Submitted:

14 January 2026

Posted:

14 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Data Sources

2.2.1. Primary Data Source: Epidemiological Surveillance

2.2.2. Hospital Discharge Data

2.2.3. Sociodemographic and Marginalization Data

2.2.4. Agricultural Census Data

2.2.5. Vaccination Coverage Data

2.2.6. Molecular Surveillance Data

2.2.7. Population Denominators

2.3. Data Linkage

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.4.1. Descriptive Analysis

2.4.2. Transmission Dynamics

2.4.3. Spatial Analysis

2.4.4. Social Determinants and Introduction Mechanism

2.4.5. Vaccination and Case Incidence

2.4.6. Complications and Risk Factors for Severity

2.4.7. Molecular Epidemiology

2.4.8. Software and Reproducibility

3. Results

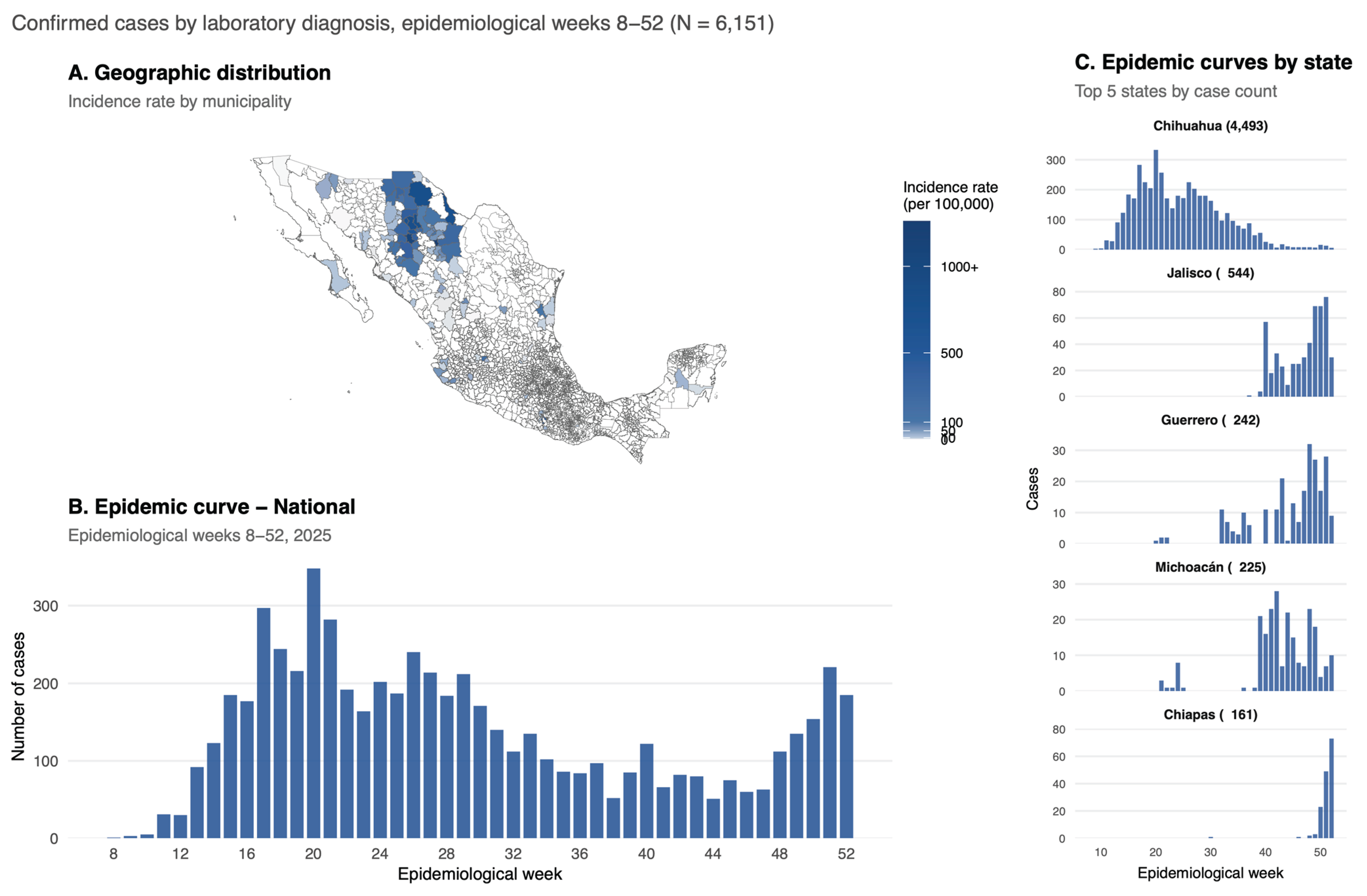

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

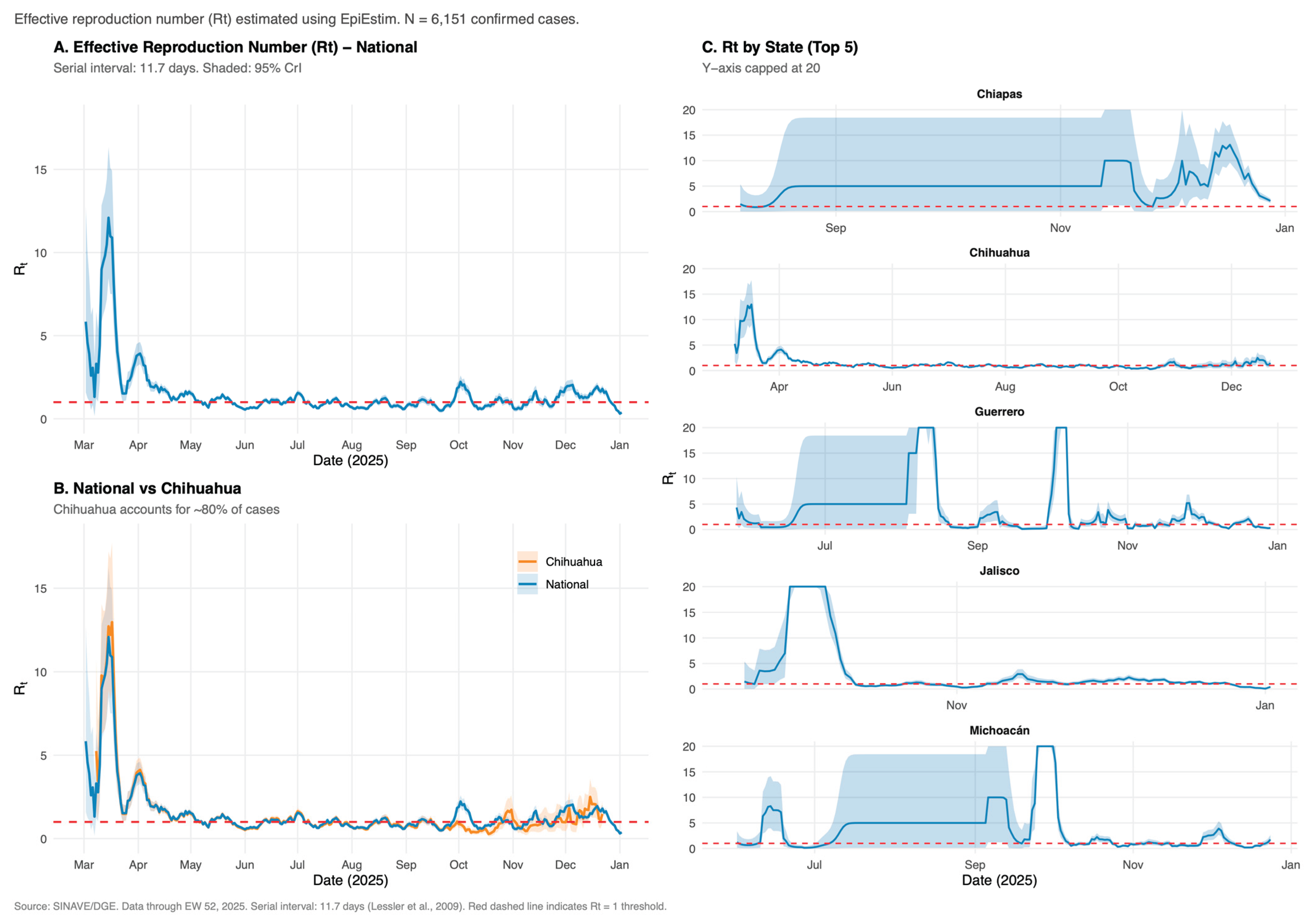

3.2. Transmission Dynamics

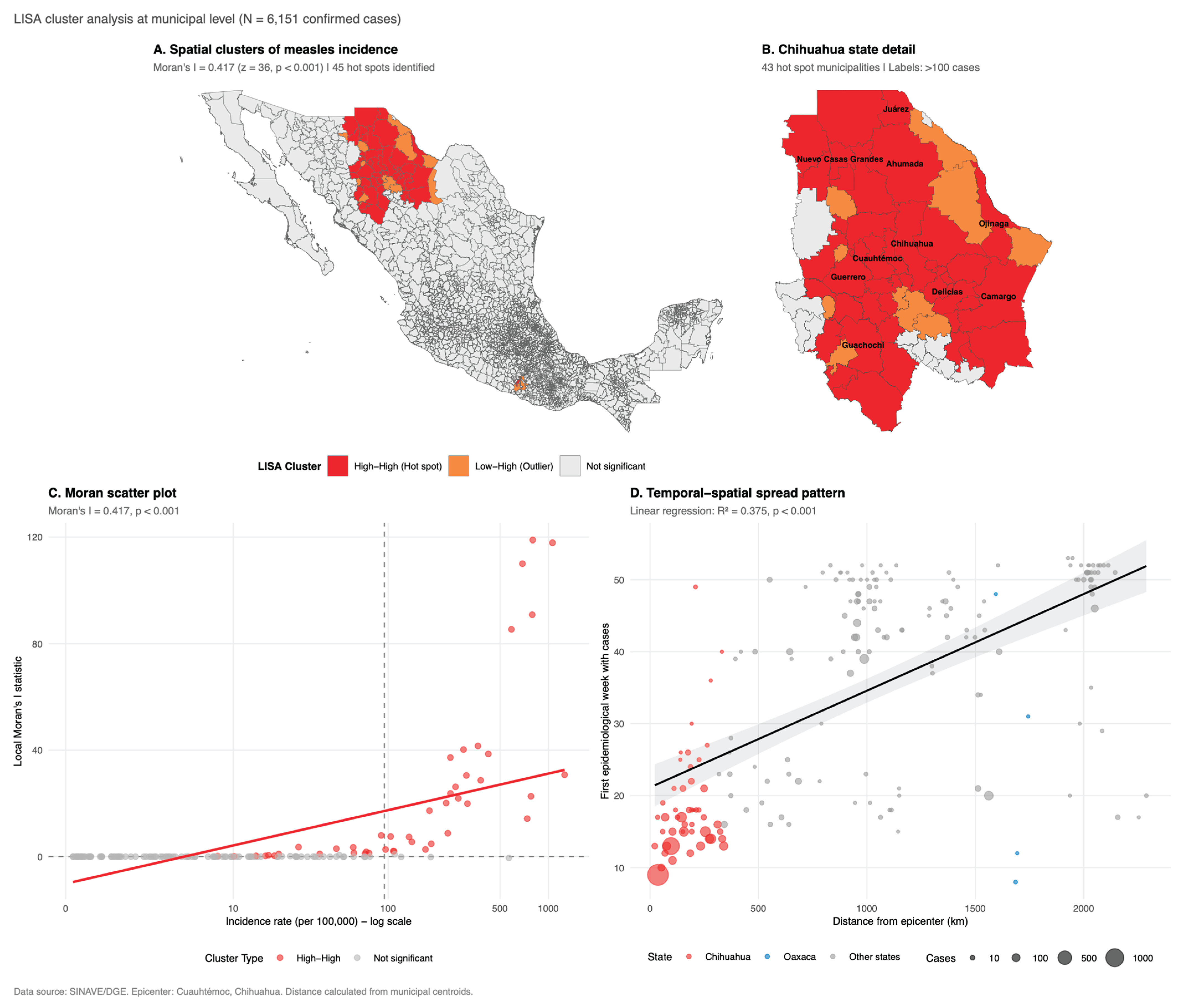

3.3. Spatial Analysis

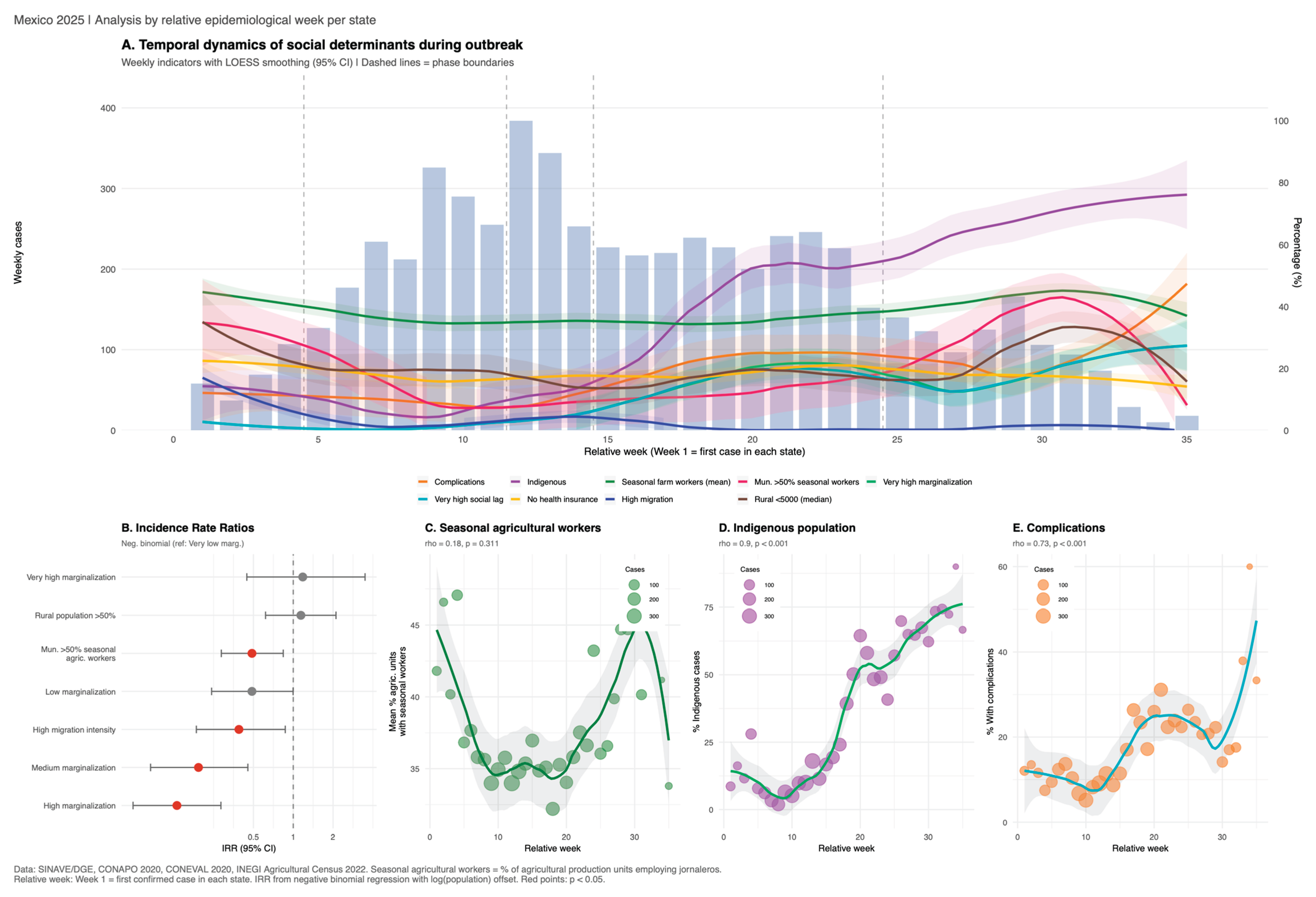

3.4. Social Determinants and Introduction Mechanism

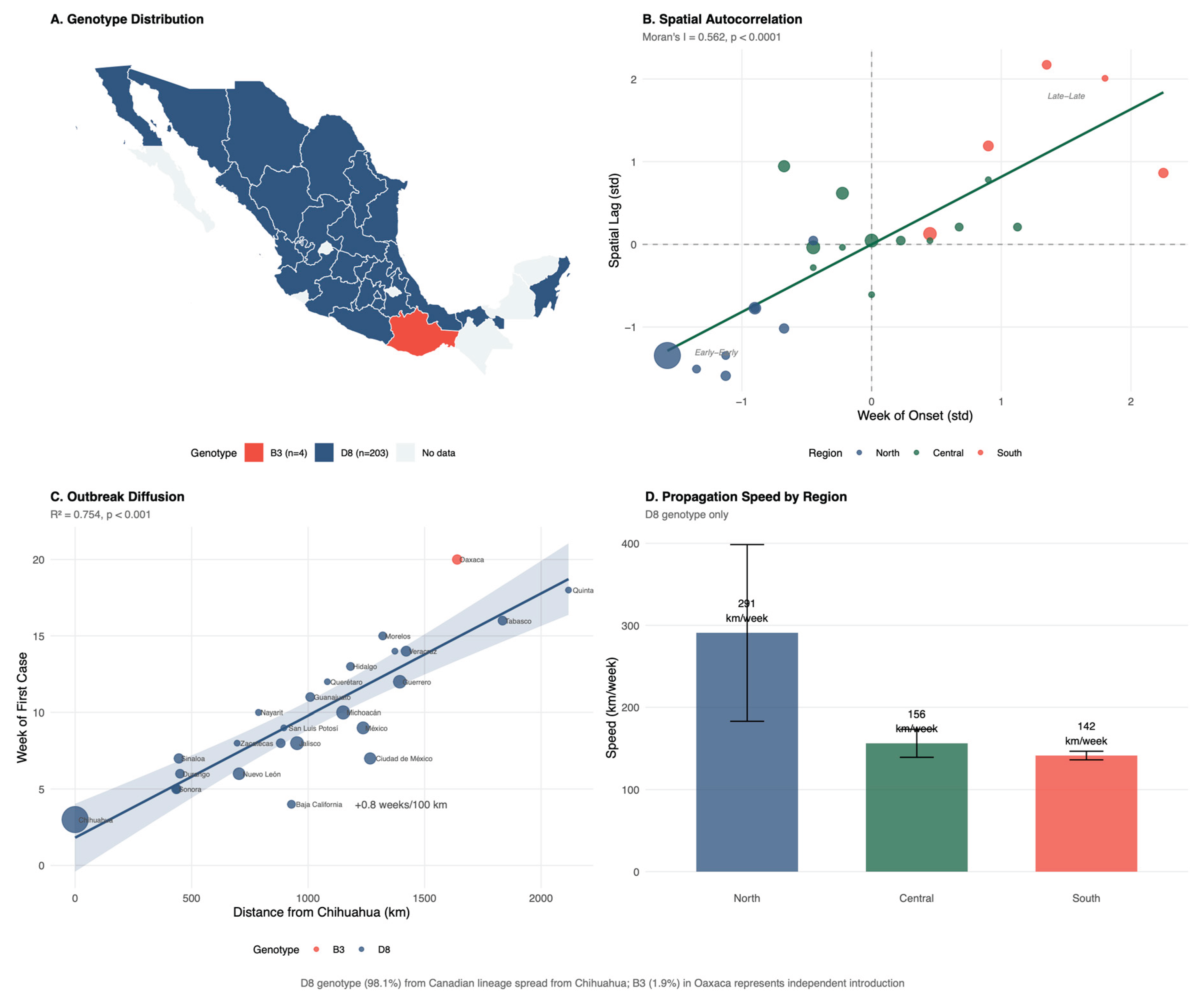

3.5. Vaccination and Vaccine Effectiveness (VE)

3.6. Complications and Risk Factors for Severity

3.6.1. Hospital Discharge Analysis

3.7. Molecular Epidemiology

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| aOR | Adjusted Odds Ratio |

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| CFR | Case Fatality Rate |

| CENSIA | Centro Nacional para la Salud de la Infancia y la Adolescencia (National Center for Child and Adolescent Health) |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| CONAPO | Consejo Nacional de Población (National Population Council) |

| CONEVAL | Consejo Nacional de Evaluación de la Pol√≠tica de Desarrollo Social (National Council for the Evaluation of Social Development Policy) |

| CrI | Credible Interval |

| DALYs | Disability-Adjusted Life Years |

| DGE | Dirección General de Epidemiología (General Directorate of Epidemiology) |

| DGIS | Dirección General de Informaci√≥n en Salud (General Directorate of Health Information) |

| EFEs | Sistema Especial de Vigilancia Epidemiológica de Enfermedades Febriles Exantem√°ticas (Special Surveillance System for Febrile Exanthematous Diseases) |

| ICD-10 | International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision |

| IgM | Immunoglobulin M |

| INEGI | Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (National Institute of Statistics and Geography) |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| IRR | Incidence Rate Ratio |

| LISA | Local Indicators of Spatial Association |

| LOESS | Locally Estimated Scatterplot Smoothing |

| MCV1 | Measles-Containing Vaccine First Dose |

| MMR | Measles-Mumps-Rubella (vaccine) |

| NCBI | National Center for Biotechnology Information |

| NOM | Norma Oficial Mexicana (Mexican Official Standard) |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| PAF | Population Attributable Fraction |

| PAHO | Pan American Health Organization |

| PCV | Proportion of Cases Vaccinated |

| PPV | Population Proportion Vaccinated |

| R0 | Basic Reproduction Number |

| RR | Relative Risk |

| RT-PCR | Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| Rt | Effective Reproduction Number |

| SAEH | Subsistema Automatizado de Egresos Hospitalarios (Automated Hospital Discharge Subsystem) |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SE | Semana Epidemiológica (Epidemiological Week) |

| SINAVE | Sistema Nacional de Vigilancia Epidemiológica (National Epidemiological Surveillance System) |

| VE | Vaccine Effectiveness |

| VIF | Variance Inflation Factor |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Do, L.A.H.; Mulholland, K. Measles 2025. New England Journal of Medicine 2025, 393, 2447–2458. [CrossRef]

- Stoneman, E.K. Measles. JAMA 2025, 334, 1665–1666. [CrossRef]

- Hübschen, J.M.; Gouandjika-Vasilache, I.; Dina, J. Measles. Lancet 2022, 399, 678–690. [CrossRef]

- Bester, J.C. Measles and Measles Vaccination: A Review. JAMA Pediatr 2016, 170, 1209–1215. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Du, M.; Deng, J.; Liu, M.; Liu, J. Global, Regional, and National Trends of Measles Burden and Its Vaccination Coverage among Children under 5 Years Old: An Updated Systematic Analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Int J Infect Dis 2025, 156, 107908. [CrossRef]

- Peltola, H. The History of Measles and Vaccine Development. Acta Paediatr 2025. [CrossRef]

- Laksono, B.M.; de Vries, R.D.; Verburgh, R.J.; Visser, E.G.; de Jong, A.; Fraaij, P.L.A.; Ruijs, W.L.M.; Nieuwenhuijse, D.F.; van den Ham, H.-J.; Koopmans, M.P.G.; et al. Studies into the Mechanism of Measles-Associated Immune Suppression during a Measles Outbreak in the Netherlands. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 4944. [CrossRef]

- Mina, M.J.; Kula, T.; Leng, Y.; Li, M.; de Vries, R.D.; Knip, M.; Siljander, H.; Rewers, M.; Choy, D.F.; Wilson, M.S.; et al. Measles Virus Infection Diminishes Preexisting Antibodies That Offer Protection from Other Pathogens. Science 2019, 366, 599–606. [CrossRef]

- Gastañaduy, P.A.; Goodson, J.L.; Panagiotakopoulos, L.; Rota, P.A.; Orenstein, W.A.; Patel, M. Measles in the 21st Century: Progress Toward Achieving and Sustaining Elimination. J Infect Dis 2021, 224, S420–S428. [CrossRef]

- Mattingly, T.J. Penny Wise, Pound Foolish: The Cost of Reduced Support for Measles Prevention. Vaccine 2025, 65, 127830. [CrossRef]

- Local Burden of Disease Vaccine Coverage Collaborators Mapping Routine Measles Vaccination in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Nature 2021, 589, 415–419. [CrossRef]

- Masresha, B.G.; Hatcher, C.; Lebo, E.; Tanifum, P.; Bwaka, A.M.; Minta, A.A.; Antoni, S.; Grant, G.B.; Perry, R.T.; O’Connor, P. Progress Toward Measles Elimination - African Region, 2017-2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2023, 72, 985–991. [CrossRef]

- Guerra, F.M.; Bolotin, S.; Lim, G.; Heffernan, J.; Deeks, S.L.; Li, Y.; Crowcroft, N.S. The Basic Reproduction Number (R0) of Measles: A Systematic Review. Lancet Infect Dis 2017, 17, e420–e428. [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.E.; Danovaro-Holliday, M.C.; Mwinnyaa, G.; Gacic-Dobo, M.; Francis, L.; Grevendonk, J.; Nedelec, Y.; Wallace, A.; Sodha, S.V.; Sugerman, C. Routine Vaccination Coverage - Worldwide, 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2024, 73, 978–984. [CrossRef]

- Marziano, V.; Bella, A.; Menegale, F.; Del Manso, M.; Petrone, D.; Palamara, A.T.; Pezzotti, P.; Merler, S.; Filia, A.; Poletti, P. Estimating Measles Susceptibility and Transmission Patterns in Italy: An Epidemiological Assessment. Lancet Infect Dis 2025, 25, 1303–1313. [CrossRef]

- Filia, A.; Del Manso, M.; Petrone, D.; Magurano, F.; Gioacchini, S.; Pezzotti, P.; Palamara, A.T.; Bella, A. Surge in Measles Cases in Italy from August 2023 to January 2025: Characteristics of Cases and Public Health Relevance. Vaccines (Basel) 2025, 13, 663. [CrossRef]

- Rey-Benito, G.; Pastor, D.; Whittembury, A.; Durón, R.; Pacis-Tirso, C.; Bravo-Alcántara, P.; Ortiz, C.; Andrus, J. Sustaining the Elimination of Measles, Rubella and Congenital Rubella Syndrome in the Americas, 2019-2023: From Challenges to Opportunities. Vaccines (Basel) 2024, 12, 690. [CrossRef]

- Carnalla, M.; Gaspar-Castillo, C.; Dimas-González, J.; Aparicio-Antonio, R.; Justo-Berrueta, P.S.; López-Martínez, I.; Shamah-Levy, T.; Lazcano-Ponce, E.; Barrientos-Gutiérrez, T.; Alpuche-Aranda, C.M.; et al. A Population-Based Measles Serosurvey in Mexico: Implications for Re-Emergence. Vaccine 2025, 51, 126886. [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.I.; Nakamura, M.A.; Godoy, M.V.; Kuri, P.; Lucas, C.A.; Conyer, R.T. Measles in Mexico, 1941-2001: Interruption of Endemic Transmission and Lessons Learned. J Infect Dis 2004, 189 Suppl 1, S243-250. [CrossRef]

- Hersh, B.S.; Tambini, G.; Nogueira, A.C.; Carrasco, P.; de Quadros, C.A. Review of Regional Measles Surveillance Data in the Americas, 1996-99. Lancet 2000, 355, 1943–1948. [CrossRef]

- Masters, N.B.; Eisenberg, M.C.; Delamater, P.L.; Kay, M.; Boulton, M.L.; Zelner, J. Fine-Scale Spatial Clustering of Measles Nonvaccination That Increases Outbreak Potential Is Obscured by Aggregated Reporting Data. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117, 28506–28514. [CrossRef]

- Robert, A.; Kucharski, A.J.; Funk, S. The Impact of Local Vaccine Coverage and Recent Incidence on Measles Transmission in France between 2009 and 2018. BMC Med 2022, 20, 77. [CrossRef]

- Rivadeneira, M.F.; Bassanesi, S.L.; Fuchs, S.C. Socioeconomic Inequalities and Measles Immunization Coverage in Ecuador: A Spatial Analysis. Vaccine 2018, 36, 5251–5257. [CrossRef]

- Fene, F.; Johri, M.; Michel, M.E.; Reyes-Morales, H.; Pelcastre-Villafuerte, B.E. Multiple Deprivations as Drivers of Suboptimal Basic Child Vaccination in Latin America and the Caribbean: Cross-Sectional Analysis of Household Survey Data for 18,136 Children across 211 Regions in 15 Countries. Int J Equity Health 2025, 24, 184. [CrossRef]

- Secretaría de Salud Datos Abiertos - Dirección General de Epidemiología [Internet] 2025.

- Salud, S. de Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM017 SSA2 2012 y Manuales para la Vigilancia Epidemiológica Available online: http://www.gob.mx/salud/documentos/manuales-para-la-vigilancia-epidemiologica-102563 (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Lineamientos Para La Vigilancia Por Laboratorio de La Enfermedad Febril Exantemática.

- Egresos Hospitalarios Available online: http://dgis.salud.gob.mx/contenidos/basesdedatos/bdc_egresoshosp_gobmx.html (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Índices de Marginación - Base de Datos - Datos.Gob.Mx Available online: https://datos.gob.mx/dataset/indices_marginacion (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Índice Rezago Social 2020 Available online: https://www.coneval.org.mx/Medicion/IRS/Paginas/Indice_Rezago_Social_2020.aspx (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Población, C.N. de Índices de intensidad migratoria México-Estados Unidos 2020 Available online: http://www.gob.mx/conapo/documentos/indices-de-intensidad-migratoria-mexico-estados-unidos-2020 (accessed on 11 January 2026).

- Geografía(INEGI), I.N. de E. y Censo Agropecuario (CA) 2022 Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/ca/2022/#datos_abiertos (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Catálogo Nacional de Indicadores Available online: https://www.snieg.mx/cni/escenario.aspx?idOrden=1.4&ind=6300000008&gen=143&d=n (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- GenBank Overview Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/ (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Salud, S. de BoletínEpidemiológico Sistema Nacional de Vigilancia Epidemiológica Sistema Único de Información Available online: http://www.gob.mx/salud/documentos/boletinepidemiologico-sistema-nacional-de-vigilancia-epidemiologica-sistema-unico-de-informacion (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Plataforma Nacional de Datos Abiertos Available online: https://www.datos.gob.mx (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Lessler, J.; Reich, N.G.; Brookmeyer, R.; Perl, T.M.; Nelson, K.E.; Cummings, D.A.T. Incubation Periods of Acute Respiratory Viral Infections: A Systematic Review. Lancet Infect Dis 2009, 9, 291–300. [CrossRef]

- PAHO Calls for Regional Action as the Americas Lose Measles Elimination Status - PAHO/WHO | Pan American Health Organization Available online: https://www.paho.org/en/news/10-11-2025-paho-calls-regional-action-americas-lose-measles-elimination-status?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 11 January 2026).

- Grenfell, B.T.; Bjørnstad, O.N.; Kappey, J. Travelling Waves and Spatial Hierarchies in Measles Epidemics. Nature 2001, 414, 716–723. [CrossRef]

- Rivadeneira, M.F.; Bassanesi, S.L.; Fuchs, S.C. Role of Health Determinants in a Measles Outbreak in Ecuador: A Case-Control Study with Aggregated Data. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 269. [CrossRef]

- Ten Countries in the Americas Report Measles Outbreaks in 2025 - PAHO/WHO | Pan American Health Organization Available online: https://www.paho.org/en/news/15-8-2025-ten-countries-americas-report-measles-outbreaks-2025 (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- Lanke, R.; Chimurkar, V. Measles Outbreak in Socioeconomically Diverse Sections: A Review. Cureus 16, e62879. [CrossRef]

- Pasadyn, F.; Mamo, N.; Caplan, A. Battling Measles: Shifting Strategies to Meet Emerging Challenges and Inequities. Ethics, Medicine and Public Health 2025, 33, 101047. [CrossRef]

- Mathis, A.D. Measles Update — United States, January 1–April 17, 2025. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2025, 74. [CrossRef]

- Measles Outbreak – August 12, 2025 | Texas DSHS Available online: https://www.dshs.texas.gov/news-alerts/measles-outbreak-2025?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 11 January 2026).

- Hewitt, G.-L.; Obeid, A.; Fischer, P.R. Measles Outbreaks in the United States in 2025: Practice, Policy, and the Canary in the Coalmine. New Microbes New Infect 2025, 65, 101591. [CrossRef]

- Sbarra, A.N.; Rolfe, S.; Nguyen, J.Q.; Earl, L.; Galles, N.C.; Marks, A.; Abbas, K.M.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Abbastabar, H.; Abd-Allah, F.; et al. Mapping Routine Measles Vaccination in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Nature 2021, 589, 415–419. [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Chihuahua N = 44931 |

Other States N = 16581 |

Total N = 61511 |

p-value2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 20 (4, 31) | 11 (4, 23) | 17 (4, 29) | <0.001 |

| Age group | <0.001 | |||

| <1 year | 490 (10.9%) | 151 (9.1%) | 641 (10.4%) | |

| 1-4 years | 642 (14.3%) | 300 (18.1%) | 942 (15.3%) | |

| 5-9 years | 381 (8.5%) | 299 (18.0%) | 680 (11.1%) | |

| 10-19 years | 683 (15.2%) | 411 (24.8%) | 1094 (17.8%) | |

| 20-39 years | 1865 (41.5%) | 414 (25.0%) | 2279 (37.1%) | |

| ≥40 years | 432 (9.6%) | 83 (5.0%) | 515 (8.4%) | |

| Sex | 0.036 | |||

| Female | 2158 (48.0%) | 847 (51.1%) | 3,005 (48.9%) | |

| Male | 2335 (52.0%) | 811 (48.9%) | 3,146 (51.1%) | |

| Vaccination status | <0.001 | |||

| Unvaccinated | 3907 (87.0%) | 1,376 (83.0%) | 5283 (85.9%) | |

| Vaccinated | 586 (13.0%) | 282 (17.0%) | 868 (14.1%) | |

| Indigenous status | 1246 (27.7%) | 639 (38.5%) | 1885 (30.6%) | <0.001 |

| Case origin | <0.001 | |||

| Import-related | 3515 (78.2%) | 386 (23.3%) | 3901 (63.4%) | |

| Imported | 9 (0.2%) | 209 (12.6%) | 218 (3.5%) | |

| Unknown source | 969 (21.6%) | 1,063 (64.1%) | 2032 (33.0%) | |

| Complications | 859 (19.1%) | 147 (8.9%) | 1006 (16.4%) | <0.001 |

| Death | 23 (0.5%) | 2 (0.1%) | 25 (0.4%) | 0.056 |

| Municipality status | ||||

| Variable |

Overall N = 24691 |

No cases N = 22501 |

With cases N = 2191 |

p-value2 |

| Population | <0.001 | |||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 13,552.0 (4489.0, 35,284.0) | 12,290.0 (4128.0, 30,639.0) | 39,656.5 (16,621.0, 149,684.5) | |

| Mean (SD) | 51,038.5 (146,990.7) | 39,476.0 (114,285.1) | 171,641.6 (308,543.3) | |

| Marginalization Index (0-100) | <0.001 | |||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 0.9 (0.8, 0.9) | 0.8 (0.8, 0.9) | 0.9 (0.8, 0.9) | |

| Mean (SD) | 0.8 (0.1) | 0.8 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.1) | |

| Marginalization Degree | <0.001 | |||

| Very low | 655 (26.5%) | 544 (24.1%) | 111 (51.4%) | |

| Low | 530 (21.5%) | 493 (21.9%) | 37 (17.1%) | |

| Medium | 494 (20.0%) | 473 (21.0%) | 21 (9.7%) | |

| High | 586 (23.7%) | 567 (25.2%) | 19 (8.8%) | |

| Very high | 204 (8.3%) | 176 (7.8%) | 28 (13.0%) | |

| Illiteracy rate (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 8.2 (4.4, 13.8) | 8.4 (4.7, 13.9) | 5.1 (2.7, 10.4) | |

| Mean (SD) | 10.2 (7.6) | 10.3 (7.5) | 8.8 (9.1) | |

| No basic education (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 46.3 (35.7, 55.9) | 46.8 (36.2, 56.0) | 41.7 (28.9, 53.8) | |

| Mean (SD) | 45.9 (14.0) | 46.2 (13.6) | 42.6 (17.0) | |

| Income <2 min wages (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 84.6 (74.6, 91.6) | 85.5 (76.2, 91.9) | 73.8 (63.3, 82.9) | |

| Mean (SD) | 82.1 (11.8) | 83.0 (11.3) | 73.6 (14.0) | |

| No drainage (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 1.4 (0.7, 3.3) | 1.5 (0.7, 3.4) | 0.9 (0.3, 2.5) | |

| Mean (SD) | 3.2 (5.3) | 3.1 (5.0) | 3.6 (7.8) | |

| No electricity (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 0.8 (0.4, 1.7) | 0.8 (0.4, 1.7) | 0.5 (0.2, 1.3) | |

| Mean (SD) | 1.5 (2.8) | 1.4 (2.0) | 2.4 (6.6) | |

| No piped water (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 2.5 (0.9, 7.3) | 2.6 (0.9, 7.3) | 1.6 (0.5, 6.1) | |

| Mean (SD) | 6.1 (9.2) | 6.2 (9.3) | 5.4 (8.7) | |

| Dirt floor (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 4.7 (1.7, 11.0) | 4.9 (1.8, 11.2) | 2.4 (1.0, 7.2) | |

| Mean (SD) | 8.0 (9.0) | 8.1 (8.8) | 7.1 (10.5) | |

| No health insurance (%) | 0.142 | |||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 22.6 (16.2, 30.6) | 22.7 (16.3, 30.7) | 20.7 (15.9, 29.3) | |

| Mean (SD) | 24.1 (10.8) | 24.2 (10.8) | 23.3 (10.6) | |

| Social Lag Index | <0.001 | |||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | -0.2 (-0.8, 0.5) | -0.2 (-0.7, 0.5) | -0.7 (-1.0, 0.0) | |

| Mean (SD) | 0.0 (1.0) | 0.0 (1.0) | -0.2 (1.4) | |

| Social Lag Degree | <0.001 | |||

| Very low | 677 (27.4%) | 568 (25.2%) | 109 (50.5%) | |

| Low | 893 (36.2%) | 836 (37.1%) | 57 (26.4%) | |

| Medium | 504 (20.4%) | 489 (21.7%) | 15 (6.9%) | |

| High | 243 (9.8%) | 233 (10.3%) | 10 (4.6%) | |

| Very high | 152 (6.2%) | 127 (5.6%) | 25 (11.6%) | |

| Rural population (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 100.0 (40.1, 100.0) | 100.0 (42.9, 100.0) | 43.5 (15.0, 93.7) | |

| Mean (SD) | 69.9 (35.3) | 71.9 (34.5) | 48.8 (35.9) | |

| Overcrowding (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 25.0 (18.7, 32.8) | 25.4 (19.2, 33.0) | 20.0 (14.0, 29.6) | |

| Mean (SD) | 26.6 (10.6) | 26.8 (10.3) | 23.7 (13.1) | |

| Households with remittances (%) | 0.176 | |||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 5.8 (2.6, 12.9) | 5.8 (2.6, 13.2) | 5.6 (2.3, 10.9) | |

| Mean (SD) | 9.0 (8.7) | 9.1 (8.9) | 7.5 (6.3) | |

| Migration Intensity Index | 0.252 | |||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 63.9 (62.2, 64.7) | 63.9 (62.1, 64.7) | 63.9 (62.6, 64.7) | |

| Mean (SD) | 63.1 (2.1) | 63.1 (2.2) | 63.5 (1.5) | |

| Migration Intensity Degree | 0.002 | |||

| None | 12 (0.5%) | 12 (0.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Very low | 861 (34.9%) | 789 (35.0%) | 72 (33.3%) | |

| Low | 686 (27.8%) | 610 (27.1%) | 76 (35.2%) | |

| Medium | 432 (17.5%) | 387 (17.2%) | 45 (20.8%) | |

| High | 341 (13.8%) | 320 (14.2%) | 21 (9.7%) | |

| Very high | 137 (5.5%) | 135 (6.0%) | 2 (0.9%) | |

| Agricultural units with day laborers (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 47.7 (36.4, 59.3) | 48.1 (37.0, 60.0) | 41.7 (32.2, 53.1) | |

| Mean (SD) | 47.6 (16.6) | 48.0 (16.6) | 42.8 (15.8) | |

| Day laborers tertile | <0.001 | |||

| T1 (Low) | 818 (33.3%) | 718 (32.0%) | 100 (47.4%) | |

| T2 (Medium) | 818 (33.3%) | 755 (33.7%) | 63 (29.9%) | |

| T3 (High) | 818 (33.3%) | 770 (34.3%) | 48 (22.7%) | |

| 1n (%).2Wilcoxon rank sum test; Pearson's Chi-squared test | ||||

| Outbreak phase (relative weeks per state) | |||||||

| Variable |

Overall N = 61511 |

Introduction (Rel Wk 1-4) N = 2721 |

Growth (Rel Wk 5-11) N = 16121 |

Peak (Rel Wk 12-14) N = 9801 |

Decline (Rel Wk 15-24) N = 21941 |

Late (Rel Wk 25+) N = 10931 |

p-value2 |

| Age (years) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 17.0 (4.0, 29.0) | 10.0 (3.0, 21.0) | 22.0 (8.0, 31.0) | 22.0 (7.0, 32.0) | 15.0 (3.0, 28.0) | 11.0 (2.0, 23.0) | |

| Mean (SD) | 18.1 (14.6) | 13.9 (13.0) | 21.2 (14.5) | 21.3 (15.0) | 16.9 (14.4) | 14.2 (13.3) | |

| Sex | 0.166 | ||||||

| Female | 3146 (51%) | 132 (48%) | 842 (52%) | 528 (54%) | 1116 (51%) | 528 (49%) | |

| Male | 3005 (49%) | 142 (52%) | 779 (48%) | 453 (46%) | 1079 (49%) | 552 (51%) | |

| Unvaccinated | 0.011 | ||||||

| FALSE | 868 (14%) | 40 (15%) | 228 (14%) | 171 (17%) | 277 (13%) | 152 (14%) | |

| TRUE | 5283 (86%) | 234 (85%) | 1393 (86%) | 810 (83%) | 1918 (87%) | 928 (86%) | |

| Indigenous | <0.001 | ||||||

| FALSE | 4,266 (69%) | 225 (82%) | 1527 (94%) | 852 (87%) | 1293 (59%) | 369 (34%) | |

| TRUE | 1885 (31%) | 49 (17.6%) | 94 (5.6%) | 129 (13.1%) | 902 (41.1%) | 711 (65.4%) | |

| Complications | <0.001 | ||||||

| FALSE | 5145 (84%) | 246 (90%) | 1475 (91%) | 885 (90%) | 1709 (78%) | 830 (77%) | |

| TRUE | 1006 (16%) | 28 (9.9%) | 146 (9.0%) | 96 (9.8%) | 486 (22%) | 250 (22.9%) | |

| Death | 0.068 | ||||||

| FALSE | 6126 (100%) | 274 (100%) | 1616 (100%) | 980 (100%) | 2185 (100%) | 1071 (99%) | |

| TRUE | 25 (0.4%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (0.3%) | 1 (0.1%) | 10 (0.5%) | 9 (0.8%) | |

| Marginalization Index (0-100)* | <0.001 | ||||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 0.9 (0.9, 0.9) | 0.9 (0.9, 0.9) | 0.9 (0.9, 0.9) | 0.9 (0.9, 0.9) | 0.9 (0.9, 0.9) | 0.9 (0.9, 0.9) | |

| Mean (SD) | 0.9 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.0) | 0.9 (0.0) | 0.9 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.1) | |

| Marginalization Degree* | <0.001 | ||||||

| Very low | 4626 (75%) | 218 (80%) | 1505 (93%) | 859 (88%) | 1398 (64%) | 646 (60%) | |

| Low | 604 (9.8%) | 33 (12%) | 83 (5.1%) | 46 (4.7%) | 311 (14%) | 131 (12%) | |

| Medium | 105 (1.7%) | 13 (4.8%) | 7 (0.4%) | 3 (0.3%) | 17 (0.8%) | 65 (6.0%) | |

| High | 184 (3.0%) | 3 (1.1%) | 11 (0.7%) | 25 (2.5%) | 98 (4.5%) | 47 (4.4%) | |

| Very high | 629 (10%) | 4 (1.5%) | 15 (0.9%) | 48 (4.9%) | 371 (17%) | 191 (18%) | |

| Illiteracy rate (%)* | <0.001 | ||||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 1.9 (1.8, 4.8) | 3.0 (1.8, 6.4) | 1.8 (1.8, 3.0) | 1.8 (1.7, 2.6) | 2.6 (1.8, 9.1) | 3.0 (1.9, 9.7) | |

| Mean (SD) | 5.8 (8.7) | 4.7 (4.9) | 2.7 (2.8) | 3.8 (6.6) | 7.7 (10.2) | 8.8 (11.4) | |

| No basic education (%)* | <0.001 | ||||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 35.3 (25.5, 48.2) | 37.5 (32.3, 45.6) | 35.3 (28.5, 39.5) | 35.3 (24.0, 39.5) | 35.3 (26.9, 55.1) | 35.8 (24.2, 58.0) | |

| Mean (SD) | 38.0 (16.3) | 39.8 (14.8) | 35.6 (13.4) | 34.2 (13.6) | 40.4 (17.8) | 39.6 (18.6) | |

| Income <2 min wages (%)* | <0.001 | ||||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 63.0 (51.3, 77.0) | 66.0 (55.0, 76.1) | 51.3 (51.3, 66.0) | 51.3 (51.3, 69.3) | 68.9 (51.3, 81.6) | 70.3 (59.8, 81.9) | |

| Mean (SD) | 63.4 (15.5) | 66.5 (11.9) | 57.7 (12.2) | 58.7 (13.8) | 66.5 (16.7) | 68.9 (16.0) | |

| No drainage (%)* | <0.001 | ||||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 0.2 (0.1, 0.8) | 0.6 (0.2, 0.9) | 0.2 (0.2, 0.4) | 0.2 (0.1, 0.3) | 0.2 (0.1, 1.7) | 0.5 (0.2, 3.3) | |

| Mean (SD) | 3.2 (8.7) | 1.4 (3.7) | 0.7 (2.8) | 2.0 (6.5) | 4.6 (10.7) | 5.8 (10.9) | |

| No electricity (%)* | <0.001 | ||||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 0.2 (0.1, 0.4) | 0.3 (0.2, 0.4) | 0.1 (0.1, 0.3) | 0.1 (0.1, 0.2) | 0.2 (0.1, 1.0) | 0.3 (0.1, 2.0) | |

| Mean (SD) | 2.5 (7.4) | 0.5 (0.7) | 0.5 (2.2) | 1.3 (4.7) | 4.1 (9.5) | 3.7 (9.1) | |

| No piped water (%)* | <0.001 | ||||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 0.5 (0.4, 0.9) | 0.9 (0.4, 1.3) | 0.4 (0.4, 0.9) | 0.5 (0.4, 0.9) | 0.6 (0.4, 3.4) | 0.9 (0.3, 3.4) | |

| Mean (SD) | 3.2 (7.5) | 2.1 (5.4) | 0.9 (2.9) | 1.7 (5.3) | 5.4 (9.9) | 3.8 (7.1) | |

| Dirt floor (%)* | <0.001 | ||||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 0.5 (0.3, 2.1) | 0.7 (0.6, 1.9) | 0.5 (0.3, 0.6) | 0.5 (0.3, 1.3) | 0.6 (0.4, 5.1) | 0.7 (0.4, 7.0) | |

| Mean (SD) | 4.2 (9.0) | 1.9 (3.7) | 1.0 (2.9) | 2.4 (6.3) | 6.1 (10.7) | 7.3 (11.9) | |

| No health insurance (%)* | <0.001 | ||||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 13.2 (13.1, 19.0) | 19.8 (13.1, 39.9) | 13.1 (13.1, 17.8) | 13.1 (13.1, 19.0) | 15.4 (13.1, 19.7) | 14.1 (10.9, 18.3) | |

| Mean (SD) | 18.1 (10.0) | 24.3 (11.7) | 16.7 (7.8) | 17.0 (7.3) | 19.1 (11.3) | 17.5 (11.1) | |

| Social Lag Index* | <0.001 | ||||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | -1.1 (-1.2, -0.6) | -0.9 (-1.1, -0.6) | -1.1 (-1.2, -0.9) | -1.1 (-1.2, -1.0) | -1.1 (-1.2, -0.2) | -1.0 (-1.3, -0.2) | |

| Mean (SD) | -0.5 (1.4) | -0.8 (0.6) | -1.0 (0.5) | -0.9 (1.0) | -0.2 (1.7) | -0.2 (1.7) | |

| Social Lag Degree* | <0.001 | ||||||

| Very low | 4484 (73%) | 202 (75%) | 1442 (89%) | 839 (86%) | 1373 (63%) | 628 (58%) | |

| Low | 846 (14%) | 62 (23%) | 151 (9.3%) | 69 (7.0%) | 351 (16%) | 213 (20%) | |

| Medium | 173 (2.8%) | 3 (1.1%) | 13 (0.8%) | 25 (2.5%) | 84 (3.8%) | 48 (4.4%) | |

| High | 38 (0.6%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 38 (1.7%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Very high | 607 (9.9%) | 4 (1.5%) | 15 (0.9%) | 48 (4.9%) | 349 (16%) | 191 (18%) | |

| Rural population <5000 (%)* | <0.001 | ||||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 19.3 (5.6, 41.2) | 26.0 (19.3, 49.7) | 19.3 (7.0, 20.2) | 19.3 (3.3, 19.3) | 19.3 (5.6, 54.2) | 19.1 (10.3, 63.8) | |

| Mean (SD) | 29.8 (31.7) | 35.2 (28.0) | 24.6 (27.0) | 23.0 (28.1) | 32.8 (33.8) | 36.3 (35.6) | |

| Migration Intensity Index* | <0.001 | ||||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 63.4 (63.4, 64.0) | 63.9 (63.3, 64.3) | 63.4 (63.4, 63.7) | 63.4 (63.4, 63.7) | 63.7 (63.4, 64.3) | 63.7 (63.2, 64.1) | |

| Mean (SD) | 63.5 (0.9) | 63.4 (1.3) | 63.4 (0.8) | 63.3 (1.0) | 63.7 (0.9) | 63.5 (0.9) | |

| Migration Intensity Degree* | <0.001 | ||||||

| None | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Very low | 821 (13%) | 53 (20%) | 91 (5.6%) | 75 (7.6%) | 461 (21%) | 141 (13%) | |

| Low | 4254 (69%) | 151 (56%) | 1306 (81%) | 707 (72%) | 1397 (64%) | 693 (64%) | |

| Medium | 943 (15%) | 42 (15%) | 189 (12%) | 165 (17%) | 312 (14%) | 235 (22%) | |

| High | 125 (2.0%) | 23 (8.5%) | 33 (2.0%) | 34 (3.5%) | 24 (1.1%) | 11 (1.0%) | |

| Very high | 5 (<0.1%) | 2 (0.7%) | 2 (0.1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (<0.1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Agricultural day laborers (%)* | <0.001 | ||||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 32.2 (31.3, 40.0) | 45.8 (32.2, 53.6) | 32.2 (32.2, 34.4) | 32.2 (31.3, 33.7) | 32.2 (31.2, 39.9) | 33.3 (31.3, 51.5) | |

| Mean (SD) | 36.9 (13.0) | 44.1 (13.2) | 35.5 (9.0) | 34.6 (9.0) | 35.9 (14.1) | 41.2 (16.4) | |

| High day laborer municipality (>50%)* | <0.001 | ||||||

| FALSE | 5099 (84%) | 161 (60%) | 1422 (88%) | 886 (93%) | 1873 (86%) | 757 (70%) | |

| TRUE | 979 (16%) | 109 (40%) | 185 (12%) | 68 (7.1%) | 294 (14%) | 323 (30%) | |

| 1Median (Q1, Q3); Mean (SD); n (%). *Municipal-level indicator from residence municipality. Relative week: Week 1 = first week with cases in each state. 2Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test; Pearson's Chi-squared test | |||||||

|

Overall N = 57761 |

Chihuahua N = 44931 |

Jalisco N = 5441 |

Guerrero N = 2421 |

Michoacán N = 2251 |

Chiapas N = 1611 |

Sonora N = 1111 |

p-value2 | |

| Age (years) | <0.001 | |||||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 18.0 (4.0, 29.0) | 20.0 (4.0, 31.0) | 12.0 (5.0, 22.0) | 7.0 (3.0, 18.0) | 10.0 (3.0, 20.0) | 13.0 (5.0, 26.0) | 14.0 (4.0, 24.0) | |

| Unvaccinated | 4982 (86%) | 3907 (87%) | 422 (78%) | 207 (86%) | 202 (90%) | 151 (94%) | 93 (84%) | <0.001 |

| Indigenous | 1778 (31%) | 1246 (28%) | 154 (28%) | 144 (60%) | 137 (61%) | 84 (52%) | 13 (12%) | <0.001 |

| Complications | 981 (17%) | 859 (19%) | 24 (4.4%) | 47 (19%) | 12 (5.3%) | 32 (20%) | 7 (6.3%) | <0.001 |

| Marginalization Index* | <0.001 | |||||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 0.9 (0.9, 0.9) | 0.9 (0.9, 0.9) | 0.9 (0.9, 0.9) | 0.7 (0.7, 0.8) | 0.9 (0.9, 0.9) | 0.8 (0.8, 0.9) | 0.9 (0.9, 0.9) | |

| No health insurance (%)* | <0.001 | |||||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 13.1 (12.9, 19.0) | 13.1 (11.9, 15.4) | 29.7 (27.5, 39.9) | 7.9 (7.9, 28.0) | 53.4 (50.5, 53.4) | 40.7 (20.3, 44.7) | 17.9 (15.4, 21.8) | |

| Rural population (%)* | <0.001 | |||||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 19.3 (5.6, 41.2) | 19.3 (5.6, 28.2) | 13.3 (3.3, 26.0) | 100.0 (44.0, 100.0) | 17.4 (17.4, 29.7) | 32.8 (15.0, 82.8) | 8.7 (8.7, 18.4) | |

| Day laborers (%)* | <0.001 | |||||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 32.2 (31.3, 40.0) | 32.2 (31.3, 32.3) | 49.6 (42.1, 53.6) | 61.5 (61.5, 66.4) | 75.6 (71.8, 75.6) | 31.3 (31.3, 48.0) | 53.3 (53.3, 62.8) | |

| High day laborer mun.* | 873 (15%) | 93 (2.1%) | 226 (47%) | 242 (100%) | 203 (90%) | 25 (16%) | 84 (76%) | <0.001 |

| 1*Municipal-level indicator. 2Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test; Pearson's Chi-squared test | ||||||||

| Variable | First 50 mun. (Wk 8-19) N = 44001 |

Last 50 mun. (Wk 45-52) N = 1321 |

p-value2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | <0.001 | ||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 20.0 (4.5, 31.0) | 9.5 (5.0, 22.0) | |

| Mean (SD) | 19.6 (15.0) | 13.6 (11.8) | |

| Unvaccinated | 3819 (87%) | 116 (88%) | 0.817 |

| Indigenous | 1102 (25%) | 68 (52%) | <0.001 |

| Complications | 778 (18%) | 11 (8.3%) | 0.007 |

| Death | 22 (0.5%) | 0 (0%) | 0.858 |

| Marginalization Index (0-100)* | <0.001 | ||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 0.9 (0.9, 0.9) | 0.8 (0.8, 0.9) | |

| Mean (SD) | 0.9 (0.1) | 0.8 (0.1) | |

| Marginalization Degree* | <0.001 | ||

| Very low | 3761 (85%) | 48 (36%) | |

| Low | 222 (5.0%) | 13 (9.8%) | |

| Medium | 23 (0.5%) | 8 (6.1%) | |

| High | 77 (1.8%) | 21 (16%) | |

| Very high | 316 (7.2%) | 42 (32%) | |

| No health insurance (%)* | <0.001 | ||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 13.1 (12.5, 15.6) | 27.5 (19.9, 29.8) | |

| Mean (SD) | 14.4 (4.0) | 26.9 (9.3) | |

| Rural population <5000 (%)* | <0.001 | ||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 19.3 (5.6, 19.3) | 59.5 (14.9, 82.8) | |

| Mean (SD) | 25.8 (29.1) | 52.3 (36.5) | |

| Migration Intensity Index* | <0.001 | ||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 63.4 (63.4, 63.7) | 64.9 (64.0, 65.0) | |

| Mean (SD) | 63.5 (0.8) | 64.3 (1.2) | |

| Agricultural day laborers (%)* | <0.001 | ||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 32.2 (31.3, 32.3) | 48.0 (42.3, 51.2) | |

| Mean (SD) | 32.2 (6.6) | 47.2 (10.8) | |

| High day laborer municipality* | 104 (2.4%) | 44 (33%) | <0.001 |

| 1Median (Q1, Q3); Mean (SD); n (%). *Municipal-level indicator. | |||

| 2Wilcoxon rank sum test; Chi-squared test | |||

| Variable | Complications n/N (%) | aOR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | |||

| 5-19 years (ref) | 259/1774 (14.6%) | 1.00 (ref) | - |

| <1 year | 234/641 (36.5%) | 3.59 (2.88-4.46) | <0.001 |

| 1-4 years | 287/942 (30.5%) | 2.69 (2.20-3.28) | <0.001 |

| >=20 years | 226/2792 (8.1%) | 0.66 (0.54-0.80) | <0.001 |

| Indigenous | |||

| No (ref) | 470/4264 (11%) | 1.00 (ref) | - |

| Yes | 536/1885 (28.4%) | 2.35 (1.99-2.77) | <0.001 |

| Vaccination status | |||

| Vaccinated (ref) | 75/868 (8.6%) | 1.00 (ref) | - |

| Unvaccinated | 931/5281 (17.6%) | 2.03 (1.57-2.63) | <0.001 |

| Outbreak phase | |||

| Early, weeks 1-14 (ref) | 209/1941 (10.8%) | 1.00 (ref) | - |

| Late, weeks >=15 | 797/4208 (18.9%) | 1.09 (0.90-1.32) | 0.366 |

| Municipality type | |||

| Urban (ref) | 614/4772 (12.9%) | 1.00 (ref) | - |

| Rural (>50% in localities <5000) | 392/1377 (28.5%) | 1.81 (1.55-2.13) | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).