Submitted:

09 January 2026

Posted:

12 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

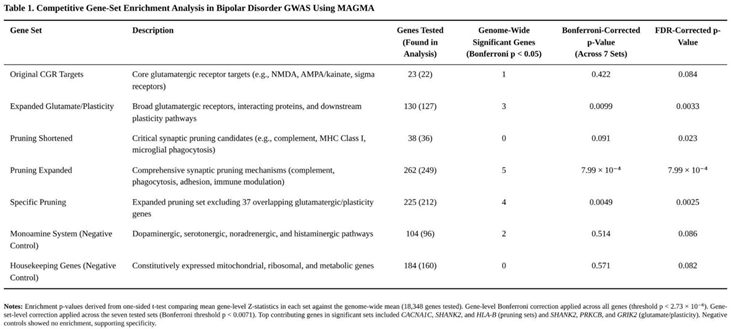

MAGMA Gene-Based and Gene-Set Analysis

- 23 focused glutamatergic-receptor target genes.

- An expanded glutamatergic/synaptic-plasticity list (130 genes).

- A core synaptic pruning list (38 genes).

- A broad pruning list (262 genes).

- A "specific pruning" list (225 genes) created by removing the 37 glutamatergic/plasticity genes that overlap with the broad pruning set.

- A monoaminergic control list (104 genes).

- A housekeeping-gene control list (184 genes).

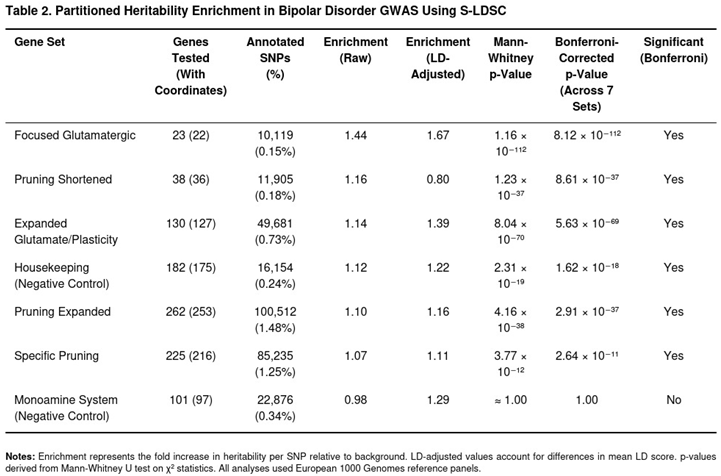

Partitioned Heritability with Stratified LD-Score Regression

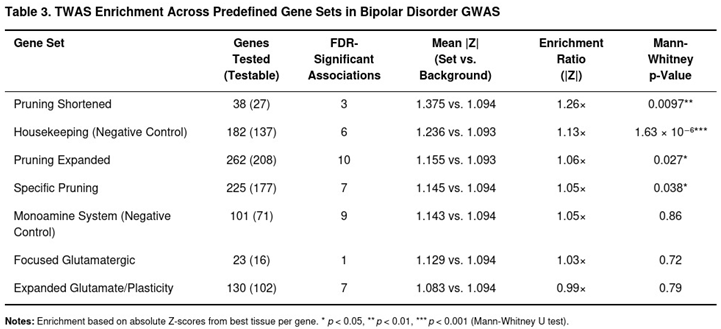

Transcriptome-Wide Association Analyses with S-PrediXcan

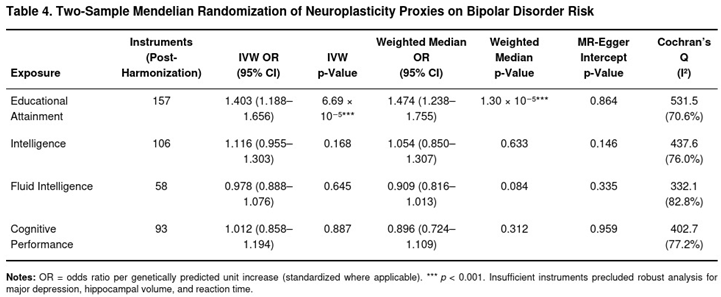

Two-Sample Mendelian Randomization

Comparison with the MDD GWAS

Results

MAGMA Gene-Based and Gene-Set Analysis

Partitioned Heritability with Stratified LD-Score Regression

Transcriptome-Wide Association Analyses with S-PrediXcan

Two-Sample Mendelian Randomization

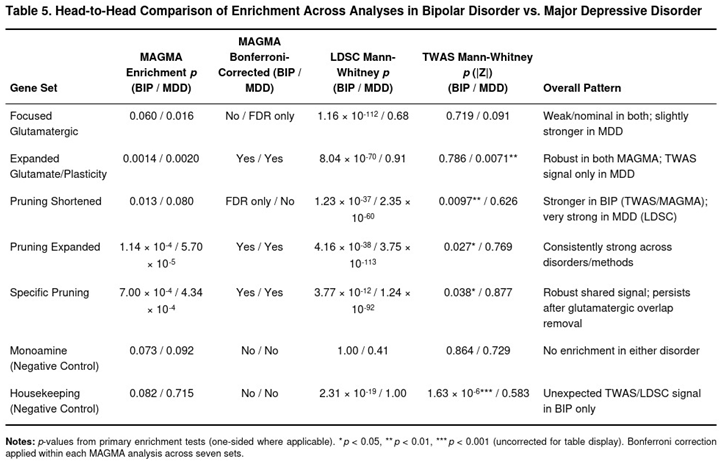

Head-to-Head Comparison to the MDD Results

Discussion

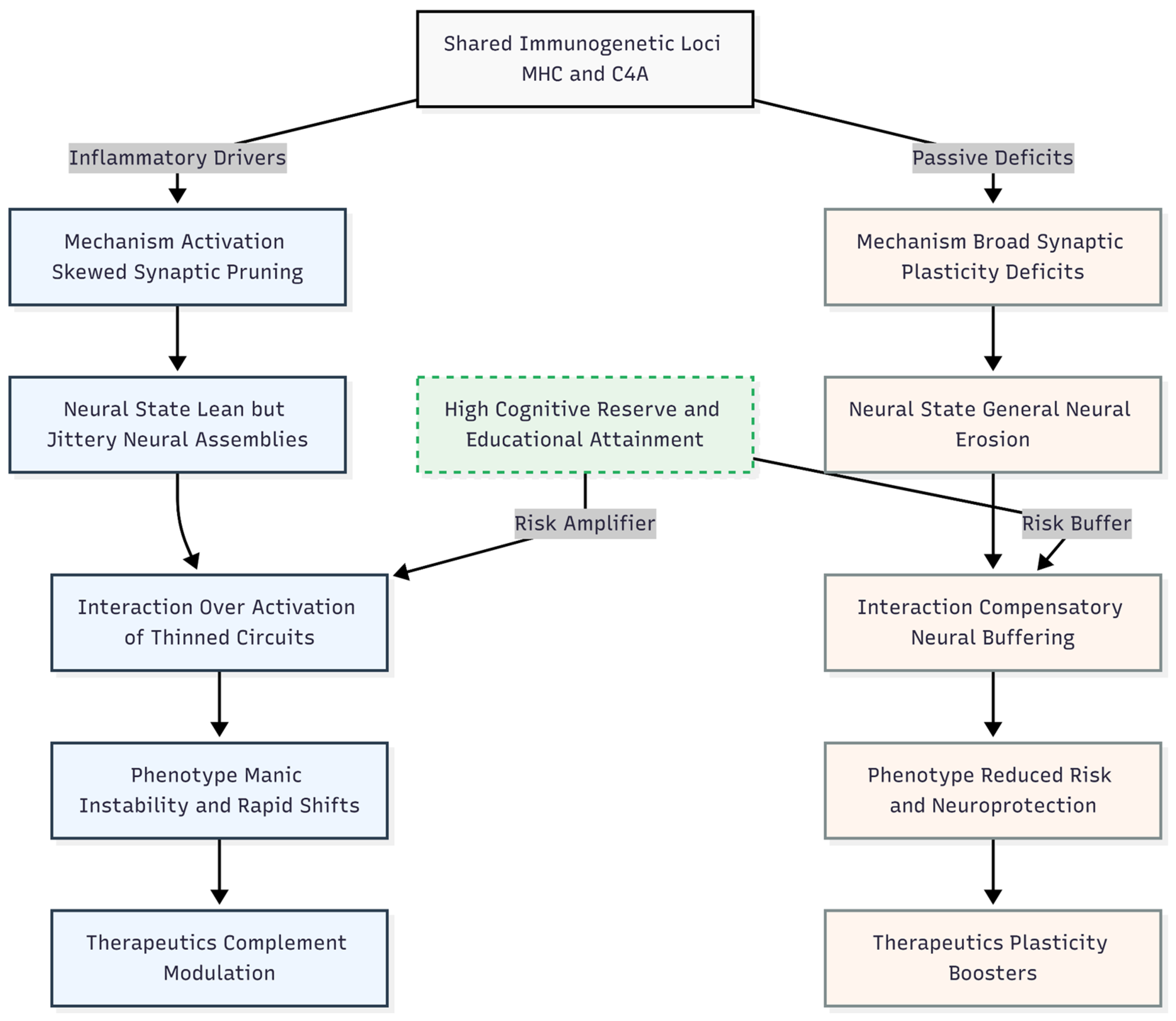

Deriving an Etiological Hypothesis for Bipolar Disorder from the Divergence

Novelty and Impact

Limitations

Conclusion

Funding

Ethics Declaration

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grande, I; Berk, M; Birmaher, B; et al. Bipolar disorder. The Lancet 387(10027), 1561–1572. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merikangas, KR; Jin, R; He, JP; et al. Prevalence and correlates of bipolar spectrum disorder in the World Mental Health Survey Initiative. Archives of General Psychiatry 68(3), 241–251. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stahl, EA; Breen, G; Forstner, AJ; et al. Genome-wide association study identifies 30 loci associated with bipolar disorder. Nature Genetics 51(5), 793–803. [CrossRef]

- Mullins, N; Forstner, AJ; O'Connell, KS; et al. Genome-wide association study of more than 40,000 bipolar disorder cases provides new insights into the underlying biology. Nature Genetics 53(6), 817–829. [CrossRef]

- Cross-Disorder Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Genomic relationships, novel loci, and pleiotropic mechanisms across eight psychiatric disorders. Cell 179(7), 1469–1482.e11. [CrossRef]

- Trubetskoy, V; Pardiñas, AF; Qi, T; et al. Mapping genomic loci implicates genes and synaptic biology in schizophrenia. Nature 604(7906), 502–508. [CrossRef]

- Malhi, GS; Tanious, M; Das, P; et al. Potential mechanisms of action of lithium in bipolar disorder. Current understanding. CNS drugs 27(2), 135–153. [CrossRef]

- Zarate, CA, Jr.; Singh, JB; Carlson, PJ; et al. A randomized trial of an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist in treatment-resistant major depression. Archives of General Psychiatry 63(8), 856–864. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekar, A; Bialas, AR; de Rivera, H; et al. Schizophrenia risk from complex variation of complement component 4. Nature 530(7589), 177–183. [CrossRef]

- Coleman, JRI; Peyrot, WJ; Purves, KL; et al. Genome-wide gene-environment analyses of major depressive disorder and reported lifetime traumatic experiences in UK Biobank. Molecular psychiatry 25(7), 1430–1446. [CrossRef]

- Major Depressive Disorder Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Trans-ancestry genome-wide study of depression identifies 697 associations implicating cell types and pharmacotherapies. Cell 188(3), 640–652.e9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Connell, KS; Koromina, M; van der Veen, T; et al. Genomics yields biological and phenotypic insights into bipolar disorder. Nature 639(8056), 968–975. [CrossRef]

- de Leeuw, CA; Mooij, JM; Heskes, T; et al. MAGMA: Generalized gene-set analysis of GWAS data. PLOS Computational Biology 11(4), e1004219. [CrossRef]

- Finucane, HK; Bulik-Sullivan, B; Gusev, A; et al. Partitioning heritability by functional annotation using genome-wide association summary statistics. Nature Genetics 47(11), 1228–1235. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbeira, AN; Dickinson, SP; Bonazzola, R; et al. Exploring the phenotypic consequences of tissue specific gene expression variation inferred from GWAS summary statistics. Nature Communications 9, 1825. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamazon, ER; Wheeler, HE; Shah, KP; et al. A gene-based association method for mapping traits using reference transcriptome data. Nature Genetics 47(9), 1091–1098. [CrossRef]

- Urbut, SM; Wang, G; Carbonetto, P; et al. Flexible statistical methods for estimating and testing effects in genomic studies with multiple conditions. Nature Genetics 51, 187–195. [CrossRef]

- Davey Smith, G; Hemani, G. Mendelian randomization: genetic anchors for causal inference in epidemiological studies. Human Molecular Genetics 23, R89–R98. [CrossRef]

- Lee, JJ; Wedow, R; Okbay, A; et al. Gene discovery and polygenic prediction from a genome-wide association study of educational attainment in 1.1 million individuals. Nature Genetics 50, 1112–1121. [CrossRef]

- Savage, JE; Jansen, PR; Stringer, S; et al. Genome-wide association meta-analysis in 269 867 individuals identifies new genetic and functional links to intelligence. Nature Genetics 50, 912–919. [CrossRef]

- Bowden, J; Davey Smith, G; Burgess, S. Mendelian randomization with invalid instruments: effect estimation and bias detection through Egger regression. International Journal of Epidemiology 44, 512–525. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, N. From Pruning to Plasticity: Refining the Etiological Architecture of Major Depressive Disorder Through Causal and Polygenic Inference. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- MacCabe, JH; Lambe, MP; Cnattingius, S; et al. Excellent school performance at age 16 and risk of adult bipolar disorder: national cohort study. The British journal of psychiatry: the journal of mental science 196(2), 109–115. [CrossRef]

- Malhi, GS; Mann, JJ. Depression. The Lancet 392(10161), 2299–2312. [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, F; Aggio, V; Pratesi, ML; et al. Neuroinflammation in bipolar depression. Frontiers in Psychiatry 11, 71. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutantio, EH; Octaviani, ID. Neuroinflammation in the Pathogenesis of Psychiatric Disorder. Bulletin of Counseling and Psychotherapy 7(2). [CrossRef]

- Berk, M; Post, R; Ratheesh, A; et al. Staging in bipolar disorder: From theoretical framework to clinical utility. World Psychiatry 16(3), 236–244. [CrossRef]

- Berk, M; Kapczinski, F; Andreazza, AC; et al. Pathways underlying neuroprogression in bipolar disorder: focus on inflammation, oxidative stress and neurotrophic factors. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 35(3), 804–817. [CrossRef]

- Cyrino, LAR; Delwing-de Lima, D; Ullmann, OM; et al. Concepts of Neuroinflammation and Their Relationship With Impaired Mitochondrial Functions in Bipolar Disorder. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience 15, 609487. [CrossRef]

- Coleman, JRI; Peyrot, WJ; Purves, KL; et al. Genome-wide gene-environment analyses of major depressive disorder and reported lifetime traumatic experiences in UK Biobank. Molecular psychiatry 25(7), 1430–1446. [CrossRef]

- Streit, F; Awasthi, S; Hall, AS; et al. Genome-wide association study of borderline personality disorder identifies 11 loci and highlights shared risk with mental and somatic disorders. medRxiv: the preprint server for health sciences 2024, 11.12.24316957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, SH; Streit, F; Jungkunz, M; et al. Genome-wide association study of borderline personality disorder reveals genetic overlap with bipolar disorder, major depression and schizophrenia. Translational Psychiatry 7(6), e1155. [CrossRef]

- Post, RM. The Kindling/Sensitization Model and Early Life Stress. Current topics in behavioral neurosciences 48, 255–275. [CrossRef]

- Kapczinski, F; Magalhães, PV; Balanzá-Martinez, V; et al. Staging systems in bipolar disorder: an International Society for Bipolar Disorders Task Force report. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 130(5), 354–363. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieta, E; Berk, M; Schulze, TG; et al. Bipolar disorders. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 4, 18008. [CrossRef]

- Passos, IC; Mwangi, B; Vieta, E; et al. Areas of controversy in neuroprogression in bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 134(2), 91–103. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).