Submitted:

09 January 2026

Posted:

13 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

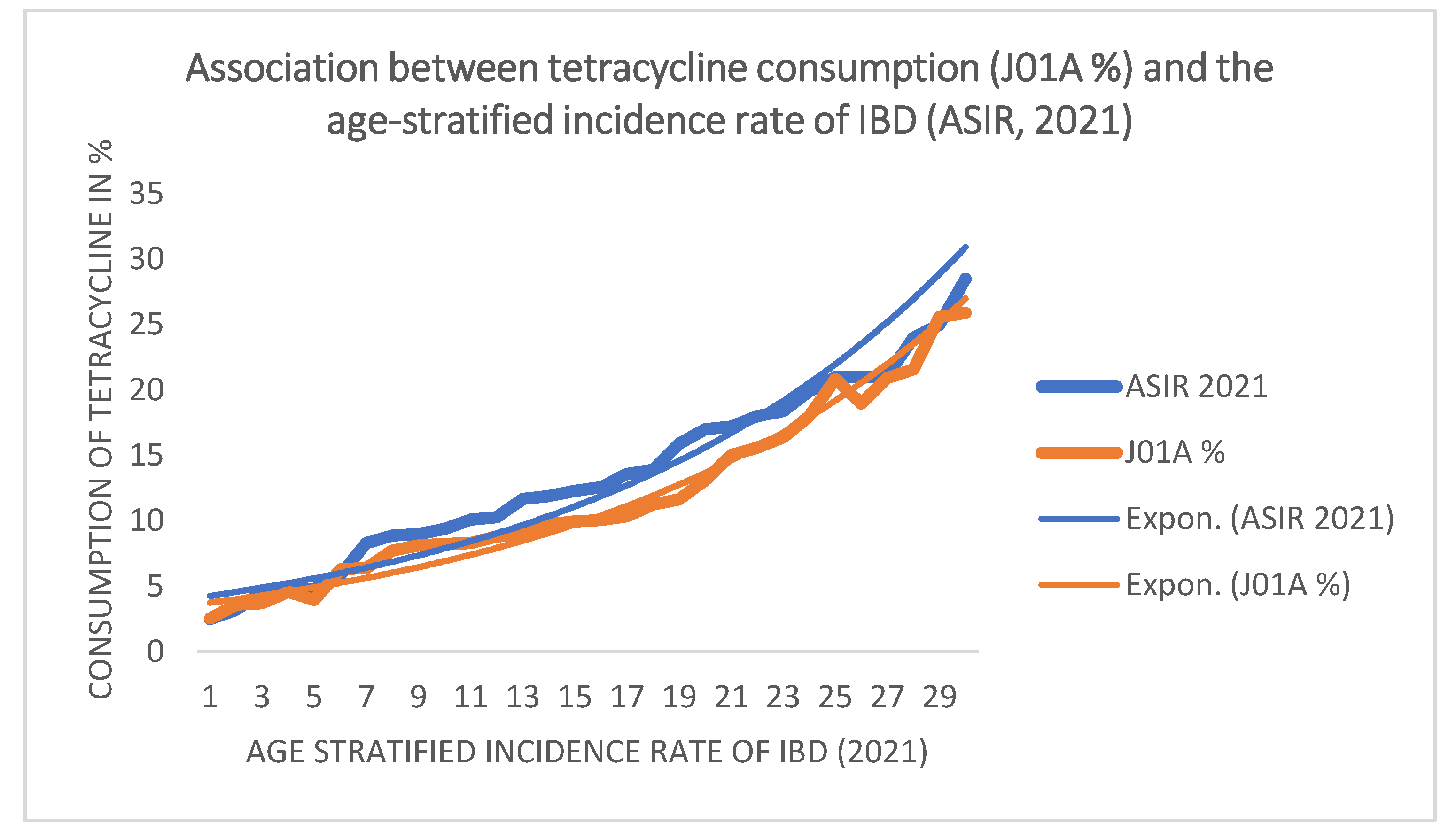

The predominant forms of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis, which occur in approximately 0.5-1% of the World population. Alterations in the microbial flora (dysbiosis) are considered the primary precipitating factor in IBD. Because antibiotics are major disruptors of the microbiome, it was hypothesized that different antibiotic classes might induce distinct alterations in gut flora, reflected in positive or negative associations with IBD incidence at the population level. Average yearly consumption was calculated from ECDC reports (2004-2023) for the major antibiotic classes, which cover 99.87% of total antibiotic consumption across 30 European countries. Data were compared with age-stratified IBD incidence (15–39 years) estimated for 2021. Ordinal logistic regression modeled the association between antibiotic class proportions and IBD-incidence categories, entering each antibiotic class separately as a continuous predictor. Pearson correlation analyses were conducted to assess linear associations, and Kruskal-Wallis tests were applied to compare incidence categories. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Tetracyclines (J01A), narrow-spectrum penicillin (J01CE, J01CF), and sulfonamides (J01E) showed a significant positive association with IBD incidence, indicating that higher consumption was associated with higher national incidence. In contrast, cephalosporins, macrolides, aminoglycosides, and quinolones showed significant negative associations, suggesting links to lower national incidence levels. Different antibiotic consumption patterns across 30 European countries may be associated with the IBD incidence.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Concept/working hypothesis:

3. Objective

4. Materials and methods

5. Results

6. Discussion

Conclusion

References

- Ng, SC; Shi, HY; Hamidi, N; Underwood, FE; et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet 2017, 390(10114), 2769–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, MJ; Dhawan, A; Saeed, SA; et al. Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Children and Adolescents. JAMA Pediatr 2015, 169(11), 1053–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, DT; Ananthakrishnan, AN; Siegel, CA. Clinical Guideline: Ulcerative Colitis in Adults. Am J Gastroenterol 2019, 114(3), 384–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, GR; Loftus, EV; Isaacs, KL; et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Management of Crohn's Disease in Adults. Am J Gastroenterol 2018, 113(4), 481–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDowell, C; Farooq, U; Haseeb, M. Inflammatory Bowel Disease. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 4 Aug 2023; Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470312/.

- Caron, B; Honap, S; Peyrin-Biroulet, L. Epidemiology of Inflammatory Bowel Disease across the Ages in the Era of Advanced Therapies. J Crohns Colitis 2024, 18 Supplement_2, ii3–ii15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruner, LP; White, AM; Proksell, S. Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Prim Care Epub. 2023, 50(3), 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borowitz, SM. The epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: Clues to pathogenesis? Front Pediatr 2023, 10, 1103713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfvarson, J; Ludvigsson, JF; Bresso, F; et al. Age determines the risk of familiar inflammatory bowel disease – a nationwide study. Alim Pharmacol Ther. 2022, 56, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfvarson, J. Genetic epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease, early twin and family studies. In Molecular genetics of inflammatory bowel disease, 2nd ed.; Hedin, C, Rioux, JD, M D’Amato, Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2019; pp. 25–46. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, M; Sabino, J; Frias-Gomes, C; et al. Early life exposures and the risk of inflammatory bowel disease: Systematic review and meta-analyses. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 36, 100884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D; Jin, Y; Shao, X; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of inflammatory bowel disease, 1990-2021: Insights from the global burden of disease 2021. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2024, 39(1), 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L; Xu, Y; Ai, F; et al. Dissecting the rising tide of inflammatory bowel disease among youth in a changing world: insights from GBD 2021. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2025, 40(1), 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swidsinski, A; Ladhoff, A; Pernthaler, A; et al. Mucosal flora in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2002, 122(1), 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, CE; Renz, H; Jenmalm, MC. in-FLAME Microbiome Interest Group. The gut microbiota and inflammatory noncommunicable diseases: associations and potentials for gut microbiota therapies. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015, 135(1), 3–13; quiz 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavelle, A; Sokol, H. Gut microbiota-derived metabolites as key actors in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020, 17(4), 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jandhyala, SM; Talukdar, R; Subramanyam, C; et al. Role of the normal gut microbiota. World J Gastroenterol 2015, 21(29), 8787–8803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, MM; Wangchuk, P; Sarker, S. A systematic review on the role of gut microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease: Spotlight on virome and plant metabolites. Microb Pathog 2025, 205, 107608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalal, SR. The Microbiome and Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Surg Clin North Am 2025, 105(5), 941–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliev, ID; Ananthakrishnan, AN; Guo, CJ. Microbiota in inflammatory bowel disease: mechanisms of disease and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Microbiol 2025, 23(8), 509–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, RH; Dulai, PS; Vázquez-Baeza, Y. Multi-omics analyses of the ulcerative colitis gut microbiome link Bacteroides vulgatus proteases with disease severity. Nat Microbiol 2022, 7(2), 262–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foppa, C; Rizkala, T; Repici, A; et al. Microbiota and IBD: Current knowledge and future perspectives. Dig Liver Dis. 2024, 56(6), 911–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, M; Allin, KH; Petralia, F; et al. Multiomics to elucidate inflammatory bowel disease risk factors and pathways. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022, 19(6), 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadegar, A; Bar-Yoseph, H; Monaghan, TM; et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation: current challenges and future landscapes. Clin Microbiol Rev.;Epub 2024, 37(2), e0006022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Paramsothy, S; Kamm, MA; Kaakoush, NO; et al. Multidonor intensive faecal microbiota transplantation for active ulcerative colitis: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2017, 389, 1218–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fehily, SR; Wright, EK; Basnayake, C; et al. Faecal microbiota transplantation in Crohn's disease: an Australian randomised placebo-controlled trial protocol. BMJ Open 2025, 15(4), e094714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahoud, C; Habib, T; Kalta, D; et al. Intestinal Microbiota and Fecal Transplantation in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Clostridioides difficile: An Updated Literature Review. J Clin Med. 2025, 14(15), 5260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koido, S; Ohkusa, T; Kajiura, T; et al. Long-term alteration of intestinal microbiota in patients with ulcerative colitis by antibiotic combination therapy. PLoS One 2014, 9, e86702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faye, AS; Allin, KH; Iversen, AT; et al. Antibiotic use as a risk factor for inflammatory bowel disease across the ages: a population-based cohort study. Gut 2023, 72(4), 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, R; Zhang, C; Li, G; et al. Antibiotic Exposure and Risk of New-Onset Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol;Epub 2025, 23(1), 45–58.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boppana, K; Almansouri, NE; Bakkannavar, S; et al. Alterations in Gut Microbiota as Early Biomarkers for Predicting Inflammatory Bowel Disease Onset and Progression: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2024, 16(4), e58080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San-Martin, MI; Chamizo-Ampudia, A; Sanchiz, Á; et al. Microbiome Markers in Gastrointestinal Disorders: Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Colorectal Cancer, and Celiac Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26(10), 4818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Average, yearly antibiotic consumption (2004-2023, 20 years) expressed in defined daily dose/1000 inhabitants/day (did) in 30 European countries. | IBD incidence | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Countries | J01 | J1A % | J01C% | J01CA% | J01CE% | J01CF% | J01CR% | J01D% | J01E% | J01F% | J01G% | J01M% | J01X% | ASIR 2021 |

| Austria | 10.193 | 3.726 | 47.435 | 8.219 | 4.060 | 0.704 | 34.880 | 15.933 | 2.519 | 18.670 | 0.245 | 7.291 | 4.209 | 13.600 |

| Belgium | 22.537 | 8.829 | 45.889 | 19.787 | 0.442 | 1.599 | 24.086 | 8.575 | 1.169 | 14.330 | 0.208 | 10.307 | 11.520 | 12.300 |

| Bulgaria | 20.213 | 10.362 | 29.583 | 17.131 | 1.446 | 0.002 | 10.877 | 21.720 | 4.276 | 19.338 | 1.500 | 14.033 | 0.548 | 9.000 |

| Croatia | 19.808 | 6.391 | 41.336 | 11.226 | 5.069 | 0.558 | 24.391 | 17.831 | 4.338 | 15.972 | 0.517 | 8.289 | 5.700 | 9.400 |

| Cyprus | 26.500 | 11.637 | 35.256 | 10.078 | 0.339 | 0.154 | 25.226 | 21.249 | 1.060 | 11.368 | 0.367 | 17.340 | 2.358 | 11.900 |

| Czech Rep. | 15.627 | 11.237 | 35.439 | 4.541 | 8.542 | 0.828 | 21.537 | 14.952 | 5.414 | 20.147 | 0.433 | 3.742 | 7.362 | 24.000 |

| Denmark | 16.540 | 9.734 | 61.570 | 20.188 | 27.733 | 9.239 | 4.432 | 1.877 | 4.916 | 12.079 | 0.316 | 3.534 | 4.794 | 19.900 |

| Estonia | 11.716 | 15.600 | 32.813 | 16.051 | 2.062 | 1.489 | 13.699 | 12.355 | 4.429 | 19.962 | 0.684 | 8.246 | 5.605 | 4.600 |

| Finland | 17.484 | 21.589 | 28.447 | 15.068 | 7.685 | 0.850 | 4.848 | 16.004 | 7.263 | 7.443 | 0.095 | 5.646 | 12.290 | 18.400 |

| France | 24.836 | 13.069 | 49.806 | 28.256 | 0.678 | 1.251 | 19.963 | 9.563 | 1.964 | 14.346 | 0.376 | 7.697 | 2.935 | 13.900 |

| Germany | 12.928 | 16.406 | 34.990 | 18.489 | 5.271 | 0.427 | 10.796 | 17.491 | 4.932 | 15.880 | 0.204 | 5.966 | 4.118 | 25.000 |

| Greece | 32.505 | 7.737 | 28.884 | 12.497 | 1.335 | 0.038 | 15.007 | 23.814 | 1.198 | 25.229 | 1.716 | 8.448 | 2.946 | 4.800 |

| Hungary | 14.754 | 8.964 | 33.696 | 8.003 | 2.890 | 0.004 | 24.380 | 14.905 | 4.175 | 21.737 | 0.406 | 14.421 | 1.978 | 18.000 |

| Iceland | 19.202 | 25.577 | 47.629 | 18.816 | 10.831 | 6.115 | 11.867 | 4.022 | 4.591 | 7.617 | 0.371 | 4.035 | 5.796 | 21.000 |

| Ireland | 20.689 | 15.021 | 45.876 | 15.274 | 4.588 | 6.562 | 19.369 | 7.118 | 4.979 | 18.766 | 0.398 | 4.016 | 3.094 | 17.000 |

| Italy | 22.860 | 2.550 | 43.891 | 11.437 | 0.009 | 0.086 | 31.530 | 11.536 | 3.014 | 20.022 | 0.474 | 13.645 | 3.943 | 8.300 |

| Latvia | 13.162 | 18.965 | 36.168 | 22.988 | 0.808 | 0.449 | 12.083 | 9.310 | 5.799 | T12.710 | 1.426 | 8.972 | 6.434 | 4.800 |

| Lithuania | 16.412 | 9.961 | 46.183 | 29.731 | 5.427 | 0.478 | 11.259 | 10.986 | 2.348 | 11.881 | 1.255 | 6.555 | 10.531 | 5.900 |

| Luxembourg | 22.502 | 8.312 | 38.870 | 13.111 | 0.305 | 0.884 | 24.022 | 17.585 | 1.659 | 16.466 | 0.277 | 11.190 | 6.398 | 15.900 |

| Malta | 19.815 | 8.114 | 36.043 | 3.125 | 0.627 | 0.884 | 31.406 | 20.561 | 1.674 | 19.062 | 1.272 | 11.324 | 4.117 | 10.100 |

| Netherlands | 9.917 | 20.846 | 32.962 | 13.176 | 2.572 | 5.652 | 11.919 | 2.394 | 4.988 | 14.822 | 0.635 | 7.894 | 14.764 | 28.500 |

| Norway | 16.195 | 17.996 | 40.831 | 13.521 | 22.184 | 4.662 | 0.493 | 2.307 | 4.909 | 9.318 | 0.469 | 2.940 | 21.368 | 21.000 |

| Poland | 22.225 | 10.058 | 29.536 | 15.044 | 1.361 | 0.150 | 12.981 | 14.387 | 2.441 | 18.011 | 0.304 | 6.548 | 15.427 | 3.200 |

| Portugal | 19.290 | 4.563 | 45.254 | 10.305 | 0.558 | 2.824 | 30.814 | 12.061 | 2.625 | 15.865 | 0.353 | 10.093 | 6.421 | 10.300 |

| Romania | 25.095 | 3.963 | 45.695 | 15.954 | 2.534 | 2.172 | 25.031 | 18.764 | 3.176 | 13.387 | 1.088 | 12.848 | 0.823 | 2.500 |

| Slovakia | 20.805 | 8.237 | 32.417 | 6.135 | 7.974 | 0.029 | 18.451 | 21.932 | 2.685 | 25.282 | 0.402 | 9.481 | 0.998 | 8.900 |

| Slovenia | 13.354 | 3.610 | 54.967 | 16.239 | 13.072 | 2.023 | 23.632 | 5.836 | 6.903 | 16.126 | 0.486 | 9.484 | 2.935 | 12.600 |

| Spain | 24.050 | 6.311 | 54.587 | 22.790 | 0.445 | 1.005 | 30.343 | 11.100 | 1.925 | 11.966 | 0.314 | 10.477 | 2.937 | 11.700 |

| Sweden | 14.052 | 20.911 | 48.537 | 8.712 | 25.907 | 12.013 | 1.941 | 2.790 | 3.679 | 5.000 | 0.163 | 6.356 | 12.449 | 21.100 |

| UK | 41.961 | 25.900 | 38.492 | 18.626 | 4.601 | 9.435 | 5.828 | 2.067 | 7.099 | 13.570 | 0.586 | 2.822 | 6.401 | 17.200 |

| Pearson's r | 0.519 | 0.112 | -0.144 | 0.465 | 0.503 | -0.334 | -0.478 | 0.424 | -0.337 | -0.524 | -0.452 | 0.310 | ||

| Pearson's p-value | 0.003 | 0.554 | 0.447 | 0.010 | 0.005 | 0.071 | 0.008 | 0.020 | 0.068 | 0.003 | 0.012 | 0.095 | ||

| Odds ratio | 1.215 | 1.041 | 0.966 | 1.223 | 1.715 | 0.934 | 0.843 | 1.555 | 0.795 | 0.041 | 0.772 | 1.165 | ||

| 95%CI | 1.074-1.412 | 0.961-1.131 | 0.869-1.071 | 1.065-1.513 | 1.234-2.779 | 0.864-1.003 | 0.742-0.943 | 1.062-2.399 | 0.652-0.936 | 0.002-0.314 | 0.609-0.944 | 0.998-1.407 | ||

| p value | 0.005 | 0.331 | 0.510 | 0.023 | 0.007 | 0.068 | 0.005 | 0.031 | 0.011 | 0.008 | 0.019 | 0.072 | ||

| Kruskal-Wallis p | 0.003 | 0.048 | 0.924 | 0.002 | 0.014 | 0.001 | 0.030 | 0.004 | 0.114 | 0.010 | 0.006 | 0.096 | ||

| Post-Hoc test | G1 vs G2 | 0.893 | 0.041 | 0.893 | 0.322 | 0.034 | 0.050 | 0.285 | 0.251 | 0.404 | 0.022 | 0.893 | 0.997 | |

| G1 vs G3 | 0.018 | 0.636 | 0.972 | 0.011 | 0.041 | 0.041 | 0.060 | 0.018 | 0.165 | 0.027 | 0.011 | 0.220 | ||

| G2 vs G3 | 0.006 | 0.285 | 0.988 | 0.009 | 0.636 | 0.003 | 0.165 | 0.018 | 0.404 | 0.988 | 0.027 | 0.103 | ||

| Countries | ASIR 2021 | Countries | J01A % | Countries | J01CE% | Countries | J01E% | Countries | J01D% | Countries | J01F% | Countries | J01M% |

| Netherlands | 28,5 | UK | 25,900 | Denmark | 27,733 | Finland | 7,263 | Greece | 23,814 | Slovakia | 25,282 | Cyprus | 17,340 |

| Germany | 25 | Iceland | 25,577 | Sweden | 25,907 | UK | 7,099 | Slovakia | 21,932 | Greece | 25,229 | Hungary | 14,421 |

| Czechia | 24 | Finland | 21,589 | Norway | 22,184 | Slovenia | 6,903 | Bulgaria | 21,720 | Hungary | 21,737 | Bulgaria | 14,033 |

| Sweden | 21,1 | Sweden | 20,911 | Slovenia | 13,072 | Latvia | 5,799 | Cyprus | 21,249 | Czechia | 20,147 | Italy | 13,645 |

| Iceland | 21 | Netherlands | 20,846 | Iceland | 10,831 | Czechia | 5,414 | Malta | 20,561 | Italy | 20,022 | Romania | 12,848 |

| Norway | 21 | Latvia | 18,965 | Czechia | 8,542 | Netherlands | 4,988 | Romania | 18,764 | Estonia | 19,962 | Malta | 11,324 |

| Denmark | 19,9 | Norway | 17,996 | Slovakia | 7,974 | Ireland | 4,979 | Croatia | 17,831 | Bulgaria | 19,338 | Luxembourg | 11,190 |

| Finland | 18,4 | Germany | 16,406 | Finland | 7,685 | Germany | 4,932 | Luxembourg | 17,585 | Malta | 19,062 | Spain | 10,477 |

| Hungary | 18 | Estonia | 15,600 | Lithuania | 5,427 | Denmark | 4,916 | Germany | 17,491 | Ireland | 18,766 | Belgium | 10,307 |

| UK | 17,2 | Ireland | 15,021 | Germany | 5,271 | Norway | 4,909 | Finland | 16,004 | Austria | 18,670 | Portugal | 10,093 |

| Ireland | 17 | France | 13,069 | Croatia | 5,069 | Iceland | 4,591 | Austria | 15,933 | Poland | 18,011 | Slovenia | 9,484 |

| Luxembourg | 15,9 | Cyprus | 11,637 | UK | 4,601 | Estonia | 4,429 | Czechia | 14,952 | Luxembourg | 16,466 | Slovakia | 9,481 |

| France | 13,9 | Czechia | 11,237 | Ireland | 4,588 | Croatia | 4,338 | Hungary | 14,905 | Slovenia | 16,126 | Latvia | 8,972 |

| Austria | 13,6 | Bulgaria | 10,362 | Austria | 4,060 | Bulgaria | 4,276 | Poland | 14,387 | Croatia | 15,972 | Greece | 8,448 |

| Slovenia | 12,6 | Poland | 10,058 | Hungary | 2,890 | Hungary | 4,175 | Estonia | 12,355 | Germany | 15,880 | Croatia | 8,289 |

| Belgium | 12,3 | Lithuania | 9,961 | Netherlands | 2,572 | Sweden | 3,679 | Portugal | 12,061 | Portugal | 15,865 | Estonia | 8,246 |

| Cyprus | 11,9 | Denmark | 9,734 | Romania | 2,534 | Romania | 3,176 | Italy | 11,536 | Netherlands | 14,822 | Netherlands | 7,894 |

| Spain | 11,7 | Hungary | 8,964 | Estonia | 2,062 | Italy | 3,014 | Spain | 11,100 | France | 14,346 | France | 7,697 |

| Portugal | 10,3 | Belgium | 8,829 | Bulgaria | 1,446 | Slovakia | 2,685 | Lithuania | 10,986 | Belgium | 14,330 | Austria | 7,291 |

| Malta | 10,1 | Luxembourg | 8,312 | Poland | 1,361 | Portugal | 2,625 | France | 9,563 | UK | 13,570 | Lithuania | 6,555 |

| Croatia | 9,4 | Slovakia | 8,237 | Greece | 1,335 | Austria | 2,519 | Latvia | 9,310 | Romania | 13,387 | Poland | 6,548 |

| Bulgaria | 9 | Malta | 8,114 | Latvia | 0,808 | Poland | 2,441 | Belgium | 8,575 | Latvia | 12,710 | Sweden | 6,356 |

| Slovakia | 8,9 | Greece | 7,737 | France | 0,678 | Lithuania | 2,348 | Ireland | 7,118 | Denmark | 12,079 | Germany | 5,966 |

| Italy | 8,3 | Croatia | 6,391 | Malta | 0,627 | France | 1,964 | Slovenia | 5,836 | Spain | 11,966 | Finland | 5,646 |

| Lithuania | 5,9 | Spain | 6,311 | Portugal | 0,558 | Spain | 1,925 | Iceland | 4,022 | Lithuania | 11,881 | Iceland | 4,035 |

| Greece | 4,8 | Portugal | 4,563 | Spain | 0,445 | Malta | 1,674 | Sweden | 2,790 | Cyprus | 11,368 | Ireland | 4,016 |

| Latvia | 4,8 | Romania | 3,963 | Belgium | 0,442 | Luxembourg | 1,659 | Netherlands | 2,394 | Norway | 9,318 | Czechia | 3,742 |

| Estonia | 4,6 | Austria | 3,726 | Cyprus | 0,339 | Greece | 1,198 | Norway | 2,307 | Iceland | 7,617 | Denmark | 3,534 |

| Poland | 3,2 | Slovenia | 3,610 | Luxembourg | 0,305 | Belgium | 1,169 | UK | 2,067 | Finland | 7,443 | Norway | 2,940 |

| Romania | 2,5 | Italy | 2,550 | Italy | 0,009 | Cyprus | 1,060 | Denmark | 1,877 | Sweden | 5,000 | UK | 2,822 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).