Submitted:

14 January 2026

Posted:

16 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

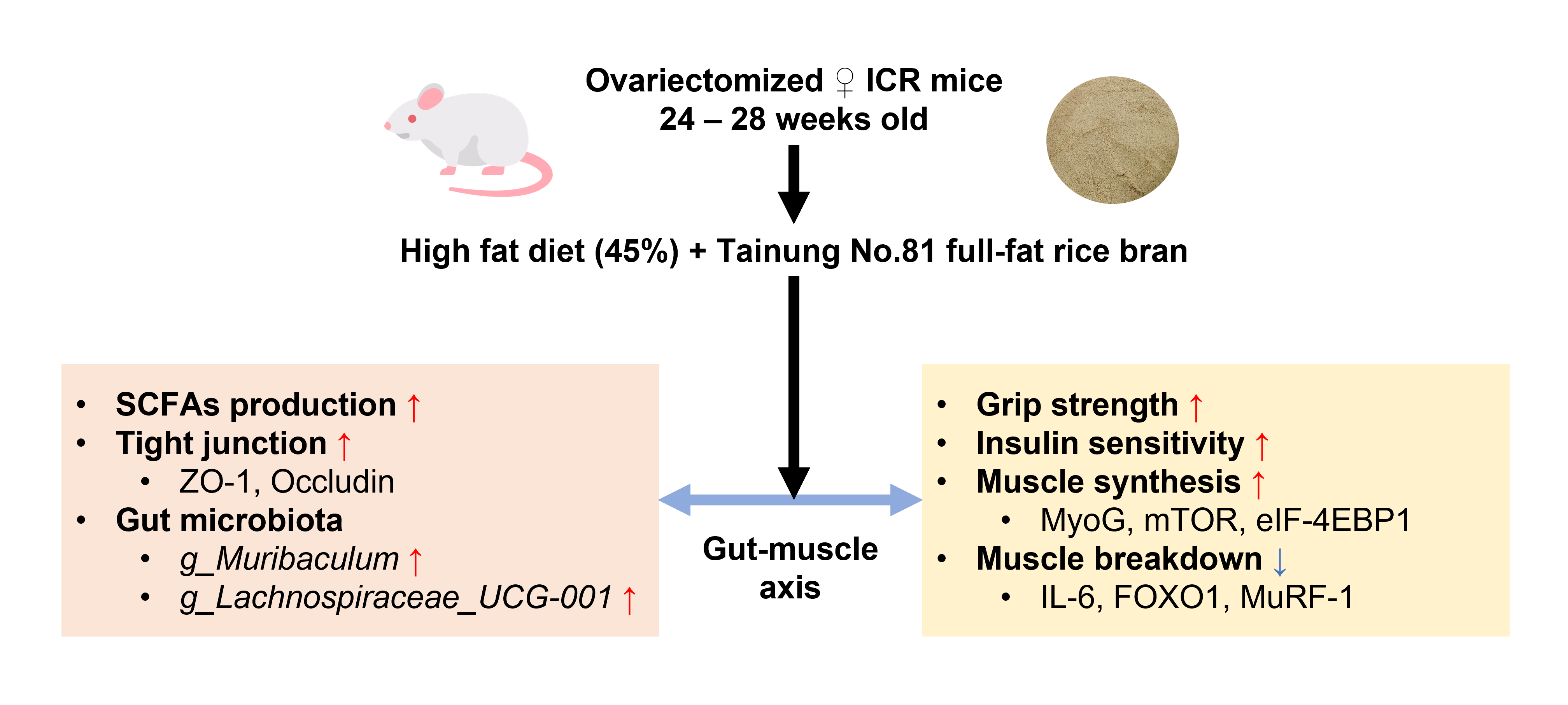

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Rice Bran Preparation

2.2. Animals and Study Design

2.3. Grip Strength Measurement

2.4. Intraperitoneal Glucose Tolerance Test

2.5. Plasma Biochemical Analysis

2.6. Histological Analysis

2.7. RT-qPCR Gene Expression Analysis

2.8. Short-Chain Fatty Acids Analysis

2.9. Cecum Microbiota Analysis

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Nutrient Composition of Full-Fat Rice Bran

3.2. Effect of Full-Fat Rice Bran on Obesity-Related Indices

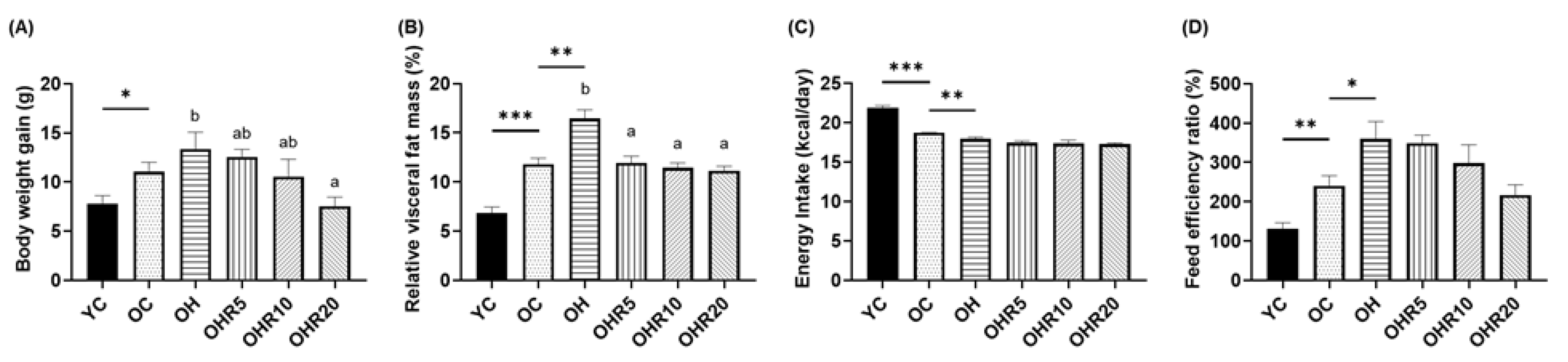

3.2.1. Body Weight Gain and Visceral Fat Mass

3.2.2. Energy Intake and Food Efficiency Ratio

3.3. Effect of Full-Fat Rice Bran on Lipid and Glucose Homeostasis

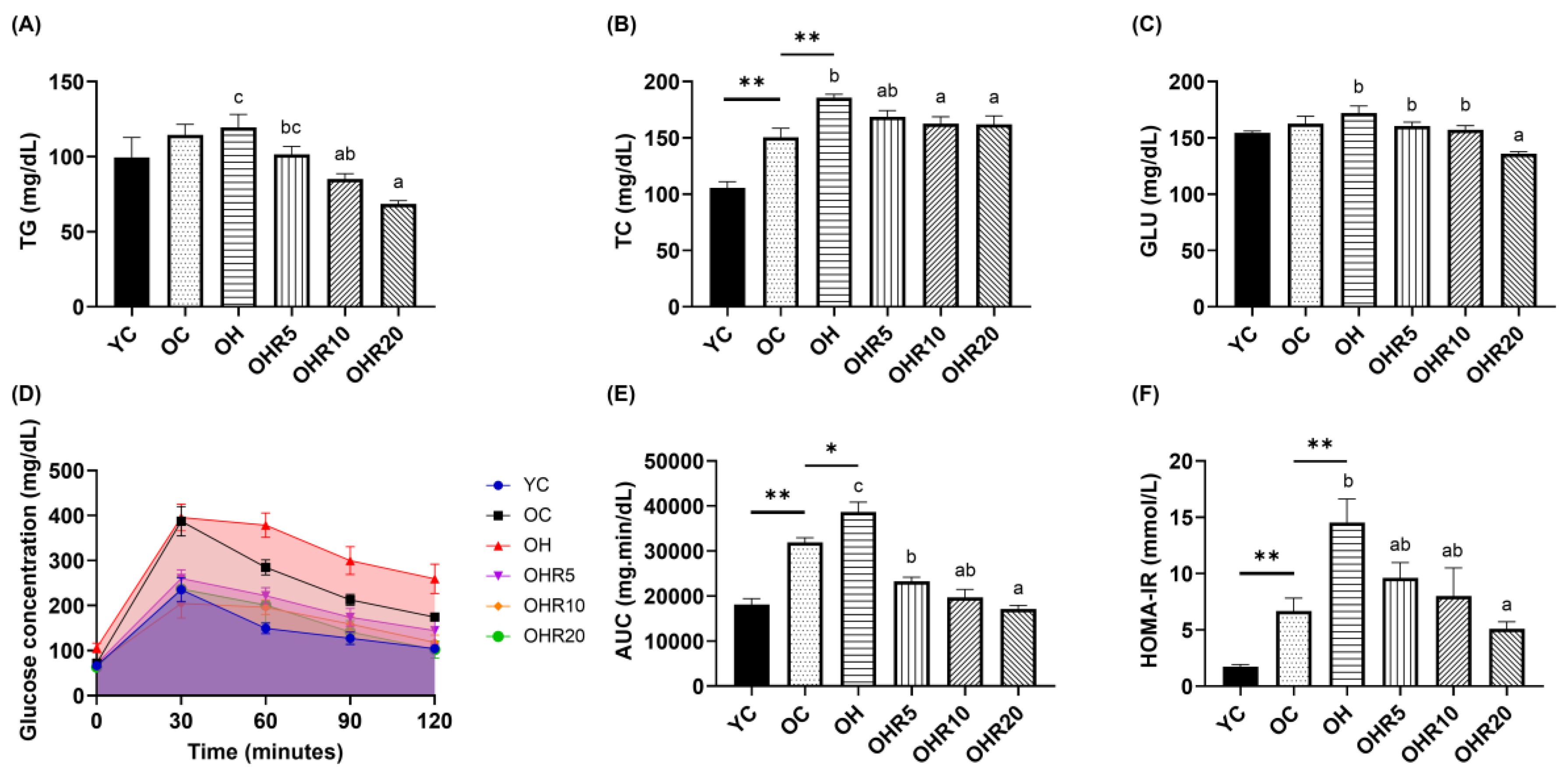

3.3.1. Plasma Lipid Profile

3.3.2. Glucose Profile

3.4. Effect of Full-Fat Rice Bran on Muscle

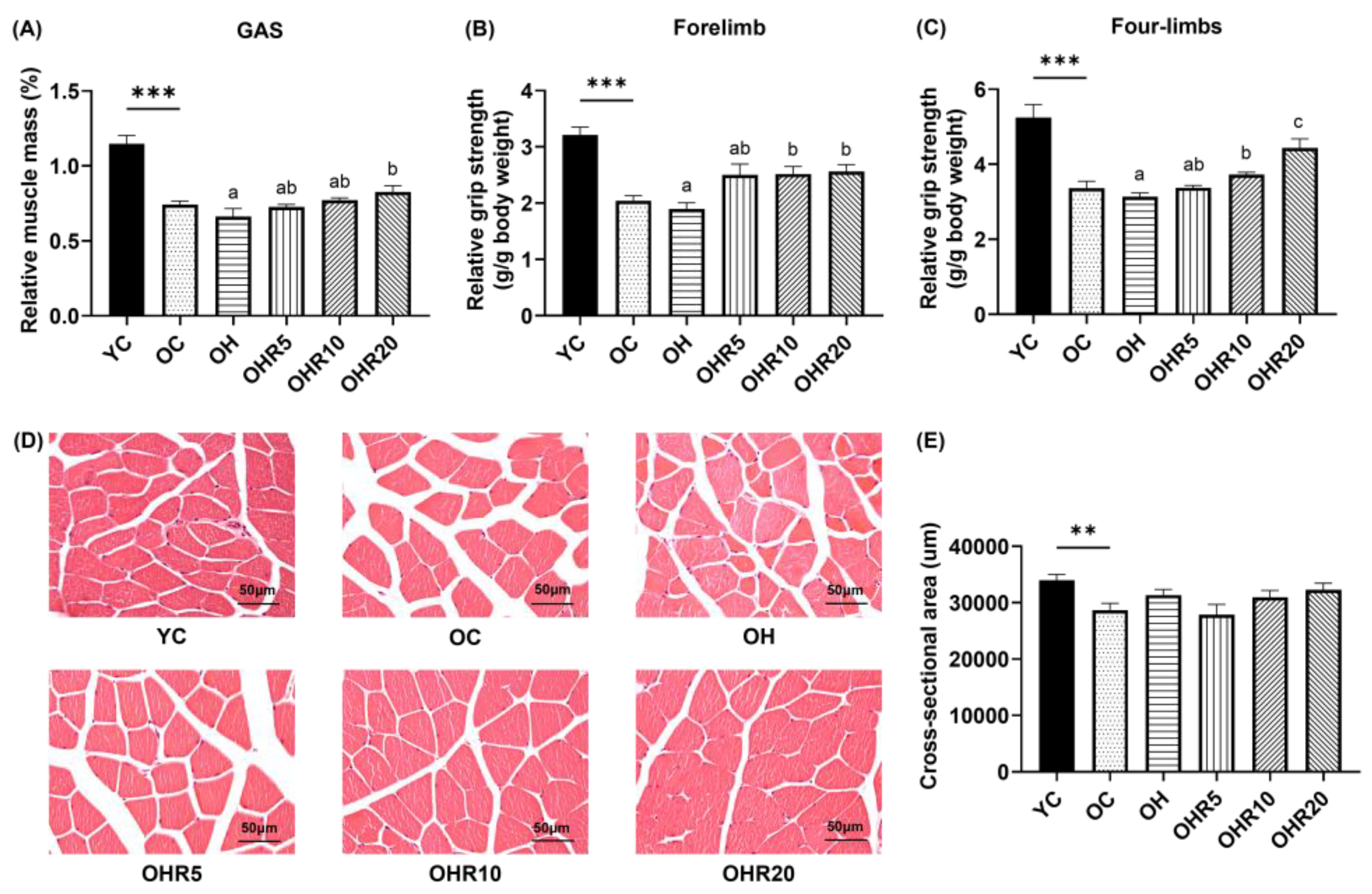

3.4.1. Muscle Mass

3.4.2. Grip Strength

3.4.3. Muscle Morphology

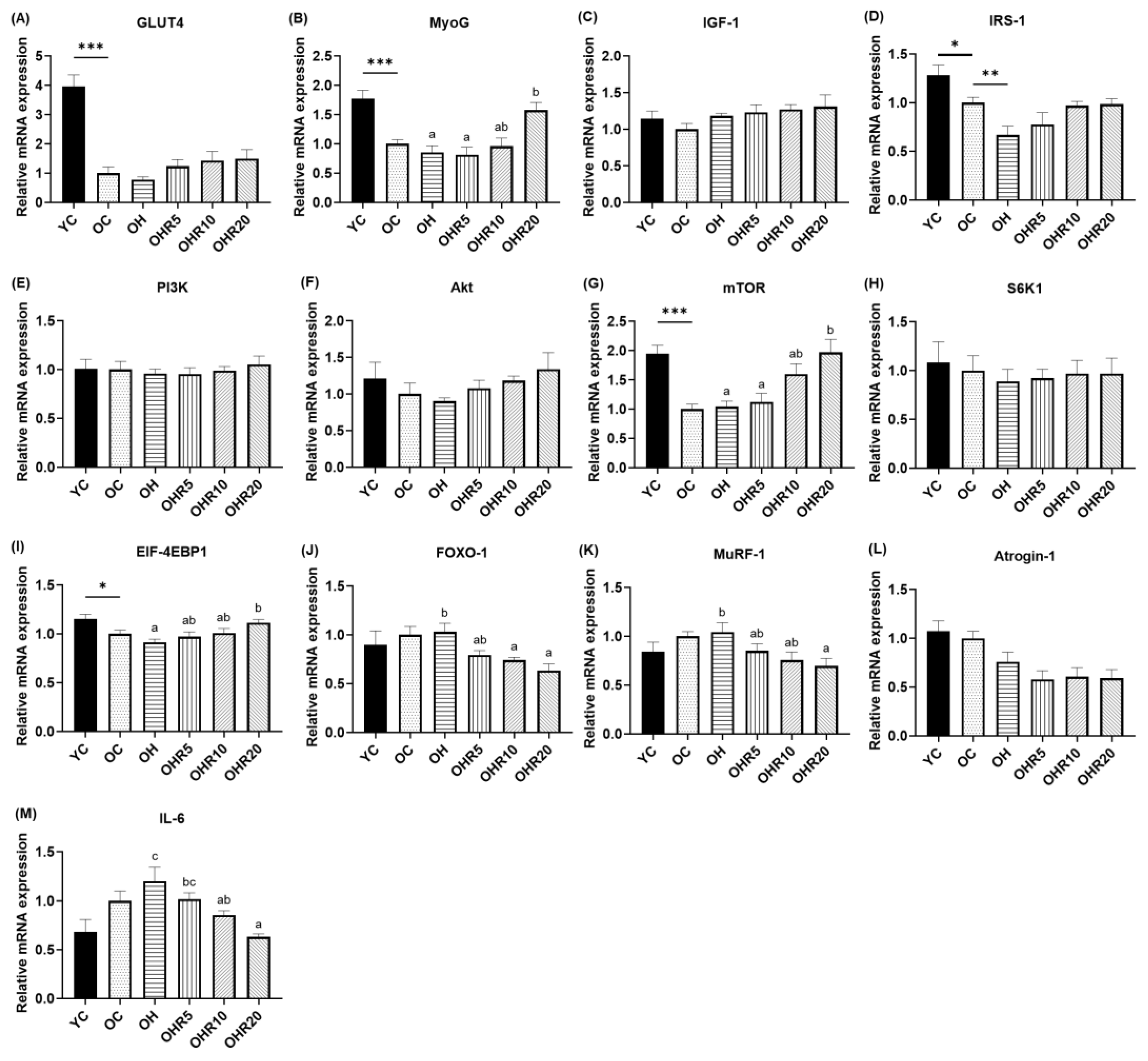

3.4.4. Muscle Protein Synthesis Gene Expressions

3.4.5. Muscle Protein Degradation and Inflammatory Gene Expression Levels

3.5. Effect of Full-Fat Rice Bran on Large Intestinal Barrier Function and Gut Microbiota

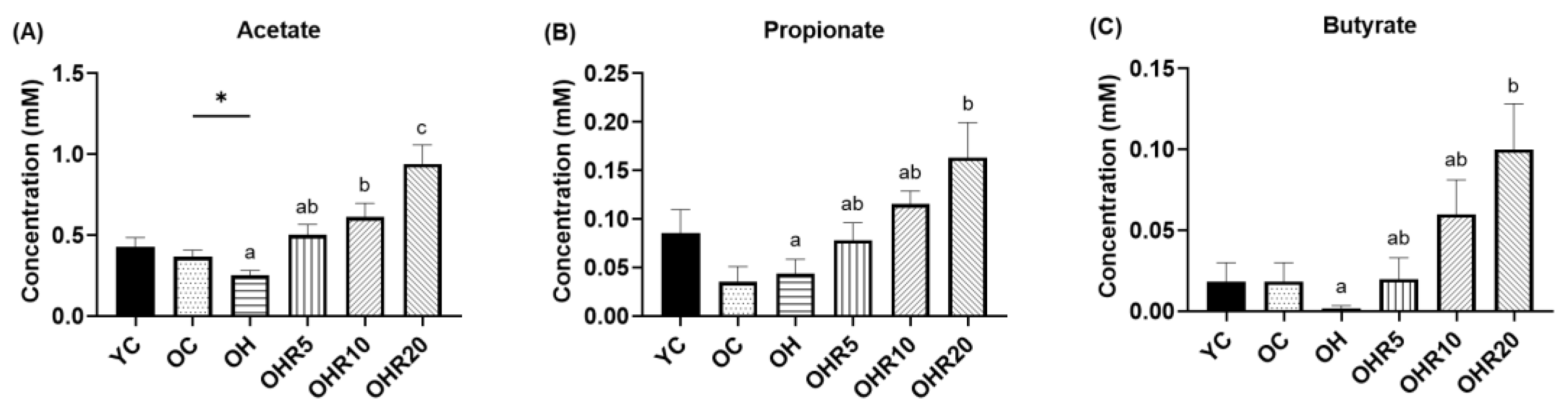

3.5.1. Short-Chain Fatty Acids Production

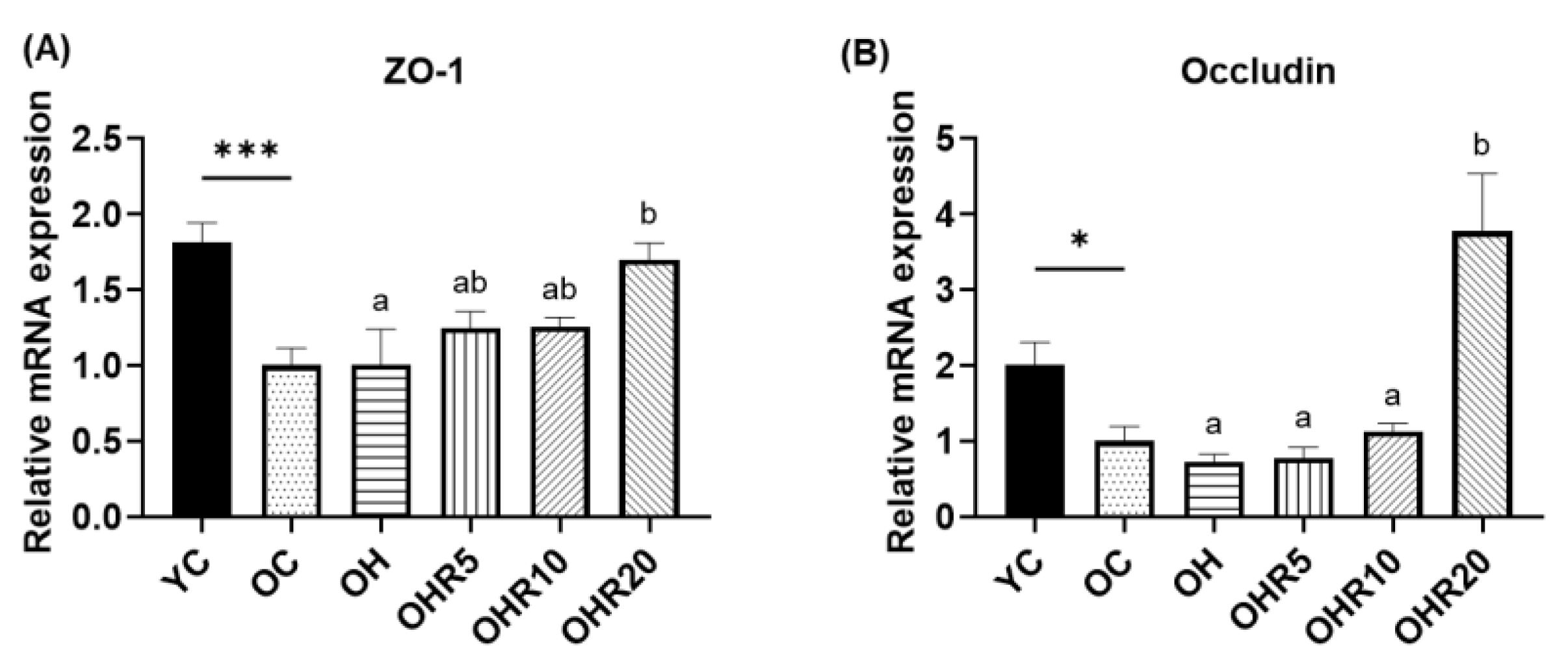

3.5.2. Intestinal Tight Junction

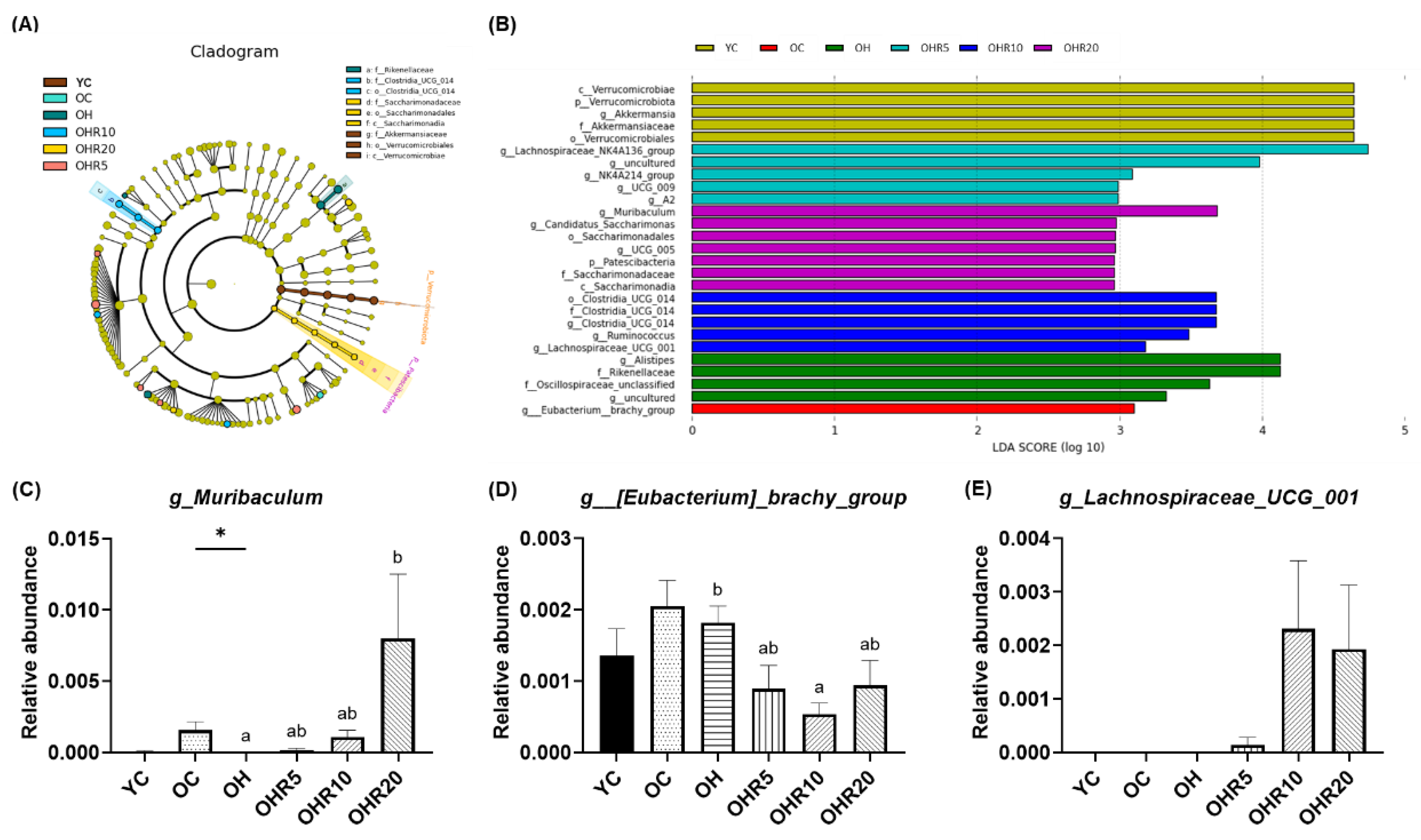

3.5.3. Gut microbiota Composition

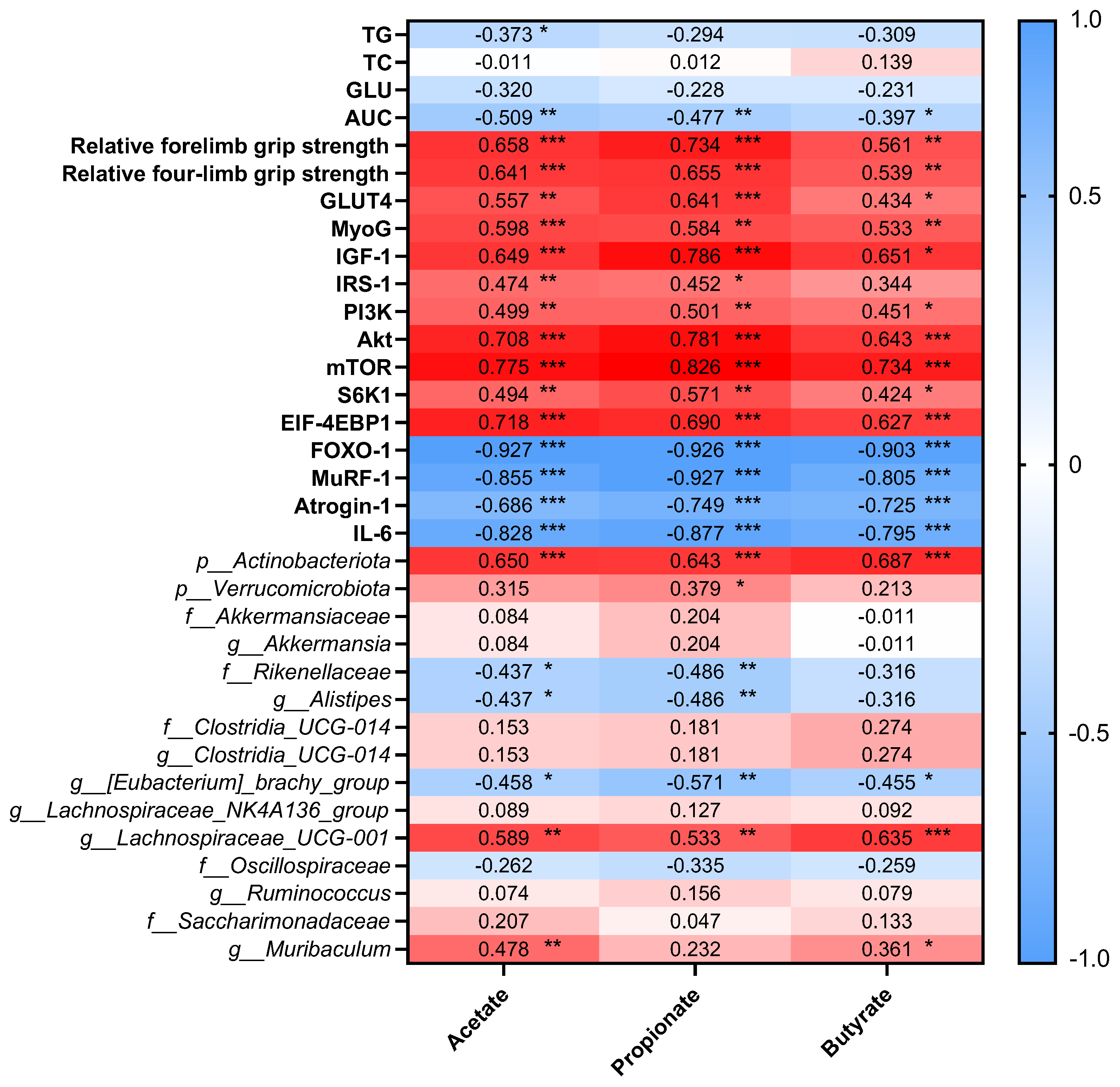

3.6. Correlation Between Short-Chain Fatty Acids, Blood Parameters, Muscle-Related Markers, and Gut Microbiota

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Akt | Alpha serine/threonine-protein kinase |

| AUC | Area under curve |

| eIF-4EBP1 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E binding protein 1 |

| FER | Food efficiency ratio |

| FFRB | Full-fat rice bran |

| FOXO1 | Forkhead box protein O1 |

| GAS | Gastrocnemius |

| GLU | Glucose |

| GLUT4 | Glucose transporter type 4 |

| HFD | High-fat diet |

| HOMA-IR | Homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance |

| IGF-1 | Insulin-like growth factor 1 |

| IL-6 | Interleukin 6 |

| IPGTT | Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test |

| IRS-1 | Insulin receptor substrate 1 |

| LDA | Linear discriminant analysis |

| LEfSe | Linear discriminant analysis effect size |

| mTOR | Mammalian target of rapamycin |

| MuRF-1 | Muscle RING-finger protein-1 |

| MyoG | Myogenin |

| OVX | Ovariectomized |

| PI3K | Phosphatidylinositol3-kinase |

| RT-qPCR | Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| S6K1 | Ribosomal protein S6 kinase beta-1 |

| SCFAs | Short-chain fatty acids |

| SEM | Standard error mean |

| TC | Total cholesterol |

| TG | Triglycerides |

| TNG81 | Tainung No. 81 |

| ZO-1 | Zonula occludens-1 |

References

- Landgren, B.M.; Collins, A.; Csemiczky, G.; Burger, H.G.; Baksheev, L.; Robertson, D.M. Menopause transition: Annual changes in serum hormonal patterns over the menstrual cycle in women during a nine-year period prior to menopause. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004, 89, 2763–2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, S.H.; Kim, H.S. Menopause-Associated Lipid Metabolic Disorders and Foods Beneficial for Postmenopausal Women. Nutrients 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltais, M.L.; Desroches, J.; Dionne, I.J. Changes in muscle mass and strength after menopause. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact 2009, 9, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Deschenes, M.R. Effects of aging on muscle fibre type and size. Sports Med 2004, 34, 809–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romanick, M.; Thompson, L.V.; Brown-Borg, H.M. Murine models of atrophy, cachexia, and sarcopenia in skeletal muscle. Biochim Biophys Acta 2013, 1832, 1410–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geraci, A.; Calvani, R.; Ferri, E.; Marzetti, E.; Arosio, B.; Cesari, M. Sarcopenia and Menopause: The Role of Estradiol. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2021, 12, 682012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, S.M.; Metter, E.J.; Ling, S.; Ferrucci, L. Inflammatory factors in age-related muscle wasting. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2006, 18, 625–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Colla, A.; Pronsato, L.; Milanesi, L.; Vasconsuelo, A. 17beta-Estradiol and testosterone in sarcopenia: Role of satellite cells. Ageing Res Rev 2015, 24, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, S.T.; Cooley, I.D. The effect of physiological stimuli on sarcopenia; impact of Notch and Wnt signaling on impaired aged skeletal muscle repair. Int J Biol Sci 2012, 8, 731–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, A.; Luckey, D.; Taneja, V. The gut microbiome in autoimmunity: Sex matters. Clin Immunol 2015, 159, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.L.; Cao, Y.; Liang, J.H.; Tang, R.Y.; Wu, S.; Zhang, P.; Chen, R. The influence of the gut microbiome on ovarian aging. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2295394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Zhang, P.; Duan, H.; Wang, J.; Qiu, Y.; Cui, Z.; Yin, Y.; Wan, D.; Xie, L. Gut microbiota in muscular atrophy development, progression, and treatment: New therapeutic targets and opportunities. Innovation (Camb) 2023, 4, 100479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mostafavi Abdolmaleky, H.; Zhou, J.R. Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis, Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Epigenetic Alterations in Metabolic Diseases. Antioxidants (Basel) 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, M.; Bruunsgaard, H.; Weis, N.; Hendel, H.W.; Andreassen, B.U.; Eldrup, E.; Dela, F.; Pedersen, B.K. Circulating levels of TNF-alpha and IL-6-relation to truncal fat mass and muscle mass in healthy elderly individuals and in patients with type-2 diabetes. Mech Ageing Dev 2003, 124, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Beek, C.M.; Dejong, C.H.C.; Troost, F.J.; Masclee, A.A.M.; Lenaerts, K. Role of short-chain fatty acids in colonic inflammation, carcinogenesis, and mucosal protection and healing. Nutr Rev 2017, 75, 286–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Xu, M.; Wang, H.; Zhu, L. Role and Mechanism of Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Skeletal Muscle Homeostasis and Exercise Performance. Nutrients 2025, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartori, R.; Romanello, V.; Sandri, M. Mechanisms of muscle atrophy and hypertrophy: implications in health and disease. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiaffino, S.; Mammucari, C. Regulation of skeletal muscle growth by the IGF1-Akt/PKB pathway: insights from genetic models. Skelet Muscle 2011, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandri, M.; Barberi, L.; Bijlsma, A.Y.; Blaauw, B.; Dyar, K.A.; Milan, G.; Mammucari, C.; Meskers, C.G.; Pallafacchina, G.; Paoli, A.; et al. Signalling pathways regulating muscle mass in ageing skeletal muscle: the role of the IGF1-Akt-mTOR-FoxO pathway. Biogerontology 2013, 14, 303–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.L.; Norhaizan, M.E.; Chan, L.C. Rice Bran: From Waste to Nutritious Food Ingredients. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mn, L.; Venkatachalapathy, N.; Manickavasagan, A. Physicochemical Characteristics of Rice Bran; 2017; pp. 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodie, A.R.; Micciche, A.C.; Atungulu, G.G.; Rothrock, M.J.; Ricke, S.C. Current Trends of Rice Milling Byproducts for Agricultural Applications and Alternative Food Production Systems. Front Sustain Food S 2019, 3, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, M.Z.; Das, P.P.; Babu, K.R.; Juarez-Colunga, S.; Weber, A.M.; Yoosuf, B.; Alex, A.S.; Srivastava, R.K.; Marathi, B.; Patel, S.; et al. Rice Bran: A Comprehensive Review of Phytochemicals and Bioactive Components With Therapeutic Potential and Health Benefits. Nutr Rev 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tajasuwan, L.; Kettawan, A.; Rungruang, T.; Wunjuntuk, K.; Prombutara, P. Role of Dietary Defatted Rice Bran in the Modulation of Gut Microbiota in AOM/DSS-Induced Colitis-Associated Colorectal Cancer Rat Model. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Dong, L.; Jia, X.; Liu, L.; Chi, J.; Huang, F.; Ma, Q.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, R. Bound Phenolics Ensure the Antihyperglycemic Effect of Rice Bran Dietary Fiber in db/db Mice via Activating the Insulin Signaling Pathway in Skeletal Muscle and Altering Gut Microbiota. J Agric Food Chem 2020, 68, 4387–4398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.X.; Yeh, C.L.; Yang, S.C.; Shirakawa, H.; Chang, C.L.; Chen, L.H.; Chiu, Y.S.; Chiu, W.C. Rice Bran Supplementation Ameliorates Gut Dysbiosis and Muscle Atrophy in Ovariectomized Mice Fed with a High-Fat Diet. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Yang, H.; Song, S.; Liu, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J. Bioactive Components in Whole Grains for the Regulation of Skeletal Muscle Function. Foods 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusbana, T.B.; Agista, A.Z.; Saputra, W.D.; Ohsaki, Y.; Watanabe, K.; Ardiansyah, A.; Budijanto, S.; Koseki, T.; Aso, H.; Komai, M.; Shirakawa, H. Supplementation with Fermented Rice Bran Attenuates Muscle Atrophy in a Diabetic Rat Model. Nutrients 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.M.; Chung, H.J.; Lim, S.T. Effect of various heat treatments on rancidity and some bioactive compounds of rice bran. J Cereal Sci 2014, 60, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, M.; Ridla, M.; Sukria, H. The Optimal Condition of Dry-Heat Stabilization using Oven on Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Activity of Rice Bran: A Meta-Analysis. Buletin Peternakan 2023, 47, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, A.; Zhang, T.; Li, Y.; Zhao, H. Gas Chromatography Detection Protocol of Short-chain Fatty Acids in Mice Feces. Bio Protoc 2020, 10, e3672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Fernandez, M.E.; Sharma, V.; Stankiewicz, T.E.; Oates, J.R.; Doll, J.R.; Damen, M.; Almanan, M.; Chougnet, C.A.; Hildeman, D.A.; Divanovic, S. Aging mitigates the severity of obesity-associated metabolic sequelae in a gender independent manner. Nutr Diabetes 2021, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Ju, X.; Chen, W.; Yuan, J.; Wang, Z.; Aluko, R.E.; He, R. Rice bran attenuated obesity via alleviating dyslipidemia, browning of white adipocytes and modulating gut microbiota in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Food Funct 2020, 11, 2406–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son, J.E.; Jo, J.Y.; Kim, S.; Park, M.J.; Lee, Y.R.; Park, S.S.; Park, S.Y.; Jung, S.M.; Jung, S.K.; Kim, J.Y.; Byun, S. Rice Bran Extract Suppresses High-Fat Diet-Induced Hyperlipidemia and Hepatosteatosis through Targeting AMPK and STAT3 Signaling. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.C.; Huang, W.C.; Ng, X.E.; Lee, M.C.; Hsu, Y.J.; Huang, C.C.; Wu, H.H.; Yeh, C.L.; Shirakawa, H.; Budijanto, S.; et al. Rice Bran Reduces Weight Gain and Modulates Lipid Metabolism in Rats with High-Energy-Diet-Induced Obesity. Nutrients 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samra, R.A.; Anderson, G.H. Insoluble cereal fiber reduces appetite and short-term food intake and glycemic response to food consumed 75 min later by healthy men. Am J Clin Nutr 2007, 86, 972–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcotte, L.P.; Fisher, J.S. Skeletal muscle insulin resistance: roles of fatty acid metabolism and exercise. Phys Ther 2008, 88, 1279–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.Y.; Shin, K.O.; Woo, J.; Woo, S.H.; Jang, K.S.; Lee, Y.H.; Kang, S. Exercise and dietary change ameliorate high fat diet induced obesity and insulin resistance via mTOR signaling pathway. J Exerc Nutrition Biochem 2016, 20, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Lee, H.; Yoo, A.; Jeong, H.Y.; Jung, C.H.; Ahn, J.; Ha, T.Y. Gromwell (Lithospermum erythrorhizon) Attenuates High-Fat-Induced Skeletal Muscle Wasting by Increasing Protein Synthesis and Mitochondrial Biogenesis. J Microbiol Biotechnol 2024, 34, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Gayo, A.; Felix-Soriano, E.; Sainz, N.; Gonzalez-Muniesa, P.; Moreno-Aliaga, M.J. Changes Induced by Aging and Long-Term Exercise and/or DHA Supplementation in Muscle of Obese Female Mice. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikary, S.; Kothari, P.; Choudhary, D.; Tripathi, A.K.; Trivedi, R. Glucocorticoid aggravates bone micro-architecture deterioration and skeletal muscle atrophy in mice fed on high-fat diet. Steroids 2019, 149, 108416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, N.H.; Kim, C.S.; Park, T.; Park, J.H.; Sung, M.K.; Lee, D.G.; Hong, S.M.; Choe, S.Y.; Goto, T.; Kawada, T.; Yu, R. Quercetin protects against obesity-induced skeletal muscle inflammation and atrophy. Mediators Inflamm 2014, 2014, 834294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Kim, M.B.; Kim, C.; Hwang, J.K. Whole grain cereal attenuates obesity-induced muscle atrophy by activating the PI3K/Akt pathway in obese C57BL/6N mice. Food Sci Biotechnol 2018, 27, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammad, S.; Thiemermann, C. Role of Metabolic Endotoxemia in Systemic Inflammation and Potential Interventions. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 594150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, H.; Gholami, A.M.; Berry, D.; Desmarchelier, C.; Hahne, H.; Loh, G.; Mondot, S.; Lepage, P.; Rothballer, M.; Walker, A.; et al. High-fat diet alters gut microbiota physiology in mice. ISME J 2014, 8, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.L.; Chi, M.M.; Scull, B.P.; Rigby, R.; Schwerbrock, N.M.J.; Magness, S.; Jobin, C.; Lund, P.K. High-Fat Diet: Bacteria Interactions Promote Intestinal Inflammation Which Precedes and Correlates with Obesity and Insulin Resistance in Mouse. Plos One 2010, 5, e12191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, A.K.; Vairappan, B. Role of zonula occludens in gastrointestinal and liver cancers. World J Clin Cases 2022, 10, 3647–3661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balda, M.S.; Matter, K. Tight junctions at a glance. J Cell Sci 2008, 121, 3677–3682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, W.T.; Odenwald, M.A.; Turner, J.R.; Zuo, L. Tight junction proteins occludin and ZO-1 as regulators of epithelial proliferation and survival. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2022, 1514, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Y.A.; Shen, J.Y.; Fan, R.; Xiao, R.; Ma, W.W. High-fat diets containing different types of fatty acids modulate gut-brain axis in obese mice. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2022, 19, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujawdiya, P.K.; Sharma, P.; Sharad, S.; Kapur, S. Reversal of Increase in Intestinal Permeability by Seed Kernel Extract in High-Fat Diet-Induced Obese Mice. Pharmaceuticals-Base 2020, 13, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duansak, N.; Schmid-Schonbein, G.W.; Srisawat, U. Anti-Obesity Effect of Rice Bran Extract on High-Fat Diet-Induced Obese Mice. Prev Nutr Food Sci 2022, 27, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyes, T.; Silaghi, C.N.; Craciun, A.M. Diet-Related Changes of Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Blood and Feces in Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome. Biology (Basel) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, N.; Arboleya, S.; Fernandez-Navarro, T.; de Los Reyes-Gavilan, C.G.; Gonzalez, S.; Gueimonde, M. Age-Associated Changes in Gut Microbiota and Dietary Components Related with the Immune System in Adulthood and Old Age: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco, W.; Lorenzo, M.B.; Cintoni, M.; Porcari, S.; Rinninella, E.; Kaitsas, F.; Lener, E.; Mele, M.C.; Gasbarrini, A.; Collado, M.C.; et al. Short-Chain Fatty-Acid-Producing Bacteria: Key Components of the Human Gut Microbiota. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, D.J.; Preston, T. Formation of short chain fatty acids by the gut microbiota and their impact on human metabolism. Gut Microbes 2016, 7, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, K.; Xu, J.J.; Shen, L.; Zhao, H.; Gou, W.; Xu, F.; Fu, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Shuai, M.; Li, B.Y.; et al. Comparison of fecal and blood metabolome reveals inconsistent associations of the gut microbiota with cardiometabolic diseases. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| YC | OC | OH | OHR5 | OHR10 | OHR20 | |

| Energy (kcal) | 3808.00 | 3808.00 | 4808.00 | 4842.40 | 4874.30 | 4943.60 |

| Protein (kcal%) | 14.90 | 14.90 | 11.81 | 11.73 | 11.65 | 11.57 |

| Fat (kcal%) | 9.50 | 9.50 | 44.93 | 44.63 | 44.37 | 43.62 |

| Carbohydrate (kcal%) | 75.60 | 75.60 | 43.26 | 43.63 | 43.98 | 44.81 |

| Ingredients (g/kg) | ||||||

| Cornstarch | 465.0 | 465.0 | 265.0 | 244.0 | 222.5 | 182.0 |

| Maltodextrin | 155.0 | 155.0 | 155.0 | 155.0 | 155.0 | 155.0 |

| Sucrose | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Casein | 140.0 | 140.0 | 140.0 | 133.0 | 125.9 | 112.8 |

| L-Cysteine | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Soybean oil | 40.0 | 40.0 | 120.0 | 113.0 | 106.0 | 91.0 |

| Lard | 0.0 | 0.0 | 120.0 | 120.0 | 120.0 | 120.0 |

| Cellulose | 50.0 | 50.0 | 50.0 | 38.7 | 27.5 | 5.0 |

| Mineral Mix (AIN-93M-MIX) | 35.0 | 35.0 | 35.0 | 31.7 | 28.3 | 21.6 |

| Vitamin Mix (AIN-93M-MIX) | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 9.5 | 9.0 | 8.0 |

| Choline Bitartrate | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 |

| Tert-butylhydroquinone | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.008 |

| Rice bran | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 50.0 | 100.0 | 200.0 |

| Total | 1000.008 | 1000.008 | 1000.008 | 1000.400 | 1000.200 | 1000.400 |

| Gene Name | Primer sequence (5’-3’) | |

| Forward | Reverse | |

| GAPDH | AACGACCCCTTCATTGAC | TCCACGACATACTCAGCAC |

| GLUT4 | ATTGCAGCGCCTGAGTCTTT | GAGGGGGTTCCCCATCCTTA |

| MyoG | AGTGAATGCAACTCCCACAG | CTGGGAAGGCAACAGACATA |

| IGF-1 | CAATACAGCCAACGGGAAACAG | AACAAAGCTGGATGCCTGTCA |

| IRS-1 | CCGGATACCGATGGCTTCTC | CCGCCACTTCTTCTCGTTCT |

| PI3K | GGGAGCAGCCTGGATGATTT | AGCGATTGGTTCCCCACAAT |

| Akt | GCTTGCGGTCTGATGTTTTCT | GCCTTTTCCAGCCACAAACA |

| mTOR | CGTCACAATGCAGCCAACAA | TGCCTTTCACGTTCCTCTCC |

| S6K1 | ACACCCTCCATCCTGGAGTAA | TTGTTCACGATAAGTCTCCACCT |

| eIF-4EBP1 | TCACTAGCCCTACCAGCGAT | TTGTGACTCTTCACCGCCTG |

| FOXO1 | CGGAAAATCACCCCGGAGAA | TACACCAGGGAATGCACGTC |

| Atrogin-1 | AACCGGGAGGCCAGCTAAAGAACA | TGGGCCTACAGAACAGACAGTGC |

| MuRF-1 | CCTTGAGGGCCATTGACTTG | TCCCCTCAGAACTCAAGAGGAA |

| IL-6 | GTCCTTCCTACCCCAATTTCCA | TGGTCTTGGTCCTTAGCCAC |

| ZO-1 | GGCACATCAGCACGATTTCT | CCACAAAAGAAATCCTTTCACACCT |

| Occludin | ACTGGGTCAGGGAATATCCA | TCAGCAGCAGCCATGTACTC |

| GC program | Conditions |

| Injection location | Front |

| Injection volume | 1 μL |

| Solvent A washes | Ethyl acetate, 2 μL, 2 times pre-injection, 2 times post-injection |

| Sample washes | 2 μL, 2 times pre-injection |

| Sample pumps | 2 |

| Plunger speed | Slow |

| Inlet temperature | 200 °C |

| Inlet pressure | 16.288 psi |

| Inlet mode | Pulsed split |

| Split flow | 60 mL/min |

| Column flow | Constant flow |

| Post run | 1.2 mL/min (same as set point flow) |

| Capillary column | Nukol™ 30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm |

| Carrier gas type | Helium |

| Oven temperature | Initial: 90 °C |

| Ramp 1: rate 15 °C/min; value 150 °C; hold time 1 min | |

| Ramp 2: rate 3 °C/min; value 170 °C; hold time 2 min | |

| Ramp 3: rate 50 °C/min; value 200 °C; hold time 2 min | |

| Post run: 90 °C | |

| AUX heaters | 200 °C |

| Nutrient Contents | 100 g |

|---|---|

| Energy (kcal) | 418.7 |

| Protein (g) | 14.1 |

| Fat (g) | 14.3 |

| Carbohydrate (g) | 58.4 |

| Soluble fiber (g) | 1.6 |

| Insoluble fiber (g) | 20.9 |

| Sugars (g) | 5.2 |

| Sodium (mg) | 5.4 |

| Moisture (g) | 6.5 |

| Ash (g) | 6.7 |

| Amino Acids | mg/kg |

|---|---|

| Alanine | 7870 |

| Arginine | 9678 |

| Aspartic acid | 13452 |

| Cystine | 1582 |

| Glutamic acid | 18758 |

| Glycine | 6318 |

| Histidine | 4374 |

| Isoleucine | 5133 |

| Leucine | 9016 |

| Lysine | 5935 |

| Methionine | 1662 |

| Phenylalanine | 5815 |

| Proline | 6560 |

| Serine | 5557 |

| Threonine | 4743 |

| Tyrosine | 2557 |

| Valine | 7389 |

| Tryptophan | 1540 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.