1. Introduction

Hybrid resins are typically formulated through the association of an organic moiety with an inorganic counterpart. It should be underlined that the predominant research and formulation practices concerning these materials have traditionally been linked to the coatings and decorative finishes industry (see references [

1,

2,

3,

4] for details). Since evidence indicates that natural resins alone are unable to produce highly viscous systems, the available literature suggests that the bio-resins reported thus far should, in fact, be regarded as hybrid resins (see references [

1,

2,

4] for details). Therefore, subsequent sections detail research from the specialized literature concerning types of hybrid resins with a natural organic component.

One of the earliest studies on the synthesis of a hybrid resin was reported in [

5], where a bio-oil-derived epoxy resin was obtained from PEG/glycerin-liquefied Picea abies wood powder.

Abies alba (European silver fir) and

Picea abies (Norway spruce) are phylogenetically related members of the Pinaceae family. The starting material consisted of Picea abies wood particles with a size range of 20–80 mesh. The epoxy formulations were subsequently cured using a stoichiometric ratio of polyamide amine hardener. This hybrid resin can be regarded as originating from the same botanical source as that employed in the present investigation, namely Picea abies, although the current work makes use of its natural resin rather than wood biomass. Subsequent investigations focused on the utilization of Picea abies wood particles as a sustainable additive in phenol–formaldehyde resins for particleboard adhesives, aiming to reduce formaldehyde emissions while partially replacing conventional synthetic resins [

6]. In this approach, spruce wood was milled, dried, and liquefied in glycerol under sulfuric acid catalysis at 150 °C for 120 min, employing five different wood-to-solvent ratios ranging from 1:1 to 1:5. Another study related to the liquefaction of lignocellulosic biomass and its applications (for instance in the synthesis of polyurethanes or other polymeric materials) was presented in [

7]. That work discussed general concepts of lignocellulosic biomass (wood, residues, sawdust, etc.), liquefaction processes, and subsequent applications.

Rosin is a resin comparable to

Abies alba exudate, as it likewise originates from coniferous species. The similarity lies in their chemical composition, which in both cases is dominated by diterpenic acids, such as abietic- and maleopimaric-type derivatives. Reference [

8] provides an extensive overview of rosin and its relevance to epoxy resin systems. Rosin, together with its derivatives—most notably maleopimaric and abietic acids—can undergo chemical modification to yield epoxy-functional compounds. The study highlights that rosin-based derivatives bearing epoxy, acrylic, or anhydride groups hold considerable potential as bio-derived epoxy monomers, as cross-linking agents applicable to both petroleum-based and bio-based epoxy matrices, and as constituents of hybrid resins with adjustable mechanical and thermal performance. Another study employing rosin resin in powdered form as a bio-based epoxy matrix is reported in [

9]. In this work, rosin powder was incorporated at 1, 3, and 5 wt.% into a conventional epoxy system (MGS L285 + H 287). The powder was ground, sieved, and subsequently dispersed using three different methods: magnetic stirring, ultrasonic stirring, and a combined approach. The results demonstrated that the addition of 1 wt.% rosin led to notable improvements in mechanical performance, with tensile strength increasing by 5.63%, hardness by 14.41%, and compressive strength by 8.28% compared to neat epoxy. At higher loadings (3–5 wt.%), however, tensile strength and hardness values decreased, most likely due to particle agglomeration effects. In [

10], bio-based protective coatings for wood were investigated with the aim of enhancing its thermal, anti-fungal, chemical, and adhesion properties. The system employed consisted of diglycidyl ether of bisphenol A (DGEBA), three epoxidized oils (soybean, grapeseed, and corn), and maleopimaric acid (MPA)—a rosin-derived crosslinking agent. The study demonstrated that all coatings significantly improved the antifungal resistance of wood compared to the untreated samples, by reducing both mass loss and water uptake. SEM micrographs further confirmed that the coatings effectively blocked fungal penetration into the wood structure.

Chios mastic (Pistacia lentiscus) is a resin related to

Abies alba exudate. Mastic is a vegetal oleoresin gum obtained through natural exudation, similar to Abies alba. In [

11], the epoxidation of the polymeric fraction of mastic (natural gum) was investigated, leading to the production of self-curable epoxy adhesives. The authors also developed composite adhesives (reinforced with olive stone powder or cotton flakes) and evaluated the shear strength of the resulting joints. Studies have reported epoxy/unsaturated polyester (UP) composites filled with particles of “African elemi” (

Canarium schweinfurthii), including thermogravimetric analyses and mechanical property evaluations—representing a pathway for the valorization of non-coniferous oleoresins in polymer systems [

12]. From a chemical perspective,

African elemi is related to

Abies alba. The chemical composition is dominated by terpenoids and resin acids (abietic/pimaric types in Abies alba and triterpenic + diterpenic types in Canarium). Both

Abies alba and

Canarium produce exudates containing hydrophobic compounds with reactive groups (carboxylic, double bonds, polycyclic structures), which can undergo similar reactions such as epoxidation, esterification, and anhydridation [

13,

14].

Another exudate is peach gum, which, however, exhibits a different chemical composition compared to Abies alba. It is a polysaccharidic exudate (rather than diterpenic, as in

Abies), with a nature more closely related to plant gums such as tragacanth. In [

15,

16], fully bio-based epoxy vitrimers derived from peach gum were investigated, showing mechanical and thermo-mechanical properties comparable to petroleum-based epoxies. Other studies have reported polyimine networks obtained from peach gum, characterized by high strength and recyclability [

17].

Shellac, produced by insects (

Laccifer lacca), is also a natural resin. Although its chemical composition differs from that of Abies alba exudate (being characterized by esters and polycarboxylic acids), shellac–epoxy blends have been reported for coatings and even glass fiber–reinforced composites, in which maleated shellac was used as a reactive agent or network component. Several examples in this context are provided in references [

18,

19,

20].

A natural plant resin that has been employed as a bio-based component in hybrid matrices is dammar. Relevant examples are provided in studies [

21,

22], where hybrid matrices containing 50–70% dammar combined with agricultural residues (corn husk, pine needles, and recycled paper) were investigated. Composite materials were fabricated, and it was found that increasing the dammar content resulted in reduced stiffness and strength, while enhancing elasticity. Both resins (dammar and Abies alba exudate) are hydrophobic vegetal oleoresins containing polycyclic compounds and reactive groups (carboxylic functions, double bonds). Both can undergo epoxidation or esterification to be converted into hybrid matrices. Abies alba is dominated by diterpenoids (C20), particularly abietane and pimaranic acids, whereas dammar is dominated by triterpenoids (C30), which are bulkier and structurally different, yet still reactive.

Sandarac is a hard conifer resin composed of diterpenoids and sesquiterpenes. It exhibits properties comparable to rosin and Abies resins, and recent research has shown that it can be used in combination with epoxy resin for the fabrication of composite materials. An illustrative example is provided in reference [

23], where comparisons were made between composites with hybrid matrices based on dammar and those based on sandarac, the latter exhibiting inferior properties.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study reporting the use of

Abies Alba exudate resin as a precursor for hybrid resins designed to function as matrices in composite materials. While rosin derivatives and dammar resins have been widely explored in epoxy systems, the direct valorization of spruce resin for hybrid matrix development and its application in fiber-reinforced composites has not yet been addressed in the literature. An example of this is reference [

24], which addresses this topic. It is important to clarify that in the present work the hybrid matrices are interpreted as physically combined systems, and the focus of the study is placed on their mechanical, dynamic and moisture absorption behavior, as well as on their applicability as matrices for natural fibre-reinforced composites.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

In the present research, natural

Abies alba exudate resin from the Baia de Fier area, Gorj County, Romania, was used. The resin was collected directly from the trees and employed without any prior chemical treatment. To bring the resin into a liquid state, two methods were applied: in the first method, the resin was diluted with turpentine obtained from pine buds, while in the second method, it was diluted with pure food-grade alcohol (96°). Both the turpentine and the pure alcohol were purchased from local vendors ([

25,

26]). The resin was left with the alcohol and turpentine in hermetically sealed glass containers until it reached a liquid state.

It is well known that these resins, if left in containers, do not undergo polymerization and, consequently, cannot be used in the manufacture of solid materials. Therefore, in order to polymerize and reach a solid state, this natural resin was combined with synthetic resin and its corresponding hardener. The proportions used in the present study were 50%

Abies alba exudate resin and 50% epoxy resin Resoltech 1050 together with its corresponding hardener, Resoltech 1055. The epoxy resin was also purchased from a local manufacturer [

27]. The combination of epoxy resin Resoltech 1050 and hardener Resoltech 1055 was carried out in accordance with the manufacturer’s recommendations [

28]. According to the technical datasheet, the Resoltech 1050/1055 system is a Bisphenol-A based epoxy resin with an epoxy equivalent weight of 305–335 g/eq, a viscosity of 900–1200 mPa·s at 20 °C and a recommended mixing ratio of 100:35 (A:B), suitable for room-temperature curing. No chemical pretreatment or functionalization of the Abies alba exudate was performed prior to blending, and no catalysts were added; therefore, the natural resin was used as a bio-based matrix modifier within a physically hybridized epoxy network. To demonstrate the applicability of the obtained hybrid resins in the manufacture of composite materials, they were ultimately used to fabricate specimens reinforced with cotton fabric, with the previously mentioned hybrid resins serving as matrices. The cotton fabric was purchased from a local manufacturer and is characterized by an areal density of 130 g/m² [

29].

2.2. Fabrication Method

In this work, the hand lay-up technique was employed both for the preparation of the hybrid matrices and for the fabrication of the final composite materials. In the first stage, the fabrication of the hybrid matrices was carried out as follows: in a bowl, 50% of component A (characterized by natural Abies alba exudate resin, dissolved in turpentine) was mixed with 50% of component B (characterized by synthetic epoxy resin Resoltech 1050 with hardener Resoltech 1055). This mixture was designated as Hybrid Resin 1 (abbreviated HR1). The two components were stirred in the bowl for homogenization for 60 seconds. The mixture was then poured into a frame placed on a base plate. A top plate was positioned over the frame, and weights were subsequently placed on top of the upper plate to press the content. A uniform pressure of 27 kN/m² was applied.

In a similar manner, the second hybrid resin, abbreviated as HR2, was prepared. This hybrid resin was characterized by a composition of 50% component A (natural Abies alba exudate resin dissolved in 96° food-grade alcohol) and 50% component B (synthetic epoxy resin Resoltech 1050 with hardener Resoltech 1055). The mixing time and casting procedure were identical to those described previously for HR1.

The flow diagram of the manufacturing method described above is presented in Figure 1. It was included to clarify the procedure for obtaining the two resins. For the case of composite materials reinforced with cotton fabric and hybrid resin HR1, the following procedure was applied: a cotton fabric layer was placed on a base plate, onto which the HR1 matrix was applied; a second cotton fabric layer was then positioned on top of the first and impregnated with HR1 resin. This procedure was repeated for an additional ten layers, resulting in a total of twelve cotton fabric layers. A top plate was placed over the final layer, and a uniform pressure of 27 kN/m² was applied once again.

For all the materials studied (the two hybrid resins separately and the composite material reinforced with cotton fabric), the mold was removed after 7 days.

Figure 2.

(a) The flow diagram for obtaining the studied materials; (b) The hybrid resin cast into a mold with a frame configuration.

Figure 2.

(a) The flow diagram for obtaining the studied materials; (b) The hybrid resin cast into a mold with a frame configuration.

An example of a plate removed from the mold is shown in

Figure 3a, while

Figure 3b illustrates that, although the hybrid resin is based on the same material – Abies alba exudate – its behavior differs depending on the dissolution method: when the resin is dissolved in turpentine, it polymerizes into a solid final product; when dissolved in 96° food-grade alcohol, it polymerizes into an elastic final product (with a behavior and texture similar to rubber).

2.3. Tensile Test

Tensile specimens were manufactured from plates prepared with the two hybrid resins, HR1 and HR2, in their neat form, as well as from a plate in which HR1 served as the matrix and cotton fabric acted as the reinforcement. Each plate provided ten samples for testing. The experimental procedure followed the ASTM D3039/D3039M-08 guideline, employing specimens with dimensions of 250 × 25 × 8 mm. Testing was performed on a universal testing system produced by Laryee (Beijing, China) with maximum force of 10 kN, with data acquisition handled through the Evo Test software package. According to ASTM D3039/D3039M-08 [

30], a set of 10 valid specimens is considered sufficient to obtain statistically meaningful results; moreover, the standard specifies a minimum of 5 specimens, without indicating a maximum number of tests. In cases where large discrepancies between values occur, those results should be discarded and the test repeated. On the obtained data, the Dixon test will be applied to identify and eliminate potential outliers from the experimental dataset. Several examples of specimens used in the tensile test are presented in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5.

2.4. Compression Test

To evaluate the compressive strength, composite plates with a configuration analogous to those prepared for tensile characterization were fabricated. From these plates, specimens with nominal dimensions of 25.4 mm × 12.7 mm × 12.7 mm were extracted. The tests were carried out in compliance with ASTM D695-23 [

31], employing a Laryee universal testing machine (Beijing, China) with a maximum capacity of 10 kN and fitted with a specialized compression fixture. The relatively small specimen geometry was deliberately adopted to ensure failure occurred predominantly through compressive crushing, thereby preventing premature instability associated with buckling phenomena. A total of ten specimens were tested for each material type manufactured with the hybrid resins HR1 and HR2. Several examples of specimens used in the compression test are presented in

Figure 6.

2.5. Bending Test

For the evaluation of flexural strength, composite plates similar to those prepared for tensile testing were fabricated, employing the two hybrid resins HR1 and HR2. In addition, composite plates reinforced with cotton fabric and an HR1 matrix were produced. From each plate, ten specimens with nominal dimensions of 250 mm in length, 12 mm in width, and 10 mm in thickness were precisely cut. The bending experiments were conducted on a Laryee universal testing machine (Beijing, China) equipped with a three-point flexural fixture, in compliance with the ASTM D790-17 standard [

32].

2.6. Vibrations Test

The specimens used for the vibration evaluation maintained the same geometry and characteristics as those described in the tensile testing procedure. Each specimen was clamped at one end, while the opposite free end was instrumented with a Brüel & Kjær accelerometer (sensitivity: 0.04 pC/ms²). The accelerometer was connected to a Nexus conditioning amplifier, which transmitted the signal to a SPIDER 8 data acquisition system (HBK Hottinger Brüel & Kjær, Darmstadt, Germany). The SPIDER 8 module was subsequently interfaced with a laptop, where the experimental data were recorded and stored for subsequent processing.

2.7. Shore D Hardness Test

The Shore D hardness measurements were performed in accordance with the ASTM D2240-15 standard [

33]. Test specimens with the same dimensions as those used for tensile testing were employed. For each specimen, five hardness values were recorded at 50 mm intervals, with the first and last measurements positioned 25 mm from the respective ends. All indentations were taken along the midline of the specimen width to ensure consistency and comparability of the results.

2.8. Water Absorption Test

Water absorption measurements were performed in accordance with the standardized ASTM D570 [

34] test method. The specimens were initially dried and weighed, after which they were fully immersed in distilled water contained in Berzelius beakers. All samples had nominal dimensions of 76.2 mm × 25.4 mm × 8 mm. After 24 h of immersion, the specimens were removed from the water, the surface moisture was carefully eliminated using a dry cloth, and the mass was measured using a SHIMADZU analytical balance (Kyoto, Japan) with a precision of 0.01 g.

2.9. Breaking Section Analysis with Microscopy

The fracture section was analyzed using optical microscopy. A Digital Microscope Keyence VHX-X1F Series (Osaka, Japan) was used.

3. Results

For each type of testing/investigation, the experimental results and the main ideas derived from their preliminary analysis were presented.

3.1. Tensile Test

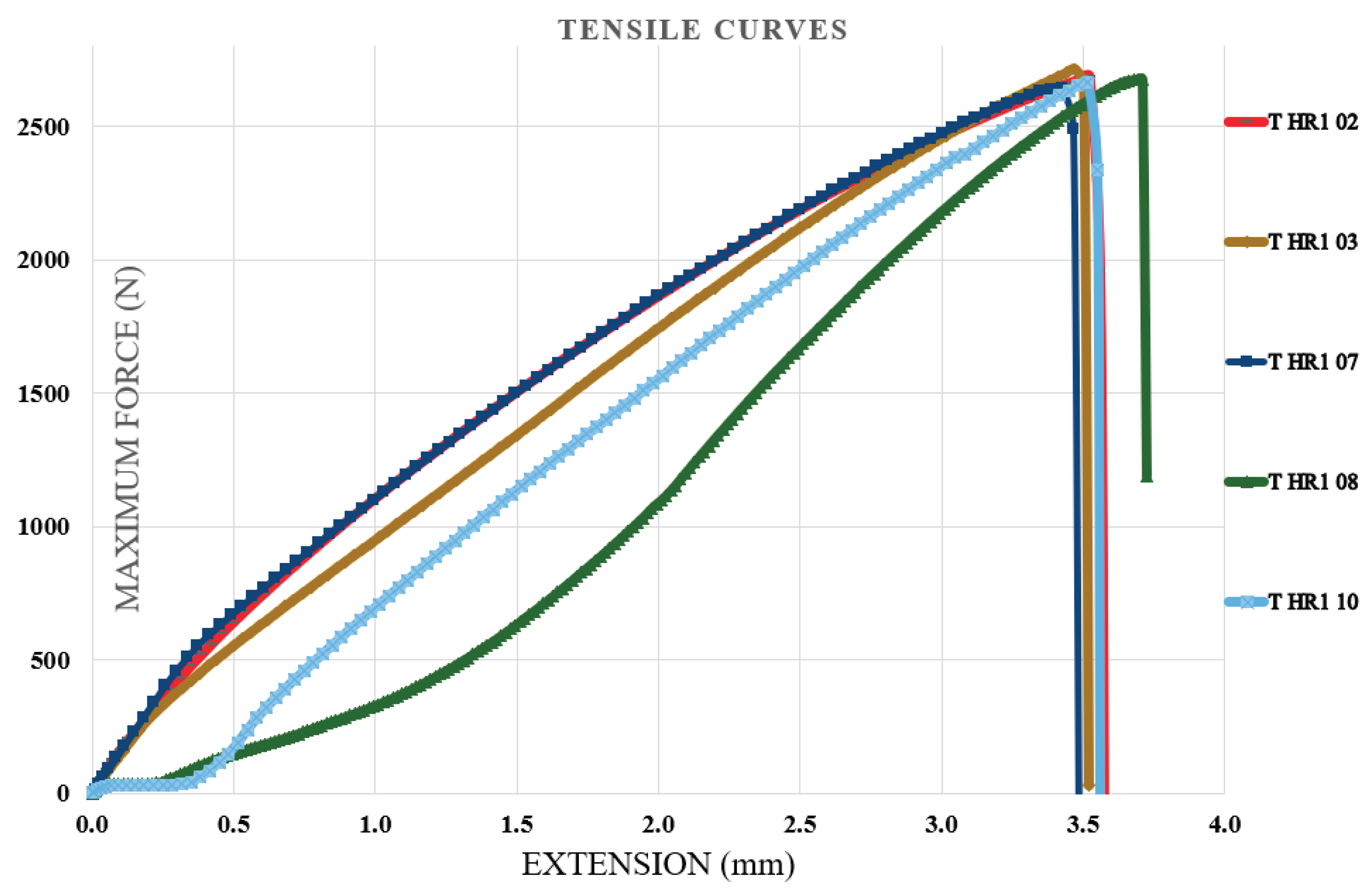

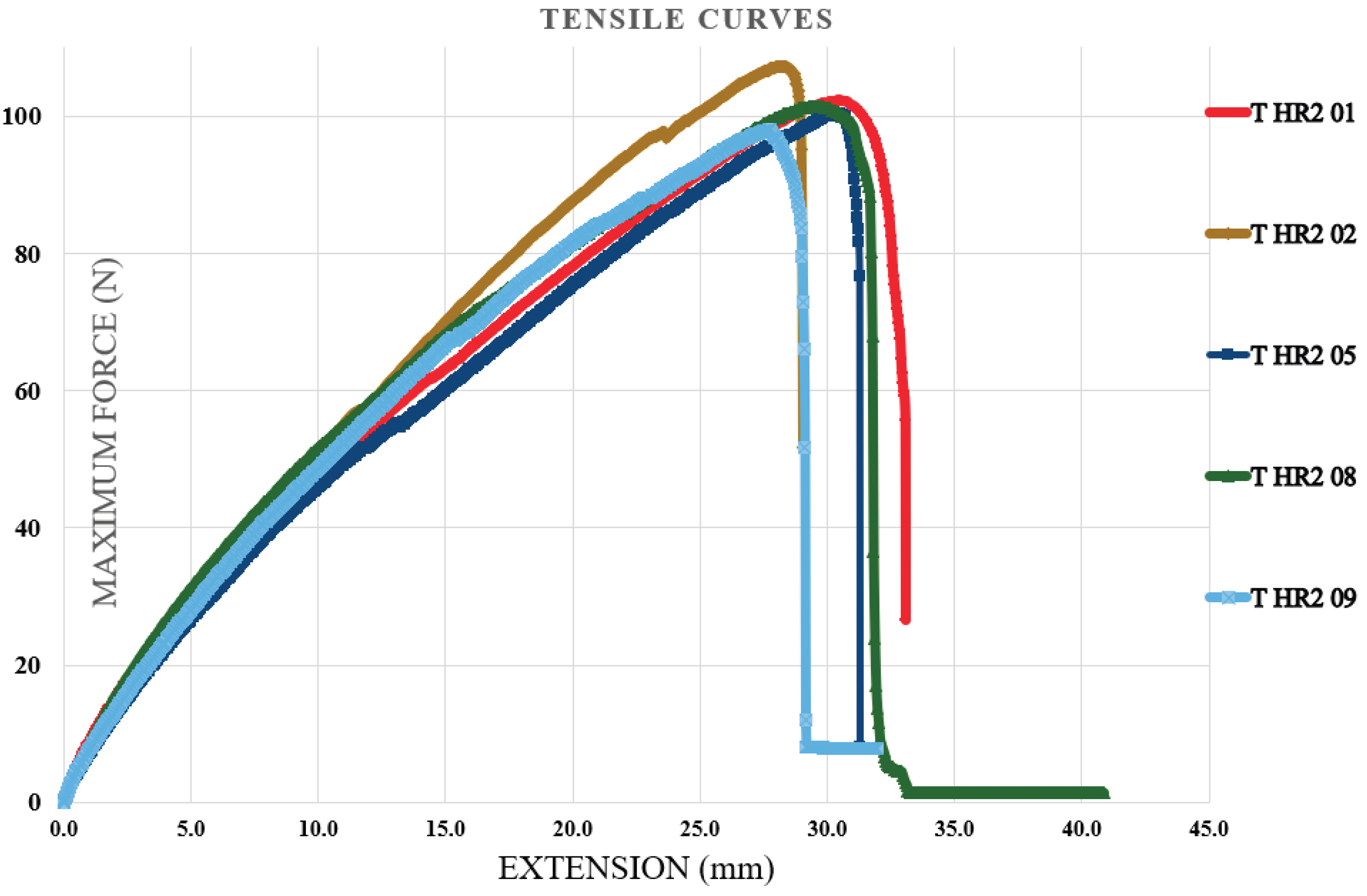

Tensile tests will be performed on specimens containing the first type of hybrid resin, followed by specimens containing the second type of hybrid resin. The specimen coding will include the letter T (from tensile test), the type of hybrid resin (HR1 or HR2), and finally, the specimen number within the set of 10 samples. Five representative characteristic curves from each set of 10 specimens will be presented.

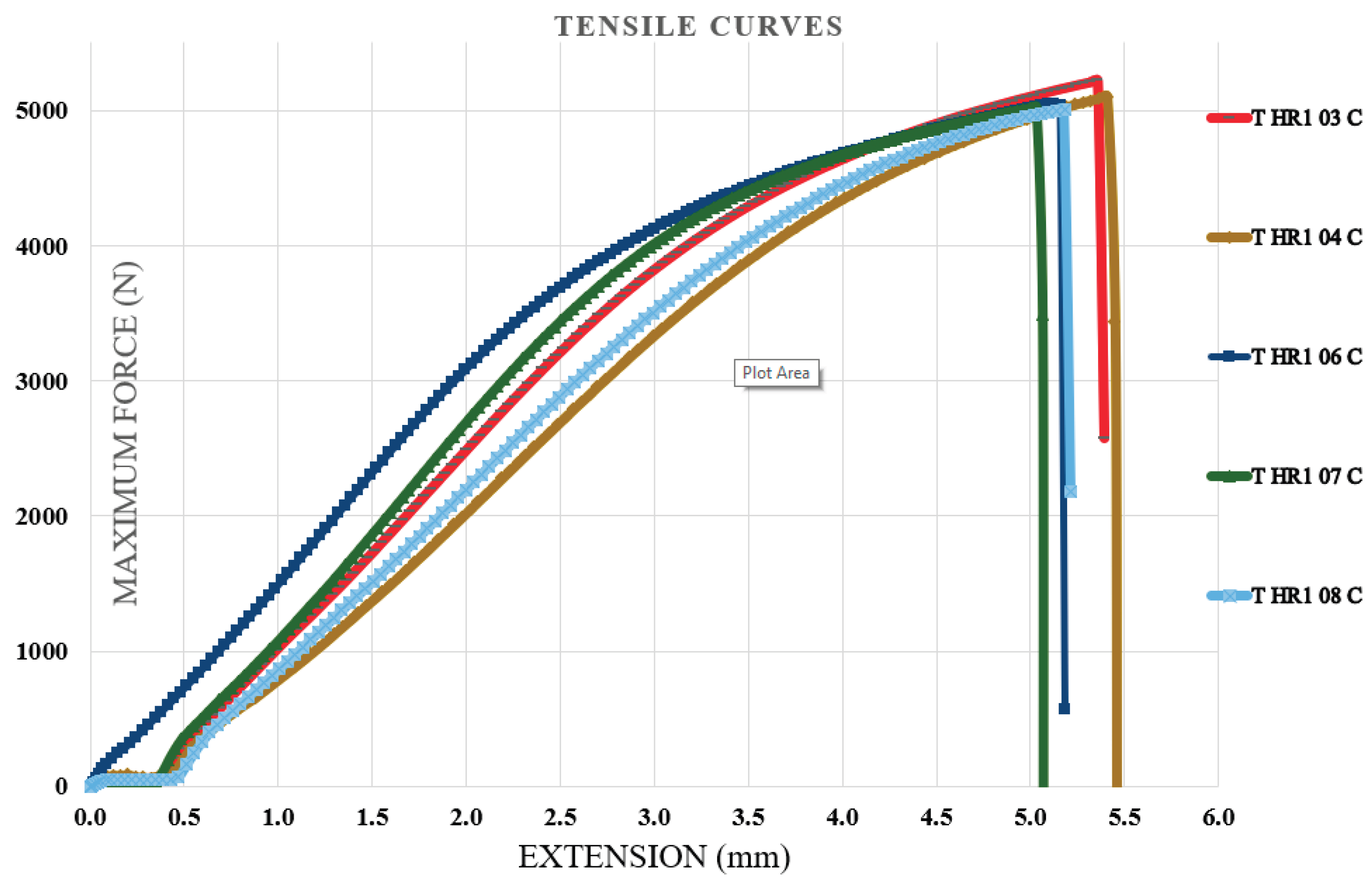

Figure 7 shows the characteristic curves for five representative specimens made of the HR1 resin, while

Figure 8 presents the characteristic curves for five representative specimens made of the HR2 resin. To demonstrate the applicability of the hybrid resins in the fabrication of composite materials, additional specimens were prepared using the HR1 hybrid resin reinforced with cotton fibers. From the set of 10 specimens, five representative characteristic curves were presented. In this case, the specimen notation includes the letter T (tensile test), the type of hybrid resin (HR1), the specimen number within the set of 10, and finally the letter C (cotton), indicating that this type of specimen contained reinforcement.

Figure 9 shows the characteristic curves for five representative specimens reinforced with cotton and HR1 resin.

From the analysis of the characteristic curves, it can be observed that for the specimens with HR1 resin (for which Abies alba exudate was dissolved in pine-bud turpentine), the maximum breaking forces ranged between 2684 and 2644 N, the tensile strengths between 13.2 and 13.5 MPa, and the elongations at break between 3.43 mm and 3.71 mm. From the analysis of the characteristic curves of the HR2 specimens (for which Abies alba exudate was dissolved in 96° food-grade ethyl alcohol), it was found that the maximum breaking forces ranged between 97.6 and 107 N, the tensile strengths between 0.48 and 0.53 MPa, and the elongations at break between 27.8 mm and 30.8 mm. From the analysis of the characteristic curves of the specimens with HR1 resin reinforced with cotton fiber, the maximum breaking forces ranged between 5005 and 5222 N, the tensile strengths between 25 and 26 MPa, and the elongations at break between 5.03 mm and 5.4 mm. In this regard, it can be stated that when Abies alba exudate is dissolved in pine-bud turpentine, the hybrid resin obtained by combining it with epoxy resin exhibits higher strength and lower elasticity compared with the case in which Abies alba exudate is dissolved in pure food-grade alcohol. Additionally, when reinforcement (cotton fiber) is added, the maximum breaking force and tensile strength increase by factors of 1.9 and 1.94, respectively, while the elongation at break increases by approximately 1.5 times.

3.2. Compression Test

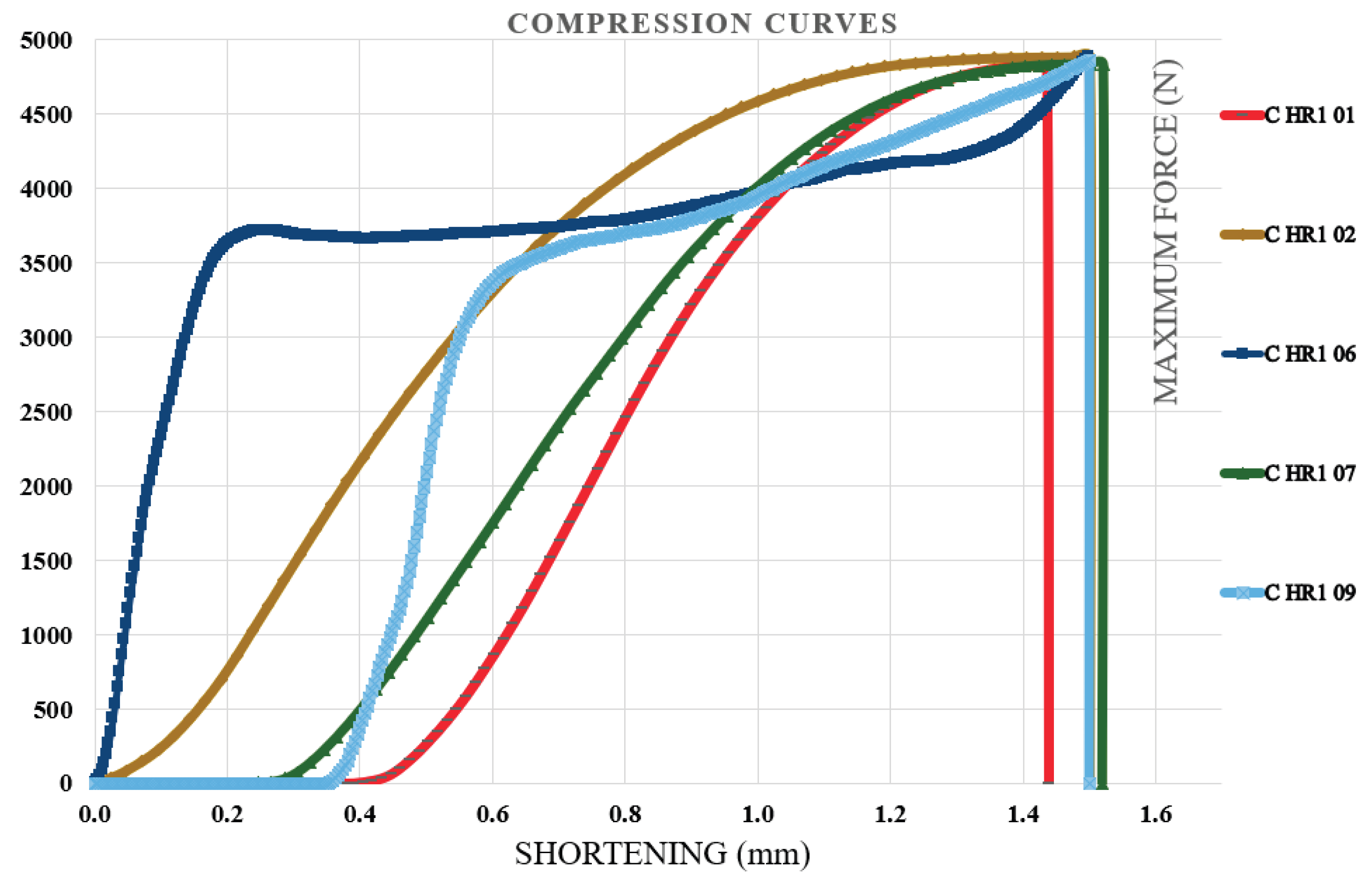

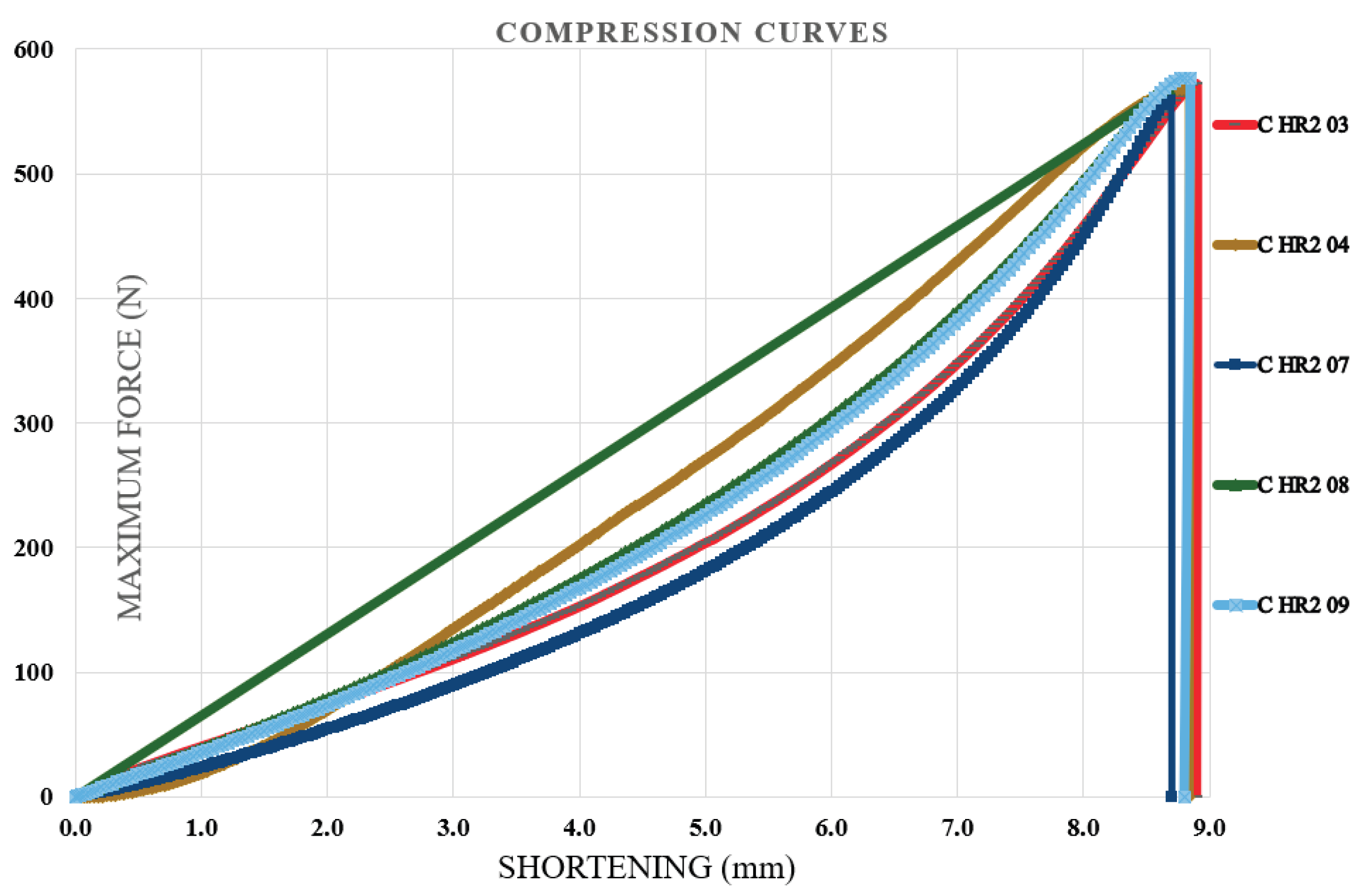

Compression tests will be carried out on specimens containing the first type of hybrid resin, followed by those made with the second type. Each specimen will be coded using the letter C (from compression), the hybrid resin type (HR1 or HR2), and the specimen number within the batch of ten samples. For each batch, five representative characteristic curves will be presented.

Figure 10 illustrates the characteristic curves for five representative specimens prepared with the HR1 resin, while

Figure 11 presents the corresponding curves for specimens made with the HR2 resin.

From the analysis of the characteristic curves, it was found that the specimens manufactured from the HR1 hybrid resin exhibited shortening at fracture between 1.44 and 1.52 mm, compressive breaking forces ranging from 4832 to 4894 N, and corresponding compressive strengths between 29.9 and 30.3 MPa. In contrast, the specimens produced from the HR2 resin showed considerably higher shortening at fracture values, between 8.6 and 8.9 mm, breaking forces ranging from 559 to 577.2 N, and compressive strengths in the range of 3.4 to 3.6 MPa.

3.3. Bending Test

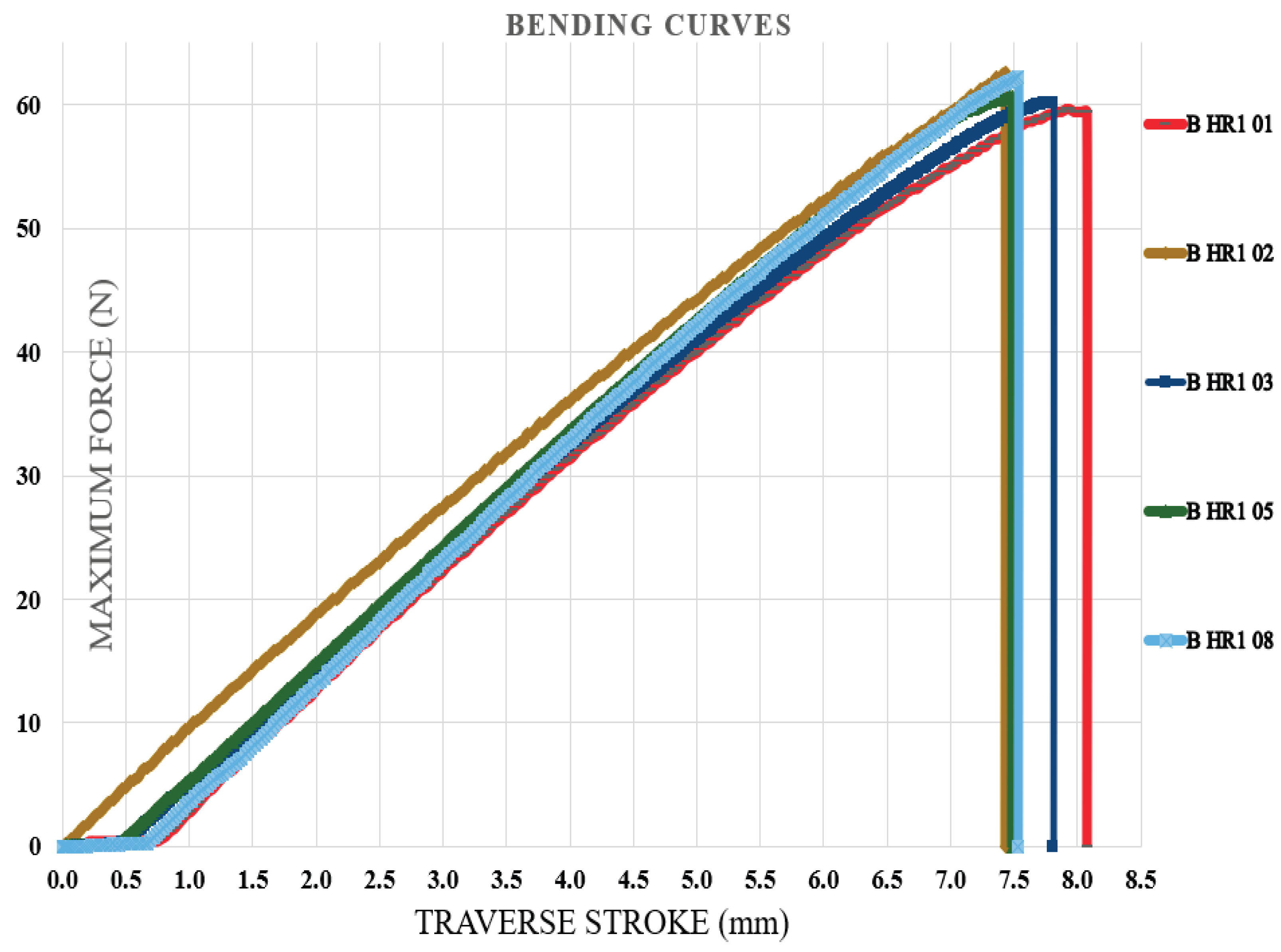

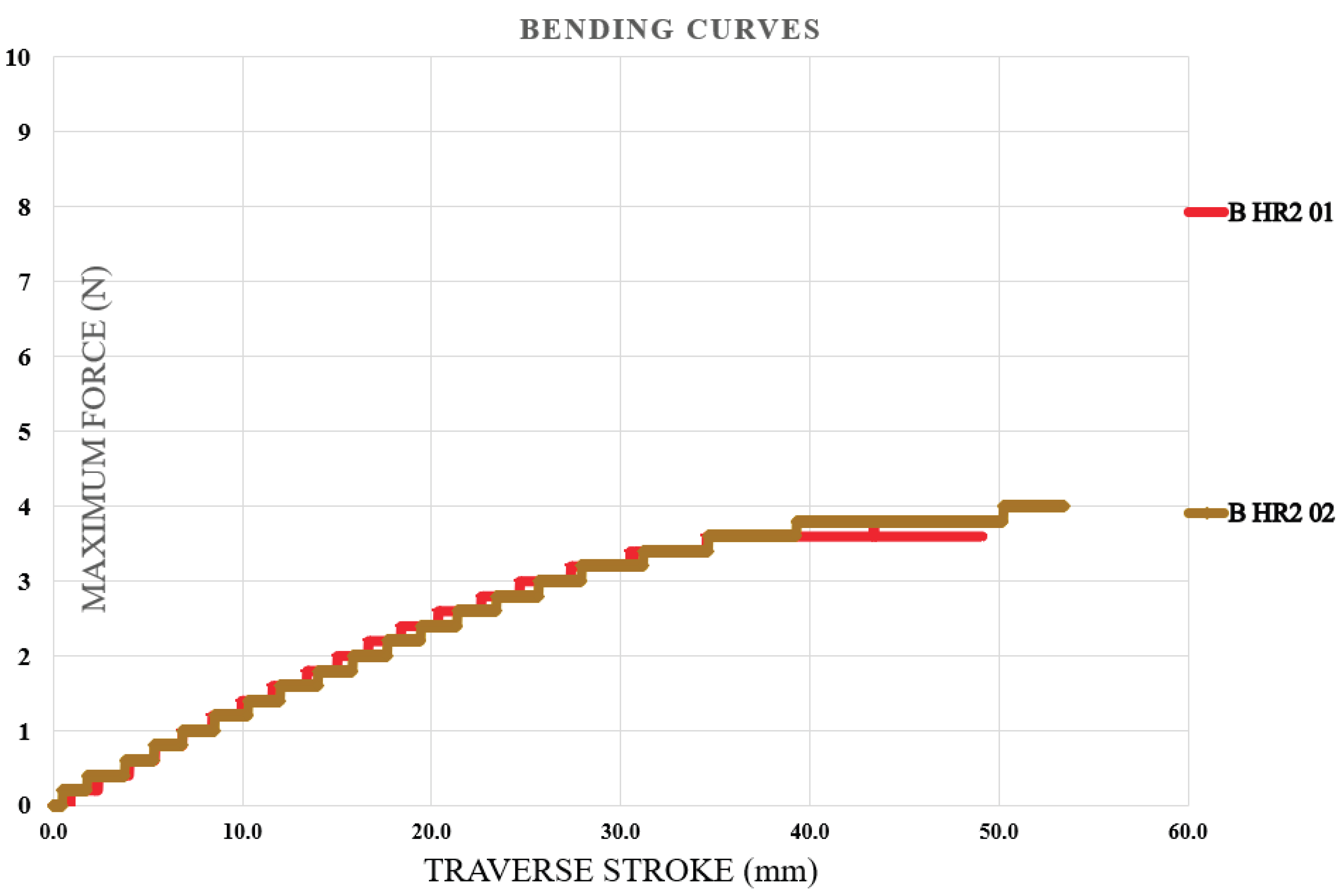

Bending tests were carried out first on specimens fabricated from the initial type of hybrid resin, followed by those produced using the second type. The specimen identification system comprised the letter B (from bending test), the hybrid resin type (HR1 or HR2), and the sequential specimen number within each series of ten samples. For clarity, five representative characteristic curves were selected from every set of ten specimens.

Figure 12 illustrates the characteristic curves obtained for five representative samples made from the HR1 resin, whereas

Figure 13 depicts the corresponding curves for specimens manufactured from the HR2 resin. To further confirm the suitability of the hybrid resins for composite manufacturing, an additional series of specimens was produced using the HR1 hybrid resin reinforced with cotton fibers. Out of the ten tested samples, five characteristic curves representative of the group were selected and presented. In this case, the specimen coding included the letter B (bending test), the hybrid resin designation (HR1), the specimen number, and the suffix C (cotton), indicating the presence of fiber reinforcement.

Figure 14 displays the characteristic curves for the five representative cotton-reinforced HR1 specimens.

From the analysis of the characteristic bending curves, it was observed that the specimens manufactured from the HR1 resin exhibited bending deformations (traverse stroke) between 7.4 and 7.8 mm, maximum bending forces ranging from 59.4 to 62.6 N, and corresponding flexural strengths between 14.8 and 15.6 MPa. For the specimens in which the matrix consisted of HR1 resin reinforced with cotton fibers, the bending deformations ranged between 11.5 and 12.55 mm, while the maximum breaking forces varied from 139.9 to 144.7 N, resulting in flexural strengths between 35 and 36.1 MPa. In contrast, for the specimens fabricated from the second hybrid resin (HR2), the bending test was interrupted after the second specimen because the sample reached the maximum traverse stroke without fracturing. After the moving crosshead was released, the specimen returned almost entirely to its initial shape, indicating a highly elastic behavior (see

Figure 15 and

Figure 16).

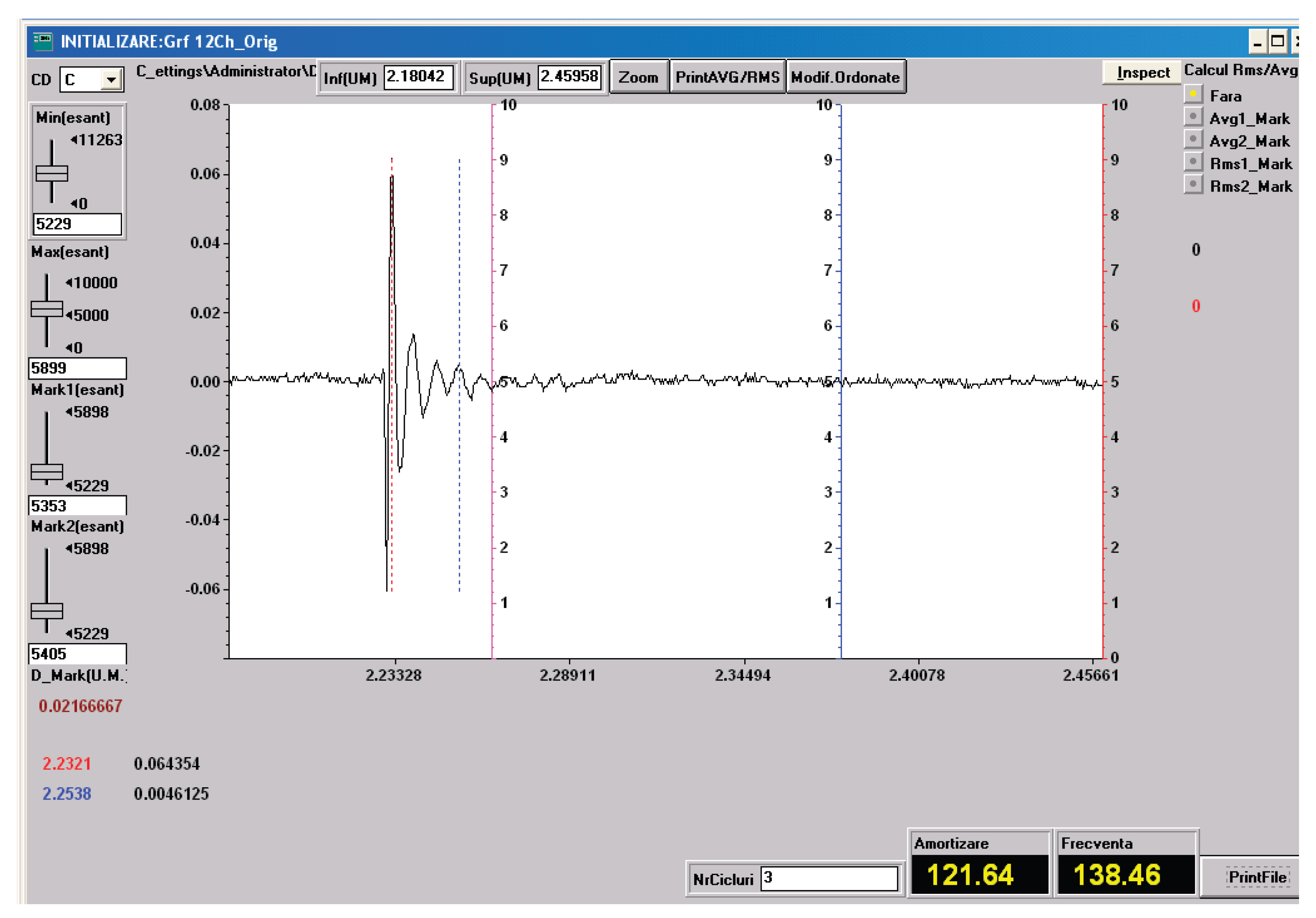

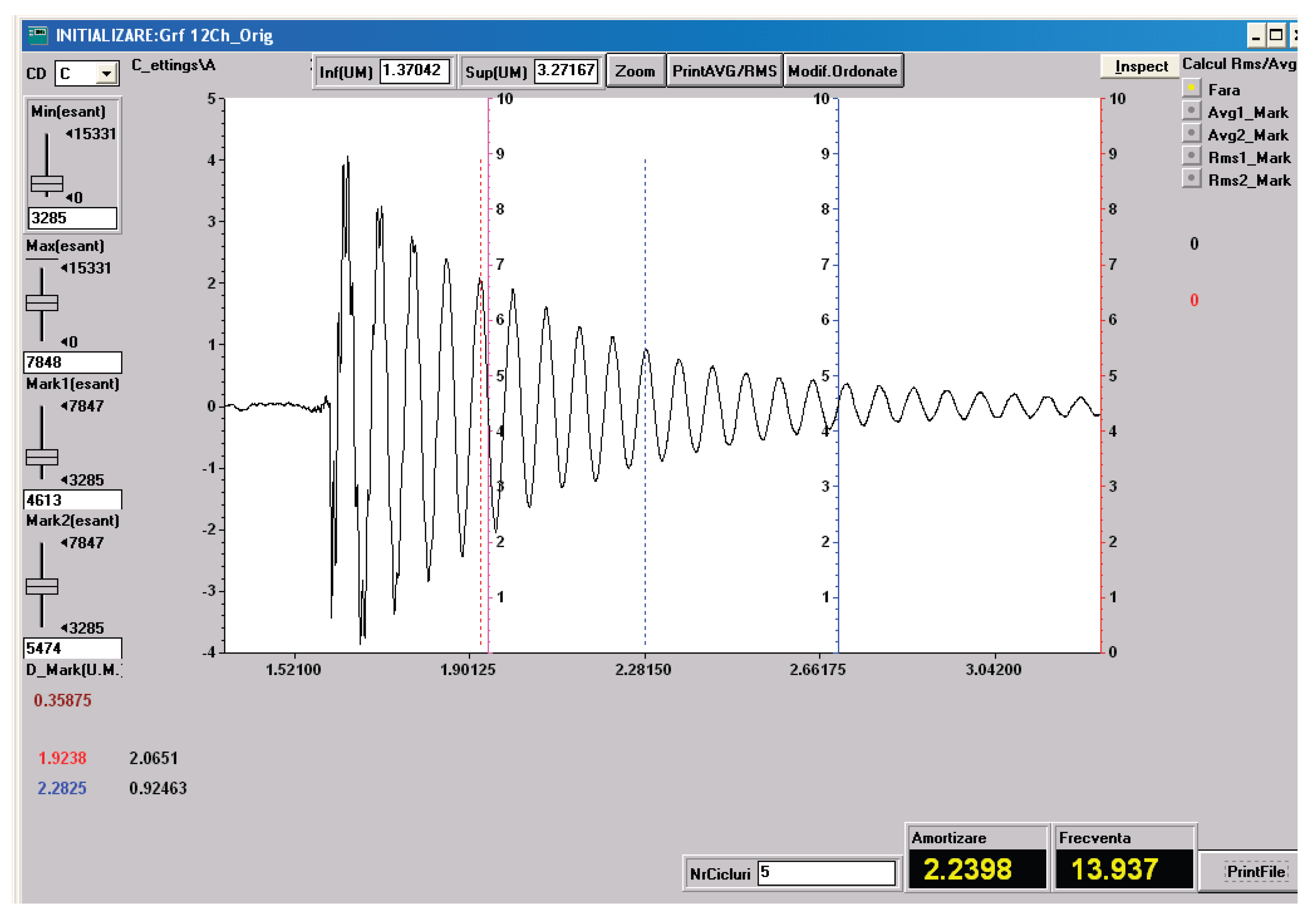

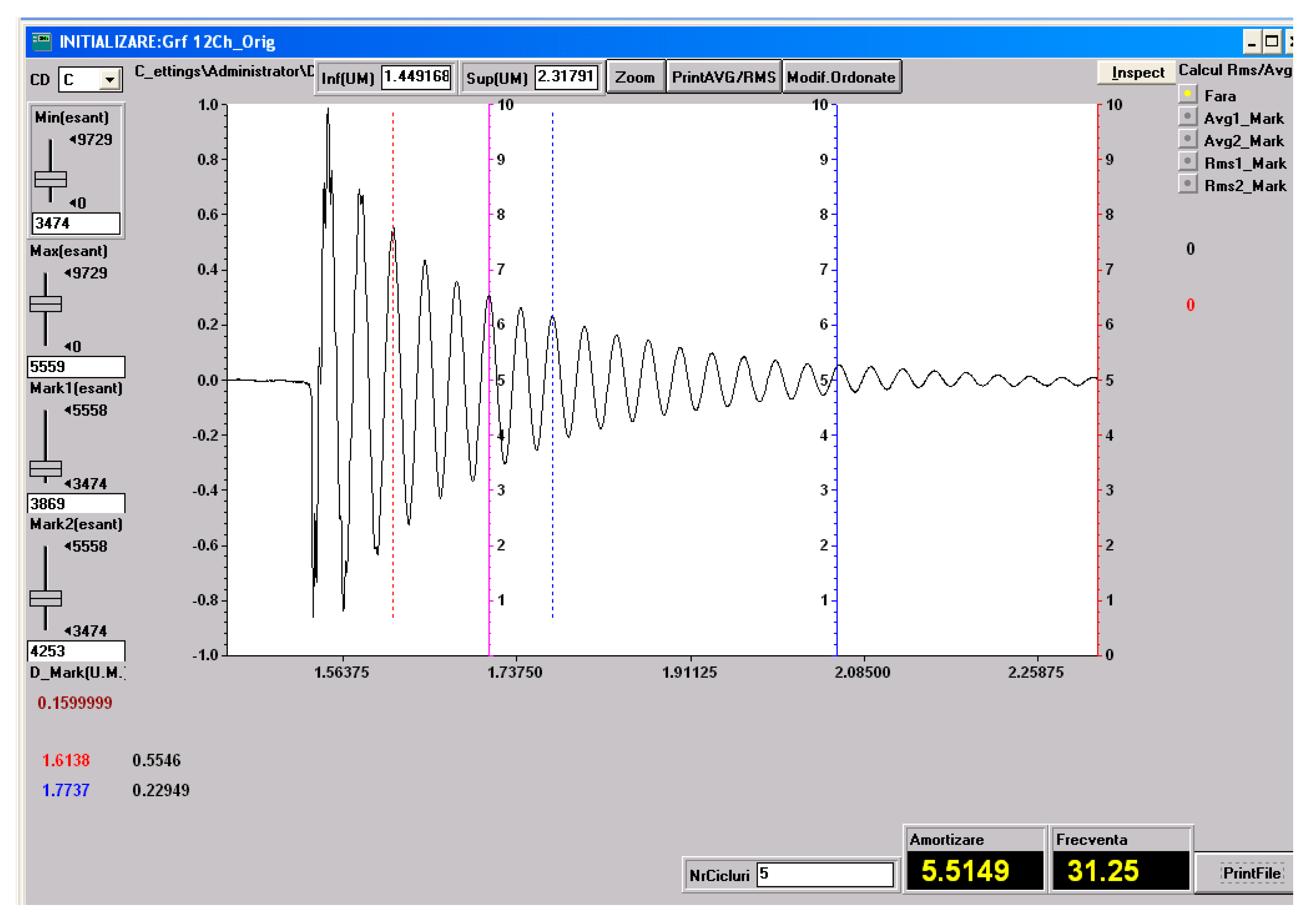

3.4. Vibrations Test

As specified in the

Materials and Methods section, free-vibration tests were performed on the three material configurations investigated in the present study: specimens made solely of the HR1 resin, specimens made solely of the HR2 resin, and specimens fabricated using the HR1 resin reinforced with cotton fiber. Based on the experimental setup employed, the damping factor was determined using Equation (1) [

22].

Equation (1) utilizes the time instants corresponding to two successive oscillation peaks, t1 and t2, together with their associated amplitudes v1 and v2, extracted from the amplitude–time response, to quantify the decay of oscillation amplitude over time.

The damped pulsation, the natural pulsation and the damping ratio can be determined with Eqs. (2-4) [

35].

In Eqs. (2–4)

ν denotes the natural frequency. In the following, one representative experimental recording, including the determination of the natural frequency and the damping factor, is presented for each type of material investigated. These recordings are shown in

Figure 17,

Figure 18 and

Figure 19.

All the vibration parameters calculated using Eqs. (2–4) are summarized in Table 1.

Table 2.

Vibration parameters.

Table 2.

Vibration parameters.

| Material |

ωd(rad/s)

|

ωn(rad/s)

|

ζ |

| HR1 |

87.56 |

87.59 |

0.026 |

| HR2 |

870.1 |

878.6 |

0.139 |

| HR1+cotton |

196.35 |

196.43 |

0.028 |

The dynamic vibration results are in very good agreement with the static mechanical behavior observed for the investigated materials. The HR1 resin, which exhibited higher stiffness and strength but limited deformation in tensile, compressive, and flexural tests, also showed a low damping ratio and a low natural frequency, characteristic of rigid polymeric systems. The cotton fabric–reinforced HR1 composite displayed an increased natural frequency due to the enhanced structural stiffness provided by the reinforcement, while the damping ratio remained at a similar level, indicating that the dynamic response was still governed by the matrix properties. In contrast, the HR2 resin, which demonstrated extremely high elongation and elastic recovery in static tests, exhibited a significantly higher damping ratio, confirming its pronounced viscoelastic nature.

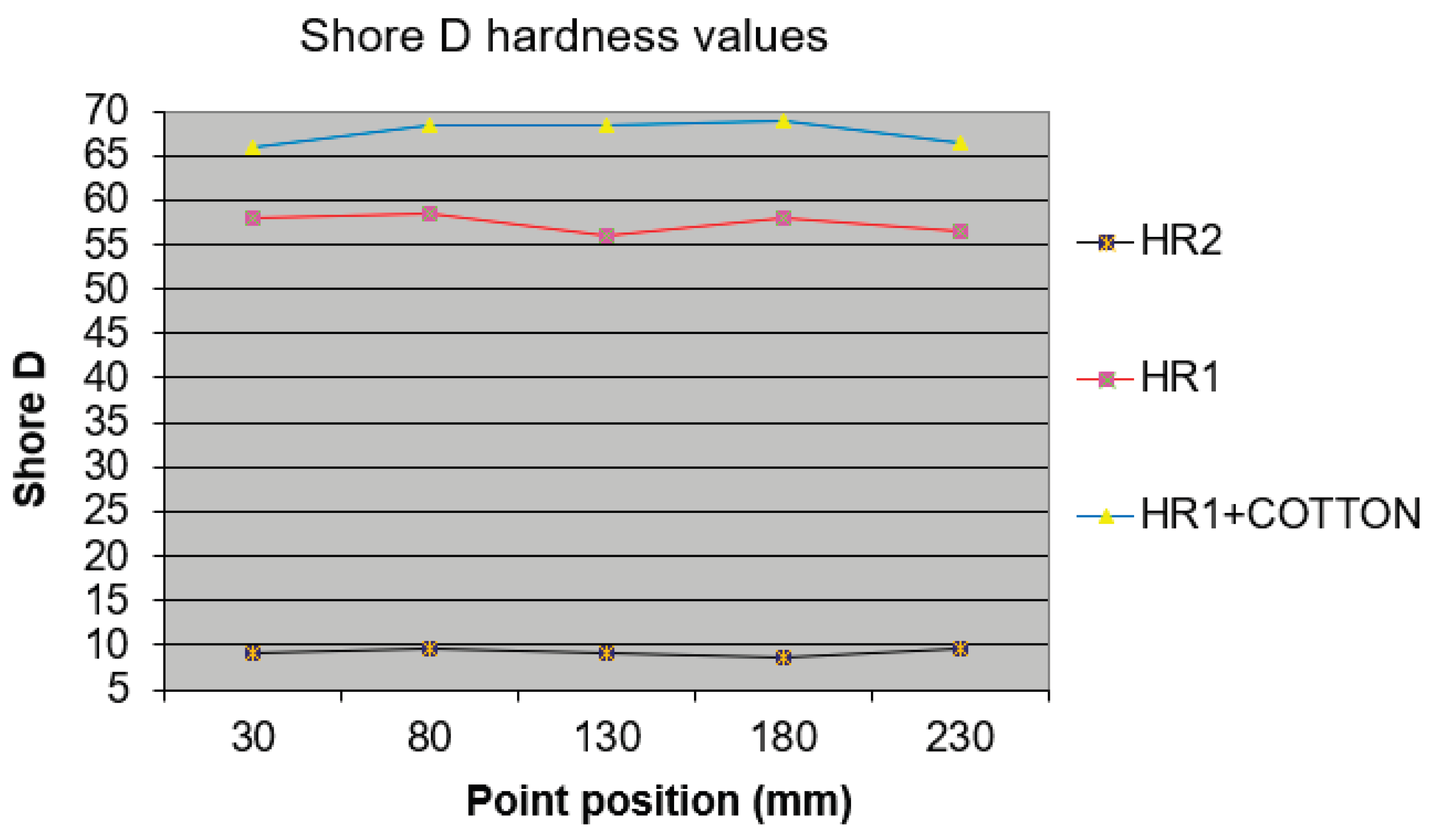

3.5. Shore D Hardness Test

Shore D hardness measurements were performed at five locations along the longitudinal symmetry axis of the specimens for each material type (HR1, HR2, and HR1 + cotton). The specimens had the same dimensions as those used in the tensile tests. The experimental data obtained are presented in

Figure 20.

The Shore D hardness measurements revealed a clear distinction between the three investigated material systems. The HR2 material exhibited very low hardness values, remaining below 10 Shore D along the entire specimen length, which is consistent with its highly elastic and viscoelastic behavior observed in static mechanical and vibration tests. In contrast, the HR1 resin showed significantly higher hardness values, approximately in the range of 56–58.5 Shore D, indicating a rigid polymeric matrix with limited elastic recovery. The highest hardness values were recorded for the cotton fabric–reinforced HR1 composite, which exhibited Shore D values close to 66–69, reflecting the combined stiffening effect of the rigid hybrid matrix and the textile reinforcement. Only minor variations in Shore D hardness were observed along the longitudinal direction for all materials.

3.6. Water Absorption Test

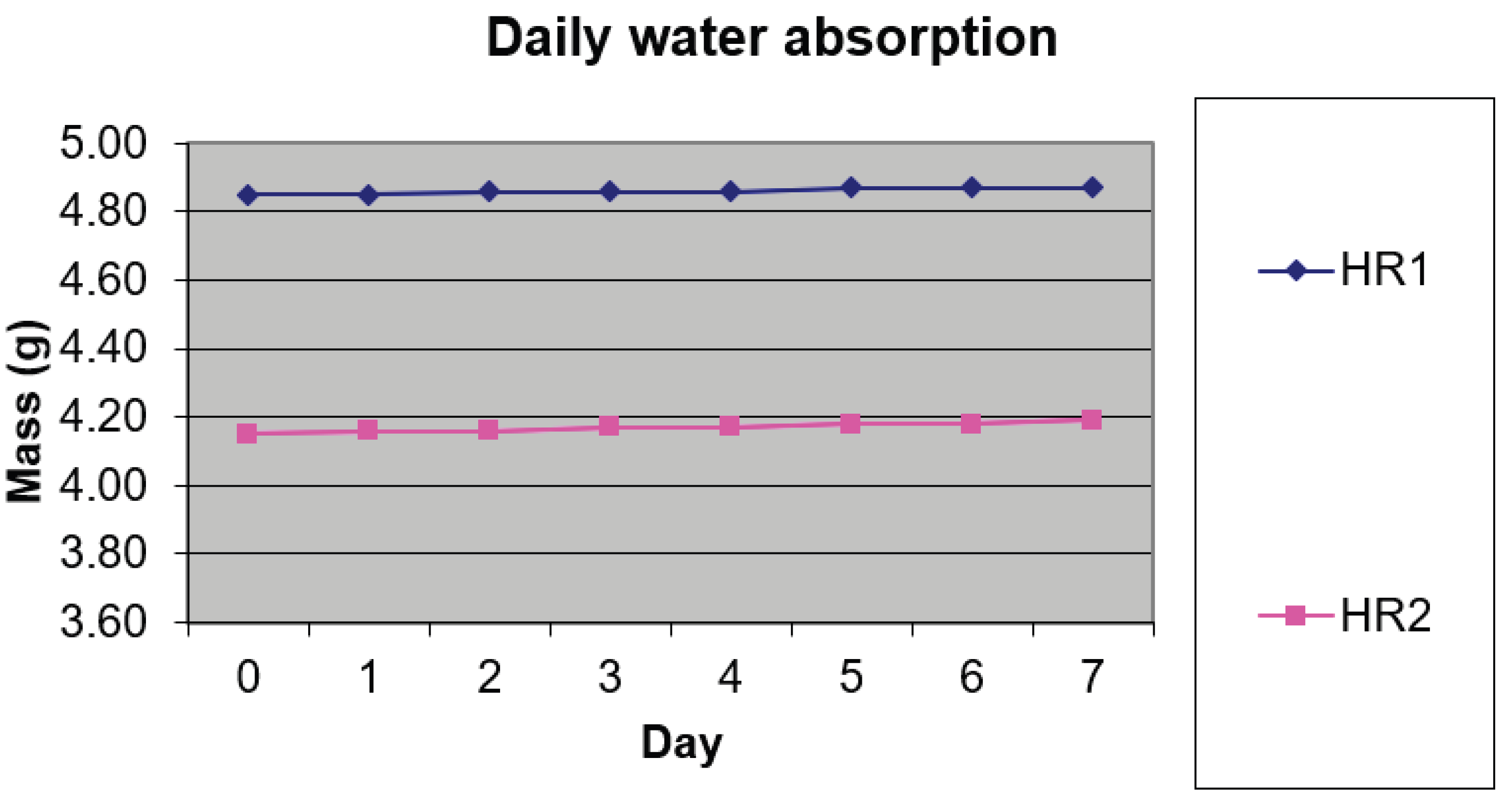

Figure 21 shows the experimental results related to the water absorption behavior of the investigated hybrid resins HR 1 and HR2 materials.

The water absorption of both hybrid resins was limited, with HR2 showing a slightly higher mass increase (0.04 g) compared to HR1 (0.03 g). This minor difference can be attributed to the more flexible and viscoelastic network of HR2, which may facilitate limited water diffusion.

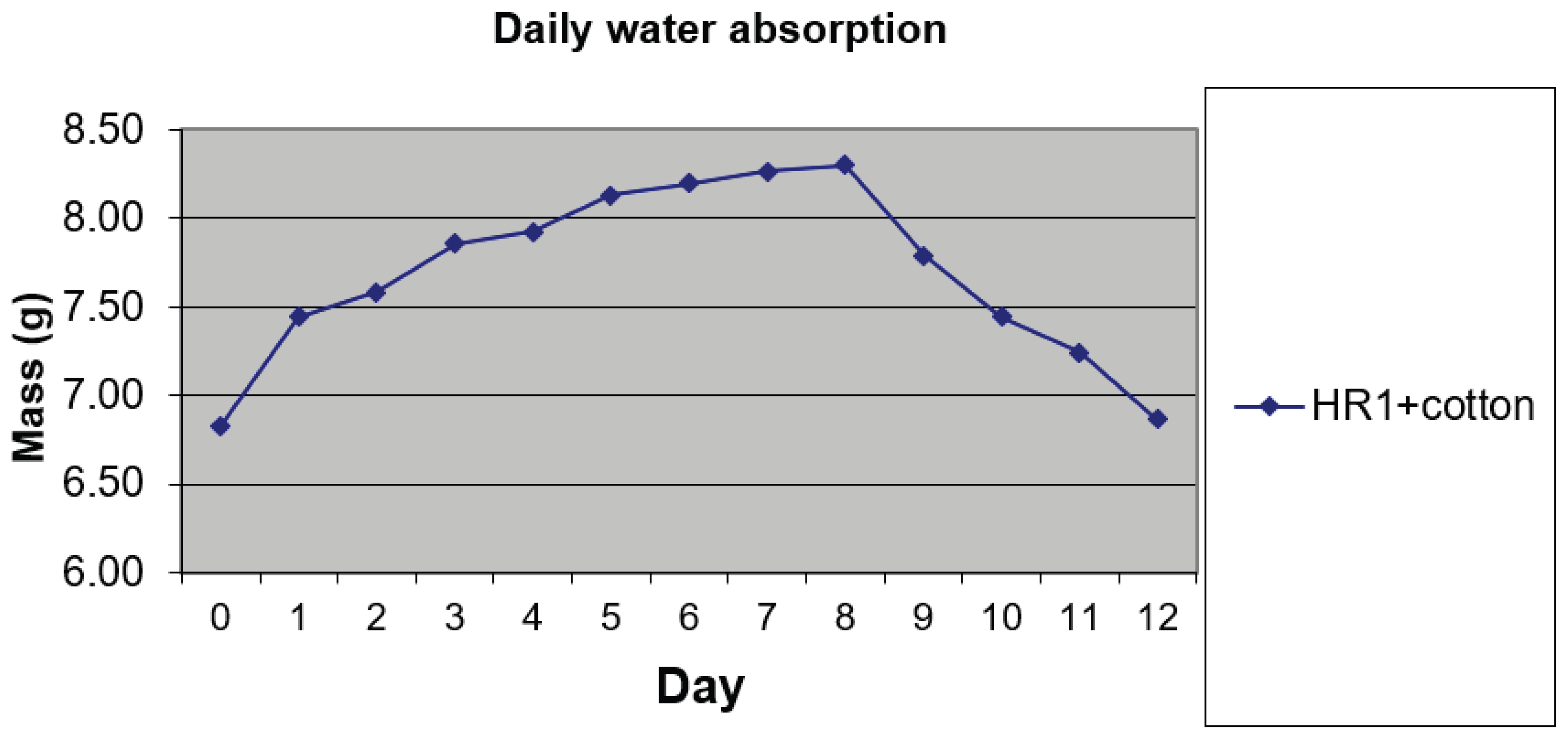

In the next stage, the water absorption behavior of the composite material with an HR1 matrix reinforced with cotton fibers was investigated.

Figure 22 presents a comprehensive overview of the experimental results related to the water absorption behavior of the investigated composite material with HR1 matrix and reinforced with cotton fiber. The HR1–cotton composite exhibited a significantly higher water uptake compared to the neat hybrid resins. Starting from an initial mass of 6.83 g, the specimen reached a maximum mass of 8.30 g after 8 days of immersion, corresponding to a maximum water absorption of approximately 21.5%. The experiment was terminated at Day 8 because the incremental mass change between Day 7 and Day 8 was < 0.05 g, suggesting that the specimen approached equilibrium water uptake. This behavior is attributed to the hydrophilic nature of cotton fibers, which readily absorb water; however, the absorbed moisture was not permanently retained within the composite structure, as the specimens were allowed to dry starting from Day 9, leading to a progressive mass reduction. The mass difference during the last two days was very small (≈0.02 g), indicating a continuing desorption trend; therefore, extending the experiment by one additional day would likely have brought the specimen mass close to its initial value, within the balance resolution.

3.7. Breaking Section Analysis with Microscopy

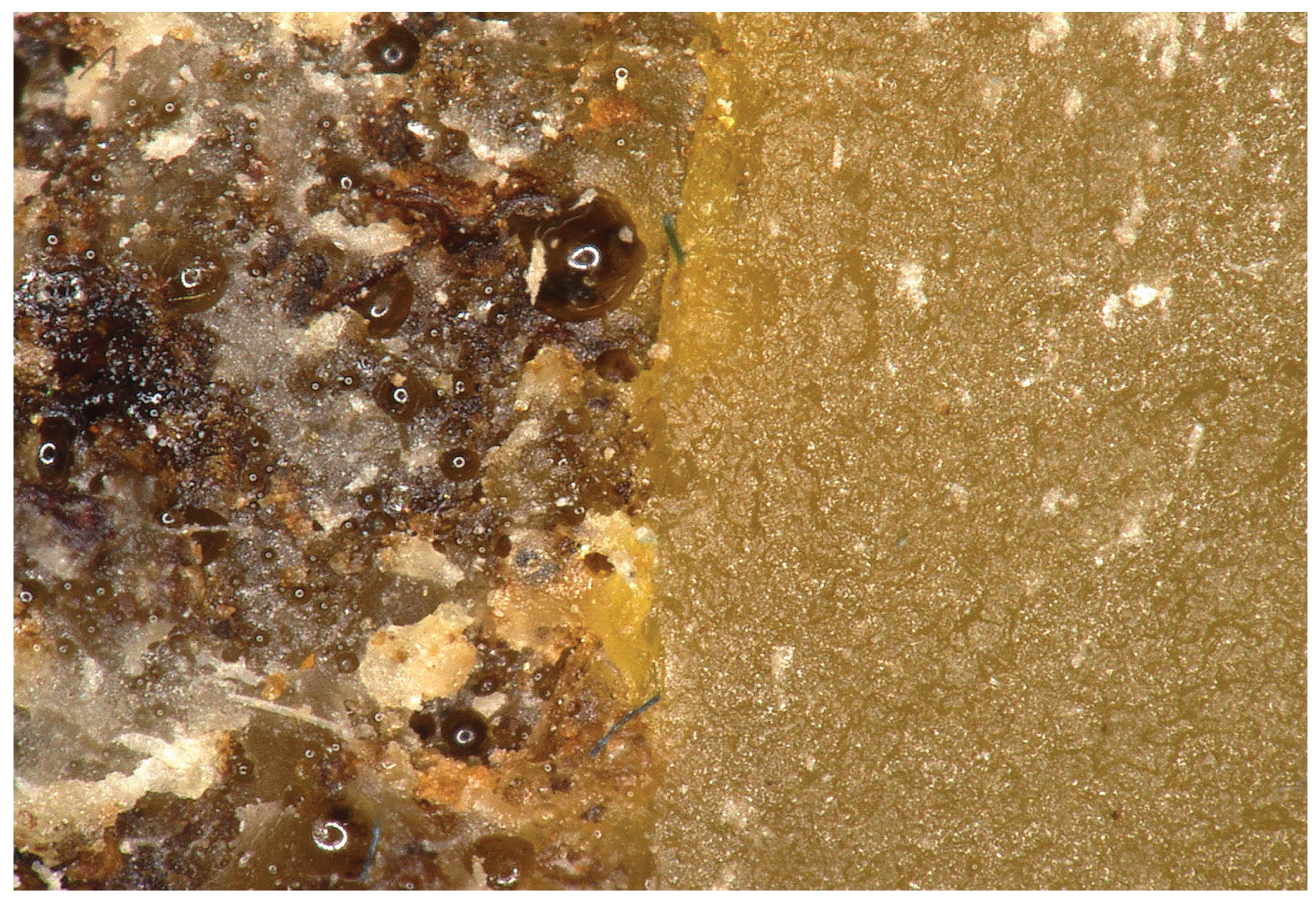

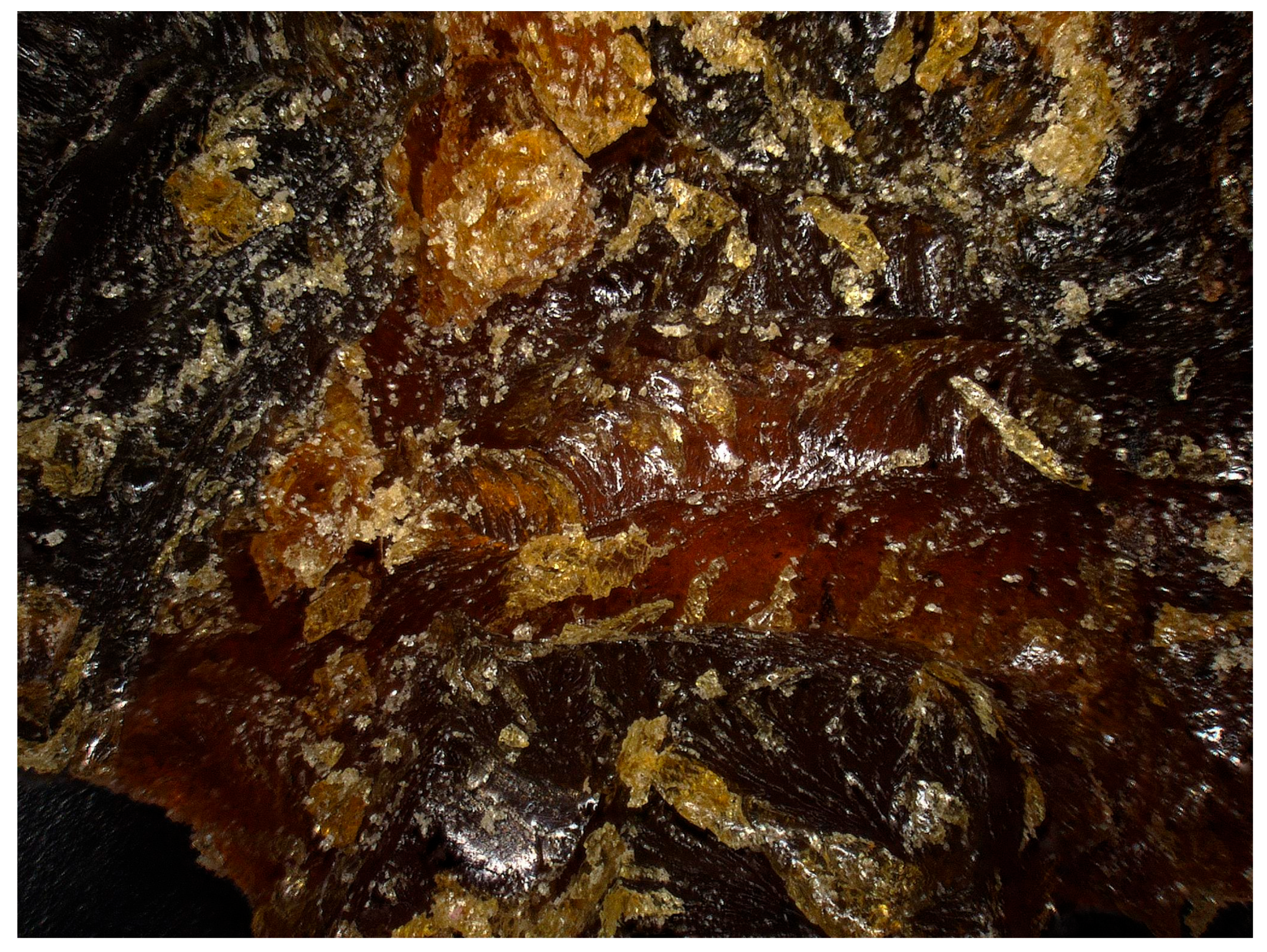

In the following, images of the fracture surfaces are presented for one representative specimen from each type of material investigated: the HR1 resin, the HR2 resin, and the composite with an HR1 matrix reinforced with cotton fibers, as shown in

Figure 23,

Figure 24 and

Figure 25.

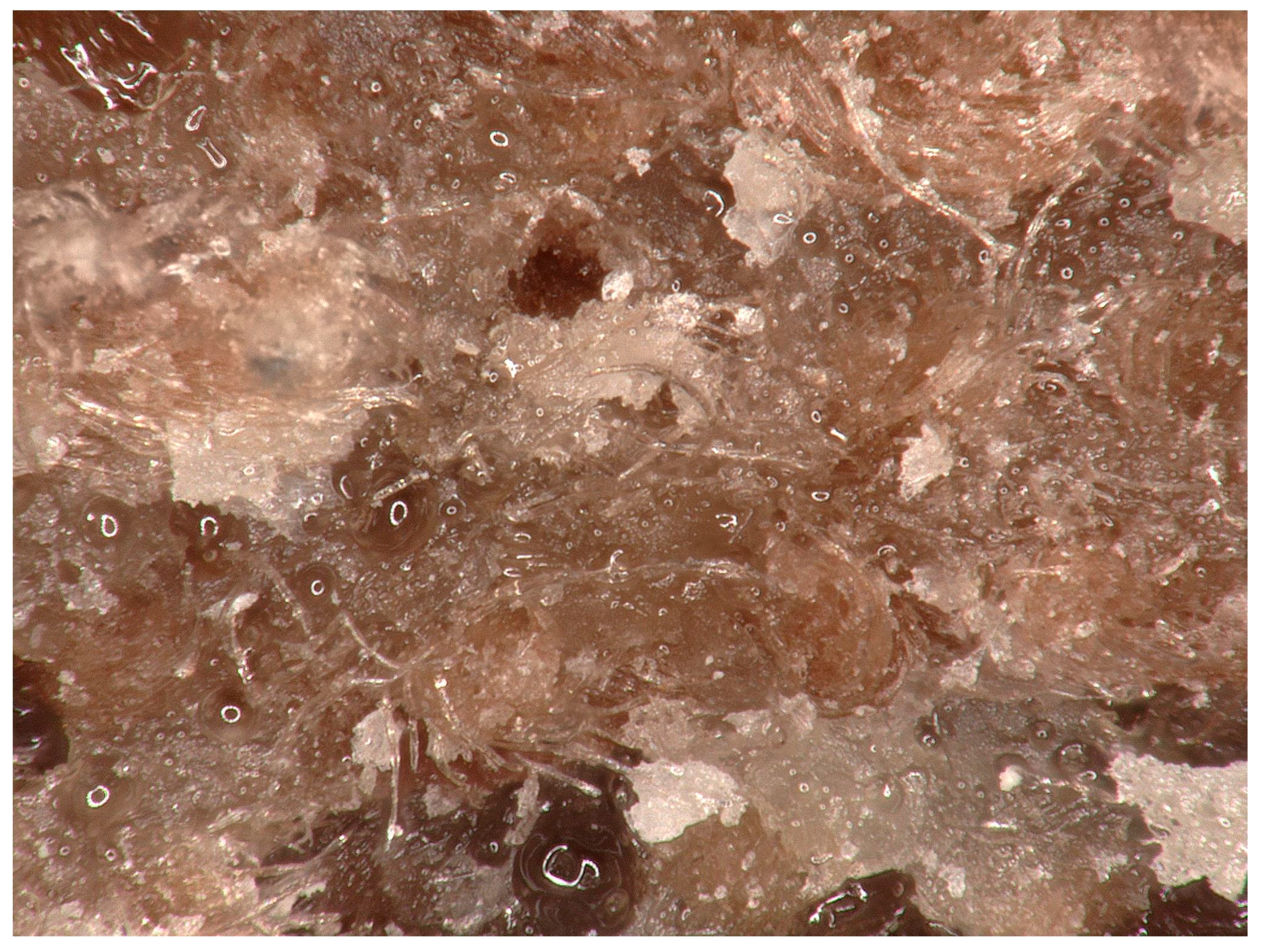

The fracture surface of the HR1 resin exhibits a heterogeneous morphology, characterized by rough regions interspersed with smoother areas (

Figure 23). The presence of distinct microstructural domains suggests partial phase separation between the epoxy-rich regions and the Abies alba resin phase dissolved in turpentine. Localized microvoids and irregular features can also be observed, likely resulting from solvent evaporation and limited miscibility between the constituent phases. The overall fracture appearance is consistent with a predominantly brittle to semi-brittle failure mechanism, in agreement with the high stiffness and low damping behavior of HR1.

In contrast to HR1, the fracture surface of the HR2 resin exhibits a markedly different morphology, characterized by a highly irregular and flow-like appearance (

Figure 24). The presence of elongated features, smeared regions, and the absence of well-defined cleavage planes indicate extensive plastic deformation prior to failure. This ductile fracture behavior is consistent with the pronounced viscoelastic response, low Shore D hardness, and high damping capacity observed for HR2, confirming the dominant role of the flexible polymer network formed through the alcohol-assisted formulation route.

In the HR1–cotton composite, the fracture surface no longer exhibits the distinct phase-separated regions observed in the neat HR1 resin (

Figure 25). The presence of cotton fibers promotes a more uniform fracture morphology, as the fibers act as physical bridges and anchoring sites for both the epoxy-rich and bio-resin phases. This fiber-induced constraint limits phase mobility during curing and fracture, leading to a finer-scale dispersion of the constituent phases and a more integrated composite structure.

4. Discussion

4.1. Influence of the Formulation Route on Matrix Structure and Static Mechanical Behavior

The experimental results clearly demonstrate that the formulation route used to liquefy the Abies alba exudate prior to blending with the epoxy resin plays a decisive role in governing the final structure and mechanical response of the hybrid matrices. Although both HR1 and HR2 contain the same mass fraction of natural resin and epoxy resin, the solvent employed during dissolution leads to fundamentally different polymer networks.

In the case of HR1, where the Abies alba exudate was dissolved in pine-bud turpentine, the resulting hybrid matrix exhibited high stiffness, relatively low elongation at break, and pronounced strength in tensile, compressive, and flexural loading. This behavior suggests the formation of a comparatively rigid and constrained polymer network, in which the epoxy-rich domains dominate load transfer. The partial phase separation observed in the fracture surface supports this interpretation, as localized epoxy-rich regions act as stiff load-bearing zones, while the bio-resin phase contributes to limited toughening.

By contrast, HR2—obtained by dissolving the Abies alba exudate in food-grade ethanol—displayed extremely low tensile and compressive strengths, accompanied by very large deformation and almost complete elastic recovery under bending. These characteristics indicate the formation of a highly flexible, loosely cross-linked network with dominant viscoelastic behavior. The ductile, flow-like fracture morphology observed for HR2 further confirms that failure occurs after extensive plastic deformation rather than through brittle crack propagation. Therefore, although the chemical constituents are nominally similar, the solvent-assisted formulation route strongly influences phase interactions and network mobility, ultimately controlling the static mechanical response.

From a chemical standpoint, no specific covalent co-network formation between Abies alba exudate and the epoxy system is assumed under the curing conditions used in this work. Diterpenic oleoresins such as Abies alba contain carboxylic and hydroxyl groups, but in the absence of catalysts or chemical modification steps these functionalities are not expected to induce extensive epoxy ring opening at room temperature. The hybrid matrices investigated here should therefore be regarded as physically hybridized systems, in which the epoxy network provides the main load-bearing phase, while the Abies alba exudate acts as a bio-based matrix modifier that alters morphology and network mobility, leading to the distinct mechanical responses observed for HR1 and HR2.

4.2. Dynamic Response and Vibration Damping Behavior

The trends identified in static mechanical testing are consistently reflected in the vibration response of the investigated materials. The HR1 resin exhibited a low damping ratio and a relatively low natural frequency, typical of stiff polymeric systems in which energy dissipation mechanisms are limited. This behavior is consistent with its high Shore D hardness and limited deformation under static loading.

In contrast, HR2 showed a markedly higher damping ratio, confirming its pronounced viscoelastic nature. The ability of HR2 to dissipate vibrational energy efficiently can be directly linked to the flexible polymer network inferred from both static mechanical tests and fracture surface observations. The elevated damping capacity of HR2 highlights its potential applicability in vibration-attenuation or damping-oriented components, rather than in load-bearing structural applications.

For the HR1–cotton composite, the natural frequency increased significantly compared to neat HR1, reflecting the enhanced stiffness introduced by textile reinforcement. However, the damping ratio remained close to that of the HR1 matrix, indicating that the dynamic response of the composite is still governed primarily by matrix behavior. This observation confirms that reinforcement improves stiffness and load-carrying capability without substantially altering intrinsic energy dissipation mechanisms.

4.3. Effect of Cotton Fiber Reinforcement on Structural Integration and Failure Mechanisms

The introduction of cotton fabric reinforcement into the HR1 matrix resulted in substantial improvements in tensile, compressive, and flexural performance, as well as an increase in Shore D hardness. These enhancements arise from the effective load transfer between matrix and reinforcement and from the constraining effect imposed by the fibrous network.

Fractographic analysis revealed that the HR1–cotton composite no longer exhibits the distinct phase-separated regions observed in neat HR1. Instead, the fracture surface appears more uniform, indicating that the cotton fibers act as physical bridges and anchoring sites for both epoxy-rich and bio-resin phases. This fiber-induced constraint limits phase mobility during curing and fracture, leading to a finer-scale dispersion of the constituent phases. Importantly, this does not imply complete chemical homogeneity, but rather a structurally integrated composite in which microscopically observable phase separation is suppressed by mechanical interlocking and interfacial interactions.

Consequently, cotton fibers act as a physical compatibilization medium, improving matrix continuity and damage tolerance without the need for chemical compatibilizers. This mechanism explains the simultaneous increase in strength, stiffness, and natural frequency observed for the reinforced system.

4.4. Water Absorption Behavior and Environmental Interaction

Water absorption tests revealed that both hybrid resins exhibit limited moisture uptake, with HR2 showing a slightly higher mass increase than HR1. This minor difference can be attributed to the more flexible and open network structure of HR2, which facilitates limited water diffusion. However, the overall water absorption of both neat hybrid resins remains low, reflecting the hydrophobic nature of the Abies alba exudate and the epoxy matrix.

In contrast, the HR1–cotton composite displayed significantly higher water uptake, reaching approximately 21.5% after eight days of immersion. This behavior is primarily governed by the hydrophilic nature of cotton fibers, which readily absorb water. The stabilization of mass gain toward the end of the immersion period indicates that equilibrium water uptake was approached. Moreover, the subsequent reduction in mass upon drying demonstrates that the absorbed water was not permanently retained within the composite structure. This reversible absorption–desorption behavior suggests that moisture is mainly stored within the cotton fibers rather than inducing irreversible swelling or degradation of the hybrid matrix.

Overall, these findings indicate that water absorption in the investigated systems is governed predominantly by reinforcement characteristics rather than by matrix chemistry, an aspect that must be considered when targeting applications in humid environments.

4.5. Implications for Hybrid Resin Design and Applications

Taken together, the results demonstrate that Abies alba exudate can be successfully valorized as a bio-derived component in hybrid resin systems with tunable mechanical and dynamic properties. By adjusting the dissolution route and incorporating natural fiber reinforcement, it is possible to obtain materials ranging from rigid, load-bearing matrices to highly elastic, vibration-damping polymers. This versatility highlights the potential of Abies alba–based hybrid resins for sustainable composite applications, where material performance can be tailored through formulation strategy rather than extensive chemical modification.

5. Conclusions

In this study, hybrid resin systems derived from Abies alba exudate were successfully developed and evaluated as matrices for composite materials. The results demonstrate that the formulation route used to liquefy the natural resin prior to epoxy hybridization plays a decisive role in controlling the mechanical and dynamic behavior of the resulting materials. The hybrid matrices are interpreted as physically combined systems rather than chemically co-networked structures, and the observed differences in performance are attributed to morphology and phase interactions rather than to new covalent bonding.

The HR1 system, obtained using turpentine as dissolution medium, exhibited a rigid structural response characterized by high stiffness, elevated Shore D hardness, low damping capacity, and a predominantly brittle to semi-brittle fracture behavior. In contrast, the HR2 system, formulated using ethanol, showed pronounced viscoelastic behavior, very low hardness, high elastic recovery, and significantly enhanced vibration damping capability, highlighting its potential for applications requiring energy dissipation rather than load-bearing performance.

The incorporation of cotton fabric reinforcement into the HR1 matrix led to a substantial improvement in mechanical strength, stiffness, and natural frequency, while suppressing microscopically observable phase separation. The fibers acted as physical compatibilizers, promoting structural integration of the hybrid matrix without the need for chemical compatibilizing agents.

Water absorption tests revealed that both hybrid resins exhibit limited moisture uptake, whereas the HR1–cotton composite displayed significantly higher, yet largely reversible, water absorption governed by the hydrophilic nature of the cotton fibers. These results indicate that moisture uptake in the investigated systems is primarily controlled by reinforcement characteristics rather than matrix chemistry.

Overall, the findings confirm that Abies alba exudate can be effectively valorized as a bio-derived component in hybrid resin systems with tunable static and dynamic properties. By adjusting the formulation route and reinforcement strategy, materials ranging from rigid structural matrices to highly elastic vibration-damping systems can be obtained, offering promising perspectives for sustainable polymer and composite applications.

Figure 3.

(a) A plate removed from the mold (example); (b) The polymerized hybrid resins, with different behaviour.

Figure 3.

(a) A plate removed from the mold (example); (b) The polymerized hybrid resins, with different behaviour.

Figure 4.

Samples used in the tensile test (a) HR2 samples; (b) HR1 samples.

Figure 4.

Samples used in the tensile test (a) HR2 samples; (b) HR1 samples.

Figure 5.

Samples reinforced with cotton fabric and HR1 matrix.

Figure 5.

Samples reinforced with cotton fabric and HR1 matrix.

Figure 6.

Samples used in the compression test (a) HR2 samples; (b) HR1 samples.

Figure 6.

Samples used in the compression test (a) HR2 samples; (b) HR1 samples.

Figure 7.

The characteristic curves for five representative specimens made of the HR1 resin (tensile test).

Figure 7.

The characteristic curves for five representative specimens made of the HR1 resin (tensile test).

Figure 8.

The characteristic curves for five representative specimens made of the HR2 resin (tensile test).

Figure 8.

The characteristic curves for five representative specimens made of the HR2 resin (tensile test).

Figure 9.

The characteristic curves for five representative specimens made of the HR1 resin and reinforced with cotton fibers (tensile test).

Figure 9.

The characteristic curves for five representative specimens made of the HR1 resin and reinforced with cotton fibers (tensile test).

Figure 10.

The characteristic curves for five representative specimens made of the HR1 resin (compression test).

Figure 10.

The characteristic curves for five representative specimens made of the HR1 resin (compression test).

Figure 11.

The characteristic curves for five representative specimens made of the HR2 resin (compression test).

Figure 11.

The characteristic curves for five representative specimens made of the HR2 resin (compression test).

Figure 12.

The characteristic curves for five representative specimens made of the HR1 resin (bending test).

Figure 12.

The characteristic curves for five representative specimens made of the HR1 resin (bending test).

Figure 13.

The characteristic curves for five representative specimens made of the HR2 resin (bending test).

Figure 13.

The characteristic curves for five representative specimens made of the HR2 resin (bending test).

Figure 14.

The characteristic curves for five representative specimens made of the HR1 resin and reinforced with cotton fibers (bending test).

Figure 14.

The characteristic curves for five representative specimens made of the HR1 resin and reinforced with cotton fibers (bending test).

Figure 15.

Flexural loading of HR2 specimens up to the end of traverse stroke.

Figure 15.

Flexural loading of HR2 specimens up to the end of traverse stroke.

Figure 16.

Elastic recovery of the HR2 specimen after the traverse returned to the initial

Figure 16.

Elastic recovery of the HR2 specimen after the traverse returned to the initial

Figure 17.

Experimental recording, determination of the damping factor and natural frequency for the HR2 material.

Figure 17.

Experimental recording, determination of the damping factor and natural frequency for the HR2 material.

Figure 18.

Experimental recording, determination of the damping factor and natural frequency for the HR1 material.

Figure 18.

Experimental recording, determination of the damping factor and natural frequency for the HR1 material.

Figure 19.

Experimental recording, determination of the damping factor and natural frequency for the composite with HR1 matrix and reinforced with cotton fiber.

Figure 19.

Experimental recording, determination of the damping factor and natural frequency for the composite with HR1 matrix and reinforced with cotton fiber.

Figure 20.

Summary of the experimental Shore D hardness data for each analyzed material type.

Figure 20.

Summary of the experimental Shore D hardness data for each analyzed material type.

Figure 21.

Daily water absorption of the hybrid resins.

Figure 21.

Daily water absorption of the hybrid resins.

Figure 22.

Daily water absorption of the composite material with HR1 resin and reinforced with cotton fibers.

Figure 22.

Daily water absorption of the composite material with HR1 resin and reinforced with cotton fibers.

Figure 23.

Fracture surface of a specimen made of HR1 resin (100X magnifaction).

Figure 23.

Fracture surface of a specimen made of HR1 resin (100X magnifaction).

Figure 24.

Fracture surface of a specimen made of HR2 resin (100X magnifaction).

Figure 24.

Fracture surface of a specimen made of HR2 resin (100X magnifaction).

Figure 25.

Fracture surface of a specimen made of HR1 resin and reinforced with cotton fiber (100X magnifaction).

Figure 25.

Fracture surface of a specimen made of HR1 resin and reinforced with cotton fiber (100X magnifaction).