1. Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) has rapidly transitioned from an experimental adjunct to a central force shaping contemporary medical education. Advances in machine learning, natural language processing, and generative large language models have enabled AI systems to perform tasks that were previously considered uniquely human, including clinical reasoning support, reflective writing, diagnostic synthesis, and feedback generation. These developments coincide with increasing pressures on medical education systems worldwide, including expanding student cohorts, constrained faculty capacity, heightened accountability to regulators, and growing public expectations regarding transparency and fairness in assessment [

1,

2,

3].

Medical education occupies a distinctive ethical and societal position among academic disciplines. Unlike many fields, its educational outcomes are directly linked to patient safety, professional licensure, and public trust. Assessment in medical education therefore functions not merely as a pedagogical tool, but as a mechanism of social accountability. It signals what institutions value, legitimizes professional progression, and reassures society that graduates are competent and trustworthy. Professionalism, in turn, provides the moral framework that gives meaning to assessment outcomes, shaping how competence, responsibility, and ethical conduct are understood and enacted [

4,

5].

Historically, assessment and professionalism have evolved as mutually reinforcing pillars of medical training. Assessment practices have gradually shifted from knowledge recall toward performance-based evaluation, while professionalism frameworks have emphasized honesty, accountability, and moral agency. The emergence of generative AI challenges this alignment by altering how knowledge is produced, how competence is demonstrated, and how responsibility is attributed. When AI systems can generate polished responses, clinical explanations, or reflective narratives that are indistinguishable from learner-generated work, foundational assumptions about authorship, effort, and integrity are destabilized [

6,

7].

Importantly, the disruption introduced by AI is not merely technical, it is normative. AI compels educators to reconsider what constitutes legitimate learning, ethical conduct, and professional responsibility in medical training. Questions that were once peripheral; such as how much assistance is acceptable, who is accountable for AI-assisted decisions, and how authenticity should be judged; have become central to educational practice. Framing AI solely as a tool or threat risks superficial solutions that fail to address its deeper implications for professional identity formation and moral development.

Globally, responses to AI in medical education have been uneven and often reactive. Some institutions have adopted restrictive policies emphasizing prohibition and surveillance, reflecting concerns about academic misconduct and assessment integrity. Others have encouraged exploratory use with minimal ethical guidance, citing innovation and efficiency. These divergent approaches risk amplifying inequities, creating confusion among learners, and undermining trust if assessment systems and professionalism frameworks are not recalibrated in parallel [

6].

The GCC region offers a particularly instructive context for examining these challenges. Over the past two decades, GCC countries have invested heavily in medical education expansion, digital infrastructure, and centralized accreditation and licensing systems. National development agendas, workforce nationalization policies, and rapid health system reform have driven unprecedented growth in medical schools and training programs. At the same time, centralized regulation and high-stakes national examinations place exceptional emphasis on assessment integrity and public accountability [

7,

8].

Sociocultural norms within the GCC further shape how professionalism is understood and enacted. Values such as respect for authority, collective responsibility, moral accountability, and service to society align closely with many core principles of medical professionalism. However, these norms may also influence how ethical ambiguity, policy uncertainty, or misconduct are discussed within educational environments. In the context of AI, where boundaries between legitimate assistance and misrepresentation are evolving, the absence of explicit guidance may encourage silent or covert practices rather than open dialogue [

7,

8].

Taken together, these features make the GCC neither a marginal nor a purely local case. Rather, it represents a high-stakes, system-level laboratory for understanding how medical education systems respond to AI-driven disruption. The region’s centralized governance structures offer opportunities for coordinated policy responses, while its rapid digital adoption magnifies both the risks and the potential lessons of AI integration [

7,

8].

This article examines artificial intelligence as a normative disruptor of assessment integrity and professionalism in medical education. Drawing on international scholarship, policy frameworks, and emerging regional evidence, it explores how AI reshapes assessment validity, professional identity formation, and ethical accountability. By integrating global perspectives with lessons from the GCC, the article aims to inform educators, institutions, and regulators seeking principled pathways for AI integration that preserve trust, fairness, and professional standards.

2. Artificial Intelligence and the Transformation of Assessment

2.1. From Knowledge Testing to AI-Mediated Performance

Assessment in medical education has undergone a sustained evolution over the past half-century. Early models emphasized knowledge recall and procedural accuracy, typically assessed through written examinations and oral vivas. While such approaches offered efficiency and standardization, they were increasingly criticized for limited validity in predicting clinical competence and professional behavior. In response, medical education progressively adopted competency-based and performance-oriented assessment strategies, including objective structured clinical examinations (OSCEs), workplace-based assessments, and reflective portfolios [

9,

10].

These innovations were intended to capture complex competencies such as clinical reasoning, communication, professionalism, and self-regulated learning. Crucially, they rested on an implicit assumption: that observed learner outputs represented authentic individual performance. Generative artificial intelligence fundamentally disrupts this assumption. Unlike earlier digital tools that primarily retrieved or summarized information, contemporary AI systems can generate original-seeming content that integrates medical knowledge, contextual reasoning, and professional language [

1,

11].

Medical students increasingly report using AI tools for drafting assignments, preparing case analyses, refining reflective writing, and clarifying clinical concepts. While such use may support learning, it complicates the interpretation of assessment outputs, particularly in unsupervised contexts. When assessment criteria emphasize coherence, insight, or sophistication of expression, AI-generated responses may meet or exceed expected standards without reflecting underlying competence [

12].

As a result, many traditional assessment formats—especially essays, take-home assignments, and reflective narratives—are increasingly vulnerable to construct-irrelevant variance. High scores may reflect proficiency in prompting or editing AI outputs rather than genuine clinical understanding or professional insight. This shift challenges not only assessment validity but also the educational meaning of achievement.

2.2. Assessment Validity and Reliability in the Age of AI

Validity remains the cornerstone of assessment quality in medical education. An assessment is valid to the extent that evidence and theory support the interpretations of scores for their intended use. Generative AI threatens validity by weakening the relationship between observed performance and the constructs an assessment is designed to measure. When AI contributes substantively to learner outputs, it becomes difficult to determine whether an assessment reflects knowledge, reasoning, communication skill, or technological proficiency [

5,

13].

Reliability is also affected. Patterns of AI use vary widely among learners depending on access, familiarity, ethical stance, and institutional guidance. Such variability introduces systematic bias, particularly in unsupervised assessments. Learners with greater access to or facility with AI tools may gain unfair advantages, undermining comparability and equity [

6,

12].

From a programmatic assessment perspective, these challenges underscore the limitations of relying on isolated assessment artifacts. Programmatic assessment models emphasize triangulation across multiple data points, contexts, and assessors to support robust judgments about competence. In AI-augmented environments, such approaches become even more critical, as no single assessment can be assumed to provide an uncontaminated signal of competence [

9,

12].

2.3. Authorship, Originality, and the Crisis of Attribution

Authorship assumptions underpinning academic integrity frameworks are particularly destabilized by AI. Traditional models presume that submitted work represents individual intellectual effort, with misconduct defined as plagiarism or unauthorized collaboration. AI-generated content occupies an ambiguous space: it is neither copied from a single source nor wholly produced by the learner. This ambiguity challenges existing definitions of originality, ownership, and responsibility [

14].

In medical education, where assessment outcomes inform progression, licensure, and ultimately patient care, such ambiguity has significant implications. If learners can present AI-generated work as their own without disclosure, assessment outcomes may offer false assurances of competence. Over time, this erosion of credibility threatens the social contract between medical schools and the societies they serve [

15].

Scholars increasingly argue that authorship in the AI era should be reframed around accountability rather than sole production

. From this perspective, ethical practice requires transparency about AI use and responsibility for the accuracy, appropriateness, and consequences of AI-assisted outputs. However, translating this principle into assessment policy and practice remains challenging [

14,

15].

2.4. Reframing Academic Misconduct Beyond Binary Models

Early institutional responses to AI in assessment often mirrored earlier reactions to plagiarism detection technologies, emphasizing prohibition, surveillance, and punitive enforcement. While such approaches may signal commitment to integrity, they are increasingly recognized as insufficient and potentially counterproductive. Blanket bans are difficult to enforce, risk driving covert use, and may undermine trust between learners and educators [

6,

7].

Conversely, permissive approaches that treat AI as a neutral productivity tool risk normalizing misrepresentation and ethical disengagement. Binary classifications of AI use as either “cheating” or “acceptable assistance” are therefore increasingly difficult to sustain in contemporary educational contexts [

14,

15].

Recent scholarship advocates reframing academic misconduct in terms of intent, transparency, and alignment with learning objectives

, rather than tool use alone. Under this model, undisclosed AI substitution that misrepresents competence constitutes misconduct, whereas guided, transparent use aligned with educational goals may be ethically defensible. This approach aligns more closely with professionalism principles, emphasizing honesty and accountability rather than mere compliance [

15,

16].

2.5. Assessment Redesign for AI-Resilient Validity

Addressing AI-related challenges requires not only policy statements but substantive assessment redesign. Strategies that emphasize reasoning processes, observed performance, and longitudinal evaluation are more resilient to AI substitution than those relying on polished written products. Oral defenses, observed clinical encounters, workplace-based assessments, and narrative feedback offer opportunities to assess competence in contexts where AI assistance is less easily concealed [

12,

16]. Importantly, such approaches also reinforce professionalism by emphasizing responsibility, reflection, and ethical engagement. When learners understand that assessment focuses on sustained performance and professional behavior rather than isolated artifacts, incentives for misrepresentation diminish. Assessment redesign thus serves both psychometric and moral functions [

13,

16]

However, redesigning assessment systems is resource-intensive and requires faculty development, institutional commitment, and regulatory alignment. Without coordinated efforts, particularly in high-stakes systems, institutions may default to superficial solutions that fail to address underlying issues.

2.6. Assessment Integrity as a Moral Signal

Assessment practices communicate powerful messages about what institutions value. In AI-augmented environments, failure to adapt assessment systems risks signaling that outcomes matter more than integrity. Conversely, transparent policies, thoughtful redesign, and open dialogue about AI use can reinforce professionalism and trust [

12,

14]

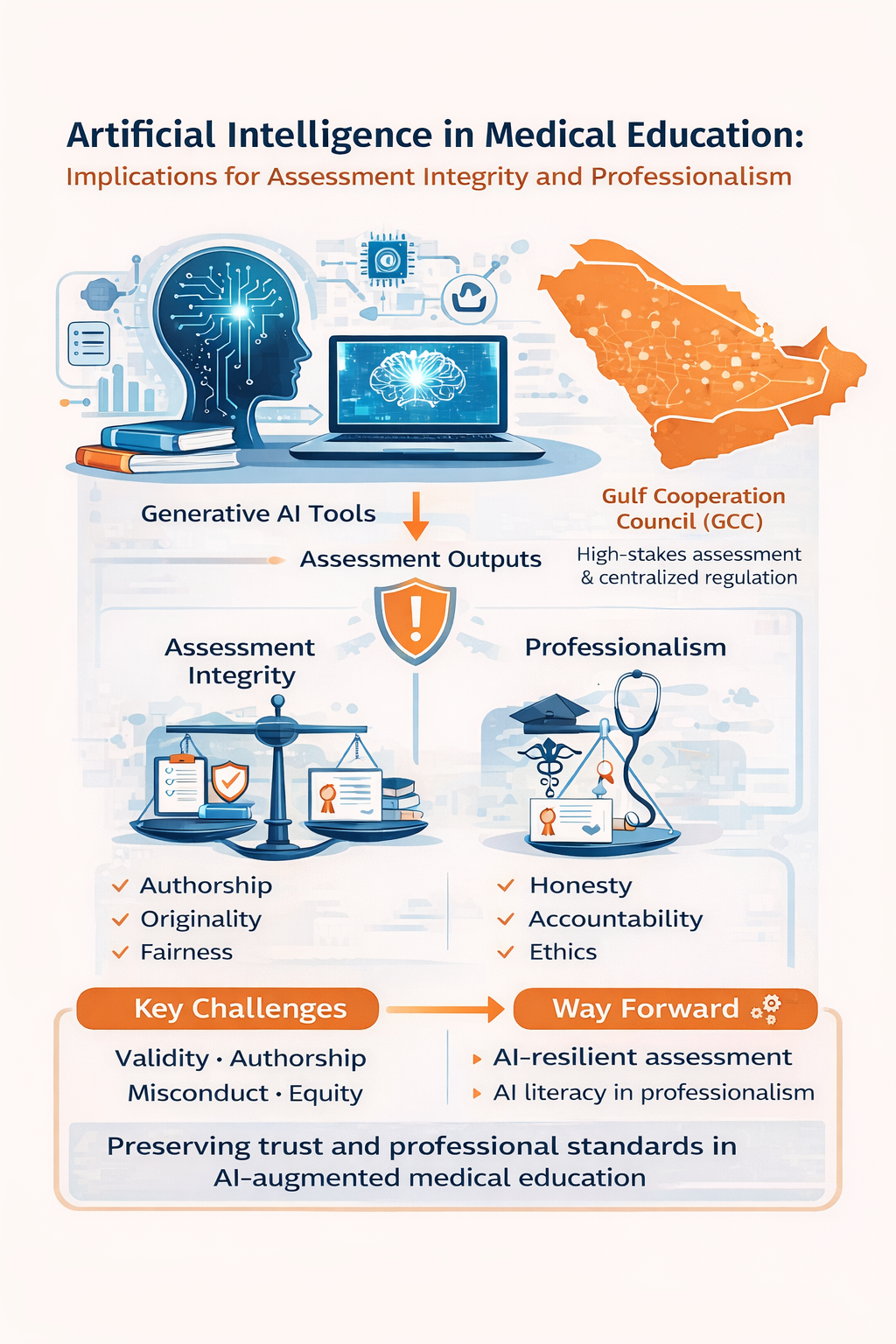

Assessment integrity should therefore be understood not merely as technical compliance, but as a moral signal that shapes learner behavior and professional identity. AI challenges educators to make these signals explicit, coherent, and aligned with the ethical commitments of the medical profession. The interrelationships between artificial intelligence, assessment integrity, professionalism, and governance in medical education are summarized in

Figure 1.

3. Professionalism and Ethical Identity in the Age of Artificial Intelligence

3.1. Professionalism as a Moral Practice in Medical Education

Professionalism has long been recognized as a foundational outcome of medical education, encompassing values such as honesty, accountability, respect for patients, commitment to competence, and ethical responsibility. Unlike technical skills, professionalism is not acquired through discrete instruction alone but develops through a complex process of socialization, role modeling, assessment, and lived experience within educational and clinical environments [

15,

16]. As such, professionalism is best understood not merely as a set of observable behaviors but as a moral practice that shapes professional identity and guides decision-making in contexts of uncertainty [

14].

Professional identity formation theory emphasizes that becoming a physician involves internalizing the values, norms, and responsibilities of the profession through repeated participation in authentic practice. This process depends on learners confronting ambiguity, uncertainty, and accountability—experiences that foster moral agency and ethical resilience [

12,

15]. Artificial intelligence challenges this developmental pathway by mediating intellectual labor and, in some cases, substituting for cognitive processes traditionally associated with professional judgment.

When learners rely on AI systems to generate clinical explanations, reflective narratives, or ethical analyses, they may appear to meet performance expectations without engaging in the moral reasoning processes those tasks are intended to elicit. This risks decoupling outward performance from inward ethical development, undermining the formative role of professionalism in education [

15,

16]. Over time, such decoupling may weaken learners’ capacity to assume responsibility for complex clinical decisions.

3.2. Digital Professionalism and the Expansion of Ethical Domains

The concept of digital professionalism emerged in response to the increasing use of online platforms, social media, and electronic health records in medical practice. It extends traditional professional values, confidentiality, respect, accountability, and integrity into technology-mediated contexts [

14,

17]. Artificial intelligence significantly expands this ethical domain by introducing opaque algorithms, probabilistic outputs, and systems capable of generating authoritative-seeming medical content.

In AI-augmented learning environments, professionalism increasingly requires critical engagement with technology. Physicians and trainees must understand not only how to use AI tools, but also when to question their outputs, recognize limitations, and retain responsibility for decisions informed by algorithmic assistance [

14,

17]. Ethical practice in this context involves maintaining human oversight and judgment, rather than deferring authority to automated systems [

18].

Without explicit guidance, learners may develop habits of uncritical reliance, assuming that technologically sophisticated outputs are inherently trustworthy. Such assumptions conflict with professional obligations to exercise independent judgment and safeguard patient welfare. Embedding AI literacy within professionalism curricula is therefore essential to ensure that technological competence does not outpace ethical understanding [

17].

3.3. Professionalism, Assessment, and Ethical Drift

Assessment plays a central role in signaling professional values. What institutions choose to assess and how they assess it, communicates implicit messages about what behaviors are rewarded. When assessment systems fail to adapt to AI-mediated learning environments, they risk incentivizing practices that conflict with professionalism ideals [

12].

For example, reflective writing has become a common method for assessing professional identity development, ethical awareness, and self-regulation. However, when reflections are assessed primarily on eloquence or perceived insight without mechanisms to verify authenticity, students may perceive AI-generated reflections as an efficient means of meeting requirements. Over time, such practices may normalize misrepresentation and contribute to ethical drift, whereby behaviors once considered unacceptable become tacitly tolerated [

13,

18].

Professionalism assessment has always been challenging due to its subjective and contextual nature. AI compounds this difficulty by introducing ambiguity regarding authorship and intent. Without transparent expectations and consistent enforcement, learners may experience confusion about ethical boundaries, undermining trust in institutional fairness and legitimacy [

15,

16].

3.4. The Hidden Curriculum in AI-Augmented Learning Environments

The hidden curriculum encompassing the informal messages conveyed through institutional culture, policies, and behaviors, plays a powerful role in shaping professional identity. Learners observe how faculty respond to ethical dilemmas, how policies are applied in practice, and which behaviors are rewarded or ignored [

19,

20].

In AI-augmented environments, the hidden curriculum may be amplified rather than diminished. If faculty members quietly use AI tools for efficiency while discouraging or penalizing student use, learners may perceive a double standard that undermines ethical messaging. Similarly, inconsistent responses to suspected AI misuse ranging from punitive to permissive can signal that integrity is negotiable rather than foundational [

6,

21].

Research on professional identity formation underscores the importance of psychological safety and open dialogue in ethical learning. Institutions that encourage transparent discussion of AI use, ethical uncertainty, and boundary-setting are better positioned to align the hidden curriculum with formal professionalism goals [

22,

23].

3.5. Trust, Supervision, and Accountability in the AI Era

Trust is central to both medical education and clinical practice. Educators must trust learners to engage honestly with assessments, while learners must trust institutions to apply standards fairly. Artificial intelligence introduces opacity into this relationship by making it difficult to determine the extent of AI involvement in learner outputs [

17].

Excessive surveillance or reliance on detection technologies may erode trust, creating adversarial learning environments that prioritize compliance over ethical development. Conversely, unregulated permissiveness risks undermining assessment credibility and public confidence. Navigating this tension requires a recalibration of supervision and accountability frameworks [

17,

18].

Longitudinal assessment models, workplace-based observation, and narrative evaluation offer promising approaches for sustaining trust in AI-augmented environments. By emphasizing sustained performance, professional behavior, and reflective dialogue over isolated artifacts, these approaches reduce incentives for misrepresentation while reinforcing accountability [

24,

25].

3.6. Regional and Global Perspectives on Professionalism and AI

Recent scholarship emphasizes that professionalism and AI ethics cannot be divorced from sociocultural context. Norms governing authority, accountability, and moral responsibility influence how AI use is perceived and regulated. In high-stakes systems, where assessment outcomes carry significant consequences, ambiguity regarding ethical boundaries may be particularly destabilizing [

21,

26].

Mir et al. highlight that while AI offers transformative potential for medical education, its unregulated use risks eroding academic integrity and professional accountability. They argue that AI integration must be accompanied by explicit ethical frameworks grounded in professionalism rather than efficiency alone [

27]. This insight resonates across global contexts and reinforces the need to treat AI not merely as a technical innovation, but as a catalyst for renewed engagement with the moral foundations of medical education.

4. Global Responses: Policies, Frameworks, and Persistent Gaps

4.1. Institutional Responses to Generative AI in Medical Education

Across regions, institutional responses to generative AI in medical education have been heterogeneous and largely reactive. Early policy statements frequently framed AI as a threat to academic integrity, mirroring earlier responses to plagiarism detection technologies. These approaches emphasized prohibition, surveillance, and punitive enforcement, often without parallel investment in assessment redesign or ethical education [

26,

27].

While restrictive policies may signal institutional concern for integrity, evidence suggests that surveillance-oriented strategies are difficult to enforce and may inadvertently undermine trust. Learners report uncertainty about acceptable practices, leading to covert AI use rather than transparent engagement. Such dynamics risk widening the gap between formal policy and actual practice, thereby weakening the moral authority of professionalism frameworks [

10,

28].

More recent institutional guidance has shifted toward managed integration, acknowledging that AI tools are already embedded in learners’ study practices. These approaches emphasize disclosure, alignment with learning objectives, and educator judgment. However, implementation remains uneven, and many policies lack operational clarity regarding assessment design, acceptable use thresholds, and accountability mechanisms [

10,

17].

4.2. Accreditation Bodies, Regulators, and Licensing Authorities

Accreditation bodies and professional regulators play a pivotal role in shaping institutional responses to AI. Organizations responsible for setting standards in medical education have begun to acknowledge AI’s implications for curriculum design, assessment validity, and professional competence. However, explicit accreditation standards addressing generative AI remain limited [

27,

29,

30].

Most existing frameworks emphasize outcomes such as assessment quality, fairness, and professionalism, but they were developed prior to the widespread availability of generative AI. As a result, institutions are left to interpret broad principles without concrete guidance on how to adapt assessment systems or professionalism expectations in AI-augmented environments [

30,

31].

Licensing examinations present a particular challenge. High-stakes assessments rely on assumptions of controlled conditions and individual authorship. As AI capabilities continue to advance, ensuring the relevance, validity, and integrity of licensure processes will require substantive redesign, including greater emphasis on performance-based evaluation, oral assessment, and longitudinal evidence of competence [

28,

31,

32].

4.3. National and International Policy Guidance

At national and international levels, several organizations have issued ethical frameworks relevant to AI in education and healthcare. UNESCO’s guidance on generative AI in education emphasizes human-centered values, equity, transparency, and accountability, urging institutions to prioritize ethical considerations alongside innovation [

17]. Similarly, the World Health Organization’s framework on the ethics and governance of AI for health highlights principles such as human autonomy, inclusiveness, and responsibility for AI-assisted decisions [

28].While these documents provide important normative anchors, they remain high-level and do not address the specific challenges of assessment integrity and professionalism in medical education. The absence of discipline-specific guidance leaves institutions to navigate complex ethical terrain independently, contributing to variability in practice and uncertainty among faculty and learners [

30].

4.4. Faculty Preparedness and Capacity Gaps

Faculty preparedness represents one of the most significant barriers to effective AI integration. Studies consistently indicate that many medical educators feel underprepared to understand AI capabilities, redesign assessments, or facilitate ethical discussions related to AI use. This gap is particularly pronounced among clinical faculty, who face competing demands on time and may have limited exposure to educational technology training [

33,

34].

Without targeted faculty development, institutional policies risk remaining symbolic. Educators may default to restrictive practices or avoid addressing AI altogether, reinforcing hidden curricula that prioritize compliance over ethical reasoning. Effective faculty development must therefore address not only technical literacy but also assessment design, ethical facilitation, and professional role modeling in AI-augmented contexts [

28,

35].

4.5. Equity, Access, and Global Disparities

AI adoption also raises important equity concerns. Access to advanced AI tools varies across institutions, regions, and socioeconomic contexts. Learners with greater access or familiarity may gain unfair advantages, exacerbating existing disparities. Additionally, AI systems trained predominantly on data from high-income settings may reflect cultural and epistemic biases that limit their applicability across diverse educational environments [

36,

37].

From a global perspective, these disparities underscore the risk of technological determinism

, whereby innovation outpaces ethical reflection and contextual adaptation. Addressing equity requires intentional policy design, inclusive stakeholder engagement, and ongoing evaluation of AI’s unintended consequences [

36,

37].

4.6. Toward Assessment Resilience Rather than Control

An emerging body of evidence advocates shifting from control-oriented approaches toward assessment resilience. Rather than attempting to detect or eliminate AI use, resilient assessment systems emphasize authenticity, triangulation, and longitudinal judgment. Such systems are better equipped to withstand technological change while preserving trust and validity [

31,

33].

Assessment resilience aligns closely with professionalism goals by reinforcing accountability, transparency, and reflective practice. When learners understand that assessment focuses on sustained performance and ethical conduct rather than isolated artifacts, incentives for misrepresentation diminish. This approach offers a promising pathway for aligning global policy responses with the realities of AI-augmented medical education [

28,

29].

5. Gulf Cooperation Council Perspectives and Lessons

5.1. Rapid Digital Transformation and Medical Education Reform in the GCC

Over the past two decades, countries of the GCC have undertaken rapid and large-scale reforms in medical education, driven by population growth, expanding health-care systems, workforce nationalization policies, and ambitious national development agendas. These reforms have included the establishment of new medical schools, expansion of postgraduate training pathways, and substantial investment in digital infrastructure, simulation centers, and centralized quality-assurance mechanisms [

7,

8,

38,

39].

Digital transformation has been a defining feature of this evolution. Learning management systems, electronic assessment platforms, virtual simulation, and tele-education initiatives are now embedded across undergraduate and postgraduate medical training in the region. The COVID-19 pandemic further accelerated reliance on digital tools, normalizing online assessment and remote learning modalities [

40]. Within this context, the emergence of generative artificial intelligence represents not a discrete innovation, but an intensification of ongoing digital disruption in GCC medical education [

4].

5.2. Centralized Accreditation, Licensing, and High-Stakes Assessment

A distinctive characteristic of GCC medical education systems is the presence of centralized accreditation bodies and national licensing examinations [

7,

8,

41]. These structures aim to ensure standardization, quality assurance, and public trust across rapidly expanding educational institutions. At the same time, they amplify the ethical and practical stakes of assessment integrity, as examination outcomes have direct implications for progression, licensure, and employment [

38,

39]. Key domains through which artificial intelligence disrupts assessment integrity and professionalism in medical education are summarized in

Table 1.

The integration of AI into learning environments challenges assumptions underpinning these systems, particularly regarding individual authorship and controlled assessment conditions. While supervised licensing examinations may remain relatively insulated from AI misuse in the short term, upstream assessments such as coursework, portfolios, and formative evaluations are increasingly vulnerable. Inconsistent institutional responses risk creating misalignment between local educational practices and national regulatory expectations [

7,

42,

43].

However, centralized governance also offers a strategic advantage. Unlike fragmented systems where institutional policies vary widely, GCC regulators are well positioned to issue coordinated guidance on AI use, assessment redesign, and professionalism standards. Such alignment could reduce uncertainty for institutions and learners while reinforcing public confidence in medical qualifications [

38,

43].

5.3. Sociocultural Context and Professional Expectations

Professionalism in the GCC is shaped by sociocultural norms emphasizing respect for authority, collective responsibility, moral accountability, and service to society. These values align closely with many core principles of medical professionalism, including integrity, duty, and ethical conduct. At the same time, they influence how ethical ambiguity, policy uncertainty, and misconduct are discussed within educational settings [

43,

44,

45].

In hierarchical educational cultures, learners may be less inclined to openly question boundaries or seek clarification when guidance is unclear. In the context of AI, where acceptable practices are evolving rapidly, this dynamic may encourage silent or covert use rather than transparent engagement. Without explicit institutional guidance, students may rely on peer norms or perceived expectations, increasing variability in ethical standards [

38,

42].

Generative AI further complicates traditional authority structures by democratizing access to expert-level outputs. Learners may increasingly question the epistemic authority of educators when AI-generated responses appear comparable to faculty explanations. Addressing this shift requires re-articulating professionalism not through control, but through ethical leadership, dialogue, and shared responsibility [

43].

5.4. Evidence from the Region: Opportunities and Gaps

Emerging evidence from the GCC highlights both enthusiasm for AI adoption and significant gaps in preparedness. Studies and commentaries indicate that medical students frequently use AI tools for learning support, exam preparation, and content generation, often in the absence of clear institutional policies. Faculty awareness and confidence, however, vary widely, with many educators reporting uncertainty regarding acceptable use, assessment implications, and ethical boundaries [

46,

47].

Mir et al. emphasize that while AI holds promise for enhancing medical education in the region, its unregulated use risks undermining academic integrity and professional accountability. They argue for structured frameworks that integrate AI literacy, ethical guidance, and assessment reform within existing accreditation and quality-assurance systems [

27]. These findings echo global concerns but are intensified in high-stakes, rapidly evolving educational environments such as the GCC [

28]. Without proactive governance, institutions may respond reactively to perceived misconduct, prioritizing surveillance and punishment over educational coherence. Such approaches risk eroding trust and weakening the formative role of professionalism education [

15].

5.5. Transferable Lessons from the GCC Experience

The GCC experience offers several lessons of broader relevance to global medical education. First, system-level governance matters

. Centralized accreditation and licensing structures create opportunities for coherent, region-wide approaches to AI integration that balance innovation with ethical safeguards. This contrasts with fragmented systems where institutional policies may conflict or compete [

7,

8,

27].

Second, professionalism frameworks must be culturally responsive

. Ethical guidance on AI use should resonate with local values while aligning with international standards. Framing AI governance in terms of trust, responsibility, and service to society may be more effective than purely technocratic or punitive approaches [

42,

43].

Third, assessment reform and professionalism cannot be decoupled

. Addressing AI-related challenges requires aligning assessment design, faculty development, and professional identity formation. Longitudinal assessment models, workplace-based evaluation, and narrative feedback are particularly well suited to reinforcing accountability and trust in AI-augmented environments [

43,

45].

Finally, the GCC illustrates that AI should not be framed solely as a threat to integrity, but as a catalyst for re-examining foundational assumptions about competence, authorship, and ethical responsibility [

46]. By engaging proactively with these questions, medical education systems can strengthen rather than weaken the moral foundations of the profession [

46,

47].

6. Future Directions and Recommendations

The integration of artificial intelligence into medical education marks a structural shift rather than a transient disruption. As AI tools continue to evolve in capability and accessibility, medical education systems must move beyond reactive or prohibition-focused responses toward intentional, principled integration. The central challenge is not whether AI will be used, but how its use can be aligned with the core purposes of assessment, professionalism, and public accountability [

43,

47].

A primary priority for the future is assessment redesign. Traditional assessment formats that rely heavily on unsupervised written outputs are increasingly vulnerable to AI substitution and should no longer be relied upon as primary indicators of competence. Medical education programs should invest in assessment strategies that emphasize reasoning processes, observed performance, and longitudinal evidence of competence. Oral examinations, workplace-based assessments, structured clinical encounters, and programmatic assessment models offer greater resilience in AI-augmented environments and better reflect the realities of clinical practice.

Equally important is the explicit integration of AI literacy within professionalism curricula. Learners must be supported to develop not only technical familiarity with AI tools, but also ethical discernment regarding their appropriate use. This includes understanding AI limitations, recognizing bias and uncertainty, maintaining transparency about AI assistance, and retaining responsibility for clinical and academic decisions. Positioning AI literacy as a component of professionalism reinforces the principle that ethical responsibility cannot be delegated to technology.

Faculty development represents a critical enabler of these reforms. Educators require structured support to understand AI capabilities, redesign assessments, facilitate ethical discussions, and model professional behavior in AI-augmented contexts. Without such support, institutional policies risk remaining symbolic, and hidden curricula may undermine formal guidance. Faculty development initiatives should therefore address both pedagogical innovation and ethical leadership.

At the institutional and regulatory levels, transparent governance frameworks are essential. Policies on AI use should be clearly articulated, consistently applied, and aligned with accreditation and licensing standards. Rather than focusing solely on detection or enforcement, governance should emphasize disclosure, accountability, and educational coherence. In regions with centralized regulatory structures, coordinated system-level guidance offers an opportunity to reduce uncertainty and promote consistency across institutions.

Finally, future research should move beyond descriptive accounts of AI use to examine its impact on learning, assessment validity, professional identity formation, and trust. Comparative studies across cultural and regulatory contexts will be particularly valuable in informing globally relevant, context-sensitive approaches to AI integration in medical education.

7. Conclusion

Artificial intelligence represents one of the most consequential challenges and opportunities facing contemporary medical education. Its impact extends well beyond efficiency or innovation, reaching into the moral foundations of assessment, professionalism, and public trust. Treating AI solely as a technological issue risks superficial solutions that fail to address its deeper normative implications.

This article has argued that AI functions as a normative disruptor, compelling educators and regulators to reconsider how competence, integrity, and professional identity are defined and assessed. By reshaping authorship, accountability, and performance, AI exposes vulnerabilities in traditional assessment systems and highlights the need for closer alignment between assessment practices and professionalism frameworks.

The experiences and emerging lessons from the GCC region illustrate both the risks of unregulated AI adoption and the opportunities afforded by coordinated governance, strong professional norms, and system-level reform. While the GCC context is distinctive, the challenges it faces are increasingly global, making its responses relevant beyond the region.

Ultimately, the question is not whether AI will be integrated into medical education, but whether that integration will reinforce or erode the values upon which the medical profession depends. Principled, transparent, and culturally responsive approaches grounded in assessment integrity and professionalism are essential to ensuring that artificial intelligence strengthens rather than diminishes the formation of future physicians.

Funding

This study has no funding from any source.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at the University of Bisha for supporting this work through the Fast-Track Research Support Program.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

References

- Topol, E.J. High-performance medicine: The convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masters, K. Artificial intelligence in medical education. Med. Teach. 2019, 41, 976–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidener, L.; Fischer, M. Artificial Intelligence Teaching as Part of Medical Education: Qualitative Analysis of Expert Interviews. JMIR Med Educ. 2023, 9, e46428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bearman, M.; Ajjawi, R. Avoiding the dangers of generative AI in assessment. Med. Educ. 2023, 57, 623–625. [Google Scholar]

- Shoja, M.M.; Van de Ridder, J.M.M.; Rajput, V. The Emerging Role of Generative Artificial Intelligence in Medical Education, Research, and Practice. Cureus 2023, 15, e40883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bittle, K.; El-Gayar, O. Generative AI and Academic Integrity in Higher Education: A Systematic Review and Research Agenda. Information 2025, 16, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hanawi, M.K.; Khan, S.A.; Al-Borie, H.M. Healthcare human resource development in Saudi Arabia: emerging challenges and opportunities-a critical review. Public Health Rev. 2019, 40, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Eraky, M.M.; Donkers, J.; Wajid, G.; van Merrienboer, J.J. A Delphi study of medical professionalism in Arabian countries: the Four-Gates model. Med Teach. 2014, 36 Suppl 1, S8–S16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norcini, J.; Anderson, B.; Bollela, V.; Burch, V.; Costa, M.J.; Duvivier, R.; Hays, R.; Kent, A.; Perrott, V.; Roberts, T.; et al. Criteria for good assessment. Med. Teach. 2011, 33, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Cerero, J.; Montenegro Rueda, M.; Román Graván, P.; Fernández Batanero, J.M. ChatGPT as a Digital Tool in the Transformation of Digital Teaching Competence: A Systematic Review. Technologies 2025, 13, 205–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Start from here.

- Bretag, T.; Harper, R.; Burton, M.; Ellis, C.; Newton, P.; Rozenberg, P.; Saddiqui, S.; van Haeringen, K. Contract cheating and assessment design. Stud. High. Educ. 2019, 44, 123–136. [Google Scholar]

- Kulgemeyer, C.; Riese, J.; Vogelsang, C.; et al. How authenticity impacts validity: Developing a model of teacher education assessment and exploring the effects of the digitisation of assessment methods. Z Erziehwiss. Published online. 7 June 2023. [CrossRef]

- Torre, D.M.; Schuwirth, L.W.T.; Van der Vleuten, C.P.M. Theoretical considerations on programmatic assessment. Medical Teacher, 2020, 42(2), 213-220.Systematic Review. Technologies 2025, 13, 205-230.

- Cotton, D.R.E.; Cotton, P.A.; Shipway, J.R. Chatting and cheating: Ensuring academic integrity in the era of ChatGPT. Innovations in Education and Teaching International 202461, 2, 228239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginsburg, S.; McIlroy, J.; Oulanova, O.; Eva, K.; Regehr, G. Toward authentic clinical evaluation: pitfalls in the pursuit of competency. Acad Med. 2010, 85, 780–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, M.; Kerridge, I.H.; McPhee, J.; Fairfull-Smith, H. A question of competence. Age Ageing 2000, 29, 179–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

UNESCO Guidance on Generative Artificial Intelligence in Education and Research; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2025.

- Goodwin, A.M.; Oliver, S.W.; McInnes, I.; Millar, K.F.; Collins, K.; Paton, C. Professionalism in medical education: the state of the art. Int J Med Educ. 2024, 15, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, C.; Mhlaba, T.; Stewart, K.A.; Moletsane, R.; Gaede, B.; Moshabela, M. The Hidden Curricula of Medical Education: A Scoping Review. Acad Med. 2018, 93, 648–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lempp, H.; Seale, C. The hidden curriculum in undergraduate medical education: qualitative study of medical students' perceptions of teaching. BMJ. 2004, 329, 770–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polin BA, Kay A. Academic integrity revisited: A longitudinal perspective. Nurse Educ Pract. 2022;65:103475. Cruess, R.L.; Cruess, S.R. Teaching professionalism. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 1447-1453.

- Wald, H.S. Professional identity (trans)formation in medical education: reflection, relationship, resilience. Acad Med. 2015, 90, 701–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monrouxe, L.V. Identity, identification and medical education: why should we care? Med Educ. 2010, 44, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, S.E. Postplagiarism: transdisciplinary ethics and integrity in the age of artificial intelligence and neurotechnology. Int J Educ Integr 2023, 19, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurāne-Brēmane, A. Developing Pedagogical Principles for Digital Assessment. Education Sciences 2024, 14, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saroha, S. Artificial Intelligence in Medical Education: Promise, Pitfalls, and Practical Pathways. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2025, 16, 1039–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, M.M.; Mir, G.M.; Raina, N.T.; Mir, S.M.; Mir, S.M.; Miskeen, E.; Alharthi, M.H.; et al. Application of artificial intelligence in medical education: Current scenario and future perspectives. J. Adv. Med. Educ. Prof. 2023, 11(3), 133–141. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Ethics and governance of artificial intelligence for health: Guidance on large multi-modal models; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Thurzo, A. Provable AI Ethics and Explainability in Medical and Educational AI Agents: Trustworthy Ethical Firewall. Electronics 2025, 14, 1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidener, L.; Fischer, M. Teaching AI Ethics in Medical Education: A Scoping Review of Current Literature and Practices. Perspect Med Educ. 2023, 12, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Federation for Medical Education (WFME). Global Standards for Quality Improvement; WFME: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tekian, A.; Hodges, B.D.; Roberts, T.E.; Schuwirth, L.; Norcini, J. Assessing competencies using milestones along the way. Med Teach. 2015, 37, 399–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, M.A.; Nelson, S.W.; Ramesh, S.; et al. Integrating artificial intelligence into medical education: a roadmap informed by a survey of faculty and students. Med Educ Online 2025, 30, 2531177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Zahrani, E.M.; Elsafi, S.H.; Al Musallam, L.D.; et al. Faculty perspectives on artificial intelligence's adoption in the health sciences education: a multicentre survey. Front Med (Lausanne) 2025, 12, 1663741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenk, J.; Chen, L.; Bhutta, Z.A.; et al. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet 2010, 376, 1923–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sova, R.; Tudor, C.; Tartavulea, C.V.; Dieaconescu, R.I. Artificial Intelligence Tool Adoption in Higher Education: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach to Understanding Impact Factors among Economics Students. Electronics 2024, 13, 3632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capraro, V.; Lentsch, A.; Acemoglu, D.; et al. The impact of generative artificial intelligence on socioeconomic inequalities and policy making. PNAS Nexus 2024, 3, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saudi Commission for Health Specialties. Professional Classification and Registration Manual; SCFHS: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- AlRukban, M.; Alajlan, F.; Alnasser, A.; Almousa, H.; Alzomia, S.; Almushawah, A. Teaching medical ethics and medical professionalism.

- Restini, C.; Faner, M.; Miglio, M.; Bazzi, L.; Singhal, N. Impact of COVID-19 on Medical Education: A Narrative Review of Reports from Selected Countries. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2023, 10, 23821205231218122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, R.; Mansour, A.E.; Fadda, W.A.; et al. The sudden transition to synchronized online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia: a qualitative study exploring medical students' perspectives. BMC Med Educ. 2020, 20, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Muhanna, F.A.; Subbaroa, V.V. Standards in medical education and gcc countries. J Family Community Med. 2003, 10, 15–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garzón, J.; Patiño, E.; Marulanda, C. Systematic Review of Artificial Intelligence in Education: Trends, Benefits, and Challenges. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2025, 9, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forouzadeh, M.; Kiani, M.; Bazmi, S. Professionalism and its role in the formation of medical professional identity. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2018, 32, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zidjali, L.M.; Chiang, K.H.; Macleod, H. Perception and experiences of senior doctors involved in clincal teaching for Oman's medical education sector. BMC Med Educ. 2025, 25, 1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsahafi, Z.; Baashar, A. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Related to Artificial Intelligence Among Medical Students and Academics in Saudi Arabia: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2025, 17, e83437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salem, M.A.; Zakaria, O.M.; Aldoughan, E.A.; Khalil, Z.A.; Zakaria, H.M. Bridging the AI Gap in Medical Education: A Study of Competency, Readiness, and Ethical Perspectives in Developing Nations. Computers 2025, 14, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).