Submitted:

13 January 2026

Posted:

13 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Increased Use of Smartphones Among Children

- Nine in 10 children own a mobile phone by the time they reach the age of 11.

- Three-quarters of social media users aged between eight and 17 have their own account or profile on at least one of the large platforms.

- Despite most platforms having a minimum age of 13, six in 10 children aged 8 to 12 who use them have signed up with their own profile.

- Almost three-quarters of teenagers between the ages of 13 and 17 have encountered one or more potential harms online.

- Three in five secondary school-aged children have been contacted online in a way that potentially made them feel uncomfortable.

- About 19% of children aged 10-15 years old, exchanged messages with someone online whom they had never met before in the last year.

- Over 9,000 child sexual abuse offences involved an online element in 2022/23.

- Around a sixth of people who experienced online harassment offences were under 18 years old.

- Under 18-year-olds were the subject of around a quarter of reported offences of online blackmail in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland.

- There were around 107,000 offences reported in 2022, a 7.6% increase compared to 2021, nearly quadruple what they were 10 years ago. Evidence continues to suggest many crimes remain unreported.

- About 75% of CSAE offences relate to sexual crimes committed directly against children, and around 25% relate to online offences of Indecent Images of Children.

- The crime types regarding CSAE are changing. For example, historically, Child-on-Child abuse accounted for around a third of offences. The data in the report suggests that today, this is just over half.

- CSAE within the family environment remains a common form of reported abuse, accounting for an estimated 33% of reported contact CSAE crime. Parents and siblings were the two most common relationships featured.

- Group-based CSAE accounts for 5% of all identified and reported CSAE, ranging from unorganized peer group sharing of imagery to more organized, complex, high-harm cases with high community impact.

- Reported CSAE is heavily gendered, as expected, with males (82% of all CSAE perpetrators) predominantly abusing females (79% of victims). Sexual offending involving male victims is more common in offences involving indecent images and younger children.

- The number of recorded incidents of Online Sexual Abuse continues to grow, and it accounts for at least 32% of CSAE.

- About 52% of all CSAE cases involved reports of children (aged 10 to 17) offending against other children, with 14 being the most common age.

2. State of the Art

2.1. Incidents of Child Online Sexual Exploitation and Abuse

3. Approach

4. Implementation

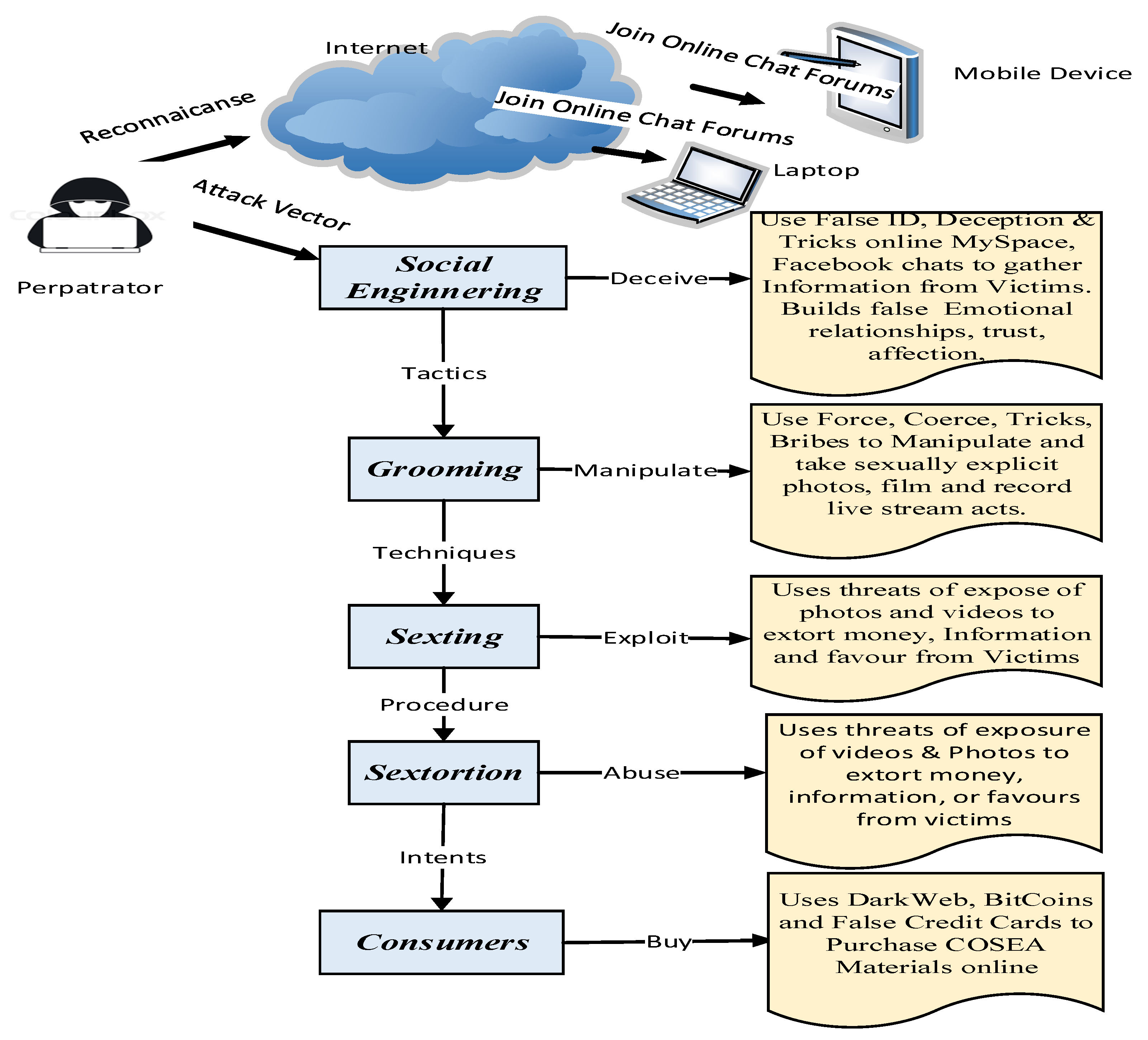

4.1. Tactic Techniques and Procedures (TTP) Used by Perpetrators on Victims

- Tactics: The perpetrator carries out reconnaissance on various social network sites, video game consoles, and online chat forums to identify the victims. Then the threat actor uses a social engineering method to gather information or passwords from victims. The online platforms and live streaming websites include MySpace, Facebook, instant messaging, pop-ups, chat rooms, and other internet forums to identify their victims for possible child sexual exploitation and abuse. Additionally, threat agents communicate with other agents in a campaign using online tools such as the Dark Web and Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) to leverage attacks and conceal their identities [50,56].

- Techniques: do the perpetrators adopt the strategies to facilitate the initial contact with the victim before the exploitation, such as social engineering, online grooming, sexting, sextortion, and other capabilities deployed? For instance, after the adversary establishes contact with the victim online, they may go on to deceive the victim or use force, coercion, bribes, and other persuasive means to trick the victim into personally divulging information that could lead to further exploitation [50,56].

- Procedures: include a set of tactics and techniques put together that the adversary uniquely uses to perform an attack. The procedures for each exploitation may vary depending on the nature of the abuse, purpose, and the money involved. A well-orchestrated procedure may not show any sign of exploitation or abuse. For instance, the perpetrator may decide to use the internet, a webcam to capture images and film the explicit sexual abuses on the children, and may choose to live stream the abuses to an audience in a private online forum [50,56].

4.2. COSEA Attack Steps Deployed by Perpetrators to Exploit Victims Online

- Reconnaissance: The Perpetrator carries out online searches and visits various online forums to identify which platforms they can join and conceal themselves and identify vulnerable children.

- Social Engineering or Catfishing: The perpetrator uses a false identity and tricks the child into revealing personal information about themselves and their families.

- Grooming: Perpetrators use deception to gather intelligence about the child to build emotional relationships, trust, and affection to manipulate, exploit, and abuse the victims later.

- Sexting: Perpetrators use force, bribes, tricks, and persuasion to get the victims online and into sexually explicit acts. They connect via smartphones with webcams to share sexually explicit photos, images, and live streaming of themselves and the child inappropriately online.

- Sextortion: Perpetrators use the threat to extort money, information, or sexual favours from their victims by threatening to reveal the sexually explicit activities they have secretly recorded unlawfully on social media.

- Consumers: They purchase COSEA materials online using false Credit Card details on the Dark Web and Bitcoins.

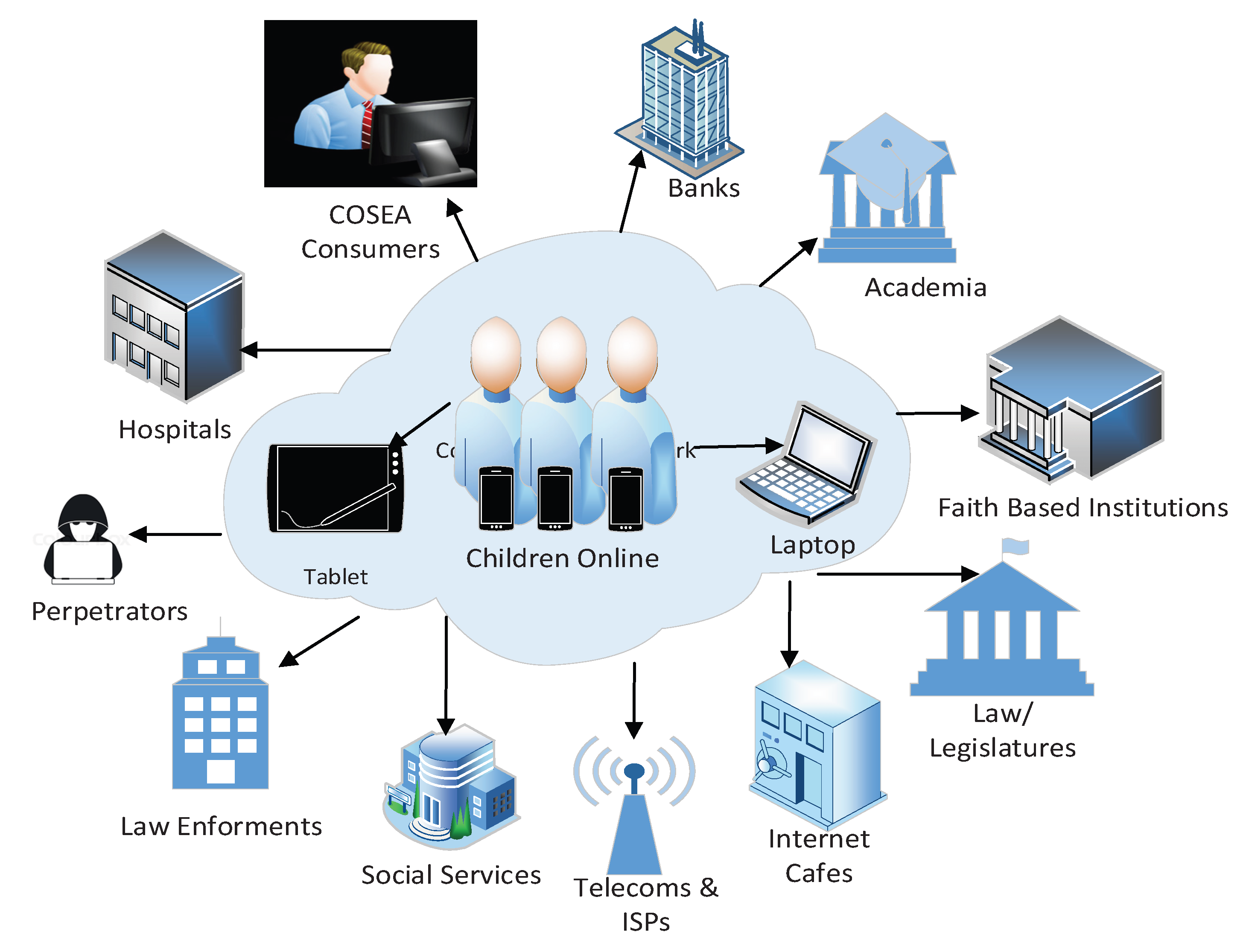

5. Discussions on Child-Centred Approach to COSEA and the Influencing Factors

5.1. Child Online Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (COSEA) Challenges

5.2. Child-Centred Approaches to Factors that Influence COSEA Challenges

- Perpetrators: The perpetrators are more IT savvy and understand their cultural demographics and target groups (Radford et al., 2011) (Radford et al., 2018) [35,51]. They know the domains, search engines, dark web, deep web, digital currencies, cloud, and social media platforms used to target victims. In addition, the perpetrator can use anonymized software and end-to-end encryption to cover their tracks. Thus, they can pseudonymize themselves, carry out reconnaissance, target their victims using social media, groom, exploit, and abuse using webcams to film and take pictures, and cover their tracks. WeProtect Global Alliance [52], proposed a six stage model for national response to critical elements for protecting children including, Legislation and Policy Frameworks to address OCEA, Prevention Strategies required to raise awareness, Equip Law Enforcement agencies with the necessary skills to carry out investigations, Collaborations with Private Sector to implement safety measures, Data Collection and Research to inform policy decisions and information sharing, and finally Victim Support Services for the victims and families [52]. However, implementing this model will be challenging as it does not address the key issues of understanding the methods, opportunities, and motives of the perpetrators and the TTPs they deploy on their victims.

- Consumers: Consumers are mainly users of COSEA materials. They are willing to pay a lot of money to the perpetrators, parents, third-party agencies, and individuals for these sexually explicit materials. The methods used to exchange money include Mobile Money, Credit cards, online transfers, cash, and others. Thus, the consumer could be ordinary individuals, faith leaders, teachers, groups, or young people. Identifying consumers of these sexually explicit materials has been one of the significant challenges, as they use threats and secrecy to maintain anonymity [62].

- Parents and Guardians: Parental guidance provides a safeguarding environment for children and young persons, especially during online activities. Several approaches emphasize how illegal activities lead to direct contact with predatory COSEA cybercrimes. These are motivated offenders, suitable targets, and a capable guardian’s absence to prevent these cybercrimes [63]. First, provide parents with education on the risks, dangers, and impact of COSEA on children. The awareness will help parents have open discussions about the risks of visiting certain websites. How it may impact their wellbeing, talk to their children about online safety, set time limits, and help them make better online and offline choices. Organizing Training and workshops for parents will orient them to the mobile device’s safety features and to how to monitor and use parental controls to safeguard their children and detect any signs of exploitation or abuse. Further, the parents will know the importance of using strong passwords and how to set them, restrict device privacy settings so that apps cannot access them, and turn off webcams and geolocation on the devices. Those awareness forums will create trust among parents and authorities and provide information-sharing and reporting platforms.

- Cyber or Internet Cafes: Cyber or Internet cafes provide fast internet facilities and computers for users who may not have smartphones, tablets, and laptops at their disposal due to financial challenges. Most children and young people are not taken to or picked up from school at a certain age, as considered grown-ups, and most of their parents may be working by the time they leave school. These children go to cybercafés after school, pay, and access the internet, making them vulnerable to perpetrators. The victims end up accessing pornographic materials on websites and chat forums, clicking on pop-ups that take the victims to exploitative websites, and watching sexually explicit cartoons and videos. The cybercafé owners may be aware of the dangers of exposing these young children to these websites. However, they depend on the payments from these children and young persons, or victims, to keep their business going. That has caused the various disparities between the cybercafé owners, regulatory bodies, and law enforcement agencies in censoring the cybercafé owners who are not installing, configuring, filtering, and blocking these sexually explicit materials exposed to the victims. Inadequate enforcement has caused many challenges, as most are aware of the dangers but have looked the other way for economic and business reasons.

- Social Services: The social services institutions have the overall responsibility of overseeing the well-being of children and parents in terms of providing support, education, and awareness of the issues of COSEA. Identifying what is required to avoid forming any preconceptions regarding the child’s feelings is essential [16]. For instance, social care practitioners in the UK need to make legal and ethical decisions to ensure the child’s well-being and safeguarding online, in line with the legal frameworks under Section 17 of the Children’s Act 1989. The challenge of promoting the child’s welfare and protection, including not being sensitive to their feelings and emotions, can prove counterproductive.

- Hospitals: The hospitals are one of the key places victims will visit after experiencing any form of exploitation and abuse. Thus, legal institutions could help establish appropriate channels for medical practitioners and health workers to report such cases. However, these health workers may encounter legal and ethical challenges, including data protection and patient confidentiality.

- Youth Intervention Groups and NGOs: Child online sexual exploitation and abuse have been recognized globally as a significant factor impacting children’s mental and physical health. Other factors include socio-psychological, socio-sexual, and socio-religious well-being, and the risk of getting involved in crime and drugs to fund such behaviors. Thus, bringing together the youth intervention groups to brainstorm and discuss the various COSEA issues on how to detect, intervene, mitigate, and promote COSEA awareness is paramount in eradicating the challenges with young people at risk. In addition, there are Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and other organizations such as UNICEF, UNESCO, WHO, and INTERPOL that can assist in promoting awareness.

- Faith-Based Organizations and Religious Leaders: Society thrives on faith-based communities, religious leaders, and activists for advocacy, moral guidance, spiritual strength, advice, growth, a strong moral compass, and social well-being. Parents and families entrust their children to these faith-based and religious leaders with absolute confidence that their children’s lives are in safe hands. Faith-based organizations and religious leaders can assist in information sharing and mitigating child online exploitation and abuse with authorities. However, history has shown that this has not been the case, as these religious leaders are not well-engaged in the fight to understand the risks and consequences of COSEA. Faith-based and religious leaders require education, awareness, detection mechanisms, and support from national and international organizations to spearhead the fight against COSEA and offer safety for victims. There has to be effective national and international collaboration, cooperation, and coordination of resources with UNICEF, UNODC, WHO, and UNESCO, as well as with faith-based leaders, to protect victims. Society should look up to these religious leaders and report any exploitations, abuses, and stigma on the victims.

- Education and Awareness: The inadequate amount of education and awareness on the issues of COSEA in most nations and cultures, schools, among teachers, faith-based activities, the media, and research institutions are significant factors [15]. Currently, ongoing projects spearheaded by these empowerment initiatives, in collaboration with UNICEF, NGOs, and governmental agencies, have not brought together all nations to fight COSEA cybercrime [42]. There is minimal effort in providing research funding for the subject area. COSEA issues, although internationally acclaimed, are more jurisdictional and cultural, depending on how each society thinks and does things. Thus, the emphasis must be placed not only on funding for other continents but also on local context and expert judgment. Children’s rights to be heard and educated regarding the use and abuse of the internet are not adhered to and prioritized.

- Telecommunications Industries and Internet Service Providers (ISPs): The telecommunications industries and ISPs provide internet access to all users, including MSN, Facebook, Instagram, and other social networking sites. Therefore, they can provide tools to monitor, detect, and manage any online child activities. However, technological and different approaches used for detection, intervention, and interception have significantly protected children online. Factors such as a lack of cybersecurity tools configured to detect cyber threats and child online activities automatically, and to block these behaviors, are not available to most ISPs, law enforcement agencies, mobile users, and victims at large. Moreover, there is inadequate government support, a lack of expertise in the subject area, and inadequate digital forensics investigators, laboratories, and tools to investigate such cybercrime cases. That includes identifying steganography materials, image analysis, and identifying activity patterns. Lack of reporting platforms and fear of intimidation by offenders have also prevented intelligence gathering. These have led to increased COSEA vulnerabilities, exploits, abuse, and obfuscation.

- Banks and Financial Institutions: Banks and other financial institutions have a significant role in monitoring and reporting any illegal and suspicious financial activities online. These industries are out to make money, and their existence depends mainly on financial sustainability. However, the need to bring together the various credit card companies to understand the impact of COSEA, the socio-economic factors, and the socio-psychological effects on children and society is pertinent. Further, the banking industry could form a coalition with the mobile money industry and law enforcement agencies to identify these transactions, block the activities, and share information to track the trails of perpetrators and consumers.

- Law Enforcement Agencies: The law enforcement agencies have a significant role to play in arresting, investigating, and sending perpetrators to court for prosecuting COSEA crimes. That requires better cooperation among law enforcement agencies, NGOs, and industry for strategic planning and safety awareness. Further, inadequate coordination among national and international law enforcement agencies, financial institutions, ISPs, and social services has heightened COSEA, especially in forensic investigations [62]. Furthermore, there has been inadequate cooperation among the agencies and victims in reporting and combating these cyberthreats as perpetrators use aliases and pseudonymization techniques to trick the victims, groom them online and offline, and obfuscate to prevent arrest and prosecution. Moreover, law enforcement agencies need a legal framework that provides clear legal ramifications to support their roles and responsibilities in implementing, enforcing, arresting, and investigating online child exploitation. Lack of expertise is also a significant factor in the gathering of cyber threat intelligence and in digital forensic investigations.

- Laws and Regulatory Frameworks: Laws and Regulatory frameworks exist nationally and internationally regarding COSEA [63]. For instance, the UK Online Safety Act 2023 requires social media companies to quickly remove any illegal content, such as child sexual abuse material and grooming, or prevent it from appearing online. To prevent children from accessing harmful content online, including content that encourages, promotes, or provides instructions for suicide, self-harm, eating disorders, bullying, and violent content. To use or configure age-checking mechanisms and measures to prevent children’s access to pornographic material and other age-inappropriate content. However, implementing these laws and legislature has proved challenging due to inadequate enforcement mechanisms, poor interpretations of the laws, and a lack of collaboration among law enforcement agencies and the courts [40]. Some efforts have been made to combat COSEA, and some controls have been implemented to address the issues. For instance, the CoE Lanzarote [21,44] and the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child provide comprehensive benchmarks that highlight the need to address COSEA. In addition, WeProject and the ECPTA International organized an annual human capacity-building workshop on child online safety in Malawi in 2016 to create awareness of child online exploitation. Legal frameworks such as the Convention on the Rights of the Child. Cyber Security & Personal Data Protection (2014) provides regulatory measures. However, all these efforts from the various countries lack coordination, coalitions, and corporations that consider the perpetrators’ tactics, techniques, and procedures to exploit and abuse children online. Hence, the increase in child online exploitation and abuse challenges has led to the need for regular child online safety initiatives.

6. Recommendations

7. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Joleby, M.; Landström, S.; Lunde, C.; Jonsson, L. S. Experiences and psychological health among children exposed to online child sexual abuse – A mixed methods study of court verdicts. In *Psychology, Crime & Law*; 2021; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittle, H.; Hamilton-Giachritsis, C.; Beech, A. R.; Collings, G. A review of young people’s vulnerabilities to online grooming. *Aggression and Violent Behavior* 2013, vol. 18, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloess, J. A.; Beech, A. R.; Harkins, L. Online child sexual exploitation: prevalence, process, and offender characteristics. *Trauma, Violence & Abuse* 2014, vol. 15(no. 2), 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Internet Watch Foundation. Trends in online child sexual exploitations: Examining the distributions of captures of live-stream child sexual abuse. 2018. Available online: https://www.iwf.org.uk.

- NSPCC. What is child sexual exploitation? 2020. Available online: https://www.nspcc.org.uk/what-is-child-abuse/types-of-/child-sexual-exploitation/.

- Hamilton-Giachritsis, C.; Hanson, E.; Whittle, H.; Alves-Costa, F.; Beech, A. Technology-assisted child sexual abuse in the UK: Young people’s views on the impact of online sexual abuse. *Children and Youth Services Review* 2020, vol. 119, 105451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloess, J. A.; Hamilton-Giachritsis, C. E.; Beech, A. R. Offence processes of online sexual grooming and abuse of children via internet communication platforms. *Sexual Abuse* 2019, vol. 31(no. 1), 73–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivagurunathan, M.; Orchard, T.; Evans, M. Barriers to utilisation of mental health services amongst male child sexual abuse survivors: Service providers’ perspective. *Journal of Child Sexual Abuse* 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurtele, S. A. Preventing sexual abuse of children in the twenty-first century: Preparing for challenges and opportunities. *Journal of Child Sexual Abuse* 2009, vol. 18(no. 1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M Naebklang, *The Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children in Africa*; ECPAT International: Ghana, 2014; Available online: https://www.ecpat.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Regional%20CSEC%20Overview_Africa.pdf (accessed on Apr. 18 2025).

- Palmer, T.; Digital Dangers. The Impact of Technology on the Sexual Abuse and Exploitation of Children and Young Persons*. Barnardo’s, 2015. Available online: https://www.celcis.org/files/5715/4871/8578/Barnardos_2015_Digital_Dangers_The_impact_of_technology_on_the_sexual_abuse_and_exploitation_of_children_and_young_people.pdf.

- Fry, D.; Krzeczkowska, A.; Ren, J.; Lu, M.; Fang, X. and the Into the Light Index Study Group, Prevalence estimates and nature of online child sexual exploitation and abuse: a systematic review and meta-analysis. *Lancet Child & Adolescent Health* 2025, vol. 9(no. 3), 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramiro, L. S.; Martinez, A. B.; Tan, J. R. D.; Mariano, K.; Miranda, G. M. J.; Bautista, G. Online child sexual exploitation and abuse: A community diagnosis using the social norms theory. *Child Abuse & Neglect* 2019, vol. 96, 104080. [Google Scholar]

- Kloess, J. A.; Woodhams, J.; Whittle, H.; Grant, T.; Hamilton-Giachritsis, C. E. The challenges of identifying and classifying child sexual abuse material. In *Sexual Abuse*; 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefevre, M.; Hickle, K.; Luckock, K.; Ruch, G. Build trust with children and young people at risk of child sexual exploitation: The professional challenge. *British Journal of Social Work* 2017, vol. 47, 2456–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallett, S. An Uncomfortable Comfortableness’: ‘Care’, child protection and child sexual exploitation. *British Journal of Social Work* 2016, vol. 46(no. 7), 2137–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westendorf, J.-K.; Searle, L. Sexual exploitation and abuse in peace operations: trends, policy responses and future directions. *International Affairs* 2017, vol. 93(no. 2), 365–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demetris, D. S.; Kietzmann, J. Online child sexual exploitation: a new MIS challenge. *Journal of the Association for Information Systems* 2021, vol. 22(no. 1), 5–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merdian, H. L.; Perkins, D. E.; Dustagheer, E.; Glorney, E. Development of a case formulation model for individuals who have viewed, distributed, and/or shared child sexual exploitation material. *International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology* vol. 64(no. 10–11), 1055–1073. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quayle, E. Prevention, disruption and deterrence of online child sexual exploitation and abuse. *ERA Forum* 2020, vol. 21, 429–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Almagor, R. Online child sex offenders: Challenges and countermeasures. *The Howard Journal of Criminal Justice* 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, M.; Synnott, J.; Reynolds, A.; Pearson, J. A comparison of online and offline grooming characteristics: An application of the victim roles model. *Computers in Human Behavior* 2018, vol. 85, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WeProtect Intelligence Brief, “Impact of COVID-19 on child sexual exploitation,” Global Alliance Intelligence Brief, 2020. Available online: https://www.alliancecpha.org/en/system/tdf/library/attachments/impactofcovid-19ononlinechildsexualexploitation.pdf?file=1&type=node&id=38359.

- Keller, M. H.; Dance, G. J. X. “Preying on children: The emerging psychology of pedophiles,” *The New York Times*, Sept. 29, 2019. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/29/us/pedophiles-online-sex-abuse.html.

- Brewster, T. “Child exploitation complaints rise 106% to hit 2 million in just one month: Is COVID-19 to blame,” *Forbes*, Apr. 24, 2020. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/thomasbrewster/2020/04/24/child-exploitation-complaints-rise-106-to-hit-2-million-in-just-one-month-is-covid-19-to-blame/#6e8116d54c9c.

- Interagency Working Group, Trafficking definitions for working group. 2019. Available online: https://www.ispcan.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Trafficking-definitions-for-working-group-merged.pdf.

- CHILDLIGHT Global Child Safety Institute. 2024. Available online: https://www.childlight.org/newsroom/over-300-million-children-a-year-are-victims-of-online-sexual-exploitation-and-abuse.

- NSPCC. “Statistics briefing: Online harm and abuse,” OFCOM, 2024. Available online: https://learning.nspcc.org.uk/media/obfg0phz/online-harm-and-abuse-statistics-briefing.pdf.

- Finkelhor, D.; Turner, H.; Colburn, D. Prevalence of online sexual offenses against children in the US. *JAMA Network Open* 2022, vol. 5(no. 10), e2234471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WeProtect Global Alliance. World’s first estimate of the scale of online child sexual exploitation and abuse. 2024. Available online: https://www.weprotect.org/blog/worlds-first-estimate-of-the-scale-of-online-child-sexual-exploitation-and-abuse/.

- National Police Chiefs’ Council. “Vulnerability Knowledge and Practice Programme (VKPP): National analysis of police-recorded child sexual abuse and exploitation crimes report 2022,” 2024. Available online: https://news.npcc.police.uk/releases/vkpp-launch-national-analysis-of-police-recorded-child-sexual-abuse-and-exploitation-csae-crimes-report-2022.

- UN Office on Drugs and Crime. Online child sexual exploitations and abuses: Promoting a culture of lawfulness. 2020. Available online: https://www.unodc.org/e4j/en/cybercrime/module-12/key-issues/online-child-sexual-exploitation-and-abuse.html.

- PureSight Online Child Safety, Online predators statistics. 2018. Available online: https://www.puresight.com/Pedophiles/Online-Predators/online-predators-statistics.html.

- Palmer, E.; Foley, M. ‘I have my life back’: Recovering from child sexual exploitation. *British Journal of Social Work* 2017, vol. 47(no. 4), 1094–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford, L.; Bradley, S.; Fisher, C.; Bassett, H.; Howat, C.; Collishaw, N.; Carol, C. “Child abuse and neglect in the UK today,” NSPCC, London. 2011. Available online: https://learning.nspcc.org.uk/media/1042/child-abuse-neglect-uk-today-research-report.pdf.

- Kloess, J. A.; Seymour-Smith, S.; Hamilton-Giachritsis, C. E.; Long, M. L.; Shipley, D.; Beech, A. R. A qualitative analysis of offenders’ modus operandi in sexually exploitative interactions with children online. *Sexual Abuse* 2017, vol. 29(no. 6), 563–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demetris, D. S.; Kietzmann, J. Online child sexual exploitation: a new MIS challenge. *Journal of the Association for Information Systems* 2021, vol. 22(no. 1), 5–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, K. K. R.; Choo, K. R.; Hillman, H.; Hooper, C. Online child exploitation: challenges and future research directions. *Computer Law and Security Review* 2014, vol. 30(no. 6), 687–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laws, S.; Hall, G. Addressing child sexual abuse and exploitation: Improvement in understanding and practice. *Child Abuse Review* 2019, vol. 28, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baines, V. Council of Europe baseline mapping: Building Europe for and with children. 2019. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/191120-baseline-mapping-web-version-3-/168098e109.

- Quayle, E. “Researching online sexual exploitations and abuse: Are there links between online and offline vulnerabilities?” *Kids Global Online*, University of Edinburgh; 2016; Available online: https://www.research.ed.ac.uk/portal/files/59858120/Guide_7_Child_sexual_exploitation_and_abuse_Quayle.pdf.

- ECPAT. Online child sexual exploitation: A common understanding. 2017. Available online: http://www.ecpat.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/SECO-Booklet_ebook-1.pdf.

- Salter, M.; Hanson, E. I need you all to understand how pervasive this issue is: User efforts to regulate child sexual offending on social media. In *The Emerald International Handbook of Technology-Facilitated Violence and Abuse*; Bailey, J., Flynn, A., Henry, N., Eds.; Emerald Publishing: Bingley, 2021; pp. 729–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. How do we prevent and combat online child sexual exploitation and abuse: New Council of Europe mapping and comparative review of mechanisms for collective action. 2019. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/children/-/how-do-we-prevent-and-combat-online-child-sexual-exploitation-and-abuse-.

- Bailey, J.; Henry, N.; Flynn, A. “Technology-facilitated violence and abuse: International perspectives and experiences,” in *The Emerald International Handbook of Technology-Facilitated Violence and Abuse*; Bailey, J., Flynn, A., Henry, N., Eds.; Emerald Publishing: Bingley, 2021; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espelage, D. L.; Hong, J. S. Cyberbullying prevention and intervention efforts: Current knowledge and future directions. *Canadian Journal of Psychiatry* 2017, vol. 62(no. 6), 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sexual Offences Act 2003, United Kingdom, 2003. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2003/42/pdfs/ukpga_20030042_en.pdf.

- MITRE, *ATT&CK: Ten reconnaissance techniques*. 2025. Available online: https://attack.mitre.org/.

- Daszczyszak, R.; Ellis, D.; Luke, S.; Whitley, S. MITRE TTP-based hunting. MITRE. 2019. Available online: https://www.mitre.org/sites/default/files/2021-11/prs-19-3892-ttp-based-hunting.pdf.

- Azeria Labs, Tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs). 2017. Available online: https://azeria-labs.com/tactics-techniques-and-procedures-ttps/.

- Radford, L. A review of international research on interpersonal violence*, Centre of Expertise on Child Sexual Abuse, University of Central Lancashire, Barbados, Essex. 2018. Available online: http://clok.uclan.ac.uk/21733/1/CSA%20international%20survey%20methodology.pdf.

- WeProtect. Preventing and tackling child sexual exploitation and abuse (CSEA): A model national response. 2015. Available online: https://www.weprotect.org/the-model-national-response/.

- Benson, I. R.; Benson, M. J. Challenging online behaviours of youth: Findings from a comparative analysis of young people in the United States and New Zealand. *Social Science Computer Review* 2005, vol. 23(no. 1), 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berelowitz, S.; Clifton, J.; Firmin, C.; Gulyurtlu, S.; Edwards, G. If only someone had listened: Office of the Children’s Commissioner’s inquiry into child sexual exploitation in gangs and groups: Final report*; Office of the Children’s Commissioner: London, 2013; Available online: https://www.childrenscommissioner.gov.uk/wpcontent/uploads/2017/07/If_only_someone_had_listened.pdf.

- Kloess, J. A.; Seymour-Smith, S.; Hamilton-Giachritsis, C. E.; Long, M. L.; Shipley, D.; Beech, A. R. A qualitative analysis of offenders’ modus operandi in sexually exploitative interactions with children online. *Sexual Abuse* 2015, vol. 29(no. 6), 563–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnum, S. “Standardizing cyber threat intelligence information with the structured threat information expression (STIX), v1.1, revision 1,” 2014. Available online: http://stixproject.github.io/about/STIX_Whitepaper_v1.1.pdf.

- Chiang, E. “Dark web: Study reveals how new offenders get involved in online paedophile communities,” Institute for Forensic Linguistics, Aston University. 2020. Available online: https://theconversation.com/dark-web-study-reveals-how-new-offenders-get-involved-in-online-paedophile-communities-131933.

- P Rook, *Prosecuting sexual offences*. JUSTICE. 2019. Available online: https://files.justice.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/06170149/Prosecuting-Sexual-Offences-Report.pdf.

- Williams, R.; Elliott, I. A.; Beech, A. R. Identifying sexual grooming themes used by internet sex offenders. *Deviant Behavior* 2013, vol. 34, 135–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Haykal, H. A.; Youssef, E. Child sexual abuse and the internet—A systematic review. In *Human Arenas*; 2023; vol. 6, pp. 404–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Human Rights, *Convention on the rights of the child*, 1989. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CRC.aspx.

- Holt, T. J.; Cale, J.; Leclerc, B.; Drew, J. “Assessing the challenges affecting the investigative methods to combat online child exploitation material offences,” *Aggression and Violent Behavior*. British Journal of Social Work 2020, vol. 55, 101464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vold, G. B.; Bernard, T. J.; Snipes, J. B. *Theoretical Criminology*; Oxford University Press: New York, 2002; Available online: http://www.ncjrs.gov/App/publications/abstract.aspx?ID=175350.

- Choi, K. S.; Lee, H. The Trend of Online Child Sexual Abuse and Exploitation: A Profile of Online Sexual Offenders and Criminal Justice Response. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse 2023, 33(6), 804–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quayle, E. Prevention, disruption and deterrence of online child sexual exploitation and abuse. ERA Forum 2020, 21, 429–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stakeholders | Roles and Responsibilities | Strategic Management Initiatives |

|---|---|---|

| Law and Legislature | National & International Laws | Implement laws that supports all stakeholders’ initiatives |

| Telecom Industries & ISPs | Set Standards and Directives. Understand Perpetrator motives ad intents. | Implement standards, policies, configuration tools & triggers to detect, report and prevent. |

| Law Enforcement Agencies | Employ expertise with understanding of COSEA threats | International Collaborations & Information sharing, Organize Training & Workshops. Set up forensic labs. |

| Banks & Financial Institutions | Report any financial irregularities and transfers | Banks Form Coalitions to detect and support international COSEA initiatives |

| Internet & Cyber Cafes | Install IDS/IPS, Firewalls and Anti malwares to detect sexually explicit materials | Sep up enforcement regulators to monitor cafes. Implement licenses and security policies |

| Social Services | Provide Social Care, Education, and support parents and children. | Organize Training & Workshops to educate staff and create awareness of risk factors |

| Faith Based leaders | Provide Moral & Spiritual Guidance to children and families in social settings | Organize Forums that brings sensitizations, collaborations, corporations, trust and reporting platforms. |

| NGOs & Interventions Groups | Promote awareness and interventions between victims and state institutions | Liaise with global agencies to promote the wellbeing of victims |

| Academia/Research Institutions | Provide Research Initiatives in the COSEA subject areas. Train teachers to be aware of risk factors and impact on children | Provide funding for research that provide threat intelligence and situational awareness for all stakeholders |

| Hospitals | Gather health issues pertaining to victims and risk factors | Provide statistics to Government institutions with health and risk factors for policy formulation |

| Parents & Guardians | Provide parental guidance, protection and support for children and young persons | Provide governmental support for Social Services, Hospitals, teachers, faith leaders, and law enforcement agencies to educate parents and guardians |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).