Introduction

Tissues in the body constantly communicate with each other to maintain metabolic balance. This process, known as tissue crosstalk, allows different organs to exchange signals and coordinate their functions (1). Rather than working independently, organs such as the liver, adipose tissue, skeletal muscle, gut, and immune system operate as parts of an interconnected system that responds to nutritional and environmental cues (1-3).

Communication between tissues is mediated by a wide range of molecules, including hormones, cytokines, metabolites, extracellular vesicles, and neural signals. These mediators carry information about energy availability, nutrient status, and inflammatory conditions (1,4,5). Through this continuous exchange of signals, the body can adjust metabolism and maintain homeostasis (1,3). When this communication becomes impaired, metabolic regulation is disturbed and disease risk increases (1,3,4).

Growing evidence suggests that many metabolic disorders, including obesity, type 2 diabetes, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, are linked to disrupted communication between organs (1-3). In these conditions, altered signaling between adipose tissue, liver, muscle, gut, and immune cells contributes to insulin resistance, chronic low-grade inflammation, and abnormal lipid accumulation (1,3,4,6). This perspective highlights that metabolic diseases should not be viewed as problems of single organs but rather as consequences of disturbed inter-organ communication (1,2,6).

Systemic metabolic homeostasis depends on tightly regulated communication between multiple organs and tissues (7). While recent advances have improved our understanding of inter-organ signaling networks and their role in metabolic control, the factors that shape and modulate these communication pathways remain an active area of research (8). Among these factors, nutrition has emerged as a central and highly modifiable regulator of tissue crosstalk (8). Beyond supplying energy and building blocks, nutrients act as signals that influence how tissues communicate with each other. The type and quality of macronutrients, the availability of micronutrients, and the presence of bioactive food compounds can all affect the release of signaling molecules such as adipokines, myokines, hepatokines, and cytokines (9-11). Through these pathways, diet helps regulate metabolic and inflammatory responses across the body.

The gut microbiota represents an important link between nutrition and tissue communication. (11-13) Dietary components strongly influence the composition and activity of gut microbes, which in turn produce metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids, bile acid derivatives, and tryptophan-related compounds (13,14,15). These microbial products act as signaling molecules that affect distant organs, including the liver, brain, adipose tissue, and immune system. In this way, the gut microbiota functions as a key mediator through which diet shapes systemic metabolic regulation (11,16). In a large multiethnic cohort study, habitual yogurt consumption (≥ once per week) was associated with specific alterations in gut microbiota composition, including shifts in bacterial taxa linked to carbohydrate fermentation and host metabolism, whereas regular probiotic supplement use was not consistently associated with microbiome features. Together, these findings highlight the potential importance of food matrix effects in modulating diet–microbiota interactions (17).

Metabolically active tissues adapt their signaling output in response to nutritional cues, forming a dynamic inter-organ communication network that regulates metabolic homeostasis (9). Disruption of this network by unhealthy dietary patterns contributes to metabolic dysfunction, whereas high-quality diets support metabolic resilience (1,16).

This review summarizes current evidence on the role of nutrition in regulating tissue crosstalk, with particular emphasis on underlying signaling mechanisms, gut microbiota–mediated interactions, and implications for metabolic health and disease.

Methods

This narrative review is based on a comprehensive evaluation of the peer-reviewed literature examining the role of nutrition in regulating inter-organ communication. Relevant articles were identified through searches of PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science using combinations of keywords related to tissue crosstalk, inter-organ communication, macronutrient quality, diet quality, gut microbiota, and metabolic health. Human studies, experimental animal studies, and mechanistic investigations published primarily in English were considered. Emphasis was placed on recent and high-quality studies that provided mechanistic insights or integrative perspectives relevant to metabolic health and disease.

Nutrition as a Modulator of Tissue Crosstalk

Macronutrients and Tissue Communication

Defining a metabolically healthy diet remains challenging, as different dietary components have been proposed to influence metabolic health. While some approaches emphasize total energy intake and caloric restriction (18-20), others highlight the role of macronutrient composition (20,21). Understanding how dietary carbohydrates, fats, and proteins contribute to metabolic regulation is therefore essential for informing healthy dietary patterns (21). Macronutrient composition is a fundamental determinant of tissue crosstalk and systemic metabolic regulation, as carbohydrates, fats, and proteins act not only as energy sources but also as regulators of tissue-derived signaling and inter-organ communication (21). From a nutritional perspective, the quality and balance of macronutrients are more relevant to inter-organ communication than total energy intake alone. Genetic and experimental studies have provided additional insights into the role of insulin signaling in energy balance, suggesting that variations in insulin secretion may influence body weight regulation; however, these effects are likely to depend on tissue-specific responses and broader dietary contexts rather than acting as isolated drivers of metabolic health (21,22). Comprehensive dietary approaches have shown that macronutrient composition is associated with distinct and recurring patterns of gene regulation related to adipose tissue function, highlighting how different macronutrients and their interactions shape metabolic signaling rather than acting in isolation (20).

Dietary Fat Quality and Inter-Organ Crosstalk

Dietary fat composition is another major modulator of tissue crosstalk. High intake of saturated fatty acids has been linked to pro-inflammatory signaling and impaired communication between adipose tissue, liver, and immune cells. These effects are often accompanied by increased secretion of pro-inflammatory adipokines and cytokines, contributing to metabolic dysfunction (31).

Dietary fatty acids differ in their biological effects on metabolic and inflammatory pathways. In contrast to saturated fatty acids, monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids have been consistently associated with anti-inflammatory effects (32). Experimental and clinical evidence suggests that these fatty acids can attenuate inflammatory signaling, partly by modulating adipokine secretion and immune cell activity (33). In particular, monounsaturated fatty acids such as oleic acid have been shown to counteract saturated fatty acid–induced metabolic stress and support a more anti-inflammatory tissue environment, contributing to improved inter-organ metabolic communication (34, 35). Polyunsaturated fatty acids, particularly marine-derived omega-3 fatty acids, are associated with anti-inflammatory effects and improved metabolic signaling across tissues. In contrast, industrial trans fatty acids are consistently linked to pro-inflammatory signaling and metabolic dysfunction (31).

Among long-chain fatty acids, α-linolenic acid (ALA), eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) are omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids that have been extensively studied as bioactive lipids with potential metabolic benefits. These fatty acids may influence metabolic health by altering tissue fatty acid composition and modulating cell signaling pathways (36). Omega-3 fatty acids are derived from both plant-based sources, such as nuts and seeds, and marine sources, which provide preformed EPA and DHA (37).

Beyond their anti-inflammatory properties, marine-derived omega-3 fatty acids have been shown to influence energy metabolism and mitochondrial function across multiple metabolic tissues, including skeletal muscle, liver, and adipose tissue (36). Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 PUFAs) have gained increasing attention for their potential to modulate adipose tissue metabolism, reduce inflammatory signaling, and influence thermogenic capacity (37). Experimental and nutrition-focused studies suggest that n-3 PUFAs may contribute to white adipose tissue browning and brown adipose tissue activation, thereby supporting improved energy expenditure and metabolic flexibility (38-40). For example, in a mouse model of high-fat diet–induced obesity, dietary supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids has been shown to improve metabolic parameters and adipose tissue morphology without altering energy intake. In this experimental context, omega-3 fatty acids partially preserved brown adipose tissue structure, prevented diet-induced BAT whitening, and promoted features of white adipose tissue browning, alongside reduced inflammatory infiltration. These findings support the concept that dietary fat quality, rather than energy intake alone, can influence adipose tissue remodeling and inter-organ metabolic communication under conditions of excess energy intake (38). However, while these effects are well documented in preclinical models, further human studies are needed to clarify the magnitude and clinical relevance of n-3 PUFA–induced adipose tissue remodeling (41). Experimental studies suggest that omega-3 fatty acids may enhance fatty acid oxidation, improve mitochondrial function in skeletal muscle and liver, and support adaptive thermogenic responses in adipose tissue. Through these tissue-specific effects, omega-3 fatty acids may contribute to coordinated inter-organ communication that supports metabolic flexibility, particularly under conditions of high-fat feeding (36-38). Consistent with these observations, experimental studies suggest that diets enriched with omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids may reduce ectopic lipid accumulation in skeletal muscle and improve markers of oxidative stress and insulin sensitivity when compared with isocaloric diets rich in saturated fatty acids (38). However, most mechanistic evidence is derived from animal models, and the extent to which these adaptations translate to human metabolic health remains to be fully established (41). Although n-3 fatty acids are recognized for their anti-inflammatory and lipid-regulating properties, further research is needed to clarify their role in promoting white adipose tissue browning and brown adipose tissue activation (38-41). Moreover, the doses used in animal studies often exceed typical human dietary intakes, which limits direct translation to nutritional recommendations (41,42).

Protein Intake and Metabolic Communication

Protein quality is an important determinant of how dietary proteins influence metabolic and immune responses across tissues (43). Beyond total protein intake, factors such as amino acid composition, digestibility, food matrix, and accompanying bioactive compounds shape protein-derived signaling and inter-organ communication (44). Amino acids provide essential substrates for protein synthesis and the production of immune mediators, including cytokines, antibodies, and enzymes involved in inflammatory responses, thereby contributing to metabolic and immune homeostasis (9, 45).

Different protein sources may elicit distinct metabolic and inflammatory profiles (46). Animal-based proteins are generally characterized by greater digestibility and higher amino acid bioavailability, whereas plant-based proteins exhibit distinct structural and compositional features that may limit the availability of certain essential amino acids but are often consumed within complex food matrices containing dietary fiber and other bioactive compounds (47,48). Although dairy products are among the richest sources of bioactive peptides, such peptides can also be derived from a wide range of dietary proteins; however, differences in processing and food matrix characteristics may confer distinct physiological effects across protein sources (48). In a recent study, differences in processing and fermentation were demonstrated to generate distinct dairy matrices, thereby modulating nutrient digestion, bioavailability, and downstream metabolic effects (49). Together, these matrix-associated components may shape postprandial metabolic responses and regulate tissue crosstalk through gut-mediated and immune-related pathways.

Emerging evidence suggests that protein quality can affect tissue communication by modulating insulin sensitivity, inflammatory tone, and gut microbiota composition (50). Protein ingestion triggers coordinated responses across the gut, pancreas, liver, skeletal muscle, and adipose tissue, influencing amino acid availability, insulin secretion, and downstream metabolic signaling. The metabolic effects of protein sources therefore reflect not only their amino acid content but also the broader dietary context in which proteins are consumed (46, 48).

Experimental evidence from animal models of diet-induced obesity further supports this concept. In a mouse model of high-fat feeding, supplementation with different dairy products reduced weight gain and increased energy expenditure, with distinct tissue-specific responses. Milk and yogurt were associated with enhanced brown adipose tissue thermogenic activity and alterations in lipid metabolism, whereas cheese increased energy expenditure without activating thermogenic pathways (49). These findings illustrate how protein source and food form may shape inter-organ metabolic communication, although their relevance to human physiology should be interpreted with caution.

Plant-based protein sources have gained increasing attention for their potential role in supporting metabolic health (46,48). Although plant proteins may exhibit lower anabolic potency compared with some animal proteins, their consumption is often associated with lower inflammatory markers and improved metabolic profiles when incorporated into balanced dietary patterns (31,46,48). These effects may be mediated through combined influences on gut microbiota–derived metabolites, immune cell activity, and adipose tissue signaling rather than isolated amino acid effects (11,15,50).

Importantly, the metabolic impact of protein quality appears to be context dependent (43,48). Factors such as overall energy balance, body composition, and prior weight gain may influence how different protein sources affect tissue communication (44,49). In particular, understanding how plant-based protein sources influence inter-organ communication following weight gain represents a promising but understudied area. Addressing this gap may have important implications for developing sustainable dietary strategies aimed at improving metabolic resilience.

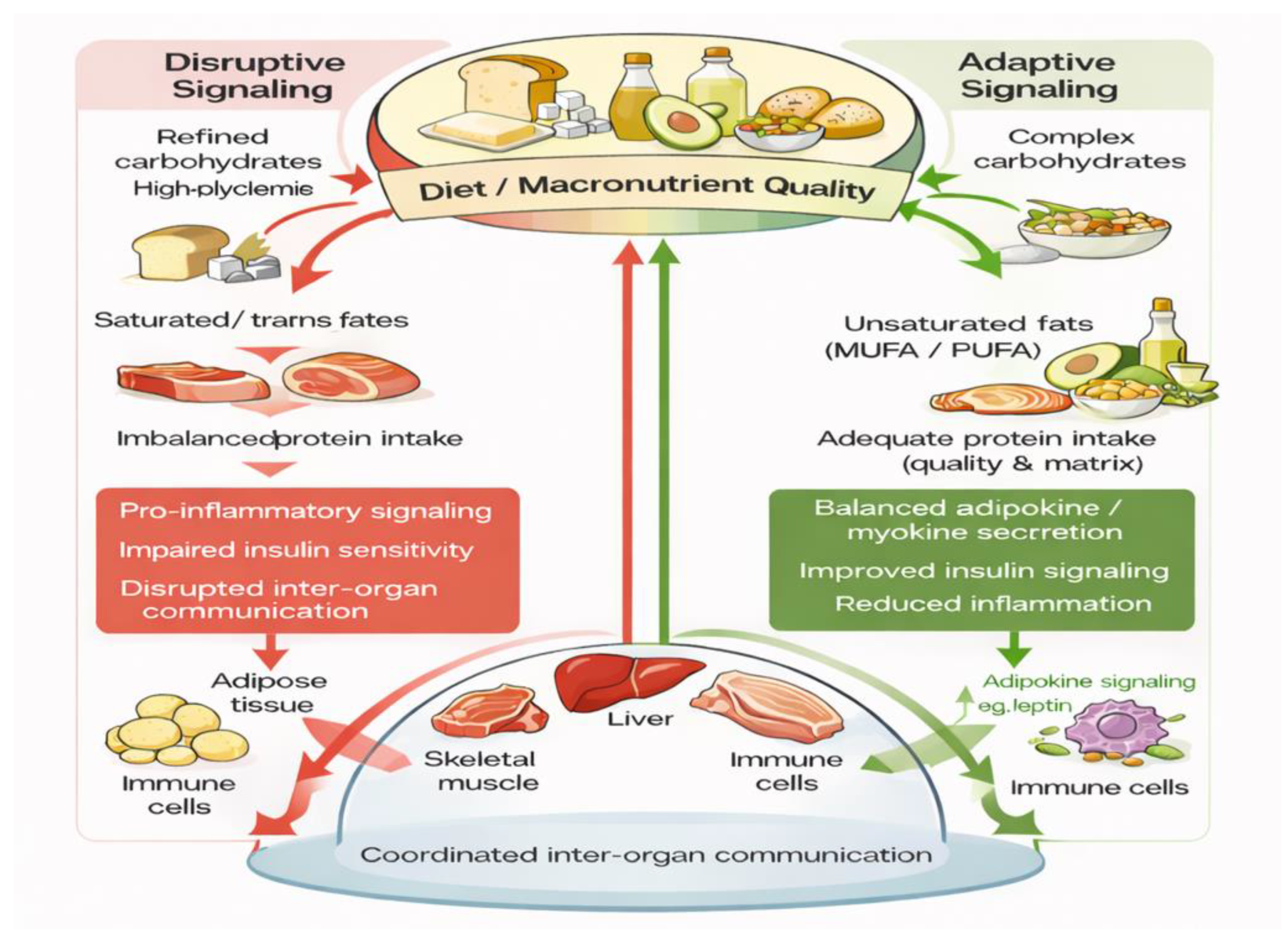

Diets rich in refined carbohydrates, saturated fats, and imbalanced protein intake promote disruptive signaling characterized by impaired insulin sensitivity, pro-inflammatory responses, and altered tissue crosstalk. In contrast, dietary patterns emphasizing complex carbohydrates, unsaturated fats, and adequate protein intake support adaptive signaling, balanced adipokine and myokine secretion, improved insulin signaling, and reduced inflammation, thereby promoting coordinated communication among adipose tissue, liver, skeletal muscle, gut, and immune cells.

Conclusion and Future Perspectives

Nutrition plays a central role in coordinating communication between tissues by shaping metabolic, inflammatory, and endocrine signaling across the body. Rather than acting through single pathways, macronutrients influence inter-organ communication through their quality, composition, and the context in which they are consumed, with important consequences for metabolic balance and disease risk.

The evidence reviewed here shows that carbohydrate quality, dietary fat type, and protein source can differentially affect tissue-specific signaling, partly through mechanisms involving the gut microbiota. Emerging findings also indicate that the metabolic effects of dietary protein quality are not uniform, but instead depend on factors such as energy balance, body composition, and prior weight gain.

Despite growing progress in this field, key questions remain about how overall dietary patterns—particularly those rich in plant-based protein sources—shape tissue communication under conditions of sustained energy excess. Addressing these questions through integrated experimental and human studies may help guide nutritional strategies that support metabolic resilience beyond weight loss alone.

Figure 1.

Macronutrient quality as a regulator of tissue crosstalk. Schematic illustration showing how macronutrient quality influences inter-organ communication. Diets rich in refined carbohydrates, saturated and trans fats, and imbalanced protein intake are associated with disruptive signaling characterized by impaired insulin sensitivity, pro-inflammatory responses, and altered communication among adipose tissue, liver, skeletal muscle, gut, and immune cells. In contrast, dietary patterns emphasizing complex carbohydrates, unsaturated fats, and adequate protein intake support adaptive signaling, balanced adipokine and myokine secretion, improved insulin signaling, and reduced inflammation, thereby promoting coordinated inter-organ communication.

Figure 1.

Macronutrient quality as a regulator of tissue crosstalk. Schematic illustration showing how macronutrient quality influences inter-organ communication. Diets rich in refined carbohydrates, saturated and trans fats, and imbalanced protein intake are associated with disruptive signaling characterized by impaired insulin sensitivity, pro-inflammatory responses, and altered communication among adipose tissue, liver, skeletal muscle, gut, and immune cells. In contrast, dietary patterns emphasizing complex carbohydrates, unsaturated fats, and adequate protein intake support adaptive signaling, balanced adipokine and myokine secretion, improved insulin signaling, and reduced inflammation, thereby promoting coordinated inter-organ communication.

Funding

This work received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgments

The author declares that this manuscript was written independently. Artificial intelligence–based tools were used solely for English language editing and stylistic refinement. The scientific content, interpretation, and conclusions are entirely those of the author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Hotamisligil, G.S. Inflammation, metaflammation and immunometabolic disorders. Nature 2017, 542, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oishi, Y.; Manabe, I. Organ system crosstalk in cardiometabolic disease in the age of multimorbidity. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2020, 7, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, V.T.; Shulman, G.I. The pathogenesis of insulin resistance: integrating signaling pathways and substrate flux. J Clin Invest. 2016, 126, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.S.; Wollam, J.; Olefsky, J.M. An integrated view of immunometabolism. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 933–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, E.L.; Gudgeon, N.; Dimeloe, S. Control of T cell metabolism by cytokines and hormones. Front Immunol. 2021, 12, 653605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilg, H.; Moschen, A.R. Evolution of inflammation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: the multiple parallel hits hypothesis. Hepatology 2010, 52, 1836–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katagiri, H. Inter-organ communication involved in metabolic regulation at the whole-body level. Inflamm Regen. 2023, 43, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priest, C.; Tontonoz, P. Inter-organ cross-talk in metabolic syndrome. Nat Metab. 2019, 1, 1177–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo-Armengol, J.; Fajas, L.; Lopez-Mejia, I.C. Inter-organ communication: a gatekeeper for metabolic health. EMBO Rep. 2019, 20, e47903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira Dos Santos, A.R.; de Oliveira Zanuso, B.; Miola, V.F.B.; et al. Adipokines, myokines, and hepatokines: crosstalk and metabolic repercussions. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22, 2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saponaro, F.; Bertolini, A.; Baragatti, R.; et al. Myokines and microbiota: new perspectives in the endocrine muscle–gut axis. Nutrients 2024, 16, 4032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.; Pedersen, O. Gut microbiota in human metabolic health and disease. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021, 19, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Liu, J.; Cheng, H.; et al. Dietary compounds in modulation of gut microbiota-derived metabolites. Front Nutr. 2022, 9, 939571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridlon, J.M.; Kang, D.J.; Hylemon, P.B.; Bajaj, J.S. Bile acids and the gut microbiome. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2014, 30, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agus, A.; Clément, K.; Sokol, H. Gut microbiota-derived metabolites as central regulators in metabolic disorders. Gut 2021, 70, 1174–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Tan, Y.; Cheng, H.; et al. Functions of gut microbiota metabolites: current status and future perspectives. Aging Dis. 2022, 13, 1106–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, W.; Maskarinec, G.; Lim, U.; et al. Association of habitual intake of probiotic supplements and yogurt with characteristics of the gut microbiome in the multiethnic cohort adiposity phenotype study. Gut Microbiome 2023, 4, e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thom, G.; Lean, M. Is there an optimal diet for weight management and metabolic health? Gastroenterology 2017, 152, 1739–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, D.S.; Willett, W.C.; Volek, J.S.; Neuhouser, M.L. Dietary fat: from foe to friend? Science 2018, 362, 764–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farris, K.M.; Senior, A.M.; Sobreira, D.R.; et al. Dietary macronutrient composition impacts gene regulation in adipose tissue. Commun Biol. 2024, 7, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludwig, D.S.; Ebbeling, C.B. The carbohydrate–insulin model of obesity: beyond “calories in, calories out”. JAMA Intern Med. 2018, 178, 1098–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehran, A.E.; Templeman, N.M.; Brigidi, G.S.; et al. Hyperinsulinemia drives diet-induced obesity independently of brain insulin production. Cell Metab. 2012, 16, 723–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffarian, D. Dietary and policy priorities for cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and obesity. Circulation 2016, 133, 187–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriadis, G.D.; Maratou, E.; Kountouri, A.; et al. Regulation of postabsorptive and postprandial glucose metabolism. Nutrients 2021, 13, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Jiang, W.; Guo, S. Regulation of macronutrients in insulin resistance and glucose homeostasis during type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papakonstantinou, E.; Oikonomou, C.; Nychas, G.; Dimitriadis, G.D. Effects of diet and lifestyle on postprandial glycemia and insulin resistance. Nutrients 2022, 14, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Fan, M.; Qian, H.; et al. Whole grain-derived functional ingredients against hyperglycemia. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2024, 64, 7268–7289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Rayner, C.K.; Jones, K.; Horowitz, M. Dietary effects on incretin hormone secretion. Vitam Horm. 2010, 84, 81–110. [Google Scholar]

- Nauck, M.A.; Müller, T.D. Incretin hormones and type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 2023, 66, 1780–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.Y.; Gautier, J.F.; Chon, S. Assessment of insulin secretion and insulin resistance in humans. Diabetes Metab J. 2021, 45, 641–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosso, G.; Laudisio, D.; Frias-Toral, E.; et al. Anti-inflammatory nutrients and obesity-associated metabolic inflammation. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crick, D.C.P.; Halligan, S.L.; Davey Smith, G.; et al. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and inflammation. Int J Epidemiol. 2025, 54, dyaf065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radzikowska, U.; Rinaldi, A.O.; Çelebi Sözener, Z.; et al. Influence of dietary fatty acids on immune responses. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva Figueiredo, P.; Inada, A.C.; Marcelino, G.; et al. Fatty acid consumption and obesity-related disorders. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravaut, G.; Légiot, A.; Bergeron, K.F.; Mounier, C. Monounsaturated fatty acids in obesity-related inflammation. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 22, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, I.; Hussain, M.; Jiang, B.; et al. Omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids: metabolism and health implications. J Food Compos Anal. 2023, 114, 104864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djuricic, I.; Calder, P.C. n-3 fatty acids (EPA and DHA) and cardiovascular health. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2025, 27, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saban Güler, M.; Yıldıran, H.; Seymen, C.M. Effect of omega-3 fatty acids on adipose tissue in mice fed a high-fat diet. Sci Rep. 2025, 15, 37179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Galilea, M.; Félix-Soriano, E.; Colón-Mesa, I.; Moreno-Aliaga, M.J. Omega-3 fatty acids as regulators of brown/beige adipose tissue. J Physiol Biochem. 2020, 76, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M.; Xu, T.; Xu, Y.J.; Liu, Y. Dietary fatty acids activate or deactivate brown and beige fat. Life Sci. 2023, 330, 121978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negroiu, C.E.; et al. Beyond the cold: activating brown adipose tissue to combat obesity. J Clin Med. 2024, 13, 1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pahlavani, M.; et al. Eicosapentaenoic acid regulates brown adipose tissue metabolism. J Nutr Biochem. 2017, 39, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfe, R.R.; Church, D.D.; Ferrando, A.A.; Moughan, P.J. Role of protein quality in dietary protein recommendations. Front Nutr. 2024, 11, 1389664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petzke, K.J.; Freudenberg, A.; Klaus, S. Dietary protein beyond amino acids in obesity prevention. Int J Mol Sci. 2014, 15, 1374–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Chang, C.; Zhao, S.; et al. Amino acids shape the metabolic and immunologic landscape in the tumor immune microenvironment. Cancer Biol Med. 2025, 22, 726–746. [Google Scholar]

- Mariotti, F.; Gardner, C.D. Dietary protein and amino acids in vegetarian diets. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, L.; Mao, B.; Beniwal, A.S.; et al. Alternative proteins vs animal proteins: influence of structure and processing. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2022, 122, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajomiwe, N.; Boland, M.; Phongthai, S.; et al. Protein nutrition: structure, digestibility, and bioavailability. Foods 2024, 13, 1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuzbashian, E.; Fernando, D.N.; Jacobs, R.L.; et al. Effects of milk, yogurt, and cheese on metabolic outcomes in obese mice. Int J Mol Sci. 2025, 26, 5026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendis, B.I.L.M.; Sarvananda, L.; Jayasinghe, T.N.; et al. Gut microbiota and type 2 diabetes: mechanisms and mediators. Med Microecol. 2025, 26, 100144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |