1. Introduction

Let be the completed Riemann –function. It is entire of order 1, satisfies and its zeros in the critical strip are exactly the nontrivial zeros of .

This note formalizes a single geometric idea:

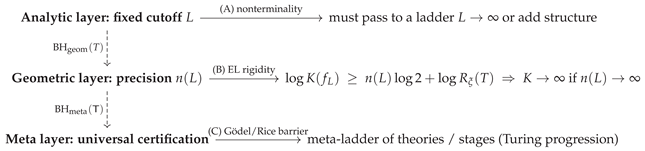

An “infinite-energy obstruction” typically arises as a limit of a family of finite-window problems. The same unbounded energy is therefore simultaneously an obstruction to a global bounded-distortion scenario and the generator of an infinite hierarchy of finite-stage quantitative questions.

Concretely, we define for each height cutoff an energy as an infimum of over a class of quasiconformal maps satisfying a corridor control constraint. We then derive sharp extremal-length lower bounds for and for the associated Teichmüller-type energy .

Remark 1 (Scope and honesty). Nothing in this paper proves RH or rules out off-critical zeros unconditionally. The functional is a geometric energy attached to a specific deformation problem (corridor-controlled axis landing on a finite window). It is meaningful whether or not RH is true, because it is defined by an infimum (which may be if the admissible class is empty).

2. Windowed Representative Off-Critical Zeros and a Canonical Corridor Radius

Let denote the set of nontrivial zeros in the strip, counted without multiplicity (for our geometric constructions, coincident zeros are a single puncture).

We will work with a uniform decomposition of the height axis into disjoint “levels” of equal height, with a buffer region that enforces disjointness.

2.1. Level intervals

Fix once and for all the

level half-height For each

define the

full level interval and its

core by

Then:

the full intervals are pairwise disjoint (as open sets) and tile up to endpoints;

the core intervals are pairwise disjoint and satisfy

2.2. Representative Off-Critical Zeros Per Level

We will select at most one representative left-half zero per level, using a deterministic rule.

Definition 1 (Active levels and representative left zero). Let . Define the set of indices whose levels lie in the window by (Equivalently, .)

For define the set of left-half zeros in the core by Call j active if , and set

If , choose a representative zero and write

Remark 2. The rule “choose the left-half zero closest to the critical line within the core” is deterministic (hence canonical in an NT sense) and ensures that, at a fixed level, all other left-half zeros in the core are farther left, hence their discs of a common radius lie outside the corridor we will define.

2.3. Canonical Corridor Radius

We choose a radius that is small enough to ensure: (i) discs sit well inside the strip rectangle, and (ii) discs do not cross the critical line for these left-half representatives.

Definition 2 (Canonical corridor radius). Let . If , set If , set .

Define the corridor radius by

Remark 3. If is nonempty, then ensures that for every active level j, so the disc lies strictly in the left half of the strip.

3. Axis-Landing Source/Target Domains and the Energy

3.1. The Strip Rectangle Window

For define the window rectangle

3.2. Source and Target Puncture Sets

Fix and write for brevity.

Definition 3 (Source punctures from representative off-critical zeros). For each active level define the symmetric pair at height : Define the source puncture set

Remark 4. We do not include the full set of zeros of ξ in the window; we include only one canonical off-critical pair per active level. This is deliberate: it produces a disjoint stack of corridors to which extremal length applies cleanly.

Definition 4 (Axis-landing target punctures). Let . Define the fixed (per-T) axis-landing horizontal offset For each active level define the target centers at the same height : Define the target puncture set

3.3. The Domains

Definition 5 (Source/target domains). Let . Define the source domain and the target domain

Remark 5 (Disjointness is automatic). Because each representative height lies in the core and the cores are separated by at least 1, and because , the discs in distinct levels are disjoint. Horizontally, the left and right discs in the same level are separated by at least (see below).

3.4. Corridors and corridor control

For each active level

j define the

middle corridor strip in that level:

The key geometric fact is that is disjoint from the two discs around and because the left disc lies in and the right disc lies in for all y.

Define the corridor widths:

Lemma 1 (Positivity of source corridor widths). If then .

Proof. For we have and , hence . Therefore □

Definition 6 (Admissible corridor-controlled quasiconformal maps). Fix and let . Let be the set of all homeomorphisms such that:

- 1.

f is K–quasiconformal for some finite ;

- 2.

f fixes the outer boundary pointwise;

- 3.

for each active level , the two boundary circles and are mapped to the corresponding target circles and ;

- 4.

(corridor control

) for every ,

Remark 6. Condition (5) is the geometric hypothesis that permits sharp extremal-length lower bounds. Without such a control, a map could route curves around corridors through more complicated parts of the punctured domain, and a clean rectangle-modulus computation would not apply.

3.5. The Energy Functionals

Definition 7 (The truncated quasiconformal energy

).

Define

with the convention .

Definition 8 (The Teichmüller-type energy

).

Define

Remark 7. In classical Teichmüller theory one defines by taking the infimum over all QC maps between two marked surfaces. Here we restrict to a specific corridor-controlled class, so is best viewed as a Teichmüller-type lower envelope for this particular deformation problem.

4. Extremal Length Preliminaries

We use the standard notion of modulus/extremal length for curve families.

Definition 9 (Modulus of a curve family). Let Γ be a family of locally rectifiable curves in a planar domain . Its modulus is where the infimum runs over all Borel such that

We record three standard facts.

Lemma 2 (Rectangle modulus). Let be a Euclidean rectangle of width and height . Let be the family of curves in Q joining the bottom side to the top side . Then

Lemma 3 (QC distortion of modulus). If is K–quasiconformal and Γ is a curve family in D, then

Lemma 4 (Additivity for disjoint supports). Let be pairwise disjoint open subsets of and let be curve families with each supported in (i.e. every curve in lies in ). Then

Proof. Write .

Upper bound. For each j choose an admissible density for with Define on and elsewhere. Then is admissible for (each curve in lies in some ), and Taking gives .

Lower bound. Let be admissible for . Then is admissible for , hence Summing over j yields , and taking the infimum over gives . □

5. Sharp Extremal–Length and Teichmüller-Type Lower Bounds for

5.1. The Curve Families

Fix and abbreviate and .

For each active level

, let

where the rectangles

and

are as in (

3).

Define the stacked curve families

5.2. Explicit Moduli

Proposition 1 (Explicit modulus formulas).

Let and . Then:

If then both moduli are 0 by convention.

Proof. Each

is a rectangle of width

and height

. Thus by Lemma 2,

Similarly, each

has width

and height 2, so

The rectangles

are pairwise disjoint because the level intervals

are disjoint, so Lemma 4 gives

and similarly for the target family. This yields (

9)–(10). □

5.3. Sharp EL-Energy and Teich-Energy Lower Bounds

Theorem 1 (Extremal-length lower bound for admissible maps).

Fix and let be K–quasiconformal. Then

(with the convention that the right-hand side is 0 if the numerator is 0). Equivalently,

whenever .

Proof. By corridor control (

5), for each active level

j we have

hence

By monotonicity of modulus under inclusion,

On the other hand, by Lemma 3,

Combining gives

which is (

11). □

Theorem 2 (Sharp EL-energy bound for

and

).

For every one has

Moreover, inserting the explicit moduli from Proposition 1, if then

Proof. For any admissible

, Theorem 1 gives

whenever the denominator is positive. Taking the infimum over

f yields (

13). The inequality (14) follows by dividing by 2.

Finally, substitute (

9) and (10) into (

13) to obtain (

15). □

6. Discussion: the “Energy Ladder” Viewpoint

Remark 8 (Why produces an infinite ladder of finite problems). The definition of is an infimum over a finite-window deformation class. Even if a global corridor-controlled bounded-distortion axis-landing deformation does not exist, each finite T yields a concrete, well-posed optimization problem: estimate or bound the minimal required to enforce the corridor control constraints on levels .

Thus the same mechanism that can produce an infinite-energy obstruction (i.e. along some sequence ) also generates an unbounded sequence of finite-scale invariants. This is a mathematically precise version of the idea that “the infinite-energy obstruction is the same energy that permits endless finite-stage theorizing.” The endlessness arises from non-compactness: one studies a diverging cutoff-energy rather than a single terminal yes/no quantity.

Remark 9 (Energy ladder principle: why yields infinitely many finite problems). Fix the corridor selection scheme and admissible class from Definitions 1–6, and define Then:

- (1)

For each finite , the windowed deformation problem defining involves only finitely many corridor constraints (namely those indexed by ). Hence each fixed-T quantity is a genuine finite-stage optimization invariant.

- (2)

-

Any global bounded-distortion corridor-controlled axis-landing deformation (which, by restriction, supplies admissible maps on all finite windows) forces a uniform bound on as .

Equivalently, if along some sequence , then there cannot exist any global corridor-controlled axis-landing deformation with bounded quasiconformal dilatation.

- (3)

If along some sequence , then for every prescribed energy threshold there exists a finite window height T such that every admissible map satisfies (equivalently, ). Thus divergence of the cutoff energies produces an unbounded ladder of finite-stage lower-bound problems.

In this precise sense, an “infinite-energy obstruction” (divergence of as ) simultaneously generates an endless sequence of concrete finite-window problems.

Proof.

Step 1: finiteness of the constraint set for each fixed T. Recall the full level intervals (here ) By definition, The condition is equivalent to the pair of inequalities i.e. Hence is a finite set, with cardinality bounded by a linear function of T. Since by construction, it follows that In particular, the puncture sets and are finite unions of pairs, and the corridor-control requirement imposes only finitely many constraints.

Therefore, for each fixed finite T the class is a deformation class on a bounded planar domain with finitely many removed discs and finitely many corridor constraints, and the number is a well-defined finite-window optimization value (possibly if ). This proves item (1).

Step 2: global bounded distortion ⇒ uniform bound on . We now formalize what is meant by a “global corridor-controlled bounded-distortion axis-landing deformation” in the only way needed for this remark:

Assume there exists a constant and a family of maps such that (For example, any single quasiconformal homeomorphism on an infinite strip configuration that satisfies the same corridor constraints at every level, when restricted to each finite window, provides such a family; moreover restriction of a K–quasiconformal map to a subdomain is still K–quasiconformal.)

Then, by definition of infimum, Thus is uniformly bounded as . Taking the contrapositive yields:

If along some sequence , then no such globally bounded-distortion corridor-controlled axis-landing family can exist. This proves item (2).

Step 3: divergence of produces an infinite ladder of finite-stage lower bounds. Assume that there exists a sequence such that Let be arbitrary. By divergence, there exists some index such that Now fix the corresponding finite window height By definition of an infimum, the inequality means precisely that equivalently Thus each energy threshold M produces a finite window height T at which the deformation problem provably requires dilatation at least . Since M can be taken arbitrarily large, this yields an unbounded sequence of finite-window constraints of increasing difficulty. This proves item (3).

Combining Steps 1–3 yields the claimed “energy ladder” interpretation: the non-compact limit problem as can fail by an infinite-energy obstruction, and that same divergence is witnessed by an endless sequence of concrete finite-window optimization problems. □

Remark 10 (When does

follow from the lower bound?).

From (15), a sufficient condition for is that the ratio tends to . This can happen, for example, if while the averaged source widths do not shrink at the same rate. No such asymptotic claim is proved here; the paper only provides the sharp extremal-length inequalities that reduce any such growth analysis to explicit corridor data.

Remark 11 (Relationship to RH). If RH holds, then for every T one expects , hence the corridor system anchored to off-critical zeros is empty and the bound becomes trivial. If RH fails and off-critical zeros exist, then is nonempty for large T and the energy is nontrivial. In either case, the inequalities in this paper are unconditional: they are pure consequences of extremal length and quasiconformal distortion within the chosen corridor-controlled class.

7. A Gödel-Style Teichmüller Ladder: Corridor-Tightening Progression

7.1. The Corridor-Tightening Successor Operator

Fix a finite window

of the form

(or any topological rectangle), and fix pairwise disjoint level rectangles

where

are disjoint open intervals of common height

and

Fix also a

base target width and define the base target rectangles

For each

define the

n-th tightened target width and rectangles by

Thus for each j.

Definition 10 (Corridor-tightening admissible class and energy). Let be the class of K–quasiconformal homeomorphisms (with whatever boundary normalization you impose in your paper) such that for every one has the corridor control inclusion Define the Teichmüller permission energy of the n-th tightening by

7.2. The Gödel-Style Non-Closure Theorem

Theorem 3 (Teichmüller–Gödel non-closure under corridor tightening).

Assume and let be the common height of the level rectangles. Then for every and every one has the sharp lower bound

In particular:

- (i)

as (unbounded permission energy);

- (ii)

(Gödel-style successor obstruction) for each finite budget there exists n such that no f with can satisfy the n-th tightened corridor control; and

- (iii)

each step costs at least additional -energy:

Proof. Fix and .

Step 1: curve families and moduli. For each , let be the family of curves in joining the bottom side of to the top side of . Since is a Euclidean rectangle of width and height h, the rectangle modulus formula gives Similarly define in ; then

Because the are disjoint, modulus is additive for the union family : Likewise, with ,

Step 2: corridor control gives modulus upper bound. Since , we have for each j, hence and by monotonicity of modulus,

Step 3: quasiconformal distortion gives modulus lower bound. If f is K–quasiconformal, then

Step 4: combine. Combining Steps 2 and 3 yields

i.e.

This proves (

17), hence (

18) by taking log and infimizing.

Items (i) and (ii) follow immediately from (

18). Item (iii) follows because (

18) implies

where

. □

Remark 12 (Why this is genuinely “Gödel-style”). The successor rule is canonical and internal to the deformation problem: it tightens the target corridor requirement by a fixed factor 2. Theorem 3 shows that no finite distortion budget is closed under this successor: every finite budget fails at some successor stage, and the required energy grows by a fixed increment per step. This is the direct geometric analogue of a “no finite closure under next-permission upgrades” theorem.

8. Gödel–Style Corridor–Tightening Progression for

8.1. Specialization of the Corridor Data to the –Window Construction

Fix

. Retain the level decomposition from §

Section 2 with

so every level has common height

Let

be the active index set from Definition 1, let

be the corridor radius from Definition 2, and write

Recall the source and base target corridors from (

3):

(If , Lemma 1 gives .)

8.2. Tightened target corridors (precision levels)

Definition 11 (Tightened target corridors).

For each and each define the precision-n target corridor by

Equivalently, the target width at precision n is

Thus for each j.

8.3. Precision-n Admissible Classes and Energies

Definition 12 (Precision-n corridor-controlled class). Let be the base corridor-controlled class from Definition 6 (mapping the punctured source domain to the punctured target domain, fixing , matching puncture circles, and satisfying the base corridor control). For define the precision-n class to be

Definition 13 (Precision-n energies). Define with the convention . Note that and .

8.4. The –Specialized Gödel–Style Tightening Bound

Theorem 4 (

–tightening lower bound (Gödel–style non-closure at fixed

T)).

Fix and assume . Let and let . Then every map satisfies

Proof. Fix and .

Step 1: curve families. For each let be the families of curves joining the bottom and top sides in the corresponding rectangles. Set

Step 2: moduli. Each level rectangle has height

. Therefore, by the rectangle modulus formula,

Since the level rectangles are disjoint in

y, modulus is additive over

j, hence

and

Step 3: corridor control ⇒ inclusion of curve families. Because , for each j we have hence By monotonicity of modulus under inclusion,

Step 4: quasiconformal distortion. If

f is

K–quasiconformal, then

Combining with Step 3 yields

hence

Insert (

26)–(

27) to obtain

Taking logarithms gives (

23). Infimizing over

gives (

24), and dividing by 2 yields (

25). □

8.5. Gödel–Style Consequences: Non-Closure of Bounded Distortion Under Successor Tightening

Corollary 1 (Finite distortion budget cannot realize arbitrarily high precision).

Fix with and set Let and . If there exists with , then necessarily

In particular, for each fixed there exists n such that no map with can satisfy the precision-n corridor control constraints.

Proof. If

and

, then Theorem 4 implies

which rearranges to (

28). The final assertion follows because the right-hand side of (

28) is finite. □

Remark 13 (Canonical successor operator (tightening by a factor 2)). For fixed T, define a “next-permission” operator on corridor-control tasks by declaring i.e. replace the target corridor width by . Then Corollary 1 is the precise Teichmüller analogue of a Gödel-II-type “non-closure under next-permission upgrades” statement: no fixed distortion cap is closed under iterating .

Equivalently, exact axis landing (formally , i.e. corridor width ) is an infinite-energy limit in the corridor-controlled class.

Remark 14 (Interpretation for RH (no overclaim)). Theorem 4 and Corollary 1 do not prove RH. They prove a geometric rigidity statement: within the corridor-controlled axis-landing deformation class, arbitrary tightening precision forces (hence Teichmüller distance) to diverge at least linearly in the tightening level n.

Thus any strategy that seeks to “push off-critical features to the critical line” by a single bounded-K quasiconformal deformation while maintaining corridor control at all scales faces a quantified obstruction: bounded distortion can only realize finitely many successor tightenings.

8.6. Representing “Nothingness” Without Contradiction:

Remark 15 (Empty admissible classes are not contradictions). In this paper we allow admissible classes to be empty and encode this as an energy blow-up rather than as an inconsistency. Concretely, whenever a class of quasiconformal maps is empty we set This convention represents “no realizers exist” (a form of geometric nothingness) in the extended real line and avoids any notational “”-style contradiction: emptiness becomes a quantified obstruction (infinite energy) rather than a paradox.

8.7. Successor Realizability: Explicit Tightening Maps

We now construct the “successor permission” in the corridor-tightening ladder: a uniform quasiconformal self-map that (for fixed T) sends the precision-n target corridor into the precision- target corridor, with controlled dilatation (ideally ).

8.7.1. A QC Dilatation Formula for x–Only Level-Preserving Maps

Lemma 5 (Exact

K for

).

Let be absolutely continuous, strictly increasing, and satisfy for a.e. x. Define on a rectangle the map Then g is quasiconformal on R and its maximal dilatation is

In particular, if a.e., then .

Proof. Write

with

and

. Then

Hence

Therefore the Beltrami coefficient is real:

For

, the pointwise dilatation equals

Taking the essential supremum yields (

29). If

a.e., then

a.e., and since

on a set of positive measure in our explicit construction below,

. □

8.7.2. A Window Self-Map Tightening the Corridor (Ignoring Puncture Circles)

This first construction is a uniform window self-map. It is the cleanest successor map, but it does not preserve circular puncture boundaries (it sends circles to ellipses). It is therefore appropriate in an “outside-corridor obstacle control” regime.

Proposition 2 (Uniform window-tightening map with ). Fix and . For set Define by Let be .

Then:

- (i)

is a homeomorphism , fixes pointwise, and commutes with the symmetry ;

- (ii)

maps each target corridor exactly by

- (iii)

is quasiconformal with (hence ).

Proof. (i) The function is continuous, strictly increasing, and maps , , so it is a homeomorphism of . Since y is unchanged, is a homeomorphism of . The symmetry is immediate from the definition .

(ii) On the middle interval we have , so sends endpoints to and hence sends the open interval onto .

(iii) The derivative exists a.e. and is piecewise constant: it equals on the middle region and equals the outer slope Since in our construction of , we have and hence . Therefore a.e. Lemma 5 gives . □

8.7.3. A Punctured-Domain Self-Map Tightening the Corridor (Preserving Discs)

We now address the puncture-circle issue. Because the discs in sit at horizontal distance r from the critical line, the precision-n corridor is separated from the discs for all . This allows a tightening map that is identity on the discs, hence a genuine self-map of the punctured target domain.

Proposition 3 (Disc-preserving tightening map on for ). Fix and let . For define as above. Assume , so .

Define by where the transition slope is

Let be .

Then:

- (i)

is a homeomorphism of , fixes pointwise, and commutes with .

- (ii)

For every one has

- (iii)

fixes every target puncture disc pointwise; hence it restricts to a quasiconformal self-map

- (iv)

is quasiconformal with

Proof. (i) By construction is continuous and strictly increasing, and it maps and . Hence it is a homeomorphism of and is a homeomorphism of fixing pointwise.

(ii) If then and . On this x-interval, , so maps onto and y is unchanged. This is exactly .

(iii) In the removed discs are centered at and have radius r. Therefore every point of any such disc satisfies either (left disc) or (right disc). On these regions , so fixes each disc pointwise and hence preserves .

(iv) The derivative exists a.e. and is piecewise constant: Since implies , we have and thus Also because . Hence a.e. Lemma 5 gives . □

8.7.4. Why Tangency Forces a Base-Step Exception (and How to Avoid It)

Lemma 6 (Tangency obstruction at under fixed circular obstacles). Fix and suppose . Let and consider the base corridor , whose closure meets the left target disc at the tangency point .

There is no homeomorphism that extends continuously to , maps each boundary circle to itself, and satisfies

Proof. Assume such an F exists. Consider the sequence of points Then , where p lies on the boundary circle of the left puncture disc. Since F extends continuously to the closure and maps that boundary circle to itself, we have and lies on that same circle, hence Therefore for all sufficiently large k one has . But would force , a contradiction. □

Remark 16 (Two clean remedies). Lemma 6 pinpoints why the first tightening step is special when the target discs are fixed circles tangent to the base corridor boundary in closure.

There are two coherent ways forward:

- (a)

Weaken obstacle control:work in an “outside-corridor obstacle control” class where one does not require circle-to-circle matching on the target side. Then Proposition 2 provides a uniform successor map for all .

- (b)

Insert a buffer:redefine the base target corridors to be strictly inside , leaving a positive distance to every puncture circle. Then the disc-preserving construction of Proposition 3 works already at the base step.

Either choice avoids encoding an impossible object: instead of forcing a contradictory “ successor” inside the strict circle-preserving class, one changes semantics (as in your S0/S1/S3/S4 paradigm) by weakening constraints or regularizing geometry.

8.8. Successor Inequality for the Tightened Energies

Lemma 7 (Composition inequality for dilatation). If f and g are quasiconformal maps on planar domains for which is defined, then

Proof. This is standard: it follows from the chain rule for the Beltrami coefficient and the inequality , which yields the stated submultiplicativity of maximal dilatation. (Any standard quasiconformal text contains this.) □

Corollary 2 (Successor permission: for ). Fix and assume . For every one has

Proof. Fix . Let be the disc-preserving tightening map from Proposition 3, so and

Take any . Since , we have so . Moreover, fixes and fixes each target puncture circle pointwise, so composing does not break the boundary and puncture matching requirements.

By Lemma 7, Taking the infimum over yields Dividing by 2 gives the inequality for . □

Remark 17 (Smoothing). The maps above are piecewise affine in x (and hence quasiconformal). If one prefers a diffeomorphism, one may smooth near the finitely many breakpoints. This produces a smooth quasiconformal map with dilatation for any prescribed , without changing the corridor-inclusion conclusions.

9. A More Universal Generalization: The Extremal–Length Pinching Principle

9.1. What is Really Driving the Ladder: Modulus Cannot Collapse at Bounded K

The corridor-halving ladder is only one concrete instance of a much more general phenomenon. The underlying mechanism is the basic quasiconformal distortion law for extremal length (modulus): Thus, any deformation scheme that attempts to force a nontrivial curve family to have arbitrarily small modulus in the image must pay unbounded K. This is independent of the specific corridor geometry and independent of .

9.2. Universal Formulation in Terms of an Arbitrary Curve Family

Definition 14 (Pinching tasks and their energy). Let be domains, and let be a curve family in with .

For each parameter (interpreted as a “precision” or “pinching level”) let be a curve family in .

Let be a chosen admissible class of quasiconformal homeomorphisms (with any additional boundary or obstacle constraints you impose) such that Define the pinching energy by

Theorem 5 (Universal extremal–length lower bound).

In the setting of Definition 14, assume . Then every satisfies

If , then and .

Proof. Fix

and write

. By quasiconformal distortion,

Since

, monotonicity of modulus gives

Combining yields

which rearranges to (

31). Taking logarithms gives the pointwise bound

and then infimizing over

yields (

32).

If , then no nonconstant curve family can be contained in (equivalently, is too thin to carry curves of positive modulus). Since and modulus distortion cannot send positive modulus to zero at finite K, there is no admissible f; hence and by convention . □

Corollary 3 (Universal “no bounded distortion pinching to nothing”). If along some parameter sequence , then Equivalently: any scheme that forces the image modulus to go to 0 necessarily requires (infinite quasiconformal energy).

Remark 18 (This is the universal conclusion you can safely claim). The corridor-halving ladder is not special. It is simply a concrete way to make by shrinking corridor widths. The universal statement is: any attempt to collapse a nontrivial conformal modulus (extremal length) to 0 forces unbounded quasiconformal distortion. This is a rigidity theorem about quasiconformal geometry itself, independent of ξ and independent of RH.

9.3. Discrete Ladder Form: Arbitrary Shrink Factors and Linear Energy Growth

The previous statement becomes “Gödel-ladder-like” once we impose a canonical successor rule on the target modulus.

Definition 15 (Geometric successor rule (general factor)). Fix . A–tightening ladderis a sequence of target curve families , , such that

Corollary 4 (Linear lower bound in n). Assume the hypotheses of Theorem 5 and additionally that is a Λ–tightening ladder in the sense of Definition 15. Then and in particular linearly in n.

Proof. Insert

into (

32). □

Remark 19 (Normalization trick). If one prefers a unit increment , simply choose the successor rule so that . The corridor-halving choice corresponds to and yields increment .

9.4. How the –corridor ladder is a special case

Remark 20 (Specialization to the corridors). In the ξ construction, is the stacked family of vertical curves in the source corridors , while is the stacked family in the tightened target corridors . Since the corridor modulus is (width)/(height) and each level has fixed height 2, tightening the corridor width by tightens the modulus by . Thus the ξ setup is exactly the case of Corollary 4, and Theorem 4 is its explicit rectangle-modulus evaluation.

9.5. Teichmüller Interpretation (Optional)

Remark 21 (Teichmüller-space viewpoint (conceptual, not needed for proofs)). In classical Teichmüller theory, degenerations such as pinching a corridor to width 0 correspond to approaching the boundary of the relevant moduli/Teichmüller space. The universal modulus pinching principle above is the planar, finite-window manifestation of the general theme that such boundary limits occur only at infinite Teichmüller distance (equivalently, require ).

10. A Gödelian III+ Interpretation for RH

10.1. Precision as a Gödel-Style Successor Operation

Fix . Assume so that the corridor system is nontrivial. Let and let be the precision-n corridor-controlled class from Definition 12, with energy from Definition 13.

Definition 16 (Precision statements and the successor operator ). For each define the precision-n axis-landing statement to be Define the Gödel-style successor operator on these statements by i.e. “tighten the target corridor by a factor 2” (halve its width).

10.2. Budget Stages: A “Theory Ladder” of Allowable Distortions

Definition 17 (Distortion stages and Teichmüller permission energy). For define the budget-m class to be the collection of all K–quasiconformal maps in satisfying : For a statement define its permission energy by with .

10.3. Gödelian III+: Non-Closure Under Successor Precision

Define the (dimensionless) corridor ratio

Theorem 6 (Gödelian III+ Teichmüller incompleteness at fixed T). Fix with . Then:

- (i)

-

(Sharp lower bound = non-closure) For every and every , Equivalently,

In particular, is unbounded.

- (ii)

(Successor permission: one step up realizes the next tightening) For every and every , That is: if precision n is achievable with budget m, then precision is achievable with budget .

Proof. Proof of (i). Assume

. Then

. By Theorem 4, every

satisfies

Combining gives

, hence

, proving (

34).

Proof of (ii). Assume and choose . By Corollary 2, there exists a disc-preserving tightening map with such that Hence lies in and satisfies Thus . □

Remark 22 (Why this is genuinely Gödelian in structure). Theorem 6 is a geometric analogue of the Gödel/Turing progression phenomenon:

plays the role of a “permission statement” at precision level n;

plays the role of “next permission” (tighten by a factor 2);

budget classes play the role of finite stages of strength;

no fixed stage m realizes all successors , yet moving from m to permits the next step (up to the base-step tangency issue).

Thus the obstruction is not an outright contradiction; it is a non-closure statement: bounded distortion is not closed under iterated successor tightening.

10.4. The “III+” Aspect: Two Independent Noncompact Directions

Remark 23 (Gödelian III+ = height growth plus precision growth). There are two independent “go to infinity” directions in the ξ corridor framework:

- (a)

Precision : corridor width , so exact axis landing corresponds to a pinching/degeneration limit, forcing infinite Teichmüller energy.

- (b)

Height :

as the window expands, more levels may become active and the corridor data (including and the collection ) evolves. Any “global” deformation scheme must control both directions simultaneously.

This two-parameter noncompactness is what we call the Gödelian “III+” aspect: it is stronger than a single one-parameter ladder because the deformation problem can fail by divergence in either (or both) directions.

10.5. Interpretation for RH (No Overclaim)

Remark 24 (What this says about RH, and what it does not). Theorem 6 does not prove RH and does not establish any formal independence statement about RH. Its content is geometric and conditional on the chosen corridor-controlled class.

However, it does give a rigorous obstruction to a broad class of deformation-based RH narratives:

If one tries to “force” axis landing (collapse to the critical line) by a single bounded-distortion quasiconformal deformation while maintaining corridor control at arbitrarily fine precision, then this is impossible: each additional digit of landing precision costs a definite amount of energy, and exact axis landing lies at infinite energy.

Thus any approach to RH that implicitly assumes a bounded-K corridor-controlled collapse mechanism at all scales must either (i) abandon bounded distortion, (ii) relax corridor control, or (iii) accept an infinite ladder of finite-stage quantitative problems rather than a single terminal bounded-distortion construction.

Lemma 8 (Cardinality of the admissible class at fixed ). Fix and . Then is either empty or has cardinality continuum:

Proof.

Upper bound. Every is quasiconformal, hence continuous on the separable metric space . Fix a countable dense subset (e.g. ). A continuous map is determined uniquely by its restriction to D, hence

Lower bound (if nonempty). Assume and choose . Choose a small Euclidean disk disjoint from: (i) all source corridors , (ii) all puncture disks removed in , and (iii) a neighborhood of .

There exist continuum many distinct quasiconformal homeomorphisms () such that each is the identity on (e.g. by integrating a one-parameter family of compactly supported smooth vector fields in U). Then each composition lies again in , since is the identity on all constrained sets. Moreover is injective, so .

Combining the bounds yields whenever nonempty. □

11. Three Universal Conclusions (Logic, Geometry, RH Strategies)

11.1. Universal in Logic: Countability of Consistent Effective Proof Narratives

We formalize “proof narratives” as finite proof objects in effective axiom systems. This is a meta statement about syntax (not about truth of RH).

Definition 18 (Effective theory and formal proof narrative). Fix a countable first-order language (e.g. arithmetic or set theory). Aneffective–theory is one whose axioms form a recursively enumerable set.

A formal proof object is a finite string over a finite alphabet encoding a derivation in a fixed proof calculus (Hilbert, natural deduction, sequent calculus, etc.).

A formal proof narrative is a triple where is an effective –theory, φ is an –sentence, and π is a –proof of φ in the chosen proof calculus.

Theorem 7 (Countability of consistent effective proof narratives). Let be the class of all formal proof narratives such that is aconsistenteffective theory in the fixed countable language . Then is countable.

Equivalently: the class of all consistent effective proof narratives is of cardinality .

Proof. There are countably many Turing machines, hence countably many recursively enumerable axiom sets, hence countably many effective theories in . There are countably many –sentences (finite strings in a countable alphabet). There are countably many finite proof strings .

Hence the set of all triples is a subset of a countable product of countable sets, therefore countable. The consistent ones form a subset, hence are also countable. □

Remark 25 (What this does not say). Theorem 7 does not imply that RH is undecidable or unprovable. Countably many narratives can prove statements about uncountable structures, because proofs are not enumerations: they use universal arguments and quantifiers.

11.2. A Definability Bottleneck (“Nameability” is Countable)

The countability of narratives has a genuine consequence: only countably many individual points in an uncountable geometric space can be uniquely singled out by effective narratives (without importing non-effective parameters).

Definition 19 (Effectively nameable points in an uncountable space). Let X be a set (e.g. a Teichmüller space) and suppose we have a fixed way to speak about X inside a background theory (e.g. X is definable in , or in second-order arithmetic).

Call a point effectively nameable if there exists a consistent effective theory and a formula such that:

- 1.

(there exists a unique u satisfying Φ), and

- 2.

in the intended semantics, that unique u equals x.

Leteffdenote the set of effectively nameable points of X.

Theorem 8 (Definability bottleneck). If X is any set and eff is defined as in Definition 19, then eff is countable.

In particular, if (e.g. X is an uncountable Teichmüller space), then is nonempty (indeed uncountable).

Proof. There are only countably many pairs where is an effective theory and is a formula: each is encoded by a finite string. Each such pair can name at most one point of X (because gives uniqueness). Therefore eff is a countable union of singletons, hence countable. □

Remark 26 (How this interacts with “ lives in an uncountable Teichmüller space”). If an object attached to χ is canonically defined by an explicit construction, it can be effectively nameable even though the ambient space is uncountable (analogous to ). The bottleneck only rules out proof narratives that require selecting a non-canonical generic point of an uncountable space by finite description.

11.3. Universal in Geometry: The Modulus Pinching (Infinite-Energy) Theorem

We now give the cleanest universal geometric conclusion: pinching positive modulus to zero modulus forces infinite quasiconformal energy. Emptiness is encoded as .

Definition 20 (Modulus-pinching scheme and energy). Let be domains, let be a curve family in with .

Let be curve families in . For each n, let be a class of quasiconformal homeomorphisms (with any additional constraints you want) such that Define the energy

Theorem 9 (Universal modulus pinching forces infinite energy).

In the setting of Definition 20, assume . Then every satisfies

hence If , then and .

Consequently, if as , then .

Proof. Fix

and set

. Quasiconformal modulus distortion gives

Since

, monotonicity gives

Combining yields

hence (

35). Infimizing over

f gives the energy bound.

If , then the combined inequalities would force , contradicting . Hence no such f exists, i.e. , and by convention . □

Remark 27 (“Nothingness” is represented by emptiness and , not contradiction). The conclusion is not a paradox. It is a clean geometric statement: the requested constraints cannot be simultaneously met. We encode this failure as in the extended real line.

11.4. Universal in RH Strategies: Which Families are Affected

We now formalize the maximal honest claim one can make about “RH proof narratives”: our obstruction applies exactly to those whose decisive step reduces to bounded-distortion modulus pinching.

Definition 21 (Bounded-distortion modulus-pinching RH strategy (formal obstruction class)). Call an RH strategyof QC pinching typeif it asserts (explicitly or implicitly) the existence of:

a curve family of positive modulus inside some source domain naturally associated to the critical strip, ξ, or a windowed punctured model thereof, and

a sequence of target families whose modulus tends to 0 as , and

a uniform constant and quasiconformal maps with such that for all n.

Theorem 10 (Universal obstruction to QC pinching type RH narratives). No QC pinching type RH strategy (Definition 21) can be correct as stated: if and , then any such sequence must satisfy (equivalently ).

Proof. This is an immediate specialization of Theorem 9: □

Remark 28 (Strategy taxonomy: which broad families are affected?). Theorem 10 is ageometricobstruction. It applies precisely to RH narratives whose core mechanism is a bounded-distortion quasiconformalpinching(corridor collapse, exact axis landing with all-scale corridor control, etc.).

It does not directly constrain RH approaches whose main steps are not of modulus-pinching type, e.g.:

- (a)

Analytic explicit-formula / prime-sum methods:approaches built from the explicit formula, zero density estimates, moments, mollifiers, or classical complex analysis do not (in general) require bounded-QC pinching.

- (b)

Trace formula / automorphic spectral methods:Selberg/Arthur trace formula approaches are spectral/representation-theoretic; again, unless one introduces an explicit bounded-QC pinching step, the pinching obstruction is irrelevant.

- (c)

Random matrix heuristics:these are probabilistic heuristics rather than proofs; the obstruction is not aimed at them. If one attempts to convert such heuristics into a literal bounded-distortion pinching deformation, then it becomes subject to Theorem 10.

- (d)

Deformation/Teichmüller approaches:any strategy that literally tries to move “off-critical features” to the critical line by a single bounded-distortion deformation while maintaining modulus/corridor control at arbitrarily fine scales falls squarely under the obstruction.

This classification makes no claim about which non-pinching strategy might succeed; it only isolates a large and geometrically natural subclass that cannot succeed under bounded distortion.

12. Universal Conclusions: Logic, Geometry, and RH Strategy Barriers

12.1. Universal in Logic: Countability of Consistent Effective Proof Narratives

Definition 22 (Effective theory and formal proof object). Fix a countable first-order language (e.g. arithmetic or set theory) and a fixed proof calculus. Aneffective–theory is one whose axiom set is recursively enumerable. Aformal proof objectis a finite string encoding a derivation in the fixed calculus.

Definition 23 (Consistent effective proof narrative). Aconsistent effective proof narrativeis a triple where is aconsistenteffective –theory, φ is an –sentence, and π is a –proof of φ. Let denote the class of all such triples.

Theorem 11 (Universal countability of consistent effective narratives). The class is countable.

Proof. There are countably many Turing machines, hence countably many recursively enumerable axiom sets, hence countably many effective theories . There are countably many formulas in a countable language. There are countably many finite proof strings . Therefore the class of triples is a subset of a countable product of countable sets, hence countable; restricting to consistent preserves countability. □

Remark 29 (No contradiction from uncountable mathematical objects). Theorem 11 does not imply RH is unprovable. Countably many narratives can prove theorems that quantify over uncountable sets (e.g. “is uncountable”) because proofs are not enumerations.

12.2. Universal in Geometry: Modulus Pinching Forces Infinite Quasiconformal Energy

Definition 24 (Modulus pinching task and energy). Let be domains and let be a curve family in with . Let be curve families in .

For each , let be a class of quasiconformal homeomorphisms satisfying together with any additional boundary/obstacle constraints one wants.

Define the energy

Theorem 12 (Universal extremal-length obstruction). In the setting of Definition 24 assume . Then every satisfies and hence If , then and .

Consequently, if as , then .

Proof. Fix and set . Quasiconformal modulus distortion gives Since , monotonicity gives Combine and rearrange. If , no finite K can satisfy the inequality, hence and by convention. □

Remark 30 (“Nothingness” without contradiction). The statement is not a paradox; it simply says the requested constraints cannot be simultaneously realized. We encode this as in .

12.3. Universal in RH Strategies: What is Ruled Out, What is Not

Definition 25 (QC modulus-pinching RH narrative class). Call an RH narrative QC modulus-pinching type if it reduces RH to the existence of a uniform and maps satisfying a modulus-pinching task in the sense that:

- 1.

there is a source curve family of positive modulus;

- 2.

there are target families with ; and

- 3.

there exist quasiconformal maps with and for all n.

Theorem 13 (Universal obstruction to bounded-distortion pinching narratives). No QC modulus-pinching type RH narrative (Definition 25) can be correct as stated. Indeed, if and , then any realizing sequence must satisfy (equivalently ).

Proof. Immediate from Theorem 12. □

Remark 31 (Taxonomy: which broad RH strategy families are affected?). Theorem 13 rules out only those RH narratives whose decisive step isbounded-distortionQC pinching to modulus 0 (e.g. exact axis landing with corridor control at all scales).

It does not rule out in general:

Explicit formula / prime sum analytic strategies

(unless they entail a bounded-distortion modulus collapse step),

Trace formula / automorphic spectral strategies

(same caveat),

Random matrix heuristics

(not formal proofs).

Thus to “rule out” those families one must add additional, precise restrictions on what information or operations the strategy is allowed to use.

12.4. Finite-Resolution Barrier: No Finite Truncation can Decide RH

We now give a universal black-box barrier that legitimately constrains truncated explicit-formula / truncated trace-formula styles: any method that uses only finitely many constraints cannot exclude off-critical zeros within a large symmetry class.

12.4.1. Axiomatic Class of –Like Entire Functions

Definition 26 (–like symmetry class). Let be the class of entire functions satisfying the two symmetries (These are exactly the functional-equation and real-axis symmetries enjoyed by .)

12.4.2. Finite Constraint Data (Captures “Finite Truncations”)

Definition 27 (Finite jet constraints). Fix a finite set S that is closed under and , and fix an integer . Afinite jet constraintconsists of prescribing complex numbers interpreted as desired values for .

Theorem 14 (Finite-constraint indistinguishability (“mock ” theorem)). Let and let be the finite jet data given by Let be any point with such that and and . Then there exists such that:

- (i)

for all and (it matches all prescribed finite data);

- (ii)

(hence F violates RH in the sense “has an off-critical zero”).

Proof.

Step 1: build a symmetric holomorphic bump vanishing to order on S. Since S is finite, choose a polynomial P with real coefficients that vanishes to order at every point of S. (Concretely, take , where is a choice of one point from each nonreal conjugate pair.)

Define Then Q is entire, satisfies , and has real coefficients, hence also satisfies . Moreover Q vanishes to order at least at every , so for all and .

Step 2: force a zero at by choosing a scalar multiple. By construction because and . Set Then F is entire and lies in because both and Q satisfy the same symmetries. Also .

Finally, for each and each , since . This proves (i) and (ii). □

Corollary 5 (No finite truncation principle can decide RH inside ). Let be any property of that depends only on finitely many jet values . Then cannot logically imply “all zeros of F satisfy ” within .

In particular, any RH strategy whose decisive step uses only finitely many constraints of this kind cannot be a complete proof: it cannot exclude off-critical zeros without bringing in additional, genuinely uniform (infinite-parameter) information.

Proof. Apply Theorem 14 to produce matching all finite data of while having an off-critical zero. Thus no property depending only on that finite data can distinguish the two with respect to RH. □

Remark 32 (How this “rules out” truncated explicit/trace formula arguments (and why it cannot rule out the full frameworks)). Theorem 14 is a black-box barrier: if a purported RH proof only consults ξ through a finite interface (finitely many sampled values/derivatives, finitely many numerically verified constraints, finitely many truncated identities), then there exist ξ–like counterexamples indistinguishable by that interface yet violating RH.

This does not rule out explicit-formula or trace-formula approaches in full generality, because those frameworks can employ uniform statements quantified over infinite families of test functions (not finite interfaces). What it does rule out is the idea that a fixed finite truncation of those frameworks is decisive.

13. Resolution-Parameter Barrier Theorems (Explicit/Trace Truncations)

13.1. The –symmetry class (“-like” entire functions)

Definition 28 (–symmetry class). Let denote the class of entire functions satisfying: We call such F–like(or–symmetric).

Remark 33. lies in . The class is closed under addition and under multiplication by real scalars.

13.2. What “Resolution Cutoff A” (or L) Can Mean

There is no unique canonical choice; different truncated explicit-formula and trace-formula narratives correspond to different finite sets of exact constraints at a given cutoff.

To cover all of them at once we model “resolution-A information” as any finite list of linear observables extracted from F at that cutoff.

Definition 29 (Resolution-A interfaces (abstract model)). Fix a parameter (or ) called aresolution cutoff. Let be any chosen collection of real-linear functionals interpreted as “observables available at cutoff A”.

A finite resolution-A interface is a finite list together with the vector of exact measured values where We say that isindistinguishable from at interface if for all k.

Remark 34 (Examples of one sees in practice).

(Explicit-formula truncation model.) One may take to be generated by finitely many band-limited kernels ϕ with via linear statistics such as or otherlinearfiltered measurements arising in a truncated analytic pipeline.

-

(Trace-formula truncation model.) One may take to consist of finitely many spectral linear statistics of the form where h ranges over a finite list of test functions. In a “ξ-shadow” model, these observables become linear functionals on the ξ-attached object being measured.

The theorem below does not depend on which concrete model is chosen; it only usesfinitenessof the interface at fixed cutoff.

13.3. A Universal “Mock at Fixed Resolution” Theorem

Lemma 9 (An infinite-dimensional -symmetric polynomial subspace). Let Then is an infinite-dimensional real vector space.

Proof. For each define . The set is linearly independent over (compare leading terms), hence is infinite-dimensional. □

Theorem 15 (Resolution-parameter barrier / “mock ” at fixed cutoff). Fix a resolution cutoff (or ), and fix any finite resolution-A interface .

Then there exists a function such that:

- (i)

(Indistinguishable at cutoff A) for every ,

- (ii)

(Violates RH in the strongest possible way) F has a zero at some real point , hence F has an off-critical zero in the critical strip.

Consequently, no argument that uses only the finite interface Λ at the fixed cutoff can logically certify RHwithin the symmetry class : the same cutoff data is compatible with both “RH-like” and “non-RH-like” behavior.

Proof.

Step 1: find a nonzero -symmetric perturbation invisible to the interface. Restrict each to the infinite-dimensional space . Consider the linear map Since is infinite-dimensional and N is finite-dimensional, the map L cannot be injective. Hence contains some nonzero , so

Step 2: choose an off-critical real point not vanishing on Q. Because Q is a nonzero polynomial, it has only finitely many real zeros. Choose any such that .

Step 3: force a zero at while preserving the interface data. Since is real and , both and are real. Define the real scalar Then because is closed under addition and real scalar multiplication. Moreover, so F has an off-critical zero in .

Finally, for each k, since . This proves (i) and (ii). □

13.4. Gödelian Ladder Corollary: Fixed Cutoff Cannot be Terminal

Corollary 6 (Fixed cutoff A (or L) cannot be a terminal decision stage). Let be any proof pipeline (“truncated explicit formula”, “truncated trace formula”, or any other method) whoseentire exact input from at cutoff Ais a finite interface .

Then cannot certify RH from that fixed cutoff alone, in the following precise sense: there exists that is indistinguishable from ξ at that cutoff interface yet violates RH. Therefore, any such narrative must either:

- (a)

let the cutoff parameter grow without bound ( or ), producing a Gödelian-style ladder parameter, and/or

- (b)

incorporate additional non-interface structure that is not captured by the finite resolution-A observables (for example, rigid arithmetic structure beyond the symmetry class ).

Proof. Apply Theorem 15 to the finite interface . □

Remark 35 (What this does and does not rule out). Theorem 15 and Corollary 6 rule out fixed finite truncations as logically terminal arguments within the broad symmetry class .

They do not rule out full explicit-formula or full trace-formula approaches in general, because those frameworks may use uniform information that is not equivalent to a finite interface at fixed cutoff.

14. A Provable Bridge: Bounded-Distortion Geometric Implementations of Trace Methods Force

14.1. Axiomatizing What It Means to “Geometrize” a Trace/Localization Method

Definition 30 (Geometric implementation at resolution L). Let be a resolution/localization parameter (e.g. a spectral cutoff, bandwidth, or height-scale). A >geometric implementation at resolution L consists of:

- 1.

domains ;

- 2.

a curve family in with

- 3.

a target curve family in ;

- 4.

a quasiconformal homeomorphism satisfying the inclusion constraint

Definition 31 (Modulus collapse). We say the implementation collapses modulus if

14.2. The Universal Extremal-Length Bound (the Key Lemma)

Lemma 10 (Modulus distortion yields a quantitative lower bound for

K).

Assume is a –quasiconformal map implementing . If , then

If , then no such exists.

Proof. Since

is

–quasiconformal,

Because

, monotonicity gives

Combine:

If

, rearrange to obtain (

36). If

, the inequality forces

, contradiction. □

14.3. The Main Conditional Theorem (this Is the pRovable Bridge Conclusion)

Theorem 16 (Any bounded-distortion geometric implementation of modulus collapse forces ). Assume we have a geometric implementation at resolution L in the sense of Definition 30. Assume further that:

- (a)

the source modulus is uniformly bounded below:

- (b)

the implementation collapses modulus (Definition 31):

Then the dilatations necessarily diverge: In particular, there is no uniform bound for all L.

Moreover, one has the quantitative estimate

Proof. By Lemma 10,

Since

, the right-hand side tends to

, hence

. Taking logarithms yields (

37). □

Corollary 7 (Typical growth rates). Under the hypotheses of Theorem 16:

- 1.

If for some , then .

- 2.

If for some , then .

Remark 36 (This theorem is unconditional and strategy-agnostic). Theorem 16 is a theorem of quasiconformal geometry alone: it applies to any narrative—automorphic/trace-formula, explicit-formula, geometric, or otherwise—ifthat narrative is implemented by a bounded-distortion modulus-collapse deformation.

14.4. The Missing Universal Reduction (Bridge Thesis)

Conjecture 1 (Automorphic-to-Teichmüller Bridge Thesis for (not proved)). Any automorphic/trace-formula proof narrative of the Riemann Hypothesis for ζ necessarily yields, either explicitly or implicitly, a geometric implementation (Definition 30) whose target modulus collapses to 0 (Definition 31) while keeping the source modulus bounded below.

Remark 37.

Conjecture 1 is a strong meta-claim aboutallautomorphic proofs. It is not currently established and should be viewed as a research program statement rather than a theorem.

Corollary 8 (Bridge Thesis ⇒ no bounded-distortion automorphic modulus-collapse proof). Assuming Conjecture 1, any automorphic/trace narrative that attempts to carry out the modulus collapse with a uniform bound is impossible. Indeed, any such implementation must satisfy .

Proof. Assuming the Bridge Thesis supplies a modulus-collapsing geometric implementation, the conclusion follows from Theorem 16. □

15. Resolution-Parameter Barrier Theorems (Finite Truncations)

15.1. The –symmetry class

Definition 32 (–symmetry class). Let be the class of entire functions satisfying

Remark 38. The completed Riemann function belongs to .

15.2. A Concrete Model of “Resolution Cutoff A”: Bandlimited Probes

Definition 33 (Bandlimited test functions at resolution A). Fix . Let be the set of Schwartz functions whose Fourier transform is supported in .

Definition 34 (Finite bandlimited interface). Fix and choose finitely many test functions . Define linear observables (when the integrals converge) by We say that F isindistinguishable from at resolution A through the interface if for all k.

Remark 39 (Convergence). For ξ the integrals converge absolutely because decays exponentially in . In the theorem below we perturb ξ by entire functions with rapid decay on the critical line, so the same convergence holds for F.

15.3. Resolution-A Barrier: Indistinguishable Counterexamples Exist at Every Fixed A

Lemma 11 (Infinite-dimensional rapidly decaying –symmetric perturbations). Define Then and . Let Then is an infinite-dimensional real vector space, and every satisfies for some m, hence is integrable for every .

Proof. Invariance: , so . Also because the coefficients are real. Thus .

For , the map is injective over, so is infinite-dimensional. On the critical line, , and polynomial growth times is integrable against any Schwartz function. □

Theorem 17 (Resolution-parameter barrier at fixed A (finite bandlimited probes)). Fix and a finite interface as in Definition 34. Then there exists such that:

- (i)

(Indistinguishable at resolution A) for all ;

- (ii)

(Violates RH) F has a real off-critical zero: there exists with .

Therefore, no proof method whose only exact input from ξ at cutoff A is the finite set can certify RH even within the symmetry class .

Proof. Let be the infinite-dimensional space from Lemma 11. Define the linear map Since is infinite-dimensional and N is finite-dimensional, contains a nonzero element . Thus for all k.

Because Q is entire and not identically zero, its real zeros are discrete. Choose such that and also (possible since zeros are discrete). Since is real and , both and are real. Define Then and , so F violates RH.

Finally, for each k, since . This proves (i) and (ii). □

Corollary 9 (Gödelian ladder consequence: fixed A cannot be terminal). Any RH narrative whose decisive stage uses only finitely many bandlimited probes at a fixed cutoff A cannot be logically terminal (within ). To become decisive, such a narrative must either:

- (a)

send (a resolution ladder parameter), and/or

- (b)

use additional structure that excludes the mock counterexamples (e.g. arithmetic/Euler product information not encoded in ).

Proof. Immediate from Theorem 17. □

Remark 40 (What this does and does not rule out). Theorem 17 rules out fixed finite truncations of explicit-formula style arguments: finitely many test functions at bounded bandlimit.

It does not rule out a full explicit-formula proof that uses a uniform statement quantified over all test functions in (or over all A), because that is not a finite interface.

15.4. Abstract Trace-Cutoff Barrier (Finite Spectral Interfaces)

Definition 35 (Resolution-L interface (abstract)). Fix . Let be any chosen set of complex-linear functionals interpreted as “observables available at trace cutoff L”. Afinite trace interface at cutoff Lis a finite list .

Theorem 18 (Resolution-L barrier (finite trace interfaces)). Fix and a finite trace interface . Assume each is defined on the infinite-dimensional subspace from Lemma 11.

Then there exists such that:

- (i)

for all ;

- (ii)

F has an off-critical zero .

Hence no fixed-L finite-interface trace narrative can be terminal (within ).

Proof. Repeat the proof of Theorem 17 with the functionals in place of the bandlimited integrals. The only needed input is that the map has nontrivial kernel on the infinite-dimensional space . □

Remark 41 (Relation to actual trace formula strategies). A full trace formula identity is not a finite interface: it is quantified over a large class of test functions. Theorem 18 rules out only arguments that at some stage collapse to finitely many linear statistics at bounded cutoff.

16. Resolution-to-Tightening Meta Theorems Specialized to the Corridors

16.1. Fixed-T Corridor Data

Fix and assume . Write and recall the source and tightened target corridors: for and . Let denote the precision-n corridor-controlled class (as in Definition (Precision-n corridor-controlled class) in the main text).

Define the dimensionless corridor ratio

16.2. Resolution Ladders: Abstractly Packaging What a Trace/Localization Scheme Would Need

Definition 36 (Resolution-indexed geometricization datum). Let be a resolution parameter (e.g. spectral cutoff, bandwidth, or any localization scale). A resolution-indexed geometricization at fixed T consists of:

a function (the “tightening level extracted at resolution L”), and

a family of quasiconformal maps with

No existence of such is assumed a priori; it is a hypothesis expressing that the strategy has been geometrized into corridor tightenings.

16.3. Energy Bound Along a Resolution Ladder (Purely Geometric Consequence)

Theorem 19 (Resolution ⇒ tightening ⇒ energy).

Assume a resolution-indexed geometricization datum exists in the sense of Definition 36. Then for every one has the sharp lower bound

In particular:

- (i)

If as , then as .

- (ii)

If , then is bounded:

Proof. For each

L, we have

by hypothesis. Applying the

–tightening lower bound (Theorem (

–tightening lower bound)) with

yields exactly (

39).

Item (i) is immediate from (

39). Item (ii) follows by rearranging

. □

16.4. Successor Permission and the “ per Tightening Step” Rule

The following shows that each additional tightening step is achievable by multiplying K by 2 (up to the base-step tangency issue discussed earlier). This is the geometric analogue of a “next-permission upgrade”.

Theorem 20 (Successor permission: tightening by one step costs at most energy (for )). Assume and fix . If and , then there exists such that

Proof. Let be the disc-preserving target tightening map from the earlier construction (with and for all j). Set and define . Then sends into , hence lies in . Submultiplicativity of dilatation gives . □

16.5. Infinite Splitting of Hypotheses: The Ladder Logic as a Meta Theorem

Definition 37 (Precision-permission assertions). For each define the precision-permission assertion at fixed T: (Equivalently: “the strategy reaches corridor precision m at some resolution stage.”)

Theorem 21 (Meta theorem: infinite permission splitting forces infinite energy). Assume there is a resolution-indexed geometricization with associated (Definition 36). Suppose the strategy asserts arbitrarily high precision , i.e. Then necessarily Equivalently: the set of bounded-distortion realizers is eventually empty at high precision: for every there exists m such that no f with can lie in .

Proof. Fix . Choose m large enough so that . By hypothesis, pick L with . Then by Theorem 19, Since was arbitrary, . □

Remark 42 (Why this is “the same principle” as the permission-energy ladder). Theorem 21 is the geometric analogue of a Gödelian “no finite closure under successor permissions” statement:

In the arithmetic ladder, one splits into infinitely many next-consistency permissions and proves that no finite stage proves them all.

Here one splits into infinitely many precision permissions “achieve corridor tightening level m”, and Theorem 21 shows no bounded distortion cap can realize them all.

Nothing contradictory is asserted: failure is represented as emptiness of the bounded-K admissible class and equivalently as energy .

16.6. A Quantitative Tradeoff: Allowable Growth of Bounds Attainable

Corollary 10 (If grows slowly, then grows slowly). Assume a resolution-indexed geometricization exists and suppose there is an explicit bound for some function . Then for all one has In particular:

- 1.

If for some , then .

- 2.

If , then necessarily for some (exponential distortion growth).

Proof. Rearrange from Theorem 19. □

Remark 43 (What this does and does not claim about trace/automorphic methods). These results do not prove that trace-formula resolution forcescorridor tightening . That step is exactly the missing bridge from spectral localization to geometric pinching.

What the theorems do say, unconditionally, is:

If a trace/automorphic strategy is geometrized into corridor tightening at level , then the distortion energy must scale at least like . Thus any attempt to extract arbitrarily fine axis-landing precision from increasing spectral resolution produces an infinite ladder of increasingly strong hypotheses, and it forces infinite energy.

17. Automorphic Resolution Ladders as a Gödelian-Style Permission Energy

17.1. Philosophy (Kept Mathematical)

Many automorphic/trace-formula arguments are resolution-parametrized: one introduces a cutoff/bandwidth/localization scale and proves a family of finite-resolution statements, whose conjunction is intended to force a global conclusion. This is an infinite splitting phenomenon analogous in structure to a permission ladder: each increase in L demands new information/estimates.

The goal of this section is to state a clean meta-theorem showing that, in a wide class of trace-formula situations, there is an intrinsic unbounded permission energy associated to the cutoff ladder. The theorem does not rule out automorphic proofs; it isolates an unavoidable ladder structure whenever one insists on controlling certain positive geometric statistics uniformly in L.

17.2. Abstract Trace Schema: A Positive Geometric Mass at Cutoff L

Definition 38 (Length spectrum data). A length spectrum datum consists of:

a countable set (“geometric objects”: prime powers, closed geodesics, moduli, ...),

a length function , and

nonnegative weights .

The associated positive discrete measure on is

Definition 39 (Resolution cutoff and geometric mass). For define thetruncated geometric massby

Remark 44 (Why this captures “trace/explicit formula truncations”). In the Weil explicit formula and in trace formulas (Selberg, Kuznetsov, Arthur), choosing a test function whose transform is supported in a length window typically produces a geometric side supported only on objects with length . The quantity is the simplest positive statistic that must grow as L grows, because more objects become visible.

17.3. A Gödelian Ladder: Successor and “Permission Energy”

Definition 40 (Dyadic resolution ladder and successor operator). Fix a base cutoff and define the dyadic ladder Define thesuccessor operator on cutoffs by .

Definition 41 (Automorphic permission energy of controlling the geometric mass). Define the(base-2) permission energyof the cutoff L by with the convention . Equivalently, when .

Remark 45 (Nothingness without contradiction). If then ; this encodes “no finite budget bounds the mass”. This is not a paradox; it is an unboundedness statement.

17.4. Automorphic Gödelian Ladder Theorem (Unconditional)

Theorem 22 (Automorphic ladder meta-theorem: monotonicity and non-closure). Let be any length spectrum datum and let and be as above. Then:

- (i)

(Monotonicity) is nondecreasing in L, hence is nondecreasing:

- (ii)

(Non-closure / unbounded permission energy) If as , then as . Equivalently: for every finite budget level there exists L such that .

- (iii)

(Successor step costs at least one unit whenever the mass at least doubles) If for some L one has , then In particular, if for all , then along the dyadic ladder ,

Proof. (i) is immediate since increasing L only enlarges the index set .

(ii) If , then for each m choose L with . Then by definition, . Hence .

(iii) If , then Taking ceilings yields . Iterating gives the dyadic ladder bound. □

Remark 46 (Interpretation). Theorem 22 is a Gödelian-style non-closure under successor permissions statement: if your method requires controlling (or even just bookkeeping) an increasing positive geometric mass , then no finite budget remains adequate at all resolutions . This is a structural splitting phenomenon, not a claim about provability of RH.

17.5. Model 1: the Weil Explicit Formula for Yields an Exponential Mass Ladder

We now show that in the case there is a canonical positive mass that grows exponentially in the length cutoff L.

Definition 42 (-prime-power mass). Let with length and weight , where Λ is the von Mangoldt function. Then

Lemma 12 (Growth of from the prime number theorem). One has In particular, and satisfies

Proof. Let . The prime number theorem gives . By partial summation, Insert : Hence . Set to obtain . Taking gives . □

Corollary 11 ( has a sharp resolution ladder). For L large enough one has , hence In particular along one has for all large n.

Proof. From Lemma 12, , so . Thus for all sufficiently large L. Apply Theorem 22(iii). □

Remark 47 (What this means for explicit-formula strategies). Even before any deep analysis, the prime-power side exhibits an intrinsic resolution splitting: at cutoff L you are handling a positive mass of size . Any approach that attempts to control such positive contributions uniformly at bounded “budget” must fail; budgets must grow, producing an infinite ladder of finite stages. This does not rule out explicit-formula proofs of RH; it says the method is inherently laddered in resolution.

17.6. Model 2: Selberg trace formula yields a geodesic-length ladder

We record the analogous ladder phenomenon for Selberg’s trace formula on compact hyperbolic surfaces, using the prime geodesic theorem (unconditional in that setting).

Definition 43 (Geodesic mass model (schematic)). Let be a compact hyperbolic surface. Let be the set of primitive closed geodesics γ on X and let denote its length. Define a positive weight model Define the truncated mass

Proposition 4 (Exponential growth of (prime geodesic input)). For a compact hyperbolic surface X, one has as and in fact Consequently the corresponding permission energy diverges.

Proof. Let denote the number of primitive closed geodesics of length . The prime geodesic theorem gives . Then By , we have for large L, hence and in particular (a slightly weaker but simpler bound). Thus and . □

Remark 48 (Kuznetsov and general automorphic settings). Kuznetsov-type formulas and higher-rank trace formulas also exhibit resolution ladders: tight spectral localization forces involvement of larger geometric ranges (moduli c, orbital integrals, etc.). Making a completely uniform quantitative ladder statement requires specifying the positivity/weight model and the cutoff-to-range mapping in the chosen formula. The abstract Theorem 22 applies whenever one can identify a positive truncated mass that grows with L.

17.7. Connection Back to Teichmüller Modulus Energy (Conditional Bridge)

Remark 49 (How this interfaces with the Teichmüller corridor tightening ladder). If a given automorphic/trace-formula narrative can be geometrized so that increasing resolution L forces an increase in corridor tightening level in the ξ–corridor model, then the Teichmüller lower bounds show , while the automorphic ladder shows the resolution bookkeeping mass (or analytic budget) is unbounded in L.

Thus one obtains a genuine “III+” splitting: a resolution ladder and a geometric tightening ladder , each carrying an unbounded energy. Proving the explicit link is an additional bridge hypothesis, not a consequence of trace formulas alone.

18. Gödelian III+ Ladder Meta-Theorem (Successor + Energy + Infinite Splitting)

18.1. Axiomatizing a “Gödelian III+” Ladder

Definition 44 (Ladder datum). Aladder datumconsists of:

- 1.

a nonempty index set I (“stages”) equipped with a successor map ;

- 2.

for each stage , a set ofrealizers(possibly empty);

- 3.

for each , a cost functional .

Define the energy at stage i by

Definition 45 (Successor upgrade operator). A ladder datum admits asuccessor upgradewith cost at most if for each there exists a map (not necessarily unique) such that

Definition 46 (Obstruction increment). A ladder datum has obstruction increment at least if for all one has

18.2. The Meta-Theorem: Infinite Splitting Forces Unbounded Energy

Theorem 23 (Gödelian III+ ladder principle). Let be a ladder datum.

- (A)

(Lower growth from obstruction) If the obstruction increment satisfies Definition 46 with some , then for every and every , In particular as .

- (B)

(Upper growth from successor upgrades) If successor upgrades exist with cost at most Δ (Definition 45) and , then for every and every there exists a realizer with

- (C)

(Infinite splitting = no bounded closure) Assume(A)with . Then there is no finite budget such that contains a realizer of cost for all n. Equivalently, the conjunction of all successor-stage permissions fails for every finite M.

Proof. (A) Apply the increment inequality inductively: .

(B) Let satisfy . Define . Then repeated use of the upgrade bound gives .

(C) If such an M existed, then for all n, contradicting (A). □

Remark 50 (No contradiction is encoded). If some stage has , then by definition. This represents impossibility as emptiness and infinite energy, not as an inconsistency.

19. Gödelian III+ Ladder Meta-Theorem (Successor + Energy + Infinite Splitting)

19.1. Axiomatizing a “Gödelian III+” ladder

Definition 47 (Ladder datum). A ladder datum consists of:

- 1.

a nonempty index set I (“stages”) equipped with a successor map ;

- 2.

for each stage , a set ofrealizers(possibly empty);

- 3.

for each , a cost functional .

Define theenergyat stage i by

Definition 48 (Successor upgrade operator). A ladder datum admits asuccessor upgradewith cost at most if for each there exists a map (not necessarily unique) such that

Definition 49 (Obstruction increment). A ladder datum hasobstruction incrementat least if for all one has

19.2. The Meta-Theorem: Infinite Splitting Forces Unbounded Energy

Theorem 24 (Gödelian III+ ladder principle). Let be a ladder datum.

- (A)

(Lower growth from obstruction) If the obstruction increment satisfies Definition 46 with some , then for every and every , In particular as .

- (B)

(Upper growth from successor upgrades) If successor upgrades exist with cost at most Δ (Definition 45) and , then for every and every there exists a realizer with

- (C)

(Infinite splitting = no bounded closure) Assume(A)with . Then there is no finite budget such that contains a realizer of cost for all n. Equivalently, the conjunction of all successor-stage permissions fails for every finite M.

Proof. (A) Apply the increment inequality inductively: .

(B) Let satisfy . Define . Then repeated use of the upgrade bound gives .