1. Introduction

With the rapid development of cloud computing, artificial intelligence, and big data technologies, data centers, as the core infrastructure of the digital society, have experienced explosive growth in both scale and number. According to the International Energy Agency, global data center electricity consumption already accounts for approximately 1.8% of total power consumption, and this proportion continues to rise. In the overall energy consumption structure of data centers, cooling systems typically account for 40–50% of total power usage, making them the second-largest energy consumer after IT equipment. Meanwhile, server chip thermal design power has exceeded 700 W, and single-rack power density is steadily approaching 30 kW and beyond, pushing traditional air-cooling technologies toward bottlenecks such as insufficient cooling capacity and low energy efficiency.

From a thermal-system viewpoint, modern data centers exhibit pronounced spatiotemporal heterogeneity in airflow organization and heat transfer processes. The interaction among time-varying workloads, rack layout diversity, and constrained airflow paths often produces non-uniform temperature distributions and persistent local hotspots. Such thermal asymmetry accelerates component aging, degrades performance, and may even trigger safety shutdowns, threatening the stable operation of large-scale computing infrastructures. Under the strategic goals of carbon peak and carbon neutrality, achieving precise regulation, energy-efficient operation, and thermal-field uniformity in data center cooling systems has become a focal topic of common concern in academia and industry.

Extensive efforts have been devoted to data center thermal management. In temperature perception and prediction, Lin et al. compared the performance of six data-driven models under steady-state and transient scenarios in air-cooled data centers based on computational fluid dynamics simulation data, showing that the prediction root mean square error of XGBoost and LightGBM models can be controlled within 1.0 °C [

1]. Chen et al. used machine learning algorithms to construct rack hotspot temperature prediction models, enabling rapid temperature estimation under multi-parameter operating conditions such as server power, inlet air velocity, and inlet air temperature [

2]. In cooling control strategies, Yao and Shekhar systematically reviewed the application of model predictive control (MPC) in HVAC systems, indicating that MPC can balance energy consumption and thermal performance through rolling-horizon optimization [

3]. Wan et al. introduced deep reinforcement learning for rack-level cooling management, and their online learning approach adapts to dynamically changing thermal environments without offline pre-training [

4]. In novel cooling technologies, Heydari et al. investigated direct-to-chip liquid cooling for high-heat-density data centers, achieving efficient heat dissipation for thermal loads up to 128 kW using liquid-to-gas heat exchange units [

5]. Taddeo et al. analyzed the thermal behavior of single-phase immersion cooling systems through combined experiments and numerical simulations [

6]. Zhou et al. comparatively studied waste-heat recovery schemes that integrate immersion-cooled data centers with district heating and organic Rankine cycle systems [

7].

Despite these advances in temperature modeling, control optimization, and cooling technologies, several fundamental limitations remain. Existing monitoring schemes still rely predominantly on discretely deployed point-type sensors, which provide sparse spatial sampling and cannot capture the continuous structure of three-dimensional thermal fields, thereby obscuring fine-grained thermal asymmetry and evolving hotspot patterns. Moreover, many control methods depend strongly on model accuracy and exhibit limited robustness under load mutations, equipment degradation, or unexpected failures. These limitations motivate the development of a real-time thermal symmetry management framework that couples high-density distributed sensing with robust, constraint-aware predictive control for next-generation green data centers. Furthermore, a unified cyber–physical control architecture that explicitly models the symmetry of thermal fields and enforces spatiotemporal uniformity through closed-loop optimization remains largely unexplored in current data center cooling practice. From the perspective of large-scale cyber–physical infrastructure, system reliability, fault diagnosability, and structural robustness have long been recognized as fundamental requirements for safe and stable operation. Extensive theoretical studies on network connectivity, fault tolerance, and reliable diagnosis in complex topological systems have established solid foundations for designing resilient large-scale computing and control infrastructures [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. These studies provide important theoretical guidance for building high-availability and safety-critical industrial control systems such as modern data center cooling platforms.

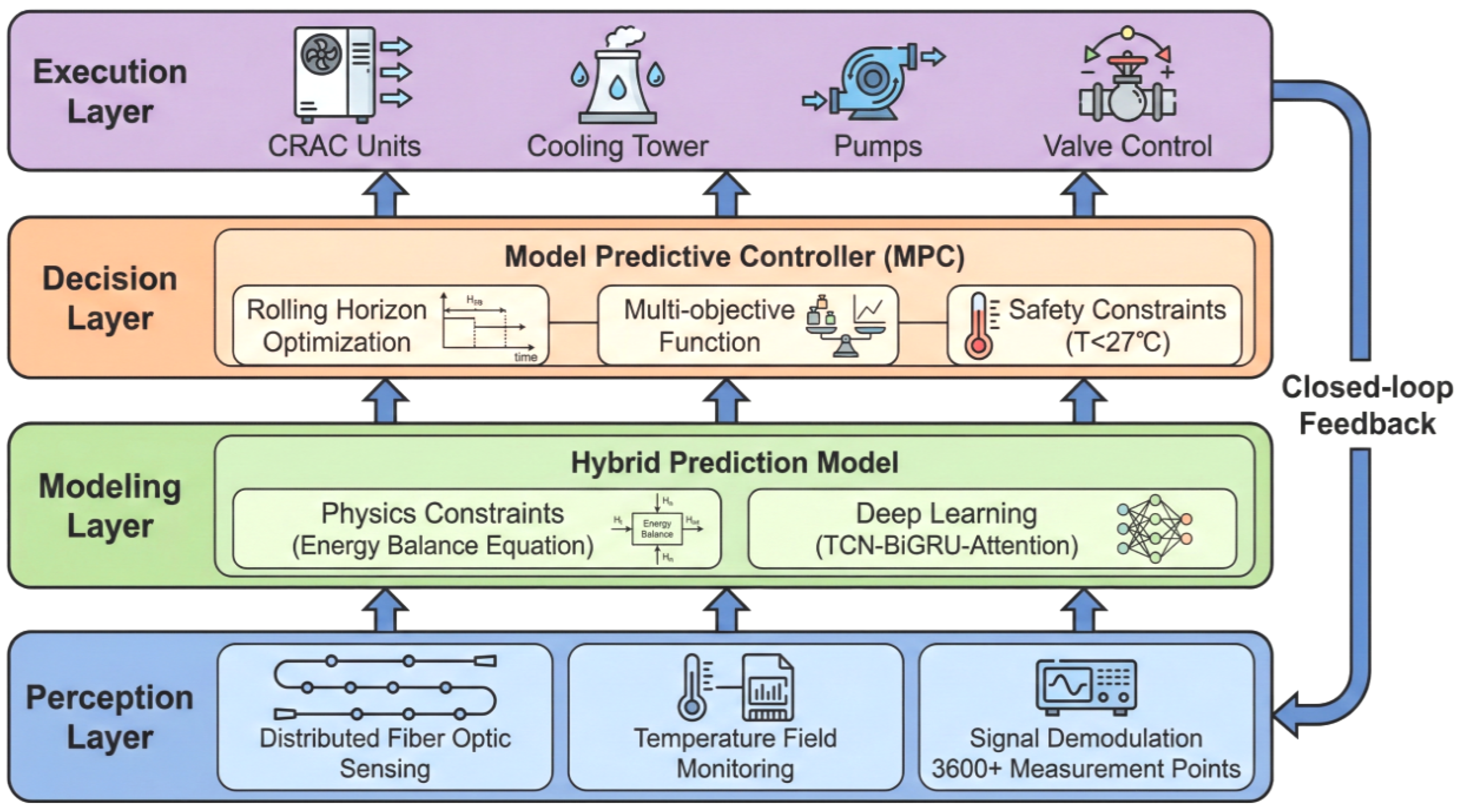

Addressing the shortcomings of existing research, this paper proposes a real-time thermal symmetry management framework for data centers based on distributed fiber optic temperature sensing and model predictive control. The overall research framework is illustrated in

Figure 1. The proposed system is organized into four tightly coupled layers, namely the perception layer, modeling layer, decision layer, and execution layer, forming a complete cyber–physical closed-loop control architecture.

The perception layer employs distributed fiber optic sensing technology to monitor the data center temperature field in real time. A single optical fiber simultaneously acquires temperature data from thousands of measurement points along its length, enabling high-density and continuous spatial sampling and providing fine-grained perception of the three-dimensional thermal field. The modeling layer integrates thermodynamic physical equations with deep neural networks to construct a hybrid prediction model that balances physical consistency, computational efficiency, and prediction accuracy. The decision layer designs a constraint-aware model predictive controller whose optimization objective is to minimize cooling energy consumption while suppressing thermal field deviations under explicit temperature safety boundaries. The optimal control sequence is solved through rolling-horizon optimization. The execution layer delivers control commands to precision air conditioners, cooling towers, and chilled water pumps, coordinating supply air temperature, airflow rate, and chilled water flow to regulate the thermal environment in real time.

The contributions of this work are threefold. First, distributed fiber optic sensing is introduced into data center thermal field monitoring, providing high-density and continuous temperature perception for fine-grained thermal symmetry management. Second, a hybrid physical–AI prediction model is developed by integrating thermodynamic mechanisms with data-driven learning, enhancing the representation capability for nonlinear thermal processes while preserving computational efficiency. Third, a multi-objective symmetry-aware MPC framework is designed to achieve the unified optimization of cooling energy consumption and thermal safety. The results of this study provide effective technical support and theoretical reference for intelligent operation, energy-efficient control, and low-carbon transformation of next-generation green data centers.

2. Related Technologies and Research Status

2.1. Overview of Data Center Thermal Management Technologies

Data center thermal management systems play a fundamental role in maintaining safe operating temperatures for IT equipment and ensuring the stable delivery of computing performance. Zhang et al. conducted a comprehensive technical review and classification of data center cooling systems, categorizing existing cooling solutions into three major classes, namely air cooling, liquid cooling, and natural cooling, and analyzing their applicable scenarios and development trends from the perspectives of power modeling and control strategy optimization [

14]. Their study indicates that although air cooling is technologically mature and offers relatively low deployment costs, its heat transfer capability is inherently constrained by the thermophysical properties of air, making it increasingly difficult to satisfy the heat dissipation demands of high-power-density racks.

Xu et al. further expanded the research scope of thermal management technologies by systematically comparing the energy consumption characteristics, heat dissipation capacity, and operation and maintenance complexity of air cooling, liquid cooling, and natural cooling modes [

15]. Their analysis shows that liquid cooling is gradually becoming the mainstream solution for high-performance computing scenarios due to its superior heat transfer efficiency and scalability.

It is worth noting that the thermal environment of modern data centers exhibits pronounced spatiotemporal heterogeneity. The combined effects of dynamic server workload fluctuations, spatial diversity in rack layouts, and complex airflow organization lead to frequent local hotspot formation and non-uniform temperature distributions. Du et al. addressed this challenge from the perspective of dynamic thermal environment management and comprehensively reviewed recent progress in real-time temperature monitoring, thermal load prediction, and adaptive control technologies, providing a theoretical foundation for the construction of intelligent and autonomous thermal management systems [

16].

2.2. Research Progress in Temperature Monitoring and Prediction Methods

Accurate temperature perception and reliable thermal load prediction constitute the fundamental basis for achieving efficient and adaptive thermal management in data centers. Traditional temperature monitoring schemes mainly rely on point-type sensors such as thermocouples and thermistors. Although these sensors provide fast response and high measurement accuracy, their deployment density is limited by wiring complexity and installation cost, resulting in sparse spatial sampling and an incomplete characterization of the three-dimensional thermal field within the machine room.

Distributed fiber optic temperature sensing technology provides a promising solution to overcome these limitations. Thévenaz systematically reviewed the operating principles and technical characteristics of distributed fiber optic sensors, demonstrating that temperature measurement systems based on Brillouin or Raman scattering can continuously acquire temperature information from thousands of points along a single optical fiber, achieving centimeter-level spatial resolution and temperature accuracy better than 0.5 °C [

17]. This capability enables high-density and long-distance thermal field monitoring, which is particularly advantageous for large-scale infrastructure environments. Hatley et al. applied high-resolution distributed temperature sensing to bridge scour monitoring and verified the reliability and robustness of this technology under complex environmental conditions, providing valuable engineering references for the design of data center temperature monitoring systems [

18].

In the field of temperature prediction, data-driven modeling has become the dominant technical paradigm. Athavale et al. systematically compared the performance of multiple machine learning methods, including artificial neural networks, support vector regression, and Gaussian process regression, for data center temperature prediction tasks [

19]. Their experimental results indicate that Gaussian process regression achieves the best average prediction error of 0.56 °C, while artificial neural networks and support vector regression also exhibit competitive performance with prediction errors of 0.60 °C and 0.68 °C, respectively. Fang et al. proposed a temperature prediction approach that integrates computational fluid dynamics simulation with deep neural networks [

20]. By incorporating attention mechanisms and Bayesian optimization, their method achieved an 81.48% improvement in prediction accuracy compared with conventional models, demonstrating the effectiveness of coupling physical simulation with data-driven learning. Lin et al. further summarized recent advances in thermal-aware modeling and energy-saving strategies for cloud data centers, organizing related research from the perspectives of thermal modeling, thermal-aware scheduling, and collaborative thermal management optimization [

21].

2.3. Research Progress in Cooling System Control Strategies

The optimization and control of cooling systems constitute a core component in reducing data center energy consumption and improving operational efficiency. Model predictive control (MPC), as an advanced process control paradigm, is particularly suitable for data center thermal regulation due to its ability to handle multivariable coupling, explicit constraint handling, and time-delay dynamics. By establishing a predictive model of the controlled system and solving an optimal control sequence over a rolling horizon, MPC enables proactive and coordinated regulation of complex cooling infrastructures. Zhao et al. designed a coordinated MPC-based control strategy for multi-chiller systems in data centers, in which future cooling loads and server room temperatures are predicted using long short-term memory (LSTM) networks, and chilled water flow rate and supply temperature are jointly optimized [

22]. Experimental results demonstrate that this strategy can significantly reduce overall cooling energy consumption while maintaining stable thermal conditions in the server room.

Beyond MPC-based approaches, deep reinforcement learning (DRL) has emerged as a powerful paradigm for data center cooling control under highly dynamic and uncertain operating environments. Zhang et al. comprehensively evaluated the strengths and limitations of DRL algorithms for dynamic thermal management in data centers from four dimensions, namely algorithms, tasks, system dynamics, and knowledge transfer [

23]. Their analysis indicates that actor–critic, off-policy, and model-based algorithms exhibit superior optimality, robustness, and transferability across diverse workloads and operating scenarios.

The rapid development of DRL has further expanded the methodological landscape of cooling control. Li et al. proposed an end-to-end cooling optimization framework based on deep reinforcement learning for green data centers [

24]. By training a deep deterministic policy gradient (DDPG) agent through extensive interaction with the EnergyPlus simulation platform, their method achieved near-optimal control policies and realized approximately 11% cooling cost savings compared with manually configured baseline strategies. Wang et al. introduced a physics-guided safe reinforcement learning framework that explicitly embeds temperature threshold constraints into the policy learning process while optimizing energy efficiency objectives, effectively mitigating the safety risks inherent in purely data-driven approaches [

25]. Lin et al. further designed a thermal prediction model that integrates temporal convolutional networks, bidirectional gated recurrent units, and attention mechanisms within a multi-objective optimization framework, and on this basis constructed a collaborative control architecture that balances cooling energy minimization and rack cooling index maximization, providing a practical reference for intelligent operation and maintenance of hybrid-cooled data centers [

26].

Despite these advances, most existing control strategies still rely on sparse temperature perception and lack an explicit mechanism for preserving thermal field uniformity and symmetry across the data center space. This motivates the development of a symmetry-aware predictive control framework that integrates high-density distributed sensing with physically consistent prediction models and constraint-aware optimization to achieve robust, energy-efficient, and spatially balanced thermal regulation.

3. System Design

3.1. Overall System Architecture Design

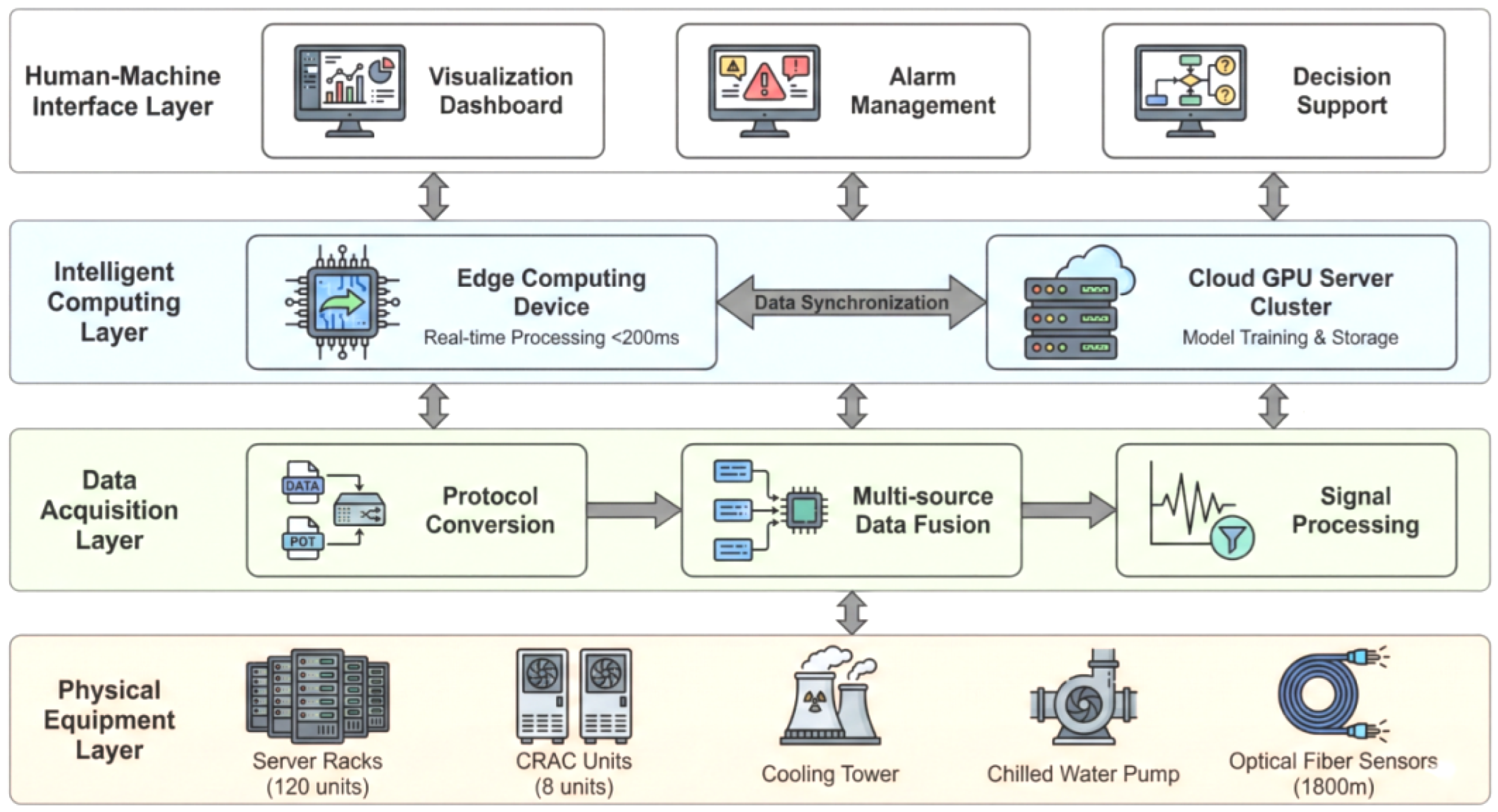

The data center thermal management system based on distributed fiber optic temperature sensing and model predictive control is designed to achieve high-precision perception of thermal fields, accurate prediction of thermal loads, and optimal regulation of cooling equipment. The overall system architecture follows a closed-loop cyber–physical control paradigm of perception–modeling–decision–execution, as illustrated in

Figure 2. This architecture is vertically organized into four functional layers.

The bottom layer is the physical equipment layer, which consists of server racks, precision air conditioners (CRAC units), cooling towers, chilled water pumps, and distributed fiber optic sensors. These components form the physical infrastructure that generates heat loads, executes cooling actions, and provides continuous temperature measurements. The second layer is the data acquisition layer, which is responsible for temperature signal demodulation, multi-source data fusion and aggregation, and communication protocol conversion to ensure reliable and low-latency data transmission. The third layer is the intelligent computing layer, which hosts the training and inference tasks of the hybrid thermal prediction model as well as the optimization solving tasks of the model predictive controller. The top layer is the human–machine interface layer, providing visualization dashboards, alarm management services, and operation and maintenance decision support for operators.

The hardware platform adopts an edge–cloud collaborative deployment mode. High-performance embedded computing devices are deployed at the edge side to execute temperature data preprocessing and fast control response tasks with stringent real-time requirements, while GPU server clusters are deployed at the cloud side to support offline training of deep learning models and large-scale historical data storage and analytics. Tanasiev et al. proposed an IoT-enhanced monitoring and control solution for HVAC systems that integrates heterogeneous devices through MQTT protocols and RESTful APIs, enabling real-time perception and remote management of equipment status via intelligent sensor nodes and edge computing applications [

27]. Inspired by this design philosophy, the proposed system constructs a hierarchical data acquisition and communication network for large-scale thermal sensing. Serale et al. further investigated IoT system architectures for MPC-based control and highlighted that well-designed communication topology and data synchronization mechanisms are essential for guaranteeing the real-time performance and stability of predictive control systems [

28]. The main design parameters of the proposed system are summarized in

Table 1.

3.2. Distributed Fiber Optic Temperature Sensing Subsystem Design

The distributed fiber optic temperature sensing subsystem constitutes the perceptual foundation of the proposed thermal symmetry management system. Its primary function is to acquire high-density spatiotemporal distribution information of the temperature field within the data center machine room, thereby enabling continuous and fine-grained observation of thermal dynamics. In contrast to traditional point-type temperature sensors, whose deployment density is constrained by wiring complexity and installation cost and thus provides only sparse discrete sampling, distributed fiber optic sensing enables continuous temperature profiling along the entire fiber path, making it possible to capture spatial temperature gradients and evolving hotspot structures under complex airflow environments.

Ashry et al. systematically reviewed the deployment of fiber-optic distributed sensing technologies in the oil and gas industry, covering Rayleigh-based distributed acoustic sensing (DAS), Raman-based distributed temperature sensing (DTS), and Brillouin-based distributed temperature and strain sensing (DTSS) [

29]. Their survey highlights that these sensing systems provide continuous real-time measurements along the full length of optical fiber cables and are particularly suitable for long-distance, large-scale monitoring applications. Lu et al. further presented a comprehensive review of distributed optical fiber sensors based on Rayleigh, Brillouin, and Raman scattering mechanisms, emphasizing their extensive applications in energy infrastructure monitoring, power generation systems, and pipeline inspection [

30]. Their study demonstrates the long-term stability, robustness, and reliability of distributed sensing technologies under complex operating conditions, together with diverse trade-offs in spatial resolution, sensing range, and temperature accuracy.

By leveraging these technical advantages, the proposed sensing subsystem establishes a high-resolution thermal perception layer for data centers, enabling continuous observation of three-dimensional thermal fields and providing a reliable data foundation for hybrid thermal modeling and symmetry-aware predictive control.

The proposed system adopts a distributed fiber optic temperature sensing scheme based on stimulated Brillouin scattering. When pulsed light propagates along an optical fiber, photons interact inelastically with acoustic phonons in the fiber medium, generating Brillouin backscattered light with a frequency shift. The Brillouin frequency shift exhibits a linear dependence on the local temperature of the fiber, which can be expressed as

where

denotes the Brillouin frequency shift at temperature

T (in GHz),

is the Brillouin frequency shift at the reference temperature

, and

represents the temperature sensitivity coefficient, which is typically approximately 1.1 MHz/°C for standard single-mode optical fibers. Here,

T denotes the measured temperature (in °C), and

is the reference temperature, commonly set to 25 °C.

Through spectral analysis and time-domain localization of the backscattered optical signals, both temperature values and spatial position information along the entire fiber can be obtained simultaneously. The spatial resolution of the sensing system is determined by the width of the probing optical pulses, while the temperature resolution depends primarily on the accuracy of spectral demodulation.

Barrias et al. reviewed the application status of distributed optical fiber sensors in civil engineering, demonstrating that although fiber Bragg grating (FBG) sensors offer high measurement accuracy, they essentially belong to quasi-distributed sensing schemes, in which the number of measurement points is limited by the number of gratings deployed along the fiber [

31]. In contrast, truly distributed sensing technologies based on Rayleigh, Brillouin, or Raman scattering provide continuous temperature measurements along the entire fiber length, enabling dense spatial sampling of large-scale infrastructures.

Bense et al. extensively reviewed the application of distributed temperature sensing (DTS) as a downhole monitoring tool in hydrogeology, demonstrating both passive and active DTS modes for a wide range of monitoring scenarios [

32]. Their work verifies the long-term stability, robustness, and environmental adaptability of distributed sensing systems in complex operating environments, providing valuable references for the technology selection and deployment strategies of temperature sensing systems in large-scale data center infrastructures.

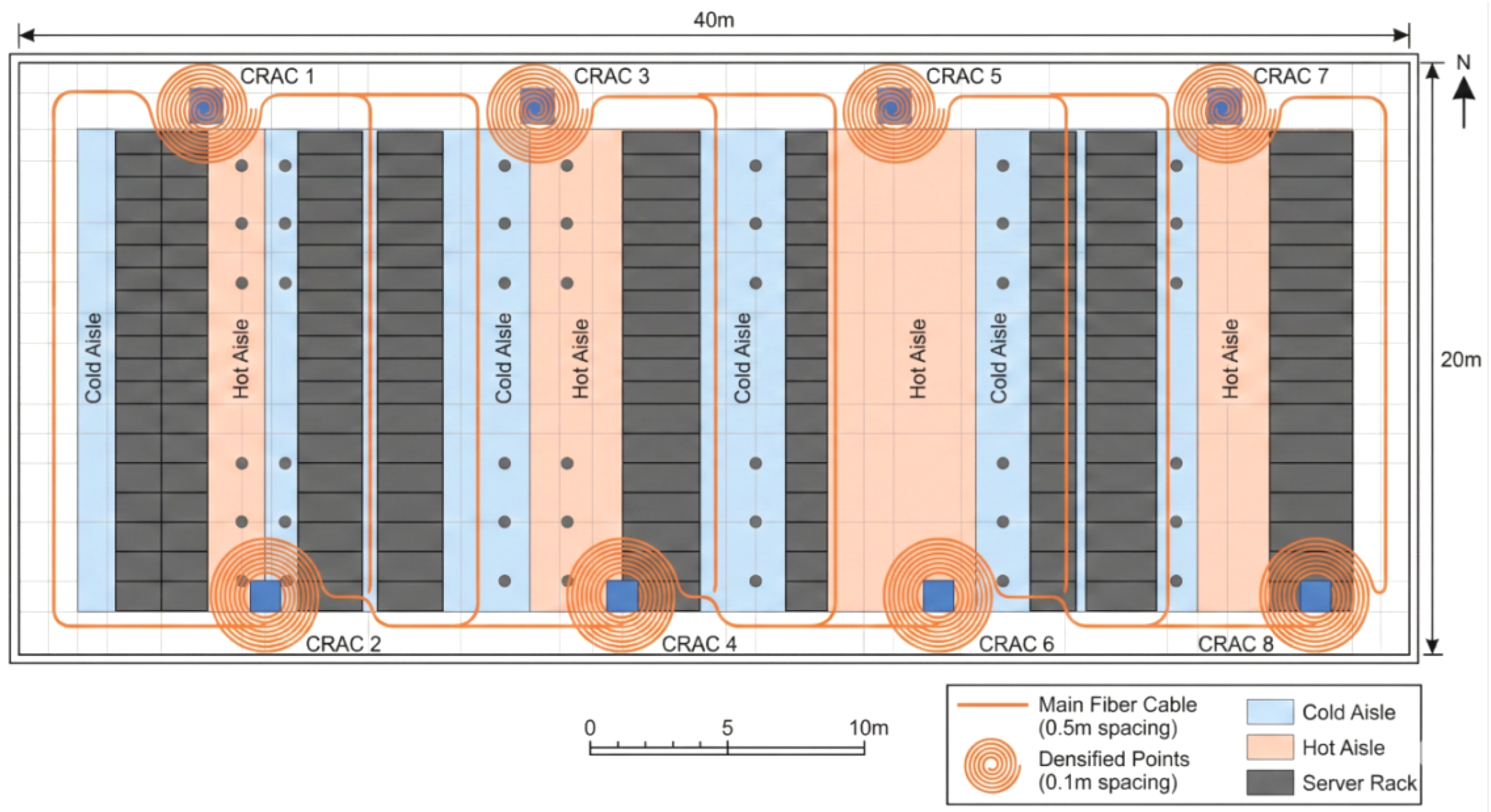

The spatial layout of the sensing fibers directly determines the observability, integrity, and reconstruction accuracy of the three-dimensional thermal field. To achieve uniform coverage while preserving fine-grained resolution in thermally critical regions, the proposed system adopts a hybrid deployment strategy that combines serpentine routing with hotspot-aware densification, as illustrated in

Figure 3. The main trunk cable is arranged in a serpentine pattern along the upper spaces of both cold and hot aisles, ensuring continuous coverage across all rack rows. In key heat-exchange locations, including precision air-conditioner outlets, rack inlet faces, and hot-aisle return regions, local sampling density is increased through fiber coiling and localized routing, enabling high-resolution observation of thermal gradients and transient hotspots. The detailed layout parameters and regional sampling strategies are summarized in

Table 2.

3.3. Hybrid Thermal Prediction Model Design

Accurate temperature prediction constitutes the fundamental prerequisite for the implementation of model predictive control in data center thermal management. Purely physics-based models exhibit strong interpretability and extrapolation capability; however, their formulation is often complex and computationally intensive, which limits their suitability for real-time control. In contrast, purely data-driven models are easy to train and efficient in inference, but their generalization ability is inherently constrained by the distribution range of training data and may degrade under unseen operating conditions.

To address these limitations, the proposed system develops a hybrid thermal prediction model that integrates thermodynamic physical equations with deep neural networks, achieving a balance between physical consistency, predictive accuracy, and computational efficiency. From the perspective of cloud computing energy efficiency optimization, Buyya et al. analyzed the application potential of data-driven methods in data center management and emphasized that hybrid modeling strategies can effectively overcome the intrinsic limitations of single-paradigm approaches [

33]. Buyya et al. further provided a comprehensive review of energy-efficiency innovations and next-generation cloud computing technologies, highlighting that the integration of physical models with data-driven learning has become a key methodological trend for intelligent and sustainable data center operation [

34].

Motivated by these insights, the proposed hybrid prediction framework is designed to leverage the structural prior and extrapolation capability of thermodynamic models while exploiting the nonlinear representation power of deep neural networks for complex thermal dynamics, thereby providing a robust and scalable foundation for symmetry-aware predictive control.

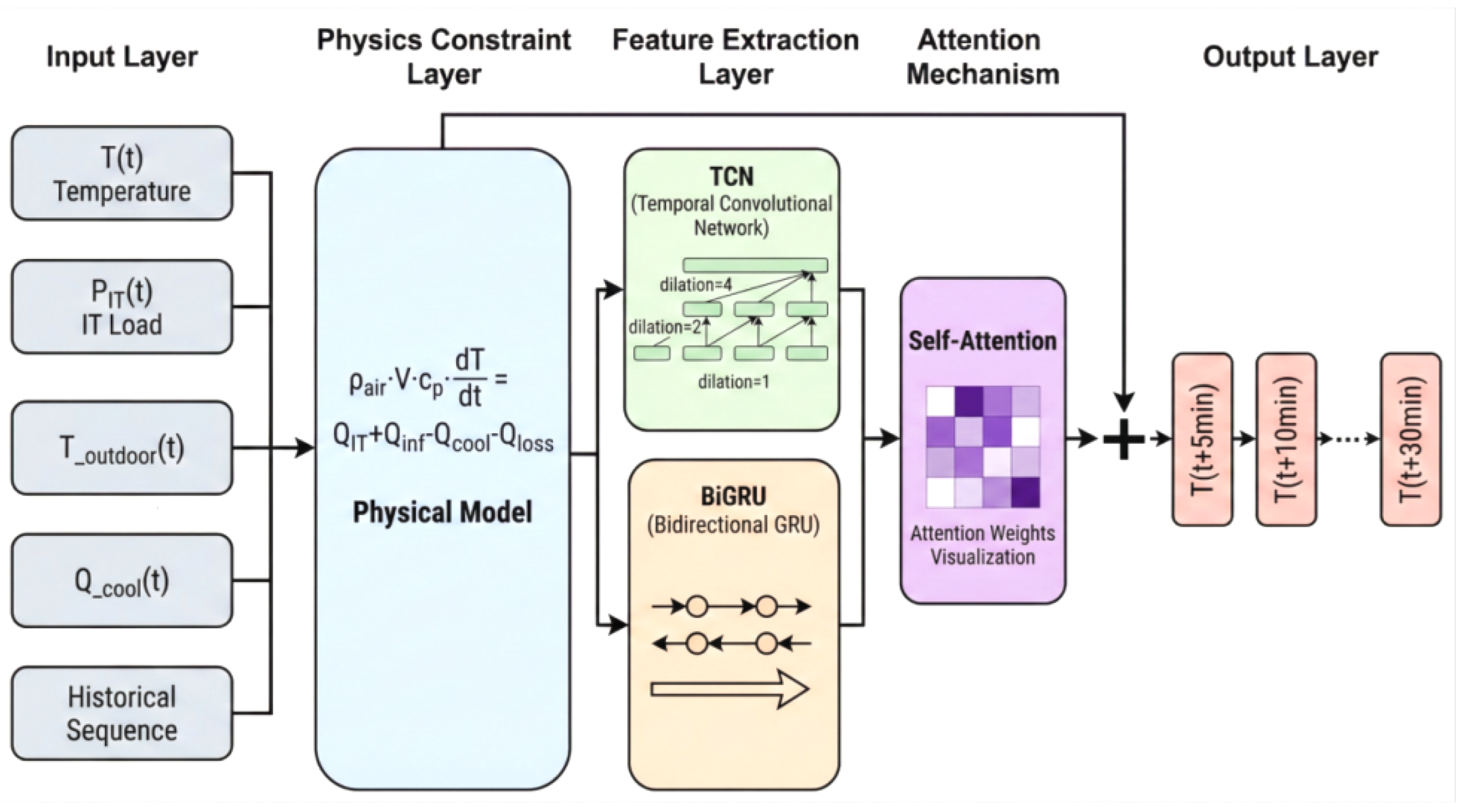

The overall architecture of the hybrid thermal prediction model is illustrated in

Figure 4. The model is composed of three tightly coupled components: a physical constraint layer, a feature extraction layer, and a prediction output layer. The physical constraint layer establishes macroscopic thermal balance equations for the data center machine room based on the principle of energy conservation, providing physically interpretable structural priors for the learning model.

Under steady-state operating conditions, the thermal balance of the machine room can be expressed as

where

denotes the total heat generation power of IT equipment (kW),

represents the heat gain introduced by envelope heat transfer and infiltration air (kW),

denotes the effective cooling capacity of the cooling system (kW), and

represents other heat dissipation losses (kW).

For dynamic operating conditions, considering the thermal storage effect of machine room air and equipment, the thermal balance equation can be extended as

where

denotes the air density (kg/m

3),

V is the effective machine room volume (m

3),

is the specific heat capacity of air at constant pressure (kJ/(kg

C)),

is the average machine room temperature (°C), and

t denotes time (s).

The formulation of the physical constraint layer is inspired by the fast fluid dynamics (FFD) modeling paradigm proposed by Han et al., who developed a data center thermal simulation model based on open-source fast fluid dynamics solvers [

35]. Their improved upwind scheme enables the coupled solution of advection and diffusion equations, achieving a favorable trade-off between computational efficiency and numerical accuracy. Compared with conventional CFD solvers requiring 464.8 h of computation time, the FFD model reduces simulation time to 7.6 h while preserving sufficient accuracy, and can achieve annual energy savings of 53.4–58.8% through optimal thermal design and operation.

In parallel, Athavale et al. systematically compared multiple data-driven thermal modeling approaches, including artificial neural networks, support vector regression, and Gaussian process regression for data center temperature prediction [

19]. Their experimental results indicate that Gaussian process regression achieves the best average prediction error of 0.56°C, providing a strong benchmark for validating the predictive accuracy of learning-based thermal models.

Motivated by these studies, the physical constraint layer in the proposed hybrid model encodes macroscopic thermodynamic principles into the learning framework, enabling the deep neural network to respect energy conservation laws while learning complex nonlinear thermal dynamics from data. This hybrid modeling strategy improves prediction robustness under dynamic workloads and unseen operating conditions, and establishes a physically consistent foundation for symmetry-aware model predictive control.

From a methodological standpoint, recent progress in deep learning-based signal modeling, time–frequency analysis, and optimization-inspired neural networks has provided powerful tools for constructing physically consistent and interpretable prediction models. A series of studies have demonstrated that combining signal processing theory, deep temporal networks, and optimization-driven learning architectures can significantly enhance prediction accuracy, stability, and interpretability in complex dynamic systems [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41]. These advances offer important methodological support for the proposed hybrid physical–AI thermal prediction framework.

3.3.1. Deep Feature Extraction Layer Based on TCN–BiGRU with Attention

The feature extraction layer adopts a cascaded architecture composed of a temporal convolutional network (TCN) and a bidirectional gated recurrent unit (BiGRU) to capture multi-scale temporal dependencies and long-range correlations in temperature sequences. The TCN module employs causal convolution and dilated convolution to achieve an exponentially expanding receptive field with limited network depth, enabling efficient modeling of long-term thermal evolution patterns.

The convolutional output of the TCN can be formulated as

where

denotes the hidden-state output of the

l-th layer at time

t,

is the convolution kernel weight matrix of layer

l,

represents the hidden-state sequence of layer

from time

to

t,

d denotes the dilation factor,

is the bias vector, and

denotes the nonlinear activation function.

On top of the TCN encoder, a BiGRU module is introduced to further enhance sequential representation capability by modeling bidirectional temporal dependencies. The BiGRU propagates information in both forward and backward directions, enabling the network to capture both historical thermal inertia and future trend consistency from the learned latent features. This cascaded TCN–BiGRU architecture effectively alleviates the vanishing gradient problem and achieves faster convergence compared with conventional LSTM-based recurrent networks.

The effectiveness of the TCN–BiGRU architecture for data center thermal prediction has been experimentally validated by Lin et al. [

26], who demonstrated its superior accuracy and training efficiency in multi-objective thermal optimization scenarios.

In the output stage, the learned deep features are fused with physical constraint priors through residual connections, enabling the model to generate multi-step temperature forecasts while respecting thermodynamic consistency. For input feature construction, domain knowledge from data center cooling systems is incorporated. Yu et al. [

42] systematically reviewed passive and active cooling strategies for data centers, providing guidance for selecting airflow, heat exchange, and equipment operation variables as thermal drivers. Perez-Lombard et al. [

43] further analyzed global building energy consumption patterns and identified HVAC systems as major energy consumers, accounting for approximately 50% of total building energy usage. These insights motivate the inclusion of HVAC-related operational variables as key explanatory features in the hybrid prediction model.

In a broader perspective of intelligent sensing systems, recent advances in high-throughput perception, deep learning-based recognition, and real-time intelligent decision-making have demonstrated the feasibility of constructing end-to-end closed-loop systems from sensors to insights. Representative studies have shown that modern industrial intelligence platforms increasingly rely on large-scale sensing, deep neural perception, and edge–cloud collaborative computing to support real-time control and optimization [

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49]. These developments further validate the technical paradigm adopted in this work, namely high-density sensing, intelligent modeling, and closed-loop optimization for complex industrial infrastructures.

The optimization objective of the MPC controller is formulated to minimize the total energy consumption of the cooling system over the prediction horizon while enforcing smooth control actions to avoid frequent equipment adjustments and mechanical wear. The objective function is defined as

where

J denotes the objective function value,

is the prediction horizon length,

is the control horizon length,

represents the cooling system power at step

k (kW),

denotes the predicted temperature vector at step

k,

is the reference temperature setpoint, and

denotes the control input increment at step

k. The weighting coefficients

,

, and

balance the trade-off among energy efficiency, thermal safety, and control smoothness.

The total cooling system power is decomposed into three major components: precision air conditioners, chilled water pumps, and cooling tower fans. The corresponding power model is given by

where

denotes the compressor power of precision air-conditioning units (kW),

represents the aggregated power of chilled water pumps and cooling water pumps (kW), and

denotes the cooling tower fan power (kW).

The formulation of the energy consumption model and airflow-related control variables is supported by experimental and field studies. Cho et al. performed measurements and predictive analysis of air distribution systems in high-compute-density data centers, revealing that reasonable airflow organization and cooling system configuration can significantly improve thermal management efficiency and reduce energy consumption [

50]. Lazic et al. from Google further demonstrated the practical effectiveness of model predictive control in large-scale production data centers, achieving substantial energy savings through real-world deployments [

51]. Their results provide strong empirical evidence for the effectiveness and engineering feasibility of MPC-based cooling optimization.

The constraint set of the MPC controller consists of two categories: temperature safety constraints and physical constraints of cooling equipment. The temperature safety constraints enforce that the predicted rack inlet temperature remains below a predefined upper bound to prevent server frequency throttling or emergency shutdown caused by overheating. The safety constraint is formulated as

where

denotes the predicted inlet temperature of rack

i at step

k,

represents the upper safety threshold of inlet temperature, and

denotes the total number of racks.

In addition to thermal safety, physical constraints of cooling equipment are imposed to ensure reliable and safe operation. These constraints limit both the admissible range and the rate of change of control variables, which are expressed as

and

where

denotes the control input vector at step

k, including the supply air temperature setpoint, airflow rate setting, and chilled water valve opening. The vectors

and

define the lower and upper bounds of the control variables, respectively, while

and

specify the allowable range of control input increments.

By explicitly embedding both thermal safety constraints and actuator physical limitations into the rolling-horizon optimization problem, the proposed MPC controller guarantees feasible and stable control actions under dynamic workloads and varying environmental conditions, thereby ensuring reliable and energy-efficient thermal regulation of the data center.

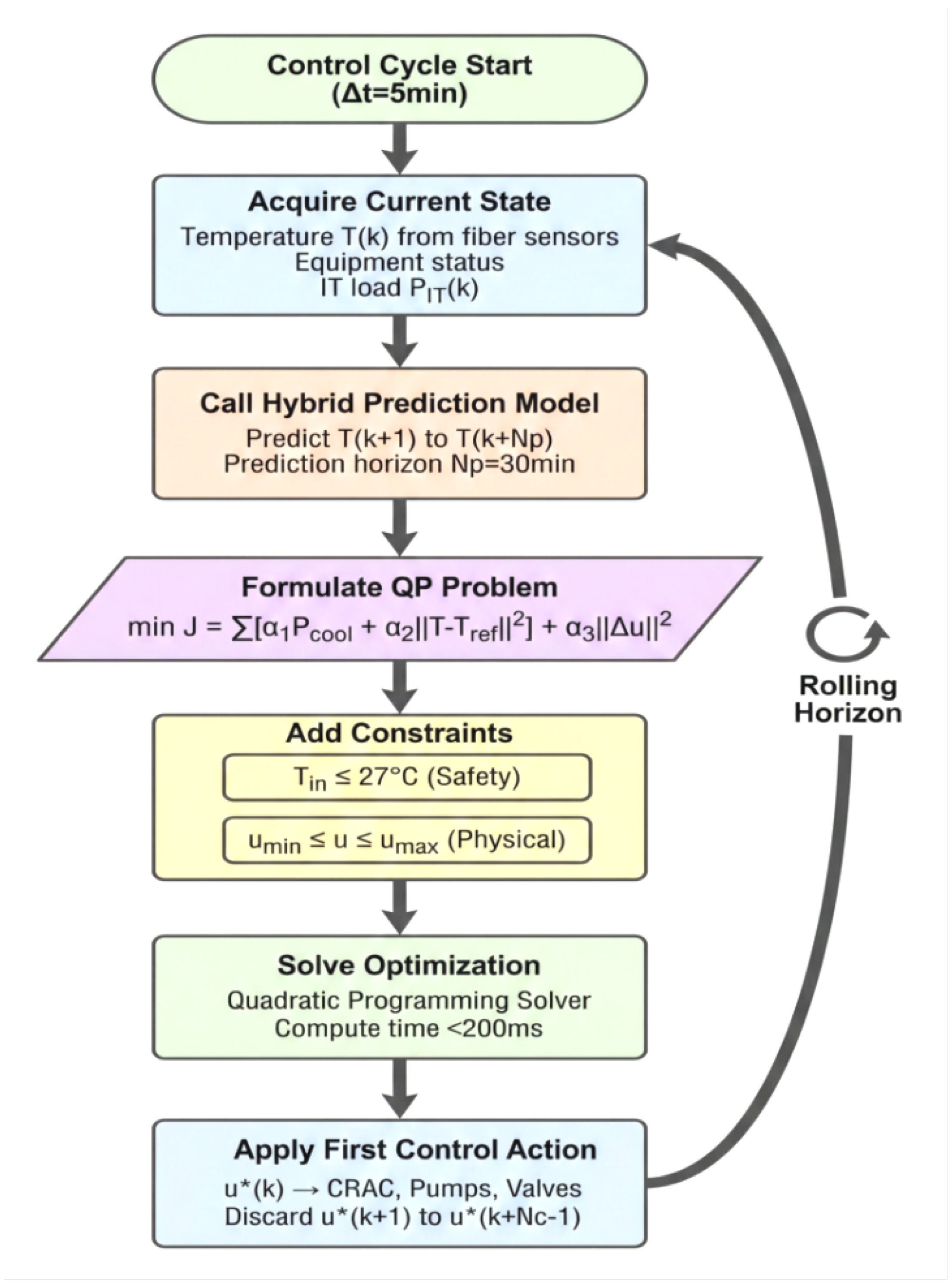

The solution process of the MPC controller is illustrated in

Figure 5. At each control cycle, the controller acquires real-time temperature measurements from the distributed fiber optic sensing system and collects operating status information of cooling equipment. The hybrid thermal prediction model is then invoked to generate multi-step temperature trajectories over the prediction horizon. Based on the predicted thermal evolution, the control problem is formulated as a constrained quadratic programming (QP) problem and solved to obtain the optimal control sequence. Finally, only the first control action in the sequence is applied to the actuators, and the entire optimization procedure is repeated at the next sampling instant following the rolling-horizon strategy.

Serale et al. provided a comprehensive review of model predictive control for enhancing the energy efficiency of buildings and HVAC systems, covering problem formulation, practical applications, and future opportunities [

28]. Their work highlights the importance of real-time optimization, reliable communication architectures, and human–machine interaction interfaces in large-scale energy systems, which offers valuable guidance for the control system implementation and operational interface design of the proposed data center thermal management platform.

By embedding real-time feedback and rolling optimization mechanisms into the control loop, the proposed MPC framework can effectively compensate for load disturbances, modeling uncertainties, and environmental fluctuations. This closed-loop predictive control architecture ensures safe, stable, and energy-efficient thermal regulation of the data center under dynamically varying operating conditions.

4. Experimental Results and Analysis

4.1. Experimental Environment and Testing Scheme

The experimental validation was conducted in a production data center operated by a large-scale Internet enterprise located in East China. The machine room covers an area of approximately 800 m2 and adopts an underfloor air supply and overhead return air airflow organization. The facility is equipped with 8 precision air-conditioning units and 120 standard 42U server racks. The racks are arranged in six rows following an alternating cold–hot aisle layout. The average power density per rack is approximately 12 kW, and the total IT load of the machine room is about 1.44 MW.

The experimental campaign was carried out from July to September 2024, covering representative summer operating conditions characterized by high ambient temperatures and heavy computational workloads. This period reflects typical peak-load scenarios for data center thermal management and therefore provides a realistic benchmark for evaluating the performance of the proposed control framework.

The distributed fiber optic temperature sensing system deployed approximately 1800 m of sensing fiber along the top of cold and hot aisles and key heat-exchange regions within the machine room. The system continuously collected temperature measurements from more than 3600 sensing points with a spatial resolution of 0.5 m. As a baseline reference, the original monitoring infrastructure of the data center consisted of 156 PT100 resistance temperature sensors installed at rack inlets and air-conditioner return air outlets.

The hybrid thermal prediction model was trained using historical operational data collected over the past 30 days, while the most recent 7 days of data were reserved for independent testing and validation. The MPC controller operated with a sensing sampling period of 10 s and a control update period of 5 min. The proposed control framework was evaluated against the original PID-based cooling control strategy deployed in the production system.

The detailed configuration of the experimental platform, sensing infrastructure, data volume, and control parameters is summarized in

Table 3.

4.2. Performance Analysis of the Distributed Temperature Sensing System

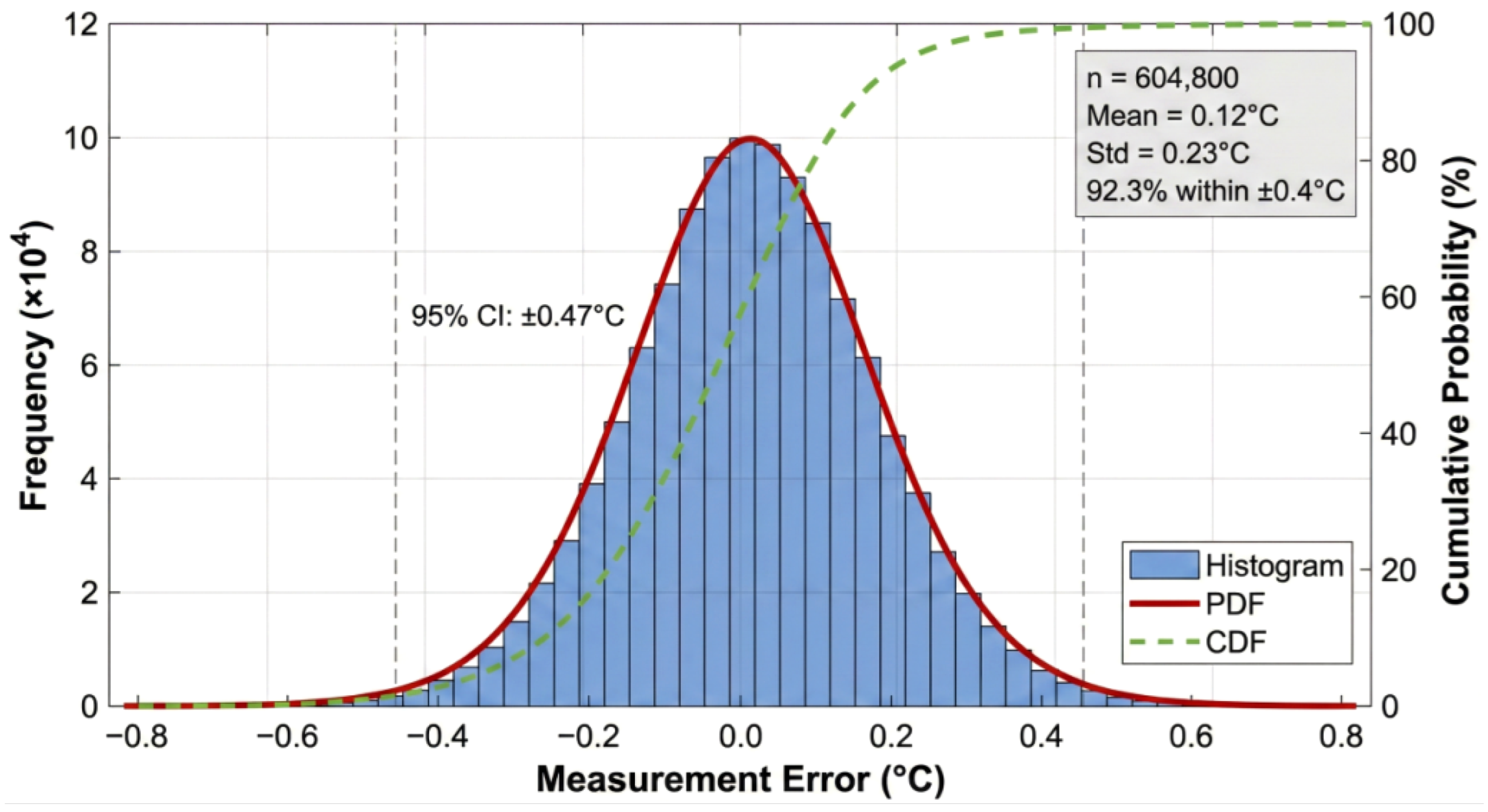

The performance of the distributed fiber optic temperature sensing system was evaluated from three dimensions: measurement accuracy, spatial resolution, and dynamic response characteristics. To assess measurement accuracy, the fiber optic sensing system was colocated with calibrated high-precision PT100 resistance temperature sensors, and the temperature readings from both systems were statistically compared.

During the 7-day continuous testing period, more than 600,000 paired measurement samples were collected under real operating conditions. The statistical results of the measurement errors are summarized in

Table 4. The distributed sensing system achieves an average measurement deviation of 0.12°C with a standard deviation of 0.23°C. The error range within the 95% confidence interval is

C, and within the 99% confidence interval is

C, which fully satisfies the accuracy requirements for data center thermal monitoring and control.

The probability density function (PDF) and cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the measurement errors are illustrated in

Figure 6. As shown in the figure, the error distribution closely follows a normal distribution with a mean value near zero, indicating the absence of significant systematic bias in the sensing system. Approximately 92.3% of the measurement points exhibit absolute errors within

C, and fewer than 1% of samples exceed an error magnitude of

C. These relatively large deviations are primarily observed in regions subject to strong airflow disturbances near precision air-conditioner outlets, where rapid temperature fluctuations and turbulent mixing increase local measurement uncertainty.

Overall, the experimental results demonstrate that the proposed distributed fiber optic sensing system provides high-accuracy, high-density, and spatially continuous temperature measurements, forming a reliable perceptual foundation for thermal field reconstruction and symmetry-aware predictive control in large-scale data centers.

The core advantage of the distributed sensing system over traditional point-type sensors lies in its capability to acquire continuous spatial temperature field information with high spatial resolution.

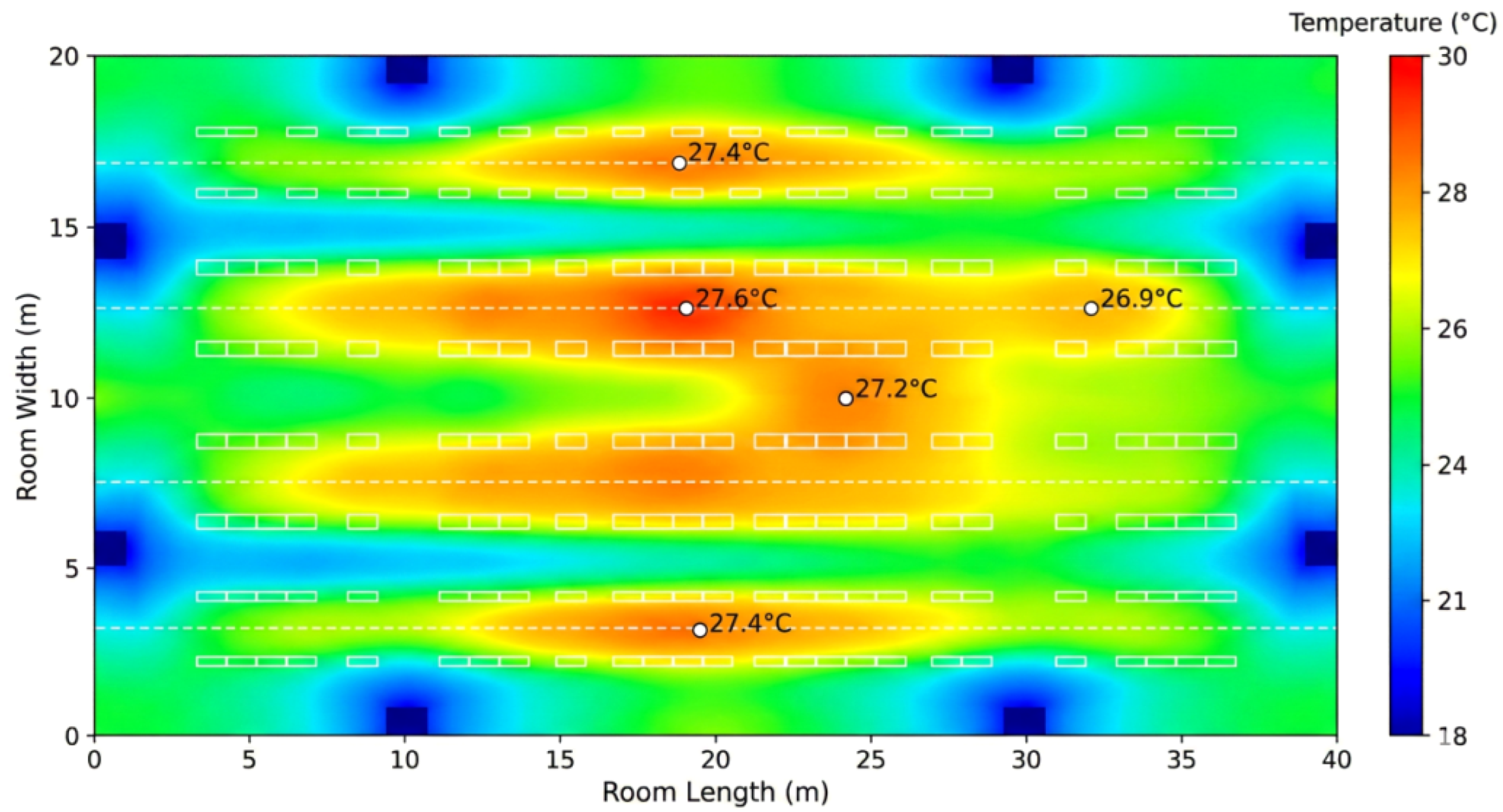

Figure 7 presents a two-dimensional thermal distribution map of the machine room temperature field at a representative operating moment. The horizontal axis corresponds to the spatial coordinate along the length direction of the machine room, while the vertical axis denotes the spatial coordinate along the width direction. The color scale represents the temperature magnitude.

From the thermal map, the band-shaped high-temperature distribution characteristics of hot aisle regions can be clearly observed, together with localized hotspot zones near individual rack outlets. These spatial thermal patterns reveal strong anisotropy and non-uniformity induced by rack layout, airflow organization, and dynamic IT load distribution. In contrast, the original monitoring system relying on only 156 discrete measurement points can merely provide sparse temperature sampling, which is insufficient to reconstruct such fine-grained spatial temperature gradients and to identify localized thermal anomalies in a timely and reliable manner.

4.3. Hybrid Thermal Prediction Model Accuracy Verification

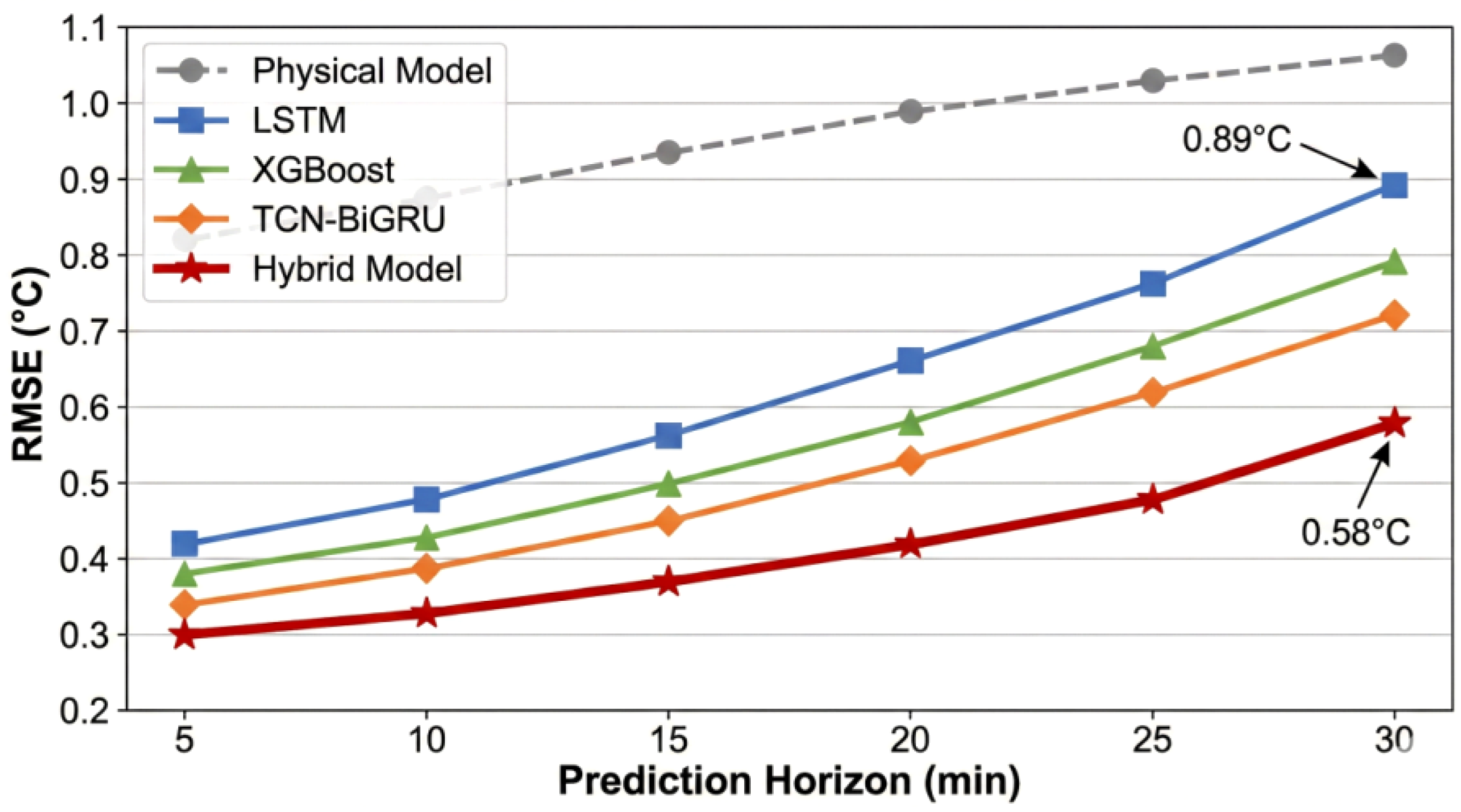

The prediction performance of the proposed hybrid thermal prediction model was evaluated through comparative experiments against several representative baseline methods. The comparison models include a traditional physical model based on macroscopic energy balance equations, a pure data-driven long short-term memory network (LSTM), the extreme gradient boosting algorithm (XGBoost), and a TCN–BiGRU network without physical constraint embedding. All models were optimized using the same training dataset, and their prediction accuracy was evaluated on an independent test dataset.

The prediction horizon was set to 30 minutes, and temperature values were predicted at six future time instants with a 5-minute interval. The performance comparison results are summarized in

Table 5. The evaluation metrics include root mean square error (RMSE), mean absolute error (MAE), mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), and the coefficient of determination (

).

The hybrid prediction model achieved the best performance across all evaluation metrics, with an RMSE of 0.41 °C, MAE of 0.32 °C, MAPE of 1.28%, and an value of 0.967. Compared with the pure physical model, the RMSE was reduced by 58.2%, demonstrating the significant improvement brought by data-driven feature learning. Compared with the best-performing pure data-driven model (XGBoost), the RMSE was further reduced by 26.8%, indicating that the introduction of physical constraints effectively enhances prediction stability and generalization capability.

These results verify that the proposed hybrid modeling strategy achieves a superior balance between physical consistency and nonlinear representation ability, providing reliable temperature trajectory prediction for downstream model predictive control and thermal symmetry regulation.

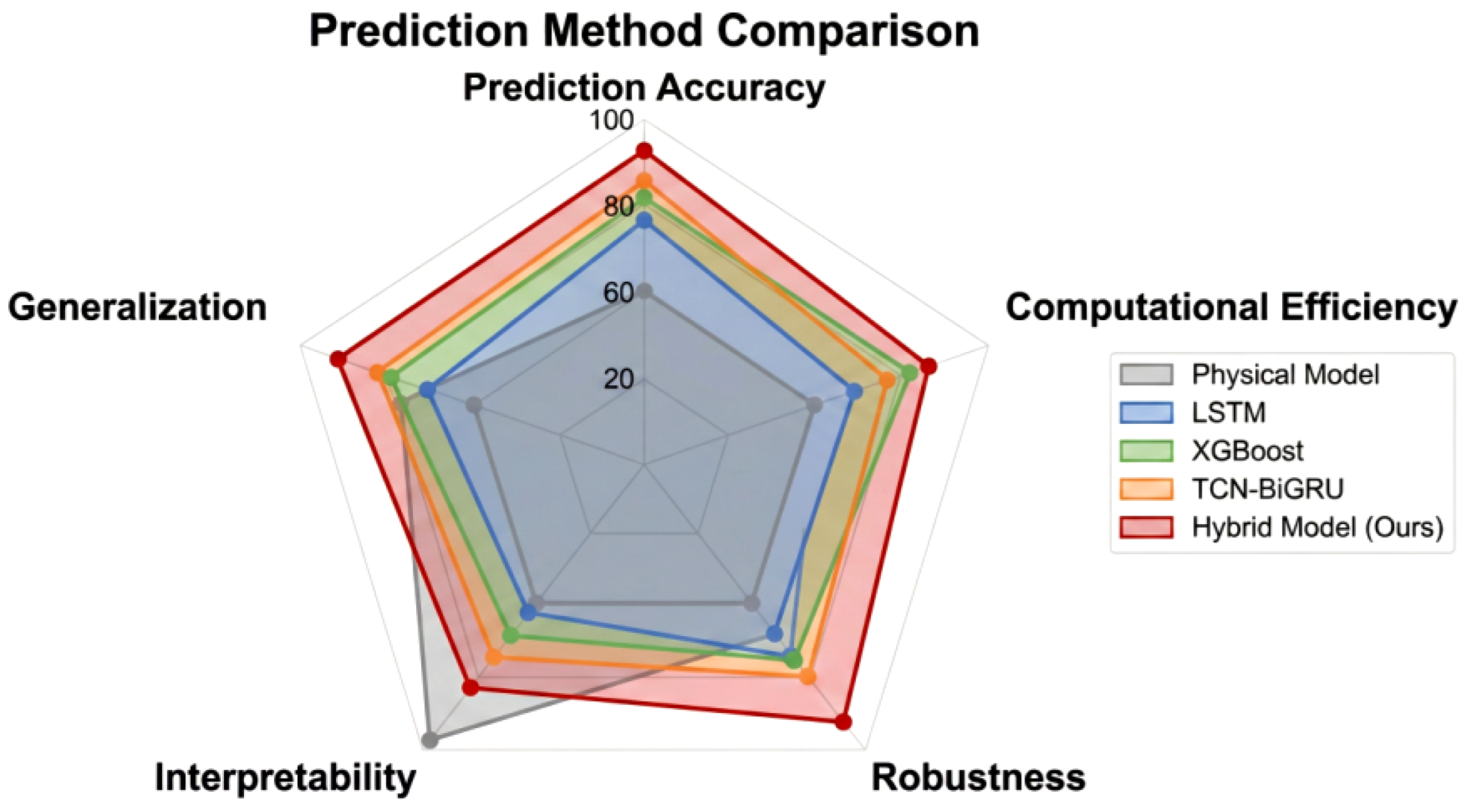

A comprehensive comparison of different prediction methods on multi-dimensional performance metrics is presented in radar-chart form in

Figure 8. The five dimensions correspond to prediction accuracy, computational efficiency, robustness, interpretability, and generalization ability, where larger values indicate better performance in the corresponding dimension. The proposed hybrid model exhibits clear advantages in prediction accuracy and generalization ability. Meanwhile, it maintains a favorable level of interpretability because the physical-constraint layer explicitly embeds thermodynamic conservation relationships, which regularizes the learned representations and improves model consistency.

The evolution of prediction error with an increasing prediction horizon reflects the long-term stability of forecasting models. In general, prediction errors tend to grow as the horizon extends due to uncertainty accumulation and compounding effects. The hybrid model shows a slower degradation trend under long-horizon forecasting, indicating that the introduction of physics-informed constraints can effectively suppress error accumulation and enhance stability for downstream predictive control.

4.4. MPC Control System Performance Evaluation

The performance of the proposed MPC-based thermal control system was evaluated through comparative experiments against the original PID control system. The two control strategies were alternately deployed under identical workload conditions and ambient environments. Each control system operated continuously for three days before switching to the other system. The evaluation metrics cover three aspects: temperature control accuracy, cooling system energy consumption, and equipment operation stability.

Temperature control accuracy is quantified using the statistical characteristics of rack inlet temperatures. All rack inlet temperature measurements were aggregated to compute the mean value, standard deviation, and over-limit ratio, defined as the time proportion exceeding the safety threshold of 27°C. The comparison results are summarized in

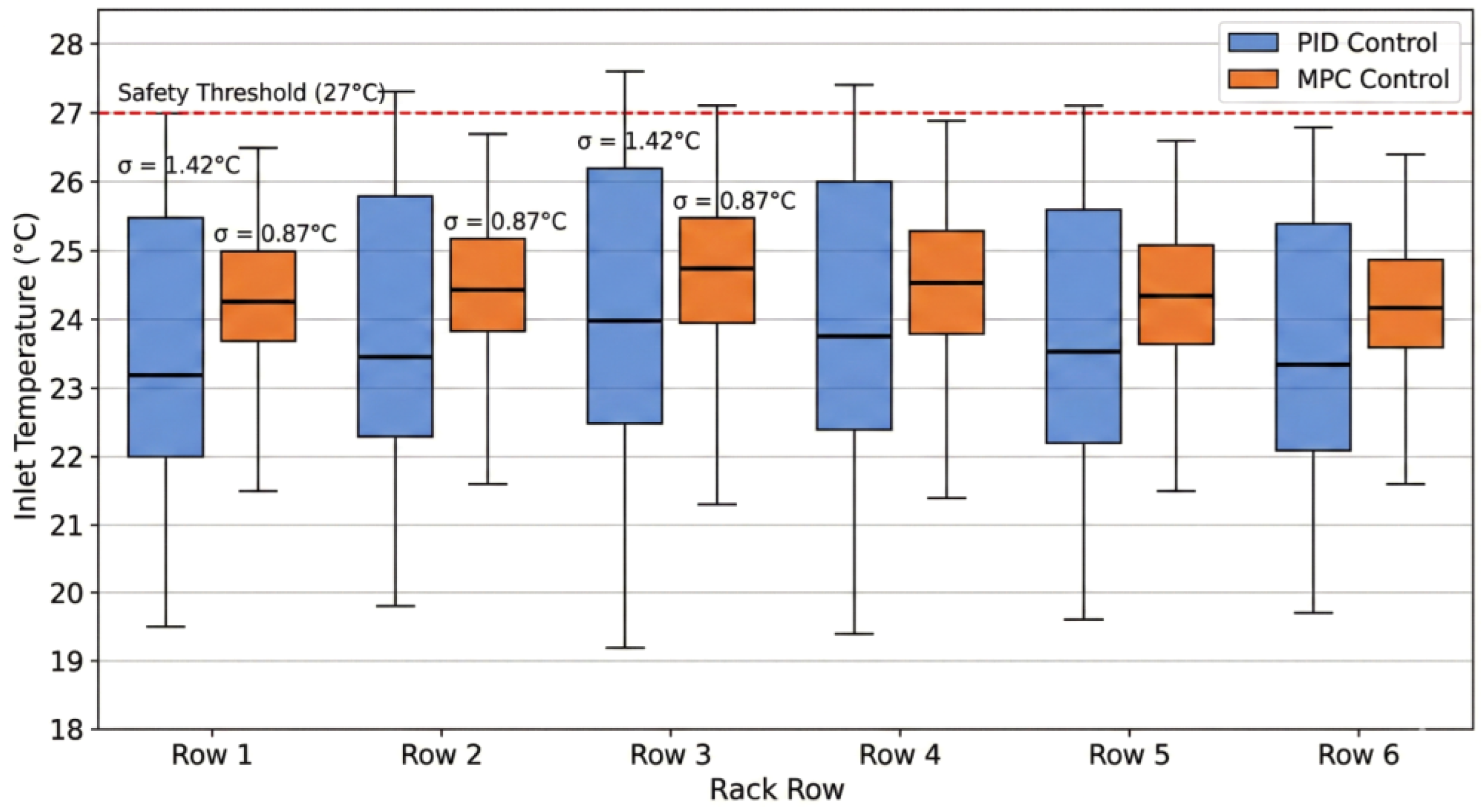

Table 6. Under MPC control, the mean rack inlet temperature increased from 23.8°C to 24.6°C, enabling more effective utilization of the allowable thermal margin while preserving safety constraints. Meanwhile, the standard deviation decreased from 1.42°C to 0.87°C, indicating a substantial improvement in spatial temperature uniformity. The over-limit ratio was reduced from 0.32% to 0.08%, corresponding to a 75% reduction in hotspot occurrence frequency.

The distribution characteristics of rack inlet temperatures are illustrated using box plots in

Figure 9. The left panels show the temperature distributions for each rack row under PID control, while the right panels correspond to the MPC control results. Each box represents the interquartile range, the central line denotes the median, whiskers extend to 1.5 times the interquartile range, and circular markers indicate outliers. It can be clearly observed that the temperature distributions under MPC control are significantly more concentrated and consistent across rack rows, demonstrating that both intra-row dispersion and inter-row thermal asymmetry are effectively suppressed.

Figure 9.

Comparison of rack inlet temperature distributions under PID control and MPC control across six rack rows. The dashed line indicates the safety threshold (27°C), and denotes the standard deviation within each row.

Figure 9.

Comparison of rack inlet temperature distributions under PID control and MPC control across six rack rows. The dashed line indicates the safety threshold (27°C), and denotes the standard deviation within each row.

Figure 10.

RMSE variation of different prediction models with respect to prediction horizon (5–30 min). The hybrid model exhibits the slowest error growth rate and maintains the lowest long-horizon prediction error.

Figure 10.

RMSE variation of different prediction models with respect to prediction horizon (5–30 min). The hybrid model exhibits the slowest error growth rate and maintains the lowest long-horizon prediction error.

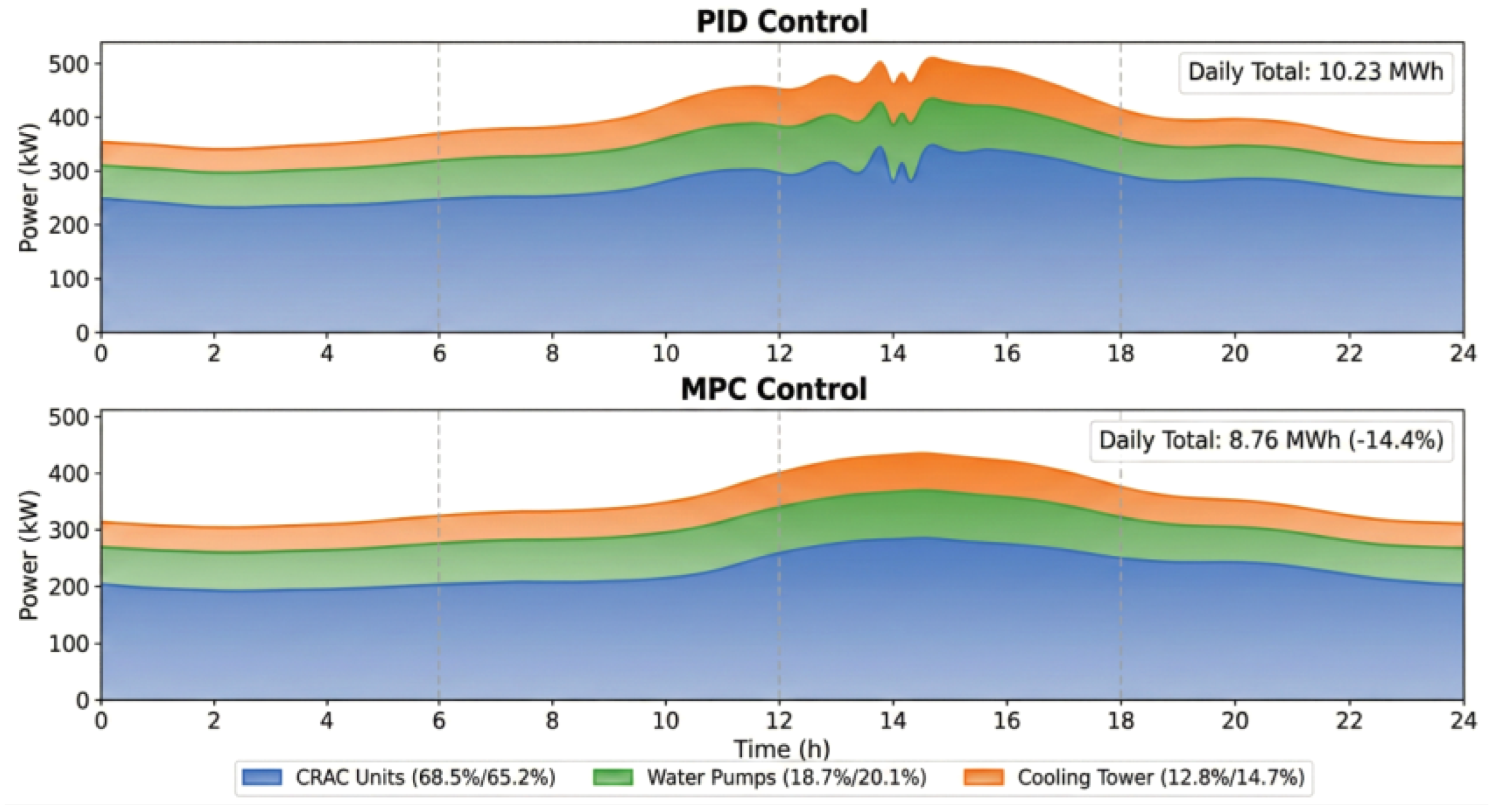

Cooling system energy consumption is a primary indicator for evaluating the economic effectiveness of thermal control strategies. During the experimental period, hourly power data of precision air conditioners (CRAC units), chilled water pumps, and cooling tower fans were recorded, based on which the total cooling energy consumption and power usage effectiveness (PUE) were calculated. The energy performance comparison between the PID and MPC strategies is summarized in

Table 7. The MPC system achieved a daily average cooling energy consumption of 8.76 MWh, corresponding to a 14.4% reduction compared with the PID system (10.23 MWh). Meanwhile, PUE decreased from 1.58 to 1.47 (a 6.96% reduction), indicating improved overall facility-level energy efficiency.

Based on an industrial and commercial electricity price of 0.85 yuan/kWh, the annual electricity cost savings are estimated to be approximately 460,000 yuan. Notably, the component-level energy distribution also changed under MPC control: the proportion of CRAC electricity consumption decreased (68.5% to 65.2%), while the shares of pumps and cooling tower fans slightly increased, suggesting that the MPC strategy reallocates energy use across subsystems to achieve a globally optimal operating point rather than locally minimizing a single device’s power.

Figure 11 illustrates the 24-hour temporal evolution of the cooling system power composition. The MPC strategy reduces compressor power during nighttime low-load periods, thereby better exploiting free-cooling potential and thermal inertia. During afternoon high-ambient-temperature periods, cooling capacity is increased in advance to mitigate upcoming thermal peaks, reflecting the feedforward and anticipative characteristics of predictive control. This anticipative regulation not only improves energy efficiency, but also contributes to stabilizing the thermal field and suppressing spatial thermal asymmetry by avoiding abrupt temperature excursions.

4.5. System Robustness and Extreme Condition Testing

In practical deployments, a data center thermal management system must remain stable under unexpected disturbances, including abrupt IT load mutations and equipment-level failures. Robustness testing was therefore conducted to verify system safety, stability, and recovery capability under extreme conditions. Test scenarios included a rapid IT load step (20% increase within 30 s), a single-CRAC shutdown (failure transfer), and sudden outdoor ambient temperature rises.

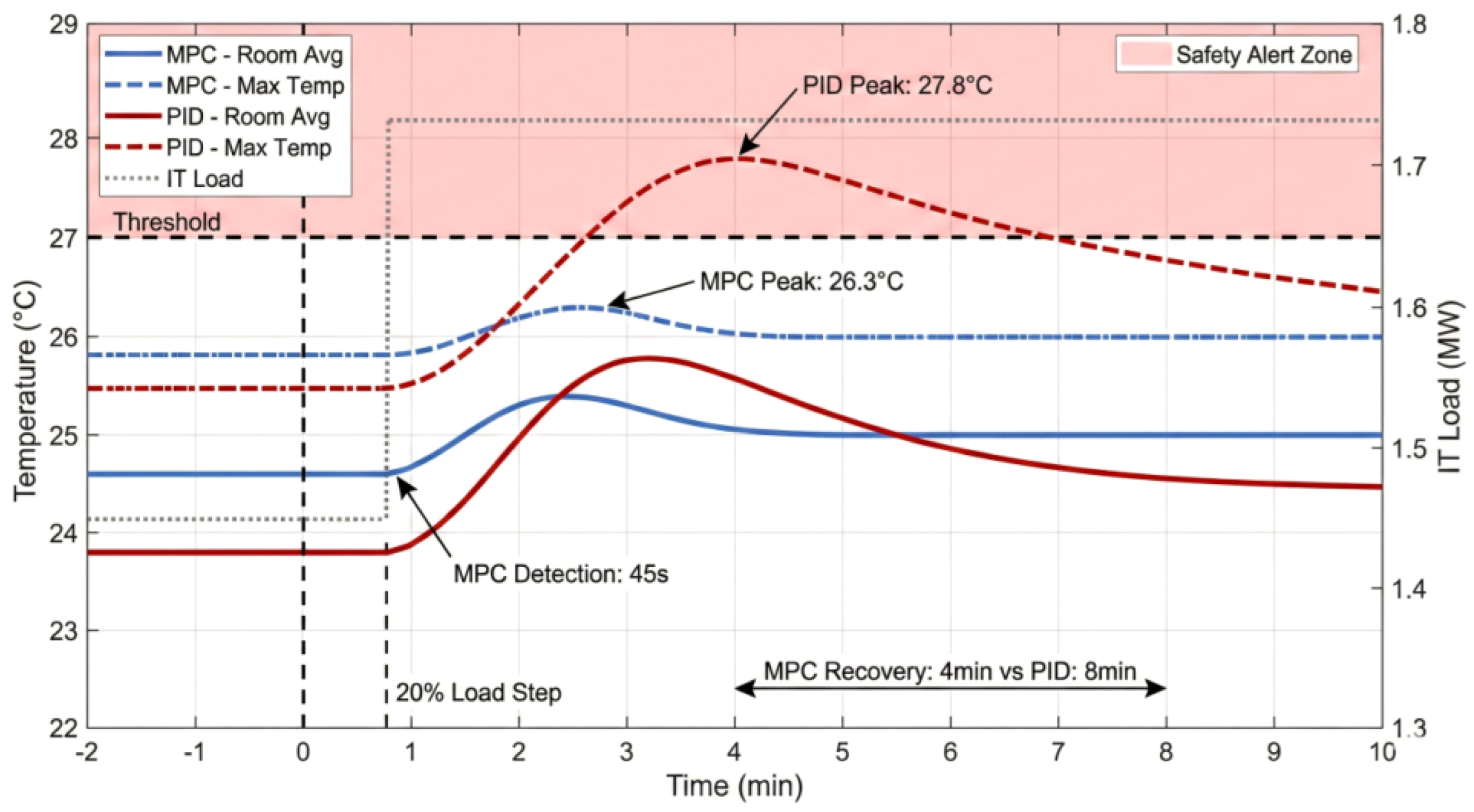

Figure 12 presents the temperature response trajectories in the load step test, including the room-average temperature, peak temperature, and the safety threshold (27 °C). After the load step occurred, the MPC strategy identified the abnormal thermal load change within 45 s and reduced the supply air temperature setpoint from 14.2 °C to 12.8 °C within the subsequent three control cycles. As a result, the maximum room temperature peaked at 26.3 °C at the 4th minute and then declined, without triggering the safety alert zone. Under the same test conditions, the PID controller exhibited a higher peak temperature of 27.8 °C and a recovery time exceeding 8 min. These results indicate that predictive regulation can suppress peak excursions and accelerate recovery, thereby maintaining thermal safety margins and mitigating transient thermal asymmetry amplification during disturbances.

Single air-conditioner failure testing simulated a sudden shutdown of CRAC No. 1 to evaluate load-transfer capability under coordinated MPC control. The MPC system detected the abnormal status within 15 s, recalculated the optimal operating parameters of the remaining CRAC units, and increased the air supply of adjacent CRAC No. 2 and No. 8 to 95% of rated capacity, while the other units synchronously increased output. The rack inlet temperature in the affected zone stabilized at 25.8 °C within 2 min, and no hotspot propagation was observed. The operating status of each unit before and after failure is summarized in

Table 8.

To further evaluate long-term operational robustness,

Table 9 reports the 90-day continuous operation statistics. The MPC system accumulated 2160 h of operation and handled 47 load mutation events and 12 ambient abnormal events, with all events maintained within safety thresholds (zero safety over-limit occurrences). The system availability reached 99.87%. Meanwhile, the controller achieved an average computation time of 127 ms and a maximum of 312 ms, with a 99.94% optimization success rate, satisfying real-time closed-loop control requirements in production environments.

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Discussion of Research Results

The distributed fiber optic temperature sensing system constructed in this study demonstrated excellent measurement performance in a production data center environment. The achieved accuracy level, with an average deviation of 0.12 °C and a standard deviation of 0.23 °C, is highly consistent with the theoretical performance indicators obtained under laboratory calibration conditions. This result verifies the reliability and long-term stability of Brillouin-scattering-based temperature measurement principles in industrial-grade application scenarios.

It is noteworthy that approximately 7.7% of measurement points exhibited deviations exceeding the expected range of 0.4 °C. Further spatial error distribution analysis reveals that these larger deviations are mainly concentrated in regions with strong turbulent airflow near precision air conditioner outlets. Intense airflow disturbances induce slight fiber vibrations, which affect the spectral stability of the backscattered signals. This observation reveals an inherent limitation of distributed fiber optic sensing technology under strong airflow interference conditions and indicates directions for future system optimization. Specifically, vibration-induced noise can be mitigated through improved fiber fixation strategies or by introducing advanced signal filtering and denoising algorithms.

The hybrid thermal prediction model achieved a substantial accuracy improvement compared to pure data-driven methods. The experimentally observed RMSE reduction of 26.8% relative to the XGBoost baseline confirms the effectiveness of introducing physical constraints into the learning framework. By embedding thermodynamic conservation equations as prior knowledge within the neural network architecture, the learning space of the model is effectively regularized, preventing abnormal prediction outputs that violate physical laws in sparsely sampled regions of the training dataset. This demonstrates that physics-guided learning provides a robust mechanism for improving long-horizon prediction stability in complex thermal systems.

The MPC-based control system achieved a 14.4% reduction in cooling energy consumption and improved PUE from 1.58 to 1.47. This performance level is comparable to that of internationally advanced hyperscale data centers, highlighting the technical superiority of predictive control strategies over traditional feedback-based control. From a control mechanism perspective, the energy savings are mainly derived from two aspects: (i) reducing excessive cooling by increasing the mean rack inlet temperature from 23.8 °C to 24.6 °C while maintaining safety margins; and (ii) leveraging predictive information to allocate cooling resources in advance, thereby avoiding efficiency losses caused by purely reactive control actions.

Moreover, the reduction of temperature standard deviation from 1.42 °C to 0.87 °C indicates that the MPC system achieves a more spatially balanced cooling distribution, which is of practical significance for mitigating local hotspots, enhancing thermal symmetry, and extending the service life of IT equipment. Nevertheless, it should be objectively recognized that the experimental validation period covered 90 days and mainly focused on summer high-temperature operating conditions. The system performance during spring–autumn transition seasons and winter low-temperature conditions still requires further verification, particularly with respect to the optimization potential of free cooling and hybrid cooling mode switching strategies.

5.2. Theoretical Contributions and Practical Implications

The theoretical contributions of this study can be summarized along three main dimensions.

First, from the perspective of sensing technology, distributed fiber optic temperature sensing is extended from traditional application domains such as power cable monitoring and oil and gas pipeline inspection to data center thermal management. The results verify the applicability of this technology in high-density measurement scenarios and complex airflow environments, providing a novel technical pathway for fine-grained and continuous characterization of data center temperature fields.

Second, from the modeling methodology perspective, a hybrid prediction architecture integrating thermodynamic physical equations with deep temporal neural networks is proposed. This architecture overcomes the dual limitations of pure physical models (high computational cost and modeling complexity) and pure data-driven models (limited generalization ability and physical inconsistency), thereby establishing a feasible framework for deep integration of physical knowledge and data intelligence in industrial process modeling.

Third, from the control strategy perspective, a multi-objective MPC controller tailored for data center cooling systems is designed. By explicitly incorporating temperature safety constraints and equipment operating boundaries, the controller achieves coordinated optimization of energy efficiency and thermal reliability, enriching the application practice of model predictive control in the HVAC domain.

From an engineering practice perspective, the proposed system demonstrates clear deployment value and promotion potential for data center operation and maintenance management. The deployment cost of the distributed fiber optic sensing system is approximately 60–70% of that of traditional point-sensor schemes with equivalent measurement point density, while offering advantages such as simplified wiring, convenient maintenance, and strong anti-electromagnetic interference capability. These characteristics make it particularly suitable for large-scale deployment in newly built or retrofitted data centers.

The hybrid prediction model and MPC controller are implemented in software form and can be integrated via upgrading existing building automation systems or deploying independent edge computing devices, requiring minimal modification to existing hardware infrastructure. Based on the verified 14.4% energy-saving ratio, a 10 MW-class data center can achieve approximately 4 million yuan in annual cooling electricity cost savings, corresponding to an investment payback period of 2–3 years, which demonstrates strong economic feasibility.

It should be emphasized that data centers differ in terms of room layout, cooling architecture, and load characteristics. Therefore, practical deployment of the proposed framework requires scenario-adaptive configuration, particularly in terms of training data collection for the hybrid prediction model and parameter tuning for the MPC controller, which necessitate professional technical support.

6. Conclusion

This research addressed the critical challenges of high energy consumption, uneven temperature distribution, and delayed response inherent in traditional data center cooling control systems. A real-time thermal management framework based on distributed fiber optic temperature sensing and model predictive control was proposed and implemented in a production-scale data center environment.

The distributed fiber optic temperature sensing subsystem adopts the Brillouin scattering temperature measurement principle and acquires continuous temperature data from more than 3600 measurement points deployed along 1800 meters of sensing fiber. The system achieved an average measurement deviation of 0.12 °C with a standard deviation of 0.23 °C, enabling full-field perception and fine-grained spatial characterization of the machine room temperature field. Compared with traditional point-type sensors, the proposed sensing architecture provides a continuous, high-resolution, and highly reliable thermal monitoring foundation for intelligent cooling control.

A hybrid thermal prediction model integrating thermodynamic energy balance equations with a TCN–BiGRU deep temporal network was constructed. By embedding physical constraints as prior knowledge into the learning architecture, the model achieved a root mean square error of 0.41 °C and a coefficient of determination of 0.967 under a 30-minute prediction horizon, corresponding to prediction accuracy improvements of 58.2% and 26.8% compared with pure physical models and pure data-driven models, respectively. These results demonstrate that physics-guided deep learning provides an effective paradigm for improving long-horizon thermal prediction accuracy and stability in complex industrial environments.

On the control layer, an MPC-based cooling optimization framework was developed, performing coordinated regulation of precision air conditioners, chilled water pumps, and cooling tower fans via rolling horizon optimization under explicit temperature safety constraints. Experimental results show that the proposed system reduced daily average cooling energy consumption by 14.4%, optimized PUE from 1.58 to 1.47, reduced rack inlet temperature standard deviation from 1.42 °C to 0.87 °C, and decreased the temperature over-limit ratio from 0.32% to 0.08%. The system further demonstrated strong robustness under extreme operating conditions such as load step disturbances and air conditioner failures, achieving 99.87% availability during 90 days of continuous operation.

Overall, the proposed framework establishes a complete closed-loop architecture of “high-resolution perception–physics-guided prediction–predictive optimal control” for data center thermal management. It provides a scalable, reliable, and economically viable solution for improving cooling energy efficiency and thermal safety in large-scale data centers, thereby offering strong technical support for green and low-carbon development of digital infrastructure.

Nevertheless, several limitations remain to be addressed in future work. First, experimental validation was mainly conducted under summer high-temperature conditions, and system performance across different seasonal operating modes, particularly under natural cooling and hybrid cooling strategies, requires further investigation. Second, the hybrid prediction model exhibits dependency on historical training data and may require retraining when significant changes occur in machine room layout or cooling system configuration. Third, the computational complexity of the MPC controller grows rapidly with increasing prediction horizon and control variable dimensionality, which may pose real-time challenges in ultra-large-scale data center deployments.

Future research directions will focus on introducing transfer learning to enhance model generalization across heterogeneous data centers, developing distributed and hierarchical optimization frameworks to improve real-time scalability, and integrating digital twin technologies to enable virtual commissioning and adaptive control strategy evolution. These efforts will further advance the intelligence, efficiency, and autonomy of next-generation data center thermal management systems.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are not publicly available due to confidentiality agreements with the industrial partner and security restrictions of the production data center. Aggregated statistics and experimental configurations are provided in the paper for reproducibility.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI) for English language proofreading and grammar refinement. The authors reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Lin, J.; Lin, W.; Lin, W.; Wang, J.; Jiang, H. Thermal prediction for air-cooled data center using data driven-based model. Applied Thermal Engineering 2022, 217, 119207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Tu, R.; Li, M.; Yang, X.; Jia, K. Hot spot temperature prediction and operating parameter estimation of racks in data center using machine learning algorithms based on simulation data. In Proceedings of the Building simulation. Springer, 2023, Vol. 16, pp. 2159–2176.

- Yao, Y.; Shekhar, D.K. State of the art review on model predictive control (MPC) in Heating Ventilation and Air-conditioning (HVAC) field. Building and Environment 2021, 200, 107952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Duan, Y.; Gui, X.; Liu, C.; Li, L.; Ma, Z. SafeCool: safe and energy-efficient cooling management in data centers with model-based reinforcement learning. IEEE Transactions on Emerging Topics in Computational Intelligence 2023, 7, 1621–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydari, A.; Gharaibeh, A.R.; Tradat, M.; Manaserh, Y.; Radmard, V.; Eslami, B.; Rodriguez, J.; Sammakia, B.; et al. Experimental evaluation of direct-to-chip cold plate liquid cooling for high-heat-density data centers. Applied Thermal Engineering 2024, 239, 122122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taddeo, P.; Romaní, J.; Summers, J.; Gustafsson, J.; Martorell, I.; Salom, J. Experimental and numerical analysis of the thermal behaviour of a single-phase immersion-cooled data centre. Applied Thermal Engineering 2023, 234, 121260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Xin, Z.; Tang, W.; Sheng, K.; Wu, Z. Comparative study for waste heat recovery in immersion cooling data centers with district heating and organic Rankine cycle (ORC). Applied Thermal Engineering 2024, 242, 122479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Lin, Y.; Wang, S. The connectivity and nature diagnosability of expanded k-ary n-cubes. RAIRO-Theoretical Informatics and Applications-Informatique Théorique et Applications 2017, 51, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Yang, W.; Guo, Y.; Wang, S. Conditional fault tolerance in a class of Cayley graphs. International Journal of Computer Mathematics 2016, 93, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Ren, Y.; Lin, Y.; Wang, S. The tightly super 3-extra connectivity and diagnosability of locally twisted cubes. American Journal of Computational Mathematics 2017, 7, 127–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, M. The strong connectivity of bubble-sort star graphs. The Computer Journal 2019, 62, 715–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Wang, M. Connectivity and matching preclusion for leaf-sort graphs. Journal of Interconnection Networks 2019, 19, 1940007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Xu, S.; Jiang, J.; Xiang, D.; Hsieh, S.Y. Global reliable diagnosis of networks based on Self-Comparative Diagnosis Model and g-good-neighbor property. Journal of Computer and System Sciences 2025, p. 103698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Meng, Z.; Hong, X.; Zhan, Y.; Liu, J.; Dong, J.; Bai, T.; Niu, J.; Deen, M.J. A survey on data center cooling systems: Technology, power consumption modeling and control strategy optimization. Journal of Systems Architecture 2021, 119, 102253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z. Thermal management and energy consumption in air, liquid, and free cooling systems for data centers: A review. Energies 2023, 16, 1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Yang, X.; Yang, X.; Wang, C.; Liu, J.; Yuan, J. Dynamic thermal environment management technologies for data center: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2023, 187, 113761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thévenaz, L. Distributed Optical Fiber Sensors: Principles and Applications. Frontiers in Sensors 2025, 6, 1567051. [Google Scholar]

- Hatley, R.; Shehata, M.; Sayde, C.; Castro-Bolinaga, C. High-resolution monitoring of scour using a novel fiber-optic distributed temperature sensing device: A proof-of-concept laboratory study. Sensors 2023, 23, 3758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athavale, J.; Yoda, M.; Joshi, Y. Comparison of data driven modeling approaches for temperature prediction in data centers. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 2019, 135, 1039–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Xu, Q.; Li, S.; Xia, Y.; Chen, Q. Temperature prediction in data center combining with deep neural network. Applied Thermal Engineering 2024, 244, 122571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Lin, W.; Huang, H.; Lin, W.; Li, K. Thermal modeling and thermal-aware energy saving methods for cloud data centers: A review. IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Computing 2023, 9, 571–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Chen, Z.; Li, H.; Liu, D. A model predictive control for a multi-chiller system in data center considering whole system energy conservation. Energy and Buildings 2024, 324, 114919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zeng, W.; Lin, Q.; Chng, C.B.; Chui, C.K.; Lee, P.S. Deep reinforcement learning towards real-world dynamic thermal management of data centers. Applied Energy 2023, 333, 120561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wen, Y.; Tao, D.; Guan, K. Transforming cooling optimization for green data center via deep reinforcement learning. IEEE transactions on cybernetics 2019, 50, 2002–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Cao, Z.; Zhou, X.; Wen, Y.; Tan, R. Green data center cooling control via physics-guided safe reinforcement learning. ACM Transactions on Cyber-Physical Systems 2024, 8, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Lin, W.; Lin, W.; Liu, T.; Wang, J.; Jiang, H. Multi-objective cooling control optimization for air-liquid cooled data centers using TCN-BiGRU-Attention-based thermal prediction models. In Proceedings of the Building simulation. Springer, 2024, Vol. 17, pp. 2145–2161. [CrossRef]

- Tanasiev, V.; Pluteanu; Necula, H.; Pătrașcu, R. Enhancing monitoring and control of an HVAC system through IoT. Energies 2022, 15, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serale, G.; Fiorentini, M.; Capozzoli, A.; Bernardini, D.; Bemporad, A. Model predictive control (MPC) for enhancing building and HVAC system energy efficiency: Problem formulation, applications and opportunities. Energies 2018, 11, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashry, I.; Mao, Y.; Wang, B.; Hveding, F.; Bukhamsin, A.Y.; Ng, T.K.; Ooi, B.S. A review of distributed fiber–optic sensing in the oil and gas industry. Journal of Lightwave Technology 2022, 40, 1407–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Lalam, N.; Badar, M.; Liu, B.; Chorpening, B.T.; Buric, M.P.; Ohodnicki, P.R. Distributed optical fiber sensing: Review and perspective. Applied physics reviews 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrias, A.; Casas, J.R.; Villalba, S. A review of distributed optical fiber sensors for civil engineering applications. Sensors 2016, 16, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bense, V.; Read, T.; Bour, O.; Le Borgne, T.; Coleman, T.; Krause, S.; Chalari, A.; Mondanos, M.; Ciocca, F.; Selker, J. Distributed T emperature S ensing as a downhole tool in hydrogeology. Water Resources Research 2016, 52, 9259–9273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyya, R.; Ilager, S.; Arroba, P. Energy-Efficiency and Sustainability in Cloud Computing: Innovations, Methods and Research Directions. Software: Practice and Experience 2024, 54, 862–890. [Google Scholar]

- Buyya, R.; Ilager, S.; Arroba, P. Energy-Efficiency and Sustainability in New Generation Cloud Computing: A Vision and Directions for Integrated Management of Data Centre Resources and Workloads. Software: Practice and Experience 2024, 54, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Tian, W.; VanGilder, J.; Zuo, W.; Faulkner, C. An open source fast fluid dynamics model for data center thermal management. Energy and Buildings 2021, 230, 110599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, P.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, Z.; Qi, W. Deep learning-based 2-D frequency estimation of multiple sinusoidals. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2021, 33, 5429–5440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, P.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, Z.; Wu, G. Complex-valued frequency estimation network and its applications to superresolution of radar range profiles. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2021, 60, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, P.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, Z.; Fan, S.; Huang, X. TFA-Net: A deep learning-based time-frequency analysis tool. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2022, 34, 9274–9286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Pan, P.; Li, Y.; Guo, R. Efficient off-grid frequency estimation via ADMM with residual shrinkage and learning enhancement. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2025, 224, 112200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, P.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Ye, Y.; He, W.; Zhu, Y.; Guo, R. Interpretable Optimization-Inspired Deep Network for Off-Grid Frequency Estimation. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.; Wang, M.; Xu, L.; Zhang, F. The maximum forcing number of a polyomino. Australas. J. Combin 2017, 69, 306–314. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Z.J.; Haghighat, F.; Fung, B.C. Advances and challenges in building engineering and data mining applications for energy-efficient communities. Sustainable Cities and Society 2016, 25, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Lombard, L.; Ortiz, J.; Pout, C. A review on buildings energy consumption information. Energy and buildings 2008, 40, 394–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.F.; Qu, H.R.; Su, W.H. From sensors to insights: Technological trends in image-based high-throughput plant phenotyping. Smart Agricultural Technology 2025, p. 101257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.F.; Su, W.H. The application of deep learning in the whole potato production Chain: A Comprehensive review. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.F.; Qin, Y.M.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Xu, M.; Schardong, I.B.; Cui, K. RA-CottNet: A Real-Time High-Precision Deep Learning Model for Cotton Boll and Flower Recognition. AI 2025, 6, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Xi, X.; Wu, A.Q.; Wang, R.F. ToRLNet: A Lightweight Deep Learning Model for Tomato Detection and Quality Assessment Across Ripeness Stages. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huihui, S.; Rui-Feng, W. BMDNet-YOLO: A Lightweight and Robust Model for High-Precision Real-Time Recognition of Blueberry Maturity. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1202. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.F.; Tu, Y.H.; Li, X.C.; Chen, Z.Q.; Zhao, C.T.; Yang, C.; Su, W.H. An Intelligent Robot Based on Optimized YOLOv11l for Weed Control in Lettuce. In Proceedings of the 2025 ASABE Annual International Meeting. American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers, 2025, p. 1.

- Cho, J.; Lim, T.; Kim, B.S. Measurements and predictions of the air distribution systems in high compute density (Internet) data centers. Energy and buildings 2009, 41, 1107–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazic, N.; Boutilier, C.; Lu, T.; Wong, E.; Roy, B.; Ryu, M.; Imwalle, G. Data center cooling using model-predictive control. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2018, 31. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.