Introduction

Public procurement in Nigeria represents one of the largest channels for state expenditure and economic empowerment, accounting for nearly 12% of the country’s GDP (Williams, 2024). Yet, despite two decades of procurement reform and institutional strengthening, women especially those in marginalized, disabled, or socially constrained circumstances remain systematically excluded from public contracting opportunities. Regional policy analyses have highlighted public procurement reform as a key lever for advancing gender equality and economic inclusion across African economies, particularly through targeted support for women-owned enterprises (African Development Bank [AfDB], 2024). Gender-Responsive Public Procurement (GRPP) was introduced to correct this imbalance by embedding gender equity considerations into procurement design, evaluation, and implementation processes (UN Women, 2022; ILO, 2022). In practice, Nigeria’s procurement ecosystem still favors visibility, extroversion, and networking capacity, qualities that many women constrained by personality, cultural, social, and physical barriers cannot easily display.

The term “Women in the Shadow” in this paper captures a multidimensional group of women who are unseen or unheard within public procurement systems not due to lack of skill or innovation, but due to structural, technological, and sociocultural constraints. These women include those living with physical disabilities; those constrained by patriarchal cultural norms that discourage public bidding or financial assertiveness; and those whose non-networking personalities limit their participation in male-dominated procurement circles. While their economic contributions are substantial in informal markets and small-scale enterprises, their participation in formal procurement is rare and often invisible (Affirmative Procurement in West Africa.org, 2024; Banyan Global, 2023).

This invisibility is reinforced by three intersecting barriers: procedural opacity, digital exclusion, and social-cultural marginalization. Procedurally, women encounter complex tender documentation and opaque vendor evaluation systems that demand insider knowledge or patronage (Williams, 2024). Digitally, the gender digital divide in Nigeria continues to hinder equitable access to procurement portals and data systems, especially for rural or disabled women who face compounded barriers of cost, literacy, and accessibility (Banyan Global, 2023; GSMA, 2023). Socio-culturally, procurement meetings, bidding events, and professional associations are often dominated by male contractors, creating invisible but powerful networks of exclusion.

Against this backdrop, Artificial Intelligence (AI) has emerged globally as both a transformative tool and a new frontier of inequality. In public procurement, AI technologies from predictive analytics to automated vendor evaluation and fraud detection are increasingly being adopted to enhance transparency, efficiency, and accountability (Andhov, 2025; OECD, 2025). In countries such as Kenya, India, and Brazil, AI-driven procurement dashboards have been used to map gender participation, flag collusion, and promote inclusive contracting opportunities (World Bank, 2019–2023; Open Contracting Partnership, 2022). In Nigeria, emerging pilot projects by the Bureau of Public Procurement (BPP) and Accountability Lab Nigeria have started exploring AI-integrated platforms for simplifying procurement data in states like Edo, Ekiti, and Plateau (Accountability Lab Nigeria, 2023, 2024).

This study therefore explores the strategic integration of AI within Gender-Responsive Public Procurement (GRPP) reforms in Nigeria, focusing on how AI can illuminate and empower Women in the Shadow. It argues that the fusion of AI and GRPP if guided by inclusive ethics, local data governance, and participatory design can disrupt traditional procurement hierarchies and create equitable pathways for women who have long remained unseen.

Conceptual Framework

Intersectionality Theory (Crenshaw, 1989)

Rooted in Crenshaw’s work, intersectionality emphasizes that social categories (gender, disability, ethnicity, class, personality/introversion) interact to produce specific forms of disadvantage that are not captured by single-axis analyses (Crenshaw, 1989). For the paper, intersectionality directs attention away from “women” as a homogeneous category and toward shadowed women whose exclusion emerges from overlapping axes (e.g., a rural, introverted woman with a mobility impairment faces different obstacles than an urban woman entrepreneur).

Feminist Technology Studies (FTS)

FTS interrogates how technologies embed and reproduce social power relations unless they are intentionally designed otherwise. It reframes technologies not as neutral tools but as sociotechnical artefacts shaped by social norms, design choices, and institutional contexts (Nagitta et al., 2022). This lens underscores that AI systems in procurement will only promote equity if design processes are participatory, contextual, and attentive to gendered power.

Socio-Technical Systems Theory

This theory treats technology and social systems as co-constitutive. Technology changes social practices and social practices shape how technology is used. In procurement, institutional rules, evaluator behavior, legal frameworks, and community norms interact with digital platforms and algorithms to produce outcomes (Warschauer-style thinking). A socio-technical approach foregrounds intervention points across people, policy, and technology rather than focusing on any single element.

How Intersectional Invisibility Operates in Nigeria’s Procurement System

Intersectional invisibility in Nigeria’s procurement ecosystem stems from data, process, and structural gaps that reinforce one another. First, data invisibility arises because procurement databases seldom record critical attributes such as rural location, disability, caregiving roles, or digital literacy levels. This omission prevents algorithms from recognizing marginalized women, resulting in biased outputs and underrepresentation. Second, process invisibility occurs within tendering and evaluation systems that reward social visibility participation in pre-bid meetings, networking, and personal rapport with officers thereby sidelining introverted women, those with disabilities, and those from conservative cultures. Finally, structural invisibility is sustained through institutional requirements like digital submissions, formal guarantees, and English-only documentation that lack inclusive supports such as low-bandwidth platforms or local language access. Together, these layers form a self-reinforcing cycle: what is unseen in data remains unseen in algorithms, limiting invitations, participation, and eventual empowerment.

AI’s Dual Nature: Inclusion vs. Exclusion

AI offers two contrasting pathways depending on design, data, and governance. When trained on representative, intersectional datasets and co-designed with target users, AI can surface underrepresentation by generating gender- and disability-disaggregated dashboards; provide low-bandwidth voice or text assistants to guide less-literate users through bidding; and detect anomalous evaluator behavior to trigger human review (Nagitta et al., 2022; Andhov, 2025). In these modes AI functions as an amplifier of visibility and an operational tool for GRPP.

Conversely, if AI uses biased training data, opaque scoring rules, or networked proxies (e.g., referrals, prior contract history) it will reproduce existing inequalities. Research on algorithmic fairness shows that models trained on unequal data produce unequal outputs (Buolamwini & Gebru, 2018). In Nigeria, where disaggregated signals for shadowed groups are weak, poorly governed AI can institutionalize the “shadow” rather than illuminate it.

Methodological Approach

This paper adopts a policy-analytic and conceptual synthesis approach, drawing on multiple strands of evidence to examine how artificial intelligence (AI) can be leveraged to promote gender-responsive and inclusive procurement systems in Nigeria. The analysis is grounded in the understanding that digital transformation in public procurement must not only optimize efficiency but also enhance equity, access, and representation for historically shadowed groups of women. The study begins with a desk review of AI inclusion models implemented in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), focusing particularly on contexts with emerging digital procurement ecosystems. Kenya’s AI-assisted procurement audit mechanisms and India’s Government e-Marketplace (GeM) for women-owned micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) are examined to identify replicable strategies that merge automation with equity outcomes. These models provide comparative insights into how algorithmic systems can either amplify or mitigate gender disparities within government contracting frameworks. Complementing this review is an analysis of secondary data on Nigeria’s procurement gender participation, drawing from publicly available sources such as the Bureau of Public Procurement (BPP) datasets, Women in Management, Business and Public Service (WIMBIZ) reports, and the Open Contracting Data Standard (OCDS) Nigeria platform. These sources offer partial yet critical visibility into participation trends and inclusion gaps in federal and state-level contracting. The data are interpreted through the lens of intersectional invisibility acknowledging how women facing multiple, overlapping forms of marginalization (including rurality, caregiving roles, or neurodivergence) remain underrepresented or entirely absent in official registries. A comparative policy alignment was also conducted to assess how Nigeria’s digital procurement reforms intersect with national frameworks, particularly the National Digital Economy Policy and Strategy (2020–2030) and the Public Procurement Act (2007). This comparison highlights both the enabling provisions and the structural blind spots that determine the readiness of Nigeria’s procurement system to integrate AI tools ethically and inclusively. Analytically, the paper employs a human-centered lens, asking how AI can augment, rather than replace, the participatory and contextual dimensions of inclusion in procurement. This involves examining how algorithmic tools when guided by intersectional and feminist-technology perspectives can support data visibility, enhance transparency, and create tailored entry points for women who have historically remained outside formal contracting opportunities. In doing so, the study bridges conceptual insights from intersectionality, feminist technology studies, and socio-technical systems theory, situating AI not merely as a technical instrument but as a policy and governance tool capable of reshaping institutional equity in Nigeria’s procurement ecosystem.

The Nigerian Context: GRPP and the Shadow Gap

Nigeria’s Gender-Responsive Public Procurement (GRPP) reforms were envisioned to reduce gender disparity in access to public contracts, ensuring that women-owned and women-led enterprises could compete equitably for government tenders. However, despite the Bureau of Public Procurement (BPP)’s guidelines and sporadic adoption of gender policies by some subnational governments such as Kaduna and Lagos (Vanguard, 2025; The Guardian, 2025), implementation has remained largely symbolic. GRPP in practice still mirrors a “visibility economy” rewarding those with voice, confidence, digital fluency, and social connectivity thereby sidelining women whose circumstances or identities place them in the margins of public and digital spaces. Desk reviews of gender-responsive procurement practices in West Africa reveal persistent implementation gaps between policy commitments and actual participation of women-led enterprises, particularly in Nigeria (National Research-2, 2024).

Drawing on secondary policy data from the BPP’s vendor registry and UN Women Nigeria’s 2023 assessment, the representation of women among registered procurement vendors remains below 8%, with negligible participation from women in rural cooperatives, women with disabilities, or small-scale agro-craft entrepreneurs (UN Women, 2023; Affirmative Procurement in West Africa.org, 2024). These figures reinforce what this study terms the “shadow gap” the unrecognized exclusion of women whose barriers are multidimensional, spanning socio-cultural norms, psychological traits such as introversion, and systemic inaccessibility of digital platforms.

Disabled and neurodivergent women face compounded structural disadvantages: many procurement interfaces remain visually or cognitively inaccessible, and AI-powered portals lack assistive adaptations such as voice prompts, screen readers, or low-data modes (ILO, 2022; Nagitta et al., 2022). Similarly, introverted women often hesitant to engage in competitive or male-dominated procurement networks are overshadowed in a system that privileges assertiveness and public visibility. For culturally marginalized women, particularly in northern Nigeria, patriarchal gatekeeping continues to shape women’s economic identity, restricting their ability to bid or even register as vendors without male endorsement (Williams, 2024; Banyan Global, 2023).

Field reports from the Women in Business (WIMBIZ) database and grassroots cooperatives in Kano and Niger States reveal that many women-led agricultural and craft SMEs remain informally organized and thus invisible to AI-based data systems designed to promote inclusion. Where digital literacy exists, network access is often constrained by cost, connectivity, and cultural norms that discourage women from using smartphones freely (GSMA, 2023). Consequently, these women are algorithmically invisible; omitted from datasets that inform procurement policy and excluded from the predictive models shaping AI-driven governance tools.

Comparatively, Kenya’s “Access to Government Procurement Opportunities” (AGPO) program demonstrates how digital procurement can evolve toward inclusion when supported by targeted training and accessible e-marketplace design (World Bank, 2023). However, Nigeria’s public procurement ecosystem lacks such integration between AI innovation and human-centered design. As revealed in the desk review and policy comparison, there is a missing bridge between AI policy frameworks under the National Digital Economy Policy (2020–2030) and gender-responsive procurement mandates under the Public Procurement Act (2007). Without deliberate harmonization, technology risks amplifying existing inequalities thus reinforcing the shadow rather than illuminating it.

This contextual diagnosis underscores the urgency of reimagining procurement reform through AI-augmented human inclusion; one that treats digital infrastructure not merely as a governance tool, but as a socio-technical equalizer capable of identifying, engaging, and empowering women who exist beyond the visible perimeter of Nigeria’s economic ecosystem.

The Digital Shadow: Connectivity, Skills, and AI Awareness

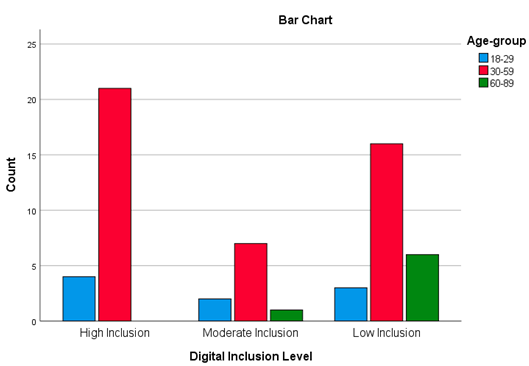

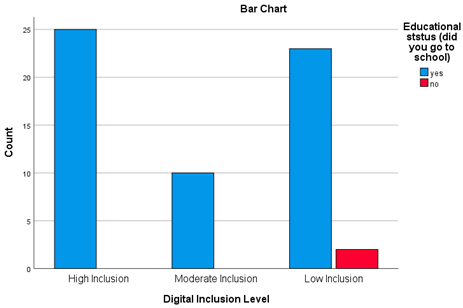

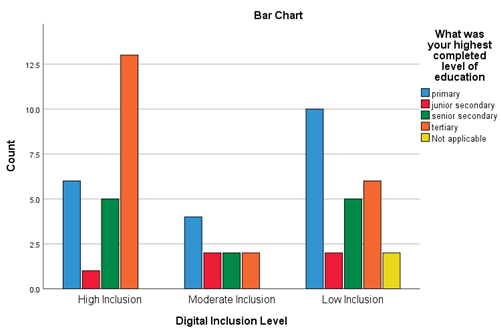

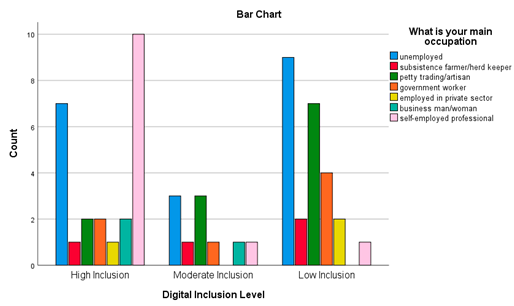

We surveyed 60 women living with mobility disability across Enugu State with age range within 18-89. Though age was not a statistically significant barrier, older women (60+) tended toward low inclusion.

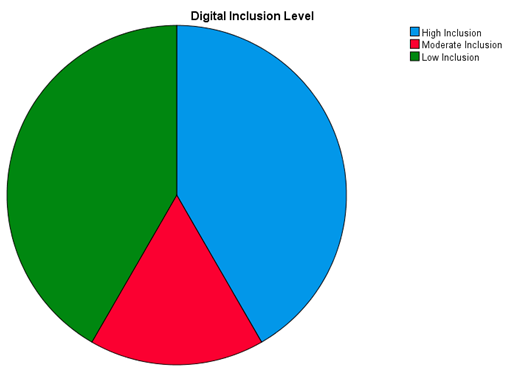

With 87% owning smartphones, half lack good internet access and 42% cannot navigate websites. Using a digital inclusion index combining device access, connectivity, skills, and AI awareness, we discovered a striking polarization: 42% of women are highly included, while another 42% remain digitally excluded.

The inequality is driven by geography. Urban residents show 75% high inclusion, while 92% of rural women fall into the low-inclusion group.

Internet access is the strongest predictor of digital skills and awareness. Women with good internet are far more likely to navigate websites and crucially 88% of them have heard of AI, compared to 0% among those with no internet.

These findings show that digital exclusion is not about willingness or education but about unequal access to connectivity and supporting infrastructure. This is the true ‘shadow’ a structural barrier that hides rural and disabled women from emerging opportunities in the digital and AI economy.

Integrating AI into GRPP: Pathways for Inclusion

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) into Gender-Responsive Public Procurement (GRPP) can provide practical solutions to improve women’s participation, transparency, and fairness in Nigeria’s procurement system. Rather than seeing AI as a futuristic tool, it can be embedded in simple, accessible ways that help the Bureau of Public Procurement (BPP), Ministries, Departments and Agencies (MDAs), and local governments make smarter, more inclusive procurement decisions.

Data-Driven Gender Mapping

AI can be used to analyze procurement data from the BPP’s e-Procurement Portal to identify gender participation patterns and disparities across regions and sectors. For example, by applying predictive analytics, the system can automatically detect when few or no women-owned or disability-inclusive businesses are participating in tenders for specific goods or services. This insight would allow the BPP to design targeted interventions such as capacity-building programs, awareness campaigns, or simplified registration processes in those sectors. Recent Nigerian scholarship demonstrates that AI-driven financial and procurement technologies can either widen or narrow gender gaps depending on governance design, data inclusion, and policy alignment (Omotubora, 2024).

In practice, this could mean linking the national supplier registration database (NSBD) with an AI dashboard that visually maps women’s participation across Nigeria. A procurement officer in Enugu, for example, could log into the dashboard and immediately see that only 10% of suppliers in her region are women-owned. The system could then suggest automatic alerts or policy prompts such as “Launch outreach for women-led agro-supply firms” or “Simplify bidding criteria for small-scale female vendors.” Such real-time visibility would make inclusion measurable and actionable.

Accessibility and User-Centered Design

Many women, especially those in rural areas or living with disabilities, find e-procurement platforms too technical or intimidating. AI tools can simplify this experience. For instance, chatbots powered by natural language processing could guide users step-by-step through registration and bidding processes in simple English, Pidgin, or local languages such as Igbo or Hausa. A woman vendor could simply type, “How do I submit my tender?” and receive an instant response with clickable actions.

For women with visual impairments or limited literacy, speech-to-text and text-to-speech AI tools could enable voice navigation and audio feedback during registration. Similarly, adaptive design where the website automatically adjusts its tone, color, and text size can make interfaces friendlier and less stressful for introverted or first-time users. The use of familiar symbols or community-based icons (like a woven basket for agricultural supply or a sewing machine for tailoring services) would further reduce confusion and anxiety.

Bias Detection and Algorithmic Transparency

A common challenge in digital procurement is the unintentional bias that may occur when automated systems rank or select vendors. AI can also help detect and correct such bias. Explainable AI (XAI) techniques can be introduced to audit decision-making algorithms used in vendor evaluation. For example, if an algorithm consistently scores female bidders lower than their male counterparts despite similar qualifications, the XAI tool will flag this inconsistency and generate a simple report showing where the bias occurred. Practically, the BPP could establish a small “Algorithm Audit Unit” to work with IT specialists and gender officers to run quarterly audits. The findings could then be uploaded to the Open Contracting Data Standards (OCDS) platform for public review, ensuring transparency and trust. By making the algorithm’s reasoning traceable, Nigeria can build confidence in AI-assisted procurement rather than skepticism.

Predictive Inclusion Models

AI can also be used to forecast how inclusive policies will perform before they are implemented. For example, if the federal government plans to allocate 30% of small contracts to women-owned businesses, AI simulation tools can analyze past procurement data to predict the number of potential beneficiaries, financial implications, and likely regional disparities.

This practical application can guide the government in setting realistic quotas and developing supportive policies. Collaborations with Nigerian universities, tech hubs, or AI innovation labs could be established to build and test these models. Students and local researchers could help develop user-friendly dashboards that visualize the “what-if” impact of gender-responsive policies. This partnership would also build local capacity for AI-driven governance, ensuring sustainability beyond donor-funded projects.

Governance, Ethics, and Human-Centered AI

Embedding AI within Gender-Responsive Public Procurement (GRPP) in Nigeria demands more than just technology, it requires ethical governance and an inclusive mindset. The goal should not be to automate exclusion under the guise of efficiency, but to design systems that amplify the voices of women who have long been absent from formal procurement spaces. International guidance emphasizes that gender-responsive procurement must integrate accessibility, decent work standards, and inclusive digital design to avoid reinforcing labor and participation inequalities (International Labour Organization [ILO], 2022).

Ethical Imperatives: Preventing Algorithmic Exclusion

AI systems are only as fair as the data and assumptions behind them. If the datasets used for training exclude small women-owned businesses, rural vendors, or persons with disabilities, the resulting models will reinforce the same inequalities they aim to solve. Ethical AI in procurement must therefore prioritize fairness and non-discrimination as key design principles.

In practice, this means that before deploying any AI tool, the Bureau of Public Procurement (BPP) and its partners should conduct Algorithmic Impact Assessments, a structured process to test how procurement algorithms might unintentionally disadvantage certain groups. For example, if a scoring algorithm tends to rank vendors based on financial turnover or past contracts, women-led cooperatives and startups may be systematically excluded. By identifying such risks early, corrective weighting or alternative evaluation parameters (like community impact or innovation potential) can be introduced.

Inclusive Data Policies

Reliable data is the foundation for inclusive AI governance. However, Nigeria’s procurement datasets rarely capture disaggregated information such as disability status, caregiving responsibilities, or language barriers. Developing clear, ethical data collection frameworks can help fill this gap without violating privacy.

For example, registration forms on the BPP e-Procurement Portal could include optional demographic fields that allow vendors to self-identify gender, disability status, and JPS for geographic location, with strict safeguards against misuse. The data can then be anonymized and used for inclusion tracking, rather than for eligibility decisions. Partnering with organizations such as WIMBIZ (Women in Management, Business and Public Service) or disability rights NGOs can help refine these questions to ensure cultural sensitivity and trust.

Building Trust Through Explainable AI

AI adoption in public procurement will only succeed if people trust the system. In Nigeria’s context where citizens often associate technology-driven processes with opacity or favoritism, explainability becomes essential. Explainable AI (XAI) techniques allow end users to understand how and why decisions were made. For instance, when a female bidder’s proposal is not shortlisted, the platform could automatically generate a simple explanation like, “Bid not selected because document upload was incomplete - please resubmit.” Such feedback demystifies digital decisions and reduces suspicion of bias. In rural or culturally conservative areas, this transparency can build gradual confidence in the digital system, especially when paired with local-language support and public sensitization through community radio or women’s cooperatives.

Participatory AI Design

A human-centered approach to AI in procurement means developing tools with the people they are meant to serve, not for them. Participatory design ensures that the lived experiences of women, persons with disabilities, and marginalized entrepreneurs shape both the functionality and ethics of AI systems. Practically, this could involve pilot workshops where representatives from women’s cooperatives, trade associations, and NGOs co-create AI-assisted procurement prototypes with developers and BPP officials. For instance, a co-design session with the National Association of Women Entrepreneurs (NAWE) might reveal that most rural traders access the internet only via mobile phones. This insight could guide developers to prioritize lightweight, mobile-first AI applications instead of heavy web dashboards. Moreover, participatory mechanisms should be institutionalized, not ad-hoc. The BPP can establish an “AI Inclusion Advisory Council” that meets quarterly to review data ethics, usability feedback, and algorithmic audit results. Such consistent engagement would anchor accountability in local ownership rather than donor-driven compliance.

Implementation Roadmap for Nigeria

Operationalizing the integration of Artificial Intelligence into gender-responsive public procurement (GRPP) in Nigeria requires a carefully sequenced and context-sensitive roadmap that aligns with national priorities, institutional realities, and socio-cultural considerations. The roadmap should begin with policy alignment and gradually progress into technical, institutional, and monitoring phases to ensure long-term sustainability.

The first step involves policy integration. This will require the Federal Ministry of Finance, Budget, and National Planning (FMFBNP), working alongside the Bureau of Public Procurement (BPP), to embed AI inclusion frameworks within the existing GRPP guidelines. Such integration would ensure that data-driven and gender-aware approaches are institutionalized within procurement regulations and tender evaluation processes. To achieve this, inter-ministerial collaboration must be established between agencies such as the National Information Technology Development Agency (NITDA), the Ministry of Women Affairs, and the Office of the Head of the Civil Service. These bodies can work together to develop a National AI Inclusion Policy tailored to procurement governance.

Following policy reform, the next critical phase focuses on technical integration. This step involves upgrading Nigeria’s e-Procurement platforms to include inclusion-focused AI modules capable of identifying patterns of gender and geographic disparity in contract awards. By embedding AI-driven dashboards into platforms such as the Nigeria Open Contracting Portal (NOCOPO), procurement officers can easily track participation rates of women-owned businesses, youth-led enterprises, and marginalized community vendors. Pilot programs should begin at the federal level and later extend to states with strong procurement reform histories such as Kaduna, Lagos, and Enugu.

As technology adoption progresses, building institutional capacity becomes indispensable. This stage should prioritize the establishment of AI and digital literacy pipelines that specifically target women and underrepresented groups within the informal economy. Partnerships with polytechnics, women’s cooperatives, and local innovation hubs can facilitate short-term training and mentorship programs aimed at equipping women entrepreneurs with the skills to navigate digital tender platforms and interpret AI-generated insights. Additionally, public servants responsible for procurement processes must undergo targeted reskilling programs in AI ethics, data interpretation, and inclusive decision-making to prevent the replication of bias through automation.

The final stage of implementation is the development of a robust monitoring and evaluation (M&E) framework. This phase will introduce measurable indicators of “shadow visibility” a concept referring to the extent to which previously excluded or invisible groups become represented within procurement datasets. Metrics may include the percentage increase of women-owned enterprises in procurement participation, geographic diversity in vendor representation, and the transparency of algorithmic decision-making processes. Continuous data collection and periodic reviews will allow policymakers to refine AI systems and ensure that they promote fairness rather than reinforce existing disparities.

Recommendations

To ensure the successful integration of Artificial Intelligence into gender-responsive public procurement in Nigeria, a multilayered and actionable framework is required. This framework must combine policy reform, technological innovation, capacity enhancement, and collaborative research to achieve sustainable inclusion. At the policy level, it is crucial for the Federal Government, through the Bureau of Public Procurement (BPP) and the Ministry of Finance, Budget, and National Planning, to institutionalize AI-driven gender dashboards across all procurement portals. Such dashboards would allow real-time tracking of gender participation, contract distribution, and regional inclusivity within procurement data. Additionally, periodic inclusivity audits should be mandated to evaluate the performance of ministries, departments, and agencies (MDAs) in implementing gender-responsive practices. These audits would create accountability loops and enable evidence-based adjustments to procurement strategies. By embedding these tools within national procurement laws, Nigeria can ensure that gender equity becomes a measurable outcome rather than a rhetorical goal. At the technology level, the adoption of open-source AI models tailored to Nigeria’s socio-economic and linguistic realities should be encouraged. Proprietary systems, while often powerful, are expensive and lack contextual adaptability. Open-source frameworks, on the other hand, allow local developers, researchers, and civil society organizations to modify algorithms to reflect cultural nuances and procurement priorities. Lessons can be drawn from India’s Government e-Marketplace (GeM) initiative, which successfully integrated open data and AI tools to enhance vendor diversity and transparency. A similar approach in Nigeria could democratize AI access, stimulate local innovation, and reduce dependency on imported technologies. In terms of capacity building, deliberate partnerships should be fostered between government institutions, polytechnics, women’s business associations, and non-governmental organizations. These partnerships should focus on delivering inclusive AI and digital literacy programs targeted at women entrepreneurs, particularly those in informal and rural sectors. Collaborations with organizations such as the Women in Management, Business and Public Service (WIMBIZ) and grassroots cooperatives can facilitate mentorship programs and peer learning opportunities. Rwanda’s Umurenge digital inclusion initiative provides a relevant model in this regard, demonstrating how community-based training and women-led tech groups can accelerate inclusive digital transformation. Finally, research and collaboration should serve as the backbone of sustainability. Nigeria can establish pilot projects co-developed by AI Nigeria, WIMBIZ, and international partners such as UN Women to explore the intersection of AI ethics, procurement governance, and social inclusion. These pilots should be evidence-based and continuously evaluated to generate data that inform national policy. Kenya’s Ajira Digital program offers an instructive example of how government/private sector partnerships can expand digital opportunities for youth and women while ensuring equitable participation in technology ecosystems.