Submitted:

14 January 2026

Posted:

14 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

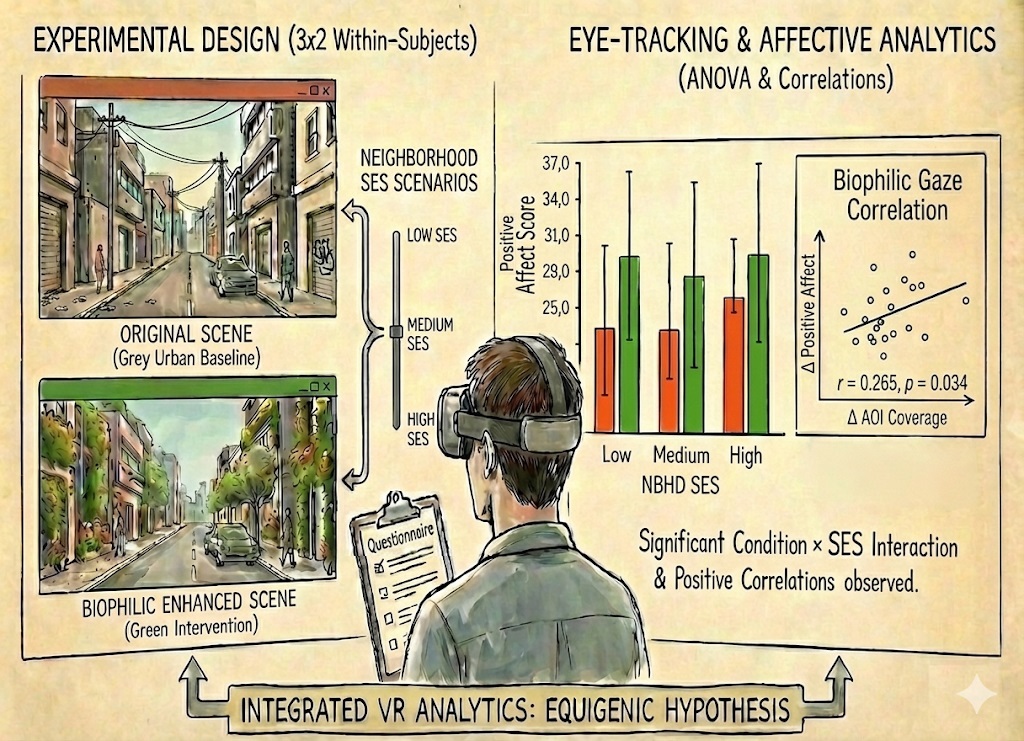

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Stimuli and Apparatus

2.3.1. Apparatus and Software

2.3.2. Visual Stimuli Production

2.3.3. Environmental Characterization & Validation

2.4. Measures

2.4.1. Subjective Measures

2.4.2. Objective Measures (Eye-Tracking)

2.5. Procedure

2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.6.1. Primary Analysis: Repeated Measures ANOVA

2.6.2. Exploratory Analysis: Low-Power Considerations and Correlations

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Affective States and Oculomotor Metrics

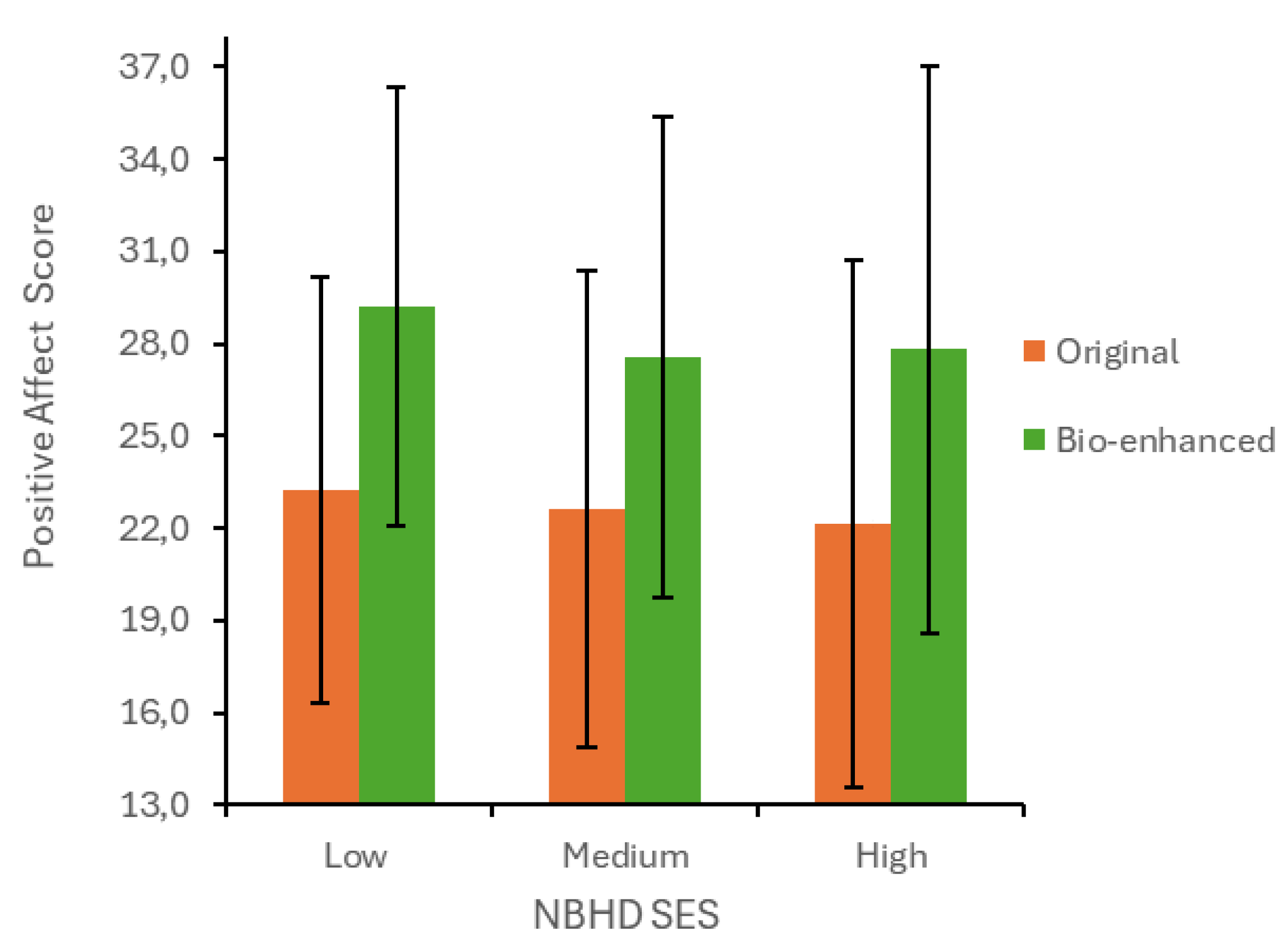

3.1.1. Positive Affect (PANAS)

3.1.2. Negative Affect (PANAS)

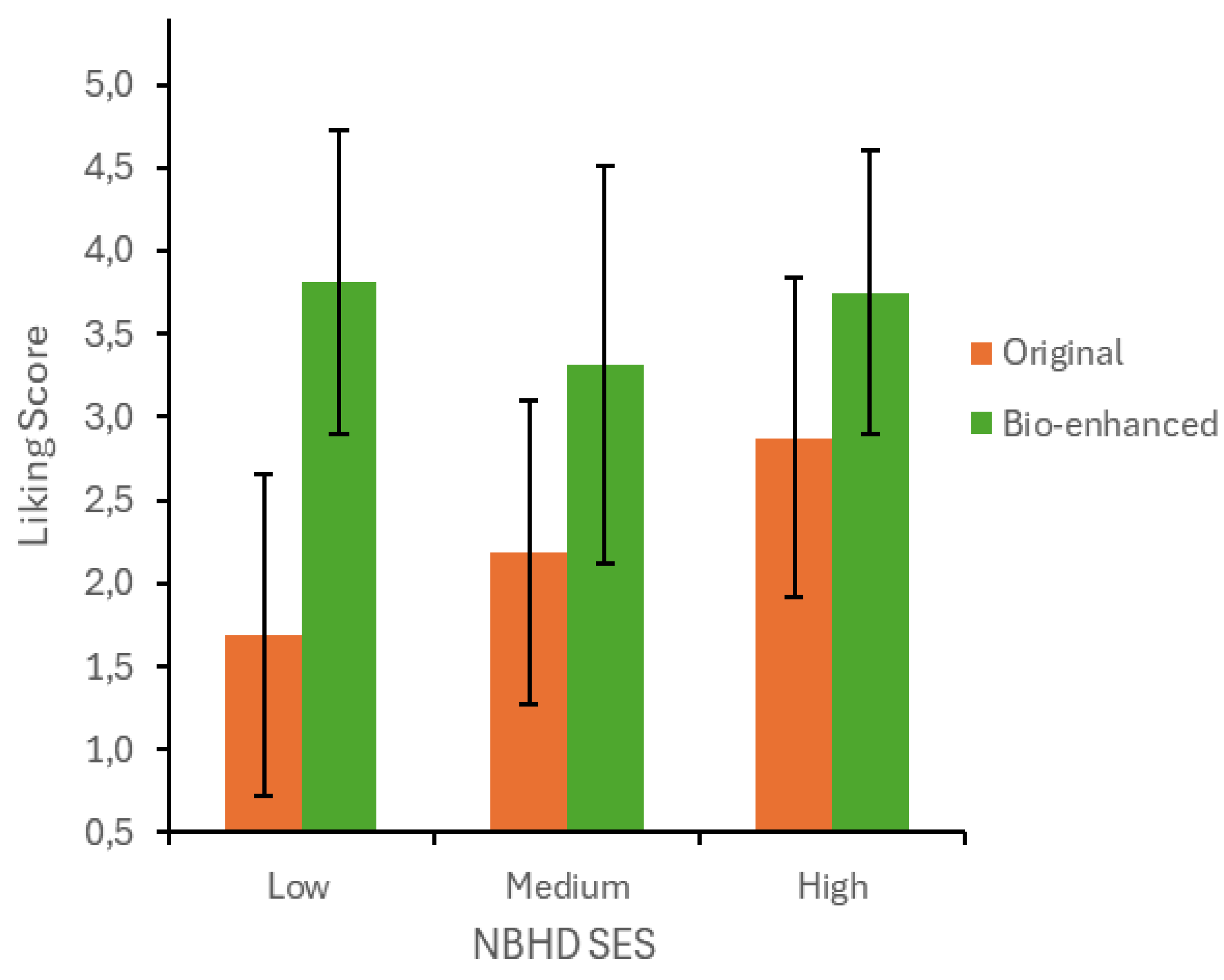

3.1.3. Liking

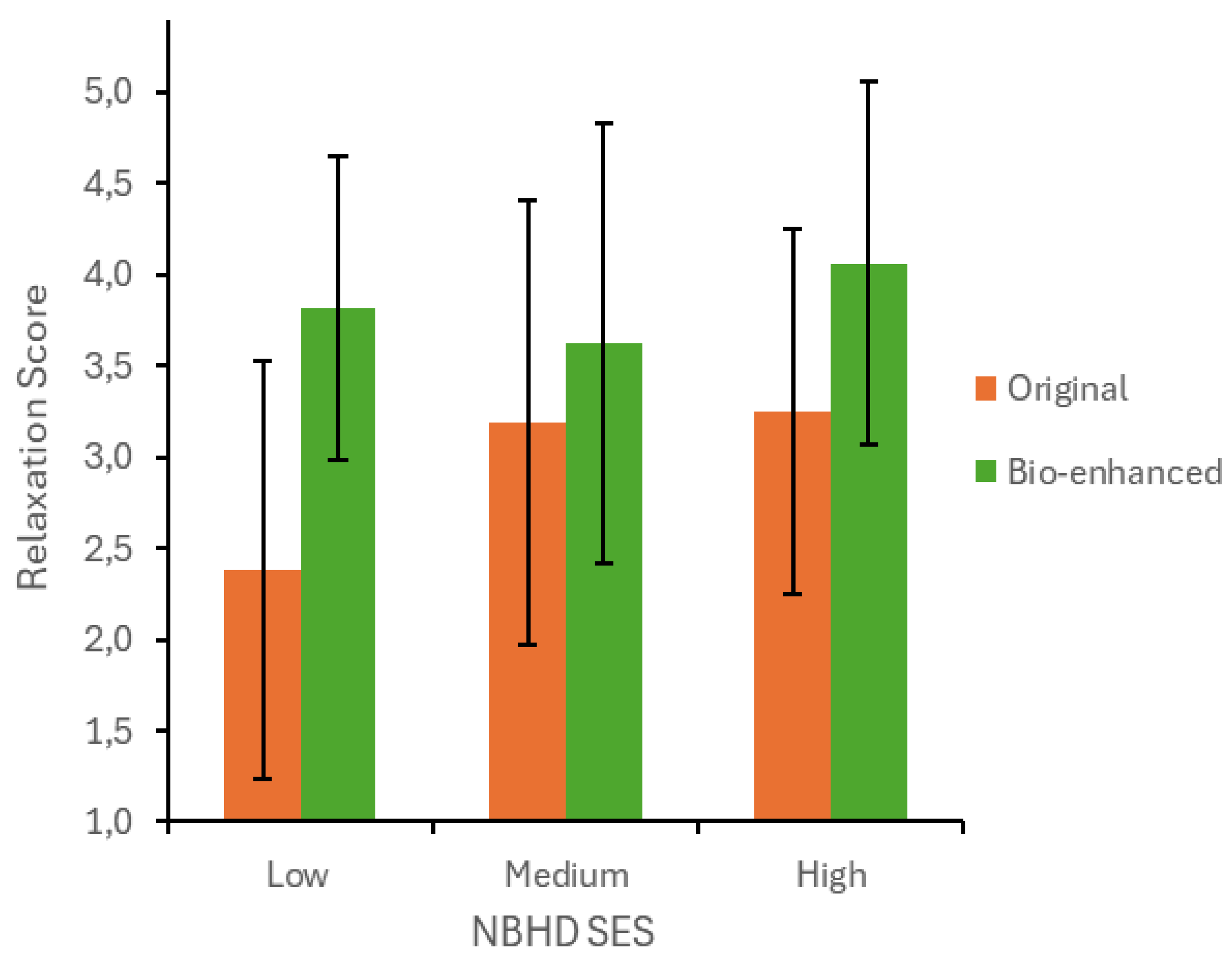

3.1.4. Relaxation

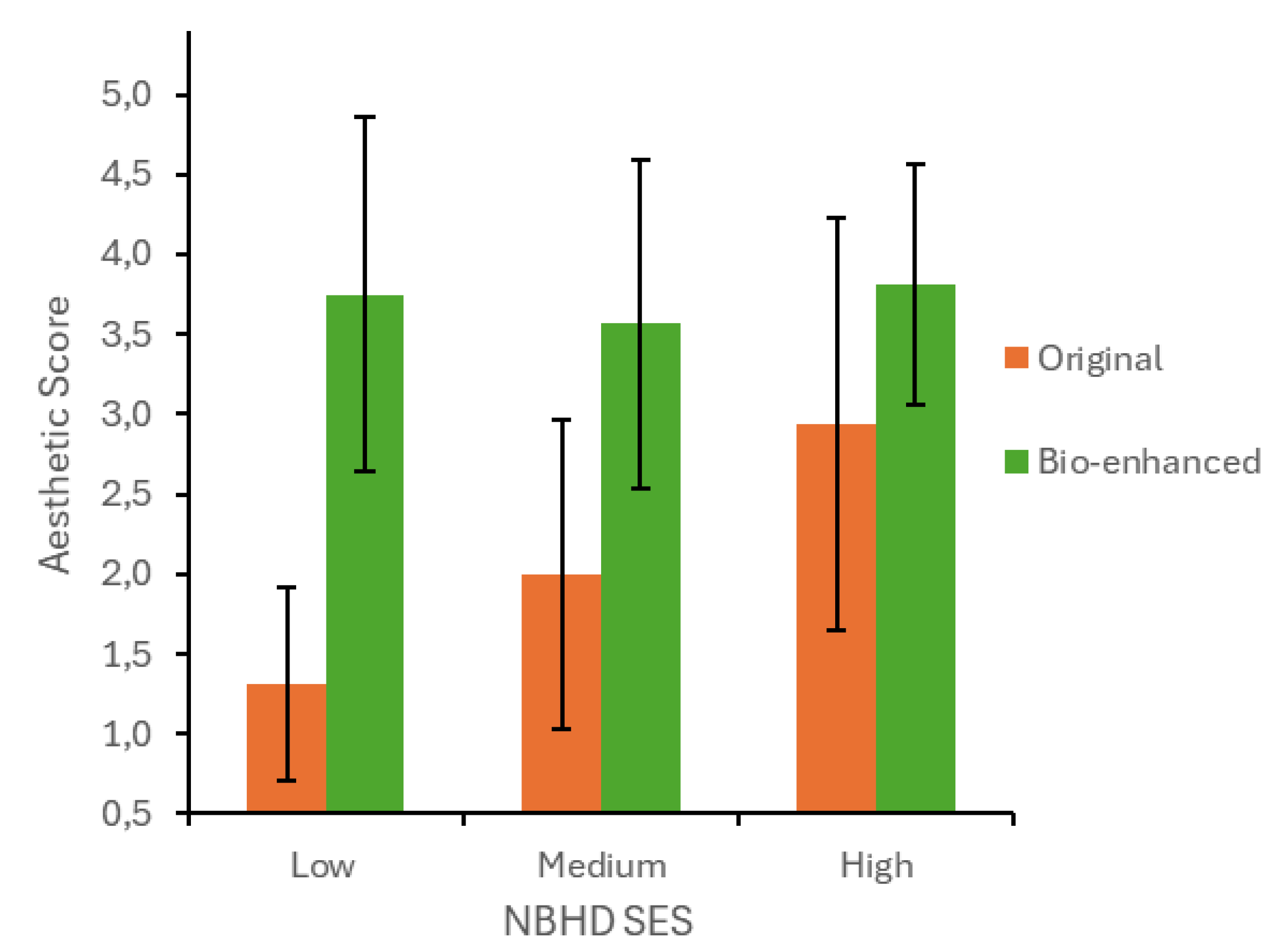

3.1.5. Aesthetic

3.1.6. Stress

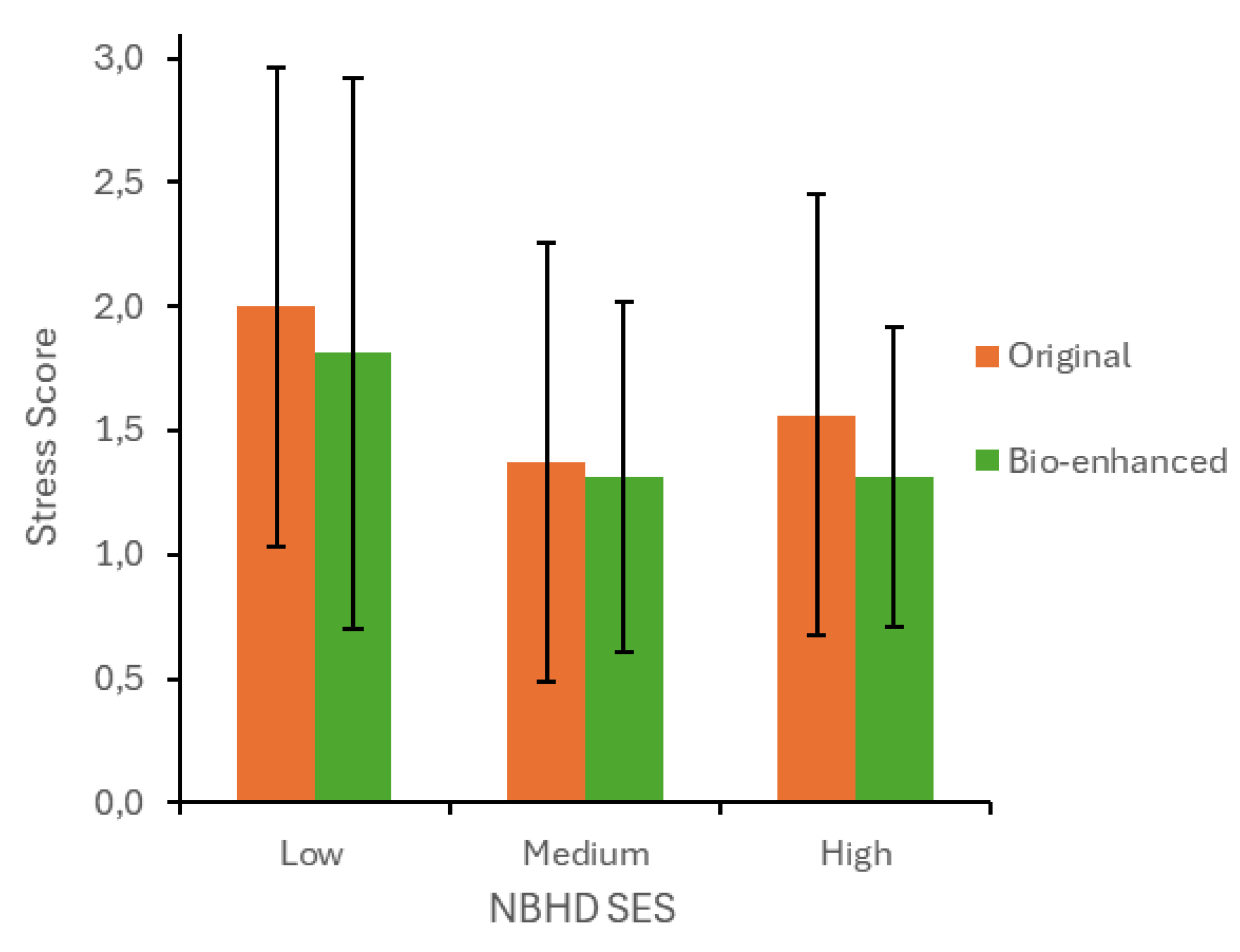

3.1.7. Average Saccadic Amplitude

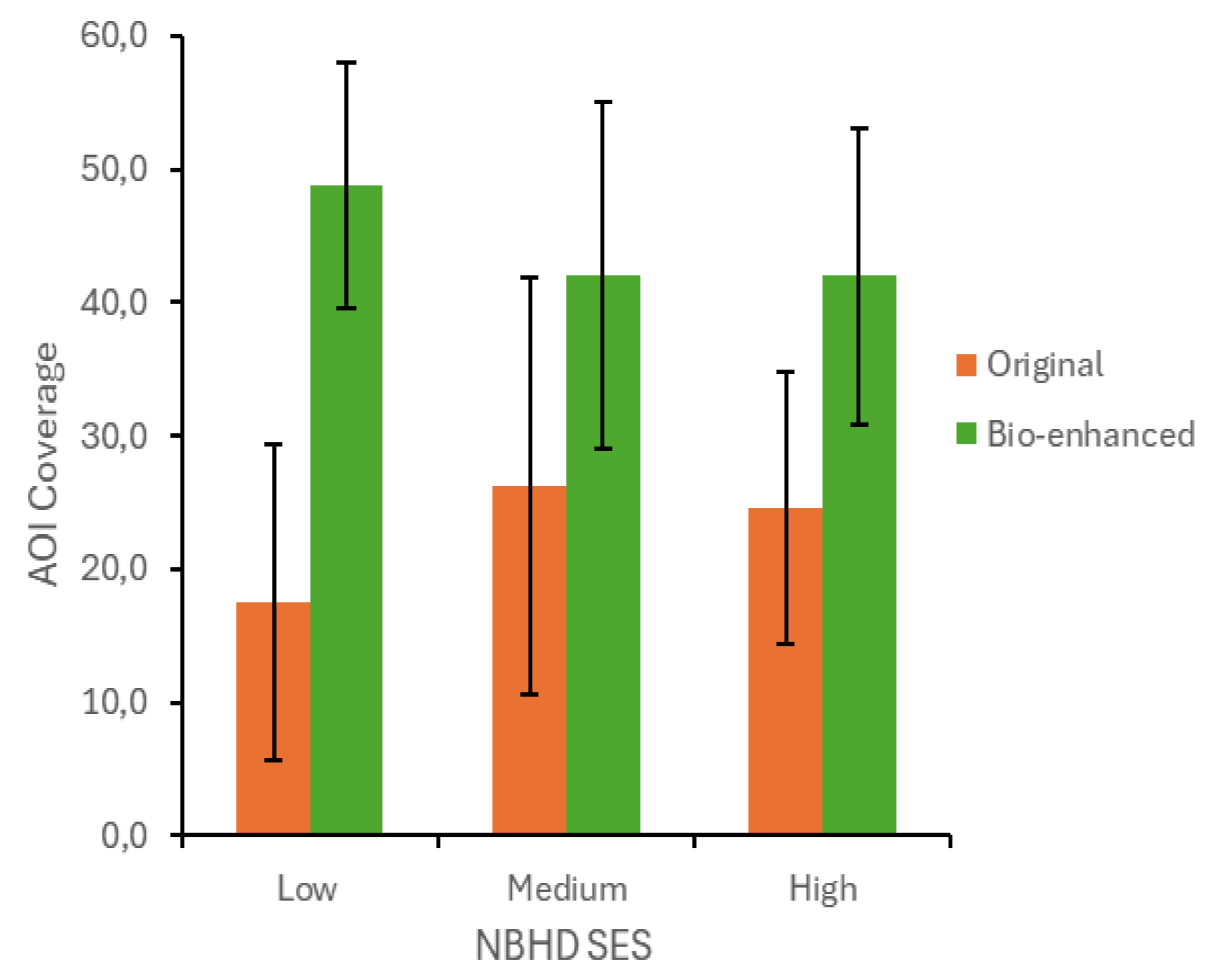

3.1.8. AOI Coverage

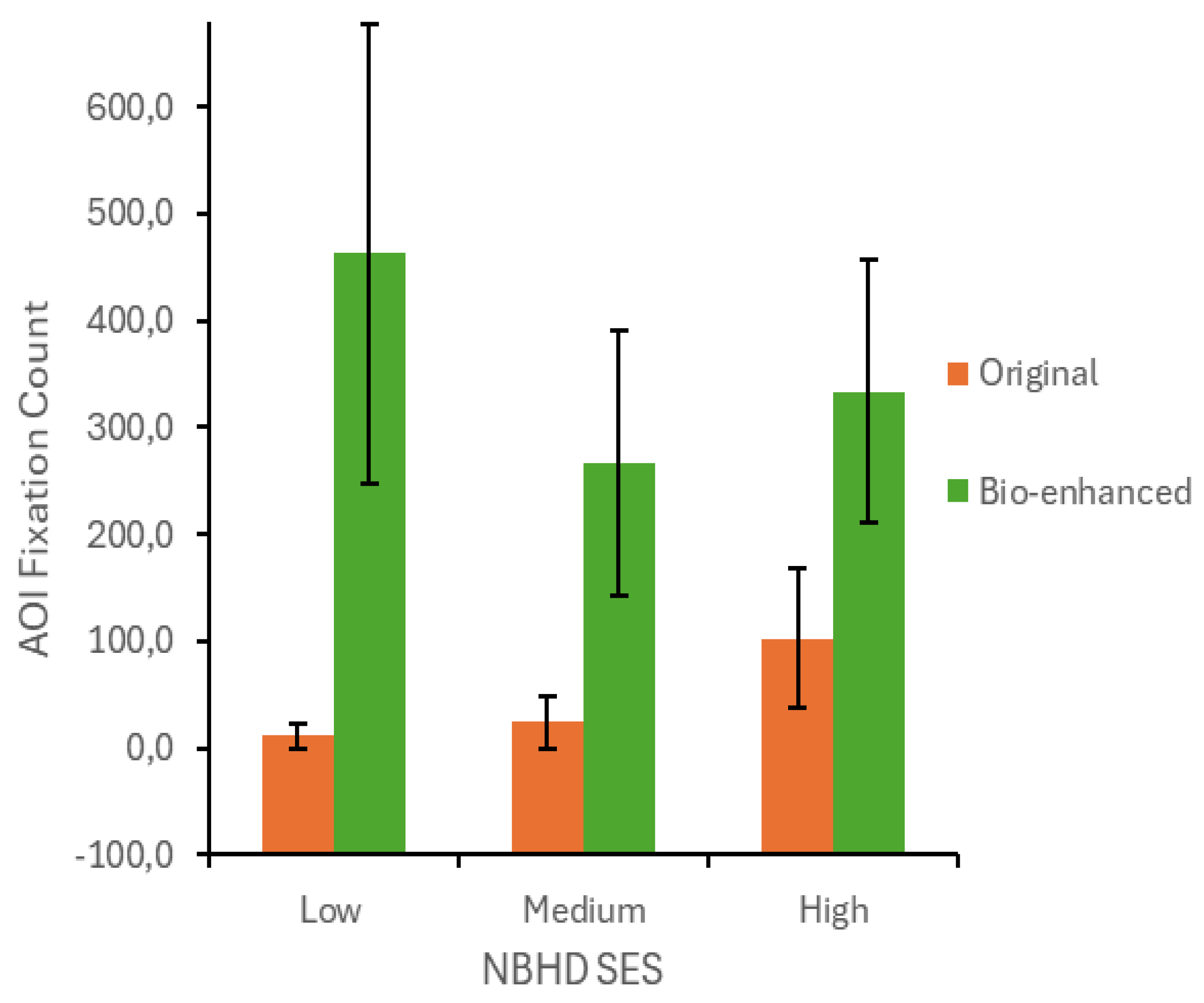

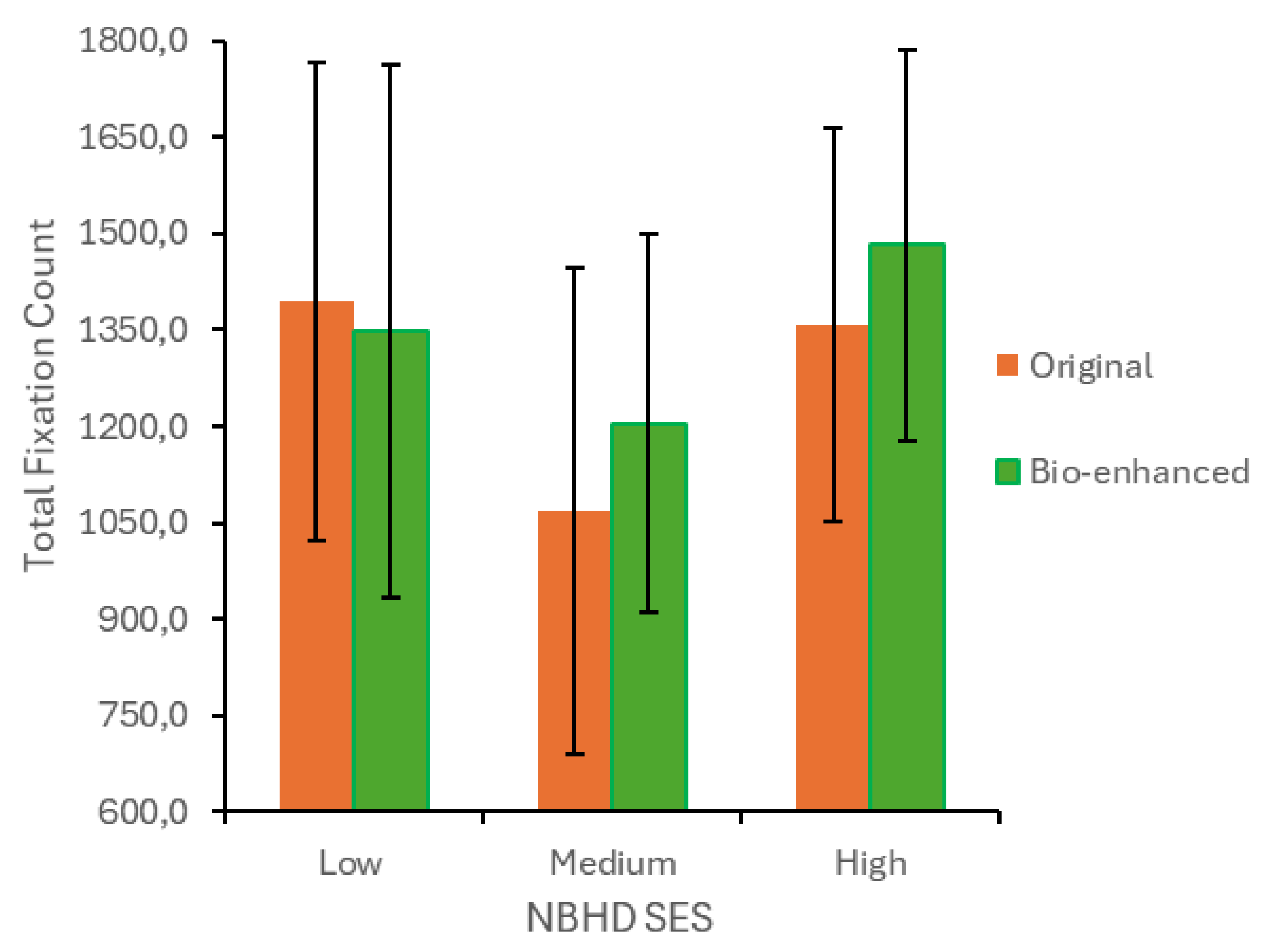

3.1.10. Total Fixation Count

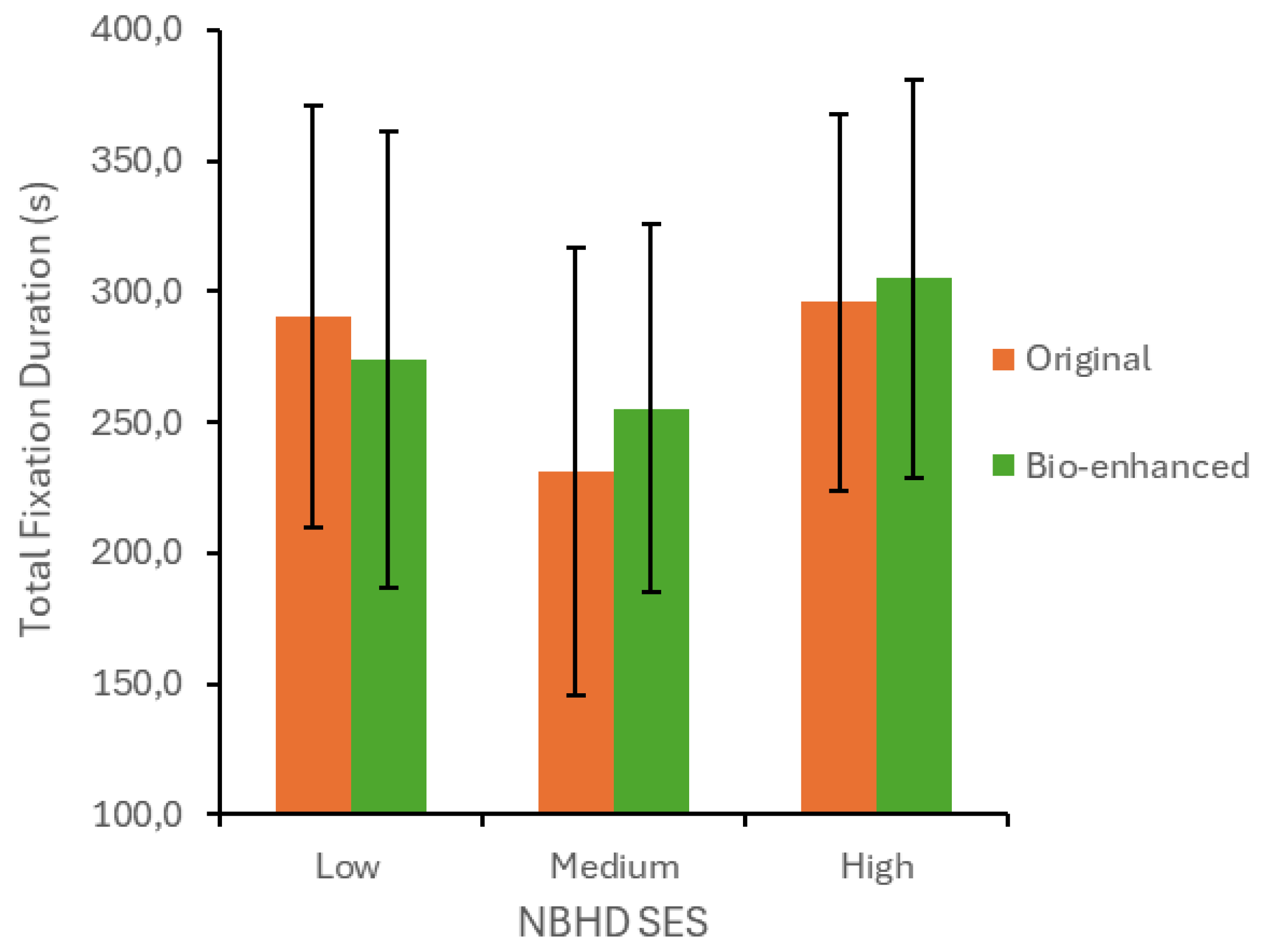

3.1.11. Total Fixation Duration

3.1.12. Time to First Fixation

3.1.13. Average Fixation Duration

3.1.14. Average Saccadic Velocity

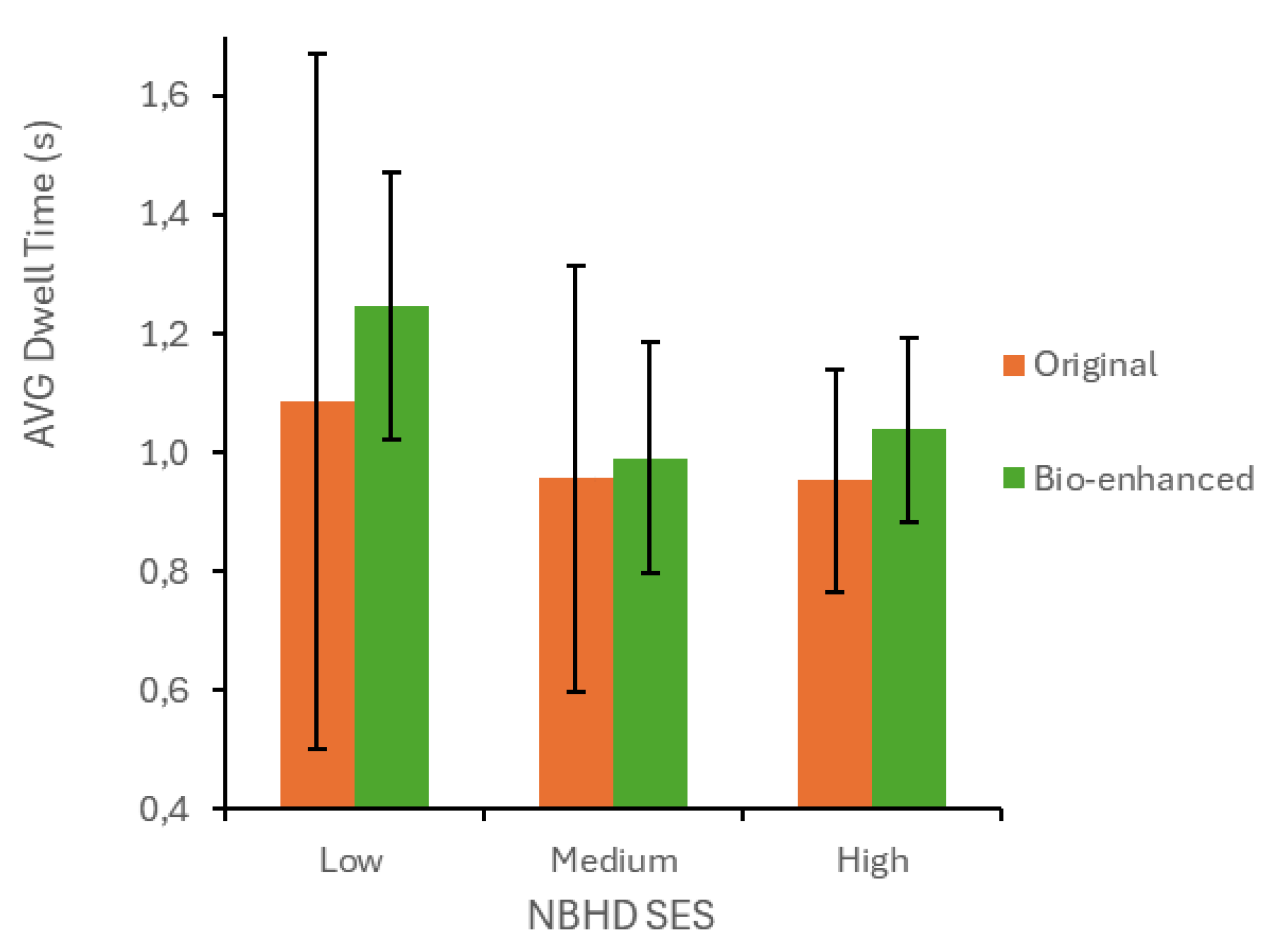

3.1.15. Average Dwell Time

3.2. Correlation Analyses Between Changes in Eye-Tracking Metrics and Affective States

4. Discussion

4.1. Socio-Perceptual Equity: Biophilic Enhancements as Urban Equalizers

4.2. Dissociating Affect from Stress: Oculomotor Signatures of ‘Hard Fascination’ in Low-SES Contexts

4.3. From Novelty to Restoration: Cognitive Load and the Temporal Dynamics of the Nature Gaze

4.4. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kellert, S. Nature by Design: The Practice of Biophilic Design; 2018; p. 214. ISBN 978-0-300-23543-2. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, C.; Browning, W.; Clancy, J.; Andrews, S.; Kallianpurkar, N. Biophilic Design Patterns: Emerging Nature-Based Parameters for Health and Well-Being in the Built Environment. Archnet-IJAR 2014, 8, 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higuera-Trujillo, J.L.; Llinares, C.; Macagno, E. The Cognitive-Emotional Design and Study of Architectural Space: A Scoping Review of Neuroarchitecture and Its Precursor Approaches. Sensors 2021, 21, 2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; The experience of nature: A psychological perspective; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, US, 1989; p. pp. xii, 340. ISBN 978-0-521-34139-4. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Park, H.; Choo, S. Effects of Changes to Architectural Elements on Human Relaxation-Arousal Responses: Based on VR and EEG. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 4305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finkler, W.; Vlietstra, L.; Waters, D.L.; Zhu, L.; Gallagher, S.; Walker, R.; Forlong, R.; van Heezik, Y. Virtual Nature and Well-Being: Exploring the Potential of 360° VR. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2025, 17, e70008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frost, S.; Kannis-Dymand, L.; Schaffer, V.; Millear, P.; Allen, A.; Stallman, H.; Mason, J.; Wood, A.; Atkinson-Nolte, J. Virtual Immersion in Nature and Psychological Well-Being: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 80, 101765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Chai, S.; Tang, J.; Zhou, X.; Wang, K. Eye-Tracking in AR/VR: A Technological Review and Future Directions. IEEE Open J. Immersive Disp. 2024, 1, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, D.; Jeong, M.; Yang, U.; Han, K. Eyes on Me: Investigating the Role and Influence of Eye-Tracking Data on User Modeling in Virtual Reality. PLOS ONE 2022, 17, e0278970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, D.; Foxman, M.; Davis, D.Z.; Markowitz, D.M. Virtually Real, But Not Quite There: Social and Economic Barriers to Meeting Virtual Reality’s True Potential for Mental Health. Front. Virtual Real. 2021, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siette, J.; Adam, P.J.; Harris, C.B. Acceptability of Virtual Reality to Screen for Dementia in Older Adults. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, A.; Kim, K.; Bruder, G.; Welch, G.F. Exploring the Limitations of Environment Lighting on Optical See-Through Head-Mounted Displays. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2020 ACM Symposium on Spatial User Interaction, New York, NY, USA, October 30 2020; Association for Computing Machinery; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Huyan, J.; Ramkissoon, C.; Laka, M.; Gaskin, S. Assessing the Usefulness of Mobile Apps for Noise Management in Occupational Health and Safety: Quantitative Measurement and Expert Elicitation Study. JMIR MHealth UHealth 2023, 11, e46846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, G.; Roland-Mieszkowski, M.; Jason, T.; Rainham, D.G. Noise Levels Associated with Urban Land Use. J. Urban Health 2012, 89, 1017–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Du, J. Effects of Neighbourhood Morphological Characteristics on Outdoor Daylight and Insights for Sustainable Urban Design. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2022, 21, 342–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandín, B.; Chorot, P.; Lostao, L.; Joiner, T.E.; Santed, M.A.; Valiente, R.M. Escalas PANAS de Afecto Positivo y Negativo: Validación Factorial y Convergencia Transcultural. [The PANAS Scales of Positive and Negative Affect: Factor Analytic Validation and Cross-Cultural Convergence.]. Psicothema 1999, 11, 37–51. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, R.; Popham, F. Effect of Exposure to Natural Environment on Health Inequalities: An Observational Population Study. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2008, 372, 1655–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward Thompson, C.; Roe, J.; Aspinall, P.; Mitchell, R.; Clow, A.; Miller, D. More Green Space Is Linked to Less Stress in Deprived Communities: Evidence from Salivary Cortisol Patterns. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2012, 105, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzel, C.; Reese, G. Seeing Nature from Low to High Levels: Mechanisms Underlying the Restorative Effects of Viewing Nature Images. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 81, 101804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, A.D.F.; Mahon, A.; Irvine, A.; Hunt, A.R. People Are Unable to Recognize or Report on Their Own Eye Movements. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 2017, 70, 2251–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollander, J.B.; Purdy, A.; Wiley, A.; Foster, V.; Jacob, R.J.K.; Taylor, H.A.; Brunyé, T.T. Seeing the City: Using Eye-Tracking Technology to Explore Cognitive Responses to the Built Environment. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2019, 12, 156–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orquin, J.L.; Holmqvist, K. Threats to the Validity of Eye-Movement Research in Psychology. Behav. Res. Methods 2018, 50, 1645–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, W.; Rizowy, B.; Shwartz, A.; Natural Sciences, B.; Town Planning, H.; Biodiversity Research Lab; H. The Nature Gaze: Eye-tracking Experiment Reveals Well-being Benefits Derived from Directing Visual Attention towards Elements of Nature. 2024, 1469–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unema, P.J.A.; Pannasch, S.; Joos, M.; Velichkovsky, B.M. Time Course of Information Processing during Scene Perception: The Relationship between Saccade Amplitude and Fixation Duration. Vis. Cogn. 2005, 12, 473–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, H.H.; Diwadkar, V.A.; Brown, J.M. Regularities in Vertical Saccadic Metrics: New Insights, and Future Perspectives. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mostajeran, F.; Friedrich, M.; Steinicke, F.; Kühn, S.; Stuerzlinger, W. The Effects of Biophilic Design on Steering Performance in Virtual Reality. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 32485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Y.; Chen, Q.; Lin, X.; Chi, Y.; Li, K. Restorative Effects of Small Urban Parks: A Multi-Method Study Using Eye-Tracking and Psychophysiological Measures in Fuzhou, China. Front. Public Health 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berto, R. Exposure to Restorative Environments Helps Restore Attentional Capacity. J. Environ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Ruan, R.; Deng, W.; Gao, J. The Effect of Visual Attention Process and Thinking Styles on Environmental Aesthetic Preference: An Eye-Tracking Study. Front. Psychol. 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohly, H.; White, M.P.; Wheeler, B.W.; Bethel, A.; Ukoumunne, O.C.; Nikolaou, V.; Garside, R. Attention Restoration Theory: A Systematic Review of the Attention Restoration Potential of Exposure to Natural Environments. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health B Crit. Rev. 2016, 19, 305–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valtchanov, D.; Ellard, C.G. Cognitive and Affective Responses to Natural Scenes: Effects of Low Level Visual Properties on Preference, Cognitive Load and Eye-Movements. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 43, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguel-Alonso, I.; Checa, D.; Guillen-Sanz, H.; Bustillo, A. Evaluation of the Novelty Effect in Immersive Virtual Reality Learning Experiences. Virtual Real. 2024, 28, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, K.; Bex, P. Cognitive Load Influences Oculomotor Behavior in Natural Scenes. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 12405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. The Restorative Benefits of Nature: Toward an Integrative Framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Yu, Z.; Ma, W.; Xiong, J.; Yang, G. Quantifying Threshold Effects of Physiological Health Benefits in Greenspace Exposure. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2024, 241, 104917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Liu, H.; Liu, B.; Diao, H.; Wang, J. Can Urban Forests Alleviate Eye Strain? Evidence from Eye-Tracking Metrics. Trees For. People 2026, 23, 101096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.