Probabilistic computing represents a new paradigm that uses intrinsic randomness to solve otherwise intractable computational problems. A crucial step toward its practical realization is the emulation of probabilistic behavior on conventional reconfigurable hardware platforms, particularly FPGAs.

In the following subsections, the relevance of FPGA-based emulation is examined, followed by a review of the methodologies currently available for implementing p-bits and probabilistic circuits on FPGA. This discussion provides the foundation for highlighting the distinctive features and advantages of the proposed approach.

2.1. Importance of FPGA-Based p-bit Emulation

FPGAs provide fine-grained logic and interconnection resources, enabling the design of customized computing architectures tailored to specific applications [

24,

25]. Their reconfigurable nature, consisting of configurable logic blocks, interconnects, and I/O elements, makes them particularly well suited for mapping p-bits and probabilistic logic circuits into hardware.

FPGA-based emulation of p-bits plays a critical role as an intermediate step before committing to nanoscale realizations, such as spintronic devices. This approach offers several advantages. First, FPGAs provide a flexible platform for exploring different network topologies and scaling behaviors without the cost and delays associated with fabricating physical prototypes [

26]. Second, FPGA emulation enables reproducible and controllable stochastic dynamics, unlike physical nanoscale devices, which often suffer from fabrication variability and environmental sensitivity [

2]. Third, FPGA-based platforms facilitate hybrid architectures in which probabilistic accelerators can be seamlessly integrated with conventional digital processors [

27].

Compared to software simulations, FPGA emulation also provides significant benefits. While simulations on CPUs or high-level environments such as MATLAB can reproduce stochastic behavior, they remain inherently sequential and computationally expensive when dealing with large interconnected networks [

28,

29]. By contrast, FPGA hardware supports true parallelism, allowing multiple p-bits to update simultaneously and thereby more faithfully reflecting the parallel nature of probabilistic spin logic [

30]. This parallelism results in substantial speedups, improved scalability, and even real-time operation capabilities. Moreover, FPGA hardware guarantees predictable timing behavior, whereas software simulations are often affected by operating system overheads and variable execution times [

31].

Although GPUs and microcontrollers represent alternative hardware options, FPGAs retain distinctive advantages. General-purpose CPUs and microcontrollers are inherently sequential and thus unsuitable for large-scale stochastic networks [

32], while GPUs—optimized for Single Instruction Multiple Data (SIMD) floating-point operations—suffer from scheduling overheads and non-deterministic timing [

33,

34]. By contrast, FPGAs combine low-latency deterministic execution with massive parallelism and customizable logic, resulting in superior scalability and energy efficiency [

35,

36].

Table 1 summarizes the main architectural differences across these platforms.

Beyond their role as research emulators, FPGA-based p-bit systems are increasingly being recognized as practical probabilistic accelerators. Their intrinsic parallelism and energy efficiency make them particularly attractive for accelerating Monte Carlo simulations, Bayesian inference engines, and combinatorial optimization tasks [

4,

37,

38]. The reconfigurability of FPGAs further enables adaptation to changing problem instances, outperforming fixed-function accelerators in terms of versatility [

39,

40]. As FPGA technology continues to advance in density, efficiency, and connectivity, its role in probabilistic hardware computing will only become more prominent [

41].

A particularly promising direction is the hybrid CPU–FPGA architecture, where the CPU manages orchestration and preprocessing, while the FPGA performs the computationally intensive probabilistic updates using p-bit networks. In this division of labor, inference tasks are dispatched from the CPU to the FPGA accelerator, which returns probabilistic decisions or updated states. Such architectures enable real-time inference, scalability, and adaptability across a wide range of applications, from Bayesian reasoning and constraint satisfaction to neuromorphic computing.

2.2. State-of-the-Art FPGA-Based p-bit Implementation Methodologies and Original Contribution

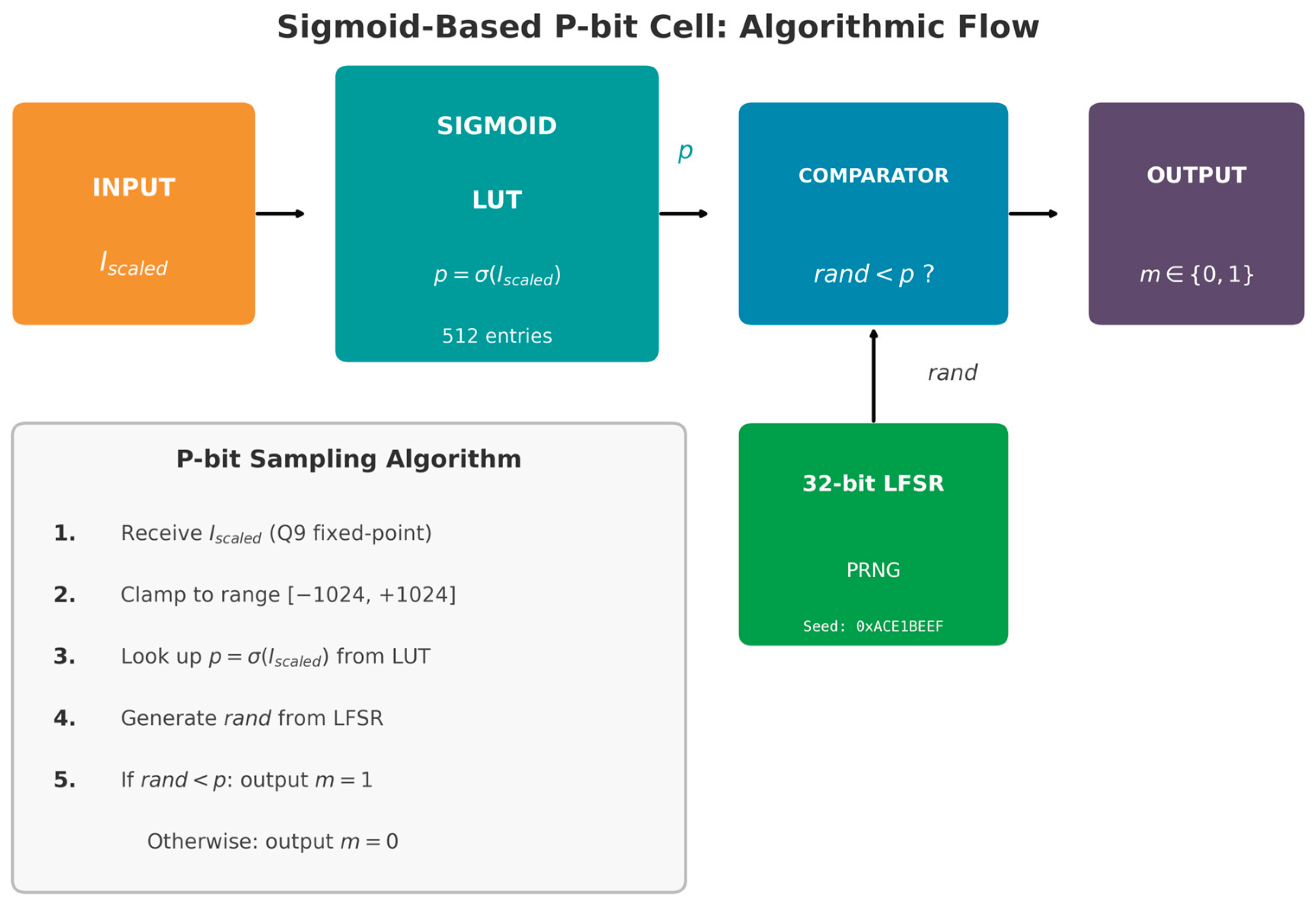

Several methodologies have been proposed for implementing p-bits on FPGA platforms, each presenting specific advantages and trade-offs [

42,

43]. The most common strategy relies on Linear Feedback Shift Register (LFSR)-based pseudo-random number generators combined with comparison logic, where stochastic outputs are generated by comparing random values against input-dependent thresholds [

44]. This approach provides efficient hardware utilization and good control over output probabilities, while maintaining computational simplicity.

Alternative solutions employ true random number generators (TRNGs), exploiting metastability in flip-flops or entropy sources such as ring oscillators to achieve genuine stochasticity [

45,

46]. While these implementations improve the statistical quality of randomness, they typically require additional resources and careful calibration to ensure robustness against process, voltage, and temperature variations. Hybrid approaches combine deterministic and stochastic elements, for example using lookup tables (LUTs) to realize p-bit activation functions while leveraging hardware RNGs for probabilistic decision-making [

47]. More advanced implementations incorporate adaptive mechanisms, such as dynamic threshold adjustment and coupling strength modulation, to enable online learning and optimization [

48].

Recent studies have also explored specialized architectures—including bistable ring networks, coupled oscillators, and magnetic tunnel junction emulators—that aim to replicate the physical dynamics of nanoscale p-bit devices more faithfully [

49,

50]. Indeed, most FPGA-based emulation efforts are conceptually inspired by physical devices proposed for hardware-level realization of p-bits [

51,

52,

53,

54,

55]. Although a detailed review of these physical implementations lies beyond the scope of this paper, it is worth noting the class of quasi-zero energy barrier probabilistic devices, which intrinsically realize sigmoid activation functions [

22]. This concept is closely related to the methodology adopted in this work and will be further described in the following sections.

A key milestone in the literature is the introduction of weighted p-bits, which are strongly oriented to FPGA implementation and provide significant advantages compared to stream-based methods in terms of scalability, resource efficiency, and statistical accuracy. Weighted p-bits are stochastic computational units fluctuating between binary states (0 and 1), with tunable probabilities modulated by external inputs. Beyond Bayesian inference, their applications extend to combinatorial optimization (e.g., Traveling Salesman Problem, Max-Cut), stochastic machine learning models such as Restricted Boltzmann Machines and Deep Belief Networks, physical simulations including the Ising model, and cryptographic systems requiring secure random number generation. This versatility makes weighted p-bits a promising substrate for probabilistic hardware computing.

The paradigm of encoding probabilities as digital weights rather than continuous bitstreams was primarily advanced by researchers at Purdue University, who demonstrated its superiority over traditional schemes requiring one RNG per p-bit. The foundational work by Pervaiz et al. [

23] formally introduced weighted p-bits for scalable FPGA-based probabilistic circuits (p-circuits). Their contribution, later contextualized and reinforced by the broader architectural vision of interconnected p-units described by Camsari et al. [

5], represents the current state of the art. A critical analysis of these two works highlights both the strengths and the limitations of the weighted p-bit methodology.

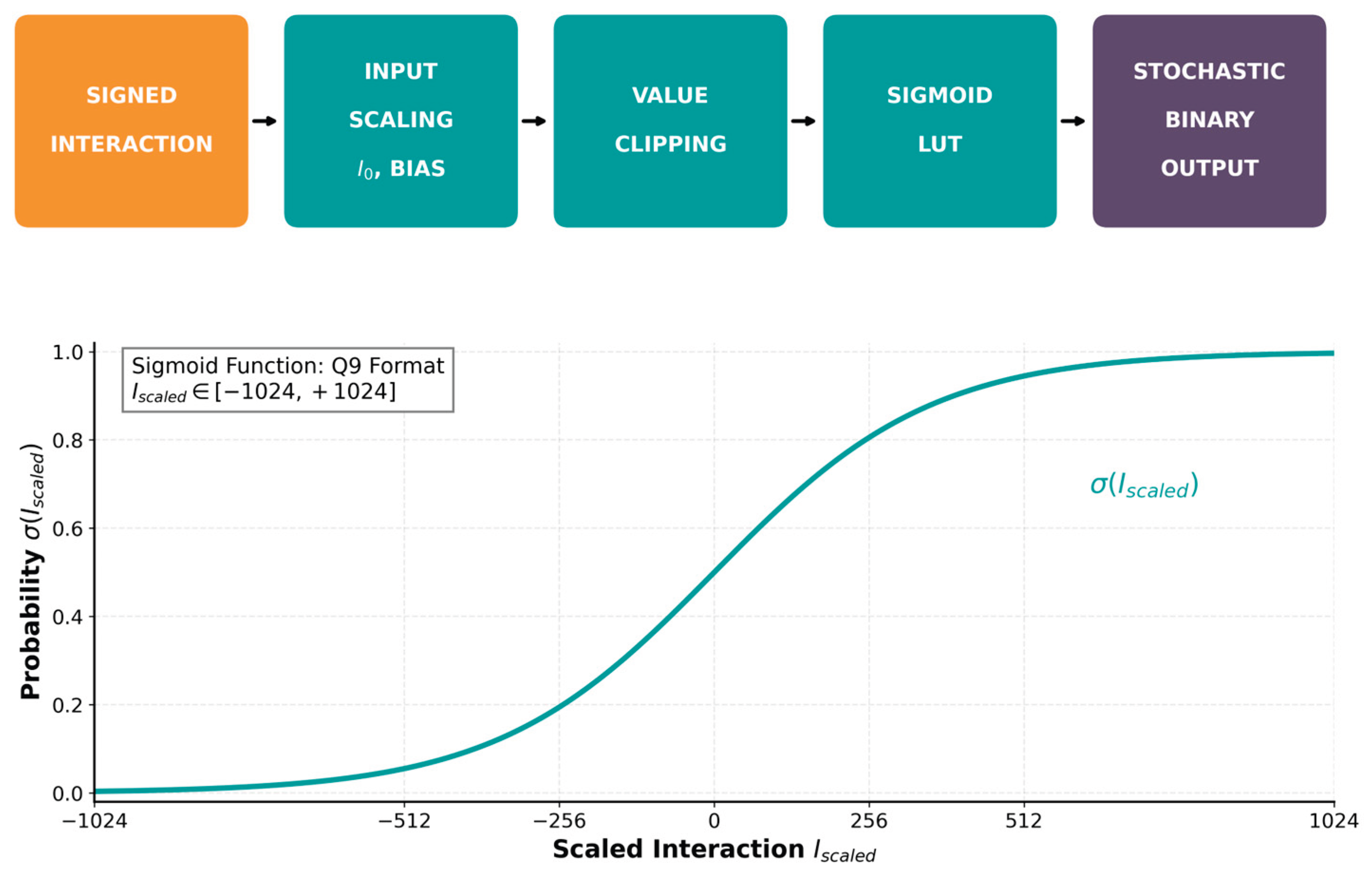

These pioneering designs emulate networks of stochastic binary units whose state is updated according to a tunable sigmoid probability, implementing the relation

where

approximates the thermal activation of low-barrier nanomagnets. In such systems, weighted interconnections are realized through analog-inspired multipliers or digital matrix operations, and sequential updating of the p-bit array is typically enforced by a sequencer to maintain the statistical correctness of the Markov chain.

The first major strength lies in scalability and resource efficiency. In conventional implementations, each p-bit requires a dedicated LFSR, making large-scale systems impractical. Pervaiz et al. [

23] solved this bottleneck by decoupling probabilistic logic from random number generation: a p-bit’s probability is stored as a digital weight, while interactions are computed deterministically through arithmetic operations. This reduces the need for multiple RNGs, as a single, high-quality generator can be shared across the system. Camsari et al. [

5] further support this perspective, positioning p-bits as efficient, interconnected probabilistic units.

The second strength is computational efficiency. By representing weights and probabilities as digital values, the stochastic update process becomes a weighted summation followed by an activation function, operations well suited for FPGA parallelism and pipelining. This yields significant speedups compared to traditional bitstream-based stochastic computing.

Architecturally, the design proposed in [

23] separates the p-bit into two functional blocks: (i) a deterministic weight matrix, which computes activation values via summations and multiplications; and (ii) a tunable RNG block, containing the LFSR, which maps the activation value to a probability threshold and produces the stochastic output by comparison. Crucially, the RNG block can be shared among multiple p-bits, eliminating the one-to-one mapping of LFSRs to p-bits and thereby achieving scalability. In this model, the LFSR is still present but relegated to a centralized, reusable resource, while the defining elements of the p-bit are its weights and arithmetic logic.

Despite these advantages, both works [

5,

23] reveal important limitations. First, stability of stochastic dynamics still requires a sequencer to enforce sequential updates, an approach inherited from Boltzmann machine theory. Second, activation functions are restricted, with limited flexibility and reduced interpretability for neuromorphic applications. These gaps define the scope for the original contributions of the present paper.

More recent works have focused on digital emulation on FPGA platforms, emphasizing area–latency efficiency and scalability. Sigmoid approximations have evolved from look-up-table (LUT) implementations to piecewise linear or rational polynomial forms optimized for low resource usage and low latency [

56,

57,

58]. Notably, the authors in [

56] demonstrated a curvature-adaptive piecewise linear method providing a 40% reduction in logic utilization with negligible error, while in [

57] introduced a Taylor-segment approach achieving 11-bit accuracy with minimal DSP cost. Such techniques are directly applicable to p-bit emulators in which the sigmoid serves as the activation core.

The random excitation required by stochastic neurons is typically generated through pseudo-random number generators (PRNGs) such as LFSRs or through true random number generators (TRNGs) exploiting metastability or oscillator jitter [

45,

46,

59]. TRNG-based approaches (e.g., Fibonacci–Galois ring oscillators or start–stop phase-detuned rings) offer higher entropy at the cost of reduced controllability, whereas PRNG-based methods provide deterministic reproducibility, desirable for debugging and FPGA verification.

An important architectural aspect in the literature is the update scheduling of p-bits. Sequential updates are used in the weighted p-bit models to guarantee convergence to the intended Boltzmann distribution. However, several FPGA implementations inspired by Ising machines and Restricted Boltzmann Machines (RBMs) have demonstrated that parallel or block-parallel updates can still yield correct and stable solutions for optimization tasks [

60,

61,

62]. Recent studies on hardware Ising annealers implemented via Hamiltonian Monte Carlo also report negligible degradation in accuracy under synchronous updates, while drastically improving throughput. These findings align with the results obtained in the present work, where sequencer-free parallel updates maintain statistical stability and deterministic convergence across multiple probabilistic logic designs.

Table 2 summarizes the key design trade-offs in FPGA-based p-bit emulation, highlighting how the choice of activation function, randomness source, and update scheduling affects hardware complexity, statistical fidelity, and scalability.

The recent literature on hardware-efficient sigmoid implementations, such as the works in [

56] and [

57], has confirmed the practicality and accuracy of LUT-based and piecewise-linear approximations for digital hardware. These studies, primarily targeting neural and machine learning applications, demonstrate that the sigmoid function can be efficiently realized on FPGA with minimal resource overhead while preserving numerical stability. In this work, the same class of techniques is repurposed within a spin-inspired probabilistic computing framework, where the sigmoid serves as the stochastic activation core of each p-bit. This choice establishes a methodological bridge between neural hardware accelerators and probabilistic spin logic, providing both physical interpretability and hardware efficiency.

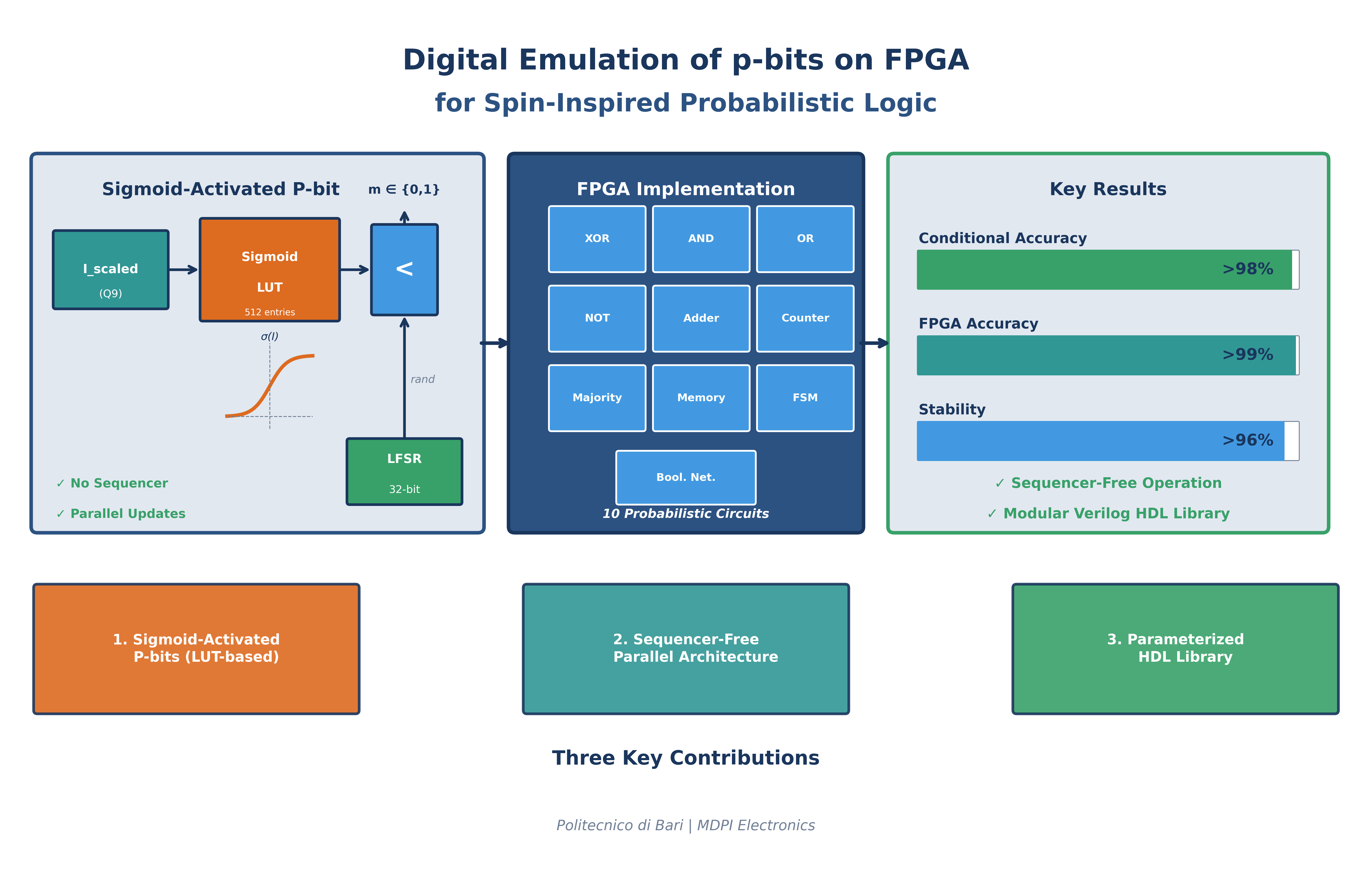

Building on this foundation, the proposed architecture introduces several original contributions that extend beyond the current state of the art.

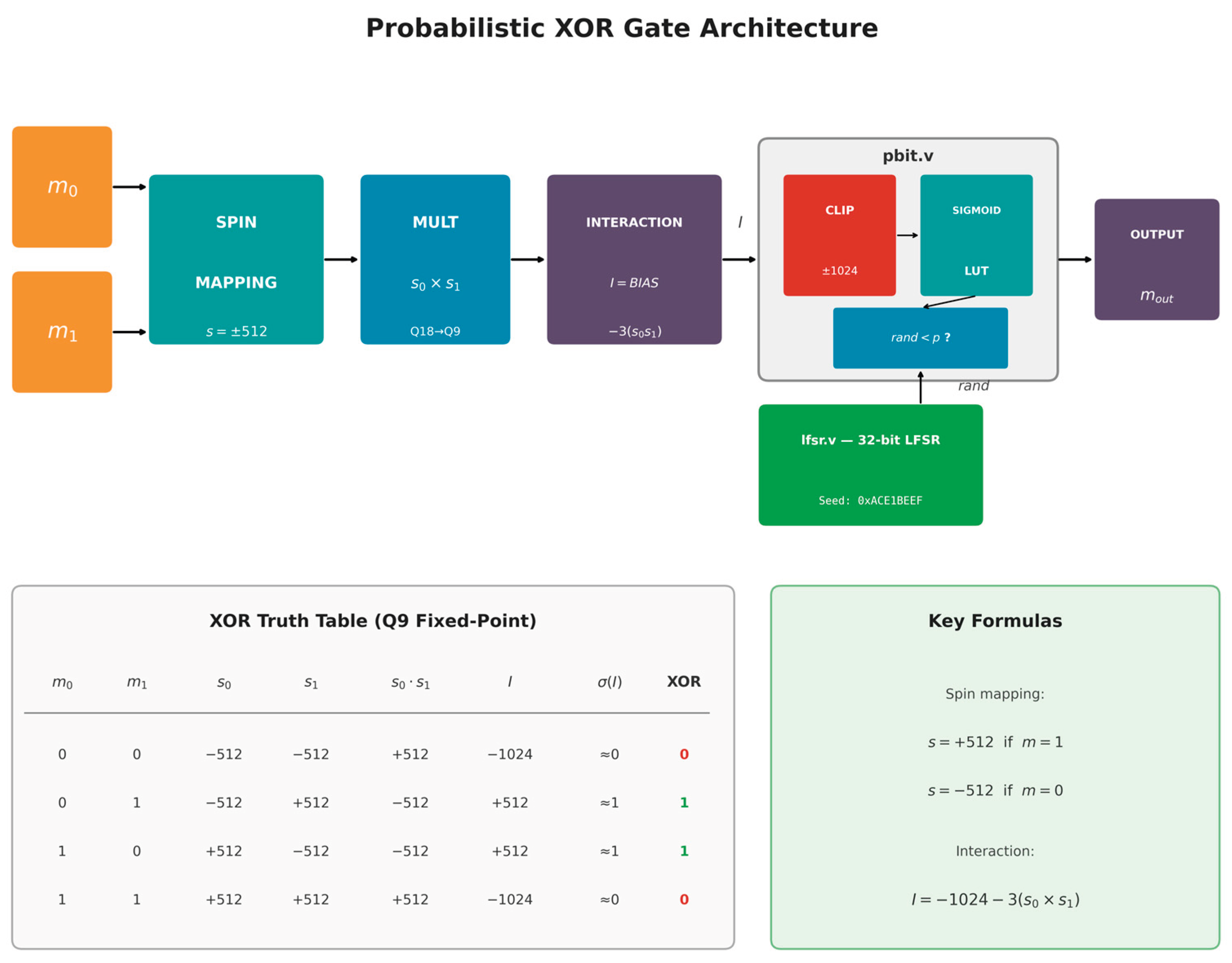

The first original contribution is the introduction of a parameterized Verilog HDL p-bit cell, conceived as a modular and reusable hardware element. Unlike previous proof-of-concept implementations of individual gates and circuits [

5,

23], the proposed cell provides configurable parameters for weights, thresholds, and activation functions. This parameterized framework enables the systematic construction of probabilistic logic gates (AND, OR, XOR), registers, counters, adders, finite-state machines, and higher-level stochastic systems using the same unified building block. Such modularity promotes standardization, accelerates development, and ensures portability across FPGA families. Moreover, it approximates the notion of a functionally complete probabilistic system, analogous to the universal NAND or NOR gates of classical logic, thereby allowing the synthesis of any probabilistic digital circuit through parameter adjustment [

63,

64].

The second original contribution concerns the adoption of a sigmoid-based activation function in place of the weighted scheme. Inspired by recent studies on near-zero energy barrier probabilistic devices that intrinsically realize sigmoid dynamics [

22], as well as FPGA-oriented research on hardware-efficient approximations of the sigmoid function (e.g., LUT-based, piecewise linear, or Taylor-segment implementations) [

56,

57,

58], this design offers more direct control and clearer physical interpretability of model parameters such as interaction strength and bias. Compared with the weighted p-bit framework, the proposed LUT-based sigmoid realization provides greater flexibility, higher numerical stability, and closer alignment with spin-based probabilistic models, while remaining fully compatible with FPGA resources such as LFSRs for randomness generation.

The third contribution is the elimination of sequencers, a major architectural simplification. Whereas the weighted p-bit framework requires sequential updates to preserve the statistical correctness of the Markov chain [

23], the proposed parameterized, sigmoid-based p-bits achieve stable and accurate stochastic behavior under fully parallel operation. This is validated by dedicated evaluation metrics demonstrating consistent statistical behavior without temporal control circuitry. Removing sequencers reduces design complexity, enhances throughput, and substantially improves scalability.

In summary, the proposed FPGA framework builds upon the foundation established by Pervaiz et al. [

23] and Camsari et al. [

5], while drawing methodological inspiration from more recent advances in hardware-efficient sigmoid realizations on FPGA, such as those reported in [

56] and [

57]. The present work overcomes the key limitations of the weighted p-bit framework by introducing (i) a parameterized p-bit library for modular and reusable design, (ii) a hardware-optimized sigmoid activation function—consistent with proven FPGA-efficient techniques yet applied here within a spin-inspired probabilistic computing paradigm—and (iii) a sequencer-free architecture enabling fully parallel stochastic operation.

Together, these innovations establish a unified, physically interpretable, and resource-efficient approach to probabilistic computation. They simplify the hardware design flow, improve system scalability, and pave the way for more versatile FPGA-based emulators of spin-inspired probabilistic logic circuits.

In contrast to prior FPGA-based p-bit implementations that primarily target faithful emulation of Boltzmann-machine dynamics, the present work emphasizes architectural simplicity, modularity, and deterministic reproducibility, positioning the proposed framework as a practical engineering platform for probabilistic logic and sequential stochastic systems.