Submitted:

09 January 2026

Posted:

09 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

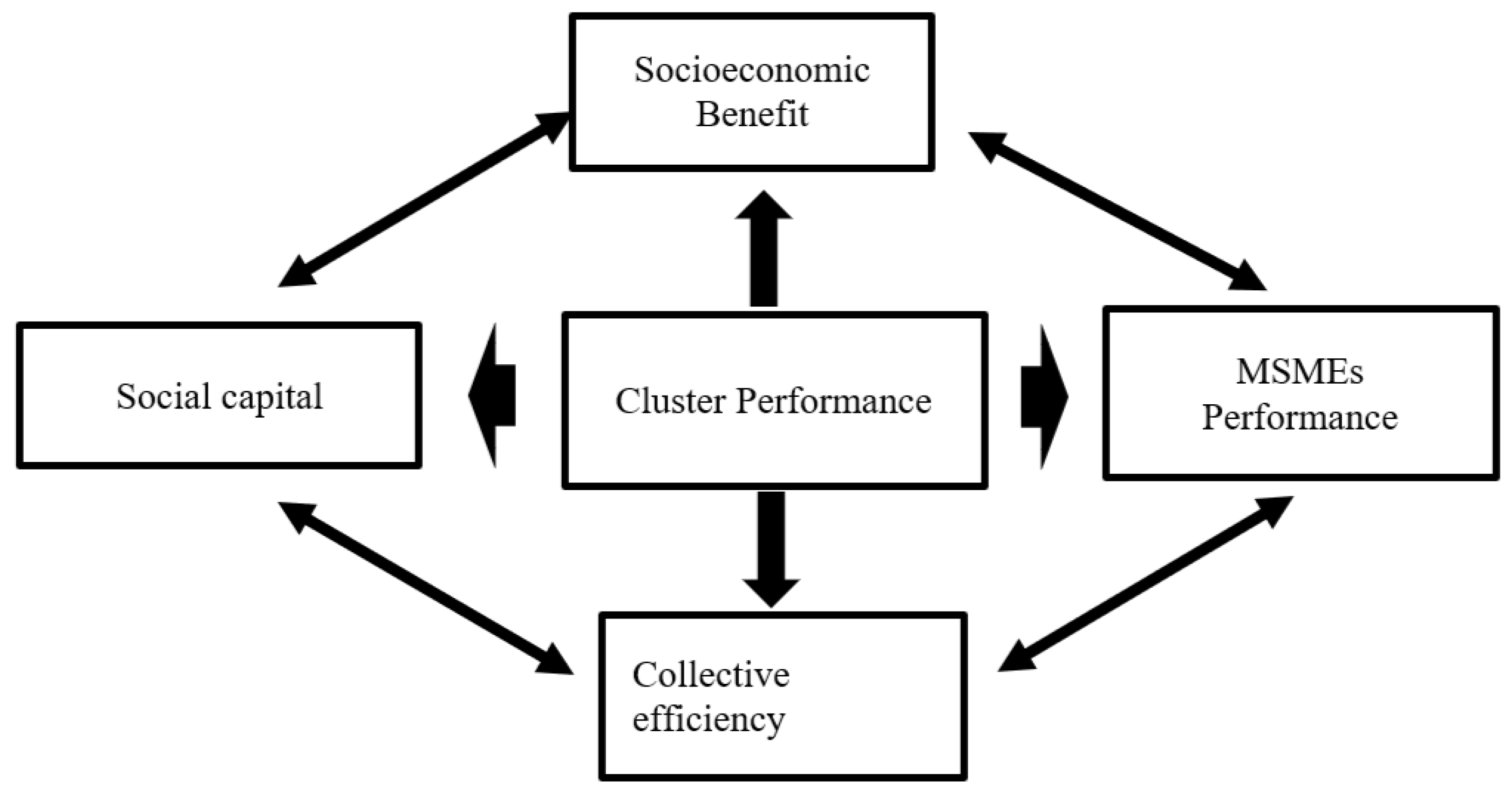

2. Literatur Review and Hypothesis

2.1. Literatur Review

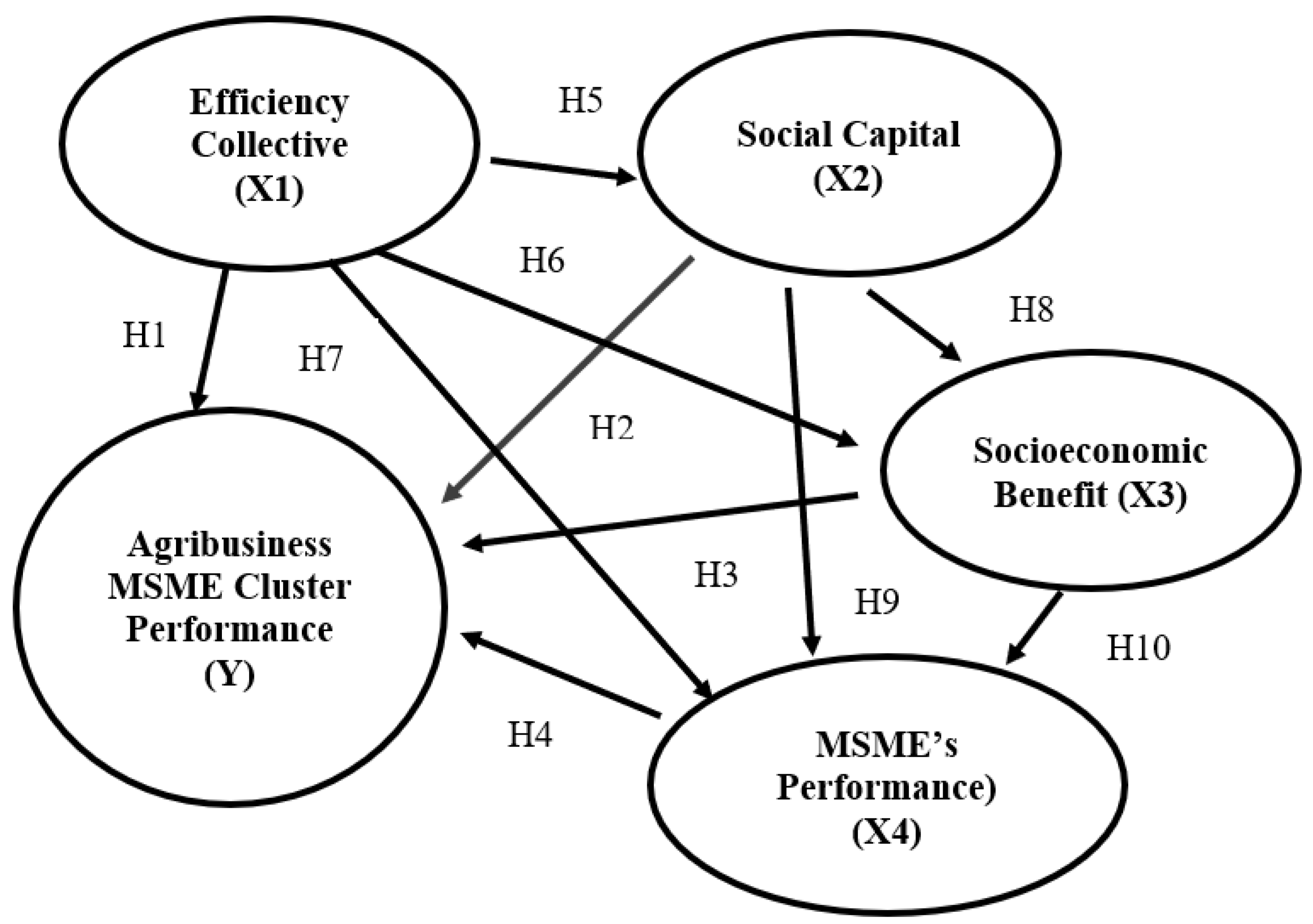

2.2. Hypothesis

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Variables and Indicators

3.2. Sampling and Data Collecting

Data Analysis Method

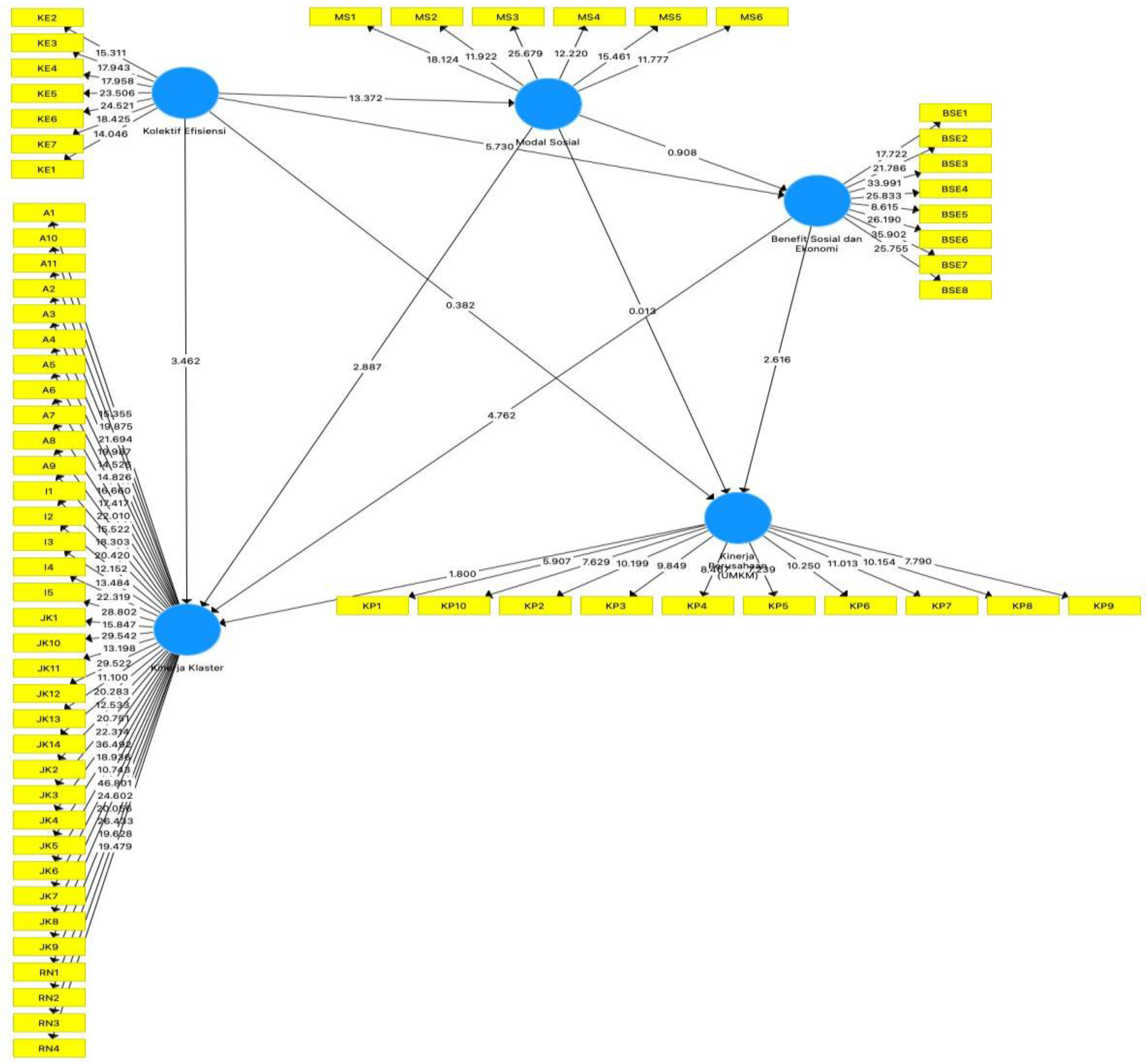

3.3. Measurement Model Evaluation (Outer Model)

3.3.1. Convergent Validity

3.3.2. Discriminant Validity

3.3.3. Reliability

3.4. Structural Model Evaluation (Inner Model)

3.4.1. R2 (R Square)

3.4.2. Q2 (Predictive Relevance)

3.4.3. F2 (Effect Size)

3.5. Hypothesis Testing

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Measurement Model Test

4.1.1. Discriminant Validity (Cross Loading) Result

| Socioeconomic Benefit | MSMEs Cluster Performance | MSMEs Performance | Efficiency Collective | Social Capital | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socioeconomic Benefit | |||||

| MSMEs Cluster Performance | 0,569 | ||||

| MSMEs Performance | 0,194 | 0,129 | |||

| Efficiency Collective | 0,684 | 0,649 | 0,112 | ||

| Social Capital | 0,539 | 0,596 | 0,162 | 0,826 |

| Socioeconomic Benefit | MSMEs Cluster Performance | MSMEs Performance | Efficiency Collective | Social Capital | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socioeconomic Benefit | 0,777 | ||||

| MSMEs Cluster Performance | 0,557 | 0,711 | |||

| MSMEs Performance | 0,197 | 0,005 | 0,779 | ||

| Efficiency Collective | 0,636 | 0,615 | 0,105 | 0,764 | |

| Social Capital | 0,487 | 0,547 | 0,083 | 0,705 | 0,726 |

4.1.2. Hypothesis Test Results

4.2. The Influence of Collective Efficiency on the Performance of Agribusiness MSME Clusters.

4.3. The Influence of Social Capital on the Performance of Agribusiness MSME Clusters

4.4. The Influence of Socioeconomic Benefits on the Performance of Agribusiness MSME Clusters

4.5. The Influence of MSME Performance on the Performance of Agribusiness MSME Clusters

4.6. The Effect of Collective Efficiency on Social Capital

4.7. The Effect of Collective Efficiency on Socioeconomic Benefits

4.8. The Influence of Collective Efficiency on MSME Performance

4.9. The Influence of Social Capital on Socioeconomic Benefits

4.10. The Influence of Social Capital on MSME Performance

4.11. The Influence of Socioeconomic Benefits on MSME Performance

5. Conclusions and Implications

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Implications

References

- Adi, R. K.; Harisudin, M.; Ferichani, M. Kajian Efektifitas Peran Klaster Pertanian Terpadu di Kabupaten Sukoharjo. In Proceeding Seminar Nasional Peningkatan Kapabilitas UMKM dalam Mewujudkan UMKM Naik Kelas sebenarnya; Irianto, H., Handayanta, E., Setyowati, N., Cahyadin, M., Eds.; UNS Press, 2016; pp. 93–111. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, P. S.; Kwon, S. W. Social capital: Prospects for a new concept. Academy of Management Review 2002, 27, 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Wilkins, S. Purposive sampling in qualitative research: a framework for the entire journey. Quality & Quantity 2025, 59, 1461–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamanda, D. T.; Kusmiati, E.; Shiddieq, D. F.; Roji, F. F. MSME clusterization using K-means clustering in Garut Regency, Indonesia. Review of Integrative Business and Economics Research 2023, 12, 199–211. [Google Scholar]

- Apriliyani, A.; Amalia, N. Analisis Hubungan Aspek Keuangan, Teknis dan Produksi, Pasar dan Pemasaran, serta Kebijakan Pemerintah dengan Kinerja Usaha Mikro Kecil dan Menengah (Studi pada UMKM Klaster Keramik di Desa Melikan, Kecamatan Wedi, Kabupaten Klaten. 2019. Available online: http://etd.repository.ugm.ac.id/.

- Bappeda dan Litbang Kabupaten Wonogiri. Laporan Perkembangan Klaster UMKM Kabupaten Wonogiri Tahun 2022. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Becattini, G. The Marshallian industrial district as a socio-economic notion. In Industrial districts and inter-firm co-operation in Italy; Pyke, F., Becattini, G., Sengenberger, W., Eds.; International Labour Organization, 1990; pp. 37–51. [Google Scholar]

- Bisht, H. S.; Singh, D. Challenges faced by micro, small, and medium enterprises: a systematic review. World Review of Science, Technology and Sustainable Development 2020, 16, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cainelli, G.; Iacobucci, D. Agglomeration, related variety, and firm performance. Journal of Economic Geography 2012, 12, 307–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, S.; Greenwood, M.; Prior, S.; Shearer, T.; Walkem, K.; Young, S.; Bywaters, D.; Walker, K. Purposive sampling: complex or simple? Research case examples. Journal of Research in Nursing 2020, 25, 652–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpinetti, C. R.; Luiz; Galdámez, C.; EdwinVladimir; Cecilio Gerolamo, M. A measurement system for managing performance of industrial clusters. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management 2008, 57, 405–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpinetti, L. C. R.; Oiko, O. T. Development and application of a benchmarking information system in clusters of SMEs. Benchmarking: An International Journal 2008, 15, 292–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaminade, C.; Vang, J. Globalisation of knowledge production and regional innovation policy: Supporting specialized hubs in the Bangalore software industry. Research policy 2008, 37, 1684–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W. W. Partial least squares is to LISREL as principal components analysis is to standard factor analysis; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, D.; Prusak, L. Good Company: How Social Capital Makes Organizations Work; Havard Business School Press, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J. S. Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology 1988, 94, S95–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, C. J.; Clark, K. D. Strategic human resource practices, top management team social networks, and firm performance: The role of human resource practices in creating organizational competitive advantage. Academy of management Journal 2003, 46, 740–751. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, M.; Porter, M. E.; Stern, S. Clusters, convergence, and economic performance. Research Policy 2014, 43, 1785–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, M.; Porter, M. E.; Stern, S. Defining clusters of related industries. Journal of Economic Geography 2016, 16, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmadjaya, J. E.; Purnama, J.; Permana, T. Pasporumkm Online Platform Development For Self-Guided Halal Assurance System Preparation On The Case Of Smes In The Food Sector. Proceedings Of The 2022 International Conference On Engineering And Information Technology For Sustainable Industry, 2022, September; pp. Pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Dornberger, U.; Utama, I. B. Collective Efficiency and Enterprise Performance in Different Stages of the Cluster Life Cycle. Presentation in The Cluster Conference, Lyon, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Easmon, R. B.; Kastner, A. N. A.; Blankson, C.; Mahmoud, M. A. Social capital and export performance of SMEs in Ghana: the role of firm capabilities. African Journal of Economic and Management Studies 2019, 10, 262–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edeh, E.; Lo, W.-J.; Khojasteh, J. Review of Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook. In Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal; 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisol; Aliami, S.; Anas, M. Pathway of building SMEs performance in cluster through innovation capability. Economic Development Analysis Journal 2022, 11, 140–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feser, E. J.; Bergman, E. M. National industry cluster templates: A framework for applied regional cluster analysis. Regional Studies 2010, 44, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feser, E. J.; Sweeney, S. H. A Test for the Coincident Economic and Spatial Clustering of Business Enterprises. Journal of Geographical Systems 2000, 2, 349–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerke, A. SME upgrading in emerging market clusters: The case of Taiwan’s bicycle industry. Journal of Business Research 2023, 164, 113967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, E. Network dynamics in regional clusters. Journal of Economic Geography 2013, 13, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, E.; Pietrobelli, C.; Rabellotti, R. Upgrading in global value chains: Lessons from Latin American clusters. World Development 2005, 33, 549–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, L. G. d. A.; Blanchet, P.; Cimon, Y. Collaboration among small and medium-sized enterprises as part of internationalization. Administrative Sciences 2021, 11, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Kumar Singh, R. Managing resilience of micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) during COVID-19: analysis of barriers. Benchmarking: An International Journal 2023, 30, 2062–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, D. P.; Widodo, S.; Purnamasari, I.; Handayani, P. M. MSME Cluster Development Strategy Become a Leading Product Tegalrejo Jatijajar Village, Bergas District, Semarang Regency Based on Collaborative. KnE Social Sciences 2022, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V. G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. European Business Review 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayat, A. Menyusun Instrumen Penelitian & Uji Validitas-Reabilitas, 1st ed.; Health Books Publishing, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, D. D. The Role of Social Capital and Shared Leadership in the Digital Transformation and Firm Performance. SAGE Open 2025, 15, 21582440251347340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoetoro, A. The dynamics of performance improvement among SMEs clusters in East Java. In Proceedings of the 23rd Asian Forum of Business Education (AFBE 2019), 2020; Atlantis Press; pp. 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, J.; Schmitz, H. How does insertion in global value chains affect upgrading in industrial clusters? Regional Studies 2002, 36, 1017–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indreswari, R.; Wijianto, A.; Yunindanova, M. B.; Apriyanto, D.; Agustina, A.; Adi, R. K. Model Pengembangan Agribisnis Pertanian Terpadu dengan Pendekatan Klaster Pertanian Terpadu di Kabupaten Sukoharjo, Jawa Tengah, Indonesia. Agro Bali: Agricultural Journal 2021, 5, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khomah, I.; Setyowati, N.; Harisudin, M.; Adi, R. K.; Qonita, A. The factors contributing to the sustainability of agribusiness MSMEs in Sukoharjo Regency during the Covid-19 pandemic. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 2021, April; IOP Publishing; Vol. 746, p. 012013. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, N.; Shim, C. Social capital, knowledge sharing and innovation of small- and medium-sized enterprises in a tourism cluster. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 2018, 30, 2417–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, B.; Dhingra, A. Role of Agribusiness Management in Food Industry. In Agribusiness Management; Routledge, 2024; pp. 127–137. [Google Scholar]

- Lema, R.; Vang, J. Collective efficiency: a prerequisite for cluster development? World review of entrepreneurship, management and Sustainable Development 2018, 14, 348–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lis, A. M.; Rozkwitalska, M.; Lis, A. Sustainability objectives and collaboration lifecycle in cluster organizations. Quality & Quantity 2023, 57, 4049–4068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubis, F. S.; Rahima, A. P.; Isnaini, M.; Umam, H.; Industri, J. T.; Sains, F.; Sultan, U. I. N.; Kasim, S.; Hr, J.; No, S.; Baru, S. Analisis Kepuasan Pelanggan dengan Metode Servqual dan Pendekatan Structural Equation Modelling ( SEM ) pada Perusahaan Jasa Pengiriman Barang di Wilayah Kota Pekanbaru. Jurnal Sains Dan Teknologi Industri 2019, 16, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Griffith, D. A.; Liu, S. S.; Shi, Y. Z. The effects of customer relationships and social capital on firm performance: A Chinese business illustration. Journal of International Marketing 2004, 12, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manhas, P. S.; Manrai, A. K.; Manrai, L. A.; Ramjit. Role of Structural Wquation Modelling in Theory Testing and Development. Quantitative Modelling in Marketing and Management 2012, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.; Sunley, P. Conceptualizing cluster evolution: Beyond the life cycle model? Regional Studies 2011, 45, 1299–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, M. A.; Thurasamy, R.; Ting, H.; Cheah, J. H. Purposive Sampling: a Review and Guidelines for Quantitative Research. Journal of Applied Structural Equation Modeling 2025, 9, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monni, S.; Palumbo, F.; Tvaronavičienė, M. Cluster performance: an attempt to evaluate the Lithuanian case. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monni, S.; Palumbo, F.; Tvaronavičienė, M. Cluster performance: A literature review. Journal of Business Economics and Management 2017, 18, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musyaffi, A.; Khairunnisa, H.; Respati, D. Konsep Dasar Structural Equation Model-Partial Least Square (SEM-PLS) Menggunakan SMART PLS; Pascal Books, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Nahapiet, J.; Ghoshal, S. Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Academy of Management Review 1998, 23, 242–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parto, S. Innovation and economic activity: an institutional analysis of the role of clusters in industrializing economies. Journal of economic issues 2008, 42, 1005–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M. E. Clusters and the new economics of competition. Harvard Business Review 1998, 76, 77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Purnomo, R. A.; Sarungu, J. J.; Samudro, B. R.; Mulyaningsih, T. The dynamics of technology adoption readiness of micro, small, and medium enterprises and affecting characteristics: the experience from Indonesia. REVIEW OF INTERNATIONAL GEOGRAPHICAL EDUCATION 2021, 11, 834–854. [Google Scholar]

- Purwanto, A.; Sudargini, Y. Partial Least Squares Structural Squation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Analysis for Social and Management Research: A Literature Review. Journal of Industrial Engineering & Management Research 2021, 2, 114–123. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R. D. Making democracy work: Civic traditions in modern Italy; Princeton University Press, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R. D. Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community; Simon & Schuster, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rachmawati, R.; Widowati, W. Analisis Pendanaan Usaha Dan Kinerja Usaha UMKM Batik Pekalongan. Prosiding Pendidikan Teknik Boga … 2021, 16, 6. Available online: https://journal.uny.ac.id/index.php/ptbb/article/view/44546.

- Ramez, A. A. M.; Ateik, A. H. A. M.; Raymond, S. A. Clusteriing Activities on The Performance of Small and Medium Scales Enterprises in Nigeria. Arabian Journal of Business and Management Review (Kuwait Chapter) 2022, 11, 159–166. [Google Scholar]

- Rocha, H.; Kunc, M.; Audretsch, D. B. Clusters, economic performance, and social cohesion: a system dynamics approach. Regional Studies 2020, 54, 1098–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royo-Vela, M.; Amezquita Salazar, J. C.; Puig Blanco, F. Market orientation in service clusters and its effect on the marketing performance of SMEs. European Journal of Management and Business Economics 2022, 31, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C. M.; Hair, J. F. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling; 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, H. Collective efficiency: Growth path for small-scale industry. Journal of Development Studies 1995, 31, 529–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, H. Collective efficiency: Growth path for small-scale industry. The Journal of Development Studies 1995, 31, 529–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, H. Collective efficiency and increasing returns. Cambridge Journal of Economics 1999, 23, 465–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.; Lee, J.; Jung, S.; Park, S. The role of creating shared value and entrepreneurial orientation in generating social and economic benefits: Evidence from Korean SMEs. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinvasan, R.; Lohith, C. P.; Kadadevaramth, R. S.; Shrisha, S. Strategic Marketing and Innovation Performance of Indian MSMEs. 2015 Portland International Conference on Management of Engineering and Technology (PICMET), 2015, August; IEEE; pp. 127–133. [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyono. Metode Penelitian Kuantitatif; Alfabeta, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Susanto, A. Modal sosial dan kinerja UMKM dalam klaster industri. Jurnal Ekonomi dan Bisnis Indonesia 2021, 36, 123–137. [Google Scholar]

- Susanto, D. A. Sme Inter-Clustering Linkage of East Java: Among Business Strategy and Cooperatives. Journal of Developing Economies 2021, 6, 174–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temouri, Y. The cluster scoreboard: measuring the performance of local business clusters in the knowledge economy. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson, P. R.; Fai, F. M. The nature of SME co-operation and innovation: A multi-scalar and multi-dimensional analysis. International Journal of Production Economics 2013, 141, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tongco, M. D. C. Purposive Sampling as a Tool for Informant Selection. Ethnobotany Research & Applications 2007, 5, 147–158. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, N. G.; Trung, N. T.; Long, N. T.; Dat, N. H. A. Social capital and entrepreneurial performance of SMEs: the mediating role of access to entrepreneurial resources. In Management Systems in Production Engineering; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Tsang, K. K.; Liu, D.; Hong, Y. Challenges and Opportunities in Qualitative Research. In Challenges and Opportunities in Qualitative Research: Sharing Young Scholars’ Experiences; Tsang, K. K., Liu, D., Hong, Y., Eds.; Springer Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiser, E. B. Structural Equation Modeling in Personality Research. In The Wiley Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences Vol. II; Wiley, 2020; pp. 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Techniques Using SmartPLS. Marketing Bulletin 2013, 24, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Woolcock, M. The place of social capital in understanding social and economic outcomes. Canadian Journal of Policy Research 2001, 2, 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Woolcock, M.; Narayan, D. Social capital: Implications for development theory, research, and policy. World Bank Research Observer 2000, 15, 225–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wudu, A.; Singh, K.; Kassahun, S. Industry clusters and firm performance: Evidence from the leather product industry in Addis Ababa. Heliyon 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulandari, C.; Agustono; Adi, R. K. Analisis Faktor-Faktor yang Mempengaruhi Kinerja UMKM pada Klaster UMKM Agribisnis di Kabupaten Purbalingga. Agrista 2023, 11, 23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Yunus, M.; Sari, I. A.; Wahyuhastuti, N. Strategi Pengembangan UMKM di Provinsi Jawa Scorecard. Kajian Ekonomi & Keuangan 2021, 5, 2018–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusup, F. Uji Validitas dan Reliabilitas Instrumen Penelitian Kuantitatif. Jurnal Tarbiyah: Jurnal Ilmiah Kependidikan 2018, 7, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Liang, Y.; Tu, H. How do clusters drive firm performance in the regional innovation system? A causal complexity analysis in Chinese strategic emerging industries. Systems 2023, 11, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zhang, W.; Li, X. Social and economic benefits and firm performance in SME clusters. Small Business Economics 2023, 60, 987–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zizka, M.; Stichhauerova, E. Effect of cluster initiatives and natural clusters on business performance. Competitiveness Review: An International Business Journal 2023, 33, 1118–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No | Description | Unit | Year | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |||

| 1 | Number of MSME | unit | 133.679 | 143.738 | 161.458 | 167.391 | 173.431 | 177.256 |

| Non Agriculture | unit | 45.963 | 49.328 | 55.275 | 57.527 | 60.449 | 63.311 | |

| Agriculture | unit | 22.329 | 23.956 | 26.833 | 27.653 | 28.284 | 28.357 | |

| Trading | unit | 49.198 | 53.063 | 59.836 | 62.083 | 63.965 | 64.707 | |

| Services | unit | 16.189 | 17.391 | 19.514 | 20.128 | 20.733 | 20.881 | |

| 2 | Labor | orang | 918.455 | 1.043.320 | 1.312.400 | 1.298.007 | 1.311.015 | 1.320.953 |

| 3 | Asset | Rp. Milyar | 26.249 | 29.824 | 38.158 | 38.353 | 38.521 | 38.719 |

| 4 | Omzet | Rp. Milyar | 49.247 | 55.691 | 67.550 | 67.087 | 68.242 | 68.387 |

| No | Variable | Indicator | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Agribusiness MSME Cluster Performance | Land access Water, electricity, and communication accessibility Research and development accessibility Transportation accessibility Downstreaming achievement Number of MSMEs Number of processing industries Number of supporting material suppliers Number of raw material suppliers Existence of associations Existence of related service industries Existence of educational institutions Existence of financing institutions Cluster cooperation Cooperation between processing industries Industry association cooperation Cooperation with related service industries Cooperation with educational institutions Cooperation with training institutions Cooperation with financing institutions Cooperation with research institutions Marketing cooperation Cooperation with supporting raw material suppliers Cooperation with primary raw material suppliers Availability of technological equipment Leading clusters Product quality Technology utilization Role of working groups in clusters Role of government in clusters Role of government in clusters The role of the private sector in clusters |

Model Carpinetti, Feser Approach |

| 2 | Social Capital | Cluster Activities Honesty Completeness of Technology Components Commitment Coordination Public perception |

(Carpinetti, 2008) Handayani et al (2016) (Cohen dan Prusak, 2001) |

| 3 | Socioeconomic Benefit | Brand Image Product Quality Workforce Training Services Industrial Waste Management Labor Absorption Workforce Rewards Working atmosphere |

|

| 4 | Collective Efficiency | Existence of research institutions Local government policies Efficiency collaboration Geographical location |

(Carpinetti, 2008) Handayani et al (2016) (Schmitz, 1995) |

|

Establishing good relationships with suppliers Cluster growth and development |

|||

| 5 | MSME’s Performance | Resource Utilization Product Development Competition Profit Growth Capital Growth Market Growth Labor Force Growth Sales Growth Facilities and Infrastructure Tingkat komplain |

(Carpinetti, 2008) Handayani et al (2016) |

| Location | Number of Sample |

|---|---|

| Pekalongan Regency | 40 |

| Pati Regency | 42 |

| Magelang City | 32 |

| Purbalingga Regency | 39 |

| Rembang Regency | 32 |

| Demak Regency | 36 |

| Sukoharjo Regency | 30 |

| Total | 251 |

| Cronbach's Alpha | Composite Reliability | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Socioeconomic Benefit | 0,906 | 0,924 | 0,604 |

| MSMEs Cluster Performance | 0,970 | 0,972 | 0,505 |

| MSMEs Performance | 0,928 | 0,938 | 0,607 |

| Efficiency Collective | 0,880 | 0,907 | 0,583 |

| Social Capital | 0,818 | 0,869 | 0,527 |

| Socioeconomic Benefit | MSMEs Cluster Performance | MSMEs Performance | Efficiency Collective | Social Capital | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 0,662 | ||||

| A10 | 0,711 | ||||

| A11 | 0,697 | ||||

| A2 | 0,656 | ||||

| A3 | 0,637 | ||||

| A4 | 0,618 | ||||

| A5 | 0,692 | ||||

| A6 | 0,693 | ||||

| A7 | 0,707 | ||||

| A8 | 0,666 | ||||

| A9 | 0,693 | ||||

| BSE1 | 0,744 | ||||

| BSE2 | 0,779 | ||||

| BSE3 | 0,808 | ||||

| BSE4 | 0,803 | ||||

| BSE5 | 0,616 | ||||

| BSE6 | 0,776 | ||||

| BSE7 | 0,842 | ||||

| BSE8 | 0,829 | ||||

| I1 | 0,776 | ||||

| I2 | 0,609 | ||||

| I3 | 0,682 | ||||

| I4 | 0,755 | ||||

| I5 | 0,775 | ||||

| JK1 | 0,729 | ||||

| JK10 | 0,782 | ||||

| JK11 | 0,705 | ||||

| JK12 | 0,810 | ||||

| JK13 | 0,600 | ||||

| JK14 | 0,732 | ||||

| JK1 | 0,626 | ||||

| JK3 | 0,719 | ||||

| JK4 | 0,685 | ||||

| JK5 | 0,780 | ||||

| JK6 | 0,744 | ||||

| JK7 | 0,609 | ||||

| JK8 | 0,836 | ||||

| JK9 | 0,765 | ||||

| KE2 | 0,671 | ||||

| KE3 | 0,762 | ||||

| KE4 | 0,721 | ||||

| KE5 | 0,832 | ||||

| KE6 | 0,832 | ||||

| KE7 | 0,766 | ||||

| KP1 | 0,614 | ||||

| KP10 | 0,621 | ||||

| KP2 | 0,848 | ||||

| KP3 | 0,828 | ||||

| KP4 | 0,808 | ||||

| KP5 | 0,748 | ||||

| KP6 | 0,849 | ||||

| KP7 | 0,903 | ||||

| KP8 | 0,830 | ||||

| KP9 | 0,679 | ||||

| MS1 | 0,789 | ||||

| MS2 | 0,742 | ||||

| MS3 | 0,749 | ||||

| MS4 | 0,755 | ||||

| MS5 | 0,617 | ||||

| MS6 | 0,691 | ||||

| RN1 | 0,662 | ||||

| RN2 | 0,773 | ||||

| RN3 | 0,728 | ||||

| RN4 | 0,764 | ||||

| KE1 | 0,748 |

| Original Sample (O) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | P-Values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Socioeconomic Benefit -> MSME Cluster Performance | 0,286 | 4,762 | 0,000 |

| Socioeconomic Benefit -> MSME’s Performance | 0,218 | 2,616 | 0,009 |

| MSME’s Performance -> MSME Cluster Performance | -0,100 | 1,800 | 0,072 |

| Efficiency collective -> Benefit Sosial dan Ekonomi | 0,582 | 5,730 | 0,000 |

| Efficiency collective -> MSME Cluster Performance | 0,298 | 3,462 | 0,001 |

| Efficiency collective -> MSME’s Performance | -0,035 | 0,382 | 0,703 |

| Efficiency collective -> Social capital | 0,705 | 13,372 | 0,000 |

| Social capital -> Socioeconomic Benefit | 0,077 | 0,908 | 0,364 |

| Social capital -> MSME Cluster Performance | 0,206 | 2,887 | 0,004 |

| Social capital -> MSME’s Performance | 0,001 | 0,013 | 0,990 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).