1. Introduction

With the rapid advancement of science and technology, sustainable development has become a pivotal objective of contemporary economic and social progress. As a crucial driving force behind the evolution of new energy vehicles, autonomous driving technology stands as one of the indispensable enablers for achieving sustainable development goals, attracting extensive attention from researchers in both the artificial intelligence and automotive engineering communities. With the rapid development of autonomous driving technologies, the detection of multi-modal 3D objects has become a key component of environmental perception systems [

1,

2,

3]. By merging information from cameras and LiDAR sensors, existing methods have achieved significant progress in complex traffic scenarios [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Among them, Bird’s-Eye View (BEV)–based fusion frameworks have attracted considerable attention due to their unified spatial representation and strong scalability. However, in nighttime or low-light environments, the quality of sensor data degrades significantly, and visual features suffer severe deterioration, which leads to a noticeable decline in the overall performance of multi-modal perception systems.

Most existing multi-modal BEV-based detection methods are primarily designed for daytime or well-illuminated scenarios, and thus face multiple challenges when deployed in nighttime environments. On the one hand, nighttime images suffer from insufficient illumination, increased noise, and reduced contrast, which significantly weakens the discriminative capability of visual features and consequently degrades the effectiveness of cross-modal fusion. On the other hand, some approaches rely on Transformer-based cross-modal attention mechanisms to achieve deep feature interaction; however, their high computational complexity and memory consumption limit practical deployment on resource-constrained platforms. In addition, nighttime datasets typically contain a higher proportion of small objects and sparse-category samples. The use of a unified loss function often fails to effectively model the varying importance of different samples, leading to unstable training behavior or constrained performance.

Motivated by the prevalent challenges in nighttime multi-modal 3D object detection, including perception degradation, imbalanced cross-modal reliability, and uneven training supervision, this work explores a lightweight BEV-based detection framework tailored for nighttime autonomous driving scenarios. Unlike conventional approaches that primarily focus on enhancing the feature fusion stage, we adopt a task-driven perspective that jointly considers nighttime visual characteristics, cross-modal information interaction, and supervision modeling within a unified detection framework.

The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

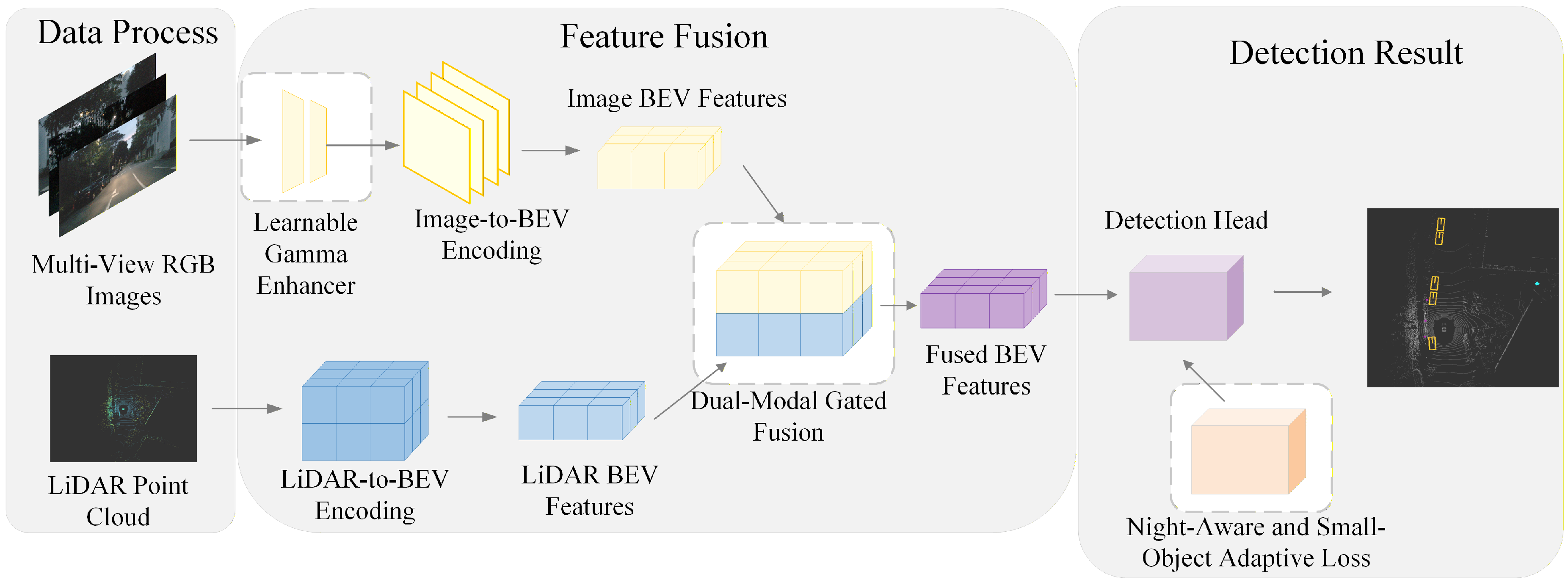

A lightweight multi-modal 3D object detection framework tailored for nighttime autonomous driving scenarios is proposed. Based on the BEVFusion baseline, the framework adopts a task-driven joint modeling strategy, which effectively enhances perception performance under complex nighttime illumination conditions without introducing a significant increase in computational overhead.

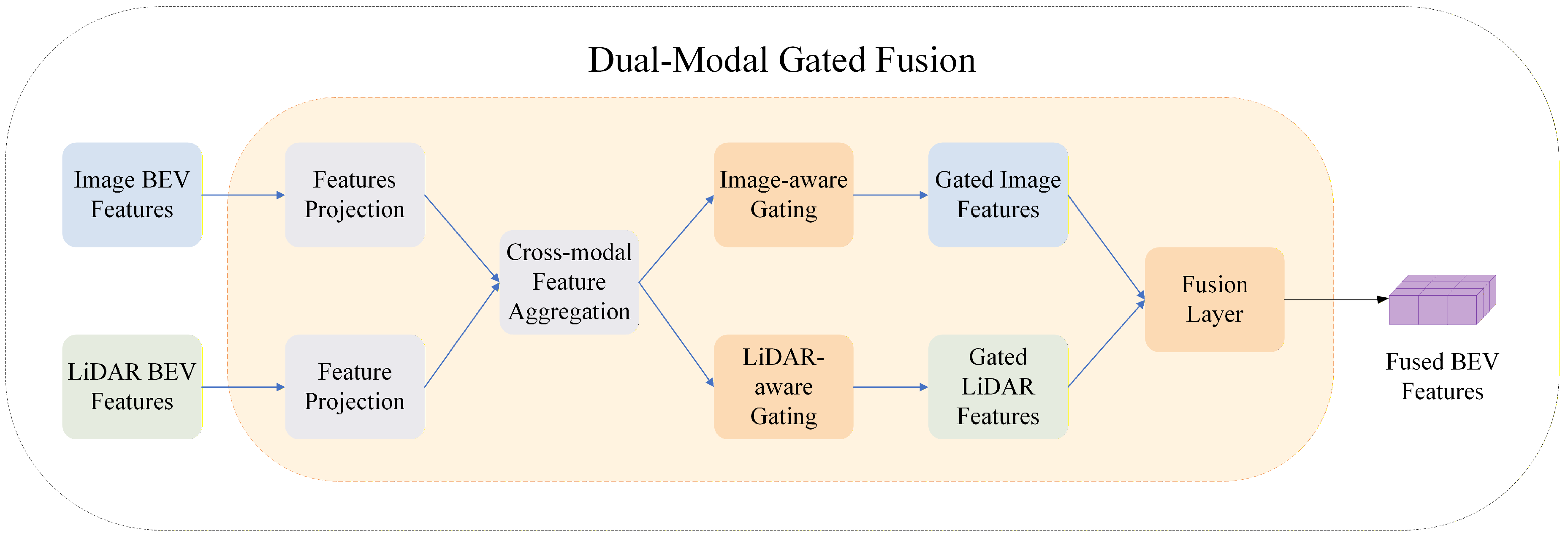

A Dual-modal Gated Fusion(DMGF) mechanism is designed. By adaptively adjusting the feature weights of camera and LiDAR modalities, this mechanism enables stable cross-modal information interaction and effectively mitigates the adverse impact of single-modality degradation on detection performance in nighttime environments.

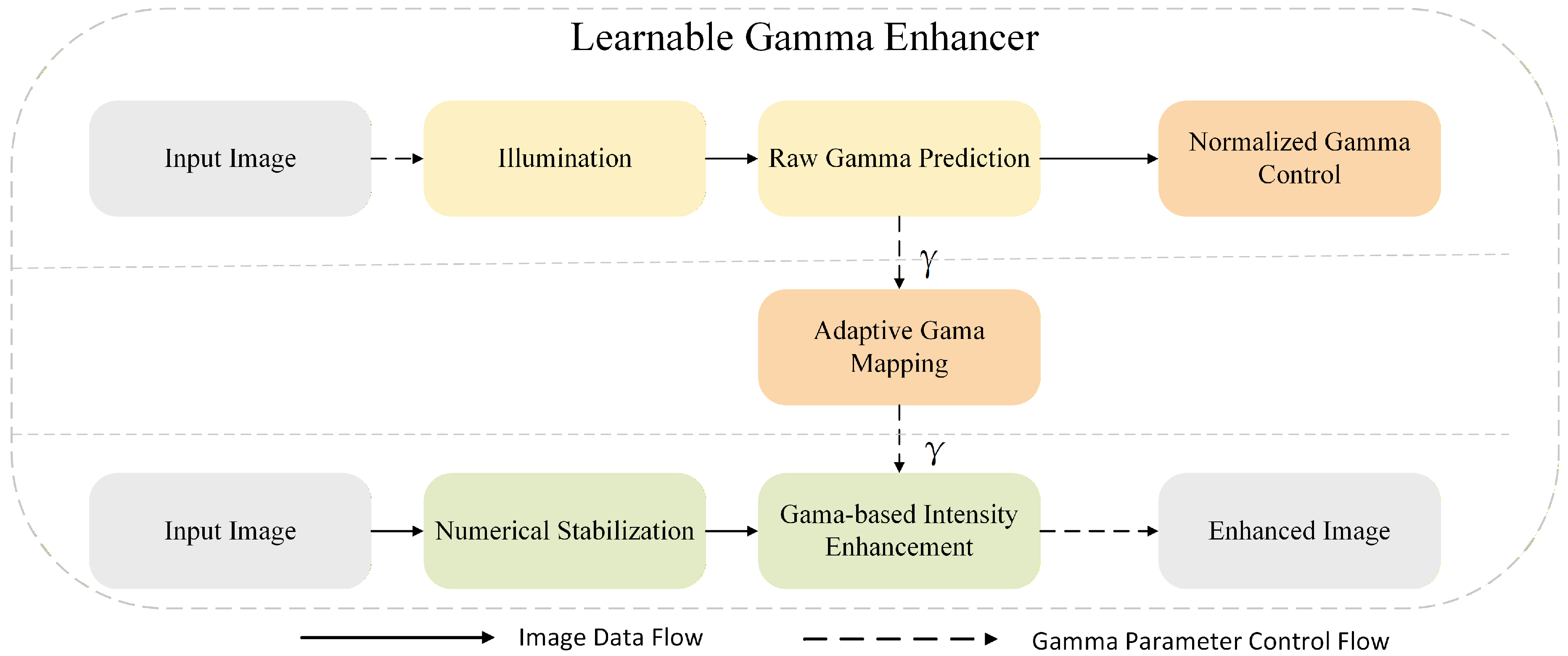

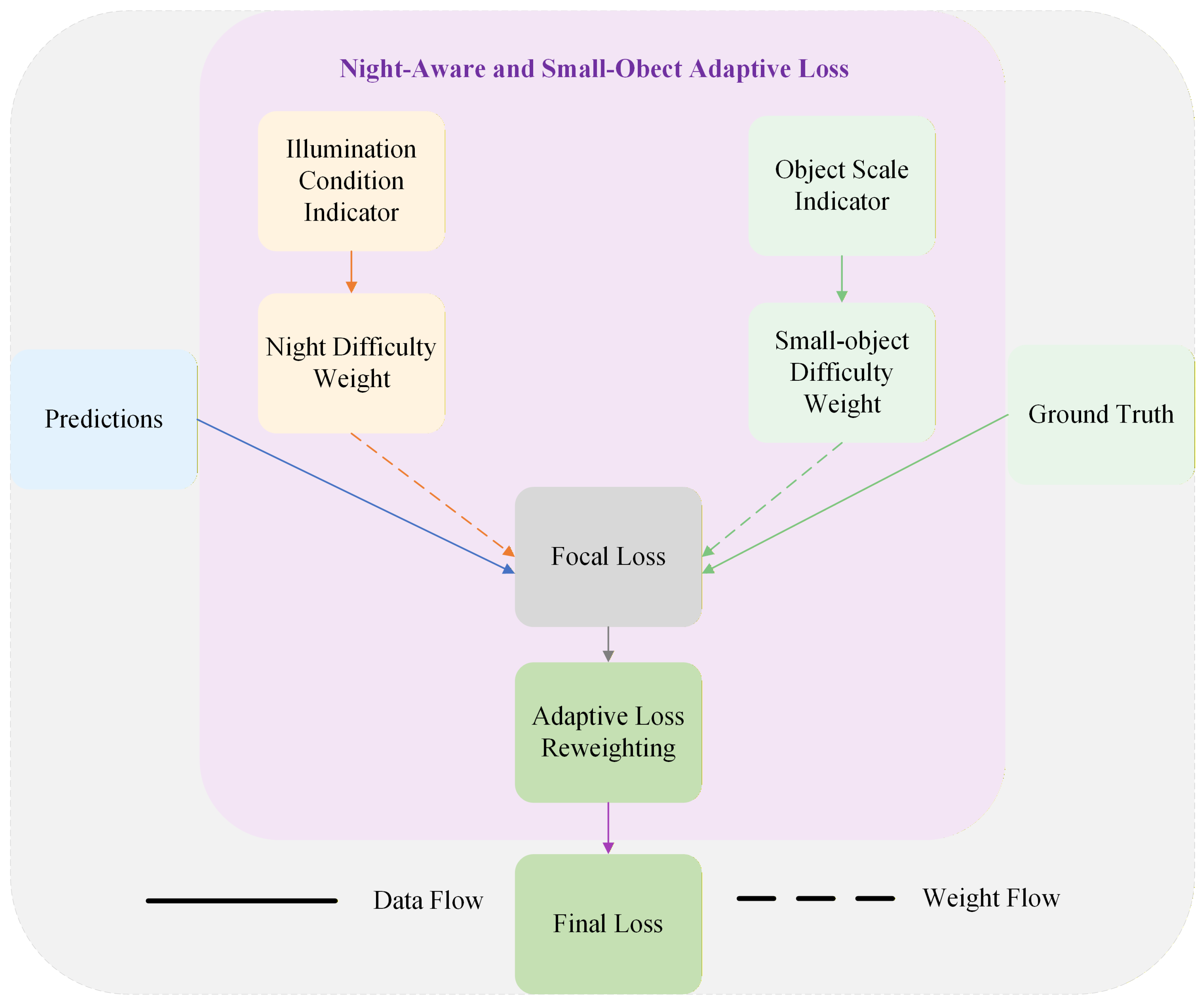

In response to the high proportion of small objects, abundant weakly supervised samples, and unstable training in nighttime scenarios, an adaptive supervision strategy based on learnable weight modulation is proposed. By integrating a learnable gamma enhancer module with a night-aware and small-object adaptive weighting mechanism, the supervision strength for different.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 introduces the background and challenges of this study.

Section 3 describes the framework of the proposed detection model, which is the core of this study. The evaluation criterion simulation results are presented in

Section 4 and, finally,

Section 5 gives the conclusions.

4. Experiments

To comprehensively evaluate the detection performance, generalization ability, and robustness of the proposed method under nighttime conditions, a series of systematic experiments is designed and conducted. These experiments include not only comparative analyses of overall performance against existing methods, but also further investigations into model behavior with respect to category distribution characteristics and under different testing conditions.

4.1. Experimental Setup

4.1.1. Dataset and Evaluation Metrics

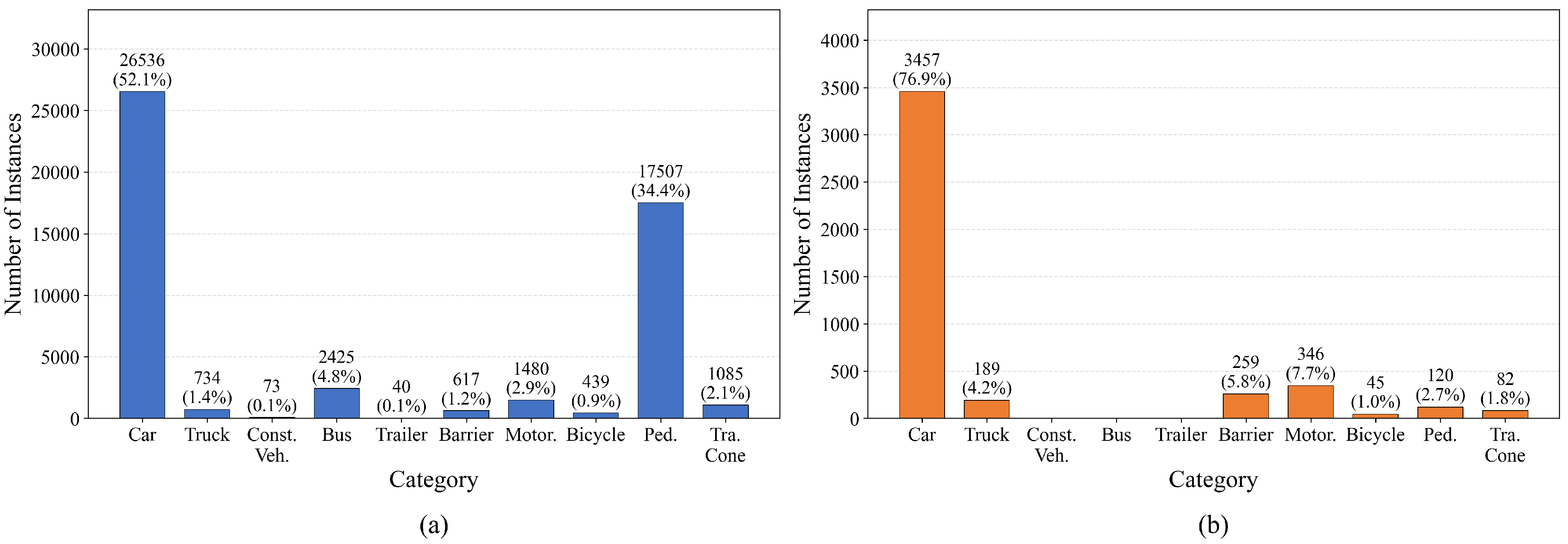

All experiments in this study are conducted on the nuScenes dataset. To specifically investigate multi-modal perception under nighttime conditions, a nuScenes-Night subset is constructed by filtering the original nuScenes dataset to include only multi-modal data collected in nighttime or low-light environments. During training, all models are trained exclusively on the nuScenes-Night subset. During testing, evaluations are consistently performed on the nuScenes-Night validation set. Model performance is assessed using the official nuScenes evaluation metrics, primarily including mAP and NDS. The classification of the dataset is shown in

Figure 5.

As shown in

Figure 5, the training and validation sets exhibit consistent overall trends in category distribution, both displaying pronounced long-tailed characteristics. Among all categories, cars and pedestrians dominate in terms of sample quantity, significantly exceeding other classes, which reflects the high occurrence frequency of vehicles and pedestrians in real-world driving scenarios.

In contrast, categories such as Construction Vehicle, Trailer, and Barrier contain substantially fewer samples and can be regarded as typical low-frequency classes. These categories are more susceptible to the effects of class imbalance during training. Under such data distribution characteristics, overall detection performance is inherently constrained. Nevertheless, even in the presence of severe class imbalance and long-tailed distributions, the proposed method achieves stable performance improvements, demonstrating its effectiveness and robustness in complex data distribution scenarios.

On the nuScenes dataset, model performance is evaluated using the official nuScenes evaluation protocol. Overall detection performance is primarily measured by the nuScenes Detection Score (NDS). In addition, mean Average Precision (mAP) and mean Translation Error (mATE) are reported to characterize detection accuracy and 3D spatial localization precision, respectively.

In this work, model performance on the nuScenes dataset is evaluated using the official nuScenes evaluation protocol. The primary metric used for overall detection performance is the nuScenes Detection Score (NDS), which is a comprehensive measure that reflects both detection coverage and quality by combining multiple evaluation aspects into a unified score. Specifically, NDS integrates average precision with multiple true positive error terms to provide a balanced assessment of detection completeness and localization accuracy under various conditions[

32].

In addition to NDS, the mean Average Precision (mAP) is reported to quantify the detection coverage capability. In the context of nuScenes, mAP measures the ability of the model to detect and correctly localize objects within predefined center-distance thresholds, averaging precision scores across different object categories. A higher mAP indicates better overall recall and precision in object detection[

32].

To further characterize localization performance, the mean Average Translation Error (mATE) is used to evaluate the average deviation between predicted and ground-truth 3D object centers. Lower mATE values correspond to more precise 3D spatial localization, which is essential for accurate perception in autonomous driving systems[

32].

4.1.2. Implementation Details

The proposed method is implemented based on the BEVFusion framework. Model training is performed using the AdamW optimizer with an initial learning rate of 0.0002, together with a learning rate scheduling strategy consisting of linear warm-up (500 iterations) followed by cosine annealing. During training, the batch size is set to 6, and all models are trained for 20 epochs. Unless otherwise specified, all comparison methods and ablation experiments adopt identical training configurations to ensure fairness and comparability of the experimental results. All experiments are conducted on an NVIDIA A6000 GPU with 48 GB of memory. The software environment includes Linux, Python 3.10.19, PyTorch 2.0.1, CUDA 11.8, and cuDNN 8.7. The models are implemented using the MMDetection3D framework.

4.1.3. Comparison Methods and Ablation Settings

To systematically evaluate the impact of each component on nighttime multi-modal 3D object detection, BEVFusion is adopted as the baseline multi-modal detection framework. Based on this baseline, a learnable gamma enhancer module, a DMGF module, and a night-aware and small object adaptive loss function are progressively incorporated to construct different model variants for ablation studies. By comparing the detection results of these variants under identical experimental conditions, the individual contributions and collaborative effects of each module on the overall performance are analyzed. To ensure the reliability and comparability of the experimental conclusions, all ablation experiments are conducted using consistent dataset splits, training strategies, and evaluation metrics.

For the overall performance comparison, CenterPoint is selected as a representative single-modality LiDAR-based 3D object detection method to analyze the performance differences between multi-modal fusion approaches and single-modality solutions in complex nighttime scenarios. In addition, FCOS3D, a representative monocular 3D detection method, is included as an additional baseline to provide a broader comparative perspective, enabling a more comprehensive evaluation of the effectiveness and robustness of the proposed method under nighttime conditions.

4.1.4. Generalization and Robustness Evaluation Setup

To evaluate the generalization ability and robustness of the proposed method under nighttime conditions, a series of experiments is designed and conducted without retraining the model, using the weights obtained after training. All experiments are performed on the full nuScenes validation set to ensure completeness and consistency of the evaluation.

For both generalization and robustness assessments, inference and performance evaluation are carried out on the full nuScenes validation set using the trained model weights, without any additional fine-tuning. By keeping the model architecture, learned parameters, and inference settings unchanged, and only altering the input conditions at the testing stage, the model’s performance under different test scenarios can be systematically analyzed.

Specifically, for the generalization evaluation, the model is directly tested on the original full nuScenes validation set to assess its overall generalization performance under the complete data distribution. For the robustness evaluation, additional nighttime noise perturbations are introduced into the validation inputs to simulate sensor noise and imaging instability commonly encountered in nighttime scenarios. The detection results under noisy conditions are then compared with those obtained under noise-free settings, enabling a quantitative assessment of the model’s stability and robustness under degraded input conditions. All experiments are evaluated using the same set of metrics to ensure comparability across different testing conditions. The corresponding experimental results and analyses are presented in subsequent sections.

4.2. Overall Performance Comparison

Given the differences in perception reliability across modalities in nighttime scenarios, multi-modal fusion strategies have a significant impact on detection performance. Therefore, under a unified experimental setup, this paper conducts comparative experiments to analyze the proposed method alongside various representative detection methods. In addition to the multi-modal baseline model, CenterPoint and FCOS3D[

31] are also introduced as comparison objects. FCOS3D is a single-modality image-based detection method, while CenterPoint is a single-modality LiDAR-based detection method. This paper compares the performance of FCOS3D and CenterPoint as reference methods. The experimental results are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of different methods on nuScenes-Night dataset

Table 1.

Comparison of different methods on nuScenes-Night dataset

| Method |

Modality |

mAP |

NDS |

mATE |

| Bevfusion(baseline) |

C+L |

0.2727 |

0.3292 |

0.5572 |

| CenterPoint |

L |

0.2579 |

0.3603 |

0.4569 |

| FCOS3D |

C |

0.0494 |

0.1344 |

0.9492 |

| +DMGF |

C+L |

0.2700 |

0.3336 |

0.5379 |

| Ours |

C+L |

0.2753 |

0.3405 |

0.5272 |

The proposed method, Ours, achieves the best performance in balancing detection accuracy and localization precision, with mAP and NDS values of 0.2753 and 0.3405, respectively, and a reduced mATE of 0.5272.

In contrast, the CenterPoint method, relying solely on LiDAR, shows lower localization error (mATE = 0.4569) but significantly lower mAP, indicating that relying on a single modality in nighttime scenarios limits detection performance.

FCOS3D performs poorly with low mAP (0.0494), NDS (0.1344), and high mATE (0.9492), indicating its weakness in both object detection and localization, particularly in complex or low-light environments.

Multi-modal methods, combining camera and LiDAR data, offer more stable performance. Introducing the DMGF module to the BevFusion baseline model improves NDS from 0.3292 to 0.3336 and reduces mATE from 0.5572 to 0.5379, highlighting the value of cross-modal feature fusion.

Finally, Ours outperforms the baseline with +0.0026 in mAP, +0.0113 in NDS, and -0.0300 in mATE, demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed multi-modal co-modeling approach.

Despite challenges like low illumination, small objects, and class imbalance in nighttime scenarios, the proposed method consistently improves performance across evaluation metrics, proving its robustness in complex detection tasks.

4.3. Ablation Study

4.3.1. Module-wise and Ablation Study Analysis

Although the proposed method improves nighttime perception performance through coordinated modeling of multiple modules, it is still necessary to disentangle and analyze the individual contributions of each component to the overall performance gains. Therefore, this section conducts ablation experiments to further investigate the effects of the input enhancement module, the cross-modal fusion module, and the loss modeling strategy. The experimental results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Ablation study of different modules on the night-time detection task.

Table 2.

Ablation study of different modules on the night-time detection task.

| DMGF |

Gamma |

Final Loss |

mAP |

NDS |

| × |

× |

× |

0.2727 |

0.3292 |

| |

× |

× |

0.2700 |

0.3336 |

| × |

|

× |

0.2537 |

0.3204 |

| × |

× |

|

0.2591 |

0.3381 |

| |

|

|

0.2753 |

0.3405 |

Table 2 reports the ablation results of the proposed key modules on the nuScenes nighttime subset. Based on these metrics, introducing the DMGF module alone yields a stable improvement in NDS, validating its effectiveness in facilitating multi-modal feature interaction under nighttime conditions.

When the learnable Gamma enhancement module is applied in isolation, a slight degradation in overall performance is observed. This indicates that relying solely on low-light enhancement without sufficient task-level constraints may lead to brightness adjustments that are not well aligned with the detection objective.

In contrast, the night-aware and small-object adaptive loss achieves a notable improvement in NDS even without image enhancement, highlighting its capability to effectively model weakly supervised samples in nighttime scenarios. When all three modules are jointly employed, the model attains the best performance on both mAP and NDS. This demonstrates that the proposed low-light enhancement, cross-modal fusion, and adaptive loss components exhibit strong synergy and complementarity, leading to a significant improvement in overall nighttime multi-modal 3D object detection performance.

4.3.2. Training Stability Analysis

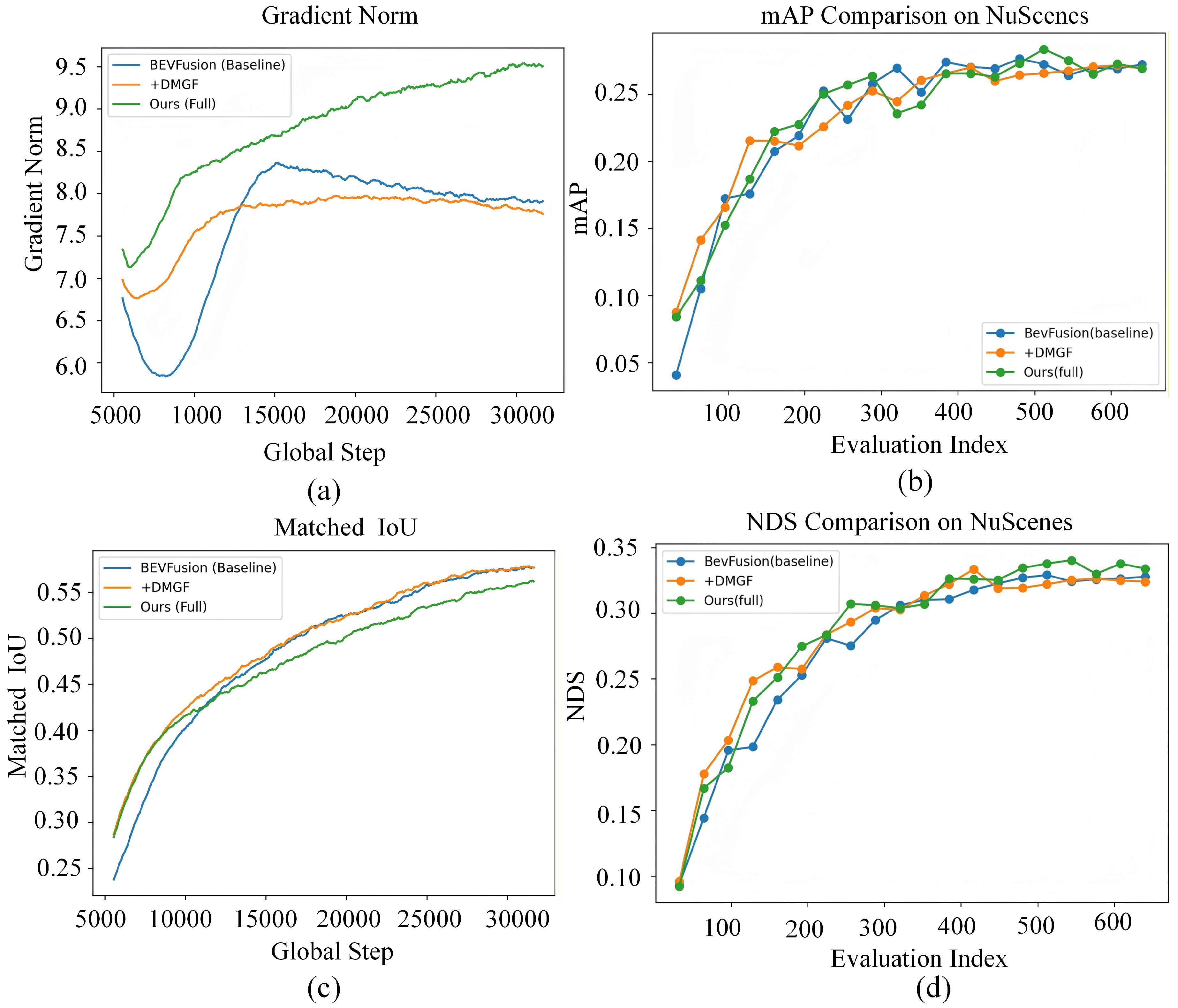

To further analyze the impact of different modules on training behavior and optimization dynamics, a comparative analysis of training stability is conducted based on the ablation experiments. Specifically, the baseline model BEVFusion, the model equipped with the +DMGF module, and the full model Ours are selected for comparison. Their gradient evolution and performance convergence behaviors during training are analyzed, as illustrated in

Figure 6.

Figure 6.(a) illustrates the evolution of gradient norms during training for different methods. It can be observed that the baseline model exhibits noticeable gradient fluctuations in the early training stage. After introducing the DMGF module, the gradient variations become smoother, indicating that conflicts between cross-modal features are alleviated to some extent. In comparison, the full model maintains stable gradient behavior while exhibiting a higher overall gradient magnitude, suggesting that the introduced enhancement and supervision mechanisms provide richer and more stable training signals.

Figure 6.(b)–(d) present the evolution of mAP, matched IoU, and NDS throughout the training process. The full model demonstrates more stable performance improvements in the middle and later stages of training and consistently outperforms the compared methods across multiple evaluation metrics. This indicates that the proposed approach not only achieves superior final performance, but also exhibits improved convergence quality and training stability.

It should be noted that, in the training dynamics analysis, training curves for the learnable Gamma enhancer module and the night-aware loss function are not plotted separately. This is because the Gamma enhancement primarily affects feature distribution modeling at the input level and does not directly introduce new optimization dynamics, while the influence of the night-aware and small-object adaptive loss on training behavior is already reflected in the overall gradient evolution and performance convergence of the full model. Therefore, the effectiveness of these modules is validated through a combination of ablation results and overall training dynamics analysis, avoiding redundant visualization of intermediate processes.

4.4. Performance Analysis on Representative Nighttime Categories

Although overall metrics can reflect the general detection capability of a model, they are insufficient to reveal the specific perception challenges faced by different object categories under nighttime conditions. Therefore, this section conducts a category-wise detection accuracy analysis to examine the performance variations of the proposed method across representative nighttime categories. The experimental results are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Per-class detection accuracy comparison on representative night-time categories.

Table 3.

Per-class detection accuracy comparison on representative night-time categories.

| Method |

Car |

Pedestrian |

Motorcycle |

Bicycle |

Barrier |

Truck |

| Baseline |

0.8222 |

0.4345 |

0.6435 |

0.2519 |

0.0552 |

0.5193 |

| +DMGF |

0.8244 |

0.4453 |

0.6454 |

0.1276 |

0.0421 |

0.6154 |

| Ours |

0.8419 |

0.4205 |

0.7665 |

0.2067 |

0.0604 |

0.4574 |

It can be observed that the proposed lightweight cross-modal fusion module achieves consistent performance improvements on categories such as Car, Motorcycle, and Truck, indicating its effectiveness in enhancing complementary information between image and LiDAR features.

For extremely small-object categories such as Bicycle and Barrier, performance fluctuations are observed for some methods when cross-modal fusion is introduced alone, due to the limited number of nighttime samples and increased noise levels. When combined with the night-aware adaptive enhancement and loss reweighting strategies, the complete model delivers more consistent performance across most key nighttime categories. These results further validate the effectiveness and robustness of the proposed approach for nighttime multi-modal 3D object detection.

4.5. Efficiency Comparison

Given the stringent requirements on real-time performance and computational resources in nighttime autonomous driving perception systems, computational efficiency is as critical as detection accuracy. Therefore, this section presents a comparative analysis of the proposed method and the baseline model in terms of parameter scale and inference efficiency. The experimental results are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Efficiency comparison of different fusion strategies.

Table 4.

Efficiency comparison of different fusion strategies.

| Method |

Params (M) |

Fusion Params (M) |

FPS (batch=1) |

GFLOPs |

| BEVFusion |

40.80 |

0.77 |

2.69 |

89.61 |

| +DMGF |

41.02 |

1.00 |

2.69 |

96.81 |

| +Dual Cross-Attention |

46.87 |

6.84 |

N/A |

64.84 |

| Ours |

41.02 |

1.00 |

2.68 |

96.81 |

In terms of model size, the original BEVFusion model contains a total of 40.80M parameters, of which approximately 0.77M are attributed to the fusion module. After introducing the DMGF module, the total number of parameters increases only marginally to 41.02M. The additional parameters mainly originate from the fusion layers, resulting in an overall increase of less than 1%, which indicates that the proposed fusion design imposes almost no additional burden on model complexity.

In contrast, the Dual Cross-Attention fusion scheme based on global attention mechanisms significantly increases model complexity. Its total parameter count reaches 46.87M, with the fusion module alone accounting for 6.84M parameters. This demonstrates that although Transformer-based cross-modal attention enhances feature interaction, it introduces substantial parameter and computational overhead, making it less suitable for deployment in resource-constrained scenarios.

With respect to inference efficiency, the BEVFusion baseline achieves an inference speed of 2.69 FPS. After incorporating DMGF and the complete proposed method, the inference speed remains approximately 2.69 FPS, with no noticeable degradation. This indicates that the proposed lightweight cross-modal fusion and low-light enhancement strategies can improve detection performance without sacrificing inference efficiency. Due to the large memory consumption of the Dual Cross-Attention module under the current hardware configuration, stable inference could not be achieved; therefore, its FPS results are not reported.

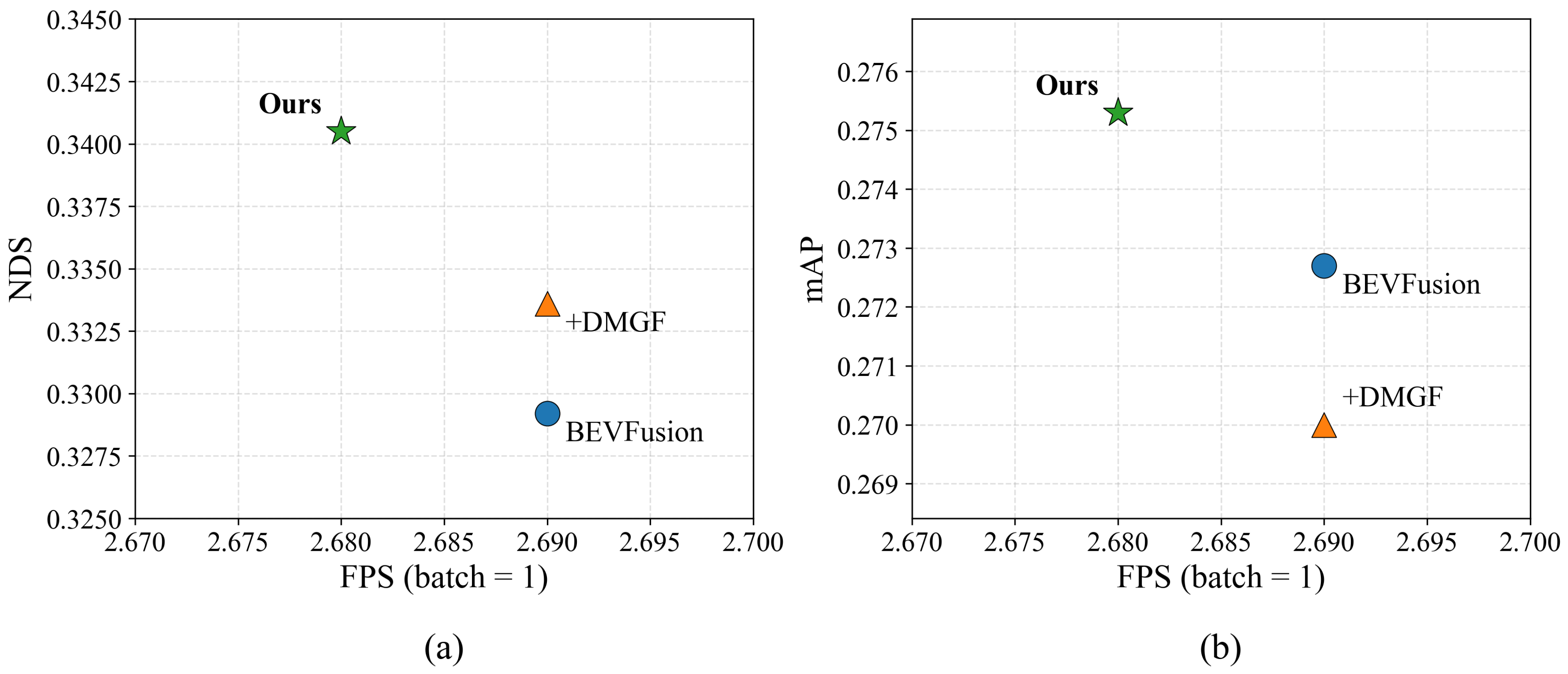

While improving detection performance, inference efficiency remains a critical factor for practical autonomous driving applications. To further analyze the trade-off between performance and efficiency, a comparative evaluation of detection performance versus inference speed under identical inference settings is conducted for different methods, as illustrated in

Figure 7.

As illustrated in

Figure 7.(a) and

Figure 7.(b), the compared methods exhibit a clear accuracy–efficiency trade-off in the FPS–NDS and FPS–mAP spaces. Compared with the BEVFusion baseline, +DMGF achieves noticeable performance gains while maintaining almost identical inference speed. The proposed full model attains the highest NDS and mAP with only a marginal reduction in inference speed (from 2.69 FPS to 2.68 FPS), demonstrating superior overall detection performance. These results indicate that the proposed approach achieves substantial accuracy improvements at a negligible efficiency cost, yielding a more favorable Pareto-optimal solution for multi-modal nighttime detection tasks.

4.6. Generalization and Robustness Experiments

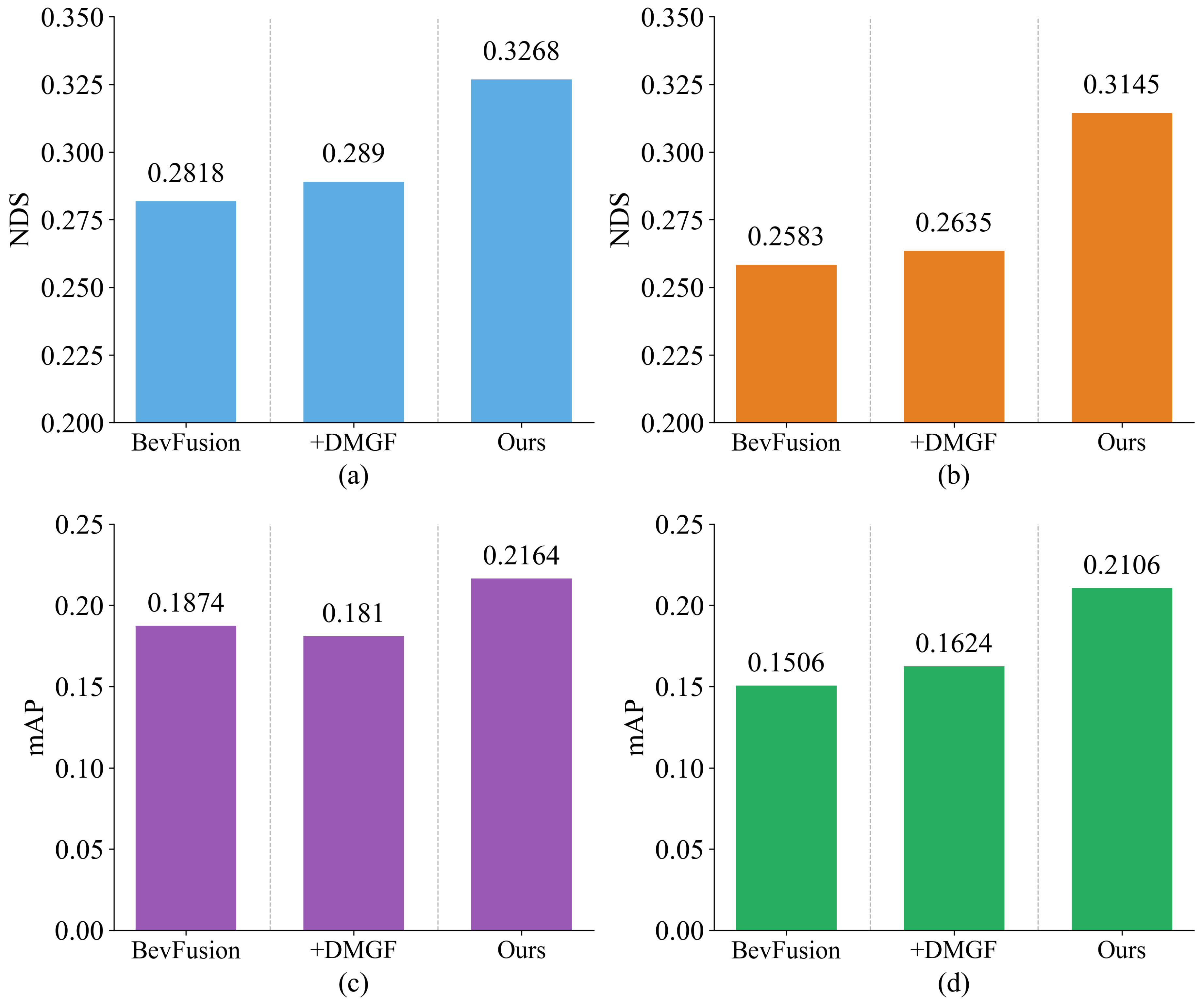

To evaluate the generalization capability of the proposed method under different scene distributions and perception degradation conditions, this section designs generalization experiments by validating the trained model weights on the full nuScenes validation set. For robustness evaluation, simulated nighttime noise perturbations are introduced into the full nuScenes validation set to mimic additional input degradations caused by sensor noise and imaging instability commonly encountered in nighttime scenarios. This setup aims to assess the stability of the proposed method under more challenging nighttime conditions. The experimental results are summarized in Table 5 and

Figure 8.

Figure 8 visualizes the variations in NDS and mAP of different methods under noise-free conditions and with simulated nighttime noise perturbations. It can be observed that after introducing nighttime noise, the detection performance of all methods degrades to some extent; however, clear differences are evident in their performance trends. In particular, the proposed method maintains relatively smooth performance variations before and after noise perturbation, exhibiting more stable detection behavior.

Table 5.

Generalization and robustness performance of different methods evaluated on the full nuScenes validation set after training on the nuScenes-Night dataset.

Table 5.

Generalization and robustness performance of different methods evaluated on the full nuScenes validation set after training on the nuScenes-Night dataset.

| Method |

Noise |

NDS |

NDS ↓ |

mAP |

mAP ↓ |

| BEVFusion |

× |

0.2818 |

– |

0.1874 |

– |

| |

|

0.2583 |

-0.0235 |

0.1506 |

-0.0368 |

| +DMGF |

× |

0.2890 |

– |

0.1810 |

– |

| |

|

0.2635 |

-0.0255 |

0.1624 |

-0.0186 |

| Ours |

× |

0.3268 |

– |

0.2164 |

– |

| |

|

0.3145 |

-0.0123 |

0.2106 |

-0.0061 |

Furthermore, Table 5 provides a quantitative analysis of performance degradation for different methods under noisy conditions. By comparing the changes in NDS and mAP, it is evident that, relative to the baseline and the model equipped only with DMGF, the proposed method experiences a smaller degree of performance degradation under nighttime noise perturbations. This demonstrates its superior stability and robustness when faced with input degradations.

Despite these challenges, the model is able to stably detect major traffic participants, such as vehicles, pedestrians, and two-wheeled objects, across most views, while maintaining reasonable spatial layouts and object orientations in the BEV representation. The missed detections do not introduce noticeable disruptions to the overall spatial modeling, indicating that the proposed method exhibits good detection stability and robust multi-modal fusion capability in complex nighttime environments.

4.7. Visualization Result Analysis

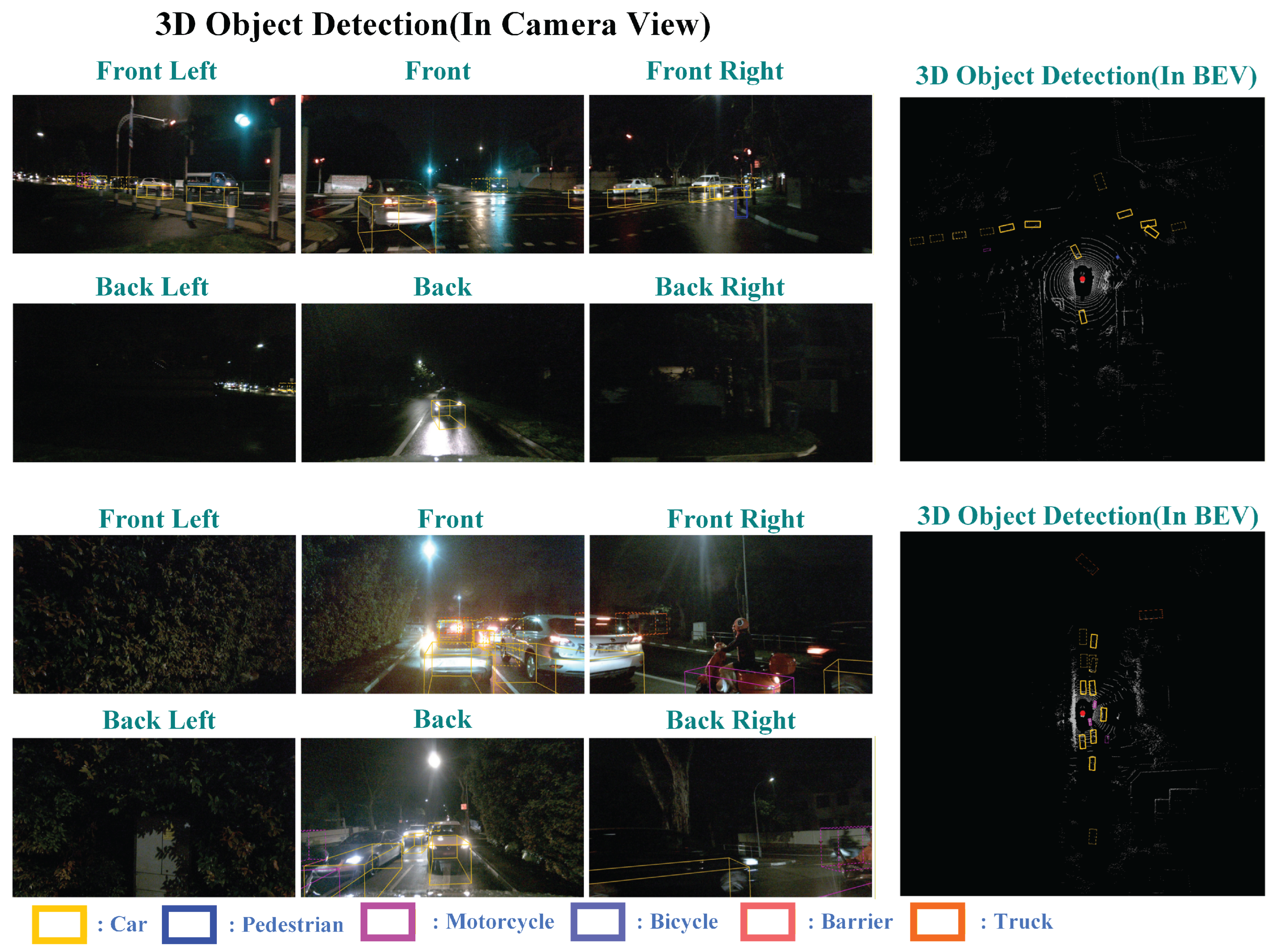

To further provide an intuitive analysis of the detection behavior and spatial modeling capability of the proposed method under complex night-time scenarios, this section presents qualitative visualizations and analyses of multi-modal 3D object detection results in representative nighttime scenes. The results are illustrated in

Figure 9.

Figure 9 shows multi-view camera images and the corresponding BEV-based 3D detection results under nighttime conditions. In the visualizations, solid 3D bounding boxes indicate successfully detected objects, while dashed bounding boxes denote missed targets under extremely challenging nighttime conditions.

From the camera-view images, it can be observed that nighttime scenes are generally affected by insufficient illumination, local strong light interference, and the small scale of distant objects. Under such conditions, certain targets, especially small or occluded objects at long distances, may still be missed, which is to some extent unavoidable in nighttime autonomous driving perception tasks.

Despite these challenges, the proposed model is able to stably detect major traffic participants, such as vehicles, pedestrians, and two-wheeled objects, across most viewpoints, while maintaining reasonable spatial layouts and object orientations in the BEV representation. Moreover, the missed detections do not cause noticeable disruption to the overall spatial modeling, indicating that the proposed method exhibits satisfactory detection stability and robustness in multi-modal fusion under complex nighttime environments.