Submitted:

12 June 2025

Posted:

18 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design and Period

Study Area and Population

Data Sources

Analytical Procedures

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

Appendix A

| Cluster ID | Municipalities included |

|---|---|

| 01 | Una, São José da Vitória, Santa Luzia, Buerarema, Arataca, Jussari, Itabuna, Camacan, Itapé, Canavieiras, Ilhéus, Mascote, Barro Preto, Ibicaraí, Itaju do Colônia, Pau Brasil, Itajuípe, Floresta Azul, Uruçuca, Almadina, Belmonte, Santa Cruz da Vitória, Coaraci, Potiraguá, Firmino Alves, Itororó, Itapebi, Itacaré, Itapitanga, Itapetinga, Ibicuí, Aurelino Leal, Ubaitaba, Itarantim, Santa Cruz Cabrália, Gongogi, Itagimirim, Nova Canaã, Iguaí, Maraú, Dário Meira, Eunápolis, Itagibá, Maiquinique, Ubatã, Ibirapitanga, Caatiba, Barra do Rocha, Camamu, Macarani, Itambé, Ipiaú, Ibirataia, Aiquara, Igrapiúna, Boa Nova, Itagi, Planalto, Poções, Porto Seguro, Barra do Choça, Piraí do Norte, Jitaúna, Nova Ibiá, Ribeirão do Largo, Gandu, Ituberá, Itabela, Apuarema, Guaratinga, Itamari, Nilo Peçanha, Bom Jesus da Serra, Taperoá, Jequié, Wenceslau Guimarães, Teolândia, Vitória da Conquista, Cairu, Manoel Vitorino, Presidente Tancredo Neves, Encruzilhada, Anagé, Jaguaquara, Jucuruçu, Valença, Mirante, Itamaraju, Cravolândia, Itaquara, Prado, Lafaiete Coutinho, Mutuípe, Jiquiriçá, Caetanos, Itiruçu, Belo Campo, Ubaíra, Cândido Sales, Santa Inês, Laje, Lajedo do Tabocal, Jaguaripe, Vereda, Aratuípe, Caraíbas, Irajuba, São Miguel das Matas, Maracás, Santo Antônio de Jesus, Muniz Ferreira, Amargosa, Itanhém, Tremedal, Brejões, Tanhaçu, Vera Cruz, Alcobaça, Nazaré, Varzedo, Teixeira de Freitas, Dom Macedo Costa, Aracatu, Elísio Medrado, Planaltino, Contendas do Sincorá, Nova Itarana, Maetinga, Conceição do Almeida, Salinas da Margarida, São Felipe, Itaparica, Milagres, Medeiros Neto, Maragogipe, Salvador, Iramaia, Barra da Estiva, Saubara, Piripá, Lauro de Freitas, Caravelas, Sapeaçu, Castro Alves, Santa Teresinha, Madre de Deus, Cruz das Almas, Presidente Jânio Quadros, São Félix, Marcionílio Souza, Simões Filho, Itatim, Ituaçu , Iaçu, Cachoeira, Lajedão, Muritiba, São Francisco do Conde, Candeias, Governador Mangabeira, Cabaceiras do Paraguaçu, Ibirapuã, Cordeiros, Brumado. |

| 02 | Caravelas, Nova Viçosa, Teixeira de Freitas, Ibirapuã , Alcobaça, Mucuri, Vereda, Lajedão , Prado, Medeiros Neto, Itamaraju, Itanhém, Jucuruçu, Itabela, Porto Seguro, Guaratinga, Eunápolis, Santa Cruz Cabrália, Itagimirim, Itapebi, Belmonte, Potiraguá , Itarantim, Mascote, Maiquinique , Canavieiras, Pau Brasil, Camacan, Macarani, Santa Luzia, Itapetinga, Ribeirão do Largo, Encruzilhada, Arataca, Una, Itaju do Colônia, Jussari , São José da Vitória, Itambé, Itororó, Buerarema, Itapé, Firmino Alves, Caatiba , Cândido Sales, Santa Cruz da Vitória, Ibicaraí, Floresta Azul, Itabuna, Nova Canaã, Barra do Choça, Vitória da Conquista, Barro Preto, Ilhéus, Almadina , Itajuípe, Ibicuí, Coaraci, Belo Campo, Planalto, Iguaí, Tremedal, Uruçuca, Itapitanga , Poções, Dário Meira, Piripá , Anagé, Aurelino Leal, Itacaré, Boa Nova, Cordeiros, Bom Jesus da Serra, Gongogi, Caraíbas, Ubaitaba, Itagibá, Maetinga, Itagi, Maraú, Presidente Jânio Quadros, Caetanos, Condeúba, Barra do Rocha, Ubatã, Aiquara , Ipiaú, Ibirapitanga, Mirante, Aracatu, Camamu, Ibirataia, Mortugaba , Manoel Vitorino, Jitaúna, Tanhaçu, Guajeru , Jequié, Igrapiúna, Jacaraci , Nova Ibiá, Apuarema, Piraí do Norte, Gandu, Itamari , Malhada de Pedras, Ituberá, Brumado, Nilo Peçanha, Wenceslau Guimarães, Caculé, Contendas do Sincorá, Lafaiete Coutinho, Rio do Antônio, Licínio de Almeida, Urandi, Teolândia, Taperoá, Jaguaquara, Ituaçu , Itiruçu, Ibiassucê, Cairu, Itaquara, Presidente Tancredo Neves, Barra da Estiva, Cravolândia, Lajedo do Tabocal, Maracás, Dom Basílio, Pindaí, Jiquiriçá , Valença, Mutuípe, Iramaia, Lagoa Real, Santa Inês, Ubaíra, Candiba, Livramento de Nossa Senhora, Irajuba, Laje, Planaltino, Sebastião Laranjeiras, Rio de Contas, Jussiape, Ibicoara, Caetité, Guanambi, Brejões, Jaguaripe, São Miguel das Matas, Aratuípe, Marcionílio Souza, Amargosa, Nova Itarana, Santo Antônio de Jesus, Muniz Ferreira, Varzedo, Elísio Medrado, Vera Cruz, Itaetê, Nazaré, Milagres, Dom Macedo Costa, Igaporã, Abaíra, Paramirim, Conceição do Almeida, Érico Cardoso, São Felipe, Salinas da Margarida, Iaçu, Palmas de Monte Alto, Itaparica, Iuiu , Maragogipe, Mucugê, Salvador, Santa Teresinha, Matina, Tanque Novo, Castro Alves, Itatim, Sapeaçu. |

| 03 | Santa Brígida, Paulo Afonso, Pedro Alexandre, Jeremoabo, Coronel João Sá, Sítio do Quinto, Glória, Antas, Novo Triunfo, Rodelas, Cícero Dantas, Adustina , Fátima, Canudos, Macururé, Paripiranga, Banzaê , Heliópolis, Euclides da Cunha, Ribeira do Pombal, Chorrochó, Ribeira do Amparo, Uauá, Quijingue, Cipó, Monte Santo, Tucano, Itapicuru, Abaré, Curaçá, Nova Soure, Cansanção, Olindina, Nordestina, Araci, Crisópolis, Andorinha, Rio Real, Sátiro Dias, Teofilândia, Jaguarari, Acajutiba, Itiúba, Jandaíra , Biritinga , Santaluz, Aporá, Barrocas, Queimadas, Valente, Senhor do Bonfim, Inhambupe, Conceição do Coité, Serrinha, Juazeiro, Conde, Água Fria, Retirolândia, Lamarão, Filadélfia, Esplanada, São Domingos, Ichu , Ponto Novo, Cardeal da Silva, Ouriçangas, Entre Rios, Aramari , Santanópolis , Santa Bárbara, Antônio Gonçalves, Candeal, Gavião, Pindobaçu, Nova Fátima, Irará, Alagoinhas, Capim Grosso, Tanquinho, Riachão do Jacuípe, Caldeirão Grande, São José do Jacuípe, Araçás, Pedrão, Saúde, Caém , Capela do Alto Alegre, Quixabeira, Coração de Maria, Pé de Serra, Teodoro Sampaio, Itanagra , Campo Formoso, Feira de Santana, Catu, Pojuca, Serra Preta, Várzea da Roça, Anguera , Conceição do Jacuípe, Serrolândia, Terra Nova, Sobradinho, Mirangaba, Pintadas, Amélia Rodrigues, Mata de São João, Jacobina, São Gonçalo dos Campos, Várzea do Poço, São Sebastião do Passé, Ipecaetá, Antônio Cardoso, Mairi, Dias d'Ávila, Santo Amaro, Conceição da Feira, Camaçari, Santo Estêvão, Ipirá, São Francisco do Conde, Miguel Calmon, Candeias, Baixa Grande, Governador Mangabeira, Cachoeira, Cabaceiras do Paraguaçu, Muritiba, Simões Filho, Madre de Deus, São Félix, Rafael Jambeiro, Cruz das Almas, Saubara, Piritiba, Lauro de Freitas. |

| 04 | Pilão Arcado, Campo Alegre de Lourdes, Buritirama , Remanso, Xique-Xique, Barra, Itaguaçu da Bahia, Sento Sé, Mansidão, Gentio do Ouro, Central, Jussara, Uibaí , Presidente Dutra, Santa Rita de Cássia, Morpará, São Gabriel, Irecê, Ibipeba, Casa Nova, Umburanas, Ipupiara, João Dourado, Wanderley, Ibititá , Lapão, Ibotirama, Cotegipe, América Dourada, Ourolândia, Brotas de Macaúbas, Barra do Mendes, Sobradinho, Barro Alto, Canarana, Muquém de São Francisco, Oliveira dos Brejinhos, Várzea Nova, Cafarnaum, Campo Formoso, Souto Soares, Morro do Chapéu, Cristópolis , Mirangaba, Angical, Mulungu do Morro, Brejolândia , Riachão das Neves, Bonito, Tabocas do Brejo Velho, Paratinga, Ibitiara, Seabra, Iraquara, Jacobina, Catolândia, Boquira, Antônio Gonçalves, Formosa do Rio Preto, Pindobaçu, Miguel Calmon, Juazeiro, Saúde, Utinga, Sítio do Mato, Serra Dourada, Wagner, Ibipitanga, Tapiramutá, Baianópolis, Palmeiras, Lençóis, Piritiba, Senhor do Bonfim, Novo Horizonte, Caém , Jaguarari, Filadélfia, Caldeirão Grande, Boninal , Ponto Novo, Barreiras, Macaúbas, Serrolândia, Várzea do Poço, Santana, Mundo Novo, Lajedinho, Andorinha, Quixabeira, Rio do Pires, Canápolis , Piatã, Bom Jesus da Lapa, Itiúba, Andaraí, Ruy Barbosa, Caturama, Capim Grosso, Mairi, Botuporã, Várzea da Roça, Ibiquera , Nova Redenção, Santa Maria da Vitória, Mucugê, São José do Jacuípe, Queimadas, Curaçá, Baixa Grande, Macajuba, Serra do Ramalho, Érico Cardoso, Abaíra, Tanque Novo, Luís Eduardo Magalhães, Uauá, Paramirim, Monte Santo, Gavião, Riacho de Santana, Capela do Alto Alegre, São Desidério, Cansanção, São Félix do Coribe, Boa Vista do Tupim, Pintadas, Itaetê, Nordestina, Itaberaba, São Domingos, Santaluz, Nova Fátima, Ibicoara, Jussiape, Rio de Contas, Matina, Valente, Igaporã, Pé de Serra, Abaré, Retirolândia, Marcionílio Souza, Chorrochó, Ipirá, Livramento de Nossa Senhora, Caetité, Coribe, Riachão do Jacuípe, Canudos, Iaçu, Quijingue, Iramaia, Carinhanha, Dom Basílio, Conceição do Coité, Correntina, Lagoa Real, Barra da Estiva, Euclides da Cunha, Araci, Palmas de Monte Alto, Ituaçu , Guanambi, Planaltino, Serra Preta, Macururé, Barrocas, Malhada, Ichu , Rafael Jambeiro, Feira da Mata, Itatim, Candeal, Nova Itarana, Maracás, Contendas do Sincorá, Teofilândia, Milagres, Tucano, Ibiassucê, Ipecaetá, Serrinha, Brumado, Tanquinho, Irajuba, Candiba, Santa Teresinha, Rio do Antônio, Anguera , Lajedo do Tabocal, Banzaê , Brejões, Rodelas, Iuiu , Pindaí, Santa Bárbara, Lamarão, Santo Estêvão, Malhada de Pedras, Itiruçu, Biritinga , Tanhaçu, Jeremoabo, Caculé, Antônio Cardoso, Feira de Santana, Ribeira do Pombal, Lafaiete Coutinho, Sebastião Laranjeiras, Amargosa, Elísio Medrado, Castro Alves, Santa Inês, Novo Triunfo, Cícero Dantas, Santanópolis , Cabaceiras do Paraguaçu, Licínio de Almeida, Jaborandi, Cipó, Itaquara, Nova Soure, Glória, Guajeru , Aracatu, Água Fria, Ubaíra, Varzedo, Sapeaçu, Jaguaquara, Sátiro Dias, Cravolândia, Governador Mangabeira, São Miguel das Matas, Muritiba, Irará, Cruz das Almas, Conceição do Almeida, Conceição da Feira, Urandi, São Gonçalo dos Campos, Mirante, Ribeira do Amparo, Manoel Vitorino, Antas, Paulo Afonso, Heliópolis, Coração de Maria, Jiquiriçá , Caetanos, Ouriçangas, Dom Macedo Costa, São Félix, Mutuípe, Jequié, Jacaraci , Santo Antônio de Jesus, São Felipe, Laje, Fátima, Pedrão, Santa Brígida, Presidente Jânio Quadros, Conceição do Jacuípe, Olindina, Sítio do Quinto, Maetinga, Cachoeira, Cocos |

| 05 | Caetité |

| 06 | Sobradinho |

| 07 | Pojuca |

| 08 | Pé de Serra, Riachão do Jacuípe, Nova Fátima |

| 09 | Lagoa Real, Ibiassucê, Caetité |

| 10 | Santa Cruz Cabrália |

| 11 | São Francisco do Conde, Madre de Deus, Candeias |

| 12 | Madre de Deus, São Francisco do Conde |

| 13 | Maiquinique |

| 14 | Santa Bárbara |

| 15 | Itapetinga, Itororó |

| 16 | Porto Seguro |

| 17 | Ibipitanga |

| 18 | Remanso |

| 19 | Bonito |

| 20 | Iuiu |

| 21 | Vereda |

| 22 | Cotegipe |

| 23 | Itanagra |

| 24 | Ituberá, Nilo Peçanha |

| 25 | Esplanada, Cardeal da Silva |

| 26 | Macajuba |

| 27 | Várzea da Roça |

| 28 | Presidente Dutra |

| 29 | Catolândia |

| 30 | Catu |

| 31 | Baixa Grande |

| 32 | Quixabeira |

| 33 | São Domingos |

References

- Morgan OW, Aguilera X, Ammon A, Amuasi J, Fall IS, Frieden T, et al. Disease surveillance for the COVID-19 era: time for bold changes. Lancet. (2021); 397(10292):2317-2319. [CrossRef]

- Li CX, Noreen S, Zhang LX, Saeed M, Wu PF, Li JH, et al. A critical analysis of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) complexities, emerging variants, and therapeutic interventions and vaccination strategies. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy; (2022); 146, 112550. [CrossRef]

- Raymundo CE, Oliveira MC, Eleuterio TdA, André SR, da Silva MG, Queiroz ERdS, et al. Spatial analysis of COVID-19 incidence and the sociodemographic context in Brazil. PLoS ONE; (2021). 16(3): e0247794. [CrossRef]

- Sott MK, Bender MS, da Silva Baum K. Covid-19 Outbreak in Brazil: Health, Social, Political, and Economic Implications. International Journal of Health Services. (2022); 52(4):442-454. [CrossRef]

- Martins JP, Siqueira BA, Sansone NMS & Marson FAL. COVID-19 in Brazil: a three-year update. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease, 116074 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Castro MC, Kim S, Barberia L, Ribeiro AF, Gurzenda S, Ribeiro KB, Abbott E, Blossom J, Rache B, Singer BH. Spatiotemporal pattern of COVID-19 spread in Brazil. 2021, Science 372:821–826. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira JF, Jorge DCP, Veiga RV, et al. Mathematical modeling of COVID-19 in 14.8 million individuals in Bahia, Brazil. Nat Commun 12, 333 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde e Ambiente. Boletim Epidemiológico Especial. Doença pelo Coronavírus COVID-19 N.º 147, de 28/01/2022. https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/media/pdf/2022/boletim_epidemiologico_covid_61 1.pdf.

- Campbell F, Archer B, Laurenson-Schafer H, et al. (2021). Increased transmissibility and global spread of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern as at June 2021. Eurosurveillance, 26(24), 2100509. [CrossRef]

- Faria NR, Mellan TA, Whittaker C, et al. (2021). Genomics and epidemiology of the P.1 SARS-CoV-2 lineage in Manaus, Brazil. Science, 372(6544), 815–821. [CrossRef]

- Bahia. Boletim Epidemiológico Covid-19 N.º 976 - 31/12/2022. Secretaria de Saúde. Bahia, 31 dezembro 2022. Disponível em: https://www.saude.ba.gov.br/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Boletim-Infografico-31-12-2022.pdf.

- Martin A, Markhvida M, Hallegatte S et al. Socio-Economic Impacts of COVID-19 on Household Consumption and Poverty. EconDisCliCha 4, 453–479 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Kan Z, Kwan MP, Wong MS, Huang J, Liu D. Identifying the space-time patterns of COVID-19 risk and their associations with different built environment features in Hong Kong. Sci. Total Environ. (2021), 772, 145379.

- IBGE. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Censo Demográfico 2022. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE; 2022. Disponível em: https://censo2022.ibge.gov.br/sobre/conhecendo-o-brasil.html.

- LEAL, MB; et al. A experiência do observatório baiano de regionalização: uma ferramenta para avaliação e qualificação da gestão regionalizada do SUS na Bahia. RECIIS - Revista Eletrônica de Comunicação, Informação e Inovação em Saúde, Rio de Janeiro, v. 6, n. 2, p. 1-7, ago. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Departamento de Análise Epidemiológica e Vigilância de Doenças Não Transmissíveis. e-SUS Notifica: Manual de Instruções. Brasília/DF, 2022. http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/esus_notifica_manual_instrucoes.pdf.

- Bahia. Secretaria Estadual de Saúde da Bahia. Diretoria de Vigilância Epidemiológica. Guia Rápido Sivep-Gripe. Maio, 2021. https://www.saude.ba.gov.br/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/GUIA-RAPIDO-SIVEP-GRIPE-atualizado-em-maio_2021.pdf.

- Cruz OG & Freitas, LP. Estudos Ecológicos (2021). Cluster Espaço-Temporal https://ogcruz.github.io/Curso_eco_2021/an%C3%A1lise-espa%C3%A7o-temporal.html#cluster-espa%C3%A7o-temporal.

- Kulldorff, M. (1997). A spatial scan statistic. Communications in Statistics - Theory and Methods, 26(6), 1481–1496. [CrossRef]

- Romão GA & Brito IS (2022). Falhas das funções de governança na resposta à covid-19: o caso do isolamento social no Brasil. Multitemas, 27(66), 95–121. [CrossRef]

- Rocha MM, Almeida PEG, Tenório GG, Artuzo RM & Mendes HDM. (2022). As respostas dos governos municipais à Covid-19 no Brasil: a política de distanciamento social nas cidades médias nos primeiros meses da pandemia. Teoria e Cultura, 17(1). [CrossRef]

- Maciel E, Fernandez M, Calife K, Garrett D, Domingues C, Kerr L, et al. A campanha de vacinação contra o SARS-CoV-2 no Brasil e a invisibilidade das evidências científicas. Ciênc saúde coletiva. 2022 - Mar; 27(3): 951–6. [CrossRef]

- GeoCombate COVID-19 Bahia. Nota Técnica 05 - Análise da Interiorização da COVID-19 na Bahia [Internet]. Salvador: Secretaria da Saúde do Estado da Bahia; 2020. Acessado em 08/02/2025. Disponível em: https://covid19.estudoscolaborativos.sei.ba.gov.br/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Interiorizacao-da-COVID-19-na-Bahia.pdf.

- Bahia. Diário Oficial do Estado da Bahia. Decreto nº 19.722 de 22 de maio de 2020. Estabelece medidas complementares de prevenção ao contágio e de enfrentamento da propagação do novo coronavírus, causador da COVID-19, na forma que indica. 23 de maio de 2020. Ano CIV. Edição n° 22.908, página 5.

- Fortuna DBS & Fortuna, JL. (2020). Perfil epidemiológico dos casos de COVID-19 no município de Teixeira de Freitas-BA no período de julho a setembro de 2020. Brazilian Journal of Health Review, 3(6), 16278-16294. Acesso em: 09/02/2025. Disponível em: https://ojs.brazilianjournals.com.br/ojs/index.php/BJHR/article/view/19888.

- Aguiar, S. (2020). COVID-19: A doença dos espaços de fluxos. Geographia, 22(48), p. 51-74. [CrossRef]

- Bahia. Superintendência de Estudos Econômicos e Sociais da Bahia. Panorama da COVID-19 na Bahia em 2020. Salvador: Disponível em: https://www.sei.ba.gov.br/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=1234.

- Souza SS, Costa EL, Calazans MIP, Antônio MMP, Dias CRC, Cardoso JP. Análise espacial dos casos de COVID-19 notificados no estado da Bahia, Brasil. Cad Saúde Colet, 2022; 30(4) 572-583. [CrossRef]

- Silva RJ, Silva K, Mattos J. Análise espacial sobre a dispersão da covid-19 no Estado da Bahia. SciELO Prepr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Zhou C, Su F, Pei T, Zhang U, Du Y, Luo B, et al. COVID-19: challenges to GIS with Big Data. Geogr Sustainability. 2020;1(1):77-87. [CrossRef]

- Sun F, Matthews S, Yang C, Hu MH. A spatial analysis of the COVID-19 period prevalence in U.S. counties through June 28, 2020: where geography matters? Ann Epidemiol. 2020;52:54-59.e1. [CrossRef]

- Murugesan B, Karuppannan S, Mengistie AT, Ranganathan M, Gopalakrishnan G. Distribution and trend analysis of COVID-19 in India: geospatial approach. J Geog Stud. 2020;4(1):1-9. [CrossRef]

- Monié, FA. África subsaariana diante da pandemia de Coronavírus/COVID-19: difusão espacial, impactos e desafios. Espaço e Economia. 2020;18. [CrossRef]

- Sodoré AA, Monié F, Pouya LP. Distribuição geográfica e difusão espacial do coronavírus/Covid-19 no Burquina Fasso (África Ocidental). Rev Tamoios. 2020;16(1):167-87. [CrossRef]

- Castro RR, Santos RSC, Sousa GJB, et al. Spatial dynamics of the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil. Epidemiology and Infection. 2021;149:e60. [CrossRef]

- The Lancet. Redefining vulnerability in the era of COVID-19. Lancet. 2020 Apr 4;395(10230):1089. [CrossRef]

- Maciel JAC, Castro-Silva II, Farias MR de. Análise inicial da correlação espacial entre a incidência de COVID-19 e o desenvolvimento humano nos municípios do estado do Ceará no Brasil. Rev bras epidemiol [Internet]. 2020;23:e200057. [CrossRef]

- Dhama K, Nainu F, Frediansyah A, Yatoo MI, Mohapatra RK, Chakraborty S, Zhou H, Islam MR, Mamada SS, Kusuma HI et al. Global emerging Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2: Impacts, challenges and strategies. J. Infect. Public Health 2022, 16, 4–14. [CrossRef]

- Ling-Hu, T.; Rios-Guzman, E.; Lorenzo-Redondo, R.; Ozer, E.A.; Hultquist, J.F. Challenges and Opportunities for Global Genomic Surveillance Strategies in the COVID-19 Era. Viruses 2022, 14, 2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade LA, da Paz WS, Lima AGCF, Araújo DC, Duque AM, Peixoto MVS, Góes MAO, Souza CDF, Ribeiro CJN, Lima SVMA, Santos MB, Santos AD. Spatiotemporal Pattern of COVID-19-Related Mortality during the First Year of the Pandemic in Brazil: A Population-based Study in a Region of High Social Vulnerability. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2021 Nov 10;106(1):132-141. [CrossRef]

- Xu F, Beard K. A comparison of prospective space-time scan statistics and spatiotemporal event sequence based clustering for COVID-19 surveillance. PLoS One. 2021 Jun 10;16(6):e0252990. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

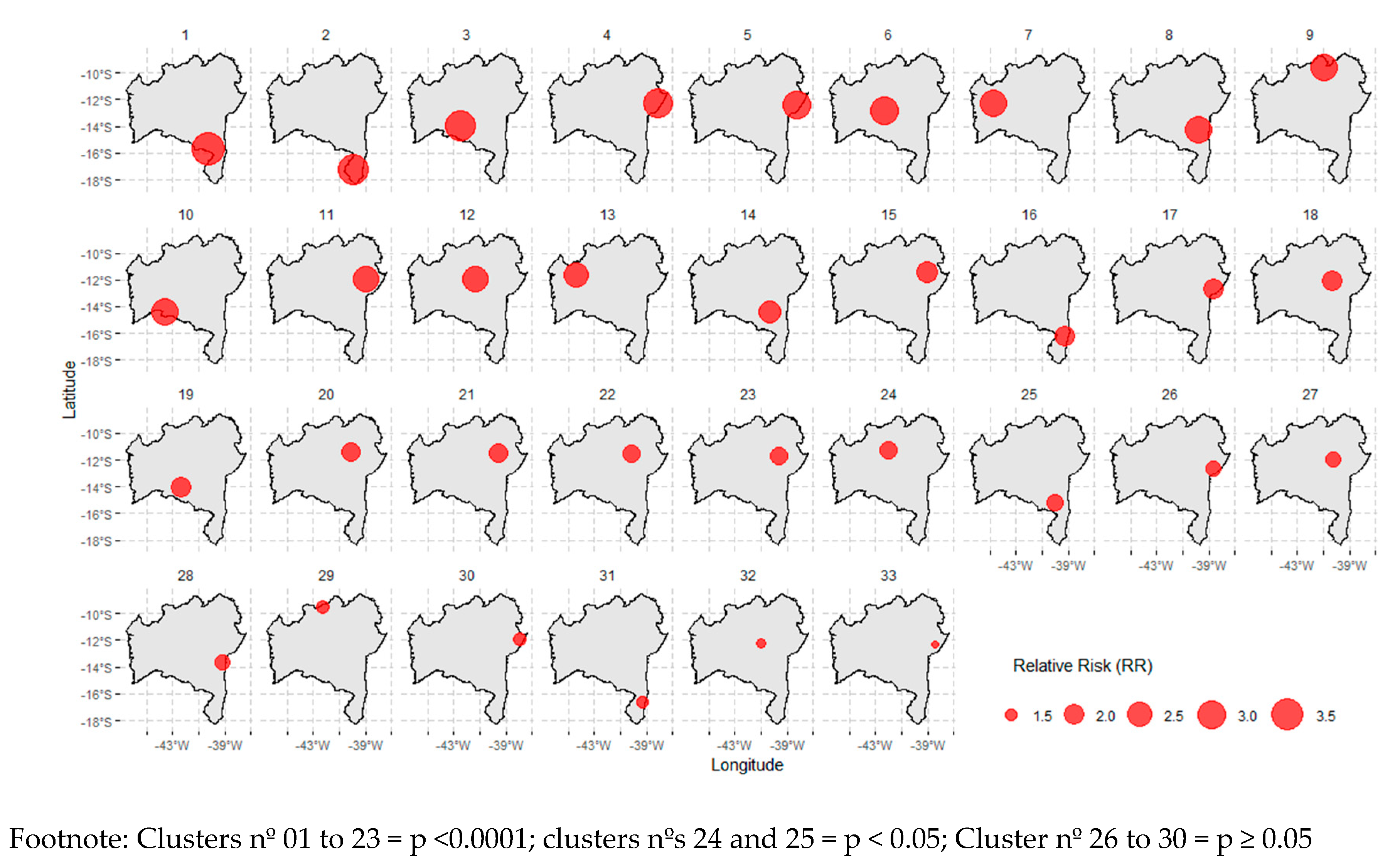

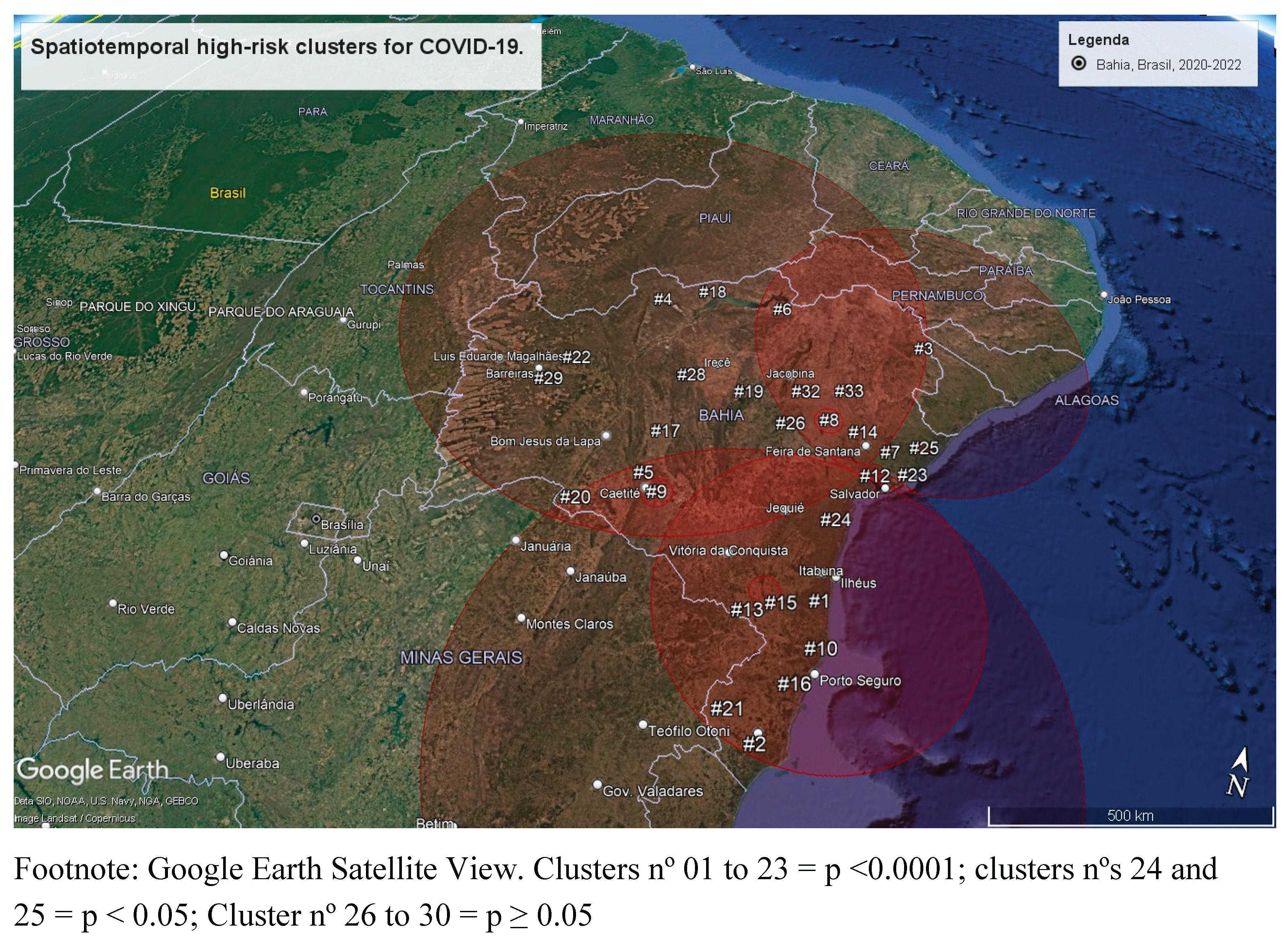

| Cluster ID | Number of cities involved | Span (km) | Time frame | Population at risk | Number of cases | Expected cases | Annual cases per 100000 | RRa | LLRb | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 164 | 586.3 | 2020/5/1 - 2021/6/30 | 265617828 | 702720 | 338821.52 | 226.8 | 2.8 | 200435.8 | <0.0001 |

| 2 | 185 | 596.8 | 2022/1/1 - 2022/2/28 | 265939620 | 102534 | 46982.8 | 238.7 | 2.26 | 25385.5 | <0.0001 |

| 3 | 136 | 460.7 | 2022/1/1 - 2022/2/28 | 183056436 | 66092 | 32340.1 | 223.5 | 2.08 | 13821.2 | <0.0001 |

| 4 | 270 | 940.7 | 2022/7/1 - 2022/7/31 | 260730168 | 34459 | 24202.3 | 155.7 | 1.43 | 1949.1 | <0.0001 |

| 5 | 1 | - | 2022/9/1 - 2022/10/31 | 1933320 | 1139 | 353.1 | 352.8 | 3.23 | 548.1 | <0.0001 |

| 6 | 1 | - | 2021/10/1 - 2021/11/30 | 935196 | 477 | 170.8 | 305.4 | 2.79 | 183.7 | <0.0001 |

| 7 | 1 | - | 2021/8/1 - 2021/8/31 | 1228764 | 340 | 114.1 | 326 | 2.98 | 145.4 | <0.0001 |

| 8 | 3 | 30.5 | 2021/8/1 - 2021/9/30 | 2045316 | 687 | 373.6 | 201.1 | 1.84 | 105.1 | <0.0001 |

| 9 | 3 | 42.4 | 2021/8/1 - 2021/8/31 | 2851284 | 523 | 264.7 | 216.1 | 1.98 | 97.9 | <0.0001 |

| 10 | 1 | - | 2021/10/1 - 2021/11/30 | 1079256 | 399 | 197.1 | 221.4 | 2.02 | 79.5 | <0.0001 |

| 11 | 3 | 18.8 | 2022/11/1 - 2022/11/30 | 4898124 | 729 | 440 | 181.2 | 1.66 | 79.1 | <0.0001 |

| 12 | 2 | 10.2 | 2022/7/1 - 2022/7/31 | 2115732 | 392 | 196.4 | 218.3 | 2.00 | 75.3 | <0.0001 |

| 13 | 1 | - | 2021/11/1 - 2021/11/30 | 327204 | 111 | 29.39 | 413.0 | 3.78 | 65.9 | <0.0001 |

| 14 | 1 | - | 2021/11/1 - 2021/11/30 | 770568 | 181 | 69.22 | 286.0 | 2.61 | 62.2 | <0.0001 |

| 15 | 2 | 28.36 | 2021/11/1 - 2021/11/30 | 3134412 | 488 | 281.57 | 189.6 | 1.73 | 61.9 | <0.0001 |

| 16 | 1 | - | 2021/11/1 - 2021/11/30 | 6109620 | 828 | 548.83 | 165.0 | 1.51 | 61.3 | <0.0001 |

| 17 | 1 | - | 2021/8/1 - 2021/8/31 | 519600 | 142 | 48.23 | 322.0 | 2.94 | 59.6 | <0.0001 |

| 18 | 1 | - | 2021/9/1 - 2021/11/30 | 1518444 | 642 | 413.76 | 169.7 | 1.55 | 53.8 | <0.0001 |

| 19 | 1 | - | 2021/9/1 - 2021/9/30 | 583620 | 135 | 52.43 | 281.6 | 2.58 | 45.1 | <0.0001 |

| 20 | 1 | - | 2021/8/1 - 2021/8/31 | 409716 | 103 | 38.03 | 296.2 | 2.71 | 37.7 | <0.0001 |

| 21 | 1 | - | 2021/8/1 - 2021/8/31 | 226656 | 71 | 21.04 | 369.1 | 3.37 | 36.4 | <0.0001 |

| 22 | 1 | - | 2022/4/1 - 2022/4/30 | 490020 | 110 | 44.02 | 273.3 | 2.50 | 34.8 | <0.0001 |

| 23 | 1 | - | 2022/7/1 - 2022/7/31 | 222168 | 66 | 20.62 | 350.0 | 3.20 | 31.4 | <0.0001 |

| 24 | 2 | 10.16 | 2022/11/1 - 2022/11/30 | 1297692 | 193 | 116.57 | 181.1 | 1.66 | 20.9 | <0.001 |

| 25 | 2 | 13.70 | 2022/7/1 - 2022/7/31 | 1547040 | 221 | 143.60 | 168.3 | 1.54 | 17.9 | 0.003 |

| 26 | 1 | - | 2021/11/1 - 2021/11/30 | 396072 | 71 | 35.58 | 218.2 | 2.00 | 13.6 | 0.092 |

| 27 | 1 | - | 2022/11/1 - 2022/11/30 | 512616 | 85 | 46.05 | 201.9 | 1.85 | 13.2 | 0.132 |

| 28 | 1 | - | 2021/8/1 - 2021/8/31 | 560880 | 93 | 52.06 | 195.4 | 1.79 | 13.1 | 0.146 |

| 29 | 1 | - | 2022/11/1 - 2022/11/30 | 126840 | 32 | 11.39 | 307.2 | 2.81 | 12.4 | 0.233 |

| 30 | 1 | - | 2022/7/1 - 2022/7/31 | 1832664 | 239 | 170.12 | 153.7 | 1.40 | 12.4 | 0.243 |

| 31 | 1 | - | 2021/9/1 - 2021/9/30 | 692388 | 103 | 62.20 | 181.1 | 1.66 | 11.2 | 0.536 |

| 32 | 1 | - | 2022/11/1 - 2022/11/30 | 349368 | 61 | 31.38 | 212.6 | 1.94 | 10.9 | 0.613 |

| 33 | 1 | - | 2021/11/1 - 2021/11/30 | 316968 | 54 | 28.47 | 207.4 | 1.90 | 9.1 | 0.99 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).