1. Introduction

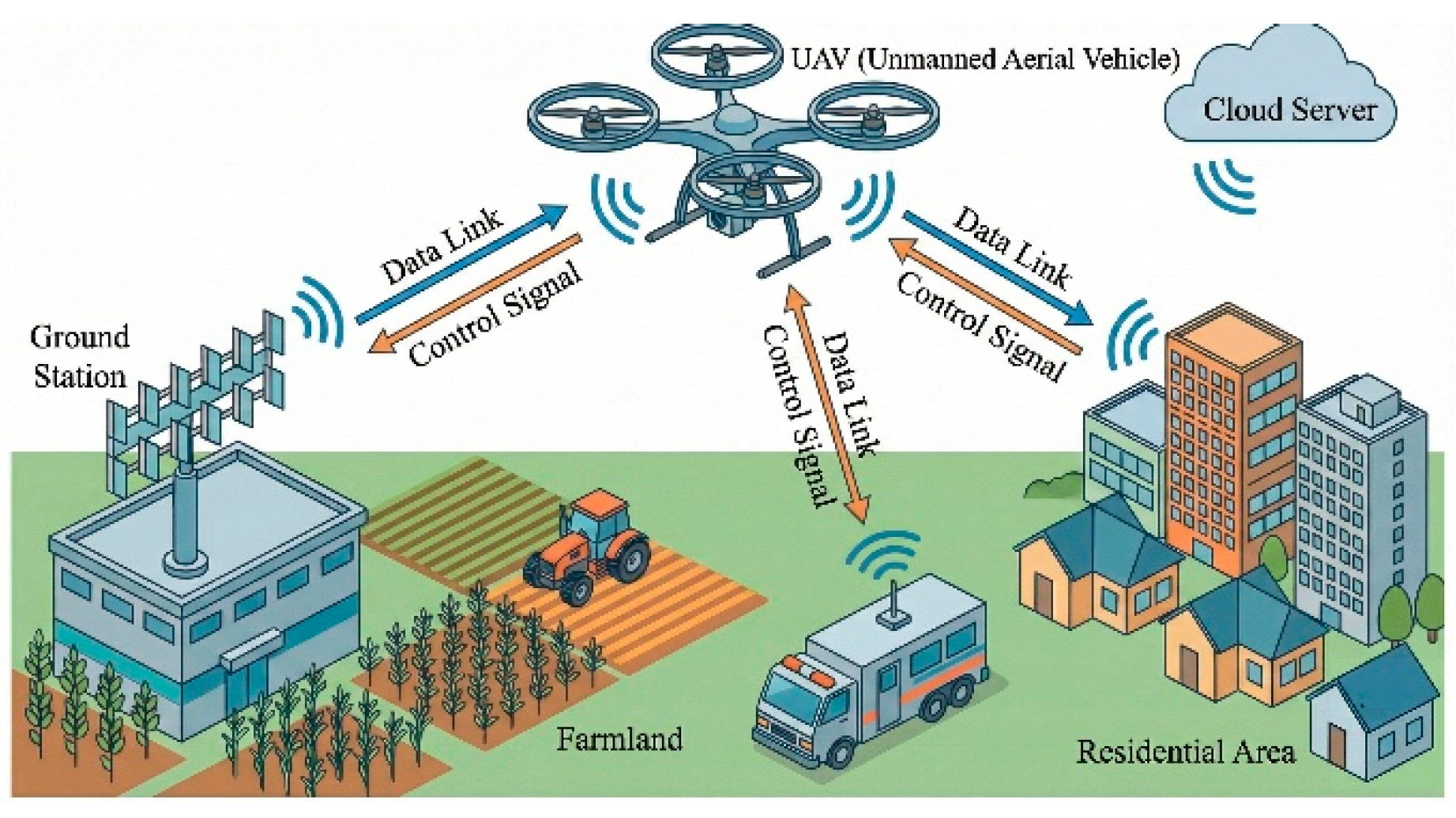

With the expanding application of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), or drone, the operational reliability of their communication links, particularly anti-jamming capability, has become increasingly critical. Leveraging the polarization characteristics of electromagnetic waves presents a significant technical approach to address such challenges. The polarization properties of antennas, especially the ability to dynamically reconfigure polarization in response to varying operational scenarios—known as polarization reconfigurability—constitute a key research focus in this field. The application scenario is illustrated in

Figure 1.

The rapid deployment of 5G and the ongoing evolution towards 6G technology impose increasingly stringent requirements on terminal antennas, compelling a focused research effort on achieving miniaturization, wide impedance bandwidth, high gain, and adaptive functionality within extremely confined spaces. The limited physical size of modern mobile devices necessitates antenna designs that are not only compact but also capable of supporting high data rates and reliable connectivity. Traditional microstrip antennas, while low-profile and easy to integrate, fundamentally struggle to meet these multi-faceted demands due to their inherent limitations in bandwidth, gain, and functional agility [

1].

Metasurface antennas, which leverage two-dimensional artificial electromagnetic structures composed of subwavelength unit cells, have emerged as a profoundly promising alternative [

2]. They offer a unique combination of a low profile, high integration potential, and exceptional control over wavefronts and polarization states, enabling performance characteristics that are difficult to achieve with conventional designs. Significant research efforts have been directed towards addressing three critical challenges in antenna technology for modern wireless systems [

3,

4]. The first is miniaturization, which is paramount for integration into compact smart terminals and internet of things (IoT) devices. Techniques such as employing slotting and branch-loading on patches, as well as incorporating defected ground structures (DGS) [

5], have been effectively used to reduce antenna size and achieve multi-band operation. The second key area is the generation of circular polarization, which is highly desirable for its robustness against multipath fading and orientation mismatches between transmitting and receiving antennas [

6]. It has been proved that metasurfaces is exceptionally capable in this regard. It was often used as superstrates to transform a linearly polarized source into a radiator with wide axial ratio bandwidth [

7]. The critical research focus is reconfigurability [

8], which allows a single antenna to dynamically adapt to varying channel conditions and communication standards.

Polarization configurability, in particular, is crucial for optimizing signal quality, mitigating interference, and improving compatibility with diverse network infrastructures. Conventional reconfiguration techniques predominantly rely on active components like PIN diodes or varactors [

9]. However, these introduce well-documented drawbacks, including insertion loss, design complexity, DC power consumption, and the potential for harmonic radiation [

10].

To overcome these limitations, a promising direction is the development of passive, mechanically reconfigurable antennas. The design process for such innovative antennas can be rigorously guided by characteristic mode analysis (CMA) [

11], a powerful computational method for analyzing the inherent resonant properties (or characteristic modes) of a conducting structure without the influence of a specific excitation. The modal significance (MS) parameter serves as a central design metric within CMA [

12], quantitatively identifying the most significant resonant modes of the metasurface structure. This analytical approach provides deep physical insight and systematically guides the structural evolution towards optimal performance for both miniaturization and multi-polarization generation [

13]. Research has demonstrated that CMA can be effectively used to design metasurfaces that excite multiple broadside modes, which is essential for achieving wide impedance bandwidth.

Polarization-reconfigurable antennas represent an advanced form of antenna technology. They can dynamically switch or adjust their polarization states—such as linear or circular polarization—based on the channel environment and interference conditions. This capability allows the antenna to maintain optimal matching with the signal while maximizing interference suppression, which requires intelligent sensing and fast control algorithms.

In this approach, the principal contributions of this paper are as follows.

i) Systematic Design via CMA

The application of CMA and MS analysis to systematically design and optimize a miniaturized metasurface unit cell. This method enables a targeted adjustment of the structure's resonant properties, achieving a significant reduction in operational frequency and ensuring optimal excitation of desired modes for wideband performance.

ii) Low-Loss Polarization Switching

The introduction of a simple yet effective mechanical rotation mechanism applied to the metasurface layer. This passive approach enables low-loss and highly reliable polarization switching among left-hand circular polarization (LHCP), Linear Polarization (LP), and right-hand circular polarization (RHCP) states, effectively eliminating the losses and complexities associated with active electronic components.

iii) Experimental Validation of a High-Performance Antenna

The realization and experimental validation of a compact antenna prototype that demonstrates wide impedance bandwidth (>29.9%), stable gain across all polarization states (5.1 to 6.0 dBi), and high polarization purity. The excellent agreement between simulation and measurement confirms its potential as a robust solution for 5G terminal devices.

This approach aims to bridge the gap between the demanding requirements of modern wireless communication and the limitations of current antenna solutions by presenting a passively reconfigurable metasurface antenna that excels in size, bandwidth, and adaptive functionality. To achieve the above, the paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 introduces the design principles, including the theoretical basis of characteristic modes and MS analysis.

Section 3 presents simulation results. To verify our newly designed antenna, experimental results and analysis have been provided in

Section 4. Finally, we offer conclusions last section.

3. Overall Antenna Structure and Reconfiguration Mechanism

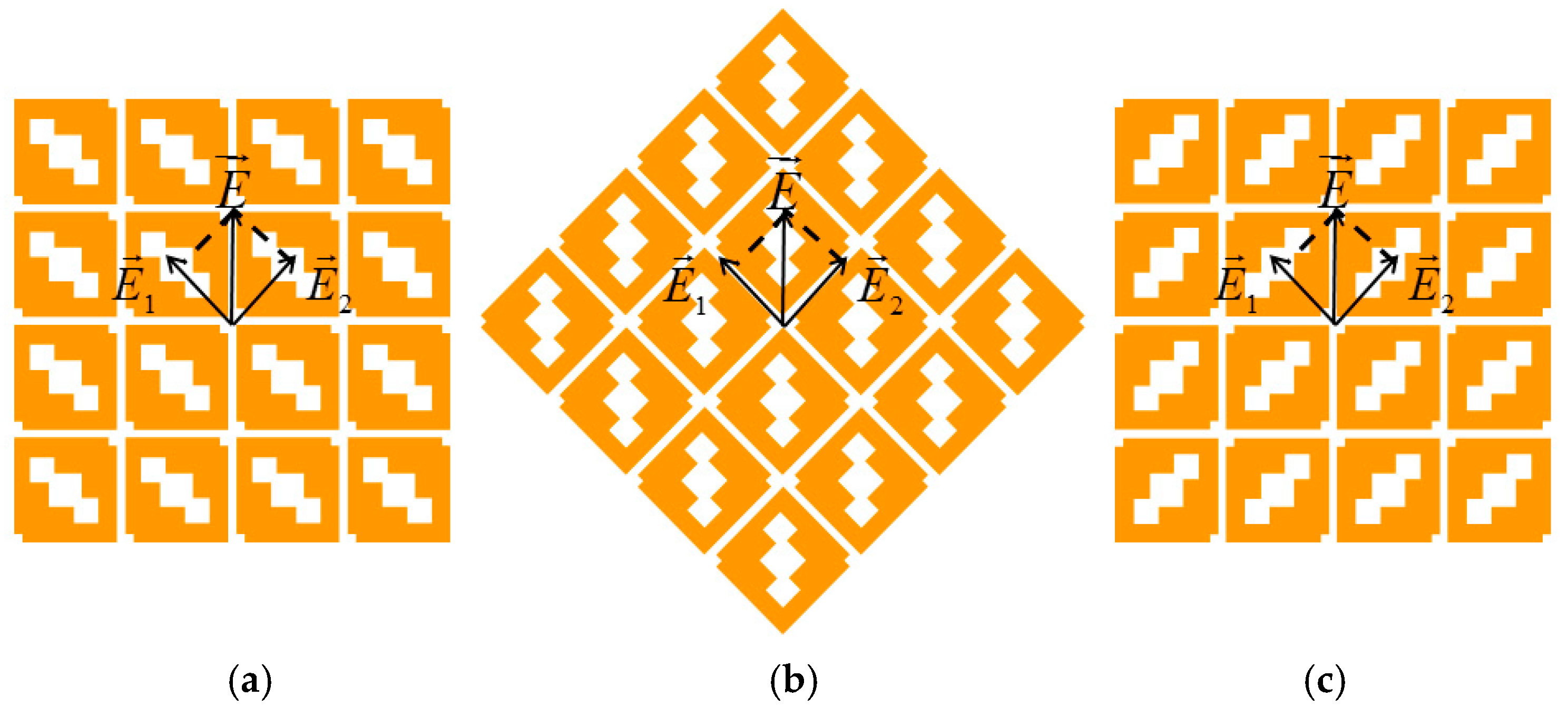

From analysis above, we can implement the polarization reconfiguration of the

metasurface antenna. Its principle, as shown in

Figure 14, can be concluded as follows.

i) 0° Position (LHCP). The metasurface orientation decomposes the incident field into orthogonal components (E1, E2). The asymmetric loading (hollows) introduces a 90° phase lead in E1 relative to E2, generating LHCP.

ii) 45° Rotation (LP). Rotating the metasurface by 45° equalizes the path lengths and phase for the orthogonal components, resulting in LP.

iii) 90° Rotation (RHCP). Further rotation to 90° reverses the phase relationship, causing E1 to lag E2 by 90°, generating RHCP.

When the metasurface is in its initial position, as shown in

Figure 14(a), the vector electric field E parallel to the x-axis is decomposed into two orthogonal components,

E1 and

E2. The amplitudes of these two components are equal. Since squares are etched on the metasurface, the two vector components travel paths of different electrical lengths, resulting in

E1 leading

E2 by a phase difference of 90 degrees, thus achieving the LHCP. When the metasurface structure is rotated by 45°, as shown in

Figure 14(b), the amplitudes and phases of

E1 and

E2 become equal, and the antenna realizes a conversion to linear polarization. When the metasurface structure is rotated by 90°, as shown in

Figure 14(c),

E1 now lags

E2 by a phase difference of 90°, and the antenna achieves conversion from LP to RHCP. The characteristic angles are shown in

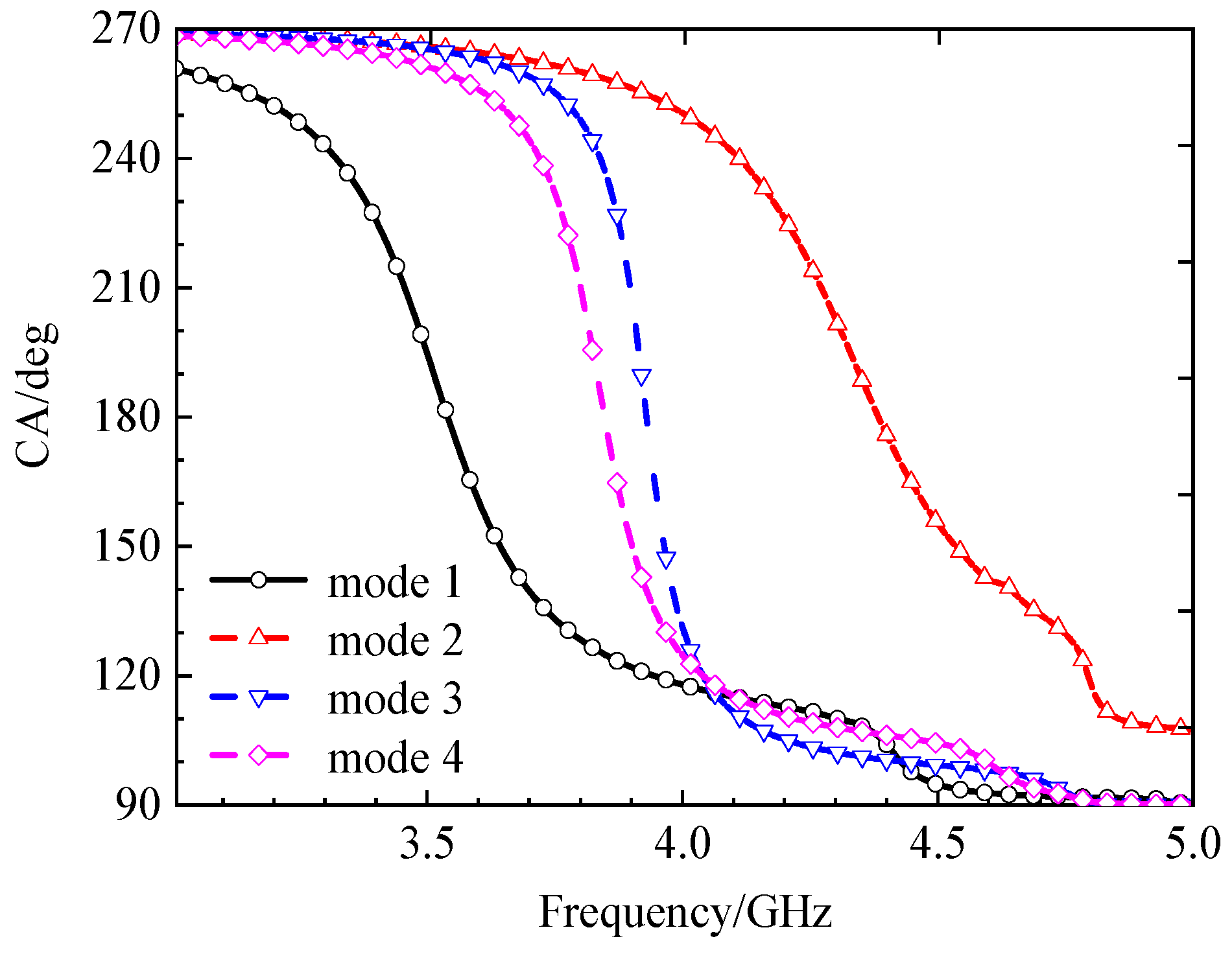

Figure 15. Within the frequency band of 3.62-4.25 GHz, the characteristic angles of mode 1 and mode 2 differ by approximately 90°. Combining the analysis of the surface currents and radiation patterns for each mode presented above, the antenna can achieve LHCP in its initial position. Furthermore, through mechanical rotation, it can achieve polarization conversion from LHCP to LP and then to RHCP.

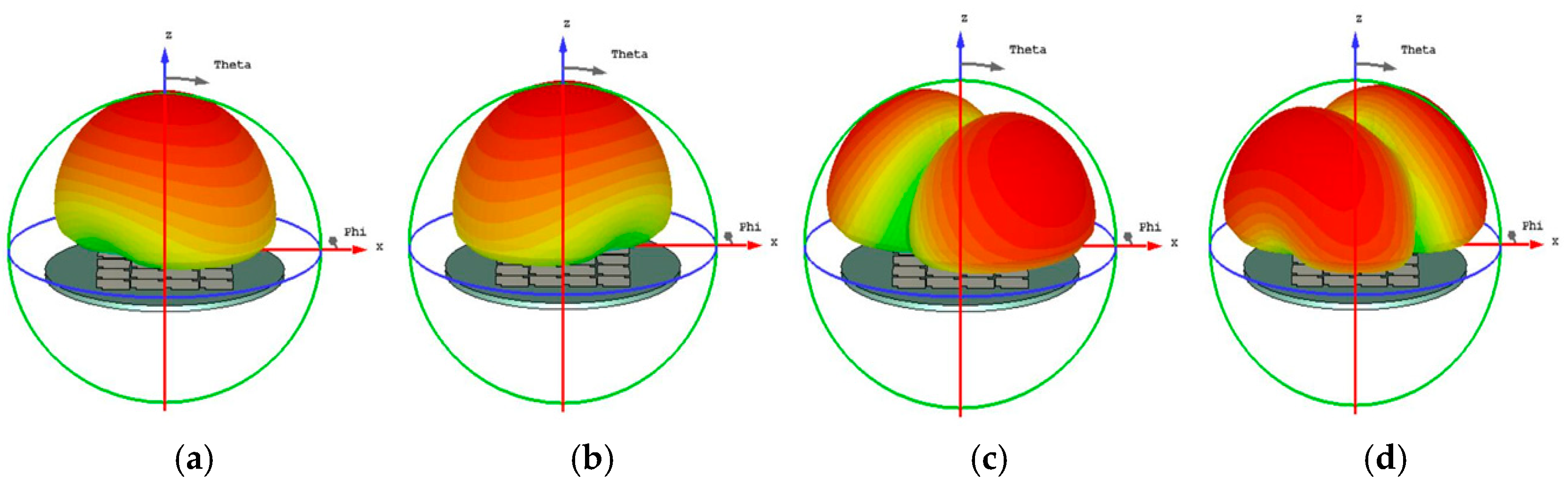

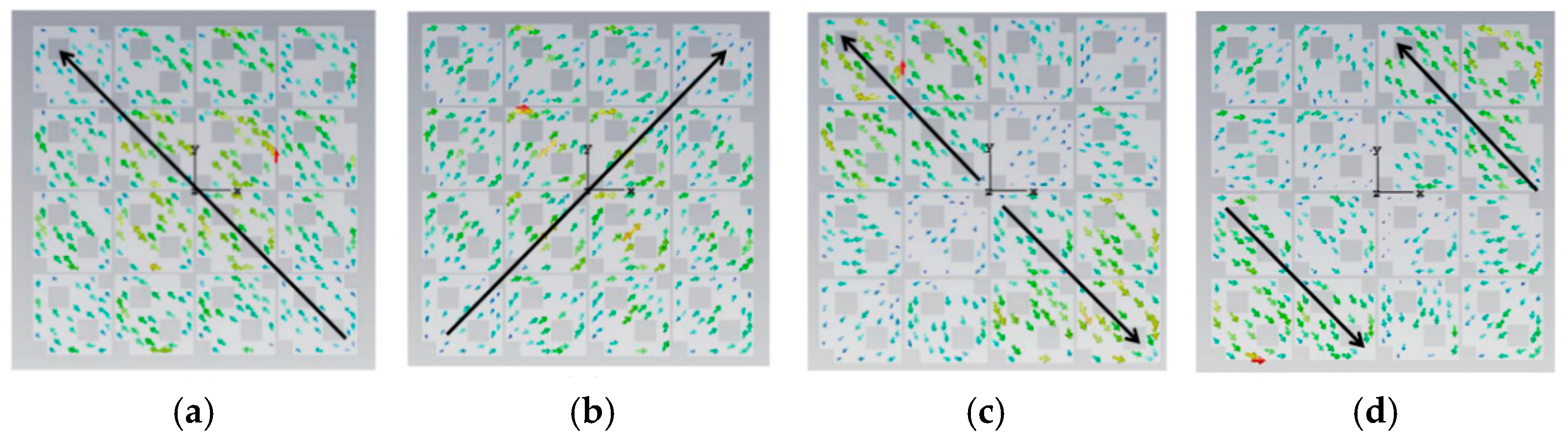

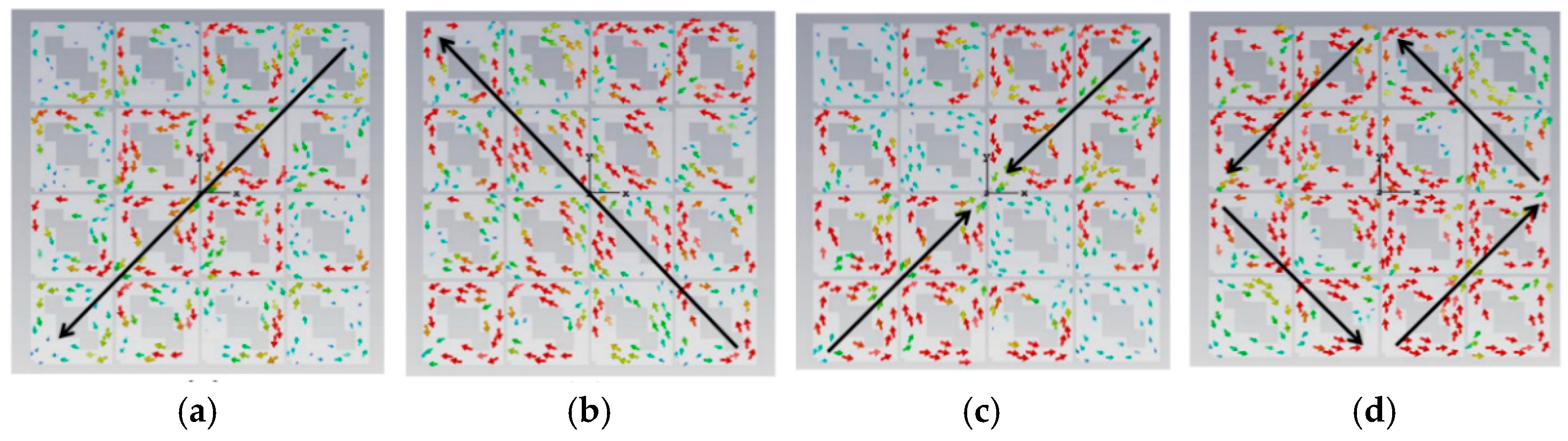

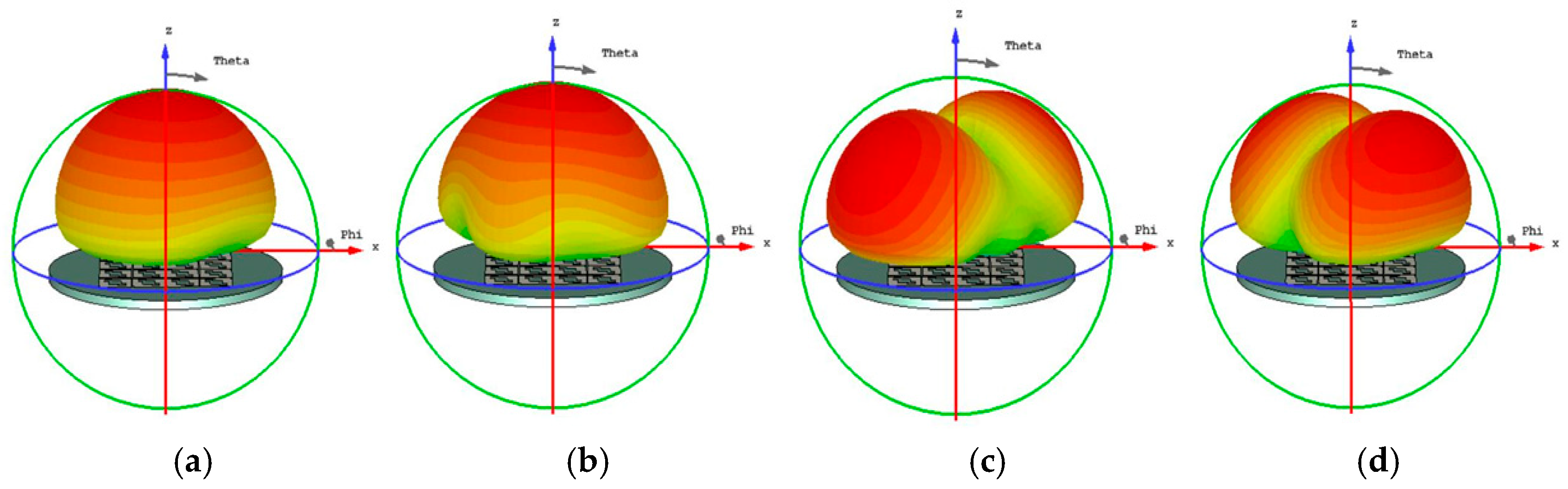

Having determined the structure and specific parameter values of the metasurface unit, the feasibility of achieving circular polarization with the metasurface is next analyzed based on the characteristic angles obtained from characteristic mode theory. The characteristic angle diagram of the metasurface is shown in

Figure 15. From 4.78 GHz to 4.98 GHz, there is an approximate 90-degree phase difference between mode 1 and mode 2. Combined with the 90-degree angular difference in the surface current flow directions of mode 1 and mode 2 shown in

Figure 11, and the identical radiation directions of mode 1 and mode 2 shown in

Figure 12, when a suitable excitation source is designed to excite these two modes of the metasurface, the conditions for achieving circular polarization are met because the amplitudes of the two modes are equal, the current flow directions differ by 90 degrees, and their phases differ by 90 degrees. Therefore, the antenna can exhibit circular polarization characteristics within this frequency band.

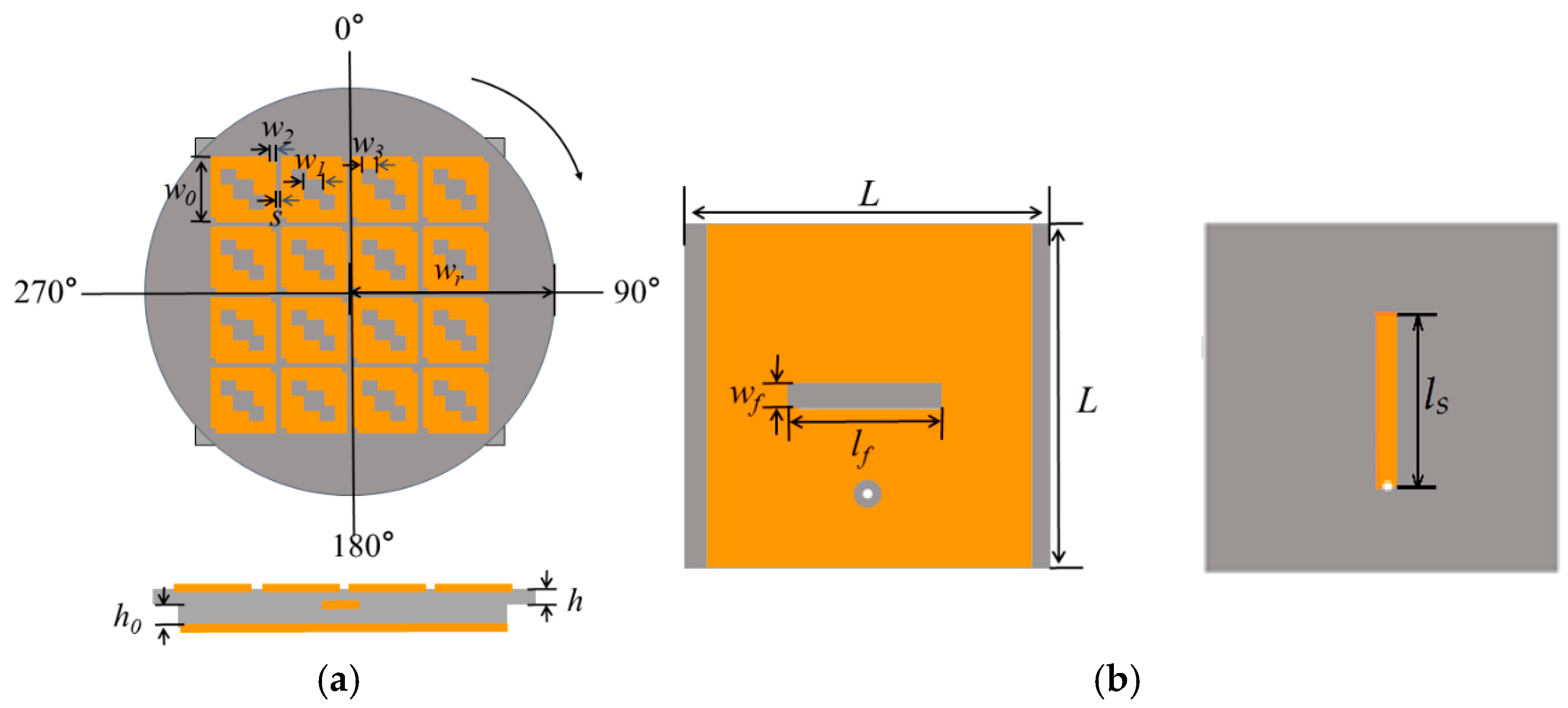

The complete antenna structure, illustrated in

Figure 16, comprises two FR4 dielectric substrates (

εr=4.4, tan

δ=0.02). Top Layer, A circular substrate carrying the optimized 4x4 units forming a metasurface. Bottom Layer, A square substrate featuring a slot-coupled feeding structure on its top side and a partial ground plane with a coupling slot on the bottom. A 50Ω coaxial probe feeds the antenna from underneath. This is a simple yet practical method for the low-profile antenna design of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), as shoun in

Figure 1 [

16]. The final size of designed antenna is listed in

Table 1 as follows.

A slot-coupled feed provides stable excitation across configurations. Key feed parameters (slot length lf, width wf, stub length ls and the same width with slot) were optimized via parametric studies in CST for impedance matching across all states. Polarization reconfiguration is achieved by mechanically rotating the top circular metasurface layer relative to the fixed bottom feed layer. The principle is illustrated as follows.

At 0° (LHCP State), the asymmetrical loading (three hollows) of the metasurface causes the incident field to decompose into two orthogonal components (E₁ and E₂). The structure introduces a 90° phase lead for E₁ relative to E₂, resulting in LHCP radiation.

At 45° (LP State), rotating the metasurface by 45° equalizes the path lengths and phase for the orthogonal components, leading to linear polarization.

At 90° (RHCP State), at this orientation, the phase relationship is reversed, causing E₁ to lag E₂ by 90°, thus generating RHCP.

Key parameters of the feeding structure (slot length lf, width wf, and stub length ls) were optimized via parametric studies in CST to ensure good impedance matching across all three polarization states.

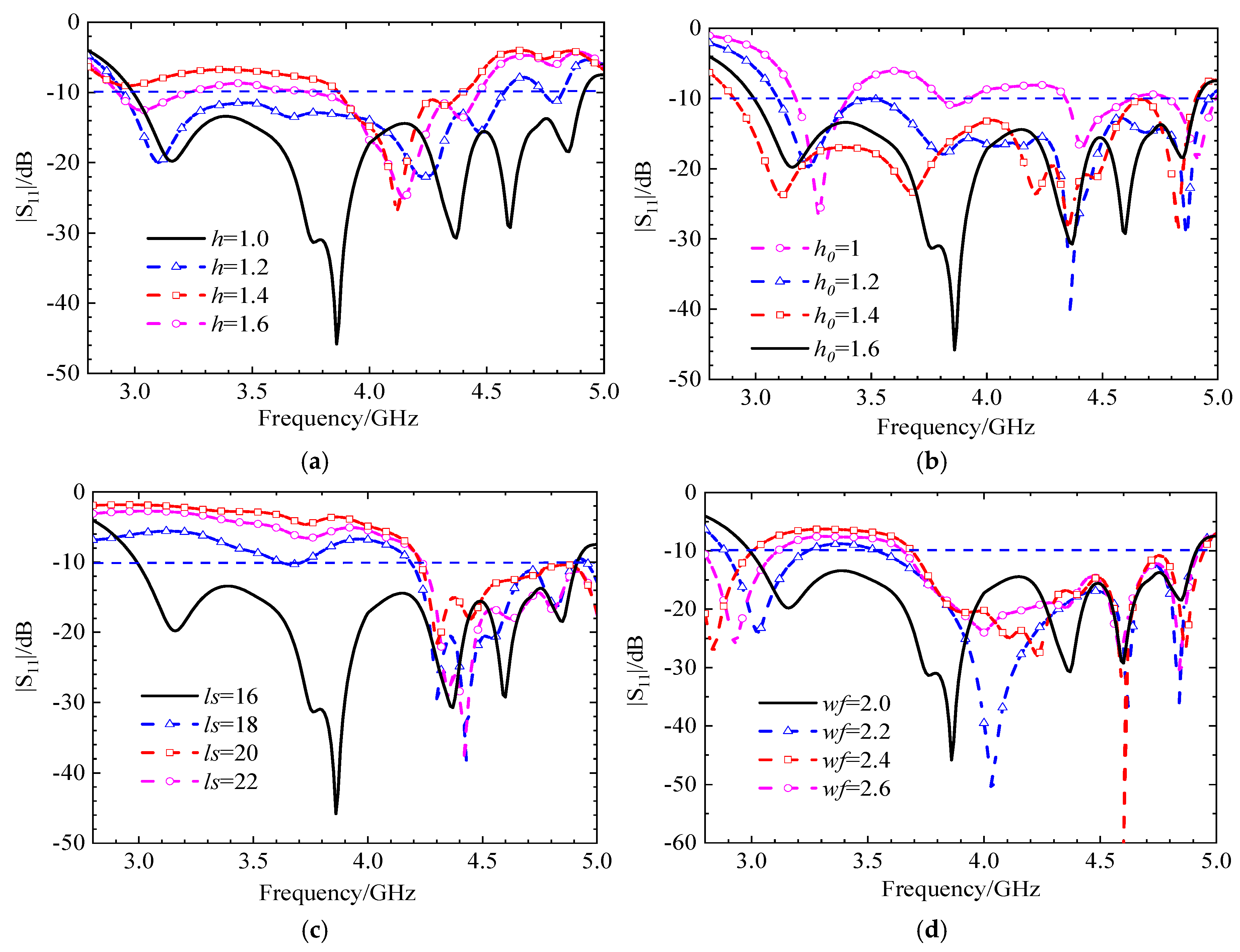

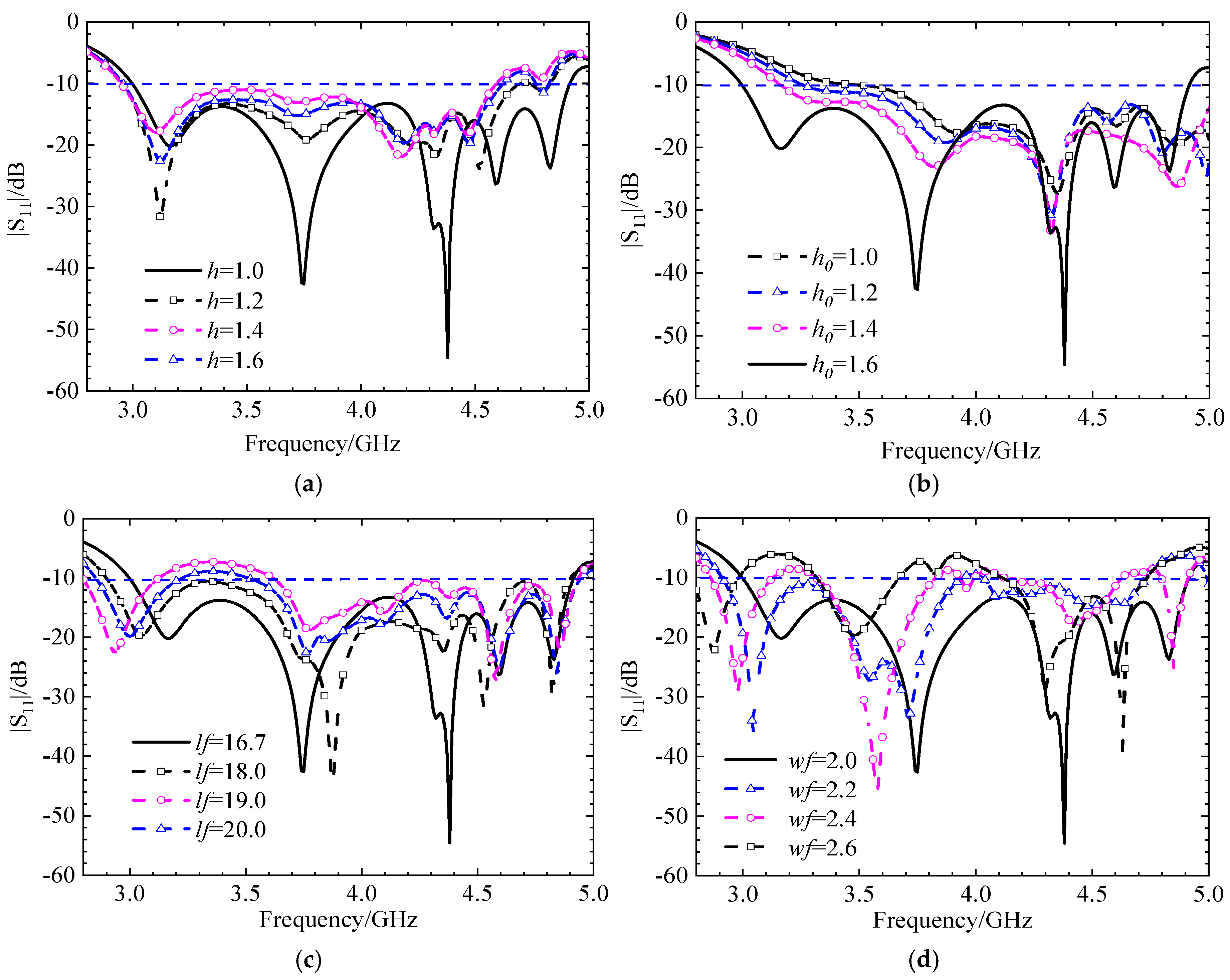

Next, we will check the influence of various antenna structures and parameters on the S-parameters under three polarization states. First, the initial position, i.e., the left-hand circular polarization state, is discussed. The effects of the circular dielectric substrate thickness

h, the square dielectric substrate thickness

h0, the strip patch length

ls, and the slit width

wf on the S-parameters are analyzed, and the simulation results are shown in

Figure 17. When the thicknesses of the two dielectric substrates are altered, the trend of the antenna’s |

S11| simulation results remain essentially unchanged. Only when the thickness changes significantly vary the reflection coefficient of the antenna increase due to impedance mismatch, leading to a substantial reduction in the impedance bandwidth. As the length of the strip patch and the width of the slit increase, the excited modes change, causing the resonant frequency to shift towards higher frequencies and the impedance bandwidth to decrease. The radiation patterns for LHCP and RHCP are shown in

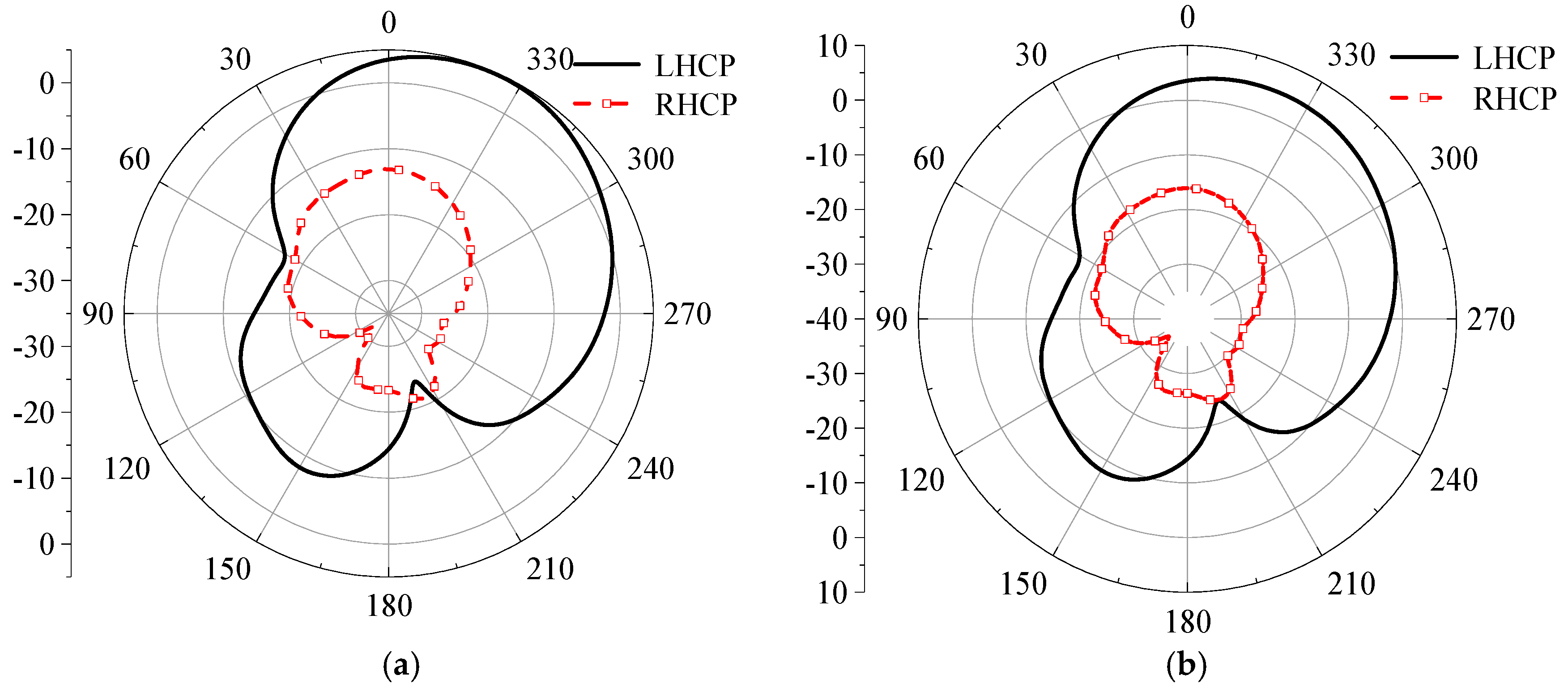

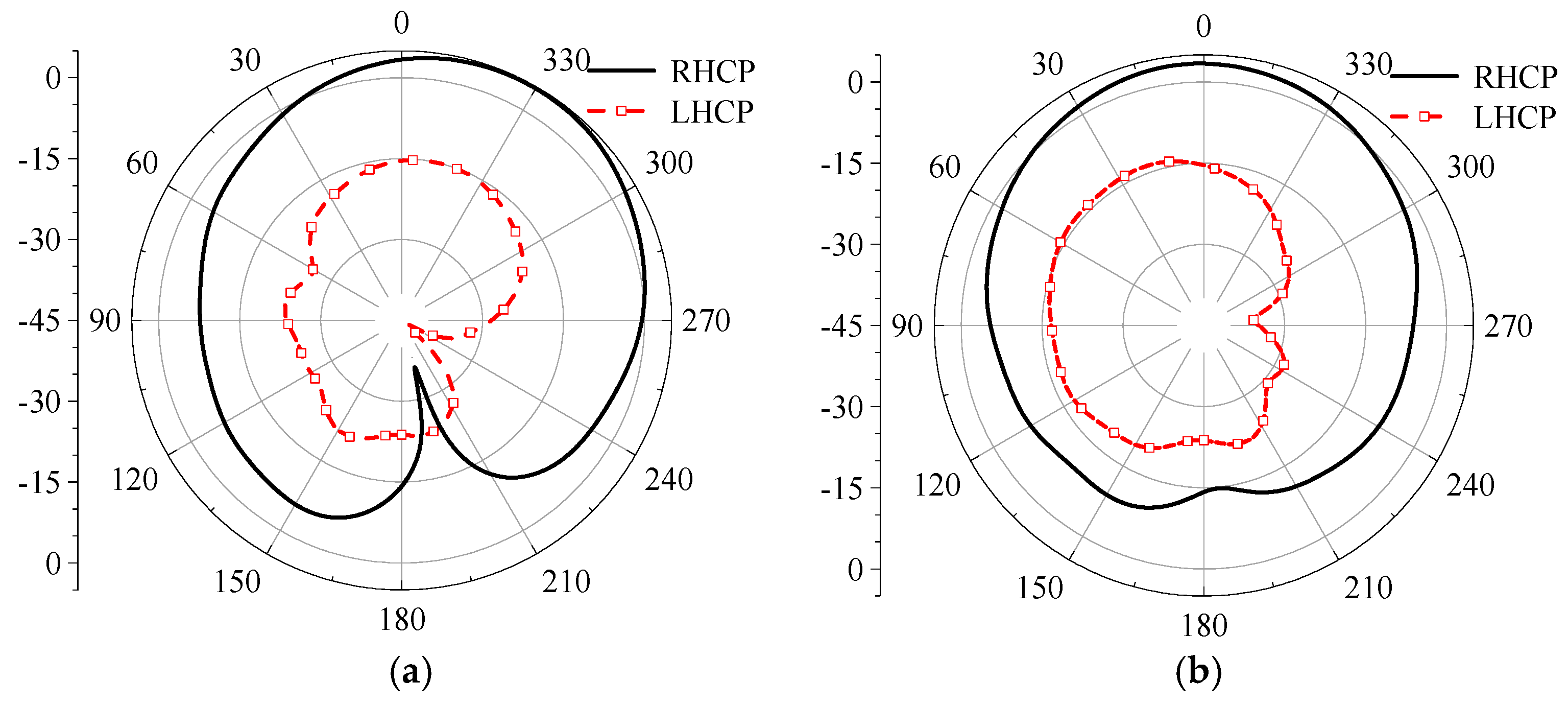

Figure 18. In this case, the LHCP is about 18 dBi higher than the RHCP, indicating that the antenna achieves the characteristics of LHCP.

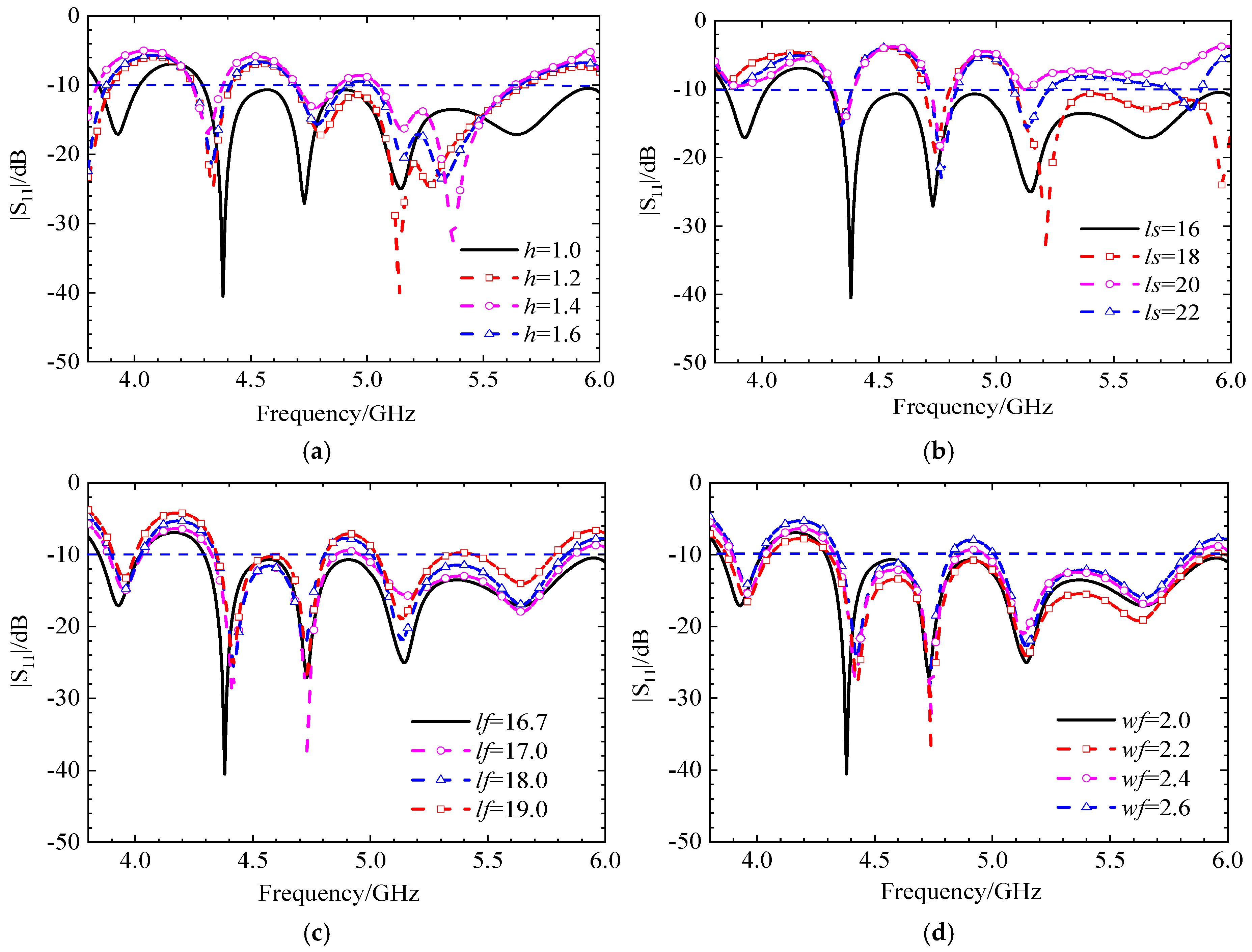

Continuing the discussion on the metasurface rotated at 45° in the linear polarization state, the influence of the numerical values of the circular dielectric substrate thickness

h, the length of the strip patch

ls, the gap length

lf, and the gap width

wf on the S-parameters is analyzed, with simulation results shown in

Figure 19. When the thickness of the circular dielectric substrate changes, the variation in the simulated |S₁₁| of the antenna is minimal, with only certain frequency bands developing stopbands, indicating a degree of stability. When the length of the strip patch increases, the impedance mismatch becomes more severe, preventing the antenna from functioning properly. When the length and width of the gap are altered, the S-parameters of the antenna remain almost unchanged, demonstrating strong stability in the coupling feed structure. The radiation patterns for the co-polarization and cross-polarization are shown in

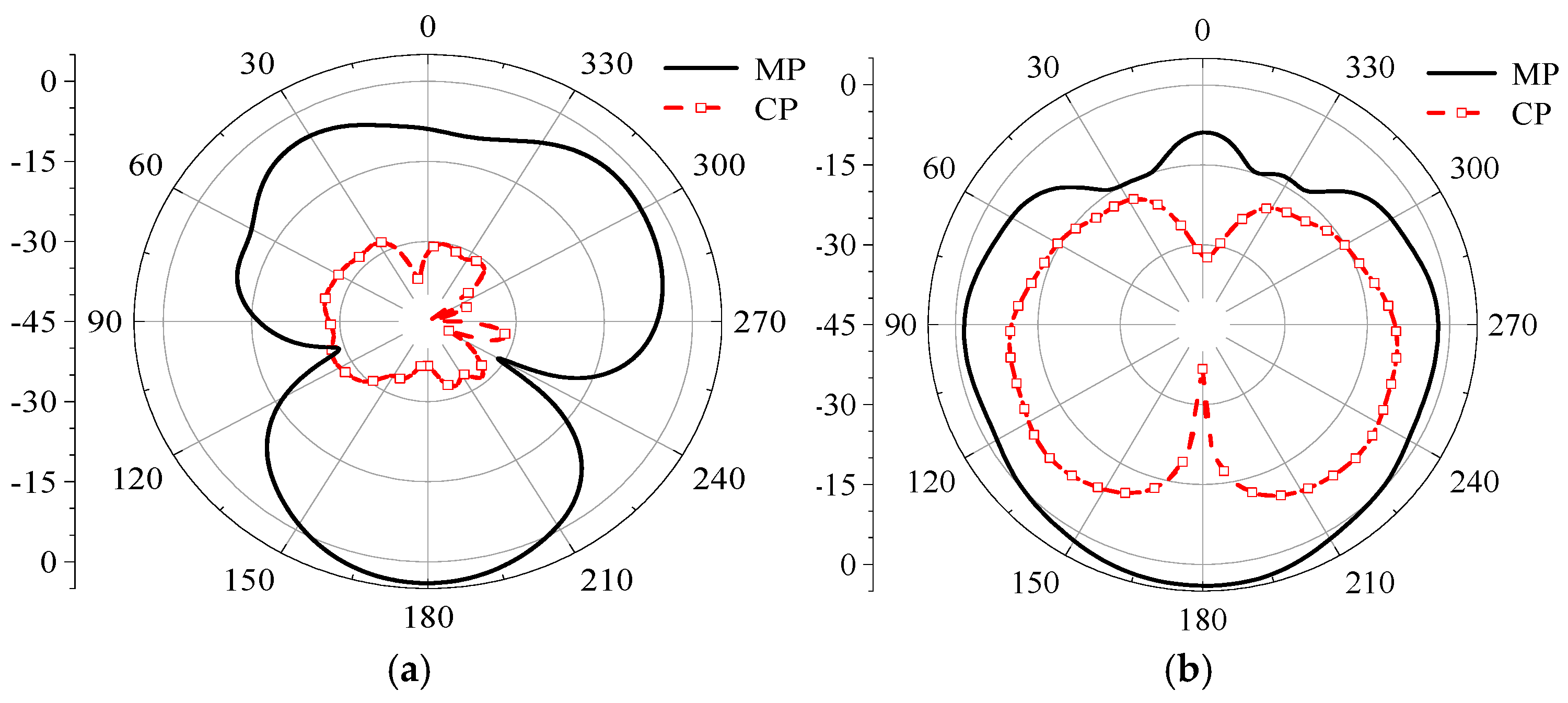

Figure 20. At both phi = 0° and phi = 90°, the co-polarization level is approximately 20 dBi higher than the cross-polarization level, indicating that the antenna exhibits good anti-interference characteristics [

17].

The following analysis delves into the final optimized configuration of the metasurface-based antenna, specifically when it is rotated by 90 degrees to operate in the RHCP state. A detailed parametric study is crucial for understanding how different physical dimensions influence the antenna's performance, particularly its S11.

The study investigates the impact of four key parameters, circular dielectric substrate thickness h, square dielectric patch thickness h0, coupling gap length lf, and coupling gap width wf.

The findings, summarized in

Figure 21, reveal distinct behaviors for each parameter.

When the thicknesses of the dielectric substrates,

h and

h0, are altered, the antenna's impedance bandwidth experiences a slight decrease. However, a key indicator of stability is that the resonant frequency points remain almost unchanged. This suggests that while the range of frequencies over which the antenna is well-matched to the feed line narrows slightly, the fundamental operating frequencies are robust against variations in substrate thickness. This stability is often a desirable characteristic in antenna design, as shown in

Figure 21(a) and (b).

The analysis shows that the length of the gap,

lf , in the coupling structure has only a minor impact on the antenna's overall performance. This implies that the design is not highly sensitive to minor manufacturing tolerances in this specific dimension, as shown in

Figure 21 (c).

In contrast to the gap length, the width of the gap, wf, has a significant and critical influence[

18]. As the gap width increases, a notable phenomenon occurs: the entire operating frequency band shifts towards lower frequencies. Furthermore, undesired stopbands (frequency bands where signal transmission is blocked) begin to appear within the intended operating band. This can severely degrade antenna performance and is a critical consideration during the design and tuning process, as shown in

Figure 21 (d).

The radiation patterns for both Left-Hand Circular Polarization (LHCP) and Right-Hand Circular Polarization (RHCP) are presented in

Figure 22. The results provide clear and compelling evidence for the antenna's polarization state. At two principal planes, phi

= 0° and phi = 90°, the RHCP gain is approximately 21 dBi higher than the LHCP gain in the direction of maximum radiation.

This substantial difference, known as the axial ratio performance in practice, serves as a definitive confirmation that the antenna successfully achieves high-purity Right-Hand Circular Polarization. The 90-degree rotation of the metasurface effectively excites the desired orthogonal modes with a 90-degree phase difference, which is the fundamental principle for generating circular polarization, while significantly suppressing the unwanted LHCP component.

In summary, the parametric study confirms the stable operation of the antenna's core resonance while highlighting the gap width as a critical tuning parameter. The radiation pattern measurements ultimately validate the design's success in achieving excellent RHCP performance. We can conclude the final size of designed antenna as in

Table 1. According these sizes, the antenna can be fabricated then tested. Results will be discussed next section.

Figure 1.

Complex application scenario of the UAV, control signals coexisting with interference (generated by the AI auxiliary method).

Figure 1.

Complex application scenario of the UAV, control signals coexisting with interference (generated by the AI auxiliary method).

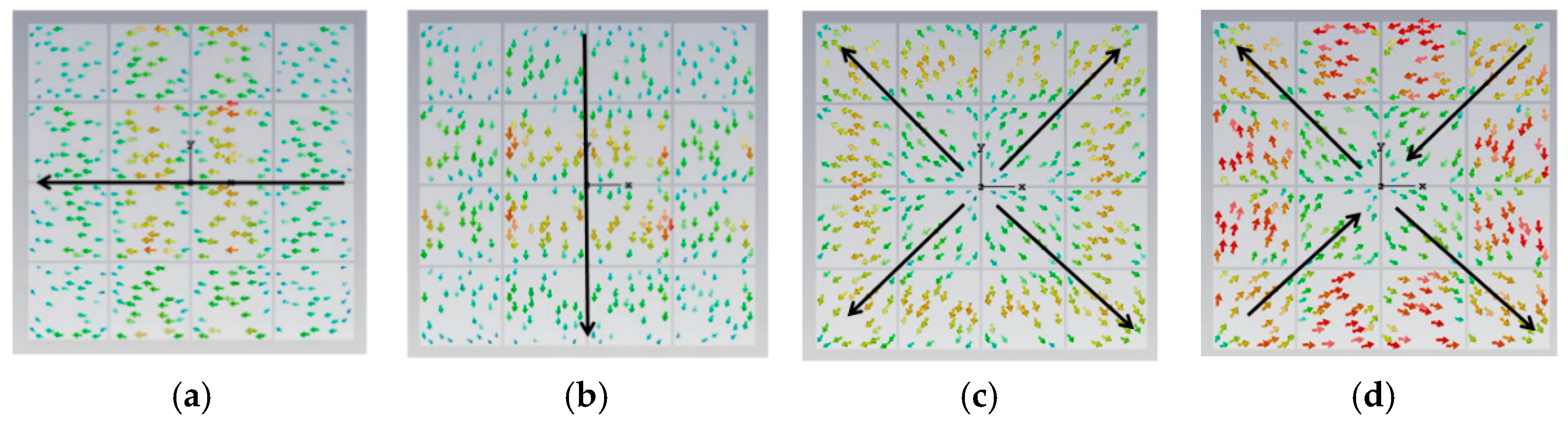

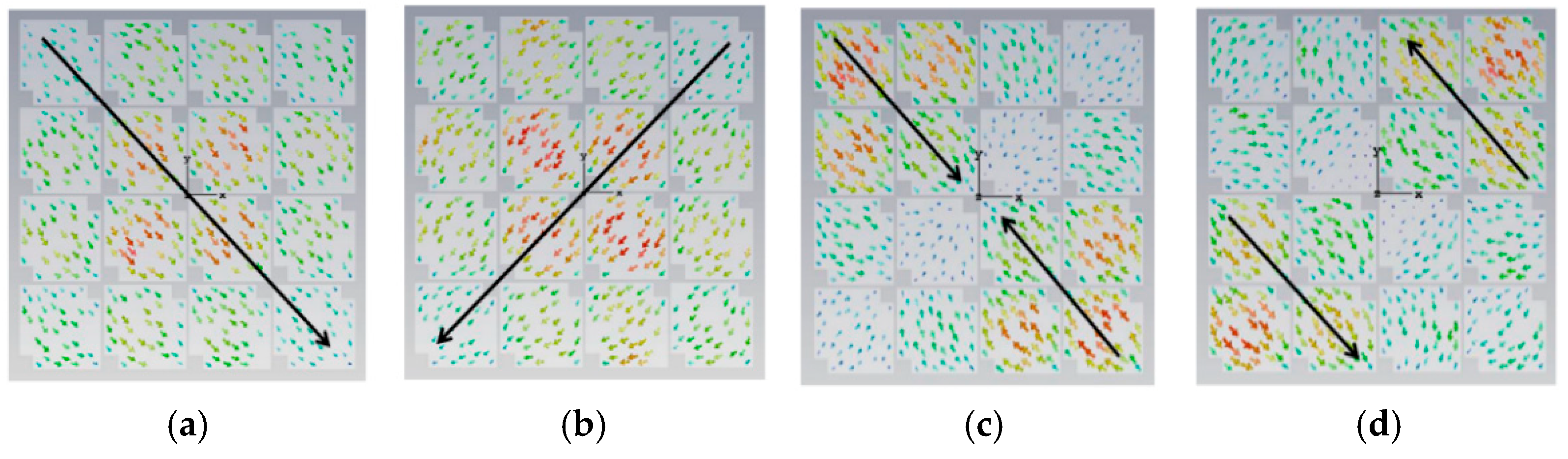

Figure 2.

Surface current distribution of periodic square metasurface for the 4x4 array, indicating in (a) mode 1, (b) mode 2, (c) mode 3, and (d) mode 4, especially, modes 3 and 4 shown orthogonal currents distribution.

Figure 2.

Surface current distribution of periodic square metasurface for the 4x4 array, indicating in (a) mode 1, (b) mode 2, (c) mode 3, and (d) mode 4, especially, modes 3 and 4 shown orthogonal currents distribution.

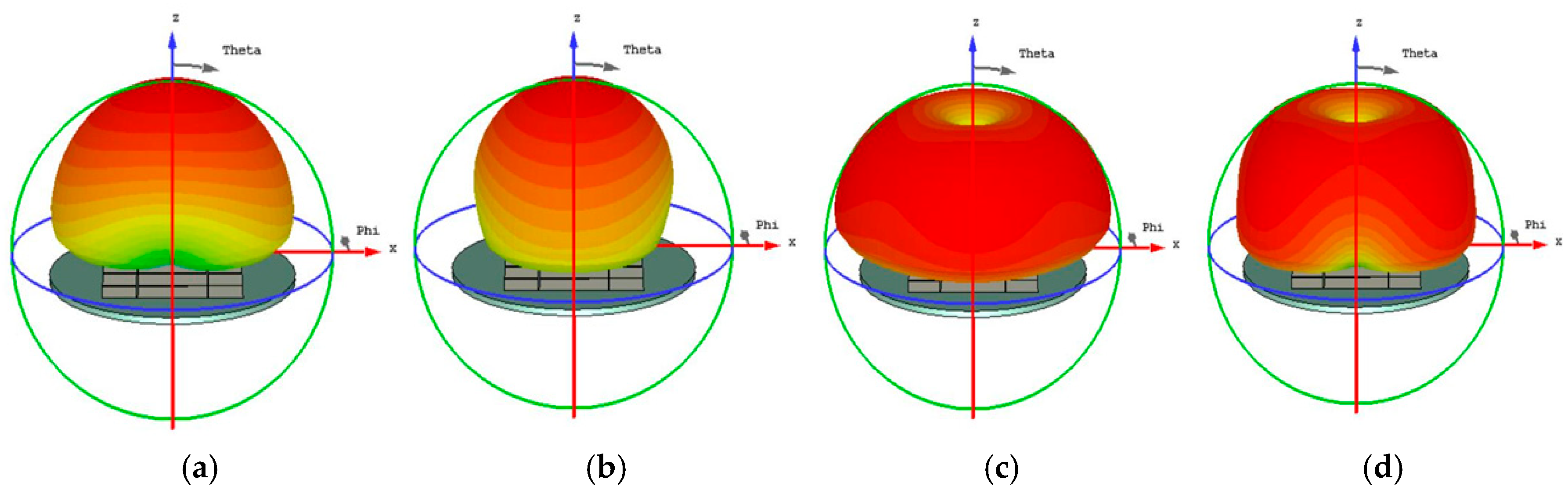

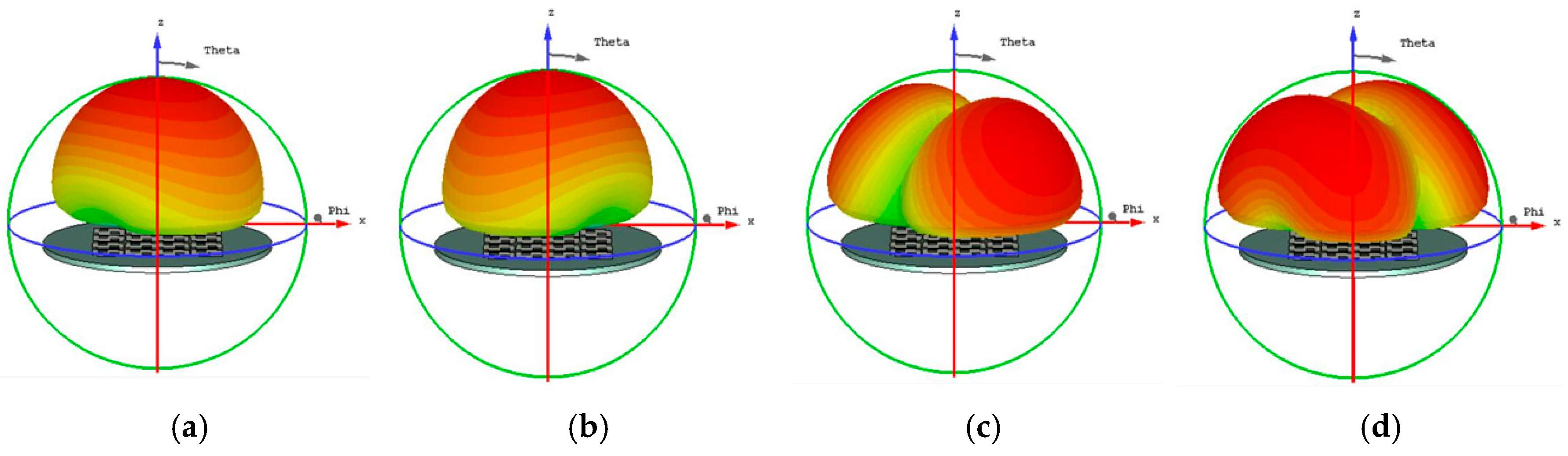

Figure 3.

Radiation pattern of a square unit metasurface for the 4x4 array, (a) mode 1, (b) mode 2, (c) mode 3, and (d) mode 4, modes 1 and 2 shown almost the same pattern, as well as modes 3 and 4.

Figure 3.

Radiation pattern of a square unit metasurface for the 4x4 array, (a) mode 1, (b) mode 2, (c) mode 3, and (d) mode 4, modes 1 and 2 shown almost the same pattern, as well as modes 3 and 4.

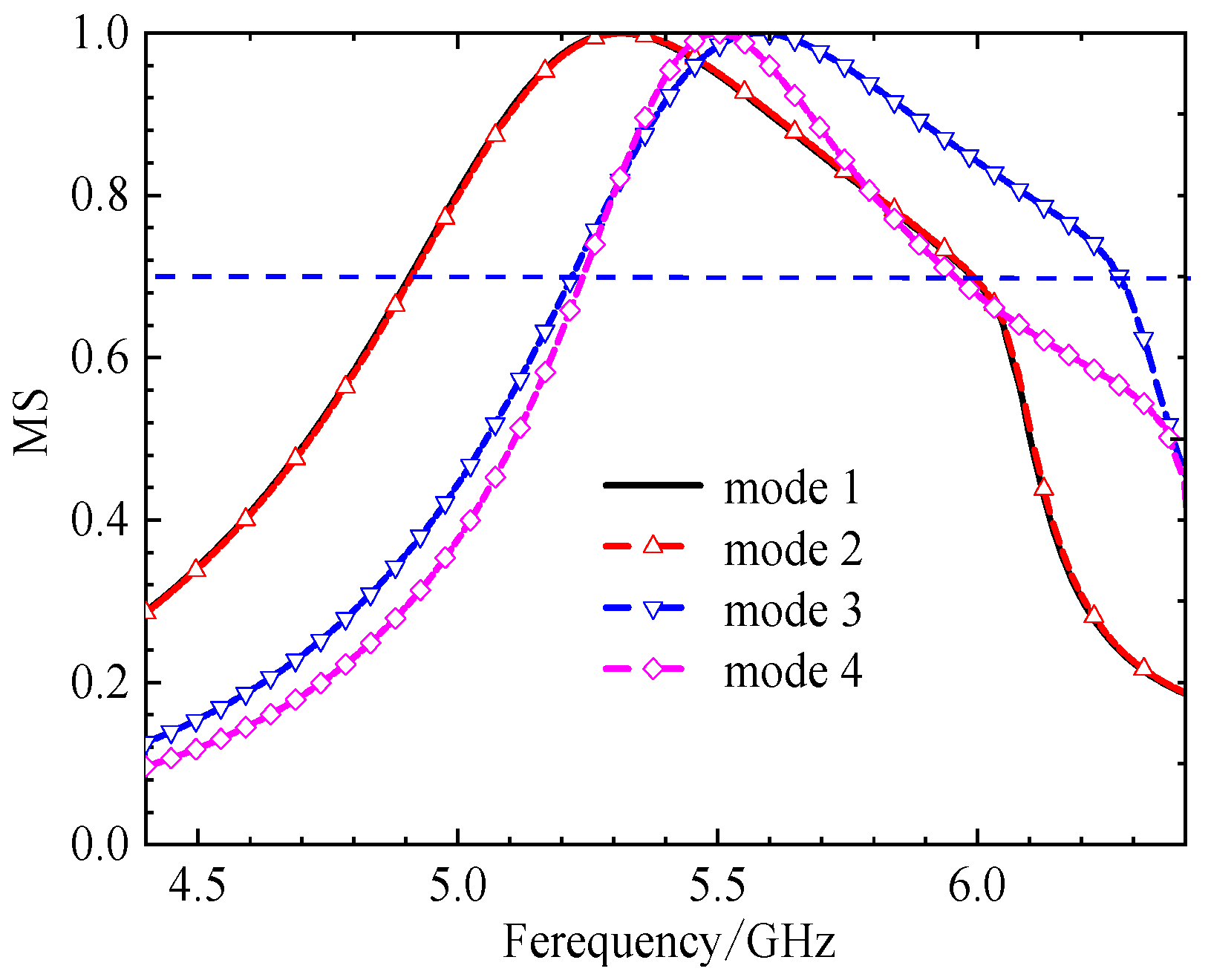

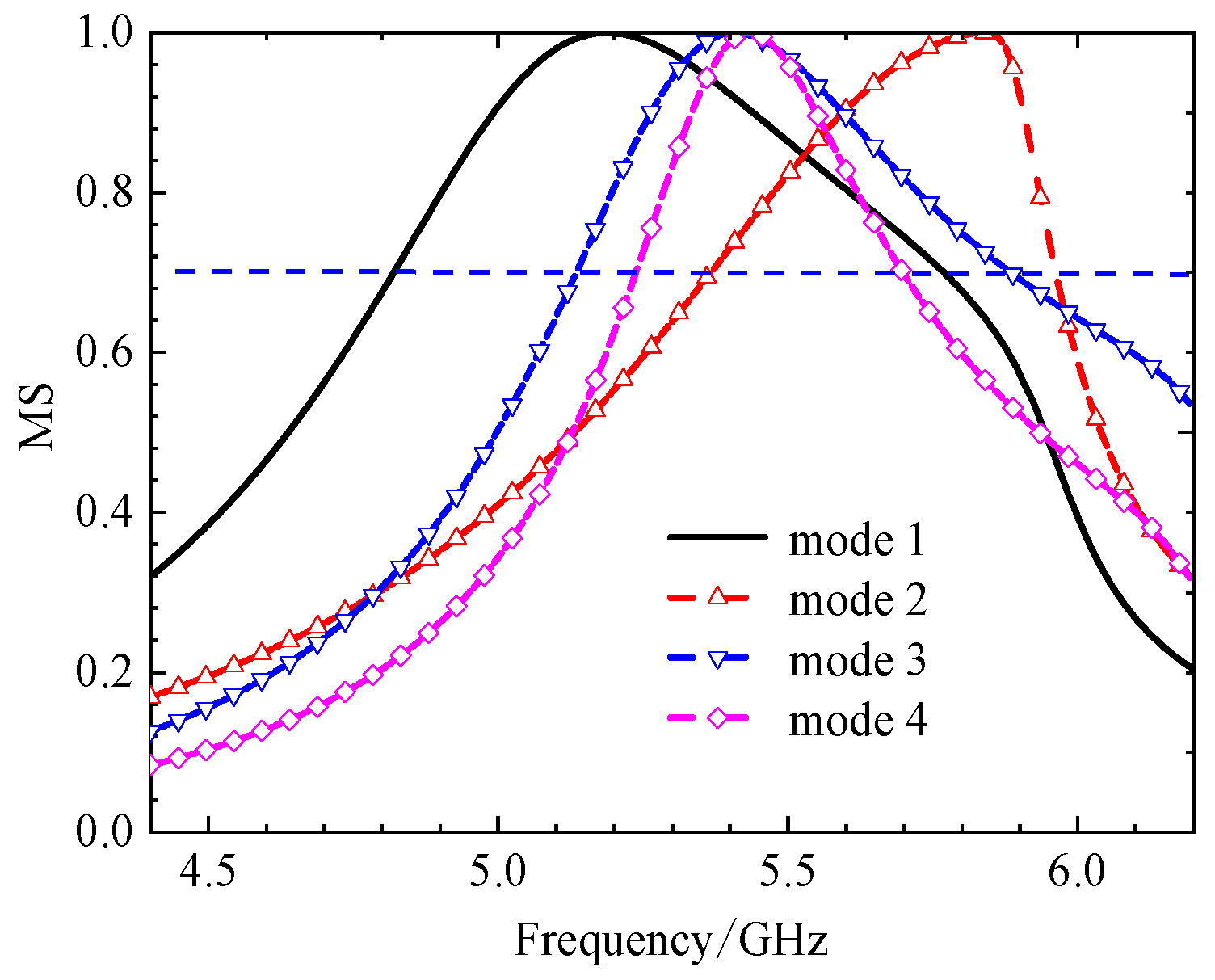

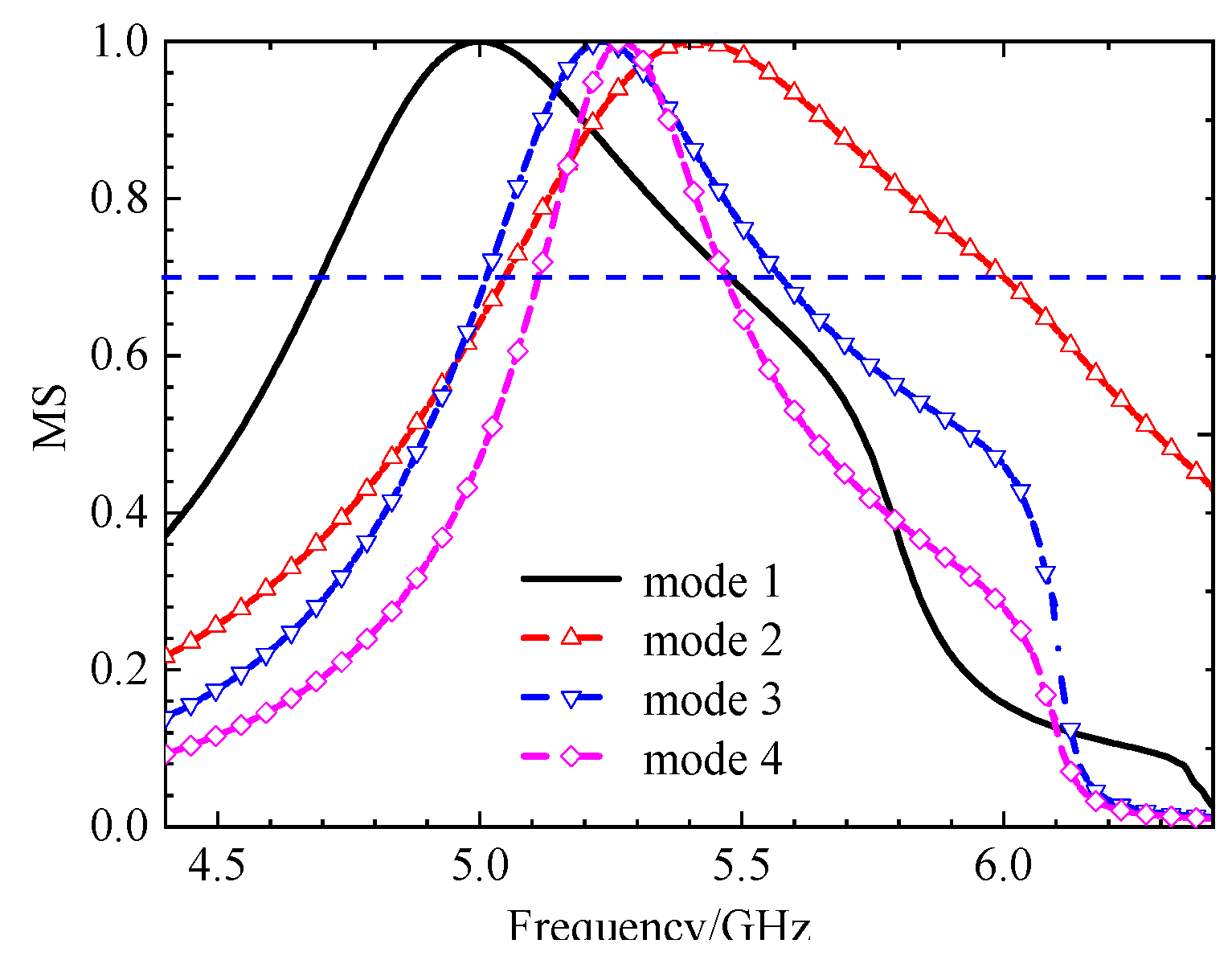

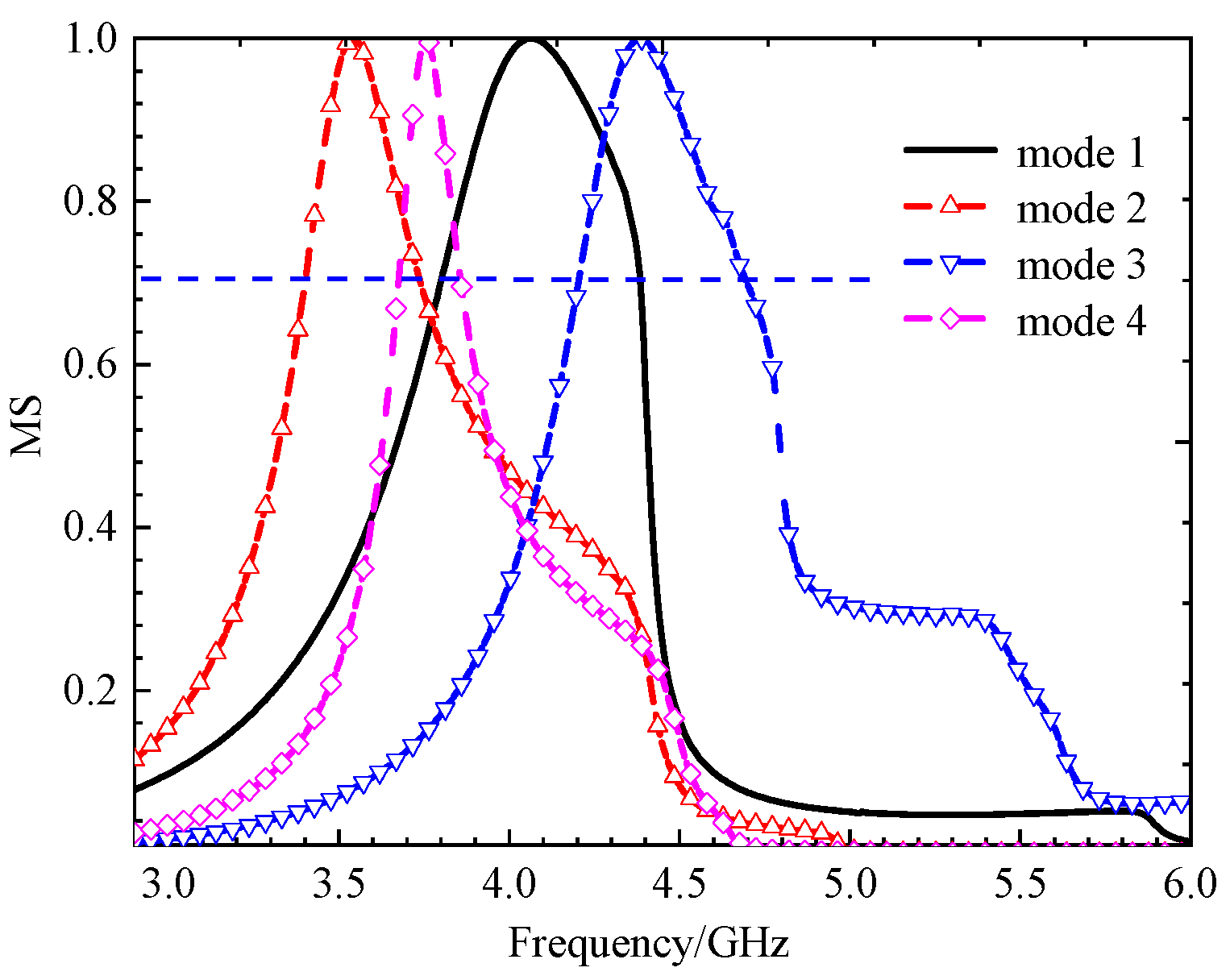

Figure 4.

The MS of 4x4 square unit metasurface, modes 1 and 2 shown almost the same MS distribution, modes 3 and 4 different, the MS peaks narrow.

Figure 4.

The MS of 4x4 square unit metasurface, modes 1 and 2 shown almost the same MS distribution, modes 3 and 4 different, the MS peaks narrow.

Figure 5.

Current distribution on the 4x4 metasurface while each square unit cut off a pair of opposite corners, in cases of (a) mode 1, (b) mode 2, (c) mode 3, and (d) mode 4.

Figure 5.

Current distribution on the 4x4 metasurface while each square unit cut off a pair of opposite corners, in cases of (a) mode 1, (b) mode 2, (c) mode 3, and (d) mode 4.

Figure 6.

Radiation pattern of 4x4 metasurface while each square unit cut off a pair of opposite corners, (a) mode 1, (b) mode 2, (c) mode 3, and (d) mode 4.

Figure 6.

Radiation pattern of 4x4 metasurface while each square unit cut off a pair of opposite corners, (a) mode 1, (b) mode 2, (c) mode 3, and (d) mode 4.

Figure 7.

The MS of 4x4 unit metasurface while each square unit cut off a pair of opposite corners, peaks moved to lower frequency.

Figure 7.

The MS of 4x4 unit metasurface while each square unit cut off a pair of opposite corners, peaks moved to lower frequency.

Figure 8.

Surface current distribution of each unit with two hollows (small squares), (a) mode 1, (b) mode 2, (c) mode 3, (d) mode 4.

Figure 8.

Surface current distribution of each unit with two hollows (small squares), (a) mode 1, (b) mode 2, (c) mode 3, (d) mode 4.

Figure 9.

Radiation pattern of each unit with two hollow (small squares), (a) mode 1, (b) mode 2, (c) mode 3, (d) mode 4.

Figure 9.

Radiation pattern of each unit with two hollow (small squares), (a) mode 1, (b) mode 2, (c) mode 3, (d) mode 4.

Figure 10.

The MS of each unit with two hollow small squares, peak frequency moved to lower, but too closely spaced for modes 3 and 4.

Figure 10.

The MS of each unit with two hollow small squares, peak frequency moved to lower, but too closely spaced for modes 3 and 4.

Figure 11.

Surface current distribution of small square with three hollows, (a) mode 1, (b) mode 2, (c) mode 3, and (d) mode 4.

Figure 11.

Surface current distribution of small square with three hollows, (a) mode 1, (b) mode 2, (c) mode 3, and (d) mode 4.

Figure 12.

Radiation pattern of 4x4 metasurfaces, each square unit with three hollow small squares, (a) mode 1, (b) mode 2, (c) mode 3, and (d) mode 4.

Figure 12.

Radiation pattern of 4x4 metasurfaces, each square unit with three hollow small squares, (a) mode 1, (b) mode 2, (c) mode 3, and (d) mode 4.

Figure 13.

The MS of 4x4 metasurfaces, each unit with three hollow small squares, the peak frequency with space enough.

Figure 13.

The MS of 4x4 metasurfaces, each unit with three hollow small squares, the peak frequency with space enough.

Figure 14.

Principle diagram of achieving polarization reconfigurable metasurface, (a) initial Position, (b) rotate 45°, and (c) rotate 90°.

Figure 14.

Principle diagram of achieving polarization reconfigurable metasurface, (a) initial Position, (b) rotate 45°, and (c) rotate 90°.

Figure 15.

Characteristic angle (CA) of metasurfaces with three hollow small squares.

Figure 15.

Characteristic angle (CA) of metasurfaces with three hollow small squares.

Figure 16.

Final designed Antenna Structure, metasurfaces with three hollow small squares, (a) top and side view, (b) bottom view (feed & ground).

Figure 16.

Final designed Antenna Structure, metasurfaces with three hollow small squares, (a) top and side view, (b) bottom view (feed & ground).

Figure 17.

Simulation results of |S11| for different thicknesses of circular dielectric substrates h, square dielectric substrates h0, strip patch length ls and gap width wf, (a)parameters h, (b) parameters h0, (c) parameters ls, and (d) parameters wf.

Figure 17.

Simulation results of |S11| for different thicknesses of circular dielectric substrates h, square dielectric substrates h0, strip patch length ls and gap width wf, (a)parameters h, (b) parameters h0, (c) parameters ls, and (d) parameters wf.

Figure 18.

Simulation diagram of LHCP and LHCP, (a) phi=0°, (b) phi=90°.

Figure 18.

Simulation diagram of LHCP and LHCP, (a) phi=0°, (b) phi=90°.

Figure 19.

Simulation results of |S11| for different thicknesses of circular dielectric substrates h, strip patch length ls, gap length lf and gap width wf, (a)parameters h, (b) parameters ls, (c) parameters lf, and (d) parameters wf.

Figure 19.

Simulation results of |S11| for different thicknesses of circular dielectric substrates h, strip patch length ls, gap length lf and gap width wf, (a)parameters h, (b) parameters ls, (c) parameters lf, and (d) parameters wf.

Figure 20.

Simulation diagram of main-polarization (MP) and cross-polarization (CP), (a) phi=0°, (b) phi=90°.

Figure 20.

Simulation diagram of main-polarization (MP) and cross-polarization (CP), (a) phi=0°, (b) phi=90°.

Figure 21.

Simulation results of |S11| for different thicknesses of circular dielectric substrates h, square dielectric substrates h0, gap length lf and gap width wf, (a) parameters h, (b) parameters h0, (c) parameters lf, and (d) parameters wf.

Figure 21.

Simulation results of |S11| for different thicknesses of circular dielectric substrates h, square dielectric substrates h0, gap length lf and gap width wf, (a) parameters h, (b) parameters h0, (c) parameters lf, and (d) parameters wf.

Figure 22.

Simulation diagram of LHCP and RHCP, (a) phi=0°, (b) phi=90°.

Figure 22.

Simulation diagram of LHCP and RHCP, (a) phi=0°, (b) phi=90°.

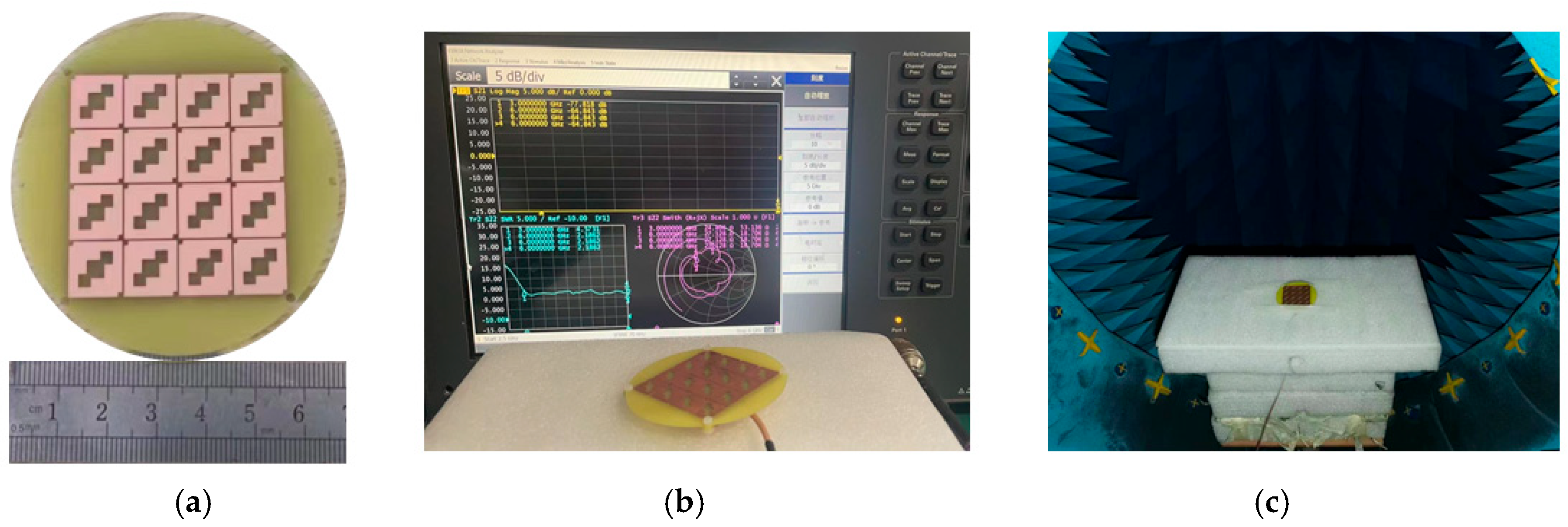

Figure 23.

Physical and test images of antennas, (a) physical image of antenna, (b) test diagram of antenna connection to vector network, and (c) test diagram of line in microwave anechoic chamber.

Figure 23.

Physical and test images of antennas, (a) physical image of antenna, (b) test diagram of antenna connection to vector network, and (c) test diagram of line in microwave anechoic chamber.

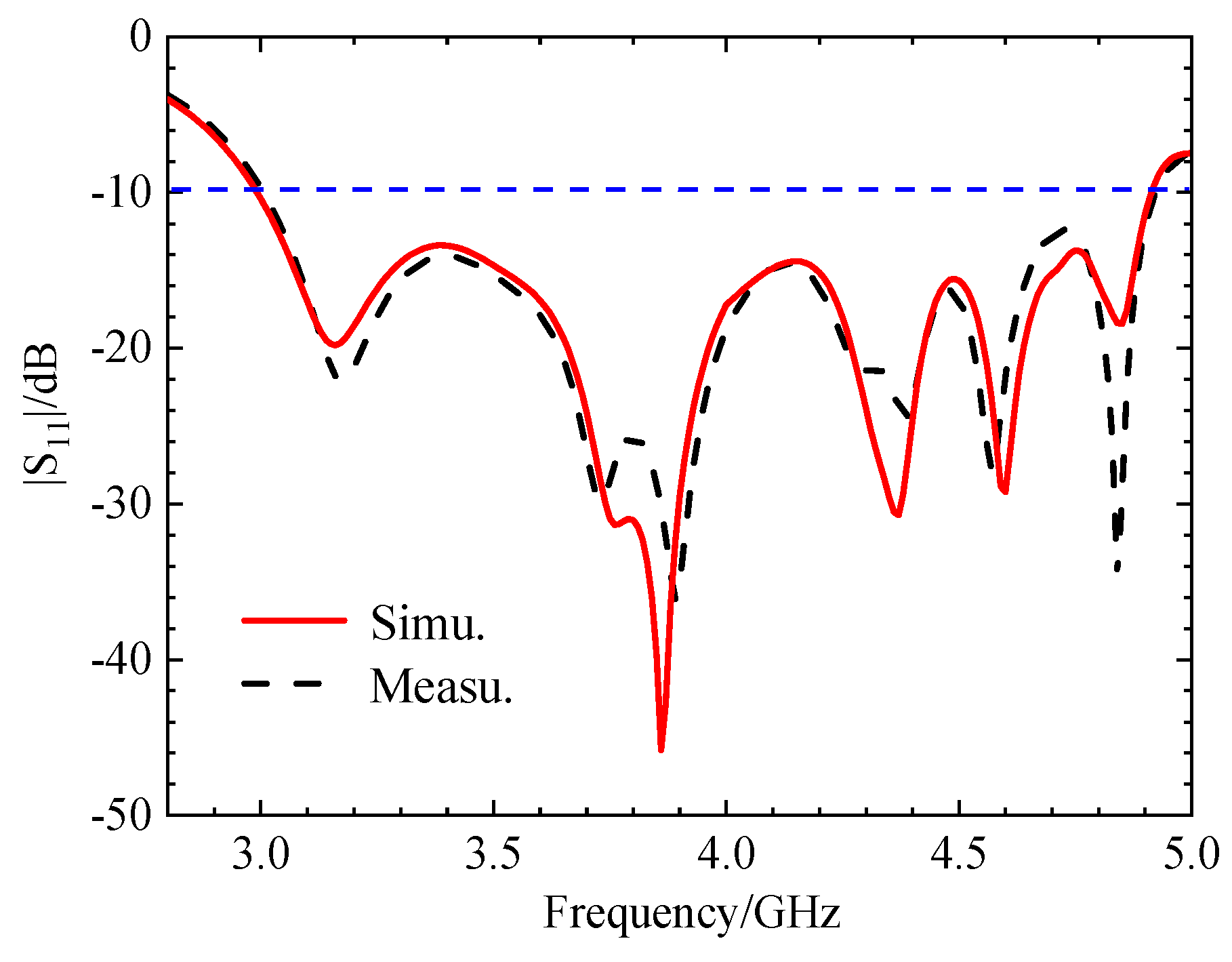

Figure 24.

Comparison between simulation (Simu.) and measurement (Measu.) of |S11| antenna at initial position.

Figure 24.

Comparison between simulation (Simu.) and measurement (Measu.) of |S11| antenna at initial position.

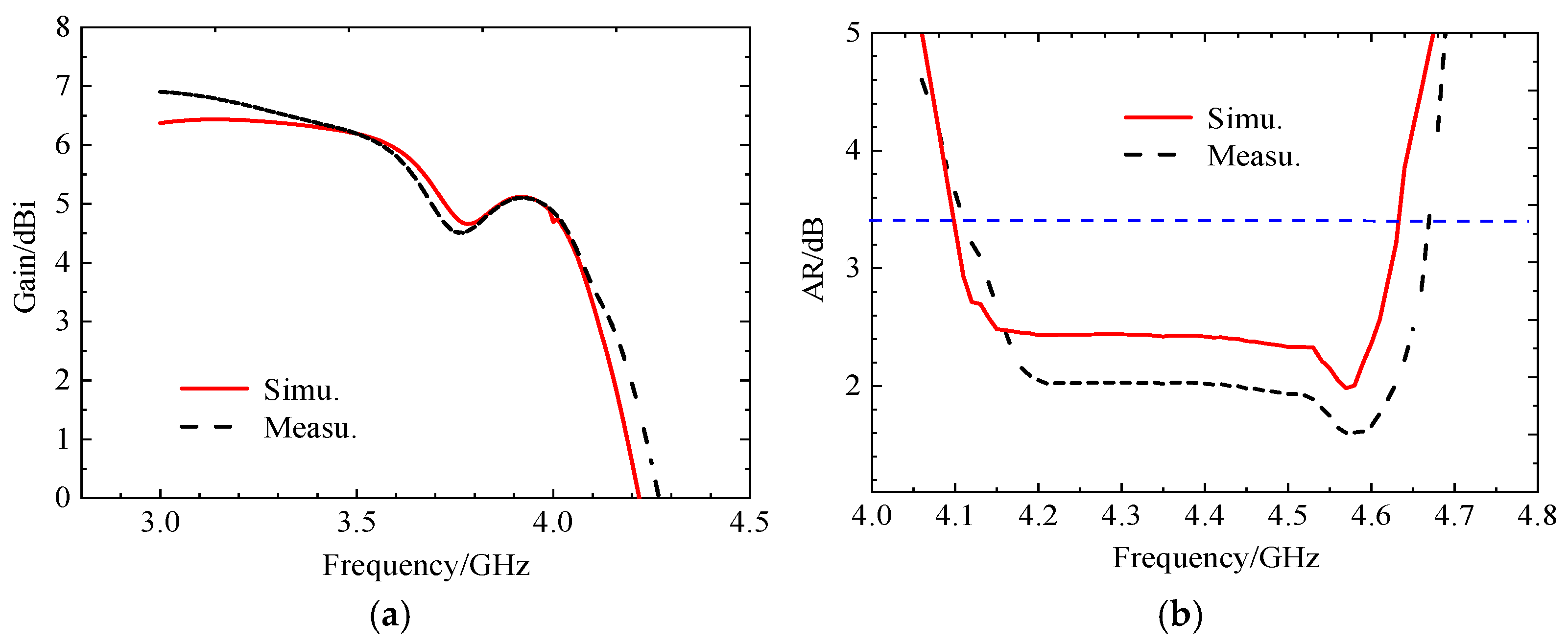

Figure 25.

Comparison between simulation and testing of gain and axial bandwidth at initial position, (a) gain chart, (b) axis ratio (AR) bandwidth graph.

Figure 25.

Comparison between simulation and testing of gain and axial bandwidth at initial position, (a) gain chart, (b) axis ratio (AR) bandwidth graph.

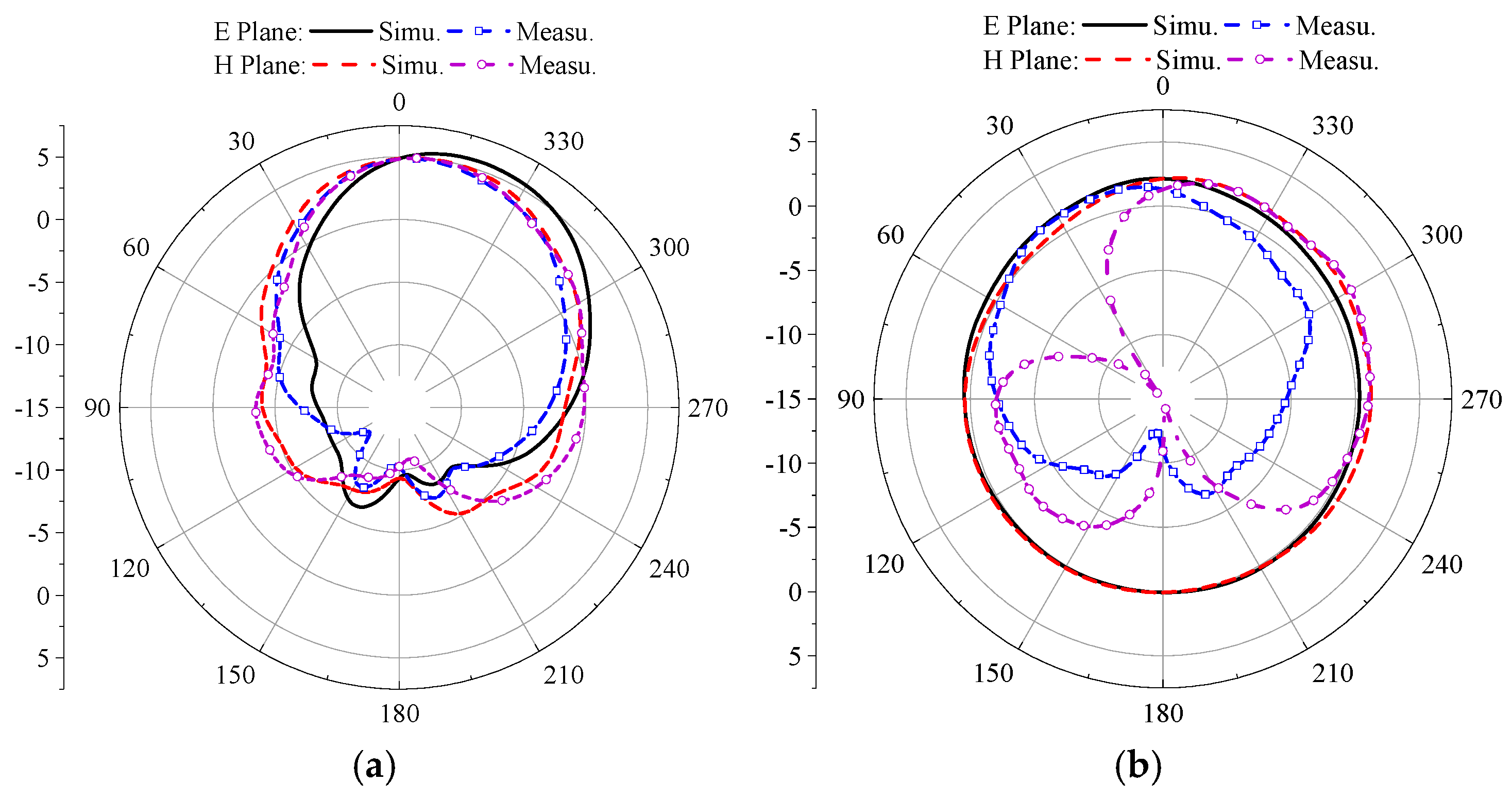

Figure 26.

Simulation and measurement of radiation pattern, antenna at initial position, (a) 3.85 GHz, (b) 4.37 GHz.

Figure 26.

Simulation and measurement of radiation pattern, antenna at initial position, (a) 3.85 GHz, (b) 4.37 GHz.

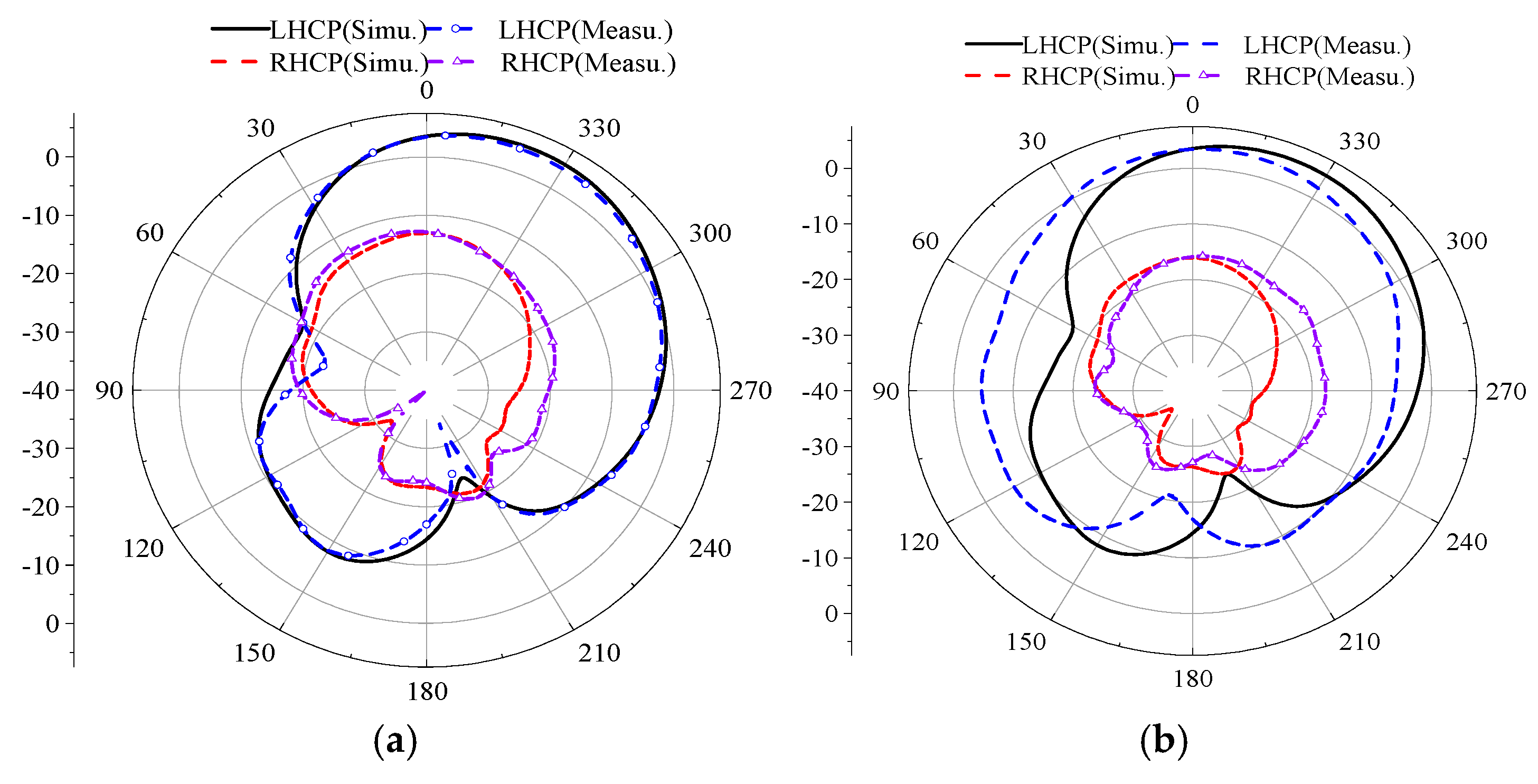

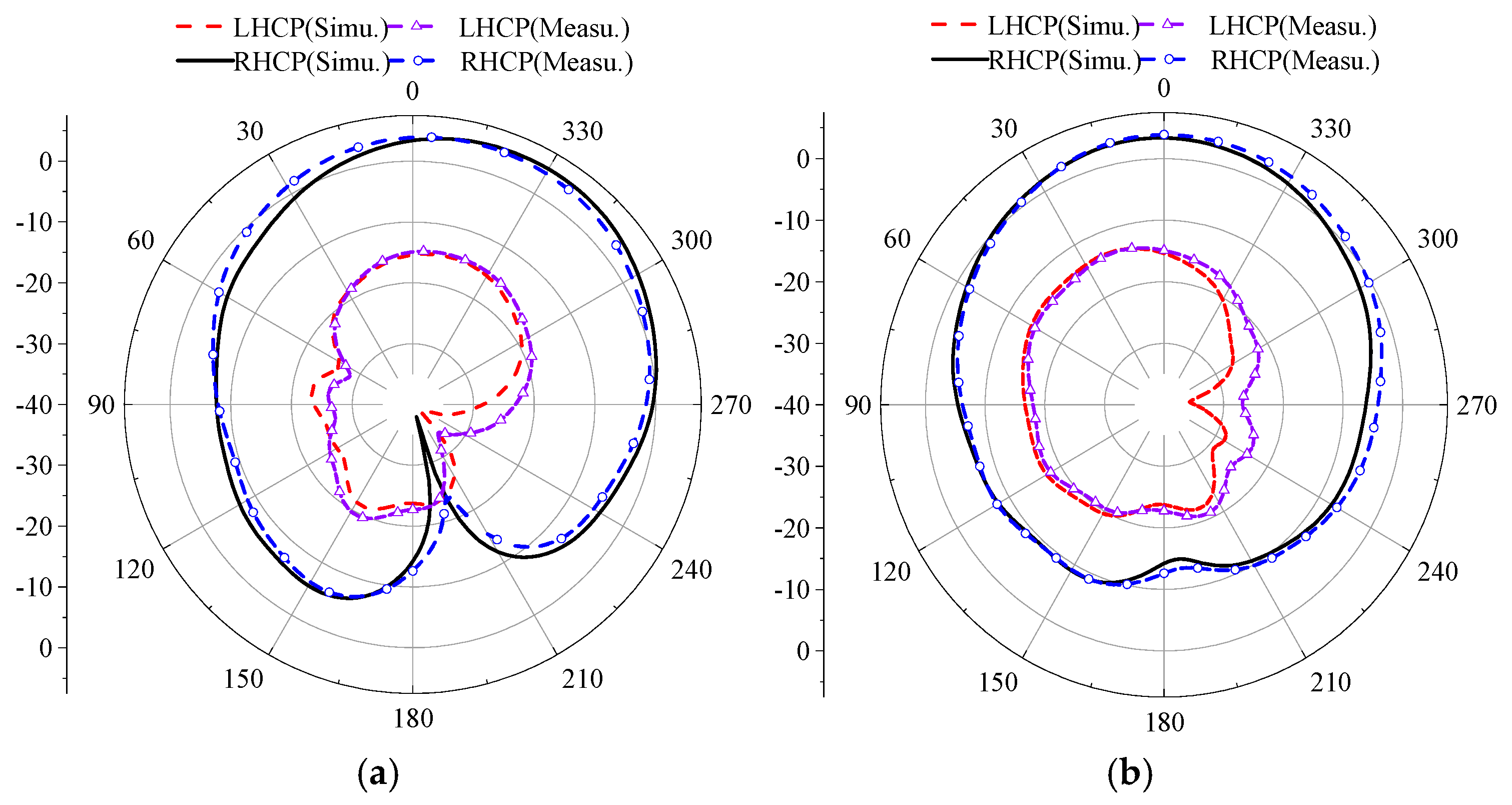

Figure 27.

Simulation and measurement of the LHCP and RHCP at initial position, (a) phi = 0°, (b) phi = 90°.

Figure 27.

Simulation and measurement of the LHCP and RHCP at initial position, (a) phi = 0°, (b) phi = 90°.

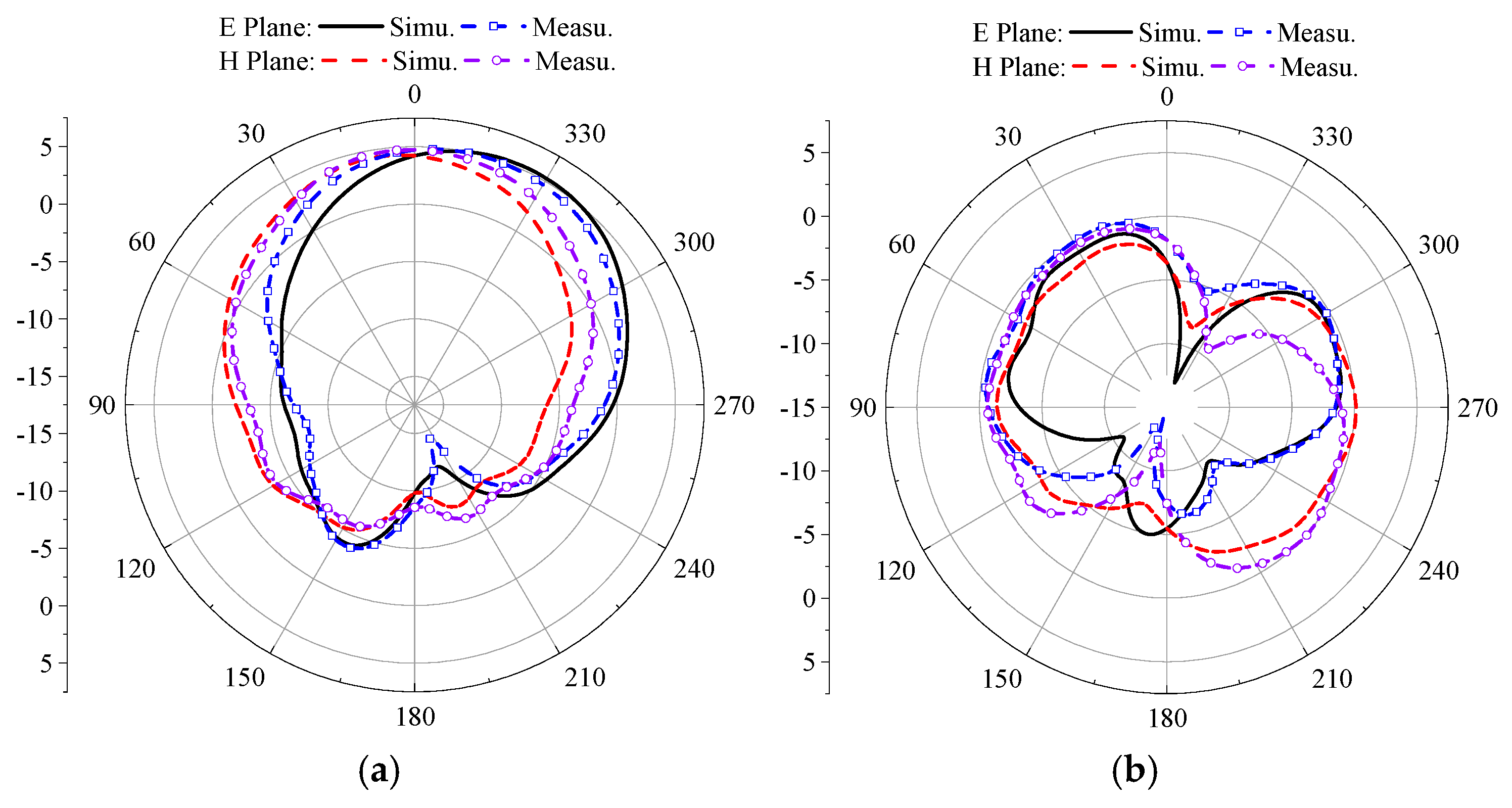

Figure 28.

Simulation and measurement of antenna radiation patterns when rotating 90°, (a) 3.85 GHz, (b) 4.37 GHz.

Figure 28.

Simulation and measurement of antenna radiation patterns when rotating 90°, (a) 3.85 GHz, (b) 4.37 GHz.

Figure 29.

Simulation and test comparison of left-handed circular polarization and right-handed circular polarization at 90 ° rotation (a) phi = 0°, (b) phi = 90° E plane.

Figure 29.

Simulation and test comparison of left-handed circular polarization and right-handed circular polarization at 90 ° rotation (a) phi = 0°, (b) phi = 90° E plane.

Table 1.

Final Size of Designed Antenna.

Table 1.

Final Size of Designed Antenna.

| Dimension |

w0 |

w1 |

w2 |

w3 |

wr |

wf |

|

Size (mm) |

11 |

3.68 |

2.5 |

2.5 |

35 |

2 |

| Dimension |

L |

lf |

ls |

h0 |

h |

s |

|

Size (mm) |

50 |

16.7 |

16 |

1.6 |

1 |

1 |

Table 2.

Summary of Antenna Performance.

Table 2.

Summary of Antenna Performance.

| Polarization State |

Parameter |

Simulation |

Measurement |

|

LHCP (0°) |

Impedance BW |

48.17% (3.01–4.92 GHz) |

47.0% (3.05–4.89 GHz) |

| 3-dB AR BW |

9.75% (4.12–4.64 GHz) |

10.3% (4.15–4.60 GHz) |

| Avg. Gain |

5.9 dBi |

5.7 dBi |

|

LP (45°) |

Impedance BW |

32.68% (4.30–5.98 GHz) |

29.9% (4.33–5.85 GHz) |

| XPD (Co/Cross-pol) |

>23 dB |

>23 dB |

| Avg. Gain |

5.3 dBi |

5.1 dBi |

|

RHCP (90°) |

Impedance BW |

48.29% (3.00–4.91 GHz) |

48.5% (2.98–4.88 GHz) |

| 3-dB AR BW |

9.98% (3.46–3.82 GHz) |

10.1% (3.42–3.78 GHz) |

| Avg. Gain |

6.1 dBi |

6.0 dBi |