1. Introduction

1.1. Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI): Definition, Prevalence, and Biomechanics

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) is a significant global public health concern with major medical, social, and economic impacts. It substantially contributes to worldwide mortality and disability. TBI results from an external force causing temporary or permanent cognitive, physical, or psychosocial impairment [

1]. Mechanical energy is transferred to the head by events such as direct impact, penetrating injury, or rapid acceleration and deceleration of the brain within the skull. In 2021, there were 20.84 million new and 37.93 million existing TBI cases globally [

2]. Estimates vary, but TBI is widely recognized to affect over 50 million people annually and account for 30-40% of all injury-related deaths worldwide [

3,

4].

Epidemiological patterns show that TBI varies importantly based on the geography, socioeconomic context, age, and sex. In low- and middle-income countries, road traffic collisions account for most of the cases. However, in higher-income countries, most TBIs are caused by falls, particularly in the older population with other comorbidities [

3]. Sports-related concussions and military blast exposures contribute importantly to the incidence of TBI [

5]. In most settings, young males experience a disproportionately high incidence of TBI due to high-risk-taking activities, whereas older adults are particularly susceptible due to age-related vulnerability and increased likelihood of falls [

6].

At the biomechanical level, TBI results from the interplay between external forces applied and the individual brain tissue properties. When the head undergoes normal movements such as rotation, the brain is protected from potential damage by the cushioning effect of the meninges and the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) [

7]. The brain has viscoelastic properties, suggesting that its deformation under stress conditions is both time-dependent and non-linear [

8]. Under high strain rates, as they occur during high-energy impacts or blast exposures, brain tissue shows marked stiffness and behaves mechanically in a distinct manner from the one observed under gradual loading [

9,

10]. The type of forces developed during head trauma, namely shear, tensile, and compressive, produces heterogeneous patterns of brain tissue damage that affect cortical and subcortical junctions, the corpus callosum, and deep white matter pathways, and relies on the direction, magnitude, and duration of impact [

11].

Among the manifestations of these biomechanical forces, diffuse axonal injury (DAI) is considered one of the most critical. Unlike focal lesions or hematomas, DAI is a hallmark of rotational acceleration and deceleration injuries, where the shear and torsional forces that develop cause disruption of the axonal integrity, especially in deeper structures such as the corpus callosum, brainstem, and white matter tracts [

12]. At the microscopic level, axonal injury is initiated by mechano-transduction pathways, including microtubule disruption, axolemmal damage, and axonal transport failure, which leads to secondary swelling and disconnection [

13]. These pathological cellular processes are accompanied by the accumulation of proteins such as amyloid precursor protein and tau, which may lead to neurodegenerative diseases [

14].

1.2. Classification of TBI (Severity, Type, Temporal Phases)

There are several ways to classify a TBI, based on injury severity, neuroimaging, pathophysiology, prognostic models, or the duration of retrograde amnesia [

15]. One of the most widely preferred methods to determine the severity of injury is the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), first introduced in 1974, used as a clinical tool to evaluate the patient’s level of consciousness through eye, motor, and verbal responses [

2,

16]. Based on GCS, traumas are categorized as mild (scores 13-15), moderate (scores 9-12), or severe (scores 3-8). However, this classification system has several limitations, since it does not account for the underlying pathology, as patients with divergent imaging findings may present with smaller scores. To address this issue, an updated framework definition was proposed by Manley et al, 2025 [

17]. This recent revision promotes a four-pillar system including clinical examination (GCS with pupillary reactivity), biomarkers (blood-based assays), imaging (structural and functional measures), and modifiers (patient-specific factors that influence outcomes). This Clinical, Biomarker, Imaging Modifiers (CBI-M) framework provides a more holistic approach to the TBI classification.

TBI can also be classified based on injury type, which is divided into focal and diffuse lesions. Focal injuries are typically characterized by localized structural damage such as contusions, hematomas, and penetrating lesions, most often confined to cortical regions [

18]. In contrast, diffuse injuries present with widespread disruption of axonal networks and microvascular structures across multiple brain areas [

19]. Diffuse Axonal Injury (DAI) is a characteristic pathology, resulting from shear and tensile forces generated during rapid acceleration and deceleration or rotational movements of the head [

20]. In clinical presentation, both focal and diffuse widespread injury mechanisms often co-exist.

Another significant classification is based on the temporal evolution. The primary injury occurs at the moment of the impact and reflects the immediate mechanical disruption of neurons, glia, and vasculature [

21]. As a result, the research focus is on the secondary injury cascade, which starts from minutes to years post-trauma. While primary injury can be mitigated through preventative measures, namely helmets, seat belts, it is not amenable to direct medical intervention [

22]. Acute secondary injury events unfold with blood-brain barrier (BBB) breakdown, edema, hemorrhage, excitotoxicity, and hypoperfusion [

23]. Over subsequent days to weeks, progressive mechanisms such as oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, axonal degeneration, and neuroinflammation lead to cellular loss [

24]. In the chronic phase, these mechanisms converge on persistent neurodegeneration characterized by abnormal protein aggregation, synaptic dysfunction and long-term cognitive and behavioral decline, features that overlap with neuropathological hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) [

25]. Beyond neuropathology, TBI represents the most prevalent neurological disorder worldwide and is associated with a broad spectrum of persistent symptoms. Survivors experience enduring cognitive deficits, emotional and behavioral disturbances, and somatomotor impairments that persist for years after the initial insult [

26]. Sleep disturbances are common in patients experiencing insomnia, hypersomnia, and poor sleep quality than in the general population [

27]. Understanding these temporal and pathological dimensions of TBI is crucial for mapping its overlap with chronic neurodegenerative diseases such as AD.

1.3. Alzheimer’s Disease (AD): Overview and Pathology

Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) is the most frequent form of dementia, accounting for 60-80% of all dementia cases worldwide [

28,

29]. Clinically, AD is characterized by the progressive cognitive decline, memory impairment and behavioral disturbances that compromise daily functioning significantly [

30]. From a neuropathological point of view, AD is defined by the accumulation of extracellular amyloid-beta (Aβ) plaques and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) composed of hyperphosphorylated tau protein [

31]. These pathological features contribute to synaptic dysfunction, neuronal death, and cortical atrophy in the hippocampus [

32]. Although Aβ and tau are considered the central pathological features of AD, its pathophysiology is more complex. Evidence implicates additional molecular mechanisms such as brain insulin resistance, chronic oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and persistent neuroinflammation [

33]. Dysregulated insulin signaling impairs neuronal glucose utilization, while oxidative stress and mitochondrial damage compromise cellular energy metabolism, leading to synaptic failure [

34]. Neuroinflammation processes, mediated by activated microglia and astrocytes, contribute to neuronal injury through the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) [

35]. Furthermore, vascular abnormalities have a critical role in driving the neurodegenerative progression. Disruption of cerebral blood flow compromised oxygen and glucose delivery to neurons, while the breakdown of the BBB allows the infiltration of peripheral immune cells and circulating inflammatory mediators into the central nervous system (CNS). These neurovascular processes increase neuroinflammation, impair the clearance of the neurotoxic proteins, and promote neuronal dysfunction, leading gradually to cognitive decline.

1.4. Epidemiological Link Between TBI and Neurodegenerative Diseases

Epidemiological studies have demonstrated a strong connection between TBI and the subsequent development of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease [

36]. A large-scale, propensity-matched cohort study of over 170,000 U.S. military veterans demonstrated that dementia risk increased proportionally with TBI severity, with adjusted hazard ratios of 2.36 for mild TBI without loss of consciousness, 2.51 for mild TBI with loss of consciousness, and 3.77 for moderate to severe TBI [

37].

A meta-analysis further confirmed that TBI almost doubles the risk of all-cause dementia (OR=1.79, 95% Cl: 1.66-1.92), while also increasing the risk of AD (OR=1.60, Cl: 1.44-1.77), vascular dementia (VaD OR= 2.03, 95% CI: 1.79-2.30) and frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD OR=3.99, 95% CI: 2.20-7.20) [

38]. These findings highlight that TBI could be considered a modifiable risk factor for late-life cognitive decline. Human neuropathological studies suggest that TBI can directly initiate or accelerate AD-like processes, including neuroinflammation, excitotoxity, cerebrovascular dysfunction, and BBB breakdown [

39]. As stated in the literature, TBI exacerbates the upregulation of amyloid precursor protein (APP) and tau hyperphosphorylation, which are core characteristics of AD [

40]. These epidemiological and neuropathological findings support the hypothesis that TBI may serve not only as a trigger but also as a potential accelerator of Alzheimer’s disease pathology.

1.5. Aim of the Review

The purpose of the review is to provide a comprehensive mechanistic and clinical perspective of the association between traumatic brain injury (TBI) and subsequent neurodegeneration. Increasing evidence suggests a causal link between TBI and the initiation or acceleration of Alzheimer’s disease. The synthesis of epidemiological, neuropathological and molecular evidence aims to show how acute and repetitive head injuries lead to long-term cognitive decline and development of chronic neurodegenerative diseases. A crucial objective of the review is to highlight the role of biomarkers in facilitating early detection of TBI-related neurodegenerative risk, while also presenting emerging therapeutic solutions that may mitigate or prevent the progression from acute injury to chronic disease.

2. Results

2.1. Physical and Neuropathological Consequences of TBI

Traumatic Brain Injury represents a highly heterogeneous condition characterized by diverse patterns of neuropathological events, with its severity and long-term outcomes determined by the initial biomechanical impact, the magnitude of secondary injury mechanisms, and the brain’s intrinsic capacity for tissue repair. Immediately after trauma, both diffuse and focal structural damage, often accompanied by vascular disruption, predominate. Over time, these acute processes evolve and can give rise to progressive neurodegenerative cascades that unfold over years to decades. As a result, the neuropathological sequelae of TBI are best understood by taking into consideration both the injury severity and the temporal trajectory from the acute to chronic phase.

TBI is increasingly recognized as a trigger for progressive neurodegeneration and increases susceptibility to Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s Disease (PD), Motor Neuron Disease (MND), and Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) [

41,

42]. Diffuse Axonal Injury (DAI) emerges as one of the commonest pathological features of TBI, particularly affecting white matter due to mechanical loading and shear forces generated during impact [

14]. The pathology of DAI begins with primary cytoskeletal disruption, impaired axonal transport, and axonal swelling, which progress to secondary axonal disconnection [

43]. These processes can ultimately lead to Wallerian degeneration and proteinopathies involving amyloid-beta and tau [

44]. In humans, establishing direct causal evidence linking DAI to downstream neurodegeneration remains challenging, as conventional imaging techniques cannot monitor axonal injury at the cellular level [

45]. However, diffusion magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) facilitates in vivo quantification of axonal injury and longitudinal atrophy [

46].

Pathophysiology of DAI

Mechanical indicators such as von Mises stress, which describes brain tissue distortion, are also used to model the likelihood of DAI in TBI [

11]. Primary mechanical injury following trauma involves the rapid deformation of white matter tracts, resulting in cytoskeletal failure and the formation of axonal varicosities and bulbs, “retraction balls,” which show disconnection. Stretching of these axonal fibers to their limit at a rate of 10 s−1 can lead to mechanical damage and finally secondary injury leading to neuronal cell death [

11]. This secondary phase of the injury involves calcium influx and calpain activation, leading to spectrin and microtubule degradation, mitochondrial swelling, and progressive cytoskeletal breakdown over several hours [

47]. Experimental injury models suggest that DAI may serve as a central initiating factor for neurodegeneration after TBI. Disrupted axonal transport also leads to intra-axonal accumulation of amyloid precursor protein (APP), with β-secretase (BACE1) and presenilin-1, promoting intra-axonal amyloid-beta generation [

48,

49]. Tau further dissociates from microtubules and undergoes hyperphosphorylation and propagates into a prion-like manner across the neuronal networks [

50].

From Axonal Injury to Neurodegeneration

DAI is observed across the full spectrum of TBI severity, from mild concussion to severe injuries, and manifests clinically as transient loss of consciousness or confusion to persistent coma and cognitive dysfunction [

14]. Histopathological evidence shows that APP accumulation in damaged axons can be detected within hours upon TBI and can often be more sensitive than silver staining, identifying DAI [

51,

52]. However, axonal degeneration and white matter loss persist for weeks to years following injury in certain patients [

53]. As a result, two non-exclusive mechanistic pathways are proposed to underlie chronic degeneration following TBI: i) Wallerian degeneration of axons characterized by transport failure, ii) Proteinopathies, particularly amyloid-beta and tau, originating from traumatic axonal pathology and propagating across interconnected brain networks.

Neuroimaging Evidence Linking DAI to Neurodegeneration

Graham et al. 2023 investigated whether the severity and spatial distribution of diffuse axonal injury (DAI) predict progressive neurodegeneration in a cohort of 55 patients with moderate to severe TBI [

54]. The study demonstrated by using diffusion MRI, that the DAI burden is the leading factor of chronic white degeneration, promoting a causal relationship between axonal injury and subsequent tissue loss. Fractional anisotropy (FA), a diffusion-derived metric used to calculate the white matter structure, has emerged as an important marker of axonal integrity in the chronic phase of TBI [

55]. Reduced FA reflects axonal disruption and associated neuroinflammation and has been correlated with large-scale network dysfunction and cognitive impairment [

56]. Serial T1-weighted volumetric imaging further enables accurate quantification [

57]. Diffusion abnormalities have also been linked to grey matter volume changes through network diffusion modeling, indicating the relationship between white matter disconnection and cortical degeneration [

58]. Conventional imaging markers of DAI, including T2, Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) and T2*-weighted sequences, have been associated with region specific atrophy pathways early after injury [

45].

Overall, DAI has emerged as a strong predictor of progressive neurodegeneration after moderate-to-severe TBI, explaining in this way most of the variability in white matter atrophy and long-term neurodegeneration. Evidence from both pathology and neuroimaging supports the central role of axonal injury in progressive tissue loss, functional impairment, and finally increased dementia risk.

2.1.1. Types and Severity of TBI

The clinical spectrum of TBI is classified as mild, moderate, or severe and is based on the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), the duration of loss of consciousness (LOC), and the extent of post-traumatic amnesia [

59]. Mild TBI is often described as a concussion and typically presents with transient LOC, confusion, and subtle cognitive changes. While symptoms usually resolve, a subset of patients develop persistent post-concussive complaints [

60]. Moderate to severe injuries are characterized by extended loss of consciousness, radiologically visible lesions such as contusions or hematomas, and a greater risk of long-term disability [

61,

62]. At the pathological level, severe TBI is associated with diffuse axonal injury (DAI), hemorrhage, and necrotic cavitation [

12]. Even in mild cases, microscopic axonal disruption and glial reactivity may occur, changes that are not readily detectable on conventional imaging but have functional consequences [

63].

2.1.2. Acute Phase of TBI

The acute phase of TBI progresses within minutes to days after the initial insult and involves a cascade of cellular, vascular, and metabolic disturbances [

64]. Mechanical deformation and shearing forces disrupt neuronal and glial membranes, causing further ionic disequilibrium, glutamate release, and excitotoxic activation of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) and α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptors [

65]. This cascade leads to calcium overload, mitochondrial dysfunction, and excessive production of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, driving oxidative stress and energy depletion. Cytotoxic edema develops as astrocytic and neuronal swelling accumulate, exacerbating intracranial pressure and perfusion deficits [

66]. At the same time, the blood-brain barrier becomes compromised and permeable since tight-junction proteins get degraded, endothelial adhesion molecules are upregulated, and peripheral immune cells infiltrate the parenchyma, amplifying neuroinflammatory responses [

67,

68]. Microvascular dysfunction, microthrombosis, and early hypoperfusion enhance the secondary injury cascade, indicating chronic pathology.

2.1.3. Chronic Phase of TBI

Beyond the acute phase of TBI, many survivors undergo a chronic phase characterized by long-lasting neuropathological changes that all contribute to progressive cognitive, behavioral, and motor deficits. Diffuse axonal injury evolves into chronic axonopathy associated with disconnection of white matter tracts, demyelination, and gliosis. Persistent microglial activation and astrocytosis maintain a pro-inflammatory environment for years following even a single moderate to severe TBI, as shown by both human postmortem studies and in vivo imaging [

69]. These inflammatory processes converge with vascular injury, blood-brain barrier disruption, and problematic clearance pathways to drive abnormal protein accumulation, particularly hyperphosphorylated tau and amyloid-beta deposits [

19]. This results in a neuropathological process that links TBI with later neurodegenerative diseases, including chronic traumatic encephalopathy and Alzheimer’s disease. Clinically, the chronic phase presents with enduring cognitive dysfunction, psychiatric disturbances, namely depression and anxiety, and increased risk of dementia.

2.1.4. Diffuse Axonal Injury (DAI)

Diffuse axonal injury (DAI) is recognized as one of the most characteristic substrates of TBI, particularly in acceleration-deceleration and rotational injuries, and primarily affects the axons of cerebral white matter, which are vulnerable to mechanical strain during trauma [

43]. Under a pathological spectrum, DAI represents rather than a single lesion, it encompasses a spectrum of axonal damage ranging from cytoskeletal disruption and impaired axonal transport to swelling and axonal disconnection, further leading to Wallerian degeneration. The hallmark histological findings include axonal swellings and bulbs, with accumulation of amyloid precursor protein (APP) occurring within hours of injury. Although the definitive diagnosis still requires post-mortem histopathology, innovative neuroimaging methods such as diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) have been presented as sensitive tools used in vivo to detect white matter abnormalities, with fractional anisotropy (FA) reduction being a sensitive marker of axonal injury [

70].

Experimental evidence suggests the concept that DAI is a trigger of progressive neurodegeneration and not only an acute injury phenomenon. Cytoskeletal disruption initiates axonal swelling and bulb formation in sites where APP accumulates with β-secretase (BACE1) and presenilin-1, leading to amyloid-β production [

71]. Dissociation from microtubules and abnormal phosphorylation following injury was also seen in young athletes and experimental mice models, showing that traumatic axonal injury can induce early tauopathy [

72]. Recent studies showed prion-like propagation of tau pathology in animal models of TBI, suggesting a potential mechanistic link between DAI and progressive neurodegeneration. A single moderate-to-severe TBI could accelerate dementia onset and increase the risk of AD through the same axonal pathways of protein accumulation and degeneration. Imaging studies show that DAI predicts progressive brain atrophy after TBI. By using diffusion MRI and volumetric T1 imaging, Graham and colleagues demonstrated that fractional anisotropy calculated in the chronic phase following TBI was a strong predictor of subsequent atrophy in white matter tracts such as the corpus callosum [

44]. In addition, calcium influx and calpain activation following the axonal stretch injury trigger proteolysis of the structural proteins, disruption of microtubules, and mitochondrial dysfunction, which all lead to axonal failure [

73]. These inflammatory processes may persist for years following trauma in the corpus callosum [

53]. DAI presents as a critical mechanical and imaging marker of progressive post-traumatic neurodegeneration, since it establishes a link between axonal disruption and chronic degeneration.

2.1.5. Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (Neuropathological Features, Clinical Manifestation, Risk Factors, Diagnosis)

Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) is a progressive neurodegenerative tauopathy associated with repetitive head impacts (RHI) [

74]. Originally, it was described in boxers as ‘punch drunk’ syndrome; this condition is now well recognized across a range of contact sports and military personnel [

75]. In a neuropathological basis, it is unique since it consists of perivascular deposits of hyperphosphorylated tau found at the depths of cortical sulci [

76]. Clinically, CTE manifests with cognitive, mood, and behavioral alterations that can manifest years after exposure. The first descriptions of long-term neurological impairment following repeated head trauma were reported by Martland in 1928, who described boxers’ symptomatology with gait disturbance, slowed speech, and cognitive decline [

77]. Millspaugh later described the punk drunk syndrome as dementia pugilistica [

78]. In 1973, Corsellis and colleagues published a neuropathological study of 15 retired boxers to whom they identified cortical atrophy, neurofibrillary tangles, and cerebellar scarring, further enhancing the theory of dementia pugilistica [

79]. These early observations set the basis for later recognition of a neurodegenerative disease. In the 2000s, the work of McKee and Colleagues established modern diagnostic criteria and a four-stage neuropathological staging scheme [

80,

81]. Early disease presents with focal perivascular lesions, while advanced stages show widespread cortical, limbic, and brainstem involvement [

82].

The central lesion in CTE is perivascular deposition of hyperphosphorylated tau (p-tau) in neurons and astrocytes, located deep in the cortical sulci [

83]. This is the most important difference compared to AD, because although both are tauopathies, CTE lesions are perivascular, sulcal, and not associated with neuritic amyloid plaques. Molecular studies, also, using cryo-electron microscopy showed that tau filaments in CTE adopt a distinct conformation compared to those in AD, proposing CTE as a unique tauopathy [

84]. Although tau remains the defining pathology, other findings include transactive response DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43) inclusions, axonal degeneration, and white matter degradation [

85]. These changes overlap with other neurodegenerative diseases, further highlighting the need for specificity in biomarker CTE-tailored development. Systematic comparisons between CTE and normal aging, as well as other tauopathies, validate the specificity of perivascular sulcal tau lesions [

86]. Specifically, the presence of TDP-43 and amyloid-related pathology in both CTE and non-CTE brains further highlights the importance of distinct pathological interpretation. A recent study, which examined 185 athletes, demonstrated cortical thinning, neuronal loss, and synaptic alterations, particularly in sulcal regions, further enhancing the hypothesis that regional biomechanical vulnerability determines lesion localization [

87]. Increased astrocytic activity and aquaporin-4 upregulation around the lesions showed BBB dysfunction; however, microgliosis was less prominent [

88].

Clinical Manifestations

The clinical presentation of CTE is varied. Symptoms present years after injury and cluster into four main domains: i) cognitive with executive dysfunction and memory loss, ii) behavioral with impulsivity, iii) mood with psychiatric disorders such as depression and suicidality, iv) motor with Parkinsonian characteristics and dysarthria [

89,

90,

91]. Clinical studies of former football players showed a high prevalence of behavioral and mood changes before the initiation of cognitive decline [

92,

93]. To explain the gap between neuropathology and clinical presentation, Montenigro et al. proposed the concept of traumatic encephalopathy syndrome (TES) [

94].

Risk Factors

The principal risk factor for CTE is exposure to repetitive head trauma. Mez et al. reported CTE pathology in 87% of 202 decreased American football players, with disease severity being directly correlated to the duration of their athletic career [

95]. Alosco et al. 2018) further demonstrated a dose-response relationship between years of football and risk of CTE, which was thought to be independent from concussion history [

96]. Other modifiers include genetic risk factors such as APOE and TMEM106B, although these associations are still under investigation [

97,

98].

Diagnosis

At present, CTE can only be diagnosed definitively at autopsy. The DIAGNOSE CTE Research project, a prospective study of 240 men with different exposures to American football, aims to develop clinical criteria and biomarkers [

99]. Fluid biomarkers, namely plasma tau, neurofilament light chain, as well as markers of microglial activation (soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 [sTREM 2]), are also being evaluated. [

100]

2.2. Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms Linking TBI to AD

2.2.1. Blood -Brain Barrier Dysfunction

The blood-brain barrier (BBB) is a specialized neurovascular unit formed by endothelial cells, pericytes, and astroglial cells, which together maintain central nervous system homeostasis [

101]. Following TBI, the BBB undergoes rapid and sustained disruption, which exacerbates secondary injury cascades. Mechanical shear stress and vascular rupture comprise barrier integrity, allowing plasma proteins and immune cells to enter the parenchyma [

39]. Endothelial cell activation leads to the upregulation of adhesion molecules such as Intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM), Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule-1 (VCAM-1), and selectins, facilitating leukocyte adhesion and transmigration, which further amplifies the neuroinflammation and oxidative stress cascade [

102]. Elevated P-selectin levels promote multicellular aggregation and microvascular occlusion, aggravating ischemic vulnerability. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) rises sharply after TBI, inducing angiogenesis but simultaneously downregulating tight junction proteins such as occludin and claudin-5, weakening endothelial cohesions and increasing vascular leakage [

103,

104]. These alterations result in vasogenic edema, neuroinflammation, and impaired tissue repair capacity. BBB disruption is not transient, since chronic dysfunction is characterized by pericyte loss, endothelial degeneration, and tight junction protein disorganization [

105]. Chronic mural cell degeneration and reduced expression of Caveolin-1 (Cav-1) and Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1) impair the Aβ and tau clearance, which establishes neurodegeneration [

106].

Findings from both human and animal studies suggest that the BBB disruption is a central link between TBI and Alzheimer’s disease. Evidence indicates BBB breakdown in AD precedes cognitive decline, manifesting as vascular leakage, reduced glucose transport, and leukocyte infiltration [

107]. In TBI, the ‘two-hit’ hypothesis model proposes that the initial mechanical disruption is compounded by secondary inflammatory and metabolic cascades, resulting in alterations in vascular and cellular permeability [

108,

109]. Pharmacological interventions targeting BBB repair, even one-year post-injury, reversed axonal degeneration and restored cognition, which highlights barrier restoration as a promising therapeutic strategy [

110].

At the molecular level, BBB vulnerability is shaped by genetic and signaling factors. In APOε4 carriers, increased BBB permeability has been linked to activation of the cyclophilin A/matrix metalloproteinase 9 (CypA/MMP-9) pathway and degradation of LRP1. Concurrently, reduced expression of the major facilitator superfamily domain-containing protein 2A (Mfsd2a) promotes caveolae-mediated transcytosis, further compromising barrier integrity [

111]. Impairment of Wingless/Integrated (Wnt)/β-catenin signaling further impairs tight junction integrity and endothelial-pericyte communication, linking this way genetic and molecular predisposition to blood-brain barrier fragility [

112].

2.2.2. Chronic Vascular Changes

Beyond the parenchymal injury, TBI triggers early alterations in leptomeningeal arterial vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) that disrupt cerebrovascular homeostasis and promote amyloidogenic processes. Experimental and post-mortem studies have demonstrated pathological changes in cerebral vessels, including altered distribution of NOTCH3 and alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) within the tunica media, indicating vascular smooth muscle cell dysfunction. These structural abnormalities are accompanied by the early aggregation of Aβ peptides (Aβ1-40/42, Aβ1-16, beta C-terminal fragment of APP (β-CTF)/C99) around VSMCs, even in young individuals following TBI, whereas controls show strong uniform marker expression and minimal vascular amyloid deposition [

113]. These vascular changes are thought to arise from local hypoxia and oxidative stress, which lead to beta-secretase-mediated (BACE-1) APP cleavage with relative downregulation of the non-amyloidogenic a disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain-containing protein 10 (ADAM10) pathway. Therefore, VSMC dysfunction impairs cerebrovascular reactivity, compromises cerebral perfusion, and might lead to secondary ischemia and long-term neurodegeneration [

114].

2.2.3. Excitotoxicity

Mechanical forces generated upon head impact strain the neuronal and glial membranes, leading to widespread depolarization of axonal networks and excessive glutamate release. Elevated extracellular glutamate will then activate synaptic and extra-synaptic NMDA receptors [

115,

116]. Astrocytic transporter inability to sustain the extracellular glutamate drives Ca²⁺ influx and downstream apoptotic and necrotic signaling [

117]. The rapid entry of cations depolarizes neurons, which leads to the indiscriminate release of neurotransmitters such as the glutamate and disrupts synaptic integrity and network stability, further contributing to both acute neuronal injury and long-term neurodegenerative vulnerability.

2.2.4. Oxidative Stress

TBI promotes the generation of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and Reactive Nitrogen Species (RNS) through mitochondrial dysfunction, altered cellular metabolism, and activation of inflammatory oxidases [

118]. The resulting oxidative and nitrosative stress induces lipid peroxidation, protein nitration, and DNA damage. These alterations contribute to neuronal loss, glial reactivity, and neuroinflammation, accelerating neurodegenerative processes [

119].

2.2.5. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Ferroptosis

Mitochondria regulate cellular energy metabolism, redox homeostasis, and Ca2+ regulation, all of which are disrupted following TBI [

120]. Impaired electron transport and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) lead to adenosine triphosphate (ATP) depletion, ROS overproduction, and maladaptive mitochondrial dynamics that compromise repair and synaptic plasticity, which are phenomena also observed in early Alzheimer’s disease. A recent study implicated the role of ferroptosis, which is an iron-dependent lipid peroxidation pathway, in TBI-associated neuronal death [

121]. In experimental models, pharmacological or genetic inhibition of mitoNEET (CDGSH iron–sulfur domain-containing protein 1 [CISD1]) reduces ferroptosis and preserves cognition by stabilizing dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH)- mediated mitochondrial defenses, indicating that the mitoNEET/DHODH axis could act as a potential therapeutic target [

122]. Region-specific proteomic signatures further reveal that repetitive as opposed to single, mild TBI produces persistent dysregulation of mitochondrial and synaptic proteins, especially within the hippocampus, correlating with cognitive decline [

123].

2.2.6. Coagulopathy and Microvascular Hemorrhage

TBI initiates an early hypercoagulable state through BBB disruption, activation of the extrinsic pathway, endothelial glycocalyx degradation and platelet leukocyte endothelium interaction, followed by coagulopathy and hyperfibrinolysis [

124,

125,

126,

127].

2.2.7. Cerebral Blood Flow Changes

Alterations in cerebral blood flow are common following TBI and strongly influence prognosis. Hypoperfusion correlates with cognitive impairment and poor outcomes, whereas timely restoration of Cerebral Blood Flow (CBF) is associated with functional improvement [

128,

129]. Loss of vascular muscle cell contractility and impaired pericyte mediated regulation disrupt the neurovascular coupling, since they limit delivery of oxygen, and glucose delivery in periods of increased metabolic demand [

130,

131,

132].

2.2.8. Genetic Susceptibility Linking TBI and Alzheimer’s Disease

Inherited genetic factors and dysregulation in molecular pathways are recognized as important contributors in determining how traumatic brain injury (TBI) and diffuse axonal injury (DAI) progress toward Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) [

133]. Recent studies have expanded the understanding of how somatic mutations, trauma-related alterations in lipid metabolism, protein clearance pathways, and blood-brain barrier (BBB) regulators may accelerate neurodegeneration after head injury [

134]. Somatic mosaicism has recently been identified as a potential mechanism linking acute trauma to chronic neurodegeneration. Single cell sequencing of TBI and AD brain tissue revealed overlap in somatic mutations across molecular pathways, which suggests that trauma may accelerate genomic instability in neurons and glia. This analysis highlighted that trauma is not only a mechanical insult but also a mutagenic trigger that may exacerbate age-related genetic vulnerabilities [

135].

Among germline susceptibility factors, the APOE locus remains the most extensively studied. The ε4 allele was associated with worse outcomes following TBI and an increased risk of AD [

136]. Previous studies have shown a tenfold increased risk of AD diagnosis among ε4 carriers with a TBI history [

137]. A meta-analysis of 2,600 patients suggested that ε4 carriers have poorer global outcomes following TBI [

138]. The structural and vascular consequences of APOE isoforms show that ε4 exacerbates cerebral amyloid angiopathy, BBB leakage, and perivascular tau deposition. The human apolipoprotein E gene APOE gene encodes three isoforms: APOEε2, APOEε3, and APOEε4, and is predominantly expressed by astrocytes in the brain. APOEε4 has been linked with being the strongest genetic risk factor for early and later onset AD, as well as being associated with poor outcomes following TBI, since it disrupts the BBB [

139]. APOE ε4 interacts with lipid metabolism and neuroinflammatory cascades and accelerates, in this way, both the traumatic and degenerative pathology, whereas ε2 appears protective in certain cases but is a risk factor in severe vascular injury. The age of onset of AD is three years lower among ε4 carriers with TBI compared to non-carriers with TBI [

140]. APOE’s role in oxidative stress and excitotoxic process after trauma enhances the hypothesis that isoform-specific effects extend to acute injury physiology as well as long-term degeneration.

New molecular mechanisms within the APOE locus have also been identified. translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane 40 (TOMM40)-APOE (T9A2), a chimeric fusion transcript, was reported to modify the mitochondrial trafficking and accelerate the amyloidogenic processing in AD models [

141]. Given the importance of mitochondrial dysfunction in TBI pathology, the TOMM40-APOE fusion may represent an important molecular link between acute axonal injury with late amyloid-driven degeneration.

Autophagy and protein clearance pathways also have a central role in linking TBI to subsequent neurodegenerative pathology. BCL2-associated athanogene 3 (BAG3), a co-chaperone that regulates autophagy-lysosome flux, plays a key role in tau clearance. Reduced BAG3 function disrupts tau regulation and accelerates neurofibrillary pathology, which enhances the hypothesis that repetitive TBI, through impaired proteostatic recovery, may increase vulnerability to CTE and AD tauopathy [

142]. Another study showed that genetic variants affecting neprilysin activity have been shown to reduce enzymatic clearance of Aβ, thereby potentiating plaque accumulation. These findings suggest that genetic regulation of proteostasis is important in determining whether traumatic brain injury progresses towards Alzheimer’s pathology [

143,

144]. Additional susceptibility loci have also been identified through genome-wide association studies (GWAS), including variants in Triggering Receptor Expressed on Myeloid Cells 2 (TREM2). Particularly, the R47H variant of TREM2 has been associated with a fivefold increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease (OR=5.05, 95% CI: 2.77–9.16, p < 0.001) [

145].

Signaling pathways that regulate the BBB integrity and neurovascular stability present as essential regulators of TBI to AD progression. Transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) signaling, which normally has a neuroprotective role since it promotes the expression of tight junction proteins and mediates the recruitment of astrocytes to the BBB, can become maladaptive under conditions of chronic trauma, while promoting glial scar formation and impaired repair [

146]. Mfsd2a, a lipid transporter crucial for BBB integrity, is downregulated following a TBI, potentially facilitating the amyloid influx and vascular inflammation [

147]. Particularly, this transporter is downregulated with age, with a stronger reduction in 5xFAD Alzheimer’s disease (AD) model mice compared to wild-type mice. This downregulation is amplified further in the presence of APOE4, a major AD risk allele, and a similar reduction is also observed in human APOE4, suggesting that enhancing Mfsd2a expression could potentially restore BBB integrity [

148]. The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, which regulates endothelial tight junctions and cellular proliferation, is disrupted in both AD and TBI, contributing to vascular dysfunction. As a result, the upregulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling is important to vascular repair, as it was shown with the intranasal application of recombinant Wnt3a, which promoted BBB repair after TBI [

149]. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) is upregulated following trauma and contributes to BBB disruption and neuronal apoptosis. In TBI, MMP-9 expression is significantly elevated in neutrophils after the initial insult [

150]. Sonic Hedgehog (Shh) signaling is pivotal in neural development and normal brain function. However, in TBI it has been implicated that the expression of endogenous Shh is downregulated after TBI, leading to impaired signaling in the acute phase and suppressed neural stem cell renewal in chronic TBI [

151]. Finally, Mechanistic (mammalian) target of rapamycin (mTOR) dysregulation has been observed in both TBI, with hyperactivated linked to impaired autophagy and accumulation of toxic protein aggregates. Evidence indicates that mTOR activation occurs early in Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis, with upregulated mTOR signaling promoting Aβ and tau aggregation, neuroinflammation, and oxidative stress [

106].

2.3. Clinical Presentation of TBI-Related Neurodegeneration

The clinical spectrum of traumatic brain injury-related neurodegeneration (TBI-ND) includes a plethora of cognitive, behavioral, and psychiatric manifestations that can impair the quality of life of the individual. Memory impairment is frequently reported in the literature, with patients having problems in learning new information, retaining, and retrieving [

152,

153]. Both anterograde and retrograde amnesia were observed, showing disruption of the hippocampal cortical network [

154]. Executive dysfunction was also recorded with impairments in decision-making processes and organization [

155]. Beyond cognitive decline, mood disturbances and behavioral dysregulation were common clinical features [

156]. Irritability, agitation, depression, and anxiety emerge, which disrupt the interpersonal relationships of the individual [

157].

2.4. Risk Factors

TBI does not operate as an isolated insult but instead as a contributor that interacts with multiple biological and demographic risk factors to accelerate the progress towards Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative diseases [

158]. These include age, sex, vascular and systematic comorbidities, sleep disturbances and neuroinflammation.

2.4.1. Age

Age is a crucial determinant of dementia risk in the general population and modifies the effects of TBI on long-term outcomes. Epidemiological data suggest that younger individuals experience a disproportionately higher relative risk. A meta-analysis of 32 observational studies found that TBI was associated with a pooled risk ratio (RR) of 1.51 (95% CI: 1.26–1.80) for developing Alzheimer’s disease [

159]. Gardner et al. (2014) similarly reported that moderate-to-severe TBI reported nearly double the risk of dementia in older adults, while mild TBI showed weaker associations [

160]. Interestingly, age was also found to suppress the association between traumatic brain injury severity and functional outcomes. Adding age at injury to regression models significantly increased the association between TBI severity and functioning at all follow-up points (up to 10 years) [

161]. These findings support the hypothesis that TBI accelerates brain aging by lowering the threshold for clinical dementia onset. Recent neuroimaging evidence supports this biological aging model, since mild TBI patients demonstrate significantly increased brain-predicted age gaps (brain-PAG) correlating with cognitive impairment and neurofilament light chain levels [

162].

2.4.2. Sex and Gender

Sex differences in TBI incidence are increasingly investigated in the literature, reflecting interest in potential demographic influences on injury patterns. Men sustain more TBIs overall, with peaks in young adulthood and late life, but women experience worse functional and cognitive consequences [

163]. A meta-analysis of 19 studies showed that female patients had poorer outcomes in 85% of examined domains, with a small-to moderate effect size (d=-0.15) [

164].

Another study found that female athletes with sports-related concussion reported more severe post-concussive symptoms and slower recovery trajectories than males [

165]. Although some studies indicate better psychosocial adjustment in women, most of the evidence points towards sex-specific vulnerabilities, reflecting hormonal influences and immune regulation.

2.4.3. Vascular and Systemic Comorbidities

TBI shares common vascular and systemic risk factors with AD, including hypertension, diabetes and hyperlipidemia [

166]. Hypertension exacerbates blood-brain barrier (BBB) breakdown, a hallmark of both TBI and AD, and is associated with worse cognitive outcomes after head trauma [

167]. Diabetes mellitus promotes amyloidosis and oxidative stress, while it exacerbates the TBI-induced cortical damage and is associated with increased mortality and poorer recovery [

168]. Hyperlipidemia and atherosclerosis promote amyloid deposition and tau hyperphosphorylation while high-fat diets in experimental TBI models delay BBB repair and worsen cognitive outcome [

169].

2.4.4. Lifestyle Exposures

Modifiable lifestyle factors that increase the risk of dementia and worsen post-TBI recovery. Smoking is associated with vascular dysfunction, oxidative stress, and increased tau phosphorylation in AD models, while it is linked with poorer neurocognitive outcomes after TBI [

170,

171]. Alcohol use increases BBB permeability exacerbates the amyloid β-aggregation and contributes to higher mortality after TBI.

2.4.5. Sleep and Neuroinflammation

Sleep disturbance and neuroinflammation are important mechanisms through which TBI predisposes towards AD. Sleep issues are observed in most of the AD patients and frequently precede cognitive decline [

172]. In TBI, sleep disturbances are highly prevalent and are linked with increased neuroinflammation [

173]. Green et al.’s study highlighted, among others, how cytokines such as interleukins IL-1β and IL-6, and TNF-α, which normally act as sleep regulators, become upregulated after trauma, increase microglial activation, and ultimately exacerbate secondary brain injury [

174].

2.4.6. Neurovascular Dysfunction

The neurovascular unit (NVU) provides a convergent mechanism linking these diverse risk factors. Genetic susceptibility, vascular changes, systemic exposures, and TBI resulting in mechanical damage are linked with BBB integrity disruption and cerebral flow regulation. This dysfunction allows the entry of plasma proteins, namely fibrinogen, into the CNS, triggers chronic neuroinflammation, and leads to amyloid and tau accumulation [

175]. Hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons exhibit selective neuronal vulnerability in the setting of NVU dysfunction. TBI-related disruption of NVU integrity explains why survivors show increased susceptibility to hippocampal-dependent memory decline characteristic of AD.

2.5. Biomarker Evidence

2.5.1. Fluid Biomarkers

Fluid-based biomarkers in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and blood have been proven to be of critical importance in the pathophysiology of traumatic brain injury. Among the most investigated are amyloid-β (Aβ), total tau (t-tau), phosphorylated tau (p-tau), neurofilament light chain (NfL), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolase L1 (UCH-L1), and S100B.

These markers reflect axonal degeneration, astroglial damage, amyloid metabolism, and cytoskeletal disruption [

176,

177]. Acute TBI triggers a cascade of biomarker alterations with distinct temporal patterns. GFAP becomes detectable within the first hour after injury and peaks between 20-24 hours, and declines over the following 72 hours [

178]. S100B concentrations are detectable in the peripheral circulation as early as 15 minutes and return to baseline within 1-2 hours [

179]. UCH-L1 is detectable in peripheral blood shortly post-injury and increases, reaching a peak 8-12 hours after initial trauma [

180]. Findings from the large CENTER-TBI cohort of 2,869 patients showed that serum levels of GFAP, NfL, NSE, S100B, t-tau, and UCH-L1 are strongly correlated with injury severity and lesion extension with diffuse axonal injury (Marshall III/IV), producing higher concentrations than focal mass lesions [

181]. In another study, it was shown that serum NfL outperformed other biomarkers, namely tau, S100B, and neuron specific enolase (NSE), in characterizing sports-related concussion (SRC) [

182]. Proteomics analyses emphasize the biological aspect of TBI. A study identified 16 plasma proteins altered within 10 days following moderate-to severe TBI, including neuronal (UCH-L1, visinin protein 1), astroglia (GFAP, S100B), neurodegenerative (tau, pTau231, presenilin-1 (PSEN1), Aβ42), and inflammatory (IL-16, C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 [CCL2]) markers. These molecular alterations correlated with lesion volumes and white matter integrity, underscoring the interplay between biochemical signals and pathology [

183]. Recent evidence also demonstrated long-term biomarker changes in athletes exposed to repetitive head impacts. Elevated plasma p-tau217 and NfL were noted in former rugby players compared to controls, with p-tau217 levels associated with traumatic encephalopathy syndrome and smaller hippocampal volume, while NfL was linked to anxiety symptoms [

184].

2.5.2. Imaging Biomarkers

Neuroimaging is essential to understand the neuropathological consequences of TBI and RHI, particularly in relation to neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s Disease and Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE). Advances in MRI, positron emission tomography (PET), and fluid biomarker imaging have drastically evolved the ability to detect both acute injuries as well as long-term neurological changes.

PET imaging facilitates the in vivo detection of hallmark AD pathologies, especially beta-amyloid (Aβ) and tau aggregates. In AD, PET findings showed that plaques emerge in a predictable spatial and temporal sequence [

185]. Amyloid PET has been proposed as the earliest biomarker of AD, appearing years before clinical manifestation [

186,

187]. However, Eagle et al. reported that middle-aged individuals with a history of repeated TBIs showed no significant elevations in amyloid or tau PET uptake compared with controls, despite a higher symptom burden [

188]. These results highlight that in trauma-related neurodegeneration, conventional AD biomarkers may not reliably differentiate risk groups; thus, alternative TBI-targeted biomarkers may be needed. MRI techniques provide sensitive markers of traumatic and degenerative processes. Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI) is particularly designed to provide information on axonal injury.

Preclinical models demonstrated DTI’s sensitivity in detecting traumatic white matter damage [

189]. Zimmerman et al. [

190] identified axonal and vascular injury signs in elite rugby players, with abnormal trajectories of white matter change. Volumetric MRI changes reveal a reduction in whole brain and hippocampal volume in professional rugby players [

191]. Larger studies, such as the BRAIN Health Cohort, are now examining whether volumetric brain loss, white matter changes, and fluid biomarkers (NfL, GFAP, phosphorylated tau) correlate with exposure extent and clinical outcome [

192].

Raji et al. reported that MRI volumetry strongly distinguishes TBI from early and late onset Alzheimer’s and behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) by distinct atrophy patterns. Atrophy is identified in the hippocampus in AD, frontal in the bvFTD, and white matter loss in TBI [

193].

Shetty et al. 2015 [

194] reviewed the established role of CT and MRI in detecting acute trauma, including cortical contusions, DAI, and secondary complications such as hydrocephalus. While CT remains the first-line modality for acute injuries, MRI provides increased sensitivity for smaller contusions and chronic conditions such as encephalomalacia. Recent advances highlight the important role of imaging in correlation with blood-based biomarkers. Lagramante et al. [

195] demonstrated that GFAP and UCH-L1 assays could exclude with accuracy CT-detectable lesions in suspected mild TBI. Similarly, this is also shown in multimodal studies of retired athletes assessing the relationship between volumetric MRI with white matter integrity and plasma biomarkers.

2.5.3. Comparison to Alzheimer’s Disease Biomarker Profiles

An important question in TBI research is whether the biomarker alterations observed following injury resemble those characteristics of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Both conditions share certain common markers, namely amyloid-β, total tau (t-tau), phosphorylated tau (p-tau), neurofilament light chain (NfL), and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), but they differ in timing of appearance, magnitude, and long-term pathways [

196,

197]. In AD, the combined presence of decreased CSF Aβ42, elevated p-tau181 or p-tau217, and increased total tau constitutes a validated biomarker indicator, with detection established in CSF and now increasingly detectable in blood through highly sensitive single-molecular array (Simoa) assays [

198,

199]. In TBI, acute elevations in GFAP, NfL, and tau reflect immediate structural and axonal injury, while p-tau 217 elevations suggest a convergence with AD pathology [

200,

201]. However, biomarker pathways appear to differ in magnitude and temporal relationships.

Amyloid pathology emerges early in TBI, where increased APP cleavage and impaired clearance due to lymphatic and blood-brain barrier dysfunction contribute to acute Aβ accumulation [

202]. While AD is defined by a consistent reduction in CSF Aβ42 and plasma Aβ42/40 ratio, TBI produces more heterogeneous Aβ dynamics, with acute elevations that may transition into chronic deposition [

203]. Recent work by Friberg et al. 2024 demonstrated overlapping CSF profiles between chronic TBI (cTBI) patients and those with AD, indicating a partial shared pathway with amyloid-driven pathology [

204].

Tau-related changes also present an evident overlap between the two conditions. In AD, elevated CSF and plasma p-tau, especially subcategories such as p-tau217 and p-tau231, are highly specific for AD pathology and closely linked to neurofibrillary tangle accumulation [

205]. TBI is characterized by acute elevations in total tau (t-tau) reflecting axonal damage, while chronic increases in phosphorylated tau (p-tau217) have been reported in athletes with traumatic encephalopathy syndrome (TES) [

206].

Axonal injury markers, particularly NfL, present strong prognostic utility in TBI. Andersson et al. (2024) demonstrated that cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) NfL levels continue to rise for up to 2 weeks following severe TBI and independently predict unfavorable outcomes at both one year and 10-15 years post-injury [

207]. Elevated plasma NfL has also been associated with depressive and anxiety symptoms, as well as frontal cortical atrophy, in retired rugby players [

205]. Astroglial injury markers, most notably glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), show marked divergence between TBI and AD. In severe TBI, CSF GFAP peaks on days 3-4 and remains elevated for months or years, with higher levels predicting poor long-term outcomes [

207]. Synaptic injury markers, including synaptosomal-associated protein 25 (SNAP-25) and visinin-like protein 1 (VILIP-1), are emerging as potential informative biomarkers. Evidence from sTBI indicates a biphasic trajectory, with an early rise reflecting primary synaptic damage and a delayed peak linked to neuroinflammatory responses. Importantly, SNAP-25 and VILIP-1 demonstrated superior predictive performance for six-month outcomes compared to NfL or GFAP [

208]. These biomarkers were also elevated in AD and other neurological conditions, highlighting their role as indicators of synaptic dysfunction [

209].

Neuroinflammatory markers differentiate TBI from AD. Acute TBI triggers robust increases in cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF, IL-17A) and persistent immune activation, with autoantibodies against GFAP, S100B, and Myelin-associated glycoprotein (MAG) detected more than a decade post-injury [

210,

211]. In AD, inflammation is a prominent feature but tends to follow a slower and more chronic pathway without the acute peaks that are characteristic of TBI.

2.5.4. Neuroinflammation as a Mediator of Tau Pathology

The relationship between traumatic brain injury (TBI) and tau pathology is now increasingly recognized as a key pathway connecting acute trauma to chronic neurodegeneration. Neuroinflammation driven by microglial activation, cytokine release, and inflammasome signaling is an important mediator of tau phosphorylation and subsequent expansion. This mechanistic link provides biological plausibility to the epidemiological association between TBI and tauopathies such as chronic traumatic encephalopathy and Alzheimer’s disease. Human post-mortem studies demonstrate that even a single moderate-to-severe TBI can lead to widespread phosphorylated tau (p-tau) accumulation, involving cortical layers, the hippocampus, thalamus, and the substantia nigra [

212]. The density and the distribution of tau depositions differ between age-matched controls and CTE, with CTE characterized by perivascular tau deposits localized at the depths of cortical sulci [

74]. Experimental studies have further shown that brain homogenates derived from TBI mice, when inoculated into naïve animals, induce widespread tau pathology, synaptic loss, and persistent memory deficits, supporting a prion-like transmissible mechanism of tau propagation [

213]. Evidence also suggests that temporality is an important factor too, since P-tau deposition emerges years to decades after injury; however, in TBI survivors, it often appears at a younger age than in controls, suggesting that trauma accelerates the disease onset [

214]. In wild-type mice, severe TBI initiates progressive tau accumulation, initially localized to the injured hemisphere and later spreading to the contralateral regions over 12 months [

213,

215]. Tau protein aggregates in these models resemble neurofibrillary tangles, glial inclusions, frequently with perivascular localization [

216]. These results establish the view that trauma-induced tau pathology is self-propagating, with neuroinflammation creating an environment for amplification and spread.

At the mechanistic level, microglial activation has a crucial impact. Activated microglia release pro-inflammatory cytokines, namely interleukin IL-1β, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, which exacerbate tau hyperphosphorylation through kinase-dependent cascades [

217]. In vivo PET studies show sustained glial reactivity in athletes with repetitive concussion [

10]. These inflammatory responses correlate with subsequent neurodegeneration. Another study reported a threefold increase in IL-1α–positive microglia after head injury, which correlated with β-amyloid precursor protein–positive neurites (R=0.78, p<0.05), indicating that inflammation directly promotes neurotoxic protein accumulation [

218].

The inflammasome pathway further links inflammation with tau pathology. NOD-, LRR-, and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome was shown to regulate pathological tau accumulation, with its prolonged activation driving IL-1β release and caspase-mediated pyroptosis [

219]. Experimental interventions targeting this pathway, such as inhibiting AKT/Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NFκB)/NLRP3 signaling, demonstrated a potential therapeutic role in attenuating microglial-mediated injury [

220]. In addition, pericytes act as amplifiers of inflammation since friend leukemia integration 1 (Fli-1) after TBI increased pericyte apoptosis, blood-brain barrier (BBB) disruption, and pro-inflammatory cytokine release, exacerbating microglial activation [

221]. Repetitive injuries are also associated with more persistent and severe inflammation than single injuries, confirming the neuropathological progression of CTE [

222].

2.5.5. Evidence from Animal Models Linking TBI to Neurodegeneration

Preclinical models have provided important mechanistic insights into the way that TBI promotes chronic neurodegeneration, highlighting the combination of immune responses, neuronal death pathways, amyloid and tau pathology, and biomarker signatures. Ayerra et al (2025) demonstrated that adaptive immunity contributes substantially to the long-term progression of TBI. By using T-cell-deficient mice (T cell receptor beta (TCRβ)−/−δ−/−) subjected to controlled cortical impact, it was found that the absence of T-cells reduced the monocyte infiltration heavily, attenuated microglial proliferation, and enhanced an anti-inflammatory phenotype in myeloid cells [

223]. At the cellular level, evidence indicates that zipper-interacting protein kinase (ZIPK) has been implicated in mediating neuronal apoptotic pathways following TBI. In both controlled cortical impact models and in vitro neuronal injury cases, ZIPK was upregulated in neurons, reaching a peak at two days post-injury and persisting for a week [

224]. Partial deletion of ZIPK (Zipk+/− mice) reduced neuronal death, while knockdown experiments in SH-SY5Y cells confirmed a neuroprotective effect under oxidative stress. Biomarkers from animal models have also increasingly been used since they align with preclinical findings in human TBI. In a systematic review of 74 studies, Lisi et al. (2025) reported that glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), ubiquitin terminal hydrolase L1 (UCH-L1), neurofilament light (NfL), and tau isoforms show specific temporal behavior post-injury. GFAP and UCH-L1 rose sharply within 24 hours, while NfL elevations persisted for months, demonstrating chronic axonal injury, similarly seen in humans [

225]. However, tau biomarkers rose progressively, peaking over weeks, reflecting a long-term neurodegenerative process.

Amyloid pathology has also been researched robustly in animal models, linking DAI and impaired axonal transport to amyloid-beta accumulation. Rodent and swine studies showed that intra-axonal amyloid precursor protein (APP) accumulates as an early and consistent response to TBI, with amyloid-beta formation presenting more slowly. In APP-transgenic mice models, TBI induced elevations in Aβ levels, peaking within hours, while in swine rotational acceleration models, intra-axonal Aβ and diffuse plaque deposition were observed within 3-10 days, persisting for months [

203,

226]. In addition, ApoE genotype studies indicated that APOε4-expresssing mice showed earlier and more pronounced Aβ deposition than ApoE3. [

227] Uryu et al. (2002) demonstrated that repetitive but not single mild TBI in Tg2576 mice accelerated Aβ deposition, lipid peroxidation, and cognitive dysfunction. At 16 weeks post-trauma, repetitive TBI animals exhibited higher isoprostane levels, increased Aβ plaques, and memory impairment, whereas wild-type mice did not develop amyloidosis [

228].

As a result, animal model evidence supports a temporal sequence, extending from acute biomarker release to chronic Aβ and tau accumulation, thereby providing biological plausibility mediated by immune, apoptotic, and metabolic pathways.

2.6. Causal Relationship Between TBI and AD

The link between traumatic brain injury (TBI) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is increasingly being conceptualized within a causal relationship, supported by epidemiological evidence, biological plausibility and temporality. Evidence suggests that TBI, when moderate to severe may accelerate processes leading to AD.

2.6.1. Epidemiological Evidence Linking TBI to Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease

Epidemiological studies consistently indicate that a history of a previous traumatic brain injury (TBI) confers an increased risk of late-life neurodegeneration, though the association with Alzheimer’s disease remains uncertain. A comprehensive population-based analysis found that individuals with a history of TBI exhibited a significantly elevated risk of Alzheimer disease disease-related neurodegeneration compared to age and sex- and sex-adjusted referents. A large-scale cohort study of 1,418 confirmed TBI cases and 2,836 matched controls found that TBI was associated with 32% increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (HR=1.32, 95% CI: 1.11–1.58, p = 0.002). Risk was significant for “probable” TBI (HR=1.42, 95% CI: 1.05-1.92) and “possible” TBI (HR=1.29, 95% CI: 1.02–1.62), but not for “definite” TBI (HR = 1.22, 95% CI: 0.68–2.18) [

229]. Study populations are heterogeneous, ranging from general population cohorts to at-risk groups such as active-duty military personnel, veterans, and professional rugby and football athletes, most of whom were males and exposed to repetitive head impacts (RHI). Epidemiology shows that rugby players are more likely to manifest a neurodegenerative disease compared with matched community controls [

230].

Mild symptomatic TBI is the most common injury in rugby, and repetitive head impact, which may be symptomatic, has been linked to poorer cognitive function, mental health issues, and poor sleep quality [

231]. A systematic review and meta-analysis by Snowden et al. (2020) pooled data from 21 studies and reported that individuals with a history of mTBI had nearly twice the risk of developing dementia compared to those without prior head trauma. (OR= 1.96, 95% CI 1.698-2.263) [

232].

Similarly, an umbrella systematic review confirmed that TBI across all severities is significantly associated with dementia risk (OR= 1.81, 95% Cl: 1.53- 2.14). Stratification by severity indicated that both mild (OR=1.96, 95% CI: 1.70–2.26) and moderate to severe TBI (OR=1.95, 95% CI: 1.55-2.45) carried comparable increased risk. However, the association between TBI and Alzheimer’s disease was weaker and inconsistent across studies, with some analyses reporting modest associations (RR = 1.18, 95% CI: 1.11–1.25) and others detecting no significant relationship (OR = 1.02, 95% CI: 0.91–1.15). [

233] Barnes et al. (2014) found that older U.S. Veterans with TBI history had a 60% increased risk of dementia (HR=1.57, 95% CI 1.35–1.83), with risk persisting after a mean follow-up of 9 years [

234]. Graham et al. (2025) demonstrated biomarker evidence of neurodegeneration in mid-life former rugby players, while Saltiel et al. (2024) highlighted the frequent coexistence of mixed proteinopathies (amyloid-β, tau, TDP-43, α-synuclein) in post-mortem tissue from individuals exposed to RHI [

184,

235]. Post-mortem studies demonstrated a wide range of proteinopathies after RHI/TBI, including Aβ, TDP-43, alpha-synuclein, and tau, in addition to other neuropathologies such as white matter rarefaction and vascular injury [

184]. The TRACK-TBI longitudinal study further analyzed the chronic outcomes by showing that the mTBI and mild severity TBI group survivors presented higher rates of cognitive, psychiatric, and functional decline observed years after initial injury, when compared with orthopedic trauma controls (OTCs) [

236]. Hammond et al (2004) showed progressive communicational, cognitive, and social functioning problems between 1-5 years following the insult [

237].

However, risk prediction, exposure assessment, and follow-up remain a limitation as indicated by Hanrahan et al. (2023), who presented in the review that 40% of studies reported no significant association, while 60% found increased risk or earlier dementia onset [

238]. Notably, acute severe TBI has been associated with widespread amyloid plaque pathology, but this is considered distinct from Alzheimer’s pathology [

239]. Dams O’Connor et al 2013, who followed 4200 dementia-free individuals aged 65 years or older that were evaluated biannually, with a mean follow-up of 7.4 years and the history of TBI with loss of consciousness did not find an increase in the risk for development of dementia [

240].

2.6.2. Temporality of the Relationship

One of Bradford Hill’s requirements for causation is temporality, namely that the exposure precedes the outcome. The temporal association that links TBI or RHI and the later emergence of neurodegenerative disease has been demonstrated across human and preclinical studies. Epidemiological cohorts suggest that exposure to TBI, especially when accompanied by loss of consciousness (LOC), predicts later-life dementia [

241]. The MIRAGE study, a large family-based case-control investigation involving more than 16,000 relatives, reported that head injury with LOC was associated with an odds ratio (OR) of up to 9.9 for Alzheimer’s disease (AD), a risk that persisted for decades after the initial trauma [

242]. Neuropathological and imaging studies further enhance this temporal association by demonstrating progressive structural and functional brain alterations that persist long after injury. Longitudinal morphometric analysis from the DIAGNOSE CTE research in former American football players showed cortical thinning of the hippocampus, amygdala, and frontal and temporal cortices decades after exposure, with greater atrophy in professional athletes compared to amateurs, highlighting a dose-response relationship between RHI and neurodegeneration [

243]. Similar findings were observed in a study of 185 athletes, in which longer duration in athletic career predicted gyral thinning and neuronal loss, suggesting a cumulative temporal burden of head impact exposures that leads to gyral vulnerability. Preclinical data focused on mechanistic pathway, showed in CD1 mice that a single severe TBI induced sustained brain atrophy, gliosis, reduced cerebral perfusion and accumulation of beta-amyloid and hyperphosphorylated tau, with cognitive decline presenting over a 11-month follow-up period [

244]. These data confirm that the neurodegenerative process evolves slowly after the inciting trauma, proving that temporality is a key element in this cascade. However, some prospective studies have not identified accelerated cognitive decline among TBI survivors when compared to controls. Long-term follow-up for over than a decade, incorporating amyloid and tau PET imaging in chronic TBI survivors, revealed no elevation of β-amyloid or tau compared to healthy individuals [

245]. These data showcase heterogeneity in post-TBI trajectory; nevertheless, when considered collectively, epidemiological and neuroimaging evidence support a temporal sequence establishing that injury precedes and can initiate neurodegenerative change.

2.6.3. Biological Plausibility

Biological plausibility constitutes an important criterion within Bradford Hill’s framework, emphasizing the necessity for further mechanistic and translational analyses to clarify underlying causal pathways [

246]. Evidence that stems from pathological, imaging, and preclinical studies indicates strong biological plausibility for a causal relationship between TBI and dementia. Human post-mortem studies of individuals with prior head trauma reveal a polypathology mechanism, including amyloid-β plaques, hyperphosphorylated tau, TDP-43 inclusions, and Lewy bodies, which are consistent with different neurodegenerative processes rather than a single disease pathway [

247]. In addition, former athletes with white matter rarefaction and hippocampal sclerosis were independently associated with dementia, suggesting that axonal and vascular injury are central mechanisms irrespective of tau pathology [

248]. Oxidative stress and inflammatory cascades have also been investigated under a cellular and molecular aspect. TBI-induced oxidative stress was shown to accelerate phosphorylation of tau and aggregation of amyloid-β, two core hallmarks of AD [

249]. Chronic neuroinflammation mediated through NLRP3 inflammasome activation leads to sustained release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and neuronal death, processes that are also shared with AD and CTE [

250,

251]. Neuroimaging findings suggest in vivo evidence of these mechanisms. Enlargement of perivascular spaces in mTBI survivors demonstrated impaired lymphatic clearance and resulted in the accumulation of toxic proteins [

252]. Axonal injury within the anterior internal capsulae was identified as a predictor of sleep disturbance and memory decline, indicating tract-specific vulnerability [

253]. Smaller hippocampal volumes after TBI were also reported, particularly within the CA1 region, with a stronger association in older adults, highlighting how injury interacts with aging processes to exacerbate neurodegeneration [

254]. As a conclusion, TBI initiates a cascade of vascular, axonal, inflammatory, and proteinopathic processes that lead to progressive neurodegenerative disease.

Table 1.

Comparison of post-traumatic neurodegeneration, chronic traumatic encephalopathy and Alzheimer’s disease.

Table 1.

Comparison of post-traumatic neurodegeneration, chronic traumatic encephalopathy and Alzheimer’s disease.

| |

Post-TBI Neurodegeneration |

Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) |

Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) |

| Initiating Events |

Single or repetitive TBI across the severity spectrum (mild-severe), including blast exposure |

Repetitive head impacts (RHI), often sub-concussive, associated with contact sports or military blast exposure |

Multifactorial etiology involving advanced age, genetic susceptibility (APOε4, TREM2 variants) |

| Neuroanatomical Topography |

Selective vulnerability of long association and white matter tracts, including corpus callosum, internal capsule with diffuse involvement of deep and periventricular white-matter networks |

Predominant involvement of cortical sulcal depths, especially in frontal and temporal cortices, with a characteristic perivascular distribution and extends to limbic structures and brainstem in advanced stages.

|

Early involvement of medial temporal love structures (hippocampus and entorhinal cortex), followed by spread to temporoparietal association cortices.

|

| Predominant Pathology |

Diffuse Axonal Injury and microvascular disruption. Chronic cases may demonstrate mixed proteinopathy and accumulation of tau and β- amyloid |

Pathognomonic perivascular accumulation of hyperphosphorylated tau at sulcal depths, involving both neurons and astrocytes, accompanied by frequent TDP-43 co-pathology in the medial temporal lobe, diencephalon and progressive degeneration of white matter

|

Accumulation of extracellular neuritic β-amyloid plaques and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles composed of hyperphosphorylated tau, beginning in the entorhinal cortex and hippocampus and spreading to temporoparietal and frontal association |

| Imaging |

White-matter atrophy, reduced fractional anisotropy on diffusion MRI and microbleeds on susceptibility-weighted imaging, patterns of cortical atrophy

|

Regional cortical thinning and sulcal atrophy have been described, alongside tau PET signal in characteristic sulcal and perivascular regions, while standard MRI may be non-specific |

Hippocampal and temporoparietal cortical atrophy on structural MRI, positive amyloid and tau PET, imaging consistent with established AD biomarker patterns |

These entities share overlapping features such as the tau pathology and the cortical atrophy; however, they differ in the primary initiating event, also in the anatomical distribution of the lesion and the imaging findings. Post-traumatic neurodegeneration is characterized by diffuse axonal and microvascular injury, CTE by perivascular sulcal tau pathology following the repetitive head impacts and Alzheimer’s disease by hippocampal and temporoparietal amyloid and tau deposition.

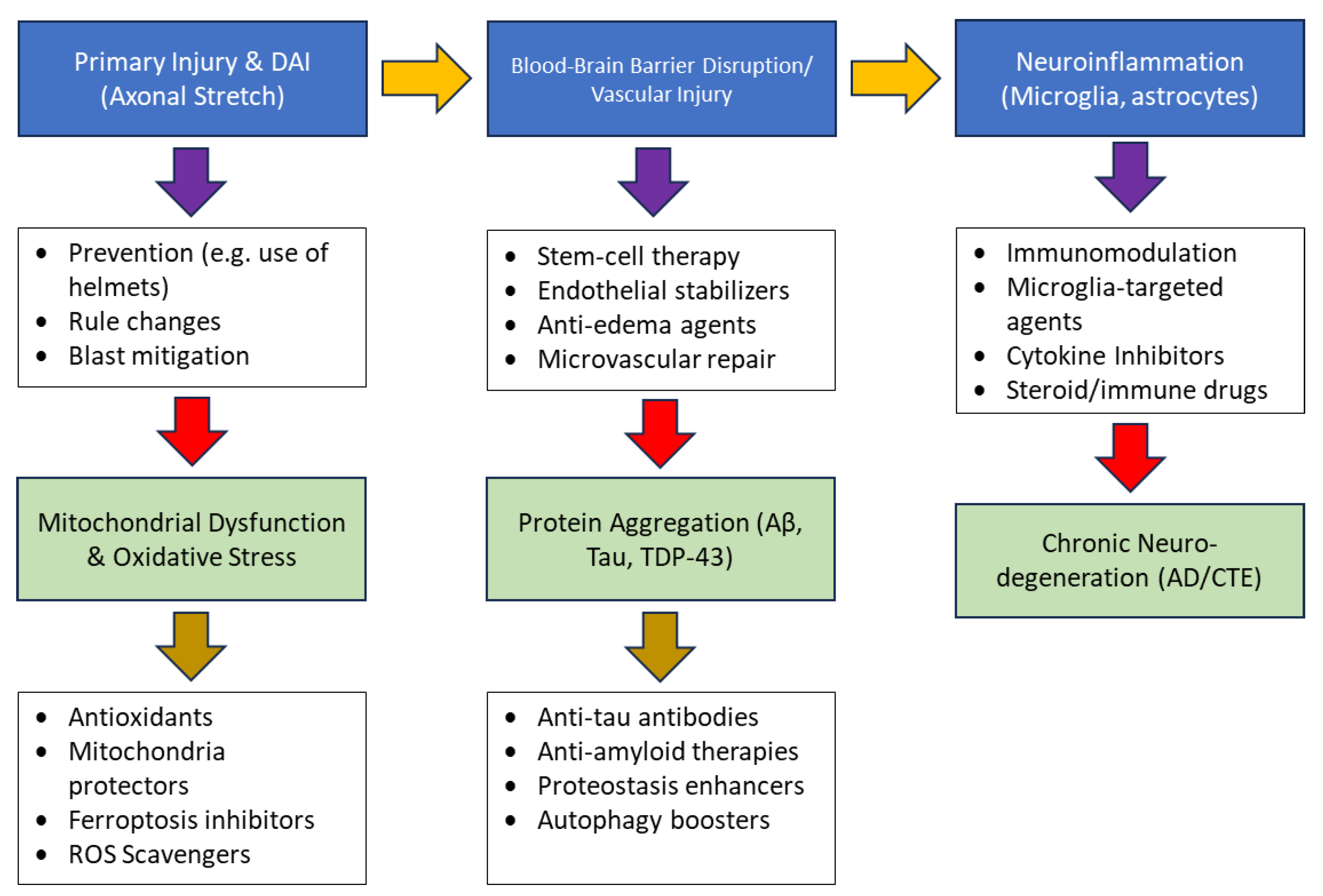

2.7. Therapeutic Interventions