1. Introduction

Recent advances in high-resolution three-dimensional topographic scanning technologies such as LiDAR and drones have enabled precise observation of spatiotemporal changes in river morphology, providing a foundation for quantitative analysis of the complex topographic characteristics of meandering channels. However, “precise morphological information” does not necessarily translate into “the dynamic state of the river” for physical understanding or practical river management. Meandering channels are governed by complex, superimposed hydraulic-geomorphic processes that are difficult to interpret through visual analysis alone. Since 3D data provides only static snapshots, it requires abstraction into physically meaningful indicators—specifically first-, second-, and third-order cross-sectional moments—to enable effective engineering judgment.

Cross-sectional indicators such as first-, second-, and third-order moments are “compressed records of processes.” The cross-sectional moment-based indicators are summary measures that temporally condense the results of hydraulic and geomorphic processes over extended periods. Spatially, they also condense cumulative geomorphic changes into a physically interpretable form. These indicators offer a practical alternative to high-cost, high-complexity long-term monitoring by diagnosing channel stability and predicting future behavior even with limited datasets. For example, first- and third-order cross-sectional moments reflect localized erosion patterns, while velocity–thalweg discrepancy can indirectly indicate secondary flow intensity and high-energy zones. Thus, this study establishes a moment-based indicator framework to bridge the gap between qualitative morphological observation and quantitative hydraulic interpretation.

Early research on river channel morphology focused on establishing empirical relationships among width, depth, and velocity based on the hydraulic geometry concept proposed by Leopold and Maddock (1953)[

1]. Subsequently, Williams (1978)[

2] validated Langbein’s (1964)[

3] minimum-variance theory by evaluating the theoretical validity and predictive capability of the theory based on the statistical variance of hydraulic exponents in hydraulic geometry relationships for width, depth, and mean velocity. While these studies made important contributions to explaining the average geometric characteristics of river cross-sections, they did not include internal asymmetry or local morphological changes associated with channel bends in their analysis.

Similarly, the width–depth ratio was proposed by Rosgen (1994, 2001)[

4,

5] as a representative morphological indicator for river stability assessment. However, this indicator is also defined primarily based on average cross-sectional characteristics and has structural limitations in adequately reflecting asymmetric features such as channel asymmetry, lateral erosion, and thalweg migration that occur in meandering channels. In other words, early and subsequent representative cross-sectional indicators have primarily evaluated river morphology based on average geometric characteristics and have been limited in interpreting the asymmetric structure inherent to meandering channels.

Meanwhile, research has also been conducted to directly quantify cross-sectional asymmetry, recognizing the limitations of these average cross-sectional indicators. Knighton (1981)[

6] proposed an asymmetry index using the difference in left and right cross-sectional areas to quantitatively express the symmetry and asymmetry of river cross-sections, and Xu et al. (2022)[

7] applied the asymmetry index to the lower Yellow River to analyze the relationship with water and sediment distribution. However, these studies focused primarily on expressing cross-sectional asymmetry with a single indicator and did not extend to linking analysis with higher-order characteristics of cross-sectional morphology or velocity structure.

A separate research stream has been formed regarding the hydraulic characteristics of meandering channels. Falcon (1979)[

8] and Falcon and Kennedy (1983)[

9] analyzed flow structure in curved channels theoretically and experimentally, while Zimmermann and Kennedy (1978)[

10], Odgaard (1981)[

11], and Odgaard and Kennedy (1982)[

12] investigated the interaction between transverse bed slope and velocity structure in channel bends. These studies remained focused on the identification of the physical mechanisms by which cross-sectional asymmetry occurs in bends, without quantifying morphological indicators. In Korea, research has also consistently explored methodologies for observing the velocity structure and bed morphology of meandering channels by integrating techniques such as ADCP and RTK-GPS (Lee et al., 2009; Jeong, 2014)[

13,

14]. However, these studies focused primarily on velocity structure or thalweg behavior itself and did not extend to quantitative integration analysis with cross-sectional morphological indicators.

Recently, Ko et al. (2019, 2020)[

15,

16] presented a methodology to quantify longitudinal change of river bed based on cross-sectional area change using cross-sectional moments and geometric characteristic values from large river field measurement data. These studies demonstrated that cross-sectional moments are useful indicators for explaining river morphological changes, but the scope of analysis was mainly limited to longitudinal changes and statistical characteristics of cross-sectional morphology and lacked the integration of cross-sectional asymmetry, velocity structure, and channel curvature. Additionally, Dixon et al. (2018)[

17] analyzed planform changes at river confluences using remote sensing data, and Formann et al. (2007)[

18] presented techniques for evaluating morphodynamic changes in mountain gravel-bed rivers, but these studies also did not directly link moment characteristics of cross-sectional morphology with hydraulic variables.

In summary, existing research has analyzed average cross-sectional geometric characteristics, cross-sectional asymmetry, and velocity and thalweg structure in meandering sections from independent perspectives, and studies that integrate moment characteristics of cross-sectional morphology, asymmetric structure, velocity–thalweg relationships, and channel curvature as a unified system in meandering channels are relatively scarce. Furthermore, the third-order cross-sectional moment, which is important for identifying both the direction and intensity of cross-sectional asymmetry and quantitatively evaluating the preferential patterns of erosion in meandering channels, has rarely been addressed in existing research. Therefore, this study aims (1) to conduct integrated analysis of first-, second-, and third-order cross-sectional moments with velocity–thalweg dynamics, and channel curvature in meandering channels, (2) to establish a systematic interpretive framework for meandering channel cross-sectional characteristics, and (3) to enhance the practical applicability of hydraulic-geometric indicators to river management and design.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Area

The Nakdong River Basin, located in the southeastern Korean Peninsula, is one of the four major river systems in South Korea (MOLIT, 2013)[

19]. It drains an area of 23,384.21 km², representing 25.9% of the national territory, with a total channel length of 510.36 km (MOLIT, 2013)[

19]. The spatial scope of this study covers an approximately 20 km reach extending downstream from the Gangjeong-Goryeong Weir to the Dalseong Weir, as shown in

Figure 1(a). The upstream portion of this reach includes the confluence with the Geumho River, while the overall reach is characterized by complex geomorphic features, including mid-channel bars, the Dalseong Wetland, and a sequence of three distinct channel bends. For the geometric evaluation, a total of 40 cross-sectional stations were established to match the official levee reference points defined by MOLIT (2012)[

20], as illustrated in

Figure 1(b).

The study reach underwent dramatic morphological transformations due to the large-scale Four Major Rivers Restoration Project (2009–2012). Prior to the project, the reach exhibited complex hydraulic-geomorphic characteristics with extensively developed point bars and sand bars. However, post-project dredging and channelization standardized the low-flow channel, resulting in more uniform widths and depths. Specifically, large-scale dredging in the central channel expanded the low-flow width and increased depth uniformity, effectively removing existing bars and simplifying the cross-sectional geometry.

These anthropogenic changes are considered primary drivers for abrupt shifts in cross-sectional moment values and the alignment between velocity distribution and the thalweg. To analyze these variations, satellite imagery and field measurement data were collected and compared across three distinct phases (

Figure 2).

This rapid morphological transition provides an ideal environment to verify the effectiveness of moment-based indicators in explaining both anthropogenic deformation and the subsequent natural stabilization processes of the river.

2.2. Data Acquisition

The topographic data utilized in this study were synthesized from multiple official records and high-precision field measurements. The 2009 data were obtained from the River Basic Plans (MOLIT, 2009)[

21], and the 2012 data were sourced from the subsequent River Basic Plans (MOLIT, 2013)[

19]. The 2017 dataset was acquired from the field measurement results of Ko et al. (2019)[

15].

Standard surveying for the establishment of a River Basic Plan typically comprises bathymetric, terrestrial, and wide-cross-sectional surveys. Bathymetric and terrestrial surveys are generally conducted at 20 m longitudinal intervals to calculate channel dredging volumes. Furthermore, wide-cross-sectional surveys are performed at 500 m intervals at the same levee stations used in previous plans to ensure high-precision monitoring of the river reach (MOLIT, 2013)[

19]. However, for the 2012 topography and cross-sections (MOLIT, 2013)[

19], the survey outcomes from the Four Major Rivers Restoration Project were utilized instead of newly commissioned standard surveys.

For the 2017 survey conducted by Ko et al. (2019)[

15], high-precision 3D topographic information was acquired using advanced surveying techniques. The floodplain was surveyed using the Real-Time Kinematic (RTK) method with a Global Positioning System (GPS; Sokkia GRX1). For the main channel, bathymetry was continuously measured using an Acoustic Doppler Current Profiler (ADCP; Sontek M9), allowing for the acquisition of precise bed elevation data and the construction of a detailed three-dimensional topographic model.

2.3. Quantification of Cross-Sectional Indicators

In this study, core parameters and indicators were defined to interpret the hydraulic characteristics of the river in connection with the geometric features of its cross-sections. These indicators were quantified based on field-measured bed topography and velocity data. The primary analysis indicators selected include the geometric moments of the cross-sections, centroids, width-to-depth (W/D) ratios, cross-sectional symmetry, velocity–thalweg alignment, and channel curvature. The specific calculation methods for each indicator are defined as follows.

2.3.1. Geometric Moments

To quantitatively characterize the spatial distribution of river cross-sectional morphology, geometric moments based on statistical moment theory were calculated. In this study, the main channel center was established as the reference axis (x = 0) to effectively analyze the lateral eccentricity and asymmetry of the cross-sections. After discretizing the cross-section into infinitesimal units, the n-th order moments were computed using each elemental area (Ai) and its corresponding lateral distance (xi) from the reference axis. The first-order moment (M1), which defines the center of mass and the degree of eccentricity of the cross-section, is expressed as follows:

This indicator represents the relative position between the main channel center and the cross-sectional centroid, quantifying the degree of lateral imbalance in the channel morphology. An M1 value close to zero implies that the centroid of the cross-section coincides with the main channel center. In contrast, positive or negative values indicate a lateral shift of the sectional mass toward the right or left bank, respectively.

The formula for the second-order moment (M2) is as follows. This indicator represents the degree of dispersion in the cross-sectional morphology and reflects the characteristics of channel curvature and width variations. A larger M2 value indicates greater variability in the cross-section relative to the main channel center.

The formula for the third-order moment (M3) is as follows. As an indicator that quantifies the asymmetry of the cross-section, it sensitively reflects the lateral imbalance relative to the main channel center. A positive value indicates a bias toward the right bank, while a negative value signifies a bias toward the left bank.

2.3.2. Width-to-Depth Ratio (W/D ratio)

The Width-to-Depth (W/D) ratio is a representative indicator that simplifies the overall shape of a river cross-section, and it was calculated by dividing the water surface width (W) by the maximum depth (D).

A larger W/D ratio indicates a wide and shallow channel geometry, while a smaller ratio signifies a narrow and deep configuration. In this study, the W/D ratio of each cross-section was calculated to compare the morphological characteristics of different reaches.

2.3.3. Cross-Sectional Asymmetry Index

The asymmetry of the cross-section was quantified by comparing the areas of the left and right banks. The asymmetry index (A*) was defined using the left bank area (AL), right bank area (AR), and total area (AT) as follows:

In this formulation, A* > 0 indicates that the right bank area is more dominant than the left, while A* < 0 signifies that the left bank area is dominant. An A* value close to zero indicates a near-symmetrical state. By omitting the absolute value, this index reflects not only the degree of imbalance but also the directional dominance of the sectional profile. This approach is particularly useful for interpreting differential erosion and deposition processes between the left and right banks of a river.

2.3.4. Relationship between Thalweg and Streamwise Velocity

The thalweg was identified by connecting the points of maximum bed depth at each cross-section. Velocity data, measured using an ADCP (Sontek M9), were calculated based on coordinate components and projected into the streamwise direction, accounting for the orientation angle (θ) of the cross-sectional survey line.

where u and v represent the velocity components in the East and North directions, respectively, and θ is the orientation angle of the survey transect. By comparing the spatial alignment between the thalweg and the center of the streamwise velocity distribution (velocity core), the hydraulic and geomorphic characteristics of the river were evaluated simultaneously. A high degree of alignment between the thalweg and the velocity core indicates a stable flow regime. Conversely, a discrepancy between them was interpreted as a reflection of the influence of cross-sectional asymmetry, channel curvature, and localized flow resistance..

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Moment-Based Morphological Indicators

3.1.1. Correlation Between First-Order Moment and Centroid

The first-order moment (M1) is an indicator used to determine the location of the center of mass (centroid) of an area, effectively quantifying the “lateral bias” of the cross-sectional morphology. Therefore, in this study, the location of the sectional center was identified and its validity was examined by comparing M1 with the actual sectional centroid. The analysis revealed that the spatial distribution of M1 across all surveyed sections (Section Nos. 324–363) showed a high degree of consistency with the location of the centroid.

As illustrated in

Figure 3, in reaches where the sectional area is skewed toward either the right or left bank, the M1 values exhibit a distinct bias in the same direction, accurately replicating the movement of the centroid. Notably, in specific sections likely corresponding to river bends (e.g., the vicinity of Sections 331–335), both M1 and the centroid deviated significantly from the reference centerline as the area imbalance increased. These findings demonstrate that the first-order moment is a highly valid indicator for identifying the geometric center of mass and the asymmetric morphological shifts of the channel.

3.1.2. Correlation Between Second-Order Moment and W/D Ratio

The second-order moment (M2) is an indicator that represents the degree of spatial dispersion of the cross-sectional area from the center. As a morphological characteristic indicator, it is useful for identifying the width-to-depth structure and analyzing long-term trends in channel widening or deepening. Furthermore, it indicates the hydraulic capacity of a section to distribute flow based on its shape. Specifically, a cross-section with a wide dispersion from the center of depth may suggest a vulnerability to unstable flow or lateral erosion under certain conditions.

The analysis showed that while M2 and the W/D ratio are generally correlated, their trends diverged depending on the sectional geometry (

Figure 4). A similar trend between the two indicators occurs primarily in symmetrical and simple cross-sections. However, discrepancies were observed in the following cases: (1) Asymmetric Sections (Curvature, Localized Scour/Deposition): In sections with asymmetric development, M2 tends to increase significantly due to the lateral spread of area, whereas the W/D ratio may remain relatively similar. (2) Sections with large Width and Depth: Since the area is dispersed further from the center, M2 increases sharply even if the W/D ratio remains constant. (3) Sectional Profile Changes (U-shape vs. V-shape): Even with a constant W/D ratio, a sharp V-shaped section exhibits a decrease in M2 compared to a U-shaped section because the area is more concentrated near the center.

In conclusion, M2 proved to be a more precise indicator than the intuitive W/D ratio, as it captures the internal mass distribution and the hydraulic potential of the river cross-section.

3.1.3. Correlation Between Third-Order Moment and Asymmetry Index

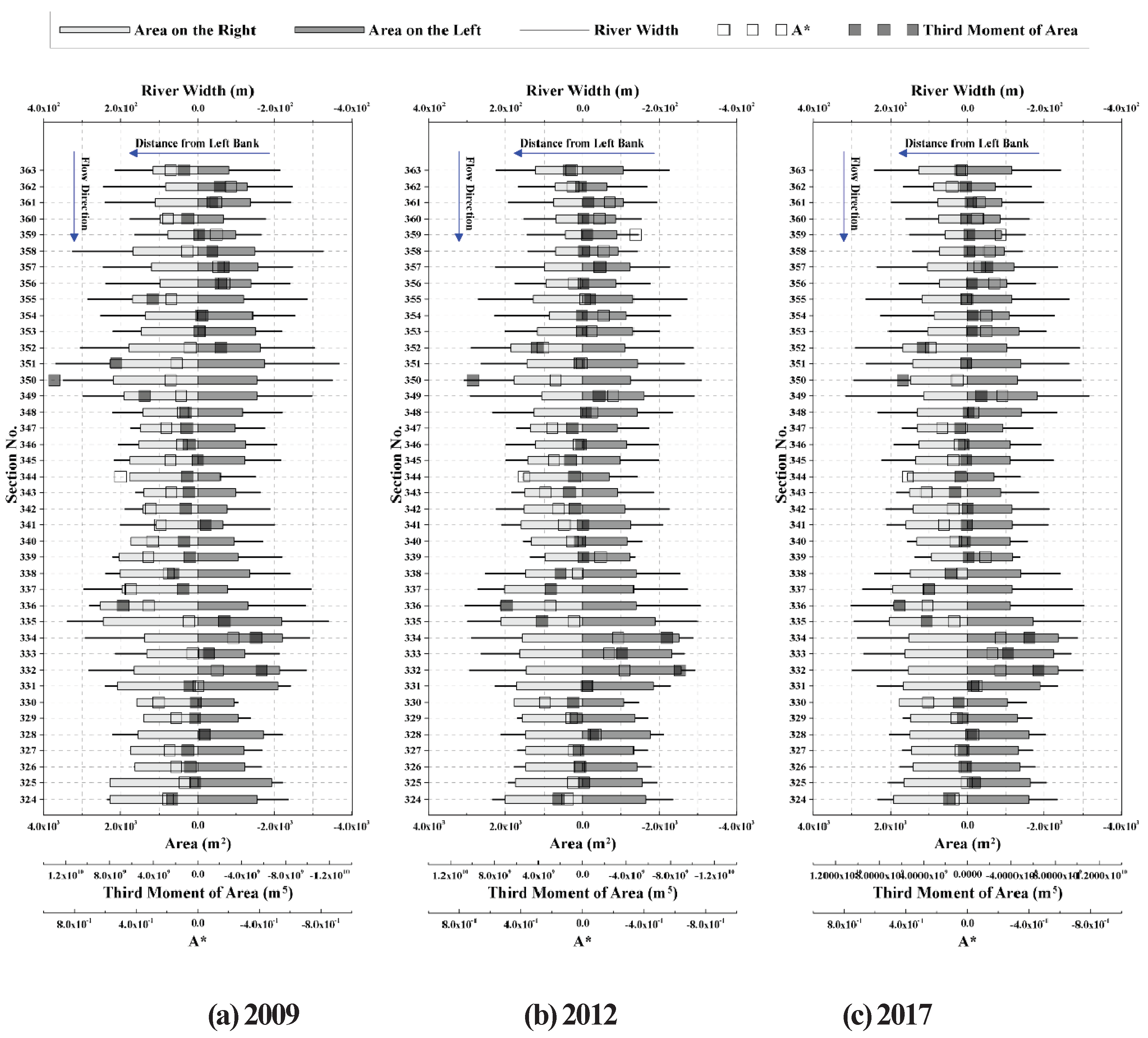

The third-order moment (M3) is a high-order indicator that quantifies the asymmetry of a cross-section, sensitively reflecting the imbalance of mass distribution relative to the distance from the main channel center. In this study, the directionality and intensity of the asymmetric morphology were analyzed by comparing M3 with the Asymmetry Index (A*). The results, as shown in

Figure 5, demonstrate that the longitudinal distribution of M3 and the behavior of A* are almost perfectly aligned.

Because the third-order moment involves the cube of the distance (x^3), it captures subtle topographical changes at the sectional fringes or imbalances caused by localized scour and deposition much more sensitively than the first or second-order moments. Reaches where both M3 and A* exhibit positive values (e.g., Sections 331–335) indicate asymmetric sections where the right bank area is dominant. Conversely, negative values (e.g., vicinity of Section 350) signify a skewness toward the left bank.

Notably, as the absolute values of A* and M3 increase, the intensity of sectional asymmetry becomes more pronounced, making this a highly effective tool for diagnosing biased flow patterns and bed elevation changes in river bends. Consequently, it was confirmed that the third-order moment is a key indicator that transcends simple geometric description to quantitatively track the spatial bias of erosion and deposition processes.

3.1.4. Characteristics of Bed Material and Flow Regime

To understand the morphological evolution of river cross-sections and the spatial variability of the moment-based indicators, bed material size distribution and hydrological characteristics were analyzed as boundary conditions. According to the median grain size (D50) distribution (

Table 1), most sections consist of sandy beds ranging from 0.1 to 0.8 mm. However, significantly coarser sediments were observed at specific locations, such as Section 329 7.6 mm and Section 347 (17.0 mm). Such localized increases in grain size indicate that the riverbed in these sections is either physically armored or possesses high hydraulic resistance, acting as a physical constraint that suppresses abrupt fluctuations in M2 and M3 or limits sectional development in specific directions.

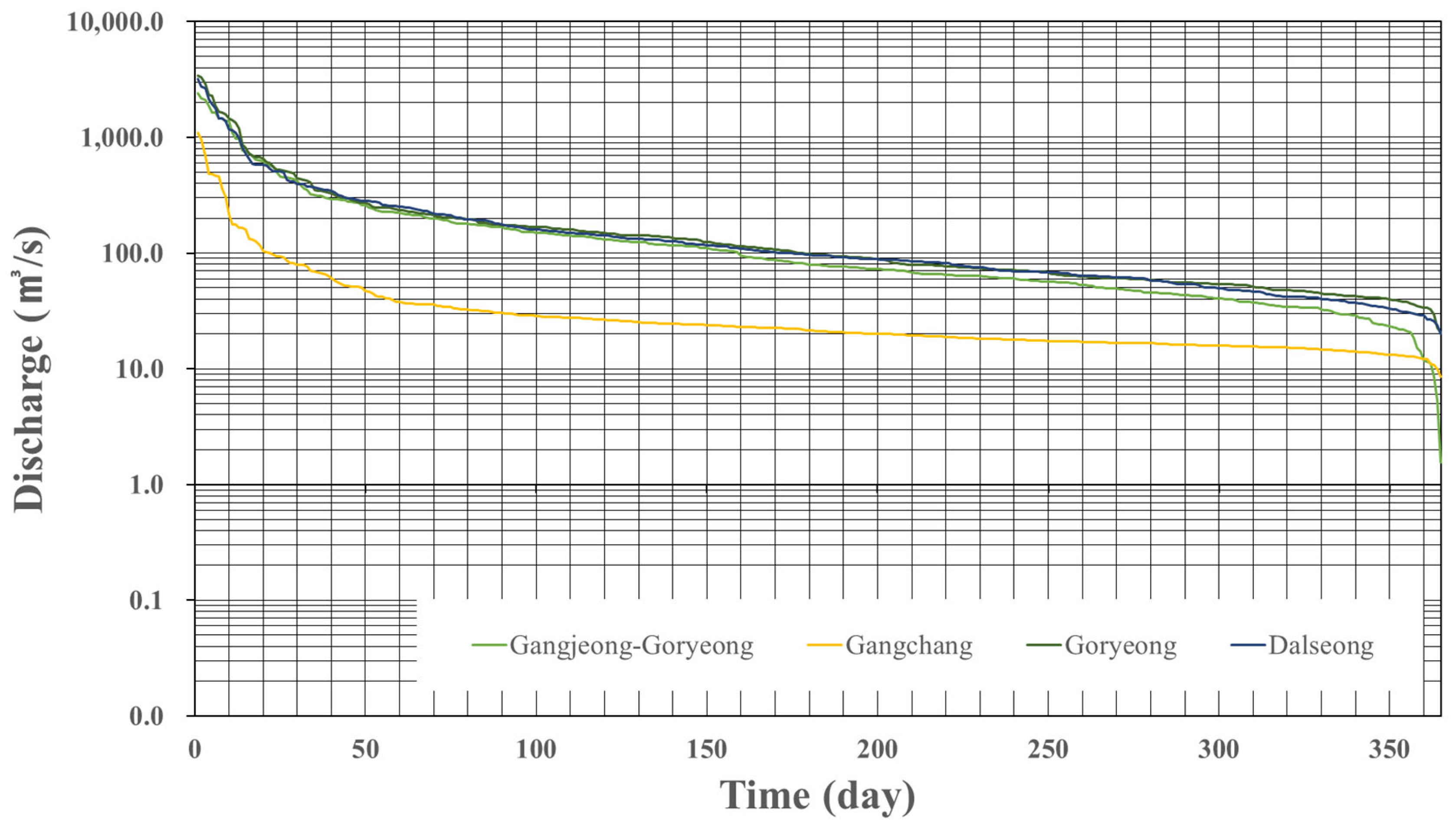

Furthermore, according to the 2018 flow data (

Table 2) and the flow duration curve (

Figure 6), the study reach maintains a stable water supply throughout the year, with an average discharge of approximately 175 to 207 m3/s continuously exerting hydraulic forcing on the channel. The shape of the flow duration curve, in particular, demonstrates that the river possesses a dominant hydrological driver that induces channel widening (M2) and thalweg migration (M1, M3) through constant flow energy as well as seasonal flood variability. These bed material and hydrological characteristics support the conclusion that the geometric moment indicators are not merely numerical changes but the result of combined physical environments and hydrodynamic responses of the actual river.

3.2. Analysis of Hydro-Morphological Interactions

3.2.1. Spatial Alignment Between Velocity Core and Thalweg

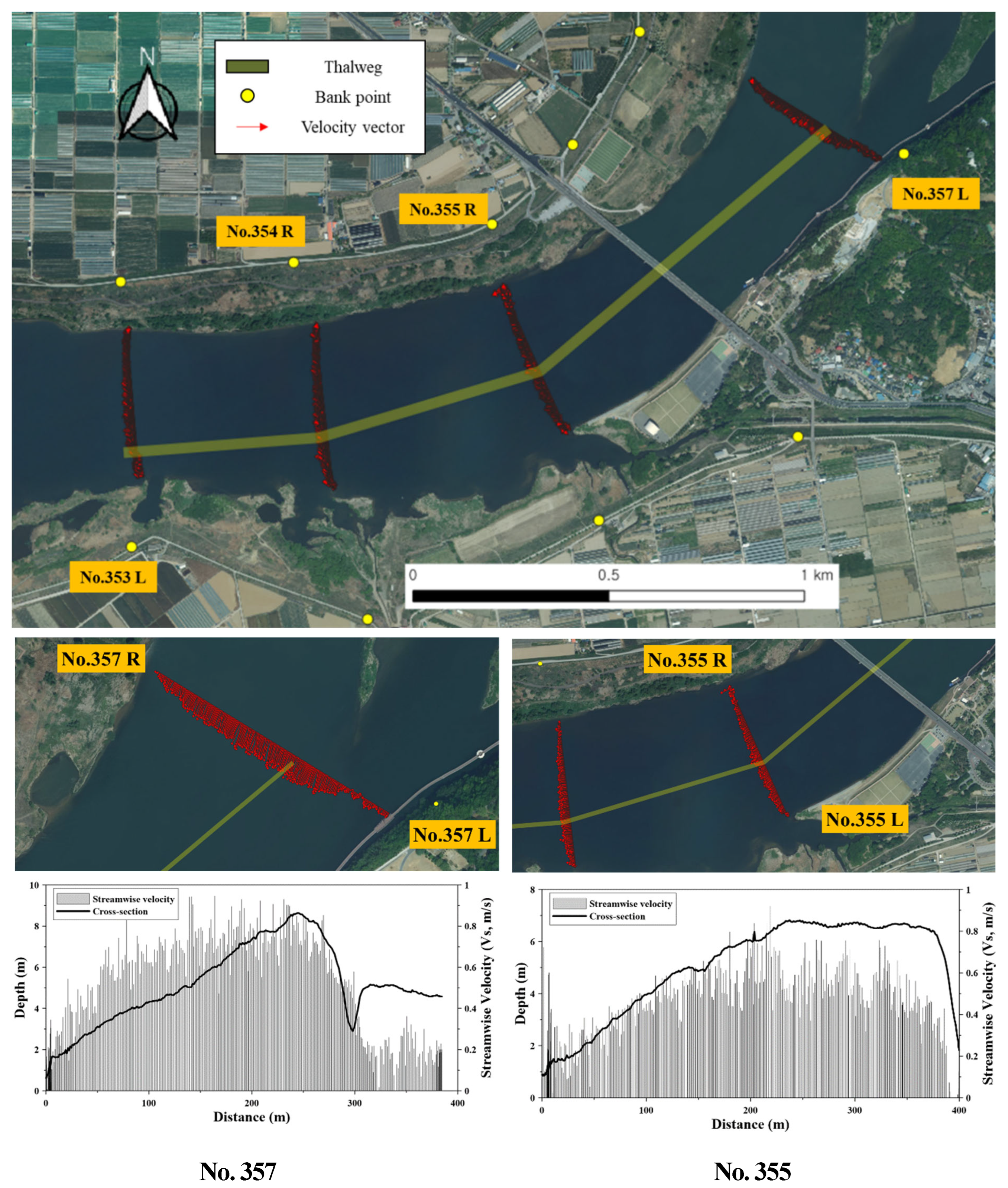

To understand the interaction between the hydraulic energy center and the lowest topographic point of the river, the distribution of streamwise velocity (Vs) measured by ADCP was compared with the location of the thalweg. Although velocity measurements were conducted at selected representative transects, the analysis focused on contrasting the behaviors in straight and curved reaches.

The results revealed that the spatial alignment between the velocity core and the thalweg varied significantly depending on the channel planform. In Section 357 (

Figure 7(b)), which maintains a relatively straight alignment, high-velocity zones were concentrated near the thalweg where the maximum depth occurs, indicating a high degree of hydro-morphological alignment. This suggests that the bed topography and flow energy maintain an equilibrium state under stable flow conditions.

In contrast, in Section 355 (

Figure 7(c)), which is influenced by channel curvature, a discrepancy was observed where the locations of the maximum velocity and the thalweg were horizontally separated. The velocity peak appears at a position slightly offset from the deepest part of the section. This is interpreted as a result of centrifugal forces, secondary flows, or the inertia of the flow from upstream interacting with the sectional asymmetry. Such hydro-morphological misalignment can accelerate bed scour in specific directions and drive the unbalanced development of the channel profile.

To understand the interaction between the hydraulic energy center and the lowest topographic point of the river, the distribution of streamwise velocity (Vs) measured by ADCP was compared with the location of the thalweg. Although velocity measurements were conducted at selected representative transects, the analysis focused on contrasting the behaviors in straight and curved reaches.

3.2.2. Relationship Between Sinuosity and Morphological Indicators

The planform sinuosity of a river is a primary factor determining the distribution of flow energy, inducing asymmetry in the hydraulic forcing exerted on the riverbed and banks. In this study, the survey reach was divided into three distinct reaches to calculate the sinuosity index (S) (

Table 3), and the influence of these planform geometries on the moment-based morphological indicators (M1, M2, M3) was examined. Generally, a river is classified as a meandering river when its sinuosity is 1.5 or higher (Leopold and Wolman, 1957). The upstream reach of this study (Sections 363–350) exhibited distinct meandering characteristics with S=1.67.

The analysis revealed that in the upstream reach with the highest sinuosity (Sections 363–350, S=1.67), the fluctuations in the third-order moment (M3) and the Asymmetry Index (A*) were most pronounced. This is attributed to the localization of hydrodynamic loads driven by flow inertia and centrifugal force, suggesting that intense curvature promotes the development of sectional asymmetry. In contrast, in the relatively straight reach with lower sinuosity (Sections 349–339, S=1.11), the deviation between the first-order moment and the centroid decreased, and the second-order moment (M2) remained highly consistent with the W/D ratio, indicating a more stable sectional geometry.

These findings demonstrate that the planform alignment of a river is a primary driver governing the statistical moment distribution of its cross-sectional geometry. Specifically, higher sinuosity leads to a greater imbalance in hydraulic forcing, which acts as a morphological process that distorts sectional dispersion (M2) and intensifies asymmetry (M3).

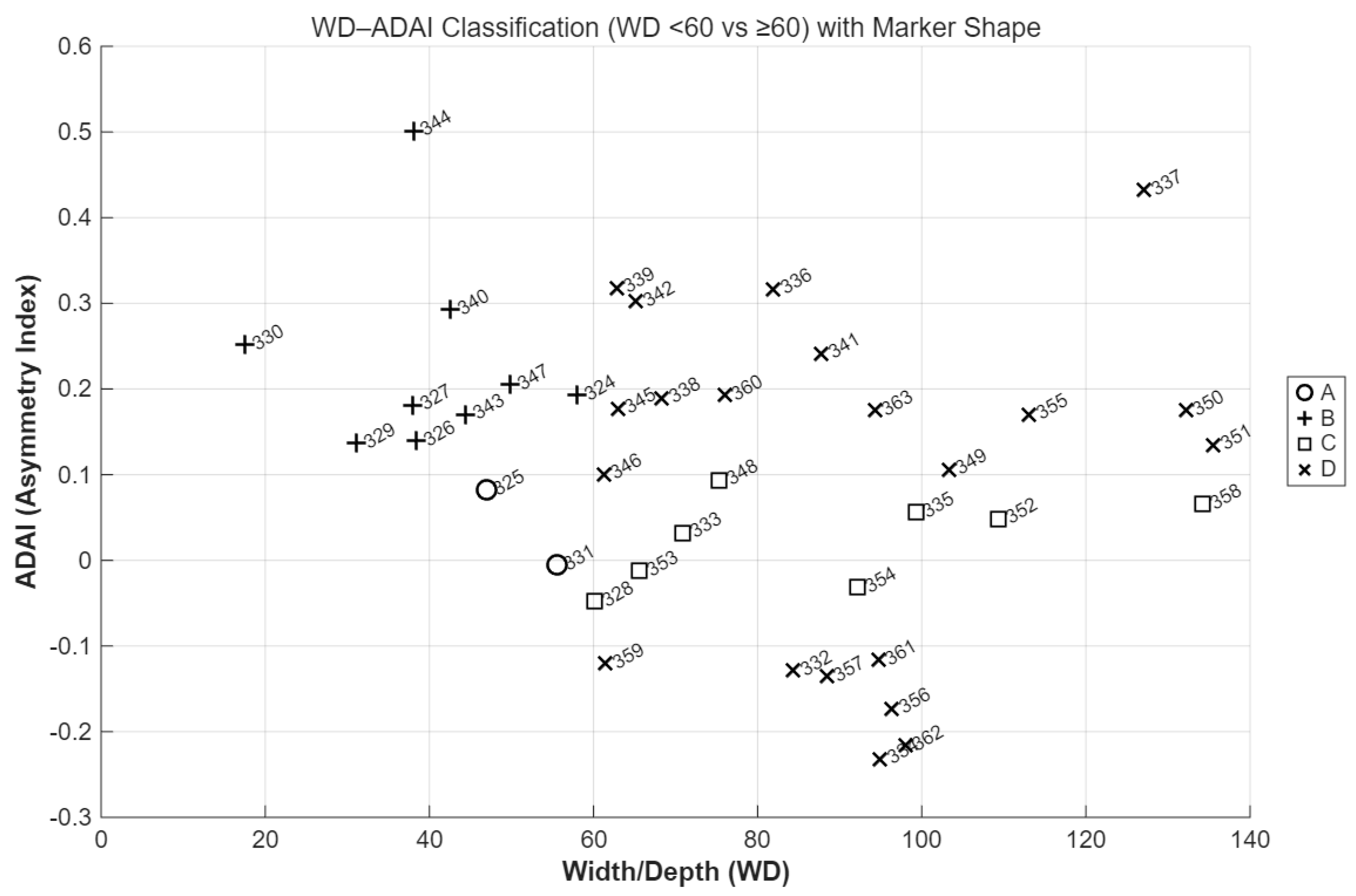

3.2.3. Quadrant Analysis of W/D Ratio and Asymmetry

To comprehensively diagnose the morphological stability and hydraulic characteristics of the river sections, a quadrant analysis was performed by combining the Width-to-Depth ratio (W/D) and the Asymmetry Index (ADAI) (

Figure 8). The thresholds were set at W/D=60 and |ADAI|=0.1, considering the specific characteristics of the study reach.

The analysis revealed that a significant number of sections are distributed in regions where W/D > 60 and asymmetry is pronounced (top and bottom right quadrants). Specifically, sections with |ADAI| > 0.1 suggest a high probability of ongoing lateral erosion or bed scour due to the localization of hydraulic forcing on one bank, indicating a state of hydraulic instability. Conversely, sections within the range of |ADAI| < 0.1 (e.g., Sections 325, 331) are interpreted as stable reaches that maintain a relatively symmetrical profile and a balanced flow distribution.

Reaches with exceptionally high W/D and large asymmetry (e.g., vicinity of Sections 350, 351) can be classified as vulnerable zones where rapid channel shifts may occur during floods due to shallow depths and biased flow patterns. In conclusion, this quadrant analysis transcends simple geometric classification, serving as a quantitative tool to identify ‘hydraulically unstable reaches’ that require intensive monitoring for river management and maintenance.

4. Conclusions

This study employed geometric moment techniques to quantify the morphological evolution and hydraulic characteristics of river cross-sections, diagnosing dynamic channel stability by integrating planform sinuosity and flow conditions. Through a comprehensive analysis of the first, second, and third-order moments, Width-to-Depth (W/D) ratio, sectional asymmetry (A*), and the thalweg-velocity relationship, the following primary findings were obtained.

First, the moment-based approach precisely quantified irregular sectional variations that are difficult to capture using traditional W/D ratios or simple depth measurements, by utilizing the centroid deviation (M1), area dispersion (M2), and mass distribution bias (M3). Interpreting geometric changes from the perspective of mass distribution provides more valuable information for tracing the hydraulic drivers of morphological shifts.

Second, the sinuosity (S) analysis revealed that reaches with higher curvature (S ≥ 1.5) exhibited a sharp increase in the variability of the third-order moment and asymmetry indicators due to imbalances in hydraulic forcing. Specifically, by proving the horizontal separation between the velocity core and the thalweg in curved reaches, this study identified that planform complexity is a key mechanism intensifying geometric imbalance and hydraulic instability.

Third, the quadrant analysis of W/D and asymmetry categorized the morphological types of the entire reach and identified hydraulically vulnerable zones requiring intensive monitoring.

In conclusion, the hydro-morphological indicators proposed in this study provide a systematic framework for the integrated diagnosis of river topography and flow trends beyond individual shape characterization. This analytical system is expected to serve as a scientific decision-making tool for future river management and restoration planning.

Funding

Please add: This research was supported by the Korea Environmental Industry & Technology Institute (KEITI) through the Project “Smart Web-based Data Platforms for Integrated Management of Water Quality and Flow Rate”, funded by the Korea Ministry of Climate, Energy and Environment (MCEE) (Project No. 2480000423, IRIS No. RS-2021-KE001623, K-IRIS No. 20250101-001).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Changwon National University for sharing the experimental data used in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Leopold, L. B., & Maddock, T. (1953). The hydraulic geometry of stream channels and some physiographic implications (Vol. 252). US Government Printing Office. [CrossRef]

- Williams, G. P. (1978). Bank-full discharge of rivers. Water Resources Research, 14(6), 1141-1154.

- Langbein, W. B. (1964). Geometry of river channels. U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 422-S.

- Rosgen, D. L. (1994). A classification of natural rivers. Catena, 22(3), 169-199.

- Rosgen, D. L. (2001, March). A practical method of computing streambank erosion rate. In Proceedings of the Seventh Federal Interagency Sedimentation Conference (Vol. 1). Reno, NV: Subcommittee on Sedimentation.

- Knighton, A. D. (1981). Asymmetry of river channel cross-sections: Part I. Quantitative indices. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms, 6(6), 581-588. [CrossRef]

- Xu, L., Jiang, E., Zhao, L., Li, J., Zhao, W., & Zhang, M. (2022). Research on the asymmetry of cross-sectional shape and water and sediment distribution in wandering channel. Water, 14(8), 1214. [CrossRef]

- Falcon, M. A. (1979). Flow and bed topography in alluvial channel bends. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA.

- Falcon, M. A., & Kennedy, J. F. (1983). Flow in alluvial-river curves. Journal of Fluid Mechanics, 133, 1-16.

- Zimmermann, C., & Kennedy, J. F. (1978). Transverse bed slope in curved alluvial channels. Journal of the Hydraulics Division, 104(1), 33-57.

- Odgaard, A. J. (1981). Transverse bed slope in alluvial channel bends. Journal of the Hydraulics Division, 107(12), 1677-1694. [CrossRef]

- Odgaard, A. J., & Kennedy, J. F. (1982). Analysis of Sacramento River bend flows, and development of a new method for bank protection (No. IIHR241). Iowa Institute of Hydraulic Research.

- Lee, C.J., Kim, W. Kim, C.Y., & Kim, D.G. (2009). Measurement of velocity and discharge in natural streams with the electronic float system. KSCE Journal of Civil and Environmental Engineering Research, 29(4B), 329-337, . [CrossRef]

- Jeong, C. (2014) Development of Method for Acquisition of 3-Dimensional River Geographic Information Using R2V2 and UAV. Journal of korean society of hazard mitigation., 14(3) , 269~275. [CrossRef]

- Ko, J. S., Kwak, S., Lee, K., & Lyu, S. (2019). A study on morphological characteristics of large river channel based on bathymetry and near-river survey. Journal of Korea Water Resources Association, 52(2), 163-172.

- Ko, J. S., Lee, K., Kwak, S., & Lyu, S. (2020). Analysis of bed change based on the geometric characteristics of channel cross-sections. Journal of Korea Water Resources Association, 53(12), 1097-1107.

- Dixon, S.J., Sambrook Smith, G.H., Best, J.L., Nicholas, A.P., Bull, J.M., Vardy, M.E., Sarker, M.H., Goodbred, S., (2018). The planform mobility of river channel confluences: Insights from analysis of remotely sensed imagery. Earth-Science Reviews, 176, 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Formann, E., Habersack, H. M., & Schober, St., (2007). Morphodynamic river processes and techniques for assessment of channel evolution in Alpine gravel bed rivers. Journal of Geomorphology, 90(3-4), 340-355. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport. (2013). Basic River Plans for the Nakdong River. (in Korean).

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport. (2012). Research Report on Monitoring and Manual Preparation for the Four Major Rivers Project (Riverbed Change). (in Korean).

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport. (2009). Basic River Plans for the Nakdong River. (in Korean).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).