1. Introduction

With the gradual increase in China’s urbanization rate and the rapid growth of motor vehicle ownership, the conflict between limited urban space and transportation supply and the continuously rising travel demand has become increasingly prominent. The resulting traffic congestion not only severely impacts the quality of residents’ daily travel and increases travel costs, but also triggers traffic accidents, causes environmental pollution, and leads to resource wastage, which is detrimental to the sustainable development of urban economies and societies. Consequently, urban traffic congestion issues have garnered increasing broad public concern [

1].

Urban road networks are interconnected systems composed of intersections and road segments. Ensuring the smooth operation of intersections and road segments is crucial for guaranteeing the reliable functioning and overall performance of the road network. However, due to the presence of signal control, intersections often become "bottlenecks" and are prone to congestion. Delay at intersections typically accounts for a significant proportion of total travel delay. On the one hand, through the control function of traffic signals, conflicting traffic flows are separated temporally, enhancing vehicle operational safety [

2]. On the other hand, it causes vehicles on the approaches to stop periodically, resulting in vehicle delay [

3]. When severe traffic congestion occurs at an intersection, it affects the traffic conditions on its upstream and downstream road segments. If congestion spreads further, the impacted area of the road network becomes wider [

4].

Given that intersections (hereinafter referred to as nodes) differ in their positions within the road network and their connectivity strength with neighboring nodes, their impact on the overall traffic operation of the network also varies. To address traffic congestion, it is necessary to identify critical node clusters that have a more significant impact on the traffic operation of the road network.

To study the impact of nodes on the network, influence (including traffic congestion) can be applied to the nodes, and subsequently, their effect on the entire network can be assessed. Such methods are commonly referred to as simulated attack methods. The primary way simulated attack methods exert influence is by directly removing the target nodes [

5]. The impact of the attack on the entire network is then evaluated mainly by selecting specific metrics, which primarily include relative loss of network efficiency [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10], relative loss of the largest connected component [

12,

13,

14], and network average path length [

11], etc. among which relative loss of network efficiency is the most frequently used.

Since traffic congestion does not cause physical impairment to the urban road traffic network, employing an attack method that directly removes nodes is evidently not very appropriate. Furthermore, existing node attacks are limited to single-point attacks and do not involve simultaneous attacks on multiple nodes, however, traffic congestion mitigation has a practical need for implementing measures simultaneously at multiple nodes. Simultaneously, the existing evaluation metrics for the impact of attacks on the network do not involve energy conservation and emission reduction.

Based on the above considerations, this research specifically focuses on the selection of critical intersection clusters in urban road congestion mitigation and their effects on energy conservation and emission reduction [

15].

2. Relationship Between Saturation Degree and Vehicle Emissions

Saturation degree is typically expressed as the ratio of actual traffic volume to capacity, and can be used to evaluate the operational status of road traffic. Generally, a higher saturation degree value corresponds to lower traffic operational efficiency and poorer level of service (LOS) for road traffic.

2.1. Relationship Between Speed and Saturation Degree

According to the "Code for Design of Urban Road Engineering" (CJJ37-2012), the relationship between the average operating speed V and saturation degree α on general urban road sections is shown in

Table 1.

Based on the data in

Table 1, the following linear relationship exists between speed and saturation degree.

2.2. Relationship Between Emissions and Speed

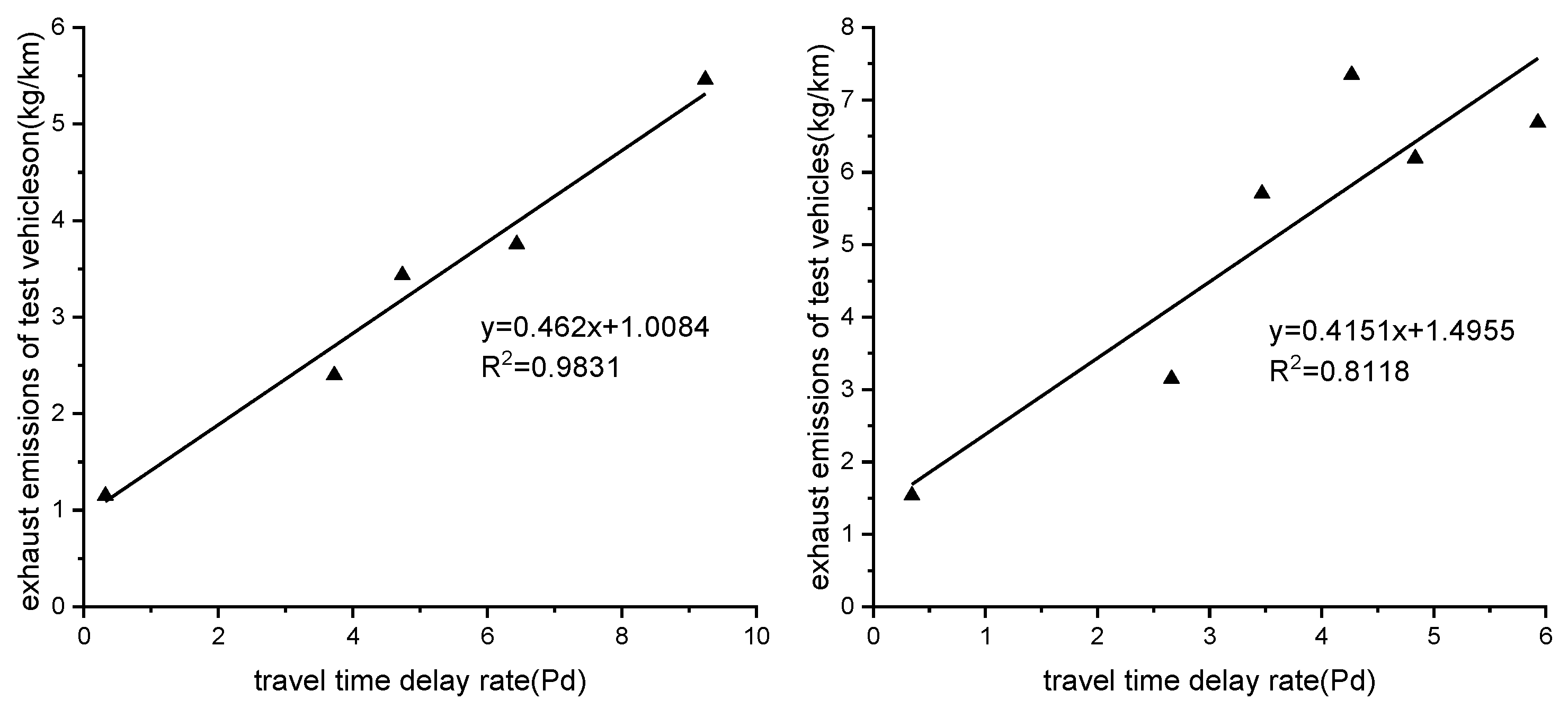

Shengyuan Ma et al. [

16]measured the relationship between vehicle exhaust emissions and travel delay rate (Pd) in Xining City, as shown in

Table 2 and

Figure 1.

According to

Figure 1, the relationship between vehicle emissions (y1) and travel delay rate (Pd) for the Xinning Road section (South to North) in Xining City is:

The relationship between vehicle emissions (y2) and travel delay rate (Pd) for Xinning Road (North to South) in Xining City is:

The calculation formula for travel delay rate Pd in Equations (2) and (3) is shown in Equation (4), where T is the average travel time. If the travel distance is fixed, the travel delay rate Pd can be equivalent to the average speed delay rate Ps, as shown in Equation (5):

Considering the maximum speed on Xinning Road in Xining City is 36.3 km/h for South to North and 35 km/h for North to South [

18], substituting the maximum speed and Equation (5) into Equations (2) and (3) respectively yields:

Based on the actual driving speed range, the speed range was determined to be from 12.5 km/h to 36.5 km/h. Emissions for South to North and North to South were calculated separately using Equations (6) and (7), and the average values were finally taken, with the results shown in

Table 3.

Based on the speed and average emission value data in

Table 3, the relationship between emission quantity and speed can be further obtained, as shown in Equation (8).

Equation (8) shows that as speed increases, the exhaust emissions per kilometer per vehicle exhibit a gradual decreasing trend. Therefore, traffic congestion significantly increases vehicle exhaust emissions to a certain extent.

2.3. Relationship Between Emissions and Saturation Degree

Substituting Equation (1) into Equation (8) yields the relationship between vehicle emissions and saturation degree, as shown in Equation (9).

Equation (9) indicates that vehicular exhaust emissions per kilometer are proportional to the saturation degree metric value. A higher saturation degree value indicates more congested road traffic, resulting in greater vehicular exhaust emissions.

3. Road Network Efficiency Considering Saturation Degree

3.1. Definition of Network Efficiency

In a network, the path efficiency between any two points can be defined as the reciprocal of their shortest path, as shown in the following equation.

Building upon the efficiency between two points, the efficiency of the entire network can be further defined, as shown in the following equation.

Where E is the efficiency of the overall network, and N is the total number of nodes in the entire network.

Improved Network Efficiency

In fact, the efficiency between any two nodes in the network is not only related to their distance but also to the congestion level of the road segments and nodes traversed along the path. The more severe the congestion level, the lower the passage efficiency between the two points. This paper considers the impact of node congestion level on efficiency and further improves Equation (10), yielding:

Where: α_k is the saturation degree of the k-th node, and t is the total number of nodes traversed along the shortest path from node i to node j. Furthermore, the formula for calculating the improved overall network efficiency is obtained as follows.

Equation (13) indicates that the improved overall network efficiency metric value is inversely proportional to the overall (or average) saturation degree value of the network. That is, the smaller the saturation degree value, the larger the improved network efficiency value, and consequently, the higher the network operational efficiency. Conversely, the larger the saturation degree value, the smaller the improved network efficiency value, and consequently, the lower the network operational efficiency.

4. Relationship Between Emissions and Network Efficiency

To facilitate the study of the relationship between vehicle emissions and network efficiency, based on the data in

Table 1, the operational state of urban road traffic is further classified into three levels: namely free flow, stable flow, and congested flow (the first two are categorized as unimpeded flow). Representative saturation degree values corresponding to these three operational states are taken as 0.2, 0.6, and 0.8, respectively, as shown in

Table 4.

To facilitate the study and comparison of the impact of different intersection cluster selections on road network congestion mitigation, the concept of Benchmark Improved Network Efficiency (E0) is introduced.

Definition: Benchmark Improved Network Efficiency (E0) refers to the improved network efficiency corresponding to the state where the saturation degree of all nodes in the network is set to a specific value.

Based on

Table 4 and the definition of Benchmark Improved Network Efficiency, it includes Free Flow Benchmark Improved Network Efficiency (E01), Unimpeded Flow Benchmark Improved Network Efficiency (E02), and Congested Flow Benchmark Improved Network Efficiency (E03).

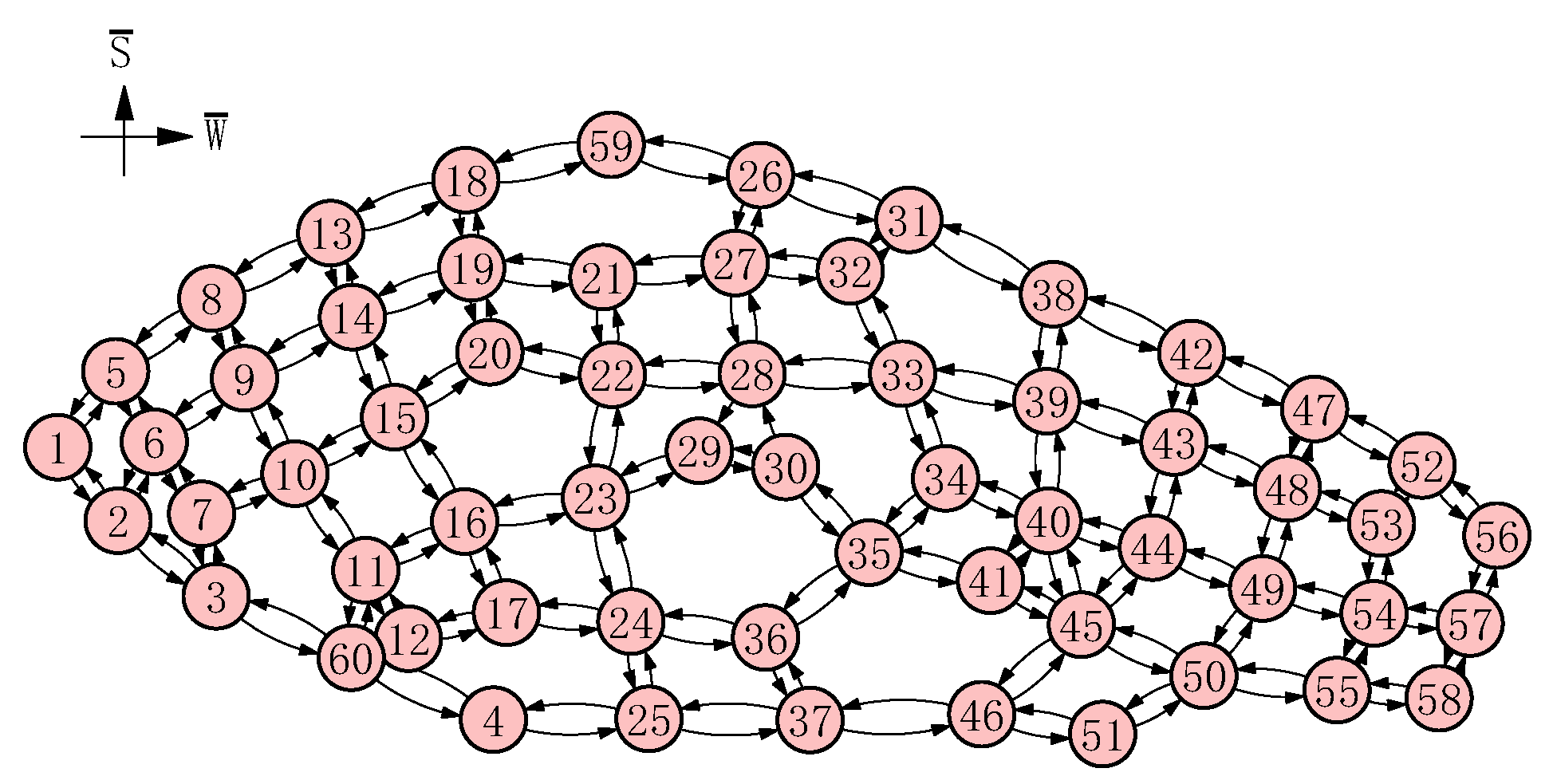

Taking the 60 road intersections in the urban core area of Xining City, Qinghai Province (road network structure topology shown in

Figure 2) as an example, Taking the 60 road intersections in the urban core area of Xining City, Qinghai Province (road network structure topology shown in

Figure 2) as an example.

Based on the correspondence between the representative saturation degrees (0.2, 0.6, 0.8) for the operational state classifications and the benchmark network efficiencies (0.1892, 0.0631, 0.0473), the relationship between saturation degree and network efficiency can be further derived, as shown in the following equation.

Substituting Equation (14) into Equation (9), the relationship between vehicle emissions and network efficiency can be further obtained as follows.

Equation (15) indicates that vehicular exhaust emissions exhibit an inverse relationship with the improved network efficiency. As the road traffic operational state shifts from congestion to smooth flow, for every 1-unit increase in the E’ value, the average exhaust emissions per vehicle per kilometer decrease by 3.976 kg.

5. Intersection Cluster Selection and Energy Conservation & Emission Reduction

To analyze the impact of intersection cluster selection schemes on changes in network efficiency and the effects of energy conservation and emission reduction, the experiment design and data analysis were conducted using the MATLAB software platform.

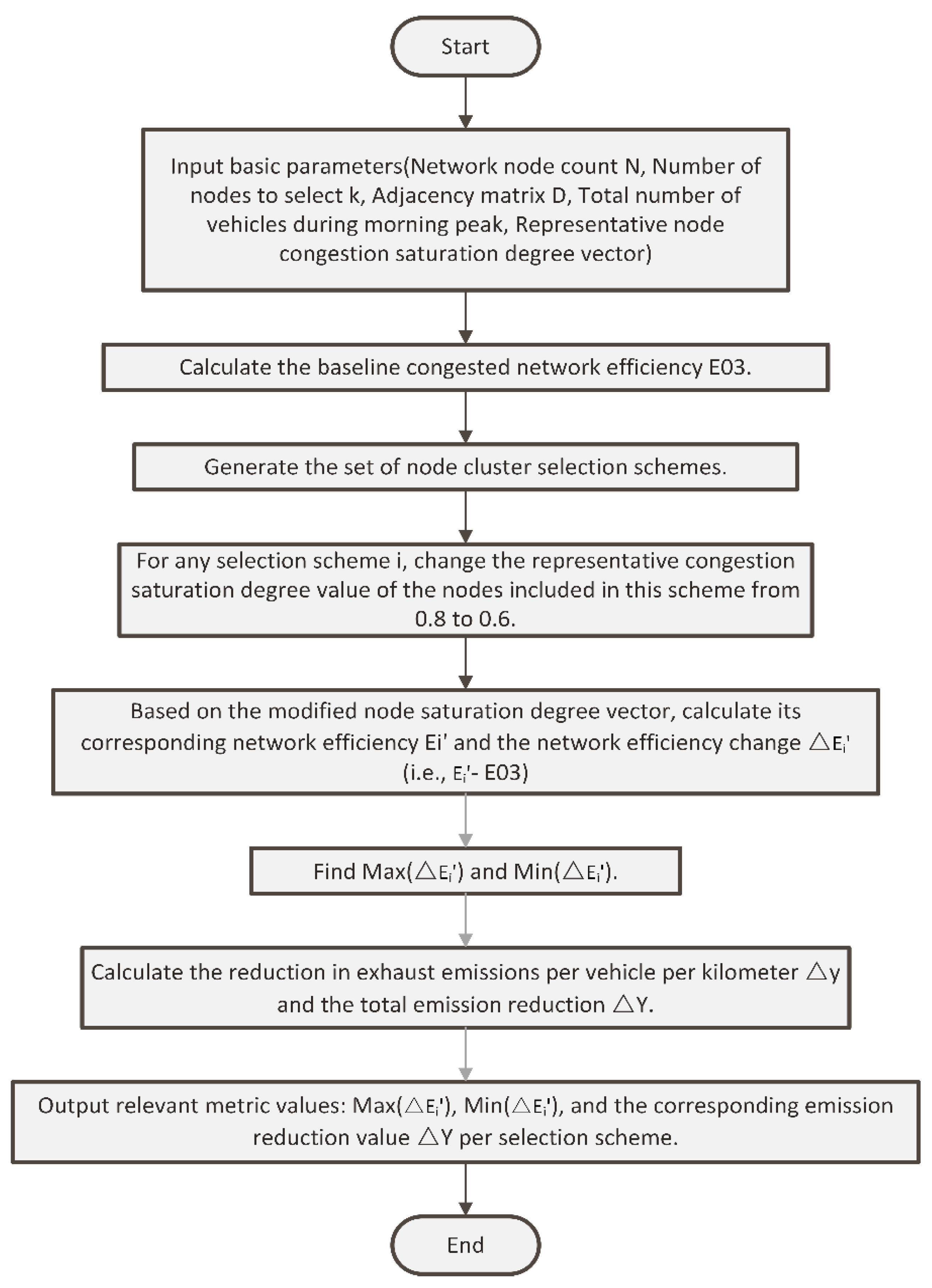

5.1. Experiment Process Design

The experimental subjects were the road network and its intersections in the core area of Xining City, Qinghai Province (topology structure shown in

Figure 2). The experiment process is shown in

Figure 3, mainly consisting of three parts: basic parameter input, calculation and analysis, and output of related metrics. Among the input basic parameters: The number of network nodes N is 60; the values in the representative node congestion saturation degree vector are all 0.8; the distance values in the adjacency matrix were obtained from surveys; the total number of vehicles during the morning peak was determined based on reference [19], taken as 414,500 (4.145×10⁵) vehicles; the average travel distance was determined based on reference [20], taken as 5.5 km.

5.2. Analysis of Experimental Results

5.2.1. Relationship Between Selection Schemes, Network Efficiency Change, and Emission Reduction

Due to computational power and time constraints, this experiment focused on

and

Taking the

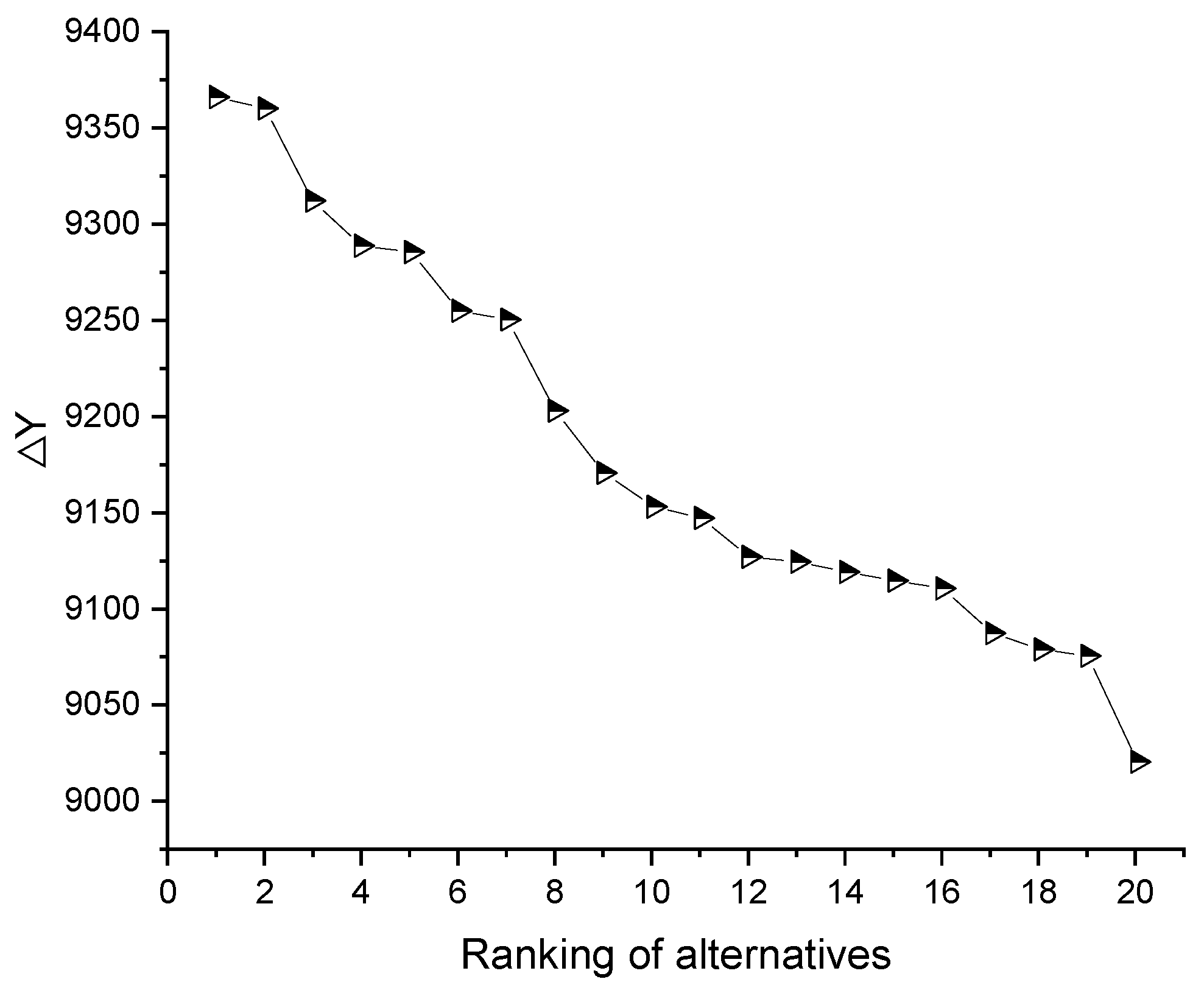

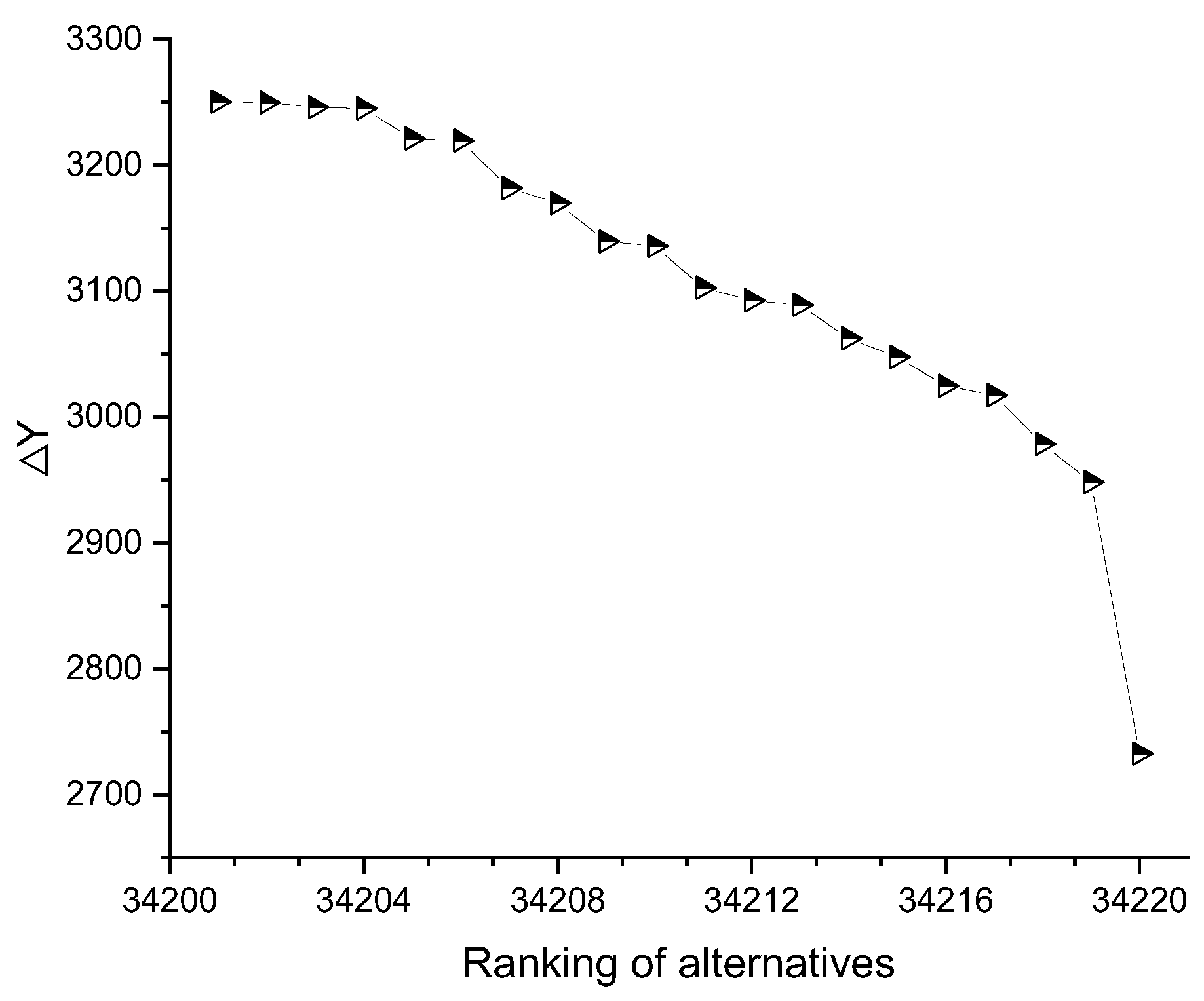

experiment as an example, its results were sorted in descending order based on the network efficiency change value

and the total morning peak emission reduction△Y. The top 20 and bottom 20 schemes were selected, with the results shown in

Table 5,

Figure 4, and

Figure 5.

As seen from

Table 5,

Figure 4, and

Figure 5, during the transition of the road traffic network from congestion to smooth flow, the corresponding total morning peak emission reduction △Y varies depending on the congestion mitigation node scheme. If sorted in descending order by the network efficiency change value

, the corresponding total morning peak emission reduction △Y also gradually decreases in a stepwise manner.

5.2.2. Differential Analysis of Selection Schemes and Emission Reduction

Based on the

and

experimental results, the data shown in

Table 6 were obtained.

Table 6 shows that during the morning peak, if 2 nodes are selected for congestion mitigation out of the 60 nodes in the core area, selecting nodes 40 and 50 reduces vehicular emissions by 4441 kg more than selecting nodes 1 and 56. If 3 nodes are selected for congestion mitigation out of the 60 nodes in the core area, selecting nodes 22, 28, and 33 reduces vehicular emissions by 6616 kg more than selecting nodes 1, 56, and 58. If the congestion mitigation period is extended from the morning peak to the evening peak, and further from daily to monthly (or even annually), this value would further increase. This demonstrates that in the process of urban road traffic congestion mitigation, the selection of node clusters is inextricably linked to energy conservation and emission reduction. Suboptimal selection of node clusters can lead to a significant increase in vehicular exhaust emissions. Conversely, optimal selection can achieve significant energy conservation and emission reduction effects.

6. Conclusion

To investigate and analyze the relationship between node cluster selection and energy conservation & emission reduction during urban road traffic congestion mitigation, the relationship between vehicle emissions and saturation degree was derived based on existing literature and research outcomes. Considering the impact of saturation degree on travel, the network efficiency evaluation metric was refined. A model linking vehicle emissions to network efficiency was established. A validation experiment was designed using the core road network of Xining City, Qinghai Province as an example. The results indicate that:

Vehicular exhaust emissions per kilometer are proportional to the saturation degree metric value. A higher saturation degree value indicates more congested road traffic, resulting in greater vehicular exhaust emissions.

The network efficiency metric value is inversely proportional to the overall (or average) saturation degree of the network. That is, a smaller saturation degree value corresponds to a larger network efficiency value and consequently higher network operational efficiency. Conversely, a larger saturation degree value corresponds to a smaller improved network efficiency value and consequently lower network operational efficiency.

Vehicular exhaust emissions exhibit an inverse relationship with network efficiency. As the road traffic operational state shifts from congestion to smooth flow, for every 1-unit increase in the network efficiency value, the average exhaust emissions per vehicle per kilometer decrease by 3.976 kg.

During the transition of the road traffic network from congestion to smooth flow, the corresponding total morning peak emission reduction varies depending on the congestion mitigation node scheme. If sorted in descending order by the network efficiency change value, the corresponding total morning peak emission reduction also gradually decreases in a stepwise manner.

According to the and experimental results, compared to the worst node cluster selection scheme, the optimal node cluster selection scheme can reduce vehicular emissions by 4441 kg and 6616 kg, respectively.

In the process of urban road traffic congestion mitigation, the selection of node clusters is inextricably linked to energy conservation and emission reduction. Suboptimal selection of node clusters can lead to a significant increase in vehicular exhaust emissions. Conversely, optimal selection can achieve significant energy conservation and emission reduction effects.

Due to computational and time constraints, this study focused on the and experiments. Future work will investigate the relationship between selection schemes for 4 or more node clusters and energy conservation & emission reduction effects by optimizing algorithms and enhancing computational power. Furthermore, the variation pattern of energy conservation and emission reduction effects with increasing number of node clusters will be analyzed. Additionally, the simulation of the traffic congestion mitigation process in this study was relatively simple. Future studies will consider incorporating other congestion mitigation simulation models that account for temporal and propagation effects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.F.; data curation, M.F. and W.X.; investigation, M.F.; methodology, M.F.; writing—original draft preparation, M.F.; writing—review and editing, W.X. and C.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

References

- Boeing, G.; Pilgram, C.; Lu, Y. Urban street network design and transport-related greenhouse gas emissions around the world. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 2024, 127, 103961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elassy, M.; Al-Hattab, M.; Takruri, M.; Badawi, S. Intelligent transportation systems for sustainable smart cities. Transportation Engineering 2024, 16, 100252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, TIAN. Study on the Stochastic delay at urban signalized Intersection; Chang’an University, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, J. Study on the identification of traffic status and the method for mining congestion propagation rule of intersections; Soochow University, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, L. Based on Vulnerability and Elastic Recoveryof the Reliability of Urban Road Network Traffic Safety Assessment Methods; Chongqing Jiaotong University, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, T.; Chen, K.; Li, F. Topologe analysis of urban rail transit network. Journal of Chang’an University (Natural Science Edition) 2018, 38, 97–106. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Z. Study on the Vulnerability of Road Network Traffic System Considering the Characteristics of Congestion Propagation; Chongqing Jiaotong University, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, B.; Zheng, C.X.; Tang, L.R.; et al. Critical nodes identification for vulnerability analysis of power communication networks. IET Communications 2020, 14, 703–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, N.; Cao, H.Q. Exploring the robustness of urban bus network: A case from Southern China. Chinese Journal of Physics 2020, 65, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Li, W.Y.; Yang, G. Traffic Network Reliability in Tourist Attractions Based on Node Importance. Journal of Transport Information and Safety 2019, 37, 128–137. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, Y.Y. Complex Network Property and Vulnerability of Urban Rail Transit Networks; Shanghai JiaoTong University, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, Y.Y.; Lu, J.; Chen, S.D.; et al. Vulnerability analysis of urban rail transit based on complex network theory: a case study of Shanghai Metro. Public Transport 2017, 9, 501–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.L.; Guo, X.D.; Dong, X. Importance identification method of complex network nodes based on betweenness and degree entropy. Journal of Lanzhou University of Technology 2020, 46, 111–115. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, Y.Y.; Lu, J.; Chen, S.D. Weighted Complex Network Analysis of Shanghai Rail Transit System. Discrete Dynamics in Nature & Society 2016, 2016, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q.; Zhu, R.H.; Zhao, X.Q. Calculation decoupling analysis scenario prediction of carbon emissions of transportation in China. Journal of Chang’an University (Natural Science Edition) 2014, 34, 77–83. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, S.Y.; Deng, J.F.; Ma, Z.F.; et al. Experimental study on road traffic state evaluation and emission correlation of plateau cities based on PEMS: A case study of Xining City. Journal of Qinghai Normal University (Natural Science) 2018, 34, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Z.F. Transportation Engineering Technology and Applications; Lanzhou University Press: Lanzhou, 2019; Volume 179. [Google Scholar]

- Beijing Urban Construction Design Development Group Co., Ltd. Xining City Urban Traffic Survey Report 2017; Beijing Urban Construction Design Development Group Co., Ltd.: Beijing, 2018; Volume 54. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).