Submitted:

09 January 2026

Posted:

13 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemistry

2.1.1. General

2.1.2. Synthesis

2.1.3. HPLC Analysis

2.2. Photophysical Characterization

2.2.1. Enzymatic Activation

2.2.2. Fluorescence Quantum Yield

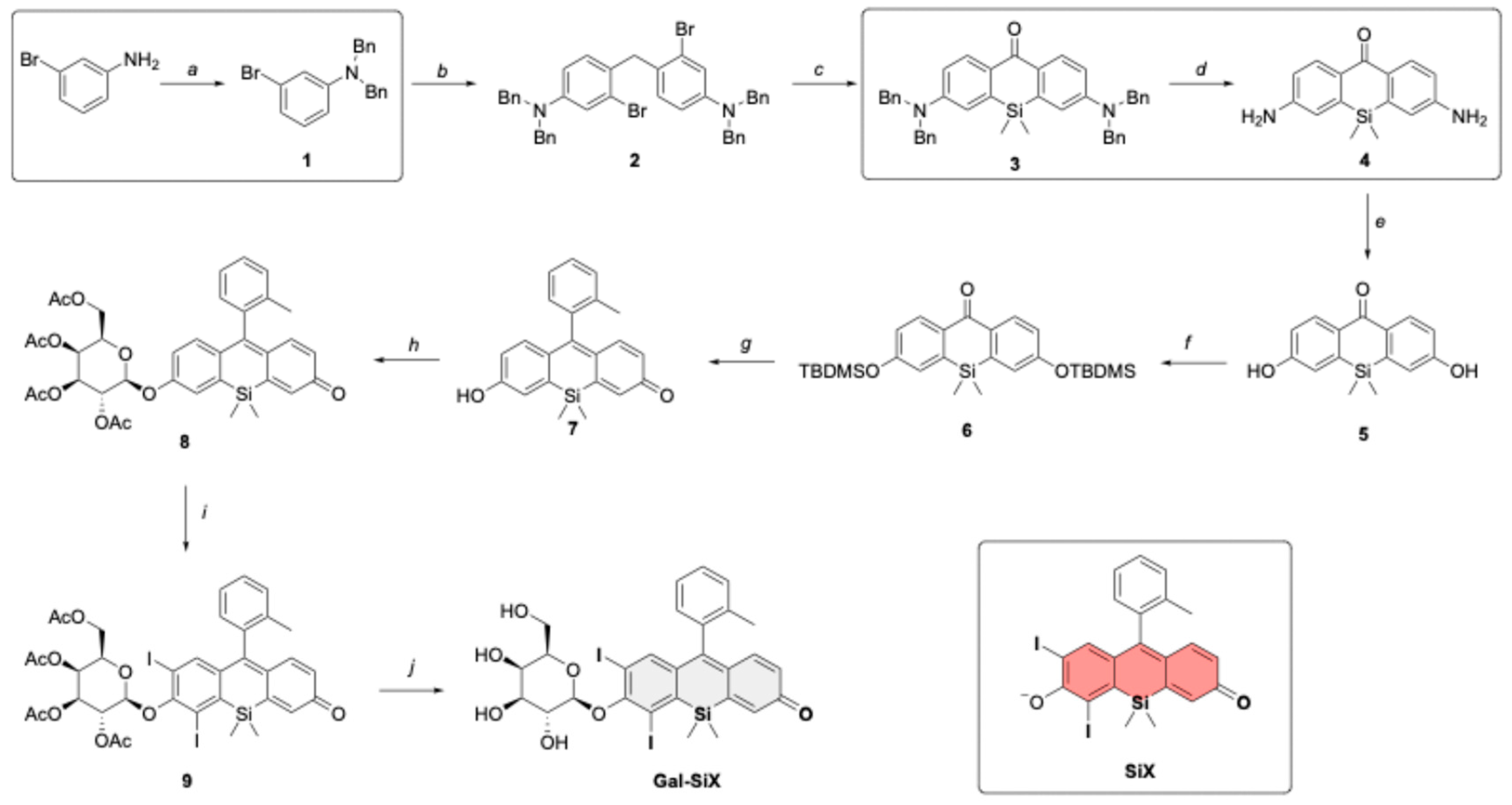

2.2.3. Singlet Oxygen Trap Experiment

2.2.4. General Procedure for Detection of ROS Type

2.2.5. Interference Studies

2.3. In vitro Experiments

2.3.1. Cell Culture

2.3.2. Photodynamic Therapy

2.3.3. Cell Viability Analysis

2.3.4. Cellular Internalization and Activation

2.3.5. Subcellular co-localization experiments

2.3.6. Scavenger assays

2.3.7. Intracellular Type I ROS Detection

2.3.8. Acridine orange/Ethidium Bromide (AO/EtBr) Dual Staining

2.3.9. TBARS Assay for Lipid Peroxidation

2.3.10. Determination of Free Unsaturated Lipid Content

2.3.11. Intracellular Thiols Detection

2.3.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

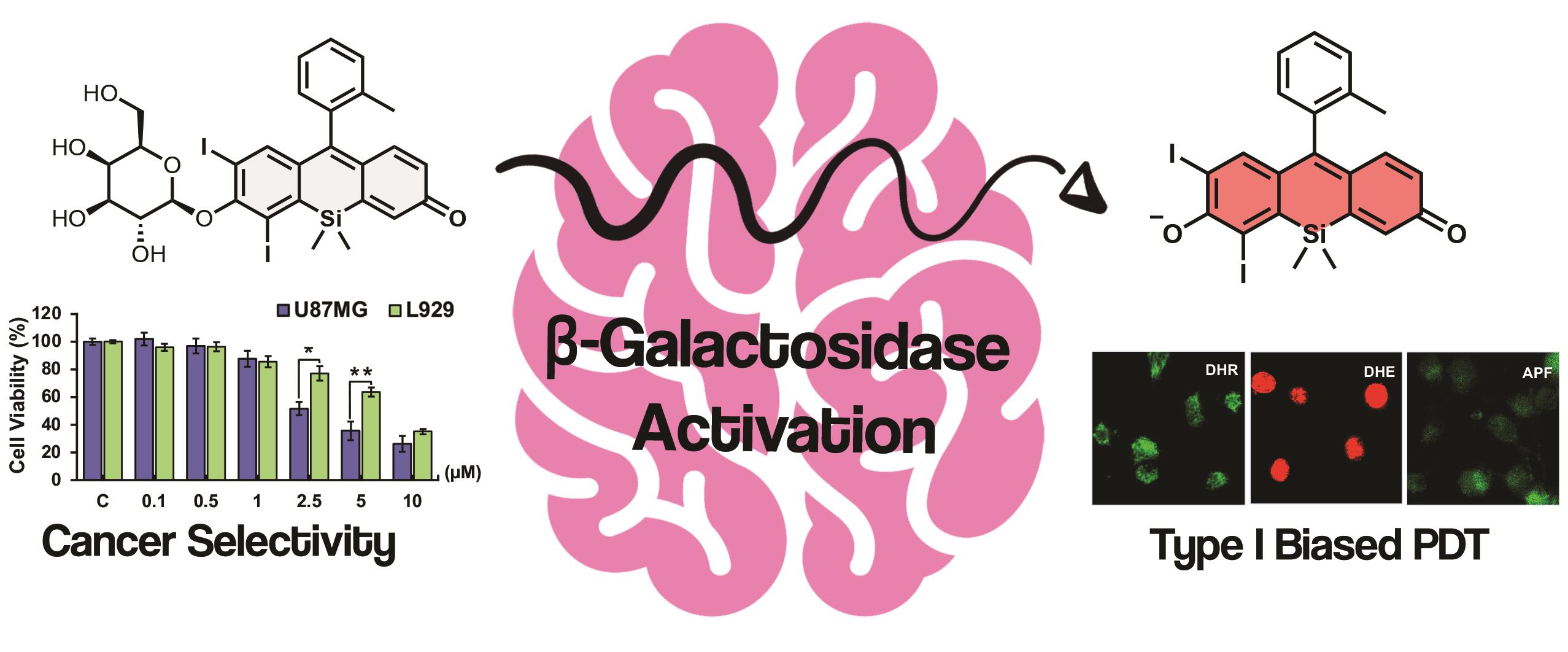

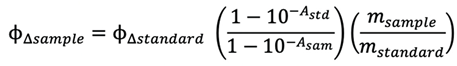

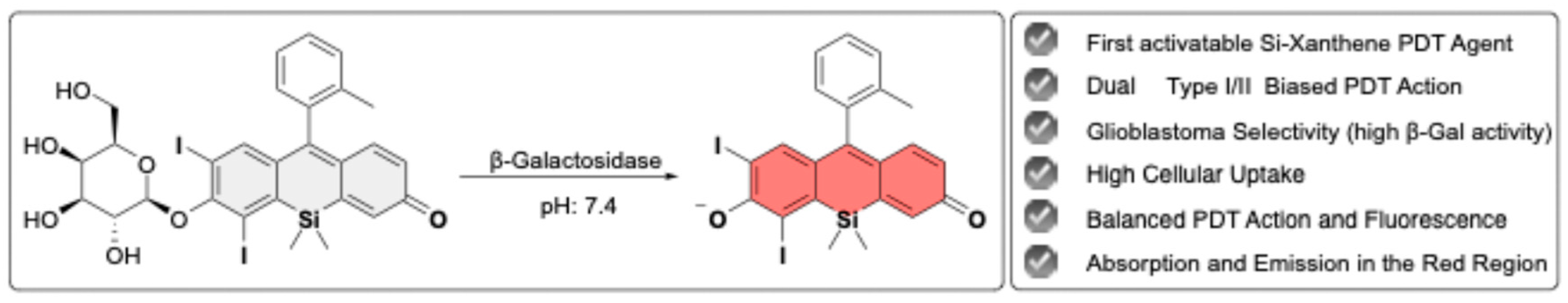

3.1. Synthesis of Gal-SiX

3.2. Optical Characterization

3.3. In vitro Studies

3.3.1. Cytotoxicity Analysis

3.3.2. Cellular Uptake and Activation-induced Cell Death

3.3.3. Subcellular Localization

3.3.4. Mechanistic Insights into Type I/II Mediated Phototoxicity

3.3.5. Dual Type I/II Based Oxidative Mechanisms Underlying Cell Death

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Debela, D.T.; Muzazu, S.G.Y.; Heraro, K.D.; Ndalama, M.T.; Mesele, B.W.; Haile, D.C.; Kitui, S.K.; Manyazewal, T. New Approaches and Procedures for Cancer Treatment: Current Perspectives. SAGE Open Med 2021, 9, 20503121211034370. [CrossRef]

- Ghufran, S.; Priyanka, S.; Govinda, R.D. The Global Concern for Cancer Emergence and Its Prevention: A Systematic Unveiling of the Present Scenario. In Bioprospecting of Tropical Medicinal Plants; Springer Nature : Switzerland, 2023; pp. 1429–1455.

- Aldape, K.; Brindle, K.M.; Chesler, L.; Chopra, R.; Gajjar, A.; Gilbert, M.R.; Gottardo, N.; Gutmann, D.H.; Hargrave, D.; Holland, E.C.; et al. Challenges to Curing Primary Brain Tumours. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2019, 16, 509–520. [CrossRef]

- Khalighi, S.; Reddy, K.; Midya, A.; Pandav, K.B.; Madabhushi, A.; Abedalthagafi, M. Artificial Intelligence in Neuro-Oncology: Advances and Challenges in Brain Tumor Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Precision Treatment. NPJ Precis Oncol 2024, 8, 80. [CrossRef]

- Koo, Y.E.L.; Reddy, G.R.; Bhojani, M.; Schneider, R.; Philbert, M.A.; Rehemtulla, A.; Ross, B.D.; Kopelman, R. Brain Cancer Diagnosis and Therapy with Nanoplatforms. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2006, 58, 1556–1577. [CrossRef]

- Brinkman, T.M.; Krasin, M.J.; Liu, W.; Armstrong, G.T.; Ojha, R.P.; Sadighi, Z.S.; Gupta, P.; Kimberg, C.; Srivastava, D.; Merchant, T.E.; et al. Long-Term Neurocognitive Functioning and Social Attainment in Adult Survivors of Pediatric CNS Tumors: Results from the St Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2016, 34, 1358–1367. [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, Q.T.; Gittleman, H.; Liao, P.; Vecchione-Koval, T.; Wolinsky, Y.; Kruchko, C.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Other Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2010-2014. Neuro Oncol 2017, 19, v1–v88. [CrossRef]

- Verdugo, E.; Puerto, I.; Medina, M.Á. An Update on the Molecular Biology of Glioblastoma, with Clinical Implications and Progress in Its Treatment. Cancer Commun 2022, 42, 1083–1111. [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, M.R.; Dignam, J.J.; Armstrong, T.S.; Wefel, J.S.; Blumenthal, D.T.; Vogelbaum, M.A.; Colman, H.; Chakravarti, A.; Pugh, S.; Won, M.; et al. A Randomized Trial of Bevacizumab for Newly Diagnosed Glioblastoma. New England Journal of Medicine 2014, 370, 699–708. [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, S.K.; Porter, S.L.; Rizk, N.; Sheng, Y.; McKaig, T.; Burnett, K.; White, B.; Nesbitt, H.; Matin, R.N.; McHale, A.P.; et al. Rose Bengal-Amphiphilic Peptide Conjugate for Enhanced Photodynamic Therapy of Malignant Melanoma. J Med Chem 2020, 63, 1328–1336. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Lin, H.; Wu, J.; Pang, X.; Zhou, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, P.; Leung, W.; Lee, H.; Jiang, S.; et al. Pyridine-Embedded Phenothiazinium Dyes as Lysosome-Targeted Photosensitizers for Highly Efficient Photodynamic Antitumor Therapy. J Med Chem 2020, 63, 4896–4907. [CrossRef]

- Dolmans, D.E.J.G.J.; Fukurmura, D.; Jain, R.K. Photodynamic Therapy for Cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2003, 3, 380–387. [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Fu, L.H.; Li, C.; Lin, J.; Huang, P. Conquering the Hypoxia Limitation for Photodynamic Therapy. Advanced Materials 2021, 33.

- Wang, Y.; Luo, S.; Wu, Y.; Tang, P.; Liu, J.; Liu, Z.; Shen, S.; Ren, H.; Wu, D. Highly Penetrable and On-Demand Oxygen Release with Tumor Activity Composite Nanosystem for Photothermal/Photodynamic Synergetic Therapy. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 17046–17062. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Bo, S.; Feng, T.; Qin, X.; Wan, Y.; Jiang, S.; Li, C.; Lin, J.; Wang, T.; Zhou, X.; et al. A Versatile Theranostic Nanoemulsion for Architecture-Dependent Multimodal Imaging and Dually Augmented Photodynamic Therapy. Advanced Materials 2019, 31. [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.H.; Wan, Y.; Li, C.; Qi, C.; He, T.; Yang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, J.; Huang, P. Biodegradable Calcium Phosphate Nanotheranostics with Tumor-Specific Activatable Cascade Catalytic Reactions-Augmented Photodynamic Therapy. Adv Funct Mater 2021, 31. [CrossRef]

- Huo, M.; Wang, L.; Zhang, L.; Wei, C.; Chen, Y.; Shi, J. Photosynthetic Tumor Oxygenation by Photosensitizer-Containing Cyanobacteria for Enhanced Photodynamic Therapy. Angewandte Chemie 2020, 132, 1922–1929. [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Liu, T.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Z.; Ye, J.; Li, C.X.; Liu, W.; Li, R.; Feng, J.; Zhang, X.Z. O2 Economizer for Inhibiting Cell Respiration to Combat the Hypoxia Obstacle in Tumor Treatments. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 1784–1794. [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.T.; Zhou, T.J.; Cui, P.F.; He, Y.J.; Chang, X.; Xing, L.; Jiang, H.L. Modulation of Intracellular Oxygen Pressure by Dual-Drug Nanoparticles to Enhance Photodynamic Therapy. Adv Funct Mater 2019, 29. [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Chao, Y.; Xiang, J.; Han, X.; Song, G.; Feng, L.; Liu, J.; Yang, G.; Chen, Q.; Liu, Z. Hyaluronidase To Enhance Nanoparticle-Based Photodynamic Tumor Therapy. Nano Lett 2016, 16, 2512–2521. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Duo, Y.; Suo, M.; Zhao, Y.; Xia, L.; Zheng, Z.; Li, Y.; Tang, B.Z. Tumor-Exocytosed Exosome/Aggregation-Induced Emission Luminogen Hybrid Nanovesicles Facilitate Efficient Tumor Penetration and Photodynamic Therapy. Angewandte Chemie - International Edition 2020, 59, 13836–13843. [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Jia, F.; Chen, S.; Shen, Z.; Jin, Q.; Fu, G.; Ji, J. Nitric Oxide as an All-Rounder for Enhanced Photodynamic Therapy: Hypoxia Relief, Glutathione Depletion and Reactive Nitrogen Species Generation. Biomaterials 2018, 187, 55–65. [CrossRef]

- Krzykawska-Serda, M.; Dąbrowski, J.M.; Arnaut, L.G.; Szczygieł, M.; Urbańska, K.; Stochel, G.; Elas, M. The Role of Strong Hypoxia in Tumors after Treatment in the Outcome of Bacteriochlorin-Based Photodynamic Therapy. Free Radic Biol Med 2014, 73, 239–251. [CrossRef]

- Luo, T.; Ni, K.; Culbert, A.; Lan, G.; Li, Z.; Jiang, X.; Kaufmann, M.; Lin, W. Nanoscale Metal-Organic Frameworks Stabilize Bacteriochlorins for Type i and Type II Photodynamic Therapy. J Am Chem Soc 2020, 142, 7334–7339. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Xiong, T.; Du, J.; Tian, R.; Xiao, M.; Guo, L.; Long, S.; Fan, J.; Sun, W.; Shao, K.; et al. Superoxide Radical Photogenerator with Amplification Effect: Surmounting the Achilles’ Heels of Photodynamic Oncotherapy. J Am Chem Soc 2019, 141, 2695–2702. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Yu, Z.; Meng, X.; Zhao, W.; Shi, Z.; Yang, Z.; Dong, H.; Zhang, X. A Bacteriochlorin-Based Metal–Organic Framework Nanosheet Superoxide Radical Generator for Photoacoustic Imaging-Guided Highly Efficient Photodynamic Therapy. Advanced Science 2019, 6. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Xia, J.; Tian, R.; Wang, J.; Fan, J.; Du, J.; Long, S.; Song, X.; Foley, J.W.; Peng, X. Near-Infrared Light-Initiated Molecular Superoxide Radical Generator: Rejuvenating Photodynamic Therapy against Hypoxic Tumors. J Am Chem Soc 2018, 140, 14851–14859. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.N.; Qi, S.; Kim, S.; Kwon, N.; Kim, G.; Yim, Y.; Park, S.; Yoon, J. An Emerging Molecular Design Approach to Heavy-Atom-Free Photosensitizers for Enhanced Photodynamic Therapy under Hypoxia. J Am Chem Soc 2019, 141, 16243–16248. [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Wei, H.; Li, Q.; Su, X.; Liu, S.; Zhang, K.Y.; Lv, W.; Zhao, Q.; Li, X.; Huang, W. Achieving Efficient Photodynamic Therapy under Both Normoxia and Hypoxia Using Cyclometalated Ru(II) Photosensitizer through Type i Photochemical Process. Chem Sci 2018, 9, 502–512. [CrossRef]

- Ou, M.; Pan, C.; Yu, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, H.; Cheng, Q.; Wu, M.; Ji, X.; Mei, L. Two-Dimensional Highly Oxidized Ilmenite Nanosheets Equipped with Z-Scheme Heterojunction for Regulating Tumor Microenvironment and Enhancing Reactive Oxygen Species Generation. Chemical Engineering Journal 2020, 390. [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Ou, M.; Cheng, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, F.; Xia, D.; Mei, L.; Ji, X. Z-Scheme Heterojunction Functionalized Pyrite Nanosheets for Modulating Tumor Microenvironment and Strengthening Photo/Chemodynamic Therapeutic Effects. Adv Funct Mater 2020, 30. [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Wang, Z.; Dai, H.; Lv, X.; Ma, Q.; Yang, D.P.; Shao, J.; Xu, Z.; Dong, X. Boosting O2•− Photogeneration via Promoting Intersystem-Crossing and Electron-Donating Efficiency of Aza-BODIPY-Based Nanoplatforms for Hypoxic-Tumor Photodynamic Therapy. Small Methods 2020, 4. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Kong, X.; Chang, Y.; Feng, Y.; Zheng, R.; Wu, X.; Xu, K.; Gao, X.; Zhang, H. Spatiotemporally Synchronous Oxygen Self-Supply and Reactive Oxygen Species Production on Z-Scheme Heterostructures for Hypoxic Tumor Therapy. Advanced Materials 2020, 32. [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Zhang, J.; Wan, Y.; Fang, F.; Chen, R.; Shen, D.; Huang, Z.; Tian, S.; Xiao, Y.; Li, X.; et al. Dual Fenton Catalytic Nanoreactor for Integrative Type-I and Type-II Photodynamic Therapy against Hypoxic Cancer Cells. ACS Appl Bio Mater 2019, 2, 3854–3860. [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Ou, M.; Cheng, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, F.; Xia, D.; Mei, L.; Ji, X. Z-Scheme Heterojunction Functionalized Pyrite Nanosheets for Modulating Tumor Microenvironment and Strengthening Photo/Chemodynamic Therapeutic Effects. Adv Funct Mater 2020, 30. [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, K.; Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Deng, X.; Cheng, Z.; Lian, H.; Li, C.; Lin, J. UV-Emitting Upconversion-Based TiO2 Photosensitizing Nanoplatform: Near-Infrared Light Mediated in Vivo Photodynamic Therapy via Mitochondria-Involved Apoptosis Pathway. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 2584–2599. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhao, K.; Bu, W.; Ni, D.; Liu, Y.; Feng, J.; Shi, J. Marriage of Scintillator and Semiconductor for Synchronous Radiotherapy and Deep Photodynamic Therapy with Diminished Oxygen Dependence. Angewandte Chemie - International Edition 2015, 54, 1770–1774. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, M.; Cheng, D.; Zhu, J.; Cheng, B.; Miao, M.; Li, Q.; Miao, Q. Self-Assembled Type I Nanophotosensitizer with NIR-II Fluorescence Emission for Imaging-Guided Targeted Phototherapy of Glioblastoma. ACS Appl Nano Mater 2024, 7, 22117–22129. [CrossRef]

- Lismont, M.; Dreesen, L.; Wuttke, S. Metal-Organic Framework Nanoparticles in Photodynamic Therapy: Current Status and Perspectives. Adv Funct Mater 2017, 27, 1606314. [CrossRef]

- Chilakamarthi, U.; Giribabu, L. Photodynamic Therapy: Past, Presentand Future. The Chemical Record 2017, 17, 775–802.

- Yin, H.; Stephenson, M.; Gibson, J.; Sampson, E.; Shi, G.; Sainuddin, T.; Monro, S.; McFarland, S.A. In Vitro Multiwavelength PDT with 3IL States: Teaching Old Molecules New Tricks. Inorg Chem 2014, 53, 4548–4559. [CrossRef]

- Yoon, I.; Li, J.Z.; Shim, Y.K. Advance in Photosensitizers and Light Delivery for Photodynamic Therapy. Clin Endosc 2013, 46, 7–23. [CrossRef]

- Karaman, O.; Alkan, G.A.; Kizilenis, C.; Akgul, C.C.; Gunbas, G. Xanthene Dyes for Cancer Imaging and Treatment: A Material Odyssey. Coord Chem Rev 2023, 475, 214841. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Liu, J.; Fan, J.; Chao, H.; Peng, X. Recent Progress in Photosensitizers for Overcoming the Challenges of Photodynamic Therapy: From Molecular Design to Application. Chem Soc Rev 2021, 50, 4185–4219.

- Agostinis, P.; Berg, K.; Cengel, K.A.; Foster, T.H.; Girotti, A.W.; Gollnick, S.O.; Hahn, S.M.; Hamblin, M.R.; Juzeniene, A.; Kessel, D.; et al. Photodynamic Therapy of Cancer: An Update. CA Cancer J Clin 2011, 61, 250–281.

- Chen, X.; Pradhan, T.; Wang, F.; Kim, J.S.; Yoon, J. Fluorescent Chemosensors Based on Spiroring-Opening of Xanthenes and Related Derivatives. Chem Rev 2012, 112, 1910–1956. [CrossRef]

- Samanta, S.; Lai, K.; Wu, F.; Liu, Y.; Cai, S.; Yang, X.; Qu, J.; Yang, Z. Xanthene, Cyanine, Oxazine and BODIPY: The Four Pillars of the Fluorophore Empire for Super-Resolution Bioimaging. Chem Soc Rev 2023, 52, 7197–7261.

- Bergmann, E. V.; Cavalaro, A.P.B.; Kimura, N.M.; Zanuto, V.S.; Astrath, N.G.C.; Herculano, L.S.; Malacarne, L.C. Photophysical Characterization of Xanthene Dyes. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc 2025, 327, 125345. [CrossRef]

- Kamino, S.; Uchiyama, M. Xanthene-Based Functional Dyes: Towards New Molecules Operating in the near-Infrared Region. Org Biomol Chem 2023, 21, 2458–2471. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Ding, J.; Zheng, F.; Fang, Y.; Huang, W.; Yin, Y.; Zeng, W. Synergistic Cancer Therapy: An NIR-Activated Methylene Blue-Nitrogen Mustard Prodrug for Combined Chemotherapy and Photodynamic Therapy. J Med Chem 2025, 68, 7630–7641. [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Xu, F.; Wang, Y.; Shang, J.; Li, S.; Xu, X.; Liu, Z.; He, W.; Guo, Z.; Chen, Y. Photoinduced Synergism of Ferroptosis/Pyroptosis/Oncosis by an O2-Independent Photocatalyst for Enhanced Tumor Immunotherapy. J Am Chem Soc 2025, 147, 11132–11144. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Mao, X.Q.; Wang, X.Z.; Liao, Y.C.; Yin, X.Y.; Wu, H.L.; Chen, T.Y.; Liu, M.Q.; Wang, T.; Yu, R.Q. Data-Driven Discovery of near-Infrared Type I Photosensitizers for RNA-Targeted Tumor Photodynamic Therapy. Chem Sci 2025, 16, 14455–14467. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Benson, S.; Mendive-Tapia, L.; Nestoros, E.; Lochenie, C.; Seah, D.; Chang, K.Y.; Feng, Y.; Vendrell, M. Enzyme-Activatable Near-Infrared Hemicyanines as Modular Scaffolds for in Vivo Photodynamic Therapy. Angewandte Chemie - International Edition 2024, 63. [CrossRef]

- Egawa, T.; Koide, Y.; Hanaoka, K.; Komatsu, T.; CooTeraiper, T.; Nagano, T. Development of a Fluorescein Analogue, TokyoMagenta, as a Novel Scaffold for Fluorescence Probes in Red Region. Chemical Communications 2011, 47, 4162–4164. [CrossRef]

- Fukazawa, A.; Suda, S.; Taki, M.; Yamaguchi, E.; Grzybowski, M.; Sato, Y.; Higashiyama, T.; Yamaguchi, S. Phospha-Fluorescein: A Red-Emissive Fluorescein Analogue with High Photobleaching Resistance. Chemical Communications 2016, 52, 1120–1123. [CrossRef]

- Mo, F.; Pellerino, A.; Soffietti, R.; Rudà, R. Blood-Brain Barrier in Brain Tumors: Biology and Clinical Relevance. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 12654. [CrossRef]

- Arvanitis, C.D.; Ferraro, G.B.; Jain, R.K. The Blood–Brain Barrier and Blood–Tumour Barrier in Brain Tumours and Metastases. Nat Rev Cancer 2020, 20, 26–41. [CrossRef]

- Karaman, O.; Yesilcimen, E.; Forough, M.; Elmazoglu, Z.; Gunbas, G. Drastic Impact of Donor Substituents on Xanthenes in the PDT of Glioblastoma. JACS Au 2025, 5, 5346–5358. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Miao, L.; Zhou, W.; Chen, Y.; Ruan, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, G.; Bao, P.; Qiao, Q.; Xu, Z. Enhancing the Photostability of Red Fluorescent Proteins through FRET with Si-Rhodamine for Dynamic Super-Resolution Fluorescence Imaging. Chem Sci 2025, 16, 10476–10486. [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Zhou, J.; Geng, Y.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, Z.; Jin, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, Z. Lysosome-Targeted Si-Rhodamine Derivative for NO Imaging in Mice Brain with Neurological Diseases. Anal Chem 2025, 97, 12728–12735. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Jiao, C.; Liu, X.; Yang, Y.; Ren, J.; Wang, P.; Pan, X.; Wu, Y.; Yan, Z.; Zeng, J. A Highly Sensitive and Fast-Response Fluorescence Nanoprobe for in Vivo Imaging of Hypochlorous Acid. J Hazard Mater 2025, 487, 137282. [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Li, H.; Kong, D.; Feng, X.; Li, C.; Cui, X.; Wang, T. Dibutylated Si-Fluorescein: Enhanced Hydrophobicity for Fluorogenic Labeling in Vivo. Dyes and Pigments 2025, 240, 112841. [CrossRef]

- Cetin, S.; Elmazoglu, Z.; Karaman, O.; Gunduz, H.; Gunbas, G.; Kolemen, S. Balanced Intersystem Crossing in Iodinated Silicon-Fluoresceins Allows New Class of Red Shifted Theranostic Agents. ACS Med Chem Lett 2021, 12, 752–757. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Zeng, G.; Zhu, W.; Li, Y.; Dong, X.; Zhang, G.; Fan, X.; Wang, J.; Wu, Y.; Tang, B.Z. A Selective and Light-up Fluorescent Probe for β-Galactosidase Activity Detection and Imaging in Living Cells Based on an AIE Tetraphenylethylene Derivative. Chemical Communications 2017, 53, 4505–4508. [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Liu, J.; Tao, M.; Wang, M.; Ren, X.; Hai, Z. β-Galactosidase-Activatable Fluorescent and Photoacoustic Imaging of Tumor Senescence. Anal Chem 2023, 95, 10481–10485. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.K.; Bhattacharya, M.; Barlow, J.J. Glycosyltransferase and Glycosidase Activities in Ovarian Cancer Patients. Cancer Res 1979, 39, 1943–1951.

- Valieva, Y.; Ivanova, E.; Fayzullin, A.; Kurkov, A.; Igrunkova, A. Senescence-Associated β-Galactosidase Detection in Pathology. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2309. [CrossRef]

- Kubo, H.; Murayama, Y.; Ogawa, S.; Matsumoto, T.; Yubakami, M.; Ohashi, T.; Kubota, T.; Okamoto, K.; Kamiya, M.; Urano, Y.; et al. β-Galactosidase Is a Target Enzyme for Detecting Peritoneal Metastasis of Gastric Cancer. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 10664. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.A.; Pan, H.; Wang, Z.; Gao, J.; Tan, J.; Ouyang, Z.; Guo, W.; Gu, X. Imaging of Ovarian Cancers Using Enzyme Activatable Probes with Second Near-Infrared Window Emission. Chemical Communications 2020, 56, 2731–2734. [CrossRef]

- Wielgat, P.; Walczuk, U.; Szajda, S.; Bień, M.; Zimnoch, L.; Mariak, Z.; Zwierz, K. Activity of Lysosomal Exoglycosidases in Human Gliomas. J Neurooncol 2006, 80, 243–249. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Shen, X.; Feng, W.; Yang, D.; Jin, L.; Wang, J.; Wang, M.; Ting, Z.; Xue, F.; Zhang, J.; et al. D-Galactose Induces Senescence of Glioblastoma Cells through YAP-CDK6 Pathway. Aging (Albany NY) 2020, 12, 18501.

- Chen, J.A.; Guo, W.; Wang, Z.; Sun, N.; Pan, H.; Tan, J.; Ouyang, Z.; Fu, W.; Wang, Y.; Hu, W.; et al. In Vivo Imaging of Senescent Vascular Cells in Atherosclerotic Mice Using a β-Galactosidase-Activatable Nanoprobe. Anal Chem 2020, 92, 12613–12621. [CrossRef]

- Gu, K.; Qiu, W.; Guo, Z.; Yan, C.; Zhu, S.; Yao, D.; Shi, P.; Tian, H.; Zhu, W.H. An Enzyme-Activatable Probe Liberating AIEgens: On-Site Sensing and Long-Term Tracking of β-Galactosidase in Ovarian Cancer Cells. Chem Sci 2019, 10, 398–405. [CrossRef]

- Almammadov, T.; Elmazoglu, Z.; Atakan, G.; Kepil, D.; Aykent, G.; Kolemen, S.; Gunbas, G. Locked and Loaded: SS-Galactosidase Activated Photodynamic Therapy Agent Enables Selective Imaging and Targeted Treatment of Glioblastoma Multiforme Cancer Cells. ACS Appl Bio Mater 2022, 5, 4284–4293. [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Standardization Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices—Part 5: Tests for in Vitro Cytotoxicity; ISO 10993-5:2009; Geneva, 2009;

- Onaral, F.G.; Silindir-Gunay, M.; Uluturk, S.; Ozturk, S.C.; Cakir-Aktas, C.; Esendagli, G. Development and In Vitro and In Vivo Efficacy Investigation of Multifunctional, Targeted, Theranostic Liposomes for Imaging and Photodynamic Therapy of Glioblastoma. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol 2024, 101. [CrossRef]

- Chiba, M.; Kamiya, M.; Tsuda-Sakurai, K.; Fujisawa, Y.; Kosakamoto, H.; Kojima, R.; Miura, M.; Urano, Y. Activatable Photosensitizer for Targeted Ablation of LacZ-Positive Cells with Single-Cell Resolution. ACS Cent Sci 2019, 5, 1676–1681. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Wong, K. High Performance Enzyme Kinetics of Turnover, Activation and Inhibition for Translational Drug Discovery. Expert Opin Drug Discov 2017, 12, 17–37.

- Markovic, M.; Ben-Shabat, S.; Dahan, A. Computational Simulations to Guide Enzyme-Mediated Prodrug Activation. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21.

- Valieva, Y.; Ivanova, E.; Fayzullin, A.; Kurkov, A.; Igrunkova, A. Senescence-Associated β-Galactosidase Detection in Pathology. Diagnostics 2022, 12.

- Bahramikia, S.; Shirzadi, N.; Akbari, V. Protective Effects of Pyrogallol and Caffeic Acid against Fe2+ -Ascorbate-Induced Oxidative Stress in the Wistar Rats Liver: An in Vitro Study. Heliyon 2025, 11. [CrossRef]

- Bodnár, B.R.; Ghosal, S.; Kestecher, B.M.; Királyhidi, P.; Försönits, A.; Fekete, N.; Bugyik, E.; Komlósi, Z.I.; Pállinger, É.; Nagy, G.; et al. Isolation and Characterization of Tissue-Derived Extracellular Vesicles from Mouse Lymph Nodes. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26, 6092. [CrossRef]

- Ginet, S.R.; Gonzalez, F.; Marano, M.L.; Salecha, M.D.; Reiner, J.E.; Caputo, G.A. Evaluation of the Ellman’s Reagent Protocol for Free Sulfhydryls Under Protein Denaturing Conditions. Analytica 2025, 6, 18. [CrossRef]

- Smaga, L.P.; Pino, N.W.; Ibarra, G.E.; Krishnamurthy, V.; Chan, J. A Photoactivatable Formaldehyde Donor with Fluorescence Monitoring Reveals Threshold to Arrest Cell Migration. J Am Chem Soc 2020, 142, 680–684. [CrossRef]

- Hirabayashi, K.; Hanaoka, K.; Takayanagi, T.; Toki, Y.; Egawa, T.; Kamiya, M.; Komatsu, T.; Ueno, T.; Terai, T.; Yoshida, K.; et al. Analysis of Chemical Equilibrium of Silicon-Substituted Fluorescein and Its Application to Develop a Scaffold for Red Fluorescent Probes. Anal Chem 2015, 87, 9061–9069. [CrossRef]

- Crovetto, L.; Orte, A.; Paredes, J.M.; Resa, S.; Valverde, J.; Castello, F.; Miguel, D.; Cuerva, J.M.; Talavera, E.M.; Alvarez-Pez, J.M. Photophysics of a Live-Cell-Marker, Red Silicon-Substituted Xanthene Dye. Journal of Physical Chemistry A 2015, 119, 10854–10862. [CrossRef]

- Best, Q.A.; Sattenapally, N.; Dyer, D.J.; Scott, C.N.; McCarroll, M.E. PH-Dependent Si-Fluorescein Hypochlorous Acid Fluorescent Probe: Spirocycle Ring-Opening and Excess Hypochlorous Acid-Induced Chlorination. J Am Chem Soc 2013, 135, 13365–13370. [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, F.; Helman, W.P.; Ross, A.B. Quantum Yields for the Photosensitized Formation of the Lowest Electronically Excited Singlet State of Molecular Oxygen in Solution. J Phys Chem Ref Data 1993, 22, 113–262. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wang, L.; Ma, X.; Wu, Y.; Hou, S. Kill Two Birds with One Stone: A near-Infrared Ratiometric Fluorescent Probe for Simultaneous Detection of β-Galactosidase in Senescent and Cancer Cells. Sens Actuators B Chem 2022, 367, 132061–132072. [CrossRef]

- Banti, C.N.; Papatriantafyllopoulou, C.; Papachristodoulou, C.; Hatzidimitriou, A.G.; Hadjikakou, S.K. New Apoptosis Inducers Containing Anti-Inflammatory Drugs and Pnictogen Derivatives: A New Strategy in the Development of Mitochondrial Targeting Chemotherapeutics. J Med Chem 2023, 66, 4131–4149. [CrossRef]

- Kot, Y.; Klochkov, V.; Prokopiuk, V.; Sedyh, O.; Tryfonyuk, L.; Grygorova, G.; Karpenko, N.; Tomchuk, O.; Kot, K.; Onishchenko, A.; et al. GdVO4:Eu3+ and LaVO4:Eu3+ Nanoparticles Exacerbate Oxidative Stress in L929 Cells: Potential Implications for Cancer Therapy. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 11687. [CrossRef]

- Baeza-Morales, A.; Pascual-García, S.; Martínez-Peinado, P.; Navarro-Sempere, A.; Segovia, Y.; Medina-García, M.; Pujalte-Satorre, C.; García, M.M.; Martínez-Espinosa, R.M.; Sempere-Ortells, J.M. Bacterioruberin Extract from Haloferax Mediterranei Induces Apoptosis and Cell Cycle Arrest in Myeloid Leukaemia Cell Lines. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 23485. [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, R.; Pereira, P.; Freitas, C.; De Freitas Silva, A.; Midlej, V.; Conte-Júnior, C.; Paschoalin, V. Nano-Encapsulated Taro Lectin Can Cross an in Vitro Blood-Brain Barrier, Induce Apoptosis and Autophagy and Inhibit the Migration of Human U-87 MG Glioblastoma Cells. Int J Nanomedicine 2025, Volume 20, 5573–5591. [CrossRef]

- Rana, N.; Chaudhary, P.K.; Prasad, R.; Sankar, M. Photodynamic Evaluation of A2BC Aminoporphyrins: Synthesis, Characterization, and Cellular Impact. ACS Appl Bio Mater 2025, 8, 5098–5108. [CrossRef]

- Doan, V.T.H.; Komatsu, Y.; Matsui, H.; Kawazoe, N.; Chen, G.; Yoshitomi, T. Singlet Oxygen-Generating Cell-Adhesive Glass Surfaces for the Fundamental Investigation of Plasma Membrane-Targeted Photodynamic Therapy. Free Radic Biol Med 2023, 207, 239–246. [CrossRef]

- Borghei, Y.S.; Hamidieh, A.A.; Lu, Y.; Hosseinkhani, S. Organic–Inorganic Hybrid Nanoflowers as a New Biomimetic Platform for ROS-Induced Apoptosis by Photodynamic Therapy. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2023, 191, 106569. [CrossRef]

- Saczuk, K.; Kassem, A.; Dudek, M.; Sánchez, D.P.; Khrouz, L.; Allain, M.; Welch, G.C.; Sabouri, N.; Monnereau, C.; Josse, P.; et al. Organelle-Specific Thiochromenocarbazole Imide Derivative as a Heavy-Atom-Free Type I Photosensitizer for Biomolecule-Triggered Image-Guided Photodynamic Therapy. J Phys Chem Lett 2025, 16, 2273–2282. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Xie, Y.; Wan, Q.; Tian, J.; Liang, J.; Zhou, J.; Song, M.; Zhou, X.; Teng, M. Mechanism Research of Type I Reactive Oxygen Species Conversion Based on Molecular and Aggregate Levels for Tumor Photodynamic Therapy. Aggregate 2024, 5. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.-Q.; Tse, A.K.-W.; Koncošová, M.; Ruml, T.; Tse, Y.-C.; Liu, C.-J.; Zelenka, J.; Kirakci, K.; Lang, K.; Lee, C.-S.; et al. Fluorescein-Functionalized Iridium(III) Complexes as Dual-Mode Type I Photosensitizers for Hypoxia-Tolerant Photodynamic and X-Ray-Induced Therapy. Inorg Chem 2025, 64, 10894–10905. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, T.; Chen, Y.; Li, M.; Chen, X.; Peng, X. Recent Progress of Molecular Design in Organic Type I Photosensitizers. Small 2025, 21. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Qin, T.; Wang, W.; Zhou, X.; Lin, F.; Liang, G.; Yang, Z.; Chi, Z.; Tang, B.Z. Selenium-Containing Type-I Organic Photosensitizers with Dual Reactive Oxygen Species of Superoxide and Hydroxyl Radicals as Switch-Hitter for Photodynamic Therapy. Advanced Science 2023, 10. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Lim, A.; Elmadbouh, O.H.M.; Edderkaoui, M.; Osipov, A.; Mathison, A.J.; Urrutia, R.; Liu, T.; Wang, Q.; Pandol, S.J. Verteporfin Induces Lipid Peroxidation and Ferroptosis in Pancreatic Cancer Cells. Free Radic Biol Med 2024, 212, 493–504. [CrossRef]

| PS | λabs (nm)1 | λems (nm)1 | φF (%)1,2 | ΦΔ(%)1,3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gal-SiX | 486 | Not detectable | Not detectable | n.d.d |

| SiX | 598 | 613 | 6.4 | 52 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).