1. Overview of Cancer-Associated Microenvironments

The tumor microenvironment (TME) is a dynamic and intricate network made up of blood vessels, stromal cells, immune cells, cancer cells, and extracellular matrix factors. Pathogens, including bacteria, viruses, and fungi, have recently gained attention for their ability to influence the tumor microenvironment and contribute to tumor developing towards a more advanced state. TME’s are shaped by the cellular and molecular components of the tumor but is also impacted by the presence of pathogens that interact with the immune system, metabolic pathways, and genetic stability of the host. This interaction between the host and pathogens can either promote or decline tumorigenesis since it is dependent on the type of pathogen and the immune responses (Hanahan & Weinberg, 2011). This is due to the involvement of microbial dysbiosis in the development of several cancers, including gastric and colorectal cancers. This signifies that the microbiome may play a crucial role in shaping the TME (Schwabe & Jobin, 2013).

The pathogens such as F. nucleatum, Helicobacter pylori, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), and human papillomavirus have been identified as contributing factors in cancer initiation and progression. For instance, H. pylori is a known carcinogen linked to stomach cancer, mainly because of its ability to promote immune evasion, DNA damage, and chronic inflammation (Duan et al., 2025). Similarly, F. nucleatum, which is commonly found in the gut microbiota, and it is involved colorectal cancer through its role in promoting inflammation and modulating immune responses (Li et al., 2025). The presence of these pathogens creates a chronic inflammatory state that fosters a pro-tumorigenic environment, encouraging cancer cell survival and metastasis.

The recent advancements have allowed for a more comprehensive knowledge of host-pathogen interactions in tumor microenvironments. Researchers can analyse the molecular layers to understand how the infections affect host gene expression, immunological signaling pathways and metabolic networks that promote tumor growth (Nejman et al., 2020; Riquelme et al., 2019). Such a comprehensive technique demonstrates that the tumor microbiome while influencing immune evasion create distinct molecular signatures that can be exploited for biomarker discovery and precision medicine in cancer care.

1.1. Mechanisms of Host–Pathogen–Tumor Interactions

The mechanism of tumor initiation is by persistent infection that creates long-standing inflammatory state in the tissues. For instance, H. pylori infection of the gastric mucosa leads to epithelial damage, DNA lesions and oxidative stress and dysfunctional signaling system leading to gastric carcinogenesis (Zhang et al., 2025). Recent studies such as persistent pathogen infection by viruses, bacteria and parasites disrupt host immunity by leading the cause of genomic instability setting the course of tumor formation (Rembiałkowska et al., 2025). A 2025 review of pathogens-associated tumor microenvironments emphasized that chromic infection promotes an immunosuppressive, pro-inflammatory environment supporting tumor formation and progression (Chen et al., 2024).

Additionally, after the succession of infection, the pathogen hijacks the host’s cell which it uses to for survival, replication and immune evasion which they promote carcinogenesis. For instance, viral oncoproteins may inactivate tumor suppressors, activate proliferation-linked kinases or integrate into the hosts genome. A structural review in 2023 about host-pathogen protein-protein interactions show how pathogens exploit host signaling by binding to pockets which alters the host’s immunological defenses (Steiert & Weber, 2025).This phenomenon has been reiterated by studies which emphasized the genetic integration , modulation f regulatory networks and epigenetic reprogramming by microbial factors (Latif et al., 2025).

1.2. Immune Modulation

The immune system if the host is involved in defending the against and developing tumors cells. The pathogen however suppresses the immune response which in turn benefits the tumor cells by helping it evade immune surveillance. For instance, persistent pathogens induce regulatory T-cell (Treg) expansion, myeloid suppressor cells (MDSCs), M2 macrophage polarization and CD8+ T cells are all evident in a tumor microenvironment. Recent studies suggest that pathogen-associated tumor micro-environment highlights the relation between immunosuppression becomes incorporated into the tumorigenesis (Wei et al., 2025)

1.3. Chronic Inflammation & Signaling Pathways

Chronic inflammation in the tumor microenvironment promotes carcinogenesis by activating essential signaling pathways like NF-kB and MAPK. The persistent microbial infection and immunological dysregulation cause the release of cytokines IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β which maintains NF-kβ. This pathway stimulates gene transcription for cell survival, proliferation and angiogenesis which contributes to tumor persistence (Laha et al., 2021). MAPK signaling which is triggered by pathogen-derived ligands which binds to Toll-like receptors. This leads to inflammation and neoplastic transformation by the activating ERK and JNK altering cell-cycle checkpoints and apoptosis resistance (Arner & Rathmell, 2023). NLRP3 which is an inflammasome detects pathogen -associated molecular patterns (PAMPS) and damage associated molecular pumps (DAMPS). This inflammasome causes persistent IL-1β and IL-18 which promotes DNA damage and immunological infiltration (Vargas-Castellanos & Rincón-Riveros, 2025). Pathogen-associated tumors use the inflammasome signaling to set up a feedback loop of oxidative stress and immune suppression which accelerates tumor progression

1.4. Genomic Instability

One mechanism of DNA damage is the reactive-oxygen species which is from the consequence of persistent inflammatory signaling. This happens when infiltrating macrophages and neutrophils in the TME reactive oxygen and nitrogen species that causes the unwinding of the double helix structure, alters the purine and pyrimidine bases and replication stress which leads to mutagenic load (Anuja et al., 2017). Chronic infection increases this effect causing metabolic changes and increasing mitochondrial reactive oxygen species generation. Furthermore, viral oncoproteins of E6/E7 and LMP1 disrupt the host DNA repair and epigenetic control leading to chromosomal instability and oncogene amplification (Xiao et al., 2025). These viral sequences function as transcriptional enhancers alters neighboring host-gene expression as oncogenic status. Through multi-omics analyses, Wei et al. (2025) demonstrated that HPV and EBV integration events correlate with detectable mutational signatures in whole-genome sequencing and transcriptomics data. These signatures hold potential as novel diagnostic biomarkers for virus-associated malignancies.

1.5. Metabolic Reprogramming

Within the tumor-microenvironment, metabolic reprogramming driven by pathogens metabolic reprogramming is an important component of host-tumor interactions. Confronted with pathogenic and hypoxic stressors, tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) undergo metabolic polarization shifting their primary energy pathway toward from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolytic lactate generation. This metabolic shift drives immunosuppression by depletion of essential amino acids (arginine and tryptophan), required for T-cell activation, this mechanism induces immunosuppression and facilitates tumor development (Chang & Ho, 2025).

2. The Role of Host-Pathogen Interactions in Cancer Progression

Pathogens can influence the TME in several ways, including by modulating immune responses, inducing chronic inflammation, and causing genetic instability. These interactions are implicated in tumor initiation, progression, and metastasis. Inflammation creates a microenvironment that supports cancer cell proliferation, survival, and invasion. Chronic inflammation is frequent in H. pylori and EBV infections and contributes to tumorigenesis by activating inflammatory signaling pathways, such as NF-κB and MAPK. These pathways are involved in cell proliferation, immune suppression, and DNA damage (Grivennikov et al., 2010). The activation then promotes transcription of inflammatory mediators such as IL-8, TNF and COX-2 which supports epithelial proliferation and survival under oxidative stress (Baral et al., 2024).

Furthermore, pathogens can manipulate immune responses within the TME to evade immune surveillance. For example, F. nucleatum promotes immune evasion by enhancing the expression of immune checkpoint molecules, such as PD-1 and CTLA-4. These functional molecules which suppress anti-tumor T cell activity (Xu et al., 2021). Similarly, viruses like EBV and HPV can modulate immune responses by interfering with antigen presentation and T cell activation, which allows the tumor cells to evade immune detection (Tsao et al., 2015). By altering the immune landscape of the TME, pathogens can help tumors escape immune surveillance and resist immunotherapies.

In addition to immune modulation, pathogens can induce genomic instability in host cells. Chronic infections caused by pathogens like H. pylori and HPV lead to the accumulation of mutations, which increase the risk of cancer. H. pylori induces DNA damage through the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), leading to mutations in gastric epithelial cells (Murata-Kamiya & Hatakeyama, 2022). Similarly, the integration of HPV’s genome into the host genome can activate oncogenes that disrupt normal cell cycle regulation enhancing the development of cervical cancer (Porter & Marra, 2022).

Pathogens also influence metabolic processes within the TME. By altering nutrient availability and metabolite production, pathogens can affect tumor cell growth and survival. F. nucleatum and other microbial species have been shown to alter the local metabolic environment, leading to changes in cancer cell metabolism that favor tumor progression (Li et al., 2025). Pathogen-induced changes in the tumor microenvironment, including alterations in glucose metabolism and amino acid availability, can promote the survival of cancer cells in nutrient-limited environments. In addition to modifying glucose uptake, intratumoural Helicobacter pylori transforms tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) into a state characterized by oxidative phosphorylation dominance, making them resistant to PD-1 inhibition (Su et al., 2022) . Real-time Seahorse flux study of TAMs isolated from H. pylori-positive gastric tumors demonstrates a 2.3-fold elevation in the basal oxygen consumption rate relative to uninfected controls (Kidane, 2018). Pharmacological reversal with dichloroacetate, a pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase inhibitor, reinstates glycolytic flow and re-sensitizes tumors to anti-PD-1 therapy in animal models (Wang et al., 2019). These findings underscore metabolic symbiosis as a targetable weakness in pathogen-driven malignancies.

Together, these interactions between pathogens and host cells in the TME create a favorable environment for cancer progression. Pathogens not only contribute to tumor initiation through genetic instability but also support the growth and metastasis of tumors by inducing inflammation, immune evasion, and metabolic alterations. These complex interactions are essential for identifying new therapeutic interventions to target the microbial influences on cancer and improve treatment outcomes.

3. Bacterial, Viral, and Fungal Pathogens in the Tumor Microenvironment

`. Bacteria

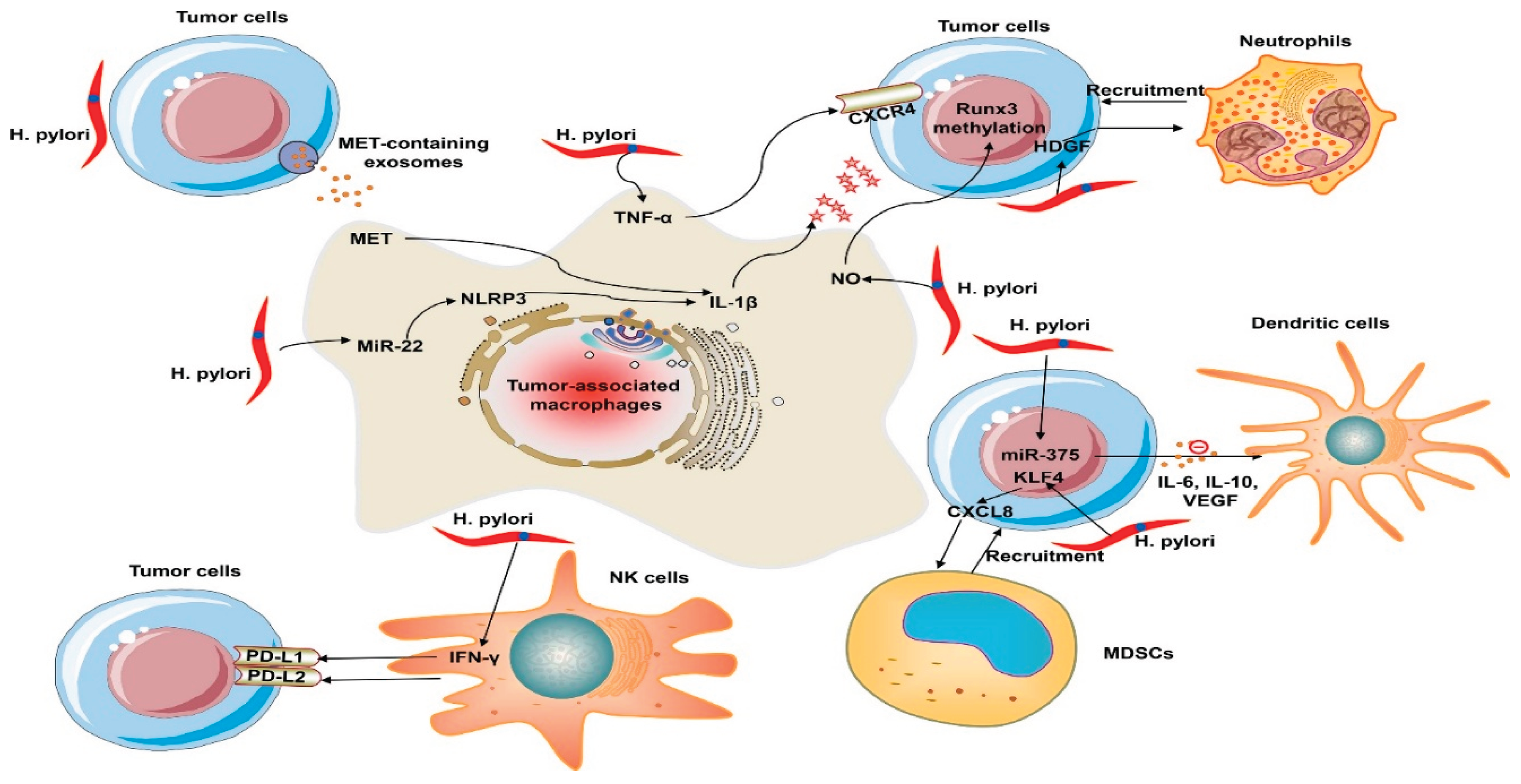

H. pylori is a class 1 carcinogen in gastric cancer and it drives stromal and immune reprogramming towards fibrous connective tissue, EMT and neoplastic transformation. This is mediated partially by the M2 macrophage polarization controlled by microRNAs such as let-7i-5p and miR-185-5p (Zhu et al., 2022). furthermore, H. pylori upregulates PD-L1 in gastric epithelial cells through Sonic Hedgehog pathway and the CagA-p53-miR34 signaling pathway which leads to CD8+ T-cells contributing to immune-cold microenvironment associated with poor prognosis (Liu et al., 2022). This process coincides with HKDC1 upregulation, overexpression, TGF-β/Smad2 activation, and EMT induction all lead to increased tumor invasiveness and metastasis (Yu et al., 2025).

Beyond H. pylori, recent studies shows that bacteria in the tumor microenvironment (TME) affect the progression of cancer through immunometabolic and signaling pathways. Bacteria extravesicular vesicles (BEVs)transfer toxins, RNA and quorum sensing molecules to host cells (Liang et al., 2024). Additionally, these vesicles transport compounds such ass peptidoglycan fragments and short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which activate NOD-like receptors and prolong DNA damage and chronic inflammation. In the meantime, bacterial consortia can coordinate adaptive responses within the TME through quorum-sensing (QS) signaling. This action then recruits macrophages, stimulates the formation of newer blood vessels while using acyl-homoserine lactone signaling to prevent lymphocyte cytoxicity (Duan et al., 2025). Additionally, by inhibiting antigen presentation, increasing glycolysis, and fostering treatment resistance, microbial metabolites such as butyrate, indole derivatives, and lactate reprogram tumor metabolism (Jiang et al., 2022; Zhou et al., 2024). While certain bacteria regulate PD-L1 expression or supply immunosuppressive mimetics that change responses to checkpoint blockade treatment, others express β-glucuronidase, which metabolizes chemotherapeutic drugs and promotes resistance (Bhanu et al., 2025).

Figure 1.

Immune evasion mechanisms of H. pylori within the tumor microenvironment. Reproduced from Shrestha E., Kim S., & Kim S. G. (2022). Emerging role of Helicobacter pylori in the immune evasion mechanism of gastric cancer: An insight into tumor microenvironment–pathogen interaction. Frontiers in Oncology, 12, 862462.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.862462.

Figure 1.

Immune evasion mechanisms of H. pylori within the tumor microenvironment. Reproduced from Shrestha E., Kim S., & Kim S. G. (2022). Emerging role of Helicobacter pylori in the immune evasion mechanism of gastric cancer: An insight into tumor microenvironment–pathogen interaction. Frontiers in Oncology, 12, 862462.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.862462.

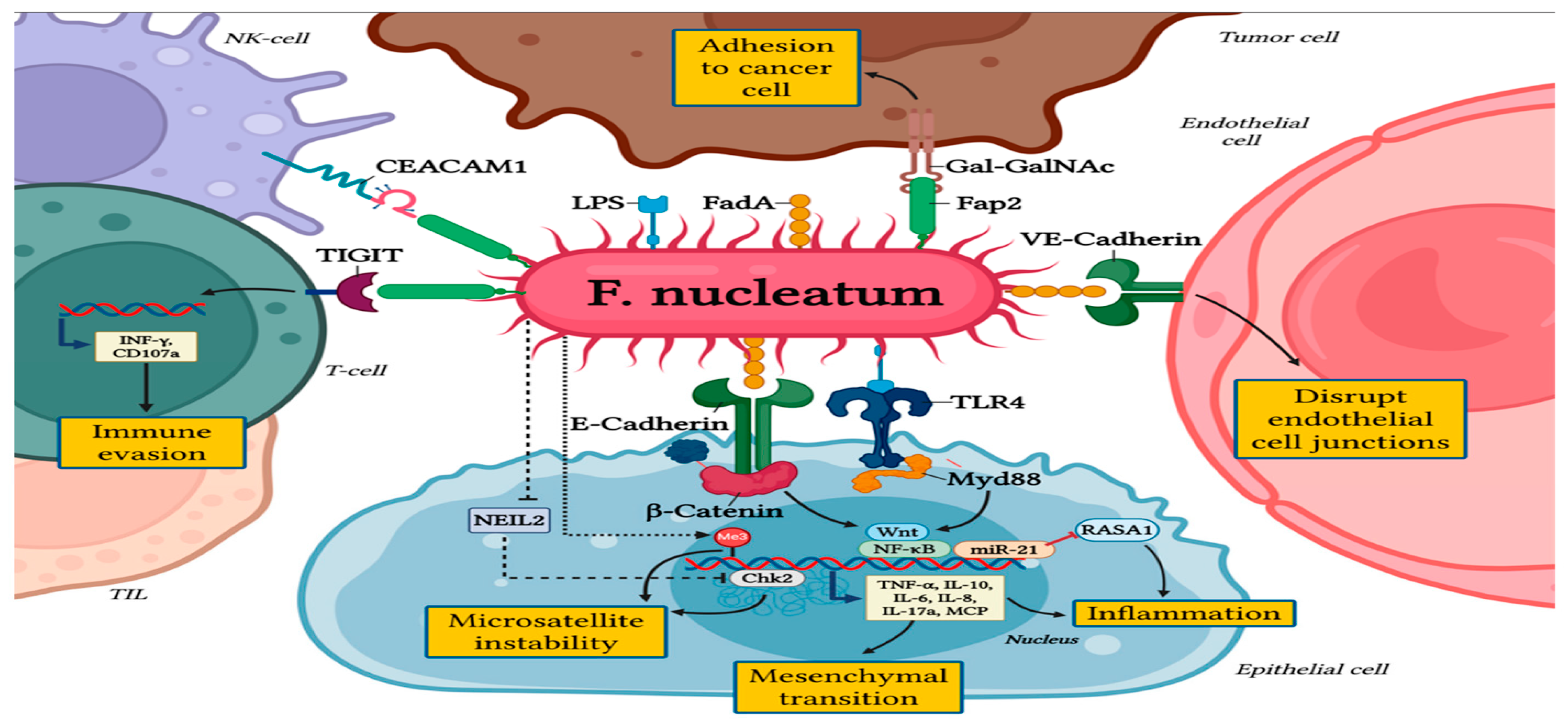

Similarly, the presence of Fusobacterium nucleatum in the colorectal cancer (CRC) microenvironment, affects tumor growth by fostering inflammation, altering immunological responses and treatment resistance. Fusobacterium nucleatum influence the TME by activating inflammatory responses (NF-κB, IL-6, IL-8), and regulating the formation of new blood cells via IL-1β and endothelial activation. Additionally, altering microRNA and chemokine activation delivered by exosomes and promoting tumor cell migration and lymph node metastasis (Galasso et al., 2025).

Fusobacterium nucleatum attached to the host E-cadherin through adhesin FadA which triggers β-catenin signaling thereby enhancing cell proliferation and invasion (Rubinstein et al., 2013). Moreover, its impact on immune compartment of the TME is significant: Elevated levels of F. nucleatum have been associated with diminished infiltration of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and the upregulation of immunosuppressive populations (e.g., CD66b+ granulocytes, ARG1+ myeloid cells, CTLA-4 expression) (Li et al., 2025). However, F. nucleatum, has also been shown to both hinder and enhance responsiveness toto immune checkpoint blockade (ICB). Meanwhile other studies suggests that the succinate produced by F. nucleatum suppresses IFNy/TNF and reduces CD8+ count infiltration (Shigematsu et al., 2024).

Figure 2.

The pro-tumorigenic role of Fusobacterium nucleatum in colorectal cancer. Reproduced from Galasso, L., Termite, F., Mignini, I., Esposto, G., Borriello, R., Vitale, F., Nicoletti, A., Paratore, M., Ainora, M. E., Gasbarrini, A., & Zocco, M. A. (2025). Unraveling the Role of Fusobacterium nucleatum in Colorectal Cancer: Molecular Mechanisms and Pathogenic Insights. Cancers, 17(3), 368.

https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17030368.

Figure 2.

The pro-tumorigenic role of Fusobacterium nucleatum in colorectal cancer. Reproduced from Galasso, L., Termite, F., Mignini, I., Esposto, G., Borriello, R., Vitale, F., Nicoletti, A., Paratore, M., Ainora, M. E., Gasbarrini, A., & Zocco, M. A. (2025). Unraveling the Role of Fusobacterium nucleatum in Colorectal Cancer: Molecular Mechanisms and Pathogenic Insights. Cancers, 17(3), 368.

https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17030368.

Clostridium novyi-NT and attenuated Salmonella typhimurium demonstrate significant efficiency in mouse cancers; nevertheless, human malignancies are characterized by hypoxia and inadequate perfusion (Sears, 2018). Microdialysis of excised human colorectal tumors demonstrated that intravenously injected Salmonella attains merely 1.2% penetration into the tumor radius (Cuellar-Gómez et al., 2022). Alternatively, tea-polyphenol-armored Akkermansia muciniphila endures stomach acid and enhances anti-PD-1 activity in gnotobiotic mice (Routy et al., 2018) These pharmacokinetic data are essential for logical dose determination in first-in-human trials.

3.2. Viruses

Viral pathogens such as Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and human papillomavirus (HPV) are associated with several types of cancer. EBV is recognized as a significant carcinogen in nasopharyngeal carcinoma and certain lymphomas, mainly due to its capacity to facilitate immune evasion and modify cellular pathways.

3.2.1. Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV)

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is a ubiquitous gammaherpes virus that is involved in malignancies such as gastric carcinoma, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, and other lymphomas. The primary cause of EBV’s potential is its potential to alter the host immunological and epigenetic within the tumor microenvironment. Additionally, it has the potential to evade immune evasion and persistent latency that promote tumor growth.

EBV uses a variety of latency programs to promote cell proliferation and resistance to apoptosis and express a specific set of genes. These include latent membrane protein (LMP1 and LMP2A/B), Epstien-Barr nuclear antigens and microRNAs that coordinate oncogenic signaling cascades such as NF-κB, PI3K/Akt, and JAK/STAT pathways (Yuan et al., 2025; Bauer et al., 2021). EBV-encoded miRNAs additionally regulate immunological checkpoints by targeting host genes involved in antigen processing and T cell activation, reducing cytotoxic immune responses (Li et al., 2020; Sausen et al., 2023). These combined effects produce an immunosuppressive TME enriched with regulatory T cells M2 macrophages, and myeloid-derived suppressor cells allowing recurrent viral persistence and tumor survival.

EBV influences host chromatin structure to promote oncogenic gene expression while silencing immune-related sites. EBV latent proteins such as EBNA1 and LMP1 engage host DNA methyltransferases (DNMT1, DNMT3A/B) and histone-modifying enzymes, resulting in the hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes like CDKN2A and PTEN (Di Pietro, 2020; Looi et al., 2023). Recent multi-omics analyses shows that EBV-infected B-cells develop a global reorganization of chromatin topologically associated domains (TADs). It then triggers oncogenic transcription factors such as MYC and RASAL3 while silencing antiviral genes via repressive H3K27me3 marks (Xiao et al., 2025).

3.2.2. Human Papillomavirus (HPV)

High-risk strains of HPV, such as HPV16 and HPV18, are significantly associated with cervical cancer. These strains are known to integrate into the host genome, leading to the production of oncoproteins (E6 and E7) that interfere with tumor-suppressor pathways like p53 and Rb. E6 binds to and promotes the degradation of the tumor suppressor p53 via E6AP ubiquitin-ligase pathway hence it disables apoptosis and DNA damage in infected host and epithelial cells (Lechien et al., 2020).. However, E7 associates with the retinoblastoma protein pRB family releasing E2F transcription factors and promoting uncontrolled S-phase entry and cell proliferation (Lechien et al., 2020).

In addition to the classical intrinsic effects of cells, recent studies emphasize how E6/E7 influence the tumor microenvironment. The study shows that E7 facilitates the production of epigenetic modifiers (DNMT1) and the modification of non-coding RNA which impacts adjacent stromal and immune cells (Westrich et al., 2017). Furthermore, a study published that HPV-induced oncogenesis encompasses more the E6 and E7 oncoproteins which are pivotal but additionally states that viral and host variables also influences the TME (Iuliano et al., 2018).

The oncoproteins E6/E7 expression in epithelial tumor cells results in modified cytokine and chemokine profiles. This includes as the upregulation of IL-6 and IL-8, which recruit and polarise immune and stromal cells in ways that promote tumour progression, exemplified by the M2 macrophage-like phenotype and regulatory T cells. The viral proteins disrupt antigen presentation mechanisms, such as the downregulation of MHC I and TAP1, potentially diminishing cytotoxic T cell infiltration and activation (Prins et al., 2025). The immune modulatory effect contributes to the establishment of a "cold" tumour microenvironment or an immune privileged niche for the infected tumour cells. The E6/E7 proteins are crucial in promoting the proliferation of infected epithelial cells while preventing apoptosis. Additionally, they affect the surrounding microenvironment, including stromal cells, vasculature, extracellular matrix, and immune infiltrate, thereby creating a niche conducive to tumour growth, immune evasion, and disease progression (Zhou et al., 2019)

3.3. Fungi

3.3.1. Candida albicans

Fungal infections while less studied, have also been implicated in cancer progression. For example, Candida albicans, commonly associated with infections in immunocompromised patients, has been found to promote tumorigenesis through its ability to activate inflammatory signaling and contribute to immune suppression. Fungal dysbiosis is increasingly acknowledged in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), with Malassezia spp. stimulating the complement C3–C5 axis to expedite oncogenesis (Sears, 2018) . Candida albicans in oral squamous cell cancer facilitates IL-1β-mediated epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) through the β-glucan receptor Dectin-1 (Dühring et al., 2015). Temperate phages activated by genotoxic chemotherapy release virulence genes from Pseudomonas aeruginosa, exacerbating inflammation in colorectal tumors (El Haddad et al., 2022). It is necessary to include internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequencing and virome-enriched metagenomics in typical omics processes to provide a full picture of the TME (Hannigan et al., 2018).

3.3.2. Fusobacterium nucleatum

Fusobacterium nucleatum has been detected in human breast cancers and facilitates tumour growth and metastasis in preclinical models (Parhi et al., 2020). The principal adhesin FadA serves as a crucial virulence factor; motif analyses (e.g., utilising JASPAR) can identify host-responsive regions in promoters, whereas ChIP-seq for ER-α is a recognised technique to confirm hormone-responsive binding in cancer models (Castro-Mondragon et al., 2022). Oestrogen status significantly influences the composition of host microbiota in both mice and humans, and hormone replacement therapy modifies microbial community structure; thus, variations in ovarian hormones are a credible mechanism impacting intratumoral bacterial colonisation (Kaliannan et al., 2018; Song & Kim, 2020).

Table 1.

Summary of Key Pathogens and Oncogenic Mechanisms.

Table 1.

Summary of Key Pathogens and Oncogenic Mechanisms.

| Pathogen |

Associated Cancer(s) |

Key Molecular Mechanisms |

Biomarkers |

Therapeutic Implications |

| Helicobacter pylori |

Gastric cancer |

CagA-mediated NF-κB activation

ROS-induced DNA damage

PD-L1 upregulation via Sonic Hedgehog

M2 macrophage polarization (miR-185-5p, let-7i-5p)

EMT induction via TGF-β/Smad2 |

CagA, PD-L1, HKDC1 |

Anti-PD-1 resistance; metabolic targeting with dichloroacetate |

| Fusobacterium nucleatum |

Colorectal cancer, Breast cancer |

FadA-E-cadherin binding → β-catenin activation

NF-κB, IL-6, IL-8 inflammatory cascade

CD8+ T-cell exclusion

Upregulation of ARG1+ myeloid cells

miRNA modulation via exosomes |

FadA, succinate, CD66b+ granulocytes |

Variable ICB response; antibiotic depletion studies ongoing |

| Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) |

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma, Gastric carcinoma, B-cell lymphomas |

LMP1/LMP2A → NF-κB, PI3K/Akt, JAK/STAT activation

EBNA1-mediated tumor suppressor hypermethylation (CDKN2A, PTEN)

miRNA-driven immune checkpoint modulation

Chromatin reorganization (TAD disruption)

MYC oncogene activation |

LMP1, EBNA1, EBV-miRNAs, H3K27me3 marks |

EBV-specific CTL therapy; DNMT inhibitors |

|

Human Papillomavirus (HPV16/18)

|

Cervical cancer, Head & neck SCC |

E6 → p53 degradation via E6AP ubiquitination

E7 → pRb inactivation, S-phase entry

MHC-I and TAP1 downregulation

IL-6/IL-8 secretion → M2 polarization

DNMT1 upregulation |

E6/E7 mRNA, p16INK4a, HPV DNA integration sites |

Therapeutic vaccines (E6/E7); ICB combination therapy |

| Candida albicans |

Oral SCC, Pancreatic cancer |

β-glucan → Dectin-1 → IL-1β secretion

EMT induction

Complement activation (C3-C5 axis) |

Dectin-1, IL-1β, C3/C5 |

Antifungal agents; complement inhibitors under investigation |

| Malassezia spp. |

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) |

Complement C3-C5 axis activation

Pro-inflammatory microenvironment |

C3a, C5a |

Antifungal therapy; complement blockade |

This table summarizes the major pathogenic microorganisms implicated in cancer development, their primary molecular mechanisms of oncogenesis, validated or emerging biomarkers, and current therapeutic strategies or resistance patterns. Abbreviations: CagA, cytotoxin-associated gene A; ROS, reactive oxygen species; EMT, epithelial-mesenchymal transition; ICB, immune checkpoint blockade; CTL, cytotoxic T lymphocyte; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

4. Modulating the Microbiome

4.1. Probiotics and Postbiotics

Akkermanisa municiphila and Bifidobacterium influences tumor-host immune environment by modulating the gut microbiome using beneficial microbes (probiotics) pr their metabolic product (postbiotics). For instance, Akkermansia municiphilais the next generation for probiotics that are used on tumor therapy and it is focus of recent studies. this is observed in recent studies sign as A. municiphila is in the gut is associated with better responses to immune checkpoints in lung cancer and other solid tumors (Derosa et al., 2022). This is because the A. municiphila enhances mucosal barrier by producing short fatty acids and other metabolites. It then enhances T-cell and antigen-presenting cell activation using the TLR2 and TRLR4 pathway which influences systemic and anti-tumor defense. Meanwhile, Bifidobacterium species are explored due to their capacity to nodulate dendritic cells activation, enhance cytotoxic T-cell response and reduce immunosuppressive myeloid populations in the tumor microenvironment (TME). This enhances the ability of probiotic and postbiotics then shifts the balance from an immunoppressive tumor microenvironment to a more immunologically active. increases beneficial microbial signaling (Lu et al., 2022)

4.2. Fecal Microbiota Transplant (FMT)

Fecal microbiota transplant is an innovative approach to modulate systemic immunity and tumor responses and it involves the transfer of microbial community from a healthy donor to recipient with the goal of shifting the gut-microbiome. FMT from patients who responded to anti-PD-1 therapy into refractory renewed sensitivity to therapy and favorable changes in the tumor microenvironment (Davar et al., 2021). Additionally, FMT increases beneficial A. municiplhila and Bifidobacterium and reduces immunosuppressive taxa, increases CD8+ T-cell infiltration into tumors, improve antigen-presenting cells while decreasing myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) in the TME (Rahman et al., 2025). These observations were made in a 2021 study, which reported FMT- together with anti-PD-1 therapy altered gut composition and shifted the tumor microenvironment toward responsiveness (Davar et al., 2021).

4.3. Oncolytic Microorganisms

Oncolytic microorganism is both engineered bacteria and viruses used in cancer therapy to selectively target and alter the tumor microenvironment. These agents use tumors metabolic and immunological weaknesses to promote lytic destruction, increase systemic anticancer immunity, and improve the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Oncolytic microorganisms bridge the gap between infection biology and precision oncology by turning "cold" tumors with low immune infiltration into "hot," immunologically active areas.

Oncolytic viruses (OVs) including vaccinia, adenovirus, and herpes simplex virus have been extensively modified to proliferate only in tumor cells while sparing normal tissue. Infection causes direct oncolysis and the production of tumor-associated antigens, which activate pattern recognition receptors and type I interferon signaling pathways.

Clostridium novyi-NT, Salmonella typhimurium, and Listeria monocytogenes have been genetically altered to increase safety and tumor selectivity. These bacteria thrive in anaerobic tumor niches, generating toxins and pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) that activate TLR signaling and cause antitumor inflammation (Akbariqomi et al., 2025; Jiang et al., 2022). Salmonella strains expressing tumor antigens or immuno-stimulatory cytokines (IL-2, TNF-α) show increased T cell activation and response to immune checkpoint inhibitors and adoptive T cell transfer therapy (Ma et al., 2021). Recent breakthroughs have also used synthetic biology and nanotechnology to improve microbial delivery and lower systemic toxicity. Encapsulation of bacterial spores or viral particles in nanocarriers improves tumor tropism, whilst genome editing allows for controlled lysis and immunological regulation. Hybrid oncolytic systems turn the TME into a "in situ vaccine," creating long-term immune memory against tumor antigens (Sivanandam et al., 2019; Wei et al., 2025).

4.4. Nanomedicine-Assisted Microbial Delivery

The microbiome is very important in the advancement of cancer, and dysbiosis caused by pathogens is a factor in tumor growth. Recent research has shown that changing the microbiota can lead to better treatment results. For instance, probiotics and fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) have demonstrated potential in re-establishing equilibrium within the microbiome, possibly augmenting cancer therapies such as immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI). Probiotics, including Akkermansia muciniphila, have been shown to modify the immune response and enhance the efficacy of PD-1 inhibitors by promoting T-cell infiltration in tumors (Gao et al., 2021). FMT has been employed to augment the efficacy of immunotherapy in preclinical models by modifying the gut microbiota and boosting anti-tumor immune activation (Sivan et al., 2015). Clinical FMT trials in melanoma patients resistant to immunotherapy further substantiate these results (Baruch et al., 2021).

The usage of oncolytic microorganisms to target tumors signify a growing area of research in cancer treatment. Attenuated Clostridium novyi-NT has shown significant antitumor efficacy in preclinical studies. Staedtke et al., 2015 demonstrated that the intra-tumoral administration of C. novyi-NT resulted in significant regression of orthotopically implanted glioblastomas in rats facilitated by bacterial germination in hypoxic tumor cores and ensuing immune activation. This discovery created the basis for employing anaerobic bacteria as viable oncolytic agents.

Subsequent investigations have elucidated this concept via the genetic modification of bacteria, including Salmonella typhimurium and Clostridium species, to augment tumor specificity and facilitate the delivery of therapeutic agents, such as immune-stimulatory cytokines and prodrug-converting enzymes (Staedtke et al., 2015). These microorganisms can alter the tumor microenvironment (TME), attract immune effector cells, and enhance anticancer immune responses when used in conjunction with immune checkpoint inhibition. Recent advancements in nanomedicine have significantly improved bacterial delivery strategies. The encapsulation of modified bacterial spores or their metabolites in nanoparticle carriers has enhanced tumor targeting and reduced systemic toxicity

5. Molecular Approaches to Studying Host-Pathogen Interactions

The integration of high-throughput omics tools like genomes, transcriptomics, and proteomics has revolutionized the understanding of the molecular interaction between cancer and pathogens. These tools enable extensive characterization of the genome, transcriptome, and proteome in cancerous tissues, offering unprecedented insights into how microbial infections drive oncogenic transformation, immune modulation and disease progression. Through large scale data gathering and computational integration, omics methods have provided understanding on pathogen-derived genetic and molecular signals that affects the behavior of cancer cells in the TME (Velázquez-Márquez & Huelgas-Saavedra, 2024).

Genomics and metagenomics have provided detailed maps of microbial communities residing in tumor niches. Whole genome and metagenomic profiling allow researchers to identify microbial taxa that correlate with tumor type, stage and immune activity. For instance, metagenomic studies have demonstrated that specific bacterial populations such Fusobacterium nucleatum in the colorectal cancer TME are linked to immune infiltration and unfavorable clinical outcomes (Zou et al., 2024). Similarly, integrated multi-omics has shown shifts in gut microbiota composition correspond with host transcriptomic and metabolic reprogramming in colon cancer patients (Qin et al., 2025)

Transcriptomics, primary through RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), allows for the detailed analysis of host-pathogen gene regulation cancer tissues. In CRC, infection by F. nucleatum modifies host profiles by activating inflammatory mediators such as, NF-κB, IL-6, and IL-8, and inhibits cytotoxic immune pathways favoring tumorigenesis and metastasis (Ye et al., 2024). Furthermore, multi-omics integration into transcriptomic and microbial data has revealed how dysbiosis reshapes immune-related transcriptional networks that promotes inflammatory environment for tumor growth (Qiao et al., 2022). RNA-seq analyses uncovers pathogen-induced changes in gene expression and also maps immune-suppressive and angiogenic pathways that mediate cancer progression.

Proteomics enhances the understanding of the functional effects of pathogen-host interactions at the protein level. Using advance mass spectrometry platforms, studies have uncovered distinct proteomic alterations in the cancers associated with microbial infection. For example, Helicobacter pylori infection in gastric cancer modulates hosts proteins involved in DNA repair, apoptosis and cellular metabolism. This indicates that induced post-translational modifications may drive tumorigenic processes (Shang et al., 2023). These proteomic signatures can provide potential biomarkers for pathogen-related cancers and can inform the development of therapeutic strategies.

6. Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence in Predicting Host-Pathogen Interactions

Machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) are transforming tools for analyzing complex datasets and predicting host-pathogen interactions in cancer. These computational approaches can process large amounts of multi-omics data, including genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics, to identify hidden patterns that relate pathogen presence to cancer progression. Utilizing algorithms like support vector machines (SVM), random forests, and deep learning, ML models are capable of predicting cancer outcomes by analyzing pathogen-induced alterations in the tumor microenvironment (TME) (Teixeira et al., 2024). Such predictive models have been successfully deployed to differentiate cancer based on microbiome composition and achieve in early detection scenarios and correlate microbial features in immune response (Azhdarimoghaddam et al., 2025).

Additionally, gut microbiome data sets for colorectal cancer and adenoma screening have been analyzed using ML models. This shows how microbiome-based risk scores can provide non-invasive cancer detection with greater accuracy using random forest classifiers (Tsai et al., 2025). Furthermore, integrated insights from multi-omic data layers, from microbial metagenomes to host transcriptomes, are starting to be extracted by AI-driven systems. These insights show how particular microbial taxa are linked to host gene regulatory programs that affect tumorigenicity and immunotherapy response.

7. Potential Clinical Applications and Challenges in Translating Findings

The clinical application of host-pathogen interaction research is still in its early stages, and there are several challenges to overcome before these findings can be translated into routine clinical practice. One of the major hurdles is the generalizability of findings across diverse patient populations. Pathogen-driven cancers are heterogeneous, and the variability in microbial composition across geographies and patient demographics complicates the development of universally applicable biomarkers. For example, pathogen-induced immune responses vary based on the genetic background of the host, which can influence cancer susceptibility and therapeutic responses.

Additionally, while multi-omics models have shown promise in predicting cancer progression and treatment responses, external validation across large and diverse cohorts remains limited. Many studies rely on single-cohort data, which may not accurately reflect the variability in microbial communities and immune responses in broader populations. To improve the clinical relevance of pathogen-targeted therapies, more rigorous cross-cohort validation, as well as long-term prospective studies, are necessary.

Moreover, the integration of pathogen profiles into clinical workflows requires the development of standardized, cost-effective diagnostic tools. The use of multi-omics data in clinical settings demands the availability of high-throughput technologies and robust bioinformatics pipelines that can accurately process and analyze large volumes of data. Overcoming these technical and logistical challenges will be key to translating host-pathogen interaction research into actionable clinical interventions.

Host-pathogen interactions are increasingly recognized as critical factors in cancer progression. Pathogens contribute to tumorigenesis by inducing inflammation, modulating immune responses, and causing genetic instability. Pathogen-driven inflammation in the tumor microenvironment promotes tumor growth and metastasis, while immune evasion strategies employed by pathogens allow tumors to escape immune surveillance and resist treatment. The growing recognition of pathogen-induced immune modulation has opened new avenues for cancer research, particularly in the development of pathogen-targeted therapies. Understanding the molecular pathways through which pathogens influence cancer progression provides an opportunity to develop novel therapeutic strategies, including the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors and other immunotherapies that target pathogen-driven immune suppression.

Experimental validation is crucial for translating computational predictions into clinical applications. Recent studies have employed advanced techniques such as cryo-electron tomography to observe host-pathogen interactions in near-native states, providing insights into the structural basis of these interactions. Additionally, high-throughput technologies, including 3D cell cultures and organ-on-a-chip models, have been utilized to study host-pathogen interactions in a more physiologically relevant context. These models allow for the simulation of complex tissue environments, facilitating the assessment of therapeutic interventions.

The future of cancer therapy lies in integrating multi-omics data to identify pathogen-specific biomarkers and therapeutic targets. Pathogen-driven alterations in the tumor microenvironment offer new opportunities for precision medicine, where treatments can be tailored to the individual patient's pathogen profile and immune response.

The application of machine learning models to integrate multi-omics data will play a crucial role in identifying personalized treatment strategies for pathogen-associated cancers. By focusing on the dynamic interactions between pathogens and the host immune system, future research can uncover new insights into cancer resistance mechanisms and pave the way for more effective treatments. Despite the challenges in translating these findings into clinical practice, the potential for personalized cancer therapies based on pathogen-host interactions remains promising. With further validation and technological advancements, pathogen-targeted therapies could significantly improve patient outcomes and provide new hope for individuals with pathogen-related cancers.

This review has shown the importance of host-pathogen interactions in tumor-microenvironment and cancer progression. The review highlights the different processes through which different infections contribute to cancer through chronic inflammation, immunological regulation, genomic instability and metabolic reprogramming. The review has emphasized that pathogen influence only infections, but the creation of intricate mechanisms for the survival, proliferation and metastasis of cancer cells. The integration of multi-omics, artificial intelligence and machine learning models have improved the understanding of pathogen-driven tumor. These technologies have improved the identification of specific biomarkers and therapeutic targets in pathogen-infected tumors. Notably among them is the use of spatial omics in organizing distinct effects of pathogens within the tumor microenvironment. The use of probiotics, fecal microbiota transplantation, nanomedicine, and oncolytic bacteria are recent innovative methods that targets the TME and have shown a promise of improving immunotherapy response despite its challenges in clinical implementation. Most of the challenges are due to the variety of pathogen-associated malignancies, the need for external validation of predictive models and the creation of standardized diagnostic tools.

Author Contributions

Philip Boakye Bonsu (boakyebonsu2@gmail.com), Conceptualization, writing – original draft, Writing, Project administration. Kwadwo: Fosu (kwafos.kf@gmail.com) Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. Samuel Badu Nyarko: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Supervision.

Funding

No external funding was obtained for this project.

References

- Anuja, K.; Roy, S.; Ghosh, C.; et al. Prolonged inflammatory microenvironment is crucial for pro-neoplastic growth and genome instability: a detailed review. Inflamm. Res. 2017, 66, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Huang, Y.; Li, H.; et al. Helicobacter pylori promotes gastric cancer progression through the tumor microenvironment. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2022, 106, 4375–4385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Q., Liu, Q., Lau, R. I., Zhang, J., Xu, Z., Yeoh, Y. K., Leung, T. W. H., Tang, W., Zhang, L., Liang, J. Q. Y., Yau, Y. K., Zheng, J., Liu, C., Zhang, M., Cheung, C. P., & Ng, S. C. (2022). Faecal microbiome-based machine learning for multi-class disease diagnosis. September, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Kidane, D. Molecular Mechanisms of H. pylori -Induced DNA Double-Strand Breaks. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliannan, K., Robertson, R. C., Murphy, K., Stanton, C., Kang, C., Wang, B., Hao, L., Bhan, A. K., & Kang, J. X. (2018). Estrogen-mediated gut microbiome alterations influence sexual dimorphism in metabolic syndrome in mice. 1–22.

- Song, C. H.; Kim, N. 17 β - Estradiol supplementation changes gut microbiota diversity in intact and colorectal cancer - induced ICR male mice. Scientific Reports 2020, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, E.; Kim, S.; Kim, S. G. Emerging role of Helicobacter pylori in the immune evasion mechanism of gastric cancer: An insight into tumor microenvironment–pathogen interaction. Frontiers in Oncology 2022, 12, 862462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staedtke, V.; Bai, R.; Sun, W.; Huang, J.; Kazuko, Kibler K.; Tyler, B. M.; Gallia, G. L.; Kinzler, K.; Vogelstein, B.; Zhou, S.; Riggins, G. J. Clostridium novyi-NT can cause regression of orthotopically implanted glioblastomas in rats. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 5536–5546. Retrieved from https://www.oncotarget.com/article/3627/.

- Velázquez-Márquez, N.; Huelgas-Saavedra, L.C. Introduction: The Role of Pathogens Associated with Human Cancer and the Concept of Omics–An Overview. In Pathogens Associated with the Development of Cancer in Humans; Velázquez-Márquez, N., Paredes-Juárez, G.A., Vallejo-Ruiz, V., Eds.; Springer: Cham, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iuliano, M.; Mangino, G.; Chiantore, M. V.; Zangrillo, M. S.; Accardi, R.; Tommasino, M.; Fiorucci, G.; Romeo, G. Human Papillomavirus E6 and E7 oncoproteins affect the cell microenvironment by classical secretion and extracellular vesicles delivery of inflammatory mediators. Cytokine 2018, 106, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anuja, K.; Roy, S.; Ghosh, C.; Gupta, P.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Banerjee, B. Prolonged inflammatory microenvironment is crucial for pro-neoplastic growth and genome instability: A detailed review. Inflammation Research 2017, 66(2), 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arner, E. N.; Rathmell, J. C. Metabolic programming and immune suppression in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Cell 2023, 41(3), 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhdarimoghaddam, A.; Mohammad Bigloo, A.; Soleimani Meigoli, M. S.; Abdelbaset, M.; Narimani, M.; Dadkhah Tehrani, F.; Asadi Anar, M.; Abdolvand, F.; Goudarzi, P.; Ghazizadeh, Y.; Mohammadzadeh, N.; Eini, P.; Khosravi, F.; Abouzeid, M. Artificial intelligence at the gut–oral microbiota frontier: Mapping machine learning tools for gastric cancer risk prediction. BioMedical Engineering OnLine 2025, 24(1), 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruch, E. N.; Youngster, I.; Ben-Betzalel, G.; Ortenberg, R.; Lahat, A.; Katz, L.; Adler, K.; Dick-Necula, D.; Raskin, S.; Bloch, N.; Rotin, D.; Anafi, L.; Avivi, C.; Melnichenko, J.; Steinberg-Silman, Y.; Mamtani, R.; Harati, H.; Asher, N.; Shapira-Frommer, R.; …; Boursi, B. Fecal microbiota transplant promotes response in immunotherapy-refractory melanoma patients. Science 2021, 371(6529), 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhanu, P.; Godwin, A. K.; Umar, S.; Mahoney, D. E. Bacterial Extracellular Vesicles in Oncology: Molecular Mechanisms and Future Clinical Applications. Cancers 2025, 17(11), 1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro-Mondragon, J. A.; Riudavets-Puig, R.; Rauluseviciute, I.; Berhanu Lemma, R.; Turchi, L.; Blanc-Mathieu, R.; Lucas, J.; Boddie, P.; Khan, A.; Manosalva Pérez, N.; Fornes, O.; Leung, T. Y.; Aguirre, A.; Hammal, F.; Schmelter, D.; Baranasic, D.; Ballester, B.; Sandelin, A.; Lenhard, B.; …; Mathelier, A. JASPAR 2022: The 9th release of the open-access database of transcription factor binding profiles. Nucleic Acids Research 2022, 50(D1), D165–D173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, T.-H.; Ho, P.-C. Interferon-driven Metabolic Reprogramming and Tumor Microenvironment Remodeling. Immune Network 2025, 25(1), e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Yao, C.; Tian, N.; Zhang, C.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Zeng, T.; Song, Y. The interplay between persistent pathogen infections with tumor microenvironment and immunotherapy in cancer. Cancer Medicine 2024, 13(17), e70154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuellar-Gómez, H.; Ocharán-Hernández, M. E.; Calzada-Mendoza, C. C.; Comoto-Santacruz, D. A. Association of Fusobacterium nucleatum infection and colorectal cancer: A Mexican study. Revista de Gastroenterología de México (English Edition) 2022, 87(3), 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davar, D.; Dzutsev, A. K.; McCulloch, J. A.; Rodrigues, R. R.; Chauvin, J.-M.; Morrison, R. M.; Deblasio, R. N.; Menna, C.; Ding, Q.; Pagliano, O.; Zidi, B.; Zhang, S.; Badger, J. H.; Vetizou, M.; Cole, A. M.; Fernandes, M. R.; Prescott, S.; Costa, R. G. F.; Balaji, A. K.; Zarour, H. M. Fecal microbiota transplant overcomes resistance to anti–PD-1 therapy in melanoma patients. Science 2021, 371(6529), 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derosa, L.; Routy, B.; Thomas, A. M.; Iebba, V.; Zalcman, G.; Friard, S.; Mazieres, J.; Audigier-Valette, C.; Moro-Sibilot, D.; Goldwasser, F.; Silva, C. A. C.; Terrisse, S.; Bonvalet, M.; Scherpereel, A.; Pegliasco, H.; Richard, C.; Ghiringhelli, F.; Elkrief, A.; Desilets, A.; …; Besse, B. Intestinal Akkermansia muciniphila predicts clinical response to PD-1 blockade in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Nature Medicine 2022, 28(2), 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pietro, A. Epstein–Barr Virus Promotes B Cell Lymphomas by Manipulating the Host Epigenetic Machinery. Cancers 2020, 12(10), 3037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; Xu, B.; Luo, P.; Chen, T.; Zou, J. Microbial metabolites and their influence on the tumor microenvironment. Frontiers in Immunology 2025, 16, 1675677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Xu, Y.; Dou, Y.; Xu, D. Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer: Mechanisms and new perspectives. Journal of Hematology & Oncology 2025, 18(1), 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dühring, S.; Germerodt, S.; Skerka, C.; Zipfel, P. F.; Dandekar, T.; Schuster, S. Host-pathogen interactions between the human innate immune system and Candida albicans—Understanding and modeling defense and evasion strategies. Frontiers in Microbiology 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Haddad, L.; Mendoza, J. F.; Jobin, C. Bacteriophage-mediated manipulations of microbiota in gastrointestinal diseases. Frontiers in Microbiology 2022, 13, 1055427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galasso, L.; Termite, F.; Mignini, I.; Esposto, G.; Borriello, R.; Vitale, F.; Nicoletti, A.; Paratore, M.; Ainora, M. E.; Gasbarrini, A.; Zocco, M. A. Unraveling the Role of Fusobacterium nucleatum in Colorectal Cancer: Molecular Mechanisms and Pathogenic Insights. Cancers 2025, 17(3), 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grivennikov, S. I.; Greten, F. R.; Karin, M. Immunity, Inflammation, and Cancer. Cell 2010, 140(6), 883–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R. A. Hallmarks of Cancer: The Next Generation. Cell 2011, 144(5), 646–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannigan, G. D.; Duhaime, M. B.; Ruffin, M. T.; Koumpouras, C. C.; Schloss, P. D. Diagnostic Potential and Interactive Dynamics of the Colorectal Cancer Virome. mBio 2018, 9(6), e02248-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laha, D.; Grant, R.; Mishra, P.; Nilubol, N. The Role of Tumor Necrosis Factor in Manipulating the Immunological Response of Tumor Microenvironment. Frontiers in Immunology 2021, 12, 656908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, Md. A.; Noman, Md. A.; Ahmmed, R.; Hossain, Md. S.; Ahmed, Md. F.; Pappu, Md. A. A.; Islam, Md. S.; Noor, T.; Kabir, Md. H.; Mollah, Md. N. H. In-silico identification of host-key-genes associated with dengue-virus-infections highlighting their pathogenetic mechanisms and therapeutic agents. PLOS One 2025, 20(10), e0333509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lechien, J. R.; Descamps, G.; Seminerio, I.; Furgiuele, S.; Dequanter, D.; Mouawad, F.; Badoual, C.; Journe, F.; Saussez, S. HPV Involvement in the Tumor Microenvironment and Immune Treatment in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinomas. Cancers 2020, 12(5), 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Luo, W.; Xiao, L.; Xu, X.; Peng, X.; Cheng, L.; Zhou, X.; Zheng, X. Microbial manipulators: Fusobacterium nucleatum modulates the tumor immune microenvironment in colorectal cancer. Journal of Oral Microbiology 2025, 17(1), 2544169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; He, C.; Wu, J.; Yang, D.; Yi, W. Epstein barr virus encodes miRNAs to assist host immune escape. Journal of Cancer 2020, 11(8), 2091–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, A.; Korani, L.; Yeung, C. L. S.; Tey, S. K.; Yam, J. W. P. The emerging role of bacterial extracellular vesicles in human cancers. Journal of Extracellular Vesicles 2024, 13(10), e12521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Li, C.; Lu, Y.; Liu, C.; Yang, W. Tumor microenvironment-mediated immune tolerance in development and treatment of gastric cancer. Frontiers in Immunology 2022, 13, 1016817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Yuan, X.; Wang, M.; He, Z.; Li, H.; Wang, J.; Li, Q. Gut microbiota influence immunotherapy responses: Mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Journal of Hematology & Oncology 2022, 15(1), 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Huang, L.; Hu, D.; Zeng, S.; Han, Y.; Shen, H. The role of the tumor microbe microenvironment in the tumor immune microenvironment: Bystander, activator, or inhibitor? Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research 2021, 40(1), 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata-Kamiya, N.; Hatakeyama, M. Helicobacter pylori -induced DNA double-stranded break in the development of gastric cancer. Cancer Science 2022, 113(6), 1909–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nejman, D.; Livyatan, I.; Fuks, G.; Gavert, N.; Zwang, Y.; Geller, L. T.; Rotter-Maskowitz, A.; Weiser, R.; Mallel, G.; Gigi, E.; Meltser, A.; Douglas, G. M.; Kamer, I.; Gopalakrishnan, V.; Dadosh, T.; Levin-Zaidman, S.; Avnet, S.; Atlan, T.; Cooper, Z. A.; …; Straussman, R. The human tumor microbiome is composed of tumor type–specific intracellular bacteria. Science 2020, 368(6494), 973–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parhi, L.; Alon-Maimon, T.; Sol, A.; Nejman, D.; Shhadeh, A.; Fainsod-Levi, T.; Yajuk, O.; Isaacson, B.; Abed, J.; Maalouf, N.; Nissan, A.; Sandbank, J.; Yehuda-Shnaidman, E.; Ponath, F.; Vogel, J.; Mandelboim, O.; Granot, Z.; Straussman, R.; Bachrach, G. Breast cancer colonization by Fusobacterium nucleatum accelerates tumor growth and metastatic progression. Nature Communications 2020, 11(1), 3259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, V. L.; Marra, M. A. The Drivers, Mechanisms, and Consequences of Genome Instability in HPV-Driven Cancers. Cancers 2022, 14(19), 4623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prins, R.; Fernandez, D. J.; Akbari, O.; Da Silva, D. M.; Kast, W. M. HPV16 E6 and E7 expressing cancer cells suppress the antitumor immune response by upregulating KLF2-mediated IL-23 expression in macrophages. Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer 2025, 13(8), e011915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, H.; Li, H.; Wen, X.; Tan, X.; Yang, C.; Liu, N. Multi-Omics Integration Reveals the Crucial Role of Fusobacterium in the Inflammatory Immune Microenvironment in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Microbiology Spectrum 2022, 10(4), e01068-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Wang, Q.; Lin, Q.; Liu, F.; Pan, X.; Wei, C.; Chen, J.; Huang, T.; Fang, M.; Yang, W.; Pan, L. Multi-omics analysis reveals associations between gut microbiota and host transcriptome in colon cancer patients. mSystems 2025, 10(3), e00805-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Kabir, M. H.; Mohammad, A.; Hettiarachchige; Katurusinghe, Iresha; Ogunbote, O.; Pinnock, N.; Namani, S.; Namani, S. Enhancing Immune Response in Immunotherapy-Resistant Melanoma Through Fecal Microbiota Transplantation: A Systematic Review. Biomedical & Pharmacology Journal 2025, 4(18), 2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rembiałkowska, N.; Kocik, Z.; Kłosińska, A.; Kübler, M.; Pałkiewicz, A.; Rozmus, W.; Sędzik, M.; Wojciechowska, H.; Gajewska-Naryniecka, A. Inflammation-Driven Genomic Instability: A Pathway to Cancer Development and Therapy Resistance. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18(9), 1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routy, B.; Le Chatelier, E.; Derosa, L.; Duong, C. P. M.; Alou, M. T.; Daillère, R.; Fluckiger, A.; Messaoudene, M.; Rauber, C.; Roberti, M. P.; Fidelle, M.; Flament, C.; Poirier-Colame, V.; Opolon, P.; Klein, C.; Iribarren, K.; Mondragón, L.; Jacquelot, N.; Qu, B.; Zitvogel, L. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1–based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science 2018, 359(6371), 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubinstein, M. R.; Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Hao, Y.; Cai, G.; Han, Y. W. Fusobacterium nucleatum Promotes Colorectal Carcinogenesis by Modulating E-Cadherin/β-Catenin Signaling via its FadA Adhesin. Cell Host & Microbe 2013, 14(2), 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sausen, D. G.; Poirier, M. C.; Spiers, L. M.; Smith, E. N. Mechanisms of T cell evasion by Epstein-Barr virus and implications for tumor survival. Frontiers in Immunology 2023, 14, 1289313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwabe, R. F.; Jobin, C. The microbiome and cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer 2013, 13(11), 800–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sears, C. L. The who, where and how of fusobacteria and colon cancer. eLife 2018, 7, e28434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, F.; Cao, Y.; Wan, L.; Ren, Z.; Wang, X.; Huang, M.; Guo, Y. Comparison of Helicobacter pylori positive and negative gastric cancer via multi-omics analysis. mBio 2023, 14(6), e01531-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shigematsu, Y.; Saito, R.; Amori, G.; Kanda, H.; Takahashi, Y.; Takeuchi, K.; Takahashi, S.; Inamura, K. Fusobacterium nucleatum, immune responses, and metastatic organ diversity in colorectal cancer liver metastasis. Cancer Science 2024, 115(10), 3248–3255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivan, A.; Corrales, L.; Hubert, N.; Williams, J. B.; Aquino-Michaels, K.; Earley, Z. M.; Benyamin, F. W.; Man Lei, Y.; Jabri, B.; Alegre, M.-L.; Chang, E. B.; Gajewski, T. F. Commensal Bifidobacterium promotes antitumor immunity and facilitates anti–PD-L1 efficacy. Science 2015, 350(6264), 1084–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivanandam, V.; LaRocca, C. J.; Chen, N. G.; Fong, Y.; Warner, S. G. Oncolytic Viruses and Immune Checkpoint Inhibition: The Best of Both Worlds. Molecular Therapy - Oncolytics 2019, 13, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiert, B.; Weber, M. M. Nuclear warfare: Pathogen manipulation of the nuclear pore complex and nuclear functions. mBio 2025, 16(4), e01940-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, M.; Silva, F.; Ferreira, R. M.; Pereira, T.; Figueiredo, C.; Oliveira, H. P. A review of machine learning methods for cancer characterization from microbiome data. Npj Precision Oncology 2024, 8(1), 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y.-J.; Lyu, W.-N.; Liao, N.-S.; Chen, P.-C.; Tsai, M.-H.; Chuang, E. Y. Gut microbiome-based machine learning model for early colorectal cancer and adenoma screening. Gut Pathogens 2025, 17(1), 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, S.; Tsang, C. M.; To, K.; Lo, K. The role of Epstein–Barr virus in epithelial malignancies. The Journal of Pathology 2015, 235(2), 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Castellanos, E.; Rincón-Riveros, A. Microsatellite Instability in the Tumor Microenvironment: The Role of Inflammation and the Microbiome. Cancer Medicine 2025, 14(8), e70603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.-J.; Siu, M. K.; Jiang, Y.-X.; Leung, T. H.; Chan, D. W.; Cheng, R.-R.; Cheung, A. N.; Ngan, H. Y.; Chan, K. K. Aberrant upregulation of PDK1 in ovarian cancer cells impairs CD8+ T cell function and survival through elevation of PD-L1. OncoImmunology 2019, 8(11), 1659092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, X.-Y.; Feng, H.-J.; Zhu, Y.-Y.; Guo, S.-J.; Wang, H.; Li, M.; Mei, Q. The immune microenvironment of pathogen-associated cancers and current clinical therapeutics. Molecular Cancer 2025, 24(1), 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westrich, J. A.; Warren, C. J.; Pyeon, D. Evasion of host immune defenses by human papillomavirus. Virus Research 2017, 231, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Liu, Y.; Shu, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, C.; He, S.; Li, J.; Li, T.; Liu, T.; Liu, Y. Molecular mechanisms of viral oncogenesis in haematological malignancies: Perspectives from metabolic reprogramming, epigenetic regulation and immune microenvironment remodeling. Experimental Hematology & Oncology 2025a, 14(1), 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Liu, Y.; Shu, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, C.; He, S.; Li, J.; Li, T.; Liu, T.; Liu, Y. Molecular mechanisms of viral oncogenesis in haematological malignancies: Perspectives from metabolic reprogramming, epigenetic regulation and immune microenvironment remodeling. Experimental Hematology & Oncology 2025b, 14(1), 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Fan, L.; Lin, Y.; Shen, W.; Qi, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Wang, L.; Long, Y.; Hou, T.; Si, J.; Chen, S. Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes colorectal cancer metastasis through miR-1322/CCL20 axis and M2 polarization. Gut Microbes 2021, 13(1), 1980347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Liu, X.; Liu, Z.; Pan, C.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Z.; Sun, H. Fusobacterium nucleatum in tumors: From tumorigenesis to tumor metastasis and tumor resistance. Cancer Biology & Therapy 2024, 25(1), 2306676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.; Li, R.; Xu, Q.; Liang, C.; Gao, J.; Yuan, Z.; Zhao, R.; Liang, W.; Cao, B.; Zhao, X.; Wei, B.; Li, P. The regulatory and synergistic effects of FBP2 and HKDC1 on glucose metabolism and malignant progression in gastric cancer. Cell Death & Disease 2025, 16(1), 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Ning, J.; Fu, W.; Ding, S. Helicobacter pylori infection status and evolution of gastric cancer. Chinese Medical Journal 2025, 138(23), 3083–3096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Tuong, Z. K.; Frazer, I. H. Papillomavirus Immune Evasion Strategies Target the Infected Cell and the Local Immune System. Frontiers in Oncology 2019, 9, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Huang, Y.; Li, H.; Shao, S. Helicobacter pylori promotes gastric cancer progression through the tumor microenvironment. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2022, 106(12), 4375–4385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, S.; Yang, C.; Zhang, J.; Zhong, D.; Meng, M.; Zhang, L.; Chen, H.; Fang, L. Multi-omic profiling reveals associations between the gut microbiome, host genome and transcriptome in patients with colorectal cancer. Journal of Translational Medicine 2024, 22(1), 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).