontiers of computer science 2022, 16(5), pp. 165817. [CrossRef]

- Xue J., Liu Y., Li S. A Tripartite Federated Learning Framework with Ternary Gradients and Differential Privacy for Secure IoV Data Sharing. In 2025 5th International Symposium on Computer Technology and Information Science (ISCTIS), pp. 682–686. 2025.

- Sun L., Wang Y., Ren Y., Xia F. Path signature-based xai-enabled network time series classification. Science China Information Sciences 2024, 67(7), pp. 170305. [CrossRef]

- Wahab O. A., Rjoub G., Bentahar J. and others. Federated against the cold: A trust-based federated learning approach to counter the cold start problem in recommendation systems. Information Sciences 2022, 601, 189–206. [CrossRef]

- Xie Q., Jiang S., Jiang L., Huang Y., Zhao Z., Khan S., Dai W., Liu Z., Wu K. Efficiency optimization techniques in privacy-preserving federated learning with homomorphic encryption: A brief survey. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2024, 11(14), pp. 24569–24580. [CrossRef]

- Madi A., Stan O., Mayoue A. and others. A secure federated learning framework using homomorphic encryption and verifiable computing. Proceedings of RDAAPS 2021, 1–8.

- Zhang C., Ekanut S., Zhen L. and others. Augmented multi-party computation against gradient leakage in federated learning. IEEE Transactions on Big Data 2022, 10(6), 742–751. [CrossRef]

- Xie Q., Jiang S., Jiang L. and others. Efficiency optimization techniques in privacy-preserving federated learning with homomorphic encryption: A brief survey. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2024, 11(14), 24569–24580. [CrossRef]

- Jin W., Yao Y., Han S., Gu J., Joe-Wong C., Ravi S., Avestimehr S., He C. FedML-HE: An efficient homomorphic-encryption-based privacy-preserving federated learning system. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.10837 2023.

- Ren Y., Lv Z., Xiong N. N., Wang J. HCNCT: A cross-chain interaction scheme for the blockchain-based metaverse. ACM Transactions on Multimedia Computing, Communications and Applications 2024, 20(7), pp. 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Li Y., Li H., Xu G. and others. Efficiency in unreliable users. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2021, 9(13), 11590–11603. [CrossRef]

- He C., Liu G., Guo S. and others. Privacy-preserving and low-latency federated learning in edge computing. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2022, 9(20), 20149–20159. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L., Xu J., Vijayakumar P. and others. Homomorphic encryption-based privacy-preserving federated learning in IoT-enabled healthcare system. IEEE Transactions on Network Science and Engineering 2022, 10(5), 2864–2880. [CrossRef]

- Wang B., Li H., Guo Y. and others. PPFLHE: A privacy-preserving federated learning scheme with homomorphic encryption for healthcare data. Applied Soft Computing 2023, 146, 110677. [CrossRef]

- Firdaus M., Rhee K. H. Secure federated learning with blockchain and homomorphic encryption for healthcare data sharing. Proceedings of the International Conference on Cyberworlds (CW) 2024, 257–263.

- Mantey E. A., Zhou C., Anajemba J. H. and others. Federated learning approach for secured medical recommendation in internet of medical things using homomorphic encryption. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 2024, 28(6), 3329–3340. [CrossRef]

- Liu C., Guo H., Xu M. and others. Extending on-chain trust to off-chain—Trustworthy blockchain data collection using trusted execution environment (TEE). IEEE Transactions on Computers 2022, 71(12), 3268–3280. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y., Zhang Z., He N. and others. Symgx: Detecting cross-boundary pointer vulnerabilities of SGX applications via static symbolic execution. Proceedings of the ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security (CCS) 2023, 2710–2724.

- Luo F., Wang H., Yan X. Comments on “VERSA: Verifiable secure aggregation for cross-device federated learning”. IEEE Transactions on Dependable and Secure Computing 2023, 21(1), 499–500. [CrossRef]

- Gao H., He N., Gao T. SVeriFL: Successive verifiable federated learning with privacy-preserving. Information Sciences 2023, 622, 98–114. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).