1. Introduction

Vestibular schwannomas (VS) are slow-growing benign tumors originating from Schwann cells, the myelin producing cells of the vestibular nerve sheath [

1,

2,

3]. VS most commonly arise within the internal auditory canal or cerebellopontine angle and only rarely extend into the labyrinthine space [

4,

5]. The existence, frequency and degree of the symptoms may vary greatly due to the tumor's heterogenic growth characteristics, size, and location. Due to compression of the VS, the eight cranial nerve may be damaged, leading to the most common symptoms such as sensorineural hearing loss, vertigo, tinnitus, aural fullness, and disequilibrium [

6]. Other mass effect symptoms may arise due to compression of other involved neural structures, such as the cerebellum, facial nerve, and trigeminal nerve [

7]. In accordance with symptoms, studies also stated that audiological and vestibular test results can be various as mainly depending on the tumor type, location or size [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13].

In the clinical practice, because VS tumors generally grow slowly, patients rarely suffer from acute symptoms. Hearing loss, tinnitus, a feeling of fullness in the ear, and/or headaches are the most common clinical symptoms that may indicate the presence of a VS [

14]. The gradual progression allows the central vestibular system to develop an adaptation mechanism that decreases the VS-related symptoms' effect on daily life, which in consequence, has relatively less impact on quality of life (QoL) of VS patients [

13]. Nevertheless, Kjærsgaard et al [

15] reported that a loss of more than three vestibular end-organs in VS patients correlates with an increased DHI scores (Dizziness Handicap Inventory), reflecting a severe handicap, while two or less defected vestibular end-organs correlate with a moderate dizziness handicap.

Several objective vestibular test batteries provide clinicians the opportunity to evaluate the function of the vestibular apparatus. At least one or more objective and/or electrophysiological vestibular tests are usually applied, typically the caloric reflex test, the rotary chair test, the vestibular evoked myogenic potential (VEMP) test, and/or head impulse test (HIT). Since HIT heavily depends on subjective observations of the clinician, very fast correction saccades that has been executed before the head impulse ended (‘covert saccade’) might be missed visually. Hence, high-rate video recordings of head-eye movements were introduced to also capture the covert saccades to diagnose vestibular functionality. In contrast to other vestibular tests, video recorded head impulse tests (vHIT) is a very fast and relatively easy test method to assess VOR, and forms part of most standard clinical equipment, opening up the possibility to obtain quantitative data on the functionality of the vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR) for each semicircular canal in the frequency range between 5 - 7 Hz [

8,

16]. Thus, vHIT is even used as diagnostic criteria of different vestibular disorders in recent years [

17,

18,

19].

As well as diagnostic benefits of vHIT, it also allow to monitor the effects of pathologies on VOR gains. In the past, typically, vestibular functions of patients with UVS was conventionally assessed by oculomotor -, caloric reflex-, and, if available, rotary chair testing[

20,

21,

22]). Then more recent studies has extended the test batteries with Vestibular Evoked Myogenic Potential (VEMP) recordings and/or the video-Head Impulse Test (vHIT) to evaluate peripheral vestibular end organs in UVS patients [

13,

23,

24]. However, these studies have mainly been focusing on the impact of VS on loss of vestibular function on the ipsilateral side of the lesion [

13,

25] or on its relation with age, tumor size, duration of disease or hearing loss [

25,

26,

27]. Thus, many studies have reported decreased vestibular function in the tumor side [

28,

29] but the vestibular function in the non-tumor side mostly has been remained less explained or even ignored. To our knowledge, the number of studies interpreting both ipsi- versus contralateral side in patients with UVS is therefore very limited or only includes a small number of observations [

12,

26,

27,

30]. Lee et al [

26] have investigated ipsi- and contralateral VOR reduction in 101 patients with UVS. Although they reported bilateral VOR data, unfortunately no correlations were reported and/or regression analyses were executed to investigate possible interaction between both sides, since the main goal of their study was to investigate the relation between clinical assessment and tumor size. Moreover, no study which is evaluating the bilateral effect of the UVS tumor adding control group data has been seen in the literature.

Rationale and Aim of the Present Study

As for bilateral effect of the UVS tumors, merely a retrospective analysis of clinical data obtained between 2014 and 2015 in a small group patients with untreated UVS revealed a reduction in the VOR on the ipsilateral side, i.e., the site of the lesion (unpublished data). Notably, this reduction was also observed on the contralateral (non-tumor) side in eight patients. Since the majority of studies on UVS to date have mainly been focused on the investigation of VOR functionality on the ipsilateral side, the . However, the majority of studies are characterized by a paucity of observations, a limitation that hinders the identification of subtle correlations between the different semicircular canals and/or inner ears as a result of UVS. The objective of this study is to examine the vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR) in patients with unilateral vestibular schwannomas (UVS) on the ipsilateral side (i.e., the side of the VS) and its impact on the contralateral non-tumor side in comparison to a healthy control group without any vestibular dysfunction.

2. Materials and Methods

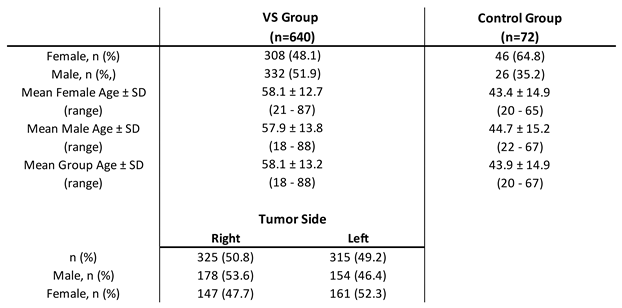

A retrospective investigation was conducted on the database of our tertiary referral center from 2014 to 2024. The objective of this investigation was to identify patients with unilateral vestibular schwannoma (UVS). The present study included a total of 640 patients with UVS (mean age: 58;1 ± 13;2 years) and a control group of 72 normal hearing, healthy adults (mean age: 43;9 ± 14;9 years). The clinical diagnosis of unilateral vestibular schwannomas (UVS) in all patients was made and subsequently confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Patients with other known vestibular pathologies documented in the medical records were excluded from the study. In 325 patients (50.8%), the vestibular schwannoma was diagnosed on the right side (see

Table 1, patient characteristics).

Given that the study in patients was an observational, retrospective nature and concerned the analysis of medical data obtained from patient records, it was deemed exempt from the provisions of the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act by the Local Ethical Committee. Normative data was acquired in a group of healthy adults with normal hearing (i.e. auditory thresholds for octave frequencies from 250 to 8000 Hz were ≤ 15 dBHL). This research adhered to the ethical principles for medical research of the World Medical Association according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was received from the institutional local human research and ethics committee (dossier NL87231.091.24) and informed consent was obtained from all individual participants of the control group.

2.1. Measurement Procedure

Subjects were asked to sit straight in a chair in front of a high-speed camera (vHIT Ulmer II device, Synapsys S.A.R.L., France). All participants underwent complete vHIT testing, i.e. responses were randomly obtained from all 6 semicircular canals. A high-speed camera was positioned in the middle, 90 cm away from the subject and 100 cm away from the wall to capture the eye movements during the head impulse (f

sample= 100 Hz). Subjects were asked to visually focus at three different dots on the wall, i.e. one frontal, one at 20 degrees to the right and one at 20 degrees to the left. For every semicircular canal, at least seven correct impulses were captured in the direction of each horizontal or vertical plane to stimulating each individual semicircular canal of interest. Head impulses were manually executed using an impulse with small angle movements between 15

0-25

0, similar to clinical execution of the ‘head thrust’ test [

31,

32]. Responses were automatically accepted or rejected by the vHIT software (vHIT Ulmer II, vs. 3.1.1.0) pre-defined head impulse velocity > 150

0/sec. For each impulse per semicircular canal, the gain was calculated, defined as the ratio between the output (eye movement) and the input (head movement) signal, calculated at the start of the impulse in a predefined region, defined by time interval [t

0;t

1], with t

0 = t

acc - 40 ms and t

1 = t

acc + 80 ms, where t

0 = start of head movement, and t

acc = time of head acceleration peak. The mean gains of each SCC with their standard deviations were used for analyses.

2.2. Analysis

The data for UVS patients was classified as tumor-side (TS, ipsilateral) and non-tumor-side (NTS, contralateral). Within-subject comparisons were made for VOR gain between the opposite same SCC in patients with UVS. The same procedure was replicated for the control group. Finally, data of the control group data was compared with data of the UVS patient group. All statistical analyses were performed in SPSS for Windows 27.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Shapiro-Wilk test was conducted to test the normality of data. The homogeneity of variances was tested by the Levene test. Student’s t-tests were conducted to analyze gender, and control vs. UVS group differences with respect to same SCC pairs. One-Way ANOVA and simple regression analysis were performed with Bonferroni corrections to evaluate the effect of the tumor on the non-tumor side. Pearson correlation coefficients (r) were calculated to test relationship between groups. Statistical significance was defined at the 5% level.

3. Results

It was possible to successfully obtain VOR gains (G) of all six horizontal and vertical canals in all UVS patients (n = 640) and all healthy control subjects (n = 72).

No statistical differences between VOR gains were found between females and males in the UVS group as well as in the control group for the same canal pairs on the same sides (paired samples t-tests, all p > 0.05). Therefore, in both groups, all data of both genders for the same canals were pooled for further analyses for each SCC.

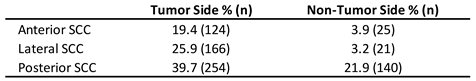

In the UVS group, most VOR gain reductions were found in the ipsilateral tumor side for the posterior SCC (i.e. G < 0.7), followed by a gain reduction in the lateral and anterior SCC (i.e. G < 0.8 and < 0.7, respectively). Remarkably, also in the non-tumor side, a reduction of gain was found in a significant number of patients for the posterior SCC, i.e. 21.9% of the total population, while the lateral and anterior SCC show less reduction: see

Table 2. Note that all mentioned percentages are absolute number of gain reductions for each SCC.

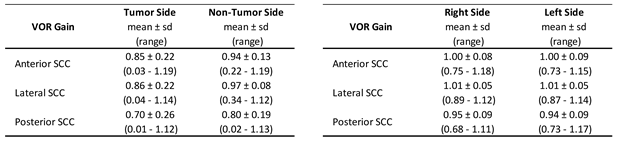

An overview of absolute mean VOR gains of each SCC are shown for the UVS patients and the control group in

Table 3.

Inter-aural correlations between absolute mean VOR gains of all semicircular canals for the UVS group as well as for the control group (Pearson’s correlation coefficients, all p < 0.001) are shown in

Table 4.

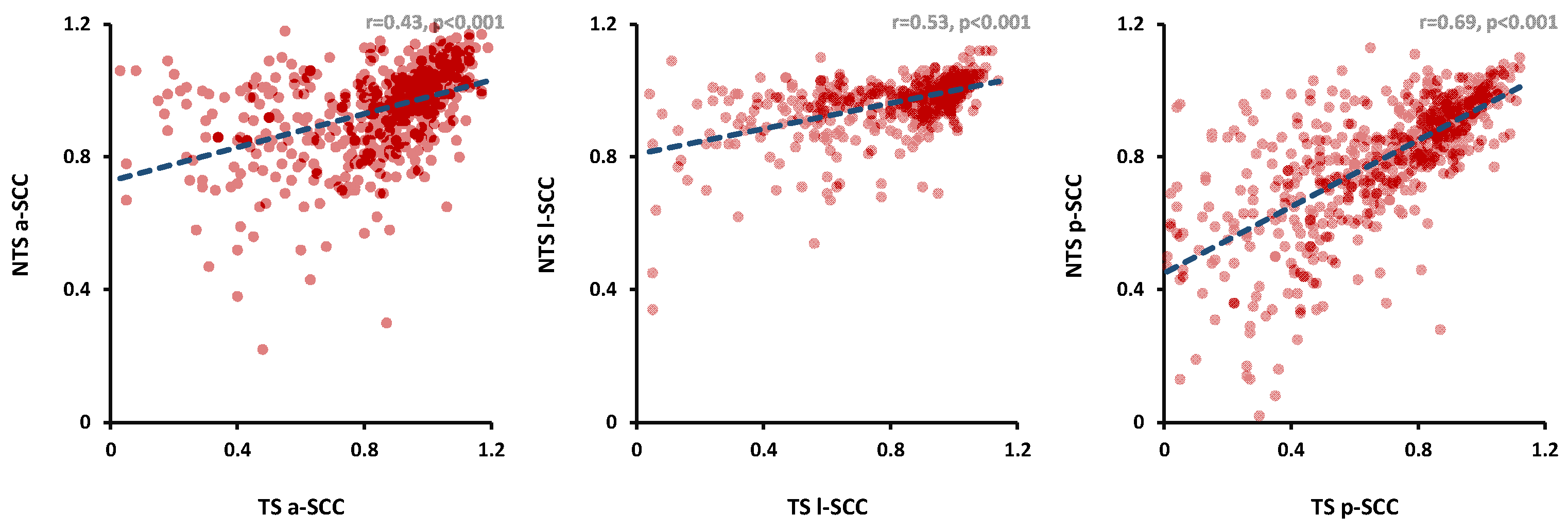

For the UVS group, the relation between the inter-aural VOR gains of each individual semicircular canal is depicted in a scatter plot: see

Figure 1. Pearson’s correlation coefficients show a statistically significant correlation between the VOR gains of the same SCC between both sides for all three semicircular canals, i.e. r=0.43, r=0.53, and r=0.69 for the anterior, lateral and posterior SCC, respectively (p<0.001).

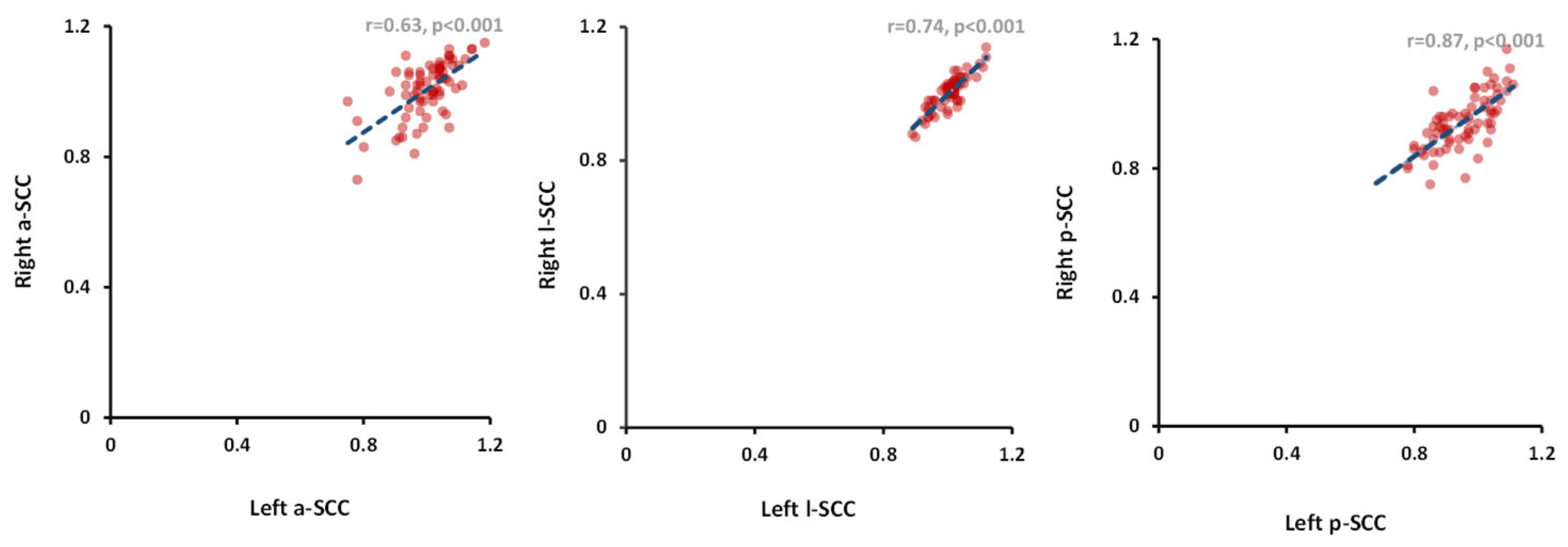

Similar to the UVS group, scatter plots of each SCC are depicted in

Figure 2 for the control group (n=72): Pearson’s correlation coefficients show statistically significant correlations between VOR gains of both sides, i.e. 0.63, 0.74, and 0.87 for the anterior, lateral and posterior SCC, respectively (p<0.001).

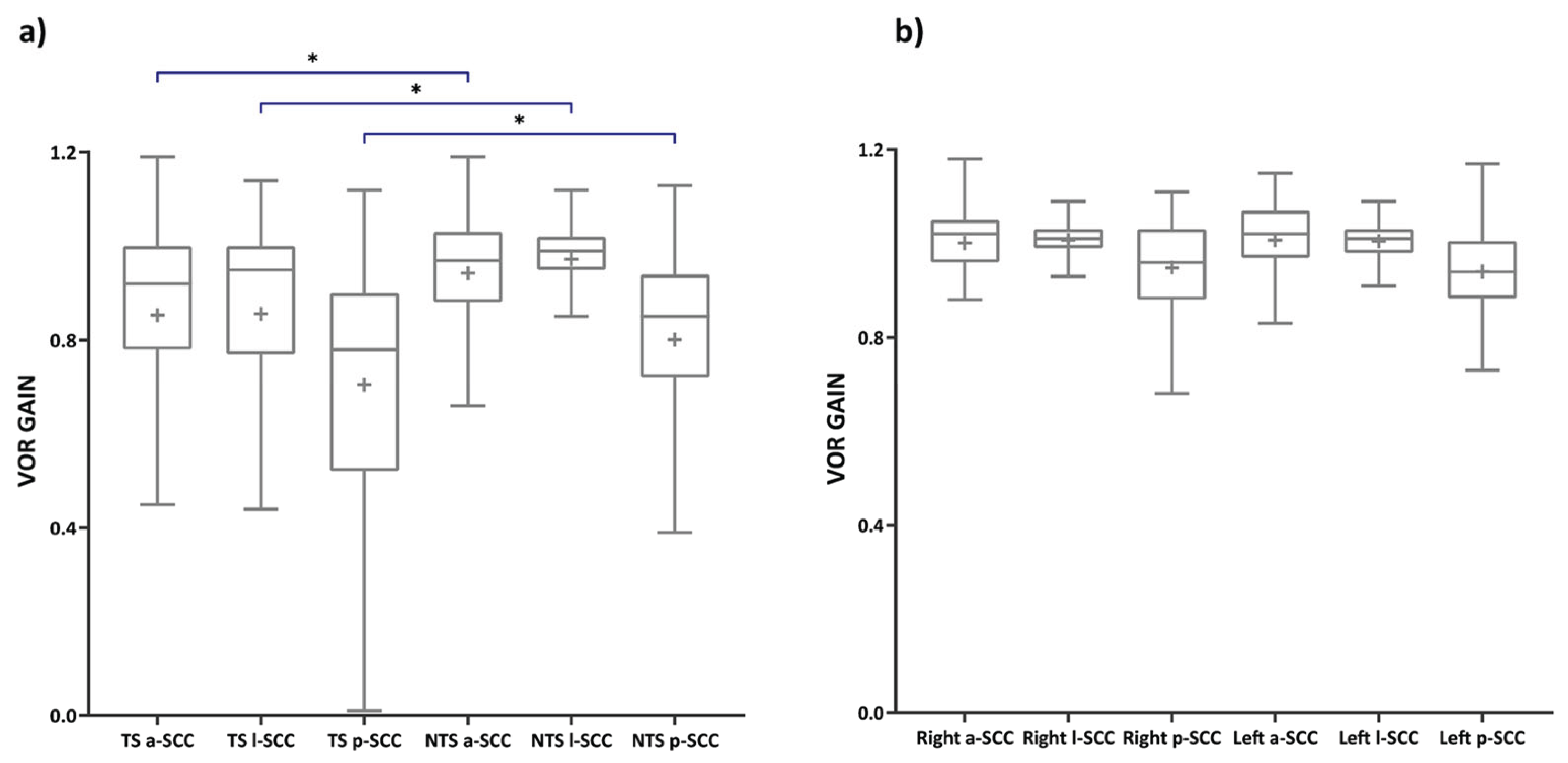

Box plots show an overview of VOR gains and ranges within each SCC of the UVS and the control group for all three SCCs in

Figure 3. To analyze between- and within-SCC gain differences in control group, One-Way ANOVA was performed (F(5,426) = 11.926, p < 0.001). Post-hoc tests were conducted with Bonferroni correction and showed that posterior SCCs were the only SCC that significantly differed from the others, but with no significant differences between anterior and lateral canal pairs. Additionally, no differences in VOR gain were found between bilateral posterior canals (p > 0.05).

Similar to control group analysis, all combinations of SCCs on the TS and NTS in the UVS group were tested for between- and within-SCC gain differences (One-Way ANOVA: F(5,3834)=165.111, p < 0.001). Post-hoc tests were conducted with Bonferroni correction and showed that posterior SCCs were the only SCCs that significantly differed from the others (p < 0.05). Moreover, VOR gains did not differ between the anterior and lateral SCCs on the TS, nor did they differ on the NTS (p > 0.05). However, TS and NTS comparisons showed differences for all same SCCs pairs (p < 0.001) with significant lower gains on TS: see also

Table 3.

As expected, statistical significant lower VOR gain differences were found in the TS of the UVS group compared to the control group for all three SCCs (paired samples t-tests: anterior SCC, t = 7.961, p < 0.001; lateral SCC, t = 8.738, p < 0.001; posterior SCC, t = 9.867, p < 0.001).

The same was also found for all SCCs in the NTS of the UVS group compared to the control group (paired samples t-tests: anterior SCC, t = 4.822, p < 0.001; lateral SCC, t = 4.331, p < 0.001; posterior SCC, t = 7.906, p < 0.001).

Additionally, a simple linear regression analysis was performed using the same canal pairs to estimate the effect of tumor-side (TS) VOR gain on non-tumor-side (NTS) VOR gain. Each TS semicircular canal (SCC) showed a significant effect on its each corresponding NTS canal pairs, with F(1,638) = 142.80, F(1,638) = 248.63, and F(1,638) = 592.70, for anterior, lateral, and posterior (or inferior branch) canals, respectively. For the anterior canal, a VOR gain reduction of 0.10 in TS was associated with 0.03 decrease in NTS (β = 0.25, 95% CI [0.21, 0.30], R2 = 0.18); for the lateral canal, a VOR gain reduction of 0.10 in TS was associated with 0.02 decrease in NTS (β = 0.19, 95% CI [0.17, 0.22], R2 = 0.28); for the posterior canal or inferior branch, a VOR gain reduction of 0.10 in TS was associated with 0.05 gain decrease in NTS (β = 0.50, 95% CI [0.46, 0.54], R2 = 0.48).

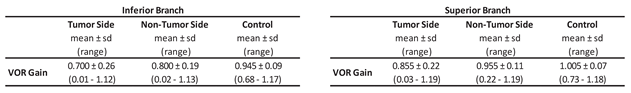

To determine which branch of the vestibular nerve has more impact on the NTS, gains of the inferior branch (posterior SCC) and the superior branch (mean gain of anterior and lateral SCCs) were calculated for both sides for UVS and control group (see

Table 5). Additionally, to see the effect of TS on NTS, regression analysis of superior branch was conducted. TS superior branch showed a significant effect on NTS superior branch F(1,1278) = 338.48, p < 0.001. For superior branch, a VOR gain reduction of 0.10 in TS was associated with a 0.02 decrease in NTS (β = 0.22, 95% CI [0.20, 0.25], R

2 = 0.21).

One-way ANOVA and post-hoc comparisons revealed significant differences between the VOR gain of TS, NTS and control for both inferior and superior branches: (F(2,1421) = 83.086, p < 0.001, and F(2,2845) = 175.671, p < 0.001, respectively).

The mean superior branch VOR gain of the control group was 1.005, and for the UVS group 0.855 for the TS and 0.955 for the NTS. The mean inferior branch VOR gain of the control group was 0.945, for the UVS group 0.700 and 0.800 for the TS and NTS, respectively (see

Table 5). Since the VORs of the control group also showed differences in gain per SCC, but not per side, the mean VOR gain of both sides of the control group was used as a reference when calculating the gain reduction within the UVS group. Hence, for the UVS group, the absolute gain reduction per branch was calculated: a superior branch reduction of 0.150 for the TS (1.005-0.855) and 0.050 (1.005-0.955) for the NTS and an inferior branch reduction of 0.245 for the TS (0.945-0.70) and 0.145 for the NTS (0.945-0.8). Thus, the reduction ratio was 0.33 (0.050/0.150) for the superior branch, in contrast to 0.59 (0.145/0.245) for the inferior branch, in which a higher reduction ratio represents higher impact of the VS on the contralateral side.

4. Discussion

In this study, we have compared the functionality of the vestibular-ocular reflex of each semicircular canal between the non-tumor side and the tumor side in patients with unilateral vestibular schwannoma. The distinguishing characteristic of our research is the substantial size of our data set (n=640 UVS) and the methodology we employed: in addition to the tumor group, a healthy control group (n=72) was included to ensure the reliability of the results obtained in UVS patients through interaural comparisons and correlation analyses. In essence, the primary objective of the control group data analysis was to perform a form of cross-checking rather than a direct comparison of the results obtained from the tumor and healthy groups. The present study's methodology is believed to contribute to its originality and to a more profound understanding of how the vestibular system reorganizes itself in unilateral pathologies.

Statistical analyses in control group revealed no differences in VOR gains for gender and side, which is in agreement with other studies [

33,

34,

35,

36]. In contrast, significant differences were found in the UVS group, showing reduction of the VOR on the tumor side compared to the contralateral non-tumor side.

It is well known that VOR gains on the side of the lesion might decrease in the presence of a VS [

28,

29]. In parallel with previous studies, our results support that the presence of VS tumors significantly decrease VOR gains of all canals on the tumor side. Besides VOR gains on TS, most of the studies ignore the NTS in VS patients. The number of studies mentioning contralateral VOR impairment in VS is therefore rather limited [

12,

26].

The present data are also in conformity with previous (unpublished) preliminary studies in a smaller group of UVS patients [

37,

38]. Caloric vestibular reflex reactivity and vHIT responses were obtained resulting in abnormal caloric reflexes (i.e. slow phase nystagmus velocities < 10 degrees/sec) in 49% of the patients on the side of lesion. However, in 7.5% of the patients with normal caloric reactivity, vHIT outcomes revealed an isolated posterior canal dysfunction, highlighting the added value of vHIT testing in patients with UVS when compared with caloric reflex testing, as vHIT assesses the vertical canals not covered by caloric testing [

38].

Other studies, [

12,

25,

27,

28] have also investigated the function of the vertical SCC in a relatively small number of patients with UVS. The study by Fujiwara et al. [

28] reported VOR reactivity in 15 patients with UVS, as determined by vHIT. The objective of their study was to investigate the functionality of the vertical SCC in UVS patients. The results of the study demonstrated a reduction in both the lateral VOR and the posterior VOR on the TS. However, the anterior VOR appeared to be less affected by the unilateral UVS. It was also noted that the vertical canals presented a greater challenge during examination, attributable to their unusual oblique vertical impulse movements, which contrasted with the comparatively straightforward lateral impulse movements. Nevertheless, in the absence of further elucidation from the authors, we recognized that their data set also exhibited a dysfunction of the posterior SCC on the unaffected side in 2 out of 15 subjects, which is in accordance with our data from a considerably larger population. Comparable reduction of the posterior VOR gain on the NTS was also reported by others [

12,

26,

27] although these studies were more focused on the sensitivity of different vestibular tests (caloric reflex, cVEMP, vHIT) related to TS and tumor volume without further exploration of the posterior canal gain reductions on the NTS and/or analyses of gain differences between and/or within SCCs.

Our data of UVS group revealed significant lower VOR gains in the posterior SCC compared to the other SCCs. Moreover, it showed that posterior SCC gain reduction on NTS (n=140, 21.9%) is remarkably more sensitive for the presence of a contralateral VS. Since this was found on both sides, it immediately raised the question whether these outcomes might be caused by variations in the practical execution of impulse movements in three different planes of the six semicircular canals, i.e. lateral (left-right), left anterior-right posterior (‘LARP’), and right anterior-left posterior (‘RALP’). To exclude the effect of any procedural bias such as variations in impulse movements executed by clinicians (e.g. unconscious preferences for impulse directions), asymmetrical neck muscle stiffness of patients, hard/software sensitivity of the recording device or other in/external factors causing variability, we have performed the same measurement procedures under exactly the same conditions in a group of healthy subjects (control group).

Contrary to our initial expectations, we observed that the control group exhibited significant correlations between bilateral SCC (see Fig. 2). However, we think that this is of negligible relevance, given that the range within the control group is evidently constrained (> 0.8 and > 0.7 for lateral and vertical SCC, respectively), with no discernible interaural variations. In contrast, the VOR gains in the UVS group exhibited a greater range (see Fig. 1), thereby rendering the correlations more meaningful and relevant for clinical interpretation.

Although we claim that the presence of a VS affects the contralateral NTS in UVS patients, it should also be recognized that the response variability in the vertical SCCs that we have reported in the UVS group was also seen in the control group too, albeit to a lesser extent (Fig. 3a). The posterior SCC seem to follow the same pattern in both groups. This might imply that response variability of vertical SCCs in itself appears to be more susceptible to variations resulting from external factors (such as e.g. the practical execution of short head impulse movements) than the horizontal SCCs as it is known that the vertical head impulse movements are generally more difficult to perform than horizontal impulse movements [

39], which is reflected in the lower normative cut-off values, that are clinically used for the vertical SCCs (i.e. 0.7). Consequently, this may mean that a small portion of the variability found in the UVS group is the result of bias due to practical recording of vHIT movements. Nevertheless, the present results found are of such magnitude that they will not undermine the interaural interdependence that we have observed in UVS patients.

4.1. Inferior vs. Superior Branch Crosstalk Between TS and NTS

Although we didn’t analyze the actual location of VS tumors on the n. VIII, we have compared VOR gains originating from the superior-branch-linked SCCs with the inferior branch and how it might affect the contralateral side by calculating the gain reduction ratio for each branch. For this, we took into account the absolute reduction in VOR reactivity that was also found in the posterior canal in the healthy population. Our UVS data showed that the most compromised SCC appeared to be the posterior SCC in both tumor as non-tumor side (see

Table 3). The fact that the posterior SCCs on both sides appear to be most sensitive to a decrease in VOR gain suggests that, in addition to a neural bilateral dependence, the inferior branch of the cochleovestibular nerve, might also play a role here, since it is responsible for the innervation of the posterior canal. After all, it is not entirely unlikely that the presence of a UVS apparently affects the VOR of the lateral and anterior canals less than that of the posterior canal, since it is known that the majority of vestibular schwannomas develop in the inferior branch of the vestibular nerve [

40].

By comparing the impact of the vestibular schwannoma on the NTS, our data demonstrate that the inferior branch exerts nearly twice the influence on the contralateral side, as evidenced by a gain reduction ratio of 0.33 (superior branch) compared to 0.59 (inferior branch). It is noteworthy that the inferior branch at the TS appears to exert a more significant influence on the VOR gain at the NTS than the superior branch. This observation suggests that a considerable proportion of the location of the VS in our UVS group would be more inferior, resulting in a diminished effect on the VOR gain of the anterior and lateral SCCs on the NTS. This finding provides further evidence to support the hypothesis that, within our population, the inferior branch of the n. VIII appears to be more sensitive to bilateral neural interactions than the superior branch.

4.2. Inhibitory Commissural Pathways Between Bilateral Vestibular Nuclei

A reduced number of type I hair cells and fibers on the tumor side has been reported [

41]. Other histological research have also shown that an isolated schwannoma on the superior vestibular branch of the 8th nerve can cause selective degeneration of neuroepithelia in the lateral and anterior [

42]or only in the posterior SCC [

43]. It is known that transient fast head movements, such as those performed during vHITs, will activate irregular afferent fibers that are mostly linked to these type I hair cells [

44,

45]. As a result, this histological change would lead to a decrease of VOR gain.

Besides hair cells damages, neural changes may play an important compensatory role in unilateral pathologies. A study in macaques who underwent unilateral labyrinthectomy [

46] showed that a neural reorganization of afferents takes place, resulting in a higher amount of irregular fibers after the damage. Similar compensatory processes might also take place in patients with UVS as a result of the loss of type I hair cells, which are more sensitive to phasic-encoding, i.e. fast movements.

On the other hand, unilateral acute vestibular neuritis or unilateral labyrinthectomy can alter responsiveness of the second-order neurons in the both vestibular nuclei by chemical changes [

47]. Physiologically, GABA-release within the vestibular nuclei sets baseline excitability and shapes the spike outputs. Any conditions that affect GABA-receptors’ responsiveness may also effect the VOR, since medial vestibular nuclei (MVN) on both sides are interconnected through commissural fibers. This connectivity between fibers provide reciprocal inhibition within the vestibular nuclei. This commissural inhibitory system may be the underlying cause of high correlations between tumor and non-tumor sides, despite the fact that the VOR gains are bilaterally reduced. The reciprocal inhibition and change of the GABA-receptors’ responsiveness support the phenomenon of vestibular compensation.

It is of noteworthy that the strong correlations that we found between the p-SCC of the right and left sides in our healthy subjects was retained among VS patients, suggesting that our vestibular system may attempt to compensate for the effect of VS on VOR gains through posterior canals. Taking into account the significant correlations that we observed within our UVS group, we conclude that the vestibular system must engage in a form of crosstalk between the tumor and non-tumor sides in order to compensate for the effects of the VS on VOR gains. It is hypothesized that this crosstalk may also assist in mitigating the impact of VS on balance in daily life, thereby ensuring an acceptable quality of life.

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

The distinguishing characteristic of this study is its inclusion of a substantial number of patients with UVS, a feature that differentiates it from the majority of previous studies in this field. Furthermore, the present study ascertained VOR gains of all SCCs in a substantial group of healthy subjects, thereby enabling the differences of subtle disparities in VOR gain between the three SCCs in the control group. This study also offers the advantage to compare the abnormal VORs exhibited by UVS patients, both at TS and NTS, with the mean gains observed in a healthy population within the relevant SCC. Consequently, VOR gains could be comparatively analyzed for each SCC, with the same SCC on the other side, as well as with that of the other SCC on the same side for both groups.

Nonetheless, it is acknowledged that the present study has been constrained in its scope to the functionality of the VOR of the individual and combined SCCs, while disregarding the size and location of the VS, unlike other studies.

While the present design was not focused on establishing a correlation between the predictive value of the vHIT and the size or anatomic location of the VS, a comparative analysis of the reactivity of SCCs innervated by either the superior or inferior branch of the eighth nerve was additionally conducted: by calculating the reduction ratio of both separate branches of the vestibular nerve, we were still able to obtain some information about differences in commissural connectivity between the vestibular nuclei at the brainstem level for both neural pathways.

5. Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the only one reporting the vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR) functionality on the non-tumor side in a large population of patients with untreated unilateral vestibular schwannomas (n=640). Patients with unilateral vestibular schwannoma show that 39.7% of them exhibits a reduced VOR gain in the ipsilateral posterior SCC. However, the most noteworthy finding is that, in addition to the impaired vestibular reactivity on the ipsilateral tumor side, the presence of a vestibular schwannoma also reveals an impact on the contralateral posterior SCC in the non-tumor side in 21.9% of patients. While both lateral and anterior SCCs also demonstrate a positive correlation with their contralateral equivalents, the most significant and strongest correlation was identified between the two posterior semicircular canals. Furthermore, our data suggest that lesions originating from the inferior branch of the vestibular nerve might be less affecting contralateral side. It also confirm the presence of underlying commissural pathways at the brainstem level that are responsible for neural crosstalk between the vestibular nuclei of the tumor and non-tumor side. The commissural interconnections of the VNs have been demonstrated to promote greater bilateral vestibular symmetry, thereby facilitating compensatory mechanisms and contributing to a reduction in subjective complaints. This observation suggests that clinicians should be aware that VOR on the contralateral side may also be partially impaired in a significant number of UVS patients, albeit unnoticed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, AB; methodology, AB; formal analysis, AB and ME; investigation, AB; data curation, AB and ME; writing original draft preparation, AB; writing review and editing, AB, ME, SS, TJ and HK; supervision, AB; project administration, AB; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research adhered to the ethical principles for medical research of the World Medical Association according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was received from the institutional local human research and ethics committee of the Radboud University Medical Center Nijmegen under file number NL87231.091.24 and informed consent was obtained from all individual participants of the control group. With respect to patient data, obtained from medical records, according to the Medical Ethical Research Involving Human Subjects Act, ethical approval was not required due to the retrospective nature and anonymization.

Informed Consent Statement

Page: 12 Informed consent was obtained from all healthy subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to acknowledge Karin Krommenhoek and Jacquelien Jilissen for their assistance with data acquisition.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interests or any funding from third parties or manufacturers of the products that have been used in this research.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NTS |

non-tumor side |

| SCC |

semicircular canal |

| TS |

tumor side |

| UVS |

unilateral vestibular schwannoma |

| vHIT |

video head impulse test |

| VOR |

vestibulo-ocular reflex |

| VS |

vestibular schwannoma |

| NTS |

non-tumor side |

References

- Verocay, J. Multipie Gaschwulste als systemerkrankung am nervosen Apparate. Festschrift fur chiari 1908, 387. [Google Scholar]

- Antoni, N. Über rückenmarkstumoren und neurofibrome: studien zur pathologischen anatomie und embryogenese. Über rückenmarkstumoren und neurofibrome: studien zur pathologischen anatomie und embryogenese 1920, 435–435. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, R. Learning from eponyms: Jose Verocay and Verocay bodies, Antoni A and B areas, Nils Antoni and Schwannomas. Indian Dermatol Online J 2012, 3, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tieleman, A.; Casselman, J.W.; Somers, T.; Delanote, J.; Kuhweide, R.; Ghekiere, J.; De Foer, B.; Offeciers, E.F. Imaging of intralabyrinthine schwannomas: a retrospective study of 52 cases with emphasis on lesion growth. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2008, 29, 898–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzman, K.L.; Childs, A.M.; Davidson, H.C.; Kennedy, R.J.; Shelton, C.; Harnsberger, H.R. Intralabyrinthine schwannomas: imaging diagnosis and classification. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2012, 33, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Xu, J.; Xu, M.; Zhou, L.F.; Zhang, R.; Lang, L.; Xu, Q.; Zhong, P.; Chen, M.; Wang, Y.; et al. Clinical features of intracranial vestibular schwannomas. Oncol Lett 2013, 5, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosahl, S.; Bohr, C.; Lell, M.; Hamm, K.; Iro, H. Diagnostics and therapy of vestibular schwannomas - an interdisciplinary challenge. GMS Curr Top Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2017, 16, Doc03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constanzo, F.; Teixeira, B.C.A.; Sens, P.; Ramina, R. Video Head Impulse Test in Vestibular Schwannoma: Relevance of Size and Cystic Component on Vestibular Impairment. Otol Neurotol 2019, 40, 511–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.U.; Bae, Y.J.; Kim, H.J.; Choi, J.Y.; Song, J.J.; Choi, B.Y.; Choi, B.S.; Koo, J.W.; Kim, J.S. Intralabyrinthine Schwannoma: Distinct Features for Differential Diagnosis. Front Neurol 2019, 10, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, B.C.d.A.; Constanzo, F.; Sens, P.; Ramina, R.; Escuissato, D.L. Brainstem hyperintensity in patients with vestibular schwannoma is associated with labyrinth signal on magnetic resonance imaging but not vestibulocochlear tests. The Neuroradiology Journal 2021, 34, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constanzo, F.; Teixeira, B.C.A.; Sens, P.; Escuissato, D.; Ramina, R. Relationship between Signal Intensity of the Labyrinth and Cochleovestibular Testing and Morphologic Features of Vestibular Schwannoma. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base 2022, 83, e208–e215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, K.S.; Nordahl, S.H.G.; Berge, J.E.; Dhayalan, D.; Goplen, F.K. Vestibular Tests Related to Tumor Volume in 137 Patients With Small to Medium-Sized Vestibular Schwannoma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2023, 169, 1268–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, N.C.; Groth, J.B.; Caye-Thomasen, P. Does Location of Intralabyrinthine Vestibular Schwannoma Determine Objective and Subjective Vestibular Function? Otol Neurotol 2024, 45, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halliday, J.; Rutherford, S.A.; McCabe, M.G.; Evans, D.G. An update on the diagnosis and treatment of vestibular schwannoma. Expert Rev Neurother 2018, 18, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kjærsgaard, J.B.; Szeremet, M.; Hougaard, D.D. Vestibular Deficits Correlating to Dizziness Handicap Inventory Score, Hearing Loss, and Tumor Size in a Danish Cohort of Vestibular Schwannoma Patients. Otology & Neurotology 2019, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, K.P.; MacDougall, H.G.; Halmagyi, G.M.; Curthoys, I.S. Impulsive testing of semicircular-canal function using video-oculography. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2009, 1164, 486–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, Y.; Van de Berg, R.; Wuyts, F.; Walther, L.; Magnusson, M.; Oh, E.; Sharpe, M.; Strupp, M. Presbyvestibulopathy: Diagnostic criteria Consensus document of the classification committee of the Bárány Society. J Vestib Res 2019, 29, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strupp, M.; Bisdorff, A.; Furman, J.; Hornibrook, J.; Jahn, K.; Maire, R.; Newman-Toker, D.; Magnusson, M. Acute unilateral vestibulopathy/vestibular neuritis: Diagnostic criteria. J Vestib Res 2022, 32, 389–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strupp, M.; Kim, J.S.; Murofushi, T.; Straumann, D.; Jen, J.C.; Rosengren, S.M.; Della Santina, C.C.; Kingma, H. Bilateral vestibulopathy: Diagnostic criteria Consensus document of the Classification Committee of the Bárány Society. J Vestib Res 2017, 27, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretz, W.H., Jr.; Orchik, D.J.; Shea, J.J., Jr.; Emmett, J.R. Low-frequency harmonic acceleration in the evaluation of patients with intracanalicular and cerebellopontine angle tumors. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1986, 95, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, K.S.; Lund-Johansen, M.; Nordahl, S.H.G.; Finnkirk, M.; Goplen, F.K. Long-term Effects of Conservative Management of Vestibular Schwannoma on Dizziness, Balance, and Caloric Function. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2019, 161, 846–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abboud, T.; Regelsberger, J.; Matschke, J.; Jowett, N.; Westphal, M.; Dalchow, C. Long-term vestibulocochlear functional outcome following retro-sigmoid approach to resection of vestibular schwannoma. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2016, 273, 719–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogawa, Y.; Otsuka, K.; Inagaki, T.; Nagai, N.; Itani, S.; Kondo, T.; Kohno, M.; Suzuki, M. Comparison of cervical vestibular evoked potentials evoked by air-conducted sound and bone-conducted vibration in vestibular Schwannoma patients. Acta Otolaryngol 2018, 138, 898–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahne, T.; Plontke, S.K.; Fröhlich, L.; Strauss, C. Optimized preoperative determination of nerve of origin in patients with vestibular schwannoma. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 8608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, K.; Morita, S.; Fukuda, A.; Akamatsu, H.; Yanagi, H.; Hoshino, K.; Nakamaru, Y.; Kano, S.; Homma, A. Analysis of semicircular canal function as evaluated by video Head Impulse Test in patients with vestibular schwannoma. J Vestib Res 2020, 30, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.Y.; Hassannia, F.; Rutka, J.A. Contralesional High-Acceleration Vestibulo-Ocular Reflex Function in Vestibular Schwannoma. Otology & Neurotology 2021, 42, e1106–e1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.L.; Kong, J.; Flanagan, S.; Pogson, J.; Croxson, G.; Pohl, D.; Welgampola, M.S. Prevalence of vestibular dysfunction in patients with vestibular schwannoma using video head-impulses and vestibular-evoked potentials. Journal of Neurology 2015, 262, 1228–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, K.; Yanagi, H.; Morita, S.; Hoshino, K.; Fukuda, A.; Nakamaru, Y.; Homma, A. Evaluation of Vertical Semicircular Canal Function in Patients With Vestibular Schwannoma. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2019, 128, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontorinis, G.; Tailor, H.; Tikka, T.; Slim, M.A.M. Six-canal video head impulse test in patients with labyrinthine and retrolabyrinthine pathology: detecting vestibulo-ocular reflex deficits. J Laryngol Otol 2023, 137, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiraraghi, N.; Gaggini, M.; Crowther, J.A.; Locke, R.; Taylor, W.; Kontorinis, G. Benefits of pre-labyrinthectomy intratympanic gentamicin: contralateral vestibular responses. J Laryngol Otol 2019, 133, 668–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halmagyi, G.M.; Chen, L.; MacDougall, H.G.; Weber, K.P.; McGarvie, L.A.; Curthoys, I.S. The Video Head Impulse Test. Front Neurol 2017, 8, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halmagyi, G.M.; Curthoys, I.S. A Clinical Sign of Canal Paresis. Archives of Neurology 1988, 45, 737–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emekci, T.; Uğur, K.Ş.; Cengiz, D.U.; Men Kılınç, F. Normative values for semicircular canal function with the video head impulse test (vHIT) in healthy adolescents. Acta oto-laryngologica 2021, 141, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Layman, A.J.; Geary, R.; Anson, E.; Carey, J.P.; Ferrucci, L.; Agrawal, Y. Epidemiology of vestibulo-ocular reflex function: data from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Otol Neurotol 2015, 36, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matiño-Soler, E.; Esteller-More, E.; Martin-Sanchez, J.-C.; Martinez-Sanchez, J.-M.; Perez-Fernandez, N. Normative data on angular vestibulo-ocular responses in the yaw axis measured using the video head impulse test. Otology & Neurotology 2015, 36, 466–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treviño-González, J.L.; Maldonado-Chapa, F.; González-Cantú, A.; Soto-Galindo, G.A.; Ángel, J.A.M.-d. Age adjusted normative data for Video Head Impulse Test in healthy subjects. American Journal of Otolaryngology 2021, 42, 103160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beynon, A.J. Isolated and combined semicircular canal dysfunction in patients with unilateral vestibular schwannoma. In Proceedings of the 7th International Symposium on Menière's Disease & Inner Ear Disorders, Rome, Italy, October 17-20, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Beynon, A.J. Surplus value of the video-head impulse test in patients with vestibular schwannoma. In Proceedings of the 22th World Congress of Neurology, Santiago, Chile, Oct 31-Nov 5, 2015; p. e174. [Google Scholar]

- Karabin, M.J.; Harrell, R.G.; Sparto, P.J.; Furman, J.M.; Redfern, M.S. Head and vestibular kinematics during vertical semicircular canal impulses. Journal of Vestibular Research 2023, 33, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khrais, T.; Romano, G.; Sanna, M. Nerve origin of vestibular schwannoma: a prospective study. The Journal of Laryngology & Otology 2008, 122, 128–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hızlı, Ö.; Cureoglu, S.; Kaya, S.; Schachern, P.A.; Paparella, M.M.; Adams, M.E. Quantitative Vestibular Labyrinthine Otopathology in Temporal Bones with Vestibular Schwannoma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2016, 154, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møller, M.N.; Hansen, S.; Caye-Thomasen, P. Peripheral Vestibular System Disease in Vestibular Schwannomas: A Human Temporal Bone Study. Otology & Neurotology 2015, 36, 1547–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, L.F.P.D. Inner Ear Pathology in Acoustic Neurinoma. Archives of Otolaryngology 1967, 85, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hullar, T.E.; Della Santina, C.C.; Hirvonen, T.; Lasker, D.M.; Carey, J.P.; Minor, L.B. Responses of irregularly discharging chinchilla semicircular canal vestibular-nerve afferents during high-frequency head rotations. J Neurophysiol 2005, 93, 2777–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCaslin, D.L.; Rivas, A.; Jacobson, G.P.; Bennett, M.L. The dissociation of video head impulse test (vHIT) and bithermal caloric test results provide topological localization of vestibular system impairment in patients with "definite" Ménière's disease. Am J Audiol 2015, 24, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadeghi, S.G.; Minor, L.B.; Cullen, K.E. Response of vestibular-nerve afferents to active and passive rotations under normal conditions and after unilateral labyrinthectomy. J Neurophysiol 2007, 97, 1503–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamanaka, T.; Him, A.; Cameron, S.A.; Dutia, M.B. Rapid compensatory changes in GABA receptor efficacy in rat vestibular neurones after unilateral labyrinthectomy. J Physiol 2000, 523 Pt 2, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |