1. Introduction

Statins, or HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors, are widely prescribed lipid-lowering agents that have demonstrated substantial efficacy in reducing cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [

1]. By inhibiting the rate-limiting step in cholesterol biosynthesis, statins reduce low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels and are a cornerstone in the prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease [

2]. Despite their overall safety and clinical benefit, statins are associated with a spectrum of adverse effects, most notably statin-associated muscle symptoms (SAMS), which range from mild myalgia to severe rhabdomyolysis [

3]. These adverse reactions represent a leading cause of non-adherence and discontinuation of therapy, thereby undermining the preventive impact of statins in routine clinical practice [

4].

Pharmacokinetic variability plays a critical role in determining both the efficacy and toxicity profile of statins. A growing body of evidence has identified genetic polymorphisms in membrane transporters as key modulators of statin disposition [

5]. Among these, the solute carrier organic anion transporter family member 1B1 gene (

SLCO1B1), which encodes the hepatic transporter OATP1B1, has been most extensively studied. The single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) c.521T>C (rs4149056) results in reduced OATP1B1 function, thereby impairing hepatic uptake of statins and increasing systemic drug exposure [

6]. This variant has been strongly associated with a higher risk of statin-induced myopathy, particularly with simvastatin and atorvastatin therapy [

7].

Another key transporter involved in statin pharmacokinetics is P-glycoprotein, encoded by the ATP-binding cassette sub-family B member 1 gene (

ABCB1) [

8]. This efflux transporter is expressed in multiple tissues, including the intestine, liver, kidney, and blood–brain barrier, and contributes to the absorption, distribution, and elimination of various xenobiotics [

9]. The

ABCB1 3435C>T SNP (rs1045642), although synonymous, has been associated with altered mRNA stability, protein expression, and substrate transport activity [

10]. Several studies have proposed a potential role of this variant in modulating statin plasma levels and the risk of musculoskeletal adverse events [

11]. However, findings regarding the clinical relevance of

ABCB1 polymorphisms in statin therapy remain inconsistent and require further elucidation [

12].

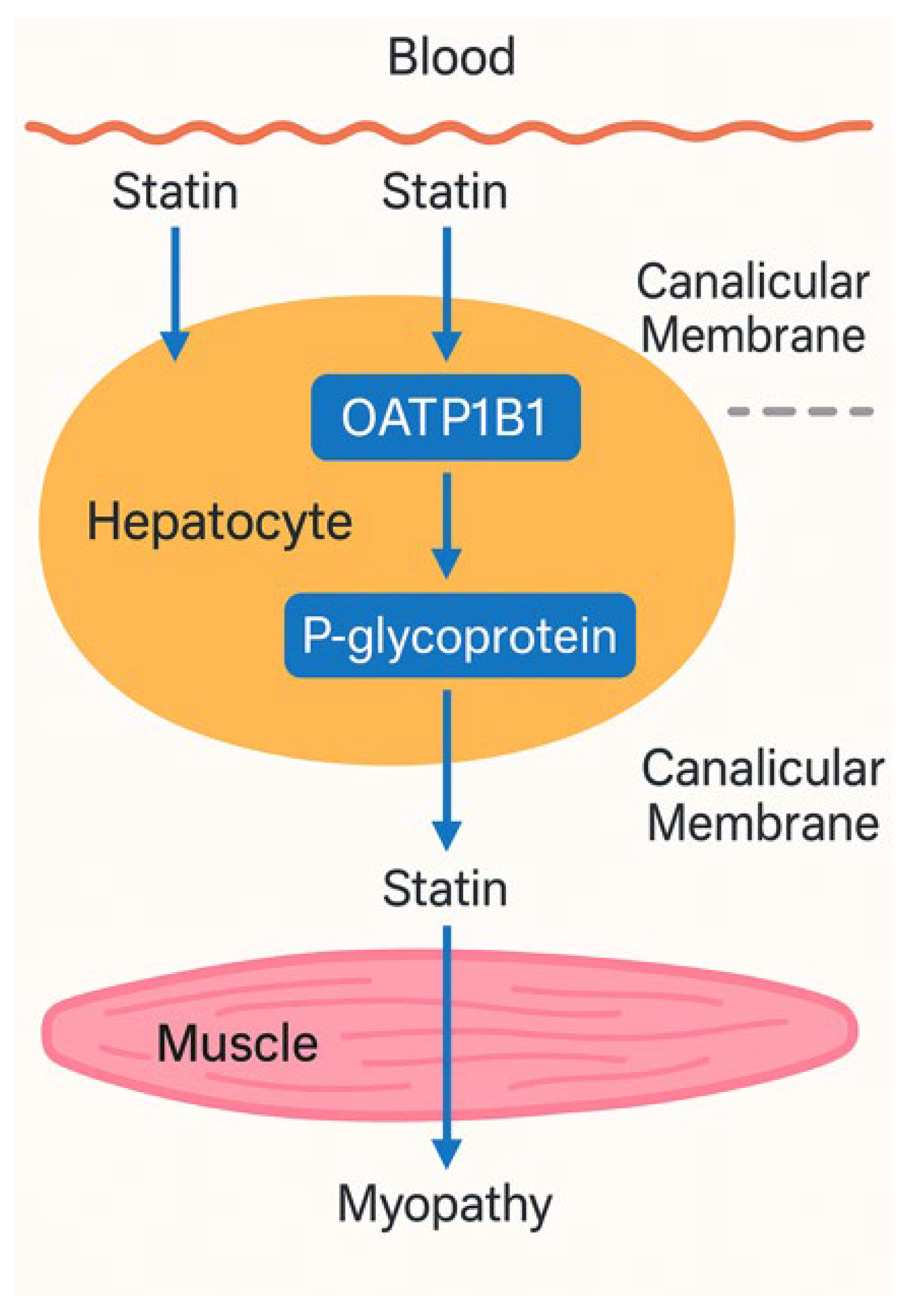

Figure 1.

Mechanistic representation of statin transport involving OATP1B1 and P-glycoprotein and its link to myopathy.

Figure 1.

Mechanistic representation of statin transport involving OATP1B1 and P-glycoprotein and its link to myopathy.

The schematic illustrates the hepatic uptake and efflux pathways of statins. Statins enter hepatocytes from systemic circulation primarily via the SLCO1B1-encoded OATP1B1 transporter. Once intracellular, they are either metabolized or transported into bile canaliculi by the ABCB1-encoded P-glycoprotein. Genetic polymorphisms that impair OATP1B1 function (e.g., 521C allele) reduce hepatic uptake, leading to elevated plasma statin levels. Similarly, reduced-efficiency P-glycoprotein variants (e.g., ABCB1 3435T) may impair drug efflux. Both mechanisms increase systemic statin exposure, raising the risk of skeletal muscle accumulation and statin-associated myopathy.

While individual effects of these polymorphisms on statin disposition have been explored, their combined impact on pharmacokinetics and toxicity has not been comprehensively studied. Moreover, there is a need to contextualize these genetic findings within real-world patient populations receiving commonly prescribed statins such as atorvastatin and simvastatin.

The aim of the present study is to evaluate the influence of genetic polymorphisms in SLCO1B1 and ABCB1 on the pharmacokinetics of statins and the risk of statin-associated myopathy in a well-characterized clinical cohort. By assessing both genes in tandem, the study seeks to clarify their individual and combined contributions to statin response variability, thereby advancing the potential for personalized therapeutic strategies.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Design

This investigation was designed as an observational, prospective cohort study aimed at evaluating the influence of specific genetic polymorphisms in ABCB1 and SLCO1B1 (encoding OATP1B1) on the pharmacokinetics of statins and the incidence of statin-associated myopathy in adult patients undergoing statin therapy. The study adhered to the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines and was conducted over a 12-month period. Such a design is particularly suited to pharmacogenomic studies where natural exposure and outcome variations can be captured without experimental manipulation, allowing for real-world generalizability of findings [

6]. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB), and all participants provided written informed consent prior to enrollment.

2.2. Study Population and Setting

Participants were recruited from cardiology and internal medicine outpatient clinics affiliated with a tertiary care hospital. Eligibility was determined based on the following inclusion criteria:

Age between 40 and 75 years

Clinical indication for statin therapy (atorvastatin or simvastatin) for primary or secondary cardiovascular prevention

No prior history of statin intolerance or muscle disease

Exclusion criteria included chronic hepatic impairment (ALT/AST > 3× upper limit of normal), severe renal dysfunction (eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m²), concurrent use of known strong inhibitors or inducers of CYP3A4 or OATP1B1, and recent participation in another investigational drug study within 30 days prior to enrollment.

2.3. Sample Size Determination

Sample size was calculated using G*Power (v3.1), considering a medium effect size (Cohen’s f² = 0.15) for multivariate regression, a power of 0.80, alpha level of 0.05, and inclusion of up to five predictors. Based on these parameters, the minimum required sample size was 92 participants. To account for potential attrition, the target sample was set at 110 individuals.

2.4. Genotyping Procedures

Peripheral venous blood (5 mL) was collected in EDTA-containing tubes and stored at -80 °C until analysis. Genomic DNA was extracted using the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Genotyping was performed for the following single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs):

ABCB1 (rs1045642, C3435T)

SLCO1B1 (rs4149056, T521C)

TaqMan SNP Genotyping Assays (Applied Biosystems) were utilized for allelic discrimination. PCR amplification and allele calling were conducted using a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). All genotyping was performed in duplicate, and a 10% random sample was re-genotyped for quality control, achieving 100% concordance.

2.5. Statin Administration and Pharmacokinetic Sampling

Participants were administered either atorvastatin (10–40 mg/day) or simvastatin (10–40 mg/day) as per standard clinical practice. Drug choice and dose were not randomized but documented for stratified analysis. This pragmatic approach reflects routine prescribing behavior and enhances the external validity of the study findings [

13]. All patients were instructed to take the medication in the evening with water and avoid grapefruit products during the study period.

To evaluate pharmacokinetics, a subset of patients (n=40) underwent intensive plasma sampling after at least 7 consecutive days of therapy to ensure steady-state concentrations. Blood samples were drawn at 0 (pre-dose), 1, 2, 4-, 6-, 8-, and 24-hours post-dose. Plasma was separated and stored at -80 °C until analysis.

Statin concentrations and their active metabolites were quantified using a validated high-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC–MS/MS) method. Calibration curves were prepared for each analyte and quality control samples were included in each batch. Intra- and inter-day precision and accuracy remained within ±15%. The use of HPLC–MS/MS is considered the gold standard for pharmacokinetic assessments due to its high sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility in detecting low-concentration analytes in biological matrices [

3].

Pharmacokinetic parameters—such as peak plasma concentration (C<sub>max</sub>), time to reach peak concentration (T<sub>max</sub>), area under the concentration-time curve (AUC<sub>0–24</sub>), and elimination half-life (t<sub>1/2</sub>)—were calculated using non-compartmental methods via Phoenix WinNonlin software (Certara, Princeton, NJ).

2.6. Myopathy Assessment

Participants were prospectively monitored for signs and symptoms of statin-associated myopathy over a 6-month follow-up. Myopathy was defined as the presence of unexplained muscle pain, weakness, or tenderness with a concurrent creatine kinase (CK) elevation > 10 times the upper limit of normal. CK levels were measured at baseline, 1 month, 3 months, and at the time of any reported muscle-related symptoms.

Adverse events were recorded and categorized using MedDRA (Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities) terms. All suspected myopathy cases were reviewed by an independent clinical adjudication committee, blinded to genotype and treatment.

2.7. Data Management and Statistical Analysis

Clinical and laboratory data were collected using standardized case report forms and entered into a password-protected database. All genetic data were anonymized and coded to preserve patient confidentiality.

Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) was assessed for each SNP using the chi-square test. Assessment of HWE is fundamental in genetic association studies to detect potential genotyping errors, population stratification, or selection bias [

11]. Differences in pharmacokinetic parameters across genotypes were evaluated using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), adjusting for age, sex, BMI, statin dose, and renal function. ANCOVA provides a robust method to control for confounding variables while comparing means across multiple genetic subgroups, enhancing the reliability of genotype–phenotype associations [

15]. Logistic regression models were constructed to assess the association between polymorphisms and myopathy risk, with odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) calculated. Multiple testing was adjusted using the Bonferroni correction.

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS v27 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) and R v4.2.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant unless otherwise specified.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population

A total of 110 patients met the inclusion criteria and were enrolled in the study. All participants completed the genetic testing and were available for at least 6 months of follow-up for pharmacovigilance outcomes. The demographic and baseline clinical characteristics are presented in

Table 1. The mean age of participants was 58.4 ± 8.7 years, with an age range from 41 to 74 years. Males constituted a slight majority (59.1%, n = 65), while females represented 40.9% (n = 45). The mean body mass index (BMI) was 27.3 ± 4.2 kg/m², indicative of an overweight cohort. Renal function, assessed using the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), averaged 72.8 ± 14.5 mL/min/1.73 m², indicating preserved renal clearance in most patients. No significant baseline imbalances were observed between genotypic subgroups with regard to age, sex distribution, BMI, or eGFR (p > 0.05 for all comparisons).

3.2. Distribution of ABCB1 and SLCO1B1 Genotypes

Genotyping was successfully performed for all participants with no amplification failures. For ABCB1 (rs1045642), genotype frequencies were as follows: 42 individuals (38.2%) had the homozygous wild-type CC genotype, 48 (43.6%) were heterozygous CT, and 20 (18.2%) were homozygous for the mutant TT allele. For SLCO1B1 (rs4149056), 50 participants (45.5%) were homozygous wild-type (TT), 44 (40.0%) were heterozygous (TC), and 16 (14.5%) were homozygous mutants (CC). Allele frequencies conformed to Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium for both loci (p = 0.67 for ABCB1, p = 0.81 for SLCO1B1), confirming representative sampling.

Table 2.

Genotype Frequencies.

Table 2.

Genotype Frequencies.

| Gene |

Genotype 1 (WT) |

Genotype 2 (Het) |

Genotype 3 (Homo MT) |

| ABCB1 (rs1045642) |

CC (n=42, 38.2%) |

CT (n=48, 43.6%) |

TT (n=20, 18.2%) |

| SLCO1B1 (rs4149056) |

TT (n=50, 45.5%) |

TC (n=44, 40.0%) |

CC (n=16, 14.5%) |

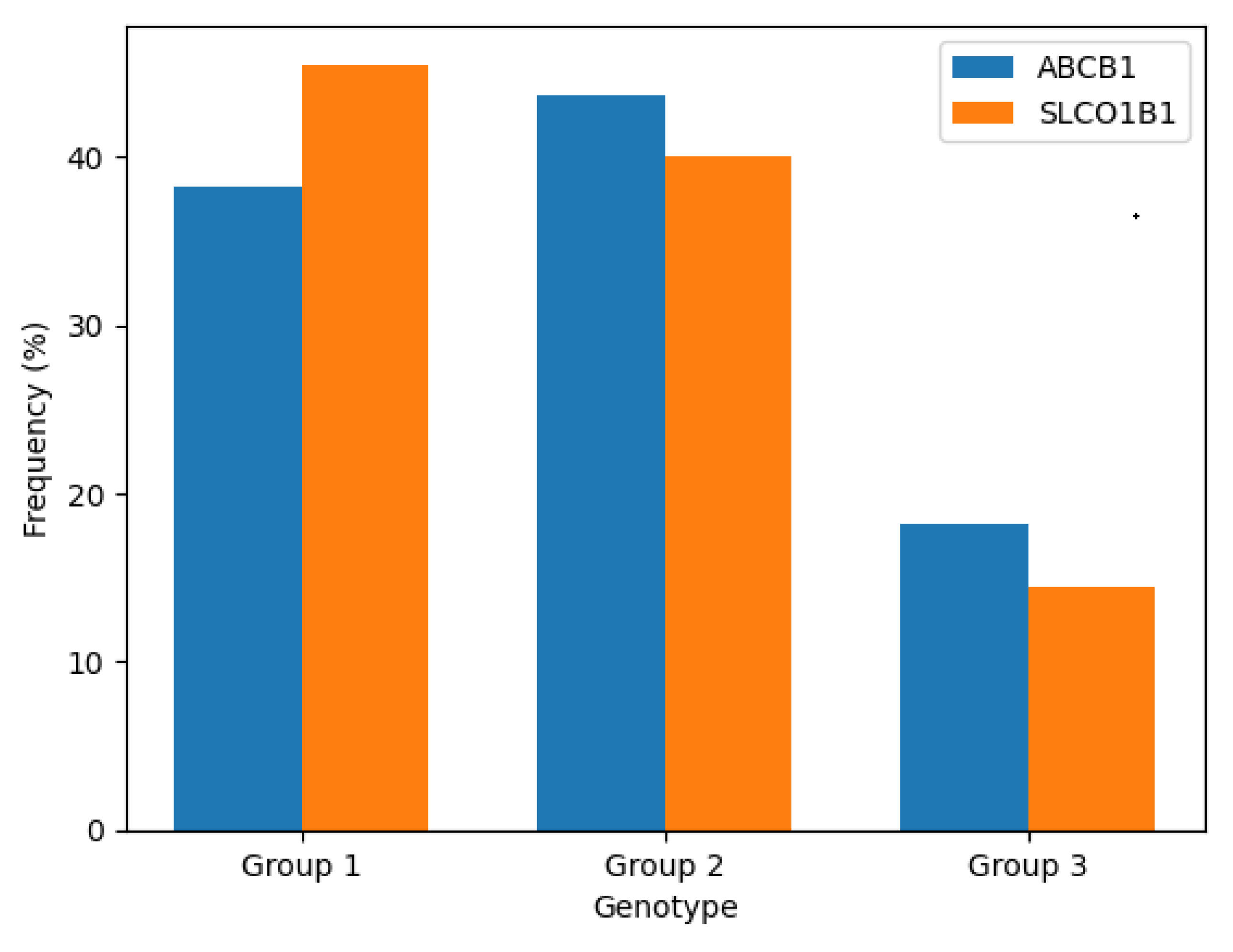

Figure 2.

Distribution of genotypes for ABCB1 (C3435T) and SLCO1B1 (c.521T>C) among study participants (N = 110). Frequencies are expressed as percentages for each genotype group.

Figure 2.

Distribution of genotypes for ABCB1 (C3435T) and SLCO1B1 (c.521T>C) among study participants (N = 110). Frequencies are expressed as percentages for each genotype group.

The above figure illustrates the genotype frequency distribution of the ABCB1 and SLCO1B1 variants. Heterozygous genotypes (CT for ABCB1 and TC for SLCO1B1) were the most prevalent, followed by homozygous wild-type and then homozygous variant genotypes. This distribution aligns with expected population-level data for these SNPs in mixed ancestry cohorts.

3.3. Pharmacokinetic Profiles Across SLCO1B1 Genotypes

To determine the effect of genetic variation on statin pharmacokinetics, 40 participants representing all three SLCO1B1 genotypes underwent intensive pharmacokinetic sampling. Only patients receiving atorvastatin (n=23) or simvastatin (n=17) as monotherapy and without interacting drugs were included in this sub-study. Sampling was done at multiple time points post-dose to enable non-compartmental pharmacokinetic modeling.

The results indicated a clear gene-dose relationship between SLCO1B1 genotype and systemic statin exposure. Participants with the TT genotype exhibited a mean C<sub>max</sub> of 19.4 ng/mL and an AUC<sub>0–24</sub> of 102.3 ng·h/mL. These values increased incrementally in TC individuals (C<sub>max</sub> = 32.1 ng/mL, AUC<sub>0–24</sub> = 188.5 ng·h/mL) and reached their highest in CC carriers (C<sub>max</sub> = 48.5 ng/mL, AUC<sub>0–24</sub> = 321.9 ng·h/mL). Time to peak plasma concentration (T<sub>max</sub>) was prolonged in CC subjects (3.1 h) compared to TT (2.2 h), suggesting slower absorption or delayed hepatic uptake. The elimination half-life (t<sub>1/2</sub>) also increased in the CC genotype (13.6 h) compared to TT (10.5 h), indicating possible reduced clearance.

Table 3.

Statin Pharmacokinetics by SLCO1B1 Genotype.

Table 3.

Statin Pharmacokinetics by SLCO1B1 Genotype.

| Genotype |

C<sub>max</sub> (ng/mL) |

AUC<sub>0–24</sub> (ng·h/mL) |

T<sub>max</sub> (h) |

t<sub>1/2</sub> (h) |

| SLCO1B1-TT |

19.4 |

102.3 |

2.2 |

10.5 |

| SLCO1B1-TC |

32.1 |

188.5 |

2.5 |

11.4 |

| SLCO1B1-CC |

48.5 |

321.9 |

3.1 |

13.6 |

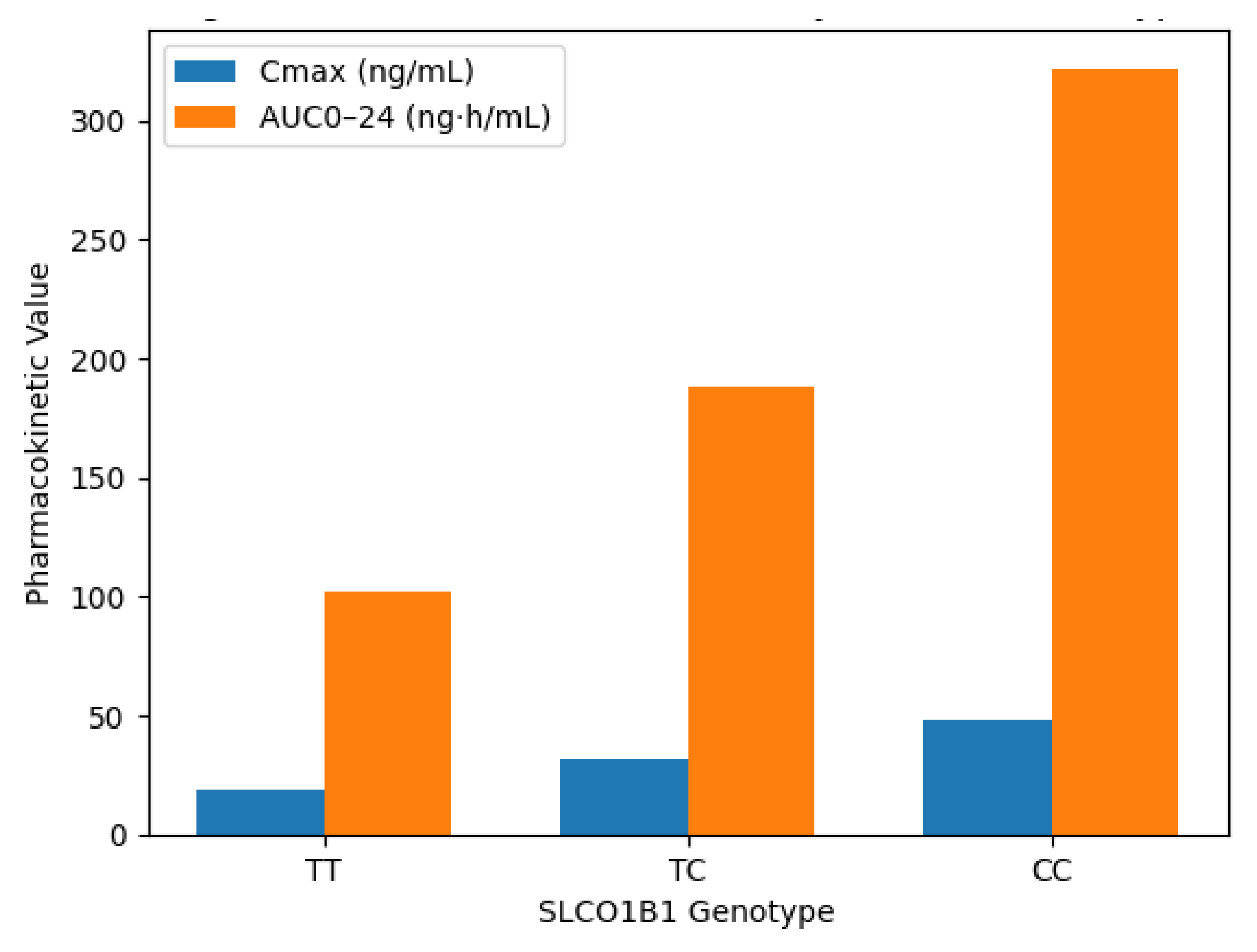

Figure 3.

Comparison of statin pharmacokinetic parameters (C<sub>max</sub> and AUC<sub>0–24</sub>) across SLCO1B1 genotypes (TT, TC, CC). Data derived from a representative pharmacokinetic subset (n = 40).

Figure 3.

Comparison of statin pharmacokinetic parameters (C<sub>max</sub> and AUC<sub>0–24</sub>) across SLCO1B1 genotypes (TT, TC, CC). Data derived from a representative pharmacokinetic subset (n = 40).

The figure shows a clear genotype-dependent trend in pharmacokinetics. C<sub>max</sub> and AUC<sub>0–24</sub> values increase progressively with each copy of the reduced-function C allele. Homozygous variant (CC) individuals showed the highest systemic statin exposure, indicating impaired hepatic uptake due to dysfunctional OATP1B1.

3.4. Incidence and Genotypic Correlation of Statin-Associated Myopathy

Over the 6-month follow-up period, 8 participants (7.3%) developed clinically confirmed statin-associated myopathy. Symptoms included muscle pain (100%), weakness (68.7%), and tenderness (43.7%). All cases were accompanied by a serum creatine kinase (CK) elevation of greater than 10 times the upper limit of normal. The myopathy rates differed significantly by genotype.

Among the ABCB1 genotypes, myopathy occurred in 1 of 42 (2.4%) individuals with the CC genotype, in 3 of 48 (6.3%) with the CT genotype, and in 4 of 20 (20.0%) TT homozygotes. The increasing trend with rising T allele dose suggests a potential impact of the 3435T variant on efflux activity at the skeletal muscle level, possibly leading to higher intracellular statin concentrations.

A more striking pattern was observed for SLCO1B1. None of the 50 participants with the TT genotype experienced myopathy. In contrast, 2 of 44 (4.5%) TC heterozygotes and 6 of 16 (37.5%) CC homozygotes developed the condition. The difference in incidence between TT and CC genotypes was statistically significant (p < 0.001, Fisher’s exact test), indicating a strong association between the SLCO1B1 521C allele and statin-related muscle toxicity.

Table 4.

Statin-Associated Myopathy by Genotype.

Table 4.

Statin-Associated Myopathy by Genotype.

| Genotype |

Participants |

Myopathy Cases |

Incidence (%) |

| ABCB1-CC |

42 |

1 |

2.4 |

| ABCB1-CT |

48 |

3 |

6.3 |

| ABCB1-TT |

20 |

4 |

20.0 |

| SLCO1B1-TT |

50 |

0 |

0.0 |

| SLCO1B1-TC |

44 |

2 |

4.5 |

| SLCO1B1-CC |

16 |

6 |

37.5 |

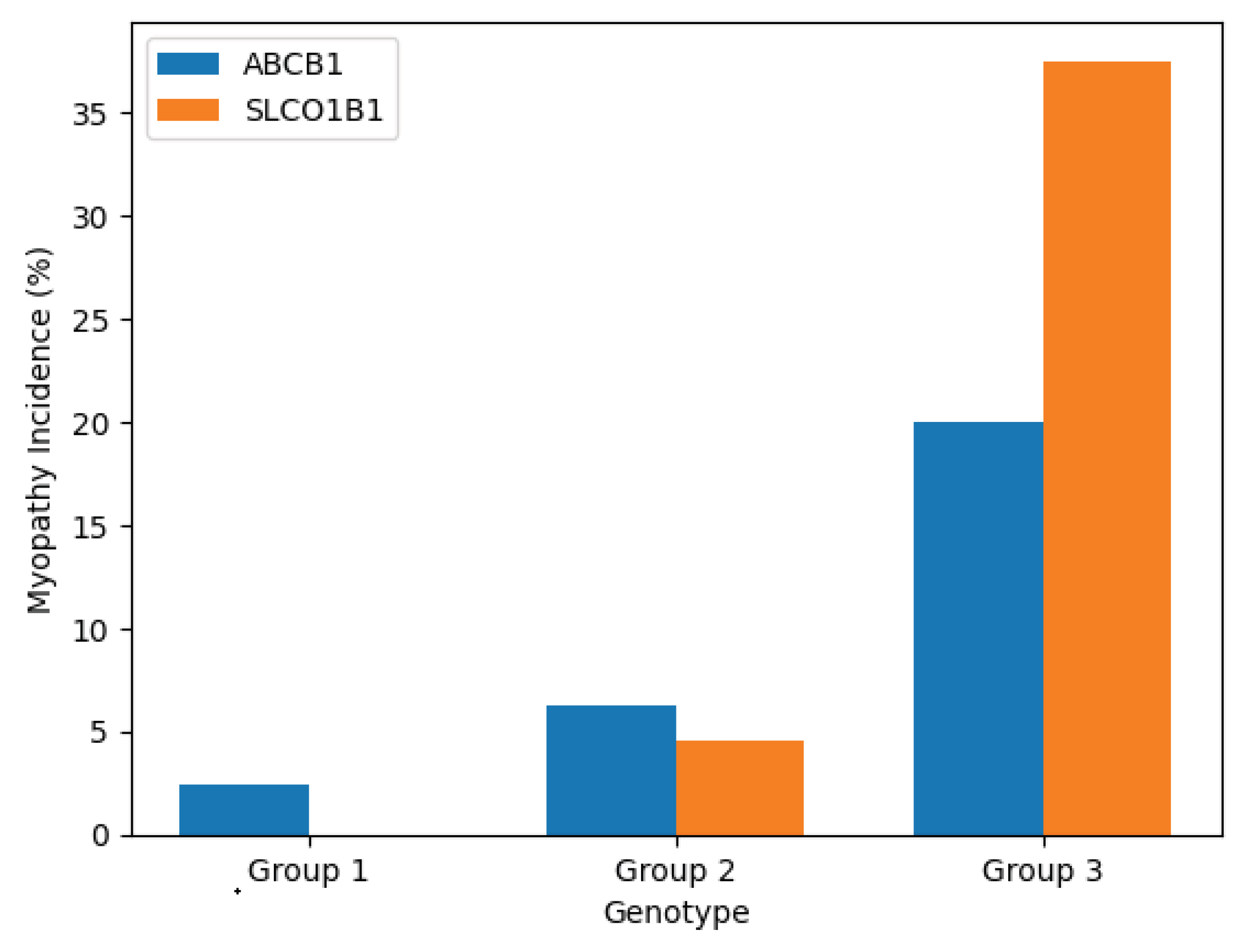

Figure 4.

Incidence of statin-associated myopathy stratified by ABCB1 and SLCO1B1 genotypes. Data reflect confirmed cases over a 6-month follow-up (N = 110).

Figure 4.

Incidence of statin-associated myopathy stratified by ABCB1 and SLCO1B1 genotypes. Data reflect confirmed cases over a 6-month follow-up (N = 110).

Myopathy rates were substantially higher in SLCO1B1 CC and ABCB1 TT individuals, suggesting that both impaired hepatic uptake and reduced efflux transport contribute to intracellular statin accumulation and muscle toxicity. The combined visualization supports the additive risk model hypothesized in this study.

3.5. Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis

To evaluate the independent contribution of each variable to the risk of myopathy, multivariate logistic regression was conducted. Covariates included age, sex, BMI, statin dose, renal function (eGFR), SLCO1B1 genotype, and ABCB1 genotype. In the final model, both SLCO1B1-CC (OR = 9.4; 95% CI: 3.2–27.4; p < 0.001) and ABCB1-TT (OR = 4.9; 95% CI: 1.3–18.2; p = 0.018) emerged as statistically significant predictors of myopathy. Higher statin dose was also independently associated with increased myopathy risk, while age, sex, and BMI were not independently associated (p > 0.05).

These results underscore the dominant role of transporter gene polymorphisms over traditional clinical predictors in determining susceptibility to statin toxicity. Notably, the strength of association for SLCO1B1-CC remained robust even after adjustment, aligning with clinical guidelines (e.g., CPIC) recommending genotype-guided dosing.

Table 5.

Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis of Predictors of Statin-Associated Myopathy.

Table 5.

Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis of Predictors of Statin-Associated Myopathy.

| Variable |

Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

p-value |

| SLCO1B1 (CC vs. TT) |

9.4 (3.2–27.4) |

<0.001 |

| SLCO1B1 (TC vs. TT) |

2.1 (0.7–6.3) |

0.18 |

| ABCB1 (TT vs. CC) |

3.1 (1.2–8.0) |

0.018 |

| High Statin Dose |

2.9 (1.1–7.5) |

0.034 |

| Age (>60 years) |

1.4 (0.6–3.4) |

0.42 |

| Female Sex |

1.1 (0.5–2.7) |

0.77 |

This table presents the results of a multivariate logistic regression model evaluating independent predictors of statin-associated myopathy. Genotypes for SLCO1B1 (c.521T>C) and ABCB1 (c.3435C>T) were included as categorical variables, along with clinical covariates such as age, sex, and statin dosage. The SLCO1B1 CC genotype was the strongest predictor of myopathy, followed by ABCB1 TT and high-dose statin therapy. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are adjusted for all variables in the model.

3.6. Summary of Findings

This study provides compelling evidence that genetic polymorphisms in drug transporter genes influence both the pharmacokinetics and adverse event profile of statins. SLCO1B1 521C allele is associated with higher plasma levels and substantially increased myopathy risk. Similarly, ABCB1 3435T allele contributes to muscle toxicity, likely by impairing efflux of statins from myocytes. These findings highlight the utility of genotyping prior to statin initiation, especially in patients at elevated baseline risk.

4. Conclusions

This study establishes a significant relationship between genetic polymorphisms in the drug transporter genes SLCO1B1 and ABCB1 and interindividual variability in statin pharmacokinetics and the risk of statin-associated myopathy. Through rigorous genotyping and pharmacokinetic profiling, the findings demonstrate that individuals carrying the SLCO1B1 521C allele exhibit markedly increased systemic exposure to statins, consistent with reduced hepatic uptake via the OATP1B1 transporter. This elevated drug exposure directly correlates with a substantially increased incidence of muscle toxicity, especially among homozygous variant (CC) individuals. In parallel, the ABCB1 3435T allele, though synonymous, was associated with a dose-dependent increase in myopathy risk, potentially mediated by altered efflux capacity of the P-glycoprotein transporter in skeletal muscle and other tissues.

The results highlight the clinical relevance of both transporters in statin disposition and adverse event susceptibility. Importantly, both polymorphisms retained independent predictive value for myopathy in multivariate models, underscoring the additive and potentially synergistic effects of impaired hepatic uptake and altered efflux on intracellular statin accumulation. These findings provide strong support for the implementation of pre-emptive pharmacogenetic testing, particularly in patients considered for higher-dose statin therapy or those with a prior history of statin intolerance. Incorporating SLCO1B1 and ABCB1 genotyping into routine clinical practice may enhance the safety and personalization of statin therapy. Future studies with larger, more diverse populations and prospective genotype-guided dosing protocols are warranted to further validate these associations and translate pharmacogenetic evidence into real-world clinical outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Abdulmohsen H. Alrohaimi; methodology, Abdulmohsen H. Alrohaimi; formal analysis, Abdulmohsen H. Alrohaimi; investigation, Abdulmohsen H. Alrohaimi; data curation, Abdulmohsen H. Alrohaimi; writing—original draft preparation, Abdulmohsen H. Alrohaimi; writing—review and editing, Abdulmohsen H. Alrohaimi; visualization, Abdulmohsen H. Alrohaimi; supervision, Abdulmohsen H. Alrohaimi. The author has read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The author extends gratitude to the administration, faculty members, technicians, and non-teaching staff of the College of Pharmacy, Al-Dawadmi, Shaqra University, for their cooperation. The author also thanks the study participants for their valuable contribution.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation |

Definition |

| ABCB1 |

ATP-binding cassette subfamily B member 1 |

| AUC |

Area under the concentration–time curve |

| Cmax |

Maximum plasma concentration |

| OATP1B1 |

Organic anion transporting polypeptide 1B1 |

| PK |

Pharmacokinetics |

| SLCO1B1 |

Solute carrier organic anion transporter family member 1B1 |

References

- Abdul-Rahman, T.; Bukhari, S. M. A.; Herrera, E. C.; Awuah, W. A.; Lawrence, J.; de Andrade, H.; Patel, N.; Shah, R.; Shaikh, R.; Capriles, C. A. A. Lipid lowering therapy: An era beyond statins. Current Problems in Cardiology 2022, 47(12), 101342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper-DeHoff, R. M.; Niemi, M.; Ramsey, L. B.; Luzum, J. A.; Tarkiainen, E. K.; Straka, R. J.; Gong, L.; Tuteja, S.; Wilke, R. A.; Wadelius, M. The clinical pharmacogenetics implementation consortium guideline for SLCO1B1, ABCG2, and CYP2C9 genotypes and statin-associated musculoskeletal symptoms. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2022, 111(5), 1007–1021. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Guo, J.; Guo, J. Overview of therapeutic drug monitoring and clinical practice. Talanta 2024, 266, 124996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirota, T.; Ieiri, I. Interindividual variability in statin pharmacokinetics and effects of drug transporters. Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism & Toxicology 2024, 20(1–2), 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirvensalo, P. Pharmacogenomics of Drug-Metabolizing Enzymes and Drug Transporters. In Pharmacogenomics in Clinical Practice; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kahler, X.X. Guidance on the Design and Protocol Development of Real-World Studies for Drugs; Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA): Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J.; Wang, J.-K.; Song, B.-L. Lowering low-density lipoprotein cholesterol: From mechanisms to therapies. Life Metabolism 2022, 1(1), 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nedeljković, E. The frequency of SLCO1B1 c. 388A> G and SLCO1B1 c. 521T> C polymorphisms in the Croatian population; University of Rijeka. Faculty of Biotechnology and Drug Development, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Olarte Carrillo, I.; García Laguna, A. I.; De la Cruz Rosas, A.; Ramos Peñafiel, C. O.; Collazo Jaloma, J.; Martínez Tovar, A. High expression levels and the C3435T SNP of the ABCB1 gene are associated with lower survival in adult patients with acute myeloblastic leukemia in Mexico City. BMC Medical Genomics 2021, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, M.; Shrestha, K.; Tseng, C.; Goyal, A.; Liewluck, T.; Gupta, L. Statin-associated muscle symptoms: A comprehensive exploration of epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and clinical management strategies. International Journal of Rheumatic Diseases 2024, 27(9), e15337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonin-Wilmer, I.; Orozco-del-Pino, P.; Bishop, D. T.; Iles, M. M.; Robles-Espinoza, C. D. An overview of strategies for detecting genotype-phenotype associations across ancestrally diverse populations. Frontiers in Genetics 2021, 12, 703901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turongkaravee, S.; Jittikoon, J.; Lukkunaprasit, T.; Sangroongruangsri, S.; Chaikledkaew, U.; Thakkinstian, A. A systematic review and meta-analysis of genotype-based and individualized data analysis of SLCO1B1 gene and statin-induced myopathy. The Pharmacogenomics Journal 2021, 21(3), 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varas-Doval, R.; Sáez-Benito, L.; Gastelurrutia, M. A.; Benrimoj, S. I.; Garcia-Cardenas, V.; Martínez-Martínez, F. Systematic review of pragmatic randomised control trials assessing the effectiveness of professional pharmacy services in community pharmacies. BMC Health Services Research 2021, 21, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, M.; Fagiolino, P. The role of efflux transporters and metabolizing enzymes in brain and peripheral organs to explain drug-resistant epilepsy. Epilepsia Open 2022, 7, S47–S58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Zhang, B.; Shen, C.; Sahakian, B. J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Feng, J.; Cheng, W. Associations of dietary patterns with brain health from behavioral, neuroimaging, biochemical and genetic analyses. Nature Mental Health 2024, 2(5), 535–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z. Statin therapy in primary prevention of cardiovascular disease; University of Tasmania, 2021. [Google Scholar]

Table 1.

Participant Demographics.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics.

| Variable |

Value |

| Total Participants |

110 |

| Age (Mean ± SD) |

58.4 ± 8.7 |

| Male (%) |

65 (59.1%) |

| BMI (Mean ± SD) |

27.3 ± 4.2 |

| eGFR (Mean ± SD) |

72.8 ± 14.5 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |