Submitted:

12 January 2026

Posted:

13 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

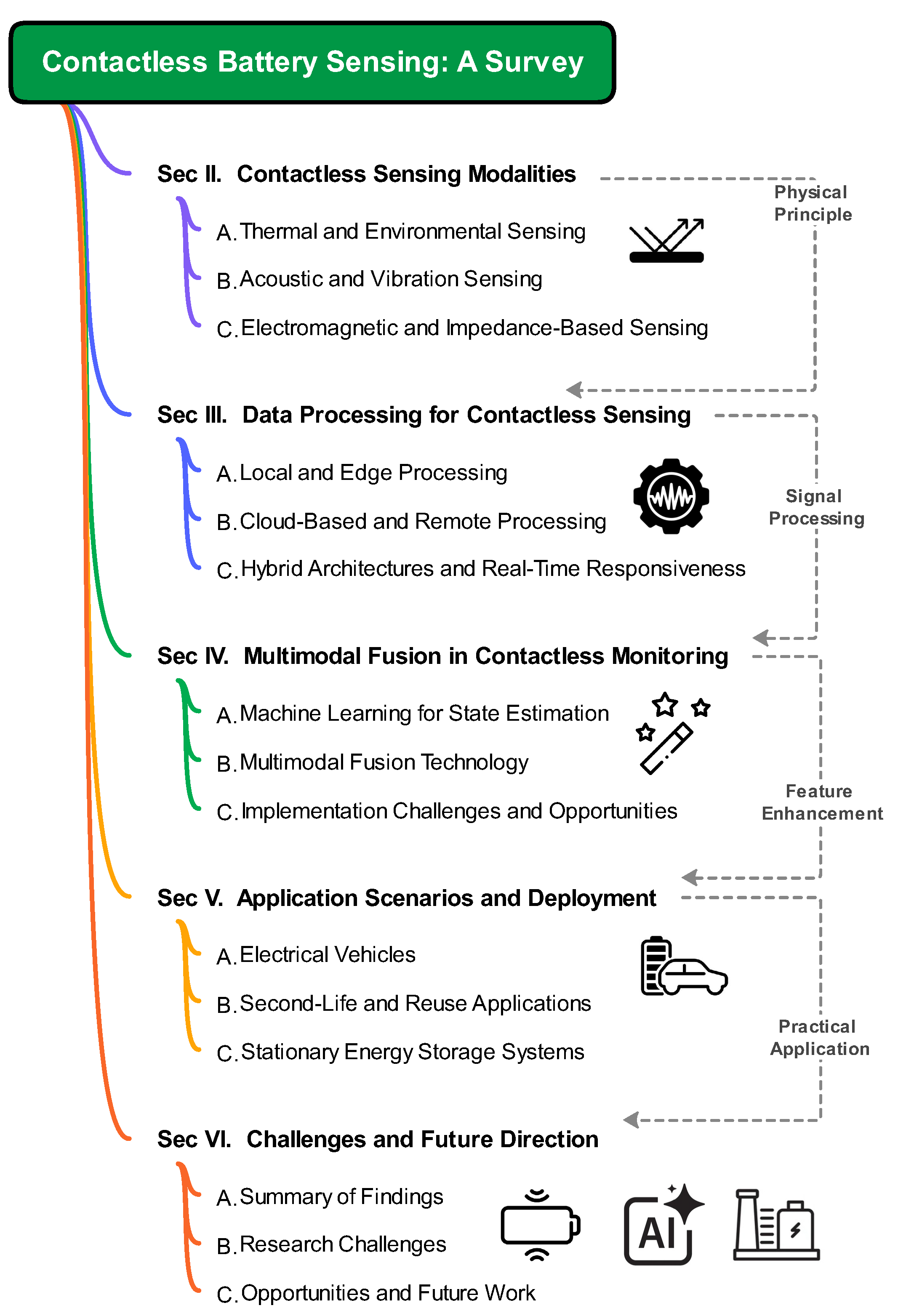

1. Introduction

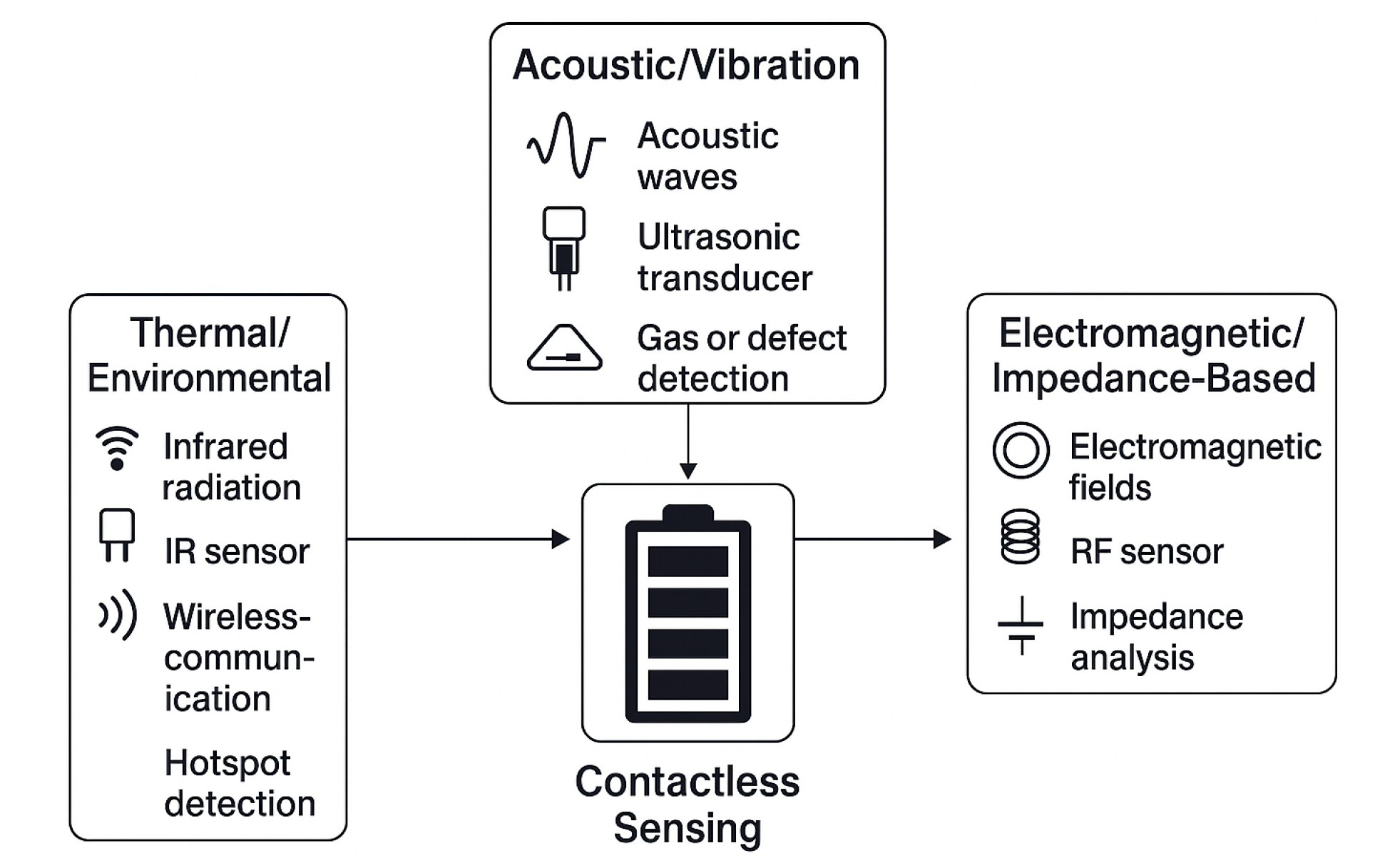

2. Contactless Sensing Modalities

2.1. Thermal and Environmental Sensing

2.2. Acoustic and Vibration Sensing

2.3. Electromagnetic and Impedance-Based Sensing

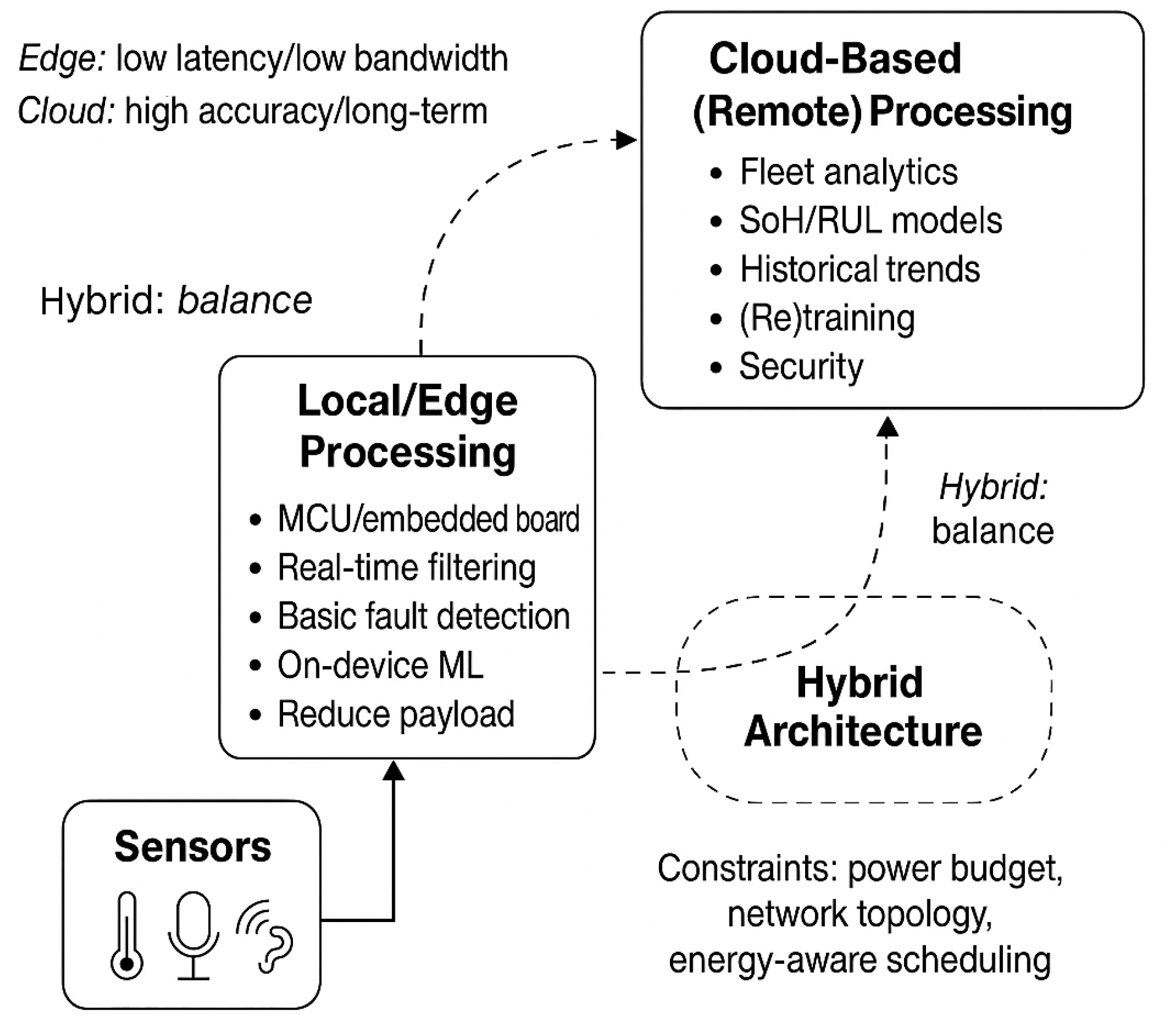

3. Data Processing for Contactless Sensing

3.1. Local and Edge Processing

3.2. Cloud-Based and Remote Processing

3.3. Hybrid Architectures and Real-Time Responsiveness

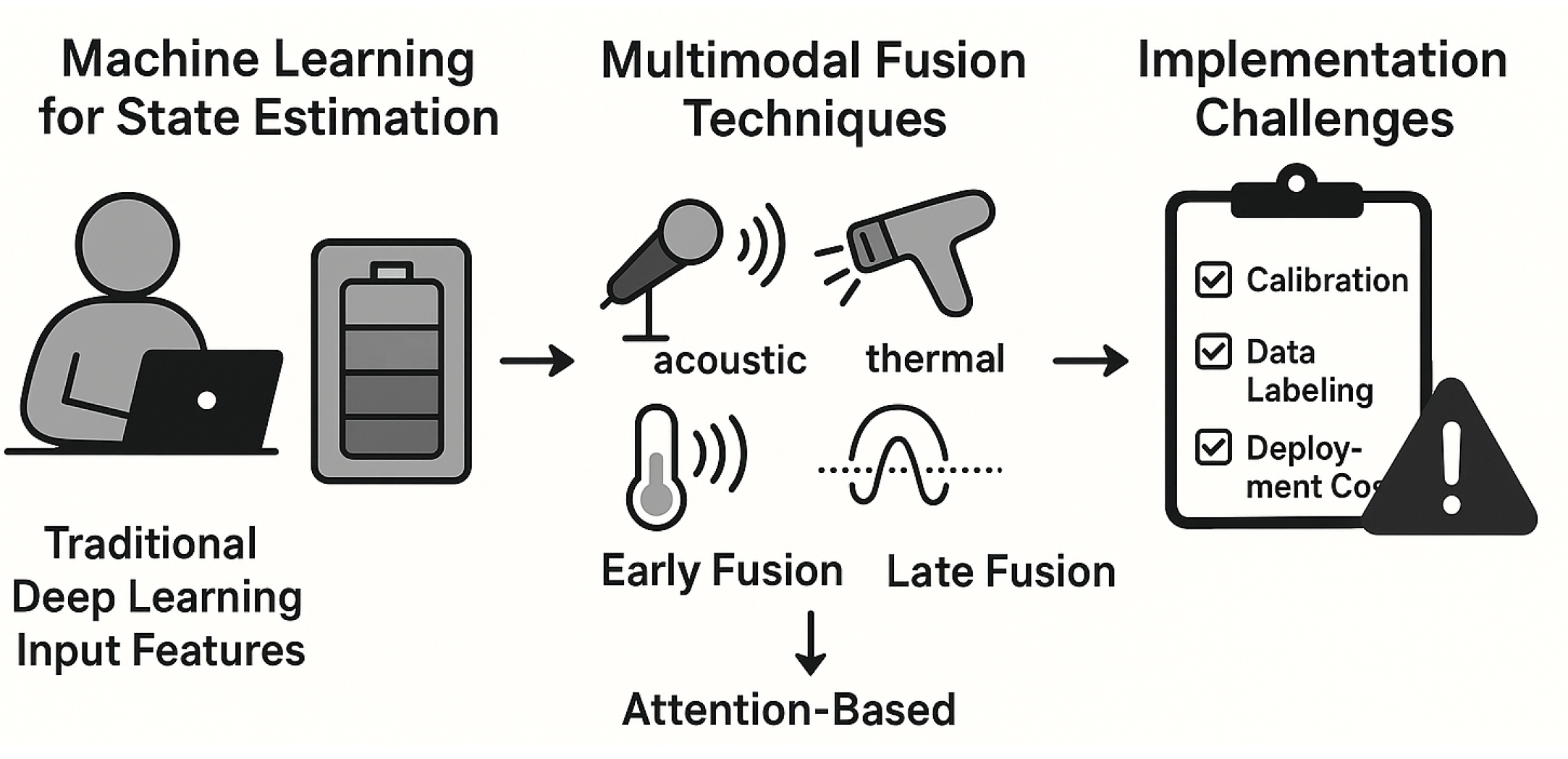

4. Multimodal Fusion in Contactless Monitoring

4.1. Machine Learning for State Estimation

4.2. Multimodal Fusion Techniques

4.3. Implementation Challenges and Opportunities

5. Application Scenarios and Deployment

5.1. Electric Vehicles

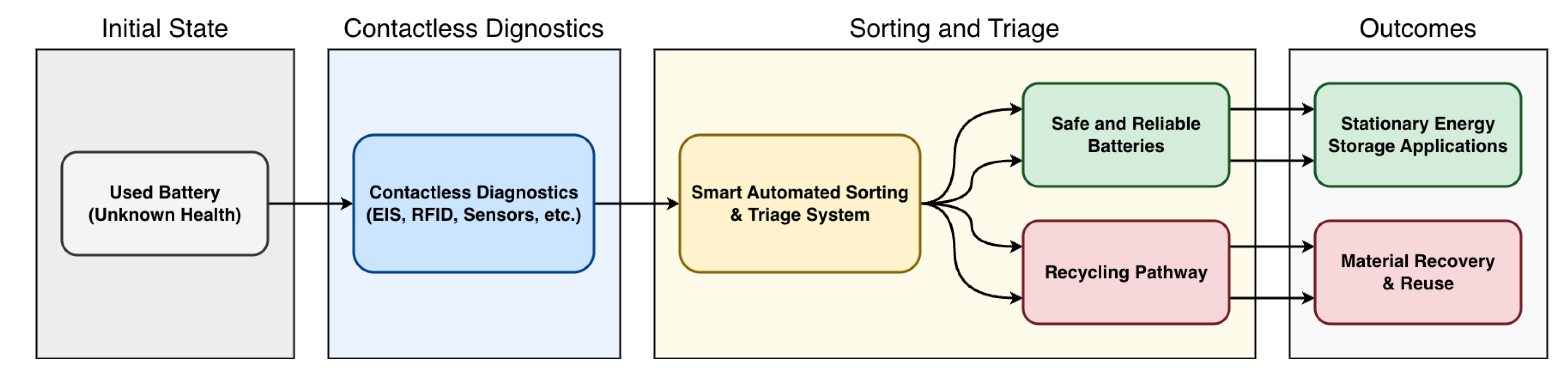

5.2. Second-Life and Reuse Applications

5.3. Stationary Energy Storage Systems

6. Challenges and Future Direction

6.1. Summary of Findings

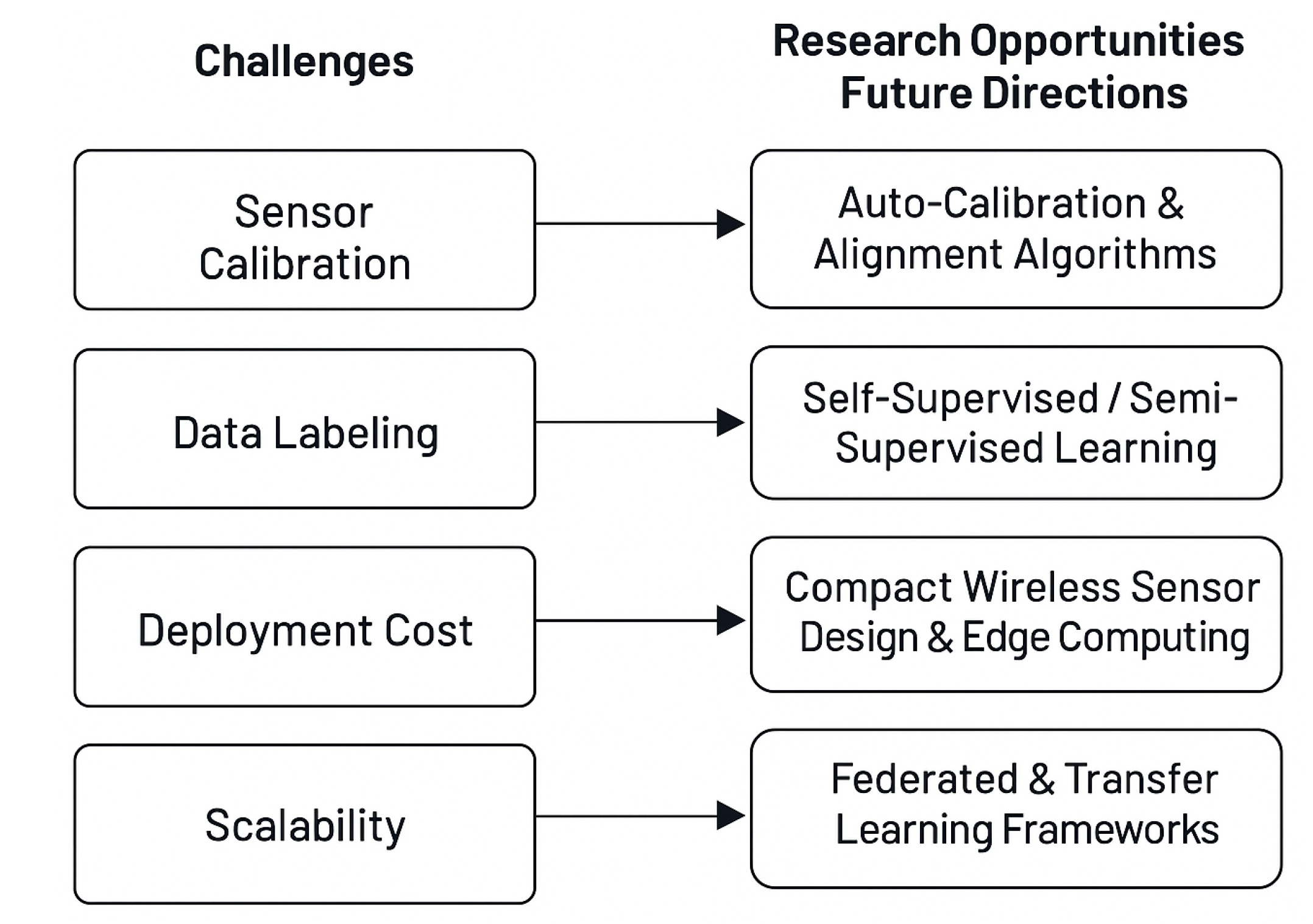

6.2. Research Challenges

6.3. Opportunities and Future Work

7. Conclusions

Nomenclature

| EV | Electrical Vehicles | WSN | Wireless Sensor Networks |

| IoT | Internet of Things | BMS | Battery Management System |

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicles | WBMS | Wireless Battery Management System |

| LIBs | Lithium-ion Batteries | EIS | Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy |

| SOC | State of Charge | SOH | State of Health |

| IR | Infrared | UHF | Ultra High Frequency |

| RFID | Radio-Frequency Identification | NFC | Near Field Communication |

| AE | Acoustic Emission | VRBs | Vanadium Redoxflow Batteries |

| MCS | Micro Control Sensor | BackCom | Backscatter Communication |

| EMI | Electromagnetic Interference | LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| MCU | Micro Control Unit | BLE | Bluetooth Low Energy |

| SLB | Second Life Battery | MAC | Medium Access Control |

| QoS | Quality of Service | ESS | Energy Storage System |

References

- Li, X.; Ye, P.; Li, J.; Liu, Z.; Cao, L.; Wang, F.-Y. From features engineering to scenarios engineering for trustworthy AI: I&I, C&C, and V&V. IEEE Intelligent Systems 2022, 37(4), 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Guo, Y.; Huo, P.; Li, Q. Redefining Vibration Sensing: AI-Driven Analytics, Self-Powered Systems, and Multi-Modal Fusion——A Review. IEEE Sensors Journal. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samanta, A.; Chowdhuri, S.; Williamson, S. S. Machine learning-based data-driven fault detection/diagnosis of lithium-ion battery: A critical review. Electronics 2021, 10(11), 1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basic, F.; Laube, C. R.; Stratznig, P.; Steger, C.; Kofler, R. Wireless BMS architecture for secure readout in vehicle and second life applications. 2023 8th International Conference on Smart and Sustainable Technologies (SpliTech), 2023; IEEE; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Multamäki, M. Near real-time IoT data pipeline architectures. Master’s thesis, M. Multamäki, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gozuoglu, A. IoT-enhanced battery management system for real-time SoC and SoH monitoring using STM32-based programmable electronic load. Internet of Things 2025, 30, 101509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S. A. Q.; Jung, J.-W. A comprehensive state-of-the-art review of wired/wireless charging technologies for battery electric vehicles: Classification/common topologies/future research issues. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 19572–19585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, K.; Foley, A. M.; Zülke, A.; Berecibar, M.; Nanini-Maury, E.; Van Mierlo, J.; Hoster, H. E. Data-driven health estimation and lifetime prediction of lithium-ion batteries: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2019, 113, 109254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basic, E.; Sarajlic, E.; Hadzialic, M. NFC-Based Wireless Sensor for EV Battery Monitoring: Secure Data Access and Low-Power Operation. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Wireless and Mobile Communications, 2023; pp. 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Gao, W.; Fu, Y.; Mi, C. Wireless battery management systems: innovations, challenges, and future perspectives. Energies 2024, 17(13), 3277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Cho, S.; Ryu, H.; Pu, Y.; Yoo, S.-S.; Lee, M.; Hwang, K. C.; Yang, Y.; Lee, K.-Y. A Highly linear, AEC-Q100 compliant signal conditioning ic for automotive piezo-resistive pressure sensors. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2018, 65(9), 7363–7373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, B.; Xu, Y.; Feng, X. State-of-health estimation and remaining-useful-life prediction for lithium-ion battery using a hybrid data-driven method. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2020, 69(10), 10854–10867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, P.; Gidwani, L. An investigation for battery energy storage system installation with renewable energy resources in distribution system by considering residential, commercial and industrial load models. Journal of Energy Storage 2022, 45, 103493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, M.-K.; Mevawalla, A.; Aziz, A.; Panchal, S.; Xie, Y.; Fowler, M. A review of Lithium-Ion Battery Thermal runaway modeling and diagnosis Approaches. Processes 2022, 10(6), 1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Gall, G.; Montavont, N.; Papadopoulos, G. Z. Enabling IEEE 802.15.4-2015 TSCH based Wireless Network for Electric Vehicle Battery Management. 2020 IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communications (ISCC), 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Wu, H.; Bowen, C. R.; Yang, Y. Recent advances in pyroelectric materials and applications. Small 2021, 17(51). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benouakta, S.; Hutu, F.; Duroc, Y. Passive UHF RFID Yarn For Temperature Sensing Applications. 2021 IEEE International Conference on RFID Technology and Applications (RFID-TA), 2021; pp. 13–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ouyang, C.; Wang, Z.; Xu, J.; Mu, X.; Swindlehurst, A. L. Near-Field Communications: A Comprehensive Survey. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2025, 27(3), 1687–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basic, F.; Gaertner, M.; Steger, C. Secure and trustworthy NFC-Based sensor readout for battery packs in battery management systems. IEEE Journal of Radio Frequency Identification 2022, 6, 637–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, F.; Rashidzadeh, R. An overview of IoT-enabled monitoring and control systems for electric vehicles. IEEE Instrumentation & Measurement Magazine 2021, 24(3), 91–97. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.; Jiang, Z.; Yan, L.; Yang, G.; Xie, J.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Q.; Xiang, Y.; Min, H.; Peng, X. Real-time visualized battery health monitoring sensor with piezoelectric/pyroelectric poly (vinylidene fluoride-trifluoroethylene) and thin film transistor array by in-situ poling. Journal of Power Sources 2020, 467, 228367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Fernandez, J. H.; Massoud, A. A wireless battery temperature monitoring system for electric vehicle charging. 2019 IEEE SENSORS, 2019; IEEE; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, M.; Ilgin, S.; Jegenhorst, N.; Kube, R.; Püttjer, S.; Riemschneider, K.-R.; Vollmer, J. Automotive battery monitoring by wireless cell sensors. 2012 IEEE International Instrumentation and Measurement Technology Conference Proceedings, 2012; IEEE; pp. 816–820. [Google Scholar]

- Jape, V.; Deore, M.; Kulkarni, H.; Chaphekar, S.; Patel, P.; Jadhav, S. Monitoring the Battery Health in Electric Vehicles through IOT. 2024 International Conference on Intelligent Systems and Advanced Applications (ICISAA), 2024; IEEE; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Bücher, T.; Drummer, D.; Kúdelka, S.; Fink, A. Printed temperature sensor array for high-resolution thermal mapping. Scientific Reports 2022, 12(1), 14747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafadarova, V.; Malcheva, B.; Yanev, Y.; Kunev, V. A system for determining the surface temperature of batteries by means of infrared thermography. Batteries 2023, 9(10), 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, V. M.; Bhattacharya, R.; Subbarao, K. Sensor Placement With Optimal Precision for Temperature Estimation of Battery Systems. IEEE Control Systems Letters 2022, 6, 1082–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Lai, X.; Lin, X. Temperature Sensor Deployment for Scalable Battery Packs. ASME 2020 Dynamic Systems and Control Conference (p. V003T13A012), 2020; American Society of Mechanical Engineers. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, D.; Chen, Y. Q. A miniature millimeter-wave radar based contactless lithium polymer battery capacity sensing with edge artificial intelligence. 2022 18th IEEE/ASME International Conference on Mechatronic and Embedded Systems and Applications (MESA), 2022; IEEE; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Le Gall, G.; Montavont, N.; Papadopoulos, G. Z. Enabling IEEE 802.15.4-2015 TSCH based wireless network for electric vehicle battery management. 2020 IEEE symposium on computers and communications (ISCC), 2020; IEEE; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Z.; Gao, W.; Fu, Y.; Mi, C. Wireless Battery Management Systems: Innovations, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. Energies 2024, 17(13), 3471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amogne, ZE; et al. Transfer Learning Based on Transferability Measures for SOH Estimation of Lithium-Ion Batteries. Batteries 2023, 9(5), 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoq, M.; et al. Correlation of acoustic emission signatures with internal changes in lithium-ion batteries. Journal of Energy Storage (in press / early access) 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; et al. Surface Temperature Assisted State of Charge Estimation Based on Infrared Thermal Imaging and GRU Model. Sensors 2025, 25(15), 4863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Smadi, M. K.; Abu Qahouq, J. A. State of Health Estimation for Lithium-Ion Batteries Based on Transition Frequency’s Impedance and Other Impedance Features with Correlation Analysis. Batteries 2025, 11(4), 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giazitzis, S.; et al. TinyML models for SoH estimation of lithium-ion batteries leveraging EIS measurements. Journal of Power Sources (in press / early access) 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ju, L.; Geng, G.; Jiang, Q. Data-driven state-of-health estimation for lithium-ion battery based on aging features. Energy 2023, 274, 127378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; et al. State-of-Health Estimation for Lithium-Ion Battery via an Improved RVFL Model. Journal of Energy Storage 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, J. Health State Prediction of Lithium-Ion Battery Based on Improved Sparrow Search Algorithm and Support Vector Regression (ISSA-SVR). Energies 2024, 17(22), 5671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, H. State-of-health estimation method for fast-charging lithium-ion batteries based on Sparse Gaussian Process Regression (SGPR). Reliability Engineering & System Safety 2024, 243, 109164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Xu, J.; Zhu, Y. LSTM-based estimation of lithium-ion battery SOH using data characteristics and spatio-temporal attention. PLOS ONE 2024, 19(12), e0312856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedláčková, E.; Pražanová, A.; Plachỳ, Z.; Klusoňová, N.; Knap, V.; Dušek, K. Acoustic Emission Technique for Battery Health Monitoring: Comprehensive Literature Review. Batteries 2025, 11(1), 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Zang, X.; Nie, Z.; Zhong, L.; Deng, Z. D.; Wang, W. Online and noninvasive monitoring of battery health at negative-half cell in all-vanadium redox flow batteries using ultrasound. Journal of Power Sources 2023, 580, 233417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Guo, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, K. Research Progress of Lithium-Ion Battery Monitoring Technology Based on Noninvasive Magnetic Induction Sensors. ACS Applied Electronic Materials 2025, 7(11), 4907–4923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichmann, B.; Sharif-Khodaei, Z. Ultrasonic guided waves as an indicator for the state-of-charge of Li-ion batteries. Journal of Power Sources 2023, 576, 233189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, B.; McCann, J. A. Failure detection methods for pipeline networks: From acoustic sensing to cyber-physical systems. Sensors 2021, 21(15), 4959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Ding, Y. Development in ambient backscatter communications. IET Microwaves, Antennas & Propagation 2023, 17(13), 963–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Hernandez Fernandez, J.; Massoud, A. A Wireless Battery Temperature Monitoring System for Electric Vehicle Charging. 2019 IEEE SENSORS, 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, T. On-board processing with AI for more autonomous and capable satellite systems; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sharmoukh, W. Redox flow batteries as energy storage systems: materials, viability, and industrial applications. RSC advances 2025, 15(13), 10106–10143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haroun, H. Available at SSRN 5195487; Extending the Lifecycle: A Comprehensive Review of Advanced Strategies for Estimating and Modeling Soh and Sop In Second-Life Batteries for Stationary Applications.

- Li, X.; Wang, Q.; Xu, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, L. Survey of Lithium-Ion Battery Anomaly Detection Methods in Electric Vehicles. IEEE Transactions on Transportation Electrification, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Dasari, H. A.; Rammohan, A. Evaluating fault detection strategies for lithium-ion batteries in electric vehicles. Engineering Research Express 2024, 6(3), 032302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigka, M.; Dritsas, E. Wireless Sensor Networks: From Fundamentals and Applications to Innovations and Future Trends. In IEEE Access; 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Gazis, A.; Papadongonas, I.; Andriopoulos, A.; Zioudas, C.; Vavouras, T. A comprehensive review of sensor technologies, instrumentation, and signal processing solutions for low-power Internet of Things systems with mini-computing devices. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.13466. [Google Scholar]

- Manikandan, S.; Sundar, S. S.; Kumaran, K.; Thirumeni, M. Design and Implementation of Battery Management And Wireless Charging in Electric Vehicles Using IoT. 2024 10th International Conference on Communication and Signal Processing (ICCSP), 2024; IEEE; pp. 194–199. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M. R.; Rahman, M.; Sarkar, T.; Islam, M.; Asadullah, M. Development of a Real-Time Battery Monitoring solution with IoT Technology for Improved Safety and Performance in Electric Machines. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science 2024, 8(3s), 1012–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basic, F.; Gaertner, M.; Steger, C. Secure and Trustworthy NFC-Based Sensor Readout for Battery Packs in Battery Management Systems. IEEE Journal of Radio Frequency Identification 2022, 6, 637–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Ding, Z.; Mo, X.; Wang, S.; Zhao, L.; Li, H.; Yang, Y.; Zou, L.; Liu, X. Design and Research of VRLA Battery Condition Monitoring Integrated Chip Based on Wireless Communication Network. 2022 Asia Power and Electrical Technology Conference (APET), 2022; IEEE; pp. 345–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; et al. Voltage relaxation-based state-of-health estimation of lithium-ion batteries using convolutional neural networks and transfer learning. Journal of Energy Storage 2023, 73, 108579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Berecibar, M. Emerging sensor technologies and physics-guided methods for monitoring automotive lithium-based batteries. Communications Engineering 2025, 4(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Hu, G.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z. Adapting amidst Degradation: cross domain li-ion battery health estimation via Physics-Guided Test-Time training. arXiv.org 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Li, C.; Hu, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, K.; Xie, Y.; Wu, R.; Song, Z. Multi-modal framework for battery state of health evaluation using open-source electric vehicle data. Nature Communications 2025, 16(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedláčková, E.; Pražanová, A.; Plachý, Z.; Klusoňová, N.; Knap, V.; Dušek, K. Acoustic Emission Technique for Battery Health Monitoring: Comprehensive Literature Review. Batteries 2025, 11(1), 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, X.; Zou, C.; Fridholm, B.; Sundvall, C.; Wik, T. Smart Sensing Breaks the Accuracy Barrier in Battery State Monitoring. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.22408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Jiang, Z.; Yan, L.; Yang, G.; Xie, J.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Q.; Xiang, Y.; Min, H.; Peng, X. Real-time visualized battery health monitoring sensor with piezoelectric/pyroelectric poly (vinylidene fluoride-trifluoroethylene) and thin film transistor array by in-situ poling. Journal of Power Sources 2020, 467, 228367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, D.; Chen, Y. A Miniature Millimeter-Wave Radar Based Contactless Lithium Polymer Battery Capacity Sensing with Edge Artificial Intelligence. 2022 18th IEEE/ASME International Conference on Mechatronic and Embedded Systems and Applications (MESA), 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, B.; Xiong, M.; Wang, H.; Ding, W.; Jiang, P.; Hua, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, W.; Tan, R. A deep learning approach for State-of-Health estimation of Lithium-Ion batteries based on a Multi-Feature and Attention Mechanism collaboration. Batteries 2023, 9(6), 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Wu, D.; Meng, J.; Wu, J.; Wu, H. A multi-feature-based multi-model fusion method for state of health estimation of lithium-ion batteries. Journal of Power Sources 2021, 518, 230774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Roberts, I. P. Advancements in Millimeter-Wave Radar Technologies for Automotive Systems: A Signal Processing Perspective. Electronics 2025, 14(7), 1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toro, U. S.; Wu, K.; Leung, V. C. M. Backscatter Wireless Communications and Sensing in Green Internet of Things. IEEE Transactions on Green Communications and Networking 2022, 6(1), 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messing, M.; Shoa, T.; Habibi, S. Estimating battery state of health using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy and the relaxation effect. Journal of Energy Storage 2021, 43, 103210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Guo, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, K. Research Progress of Lithium-Ion Battery Monitoring Technology Based on Noninvasive Magnetic Induction Sensors. ACS Applied Electronic Materials 2025, 7(11), 4907–4923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Long, T.; Zou, M.; Sun, P.; Gong, J.; Wang, L.; Shillaber, L.; Blaabjerg, F.; Jiang, K.; Zeng, Z. Transmission Line Rogowski Coil: Isolated Current Sensor With Bandwidth Exceeding 3 GHz for Wide-Bandgap Device. IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics 2023, 38(11), 13599–13605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Lee, W. K.; Pong, P. W. T. Non-Contact Capacitive-Coupling-Based and Magnetic-Field-Sensing-Assisted Technique for Monitoring Voltage of Overhead Power Transmission Lines. IEEE Sensors Journal 2017, 17(4), 1069–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y. Research on SOC Estimation Algorithm and Battery Health Diagnosis and Monitoring System for Automotive Power Battery. 2023 3rd Asia-Pacific Conference on Communications Technology and Computer Science (ACCTCS), 2023; IEEE; pp. 38–44. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Huang, Q.; Guo, H.; Zhang, X.; Wang, K.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, H.; Xu, J.; Tashiro, Y.; Li, Z.; et al. Contactless sensor for real-time monitoring of lithium battery external short circuit based on magnetoelectric elastomer composites. Journal of Power Sources 2024, 589, 233776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, S.; Ma, X.-Y.; Jiang, J.; Yang, X.-G. Advancing smart Lithium-ion batteries: a review on multi-physical sensing technologies for Lithium-ion batteries. Energies 2024, 17(10), 2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, M.; Yu, J.; Yang, P.; Yue, S.; Zhou, R. Selective Domain Adaptation Network for Lithium-ion Battery Health Monitoring. 2023 IEEE International Conference on Prognostics and Health Management (ICPHM), 2023; IEEE; pp. 112–118. [Google Scholar]

- Messing, M.; Shoa, T.; Habibi, S. Estimating battery state of health using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy and the relaxation effect. Journal of Energy Storage 2021, 43, 103210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, X.; Zou, C.; Fridholm, B.; Sundvall, C.; Wik, T. Smart sensing breaks the accuracy barrier in battery state monitoring. Energy Storage Materials 2025, 104410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, D.; Chen, Y. A miniature millimeter-wave radar based contactless lithium polymer battery capacity sensing with edge artificial intelligence. 2022 18th IEEE/ASME International Conference on Mechatronic and Embedded Systems and Applications (MESA), 2022; IEEE; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Le Gall, G.; Montavont, N.; Papadopoulos, G. Z. Enabling IEEE 802.15. 4-2015 TSCH based wireless network for electric vehicle battery management. 2020 IEEE symposium on computers and communications (ISCC), 2020; IEEE; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Haldar, S.; Gol, S.; Mondal, A.; Banerjee, R. IoT-enabled advanced monitoring system for tubular batteries: Enhancing efficiency and reliability. E-Prime-Advances in Electrical Engineering, Electronics and Energy 2024, 9, 100709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y. Research on SOC Estimation Algorithm and Battery Health Diagnosis and Monitoring System for Automotive Power Battery. 2023 3rd Asia-Pacific Conference on Communications Technology and Computer Science (ACCTCS), 2023; IEEE; pp. 38–44. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.-H.; Wu, F.-C.; Lin, H.-W. Design and implementation of esp32-based edge computing for object detection. Sensors 2025, 25(6), 1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ping, J. M.; Nixon, K. J. Simulating Battery-Powered TinyML Systems Optimised using Reinforcement Learning in Image-Based Anomaly Detection. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.05106. [Google Scholar]

- Alamu, R.; Karkala, S.; Hossain, S.; Krishnapatnam, M.; Aggarwal, A.; Zahir, Z.; Pandhare, H. V.; Shah, V. Efficient TinyML Architectures for Anomaly Detection in Industrial IoT Sensors. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, M.; Ilgin, S.; Jegenhorst, N.; Kube, R.; Püttjer, S.; Riemschneider, K.-R.; Vollmer, J. Automotive battery monitoring by wireless cell sensors. 2012 IEEE International Instrumentation and Measurement Technology Conference Proceedings, 2012; pp. 816–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jape, V.; Deore, M.; Kulkarni, H.; Chaphekar, S.; Patel, P.; Jadhav, S. Monitoring the Battery Health in Electric Vehicles through IOT. 2024 International Conference on Intelligent Systems and Advanced Applications (ICISAA), 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; et al. Onboard predictive health management for EV lithium-ion batteries using hybrid models. IEEE Transactions on Transportation Electrification 2023, 9(3), 3502–3513. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, N.; Zhou, J.; Bai, Q.; Wang, J. Study on the Fast Testing Method for the Health Status of Power Battery in Electric Vehicles. 2023 5th International Academic Exchange Conference on Science and Technology Innovation (IAECST), 2023; pp. 1307–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; et al. New energy electric vehicle battery health prediction using vibration signals and clustering algorithms. Heliyon 2024, 10(2), e23562. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. D. Fast real-time state-of-health estimation using sparse model identification (SINDy). Journal of Intelligent & Robotic Systems 2025, 108(4), 2274. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Chen, B.; Wang, T.; Zheng, J.; Lin, Z. Battery Health Assessment and Life Prediction in Battery Management System. 2022 3rd International Conference on Electronic Communication and Artificial Intelligence (IWECAI), 2022; pp. 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messing, M.; Shoa, T.; Habibi, S. Estimating battery state of health using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy and the relaxation effect. Journal of Energy Storage 2021, 43, 103210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, F.; Rashidzadeh, R. An Overview of IoT-Enabled Monitoring and Control Systems for Electric Vehicles. IEEE Instrumentation & Measurement Magazine 2021, 24(3), 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Lee, C.; Ochoa, J. J.; Lee, H.; Kim, K.; Park, J.-H. Hybrid Bar-Delta Filter-Based Health Monitoring for Multicell Lithium-Ion Batteries using an Internal Short-Circuit Cell Model. 2021 IEEE 12th International Symposium on Power Electronics for Distributed Generation Systems (PEDG), 2021; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basic, F.; Gaertner, M.; Steger, C. Secure and Trustworthy NFC-Based Sensor Readout for Battery Packs in Battery Management Systems. IEEE Journal of Radio Frequency Identification 2022, 6, 637–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Gall, G.; Montavont, N.; Papadopoulos, G. Z. Enabling IEEE 802.15.4-2015 TSCH based Wireless Network for Electric Vehicle Battery Management. 2020 IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communications (ISCC), 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, D.; Chen, Y. A Miniature Millimeter-Wave Radar Based Contactless Lithium Polymer Battery Capacity Sensing with Edge Artificial Intelligence. 2022 18th IEEE/ASME International Conference on Mechatronic and Embedded Systems and Applications (MESA), 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, X.; Zou, C.; Fridholm, B.; Sundvall, C.; Wik, T. Smart sensing breaks the accuracy barrier in battery state monitoring. Energy Storage Materials 2025, 104410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. D.; Seo, D.; Shin, J.; Bang, H. Fast Real-Time State-of-Health Estimation Method for Lithium-ion Battery using Sparse Identification of Nonlinear Dynamics. Journal of Intelligent & Robotic Systems 2025, 111(3), 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Z.; Gao, W.; Fu, Y.; Mi, C. Wireless battery management systems: innovations, challenges, and future perspectives. Energies 2024, 17(13), 3277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basic, F.; Gaertner, M.; Steger, C. Secure and trustworthy NFC-Based sensor readout for battery packs in battery management systems. IEEE Journal of Radio Frequency Identification 2022, 6, 637–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Fernandez, J. H.; Massoud, A. A wireless battery temperature monitoring system for electric vehicle charging. 2019 IEEE SENSORS, 2019; IEEE; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, J.; Xiao, B.; Zhong, W.; Xiao, B. A rapid detection method for the battery state of health. Measurement 2022, 189, 110502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M. R.; Rahman, M.; Sarkar, T.; Islam, M.; Asadullah, M. Development of a Real-Time Battery Monitoring solution with IoT Technology for Improved Safety and Performance in Electric Machines. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science 2024, 8(3s), 1012–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y. Research on SOC Estimation Algorithm and Battery Health Diagnosis and Monitoring System for Automotive Power Battery. 2023 3rd Asia-Pacific Conference on Communications Technology and Computer Science (ACCTCS), 2023; IEEE; pp. 38–44. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi, F.; Rashidzadeh, R. An overview of IoT-enabled monitoring and control systems for electric vehicles. IEEE instrumentation & measurement magazine 2021, 24(3), 91–97. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi, F.; Rashidzadeh, R. An overview of IoT-enabled monitoring and control systems for electric vehicles. IEEE instrumentation & measurement magazine 2021, 24(3), 91–97. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, K.; Gou, B.; Wang, Y.; Yang, S. A Transfer Learning-Based Data-Driven Method for State-of-Health Estimation of Lithium-Ion Batteries. 2024 Energy Conversion Congress & Expo Europe (ECCE Europe), 2024; IEEE; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- An, D.; Chen, Y. A miniature millimeter-wave radar based contactless lithium polymer battery capacity sensing with edge artificial intelligence. 2022 18th IEEE/ASME International Conference on Mechatronic and Embedded Systems and Applications (MESA), 2022; IEEE; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Bian, X.; Zou, C.; Fridholm, B.; Sundvall, C.; Wik, T. Smart sensing breaks the accuracy barrier in battery state monitoring. Energy Storage Materials 2025, 104410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messing, M.; Shoa, T.; Habibi, S. Estimating battery state of health using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy and the relaxation effect. Journal of Energy Storage 2021, 43, 103210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, M.; Yu, J.; Yang, P.; Yue, S.; Zhou, R. Selective Domain Adaptation Network for Lithium-ion Battery Health Monitoring. 2023 IEEE International Conference on Prognostics and Health Management (ICPHM), 2023; IEEE; pp. 112–118. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M. R.; Rahman, M.; Sarkar, T.; Islam, M.; Asadullah, M. Development of a Real-Time Battery Monitoring solution with IoT Technology for Improved Safety and Performance in Electric Machines. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science 2024, 8(3s), 1012–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Xu, Z.; Wang, Q.; Jin, Z.; Xu, Y.; Wang, C.; He, X. A brief review of key technologies for cloud-based battery management systems. Journal of Electronic Materials 2024, 53(12), 7334–7354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isa, A. A. H.; Iqbal, M. T. Remote Low-Cost Web-Based Battery Monitoring System and Control Using LoRa Communication Technology. Journal of Electronics and Electrical Engineering 2024, 134–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratama, I. P. E. W.; Mujiyanti, S. F.; Safitri, D. R.; Nanta, T. L.; Patrialova, S. N.; Kurniawan, I. A. Battery Health Monitoring System on Photovoltaic-Based Aerators in Vannamei Shrimp Pond. 2024 International Conference on Technology and Policy in Energy and Electric Power (ICTPEP), 2024; IEEE; pp. 398–402. [Google Scholar]

- Graf, F.; Watteyne, T.; Villnow, M. Monitoring performance metrics in low-power wireless systems. ICT Express 2024, 10(5), 989–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Bahnasawi, M.; Gebser, M.; Kambale, W. V.; Salem, M.; Chedjou, J. C.; Kyamakya, K. Combining Autoencoder and Cellular Neural Networks for Enhanced Direct Multi-Step Forecasting of Short and Long-Term Multivariate Time Series in Battery Health Monitoring: A Preliminary Feasibility Analysis. 2024 International Conference on Applied Mathematics & Computer Science (ICAMCS), 2024; IEEE; pp. 191–193. [Google Scholar]

- Duong, P. L. T.; Raghavan, N. Li-ion Battery Second-Life State of Health (SoH) Estimation with Polynomial Chaos. 2024 Global Reliability and Prognostics and Health Management Conference (PHM-Beijing), 2024; IEEE; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Le Gall, G.; Montavont, N.; Papadopoulos, G. Z. Enabling IEEE 802.15. 4-2015 TSCH based wireless network for electric vehicle battery management. 2020 IEEE symposium on computers and communications (ISCC), 2020; IEEE; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, Y.; Hur, J.; Lee, G.; Koo, J.; Choi, J.; Lee, S.-J.; Choi, S. EV-CAST: Interference and Energy-Aware Video Multicast Exploiting Collaborative Relays. 2019 IEEE 16th International Conference on Mobile Ad Hoc and Sensor Systems (MASS), 2019; IEEE; pp. 317–325. [Google Scholar]

- Gou, B.; Xu, Y.; Feng, X. State-of-health estimation and remaining-useful-life prediction for lithium-ion battery using a hybrid data-driven method. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2020, 69(10), 10854–10867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Kaleem, M. B.; Liu, Z.; Wu, Y.; Liu, W.; Huang, Z. IoB: Internet-of-batteries for electric Vehicles–Architectures, opportunities, and challenges. Green Energy and Intelligent Transportation 2023, 2(6), 100128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Qu, X.; Wu, Y.; Fowler, M.; Burke, A. F. Artificial intelligence-driven real-world battery diagnostics. Energy and AI 2024, 18, 100419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Panigrahi, C. K.; Debdas, S.; Varma, D. V. P.; Yadav, M. IoT Enabled Battery Status Monitoring System for Electric Vehicles. 2023 IEEE 3rd International Conference on Sustainable Energy and Future Electric Transportation (SEFET), 2023; IEEE; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.; Yao, M.; Liu, H.; Tang, Z. State of health estimation and remaining useful life prediction for lithium-ion batteries by improved particle swarm optimization-back propagation neural network. Journal of Energy Storage 2022, 52, 104750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer, J.; Lenz, E.; Gulla, D.; Bazant, M. Z.; Braatz, R. D.; Findeisen, R. Gaussian process-based online health monitoring and fault analysis of lithium-ion battery systems from field data. Cell Reports Physical Science 2024, 5(11). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ju, L.; Geng, G.; Jiang, Q. Data-driven state-of-health estimation for lithium-ion battery based on aging features. Energy 2023, 274, 127378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Song, Y.; He, C.; Xu, L. Remaining useful life prediction for lithium-ion batteries incorporating spatio-temporal information. Journal of Energy Storage 2024, 88, 111626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Hernandez Fernandez, J.; Massoud, A. A Wireless Battery Temperature Monitoring System for Electric Vehicle Charging. 2019 IEEE SENSORS, 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, D.; Chen, Y. A Miniature Millimeter-Wave Radar Based Contactless Lithium Polymer Battery Capacity Sensing with Edge Artificial Intelligence. 2022 18th IEEE/ASME International Conference on Mechatronic and Embedded Systems and Applications (MESA), 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Hernandez Fernandez, J.; Massoud, A. A Wireless Battery Temperature Monitoring System for Electric Vehicle Charging. 2019 IEEE SENSORS, 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, K.; Gou, B.; Wang, Y.; Yang, S. A Transfer Learning-Based Data-Driven Method for State-of-Health Estimation of Lithium-Ion Batteries. 2024 Energy Conversion Congress & Expo Europe (ECCE Europe), 2024; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Gall, G.; Montavont, N.; Papadopoulos, G. Z. Enabling IEEE 802.15.4-2015 TSCH based Wireless Network for Electric Vehicle Battery Management. 2020 IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communications (ISCC), 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yin, B.; Zhang, W.; Cheng, Y. Topology aware deep learning for wireless network optimization. IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications 2022, 21(11), 9791–9805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M. R.; Rahman, M.; Sarkar, T.; Islam, M.; Asadullah, M. Development of a Real-Time Battery Monitoring solution with IoT Technology for Improved Safety and Performance in Electric Machines. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science 2024, 8(3s), 1012–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, F.; Watteyne, T.; Villnow, M. Monitoring performance metrics in low-power wireless systems. ICT Express 2024, 10(5), 989–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.-H.; Jo, H.; Zhou, Q.; Nishat, T. A. H.; Wu, L. Active management of battery degradation in wireless sensor network using deep reinforcement learning for group battery replacement. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.15865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basic, F.; Gaertner, M.; Steger, C. Secure and Trustworthy NFC-Based Sensor Readout for Battery Packs in Battery Management Systems. IEEE Journal of Radio Frequency Identification 2022, 6, 637–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Ding, Z.; Mo, X.; Wang, S.; Zhao, L.; Li, H.; Yang, Y.; Zou, L.; Liu, X. Design and Research of VRLA Battery Condition Monitoring Integrated Chip Based on Wireless Communication Network. 2022 Asia Power and Electrical Technology Conference (APET), 2022; pp. 345–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M. R.; Rahman, M.; Sarkar, T.; Islam, M.; Asadullah, M. Development of a Real-Time Battery Monitoring solution with IoT Technology for Improved Safety and Performance in Electric Machines. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science 2024, 8(3s), 1012–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Ding, Z.; Mo, X.; Wang, S.; Zhao, L.; Li, H.; Yang, Y.; Zou, L.; Liu, X. Design and Research of VRLA Battery Condition Monitoring Integrated Chip Based on Wireless Communication Network. 2022 Asia Power and Electrical Technology Conference (APET), 2022; pp. 345–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Gall, G.; Montavont, N.; Papadopoulos, G. Z. Enabling IEEE 802.15.4-2015 TSCH based Wireless Network for Electric Vehicle Battery Management. 2020 IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communications (ISCC), 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Shah, A. A.; Pezaros, D. A survey of energy optimization approaches for computational task offloading and resource allocation in MEC networks. Electronics 2023, 12(17), 3548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basic, F.; Gaertner, M.; Steger, C. Secure and Trustworthy NFC-Based Sensor Readout for Battery Packs in Battery Management Systems. IEEE Journal of Radio Frequency Identification 2022, 6, 637–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jape, V.; Deore, M.; Kulkarni, H.; Chaphekar, S.; Patel, P.; Jadhav, S. Monitoring the Battery Health in Electric Vehicles through IOT. 2024 International Conference on Intelligent Systems and Advanced Applications (ICISAA), 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnum, G.; Talukder, S.; Yue, Y. On the Benefits of Early Fusion in Multimodal Representation Learning. arXiv.org 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Chen, J.; Lan, F.; Li, Y.; Feng, Y. Multiscale feature fusion approach to early fault diagnosis in EV power battery using operational data. Journal of Energy Storage 2024, 98, 112812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidheekh, S.; Tenali, P.; Mathur, S.; Blasch, E.; Natarajan, S. On the Robustness and Reliability of Late Multi-Modal Fusion using Probabilistic Circuits. 2024 27th International Conference on Information Fusion (FUSION), 2024; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Kang, M.; Kim, J.; Baek, J. Sequential application of denoising autoencoder and long-short recurrent convolutional network for noise-robust remaining-useful-life prediction framework of lithium-ion batteries. Computers & Industrial Engineering 2023, 179, 109231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valizadeh, A.; Amirhosseini, M. H. Machine learning in Lithium-Ion Battery: Applications, challenges, and future trends. SN Computer Science 2024, 5(6). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Che, Y.; Hu, X.; Sui, X.; Stroe, D.-I.; Teodorescu, R. Thermal state monitoring of lithium-ion batteries: Progress, challenges, and opportunities. Progress in Energy and Combustion Science 2023, 100, 101120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Guo, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, K. Research Progress of Lithium-Ion Battery Monitoring Technology Based on Noninvasive Magnetic Induction Sensors. ACS Applied Electronic Materials 2025, 7(11), 4907–4923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradian, J. M.; Ali, A.; Yan, X.; Pei, G.; Zhang, S.; Naveed, A.; Shehzad, K.; Shahnavaz, Z.; Ahmad, F.; Yousaf, B. Sensors Innovations for smart Lithium-Based Batteries: Advancements, opportunities, and potential challenges. Nano-Micro Letters 2025, 17(1), 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. M.; Lee, H.-T. Configuration study of next-generation BMS based on Wireless Sensor Network. International Journal of Science and Technology Research Archive 2025, 8(2), 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Z.; Li, B.; Yang, Y. Deep domain adaptation network for transfer learning of state of charge estimation among batteries. Journal of Energy Storage 2023, 61, 106812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Onori, S.; Hu, X.; Teodorescu, R. Increasing generalization capability of battery health estimation using continual learning. Cell Reports Physical Science 2023, 4(12), 101743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Peng, Q.; Che, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Li, K.; Teodorescu, R.; Widanage, D.; Barai, A. Transfer learning for battery smarter state estimation and ageing prognostics: Recent progress, challenges, and prospects. Advances in Applied Energy 2022, 9, 100117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Liu, K.; Li, K.; Widanage, W. D.; Kendrick, E.; Gao, F. Recovering large-scale battery aging dataset with machine learning. Patterns 2021, 2(8), 100302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. C. Degradation Self-Supervised Learning for Lithium-ion Battery Health Diagnostics. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.08083. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, R.; Wang, J.; Tian, Y.; Tian, J. FedCBE: A federated-learning-based collaborative battery estimation system with non-IID data. Applied Energy 2024, 368, 123534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salucci, C. B.; Bakdi, A.; Glad, I. K.; Vanem, E.; De Bin, R. A novel semi-supervised learning approach for State of Health monitoring of maritime lithium-ion batteries. Journal of Power Sources 2022, 556, 232429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, X.; Zou, C.; Fridholm, B.; Sundvall, C.; Wik, T. Smart sensing breaks the accuracy barrier in battery state monitoring. Energy Storage Materials 2025, 104410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Fan, W.; Zhu, J.; Wei, X.; Dai, H. Semi-supervised deep learning for lithium-ion battery state-of-health estimation using dynamic discharge profiles. Cell Reports Physical Science 2024, 5(1), 101763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, H.; Sarwar, S.; Kirli, D.; Shek, J. K. H.; Kiprakis, A. E. A survey of second-life batteries based on techno-economic perspective and applications-based analysis. Carbon Neutrality 2023, 2(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Khan, M. A.; Singh, S.; Sharma, R.; Onori, S. Towards a BMS2 Design Framework: Adaptive Data-driven State-of-health Estimation for Second-Life Batteries with BIBO Stability Guarantees. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.04734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezpeleta, I.; Fernández, J.; Giráldez, D.; Freire, L. Rapid and Non-Invasive SOH estimation of Lithium-Ion cells via automated EIS and EEC models. Batteries 2025, 11(9), 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignesh, S.; Che, H. S.; Selvaraj, J.; Tey, K. S. State of health indicators for second life battery through non-destructive test approaches from repurposer perspective. Journal of Energy Storage 2024, 89, 111656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, S.; Ma, R.; Zhao, Z.; Ma, G.; Su, L.; Chang, H.; Chen, Y.; Liu, H.; Liang, Z.; Cao, T.; et al. Generative learning assisted state-of-health estimation for sustainable battery recycling with random retirement conditions. Nature Communications 2024, 15(1), 54454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chacón, X. C. A.; Laureti, S.; Ricci, M.; Cappuccino, G. A review of Non-Destructive Techniques for Lithium-Ion Battery Performance Analysis. World Electric Vehicle Journal 2023, 14(11), 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Mao, Q.; Cheng, K.-W. E.; Dai, J. Recent advances in ultrasound-based battery diagnostics: A reinforcement learning perspective. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments 2025, 82, 104521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Luo, D.; Zhou, M.; Jiang, D.; Li, A. A review of online Battery Impedance Spectroscope acquisition Method based on Power Electronic System. Green Energy and Intelligent Transportation 2025, 100252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basic, F.; Laube, C. R.; Stratznig, P.; Steger, C.; Kofler, R. Wireless BMS Architecture for Secure Readout in Vehicle and Second life Applications. 2023 8th International Conference on Smart and Sustainable Technologies (SpliTech), 2023; IEEE; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasper, P.; Schiek, A.; Smith, K.; Shimonishi, Y.; Yoshida, S. Predicting battery capacity from impedance at varying temperature and state of charge using machine learning. Cell Reports Physical Science 2022, 3(12), 101184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Bridges, G. E.; Kordi, B. RFID Sensor with Integrated Energy Harvesting for Wireless Measurement of dc Magnetic Fields. Sensors 2025, 25(10), 3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Zang, X.; Nie, Z.; Zhong, L.; Deng, Z. D.; Wang, W. Online and noninvasive monitoring of battery health at negative-half cell in all-vanadium redox flow batteries using ultrasound. Journal of Power Sources 2023, 580, 233417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. A.; Thatipamula, S.; Onori, S. Onboard Health Estimation using Distribution of Relaxation Times for Lithium-ion Batteries. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2024, 58(28), 917–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Gall, G.; Montavont, N.; Papadopoulos, G. Z. Enabling IEEE 802.15. 4-2015 TSCH based wireless network for electric vehicle battery management. 2020 IEEE symposium on computers and communications (ISCC), 2020; IEEE; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Basic, F.; Gaertner, M.; Steger, C. Secure and trustworthy NFC-Based sensor readout for battery packs in battery management systems. IEEE Journal of Radio Frequency Identification 2022, 6, 637–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Zhao, X.; Ma, J.; Meng, D.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, J.; Yan, S.; Zhang, K.; Han, Z. Enhancing lithium-ion battery monitoring: A critical review of diverse sensing approaches. ETransportation 2024, 22, 100360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).