Introduction

After the era of globalization, digitalisation of the financial sector has become imperative (Garg et al., 2025). Especially in the payment landscape, global economies are undergoing significant changes (Priyadarshini & Kar, 2021; Barontini & Holden, 2019) towards evolutionary progress of the currency (fiat) from paper money to its digital representations (BIS, 2020). With the emergence of cryptocurrencies, Central Banks around the world have shown keen interest in introducing the currency in its digital form, calling it ‘Central Bank Digital Currency’ (CBDC). Globally, many advanced and emerging economies, such as Sweden (e-krona), China (e-CNY), the Bahamas (Sand Dollar), Nigeria (eNaira), and the Eastern Caribbean (Dcash), have piloted digital currencies. Atlantic council1 has set up a ‘CBDC tracker’ and has found that nearly 98% of global gross domestic product (GDP) is exploring the possibility of CBDC. This clearly shows the growing importance of CBDC in the digital world.

In India, an Inter-ministerial committee (2019) examined the implications of digital currency and in 2022 Reserve Bank of India (RBI) introduced its first digital currency in the name e-Rupee (e₹) as part of a controlled pilot phase in both retail and wholesale segments. This initiative seeks to complement the success of existing payment systems like Unified Payments Interface (UPI). Introduction of e₹ is aimed to enhance financial inclusion by reducing transaction cost, and promoting transparency in the monetary transaction (RBI, 2023). Unlike cryptocurrencies, e₹ is introduced as a centralised, sovereign-backed liability of the RBI, ensuring both trust and stability in digital transactions (RBI, 2023; Sankar, 2021; Bhaskar et al., 2022).

Despite plausible benefits and the rapid growth of the digital economy, the behavioural acceptance of e₹ remains a critical challenge. Evidence from other countries highlight that technological readiness and policy push alone do not guarantee user adoption (Garg et al., 2025; Xu et al., 2022; Zhoa et al., 2023). For instance, China’s e-CNY pilot demonstrated high wallet creation rates but low active usage among individuals due to perceived convenience of existing payment apps and limited user incentives (Cheng, 2022). Similarly, Nigeria’s eNaira and the Bahamas’ Sand Dollar faced public skepticism, low awareness, and infrastructural limitations that hindered mainstream adoption (Ozili & Alonso, 2024). These international experiences underscore that the success of CBDCs depends less on technology and more on user perception, trust, and behavioural intention. In the Indian context, even though the population is increasingly tech-savvy, adoption decisions are still influenced by perceptions of usefulness, ease of use, security, and institutional trust. Further, the pre-existing payment landscape may create payment inertia (Aggarwal et al., 2023). Further, since CBDC aim at financial inclusion, one of the key determinants is degree of awareness among the public. The low digital literacy and knowledge about CBDC can hinder the adoption. Therefore, to understand the E-Rupee’s adoption trajectory, it is essential to explore how individuals perceive and evaluate this new digital currency in comparison with existing payment instruments.

Theoretical Framework and Review

Economic incentives, institutional trust and personal perception of value have always been key factors in influencing adoption of new financial technology (Sandhu et al. 2023; Nayak & Kumar, 2025). Adoption of any new technology and its implications are well discussed in the literature with various theoretical models like UTAUT (Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology), DOI (Diffusion of innovation theory). All these frameworks add their own unique explanatory value, but they vary in their scope and breadth of behavioral explanation. In this section, we will explore the applicability of these models for the present study.

DOI model (Roger,1962) explains the process of technology adoption by the perceived characteristics of the technology like relative advantage, compatibility and complexity. DOI has become a popular theoretical model in explaining the adoption of innovation like mobile banking and blockchain technology (Xu et al., 2022). However, one of the major drawbacks of this model is that it looks at the macro-level adoption rather than the individual perceptions. DOI therefore does not describe the nuanced psychological aspects that may affect the uptake of a central bank digital currency by individual users. UTAUT model, on the other hand, is more comprehensive theory than DOI model, which considers social influence and performance expectancy (Rahi et al., 2018). Though this model is quite successful in exploring the user behaviour, due to its complexity its adoption becomes challenging for empirical studies especially for emerging economies like India (Aggarwal et al., 2023).

Contrary to this, the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) that was proposed by Davis (1989) is the most parsimonious and empirically supported model of technology adoption. It assumes that there are two fundamental perceptions of perceived usefulness (PU) and the perceived ease of use (PEOU), which dictate the attitude and behavioral intentions of users towards adopting a technology. With time, TAM extensions have included constructs like trust, perceived risk, and self-efficacy, particularly in the study of financial technology (Raza & Tursoy, 2024; Putri et al., 2023; Kelly & Palaniappan, 2023). This simplicity and strength of the model is particularly applicable to understanding e₹ adoption where the behavioral choice is determined by the perceptions of convenience and institutional reliability instead of peer influence or infrastructural support.

Although TAM has been demonstrated to be effective in various sectors, namely e-banking, mobile wallets, and fintech platforms, no current empirical literature has implemented TAM in understanding the adoption of e₹, forming a significant research gap. The implementation of TAM to the e₹ adoption thus brings both conceptual and methodological novelty. It not only places the research into an established framework of behavioral research, but also adjusts it to the specific socio-technical conditions of digital economy in India. The confidence in the issuing authority (RBI) and data security are the key determinants in estimating the adoption of digitally issued currency by a state (RBI, 2023). Apart from behavioural aspects, education mainly digital literacy is assumed to have an influence on the perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness of digital payment tools (Adel, 2024). These constructs, when combined add value to the explanation of e₹ adoption behavior.

The Nudge Theory (Thaler & Sunstein, 2009) on the other hand, has been used to describe the impact of small nudges on the behavior of finances, like the default choice or the presence of incentives, which may shape behavior without coercion (Ozili and Alonso, 2024). Even a study by Koonprasert et al. (2024) explained how awareness would prepare for CBDC adoption. To form these information nudges into a real situation, stated preference method is used. Following these studies, the present study adopted information nudge to elicit the willingness to shift to e₹. Since no monetary benefits or sacrifice is involved, this method stands unique to the classic stated preference theory or bounded rationality theory.

Empirical Review

Past studies on digital currencies majorly concentrated on macroeconomic effects and policy evaluations (Ozili & Alonso, 2024; Bains et al., 2023; Auer et al., 2021; Bijlsma et al., 2021; Fadli et al., 2023; BIS, 2020a; Dong et al., 2024; Elsayed & Nasir, 2022; Bhaskar et al., 2022; Xu., 2022). Schilling et al. (2020) is the first study to examine the effect of CBDC on efficiency and financial stability. Similar arguments are provided by Luu et al. (2023), Fernandez-Villaverde et al. (2021) Ahnert et al. (2023). Though there are studies which have examined the user adoption and perceptions towards CBDC in other countries (Xu et al., 2022; Barkhordari et al., 2017; Ghosh et al., 2023; Fadli et al., 2023; Qu et al., 2022; Tronnier & Kakkar., 2022), their payment ecosystem is quite different from India. The user adoption of digital currency, given the pre-existing complex ecosystem of digital payments, becomes quite challenging. For instance, studies like Cheng (2022) and Xu et al. (2022) examined the adoption of e-CNY in China. Given the existing payment apps like Alipay and Wechat pay, the study found even though there is an increase in the number of wallets being created, the number of users of the wallets remained low. The study explained that this resistance is due to established habits, comfort of interoperability and network effects. Even a study by Kumar & Prasad (2024) explained that people are prone to pay inertia where they would choose familiar, trusted systems over newer and different ones unless they observe relative benefits. Hence, understanding the influence of perceived ease of use or convenience of CBDC adoption becomes important.

One of the interesting studies by Rahi et al. (2018) on Bahamas’ adoption of Sand Dollar found that, even though the country pioneered in deploying large-scale CBDC, its adoption especially in rural areas was low due to lack of awareness and trust in digital systems. Ozili and Alonso (2024) on the other hand, examined the adoption in Nigerian eNaira. The study found that there are behavioral elements like trust and perceived credibility have significant impact on its adoption. In case of digital euro, Tronnier and Kakkar (2022) analyzed that privacy concerns and trust affect the willingness to adopt CBDC.

The studies exploring the adoption of CBDC in India is still in its infancy stage. However, literature on its concept, feasibility and challenges are widely discussed. RBI (2023) in its concept note, has described the benefits of CBDC including efficiency, transparency and inclusion. Banerjee & Sinha (2023) highlight the potentiality of CBDC to boost financial inclusion in the country and the implication of CBDC has been explored by Chawla (2023). In a recent study by Prajapati & Kumar (2025) highlighted the challenges of CBDC operation in a given complex ecosystem of UPI, ULI (Unified Lending Interface). Kumari (2024) and Shekar & Ramesh (2025) also described the implications, difficulties, prospects of CBDC in India.

Studies on adoption of CBDC especially in retail sector is very meagre. Some studies like Di Maggio et al. (2024) discussed about CBDC adoption, it focused more on effect of CBDC on bank deposits and the impact of UPI tax on CBDC adoption, rather than the behavioral aspect of user adoption. Even theoretical debates have been made on technological architecture, financial considerations, or comparison of CBDCs to other nations (Bains et al., 2023) excluding the adoption determinants. A study by Dixit et al. (2025) integrated interpretive structural modelling and UTAUT3 framework to understand the acceptance of CBDC. The study highlighted that perceived ease of use, infrastructure and user intent are the key drivers of acceptance of CBDC. In a similar line, Sandhu et al. (2023) found that trust, ease of use are the strong predictors of acceptance of CBDC in India. In a recent study by Nayak & Kumar (2025) emphasized that usage pattern of CBDC among bank employee depend on the awareness of CBDC. However, these studies have restrained themselves to examine the perceptions of users by conducting primary survey.

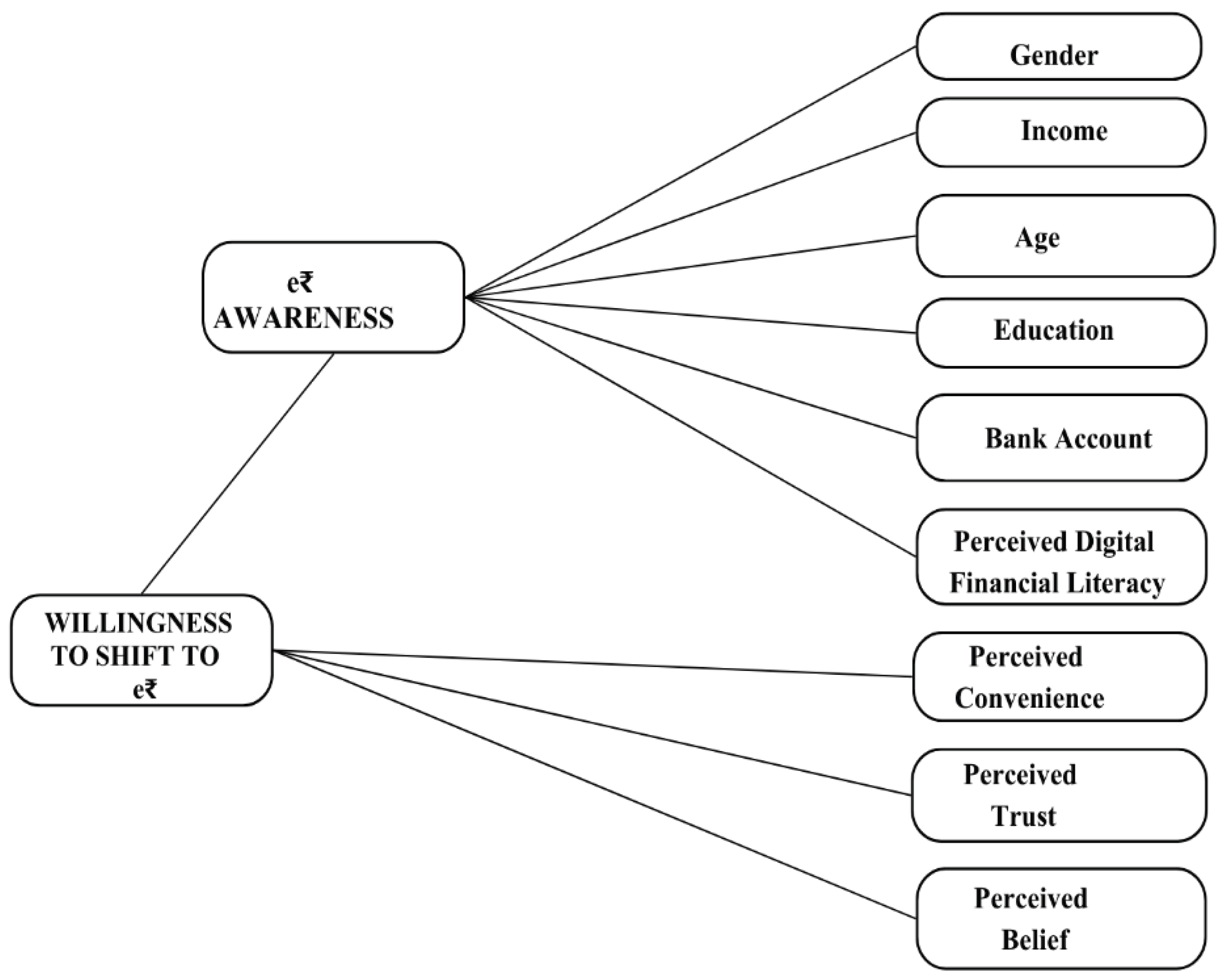

With this theoretical & empirical review, the present study formulated two models to understand the awareness of e₹ and also willingness to shift to e₹ among the public.

Figure 1 provides the conceptual framework for both the model. Given the theoretical and empirical literature, the study explores the behavioral resistance using TAM that expressly model the way perceptions are converted into behavioral intention.

Research Gaps & Objectives

The empirical literature reveals three major gaps. First, the majority of CBDC research is macro and descriptive in nature. Second, some behavioral studies are based on generalized constructs like UTAUT or DOI without experimenting with the perceptual constructs of TAM. Finally, there is no systematic quantitative study on the e₹ though it gained increasing policy significance and have plausible impact at global scale. This research paper fills these gaps by using primary data with two main objectives. The first objective deals with the factors influencing e₹ awareness among the public and the second objective provides the factors which influence the willingness to shift to e₹ given the present payment mechanisms. To attain these objectives, the study forms the following hypothesis:

Model 1: H0: the predictor variables do not affect the e₹ awareness.

H1: At least one predictor significant affect the e₹ awareness.

Model 2: H0= the predictor variables do not affect the willingness to shift (WTS) to e₹

H1=At least one predictor significantly affects the willingness to shift to e₹

Study Area and Research Methodology

The dataset for the study is obtained from the primary survey in one of the major metropolitan cities of India. Being the ‘Silicon Valley’ of the country, city leads in the technological adoption (Scaler, 2025). The city also topped in adoption of cryptocurrency among major metro cities in the country. Hence, Bengaluru marks as an ideal city to conduct primary survey, given its demographic, technological and academic characteristics.

A total of 780 responses is collected and out of which 751 responses are considered after eliminating the non-responses. The study adopted a simple random sampling method due to large population. Before moving for the main survey, the study conducted a pilot study to validate the questionnaire. The questionnaire is structured into three sections. Section A gathered socioeconomic information of respondents, including their demographic characteristics such as age, gender, education, income level, and occupation to have a contextual understanding of the respondents’ background and their potential influence on digital financial behaviour. Section B focused on understanding the participants’ access to formal financial services and their patterns of digital financial engagement. This section collected information on frequency of online transactions, use of mobile wallets, digital payment habits, and the extent of dependence on technology-enabled financial systems. Lastly, Section C had details of respondents’ awareness, perceptions, and usage behaviour concerning India’s Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC). This section provided the information nudge to the respondents regarding the e₹ operation and the willingness to shift to e₹ is elicited. Even the reasons for their preferences are also collected by the study. The data descriptions are provided in the next section.

Data Description

Among the total sample of 751, the gender distribution follows around 51.4% of female and 48.6% of male respondents. The age distribution of the sample is categorized into four groups. Age1 has the respondents below 25 years who constitute nearly 38.5% of the total sample, whereas age2 comprises of 26-45 years group with 44.4%, age3 has 12.6% belonging to 46-60 years and around 4.5% are above 60 years in age4. With respect to educational qualification, about 30.5% of respondents completed 12th grade, 43% are graduates, 23.7% had post-graduate degrees and only 2.8% had education above the post-graduate level.

Regarding banking access, 97% of respondents having a bank account showing a high level of financial inclusion. When classified by monthly income, over half of the respondents (53.5%) are in the income category of less than ₹25,000, while 22% are in the income range between ₹25,000 and ₹50,000. Respondents with income ₹50,000–₹1 lakh formed 16.5% of the sample, and those above ₹1 lakh represented 8%.

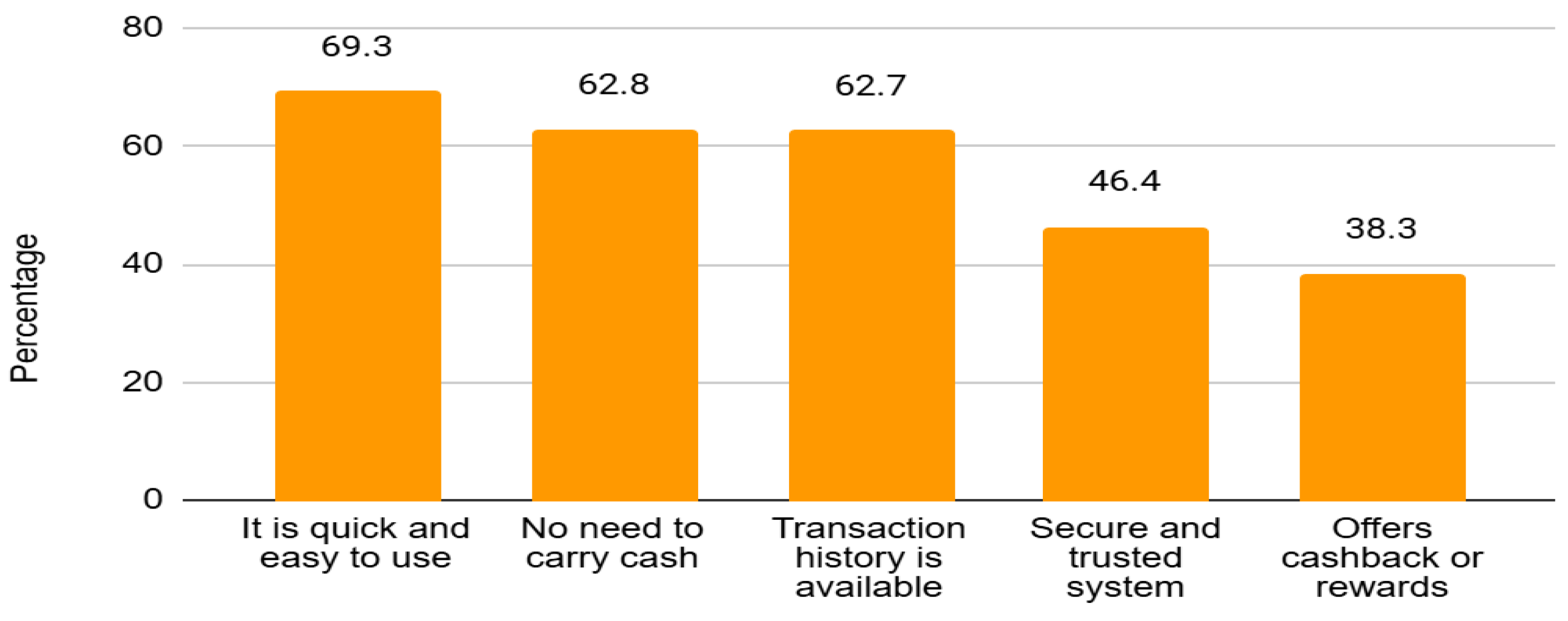

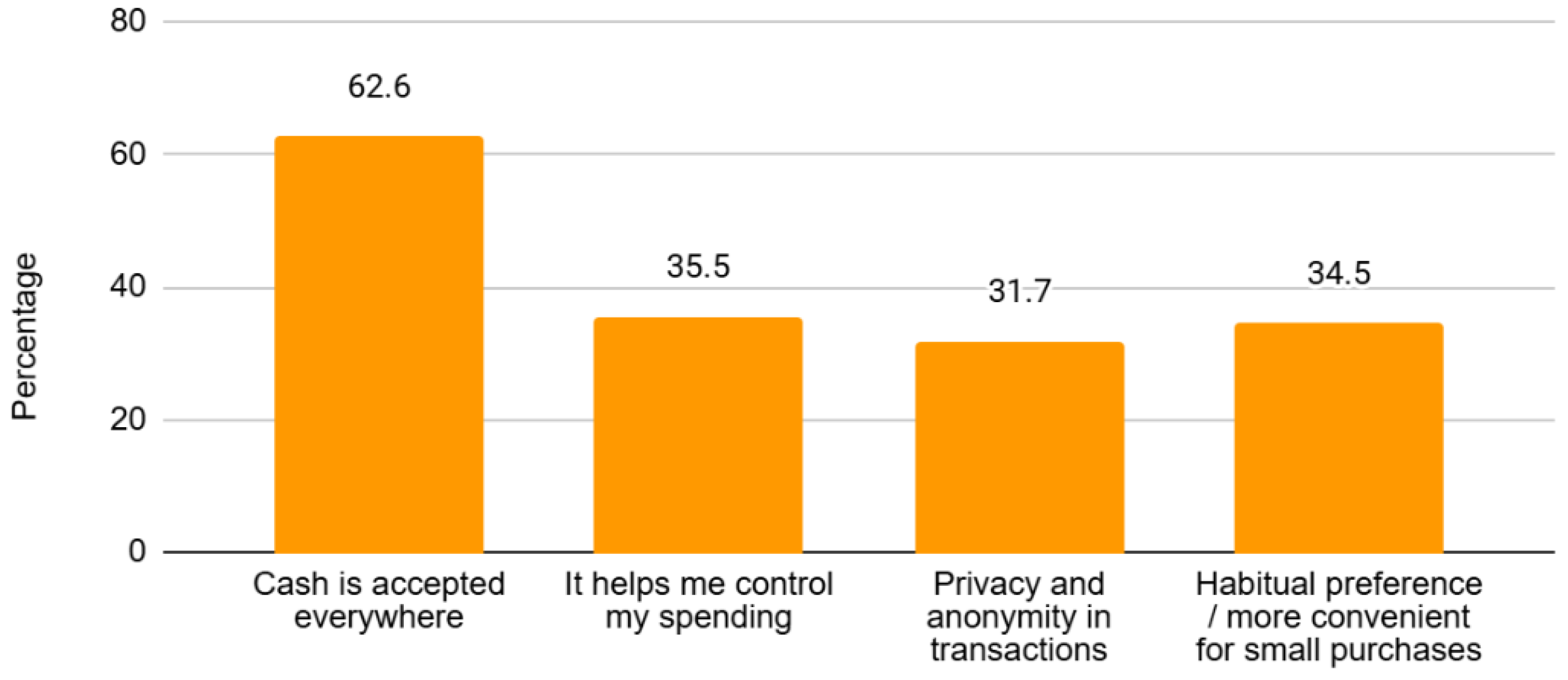

In terms of digital financial literacy (DFL) levels, 10.1% of the respondents have self-reported that they have lowest literacy level, another 10.7% ranked their literacy to be modest. Another 33% of respondent reported average DFL, and around 28.2% self-reported that they have a good DFL, and 18% reported that they have highest literacy. When asked about awareness of the e₹ (digital currency), a majority of the respondents (51%) said they are aware of e₹. However, when were asked about willingness to shift (WTS) to digital currency, 85% expressed their willingness and 15% are reluctant. Since the major objective of the study is to understand the adoption of the e₹ it is important to understand the existing preferences of the transactions by the respondents. In terms of payment preferences, a clear inclination toward digital modes is observed — about 58% of respondents preferred using UPI, while 14.2% preferred cash payments, and 27.8% reported using both UPI and cash equally. Further, this preference has been explored to know the rationale in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3.

Among those who preferred UPI (58%) a majority (69.3%) stated that they prefer UPI because it is quick and easy to use, followed closely by no need to carry physical cash (62.8%) and availability of transaction history (62.7%). Additionally, 46.4% believed that UPI is a secure and trusted mode of payment, while 38.3% valued it for cashback offers and promotional incentives.

Those who preferred cash transactions constituted 14.2% of the total respondents (n = 751). Among them, the most common reason for preferring cash was its universal acceptability (ranked I by 62.6% of cash users). This suggests that cash continues to be valued for its widespread usability and dependability in all kinds of transactions. The next major reason was the perception that cash helps control spending (35.5%), followed by habitual use (34.5%) and privacy concerns (31.7%).

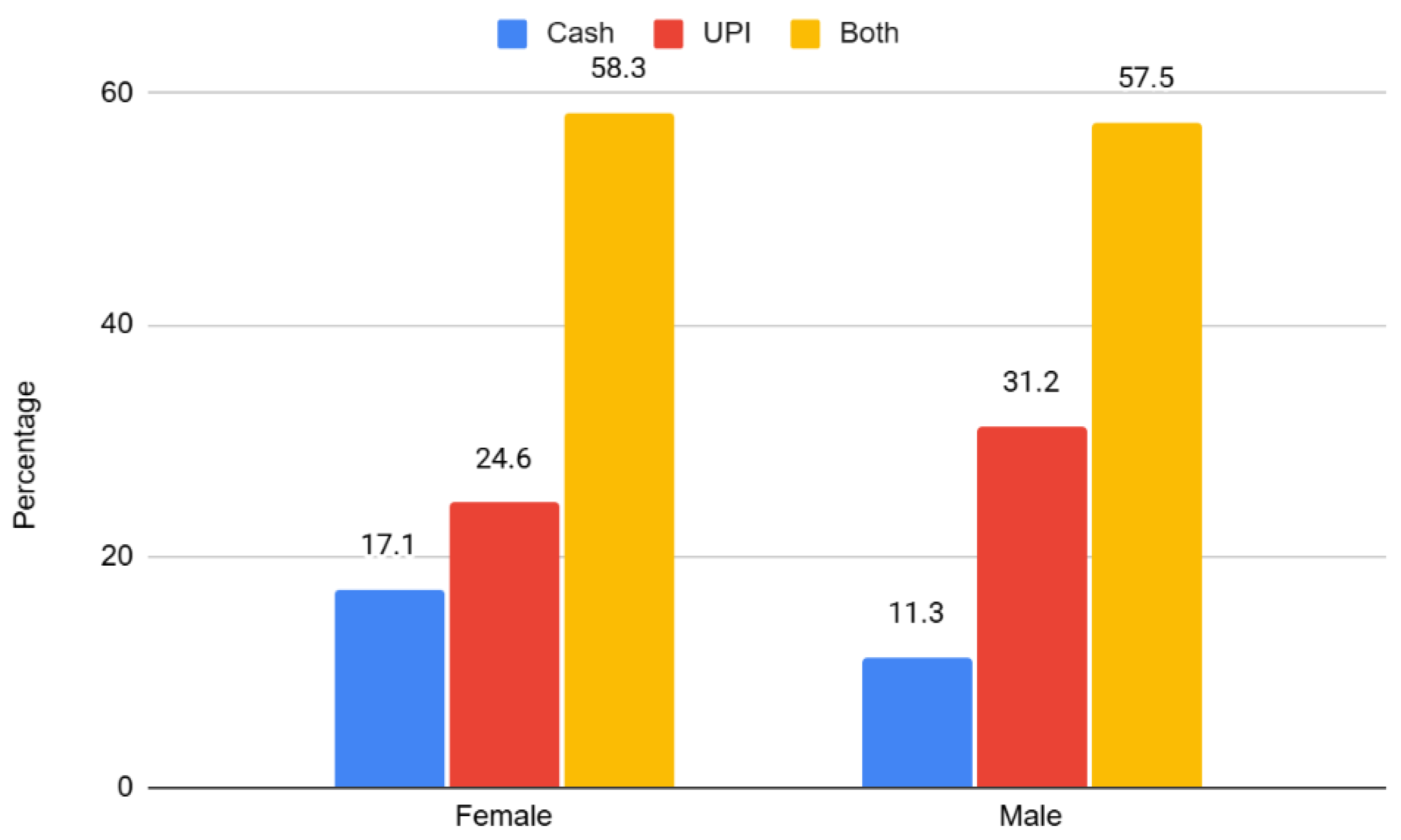

The gender orientation towards the payment mode is mapped in

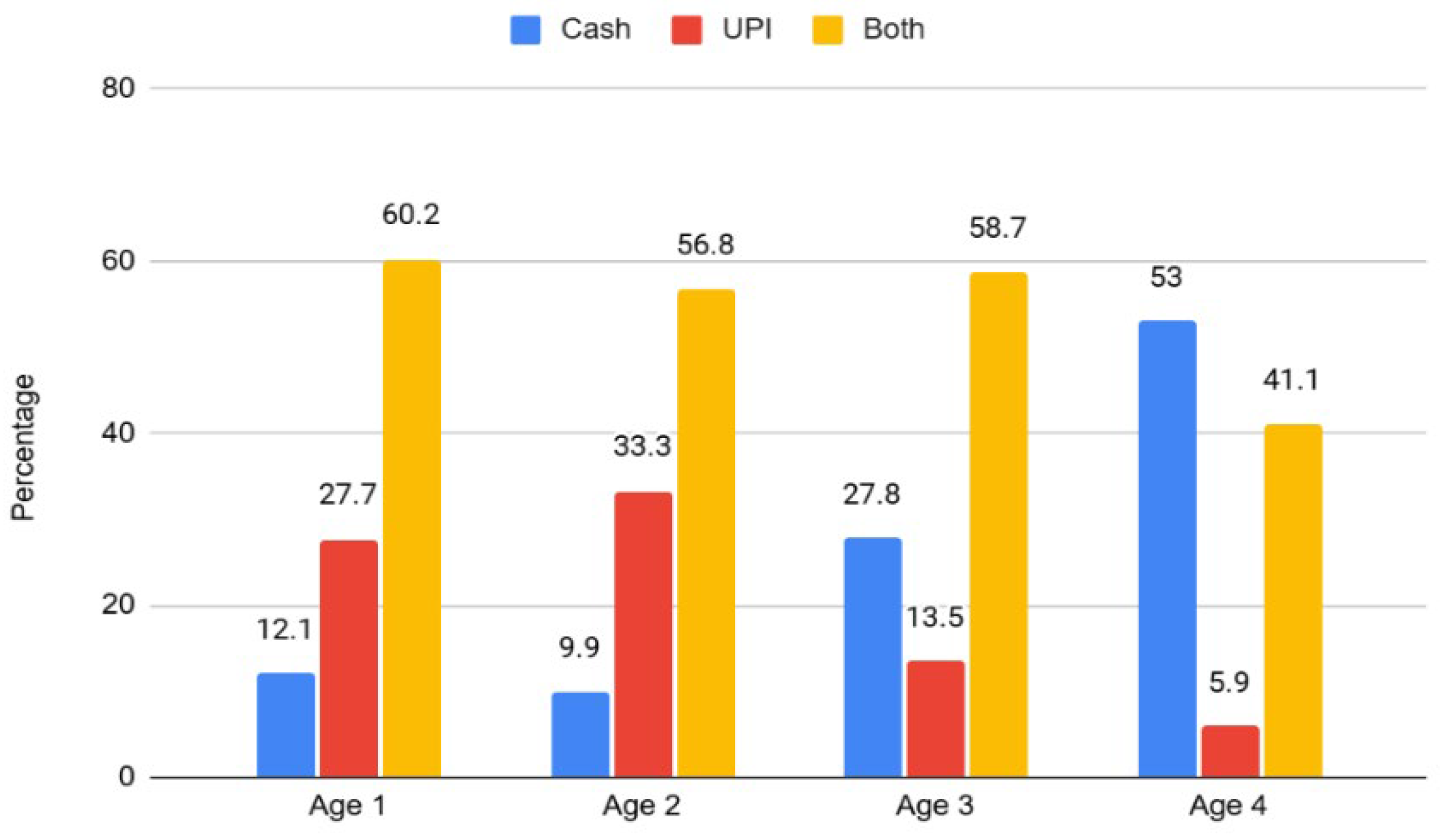

Figure 4 to understand inclinations based on gender. It is quite clear that, both men and women prefer both UPI and Cash. However, the preference of UPI is slightly higher from male (31.2%) than female (24.5%). Whereas preference for cash is slightly higher from female (17.1%) than male (11.4%). Though the difference is very minor, it does tell us the gender orientation towards the payment mechanisms. Further in terms of age, we can observe from

Figure 5 that though all the age groups prefer both cash and UPI, it can be seen that older respondents (above 61 years) prefer cash (53%) than UPI (5.9%) and younger respondents have more preference towards UPI (27.7%) than cash. This clearly indicate that, digital literacy is one of the key determinants of understanding the e₹ adoption.

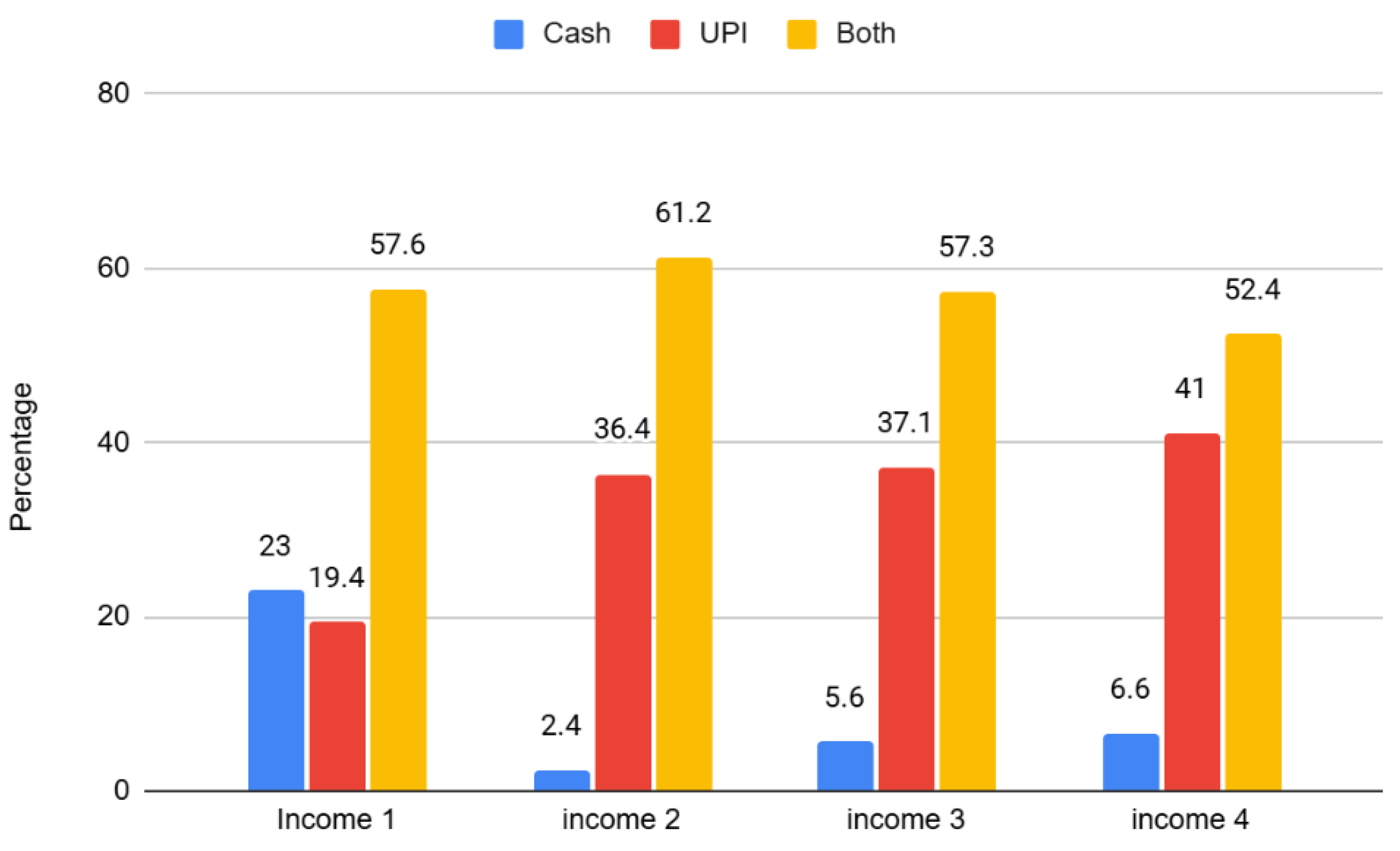

Further in terms of income (

Figure 6), majority of the income groups preferred both UPI & cash. However, higher income category (above Rs. 1lakh) prefers UPI (41%) than the lower income groups. This clearly indicates that, the preference for the payment model is based on the income.

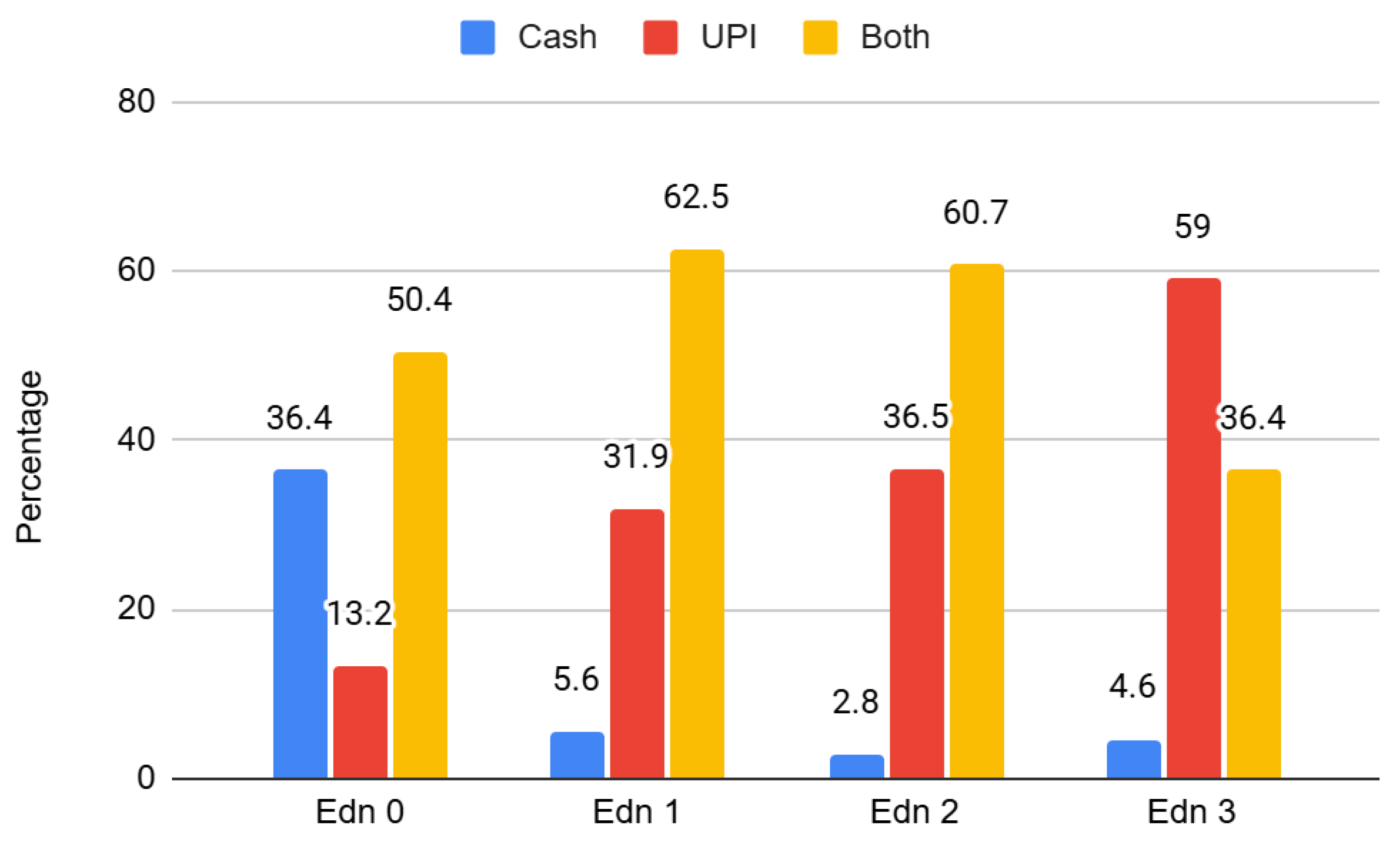

In terms of education, it can be observed from

Figure 6 that, respondents who belong to edu1 (education above PG) rely more on digital payments like UPI (59%) and less on cash (4.6%). Whereas all other groups use both UPI and cash as their daily payment mode. However, edu0 (education less than 12th) prefer more of cash (36.4%) than UPI (13.2%). This variation clearly indicate that education is a significant factor in understanding the e₹ adoption in India.

From this descriptive analysis, it is clear that there is a clear transition trend in the economy towards UPI. At this juncture, introducing e₹ has been game changer. To understand the factors affecting its adoption, the study relied on econometric modelling which provide the policymakers key insights to make e₹ more viable. The details of the modelling is provided in the next section.

Figure 7.

Education-wise Payment Preference. Source: Author’s calculation based on primary survey.

Figure 7.

Education-wise Payment Preference. Source: Author’s calculation based on primary survey.

Methodology

The study relied on binary logit model whose rationale is provide in this section. When the response variable Y follows a Bernoulli distribution of parameter μ, then the generalized linear model (GLM) uses the logit function as the canonical link function and becomes a logistic regression model. As , then =P (=1) (adopted from Costa e Silva et al., 2020). The variable e₹aware and WTS (Willingness to Shift) are dichotomous variable Y such that

Model 1: Y1=1 if they are aware, and 0 otherwise and

Model 2: Y2=1 if they are willing to shift to e₹ and 0 otherwise.

The logit model predicts the logit of Y from X which represents a natural logarithm of odds of Y. The model is written (following Peng et al., 2002; Akinyemi et al., 2021) as:

where ln is the log-odds and p is the probability of the outcome given that X=

. The LR model has a logit that is linear in X, which can be written as:

where α is the parameter of Y-intercept and β is the parameter of the slope. X can be a qualitative (categorical) or quantitative variable, and Y is always categorical in the binary logit regression. The equation can be extended for multiple linear regression as

where Li =1 is probability of outcome; 0 otherwise.

is the error term. When applied to the current study, the Li =1 is the awareness of e₹ and 0 otherwise and WTS to e₹ and 0 otherwise.

To estimate the regression coefficients of the GLM model, the maximum likelihood method is used. The estimates for β are obtained as a solution of a system of likelihood equations, that is usually solved using the Nelder and Wedderburn algorithm, which is an iterative method that uses Fisher’s information matrix. Note that several methods may be used to estimate the coefficients of a GLM model (e.g., Bayesian methods and M-estimation) (Costa-e-Silva et al., 2020).

The binary logit regression results are presented in terms of odds ratios and marginal effects. Odds ratios reveal the impact of independent variables on the odds of obtaining a ‘better’ outcome, while marginal effects denote the change in the probability of a ‘better’ outcome due to a unit change in the independent variable.

Data Analysis and Results

The study has examined the factors determining e₹ awareness and the willingness to shift to e₹ using binary logit regression model. The description and summary statistics of the variables adopted in the model are provided in

Table 1.

Model 1: Factors Affecting e₹ Awareness

The logistic regression model examining the factors affecting e₹ awareness based on income, age, gender, awareness, having bank account, digital financial literacy, perceived convenience, perceived trust on the operation and perceived belief on the e₹ role in future are provided in

Table 2. overall LR (

) (12) = 74.23, ρ<0.001, indicating that the predictors jointly explain the dependent variable. The pseudo R

2 value of 0.0713 suggest that approximately 7 percent of the variance in the dependent variable can be explained by the model.

Table 2 provides the logistic regression estimation with their odds-ratio (exp(β)). Following Sperandei (2014) and Peng & So (2002), the study will report and interpret the odds-ratio. The predictors like age, income, education, digital financial literacy are found statistically significant. In case age, the base category is age4 (above 61 years), the odds of e₹ awareness decreases with lower age group. This indicates that, as increases, the e₹ awareness will also increase. Similar result is found in case of education which is showing positive and significant results. For instance, compared to lower educated respondent (less than 12th Standard), the e₹ awareness will increase with education among who did graduation, PG and above PG by 148%, 139%, and 136% respectively. One of the interesting results are found in case of income category where, compared to lower income group (less than 25000), higher income category respondents have higher probability of e₹ awareness. For instance, the income group of Y1 though have odds of 41% higher probability of e₹ awareness, but the variable is found insignificant. However, the income group of Y2, Y3 are found higher probability of 174% and 105% respectively. This indicates that higher income group people are more aware of e₹ in the study area. Another important variable of the model is digital financial literacy, which is taken as the ordinal variable. This perceived literacy is found positive and significant, indicating that, one level increase in the literacy level increases the odds of being aware of e₹ by approximately 30%, controlling other variables.

To make the result interpretation more intuitive, the study adopted the change in probability by calculating marginal effect. Marginal effects are more preferable for behavioral and policy interpretation (Norton et al., 2024). Following this, the study results of marginal effects are provided in

Table 3.

The predicted probabilities of education is showing positive and significant results. This indicates that compared to less educated respondents (edu0), higher educated respondents like those who have completed graduation have 22% higher probability of e₹ awareness and among those who have more than PG education have 28% higher probability of the awareness. In case of age group, compared to older age group (Age4), people belonging to age1, age2 and age3 are less likely to be aware of e₹. For instance, respondents belonging to less than 25 years of age have nearly 14.4% less likely to know about e₹. Similar with people belonging to age2 (26-45 years) have 10.7% less likely to know about e₹. Income group is found to have significant impact on the awareness. Compared to lower income group (Y0), income group of Y2, Y3 are found to have positive and significant value, except for Y1. This indicates that, people with higher income group have the higher probability of digital currency awareness. To elaborate, people belong to Y2 (50000 to 1lakh) have nearly 13.7% higher probability of e₹ awareness compared to people belonging to Y1 (less than 25000). Similarly, people who earn more than 1 lakh (Y3) have around 17.3% higher probability of e₹ awareness compared to Y1.

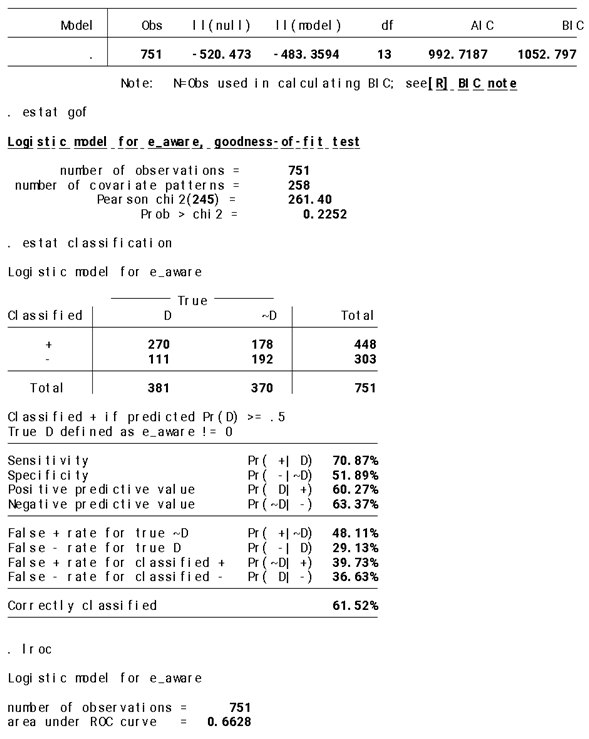

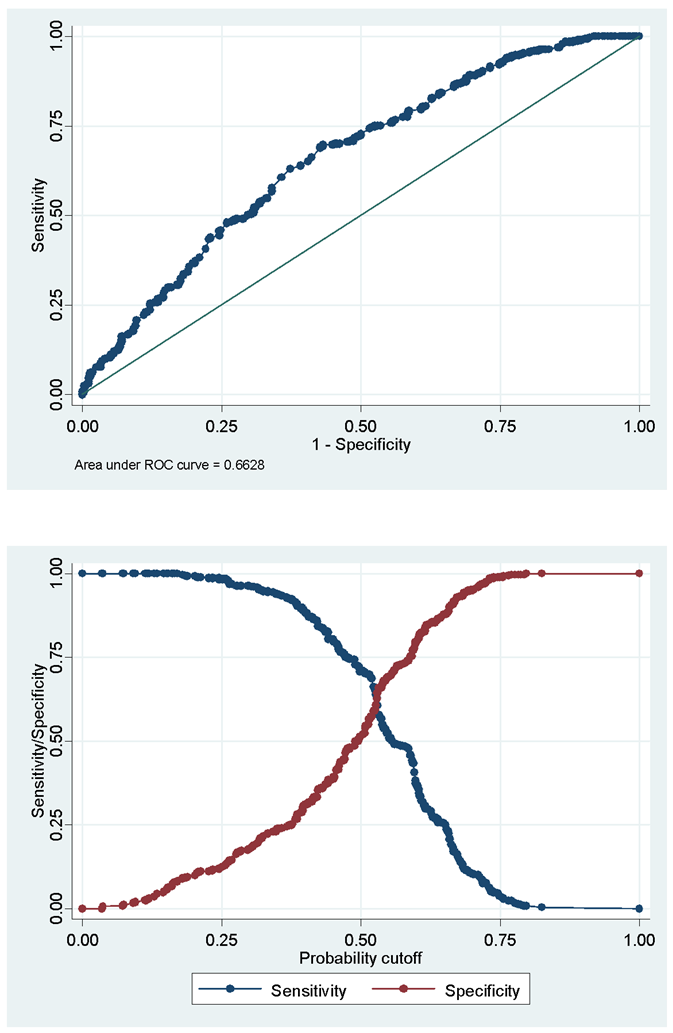

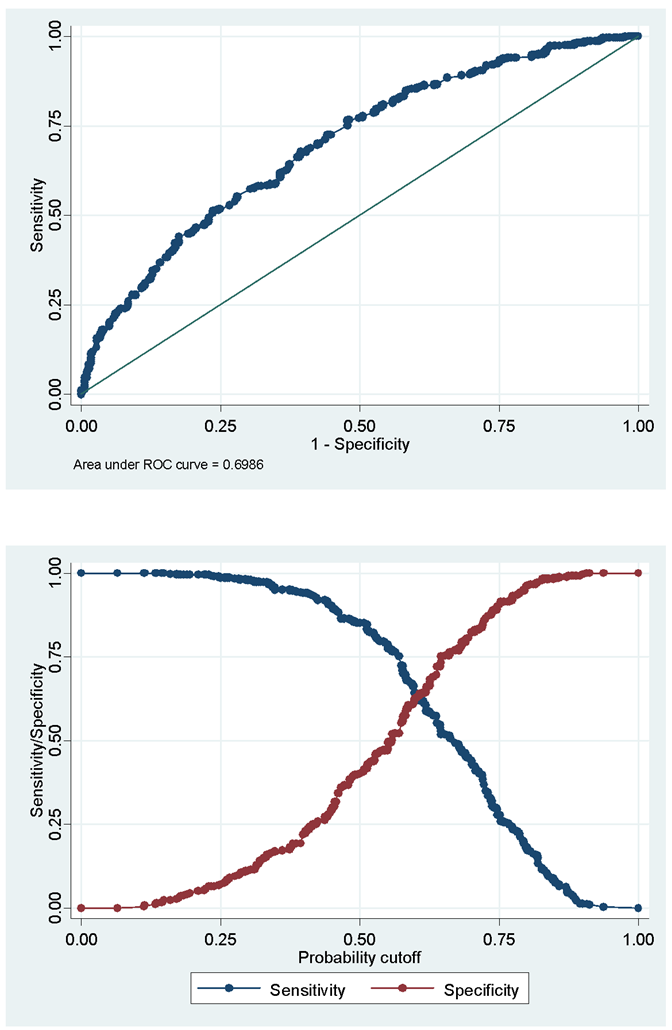

Model Validation (Results are Provided in Appendix A.1)

The fitted model’s log-likelihood (-483.35) is higher (less negative) than null model’s log-likelihood (-520.47). this indicates that including the predictors in the model improves the model fit compared to using only the intercept. Further, the study conducted the Goodness of fit test (Hosmer-Lemeshow Test) to evaluate whether the predicted probability from the model match the actual data. the null hypothesis is framed as the model fits the data well. The p value of this model is 0.2252 which is greater than 0.05, we fail to reject H0. This mean model shows no significant lack of fit. The predicted probability is consistent with the observed data. Further, the study developed classification table (confusion matrix) to evaluate how well a classification model predicts the outcome. The

Appendix A provides the details of the matrix. Around 270 cases are correctly predicting the e₹ awareness and around 178 cases are incorrectly predicted the e₹ awareness but actually they don’t. Further, around 192 cases are correctly predicted as not aware e₹ and 111 cases predicted as not aware of e₹ but are actually aware. The sensitivity (Recall/True positive rate) is 70.8% are actual aware are correctly predicted. Around 51.8% of not aware are correctly predicted (specificity). The model is good to identify those who are not aware. Among those who predicted as aware of e₹, 60.2% are truly aware and among those who are predicted as not aware, 63.3% are truly not aware. The ROC and sensitivity curves of the model is provided in Apprendix. The ROC Curve (Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve) showing that the model has a 66% probability of correctly ranking a randomly chosen positive instance higher than a randomly chosen negative instance. The ROC and specificity curves are provided in

Appendix A.

Model 2: Factors Affecting Willingness to Shift (WTS) to e₹

The logistic regression model examining the likelihood of willingness to shift to e₹ adoption based on income, age, gender, awareness, having bank account, digital financial literacy, perceived convenience, perceived trust on the operation and perceived belief on the e₹ role in Indian Financial system are provided in

Table 4. overall LR (

) (13) = 95.63, ρ<0.001, indicating that the predictors jointly explain the dependent variable. The pseudo R

2 value of 0.0949 suggest that approximately 9.4 percent of the variance in the dependent variable can be explained by the model.

The predictors like age, having bank account, e₹_awareness, digital financial literacy, perceived convenience and perceived belief on the e₹ role in future are found statistically significant. The odds ratio of e₹ awareness is 1.54 (p=0.010) indicate that odds of WTS to e₹ would increase by 54% with an increase in e₹ awareness. In case of digital financial literacy, the odds-ratio is 1.32 (p=0.000) which suggest that, for each unit increase in this scope, the odds of WTS to e₹ increase by 32%. Similarly perceived convenience and perceived belief on future of e₹ have the odds ratio of 2.41 and 2.66 (p=0.000) indicate that for every unit in perceived convenience and belief in the future of e₹ the WTS to e₹ would increase by 141% and 166% respectively. In case of age, compared to base age group of less than 25 years, people belonging to higher age group are more WTS to e₹. Further, odds of WTS to e₹ increases with increase in bank account by 213% (odds ratio is 3.13, p=0.010), however it is significant at 10% level of significance. Further, though all the categories of income is not showing significant probability, we can observe the higher category of income (Y3) have higher probability to WTS to e₹ compared to lower income category.

The predicted probability of e₹ awareness is 0.10 (p=0.010) indicate that compared to that respondents who are aware of e₹ have higher probability to shift to e₹ by 10% again those who are not aware of e₹. In case of digital financial literacy, the predicted probability of 0.06 indicate that with every one unit increase in the literacy, the WTS to e₹ would increase by 6%. In case of those who perceive e₹ as convenient and believe in its role in future have the predicted probability of 0.21 and 0.24 (p=0.000) respectively suggesting, WTS to e₹ would increase by 21% and 24% by those who perceive e₹ as convenient and future belief. One of the interesting findings of the study is related to trust on e₹. The variable is found insignificant and negative indicating that, in case of India’s CBDC, trust is not a key determinant for adoption.

Table 5.

Marginal effects on WTS model.

Table 5.

Marginal effects on WTS model.

| variable |

dy/dx |

Std. Err. |

z |

P>|z| |

[95% C.I.] |

X |

| |

|

|

|

|

Lower |

Upper |

|

| gen |

-0.01926 |

0.04016 |

-0.48 |

0.631 |

-0.09797 |

0.059435 |

0.486019 |

| y1 |

-0.01927 |

0.05057 |

-0.38 |

0.703 |

-0.11838 |

0.079841 |

0.219707 |

| y2 |

0.047966 |

0.05584 |

0.86 |

0.39 |

-0.06149 |

0.157417 |

0.165113 |

| y3** |

0.137449 |

0.06839 |

2.01 |

0.044 |

0.00340 |

0.271498 |

0.081225 |

| e_aware*** |

-0.10217 |

0.03956 |

2.58 |

0.010 |

0.02463 |

0.179708 |

0.507324 |

| Bankac*** |

0.278182 |

0.11145 |

2.50 |

0.000 |

0.05973 |

0.496627 |

0.966711 |

| dfl*** |

0.06685 |

0.01682 |

3.98 |

0.000 |

0.03392 |

0.099865 |

3.33289 |

| pr_convc*** |

0.240206 |

0.07414 |

3.74 |

0.001 |

0.10258 |

0.328307 |

0.860186 |

| pr_ifs_tr*** |

0.134448 |

0.05006 |

3.24 |

0.007 |

0.09489 |

0.385519 |

0.92277 |

| age1*** |

0.12677 |

0.06435 |

2.79 |

0.049 |

0.03787 |

0.215683 |

0.443409 |

| age2** |

0.255045 |

0.07862 |

5.96 |

0.091 |

0.17113 |

0.338963 |

0.206391 |

| age3** |

0.13319 |

0.07886 |

1.69 |

0.091 |

-0.02137 |

0.028775 |

0.045273 |

| trust |

-0.04802 |

0.16184 |

-0.30 |

0.767 |

-0.36521 |

0.269174 |

0.015979 |

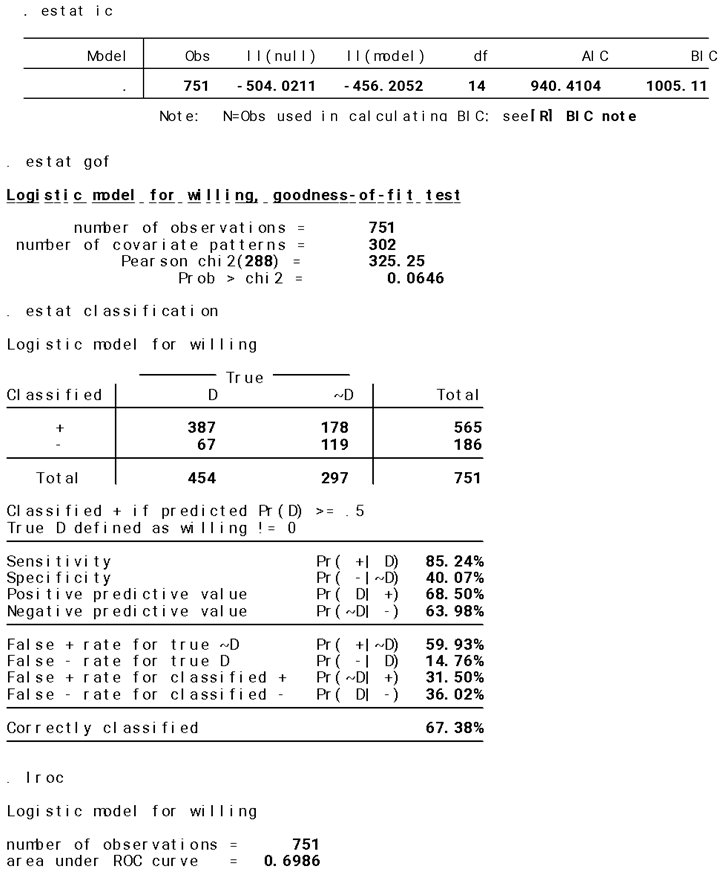

Model Validation (Results are Provided in Appendix A.2)

The fitted model’s log-likelihood (-456.2) is higher (less negative) than null model’s log-likelihood (-504.02). this indicates that including the predictors in the model improves the model fit compared to using only the intercept. Further, the study conducted the Goodness of fit test (Hosmer-Lemeshow Test) to evaluate whether the predicted probability from the model match the actual data. the null hypothesis is framed as the model fits the data well. The results of all the test are provided in

Appendix A. We can see that the p value of this model is 0.064 which is greater than 0.05, we fail to reject H0. This mean model shows no significant lack of fit. The predicted probability is consistent with the observed data. Further, the study developed classification table (confusion matrix) to evaluate how well a classification model predicts the outcome. The

Appendix A provides the details of the matrix. Around 387 cases are correctly predicting the WTS to shift and around 178 cases are incorrectly predicted as WTS to e₹ but actually they don’t. Further, around 119 cases are correctly predicted as not WTS to e₹ and 67 cases predicted as not WTS to e₹ but are actually WTS. The sensitivity (Recall/True positive rate) is 85.2% are actual WTS are correctly predicted. Around 40% of non WTS are correctly predicted (specificity). The model is good to identify those who are not WTS. Among those who predicted as WTS to e₹, 68.5% are truly WTS and among those who are predicted as not WTS, 63.9% are truly not WTS. The ROC and sensitivity curves of the model is provided in Apprendix. The ROC Curve (Reciever Operating Characteristic Curve) showing that the model has a 69% probability of correctly ranking a randomly chosen positive instance higher than a randomly chosen negative instance. The ROC and specificity curves are provided in

Appendix A.

Discussion & Implications

This paper has investigated factors determining both e₹ awareness and the willingness to shift to e₹. By adopting the TAM model for the first time to understand e₹ adoption, this paper makes a novel contribution to the existing literature. The behavioral aspect of users like perceived convenience, perceived trust and perceived belief in the e₹ in the financial system has been empirically tested using the econometric model. By collecting primary data, the study makes key observations on the e₹ adoption. In the study sample (751), it is observed that only a smaller share of respondents (14.2%) primarily use cash, they do so mainly due to its accessibility and familiarity. A majority of respondents (58%) are using UPI and is preferred primarily for its speed, convenience, and record-keeping benefits, highlighting the growing comfort of users with digital payments and the influence of ease and incentives in shaping payment behavior. In terms of income groups, a majority of the lower-income groups are still heavily dependent on cash transactions, whereas higher-income groups are gradually transitioning toward digital payment modes, consistent with India’s push toward a cashless economy.

By adopting the binary logit regression, the study examined the possible impacts on e₹ adoption in the country. It is found that, income, age and education positively influence the e₹ awareness and also willingness to shift to e₹. Income especially signifies that higher income level will increase the access to information and thereby the awareness. Since the economy is growing fastly, this indicates, e₹ has huge potential in the payment landscape. One of the key variables of the study is the digital financial literacy, which is found positive and significant. This signifies that, public investment in enhancing the digital financial literacy is of paramount importance to increase the e₹ awareness and thereby adoption.

In the second model, the paper relied on stated preference method to elicit the willingness to shift to e₹ and found that behavioral variables have significant influence. By introducing the information about e₹ operation, the study provided an information nudge to the respondents to elicit their WTS to e₹. this unique blend of nudge theory with stated preference model stands novel in the finance literature. Apart from socio-economic variables like age, income and digital financial literacy, perceived convenience, perceived belief in e₹ as future currency found to have positive and significant influence on WTS to e₹. A key finding of the study is related to trust factor. The variable is though found insignificant, has negative sign, indicating that, trust is not a key factor in influencing people’s WTS to e₹. This forms an important policy insight, as there are many studies in other countries which identified institutional trust as a key deterrent of adoption. However, in our sample nearly 85% respondent believe that e₹ will play crucial role in the financial system transformation in the future and we can argue that, people hold trust on RBI and its initiatives are well taken in the past. Even though nearly 97% have their bank accounts, only 18% of them reported they have good digital financial literacy. The study found that digital financial literacy as the key factor in improving the e₹ adoption in the country. Hence, if the e₹ adoption to improve, more awareness especially in the digital education would make the digital currency of India more successful.

Limitations of the Study

Though the study has made novel attempt in examining the e₹ adoption by using primary data, there are certain limitation the study undergoes. Especially, the study adopted simple random sampling method, which though remove the sampling bias, is quite simple technique of sampling which might average out the sample. Further, there are chances of self-reporting error in the data collected.

Conclusions & Policy Suggestions

Majority of the economies today are experimenting with CBDC adoption. India has been forerunner in introducing digital currency by name e₹. Wide array of research in CBDC has investigated the macroeconomic effects of CBDC than the adoption part. One of the key elements in the CBDC adoption is behavioral aspect. This study has made a novel attempt in adopting the most widely used model TAM in e₹ domain. Addition to this, the study is first of its kind to use extensive primary data to understand the e₹ adoption and the willingness to shift to e₹ for a major metropolitan city of India. Given the pre-exiting payment ecosystem, the stand at a key juncture to provide policy insights to policymakers. Our study suggests that, apart from technical part of e₹, behavioral intention of users especially awareness and digital financial literacy have significant impact on the e₹ adoption. Further, the study made a innovative attempt bring the stated preference method and nudge theory to fintech domain. The willingness to shift to e₹ has been examined and the result has provided key insights to policymakers. For instance, with the general education, a targeted awareness program on e₹ will have significant positive effect on its adoption. Further, users have given more preference for the behavioral aspects like perceived convenience and perceived ease of use while eliciting their preference towards WTS to e₹. Lastly, in case of India, trust on e₹ mechanism is found to be insignificant, indicating that, users have good trust on the monetary authority of the country and would be willingness to adopt e₹ when provided with proper education and incentives.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation: Vijayalakshmi; Methodology: Vijayalakshmi; Software: Vijaya-lakshmi; Validation: Vijayalakshmi and Pallavi; Formal analysis: Vijayalakshmi; Inves-tigation: Vijayalakshmi and Pallavi; Resources: Vijayalakshmi and Pallavi.; Data curation: Vijayalakshmi and Pallavi; Writing—Vijayalakshmi: X.X.; Writing— Vijayalakshmi and Pallavi: X.X.; Visualisation: Pallavi; Supervision: Vijayalakshmi; Project administration: NA.; Funding acquisition: NA. All authors have reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript for publication.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study as per ICMR (Indian Council of Medical Research) as the study involved minimal risk to participants and did not collect any sensitive or personally identifiable information.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Participants were informed orally about the objectives of the study, their right to withdraw at any stage, and the confidentiality of their responses. Verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection, consistent with ethical guidelines for low-risk social science research where written consent is not mandatory.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in the study is collected by primary survey. The data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Model Validation of e₹ Awareness

Appendix A.2. Model Validation on WTS

References

- Adel, N. (2024). The impact of digital literacy and technology adoption on financial inclusion in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Heliyon, 10(24). e40951. [CrossRef]

- Agur, I., Ari, A., Dell’Ariccia, G. (2019). Designing Central Bank Digital currencies. ADBI Working Paper. IMF Working Papers (Issue 1065). https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2019/11/18/Designing-Central-Bank-Digital-Currencies-48739.

- Ahnert, T., Assenmacher, K., Hoffmann, P., Leonello, A., Monnet, C., Porcellacchia, D. (2022). The Economics of Central Bank Digital Currency. European Central Bank. Working Paper Series No. 2651. Accessed from https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpwps/ecb.wp2713~91ddff9e7c.en.pdf.

- Ahnert, T., Hoffmann, P., Leonello, A., Porcellacchia, D. (2023). Central Bank Digital Currency and Financial Stability. Working Paper 2783. Accessed from https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpwps/ecb.wp2783~0af3ad7576.en.pdf.

- Akinyemi, E.K., Ogunleye, O A., Olaoye, H O., Brakory, J. (2021). Binary Logistic Regression Analysis on Predicting Academics Performance. Current Journal of Applied Science and Technology. 40(20), 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Auer, R., Cornelli, G., Frost, J. (2021). Rise of the Central Bank Digital currencies: drivers, approaches and technologies. SSRN Electron. J. 880. [CrossRef]

- Bains, A., Gupta, R., & Sharma, P. (2023). Digital currency adoption and financial inclusion: Evidence from emerging economies. Journal of Digital Finance, 12(3), 145–162.

- Banerjee, S. & Sinha, M., (2023) Promoting Financial Inclusion through Central Bank Digital Currency: An Evaluation of Payment System Viability in India, Australasian Accounting, Business and Finance Journal 17(1), 176-204. [CrossRef]

- Bank for International Settlements. (2020). Central Bank Digital Currencies: Foundational Principles and Core Features, vol. 1. Bank for International Settlements.

- Bank for International Settlements. (2020a). Central banks and payments in the digital era. BIS Annual Economic Report, Bank for International Settlements.

- Bank, R. (2022). Concept Note on Central Bank Digital Currency. October.

- Barkhordari, M., Nourollah, Z., Mashayekhi, H., Mashayekhi, Y., Ahangar, M.S. (2017). Factors influencing adoption of e-payment systems: an empirical study on Iranian customers. Inf. Syst. E Bus. Manag. 15 (1), 89–116. [CrossRef]

- Barontini, C., Holden, H. (2019). Proceeding with caution – a survey on central bank digital currency. BIS Papers No. 101. Accessed from https://www.bis.org/publ/bppdf/bispap101.htm.

- Bhaskar, R., Hunjra, A.I., Bansal, S., & Pandey, D.K. (2022). Central bank digital currencies: Agendas for future research. Research in International Business and Finance, 62, 101737. [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagr, P. (2025). Enhancing digital currency adoption: examining user experiences. Management Decision, 63(7), 2292-2316.

- Bhatnagr, P., Rajesh, A., & Misra, R. (2025). The impact of Fintech innovations on digital currency adoption: a blockchain-based study in India. International Journal of Accounting & Information Management, 33(2), 313-333.

- Bijlsma, Michiel, van der Cruijsen, Carin, Jonker, Nicole, Reijerink, Jelmer. (2021). What Triggers Consumer Adoption of Central Bank Digital Currency? TILEC Discussion Paper No. DP2021-009, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3839477 or. [CrossRef]

- Boros, E., Horvath, M. (2022). Central Bank digital currency: the next money revolution? Public. Finance. Quarterly. 67 (4), 506–521.

- Chawla, N.K. . (2023). Implications of Central Bank Digital Currency in India: A Critical Analysis. DME Journal of Law, 4(02), 22–28. [CrossRef]

- Costa E Silva, E., Lopes, I.C., Correia, A., & Faria, S. (2020). A logistic regression model for consumer default risk. Journal of applied statistics, 47(13-15), 2879–2894. [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340.

- Di Maggio, M., Ghosh, P., Ghosh, S.K., Wu, A. (2024) Impact of Retail CBDC on Digital Payments, and Bank Deposits: Evidence from India. NBER Working Paper 32457. Accessed from http://www.nber.org/papers/w32457.

- Dixit, V., Shailesh, A., Mishra, S., & Verma, R. (2025). Adoption of Central Bank Digital Currency in India: A Structural Model Using ISM. NMIMS Management Review, 0(0). [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z., Umar, M., Yousaf, U.B., & Muhammad, S. (2024). Determinants of central bank digital currency adoption–a study of 85 countries. Journal of Economic Policy Reform, 27(3), 316-330.

- Elsayed, A.H., Nasir, M.A. (2022). Central bank digital currencies: an agenda for future research. Research in International Business and Finance, 62, 101736. [CrossRef]

- Fadli, J.A., Hamsal, M., Rahim, R., & Furinto, A. (2023). Investigating The Adoption Factors Of Indonesia’s Central Bank Digital Currency. Quality-Access to Success, 24(196).

- Fernández-Villaverde, J., Sanches, D., Schilling, L., Uhlig, H. (2021). Central bank digital currency: Central banking for all? Review of Economic Dynamics 41, 225–242.

- Garg, M., Malik, S. & Kumar, P. (2025). Decoding challenges in central bank digital currency implementation in India: a TISM-MICMAC approach. Quality & Quantity. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, D., Chowdhury, S.R., & M, A. (2023). The Influence of Economic Perception on the Adoption of App-based Financial Transactions: A Study Among the Young Population in India. Global Business Review, 09721509231197719.

- Rahi S, Abd. Ghani M (2018), “The role of UTAUT, DOI, perceived technology security and game elements in internet banking adoption”. World Journal of Science, Technology and Sustainable Development, Vol. 15 No. 4 pp. 338–356. [CrossRef]

- Huynh, K.P., Molnar, J., Shcherbakov, O., Yu, Q. (2020). Demand for Payment Services and Consumer Welfare: The Introduction of a Central Bank Digital Currency. Staff Working Paper.

- Inter-ministerial Committee. (2019). Report of the Committee to propose specific actions to be taken in relation to Virtual Currencies. Ministry of Finance, Government of India.

- Kelly, A.E., Palaniappan, S. (2023). Using a technology acceptance model to determine factors influencing continued usage of mobile money service transactions in Ghana. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 12, 34. [CrossRef]

- Kiff, M.J., Alwazir, J., Davidovic, S., Farias, A., Khan, M.A., Khiaonarong, M.T., Malaika, M., Monroe, M.H.K., Sugimoto, N., Tourpe, H. & Zhou, P. (2020). A survey of research on retail central bank digital currency. IMF working paper No.20/104.

- Koonprasert, T.T., Kanada, S, Tsuda, N., and Reshidi, E. (2024). Central Bank Digital Currency Adoption: Inclusive Strategies for Intermediaries and Users. Fintech Notes, 005. Accessed November 4, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, M., Nayak, K.M., & Bhatt, V. (2023). Examining the factors influencing fintech adoption behaviour of gen Y in India. Cogent Economics & Finance, 11(1). [CrossRef]

- Kumari, D. (2022). Digital Currency Transition in India: Prospects, Difficulties and the Way Forward. National Centre for Good Governance. https://ncgg.org.in/sites/default/files/lectures-document/Deepanjali_Kumari.p.

- Xu, J. (2022). Developments and implications of central bank digital currency: The case of China e-CNY. Asian Economic Policy Review, 17(2), 235-250. [CrossRef]

- Luu, H.N., Nguyen, C.P., Nasir, M.A. (2023). Implications of central bank digital currency for financial stability: Evidence from the global banking sector. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions & Money 89.

- Nayak, D.V., & Kumar, A.A. (2025). Central Bank Digital Currency E-Rupee (e) Usage Patterns: The Interplay of Awareness and Satisfaction in India. Indian Journal of Finance, 19(2), 62–74. [CrossRef]

- Norton, E C., Dowd, B E., Garrido, M M., Maciejewski, M L. (2024). Requiem for odds ratios. Health Services Research. 59(4):e14337. [CrossRef]

- Oh, E.Y., & Zhang, S. (2022). Informal economy and central bank digital currency. Economic Inquiry, 60(4), 1520–1539. [CrossRef]

- Ozili PK (2023), Central bank digital currency research around the world: a review of literature. Journal of Money Laundering Control, Vol. 26 No. 2 pp. 215–226. [CrossRef]

- Ozili, P.K., & Alonso, S.L.N. (2024). Central bank digital currency adoption challenges, solutions, and a sentiment analysis. Journal of Central Banking Theory and Practice, 1, 133–165.

- Peng, C J., & So T H. (2002) Logistic Regression Analysis and Reporting: A Primer, Understanding Statistics: Statistical Issues in Psychology, Education, and the Social Sciences, 1:1, 31-70. [CrossRef]

- Peng, C., Lee, K., Ingersoll, G. (2002). An introduction to logistic regression analysis and reporting. The journal of educational research. 96, 3-15.

- Prajapati, S., Kumar, S. (2025). Indian Digitally Payment Systems: UPI, ULI, CBDC – Challenges, Opportunities, and Prospects. Advances in Consumer Research, 2(4), 4864-4867.

- Priyadarshini, D. & Kar, S (2021). Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC): Critical Issues and the Indian Perspective. IEG working paper No. 444. Accessed from https://iegindia.org/upload/profile_publication/doc-240921_152405WP444.pdf.

- Putri, G.A., Widagdo, A.K., Setiawan, D. (2023). Analysis of financial technology acceptance of peer to peer lending (P2P lending) using extended technology acceptance model (TAM). Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 9(1). [CrossRef]

- Qu, B., Wei, L., Zhang, Y. (2022). Factors affecting consumer acceptance of electronic cash in China: an empirical study. Financial Innovation. 8 (1). [CrossRef]

- Raza, Ali & Tursoy, Turgut. (2024). Technology Acceptance Model and Fintech: An Evidence from Italian Banking Industry. Revista Mexicana de Economía y Finanzas. 20. 1-21. 10.21919/remef.v20i1.993.

- Reserve Bank of India. (2023). Concept note on Central Bank Digital Currency (E-Rupee). Mumbai: RBI Publications.

- Rogers, E.M. (1962). Diffusion of innovations (1st ed.). New York: Free Press of Glencoe. OCLC 254636.

- Sandhu, K., Dayananadan, A., Kuntluru, S. (2023). India’s CBDC for digital public infrastructure. Economics Letters, 220, Article 116978. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0165176523003270.

- Sankar, T.R. (2021). Central bank digital currency–Is this the future of money. Speech made in] Mumbai: Reserve Bank of India.

- Scaler report (2025). How Bangalore became Asia’s Silicon Valley, Accessed from https://thescalers.com/how-bangalore-became-asias-silicon-valley/.

- Schilling, L., Fernández-Villaverde, J., Uhlig, H. (2020). Central Bank Digital Currency: When Price and Bank Stability Collide. Journal of Monetary Economics 103554.

- Shekhar, V., & Ramesh, S. (2025). Central Bank Digital Currency in India: Perspectives on Design Choices and Implications of e-Rupee. Financial Services Review, 33(3), 61–79. [CrossRef]

- Sperandei S. (2014). Understanding logistic regression analysis. Biochemia medica, 24(1), 12–18. [CrossRef]

- Thaler, R.H., & Sunstein, C.R. (2009). Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. Penguin.

- Tronnier, F., Kakkar, S. (2022). Would you pay with a digital euro? Investigating usage intention in Central Bank Digital currency. SSRN Electronic Journal. [CrossRef]

- Wright, A., McKenzie, S.C., Bodie, L.R., & Belle, C.L. (2022). Financial inclusion and central bank digital currency in The Bahamas. Central Bank of The Bahamas. https://www.centralbankbahamas.com/viewPDF/documents/2022-09-23-13-49-13-CBDCupdated-paper.pdf.

- Xia, H., Gao, Y., Zhang, J.Z. (2023). Understanding the adoption context of China’s digital currency electronic payment. Financial Innovation, 9 (1). [CrossRef]

- Xu, J. (2022). Developments and implications of Central Bank Digital currency: the case of China e-CNY. Asian Economic Policy Review, 17 (2), 235–250. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. (2020). Opportunities, challenges and promotion countermeasures of central bank digital currency. Management Science Informatization and Economic Innovation Development Conference (MSIEID), 343–346. [CrossRef]

- Cheng J (2020) China rolls out pilot test of digital currency. Wall Street Journal, 20. Accessed on 3/1/2025 at: https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-rolls-out-pilot-test-of-digital-currency-11587385339.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |