Submitted:

12 January 2026

Posted:

13 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

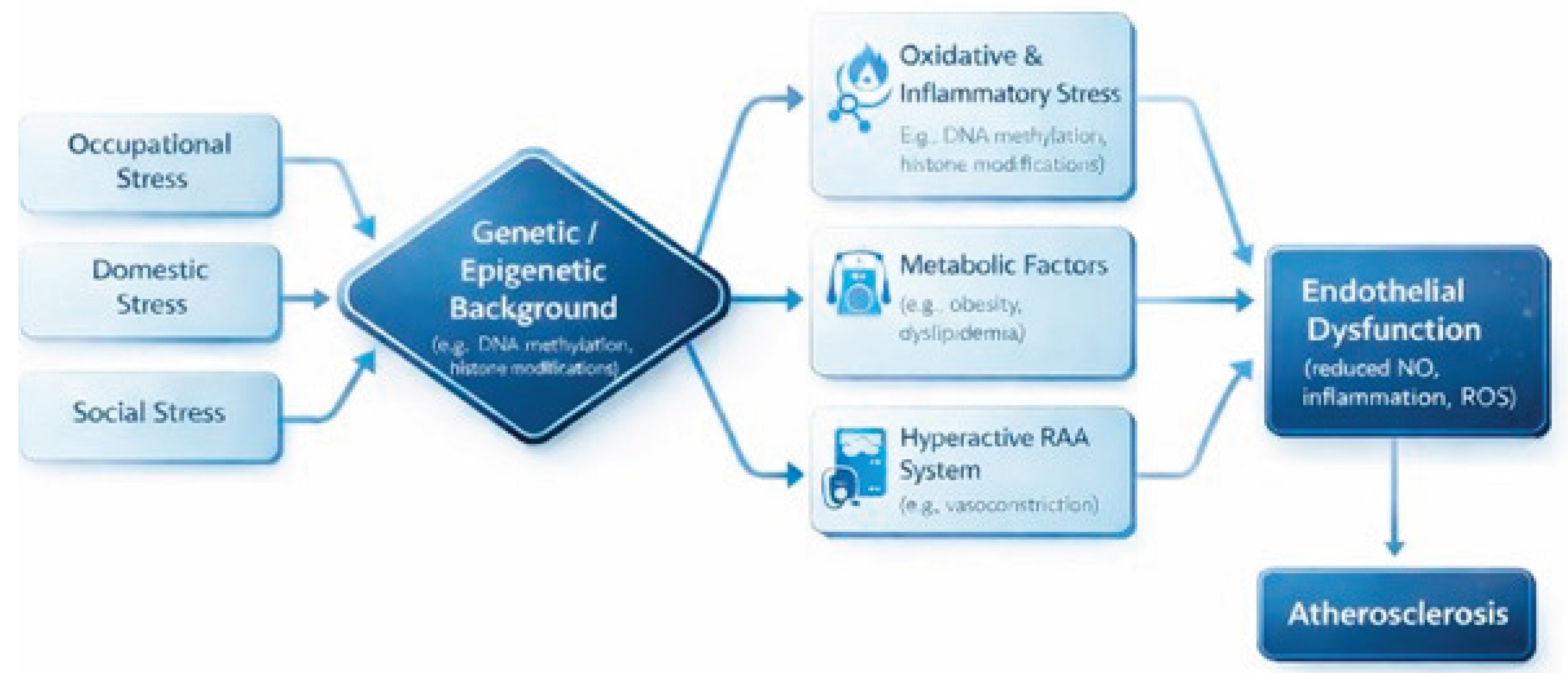

Cardiovascular diseases, particularly atherosclerotic coronary artery disease (CAD), remain among the leading causes of mortality worldwide. Although traditional risk factors—such as arterial hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, obesity, smoking, and physical inactivity—are well established, accumulating evidence highlights the significant role of psychosocial factors in modulating cardiovascular risk. Among these, occupational stress—conceptualized through models such as job strain (high job demands combined with low control) and effort–reward imbalance—has been consistently associated with an increased risk of coronary events. The interaction between occupational stress and classical cardiovascular risk factors remains insufficiently elucidated and challenging to quantify. This review examines the current scientific evidence regarding the relationship between occupational stress and CAD, synthesizing findings from major epidemiological studies and relevant meta-analyses. Chronic exposure to work-related stress activates neuroendocrine pathways, including the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and the sympathetic nervous system, promotes a state of low-grade systemic inflammation, and facilitates the adoption of unhealthy behaviors such as smoking, poor dietary habits, physical inactivity, and excessive alcohol consumption. These mechanisms contribute to endothelial dysfunction, hypercoagulability, and acceleration of the atherosclerotic process. Landmark investigations, including the INTERHEART study, meta-analyses conducted by Kivimäki and colleagues, and prospective studies by Chandola on the metabolic syndrome, support both the cumulative and independent impact of occupational stress on cardiovascular risk. Although the proportion of risk attributable to occupational stress is lower than that associated with traditional risk factors, its modifiable nature underscores a substantial potential for targeted preventive interventions. Strategies aimed at reducing occupational stress encompass individual-level approaches (stress management programs, lifestyle modification, psychological support), organizational interventions (optimizing the balance between job demands and employee control, enhancing social support in the workplace), and public health policies (occupational health promotion programs, regulatory measures addressing work-related stress, and screening for occupational stress). Recognizing occupational stress as a modifiable risk factor for CAD has important implications for both clinical practice and public health. Future research should focus on large-scale longitudinal studies, the identification of stress-related biomarkers, and the cost-effectiveness of stress-reduction interventions in the prevention and management of coronary artery disease.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Traditional Cardiovascular Risk Factors: Setting the Context for Occupational Stress

4. Individual Factors and Susceptibility to Stress

4.1. Genetic Factors

4.2. Psychological Factors

4.3. Socioeconomic Factors

5. Definition and Conceptualization of Socioprofessional Stress

5.1. The Demand–Control Model (Karasek)

5.2. The Effort–Reward Imbalance Model (Siegrist)

5.3. Social Support

6. Pathophysiological Mechanisms Linking Stress to Atherogenesis

6.1. Neuroendocrine Activation and Inflammatory Response

6.2. Interaction with Behavioral Risk Factors

6.3. Endothelial Dysfunction and Hypercoagulability

7. Markers of Chronic Stress and Cardiovascular Risk

7.1. Inflammatory Biomarkers

7.2. Markers of Neuroendocrine Activation

7.3. Epigenetic Biomarkers

7.4. Heart Rate Variability (HRV) Reactivity to Stress

8. Epidemiological and Clinical Evidence

8.1. The Kivimäki et al. Meta-Analysis (2012)

8.2. Chandola et al. (2006) and the Metabolic Syndrome

8.3. The INTERHEART Study (Rosengren et al., 2004)

8.4. The Role of Social Support (Orth-Gomér et al., 1993)

8.5. Netterstrøm et al. (2010)

8.6. Kivimäki et al. (2013)

9. Practical Implications and Intervention Strategies

9.1. Assessment of Psychosocial Risk in Clinical Practice

9.2. Individual-Level Interventions

9.3. Organizational-Level Interventions

9.4. Public Health Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CAD | Coronary artery disease |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| CVD | Cardiovascular disease |

| ERI | Effort–reward imbalance |

| ESC | European Society of Cardiology |

| HF | High-frequency component (of heart rate variability) |

| HPA axis | Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis |

| HRV | Heart rate variability |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| JCQ | Job Content Questionnaire |

| LDL | Low-density lipoprotein |

| LF | Low-frequency component (of heart rate variability) |

| NAFLD | Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease |

| NT-proBNP | N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide |

| RMSSD | Root mean square of successive differences |

| SDNN | Standard deviation of normal-to-normal RR intervals |

| SNS | Sympathetic nervous system |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

References

- Rozanski, A.; Blumenthal, J.A.; Kaplan, J. Impact of psychological factors on the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease and implications for therapy. Circulation 1999, 99(16), 2192–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandola, T.; Brunner, E.; Marmot, M. Chronic stress at work and the metabolic syndrome: Prospective study. BMJ 2006, 332(7540), 521–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosengren, A.; Hawken, S.; Ounpuu, S.; et al. Association of psychosocial risk factors with risk of acute myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): Case-control study. Lancet 2004, 364(9438), 953–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orth-Gomér, K.; Rosengren, A.; Wilhelmsen, L. Lack of social support and incidence of coronary heart disease in middle-aged Swedish men. Psychosom Med. 1993, 55(1), 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Power, N.; Kelly, S; Gallagher, J.; et al. Job strain and the incidence of heart diseases: A prospective community study in Quebec, Canada. J Psychosom Res. 2020, 139, 110268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kivimäki, M.; Singh-Manoux, A.; Nyberg, S.T.; Jokela, M.; Virtanen, M. Job strain and risk of obesity: Systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Int J Obes (Lond) 2015, 39(11), 1597–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kivimäki, M.; Nyberg, S.T.; Batty, G.D.; et al. Job strain as a risk factor for coronary heart disease: A collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet 2012, 380(9852), 1491–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukas, E.; Veeneman, R.R.; Smit, D.J.A.; et al. A genetic exploration of the relationship between posttraumatic stress disorder and cardiovascular diseases. Transl Psychiatry 2025, 15(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lichtman, J.H.; Bigger, J.T., Jr.; Blumenthal, J.A.; Frasure-Smith, N.; Kaufmann, P.G.; Lespérance, F.; et al. Depression and coronary heart disease: Recommendations for screening, referral, and treatment: A science advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2008, 118(17), 1768–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, WM; Kelli, HM; Lisko, JC; Varghese, T; Shen, J; Sandesara, P.; et al. Socioeconomic status and cardiovascular outcomes: Challenges and interventions. Circulation 2018, 137(20), 2166–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karasek, R.A. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. Adm Sci Q. 1979, 24, 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, J. Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. J Occup Health Psychol. 1996, 1(1), 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franklin, T.B.; Saab, B.J.; Mansuy, I.M. Neural mechanisms of stress resilience and vulnerability. Neuron 2012, 75(5), 747–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valaitienė, J.; Laučytė-Cibulskienė, A. Oxidative stress and its biomarkers in cardiovascular diseases. Artery Res. 2024, 30(1), 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.G.; Cheon, E.J.; Bai, D.S.; Lee, Y.H.; Koo, B.H. Stress and heart rate variability: A meta-analysis and review of the literature. Psychiatry Investig. 2018, 15(3), 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visseren, F.L.J.; Mach, F.; Smulders, Y.M.; Carballo, D.; Koskinas, K.C.; Bäck, M.; et al. ESCScientific Document Group 2021 ESCGuidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice Eur Heart, J. 2021, 42(34), 3227–3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEwen, B.S.; Gianaros, P.J. Central role of the brain in stress and adaptation: Links to socioeconomic status, health, and disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010, 1186, 190–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.