Submitted:

12 January 2026

Posted:

14 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

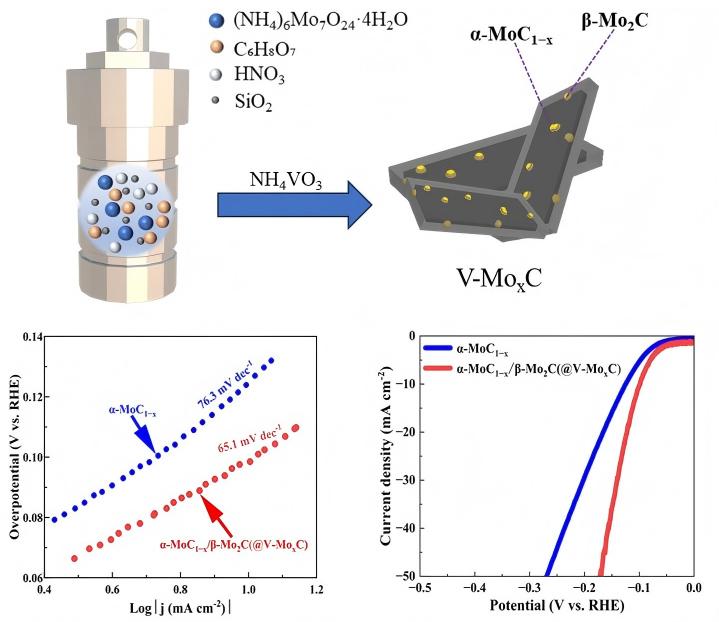

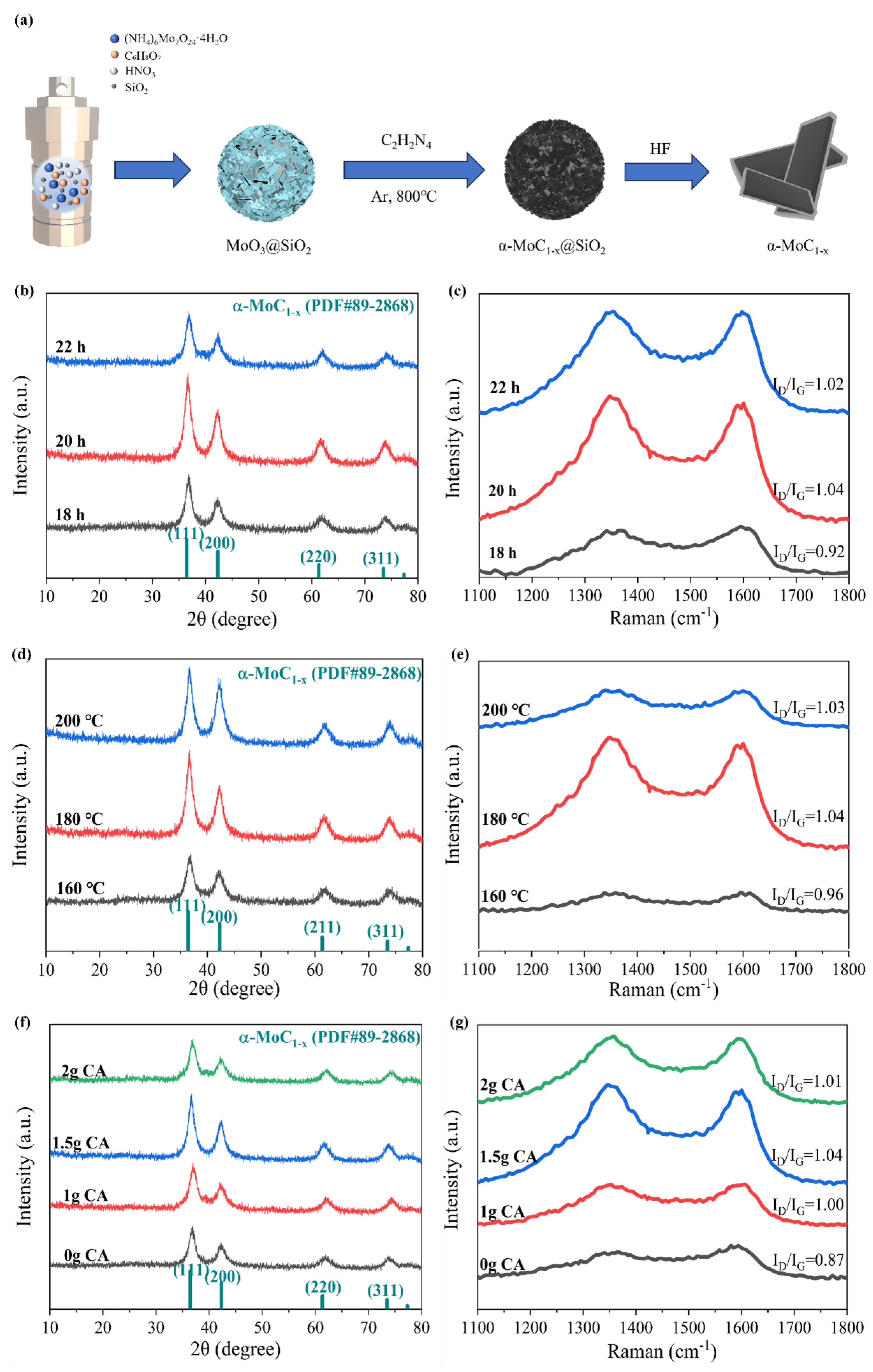

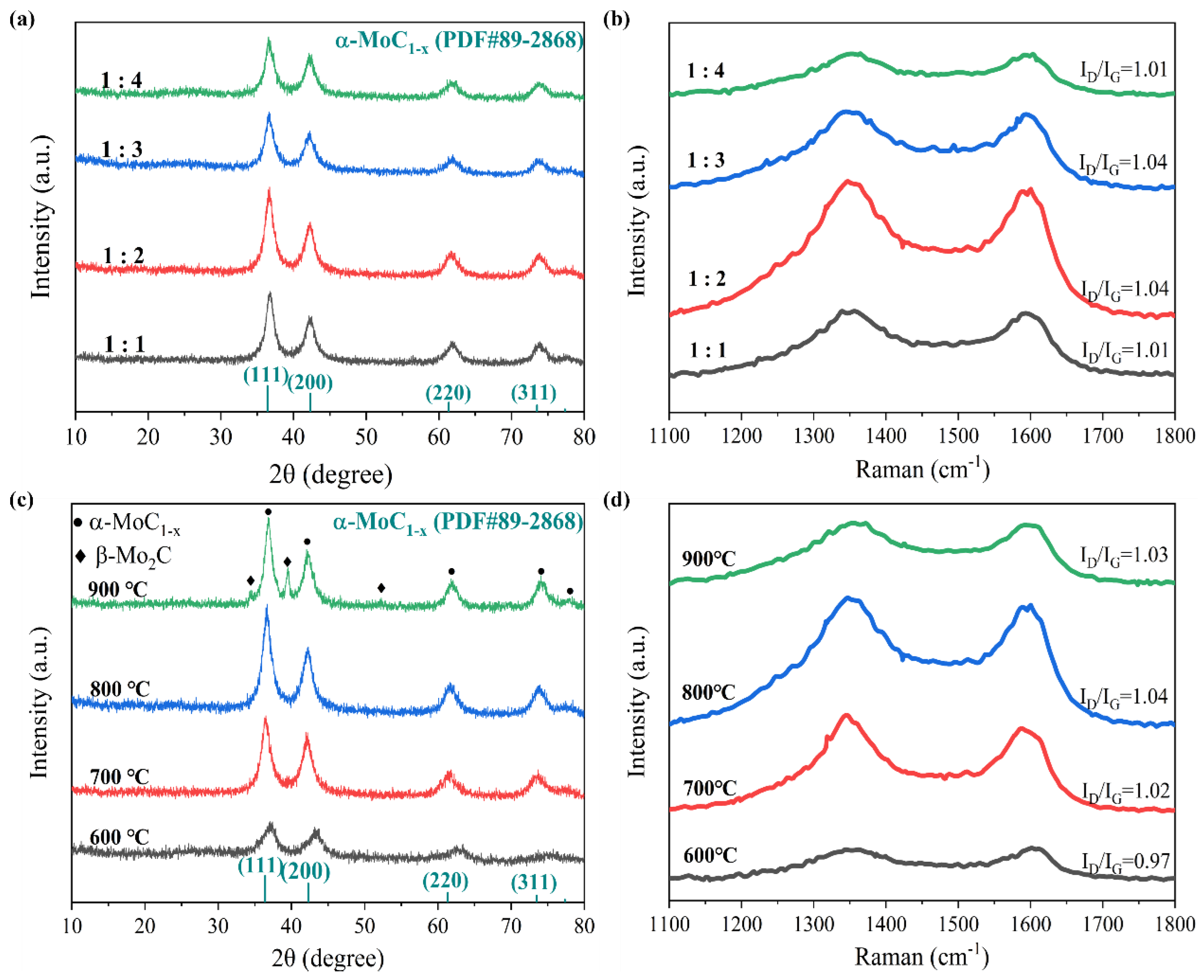

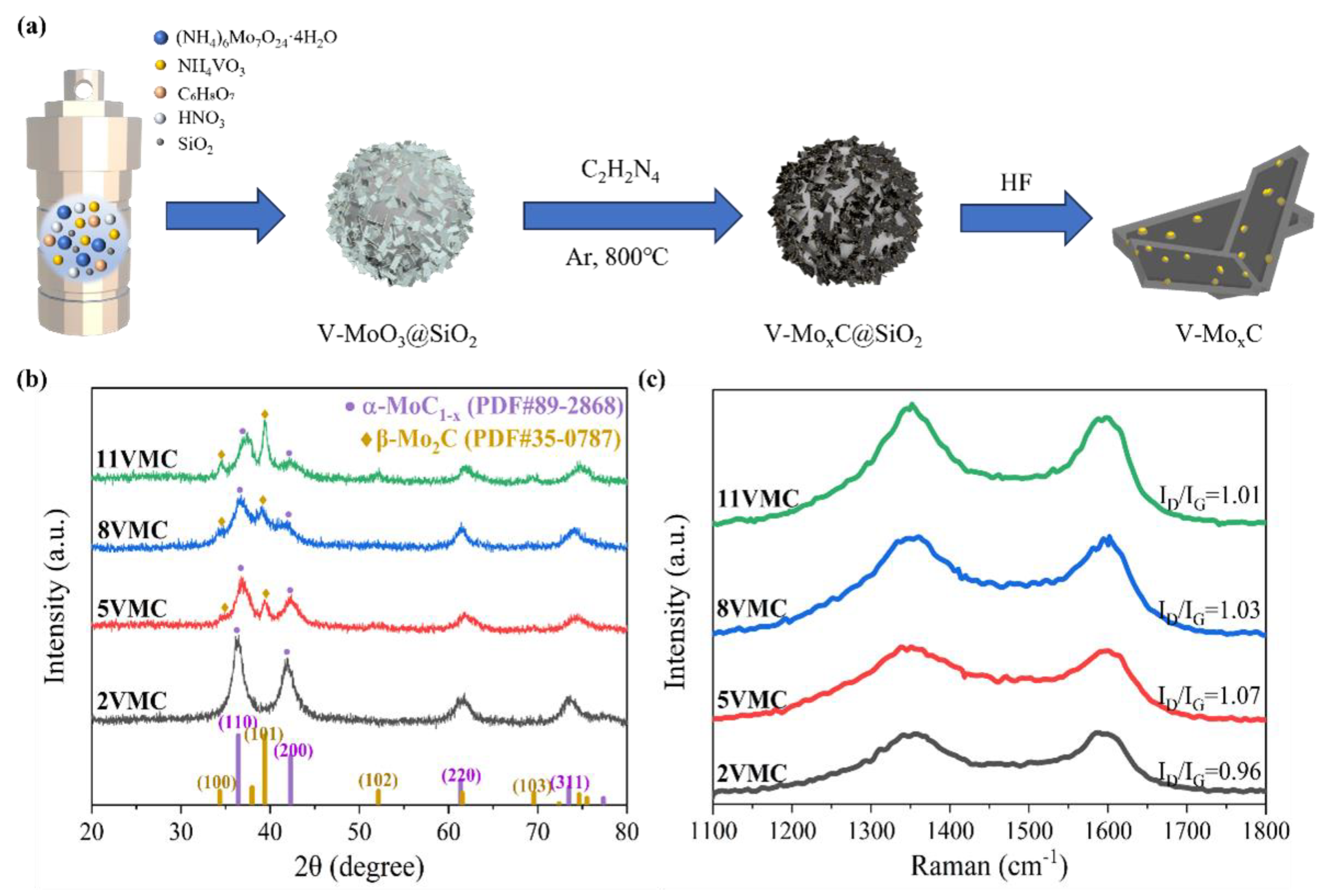

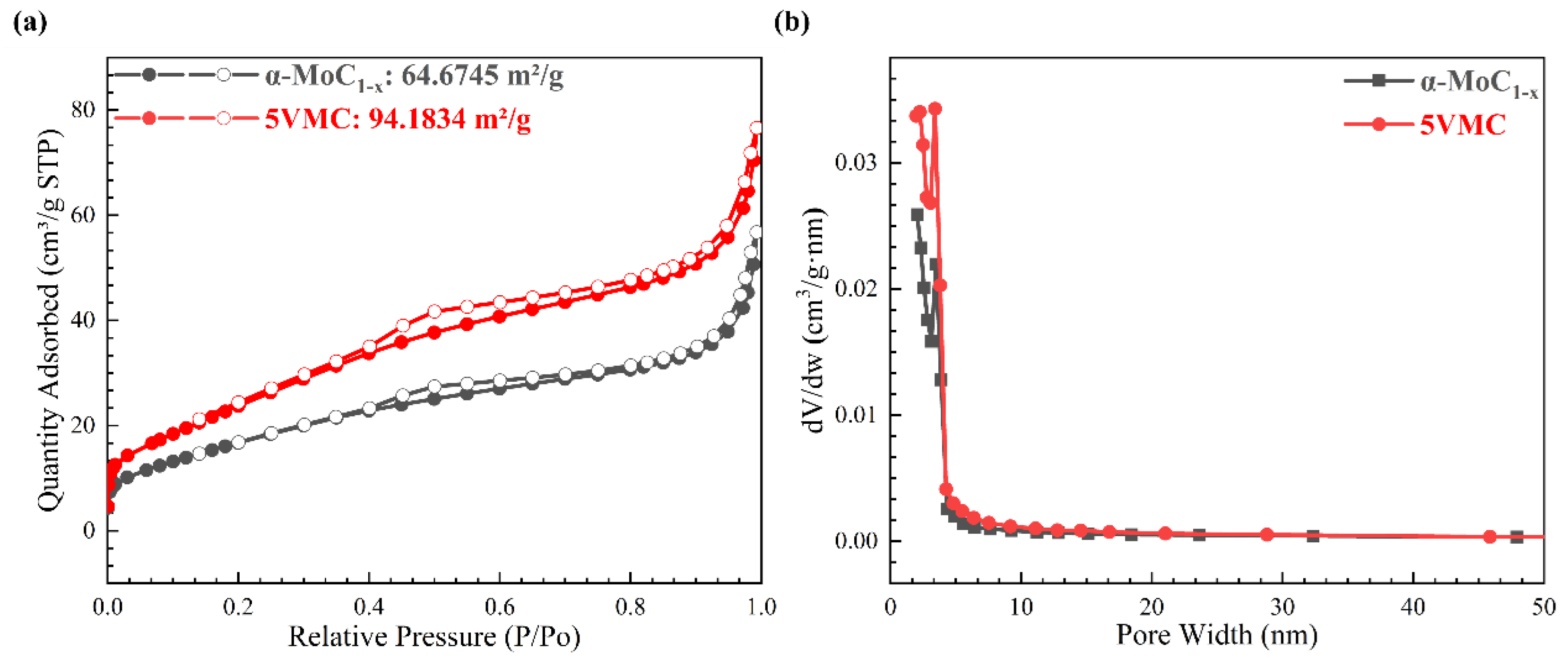

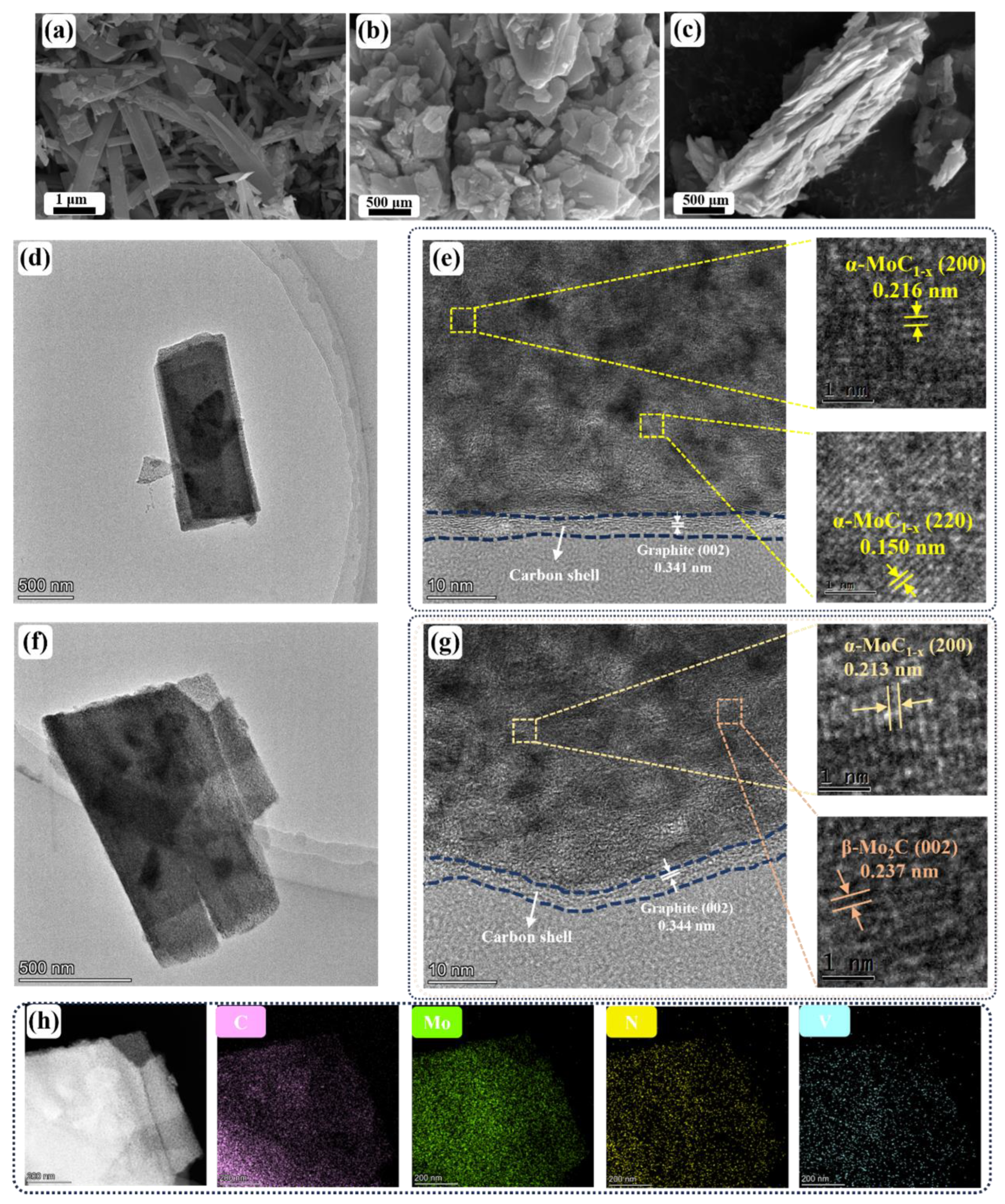

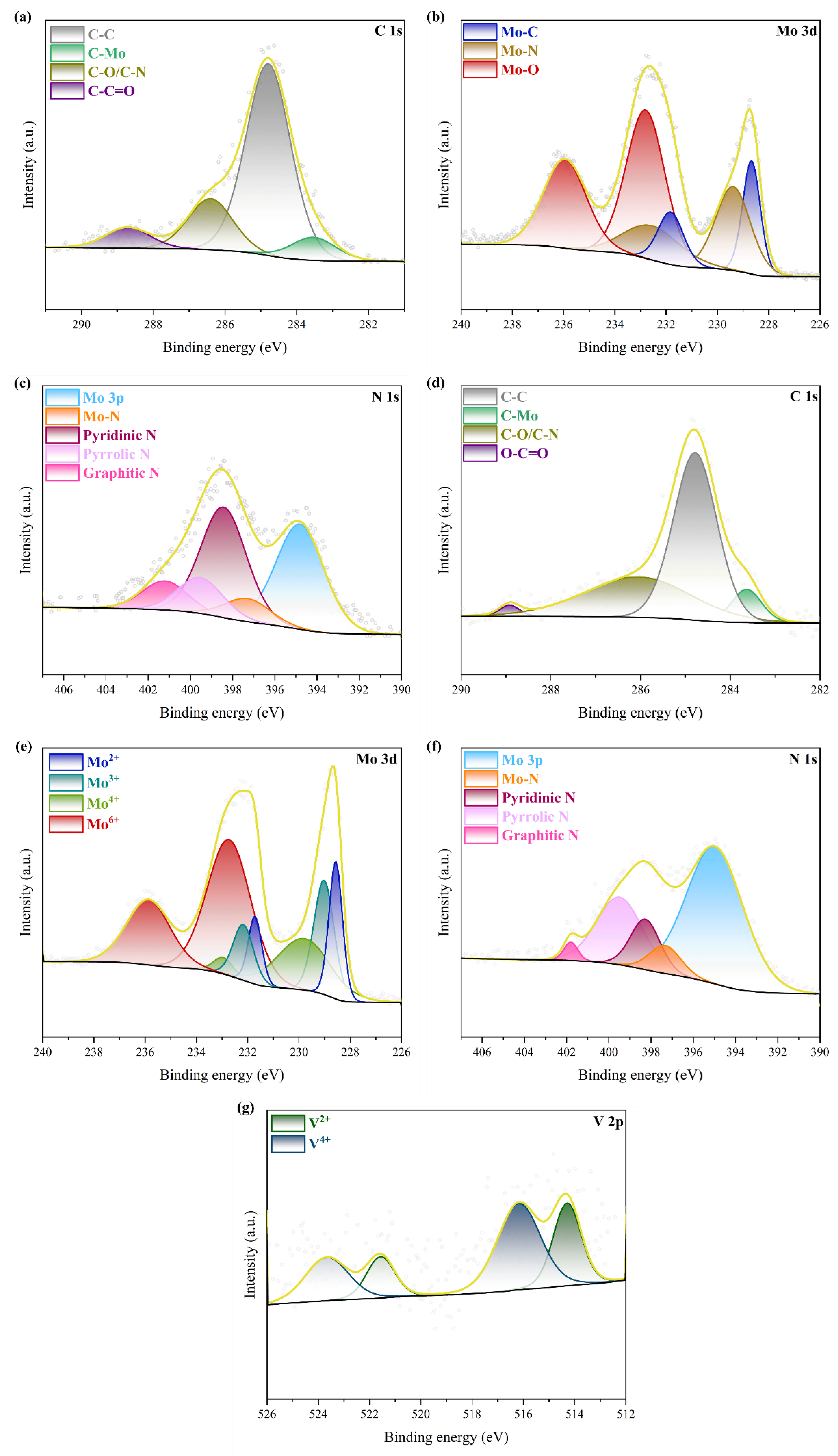

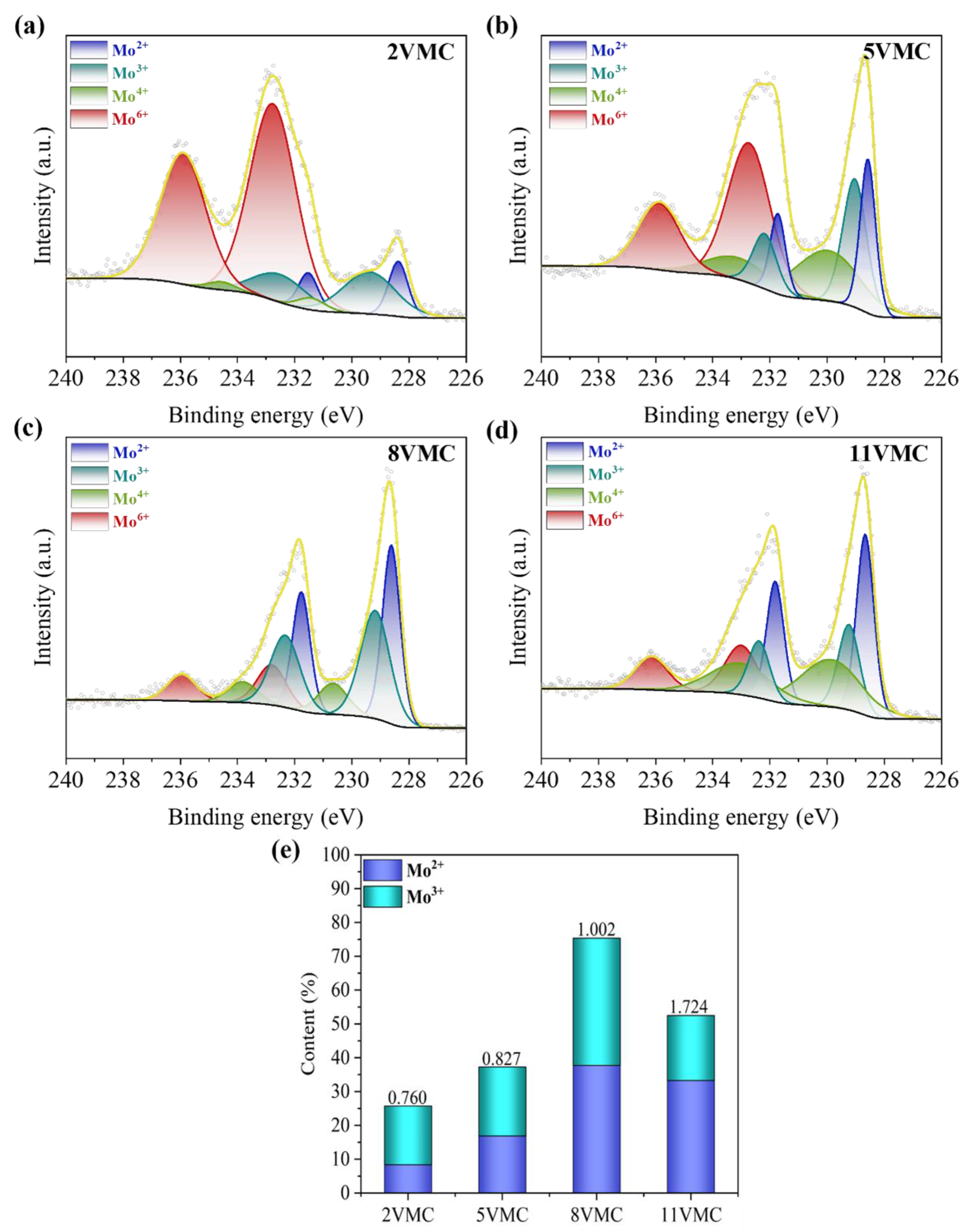

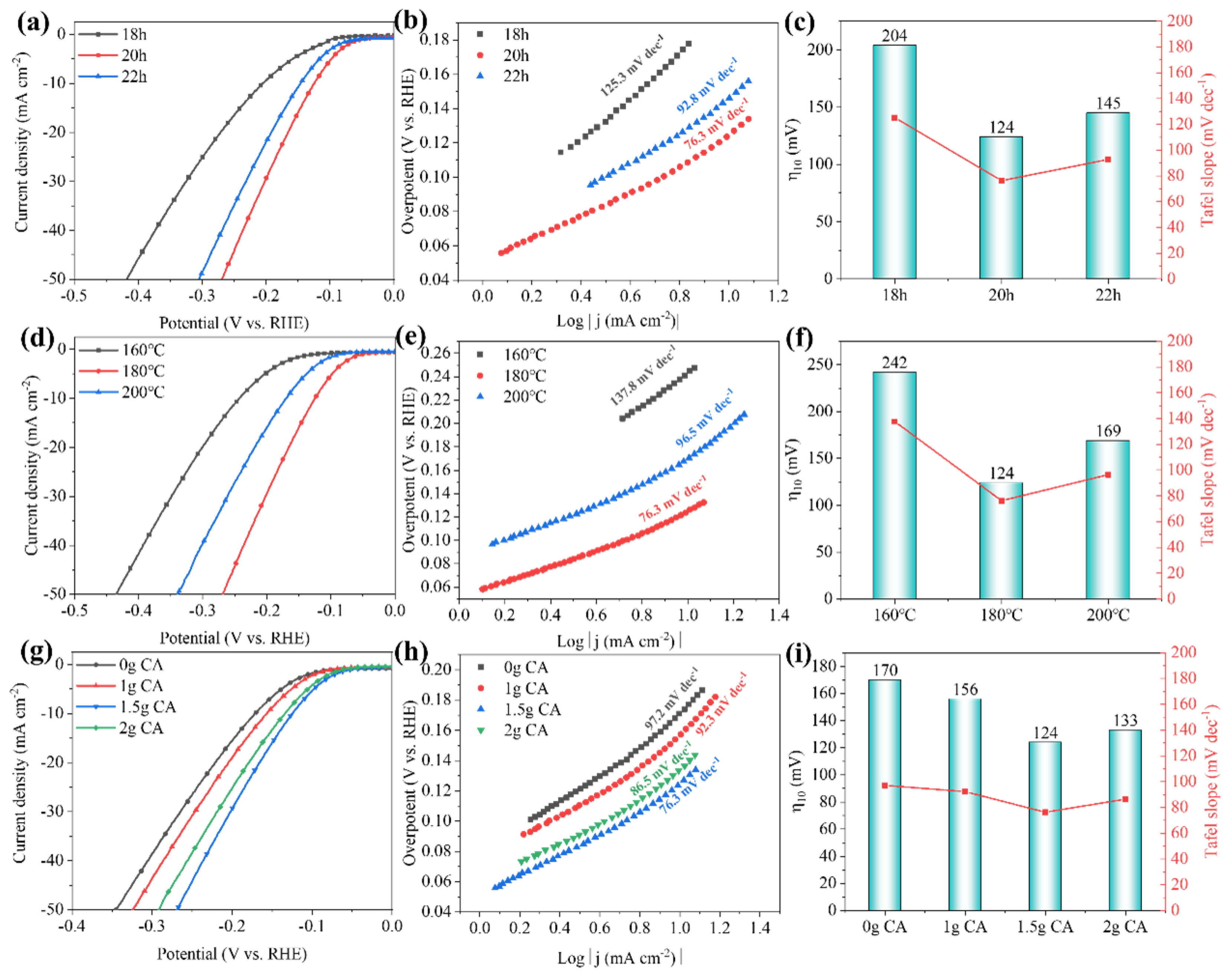

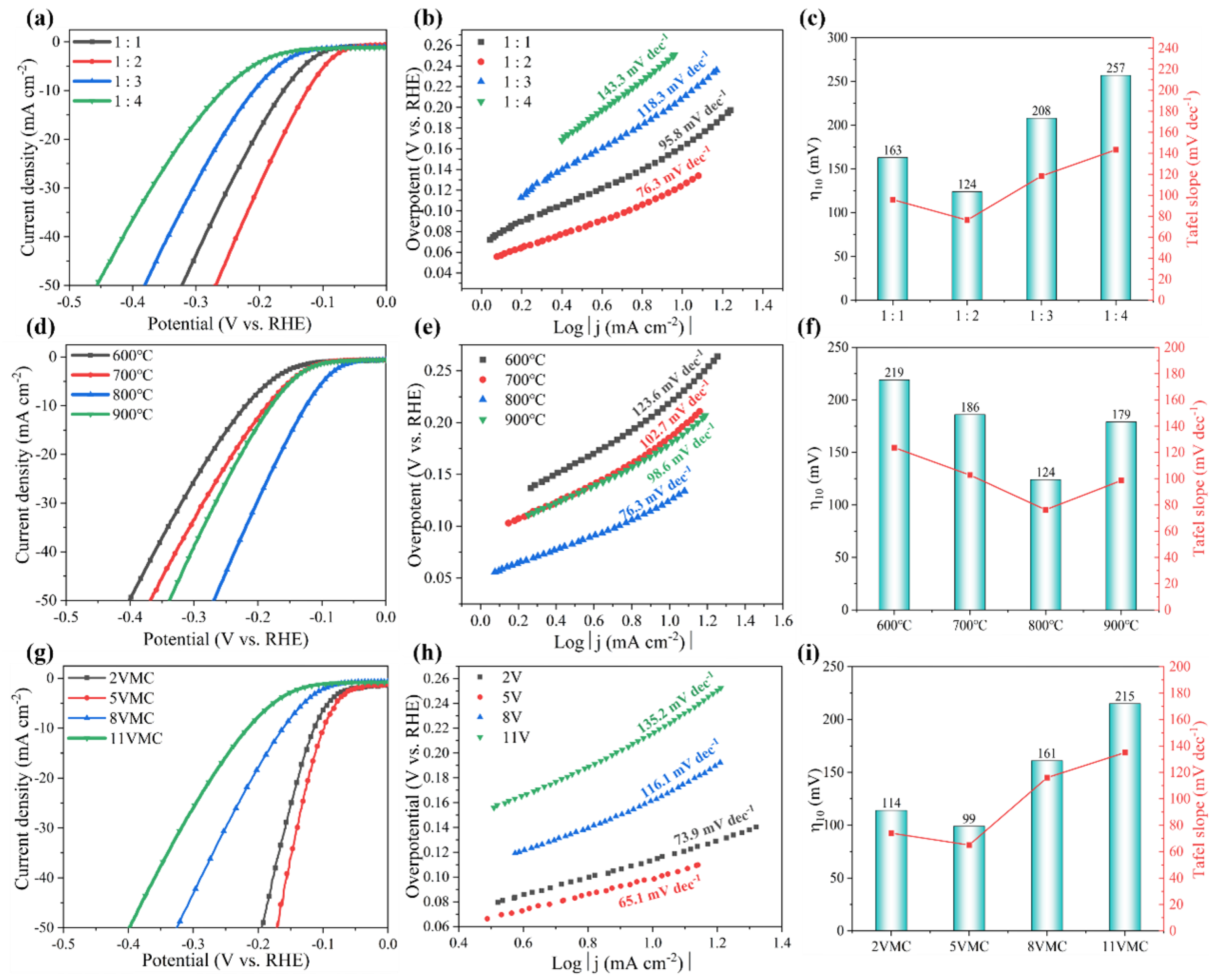

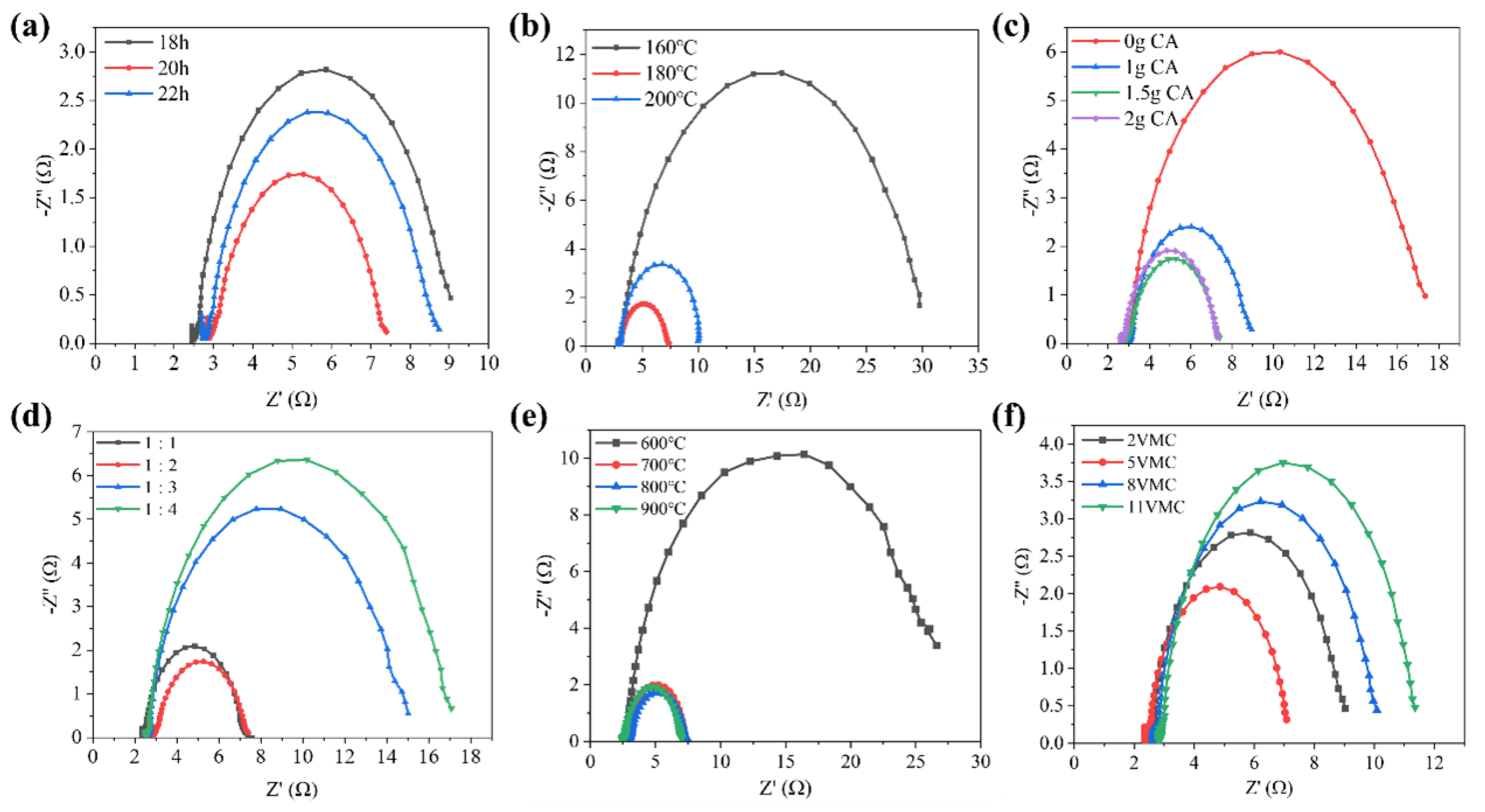

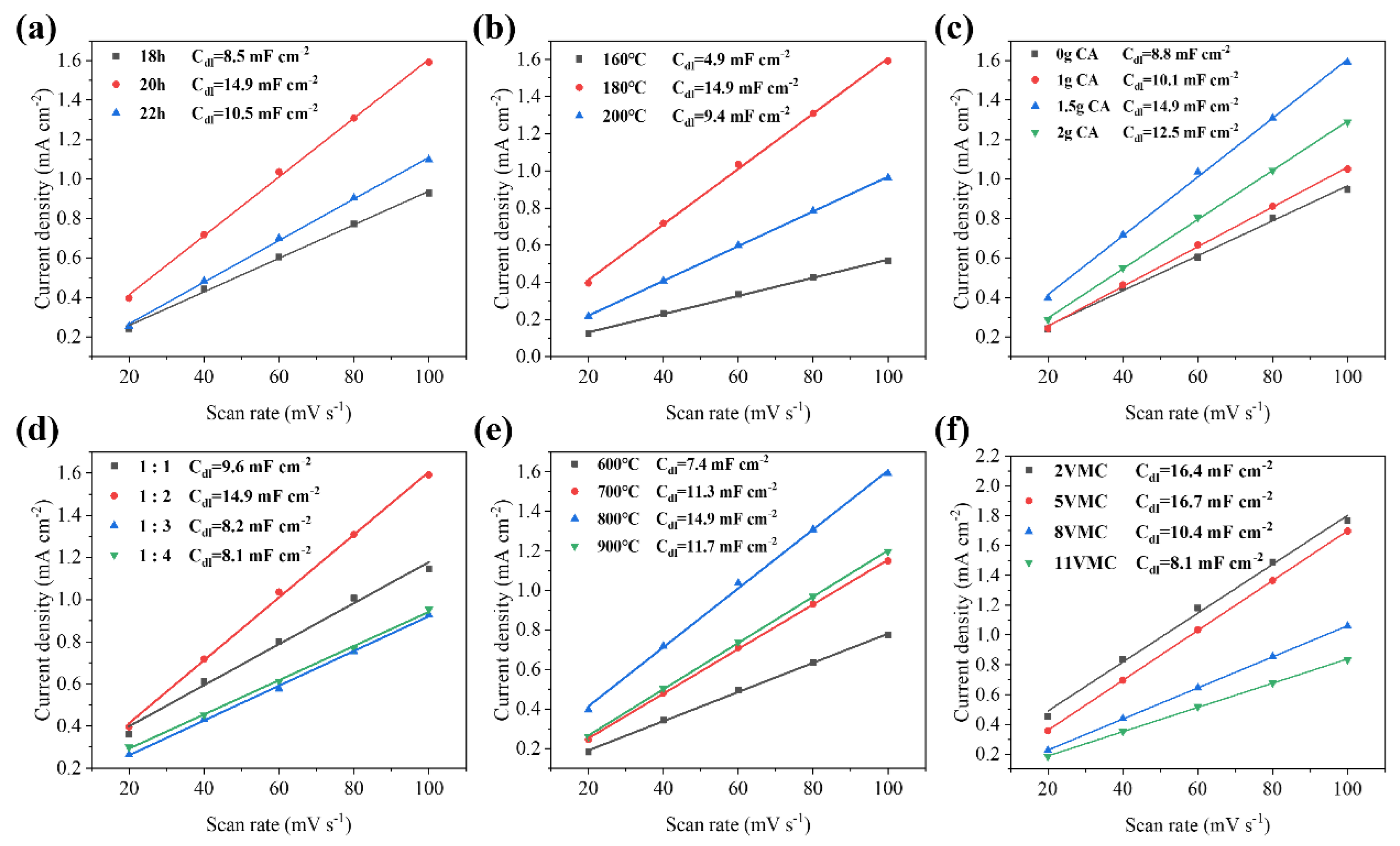

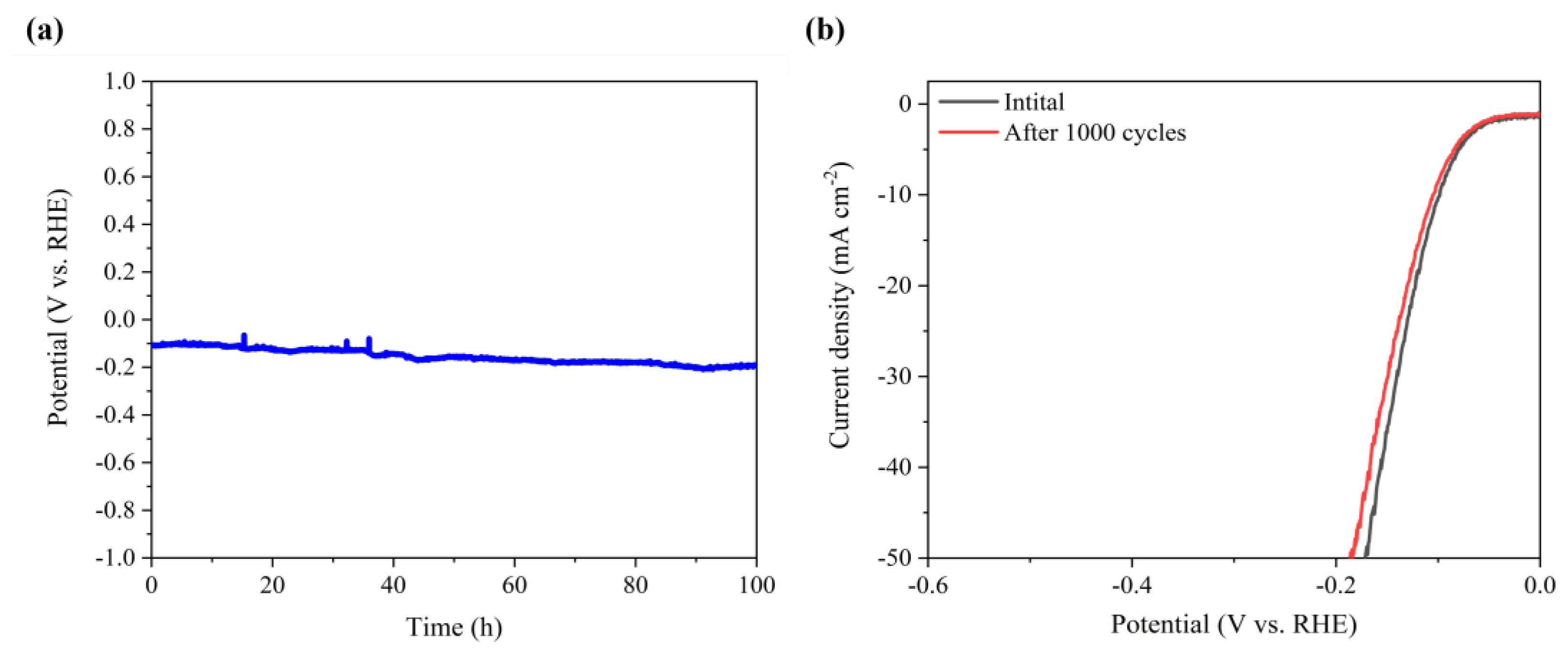

Efficient and low-cost electrocatalysts play a crucial role in hydrogen production through electrolysis of water. Molybdenum (Mo) carbide with a similar electronic structure to Pt was selected, both α-MoC1−x and α-MoC1−x/β-Mo2C electrocatalysts were successfully fabricated for electrochemical hydrogen evolution. A continuous optimization of the hydrothermal and carbonization conditions was carried out for the preparation of α-MoC1−x. The biphasic molybdenum carbide catalysts were further achieved via vanadium doping with a phase transition of molybdenum carbide from α to β, which increases the specific surface area of the electrocatalyst. It was found that the V-MoxC catalyst obtained at a Mo/V molar ratio of 100:5 exhibited the best hydrogen production performance, with a β to α phase ratio of 0.827. The overpotential of V-MoxC at η10 decreased to 99 mV, and the Tafel slope reached 65.1 mV dec−1, indicating a significant improvement in performance compared to undoped samples. Excellent stability was obtained of the as-prepared electrocatalyst for water splitting over 100 h at a current density of 10 mA cm−2.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

| Catalysts | η10/mV | Tafel slope/mV dec−1 | Ref. |

| V-MoxC | 99 | 65.1 | This work |

| MoC-Mo2C-31.4 HNWs | 120 | 42 | [40] |

| Zn-MoC/Mo2C-0.2 | 139 | 49.8 | [41] |

| MoC-Mo2C | 126 | 50 | [42] |

| MoC-Mo2C/PNCDs | 121 | 60 | [43] |

| MoC/Mo2C (II) | 112 | 69 | [44] |

| Ni-MoxC/NC-100 | 162 | 104.8 | [45] |

| Fe-MoC/β-Mo2C@NC | 143 | 73 | [46] |

| Ni15-Mo2C/N | 105 | 44.9 | [47] |

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials and Chemicals

3.2. Synthesis of molybdenum carbide (α-MoC1−x) Samples and Vanadium Doped MoxC (V-MoxC) Samples

3.3. Materials characterization

3.4. Electrochemical measurements

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jin, J.; Wang, X.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, H.; Yin, J.; Xi, P. Precisely Control Relationship between Sulfur Vacancy and H Absorption for Boosting Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Nano-Micro Letters 2024, 16, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, M.Z.; Zahid, R.; Khan, M.W.; Shaheen, M.; Aziz, U.; Aftab, S. Exploration of catalytically active materials for efficient electrochemical hydrogen and oxygen evolution reactions. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 8045–8070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, J.T.; Petersen, A.S.; Østergaard, F.C.; Wood, M.A.; Heffernan, S.M.J.; Milliron, D.J.; Rossmeisl, J.; Resasco, J. Understanding Cation Effects on the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. ACS Energy Letters 2023, 8, 657–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Ouyang, T.; Zou, Y.; Li, N.; Liu, Z.Q. Ultrathin NiCo2Px nanosheets strongly coupled with CNTs as efficient and robust electrocatalysts for overall water splitting. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, Q.; Cheng, L.; Liu, C.; Zhang, M.; Feng, Q.; Ye, H.; Zeng, M.; Xie, L.; Liu, Z.; Li, Y. Ultrathin MoS2(1–x)Se2x Alloy Nanoflakes For Electrocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. ACS Catalysis 2015, 5, 2213–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Chen, Y.; Ren, Z.; Fu, H.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, J.; Tian, G. Self-Supported NiS Nanoparticle-Coupled Ni2P Nanoflake Array Architecture: An Advanced Catalyst for Electrochemical Hydrogen Evolution. ChemElectroChem 2017, 4, 1341–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhou, X.; Tang, J.; Tanaka, S.; Kaneti, Y.V.; Na, J.; Jiang, B.; Yamauchi, Y.; Bando, Y.; Sugahara, Y. Multiscale structural optimization: Highly efficient hollow iron-doped metal sulfide heterostructures as bifunctional electrocatalysts for water splitting. Nano Energy 2020, 75, 104913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, H.T.; Lam, N.D.; Linh, D.C.; Mai, N.T.; Chang, H.; Han, S.-H.; Oanh, V.T.K.; Pham, A.T.; Patil, S.A.; Tung, N.T.; Shrestha, N.K. Escalating Catalytic Activity for Hydrogen Evolution Reaction on MoSe2@Graphene Functionalization. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Yao, S.; Gao, R.; Liang, X.; Yu, Q.; Deng, Y.; Liu, J.; Peng, M.; Jiang, Z.; Li, S.; Li, Y.-W.; Wen, X.-D.; Zhou, W.; Ma, D. A highly CO-tolerant atomically dispersed Pt catalyst for chemoselective hydrogenation. Nature Nanotechnology 2019, 14, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Ma, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, C.; Qin, Y.; Fang, Y.; Guan, G.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, T. Influence of Transition Metal on the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction over Nano-Molybdenum-Carbide Catalyst. Catalysts 2018, 8, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Ruan, Z.; Xu, J.; Yan, J.; Ma, J.; Ma, H.; Qi, J.; Zhu, S.; Lu, L. Regulating surface wettability and electronic state of molybdenum carbide for improved hydrogen evolution reaction. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 17478–17488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, K.; Guo, J.; Xuan, C.; Huang, T.; Deng, Z.; Chen, L.; Wang, D. Ultrafine molybdenum carbide nanoparticles supported on nitrogen doped carbon nanosheets for hydrogen evolution reaction. Chinese Chemical Letters 2019, 30, 192–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchin, J.R.; Nørskov, J.K.; Barteau, M.A.; Chen, J.G. Trends in the chemical properties of early transition metal carbide surfaces: A density functional study. Catalysis Today 2005, 105, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Su, S.; Tian, Y.; Li, Y.; Yu, X.; Sun, P.; Zheng, J.Y. Template-assisted preparation of imbricate N–MoxC nanotubes for the effective electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution reaction. CrystEngComm 2023, 25, 1648–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Shi, W.; Wei, J.; Liu, T.; Li, Y.; He, M.; Wei, Z.; Ping, D.; Sun, P.; Zheng, J.Y.; Li, S. Green fabrication of ultrafine N-MoxC/CoP hybrids for boosting electrocatalytic water reduction. Nanotechnology 2024, 35, 065704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politi, J.R.d.S.; Viñes, F.; Rodriguez, J.A.; Illas, F. Atomic and electronic structure of molybdenum carbide phases: bulk and low Miller-index surfaces. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2013, 15, 12617–12625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Zhang, W.; Shi, Z.; Yang, L.; Tang, Y. Structural Design and Electronic Modulation of Transition-Metal-Carbide Electrocatalysts toward Efficient Hydrogen Evolution. Advanced Materials 2019, 31, 1802880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, S.T.; Milina, M.; Alba-Rubio, A.C.; Hendon, C.H.; Dumesic, J.A.; Román-Leshkov, Y. Self-assembly of noble metal monolayers on transition metal carbide nanoparticle catalysts. Science 2016, 352, 974–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrubel, H.; Hu, X. Molybdenum Boride and Carbide Catalyze Hydrogen Evolution in both Acidic and Basic Solutions. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2012, 51, 12703–12706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Regmi, Y.N.; Leonard, B.M. Multiple Phases of Molybdenum Carbide as Electrocatalysts for the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Angewandte Chemie 2014, 126, 6525–6528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Q.; Wang, Y.; Hu, Q.; Zhou, J.; Feng, R.; Duchesne, P.N.; Zhang, P.; Chen, F.; Han, N.; Li, Y.; Jin, C.; Li, Y.; Lee, S.-T. Ultrasmall and phase-pure W2C nanoparticles for efficient electrocatalytic and photoelectrochemical hydrogen evolution. Nature Communications 2016, 7, 13216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, F.; Gao, Y.; Lang, Z.; Ma, Y.; Yin, L.; Du, J.; Tan, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y. Electrocatalytic performance of ultrasmall Mo2C affected by different transition metal dopants in hydrogen evolution reaction. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 6080–6087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.; Jia, Y.; An, J.; Ge, J.; Wang, M. Simple and Controllable Preparation of Molybdenum Carbides by One-Step Co-Electrolysis of Na2MoO4 and CO2. Journal of The Electrochemical Society. 2023, 170, 053503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Guo, T.; Wu, Z.; Wang, D. Boron triggers the phase transformation of MoxC (α-MoC1−x/β-Mo2C) for enhanced hydrogen production. Nanotechnology 2020, 31, 105707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, D.S.; Jung, G.Y.; Seo, B.; Kim, J.C.; Lee, H.-W.; Shin, T.J.; Jeong, H.Y.; Kwak, S.K.; Joo, S.H. Ordered Mesoporous Metastable α-MoC1−x with Enhanced Water Dissociation Capability for Boosting Alkaline Hydrogen Evolution Activity. Advanced Functional Materials 2019, 29, 1901217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Jia, B.; Fan, Y.; Zhu, K.; Li, G.; Su, C.-Y. Bimetallic Zeolitic Imidazolite Framework Derived Carbon Nanotubes Embedded with Co Nanoparticles for Efficient Bifunctional Oxygen Electrocatalyst. Advanced Energy Materials 2018, 8, 1702048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweitzer, N.M.; Schaidle, J.A.; Ezekoye, O.K.; Pan, X.; Linic, S.; Thompson, L.T. High Activity Carbide Supported Catalysts for Water Gas Shift. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2011, 133, 2378–2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, W.; Liu, W.; Yin, H.; Wang, D. Advanced and Durable Self-Standing MoC-Mo2C Electrode for Alkaline Hydrogen Evolution in Chlor-alkali Electrolysis. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2023, 11, 9470–9477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Hu, J.; Xu, H.; Bian, W.; Ge, J.; Zang, D.; Cheng, D.; Lv, Y.; Zhang, C.; Gu, J.; Wei, Y. Fine Tuning Electronic Structure of Catalysts through Atomic Engineering for Enhanced Hydrogen Evolution. Advanced Energy Materials 2018, 8, 1800789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, D.; Gao, X.J.; Li, L.; Wei, Y.; Wang, H. Confined interface engineering of self-supported Cu@N-doped graphene for electrocatalytic CO2 reduction with enhanced selectivity towards ethanol. Nano Research 2022, 15, 8872–8879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Jia, H.; Fei, B.; Ha, Y.; Li, H.; Guo, Y.; Liu, M.; Wu, R. Charge Transfer Engineering via Multiple Heteroatom Doping in Dual Carbon-Coupled Cobalt Phosphides for Highly Efficient Overall Water Splitting. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2020, 268, 118404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Jia, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, G. Multiphase Molybdenum Carbide Doped Carbon Hollow Sphere Engineering: The Superiority of Unique Double-Shell Structure in Microwave Absorption. Small 2023, 19, 2206323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.-Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, W.-J.; Zhang, X.; Dai, Z.; Wan, L.-J.; Hu, J.-S. Pomegranate-like N,P-Doped Mo2C@C Nanospheres as Highly Active Electrocatalysts for Alkaline Hydrogen Evolution. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 8851–8860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.F.; Yu, L.; Zhang, J.; Lou, X.W.D. Ultrafine Dual-Phased Carbide Nanocrystals Confined in Porous Nitrogen-Doped Carbon Dodecahedrons for Efficient Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Adv Mater. 2019, 31, e1900699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; Cheng, N.; Liu, Q.; Ge, C.; Asiri, A.M.; Sun, X. Mo2C Nanoparticles Decorated Graphitic Carbon Sheets: Biopolymer-Derived Solid-State Synthesis and Application as an Efficient Electrocatalyst for Hydrogen Generation. ACS Catalysis 2014, 4, 2658–2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, X.; Bao, S.; Zhang, Z.; Fei, H.; Wu, Z. Phase engineering of a multiphasic 1T/2H MoS2 catalyst for highly efficient hydrogen evolution. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2017, 5, 2681–2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Wang, J.; Xie, R.; Tian, Z.; Chai, G.; Zhang, Y.; Lai, F.; He, G.; Liu, C.; Liu, T.; Shearing, P.R.; Brett, D.J.L. A universal pH range and a highly efficient Mo2C-based electrocatalyst for the hydrogen evolution reaction. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2020, 8, 19879–19886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Yan, L.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, X.; Wang, Y.; Shen, J.; Zhao, X.; Wang, L. Electrochemical Surface Restructuring of Phosphorus-Doped Carbon@MoP Electrocatalysts for Hydrogen Evolution. Nano-Micro Letters 2021, 13, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.-J.; Yang, F.-H.; Mei, J.-C.; Guo, X.; Wang, H.-Y.; He, M.-Y.; Yao, Y.-A.; Zhang, H.-F.; Liu, C.-B. MOF Template-Derived Carbon Shell-Embedded CoP Hierarchical Nanosheet as Bifunctional Catalyst for Overall Water Splitting. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhang, X.; Jin, M.; Xiong, Q.; Wang, G.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, H. Robust enhanced hydrogen production at acidic conditions over molybdenum oxides-stabilized ultrafine palladium electrocatalysts. Nano Research 2021, 14, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Jiang, Y.; Jia, L.; Wang, C. MoO2 nanoparticles on reduced graphene oxide/polyimide-carbon nanotube film as efficient hydrogen evolution electrocatalyst. Journal of Power Sources 2016, 304, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Wang, X.; Sun, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, J. Flawed MoO2 belts transformed from MoO3 on a graphene template for the hydrogen evolution reaction. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 7040–7044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, J.; Yue, X.; Han, Y.; Shen, P.K.; Cui, Y. Porous MoO2 Nanosheets as Non-noble Bifunctional Electrocatalysts for Overall Water Splitting. Advanced Materials 2016, 28, 3785–3790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Wang, P.; Wang, H.; Xu, C.; Zhu, J.; Liang, Y.; Su, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Wu, W.; Fu, E.; Zou, G. Defect engineering of molybdenum disulfide through ion irradiation to boost hydrogen evolution reaction performance. Nano Research 2019, 12, 1613–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, S.; Salman, M.; Ali, S.; Ling, Y.; Khan, M. Electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution reaction on sulfur-deficient MoS2 nanostructures. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 7713–7723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, D.; Ghosal Chowdhury, M.; Biswas, R.; Haldar, K.K.; Patra, A. Europium Molybdate/Molybdenum Disulfide Nanostructures with Efficient Electrocatalytic Activity for the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. ACS Applied Nano Materials 2023, 6, 7218–7228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, C.; Song, H.; Bao, Y.; Lei, X. Carbon-coated molybdenum carbide nanosheets derived from molybdenum disulfide for hydrogen evolution reaction. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 12610–12617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).