1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Smallholder farmers in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) face the twin challenges of declining soil fertility and food insecurity [

1]. The major cropping systems for these farmers include maize, millet, sorghum, and cassava. Agricultural production in SSA is adversely affected by erratic rainfall, prolonged dry spells, and increased temperatures [

2]. Maize is the dominant food crop in Africa, but serious technological intervention is urgently needed to reverse declining productivity. Maize production in SSA has been generally low and stagnant since the late 1990s. Vulnerability to food insecurity is growing, and annual access to food is stretching the coping capacity of many smallholders who farm on less than two hectares. Although fertilizers are almost universally recommended, they are perceived as expensive and inaccessible for smallholders [

3,

4]. Hence, many farmers in SSA are seeking low-cost practices to augment soil fertility and arrest declining crop output. Maize-legume systems have become a viable option for providing the interventions needed to address the above-mentioned challenges. The efficacy of conventional maize–legume systems in addressing these problems has been the subject of intensive scientific and policy scrutiny [

5]. These agro-ecological maize–legume systems now constitute the focus of a systematic synthetic review [

4]. Generally, more legume cropping options are reported, and significant evidence and scholarly attention have accumulated. However, scant attempts have been undertaken to collate and empirically characterize the knowledge on the benefits and trade-offs of these agro-ecological systems [

5,

6,

7,

8].

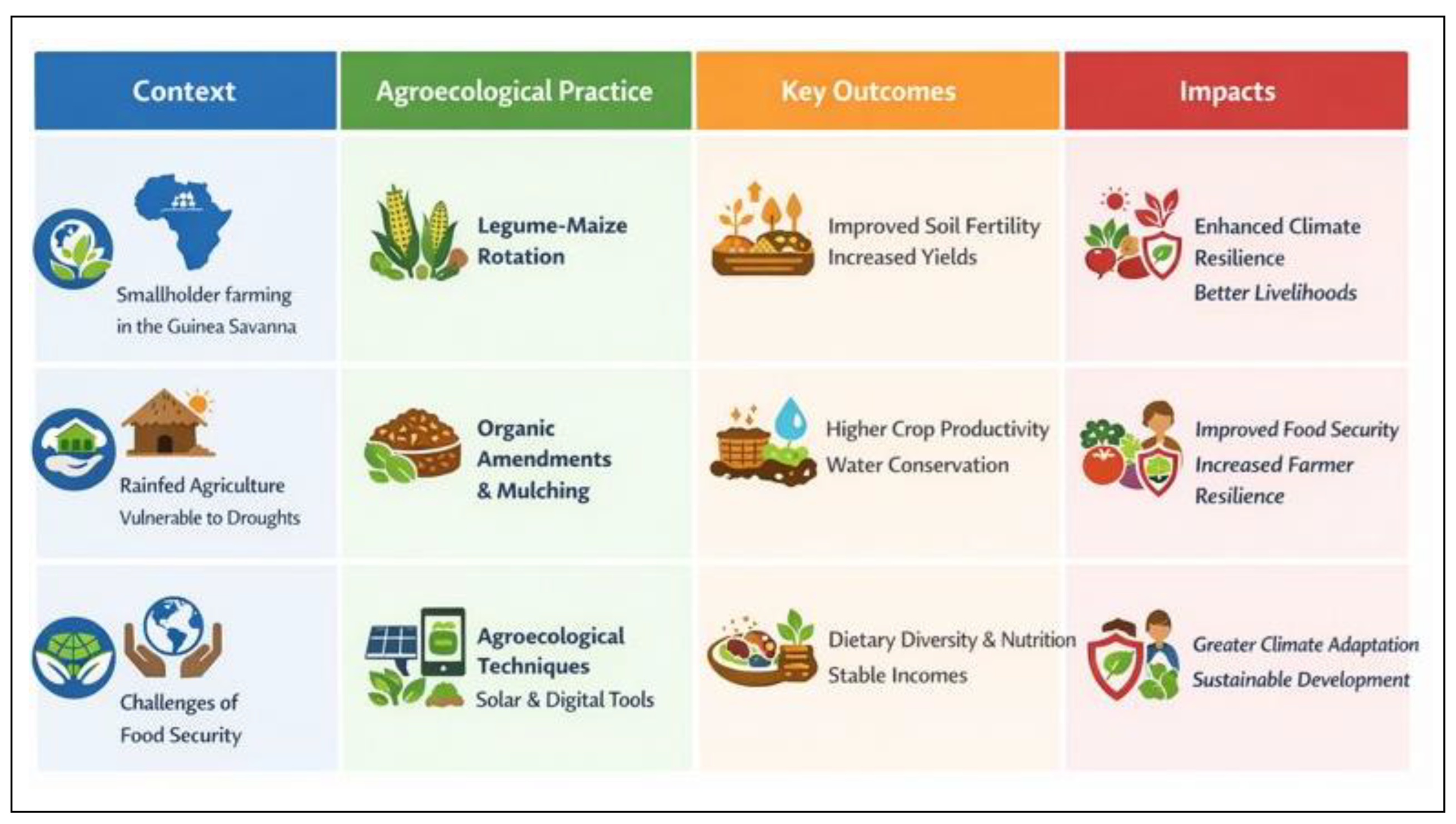

Food security is essential for sustainable development, and it is often stated that climate-resilient agricultural systems are required to achieve this goal in Sub-Saharan Africa. Recent calls for regenerative agriculture emphasise an agroecological approach and provide a new development pathway to achieve synergistic benefits for food security and climate resilience [

7]. A systematic review was conducted to synthesise evidence on the components, biophysical and socioeconomic contexts, and impacts of maize–legume systems that incorporate agroecological principles. Specific attention is given to their effects on soil fertility and soil health, climate resilience, and smallholder food security and livelihoods [

9,

10,

11].

The evidence highlights the potential of maize–legume systems to improve food security and climate resilience of smallholder farmers in Sub-Saharan Africa while regenerating degraded soils. Optimised designs combining legume species with deep- and shallow-rooted maize varieties can improve soil fertility [

12]. Managing legume residues plays a key role in enhancing soil organic matter and structure, increasing moisture retention capacity, reducing surface runoff, and providing essential nutrients. Crop diversity, rotations, and cover crops enhance pest and disease regulation, and the multiplication of fodder banks, cash crops, and small ruminants generates new market opportunities and improves risk management [

13]. Pests, diseases, and inadequate access to high-quality seed hinder adoption, and scaling successful experiences supports learning and knowledge exchange [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14].

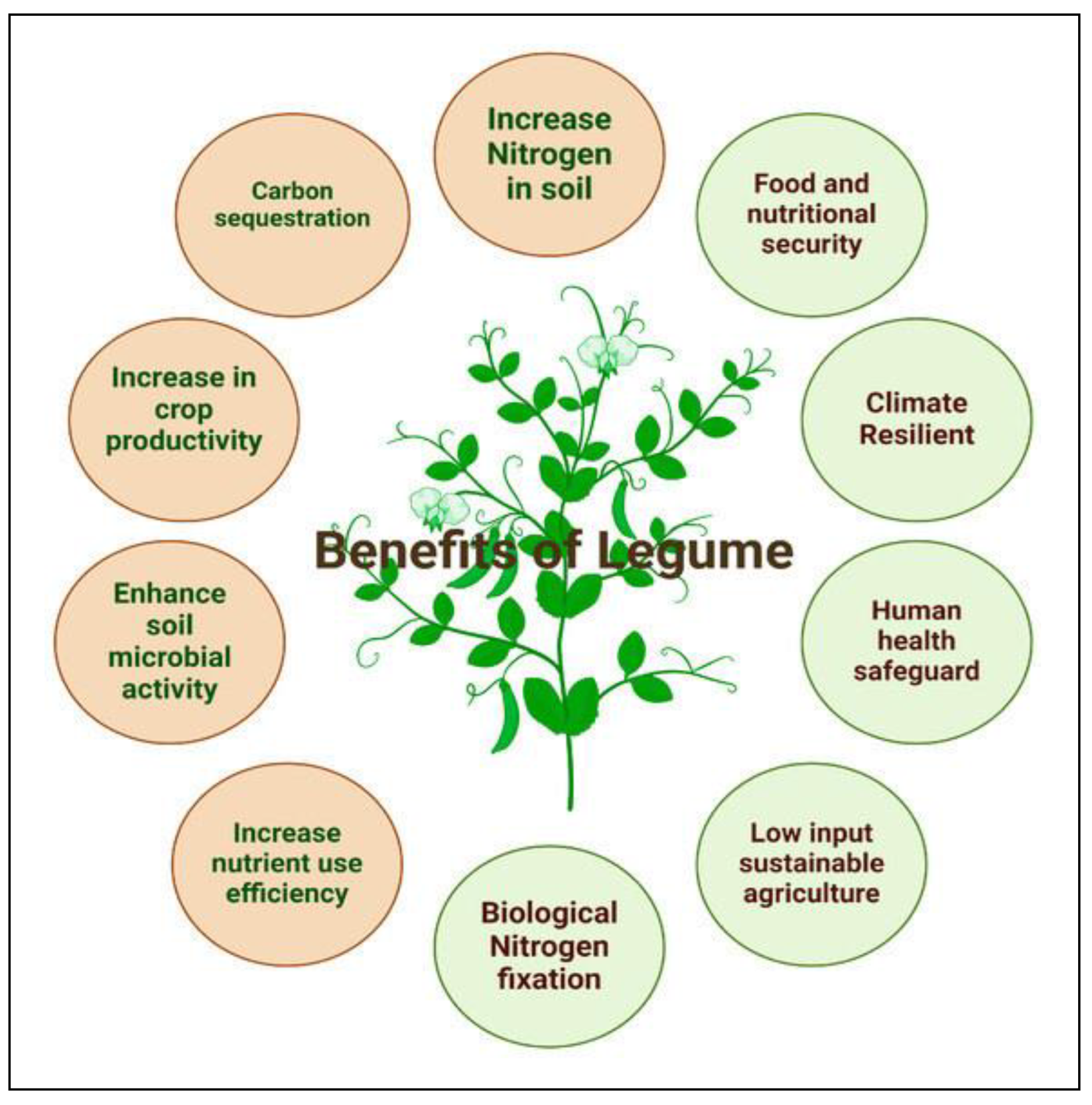

Agroecological maize–legume systems are receiving renewed attention as a strategy to improve soil fertility, climate resilience and food security among smallholder farmers in Sub-Saharan Africa. Agroecological systems combine sustainable, low-cost management practices to increase productivity and resilience without reliance on industrial inputs such as synthetic fertilisers or pesticides [

12]. Maize-legume practices are the most widely studied agroecological interventions in Sub-Saharan Africa. Legumes offer multiple agronomic benefits, including Biological Nitrogen Fixation, improved soil structure and organic matter accumulation. Maize-legume systems are also associated with increased earnings and food security [

3]. Sub-Saharan Africa is home to four of the five top food security hotspots and has the largest number of undernourished people globally. The urgent need to improve smallholder food security is compounded by rapid population growth and a changing climate. Overall, maize-legume systems offer opportunities for smallholder farmers to improve soil fertility, increase climate resilience and enhance food security [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16].

Land degradation due to soil nutrient depletion and erosion is on the rise in Africa. Increased fertiliser prices and limited access to credit have reduced the use of inorganic fertilisers among smallholder farmers. This has led to renewed interest in alternative soil fertility options. Maize is the staple food crop of southern and eastern Africa [

13]. Maize-legume systems can support sustainable intensification of maize production while addressing soil fertility constraints. Researchers have documented a diverse range of legume species and system configurations. From 2004–2013, over 56,000 records in Africa referred to maize–legume systems for biological nitrogen fixation and food security over six continents [

14]. Sub-Saharan Africa remains the most food-insecure continent, with four of the five most significant food security hotspots. Two hundred eighty-two million people are undernourished in Sub-Saharan Africa. Improved climate resilience and food security are critical in Africa, where drought is the primary driver of food insecurity [

19,

20,

21,

22].

Declining soil fertility is one of the main drivers of declining maize yields in southern Africa, where maize and legumes occupy more than 50% of the cultivated area and maize contributes more than 60% of cereal calories [

23]. Maize yields are well below the potential (6.5 t/ha) targeted by The Africa Union through the Framework of the Comprehensive African Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP). Maize–legume systems improve soil fertility and enable resource-poor farmers to have greater assurance of food security. Legume intercropping is being promoted among the four main maize–legume systems (maize with groundnut, pigeon pea, cowpea, and soybean). However, legumes such as field peas, dry beans, and dwarf legumes, such as mucuna, are also used in southern Africa [

24]. Maize–the Southern African Development Community supports legume systems; in Botswana, Malawi, and South Africa, legumes also help to recover the yield decline that follows a switch between maize varieties, a common practice to counteract changing weather conditions. Maize–legume systems are part of the repositioning of the Green Revolution in Africa; they address the challenge of climate change, although the greenhouse gas emissions associated with their cultivation remain poorly studied [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29].

1.2. Rationale of the Study

Intercropping maize with legumes provides a pathway for ecological intensification and generates a range of agronomic, economic, and environmental benefits that are critical for achieving food and nutrition security in high-risk environments. Diverse evidence, spanning biophysical interactions to food security outcomes, has been documented across farming contexts in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) [

27]. However, while a case has been made for diversification as a broader strategic approach, the nature and scope of the impacts of maize–legume systems specifically have not been systematically synthesised [

28]. A complete systematic review has, therefore, been undertaken to distil lessons from existing evidence supporting the scaling of maize–legume systems that reflects the growing recognition of the need for more diverse, climate-resilient practices to support the climate adaptation of smallholder farmers [

30,

31].

Intercropping maize with legumes supports a range of agroecological outcomes in Sub-Saharan Africa. Empirical evidence already points to benefits across diverse biophysical and socio-economic conditions [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]. In view of maize’s importance for food security, plant health, soil fertility, and livelihood enhancement, further evaluation of maize–legume systems across the diverse meta-region of SSA can help determine the nature of the evidence regarding their contribution to more sustainable, equitable production systems. Smallholders account for more than 80 per cent of farmers in SSA, and maize is the staple for at least 25 countries in the region—providing an essential focus for scaling sustainable intensification practices to secure food and nutrition [

32].

In Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), most agriculture depends on smallholder farmers, who rely primarily on soil fertility to enhance productivity. Most farmers do not use fertilisers and instead apply traditional soil-enrichment techniques, such as manure, crop rotation, and fallows. Soil productivity is declining due to the growing human population and continual cropping [

11]. Sufficient nutrients and organic matter are critical to reversing soil loss. Agroecological intensification promotes systems such as maize–legume intercropping to recycle nutrients and boost farming systems’ resilience to climate change. Farm residues that decay also restore soil organic matter, increasing soil structure [

33]. SSA is experiencing the adverse effects of climate change, and climate events critically influence maize production. Low- and middle-income countries are at most significant risk of food shortages under adverse weather patterns. Maize remains a key crop in SSA for food, income and trade [

34]. Agroecological intensification has the potential to improve soil fertility, farming resilience and farm productivity, but is not universally adopted. Thus, a systematic synthetic review helps clarify what is known and unknown about maize–legume systems and addresses the information gap regarding potential benefits and drawbacks from past experiences [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35].

2. Literature Review

Sub-Saharan Africa faces significant challenges to food security, especially in the context of climate change and demographic growth [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Smallholder farmers dominate the agricultural landscape, yet rising population density threatens to degrade the natural resource base upon which food production depends [

36]. Overcoming the constraints imposed by these pressures requires innovative agricultural systems that are both productive and resource-conserving [

37]. Agroecological interventions, particularly maize–legume cropping systems, have emerged as a promising strategy by enhancing productivity, improving soil fertility, and increasing climate resilience.

2.1. Contextual Landscape: Sub-Saharan Africa, Smallholders, and Food Security

Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) harbours the world’s largest population of smallholders, with 70% of the rural poor and an alarmingly high prevalence of undernourishment, especially among children. Climate variability, including an increase in the frequency and intensity of droughts, is considered a significant contributor to low food security [

1]. Strikingly, half of the smallholders live less than 30 minutes away from a market, underscoring the important of analysing agroecological maize–legume systems in SSA to enhance smallholder food systems [

4,

36].

Accessible agro-ecologies in SSA are predominantly tropical, characterized by a single wet season and large interannual variability in rainfall together with median temperatures around 21–25 °C, restricting plasticity in farming systems. Smallholders make up 80% of all farms in the SSA region where cropped land averages under 2ha per household. The land-planning myopia of mainstream development models has caused an imbalance between these smallholders’ own information-generation processes and institutional evaluation procedures, leading to considerable and unjustifiable uncertainty about the applicability of crop technologies. Nigeria, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Madagascar, and Kenya are critical because together they account for an estimated 46% of the region’s maize production [

5].

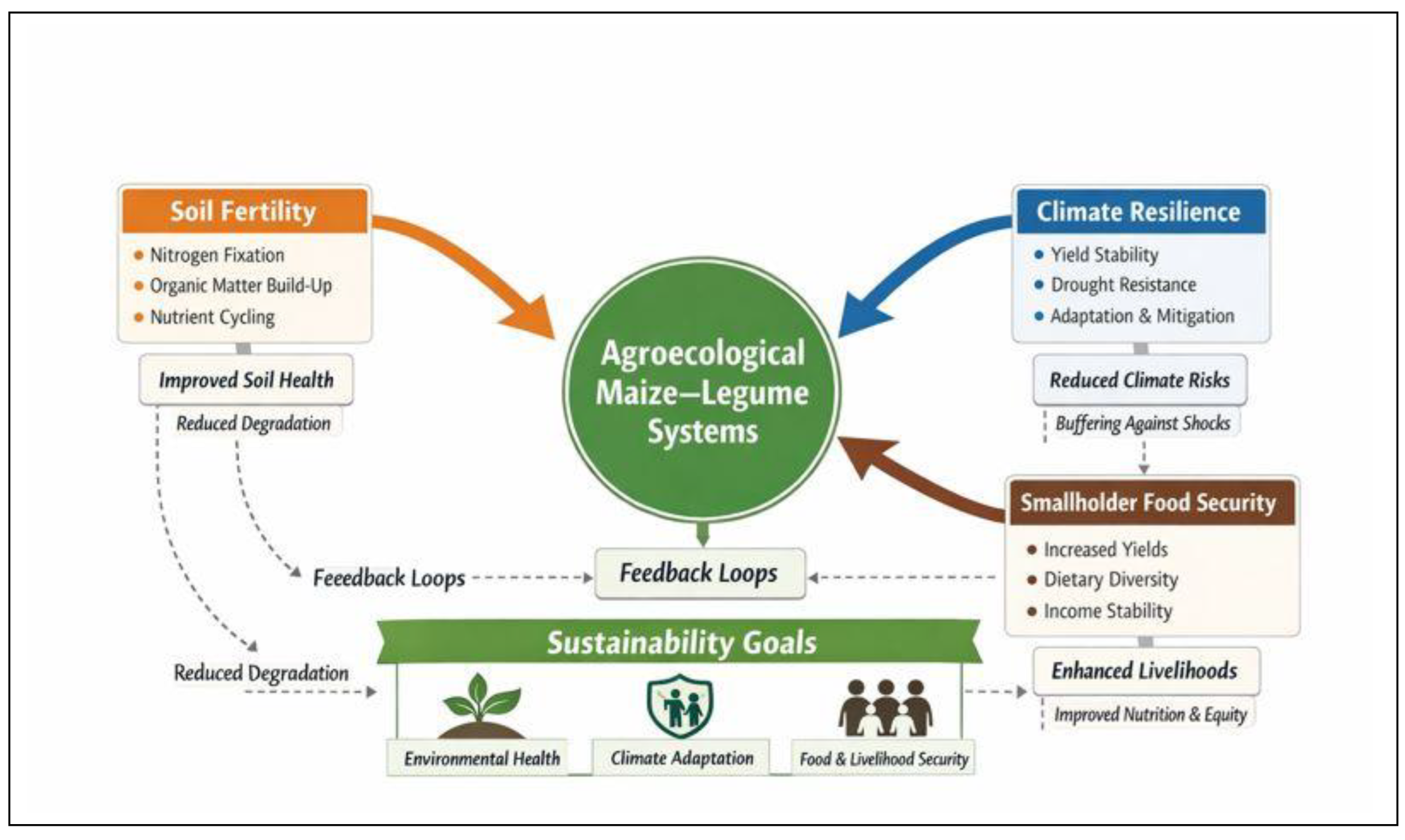

2.2. Agroecological Mechanisms Driving Soil Fertility

Legumes are used in smallholder agricultural systems in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) for various purposes, including grain, fodder, cover crops, soil fertility improvement, and weed suppression. They are relied upon, particularly as cover crops and for improving soil fertility, because of household and market constraints that prevent other options. Agroecological maize–legume systems primarily use legumes to address declining soil fertility. Seven agroecological mechanisms identified across the maize–legume systems in Africa drive soil fertility improvement [

1,

6,

7]. First, legumes fix nitrogen (N) symbiotically from the atmosphere, thereby enhancing soil N availability for subsequent maize and legume crops.

This benefit is especially crucial when soil fertility degradation limits access to mineral fertilisers and relatively few other low-external-input options are available. Second, highly complementary maize–legume N synergisms occur, as maize improves legume N2 fixation and growth. In contrast, legumes enhance maize N uptake through various mechanisms (slow-release N in litter, improved rooting, better soil-water conservation, and reduced pest damage). Third, legumes enrich organic matter inputs, improving soil structure, reducing unproductive water infiltration, aeration, and root penetration, and increasing the availability of N by stimulating a range of microbial activity.

Fourth, legume roots and residues mobilise and provide additional micronutrients, hence supporting subsequent maize [

37,

38,

39,

40]. Fifth, legumes suppress pests and, through reduced pest damage, mitigate declines in crop productivity from N loss, thereby tilting input–output economic ratios upward. Finally, timely shallow tillage or mulch management of legume residues—particularly the soil-covering stems—enhances the capture of moisture from crop-causing rainfall by 50–70%. Such moisture-preventing maize–legume intercropping partly offsets the critical limitation of market access to low-interest smallholder credit, enabling the external purchase of economic substitutes such as mineral fertilisers [

41].

2.3. Climate Resilience and Adaptation Pathways

Agroecological maize–legume systems are expected to improve not only soil fertility but also climate resilience. Systems that combine maize with grain legumes offer several benefits relevant to climate risks prevalent in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). First, maize–legume systems can enhance drought tolerance, an urgent need among farmers facing increasingly erratic rainfall patterns. Maize plants growing under intercropping conditions, for example, can maintain soil moisture after rainfall events, leading to increased water retention and reduced water loss [

8]. Second, maize–legume systems can help stabilise maize yields and enhance productivity under climate-non-normal conditions, such as delayed rainfall onset or poor distribution throughout the cropping season.

Across multiple SSA agroecologies, maize yields have been observed to improve when intercropped with legumes compared with monoculture yields under low precipitation scenarios [

9]. Third, farmers can pursue climate-resilient maize–legume pathways even in the face of reduced fertiliser application, whether due to rising prices or unavailability. Several studies have documented maintenance, and even increases, in maize yield when maize is intercropped during seasons when chemical fertiliser use is low or zero. Fourth, maize–legume systems can mitigate production risk by diversifying farmers’ cropping portfolios through the introduction of legume crops [

42].

2.4. Impacts on Smallholder Productivity and Food Security

Agroecological maize–legume systems can benefit smallholders through increased crop productivity and food security—maize–legume intercropping yields higher maize and legume yields than growing maize alone. A meta-analysis shows average increases in maize yield of 29% and in legume yield of 94%, with similar gains expected for other systems [

10]. Farming systems remain productive partly because of free and locally available resources, while monocultures often face crop-degrading pests and diseases [

1].

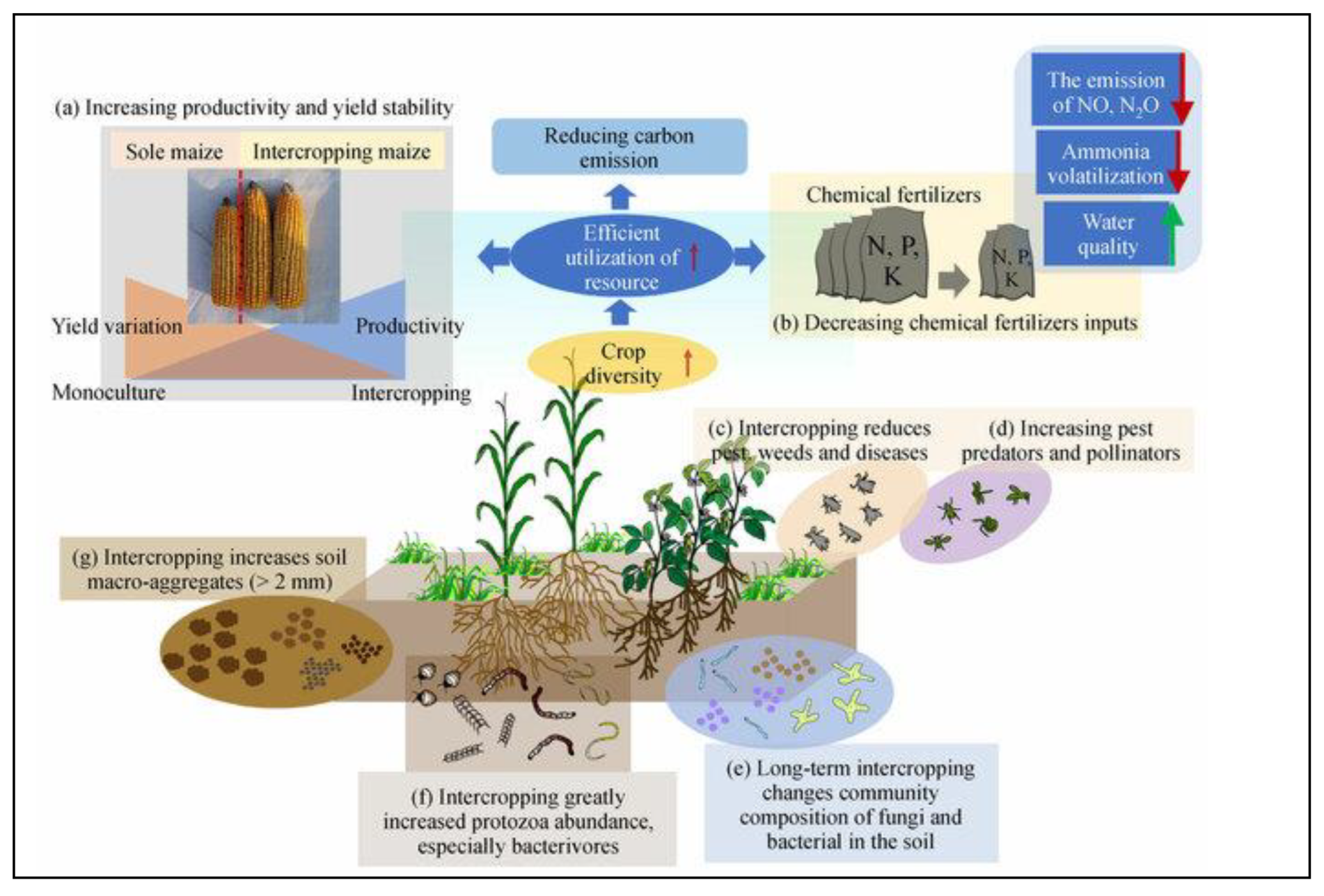

Diverse evidence indicates that agroecological maize–legume systems enhance smallholder crop productivity and food security across Sub-Saharan Africa. Average legume yields increase substantially when included in maize cropping systems. Other types of maize cropping systems do not yield the same average or marginal benefit at the same level of input or management support (

Figure 1). Overall, an agroecological maize–legume system is considered more effective at promoting smallholder food security than monocultural maize [

8].

2.5. Socioeconomic and Policy Dimensions

Ecosystem-based agroecological principles can facilitate long-term improvements in soil fertility in smallholder maize–legume systems throughout Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Numerous biogeochemical processes underpin these effects, encompassing biological nitrogen fixation (BNF), soil organic matter (SOM) accumulation, enhanced resource-use efficiency, and modulation of pest and weed pressures [

41,

42,

43].

Consequently, maize–legume systems can foster Africa’s sustainable intensification—producing more food and livelihoods with a smaller environmental footprint, while safeguarding soil fertility [

1]. They also build climate resilience, enabling adaptation to extreme weather, mediating risks earlier in the crop/fertiliser supply chain, and strengthening food systems against multiple shocks. Owing to these various benefits, evidence of these benefits, investing in complementary agronomic practices, and addressing socioeconomic dimensions emerge as priorities for scaling-out the systems [

2].

2.6. Gaps, Limitations, and Methodological Considerations

A total of 1249 studies from SSA outlining the characteristics and practices of smallholder farming systems were screened, but only 17 provided information on both the socio-economic drivers of broader adoption of intercropping and an analysis of economic livelihood benefits from growing maize and legumes [

9]. Completion of systematic syntheses on specific maize–legume systems (for example, maize–soybean and maize–groundnut) may be appropriate to develop a stronger evidence base.

Addressing context-specificity presents obstacles that further limit comprehensive assessments; since agro-ecological conditions vary widely across SSA, constraints and enabling factors are indeed smallholder context-dependents [

3]. Systems that include legumes either as intercrops or in rotation with maize are widespread throughout SSA and clearly support multiple climate-resilient agriculture pathways (e.g., moisture retention, drought-avoidance mechanisms, restoration of soil organic matter and fertility, and reduction of pest damage), yet systematic syntheses specifically on these maize–legume agro-ecological systems remain limited [

1,

2].

2.7. Theoretical Foundations of Agroecological Maize–Legume Systems

Soils in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) are typically degraded and nutrient-depleted. Theoretical agroecological frameworks argue that organic resource input through plant residues, cover crops, or fertilisers, combined with process-oriented space- and time-efficient management practices, constitutes an essential entry point for restoring soil organic matter (SOM) and, subsequently, achieving multiple research, food security, climatic, and sustainable development goals [

6]. In maize–legume systems within SSA, several key agroecological processes operate to boost nutrient cycling, improve soil structure and hence tilth, enhance water-saving mechanisms, suppress particular biotic crop pests, and ultimately augment crop productivity and food security.

Depending on the precise choice of maize–legume system configuration, the acquired climate-resilience attributes also help mitigate certain precipitation- and temperature-induced shocks to cropping systems [

27,

43]. These diverse agroecological functions solidify SSA maize–legume system configurations as viable pathways towards holistic and sustainable intensification of smallholder farming and, consequently, provide a strong theoretical foundation for reviewing their effects on soil fertility, climate resilience, and food security throughout SSA.

2.7.1. Theoretical Framework

Agroecological maize–legume systems represent a promising production pathway for smallholder farmers across Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) who need integrated solutions to restore soil fertility, build climate resilience, and improve food security [

32]. Historically, much of SSA has cultivated maize under low-input, rain-fed conditions where soils are subject to depletion, degradation, and erosion [

36]. Although maize−legume intercropping practices have long been popular, they did not receive systematic attention within the rigid framework of conventional on-farm trials [

3]. Such trials fix production systems to treatments that can overlook commonly available institutional, technical, and resource-based options, or the evolving, dynamic interactions among maize varieties, legume species, and management practices [

42].

Given these gaps, a systematic review sought to collate the current literature on maize−legume systems in SSA and synthesise insights at system, practice, and intervention levels, enabling the de facto principles of resilient maize−legume systems to emerge and guiding future crop management research, development, and extension towards priorities most directly aligned with smallholder needs and opportunities [

43]. The review explicitly adopted an agroecological lens to enhance climate resilience, increase food security, and improve environmental outcomes.

Rigorous evidence on the effects of these systems on soil fertility, climate resilience, and food security was also assembled [

44]. In addition to highlighting strengths and gaps in the literature, the review explored theoretical and conceptual frameworks for scaling agroecological interventions across diverse socio-ecological systems, establishing basic principles for a future research agenda aligned with the realities of smallholder farming systems in SSA [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40].

Soil health is a reflection of the physical, chemical, biological, and economic properties of soil. Physical quality includes soil texture (indicating soil type), structure (formation of larger aggregates), porosity (volume of pores affecting water flow), aeration (movement of water and gases when soil is saturated), water holding capacity (retention of moisture), moisture conductivity (ease of moisture transport), and resistance to erosion (degradation caused by wind and water).

Chemical quality encompasses soil nutrient availability, soil pH, ability to provide cations, and humus content [

42,

43,

44,

45,

46]. Biological quality entails the presence of beneficial microbes, fungi, earthworms, and other organisms that promote a healthy environment for plant growth. Economic properties include the availability of monetary resources to promote soil improvement, such as financial capital to purchase fertiliser or subscription to extension services to learn better practices. The quality of these properties can be determined comprehensively, or a single indicator can be used for periodic assessment. Since machines cannot measure these indicators directly, proxy measurements that correlate consistently and reliably with the indicators of interest can be employed [

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47].

Soil characteristics define soil quality because they govern the retention and transmission of heat, air, and moisture; the supply of macro- and micronutrients; the fixation and availability of nutrients; the ability to maintain efficient water and nutrient polishing; and the ecological sustainability of agricultural land [

48]. These soil characteristics also remain relatively unchanged over an annual basis, providing a reasonable basis for monitoring. Soil reflects the combined effects of geology, climate, topography, plants, animals, and time, and varies geographically across regions with different land use practices [

47]. In Sub-Saharan Africa, ongoing climate change negatively affects soil quality, and historical land-use decisions exacerbate these declines. Population pressure and urbanisation exacerbate this reduction in quality by shifting land from rural to urban uses and maximising returns on the remaining land. Rapid population growth and urbanisation, accompanied by ongoing changes in farming systems, climate change, and increasing human-induced land degradation, threaten smallholders’ capacity to supply food to a fast-growing population [

3]. Soil quality degrades more rapidly when pressure rises, demanding greater attention and intervention to achieve the sustainable development goals in the region [

36]. Legumes are often selected to enhance soil fertility through biological nitrogen fixation (BNF) and to advocate climate-smart agriculture, as they play a pivotal role in it [

32]. Nonetheless, the complete outline of how maize-legume systems enhance soil fertility within the current climatic conditions remains poorly articulated [

49]. Consequently, a comprehensive view of the effect of maize-legume systems on soil fertility, climate resilience, and food security for smallholder farmers in sub-Saharan Africa is synthesised.

2.7.2. Conceptual Framework

In SSA, inadequate soil fertility is a major constraint on maize production, and agroecological maize–legume systems are increasingly promoted as a potential solution. Hence, a systematic review of the scientific literature on the impacts of these systems is timely. It is guided by a theoretical framework that considers food production to be the ultimate measure of agricultural development [

36]. Intuitively, farming systems that enhance food production are expected to do so by improving climatic, soil, or pest/weed/competitor conditions [

4]; nevertheless, several papers report a lack of direct climatic, soil, or pest-related benefits. In SSA, many impacts of agroecological maize–legume systems can still be considered climate-related because the region’s climate dictates which maize and legume varieties and species are suitable in different areas and crops can therefore do little to ameliorate climate [

3]. Legumes can enhance agricultural productivity and resilience without always providing conventional climate, soil, or pest benefits—their impacts are sometimes indirect but nevertheless relevant. Evidence from SSA on the effects of maize–legume systems on soil fertility, climate resilience, and food security is therefore analysed across five key dimensions.

Capitalising on maize–legume cropping systems is a low-cost, low-risk, and sustainable means of improving soil fertility and food production in Sub-Saharan Africa’s ecologically fragile smallholder farming systems. Growing legumes in alternating or intercropping arrangements with maize (Zea mays L.) effectively introduces large amounts of symbiotically fixed nitrogen into nutrient-depleted soils, which are increasingly under threat due to climate change and increasing human pressures [

4]. Consequently, this systematic synthetic review focuses on filling critical knowledge gaps. A systematic review protocol was elaborated within the framework of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Revising on the review protocol, eligibility criteria were delineated, including types of agricultural interventions, experimental designs, study locations, and data availability [

36]. A systematic search was conducted through five journals in the Web of Science Core Collection covering the main aspects of groundnut–maize, pigeon pea–maize, cowpea–maize, and soybean–maize cropping systems in Sub-Saharan Africa and the information was bibliographically managed by Mendeley and R. Collected records were screened by geographic location and topic of study. Comparison of publication years from inception to 2022 highlighted the gradual evolution from agronomic to climate impacts and subsequently to food security, livelihoods, and policy impacts [

3] (see

Figure 2).

2.8. Strengths and Gaps in Current Literature

The systematic review highlighted several strengths and important gaps in the broader literature. A wide range of studies spanning diverse agroecological and socioeconomic contexts in sub-Saharan Africa documented various aspects of maize–legume systems. The broad geographic and biophysical representation enhanced the generalizability of the findings, and the publication of many studies after the mid-2000s indicated growing interest in these agroecological systems within the farming systems literature. The reviewed studies covered maize–legume intercropping, crop rotation, relay cropping, and multiple cropping systems, providing important insights into multiple configurations of maize–legume systems.

The wide variety of legume species considered—ranging from annual legumes such as cowpea, common bean, and groundnut to perennial legumes such as forage legumes, agroforestry species, and cover crops—also expanded the analysis of different maize–legume configurations. Various management practices (e.g., farm yard manure, other organic amendments) that interact with maize–legume systems were also documented, enabling exploration of synergies with other agroecological practices.

The literature nevertheless still exhibited several notable gaps [

51]. Few studies documented the potential for maize–legume systems to improve rains fed yield stability and climate risk mitigation, despite the region’s growing vulnerability to the impacts of climate change. Other unspecified forms of climate and production risk remained important constraints but were seldom recognized in the literature observed. Similarly, while the food security benefits from other maize–legume systems configurations were widely documented, opportunities to increase the level of diversification through additional legume crops received little attention. Intercropping was also the single most widely studied configuration, and further research on the alternative configurations could enhance understanding of the broader design space. The literature nonetheless still provided valuable insights that can guide further design [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53].

3. Methodology Bottom of Form

Agroecological maize–legume systems are increasingly recognized as a pathway to improve soil fertility, enhance climate resilience, and support smallholder food security in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) [

1]. They involve integrating legumes into maize cropping systems through intercropping and/or rotation and provide multiple agronomic and socioeconomic benefits that are critical for smallholders facing intensifying climatic and market-related pressures [

36]. Despite growing experimental and anecdotal evidence of their positive impact in SSA, the current understanding of the relative contribution of different agroecological, biophysical, and socioeconomic factors to their effectiveness remains fragmented. It is unclear how certain maize–legume systems contribute to addressing common constraints perceived by farmers, such as unstable yields under drought and moisture stress; crop residues that do not contribute to soil fertility or moisture retention; and poor access to food and markets on vulnerable land (e.g., sandy soils and flood-prone areas). A systematic, synthetic review was therefore conducted to consolidate the available scientific, technical, and policy information.

Maize–legume systems constitute a major agricultural innovation promoted across Sub-Saharan Africa by national governments, agricultural research institutes, and development partners. A systematic assessment of scientific evidence for the benefits and challenges of these systems is essential for informing national investment priority setting and planning. Research questions focus on maize–legume species combinations, management practices, and biophysical contexts; impacts on soil fertility, climate resilience, and food security; and barriers and opportunities for adoption.

The systematic assessment followed the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines for transparent and reproducible reporting of synthetic reviews. The strategy combined systematic mapping of evidence to characterize the scope and depth of the literature with systematic eligibility assessment and qualitative synthesis of information addressing specific questions. No formal meta-analysis was attempted owing to the diverse nature of the data and evidence. The review is limited to agroecological maize–legume systems in Sub-Saharan Africa and does not extend to genetically modified maize–legume systems or other maize-based cropping systems combining multiple crops or legumes with non-legumes.

Several bibliographic databases have been consulted as data sources for systematic reviews and synthetic assessments of agricultural research and innovations. For maize–legume systems in Sub-Saharan Africa, only few synthetic assessments were discovered and these dealt exclusively with the issue of climate resilience [

36]. The strategy therefore emphasized broadly based systematic mapping of informal and formal literature on maize–legume systems.

3.1. Research Questions and Eligibility Criteria

Access to sufficient quantities of high-quality food is vital for human health and development. Although high population growth rates and declining land resources exacerbate food security challenges across Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), maize-based cropping systems dominate. Maize is often intercropped or rotated with legumes to improve household food security, but their role in enhancing resilience to climate variability and climate change is unclear.

The study evaluates the biophysical and economic impacts of maize–legume systems on food security, soil health, and climate resilience for smallholder systems across SSA. The following research questions guide the evaluation:

- 1)

What agronomic management systems improve soil fertility and soil health in maize–legume systems?

- 2)

How do maize–legume systems enhance climate resilience?

- 3)

What are the impacts of maize–legume systems on smallholder food security, nutrition, and income?

Maize–legume systems of interest consist of one maize crop combined with a grain or cover legume and include a range of management practices and agroecological innovations. Studies addressing the impacts of maize–legume systems on smallholder food security in SSA are eligible for inclusion. The assessment excludes research conducted within controlled environments such as greenhouses, laboratories, or pots because these studies cannot be readily implemented by smallholders.

Maize–legume systems are promoted widely to improve soil productivity and farm livelihoods in Malawi. Grain legumes intercropped or rotated with maize improve fertility and—under adequate rainfall—are profitable despite labor constraints. Maize–legume systems are thus important for their role in food and income security of smallholder’s dependent on rainfed systems. Farming systems must be able to cope with climate variability, which strongly affects soil productivity. Hence, the review addresses the contribution of maize–legume systems to climate resilience in Malawi and identifies enabling technologies for their wider dissemination. Maize–legume systems should be complemented with a better understanding of climatic threats to maize productivity and soil fertility, conditions under which they provide such benefits, and factors influencing adoption of these systems across contrasting agroecological zones of Malawi.

The review follows contemporary best practices for systematic reviews and a conceptual framework for knowledge synthesis adapted to tropical agriculture. Simultaneously, it contributes to three literature themes. It gives a comprehensive overview of the roles of maize–legume systems in agrarian change, climate resilience, and food and nutrition security since the 1970s. It updates studies that summarize knowledge on intercropping and rotation since the early 2000s. Finally, it evaluates the literature on crop diversification in Sub-Saharan Africa at a scale not previously attempted. Specified thematic topics are production and income effects of crop diversification, analysis of selected system options, and marketing implications [

1,

32].

3.2. Search Strategy and Data Sources

Agroecological maize–legume systems for improving soil fertility, climate resilience, and smallholder food security in Sub-Saharan Africa:

3.2.1. A Systematic Synthetic Review

The analysis followed a systematic synthetic review process based on two complementary but connected approaches to mining literature and knowledge; the first approach being to investigate the co-occurrence between a set of crop production systems (maize–legume, maize–soybean, maize–cowpea and maize intercrop) and the three themes of soil fertility, climate resilience and food security through a set of analytical tools; and the second approach relying on published reviews looking at soil fertility, climate resilience and food security to extract recommendations specifically linked to a range of crop production systems.

A comprehensive review of the scientific literature published between 2000 and September 2024 was conducted to investigate the agronomic, biophysical, economic and socio-institutional factors influencing the adoption and/or performance of agroecological maize–legume systems. Google Scholar, ScienceDirect, Scopus and CAB Abstract were used to find studies using the following search string adapted from a previous application to agroecological practices [

4]: “(maize OR corn OR Zea mays) AND (legume OR pulses OR beans OR soybean OR soybeans OR groundnut OR peanuts OR cowpea OR Vigna unguiculata OR pigeonpea OR Cajanus cajan) AND (agroecology OR agroecological OR conservation agriculture OR conservation agriculture OR low external input sustainable agriculture) AND (soil OR fertility OR climate OR resilience OR food-security OR food-security OR nutrition OR food OR access OR availability)”. The search was restricted to studies conducted in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) and only literature published in English was retained to facilitate synthesis of the evidence base. All data collected were documented in a spreadsheet, categorised by country and region and organised by agroecological maize–legume systems and associated items.

The application of the search string yielded 612 entries, of which 459 were retained after removal of duplicate and irrelevant items. Five additional studies were added after screening some related publications of the collected literature to yield a total of 464 relevant studies on agroecological maize–legume systems for improving soil fertility, climate resilience and smallholder food security in SSA.

In November 2021, peer-reviewed articles, reports, theses, and conference papers on maize–legume systems in SSA were identified by searching three scientific databases—Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar—using a combination of keywords and Boolean operators. The search string “(maize OR (Zea AND mays)) AND (legume* OR (cowpea OR Vigna AND unguiculata) OR (groundnut OR Arachis AND hypogaea) OR (pigeon pea OR Cajanus AND cajan) OR (soybean OR Glycine AND max) OR (faba AND bean) OR (Phaseolus AND vulgaris)) AND (agroecolog* OR (eco* AND intensif*))” was applied. Most of the publications within the topic were thus acquired and recorded with full bibliographic details at the abscissa. Additionally, bibliographic information and connections of some 40 additional consultancy documents and scientific contributions were gathered through snowball sampling (

Table 1). Subsequently, all sources were filtered for eligibility according to the PRISMA protocol and saved in a permanent reference management system in the Mendeley software tool. Since the acquisition of data, the collection has been frequently updated to gather recent literature and to monitor forward and backward snowball sampling continuously.

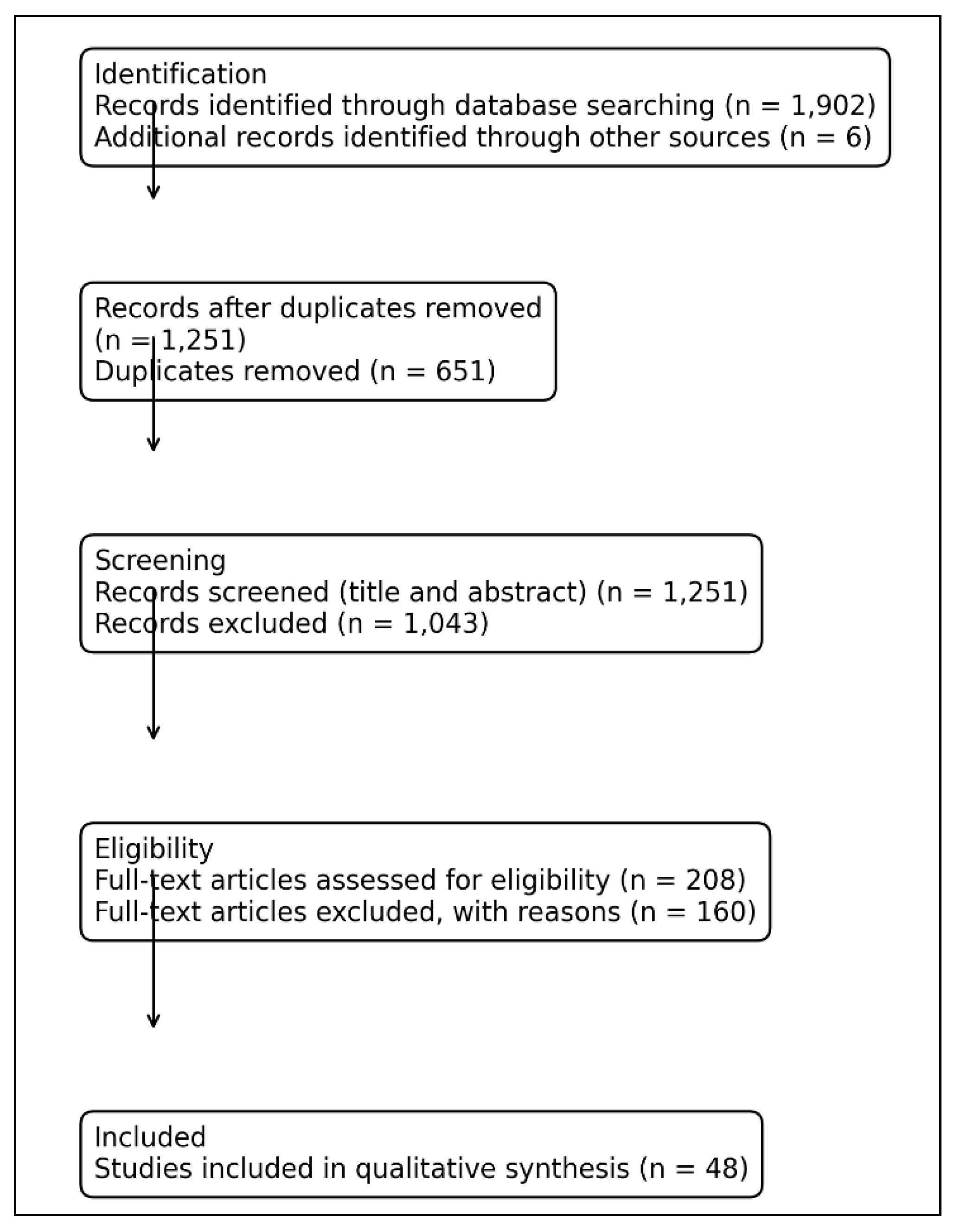

3.3. Study Selection and PRISMA Flow

Tracking study selection and screening processes transparently is essential for reproducibility and appropriate interpretation of systematic reviews. A PRISMA flow diagram depicting the study selection process was constructed according to guidelines [

2] (

Figure 3). The protocol was registered with the PROSPERO international prospective register of systematic reviews (registration number CRD42021284080).

The search strategy was executed on 10 December 2020 and resulted in a total of 1,902 records. After removing 651 duplicates, the titles and abstracts of 1,251 records were screened against the eligibility criteria to remove clearly irrelevant studies. Titles and abstracts of 208 records flagged for potential eligibility were subsequently reviewed, and full texts of 103 articles were retrieved. These were screened against the eligibility criteria to identify relevant studies. Further studies were identified through citation tracking. Finally, 48 studies were included for data extraction and synthesis.

The PRISMA flow diagram indicates that 1,902 studies were initially identified through database searches. After removing 651 duplicates, 1,251 records remained for title and abstract screening. A total of 1,043 studies were excluded at this stage. Title and abstract screening flagged 208 records for full-text assessment. Six additional studies were found through citation tracking. Ultimately, 48 studies met the eligibility criteria for data extraction and synthesis (

Figure 3).

3.3.1. Search Terms and Boolean Strategy

A systematic literature review following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines is conducted. The search for relevant studies combines keywords and controlled vocabulary terms from the MAIZE, CABI, and Scopus databases encompassing “African’’, “arnicae’’, “Azolla’’, “biodiversity’’, “cowpea’’, “Dukari’’, “foxtail’’, “Gambia’’, “Gozo’’, “harvest’’, “maize’’, “rotation’’, and “recovery’’. A total of 265 records are returned; after duplicates are removed, 255 records are screened based on title, abstract, and publication date, resulting in 44 potentially relevant publications. Using the eligibility criteria, 22 studies are selected for analysis (

Figure 3). As indicated in the PRISMA diagram, criteria such as the type of document, experimental site, and research focus are used in the selection process.

3.3.2. Thematic Categorization

Relevant material is extracted and tabulated, organized by authors, year, study region, and other key features. The geographical diversity of the studies is also considered by selecting additional records from the bibliographic reference lists of the specified articles. A systematic approach to identifying pertinent literature involves a qualitative synthesis of 38 paper reports and additional research abstracts analysed using standard evaluation criteria. The term “systematic review” therefore refers to the systematic collection and appraisal of evidence pertaining to a considerable number of indicators of performance or impact.

The impact statement summarising the higher-order empirical observation of amelioration of a broad range of metrics and indicators across a very large number of studies is also included. Such systematic studies progressively narrow in focus. At the other extreme, a fully comprehensive literature survey of scientific information arising from substantially larger, more diffuse, and complex maize research domains is undertaken instead.

3.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis

Agroecological systems are increasingly valued for their potential to improve soil fertility, support ecosystem services, and create climate-resilient farming systems, particularly in drier areas where conventional options to enhance productivity are limited. The systematic analysis of maize-legume systems builds on previous research. It is intended to support decisions regarding the diversification of farming systems in sub-Saharan Africa, one of the regions most affected by climate change. Given that systems are being widely promoted, there is a need for a collective, comprehensive synthesis of available evidence to guide further investment in knowledge and practice. The systematic review followed a rigorous methodology to gather previously published insights, enabling a deeper understanding of limitations and opportunities associated with such widespread adoption.

Enhanced post-harvest management, the use of improved varieties, and the development of local seed production systems were also identified as key areas where government and donor support could enhance the productivity impacts of maize-legume systems [

2,

3]. Interest in legume-maize systems is rising rapidly, generating numerous studies in recent years. Yet, the available literature assessing their contribution to key challenges in sub-Saharan Africa remains surprisingly sparse.

Journals and bibliographic references in all languages were searched, including grey literature and documents published or made available between January 2000 and July 2021. The non-linear engine developed by the Center for Evidence-Based Conservation was used to search for eligible records on the Clarivate Web of Science Core Collection. The 25 non-duplicated, potentially credible, and relevant records screened resulted in 147 new records when searched using a title or keywords. The analysis then used three independent keywords to search for Brazilian, subtropical, and temperate systems. All studies that met the first two research questions were then systematically reviewed. Texts available only in Portuguese or Spanish and articles published in journals without an official impact factor were included as additional sources.

The specific research questions used to select the records in the final systematic review were as follows:

What are the effects of maize–legume systems on soil fertility and soil health in SSA?

What are the effects of maize–legume systems on climate resilience in SSA?

What are the effects of maize–legume systems on smallholder food security and livelihoods in SSA?

The results from the screening and applying the PRISMA criteria summarize the distribution of records in the systematic review. The results from the selected studies were then systematically synthesized.

3.5. Software Used

Mendeley was used as a reference manager whilst excel was used for the extraction of data. A PRISMA flow diagram was prepared using a PRISMA template (

Figure 3).

4. Results

Agroecological maize-legume systems present viable options for improving soil fertility, climate resilience, and food security in sub-Saharan Africa. Despite promising evidence, maize-legume systems face recognition challenges among local actors, and the extent of peer-reviewed evidence remains unclear. A systematic review synthesizes the environmental, climate, and food security benefits of agroecological maize–legume systems across sub-Saharan Africa.

Agroecological maize–legume systems constitute diverse crop rotations, intercropping, and agroforestry practices that combine maize with one or more legumes. On-farm assessments demonstrate their contribution to improved soil fertility by enhancing biological nitrogen fixation, enriching organic matter, and promoting soil health. The systems build climate resilience by maintaining productivity under drought, regulating microclimates, and improving resource-use efficiency. Agroecological maize–legume systems also strengthen food availability, accessibility, and stability. The combination of legumes with maize provides avenues for diversified production and supports the integration of legumes into farming systems.

4.1. Overview of Maize–Legume Systems in Sub-Saharan Africa

Maize–legume systems are widely promoted in SSA as a way to improve productivity and soil fertility through diversification and conservation practices [

4]. Conservation agriculture, characterised by minimal soil disturbance, crop residue retention, and crop rotation or intercropping, is advocated to strengthen these systems, yet full CA principles are rarely achieved in isolation. Complementary practices such as fertiliser application, weed control, and stress-tolerant varieties remain necessary, and CA adoption is limited—approximately 1.5 million hectares across SSA compared to over 200 million in North America and Australia.

Maize monocropping is widespread in SSA, leading to nutrient depletion, lower productivity, and soil erosion, and despite recognition of the need to diversify cropping systems, agroecologists face difficulties introducing rotational or intercropping strategies. Groundnut and pigeon pea have emerged as preferred doubled-up legumes to supplement maize in companion systems that improve land productivity and foster soil fertility. Research indicates that rotating maize with legumes enhances productivity, especially when pigeon pea is included due to its biomass and nitrogen contribution, and pigeon pea in rotation helps sustain soil carbon and cover. Cereal–legume intercrops are common in SSA, but single-maize and maize–groundnut remain the dominant systems; further assessment of value chain benefits along with robust, systematic analyses of options and testing under CA and tillage systems are needed.

Three legume intercropping systems—maize + pigeon pea, maize + groundnut, and maize + cowpea—are widely promoted across SSA [

1]. Intercropping maize with legumes is an established strategy to enhance food production, especially for smallholders, while maize is the dominant crop and sole-maize farming is prevalent; maize + groundnut is particularly common in southern Africa. Legume crops are also integrated into highly desirable fertiliser micro-dosing systems and systems that apply residue mulching to stimulate adoption in both conventional and zero-tillage CA contexts.

Maize is the most important crop in Eastern and Southern Africa and is often combined with legumes in seven different cropping systems. Maize and legumes can be intercropped, rotated, relay intercropped, or grown in association before or after the maize crop, with the possible inclusion of a third legume in rotation or in association. The legumes commonly grown with maize are common bean, pigeon pea, groundnut, chickpea, cowpea, soybean, and mungbean. The frequency of use of these legumes varies considerably among countries, regions and production systems: common bean, pigeon pea, groundnut and cowpea predominate in the eastern region, while groundnut and soybean are more prominent in southern Africa. Maize–legume systems are frequently practised with minimal tillage and limited use of chemical fertilisers. This is in accordance with agroecology principles focusing on soil conservation, resource use efficiency and environmental enhancement [

1,

4,

54].

4.2. Biophysical and Socioeconomic Context

Maize production across Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) is considered by many as the cornerstone of the continent’s effort to achieve a food secure state [

32]. In all SSA countries, maize is cultivated to meet the ever-increasing demand for food as well as commercial use. In Zimbabwe, maize production occupies 44% of the total area planted for crops [

44]. Maize hybrids dominate the maize production sector yet their yield stagnation has led to the exploration of alternative systems, including maize–legume systems involving both intercrops and crop rotations. The vast majority of the maize grown in SSA is still under conditions of low soil fertility, and maize–legume systems have been promoted to smallholder farmers based on alleged soil fertility improvement provided by legumes and their positive effects on subsequent maize crops.

Maize remains the most dominant crop in the cropping systems of the smallholder sectors of most of Sub-Saharan Africa. Food security is a critical issue for millions of smallholder farmers, and therefore boosting crop yields is essential. Agroecological principles are key in low-input agricultural systems in improving the long-term sustainability of cropping systems [

1]. Legumes can improve soil fertility and crop productivity through processes such as biological nitrogen fixation (BNF), improving soil health and water retention through increased organic matter, and promote crop diversification that can reduce risk and spur productivity [

42].

Maize (Zea mays L.) is a critical staple crop in the semi-arid tropics of sub-Saharan Africa, where a high incidence of crop failures significantly jeopardizes food security and rural livelihoods. Improving soil fertility is one of the most critical measures aimed at improving maize productivity and food security among smallholder farmers in this region [

32]. Soils have become increasingly depleted of nutrients due to permanent cultivation without inputs, an increase in the use of low-yielding crop varieties, and a decrease in fallowing, especially in densely populated areas. Despite the urgent need and the positive effect of soil fertility on crop Yield, limited financial resources hinder many smallholder farmers from accessing soil-fertilizing inputs [

1].

Growing legumes alongside maize is increasingly promoted as an attractive option for replenishing soil nutrients. Legumes can fix atmospheric nitrogen and replenish depleted soil nutrient stocks through leaf litter and crop residues, thereby contributing to higher maize yields. The widespread adoption of maize-legume intercropping in sub-Saharan Africa presents a significant opportunity to intensify maize production systems without degrading the environment, provided that appropriate management practices are employed in accordance with agroecological principles.

4.3. Legume Species and Maize Varieties

Maize cropping is dominant throughout Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), underpinned by a variety of both local and improved varieties [

44]. There is broad adoption of a second legume crop (e.g., soybean, common bean, cowpea) to form maize-legume systems in many SSA countries. Despite the critical role of legumes in food security, very few legume-only cropping systems or multiple legume systems have been established alongside maize cropping. These situations illustrate the constraints farmers face. Specific observations of maize-legume systems in key SSA regions are provided to illustrate patterns of use and options for support [

55,

56,

57,

58].

Worldwide, maize and legumes are widely grown in agroecology and extensively promoted and researched. Cropping systems with maize and legumes are common throughout SSA, with extensive information on maize-legume systems due to a long history of study and participatory systems research on legumes in SSA [

1]. In maize-legume cropping systems, legume species include nitrogen-fixing grain legumes (pigeon pea, groundnut, soyabean, common bean, and cowpea), herbaceous perennial legumes (Stylosanthes and Desmodium), green manure legumes (Tephrosia, Mucuna, and Crotalaria), and cover legumes (Calopogonium and Centrosema). The selection of locally preferred maize varieties and the use of optimal management practices for crops, residues, cropping systems, and soil-fertility-management strategies are crucial in tailoring systems that foster agroecological-principle-based development.

Legume species included in maize-legume systems vary considerably across agroecological zones in SSA. In semi-arid and arid zones, low-input and limited-legumes species (either grain, green manure, or cover) with low-priority supply chains are still dominant. In addition, access to local seeds, high-yielding varieties, emerging pest and pest adaptation types, adverse climatic situations, and limited market access strongly influence the selection of legume species. Priority legume crops in these regions include drought-resistant, rapidly growing low-legume species (e.g., groundnut, cowpea, and Crotalaria). In contrast, perennial legumes (e.g., Stylosanthes, Desmodium, and Centrosema) and cover legumes (e.g., Calopogonium) with longer-period adaptation traits are still limited. The wide variety of options highlighted above—roughly aligned with the existing selection of crops in SSA—offers an opportunity for greater agroecological impact.

4.4. Management Practices and Agroecological Principles

Agroecological principles aim to build climate-resilient agricultural systems through synergetic interactions among soil, crops, and livestock developed by local farmers over generations of smallholder subsistence agriculture. Sub-Saharan Africa’s historical development of maize–legume systems exemplifies such agroecological management. The biodiverse legume–maize cropland mosaic developed before colonial influence demonstrated the importance of adhering to agroecological principles [

1]. Current interest in maize diversification seeks to enhance soil functionality following mineral fertilizer overuse, enabling improved climate resilience and food security [

3]. Reconsidering the past fosters fresh perspectives on agroecological management and economic development by emphasizing diversification through maize–legume systems, an integral part of the pre-colonial agricultural landscape now threatened by fertilizer overuse. Agricultural research and policies emphasizing synergy among crop types and integrating technical and systemic knowledge could stimulate diversification and sustainable development.

Crop management practices affect the performance of maize–legume systems. Maize was either intercropped with legumes or grown in a rotation with legumes; legumes were often sown later than maize and harvested earlier. In Malawi, maize was largely intercropped with pigeon pea (Cajanus cajan), groundnut (Arachis hypogea), or mungbean (Vigna radiata); farmers perceived that maize competition was minimal and preferred intercropping [

1]. The integration of other legumes (e.g., Tephrosia vogelli) on-farm evaluations in Malawi since 1994 indicated a reduction in legume adoption, resulting in renewed interest in legume management. These practices have been identified in various innovations that align with agroecological principles [

3]. Intercropping, crop rotation, intercropping with cover crops, relay intercropping, delayed planting (e.g., five weeks) of maize after legumes, and the use of organic fertilizers are among the most common practices in Malawi. Farmers also employ cover crops to prevent soil degradation.

4.5. Impacts on Soil Fertility and Soil Health

Intercropping maize with legumes enhances soil fertility and health. Biological nitrogen fixation (BNF) supplements inorganic fertilizers, increasing nutrient availability both in the short run and over years of continuous cropping. Legumes also promote organic matter accumulation and improved soil structure through their high root biomass, greater shoot residue, and incorporation of carbon-rich materials from cover crops. In addition, legume-maize crop residues, particularly from mucuna, increase soil moisture retention during dry periods. They improve the capture of rainwater, reduce runoff and soil erosion, and foster improved infiltration [

3].

Agroecological maize–legume cropping systems are widely promoted for smallholder farmers in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) to simultaneously tackle pressing challenges of soil fertility, climate resilience, and food security. Nevertheless, empirical evidence remains scarce. To fill this knowledge gap, a systematic synthetic review is conducted characterizing agroecological maize–legume systems in SSA and exploring their reported impacts on soil fertility, climate resilience, and smallholder food security. A total of four and seven studies are identified documenting soil fertility and health, and climate resilience, respectively.

Findings reveal that maize–legume systems benefit soils primarily through biological nitrogen fixation and organic matter accumulation, enabling greater fertilizer savings than legs-alone systems. In terms of climate resilience, they enhance yield stability under drought, regulate microclimate and pest pressure, and boost resource-use efficiency for a given climate risk. While knowledge on food security impacts is lacking in SSA, maize–legume systems are seen as a promising pathway towards climate-resilient food security [

3,

32].

4.5.1. Biological Nitrogen Fixation and Soil Nutrient Cycling

Biological nitrogen fixation (BNF) through legumes significantly enhances the availability of nitrogen and other nutrients in cropping systems across Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) [

54]. BNF provides a substantial component to total nitrogen inputs in maize–legume systems where maize follows legumes or maize–legume intercrops are practiced (see

Figure 4). The presence of legumes also increases soil organic matter as a result of root exudation, litter deposition, and the subsequent turnover of bacterial and fungal biomass associated with decomposition [

64].

Multiple studies report improved soil nutrient balances, with a substantial portion attributed to BNF [

3]. Furthermore, farmers have noted increased responsiveness to external nutrient inputs, underscoring the potential of cropping systems to improve overall N cycling in SSA agriculture. BNF is therefore essential for sustaining agricultural production systems and maintaining soil fertility at acceptable levels without overreliance on mineral fertilizers. Biological nitrogen-fixing legumes are incorporated to replenish soil nutrient stocks, reduce the need for external inputs, mitigate fluctuations in resource use, buffer against climate variability, and contribute ecological goods and services from a broader agroecological perspective.

Maize grain yields increase significantly when legumes are intercropped or rotated with maize on smallholder farms in sub-Saharan Africa, particularly during periods of unpredictable rainfall [

3]. On-farm studies show that nitrogen balances are zero or negative without legumes, and farmers recognize legumes as a key strategy to mitigate risk. Biological nitrogen fixation by legumes plays a fundamental role in sustaining soil fertility and crop productivity in nutrient-depleted soils [

64]. Grain legumes such as Glycine max, Cajanus cajan, and Arachis hypogaea can fix 50–300 kg N ha⁻¹ per season depending on management and environment, while higher-yielding legumes such as Vigna unguiculata and Vigna radiata fix roughly 20–50 kg N ha⁻¹ [

54] (

Figure 4). Over 50% of N derived from legumes is subsequently available for the following maize crop in intercropping systems.

Soils across the region often have pH levels below 5.0 and critical amounts of micronutrients such as K, S, Zn, and B are frequently deficient.

In addition to residual N, legumes can enhance soil nutrient availability by mobilizing and supplying P and Zn, and suppress N losses through leaching and denitrification during heavy rainfall. Maize–legume systems can slow down soil fertility decline while smallholders transition to higher-capital investments such as mineral fertiliser and improved germplasm selection. By revitalising food systems in drought-prone regions, maize–legume systems stimulate cereals, legumes, and livestock production through the adoption of biological nitrogen fixation.

4.5.2. Organic Matter Accumulation and Soil Structure

Human-induced activities fundamentally govern organic matter accumulation within agroecosystems. Approaches aimed at improving organic matter have historically involved the incorporation of externally-sourced materials, including organic manures, crop residues, agroforestry prunings, and cover crop residues. Under conventionally managed smallholder maize cropping systems in semi-arid Zimbabwe, there have been sizeable declines in organic matter. Regular manure application combined with substantial cover crop biomass, as an example of organic resource integration, has supported relatively higher carbon and nitrogen. To ensure the retention of substantial and sustained carbon reserves, the introduction of relatively large amounts of organic additions remains essential, due to the already highly degraded conditions that prevail, and tropical contexts which hasten decomposition.

In maize–legume intercropping systems in Southern Africa smallholder farmers manage organic resources for soil fertility under the influence of multiple socio-economic factors. The most common organic resources are crop residues and green legumes. An extensive literature analysis highlights that organic resources such as crop residues and green legumes significantly improve soil properties and maize productivity in Zimbabwean smallholder cropping systems [

64]. The agronomic principles behind these findings are applicable to similar regions in Southern Africa.

Crop residues provide energy, macro- and micronutrients and enhance microbial activity creating soil aggregates. Green legume manures may be added before or after the maize cropping season. They provide instantaneous energy and nitrogen via biological fixation and slow nutrients during subsequent maize phases. Leguminous green manures also promote soil structural development and can be managed to support cropping systems providing reliable food security [

65].

4.5.3. Residue Management and Soil Moisture Retention

In most of Sub-Saharan Africa, maize is grown rain-fed on dryland and is susceptible to drought. Crops of maize without legumes tend to exhibit a linear decrease in yield with increasing drought stress level, while the presence of legumes enables the retention of crop yield until higher levels of drought [

1]. The residues of maize and grain legumes, when returned to the soil, enhance the moisture and nutrient retention so that crops can survive longer and achieve higher yield. Most maize residues from previous seasons are known to be incorporated into the soil in Southern African smallholder farming systems, while a substantial portion is still burnt. Groundnut residues are also burnt, despite recognition of their benefits, significantly restricting fertilisation from legumes.

Reducing water runoff and enhancing soil moisture are key components for improving agricultural production by smallholder farmers in sub-Saharan Africa, particularly in areas where rainfall is scarce, variable, and shortened by climate change [

1]. Legume and maize residues retain moisture, with residue quality and deep rooting systems being critical factors for effective residue management and moisture retention. Farmers’ choice of legume and maize types for cultivation is influenced by the quality of the materials. Tephrosia, Sesbania, Arachis, Cajanus, Dolichos, and Mucuna spp. are examples of legumes with high-quality residues that facilitate nitrogen availability in the short to medium term, which is important given that many legumes grown in rotation, intercropping, or catch-cropping situations offer low-quality residues that immobilize nitrogen and provide only very limited short-term benefit.

4.6. Impacts on Climate Resilience

Maize is one of the most important staple crops in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), providing food for the population and income for smallholder farmers. However, it is vulnerable to climate variability and global climate change. Climate variability negatively affects maize performance in terms of starvation, lack of yield stability, declining productivity, and inability to respond to farmers’ demands. Agroecological approaches using maize-legume systems can enhance climate resilience through maintaining yield stability, enabling maize cultivation under diverse environments, maintaining soil moisture, reducing temperatures and humidity within the field, and diversifying profit streams for farmers [

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68,

69].

Maize is the cornerstone of food security, income, and social status for a majority of smallholder farmers in SSA. However, the decline in soil fertility due to land degradation has constrained maize production [

62]. As a result, there has been a growing interest in sustainable maize production alternatives, including integrated soil fertility management and conservation agriculture [

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59]. Maize-legume intercropping and rotations have been promoted to restore soil fertility and improve food security, and long-term testing of agroecological maize-legume systems on-farm experiments in several countries shows that the residual benefits of grain legumes can increase maize grain yield in addition to legumes contribute to food, livestock feed, and cash income for farmers [

7]. Similarly, simulation studies conformed the roles of cropping systems in improving resilience by enhancing resistance and recovery from droughts [

49,

50,

51,

52,

53].

Agroecological maize–legume systems contribute to climate resilience by increasing yield stability under drought, regulating temperature and humidity, and improving resource use efficiency. Biological nitrogen fixation increases the resilience of maize to climate variability by enhancing root development and canopy cover [

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62]. The maize varieties used in these systems tend to be drought-tolerant, further supporting climate-resilient production [

7]. By increasing soil organic matter and improving soil structure, maize–legume systems enhance infiltration and water-holding capacity, which allows more water to be stored in the soil after rain has ceased. Residue retention helps to improve soil moisture content by reducing evaporation, thus providing a buffer against dry spells. Moreover, intercropping reduces variability in maize yield by enabling combined harvests when one crop is affected by drought. Temperature regulation is improved via canopy cover and mulching; these practices suppress weed pressure and improve pest control, further stabilising yields under climate stress [

45].

Because these systems increase resource use efficiency, they also enhance productivity and profitability at low levels of investment—thereby mitigating the risk of investment in high-input technologies [

35]. By improving malnutrition pathways linked to food availability and income, maize–legume practices also diminish dependence on climate-sensitive irrigation—yet this constitutes only one aspect of their contribution to climate resilience.

4.6.1. Yield Stability Under Drought and Climate Variability

Maize–legume systems and agroecological practices stabilize food and nutrient availability across varying rainfed and irrigated growing seasons. Simultaneously, increase Microclimate regulation, pest suppression, soil–plant–water pathway and resource efficiency. Limited water available for crops during most growing seasons remains a critical challenge for smallholders. Agri-food systems adapted to water scarcity are needed to mitigate yield losses resulting from dry spells and erratic rainfall [

4]. Water scarcity remains a major challenge to maize productivity. Online resources and the Africa RISING project encourage adoption of drought-tolerant cultivars.

Timely planting of locally-built maize varieties, conservation agriculture tillage, legume intercropping, crop rotation, and return of crop residues increase water use efficiency, lower stress on crops, and stabilize maize yield at critical periods. Efficiency is aided by combination of locally-built improved drought-resilient maize varieties, legume intercropping, adoption of broader planting spacing (75 cm or above), and alternating cropping of maize with legume crops. Combination of legumes enable farmers to broaden lot size planted to maize while conserving high-value legumes for more-favoured fields [

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67].

Maize yields low and variable across Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Interventions are needed to remove root causes of low yields in order to stabilize and increase productivity. Most smallholder maize produced is rainfed. Rainfed maize areas remain unproductive and vulnerable to climate variability and extreme weather events. Climate variability shortens the maize cropping window and leads to high production and post-harvest losses. Establishing maize–legume systems requires multiple earlier actions, tackling root causes. Fundamental root cause is that more climate-resilient improved varieties, N fixation legumes, soil health-enhancing practices, and Integrated Soil Fertility Management practices are locally available, yet remain untested or little validated. In these conditions, Residue management and Soil moisture retention practices installed and in widespread use. Particularly large area under legumes stacked with crop diversification and micro-climates earlier built switch to maize–legume familiarity and rapid uptake. Yield stability within maize–legume systems as standalone practice is high and coupled with adjacent Gradual Adoption Finish remains viable for rapid area growth [

67,

68,

69,

70].

Agroecological systems combining maize with legumes can improve climate resilience by promoting yield stability under drought stress or climate variability. Maize and legumes have different sensitivity to drought and other climatic stressors. Research in southern Malawi found that maize–legume intercropping reduces the yield gap of maize associated with drought by 24%, while rotation reduces the drought yield gap by just 15% [

70]. An extensive study across West Africa showed that both yield and rainfall variability are positively correlated, reflecting climate vulnerability [

8].

For food security, policies should support managers in reducing yield gaps of dryland maize cultivars rather than increasing total production. Possible measures include decentralising seed production and improving the supply of organic amendments to raise fertiliser efficiency on acid soils [

36].

4.6.2. Microclimate Regulation and Pest Suppression

Crop diversification enhances microclimate regulation through increases in canopy cover and horizontal shading. Canopy cover plays an important role in increasing relative humidity and decreasing temperature above the crop, providing a microclimate more conducive for plant and soil health, live microbes, nutrient cycling, and biological nitrogen fixation [

81]. Adequate microclimate regulation through legume-maize intercropping significantly improves crop health. This is especially important in weather-sensitive crops such as maize, given the uncertain precipitation patterns in Sub-Saharan Africa. Improved crop health further reduces the risk of crop damage due to stem borer attack.

The use of maize–legume intercropping systems aids crop diversification and contributes to the suppression of major pests such as the African stem borer and the maize fall armyworm. Live plants in a cropping system function as alternative hosts and mating / oviposition sites for both pests, thus diverting pests away from the maize host. A greater variety of actively growing host plants improves the efficacy of push–pull by supporting a greater density and diversity of natural enemies capable of suppressing insect pests.

Stabilisation of temperatures and atmospheric humidity is essential for maize production in sub-Saharan Africa, as these factors influence growth, flowering and irruption of pests [

8]. Maize-legume systems increase spatial complexity and contribute to habitat management. Legumes reduce soil degradation and improve water retention by promoting soil health [

37]. The push–pull system enhances habitat management and crop diversity, yet the concomitant adoption of legume intercropping has not been evaluated [

43]. Maize-legume intercropping systems help stabilise yields under high variability and can improve soil and water conservation in fragile areas.

4.6.3. Resource Use Efficiency and Risk Mitigation

Agroecological maize–legume systems are considered to outperform maize monocultures regarding climate resilience. Reduced reliance on external chemical inputs is also viewed as crucial for smallholder livelihood improvement in sub-Saharan Africa [

45]. Nevertheless, mineral fertilizers are deployed in many agroecological interventions to increase biophysical output levels [

3,

46]. Maize–legume systems reportedly diminish vulnerability to pests and diseases compared to sole maize or maize with fertilizer [