Submitted:

12 January 2026

Posted:

14 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

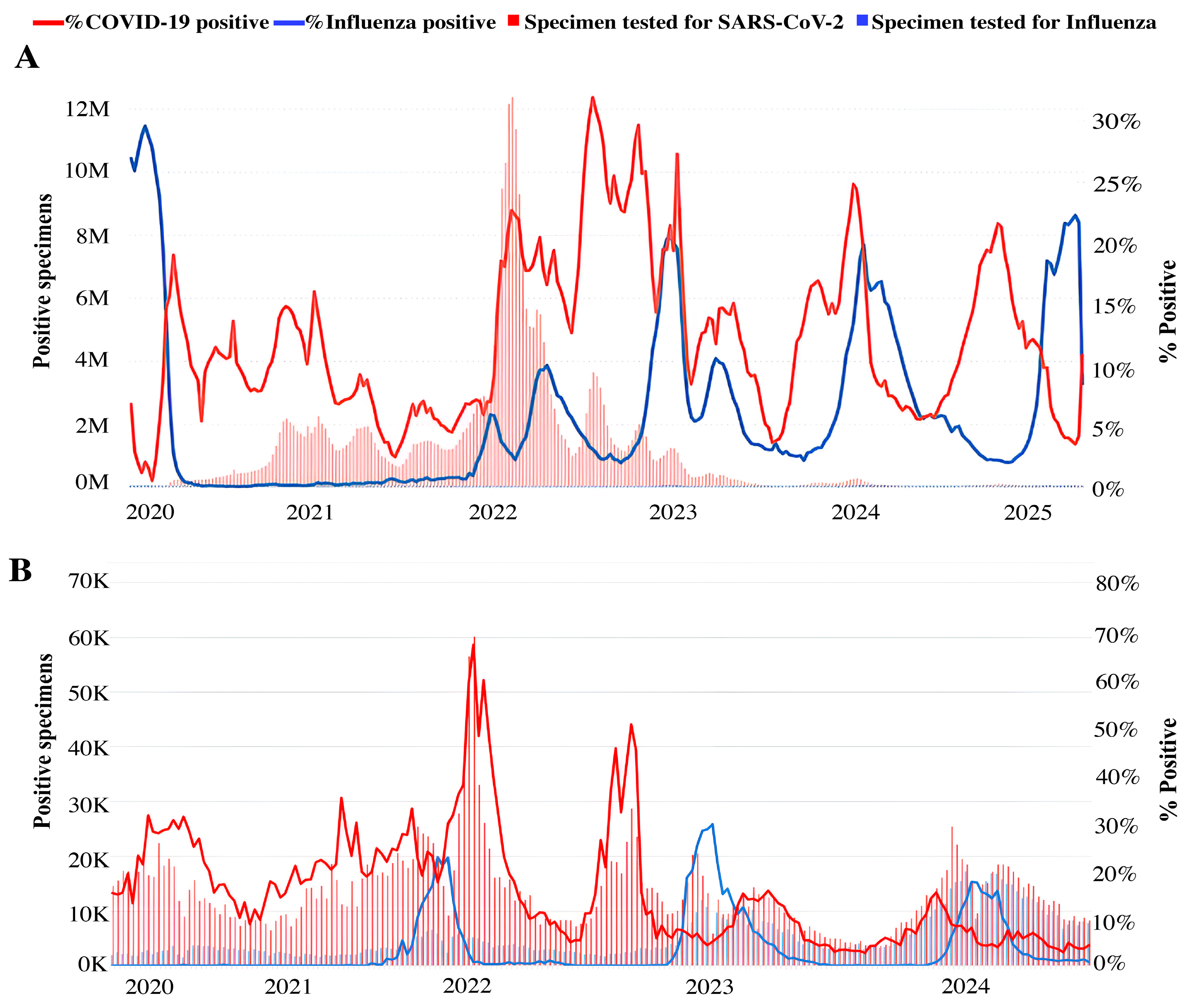

2. SARS-CoV-2 and Influenza Virus Co-Circulation and Co-Infection

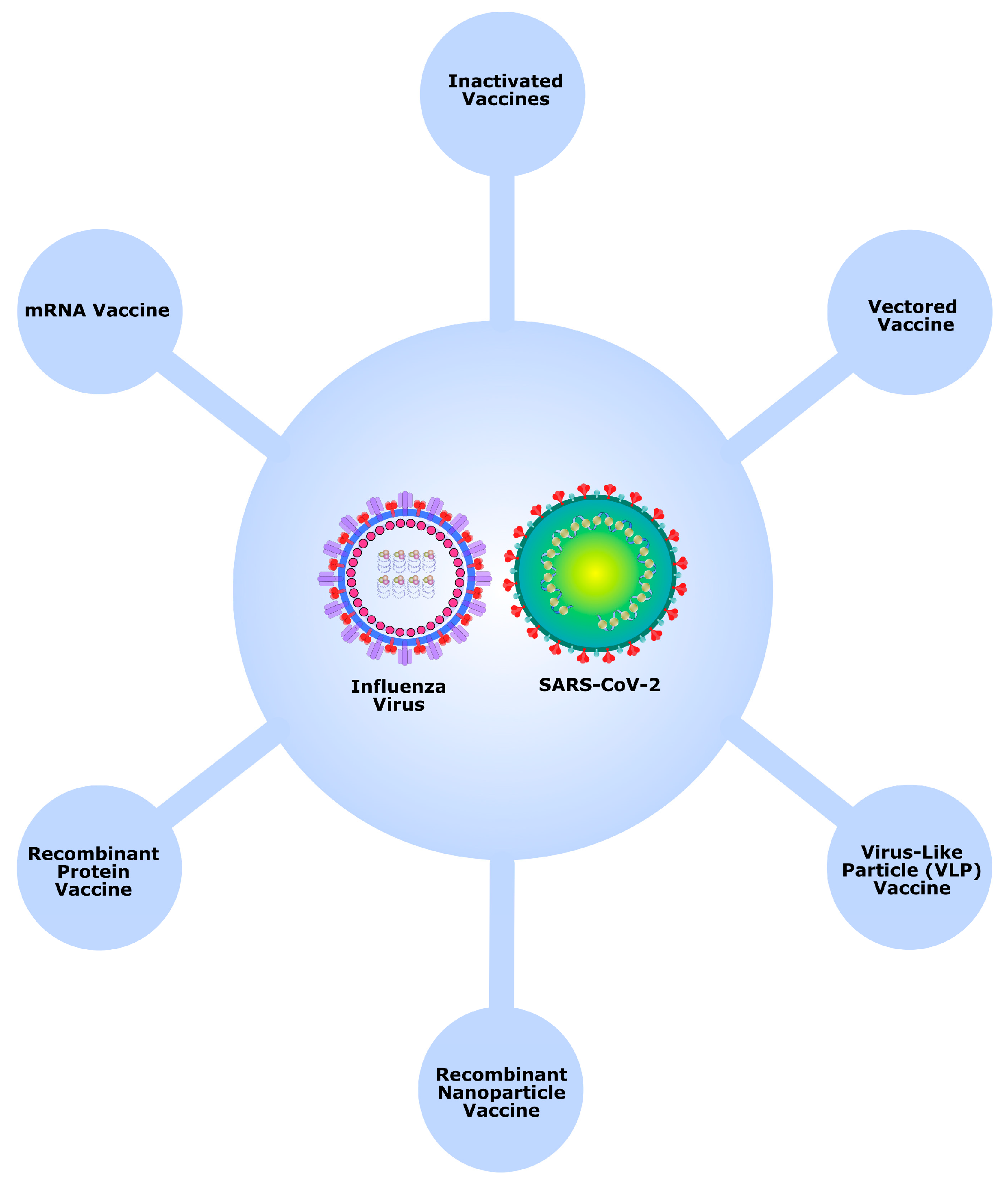

3. Concepts of Simultaneous and Combined Vaccination Against COVID-19 and Influenza

4. Animal Studies of Co-Vaccination Against COVID-19 and Influenza

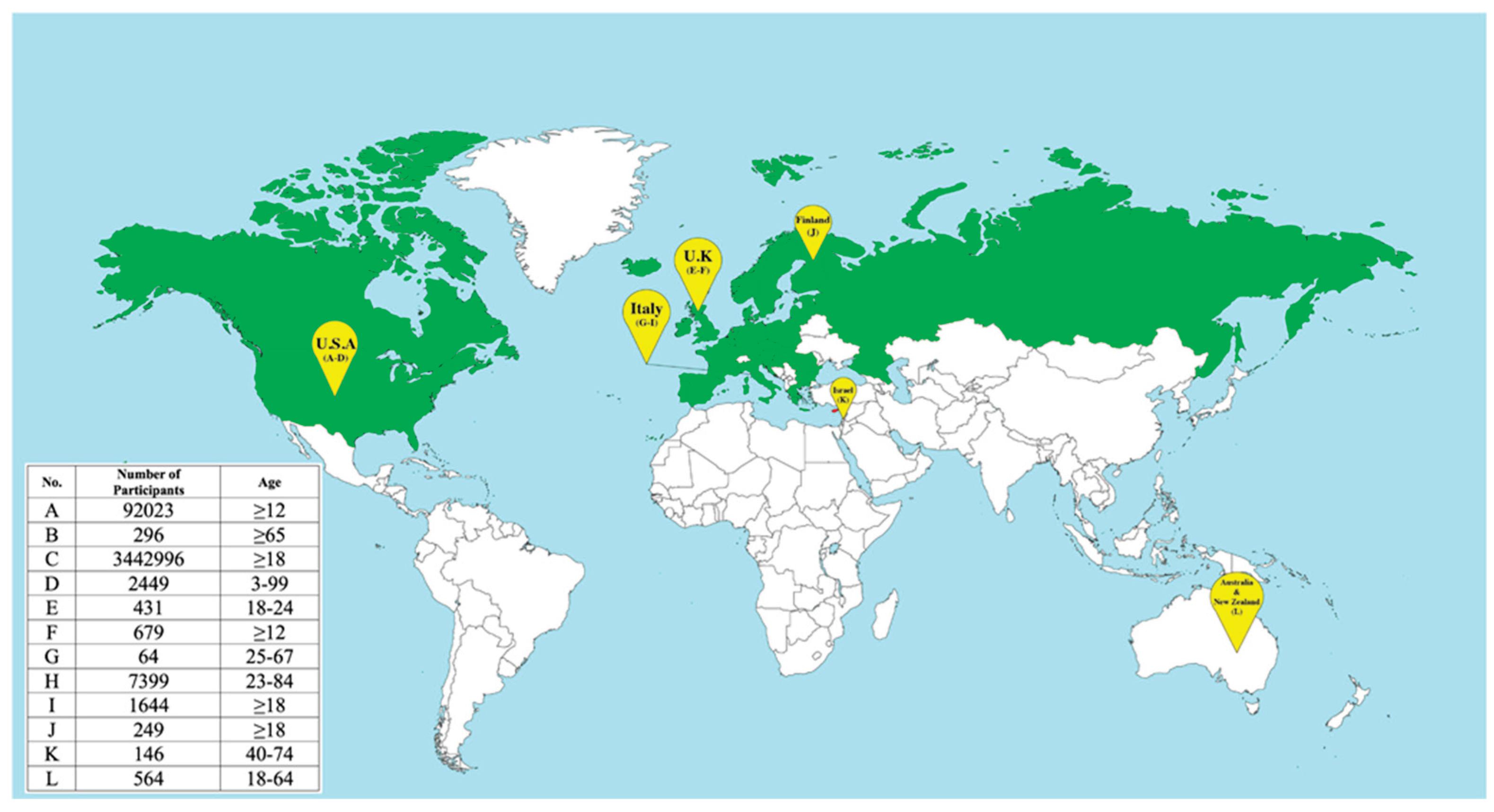

5. Clinical Studies of Co-Administration of Influenza and COVID-19 Vaccines

6. Clinical Studies of Combined Influenza and SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACE2 | Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 |

| AdC68 | Chimpanzee adenovirus 68 |

| BAL | Bronchoalveolar lavage |

| HA | Hemagglutinin |

| HAI | Hemagglutination Inhibition Assay |

| HI | Hemagglutination Inhibition |

| IAV | Influenza A virus |

| Ig | Immunoglobulin |

| IM | Intramuscular |

| IN | Intranasal |

| IP | Intraperitoneal |

| IND | Investigational New Drug |

| LNP | Lipid Nanoparticle |

| PLGA | Co-polymer of lactic and glycolic acids |

| qIRV | Quadrivalent influenza modRNA vaccine |

| QIV | Quadrivalent Inactivated Influenza Vaccine |

| RBD | Receptor-Binding Domain |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 |

| SIV | Seasonal Influenza Vaccines |

| SIIV | Seasonal Inactivated Influenza Vaccine |

| TIV | Trivalent Inactivated Influenza vaccine |

| QIV-HD | High-dose quadrivalent influenza vaccine |

| V-safe | Vaccine safety |

| VAERS | Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System |

| VLP | Virus-Like Particle |

References

- Taubenberger, J.K.; Morens, D.M. Influenza: The Once and Future Pandemic. Public health reports 2010, 125, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Influenza (Seasonal). Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/influenza-(seasonal).

- Peacock, T.P.; Moncla, L.; Dudas, G.; VanInsberghe, D.; Sukhova, K.; Lloyd-Smith, J.O.; Worobey, M.; Lowen, A.C.; Nelson, M.I. The Global H5N1 Influenza Panzootic in Mammals. Nature 2025, 637, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/2023.

- The Current Epidemic Situation in Russia and the World. Available online: https://www.rospotrebnadzor.ru/region/korono_virus/epid.php.

- World Health Organization Statement on the Fifteenth Meeting of the IHR (2005) Emergency Committee on the COVID-19 Pandemic. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/05-05-2023-statement-on-the-fifteenth-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)-pandemic.

- Inaida, S.; Paul, R.E.; Matsuno, S. Viral Transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2 Accelerates in the Winter, Similarly to Influenza Epidemics. American Journal of Infection Control 2022, 50, 1070–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, K.K.; Tay, D.J.W.; Tan, K.S.; Ong, S.W.X.; Than, T.S.; Koh, M.H.; Chin, Y.Q.; Nasir, H.; Mak, T.M.; Chu, J.J.H. Viral Load of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in Respiratory Aerosols Emitted by Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) While Breathing, Talking, and Singing. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2022, 74, 1722–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, V.T.; Tay, D.J.W.; Chen, M.I.; Tang, J.W.; Milton, D.K.; Tham, K.W. Influenza A and B Viruses in Fine Aerosols of Exhaled Breath Samples from Patients in Tropical Singapore. Viruses 2023, 15, 2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riou, J.; Althaus, C.L. Pattern of Early Human-to-Human Transmission of Wuhan 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV), December 2019 to January 2020. Eurosurveillance 2020, 25, 2000058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N.; Wang, L.; Deng, X.; Liang, R.; Su, M.; He, C.; Hu, L.; Su, Y.; Ren, J.; Yu, F. Recent Advances in the Detection of Respiratory Virus Infection in Humans. Journal of Medical Virology 2020, 92, 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorramdelazad, H.; Kazemi, M.H.; Najafi, A.; Keykhaee, M.; Emameh, R.Z.; Falak, R. Immunopathological Similarities between COVID-19 and Influenza: Investigating the Consequences of Co-Infection. Microbial Pathogenesis 2021, 152, 104554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golpour, M.; Jalali, H.; Alizadeh-Navaei, R.; Talarposhti, M.R.; Mousavi, T.; Ghara, A.A.N. Co-Infection of SARS-CoV-2 and Influenza A/B among Patients with COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Infectious Diseases 2025, 25, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alosaimi, B.; Naeem, A.; Hamed, M.E.; Alkadi, H.S.; Alanazi, T.; Al Rehily, S.S.; Almutairi, A.Z.; Zafar, A. Influenza Co-Infection Associated with Severity and Mortality in COVID-19 Patients. Virology Journal 2021, 18, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, H.; Zhang, M.; Xing, L.; Wang, K.; Rao, X.; Liu, H.; Tian, J.; Zhou, P.; Deng, Y.; Shang, J. The Epidemiology and Clinical Characteristics of Co-infection of SARS-CoV-2 and Influenza Viruses in Patients during COVID-19 Outbreak. Journal of Medical Virology 2020, 92, 2870–2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Kim, S.; Kim, H.; Gil, D.; Han, H.-J.; Thimmulappa, R.K.; Choi, J.-H.; Kim, J.-H. Reciprocal Enhancement of SARS-CoV-2 and Influenza Virus Replication in Human Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Lung Organoids. Emerging Microbes & Infections 2023, 12, 2211685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Lai, X.; Chen, Z.; Tu, S.; Qin, K. Clinical Characteristics of Critically Ill Patients Co-Infected with SARS-CoV-2 and the Influenza Virus in Wuhan, China. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2020, 96, 683–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization Co-administration of Seasonal Inactivated Influenza and COVID-19 Vaccines. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-vaccines-SAGE_recommendation-co-administration.

- Russian Ministry of Health The Russian Ministry of Health has authorized simultaneous vaccination against COVID-19 and influenza. Available online: https://minzdrav.gov.ru/news/2021/10/22/17665-minzdrav-rossii-razreshil-odnovremennuyu-vaktsinatsiyu-ot-kovida-i-grippa.

- Xie, Z.; Hamadi, H.Y.; Mainous, A.G.; Hong, Y.-R. Association of Dual COVID-19 and Seasonal Influenza Vaccination with COVID-19 Infection and Disease Severity. Vaccine 2023, 41, 875–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization Influenza and SARS-CoV-2 Virus Detections Reported to FluNet from Countries, Areas and Territories. Available online: https://app.powerbi.com/view?r=eyJrIjoiNzc4YTIxZjQtM2E1My00YjYxLWIxMDItNzEzMjkyY2E1MzU1IiwidCI6ImY2MTBjMGI3LWJkMjQtNGIzOS04MTBiLTNkYzI4MGFmYjU5MCIsImMiOjh9.

- Karpova, L.S.; Pelikh, M.Y.; Stolyarov, K.A.; Volik, K.M.; Stolyarova, T.P.; Danilenko, D.M. Analysis of Influenza Epidemics during the COVID-19 Pandemic Using an Improved Surveillance System (from 2021 to 2024). Journal of Microbiology, Epidemiology and Immunobiology 2024, 101, 679–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FluCov Dashboard Understanding the Impact of SARS-CoV-2 on Influenza. Available online: https://www.nivel.nl/en/dossier-epidemiology-respiratory-viruses/flucov-dashboard.

- World Health Organization Global Influenza Programme. Available online: https://www.who.int/tools/flunet.

- Takashita, E.; Watanabe, S.; Hasegawa, H.; Kawaoka, Y. Are Twindemics Occurring? Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses 2023, 17, e13090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opatowski, L.; Baguelin, M.; Eggo, R.M. Influenza Interaction with Cocirculating Pathogens and Its Impact on Surveillance, Pathogenesis, and Epidemic Profile: A Key Role for Mathematical Modelling. PLoS Pathogens 2018, 14, e1006770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinjoh, M.; Omoe, K.; Saito, N.; Matsuo, N.; Nerome, K. In Vitro Growth Profiles of Respiratory Syncytial Virus in the Presence of Influenza Virus. Acta Virologica 2000, 44, 91–97. [Google Scholar]

- Piret, J.; Boivin, G. Viral Interference between Respiratory Viruses. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2022, 28, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinky, L.; Dobrovolny, H.M. Coinfections of the Respiratory Tract: Viral Competition for Resources. PloS ONE 2016, 11, e0155589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzorno, A.; Padey, B.; Dulière, V.; Mouton, W.; Oliva, J.; Laurent, E.; Milesi, C.; Lina, B.; Traversier, A.; Julien, T. Interactions between Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Replication and Major Respiratory Viruses in Human Nasal Epithelium. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 2022, 226, 2095–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinky, L.; Dobrovolny, H.M. SARS-CoV-2 Coinfections: Could Influenza and the Common Cold Be Beneficial? Journal of Medical Virology 2020, 92, 2623–2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, L.; Zhao, Y.; Dong, J.; Liang, S.; Guo, M.; Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Huang, Z.; Sun, X.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Coinfection with Influenza A Virus Enhances SARS-CoV-2 Infectivity. Cell Research 2021, 31, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Y.J.; Okuda, K.; Edwards, C.E.; Martinez, D.R.; Asakura, T.; Dinnon, K.H.; Kato, T.; Lee, R.E.; Yount, B.L.; Mascenik, T.M.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Reverse Genetics Reveals a Variable Infection Gradient in the Respiratory Tract. Cell 2020, 182, 429–446.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibañez, L.; Martinez, V.; Iglesias, A.; Bellomo, C.; Alonso, D.; Coelho, R.; Martinez Peralta, L.; Periolo, N. Decreased Expression of Surfactant Protein-C and CD74 in Alveolar Epithelial Cells during Influenza Virus A(H1N1)Pdm09 and H3N2 Infection. Microbial Pathogenesis 2023, 176, 106017–106017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, C.G.K.; Allon, S.J.; Nyquist, S.K.; Mbano, I.M.; Miao, V.N.; Tzouanas, C.N.; Cao, Y.; Yousif, A.S.; Bals, J.; Hauser, B.M.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Receptor ACE2 Is an Interferon-Stimulated Gene in Human Airway Epithelial Cells and Is Detected in Specific Cell Subsets across Tissues. Cell 2020, 181, 1016–1035.e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, T.; Watanabe, K.; Sakurai, Y.; Nishi, K.; Yoshikawa, R.; Yasuda, J. Co-Infection of SARS-CoV-2 and Influenza Virus Causes More Severe and Prolonged Pneumonia in Hamsters. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 21259–21259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.J.; Lee, A.C.-Y.; Chan, J.F.-W.; Liu, F.; Li, C.; Chen, Y.; Chu, H.; Lau, S.-Y.; Wang, P.; Chan, C.C.-S.; et al. Coinfection by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 and Influenza A(H1N1)Pdm09 Virus Enhances the Severity of Pneumonia in Golden Syrian Hamsters. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2021, 72, e978–e992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, L.; Deng, W.; Qi, F.; Lv, Q.; Song, Z.; Liu, J.; Gao, H.; Wei, Q.; Yu, P.; Xu, Y.; et al. Sequential Infection with H1N1 and SARS-CoV-2 Aggravated COVID-19 Pathogenesis in a Mammalian Model, and Co-Vaccination as an Effective Method of Prevention of COVID-19 and Influenza. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2021, 6, 200–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Cai, Y.; Huang, X.; Yu, X.; Zhao, L.; Wang, F.; Li, Q.; Gu, S.; Xu, T.; Li, Y.; et al. Co-Infection with SARS-CoV-2 and Influenza A Virus in Patient with Pneumonia, China. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2020, 26, 1324–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadashi, M.; Khaleghnejad, S.; Abedi Elkhichi, P.; Goudarzi, M.; Goudarzi, H.; Taghavi, A.; Vaezjalali, M.; Hajikhani, B. COVID-19 and Influenza Co-Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Medicine 2021, 8, 681469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, X.; Wang, Z.; Ye, L.; He, X.; Wei, X.; Ma, Y.; Li, H.; Chen, L.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Q. Co-Infection of SARS-COV-2 and Influenza A Virus: A Case Series and Fast Review. Current Medical Science 2021, 41, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tam, J.S.; Shu, Y. Public Health Control Measures for the Co-Circulation of Influenza and SARS-CoV-2 During Influenza Seasons. China CDC Weekly 2022, 4, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Lai, X.; Chen, Z.; Tu, S.; Qin, K. Clinical Characteristics of Critically Ill Patients Co-Infected with SARS-CoV-2 and the Influenza Virus in Wuhan, China. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2020, 96, 683–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobucci, G. Covid-19: Risk of Death More than Doubled in People Who Also Had Flu, English Data Show. BMJ 2020, m3720–m3720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stowe, J.; Tessier, E.; Zhao, H.; Guy, R.; Muller-Pebody, B.; Zambon, M.; Andrews, N.; Ramsay, M.; Bernal, J.L. Interactions between SARS-CoV-2 and Influenza, and the Impact of Coinfection on Disease Severity: A Test-Negative Design. International Journal of Epidemiology 2021, 50, 1124–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørup, S.; Benn, C.S.; Poulsen, A.; Krause, T.G.; Aaby, P.; Ravn, H. Simultaneous Vaccination with MMR and DTaP-IPV-Hib and Rate of Hospital Admissions with Any Infections: A Nationwide Register Based Cohort Study. Vaccine 2016, 34, 6172–6180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansone, V.; Miraglia del Giudice, G.; Della Polla, G.; Angelillo, I.F. Simultaneous Vaccination against Seasonal Influenza and COVID-19 among the Target Population in Italy. Frontiers in Public Health 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudley, M.Z.; Salmon, D.A.; Halsey, N.A.; Orenstein, W.A.; Limaye, R.J.; O’Leary, S.T.; Omer, S.B. Do Combination Vaccines or Simultaneous Vaccination Increase the Risk of Adverse Events? In The Clinician’s Vaccine Safety Resource Guide; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018; pp. 157–165. [Google Scholar]

- Walter, E.B.; Schlaudecker, E.P.; Talaat, K.R.; Rountree, W.; Broder, K.R.; Duffy, J.; Grohskopf, L.A.; Poniewierski, M.S.; Spreng, R.L.; Staat, M.A.; et al. Safety of Simultaneous vs Sequential mRNA COVID-19 and Inactivated Influenza Vaccines: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Network Open 2024, 7, e2443166–e2443166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanni, P.; Steffen, R.; Schelling, J.; Balaisyte-Jazone, L.; Posiuniene, I.; Zatoński, M.; Van Damme, P. Vaccine Co-Administration in Adults: An Effective Way to Improve Vaccination Coverage. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics 2023, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decker, M.D. Combination Vaccines. In Clinics in Office Practice; Primary Care, 2001; Volume 28, pp. 739–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skibinski, D.; Baudner, B.; Singh, M.; O′Hagan, D. Combination Vaccines. Journal of Global Infectious Diseases 2011, 3, 63–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maman, K.; Zöllner, Y.; Greco, D.; Duru, G.; Sendyona, S.; Remy, V. The Value of Childhood Combination Vaccines: From Beliefs to Evidence. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics 2015, 11, 2132–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, R. Combined Vaccines Against COVID-19, Flu, and Other Respiratory Illnesses Could Soon Be Available. JAMA 2024, 331, 1880–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guess, H.A. Combination Vaccines: Issues in Evaluation of Effectiveness and Safety. Epidemiologic Reviews 1999, 21, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliman, D.; Bedford, H. Safety and Efficacy of Combination Vaccines: Combinations Reduce Distress and Are Efficacious and Safe. Bmj 2003, 326, 995–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halsey, N.A. Safety of Combination Vaccines: Perception versus Reality. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 2001, 20, S40–S44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafreshi, S.H. Efficacy, Safety, and Formulation Issues of the Combined Vaccines. Expert Review of Vaccines 2020, 19, 949–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.; Gulani, M.; Vijayanand, S.; Arte, T.; Adediran, E.; Pasupuleti, D.; Patel, P.; Ferguson, A.; Uddin, M.; Zughaier, S.M. An Intranasal Quadruple Variant Vaccine Approach Using SARS-CoV-2 and Influenza A: Delta, Omicron, H1N1and H3N2. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2025, 126043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaparian, R.R.; Harding, A.T.; Hamele, C.E.; Riebe, K.; Karlsson, A.; Sempowski, G.D.; Heaton, N.S.; Heaton, B.E. A Virion-Based Combination Vaccine Protects against Influenza and SARS-CoV-2 Disease in Mice. Journal of Virology 2022, 96, e00689-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, Z.; Shi, W.; Zhu, D.; Hu, S.; Dinh, P.-U.C.; Cheng, K. A SARS-CoV-2 and Influenza Double Hit Vaccine Based on RBD-Conjugated Inactivated Influenza A Virus. Science Advances 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Martinez, Z.V.; Alpuche-Lazcano, S.P.; Stuible, M.; Akache, B.; Renner, T.M.; Deschatelets, L.; Dudani, R.; Harrison, B.A.; McCluskie, M.J.; Hrapovic, S. SARS-CoV-2 Spike-Based Virus-like Particles Incorporate Influenza H1/N1 Antigens and Induce Dual Immunity in Mice. Vaccine 2024, 42, 126463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.; Zeng, J.; Xu, L.; Wang, F.; Duan, X.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Yu, D.; Huang, Q.; Yao, Y.-G.; et al. A Combination Vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 and H1N1 Influenza Based on Receptor Binding Domain Trimerized by Six-Helix Bundle Fusion Core. eBioMedicine 2022, 85, 104297–104297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 64 Huang, Y.; Shi, H.; Forgacs, D.; RossT, M. Flu-COVID Combo Recombinant Protein Vaccines Elicited Protective Immune Responses against Both Influenza and SARS-CoV-2 Viruses Infection. Vaccine 2024, 42, 1184–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasilnikov, I.; Isaev, A.; Djonovic, M.; Ivanov, A.; Romanovskaya-Romanko, E.; Stukova, M.; Zverev, V.; 65. Transformative Vaccination: A Pentavalent Shield against COVID-19 and Influenza with Betulin-Based Adjuvant for Enhanced Immunity. Vaccine 2024, 42, 2191–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Q.; Wu, M.; Zhou, C.; Lu, X.; Huang, B.; Zhang, N.; Zhao, H.; Chi, H.; Zhang, X.; Ling, D.; et al. Rational Development of a Combined mRNA Vaccine against COVID-19 and Influenza. npj Vaccines 2022, 7, 84–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Ma, Q.; Li, M.; Mai, Q.; Ma, L.; Zhang, H.; Zhong, H.; Mai, K.; Cheng, N.; Feng, P.; et al. A Decavalent Composite mRNA Vaccine against Both Influenza and COVID-19. mBio 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbad, A.; Yueh, J.; Yellin, T.; Singh, G.; Carreño, J.M.; Clark, J.J.; Muramatsu, H.; Tiwari, S.; Bhavsar, D.; Alzua, G.P. Co-Administration of Seasonal Quadrivalent Influenza and COVID-19 Vaccines Leads to Enhanced Immune Responses to Influenza Virus and Reduced Immune Responses to SARS-CoV-2 in Naive Mice. Vaccine 2025, 50, 126825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornhill-Wadolowski, E.; Ruter, D.L.; Yan, F.; Gajera, M.; Kurt, E.; Samanta, L.; Leigh, K.; Zhu, J.; Guo, Z.; Wang, Z. Development of an Influenza/COVID-19 Combination mRNA Vaccine Containing a Novel Multivalent Antigen Design That Enhances Immunogenicity of Influenza Virus B Hemagglutinins. Vaccines 2025, 13, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, N.; O’Connor, D.; Lambe, T.; Pollard, A.J. Viral Vector Vaccines. Current Opinion in Immunology 2022, 77, 102210–102210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasilyev, K.; Shurygina, A.-P.; Sergeeva, M.; Stukova, M.; Egorov, A. Intranasal Immunization with the Influenza A Virus Encoding Truncated NS1 Protein Protects Mice from Heterologous Challenge by Restraining the Inflammatory Response in the Lungs. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 690–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, K.; Wang, X.; Peng, H.; Ding, L.; Wang, X.; Hu, Y.; Dong, L.; Yang, T.; Hong, X.; Xing, M.; et al. A Single Vaccine Protects against SARS-CoV-2 and Influenza Virus in Mice. Journal of Virology 2022, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, M.; Hu, G.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; He, F.; Dai, W.; Wang, X.; Niu, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, H.; et al. An Intranasal Combination Vaccine Induces Systemic and Mucosal Immunity against COVID-19 and Influenza. npj Vaccines 2024, 9, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Arévalo, M.T.; Zeng, M. Engineering Influenza Viral Vectors. Bioengineered 2013, 4, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sastre, A.; Egorov, A.; Matassov, D.; Brandt, S.; Levy, D.E.; Durbin, J.E.; Palese, P.; Muster, T. Influenza A Virus Lacking the NS1 Gene Replicates in Interferon-Deficient Systems. Virology 1998, 252, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egorov, A.; Brandt, S.; Sereinig, S.; Romanova, J.; Ferko, B.; Katinger, D.; Grassauer, A.; Alexandrova, G.; Katinger, H.; Muster, T. Transfectant Influenza A Viruses with Long Deletions in the NS1 Protein Grow Efficiently in Vero Cells. Journal of Virology 1998, 72, 6437–6441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biosciences, V. Delta-19, Covid-19 + Universal Influenza Combination Vaccine. Available online: https://vivaldibiosciences.com/delta19.

- Sergeeva, M.V.; Vasilev, K.; Romanovskaya-Romanko, E.; Yolshin, N.; Pulkina, A.; Shamakova, D.; Shurygina, A.-P.; Muzhikyan, A.; Lioznov, D.; Stukova, M. Mucosal Immunization with an Influenza Vector Carrying SARS-CoV-2 N Protein Protects Naïve Mice and Prevents Disease Enhancement in Seropositive Th2-Prone Mice. Vaccines 2024, 13, 15–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Wang, P.; Yuan, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, H.; Chen, C.; Wang, X.; Han, J.; Chen, Y. A Live Attenuated Virus-Based Intranasal COVID-19 Vaccine Provides Rapid, Prolonged, and Broad Protection against SARS-CoV-2. Science bulletin 2022, 67, 1372–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Jiang, Y.; He, J.; Chen, J.; Qi, R.; Yuan, L.; Shao, T.; Zhao, H.; Chen, C.; Chen, Y. Intranasal Influenza-Vectored COVID-19 Vaccine Restrains the SARS-CoV-2 Inflammatory Response in Hamsters. Nature Communications 2023, 14, 4117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loes, A.N.; Gentles, L.E.; Greaney, A.J.; Crawford, K.H.; Bloom, J.D. Attenuated Influenza Virions Expressing the SARS-CoV-2 Receptor-Binding Domain Induce Neutralizing Antibodies in Mice. Viruses 2020, 12, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stepanova, E.; Matyushenko, V.; Mezhenskaya, D.; Bazhenova, E.; Kotomina, T.; Rak, A.; Donina, S.; Chistiakova, A.; Kostromitina, A.; Novitskaya, V. Safety, Immunogenicity and Protective Activity of a Modified Trivalent Live Attenuated Influenza Vaccine for Combined Protection Against Seasonal Influenza and COVID-19 in Golden Syrian Hamsters. Vaccines 2024, 12, 1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hause, A.M.; Zhang, B.; Yue, X.; Marquez, P.; Myers, T.R.; Parker, C.; Gee, J.; Su, J.; Shimabukuro, T.T.; Shay, D.K. Reactogenicity of Simultaneous COVID-19 mRNA Booster and Influenza Vaccination in the US. JAMA Network Open 2022, 5, e2222241–e2222241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izikson, R.; Brune, D.; Bolduc, J.-S.; Bourron, P.; Fournier, M.; Moore, T.M.; Pandey, A.; Perez, L.; Sater, N.; Shrestha, A.; et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of a High-Dose Quadrivalent Influenza Vaccine Administered Concomitantly with a Third Dose of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine in Adults Aged ≥65 Years: A Phase 2, Randomised, Open-Label Study. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine 2022, 10, 392–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, L.J.; Malhotra, D.; Miles, A.C.; Welch, V.L.; Di Fusco, M.; Surinach, A.; Barthel, A.; Alfred, T.; Jodar, L.; McLaughlin, J.M. Estimated Effectiveness of Co-administration of the BNT162b2 BA.4/5 COVID-19 Vaccine With Influenza Vaccine. JAMA Network Open 2023, 6, e2342151–e2342151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro, P.L.; Zhang, B.; Ennulat, C.; Harris, M.; McVey, R.; Woody, G.; Marquez, P.; McNeil, M.M.; Su, J.R. Safety of Co-Administration of mRNA COVID-19 and Seasonal Inactivated Influenza Vaccines in the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) during July 1, 2021–June 30, 2022. Vaccine 2023, 41, 1859–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toback, S.; Galiza, E.; Cosgrove, C.; Galloway, J.; Goodman, A.L.; Swift, P.A.; Rajaram, S.; Graves-Jones, A.; Edelman, J.; Burns, F.; et al. Safety, Immunogenicity, and Efficacy of a COVID-19 Vaccine (NVX-CoV2373) Co-Administered with Seasonal Influenza Vaccines: An Exploratory Substudy of a Randomised, Observer-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 3 Trial. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine 2022, 10, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarus, R.; Baos, S.; Cappel-Porter, H.; Carson-Stevens, A.; Clout, M.; Culliford, L.; Emmett, S.R.; Garstang, J.; Gbadamoshi, L.; Hallis, B.; et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of Concomitant Administration of COVID-19 Vaccines (ChAdOx1 or BNT162b2) with Seasonal Influenza Vaccines in Adults in the UK (ComFluCOV): A Multicentre, Randomised, Controlled, Phase 4 Trial. The Lancet 2021, 398, 2277–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venuto, R.; Giunta, I.; Cortese, R.; Denaro, F.; Pantò, G.; Privitera, A.; D’Amato, S.; Genovese, C.; La Fauci, V.; Fedele, F.; et al. The Importance of COVID-19/Influenza Vaccines Co-Administration: An Essential Public Health Tool. Infectious Disease Reports 2022, 14, 987–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascucci, D.; Lontano, A.; Regazzi, L.; Marziali, E.; Nurchis, M.C.; Raponi, M.; Vetrugno, G.; Moscato, U.; Cadeddu, C.; Laurenti, P. Co-Administration of SARS-CoV-2 and Influenza Vaccines in Healthcare Workers: Results of Two Vaccination Campaigns in a Large Teaching Hospital in Rome. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics 2023, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantino, C.; Mazzucco, W.; Conforto, A.; Cimino, L.; Pieri, A.; Rusignolo, S.; Bonaccorso, N.; Bravatà, F.; Pipitone, L.; Sciortino, M.; et al. Real-Life Experience on COVID-19 and Seasonal Influenza Vaccines Co-Administration in the Vaccination Hub of the University Hospital of Palermo, Italy. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics 2024, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagenhäuser, I.; Reusch, J.; Gabel, A.; Höhn, A.; Lâm, T.-T.; Almanzar, G.; Prelog, M.; Krone, L.B.; Frey, A.; Schubert-Unkmeir, A.; et al. Immunogenicity and Safety of Co-administration of COVID-19 and Influenza Vaccination. European Respiratory Journal 2023, 61, 2201390–2201390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonen, T.; Barda, N.; Asraf, K.; Joseph, G.; Weiss-Ottolenghi, Y.; Doolman, R.; Kreiss, Y.; Lustig, Y.; Regev-Yochay, G. Immunogenicity and Reactogenicity of Co-administration of COVID-19 and Influenza Vaccines. JAMA Network Open 2023, 6, e2332813–e2332813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdoch, L.; Quan, K.; Baber, J.A.; Ho, A.W.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, X.; Lu, C.; Cooper, D.; Koury, K.; Lockhart, S.P.; et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of the BNT162b2 Vaccine Coadministered with Seasonal Inactivated Influenza Vaccine in Adults. Infectious Diseases and Therapy 2023, 12, 2241–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ModernaTX; Inc. A Safety, Reactogenicity, and Immunogenicity Study of mRNA-1073 (COVID-19/Influenza) Vaccine in Adults 18 to 75 Years Old. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05375838.

- Lee, W.S.; Selva, K.J.; Audsley, J.; Kent, H. E.; Reynaldi, A.; Schlub, T. E.; Cromer, D.; Khoury, D. S.; Peck, H.; Aban, M.; et al. Randomized trial of same- versus opposite-arm coadministration of inactivated influenza and SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines. JCI Insight 2025, 10, e187075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boikos, C.; Schaible, K.; Nunez-Gonzalez, S.; Welch, V.; Hu, T.; Kyaw, M.H.; Choi, L.E.; Kamar, J.; Goebe, H.; McLaughlin, J. Co-Administration of BNT162b2 COVID-19 and Influenza Vaccines in Adults: A Global Systematic Review. Vaccines 2025, 13, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, C.; Mosnier, A.; Gavazzi, G.; Combadière, B.; Crépey, P.; Gaillat, J.; Launay, O.; Botelho-Nevers. Coadministration of seasonal influenza and COVID-19 vaccines: A systematic review of clinical studies. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics 2022, 18, 2131166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Hashimi, F.; Shuaib, S.E.; Bragazzi, N.L.; Chen, S.; Wu, J. COVID-19 Vaccine Timing and Co-Administration with Influenza Vaccines in Canada: A Systematic Review with Comparative Insights from G7 Countries. Vaccines (Basel) 2025, 13, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BioNTech, S.E. A Study to Evaluate the Safety, Tolerability, and Immunogenicity of a Combined Modified RNA Vaccine Candidate Against COVID-19 and Influenza. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06178991.

- ModernaTX; Inc. A Safety, Reactogenicity, and Immunogenicity Study of mRNA-1073 (COVID-19/Influenza) Vaccine in Adults 18 to 75 Years Old. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05375838.

- ModernaTX, Inc. A Study of mRNA-1083 (SARS-CoV-2 and Influenza) Vaccine in Healthy Adult Participants, ≥50 Years of Age. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06097273.

- GlaxoSmithKline. A Study of an Investigational Flu Seasonal/SARS-CoV-2 Combination Vaccine in Adults. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06680375.

- A Study to Evaluate the Safety and Immunogenicity of COVID-19 and Influenza Combination Vaccine (COVID-19). Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05519839.

- Zhu, F.; Zhuang, C.; Chu, K.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, H.; Huang, S.; et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a live-attenuated influenza virus vector-based intranasal SARSCoV-2 vaccine in adults: randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1 and 2 trials. Lancet Respir Med. 2022, 10, 749–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, F.; Huang, S.; Liu, X.; Chen, Q.; Zhuang, C.; Zhao, H.; Han, J.; Jaen, A. M.; Do, T. H.; Peter, J. G.; et al. Safety and efficacy of the intranasal spray SARS-CoV-2 vaccine dNS1-RBD: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2023, 11, 1075–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smorodintsev Research Institute of Influenza; Russia. Evalution of Corfluvec Vaccine for the Prevention of COVID-19 in Healthy Volunteers. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05696067.

| Vaccine | Platform | Composition | Administration route | Key results | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PiCoVacc/Flu vaccine | Inactivated SARS-CoV-2 Split-virion influenza Vaccine | Inactivated SARS-CoV-2 virus Split-virion influenza virus |

IP | Neutralizing antibodies Protection against SARS-CoV-2 and H1N1 infection |

[38] |

| Quadruple microparticulate vaccine | Inactivated viruses encapsulated into PLGA polymer microparticles | Inactivated SARS-CoV-2 Delta & Omicron variants. Inactivated Influenza A H1N1 & H3N2 variants. AddaVax adjuvant |

IN | Antigen-specific IgG (serum) and mucosal IgA (lung). Activation of cytotoxic (CD8+) and helper (CD4+) T-cells in lymph nodes and spleen. |

[59] |

| Chimeric Influenza virus | Live attenuated or inactivated virus | Chimeric virus in live attenuated or inactivated form displaying influenza HA and SARS-CoV-2 RBD on its envelope | IN, IM | Neutralizing antibodies Protection from lethal challenge with both pathogens in mice. |

[60] |

| Double-hit Flu-RBD vaccine |

VLP Vaccine | SARS-CoV-2 RBD conjugated onto inactivated influenza A virus |

IM | RBD-specific IgG2a and IgG1 Th1/Th2 balanced cellular immune response High protection efficacy against SARS-CoV-2 challenge in hamsters Strong neutralization activity against wild-type influenza A H1N1 inactivated virus in mice |

[61] |

| Trivalent S/H1/N1 enveloped VLP | VLP vaccine | Full length SARS-CoV-2 S-protein, H1N1 hemagglutinin (H1) and neur aminidase (N1) co-incorporated into enveloped VLP SLA Archaeosome adjuvant | IM | Specific IgG to S, H1, N1, and cellular immune responses stimulation | [62] |

| Self-assembling SARS-CoV-2 RBD-trimer and Influenza H1N1 HA1-trimer | Recombinant protein vaccine | SARS-CoV-2-RBD-trimer and HA1-trimer Liposomal saponin-based MA103 adjuvant |

IM | HAI for Influenza RBD-specific IgG Neutralizing antibody for SARS-CoV-2 Th1/Th2 balanced cellular immune response High protection efficacy against lethal SARS-CoV-2 and homogenous H1N1 influenza co-infection |

[63] |

| Flu-COVID combo vaccine | Recombinant protein vaccine | Truncated H1 and H3 hemagglutinin (aa 1–528) and SARS-CoV-2 S protein (aa 1–1213) AddaVax adjuvant |

IM | Neutralizing antibodies against both influenza and SARS-CoV-2 Specific IgGs against HA and S protein Protection from lethal challenge with both viruses in mice. |

[64] |

| Flu-COVID pentavalent vaccine | Recombinant protein vaccine | SARS-CoV-2 RBD fused with the Fc fragment of the human IgG hemagglutinin surface antigens of the viruses A/H1N1- pdm09, A/H3H2, B/Yamagata, B/Victoria Betulin-based adjuvant |

IM | RBD-specific and HA- specific IgG HAI for A/H1N1- pdm09, A/H3H2, B/Yamagata, B/Victoria viruses SARS-CoV-2 neutralization |

[65] |

| AR-CoV/IAV | mRNA-LNP | LNP-encapsulated mRNA encoding HA fromH1N1 and RBD from SARS-CoV-2 S protein | IM | Robust protective antibodies Antigen-specific cellular immune responses against SARS-CoV-2 and IAV Mice protection from coinfection with IAV and the SARS-CoV-2 Alpha and Delta variants |

[66] |

| FLUCOV-10 | mRNA- LNP | LNP-encapsulated mRNA encoding HA from H1N1 pdm09, H3N2, B/Victoria, B/Yamagata, H5N1, H7N9, S protein from four SARS-CoV-2 variants |

IM |

IgG antibodies, neutralizing antibodies, and antigen-specific cellular immune responses against all the vaccine-matched viruses of influenza and SARS-CoV-2

Complete protection in mouse models against both homologous and heterologous strains of influenza and SARS-CoV-2 |

[67] |

| QIV & BNT162b2 | QIV: split-virion vaccine BNT162b2: mRNA-LNP |

QIV: split-virion from 4 strains (A/H1N1, A/H3N2, B/Victoria, B/Yamagata) BNT162b2: LNP-encapsulated mRNA encoding SARS-CoV-2 S protein |

IM | HAI & Binding Antibody Titers (HA, NA) Binding & Neutralizing Antibody Titers Complete protection in mouse models against lethal challenge with either virus |

[68] |

| Influenza/COVID-19 Combination mRNA Vaccine | mRNA-LNP | LNP-encapsulated mRNA encoding: Influenza HA fusion proteins (dumbbell/trimer design with bacteriophage T4 foldon) from 4 strains (A/H1N1, A/H3N2, B/Victoria, B/Yamagata) SARS-CoV-2 RBD fusion protein (bivalent dumbbell). |

IM | Hemagglutination Inhibition (HAI) titers against A/H1N1, A/H3N2, B/Victoria, B/Yamagata. - SARS-CoV-2-specific: Neutralizing antibody titers against XBB.1.5 variant. |

[69] |

| AdC68-CoV/Flu | Vectored vaccine | Chimpanzee adenovirus 68 (AdC68) vector encoding SARS-CoV-2 RBD and H7N9 hemagglutinin | IM | Anti-H7 IgG Neutralizing antibody for SARS-CoV-2 Extensive RBD-specific T cell responses of splenocytes Protection against lethal SARS-CoV-2 challenge |

[72] |

| AdC68-HATRBD | Vectored Vaccine | Chimpanzee adenovirus 68 (AdC68) vector encoding SARS-CoV-2 RBD Beta-Alpha chimeric dimer and Omicron-Delta chimeric dimer, numerous SARS-CoV-2 T cell epitopes, and full-length HA of H1N1 pdm09 | IN | IgG, mucosal IgA, neutralizing antibodies, and memory T cells, protecting the mice from SARS-CoV-2 BA.5.2 and pandemic H1N1 infections. | [73] |

| Delta-19 | Vectored Vaccine | Influenza Delta NS1 vector expressesing key immunogenic proteins of SARS-CoV-2 and influenza viruses | IN | Neutralizing antibodies against SARS CoV-2 and Influenza viruses | [77] |

| FluVec-N | Vectored Vaccine | Influenza A/PR/8/34 (H1N1) vector carrying the SARS-CoV-2 N protein C terminal fragment (aa211–369) fused to the truncated NS1 gene |

IN | Neutralizing antibody for SARS-CoV-2 N-Protein Specific antibodies in BAL Virus-specific effector and resident CD8+ lymphocytes in lungs Reduced weight loss and viral load in the lungs following infection with the SARS-CoV-2 beta variant. |

[78] |

| dNS1-RBD Pneucolin | Vectored Vaccine | Live attenuated H1N1 pdm09 virus with NS1 gene replaced by SARS-CoV-2 RBD | IN | Local RBD-specific T cell response in the lung RBD-specific IgA and IgG response Attenuating pro-inflammatory cytokine levels post SARS-CoV-2 challenge, thereby reducing excess immune-induced tissue injury Cross-protection against H1N1 and H5N1 viruses |

[79,80] |

| ∆NA(RBD)-Flu | Vectored Vaccine | Influenza A/WSN/33 (H1N1) with H3 from A/Aichi/2/1968 and NA gene replaced by SARS-CoV-2 RBD |

IN | Neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 and Influenza virus | [81] |

| 3×LAIV/CoV-2 | Vectored Vaccine | Licensed trivalent LAIV with H1N1/H3N2 strains encoding conserved SARS-CoV-2 T-cell epitopes. B/Victoria strain is unmodified | IN | Serum antibodies specific to all three influenza strains Protection against challenge from either influenza strain and SARS-CoV-2 challenge. T-cell response to SARS-CoV-2 epitopes |

[82] |

| Vaccine | Target | Manufacturer | Group of Participants (age) |

Type of trial | Safety and reactogenicity profile | Immunogenicity | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NVX-CoV2373_ recombinant spike protein with matrix-M adjuvant |

SARS-CoV-2 |

Novavax |

Adult ≥18 (n = 15187) |

Clinical trial Phase 3 |

Safety- Local / Systemic Reaction–Adverse Events |

HAI for Seasonal Influenza A and B strains Anti-SARS-CoV-2-spike IgG |

[87] |

| Flucelvax Quadrivalent |

Influenza |

Seqirus |

|||||

| Fluad | |||||||

| COVID-19 mRNA booster vaccine | SARS-CoV-2 | Pfizer-BioNTech | ≥12 (n = 61390) |

Study on v-safe platform |

Safety–Local / Systemic Reaction |

N/A |

[83] |

| SIV | Influenza | N/A | |||||

| COVID-19 mRNA booster vaccine | SARS-CoV-2 | Moderna | ≥12 (n = 30633) |

||||

| SIV | Influenza | N/A | |||||

| mRNA-1273 | SARS-CoV-2 | Moderna |

Adult ≥65 (n = 306) |

Clinical trial Phase 2 |

Safety–Adverse Events | HAI for Seasonal Influenza A and B strains Anti-SARS-CoV-2-spike IgG |

[84] |

| Fluzone QIV-HD | Influenza | Sanofi Pasteur | |||||

| BNT162b2 BA.4/5 bivalent_mRNA | SARS-CoV-2 | Pfizer-BioNTech |

Adult ≥18 (n = 3442996) |

Retrospective comparative effectiveness study | Safety–Weighted hazard ratio | N/A |

[85] |

| SIV | Influenza | N/A | |||||

| COVID-19 mRNA booster vaccine | SARS-CoV-2 | N/A |

Median: 48 years (n = 2449) |

Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) | Safety–Adverse Events | N/A |

[86] |

| QIV | Influenza | ||||||

| ChAdOx1 |

SARS-CoV-2 |

Pfizer-BioNTech |

Adult ≥!8 years (n=679) |

Multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 4 trial ConFluCov study |

Safety- Local / Systemic Reaction–Adverse Events | HAI for Seasonal Influenza A and B strains Anti-SARS-CoV-2-spike IgG |

[88] |

| BNT162b2 | Pfizer-BioNTech | ||||||

| Adjuvanted TIV (FluAd (MF59) |

Influenza |

Seqirus

|

|||||

| Flucelvax QIV | Seqirus | ||||||

| Flublok Quadrivalent (QIVr) | Sanofi Pasteur | ||||||

| BNT162b2mRNA | SARS-CoV-2 | Pfizer-BioNTech |

Adult (n = 1231) |

Preference-based non-randomised controlled study | Safety |

Anti-SARS-CoV-2-spike IgG |

[92] |

| mRNA-1273 | SARS-CoV-2 | Moderna | |||||

| InfluvacTetra | Influenza | Abbott | |||||

| Omicron BA.4/BA.5–adapted bivalent_mRNA | SARS-CoV-2 | Pfizer-BioNTech |

Adult (n = 588) |

Prospective cohort study | Safety- Local / Systemic Reaction–Adverse Events |

Anti-SARS-CoV-2-spike IgG |

[93] |

| Influvac Tetra | Influenza | Abbott | |||||

| BNT162b2_mRNA | SARS-CoV-2 | Pfizer-BioNTech |

Adult 18–65 (n = 1134) |

Clinical trial Phase 3 |

Safety- Local / Systemic Reaction–Adverse Events | HAI for Seasonal Influenza A and B strains Anti-SARS-CoV-2-spike IgG |

[94] |

| Afluria Quad | Influenza | Seqirus | |||||

| mRNA-1273 | SARS-CoV-2 |

Moderna |

Adult 18-75 |

Clinical trial Phase 1/2 | Safety–Local / Systemic Reaction–Adverse Events | HAI for Seasonal Influenza A and B strains Titer of VAC62 Neutralizing Antibody for SARS-CoV-2 |

[95] |

| mRNA-1010 | Influenza | ||||||

| mRNA-1073 | SARS-CoV-2/influenza | ||||||

| Omicron XBB.1.5–containing COVID-19 mRNA booster vaccine (Spikevax) | SARS-CoV-2 | Moderna |

Adult (n=56) |

Open-label, randomized trial |

Safety- Local / Systemic Reaction–Adverse Events |

Neutralizing antibody, Anti-SARS-CoV-2-spike IgG |

[96] |

| Afluria Quad | Influenza | Seqirus | HAI for Seasonal Influenza H1, H3, and B-Vic |

| Vaccine | Manufacturer | Platform | Administration route | Type of trial | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combined modified RNA COVID-19 and Influenca vaccine |

Pfizer BioNTech |

mRNA LNP |

IM |

Phase 3 | [100] |

| Combined COVID-19 and Influenca mRNA 1073 |

Moderna |

mRNA LNP |

IM |

Phase 1,2 | [101] |

| Combined COVID-19 and Influenca mRNA 1083 |

Moderna |

mRNA LNP |

IM |

Phase 3 |

[102] |

| mRNA Flu/COVID-19 | GlaxoSmithKline | mRNA LNP | IM | Phase1 | [103] |

| qNIV/CoV2373 |

Novavax |

Nanoparticle vaccine |

IM | Phase 2 | [104] |

| dNS1-RBD, Pneucolin | Beijing Wantai Biological Pharmacy Enterprise | Vector vaccine |

IN |

Phase 1-3 | [105,106] |

| Corfluvec | Smorodintsev Research Institute of Influenza, Russia | Vector vaccine |

IN |

Phase 1,2 | [107] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.