Submitted:

09 January 2026

Posted:

12 January 2026

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

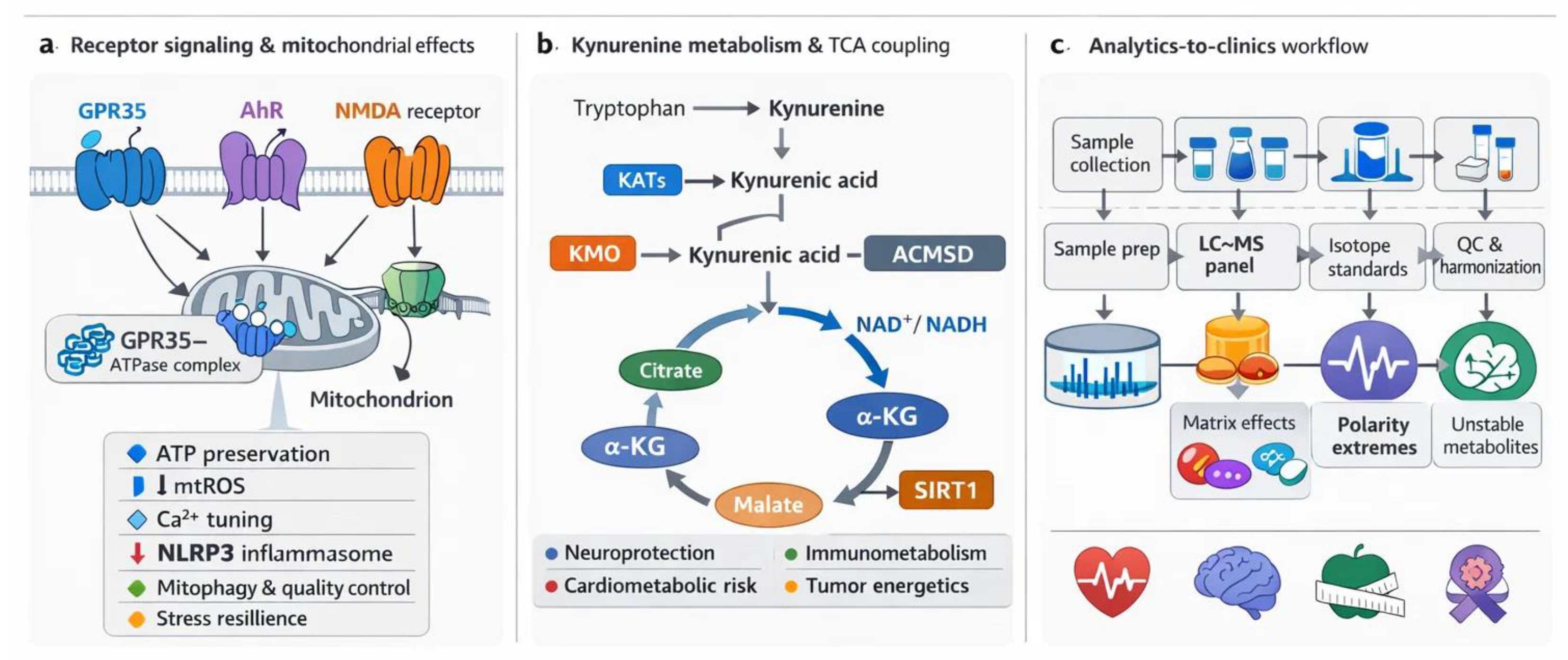

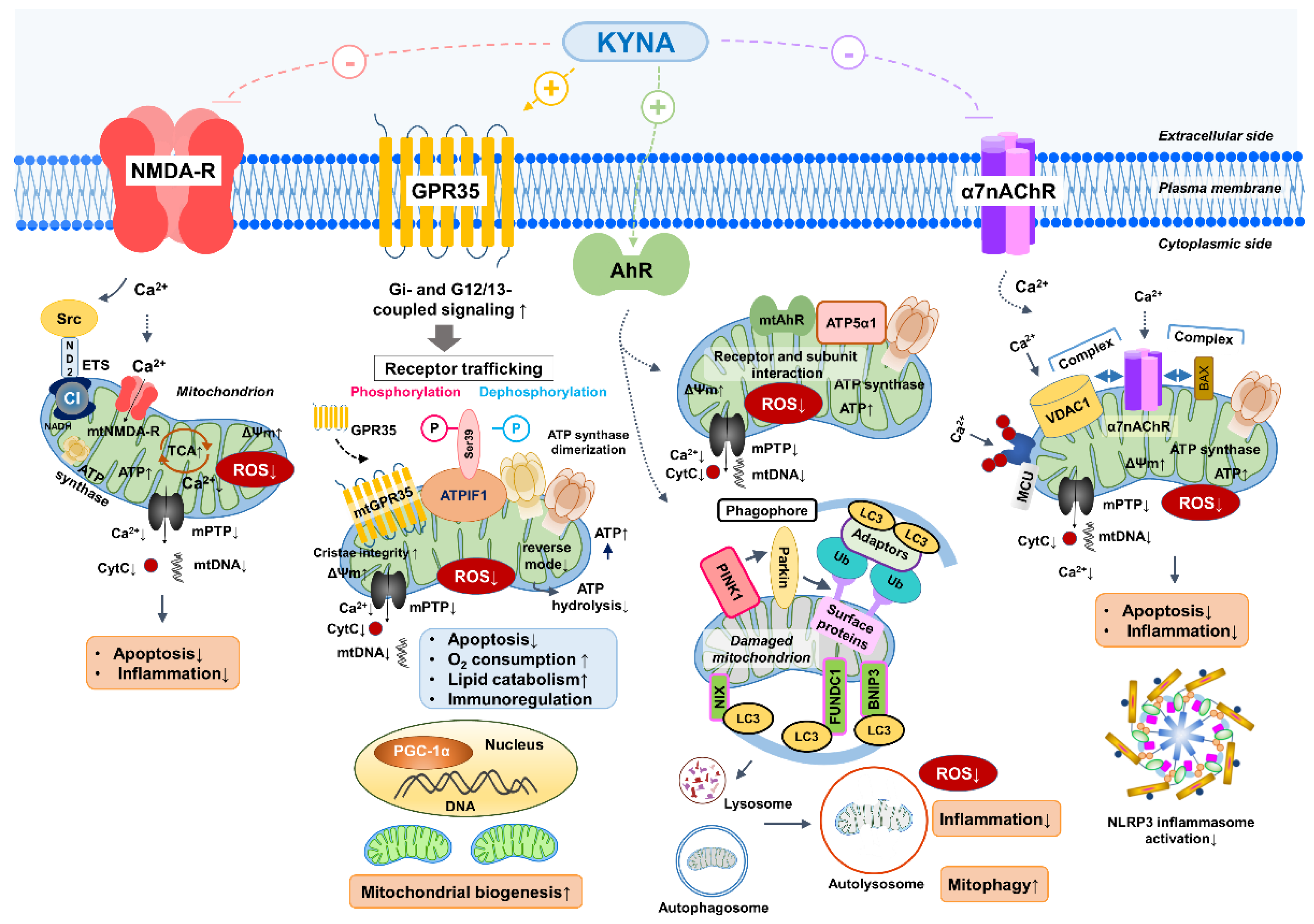

2. Receptor-Mediated Mitochondrial Regulation by Kynurenic Acid (KYNA)

2.1. KYNA and GPR35: Energy Homeostasis and Ischemic Protection

2.2. KYNA and Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor (AhR): Mitophagy and Organelle Quality Control (QC)

2.3. Kynurenic Acid (KYNA) and N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) Receptors: Calcium Regulation and Excitotoxicity

2.4. Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors (α7nAChR-like)

2.5. Other Potential KYNA-Sensitive Sites

| Target | Mitochondrial effects | Animal model/Cell type | Key findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPR35 | -ATP preservation -ATP turnover ↑ -Mitochondrial oxidative capacity ↑ -ROS production ↓ -mPTP opening inhibition -Calpain-1/2 activity ↓ |

Myocardial ischemia/reperfusion (rat, NMVMs) Myocardial ischemia/reperfusion (mouse, heart tissue) C57BL/6J mice, adipose tissue |

-KYNA–GPR35 activation stabilizes ATP synthase, maintains ΔΨm, prevents ATP hydrolysis, limits ROS and apoptosis -GPR35 blockade reduces calpain-mediated proteolysis, preserves mitochondrial integrity, and mitigates oxidative stress -KYNA–GPR35 axis enhances PGC-1α expression, promotes mitochondrial biogenesis, increases O2 consumption, and initiate anti inflammatory cytokine production |

[16,22,92,108,121,216] |

| mt GPR35 |

-ATP synthase dimerization -ATP preservation via the inhibition of ATP hydrolysis |

GPR35 knoclout mice and neonaatal cardiomyocytes | -Binds to ATPIF1 and associates with the mitochondrial outer membrane -Inhibits mitochondrial adenylate cyclase and thereby PKA -Allows ATPIF1 to promote ATP synthase dimerization and prevent ATP hydrolysis |

[22,121] |

| AhR | -Mitophagy (BNIP/PINK1–Parkin) ↑ -ROS production ↓ -ATP preservation -Oxidative metabolism ↑ |

Hepatocytes, AML12 cells, IPEC-J2 cells, AhR knockout mice, primary hepaocytes |

-KYNA and KYN activate AhR to induce PINK1 and BNIP3 expression, promoting mitophagy and preserving mitochondrial respiration under stress -Loss of AhR impairs mitochondrial quality control and increases ROS accumulation, disrupting energy metabolism |

[139,156,168,221,222] |

| mtAhR | -ATP synthase regulation -Fine-tuning ROS production |

Mitochondrial fraction, liver cells | -Mitochondrial AhR interacts with ATP5α1; its localization and activity depend on ligand status, possibly influencing ATP synthesis and redox balance | [221] |

| NMDA-R | -Ca2+ influx ↓ -mPTP opening ↓ -Cytochrome c release ↓ -Bcl-XL expression ↑ -Apoptosis ↓ -Complex I coupling |

Neurons, Microglia, neuronal cultures |

-KYNA blocks NMDA-R at the glycine site, limits Ca2+ overload, prevents mPTP opening, and protects against apoptosis -Potential crosstalk with complex I regulates bioenergetics |

[193,197] |

| mt NMDA-R | -Ca2+ flux modulation -Fine-tuning ROS production |

Rat heart mitochondria | -NR1/NR2B subunits detected in mitochondria; -Regulation of ROS production and Ca2+ level under hypoxia/ischemia |

[194] |

| α7nAChR | -Regulates Ca2+ flux, ROS production, and cytochrome c release via interaction with VDAC1 -Influences mPTP opening and OXPHOS activity through kinase signaling (PI3K/Akt, CaM, Src). -Limits apoptosis through the regulation of Bcl-2/Bcl-xL and caspases. |

Isolated mouse liver mitochondria; U373 human glioblastoma astrocytoma cells KAT II knockout (KAT II−/−) mice |

-α7nAChR–VDAC1 and α7nAChR–Bax complexes identified; receptor inhibition (methyllycaconitine) suppresses cytochrome c release; stimulation (PNU 282987) enhances it; acetylcholine reduces ROS. -Decreased KYNA levels increase α7nAChR activity; α7nAChR activation linked to neuroprotection and anti-apoptotic signaling; KYNA may physiologically regulate the receptor |

[37,211,213,223,224] |

| mitoKATP channels (?) | -Channel opening reduces mitochondrial Ca2+ overload, delays mPTP opening, and supports cellular survival during ischemic or oxidative stress; -Its function is modulated by GPR35 and ROS signaling |

In vivo ischemia–reperfusion models: cardiac and neuronal mitochondria |

-Diazoxide (mitoKATP opener) confers neuro- and cardioprotection; inhibition (5-hydroxydecanoate) abolishes protective effects; -ROS and GPR35 signaling may crosstalk to regulate mitoKATP and mPTP. |

[214,215,216] |

| Complex I / Complex III redox sites (?) | -Redox-sensitive cysteine residues regulate ROS generation (superoxide, H2O2); transient ROS acts as signaling for stress adaptation; -KYNAmay scavenge radicals and preserves electron transport. |

Isolated mitochondria; C. elegans | -KYNA may reduce ROS at Complex I and III independent of receptor mechanisms; mild Complex I ROS prolongs lifespan in C. elegans; antioxidant effects support mitochondrial stability. | [217,218,219,220] |

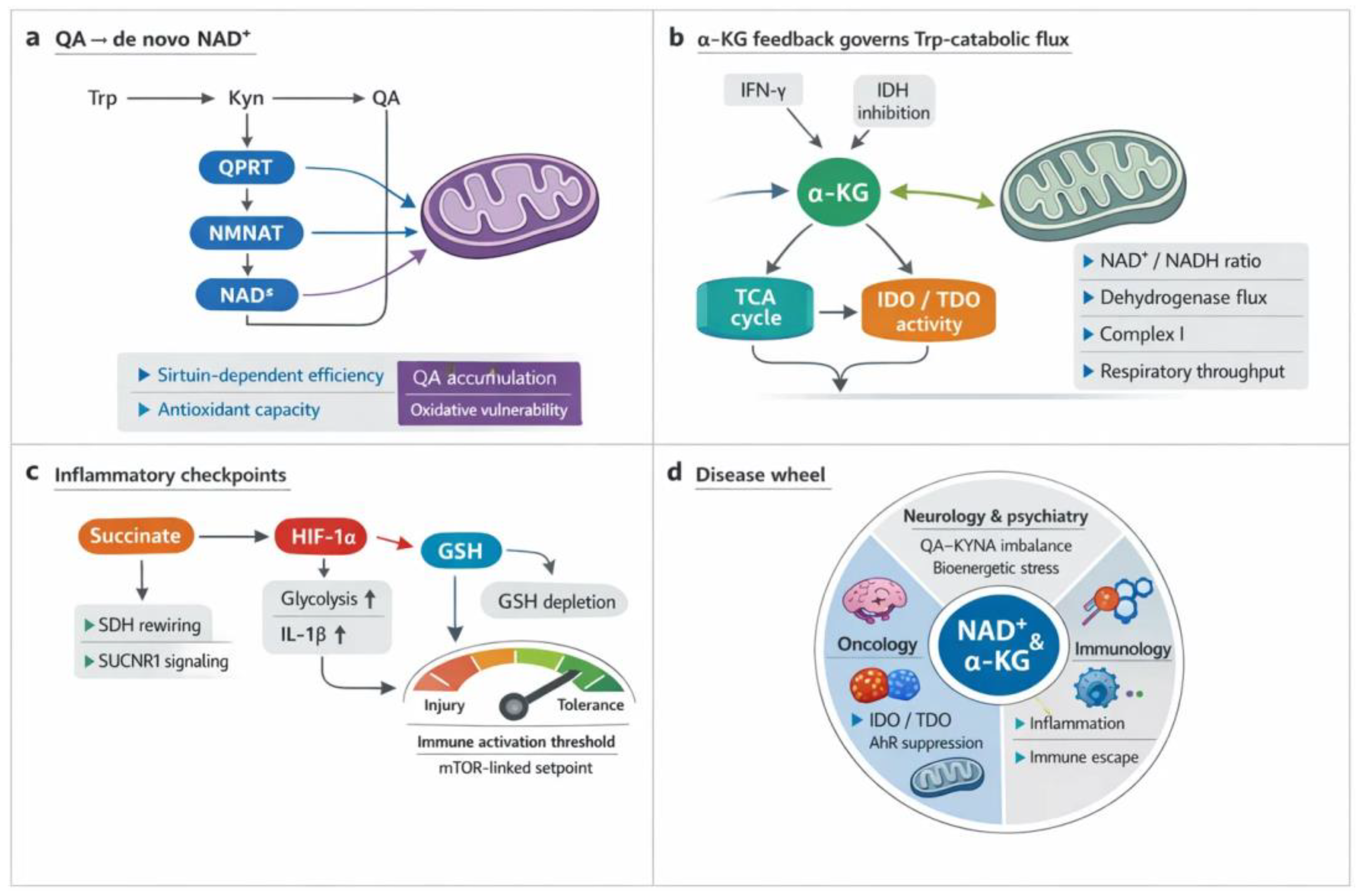

3. Crosstalk Between the Kynurenine (KYN) Metabolism and the TCA Cycle

3.1. Shared Metabolic Intermediates and Redox Balance

| Node (e.g., QA → NAD+) | Enzymes/regulators | Directionality | Impact on NAD+/NADH or anaplerosis | Immune/ROS consequence | Evidence class | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QA → NAD+ | QPRT → NMNAT → NADS; modulation by aging/inflammation | KYN → NAD+ biogenesis → ETC | Increases cellular/matrix NAD(H); sustains complex I oxidation and O2 consumption | Supports macrophage respiration; QPRT loss ↓NAD+, ↑injury/ROS; neuroinflammation requires conversion for SIRT activity | Mechanistic (cells/animals), clinical/genetic | [14,42,225] |

| KYNA → GPR35 → mitochondrial nodes (incl. MAS) | KATs (KYNA production), GPR35; MAS components | KYNs ligands → receptor → mitochondria/TCA | Tunes ETC throughput and shuttle-coupled redox set-points | Sets immune tone; receptor-proximal control of inflammatory signaling | Mechanistic receptor signaling | [16,22,114] |

| IDO1/TDO2 rate-setting → α-KG availability | IDO1, TDO2; IFN, hypoxia, nutrient status | Immune cues → KYNs flux → TCA carbon | Pulls carbon from Trp; constrains or supports α-KG–linked anaplerosis | Biases tolerance vs activation; conditions efficacy of IDOs/TDO blockade | Multi-omic/tumor-inflammation frameworks | [26,226,227] |

| MCART1-mediated NAD+ import (cytosol → matrix) | MCART1 (SLC25 family) | Cytosol → mitochondria | Maintains matrix NAD+ for dehydrogenases; prevents collapse of OXPHOS | Preserves respiratory control; supports T-cell effector programs | Mechanistic (transport/respiration) | [228,229,230] |

| MDH2 → oxaloacetate restraint of Complex II | MDH2; OAA | TCA intermediate → ETC modulation | Re-routes electron flow; dynamically resets NAD+/NADH coupling | Shapes graded ROS signaling downstream of ratio | Mechanistic ETC control | [217,218,231] |

| NNT couples NADH ↔ NADPH demand | Nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase (NNT) | Matrix redox coupling | Balances NADH oxidation with NADPH generation; stabilizes redox poise | Supports antioxidant defenses; buffers ROS during substrate shifts | Mechanistic redox coupling; | [232,233,234] |

| ME1 (malic enzyme-1): malate → pyruvate (NADPH) | ME1 | Cytosol anaplerosis ↔ redox | Raises NADPH; protects glutathione/NADPH buffering | Reinforces antioxidant capacity; feeds redox-encoded signaling | Mechanistic redox metabolism | [235,236] |

| Serine catabolism → NADH accumulation when respiration stalls | One-carbon/serine axis | Amino acid metabolism → redox | Builds cytosolic/mitochondrial NADH when ETC is limited; throttles biosynthesis | Constrains proliferative programs under low respiration | Mechanistic metabolic control | [2,9,237] |

| SDH lesion → alternative aspartate synthesis (matrix NAD+/NADH-dependent) | SDH/Complex II context; aspartate pathways | ETC defect → rerouted biosynthesis | Forces aspartate generation routes that depend on matrix NAD+/NADH | Salvages growth despite impaired cycling | Mechanistic pathology | [238,239,240] |

| De novo NAD+ from KYNs supports macrophage respiration | QPRT→NMNAT→NADS; macrophage programs | KYNs → NAD+ → OXPHOS | Expands NAD(H) pool; sustains respiratory control across tissues | Coordinates systemic redox communication; tunes inflammatory effectors | Mechanistic + systems | [14,42,241] |

| Type I IFN → IDH inhibition → citrate/α-KG ratio shift | IDH1/IDH2; Type I IFN | Immune signal → TCA wiring → KYNs context | Alters NADPH generation/redox milieu that licenses IDOs/TDO activity | Reprograms Trp catabolism vs defense state | Mechanistic immunometabolism | [26,219,231] |

| M1 macrophage “IDH break” → α-KG drop | IDH node; network integration | Polarization cue → TCA fragmentation | ↓Anaplerosis; altered NADPH; redox favoring effector programs and IDOs induction | Heightened inflammatory activation | Network/multi-omic | [231,242] |

| Sirtuin activity sustained by quinolinate-derived NAD+ | SIRTs; QPRT/NMNAT/NADS | KYNs → NAD+ → sirtuin deacylases | Preserves mitochondrial protein deacylation and efficiency | Supports neuronal viability; mitigates inflammatory stress | Mechanistic neuroinflammation | [14,25,243] |

| Ischemia–reperfusion diversion away from quinolinate | Pathway branch choice; NAD+ augmentation | Stress → KYN branch → NAD+ | NAD+ depletion when diverted; restoration rescues antioxidant capacity | Less oxidative injury with NAD+ repletion | Mechanistic/therapeutic modulation | [22,31,43] |

| UMPS bypass completing NAD+ synthesis when canonical steps fail | UMPS (bypass), salvage enzymes | Engineered/alternative route → NAD+ | Raises total NAD(H) when QPRT or steps are compromised | Enhances ETC throughput in designed systems | Engineering proof-of-principle | [244,245,246] |

| Quinolinate/NAM rise tracks mitochondrial work/biogenesis | Systemic KYNs NAD+ salvage | Workload/biogenesis → KYNs output | Correlated elevation of circulating quinolinate & nicotinamide with ETC demand | Links tissue respiratory programs to systemic KYNs tone | Integrative physiology; | [243,247,248] |

| Ubiquinol (CoQH2) oxidation requirement beyond NAD+ regeneration | ETC Complex III/CoQ cycle | ETC constraint → metabolic outcome | NAD+ repletion alone insufficient if CoQ oxidation is limited | Governs tumor growth constraints; bioenergetic bottleneck | Mechanistic tumor bioenergetics | [85,217,218] |

| LKB1 programs & thioredoxin circuits sculpt NADH turnover | LKB1, TRX/thioredoxin | Kinase/antioxidant systems → NADH flux | Adjusts NADH oxidation and chromatin-linked NAD+ usage | Sets T-cell effector capacity | Mechanistic immune control | [249,250,251] |

3.2. Immunometabolic Integration

3.3. Pathological Implications

| Indication (neurodegeneration/psychiatry/oncology) | Metabolite signature KYNA, QA, KYN, 3-hydroxykynurenine) | Mitochondrial phenotype | Clinical/functional readouts | Study type/size | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neurodegeneration | KYNA ↓, QA ↑; KYN context-dependent; 3-HK not primary in text | NMDA-driven ROS; depressed respiratory capacity; feed-forward bioenergetic failure and inflammation | Higher QA:KYNA ratios track tau/amyloid burden, neuronal dysfunction, faster progression | Clinical & biomarker studies; aging/disease cohorts; preclinical mechanistic work | [51,52,78] |

| Neurodegeneration (therapeutic angle) | Shift flux away from QA; raise KYNA (e.g., KMO modulation) | Mitochondrial stabilization; restored antioxidant defenses (incl. Nrf2 signaling) | Slower neurodegeneration trajectory; reduced excitotoxic stress | Preclinical + translational strategy proposals; early-phase targeting concepts | [3,8,205] |

| Psychiatry | Trp ↓, KYN ↓ (cohorts/meta-analyses); QA favored under immune activation; KYNA/KYN/QA show state-dependent oscillations; 3-HK not emphasized | Immune-bioenergetic coupling; mitochondrial/synaptic function shifts; serotonin depression when KYN metabolism is upshifted | Mood, psychosis, cognitive deficits; moderate blood–brain metabolite concordance indexing symptom burden/progression | Meta-analyses and multi-cohort studies; biomarker cohorts; mechanistic frameworks | [54,73,257] |

| Psychiatry (therapeutic angle) | Enzyme/flux control targeting; microbiome-sensitive modulators | Rebalancing KYNs–TCA redox and neurotransmission coupling | Symptom modulation and progression tracking via peripheral KYNs panels | Translational strategies; trial-readout integration (sizes vary) | [49,50,61] |

| Oncology (tumor immune escape) | KYN ↑ via IDO1/TDO2 → AhR activation; downstream KMO/KYNU shape invasive traits; KYNA/QA context-specific | Bioenergetic rewiring supporting growth; TME-conditioned redox | Treg expansion, CD8+ exhaustion; metastatic behavior, stromal crosstalk, chemoresistance | Clinical experience with IDOs/TDO blockade; preclinical tumor models; biomarker studies | [226,227,258] |

| Oncology (combination therapy) | KYN depletion (KYNU depots); AhR attenuation (e.g., small molecules) | Reprogrammed mitochondrial/immune metabolism; macrophage repolarization (e.g., GPX4–KYNU axis) | Synergy with PD-1 blockade; dismantling suppressive niches; overcoming resistance | Preclinical synergy studies; early translational combinations; emerging clinical strategies | [72,226,241] |

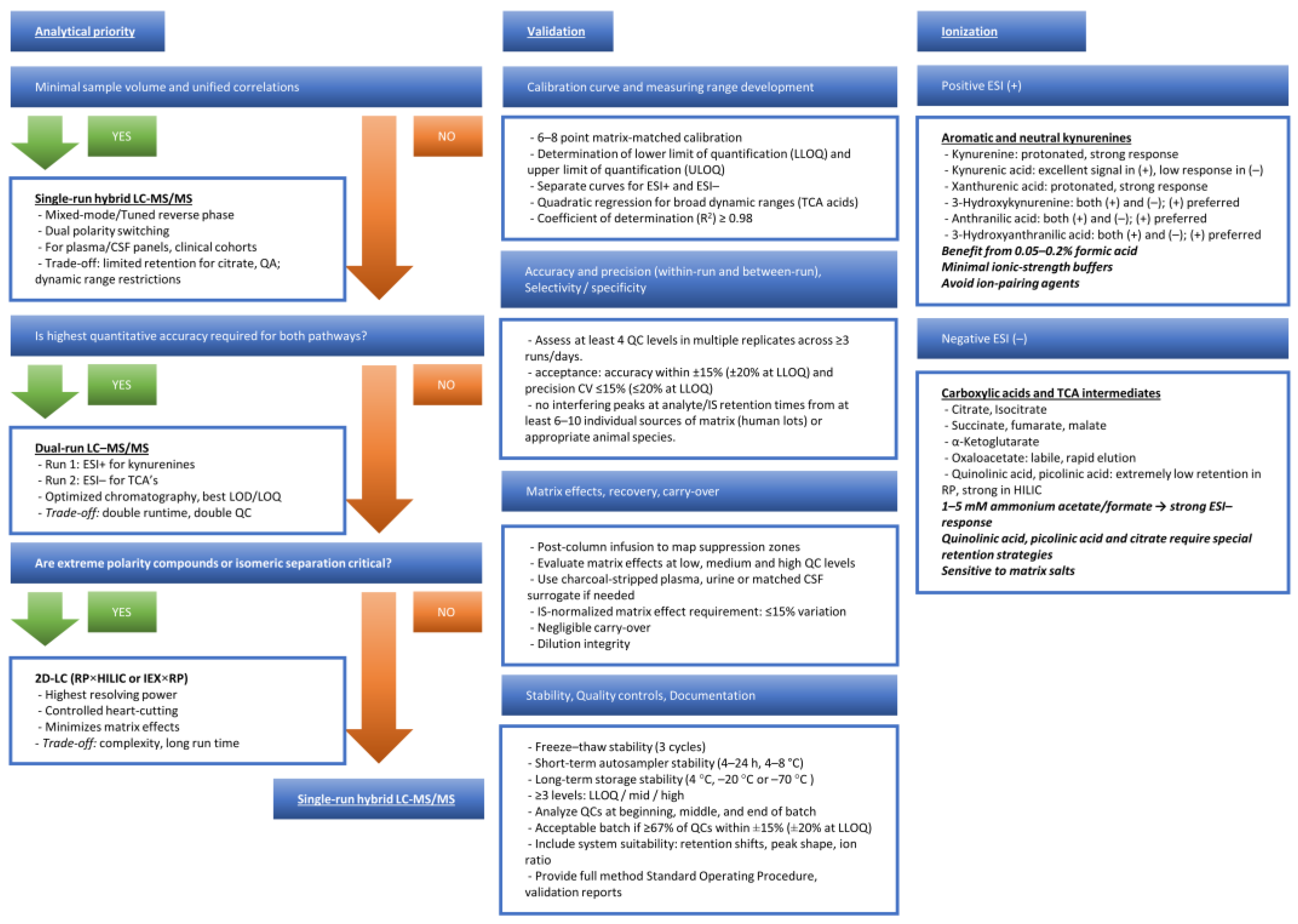

4. Analytical Strategies for Simultaneous Quantification

4.1. Rationale for Unified Measurement

4.2. Chromatographic and Mass Spectrometric Challenges

4.3. Practical Solutions

4.4. Validation and Clinical Feasibility

| Parameter | Acceptance Threshold | Notes / Mitigations | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calibration model | R2 ≥ 0.98; Back-calculated concentrations within ±15% (±20% at LLOQ) | Use matrix-matched standards; weighted (1/x or 1/x2) regression for wide dynamic ranges; verify linearity and curvature. | [477] |

| Linearity / Dynamic range | At least 6–8 calibration levels; deviation ≤15% (≤20% at LLOQ) | For TCA acids with steep response, consider quadratic fit; re-optimize injection volume to avoid saturation. | [478] |

| LLOQ / ULOQ | Signal ≥5× noise; precision ≤20%; accuracy 80–120% | Confirm LLOQ in actual matrix (plasma/CSF). Check for ion suppression at LLOQ. | [479] |

| Carryover | <20% of LLOQ signal and <5% of IS signal in blank after highest standard | Insert strong wash; consider needle wash with ACN/MeOH/water + 0.1% FA; extend gradient reequilibration. | [480] |

| Matrix effect (ME) | IS-normalized ME CV ≤15% across ≥6 donors | Perform post-column infusion; evaluate ME at low/mid/high QC; use isotopologues matched by polarity and retention. | [446,480,481] |

| Extraction recovery | 80–120% with CV ≤15% | Compare pre-spike vs post-spike; optimize precipitation solvent and pH; avoid ion-pairing agents in precipitant. | [446,482] |

| Precision—intra-day (repeatability) | CV ≤15% (≤20% at LLOQ) | Analyze ≥5 replicates each QC level; monitor retention shifts and ion ratio stability. | [479] |

| Precision—inter-day (reproducibility) | CV ≤15% | Include replicate QCs on ≥3 days; reinject archived QCs to detect long-term drift. | [478] |

| Accuracy | 85–115% (80–120% at LLOQ) | Compare to spiked reference material; evaluate both absolute and IS-normalized values. | [477] |

| Short-term autosampler stability | ≤15% change over 4–24 h at 4–8 °C | KYNs TCAs, may degrade—use immediate analysis or stabilizing additives. | [483] |

| Freeze–thaw stability | ≤15% change after 3 cycles | Avoid repeated thawing; aliquot samples; confirm TCA acids stability separately. | [480] |

| Long-term stability (–70 °C) | ≤15% deviation | Validate ≥1–3 months | [484] |

| Processed sample stability | ≤15% after 6–12 h in autosampler | For unstable analytes use rapid acquisition. | [485] |

| System suitability | Retention time shift <0.2–0.3 min; IS area CV ≤10%; ion ratio within ±20% | Verify before each batch; monitor column pressure, peak shape, and polarity switching efficiency. | [486] |

| QC frequency per batch | ≥3 levels (LQC/MQC/HQC); QCs at start, every 10–15 samples, and end | Large cohorts: insert pooled QC every 10–12 injections. | [479] |

| Batch acceptance criteria | ≥67% of all QCs and ≥50% at each level must be within ±15% (±20% at LLOQ) | If failure: investigate ME shifts, IS suppression, column fouling, or calibration instability. | [478] |

| Inter-batch comparability | QC CV ≤15% across batches | Use pooled QC and IS-normalized drift correction. | [487] |

5. Discussion: Strengths, Limitations, and Future Perspectives

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| α7nAChR | Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors containing α7 subunits |

| AhR | aryl hydrocarbon receptor |

| AKT | protein kinase B |

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| ATP | adenosine triphosphate |

| ATPIF1 | ATP synthase inhibitory factor 1 |

| BNIP3 | BCL2 interacting protein 3 |

| cAMP | cyclic adenosine monophosphate |

| CD98 | cluster of differentiation 98 |

| CLSI | clinical and laboratory standards institute |

| COMETS | consortium of metabolomics studies |

| CSF | cerebrospinal fluid |

| ERK | extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

| FAIR | findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable |

| GPR35 | G protein–coupled receptor 35 |

| GPX4 | glutathione peroxidase 4 |

| HIF-1α | hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha |

| HILIC | hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography |

| HRMS | high-resolution mass spectrometry |

| IDO | indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase |

| IDO1 | indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 |

| IDO2 | indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 2 |

| KATs | kynurenine aminotransferases |

| KMO | kynurenine 3-monooxygenase |

| KYN | kynurenine |

| KYNA | kynurenic acid |

| KYNU | kynureninase |

| LC–MS | liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry |

| LLOQ | lower limit of quantitation |

| MCART1 | mitochondrial carrier transporting NAD+ |

| MDH2 | malate dehydrogenase 2 |

| mPTP | mitochondrial permeability transition pore |

| NAD+ | nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (oxidized form) |

| NADH | nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (reduced form) |

| NADPH | nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (reduced form) |

| NF-κB | nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated b cells |

| NMDA | N-methyl-D-aspartate |

| NMD-R | N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor |

| NRF1 | nuclear respiratory factor 1 |

| NRF2 | nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 |

| PD-1 | programmed cell death protein 1 |

| PI3K | phosphoinositide 3-kinase |

| QC | quality control |

| QA | quinolinic acid |

| Rho | ras homolog family protein |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| SAR | structure–activity relationship |

| SDH | succinate dehydrogenase |

| SOP | standard operating procedure |

| TCA | tricarboxylic acid |

| TDO | tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase |

| TMCS | translational metabolic cohort study |

| Trp | tryptophan |

| UHPLC | ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography |

References

- Liu, B.H.; Xu, C.Z.; Liu, Y.; Lu, Z.L.; Fu, T.L.; Li, G.R.; Deng, Y.; Luo, G.Q.; Ding, S.; Li, N.; et al. Mitochondrial quality control in human health and disease. Mil Med Res 2024, 11, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarty, R.P.; Chandel, N.S. Mitochondria as Signaling Organelles Control Mammalian Stem Cell Fate. Cell Stem Cell 2021, 28, 394–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esteras, N.; Abramov, A.Y. Nrf2 as a regulator of mitochondrial function: Energy metabolism and beyond. Free Radic Biol Med 2022, 189, 136–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, S.; Feng, J.; Wang, M.; Wufuer, R.; Liu, K.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y. Nrf1 is an indispensable redox-determining factor for mitochondrial homeostasis by integrating multi-hierarchical regulatory networks. Redox Biol 2022, 57, 102470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ježek, P.; Holendová, B.; Garlid, K.D.; Jabůrek, M. Mitochondrial Uncoupling Proteins: Subtle Regulators of Cellular Redox Signaling. Antioxid Redox Signal 2018, 29, 667–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echtay, K.S.; Roussel, D.; St-Pierre, J.; Jekabsons, M.B.; Cadenas, S.; Stuart, J.A.; Harper, J.A.; Roebuck, S.J.; Morrison, A.; Pickering, S.; et al. Superoxide activates mitochondrial uncoupling proteins. Nature 2002, 415, 96–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, K.; Chen, G.; Li, W.; Kepp, O.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, Q. Mitophagy, Mitochondrial Homeostasis, and Cell Fate. Front Cell Dev Biol 2020, 8, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Szatmári, I.; Vécsei, L. Quinoline Quest: Kynurenic Acid Strategies for Next-Generation Therapeutics via Rational Drug Design. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2025, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.Q.; Suda, T. Reactive Oxygen Species and Mitochondrial Homeostasis as Regulators of Stem Cell Fate and Function. Antioxid Redox Signal 2018, 29, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M. Neurogenesis and Neuroinflammation in Dialogue: Mapping Gaps, Modulating Microglia, Rewiring Aging. Cells 2026, 15, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, S.; Kusano, Y.; Okazaki, K.; Akaike, T.; Motohashi, H. NRF2 signalling in cytoprotection and metabolism. Br J Pharmacol 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryoo, I.G.; Kwak, M.K. Regulatory crosstalk between the oxidative stress-related transcription factor Nfe2l2/Nrf2 and mitochondria. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2018, 359, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhász, L.; Spisák, K.; Szolnoki, B.Z.; Nászai, A.; Szabó, Á.; Rutai, A.; Tallósy, S.P.; Szabó, A.; Toldi, J.; Tanaka, M.; et al. The Power Struggle: Kynurenine Pathway Enzyme Knockouts and Brain Mitochondrial Respiration. J Neurochem 2025, 169, e70075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Portuguez, R.; Sutphin, G.L. Kynurenine pathway, NAD(+) synthesis, and mitochondrial function: Targeting tryptophan metabolism to promote longevity and healthspan. Exp Gerontol 2020, 132, 110841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Esquivel, D.; Ramírez-Ortega, D.; Pineda, B.; Castro, N.; Ríos, C.; Pérez de la Cruz, V. Kynurenine pathway metabolites and enzymes involved in redox reactions. Neuropharmacology 2017, 112, 331–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agudelo, L.Z.; Ferreira, D.M.S.; Cervenka, I.; Bryzgalova, G.; Dadvar, S.; Jannig, P.R.; Pettersson-Klein, A.T.; Lakshmikanth, T.; Sustarsic, E.G.; Porsmyr-Palmertz, M.; et al. Kynurenic Acid and Gpr35 Regulate Adipose Tissue Energy Homeostasis and Inflammation. Cell Metab 2018, 27, 378–392.e375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhen, D.; Liu, J.; Zhang, X.D.; Song, Z. Kynurenic Acid Acts as a Signaling Molecule Regulating Energy Expenditure and Is Closely Associated With Metabolic Diseases. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2022, 13, 847611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Chapul, L.; Pérez de la Cruz, G.; Ramos Chávez, L.A.; Valencia León, J.F.; Torres Beltrán, J.; Estrada Camarena, E.; Carillo Mora, P.; Ramírez Ortega, D.; Baños Vázquez, J.U.; Martínez Nava, G.; et al. Characterization of Redox Environment and Tryptophan Catabolism through Kynurenine Pathway in Military Divers’ and Swimmers’ Serum Samples. Antioxidants (Basel) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidetti, P.; Amori, L.; Sapko, M.T.; Okuno, E.; Schwarcz, R. Mitochondrial aspartate aminotransferase: a third kynurenate-producing enzyme in the mammalian brain. J Neurochem 2007, 102, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyckelsma, V.L.; Lindkvist, W.; Venckunas, T.; Brazaitis, M.; Kamandulis, S.; Pääsuke, M.; Ereline, J.; Westerblad, H.; Andersson, D.C. Kynurenine aminotransferase isoforms display fiber-type specific expression in young and old human skeletal muscle. Exp Gerontol 2020, 134, 110880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szabó, Á.G.Z.; Spekker, E.; Martos, D.; Szűcs, M.; Fejes-Szabó, A.; Fehér, Á.; Takeda, K.; Ozaki, K.; Inoue, H.; et al. Behavioral Balance in Tryptophan Turmoil: Regional Metabolic Rewiring in Kynurenine Aminotransferase II Knockout Mice. Cells 2025, 2025, 1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyant, G.A.; Yu, W.; Doulamis, I.P.; Nomoto, R.S.; Saeed, M.Y.; Duignan, T.; McCully, J.D.; Kaelin, W.G., Jr. Mitochondrial remodeling and ischemic protection by G protein-coupled receptor 35 agonists. Science 2022, 377, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Wang, Y.; Li, L.; Liu, S.; Wang, C.; Yuan, Y.; Yang, G.; Chen, Y.; Cheng, J.; Lu, Y.; et al. Mitochondrial ROS promote mitochondrial dysfunction and inflammation in ischemic acute kidney injury by disrupting TFAM-mediated mtDNA maintenance. Theranostics 2021, 11, 1845–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Li, S.; Jiang, N.; Shao, X.; Zhang, M.; Jin, H.; Zhang, Z.; Shen, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, W.; et al. PINK1-parkin pathway of mitophagy protects against contrast-induced acute kidney injury via decreasing mitochondrial ROS and NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Redox Biol 2019, 26, 101254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braidy, N.; Liu, Y. NAD+ therapy in age-related degenerative disorders: A benefit/risk analysis. Exp Gerontol 2020, 132, 110831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, M.; Tóth, F.; Polyák, H.; Szabó, Á.; Mándi, Y.; Vécsei, L. Immune Influencers in Action: Metabolites and Enzymes of the Tryptophan-Kynurenine Metabolic Pathway. Biomedicines 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, M.; Battaglia, S. Dualistic Dynamics in Neuropsychiatry: From Monoaminergic Modulators to Multiscale Biomarker Maps. Biomedicines 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo Godoy, A.C.; Frota, F.F.; Araújo, L.P.; Valenti, V.E.; Pereira, E.; Detregiachi, C.R.P.; Galhardi, C.M.; Caracio, F.C.; Haber, R.S.A.; Fornari Laurindo, L.; et al. Neuroinflammation and Natural Antidepressants: Balancing Fire with Flora. Biomedicines 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbalho, S.M.; Laurindo, L.F.; de Oliveira Zanuso, B.; da Silva, R.M.S.; Gallerani Caglioni, L.; Nunes Junqueira de Moraes, V.B.F.; Fornari Laurindo, L.; Dogani Rodrigues, V.; da Silva Camarinha Oliveira, J.; Beluce, M.E.; et al. AdipoRon’s Impact on Alzheimer’s Disease-A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Szabó, Á.; Vécsei, L. Redefining Roles: A Paradigm Shift in Tryptophan-Kynurenine Metabolism for Innovative Clinical Applications. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gáspár, R.; Nógrádi-Halmi, D.; Demján, V.; Diószegi, P.; Igaz, N.; Vincze, A.; Pipicz, M.; Kiricsi, M.; Vécsei, L.; Csont, T. Kynurenic acid protects against ischemia/reperfusion injury by modulating apoptosis in cardiomyocytes. Apoptosis 2024, 29, 1483–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Xie, R.; He, H.; Xie, Q.; Zhao, X.; Kang, G.; Cheng, C.; Yin, W.; Cong, J.; Li, J.; et al. Kynurenic acid ameliorates NLRP3 inflammasome activation by blocking calcium mobilization via GPR35. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 1019365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Hu, M.; Zang, X.; Fan, Q.; Liu, Y.; Che, Y.; Guan, X.; Hou, Y.; Wang, G.; Hao, H. Kynurenic acid/GPR35 axis restricts NLRP3 inflammasome activation and exacerbates colitis in mice with social stress. Brain Behav Immun 2019, 79, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wirthgen, E.; Hoeflich, A.; Rebl, A.; Günther, J. Kynurenic Acid: The Janus-Faced Role of an Immunomodulatory Tryptophan Metabolite and Its Link to Pathological Conditions. Front Immunol 2017, 8, 1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grishanova, A.Y.; Perepechaeva, M.L. Kynurenic Acid/AhR Signaling at the Junction of Inflammation and Cardiovascular Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, T.W.; Stoy, N.; Darlington, L.G. An expanding range of targets for kynurenine metabolites of tryptophan. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2013, 34, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, T.W. Does kynurenic acid act on nicotinic receptors? An assessment of the evidence. J Neurochem 2020, 152, 627–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oka, S.; Ota, R.; Shima, M.; Yamashita, A.; Sugiura, T. GPR35 is a novel lysophosphatidic acid receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2010, 395, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, H.; Hu, H.; Fang, Y. Multiple tyrosine metabolites are GPR35 agonists. Sci Rep 2012, 2, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badawy, A.A. Kynurenine Pathway of Tryptophan Metabolism: Regulatory and Functional Aspects. Int J Tryptophan Res 2017, 10, 1178646917691938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sas, K.; Szabó, E.; Vécsei, L. Mitochondria, Oxidative Stress and the Kynurenine System, with a Focus on Ageing and Neuroprotection. Molecules 2018, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minhas, P.S.; Liu, L.; Moon, P.K.; Joshi, A.U.; Dove, C.; Mhatre, S.; Contrepois, K.; Wang, Q.; Lee, B.A.; Coronado, M.; et al. Macrophage de novo NAD(+) synthesis specifies immune function in aging and inflammation. Nat Immunol 2019, 20, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Zhang, P.; Tang, X.; Wang, S.; Shen, J.; Zheng, Y.; Gao, C.; Mi, P.; Zhang, C.; Qu, H.; et al. Metabolic Rewiring of Kynurenine Pathway during Hepatic Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury Exacerbates Liver Damage by Impairing NAD Homeostasis. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2022, 9, e2204697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Borel, T.; de Azambuja, F.; Johnson, D.; Sorrentino, J.P.; Udokwu, C.; Davis, I.; Liu, A.; Altman, R.A. Diflunisal Derivatives as Modulators of ACMS Decarboxylase Targeting the Tryptophan-Kynurenine Pathway. J Med Chem 2021, 64, 797–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braidy, N.; Guillemin, G.J.; Grant, R. Effects of Kynurenine Pathway Inhibition on NAD Metabolism and Cell Viability in Human Primary Astrocytes and Neurons. Int J Tryptophan Res 2011, 4, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, C.; Li, G.; Zheng, Q.; Gu, X.; Shi, Q.; Su, Y.; Chu, Q.; Yuan, X.; Bao, Z.; Lu, J.; et al. Tryptophan metabolism in health and disease. Cell Metab 2023, 35, 1304–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, T.W.; Williams, R.O. Modulation of T cells by tryptophan metabolites in the kynurenine pathway. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2023, 44, 442–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J.; Su, W.; Wang, G.; Wang, Z. The Kynurenine Pathway and Indole Pathway in Tryptophan Metabolism Influence Tumor Progression. Cancer Med 2025, 14, e70703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Vécsei, L. From Microbial Switches to Metabolic Sensors: Rewiring the Gut-Brain Kynurenine Circuit. Biomedicines 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savitz, J. The kynurenine pathway: a finger in every pie. Mol Psychiatry 2020, 25, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mor, A.; Tankiewicz-Kwedlo, A.; Krupa, A.; Pawlak, D. Role of Kynurenine Pathway in Oxidative Stress during Neurodegenerative Disorders. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, S.; Nadar, R.; Kim, S.; Liu, K.; Govindarajulu, M.; Cook, P.; Watts Alexander, C.S.; Dhanasekaran, M.; Moore, T. The Influence of Kynurenine Metabolites on Neurodegenerative Pathologies. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Battaglia, S. From Biomarkers to Behavior: Mapping the Neuroimmune Web of Pain, Mood, and Memory. Biomedicines 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strasser, B.; Becker, K.; Fuchs, D.; Gostner, J.M. Kynurenine pathway metabolism and immune activation: Peripheral measurements in psychiatric and co-morbid conditions. Neuropharmacology 2017, 112, 286–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, M. Special Issue “Translating Molecular Psychiatry: From Biomarkers to Personalized Therapies”. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, M. Beyond the boundaries: Transitioning from categorical to dimensional paradigms in mental health diagnostics. Adv Clin Exp Med 2024, 33, 1295–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liloia, D.; Zamfira, D.A.; Tanaka, M.; Manuello, J.; Crocetta, A.; Keller, R.; Cozzolino, M.; Duca, S.; Cauda, F.; Costa, T. Disentangling the role of gray matter volume and concentration in autism spectrum disorder: A meta-analytic investigation of 25 years of voxel-based morphometry research. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2024, 164, 105791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, D.; Song, P.; Zou, M.H. Tryptophan-kynurenine pathway is dysregulated in inflammation, and immune activation. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2015, 20, 1116–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, R.; Forteza, M.J.; Ketelhuth, D.F.J. The interplay between cytokines and the Kynurenine pathway in inflammation and atherosclerosis. Cytokine 2019, 122, 154148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozieł, K.; Urbanska, E.M. Kynurenine Pathway in Diabetes Mellitus-Novel Pharmacological Target? Cells 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, A.S.; Sundaram, G.; Heng, B.; Krishnamurthy, S.; Brew, B.J.; Guillemin, G.J. Recent advances in clinical trials targeting the kynurenine pathway. Pharmacol Ther 2022, 236, 108055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sforzini, L.; Nettis, M.A.; Mondelli, V.; Pariante, C.M. Inflammation in cancer and depression: a starring role for the kynurenine pathway. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2019, 236, 2997–3011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggertsen, P.P.; Hansen, J.; Andersen, M.L.; Nielsen, J.F.; Olsen, R.K.J.; Palmfeldt, J. Simultaneous measurement of kynurenine metabolites and explorative metabolomics using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry: A novel accurate method applied to serum and plasma samples from a large healthy cohort. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2023, 227, 115304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossen, M.M.; Fleiss, B.; Zakaria, R. The current state in liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry methods for quantifying kynurenine pathway metabolites in biological samples: a systematic review. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 2025, 62, 437–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Gomez, A.; Olesti, E.; Montero-San-Martin, B.; Soldevila, A.; Deschamps, T.; Pizarro, N.; de la Torre, R.; Pozo, O.J. Determination of up to twenty carboxylic acid containing compounds in clinically relevant matrices by o-benzylhydroxylamine derivatization and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2022, 208, 114450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadok, I.; Jędruchniewicz, K.; Rawicz-Pruszyński, K.; Staniszewska, M. UHPLC-ESI-MS/MS Quantification of Relevant Substrates and Metabolites of the Kynurenine Pathway Present in Serum and Peritoneal Fluid from Gastric Cancer Patients-Method Development and Validation. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panuwet, P.; Hunter, R.E., Jr.; D’Souza, P.E.; Chen, X.; Radford, S.A.; Cohen, J.R.; Marder, M.E.; Kartavenka, K.; Ryan, P.B.; Barr, D.B. Biological Matrix Effects in Quantitative Tandem Mass Spectrometry-Based Analytical Methods: Advancing Biomonitoring. Crit Rev Anal Chem 2016, 46, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiley, L.; Nye, L.C.; Grant, I.; Andreas, N.; Chappell, K.E.; Sarafian, M.H.; Misra, R.; Plumb, R.S.; Lewis, M.R.; Nicholson, J.K.; et al. Ultrahigh-Performance Liquid Chromatography Tandem Mass Spectrometry with Electrospray Ionization Quantification of Tryptophan Metabolites and Markers of Gut Health in Serum and Plasma-Application to Clinical and Epidemiology Cohorts. Anal Chem 2019, 91, 5207–5216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chawdhury, A.; Shamsi, S.A.; Miller, A.; Liu, A. Capillary electrochromatography-mass spectrometry of kynurenine pathway metabolites. J Chromatogr A 2021, 1651, 462294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadok, I.; Rachwał, K.; Staniszewska, M. Simultaneous Quantification of Selected Kynurenines Analyzed by Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry in Medium Collected from Cancer Cell Cultures. J Vis Exp 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khetarpal, V.; Herbst, T.; Akhtar, S.; LaFayette, A.; Miller, D.; Farnham, J.; Steege, T.; Miao, Z.; Marks, B.; Ledvina, A.; et al. Validation of LC-MS/MS methods for quantitative analysis of kynurenine pathway metabolites in human plasma and cerebrospinal fluid. Bioanalysis 2023, 15, 637–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, N.; Winans, T.; Wyman, B.; Oaks, Z.; Faludi, T.; Choudhary, G.; Lai, Z.W.; Lewis, J.; Beckford, M.; Duarte, M.; et al. Rab4A-directed endosome traffic shapes pro-inflammatory mitochondrial metabolism in T cells via mitophagy, CD98 expression, and kynurenine-sensitive mTOR activation. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ou, W.; Chen, Y.; Ju, Y.; Ma, M.; Qin, Y.; Bi, Y.; Liao, M.; Liu, B.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; et al. The kynurenine pathway in major depressive disorder under different disease states: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2023, 339, 624–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristina, B.; Veronica, R.; Silvia, A.; Andrea, G.; Sara, C.; Luca, P.; Nicoletta, B.; C.B., M; Silvio, B.; Fabio, T. Identification and characterization of the kynurenine pathway in the pond snail Lymnaea stagnalis. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 15617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarcz, R.; Stone, T.W. The kynurenine pathway and the brain: Challenges, controversies and promises. Neuropharmacology 2017, 112, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadok, I.; Staniszewska, M. Electrochemical Determination of Kynurenine Pathway Metabolites-Challenges and Perspectives. Sensors (Basel) 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mrštná, K.; Krčmová, L.K.; Švec, F. Advances in kynurenine analysis. Clin Chim Acta 2023, 547, 117441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Battaglia, S.; Liloia, D. Navigating Neurodegeneration: Integrating Biomarkers, Neuroinflammation, and Imaging in Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, and Motor Neuron Disorders. Biomedicines 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, M. From Serendipity to Precision: Integrating AI, Multi-Omics, and Human-Specific Models for Personalized Neuropsychiatric Care. Biomedicines 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Rocha, A.L.; Pinto, A.P.; de Sousa Neto, I.V.; Muñoz, V.R.; Marafon, B.B.; da Silva, L.; Pauli, J.R.; Cintra, D.E.; Ropelle, E.R.; Simabuco, F.M.; et al. Exhaustive exercise abolishes REV-ERB-α circadian rhythm and shifts the kynurenine pathway to a neurotoxic profile in mice. J Physiol 2025, 603, 3923–3944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, K.M.; Slezak, T.; Kossiakoff, A.A. Conformation-specific synthetic intrabodies modulate mTOR signaling with subcellular spatial resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2025, 122, e2424679122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, J.M.; Albrecht, V.; Mann, M. MS-Based Proteomics of Body Fluids: The End of the Beginning. Mol Cell Proteomics 2023, 22, 100577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Zhao, H.; Li, Y. Mitochondrial dynamics in health and disease: mechanisms and potential targets. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rischke, S.; Hahnefeld, L.; Burla, B.; Behrens, F.; Gurke, R.; Garrett, T.J. Small molecule biomarker discovery: Proposed workflow for LC-MS-based clinical research projects. J Mass Spectrom Adv Clin Lab 2023, 28, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Yesilkanal, A.E.; Wynne, J.P.; Frankenberger, C.; Liu, J.; Yan, J.; Elbaz, M.; Rabe, D.C.; Rustandy, F.D.; Tiwari, P.; et al. Effective breast cancer combination therapy targeting BACH1 and mitochondrial metabolism. Nature 2019, 568, 254–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneditz, G.; Elias, J.E.; Pagano, E.; Zaeem Cader, M.; Saveljeva, S.; Long, K.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Arasteh, M.; Lawley, T.D.; Dougan, G.; et al. GPR35 promotes glycolysis, proliferation, and oncogenic signaling by engaging with the sodium potassium pump. Sci Signal 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elias, J.E.; Debela, M.; Sewell, G.W.; Stopforth, R.J.; Partl, H.; Heissbauer, S.; Holland, L.M.; Karlsen, T.H.; Kaser, A.; Kaneider, N.C. GPR35 prevents osmotic stress induced cell damage. Commun Biol 2025, 8, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, P.; Fan, H.; Zhang, C.; Yu, P.; Liang, X.; Chen, Y. GPR35 acts a dual role and therapeutic target in inflammation. Frontiers in Immunology 2023, 14, 1254446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.C.; Quon, T.; Engberg, S.; Mackenzie, A.E.; Tobin, A.B.; Milligan, G. G Protein-Coupled Receptor GPR35 Suppresses Lipid Accumulation in Hepatocytes. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci 2021, 4, 1835–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Yin, F.; Wu, M.; Xie, Q.; Zhao, X.; Zhu, C.; Xie, R.; Chen, C.; Liu, M.; Wang, X. G protein-coupled receptor 35 attenuates nonalcoholic steatohepatitis by reprogramming cholesterol homeostasis in hepatocytes. Acta pharmaceutica Sinica B 2023, 13, 1128–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, S.-Y.; Park, S.-J.; Im, D.-S. Protective effect of lodoxamide on hepatic steatosis through GPR35. Cellular Signalling 2019, 53, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesci, S. GPR35, ally of the anti-ischemic ATPIF1-ATP synthase interaction. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2022, 43, 891–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharmin, O.; Abir, A.H.; Potol, A.; Alam, M.; Banik, J.; Rahman, A.; Tarannum, N.; Wadud, R.; Habib, Z.F.; Rahman, M. Activation of GPR35 protects against cerebral ischemia by recruiting monocyte-derived macrophages. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 9400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boleij, A.; Fathi, P.; Dalton, W.; Park, B.; Wu, X.; Huso, D.; Allen, J.; Besharati, S.; Anders, R.A.; Housseau, F.; et al. G-protein coupled receptor 35 (GPR35) regulates the colonic epithelial cell response to enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis. Commun Biol 2021, 4, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.; He, L.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Qiu, C.; Pei, H.; Yang, D. Inhibition of GPR35 Preserves Mitochondrial Function After Myocardial Infarction by Targeting Calpain 1/2. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2020, 75, 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milligan, G. GPR35: from enigma to therapeutic target. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2023, 44, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Wu, H.; Cai, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, S.; Hou, Y.; Yin, Z.; Yan, Q.; Wang, Q.; Sun, T.; et al. A Gpr35-tuned gut microbe-brain metabolic axis regulates depressive-like behavior. Cell Host Microbe 2024, 32, 227–243.e226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; He, Z.; Han, S.; Battaglia, S. Editorial: Noninvasive brain stimulation: a promising approach to study and improve emotion regulation. Front Behav Neurosci 2025, 19, 1633936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, P.; Fan, H.; Zhang, C.; Yu, P.; Liang, X.; Chen, Y. GPR35 acts a dual role and therapeutic target in inflammation. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1254446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie, A.E.; Lappin, J.E.; Taylor, D.L.; Nicklin, S.A.; Milligan, G. GPR35 as a Novel Therapeutic Target. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2011, 2, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, T.W.; Darlington, L.G.; Badawy, A.A.-B.; Williams, R.O. The complex world of kynurenic acid: reflections on biological issues and therapeutic strategy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 9040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brust, T.F.; Conley, J.M.; Watts, V.J. Gα(i/o)-coupled receptor-mediated sensitization of adenylyl cyclase: 40 years later. Eur J Pharmacol 2015, 763, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, A.S.; Pollock, C.; Steen, H.; Shaw, P.E.; Mischak, H.; Kolch, W. Cyclic AMP-dependent kinase regulates Raf-1 kinase mainly by phosphorylation of serine 259. Mol Cell Biol 2002, 22, 3237–3246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Shi, G. Gq-Coupled Receptors in Autoimmunity. J Immunol Res 2016, 2016, 3969023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takkar, S.; Sharma, G.; Kaushal, J.B.; Abdullah, K.M.; Batra, S.K.; Siddiqui, J.A. From orphan to oncogene: The role of GPR35 in cancer and immune modulation. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2024, 77, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poźniak, O.; Sitarz, R.; Sitarz, M.Z.; Kowalczuk, D.; Słoń, E.; Dudzińska, E. Utilization of AhR and GPR35 Receptor Ligands as Superfoods in Cancer Prevention for Individuals with IBD. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nógrádi-Halmi, D.; Erdélyi-Furka, B.; Csóré, D.; Plechl, É.; Igaz, N.; Juhász, L.; Poles, M.Z.; Nógrádi, B.; Patai, R.; Polgár, T.F.; et al. Kynurenic Acid Protects Against Myocardial Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury by Activating GPR35 Receptors and Preserving Mitochondrial Structure and Function. Biomolecules 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Trevijano, E.R.; Ortiz-Zapater, E.; Gimeno, A.; Viña, J.R.; Zaragozá, R. Calpains, the proteases of two faces controlling the epithelial homeostasis in mammary gland. Front Cell Dev Biol 2023, 11, 1249317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernando, V.; Inserte, J.; Sartório, C.L.; Parra, V.M.; Poncelas-Nozal, M.; Garcia-Dorado, D. Calpain translocation and activation as pharmacological targets during myocardial ischemia/reperfusion. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2010, 49, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Lesnefsky, E.J. Heart mitochondria and calpain 1: Location, function, and targets. Biochim Biophys Acta 2015, 1852, 2372–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Won, D.J.; Krajewski, S.; Gottlieb, R.A. Calpain and mitochondria in ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Biol Chem 2002, 277, 29181–29186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Cao, T.; Zhang, L.L.; Fan, G.C.; Qiu, J.; Peng, T.Q. Targeted inhibition of calpain in mitochondria alleviates oxidative stress-induced myocardial injury. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2021, 42, 909–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, R.; Zheng, D.; Xiong, S.; Hill, D.J.; Sun, T.; Gardiner, R.B.; Fan, G.C.; Lu, Y.; Abel, E.D.; Greer, P.A.; et al. Mitochondrial Calpain-1 Disrupts ATP Synthase and Induces Superoxide Generation in Type 1 Diabetic Hearts: A Novel Mechanism Contributing to Diabetic Cardiomyopathy. Diabetes 2016, 65, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, L.; Alvarez-Curto, E.; Campbell, K.; de Munnik, S.; Canals, M.; Schlyer, S.; Milligan, G. Agonist activation of the G protein-coupled receptor GPR35 involves transmembrane domain III and is transduced via Gα13 and β-arrestin-2. Br J Pharmacol 2011, 162, 733–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domínguez-Zorita, S.; Romero-Carramiñana, I.; Santacatterina, F.; Esparza-Moltó, P.B.; Simó, C.; Del-Arco, A.; Núñez de Arenas, C.; Saiz, J.; Barbas, C.; Cuezva, J.M. IF1 ablation prevents ATP synthase oligomerization, enhances mitochondrial ATP turnover and promotes an adenosine-mediated pro-inflammatory phenotype. Cell Death Dis 2023, 14, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warnsmann, V.; Marschall, L.M.; Osiewacz, H.D. Impaired F(1)F(o)-ATP-Synthase Dimerization Leads to the Induction of Cyclophilin D-Mediated Autophagy-Dependent Cell Death and Accelerated Aging. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domínguez-Zorita, S.; Romero-Carramiñana, I.; Cuezva, J.M.; Esparza-Moltó, P.B. The ATPase Inhibitory Factor 1 is a Tissue-Specific Physiological Regulator of the Structure and Function of Mitochondrial ATP Synthase: A Closer Look Into Neuronal Function. Front Physiol 2022, 13, 868820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaou, P.E.; Lambrinidis, G.; Georgiou, M.; Karagiannis, D.; Efentakis, P.; Bessis-Lazarou, P.; Founta, K.; Kampoukos, S.; Konstantin, V.; Palmeira, C.M.; et al. Hydrolytic Activity of Mitochondrial F(1)F(O)-ATP Synthase as a Target for Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury: Discovery and In Vitro and In Vivo Evaluation of Novel Inhibitors. J Med Chem 2023, 66, 15115–15140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnatsakanyan, N.; Jonas, E.A. The new role of F(1)F(o) ATP synthase in mitochondria-mediated neurodegeneration and neuroprotection. Exp Neurol 2020, 332, 113400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acin-Perez, R.; Benincá, C.; Fernandez Del Rio, L.; Shu, C.; Baghdasarian, S.; Zanette, V.; Gerle, C.; Jiko, C.; Khairallah, R.; Khan, S.; et al. Inhibition of ATP synthase reverse activity restores energy homeostasis in mitochondrial pathologies. Embo j 2023, 42, e111699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Ji, N.; Jiang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Feng, X.; Li, J.; Zeng, X.; Wang, J.; Shen, Y.Q.; Chen, Q. GPCRs identified on mitochondrial membranes: New therapeutic targets for diseases. J Pharm Anal 2025, 15, 101178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Bermúdez, J.; Cuezva, J.M. The ATPase Inhibitory Factor 1 (IF1): A master regulator of energy metabolism and of cell survival. Biochim Biophys Acta 2016, 1857, 1167–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaim, G.; Dimroth, P. ATP synthesis by F-type ATP synthase is obligatorily dependent on the transmembrane voltage. Embo j 1999, 18, 4118–4127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimroth, P.; Kaim, G.; Matthey, U. Crucial role of the membrane potential for ATP synthesis by F(1)F(o) ATP synthases. J Exp Biol 2000, 203, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zorova, L.D.; Popkov, V.A.; Plotnikov, E.Y.; Silachev, D.N.; Pevzner, I.B.; Jankauskas, S.S.; Babenko, V.A.; Zorov, S.D.; Balakireva, A.V.; Juhaszova, M.; et al. Mitochondrial membrane potential. Anal Biochem 2018, 552, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gottlieb, E.; Armour, S.M.; Harris, M.H.; Thompson, C.B. Mitochondrial membrane potential regulates matrix configuration and cytochrome c release during apoptosis. Cell Death Differ 2003, 10, 709–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamzami, N.; Marchetti, P.; Castedo, M.; Zanin, C.; Vayssière, J.L.; Petit, P.X.; Kroemer, G. Reduction in mitochondrial potential constitutes an early irreversible step of programmed lymphocyte death in vivo. J Exp Med 1995, 181, 1661–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; He, L.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Qiu, C.; Pei, H.; Yang, D. Inhibition of GPR35 preserves mitochondrial function after myocardial infarction by targeting calpain 1/2. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology 2020, 75, 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadvar, S.; Ferreira, D.M.S.; Cervenka, I.; Ruas, J.L. The weight of nutrients: kynurenine metabolites in obesity and exercise. J Intern Med 2018, 284, 519–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, T.W.; Park, J.; Sun, J.L.; Ahn, S.H.; Abd El-Aty, A.M.; Hacimuftuoglu, A.; Kim, H.C.; Shim, J.H.; Shin, S.; Jeong, J.H. Administration of kynurenic acid reduces hyperlipidemia-induced inflammation and insulin resistance in skeletal muscle and adipocytes. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2020, 518, 110928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mándi, Y.; Endrész, V.; Mosolygó, T.; Burián, K.; Lantos, I.; Fülöp, F.; Szatmári, I.; Lőrinczi, B.; Balog, A.; Vécsei, L. The Opposite Effects of Kynurenic Acid and Different Kynurenic Acid Analogs on Tumor Necrosis Factor-α (TNF-α) Production and Tumor Necrosis Factor-Stimulated Gene-6 (TSG-6) Expression. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fallarini, S.; Magliulo, L.; Paoletti, T.; de Lalla, C.; Lombardi, G. Expression of functional GPR35 in human iNKT cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2010, 398, 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, C.A.; Tillitt, D.E.; Hannink, M. Regulation of subcellular localization of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR). Arch Biochem Biophys 2001, 389, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kewley, R.J.; Whitelaw, M.L.; Chapman-Smith, A. The mammalian basic helix-loop-helix/PAS family of transcriptional regulators. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2004, 36, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorg, O. AhR signalling and dioxin toxicity. Toxicol Lett 2014, 230, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corre, S.; Tardif, N.; Mouchet, N.; Leclair, H.M.; Boussemart, L.; Gautron, A.; Bachelot, L.; Perrot, A.; Soshilov, A.; Rogiers, A.; et al. Sustained activation of the Aryl hydrocarbon Receptor transcription factor promotes resistance to BRAF-inhibitors in melanoma. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 4775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Qu, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, L.; Wei, H.; Guo, M.; Chen, X.; Chen, Y. Structural insight into the ligand binding mechanism of aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 6234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polonio, C.M.; McHale, K.A.; Sherr, D.H.; Rubenstein, D.; Quintana, F.J. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor: a rehabilitated target for therapeutic immune modulation. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2025, 24, 610–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, M.J.; Suh, J.H.; Lee, S.H.; Poulsen, K.L.; An, Y.A.; Moorthy, B.; Hartig, S.M.; Moore, D.D.; Kim, K.H. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor maintains hepatic mitochondrial homeostasis in mice. Mol Metab 2023, 72, 101717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahman, F.; Choudhry, K.; Al-Rashed, F.; Al-Mulla, F.; Sindhu, S.; Ahmad, R. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor: current perspectives on key signaling partners and immunoregulatory role in inflammatory diseases. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1421346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nebert, D.W.; Karp, C.L. Endogenous functions of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR): intersection of cytochrome P450 1 (CYP1)-metabolized eicosanoids and AHR biology. J Biol Chem 2008, 283, 36061–36065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Vázquez, C.; Quintana, F.J. Regulation of the Immune Response by the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor. Immunity 2018, 48, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothhammer, V.; Quintana, F.J. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor: an environmental sensor integrating immune responses in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2019, 19, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nacarino-Palma, A.; González-Rico, F.J.; Rejano-Gordillo, C.M.; Ordiales-Talavero, A.; Merino, J.M.; Fernández-Salguero, P.M. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor promotes differentiation during mouse preimplantational embryo development. Stem Cell Reports 2021, 16, 2351–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiNatale, B.C.; Murray, I.A.; Schroeder, J.C.; Flaveny, C.A.; Lahoti, T.S.; Laurenzana, E.M.; Omiecinski, C.J.; Perdew, G.H. Kynurenic acid is a potent endogenous aryl hydrocarbon receptor ligand that synergistically induces interleukin-6 in the presence of inflammatory signaling. Toxicol Sci 2010, 115, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moroni, F.; Cozzi, A.; Sili, M.; Mannaioni, G. Kynurenic acid: a metabolite with multiple actions and multiple targets in brain and periphery. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2012, 119, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Wei, J.; Ran, W.; Liu, D.; Yi, Y.; Gong, M.; Liu, X.; Gong, Q.; Li, H.; Gao, J. The Gut Microbiota-Xanthurenic Acid-Aromatic Hydrocarbon Receptor Axis Mediates the Anticolitic Effects of Trilobatin. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2025, 12, e2412234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashrafi, G.; Schwarz, T.L. The pathways of mitophagy for quality control and clearance of mitochondria. Cell Death Differ 2013, 20, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youle, R.J.; Narendra, D.P. Mechanisms of mitophagy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2011, 12, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Long, H.; Hou, L.; Feng, B.; Ma, Z.; Wu, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Cai, J.; Zhang, D.W.; Zhao, G. The mitophagy pathway and its implications in human diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palikaras, K.; Tavernarakis, N. Mitophagy in neurodegeneration and aging. Front Genet 2012, 3, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamacher-Brady, A.; Brady, N.R. Mitophagy programs: mechanisms and physiological implications of mitochondrial targeting by autophagy. Cell Mol Life Sci 2016, 73, 775–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picca, A.; Faitg, J.; Auwerx, J.; Ferrucci, L.; D’Amico, D. Mitophagy in human health, ageing and disease. Nat Metab 2023, 5, 2047–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, X.; Wang, K.; Zhang, C.; Bao, J.P.; Vlf, C.; Gao, J.W.; Zhou, Z.M.; Wu, X.T. The mitochondrial antioxidant SS-31 attenuated lipopolysaccharide-induced apoptosis and pyroptosis of nucleus pulposus cells via scavenging mitochondrial ROS and maintaining the stability of mitochondrial dynamics. Free Radic Res 2021, 55, 1080–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Bao, Q.; Hao, H. Indole-3-Carboxaldehyde Alleviates LPS-Induced Intestinal Inflammation by Inhibiting ROS Production and NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation. Antioxidants (Basel) 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, M.; Guo, J.; Su, X.; Ma, B.; Wang, X.; Wangshao, M.; Zhong, K.; Wang, Y.; Yang, G.; Han, Y. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) alleviates the LPS-induced inflammatory responses in IPEC-J2 cells by activating PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy. Inflamm Res 2025, 74, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanis, J.M.; Alexeev, E.E.; Curtis, V.F.; Kitzenberg, D.A.; Kao, D.J.; Battista, K.D.; Gerich, M.E.; Glover, L.E.; Kominsky, D.J.; Colgan, S.P. Tryptophan metabolite activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor regulates IL-10 receptor expression on intestinal epithelia. Mucosal Immunol 2017, 10, 1133–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M. Parkinson’s Disease: Bridging Gaps, Building Biomarkers, and Reimagining Clinical Translation. Cells 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zheng, W.; Lu, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Pan, L.; Wu, X.; Yuan, Y.; Shen, Z.; Ma, S.; Zhang, X.; et al. BNIP3L/NIX-mediated mitophagy: molecular mechanisms and implications for human disease. Cell Death Dis 2021, 13, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.X.; Yin, X.M. Mitophagy: mechanisms, pathophysiological roles, and analysis. Biol Chem 2012, 393, 547–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antico, O.; Thompson, P.W.; Hertz, N.T.; Muqit, M.M.K.; Parton, L.E. Targeting mitophagy in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2025, 24, 276–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palikaras, K.; Lionaki, E.; Tavernarakis, N. Mechanisms of mitophagy in cellular homeostasis, physiology and pathology. Nat Cell Biol 2018, 20, 1013–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onishi, M.; Yamano, K.; Sato, M.; Matsuda, N.; Okamoto, K. Molecular mechanisms and physiological functions of mitophagy. Embo j 2021, 40, e104705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birgisdottir Å, B.; Lamark, T.; Johansen, T. The LIR motif—crucial for selective autophagy. J Cell Sci 2013, 126, 3237–3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, Y.; Li, H.; Liao, P.; Chen, L.; Pan, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liu, D.; Zheng, M.; Gao, J. Mitochondrial dysfunction: mechanisms and advances in therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2024, 9, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.P.; Hartley, R.C. Mitochondria as a therapeutic target for common pathologies. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2018, 17, 865–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogeris, T.; Bao, Y.; Korthuis, R.J. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species: a double edged sword in ischemia/reperfusion vs preconditioning. Redox Biol 2014, 2, 702–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senft, A.P.; Dalton, T.P.; Nebert, D.W.; Genter, M.B.; Puga, A.; Hutchinson, R.J.; Kerzee, J.K.; Uno, S.; Shertzer, H.G. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen production is dependent on the aromatic hydrocarbon receptor. Free Radic Biol Med 2002, 33, 1268–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onishi, M.; Okamoto, K. Mitochondrial clearance: mechanisms and roles in cellular fitness. FEBS Lett 2021, 595, 1239–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garza-Lombó, C.; Pappa, A.; Panayiotidis, M.I.; Franco, R. Redox homeostasis, oxidative stress and mitophagy. Mitochondrion 2020, 51, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Tao, Y.; Ji, C.; Aniagu, S.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, T. AHR/ROS-mediated mitochondria apoptosis contributes to benzo[a]pyrene-induced heart defects and the protective effects of resveratrol. Toxicology 2021, 462, 152965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, S.; Liu, L.; Jian, Z.; Cui, T.; Yang, Y.; Guo, S.; Yi, X.; Wang, G.; Li, C.; et al. Role of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling pathway in promoting mitochondrial biogenesis against oxidative damage in human melanocytes. J Dermatol Sci 2019, 96, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, M.; Zou, H.; Aniagu, S.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, T. PM2.5 induces mitochondrial dysfunction via AHR-mediated cyp1a1 overexpression during zebrafish heart development. Toxicology 2023, 487, 153466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, R.; Fang, Y.; Sherchan, P.; Lu, Q.; Lenahan, C.; Zhang, J.H.; Zhang, J.; Tang, J. Kynurenine/Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Modulates Mitochondria-Mediated Oxidative Stress and Neuronal Apoptosis in Experimental Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Antioxid Redox Signal 2022, 37, 1111–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majláth, Z.; Török, N.; Toldi, J.; Vécsei, L. Memantine and Kynurenic Acid: Current Neuropharmacological Aspects. Curr Neuropharmacol 2016, 14, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, M.W.; Kessler, M.; Larson, J.; Schottler, F.; Lynch, G. Glycine site associated with the NMDA receptor modulates long-term potentiation. Synapse 1990, 5, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, P.J.; Grossman, C.J.; Hayes, A.G. Kynurenic acid antagonises responses to NMDA via an action at the strychnine-insensitive glycine receptor. Eur J Pharmacol 1988, 154, 85–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poles, M.Z.; Nászai, A.; Gulácsi, L.; Czakó, B.L.; Gál, K.G.; Glenz, R.J.; Dookhun, D.; Rutai, A.; Tallósy, S.P.; Szabó, A.; et al. Kynurenic Acid and Its Synthetic Derivatives Protect Against Sepsis-Associated Neutrophil Activation and Brain Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Rats. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 717157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaszaki, J.; Erces, D.; Varga, G.; Szabó, A.; Vécsei, L.; Boros, M. Kynurenines and intestinal neurotransmission: the role of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2012, 119, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, K.B.; Yi, F.; Perszyk, R.E.; Menniti, F.S.; Traynelis, S.F. NMDA Receptors in the Central Nervous System. Methods Mol Biol 2017, 1677, 1–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mony, L.; Paoletti, P. Mechanisms of NMDA receptor regulation. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2023, 83, 102815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, D.R.; Haworth, R.A. The Ca2+-induced membrane transition in mitochondria. I. The protective mechanisms. Arch Biochem Biophys 1979, 195, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nászai, A.; Terhes, E.; Kaszaki, J.; Boros, M.; Juhász, L. Ca((2+))N It Be Measured? Detection of Extramitochondrial Calcium Movement With High-Resolution FluoRespirometry. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 19229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mira, R.G.; Cerpa, W. Building a Bridge Between NMDAR-Mediated Excitotoxicity and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Chronic and Acute Diseases. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2021, 41, 1413–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halestrap, A.P. What is the mitochondrial permeability transition pore? J Mol Cell Cardiol 2009, 46, 821–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonora, M.; Giorgi, C.; Pinton, P. Molecular mechanisms and consequences of mitochondrial permeability transition. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2022, 23, 266–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endlicher, R.; Drahota, Z.; Štefková, K.; Červinková, Z.; Kučera, O. The Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore-Current Knowledge of Its Structure, Function, and Regulation, and Optimized Methods for Evaluating Its Functional State. Cells 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baev, A.Y.; Vinokurov, A.Y.; Potapova, E.V.; Dunaev, A.V.; Angelova, P.R.; Abramov, A.Y. Mitochondrial Permeability Transition, Cell Death and Neurodegeneration. Cells 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, J.S.; Tait, S.W. Mitochondrial DNA in inflammation and immunity. EMBO Rep 2020, 21, e49799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrushev, M.; Kasymov, V.; Patrusheva, V.; Ushakova, T.; Gogvadze, V.; Gaziev, A. Mitochondrial permeability transition triggers the release of mtDNA fragments. Cell Mol Life Sci 2004, 61, 3100–3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Wei, H.; Zhao, A.; Yan, X.; Zhang, X.; Gan, J.; Guo, M.; Wang, J.; Zhang, F.; Jiang, Y.; et al. Mitochondrial DNA leakage: underlying mechanisms and therapeutic implications in neurological disorders. J Neuroinflammation 2025, 22, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.Y.; Lee, K.S.; Lee, H.J.; Noh, Y.H.; Kim, D.H.; Lee, J.Y.; Cho, S.H.; Yoon, O.J.; Lee, W.B.; Kim, K.Y.; et al. Kynurenic acid attenuates MPP(+)-induced dopaminergic neuronal cell death via a Bax-mediated mitochondrial pathway. Eur J Cell Biol 2008, 87, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, M.; Lajkó, N.; Dulka, K.; Szatmári, I.; Fülöp, F.; Mihály, A.; Vécsei, L.; Gulya, K. Kynurenic Acid and Its Analog SZR104 Exhibit Strong Antiinflammatory Effects and Alter the Intracellular Distribution and Methylation Patterns of H3 Histones in Immunochallenged Microglia-Enriched Cultures of Newborn Rat Brains. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesterov, S.V.; Skorobogatova, Y.A.; Panteleeva, A.A.; Pavlik, L.L.; Mikheeva, I.B.; Yaguzhinsky, L.S.; Nartsissov, Y.R. NMDA and GABA receptor presence in rat heart mitochondria. Chem Biol Interact 2018, 291, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korde, A.S.; Maragos, W.F. Identification of an N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor in isolated nervous system mitochondria. J Biol Chem 2012, 287, 35192–35200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korde, A.S.; Maragos, W.F. Mitochondrial N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor activation enhances bioenergetics by calcium-dependent and -Independent mechanisms. Mitochondrion 2021, 59, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gingrich, J.R.; Pelkey, K.A.; Fam, S.R.; Huang, Y.; Petralia, R.S.; Wenthold, R.J.; Salter, M.W. Unique domain anchoring of Src to synaptic NMDA receptors via the mitochondrial protein NADH dehydrogenase subunit 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004, 101, 6237–6242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scanlon, D.P.; Bah, A.; Krzeminski, M.; Zhang, W.; Leduc-Pessah, H.L.; Dong, Y.N.; Forman-Kay, J.D.; Salter, M.W. An evolutionary switch in ND2 enables Src kinase regulation of NMDA receptors. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 15220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salter, M.W.; Kalia, L.V. Src kinases: a hub for NMDA receptor regulation. Nat Rev Neurosci 2004, 5, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szabó, Á.; Galla, Z.; Spekker, E.; Szűcs, M.; Martos, D.; Takeda, K.; Ozaki, K.; Inoue, H.; Yamamoto, S.; Toldi, J.; et al. Oxidative and Excitatory Neurotoxic Stresses in CRISPR/Cas9-Induced Kynurenine Aminotransferase Knockout Mice: A Novel Model for Despair-Based Depression and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2025, 30, 25706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbalho, S.M.; Leme Boaro, B.; da Silva Camarinha Oliveira, J.; Patočka, J.; Barbalho Lamas, C.; Tanaka, M.; Laurindo, L.F. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Neuroinflammation Intervention with Medicinal Plants: A Critical and Narrative Review of the Current Literature. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2025, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Lima, E.P.; Tanaka, M.; Lamas, C.B.; Quesada, K.; Detregiachi, C.R.P.; Araújo, A.C.; Guiguer, E.L.; Catharin, V.; de Castro, M.V.M.; Junior, E.B.; et al. Vascular Impairment, Muscle Atrophy, and Cognitive Decline: Critical Age-Related Conditions. Biomedicines 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, M.; Vécsei, L. Revolutionizing our understanding of Parkinson’s disease: Dr. Heinz Reichmann’s pioneering research and future research direction. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2024, 131, 1367–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vécsei, L.; Szalárdy, L.; Fülöp, F.; Toldi, J. Kynurenines in the CNS: recent advances and new questions. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2013, 12, 64–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujigaki, H.; Yamamoto, Y.; Saito, K. L-Tryptophan-kynurenine pathway enzymes are therapeutic target for neuropsychiatric diseases: Focus on cell type differences. Neuropharmacology 2017, 112, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Yu, J.T.; Tan, L. The kynurenine pathway in neurodegenerative diseases: mechanistic and therapeutic considerations. J Neurol Sci 2012, 323, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Németh, H.; Toldi, J.; Vécsei, L. Kynurenines, Parkinson’s disease and other neurodegenerative disorders: preclinical and clinical studies. J Neural Transm Suppl 2006, 285–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostapiuk, A.; Urbanska, E.M. Kynurenic acid in neurodegenerative disorders-unique neuroprotection or double-edged sword? CNS Neurosci Ther 2022, 28, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gergalova, G.; Lykhmus, O.; Kalashnyk, O.; Koval, L.; Chernyshov, V.; Kryukova, E.; Tsetlin, V.; Komisarenko, S.; Skok, M. Mitochondria express α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors to regulate Ca2+ accumulation and cytochrome c release: study on isolated mitochondria. PLoS One 2012, 7, e31361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalashnyk, O.; Lykhmus, O.; Uspenska, K.; Izmailov, M.; Komisarenko, S.; Skok, M. Mitochondrial α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors are displaced from complexes with VDAC1 to form complexes with Bax upon apoptosis induction. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2020, 129, 105879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gergalova, G.; Lykhmus, O.; Komisarenko, S.; Skok, M. α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors control cytochrome c release from isolated mitochondria through kinase-mediated pathways. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2014, 49, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, S.M.; Suresh, S.; Komal, P. Targeting Neuronal Alpha7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Upregulation in Age-Related Neurological Disorders. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2025, 45, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papke, R.L.; Horenstein, N.A. Therapeutic Targeting of α7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors. Pharmacol Rev 2021, 73, 1118–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Shen, F.; Lin, L.; Zhang, X.; Bruce, I.C.; Xia, Q. The neuroprotection conferred by activating the mitochondrial ATP-sensitive K+ channel is mediated by inhibiting the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Neurosci Lett 2006, 402, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, J.E.; Qian, Y.Z.; Gross, G.J.; Kukreja, R.C. The ischemia-selective KATP channel antagonist, 5-hydroxydecanoate, blocks ischemic preconditioning in the rat heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol 1997, 29, 1055–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Jiao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wu, W.; Zheng, J.; Li, J. G-Protein Coupled Receptor 35 Induces Intervertebral Disc Degeneration by Mediating the Influx of Calcium Ions and Upregulating Reactive Oxygen Species. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2022, 2022, 5469220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirst, J. Mitochondrial complex I. Annu Rev Biochem 2013, 82, 551–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleier, L.; Dröse, S. Superoxide generation by complex III: from mechanistic rationales to functional consequences. Biochim Biophys Acta 2013, 1827, 1320–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoye, C.N.; Koren, S.A.; Wojtovich, A.P. Mitochondrial complex I ROS production and redox signaling in hypoxia. Redox Biol 2023, 67, 102926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugo-Huitrón, R.; Blanco-Ayala, T.; Ugalde-Muñiz, P.; Carrillo-Mora, P.; Pedraza-Chaverrí, J.; Silva-Adaya, D.; Maldonado, P.D.; Torres, I.; Pinzón, E.; Ortiz-Islas, E.; et al. On the antioxidant properties of kynurenic acid: free radical scavenging activity and inhibition of oxidative stress. Neurotoxicol Teratol 2011, 33, 538–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tappenden, D.M.; Lynn, S.G.; Crawford, R.B.; Lee, K.; Vengellur, A.; Kaminski, N.E.; Thomas, R.S.; LaPres, J.J. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor interacts with ATP5α1, a subunit of the ATP synthase complex, and modulates mitochondrial function. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2011, 254, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkmann, V.; Ale-Agha, N.; Haendeler, J.; Ventura, N. The Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor (AhR) in the Aging Process: Another Puzzling Role for This Highly Conserved Transcription Factor. Front Physiol 2019, 10, 1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkondon, M.; Pereira, E.F.; Yu, P.; Arruda, E.Z.; Almeida, L.E.; Guidetti, P.; Fawcett, W.P.; Sapko, M.T.; Randall, W.R.; Schwarcz, R.; et al. Targeted deletion of the kynurenine aminotransferase ii gene reveals a critical role of endogenous kynurenic acid in the regulation of synaptic transmission via alpha7 nicotinic receptors in the hippocampus. J Neurosci 2004, 24, 4635–4648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugayar, A.A.; da Silva Guimarães, G.; de Oliveira, P.H.T.; Miranda, R.L.; Dos Santos, A.A. Apoptosis in the neuroprotective effect of α7 nicotinic receptor in neurodegenerative models. J Neurosci Res 2023, 101, 1795–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braidy, N.; Grant, R.; Brew, B.J.; Adams, S.; Jayasena, T.; Guillemin, G.J. Effects of Kynurenine Pathway Metabolites on Intracellular NAD Synthesis and Cell Death in Human Primary Astrocytes and Neurons. Int J Tryptophan Res 2009, 2, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, J.E.; Sun, L. Targeting the IDO1/TDO2-KYN-AhR Pathway for Cancer Immunotherapy—Challenges and Opportunities. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2018, 39, 307–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouasmi, R.; Ferraro-Peyret, C.; Nancey, S.; Coste, I.; Renno, T.; Chaveroux, C.; Aznar, N.; Ansieau, S. The Kynurenine Pathway and Cancer: Why Keep It Simple When You Can Make It Complicated. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luongo, T.S.; Eller, J.M.; Lu, M.J.; Niere, M.; Raith, F.; Perry, C.; Bornstein, M.R.; Oliphint, P.; Wang, L.; McReynolds, M.R.; et al. SLC25A51 is a mammalian mitochondrial NAD(+) transporter. Nature 2020, 588, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kory, N.; Uit de Bos, J.; van der Rijt, S.; Jankovic, N.; Güra, M.; Arp, N.; Pena, I.A.; Prakash, G.; Chan, S.H.; Kunchok, T.; et al. MCART1/SLC25A51 is required for mitochondrial NAD transport. Sci Adv 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girardi, E.; Agrimi, G.; Goldmann, U.; Fiume, G.; Lindinger, S.; Sedlyarov, V.; Srndic, I.; Gürtl, B.; Agerer, B.; Kartnig, F.; et al. Epistasis-driven identification of SLC25A51 as a regulator of human mitochondrial NAD import. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 6145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Reyes, I.; Chandel, N.S. Mitochondrial TCA cycle metabolites control physiology and disease. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronchi, J.A.; Francisco, A.; Passos, L.A.; Figueira, T.R.; Castilho, R.F. The Contribution of Nicotinamide Nucleotide Transhydrogenase to Peroxide Detoxification Is Dependent on the Respiratory State and Counterbalanced by Other Sources of NADPH in Liver Mitochondria. J Biol Chem 2016, 291, 20173–20187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronchi, J.A.; Figueira, T.R.; Ravagnani, F.G.; Oliveira, H.C.; Vercesi, A.E.; Castilho, R.F. A spontaneous mutation in the nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase gene of C57BL/6J mice results in mitochondrial redox abnormalities. Free Radic Biol Med 2013, 63, 446–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher-Wellman, K.H.; Lin, C.T.; Ryan, T.E.; Reese, L.R.; Gilliam, L.A.; Cathey, B.L.; Lark, D.S.; Smith, C.D.; Muoio, D.M.; Neufer, P.D. Pyruvate dehydrogenase complex and nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase constitute an energy-consuming redox circuit. Biochem J 2015, 467, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmen, F.A.; Alhallak, I.; Simmen, R.C.M. Malic enzyme 1 (ME1) in the biology of cancer: it is not just intermediary metabolism. J Mol Endocrinol 2020, 65, R77–r90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, M.; You, D.; Zhu, X.; Cai, L.; Zeng, S.; Hu, X. Lactate and glutamine support NADPH generation in cancer cells under glucose deprived conditions. Redox Biol 2021, 46, 102065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Baixauli, J.; Abasolo, N.; Palacios-Jordan, H.; Foguet-Romero, E.; Suñol, D.; Galofré, M.; Caimari, A.; Baselga-Escudero, L.; Del Bas, J.M.; Mulero, M. Imbalances in TCA, Short Fatty Acids and One-Carbon Metabolisms as Important Features of Homeostatic Disruption Evidenced by a Multi-Omics Integrative Approach of LPS-Induced Chronic Inflammation in Male Wistar Rats. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, M.L.; Quon, E.; Vigil, A.B.G.; Engstrom, I.A.; Newsom, O.J.; Davidsen, K.; Hoellerbauer, P.; Carlisle, S.M.; Sullivan, L.B. Mitochondrial redox adaptations enable alternative aspartate synthesis in SDH-deficient cells. Elife 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lussey-Lepoutre, C.; Hollinshead, K.E.; Ludwig, C.; Menara, M.; Morin, A.; Castro-Vega, L.J.; Parker, S.J.; Janin, M.; Martinelli, C.; Ottolenghi, C.; et al. Loss of succinate dehydrogenase activity results in dependency on pyruvate carboxylation for cellular anabolism. Nat Commun 2015, 6, 8784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban-Amo, M.J.; Jiménez-Cuadrado, P.; Serrano-Lorenzo, P.; de la Fuente, M.; Simarro, M. Succinate Dehydrogenase and Human Disease: Novel Insights into a Well-Known Enzyme. Biomedicines 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Cheng, C.; Hu, J.; Huang, H.; Han, Q.; Jie, Z.; Zou, Q.; Shi, J.H.; Yu, X. De novo NAD(+) synthesis contributes to CD8(+) T cell metabolic fitness and antitumor function. Cell Rep 2023, 42, 113518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghdoust, M.; Das, A.; Kaushik, D.K. Fueling neurodegeneration: metabolic insights into microglia functions. J Neuroinflammation 2024, 21, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moffett, J.R.; Arun, P.; Puthillathu, N.; Vengilote, R.; Ives, J.A.; Badawy, A.A.; Namboodiri, A.M. Quinolinate as a Marker for Kynurenine Metabolite Formation and the Unresolved Question of NAD(+) Synthesis During Inflammation and Infection. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McReynolds, M.R.; Wang, W.; Holleran, L.M.; Hanna-Rose, W. Uridine monophosphate synthetase enables eukaryotic de novo NAD(+) biosynthesis from quinolinic acid. J Biol Chem 2017, 292, 11147–11153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]