1. Introduction

Pine wilt disease (PWD), is a systemic infectious disease caused by

Bursaphelenchus xylophilus in

Pinus L. and some other coniferous species [

1]. PWD in North America, but they did not cause widespread death of native pine trees in their native habitat. However, after being first discovered and reported in Japan in the 20th century, PWD rapidly spread globally and caused significant damage, severely affecting coniferous forest resources in Asia and Europe to date [

2,

3], attracting widespread attention and high priority from countries around the world [

4]. Since China first detected PWD in Nanjing in 1982 [

5], the disease has now formed 577 epidemic areas in 18 provinces (autonomous regions) of China, resulting in enormous economic and ecological losses.

PWD is transmitted by pathogen-carrying vector insects feeding on healthy host plants [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11], often leading to the blockage of pine conduction tissues, manifested as yellowing and browning of needles, reduced resin secretion, and ultimately causing the wilting and death of pine trees [

12]. In China,

Monochamus alternatus and

M. saltuarius have been identified as vector insects of PWD [

13].

Current research on PWD is mainly divided into two categories: control methods and pathogenic mechanisms [

1], among which prediction and forecasting are important components of control studies. MaxEnt model quantifies species occurrence probabilities using specific algorithms by combining historical distribution points of species with environmental variables [

14]. Due to its operational convenience and high prediction accuracy [

15], it has been widely applied in predicting potential occurrence areas of PWD. Gexi Xu et al. (2023) used the MaxEnt model to predict potential occurrence areas of PWD in Lixian County (a non-infected area), providing important support for subsequent control efforts [

5]. Nuermaimaitijiang Aierken et al. (2024) utilized ensemble species distribution models (including MaxEnt model) to predict the potential distribution of PWD globally from 2050 to 2080 [

16]. Han Yangyang et al. and Liu Xiaomei et al. (2017), as well as Zhuoqing Hao et al. (2022), also employed the MaxEnt model to predict potential distribution of PWD across China, Chongqing, and Yichang City [

17,

18,

19], demonstrating the flexibility of this model in spatiotemporal scale applications for PWD prediction. However, MaxEnt model still has limitations: difficulties in obtaining precise species distribution points and scarcity of large-scale impact factor data, all of which may constrain the accuracy of predicting PWD occurrence areas [

5,

16].

Xinjiang is located in the northwest of China, with a unique topography of "three mountains flanking two basins." The Tianshan Mountains, Altai Mountains, and Kunlun Mountains are home to abundant coniferous forest resources [

20], which play an irreplaceable role in water conservation and soil protection in Xinjiang. Among these, the coniferous forests in the Tianshan and Altai Mountains have been classified as moderately susceptible and highly susceptible, respectively, in previous studies [

21]. Additionally,

M saltuarius is distributed in both the Tianshan and Altai Mountains of Xinjiang [

22]. Relevant studies indicate that

M saltuarius is the primary vector for the spread of PWD in northern China [

23,

24]. If PWD were to invade, it would rapidly spread through

M saltuarius at the entry point, ultimately leading to widespread death of coniferous trees in Xinjiang. In 2021, The China National Forestry and Grassland Administration first announced the presence of PWD in Gansu Province, a neighboring province of Xinjiang. However, as of now, there have been no reports of PWD invasion or damage in Xinjiang (

http://www.forestry.gov.cn). Nevertheless, PWD remains a serious threat to Xinjiang's economic and ecological security [

6]. Whether Xinjiang will experience PWD has drawn attention from local forestry authorities and relevant departments.

As one of the regions in China currently not invaded by PWD, Xinjiang has always faced the risk of invasion. In addition to natural factors, activities such as the construction of the "Silk Road", increasingly frequent domestic and foreign trade, and the rapid development of Xinjiang's tourism have increased the flow of people and goods in Xinjiang, greatly increasing the possibility of PWD being introduced into Xinjiang. Considering the strategic significance of coniferous forests in Xinjiang for water conservation and soil and water conservation, as well as the devastating damage caused by PWD to coniferous forests, it is imperative to predict potential areas for PWD in Xinjiang. However, as of now, there are still few research reports on the prediction of PWD in Xinjiang.

To address the shortcomings in predicting potential occurrence areas of PWD in Xinjiang, explore its transmission mechanisms, and analyze high-risk areas, this study combines Xinjiang's unique conditions, considering factors such as climate, human influence, vector insect activity, and distance to Grade A scenic spots. Based on two spatial scales—China (prediction of potential transmission areas for PWD) and Xinjiang (prediction of potential suitable habitats for M saltuarius)—the study predicts current potential occurrence areas of PWD in Xinjiang. The aim is to clarify potential occurrence areas, analyze transmission routes, and identify high-risk regions. This research contributes to understanding the transmission mechanisms of PWD and provides scientific basis and references for local forestry and relevant departments to formulate prevention strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of the Study Area

Xinjiang is located in the heart of Asia, in the northwest of China (N 34.25 ~49.17, E 73.33 ~96.42) (

Figure 1). With a land border of approximately 5,600 km, it borders 8 countries and covers a total area of about 1.66 million km² (the largest provincial-level administrative region in China with the most neighboring countries). It serves as a key hub for China's contemporary "Silk Road". Xinjiang features a unique terrain described as "three mountains flanking two basins", with a forested area of about 83,300 km² (including the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps), a forest coverage rate of 5.05%, and a forest stock volume of 445 million m³, making its ecological environment relatively fragile. Among these, the Altai Mountains, Tianshan Mountains, and Kunlun Mountains are rich in coniferous forest resources, accounting for over 97% of Xinjiang's total timber stock volume (

http://lcj.xinjiang.gov.cn).

The coniferous forests of the Altai Mountains are dominated by

Larix sibirica Ledeb.,

Picea obovata Ledeb.,

Abies sibirica Korsh., and

Pinus sylvestris (Loud.) Mayr. The Tianshan Mountains are primarily covered by

Picea schrenkiana var. tianschanica (Rupr.) W.C.Cheng & S.H.Fu, with

L. sibirica Ledeb. also found in the eastern Tianshan. The Kunlun Mountains are home to

Juniperus centrasiatica Kom.,

J. jarkendensis Kom., and

J. pseudosabina var. turkestanica [

20]. The coniferous forests in Xinjiang are mostly natural forests, which hold significant ecological and economic value not only in Xinjiang but also in China.

2.2. Presence Data

2.2.1. Acquisition of Distribution Sites for PWD

The China National Forestry and Grassland Administration undertakes functions such as disaster early warning, guiding precise disaster prevention and control, and protecting and maintaining ecological balance. Since 1990, China has launched the construction project of the forest pest and rodent damage prediction and reporting network; in 2003, the State Forestry Administration further carried out the census of harmful organisms and established a more comprehensive database of forestry pests. The distribution information of PWD in this article is sourced from the disaster-affected counties and districts published by The China National Forestry and Grassland Administration over the years (

http://www.forestry.gov.cn).

According to the model requirements, each affected county was converted into coordinate point data, and the coordinate points were adjusted to the corresponding small-scale coniferous forest plots within the county (the small-scale coniferous forest plot data was generated by extracting coniferous forest data from the China vegetation distribution map). Ultimately, 685 distribution sites were obtained (

Figure 2) [

16]. Compared with the method that uses the county centroid as the distribution point, this method can effectively reduce model uncertainty [

25,

26].

2.2.2. Acquisition of Vector Insect Distribution Sites

The national vector insect data were sourced from The China National Forestry and Grassland Administration, the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (

https://www.gbif.org/), the National Animal Collection Resource Center (

http://museum.ioz.ac.cn/), the Field Identification Manual for Forest Pests in Xinjiang, and published literature [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33].

Since M. saltuarius primarily inhabits natural forest areas in Xinjiang, where frequent climate changes and complex terrain make direct identification of its distribution points challenging, this study utilizes the host plant distribution range of M. saltuarius as an alternative to its actual habitat based on the distribution scope recorded in the Field Identification Manual of Forest Pests in Xinjiang. A total of 72 distribution points were randomly selected (using the same methodology as for PWD distribution points).

Figure 3.

Distribution of M saltuarius.

Figure 3.

Distribution of M saltuarius.

2.3. Environmental Variables

2.3.1. Environmental Variables Affecting the Spread of PWD

The transmission of PWD is classified into two categories: natural transmission and human-mediated transmission [

34]. Natural transmission includes the spread caused by vector insects feeding on healthy trees, the movement of PWD itself, and the contact of infected wood roots [

35,

36]. Considering the contribution rate of natural transmission factors and data availability, this study identifies vector-insect-affected coniferous forests as the natural transmission factor for PWD.

Human activities constitute the primary driver of PWD transmission. Accordingly, this study incorporates anthropogenic impact factors (a weighted composite of road networks and residential areas) (

https://search.earthdata.nasa.gov/). Furthermore, given that improper cable management in certain regions has previously established epidemic zones [

37], and the rapid expansion of tourism in Xinjiang has led to significant population mobility within scenic areas [

38], the research also integrates two anthropogenic transmission factors: the distance to power lines (

https://github.com/) and the proximity to A-level scenic spots (including those below 3A rating) (

https://data.beijing.gov.cn/).

2.3.2. Environmental Variables of M. saltuarius

Bioclimatic variables are climatic elements closely related to biological growth, development, distribution, and ecosystem functions. This study downloaded 19 historical bioclimatic variables (1970–2000) and altitude data with a 30-second resolution from the World Data Center for Climate (

https://www.worldclim.org/) for predicting the suitable habitat of

M. saltuarius.

While studies have shown that wind speed affects the dispersal of

M. saltuarius, thereby accelerating the spread of PWD [

39,

40,

41], this study has indirectly considered the dispersal effect through vector insect influence, thus not introducing an additional wind speed factor.

2.3.3. Acquisition of Other Environmental Variables

Other environmental variables are mainly used to generate natural transmission factors, including the 1km resolution China vegetation distribution map raster data (

https://www.resdc.cn/) (

Table 1) in addition to distribution point data.

2.4. Methodology

The transmission, colonization, and spread of diseases typically require the simultaneous fulfillment of four conditions: vector, pathogen, host plant, and suitable climate. However, existing studies have demonstrated that PWD can occur when both the pathogen and host trees coexist [

42], with vector insects playing an irreplaceable role in its transmission, colonization, and damage [

43]. Therefore, this study decomposes the prediction of potential occurrence areas for Xinjiang PWD into two components: the prediction of potential transmission areas and the prediction of potential suitable habitats for

M. saltuarius. The outputs of these two components are given equal weight and coupled to ultimately determine the potential occurrence areas of PWD.

2.4.1. Prediction Methods for Potential Transmission Areas of PWD

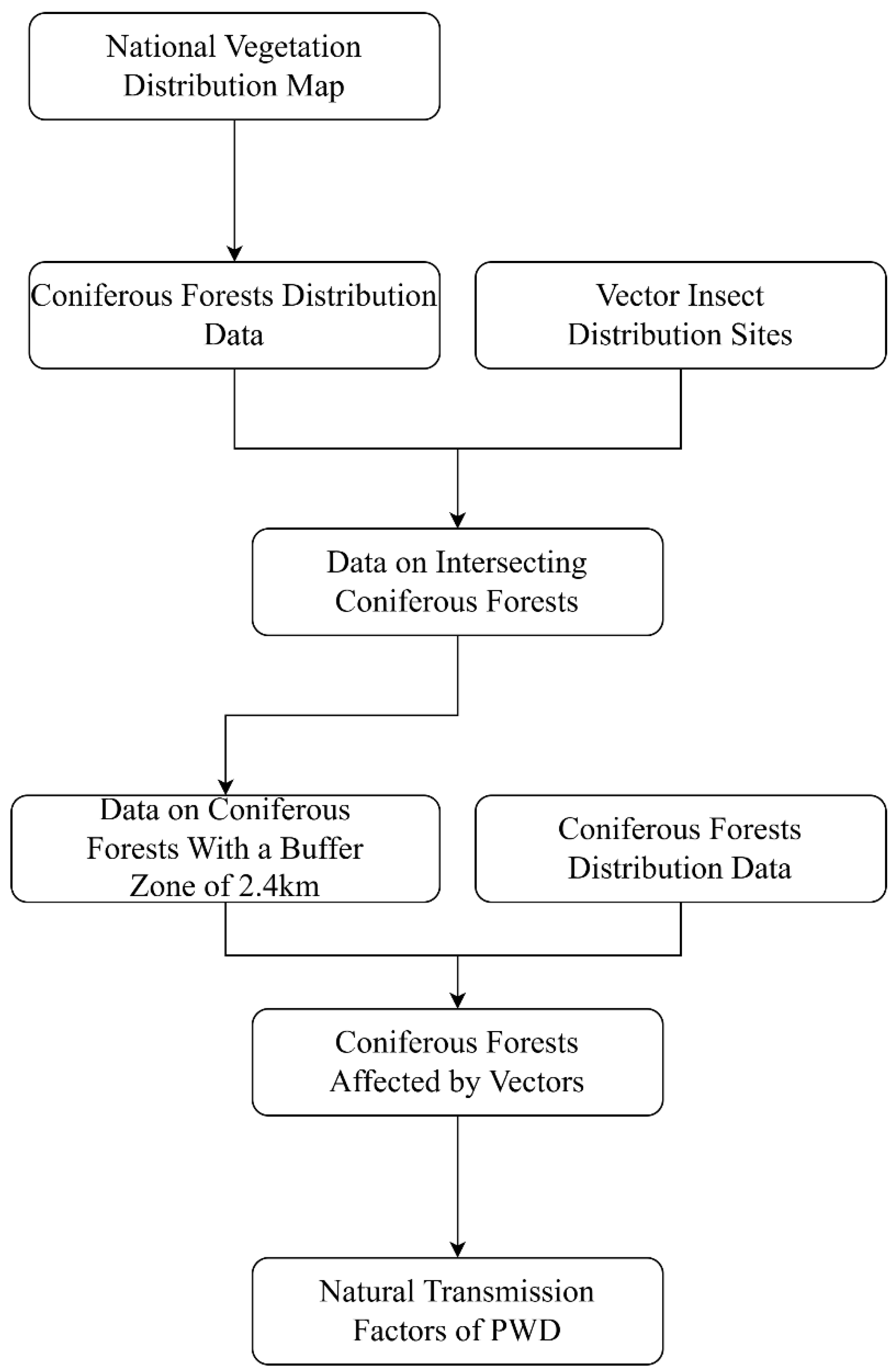

Currently, there are no ready-made data products on the natural transmission factors of PWD. Therefore, this paper utilizes QGIS, China vector insect distribution sites, and China vegetation distribution maps to create natural transmission factors, with the process as follows (

Figure 4): Extract coniferous forest data from the national vegetation distribution map and screen areas overlapping with vector insect distribution sites. Yanqing Liu et al. (2023) demonstrated in their study using Fushun as an example that coniferous forests within a 2.4km radius of the epidemic area are mostly affected [

44]. Given the lack of research on short-distance spread of epidemic areas in Xinjiang, this study uses a 2.4km buffer radius to screen coniferous forests influenced by the buffer zone. The aforementioned coniferous forest data is overlaid with China vector maps, and a new value field is added, assigning 1 to affected coniferous forests and 0 to unaffected ones (Note: The selection of vector insect distribution points requires balancing the issue of excessive contribution due to too few distribution points and insufficient contribution due to too many distribution points. Therefore, this study integrates literature, books, PWD distribution points, and additional distribution point data from various epidemic areas to ensure model accuracy).

For anthropogenic transmission factors, the publicly available datasets of anthropogenic impact factors, power lines, and Grade A scenic areas were acquired, processed into raster data, and their coordinate systems, pixel values, and boundaries (aligned with natural transmission factors) were unified. Finally, all publicly available datasets were processed into the ASCII format required by the model [

45].

Given that PWD has not been detected in Xinjiang, this paper imported the historical occurrence points of China PWD and the transmission impact factor data after treatment into MaxEnt model to construct a potential transmission area model of China PWD, and then used QGIS to delineate the potential transmission areas in Xinjiang. The model parameters were set as follows: 75% of the distribution points were used as the training set, 25% as the test set, and the remaining parameters were left default, with the results output in logistic format (file type.asc). To ensure model stability, the model was run 10 times, and the average value was taken as the final result, which was then visualized using the natural breakpoint method of QGIS reclassification.

2.4.2. Prediction Method of Potential Habitual Area of M. saltuarius

To reduce model multicollinearity [

46], we first standardized data from 20 biological factors (coordinate systems and pixel values) using QGIS, with boundaries defined by the administrative map of Xinjiang. Subsequently, by integrating the distribution sites of

M. saltuarius, we ran the MaxEnt model (parameters consistent with PWD transmission area model) 10 times, eliminating factors contributing less than 1%. Ultimately, 11 core influencing factors were selected, including Mean Temperature of Warmest Quarter (Bio10), Annual Precipitation (Bio12), Precipitation of Driest Quarter (Bio17), and Altitude (elev).

The distribution points of M. saltuarius were imported into MaxEnt model along with the 11 factors mentioned above, and the results were visualized using QGIS with predefined parameters.

2.4.3. Evaluation of Model Accuracy

The jackknife was employed to analyze and determine the contribution rates of each influencing factor. The model automatically generated a ROC curve, with the area under the curve (AUC) used to evaluate model accuracy (AUC values range from 0 to 1, where higher values indicate greater predictive accuracy). The evaluation criteria are as follows [

43]: AUC ≤ 0.6 is considered unqualified (unreliable results); 0.6–0.7 is poor; 0.7–0.8 is moderate; 0.8–0.9 is good; and 0.9–1.0 is excellent.

2.4.4. Coupling Methods

The potential distribution area of PWD was obtained by superimposing the potential distribution area of PWD and the potential suitable area of M. saltuarius with 1:1 weight.

3. Results

Previous studies suggested that Xinjiang was a non-risk area for PWD. However, the epidemic zone announcement released by The China National Forestry and Grassland Administration revealed that PWD continues to expand northwestward. This study identified the potential occurrence areas of PWD in Xinjiang by coupling the potential transmission zones of PWD with the potential suitable habitats of M. saltuarius.

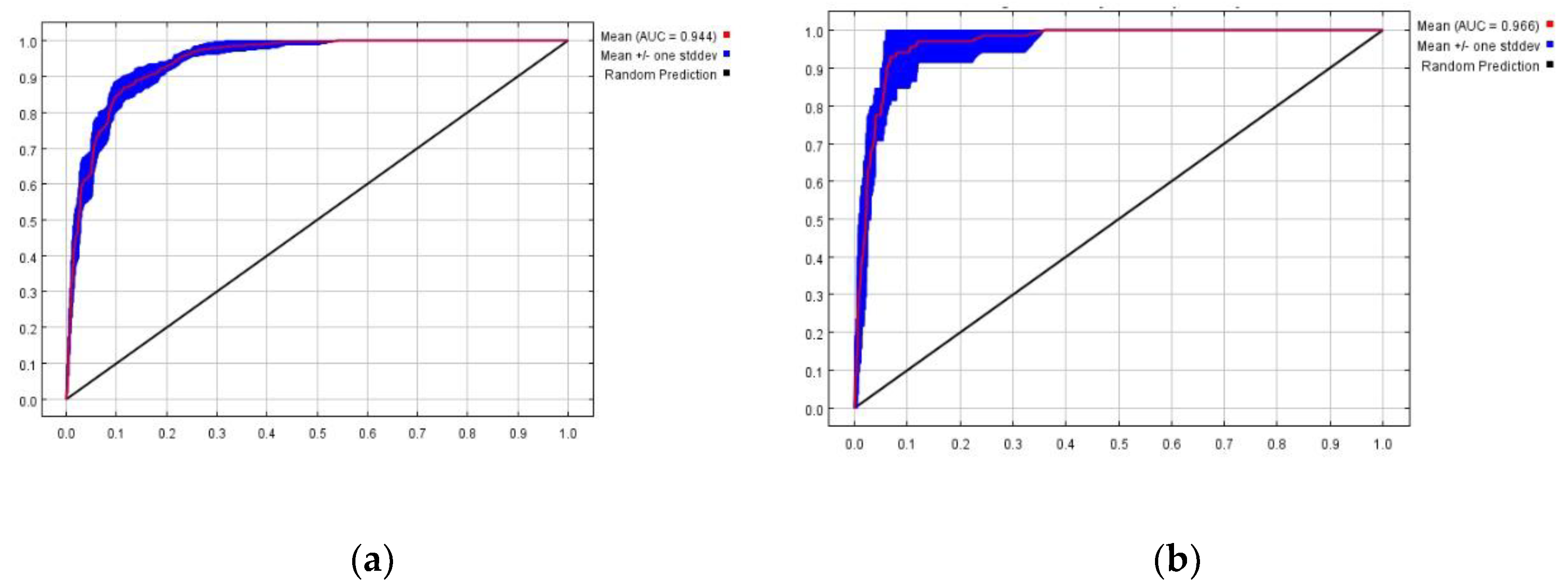

3.1. Model Accuracy

The mean AUC values of the 10 runs for the potential transmission zone model of PWD and the potential suitable habitat model of

M. saltuarius were 0.944 (

Figure 5-a) and 0.966 (

Figure 5-b), respectively, both meeting the 'excellent prediction accuracy' standard, indicating high reliability of the results.

3.2. Visualization of Potential Transmission Areas for PWD and Contribution Rates of Various Factors

The MaxEnt model constructed based on four transmission factors revealed that PWD could spread to Xinjiang, with high-potential transmission areas covering approximately 3,000 km² (probability 0.5–1), medium-potential transmission areas around 7,000 km² (probability 0.27–0.55), and low-potential transmission areas spanning about 54,000 km² (probability 0.1–0.27). All prefectures and cities in Xinjiang were identified as potential transmission risks. Notably, the Kashgar Prefecture, Aksu Prefecture, Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture, Bortala Mongol Autonomous Prefecture, Tacheng Prefecture, Urumqi City, and Altay Prefecture exhibited higher and broader potential transmission risks (

Figure 8-a).

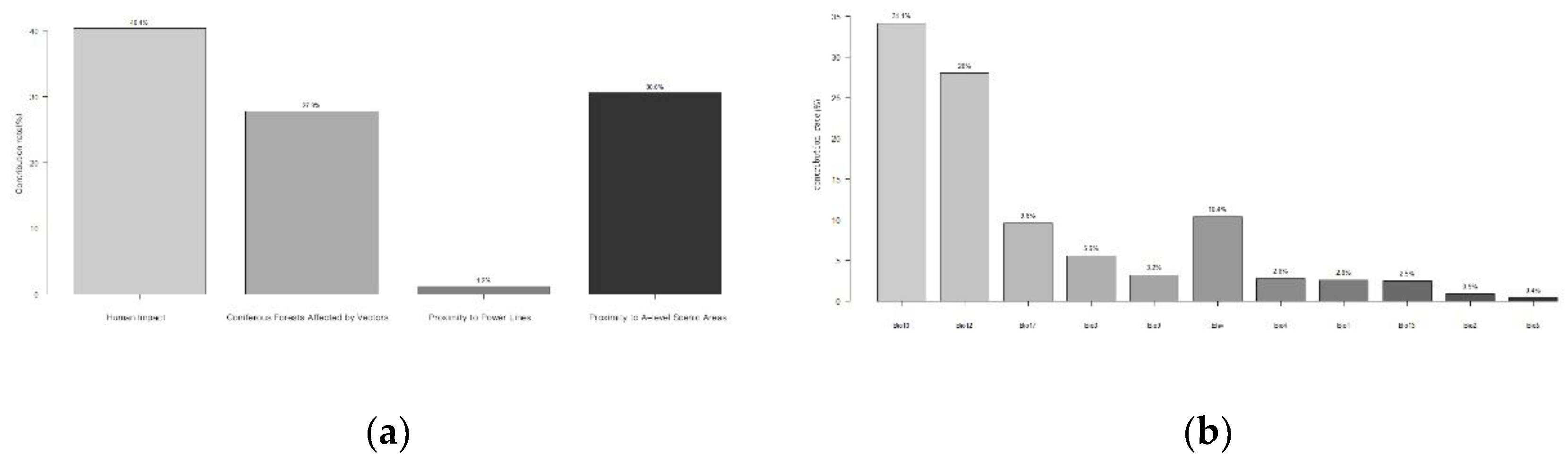

The contribution rates of transmission influencing factors for PWD were ranked from high to low as follows: anthropogenic factors (40.4%), distance to A-grade scenic spots (30.6%), coniferous forests affected by vector insects (27.8%), and distance to power lines (1.2%) (

Figure 6-a).

3.3. Contribution Rate and Visualization of Influencing Factors in Potential Habitats of M. saltuarius

After excluding factors with contribution rates below 1%,9 climate factors were eliminated from the initial set of 20 variables, including Min Temperature of Coldest Month (Bio6), Temperature Annual Range (Bio7), Mean Temperature of Wettest Quarter (Bio8), Mean Temperature of Coldest Quarter (Bio11), Precipitation of Driest Month (Bio14), Precipitation Seasonality (Bio15), Precipitation of Wettest Quarter (Bio16), Precipitation of Warmest Quarter (Bio18), and Precipitation of Coldest Quarter (Bio19).

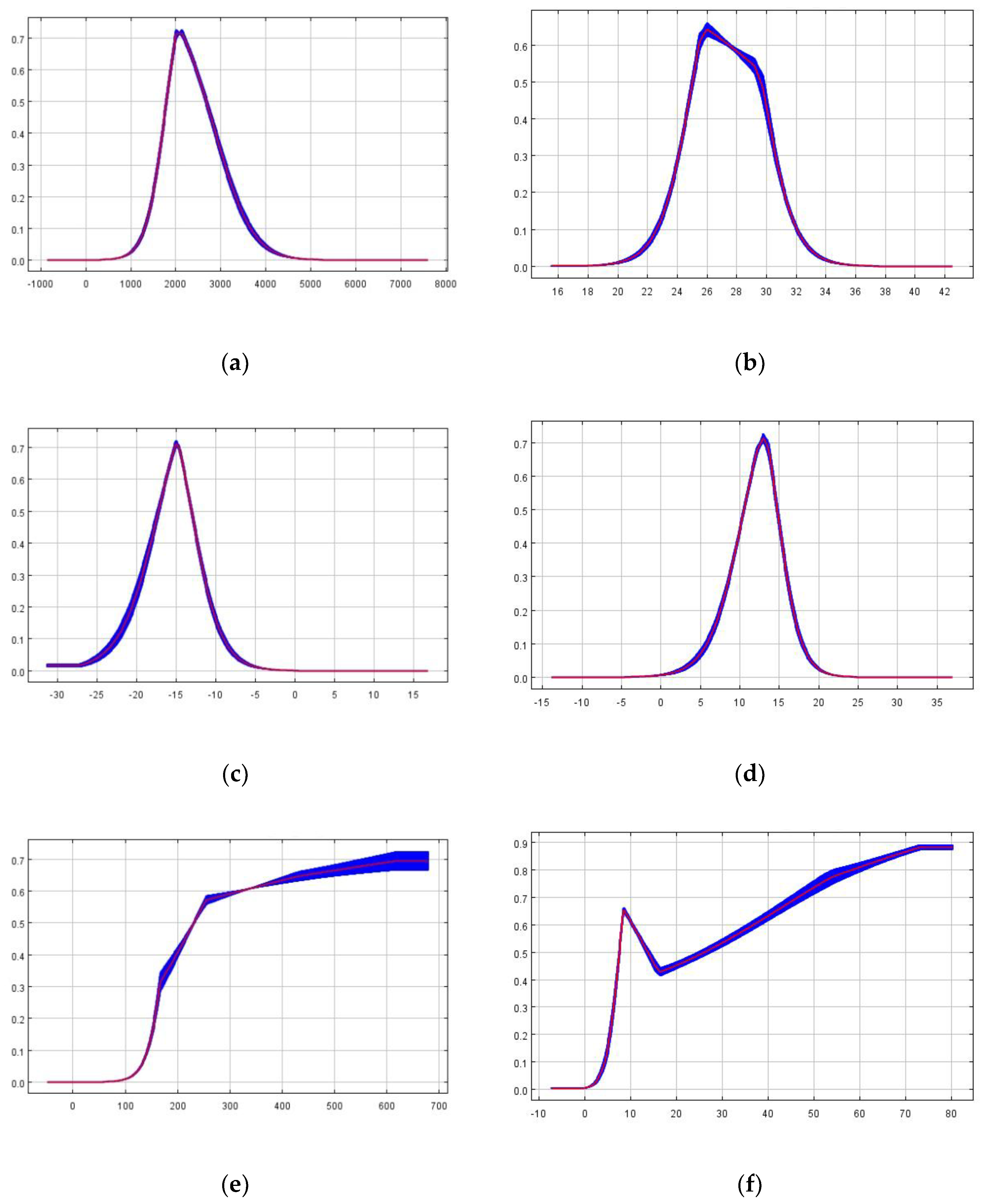

The results demonstrated that the core influencing factors for the suitable habitat of

M. saltuarius included Mean Temperature of Warmest Quarter (Bio10), Annual Precipitation (Bio12), Precipitation of Driest Quarter (Bio17), Altitude (elev), Isothermality (Bio3), and Mean Temperature of Driest Quarter (Bio9), with a combined contribution rate of 90.9% (

Figure 6-b). This study established the suitable habitat criteria for M. saltuarius using a 0.5 threshold, defining the optimal environmental conditions as follows: Altitude 1797–2676m (

Figure 7-a), Isothermality 0.25–0.29 (

Figure 7-b), Mean Temperature of Driest Quarter 17 to-13.1°C (

Figure 7-c), Mean Temperature of Warmest Quarter 10.6–14.7°C (

Figure 7-d), Annual Precipitation 232–679mm (

Figure 7-e), and Precipitation of Driest Quarter 7.6–13.7mm or 26–80mm (

Figure 7-f).

The MaxEnt model constructed based on 11 climatic factors revealed that the potential suitable habitat area for

M. saltuarius in Xinjiang covers approximately 71,200 km², including a high-suitable zone of 24,000 km² (probability 0.5–1), a medium-suitable zone of 27,000 km² (probability 0.26–0.5), and a low-suitable zone of 19,000 km² (probability 0.1–0.26). The visualization results indicate that the high-suitable zone of

M. saltuarius is more concentrated in the Altai Mountains (

Figure 8-b).

3.4. Visualization of Potential Occurrence Areas for PWD After Coupling

A 1:1 weighting was applied to the results of the potential transmission area of PWD and the potential suitable habitat area of

M. saltuarius, while the distribution map of coniferous forests in Xinjiang was used to restrict the occurrence area. The final potential occurrence area of PWD was obtained. The results showed that PWD can occur in Xinjiang, with the occurrence area accounting for 88% of the total coniferous forest area in Xinjiang, and is mainly distributed in the Altai Mountains and Tianshan Mountains (

Figure 8-c).

According to the area ratio and spatial distribution of the high potential transmission area and the high potential suitable area of the PWD, the Urumqi City, the Yili Kazak Autonomous Prefecture and the Altay Prefecture are the high risk areas of PWD, that is, PWD is likely to occur in these areas and spread to other areas.

The findings of this study can provide scientific references for forestry and relevant departments in Xinjiang, as well as offer new insights for predicting the occurrence of PWD in affected areas. However, this study has limitations: due to objective constraints, there may be deviations in the accuracy of vector insect distribution points, which could potentially have a minor impact on the prediction results.

Figure 8.

(a) Potential transmission area of PWD; (b) Potential occurrence area of M saltuarius; (c) Potential occurrence area of PWD; (d) Location and Distribution Map of Power Lines and Coniferous Forests.

Figure 8.

(a) Potential transmission area of PWD; (b) Potential occurrence area of M saltuarius; (c) Potential occurrence area of PWD; (d) Location and Distribution Map of Power Lines and Coniferous Forests.

4. Discussion

Identifying high-risk areas and transmission routes of PWD in Xinjiang is crucial for early prevention and control. This study simultaneously considers the introduction and spread processes of the disease, decomposing the prediction of potential occurrence areas into two components: the prediction of potential transmission areas for PWD and the prediction of potential suitable habitats for M. saltuarius. This approach better aligns with the actual differences in vector species and significant climatic variations between Xinjiang and southern epidemic regions. The prediction results indicate that PWD may occur in Xinjiang, with most coniferous forests classified as potential occurrence areas. Urumqi City, the directly administered areas of Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture, and Altay Prefecture are most likely to become the transmission sources of PWD in Xinjiang in the future.

According to the announcement by The China National Forestry and Grassland Administration, Xinjiang is one of the few regions in China where Pinaceae plants are distributed but not invaded by PWD. However, outbreaks have occurred in Liaoning and neighboring Gansu provinces at the same latitude (

http://www.forestry.gov.cn). Whether the introduction of PWD to Xinjiang has raised concerns among regulatory authorities and the public.

Although PWD has not been detected in Xinjiang, historical data on its occurrence across the country indicate a continued expansion trend toward the northwest. PWD exhibits strong environmental adaptability and has already caused damage in China's Qinling Mountains (high-altitude areas) and Liaoning (cold regions) [

19], with its suitable range continuously exceeding previous understanding. Studies have shown that PWD can occur only when both host trees and pathogenic nematodes coexist [

42]. Vector insects are the core of short-distance transmission for PWD [

44], and their adaptability to local climate directly determines whether the disease can occur.

Previous studies have indicated that Xinjiang does not contain potential areas for PWD [

17]. However, these studies only considered abiotic factors without accounting for biotic factors (such as vector insects and human activities), which significantly impacts the accuracy of disease occurrence prediction. The research by Nuermaimaitijiang Aierken et al. [

16] yielded results similar to this study's predictions. Nevertheless, since the study conducted global-scale predictions for PWD, it lacks practical relevance for targeted guidance by Xinjiang's forestry authorities and has limited practical value for future disease control in the region. This study focuses on potential occurrence areas of PWD in Xinjiang, employing transmission and diffusion factors combined with occurrence sites to predict potential transmission zones. Simultaneously, bioclimatic factors and the distribution sites of

M. saltuarius are utilized to predict its suitable habitats. By integrating both prediction results to analyze potential distribution areas of PWD in Xinjiang, while considering both the possibility of its introduction and subsequent spread, this method effectively predicts potential occurrence areas. This approach holds direct value and significance for the prevention and control of PWD in Xinjiang.

This study reveals that human activities account for nearly 75% of the spread of PWD in Xinjiang, consistent with previous research findings [

38]. This confirms the validity of our data, with human influence being the most significant factor—likely due to improper timber handling and distribution [

47]. The second most influential factor is proximity to Grade A tourist attractions. Most scenic spots in Xinjiang feature coniferous forests as their primary landscape, where dense human activity generates various waste products that facilitate the spread of PWD [

38]. Notably, the distance to power lines contributes less than 2%. Analysis of the spatial distribution of coniferous forests and power lines in Xinjiang shows that power lines are predominantly located in the Gobi Desert, with minimal overlap with coniferous forest areas (

Figure 8-d). Additionally, enhanced quarantine measures for cable materials by forestry authorities and related departments may further reduce their contribution rate.

The results of the prediction of the suitable habitat of M. saltuarius showed that precipitation (Annual precipitation and Rrecipitation In the Driest Quarter) and temperature (Mean Temperature of Warmest Quarter) were the key factors affecting its survival. There was no potential suitable habitat in southern Xinjiang, and the distribution of precipitation, temperature and host was the key reason restricting its survival.

In previous studies predicting the occurrence areas of PWD, the climate factors were similar to those in this study [

5,

17,

18]. The speculated reason is that the distribution of PWD depends on hosts and vector insects, while the southern epidemic areas of China are mainly distributed with

M alternatus, which is different from the vector insects in the north, thereby narrowing the suitable range of PWD and making the prediction of PWD occurrence areas more similar to the prediction of vector insect suitable areas.

As mentioned earlier, the main vectors of PWD differ between the north and south of China, with

M. saltuarius being the primary vector in the north and

M alternatus in the south. Studies have shown that if the vector insects are not adapted to the climate of the introduced area, it will lead to the interruption of PWD transmission chain [

48]. Therefore, Xinjiang (especially Urumqi City, Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture, and Altay Prefecture) needs to strengthen quarantine measures for timber from northern epidemic areas in logistics and trade, and improve the efficiency of rapid detection of PWD. Most scenic spots in Xinjiang are located in natural forests, so forestry and relevant departments need to enhance monitoring of PWD in these areas to reduce the risk of introduction [

38]. Additionally, vector insects are crucial for the transmission of PWD. Monitoring and controlling the population density of

M. saltuarius is also an effective measure to prevent the introduction and spread of PWD [

43].

This study still has limitations, as the incomplete acquisition of vector insect distribution data may lead to certain errors in the prediction results. With technological advancements and intensified survey efforts, the number of vector insect distribution sites can be increased to support subsequent research.

5. Conclusions

This study, considering the geographical characteristics of Xinjiang and the constraints of M. saltuarius as the sole vector insect, decomposed the prediction of potential PWD occurrence areas into the prediction of potential transmission areas and vector insect habitat suitability areas. The results indicate that Urumqi City, the directly administered areas of Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture, and Altay Prefecture are high-risk areas for PWD introduction. Human activities account for 75% of PWD transmission, with human impact factors and scenic area activities being key transmission routes. Vector insects play an irreplaceable role in the spread of PWD. Therefore, strengthening quarantine measures in northern epidemic areas, enhancing scenic area management, and monitoring and controlling the population density of M. saltuarius are effective approaches to prevent PWD invasion in Xinjiang. The prediction of potential PWD occurrence areas and the identification of high-potential areas in this study provide assistance to relevant departments in understanding transmission mechanisms and formulating control measures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H. G.; methodology, T. H. and Z. X.; software, T. H.; and Z. X.; and F. H.; formal analysis, Z. X.; investigation, Z. X.; data curation, H. G.; writing—original draft preparation, Z. X.; writing—review and editing, L. D. and Z. X. and H. G.; visualization, Z. X.; supervision, H. G.; project administration, H. G.

Funding

This research was funded by Xinjiang Forestry Development Subsidy Funds (Forestry and Grass Science and Technology (XJLYKJ-2023-08).

Data Availability Statement

Data Availability Statements are available in request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ye, J.; Wu, X. Research progress of pine wilt disease. Forest Pest and Disease. 2022, 41(3), 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Dwinell, L. D. First report of pinewood nematode (Bursaphelenchus xylophilus) in Mexico. Plant Dis. 1933, 77, 846A. [CrossRef]

- Robinet, C.; David, G.; Jactel, H. Modeling the distances traveled by flying insects based on the combination of flight mill and mark-release-recapture experiments. Ecol. Modell. 2019, 402, 85-92. [CrossRef]

- Tóth, Á. Bursaphelenchus xylophilus, the pinewood nematode: Its significance and a historical review. ABS. 2011, 55, 213–217. [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Yu, R.; Yang, C., et al. Prediction of invasion risk of pine wilt disease based on GIS spatial technology and MaxEnt model in western Sichuan Province of southwestern China. Beijing For. Univ. 2023, 45(9), 104-115. https://link.cnki.net/urlid/11.1932.s.20230831.1347.

- Ye, J. Epidemic Status of Pine Wilt Disease in China and Its Prevention and Control Techniques and Counter Measures. Scientia silvae sinicae. 2019, 55(09), 1-10. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=OfZxIIxxsvCFyty0VDNKCXGOXHaOOY_AhGq0IZrW0mH9J1S1SHr4kwDxNJ9XKkSMI-DEwxZsZ2GjH0cdC803_zS-_cspa661XI4k8oQuu-4UHVs5Fz_hZpEsqELRiT_5w5Pw4kFNAYPNTzA2lsBZ_HXcOEW5tO_zxcm2P183DWvXnRa40JQyhQ==&uniplatform=NZKPT&languag.

- Mamiya, Y.; Enda, N. Transmission of Bursaphelenchus Lignicolus (Nematoda: Aphelenchoididae) by Monochamus Alternatus (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae). Nematologica. 1972, 18, 159–162. [CrossRef]

- Futai, K. Pine wood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2013, 51, 61–83. [CrossRef]

- Fu, D.; Hu, S.; Ye, H., et al. Pine wilt disease in Yunnan, China: Evidence of non-local pine sawyer Monochamus alternatus (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) populations revealed by mitochondrial DNA. Insect Sci. 2010, 17(5), 439-447. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, F.; Yamane, A.; Ikeda, T. The Japanese Pine Sawyer Beetle as the Vector of Pine Wilt Disease. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1984, 29, 115-135. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhang, S.; Wei, W., et al. Chemical Signals Synchronize the Life Cycles of a Plant-Parasitic Nematode and Its Vector Beetle. Curr Biol. 2013, 23(20), 2038-2043. [CrossRef]

- Back, M.A.; Bonifácio, L.; Inácio, M. L., et al. Pine wilt disease: A global threat to forestry. Plant Pathol. 2014, 73, 1026–1041. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Shi, Y.; Fan, L., et al. Investigation on long-horned beetle species in pine wilt disease epidemic area in Dalian. Forest Pest and Disease 2021, 40(3), 36-39. https://link.cnki.net/doi/10.19688/j.cnki.issn1671-0886.20210001.

- Ning, H. Impacts of Climate Change on The Suitable Distribution of Dendroctonus armandi, Trypophloeus klimeschi and Their Host in China. PhD. Northwest A&F University, Shanxi, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Li, T.; Lin, Y. Prediction of the Potential Distribution of Bursaphelenchus xylophilus in Sichuan Province Using MaxEnt Model. Sichuan Journal of Zoology 2019, 38(1), 37−46. https://link.cnki.net/urlid/51.1193.Q.20181212.1739.018.

- Aierken, N.; Wang, G.; Chen, M., et al. Assessing global pine wilt disease risk based on ensemble species distribution models. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 167, 112691-112691. [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xiang, Y., et al. Prediction of potential distribution of Bursaphelenchus xylophius in China based on Maxent ecological niche model. Journal of Nanjing Forestry University (Natural Sciences Edition) 2015, 39(1), 6−10. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Pu, Y.; Li, H., et al. A study on Potential Biotope of Pine Wilt Disease in Chongqing by using MaxEnt Model. Ecology and Environmental Monitoring of Three Gorges. 2017, 3(3), 75−80. https://link.cnki.net/doi/10.19478/j.cnki.2096-2347.2017.03.10.

- Hao, Z.; Fang, G.; Huang, W., et al. Risk Prediction and Variable Analysis of Pine Wilt Disease by a Maximum Entropy Model. Forests. 2022, 13(2), 342-342. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Liu, Y.; Tang, Z., et al. Community structure and influencing factors of mountain coniferous forest in Xinjiang. Arid Zone Res. 2011, 28(01), 31-39. https://link.cnki.net/doi/10.13866/j.azr.2011.01.004.

- Hu, B.; Huang, W.; Hao, Z., et al. Invasion of Pine Wilt Disease: A threat to forest carbon storage in China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 169, 112819-112819. [CrossRef]

- Forestry Pest Control and Quarantine Bureau of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region.Wildlife identification manual of forest pests in Xinjiang, China Forestry Publishing House Beijing, China, 2014, 347.

- Zou, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Guo, S., et al. Risk of Monochamus saltuarius spreading in China. Chinese Journal of Applied Entomology. 2023, 60(01), 287-297. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=OfZxIIxxsvALwrgzLDLMHyYzOVvyH_V7PcG4hg7YBwAImMTGDg5mZjV59hQJJYp6Oq6lhpSHD-hv6LJYbtpjuweaiPACU8EXkS2nS2jc1MNLymFMwkWWTa_IXFLoTf6OoIsP10g_h8tONw35cMPid308twHvhadDYkVRFEBQI3PeV4DipgFbZg==&uniplatform=NZKPT&languag.

- Zheng, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, W., et al. Parasitic Effect of Dastarcus helophoroides of Monochamus alternatus Biotype on Monochamus saltuarius. Chinese Journal of Biological Control. 2022, 38(03), 587-594. https://link.cnki.net/doi/10.16409/j.cnki.2095-039x.2022.05.002.

- Wang, W.; Zhu, Q.; He, G., et al. Impacts of climate change on pine wilt disease outbreaks and associated carbon stock losses. Agric. for. Meteorol. 2023b, 334, 109426. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Xian, X.; Yang, N., et al. Risk assessment framework for pine wilt disease: Estimating the introduction pathways and multispecies interactions among the pine wood nematode, its insect vectors, and hosts in China. Sci Total Environ. 2023, 905, 167075-167075. [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y. Control technology of Monochamus saltuarius in Guan censhan forest area. Forestry of Shanxi. 2025, (01), 50-51. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Deng, X.; Zhang, Y., et al. Survey of Longicorn Species in Pinus koraiensis Plantation in Dongning City, Heilongjiang Province. Forestry Science & Technology. 2025, 50(01), 55-58. https://link.cnki.net/doi/10.19750/j.cnki.1001-9499.2025.01.012.

- Wang, S. Ecological characteristics and control methods of Monochamus saltuarius-Taking Zuojialin Farm, Xiaolongshan Forestry Protection Center, Gansu Province as an example. Guangdong Canye. 2024, 58(08), 34-36. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Sun, F.; Cao, C., et al. The catching effect of two means on Monochamus saltuarius in field experiments. Journal of Nanjing Forestry University(Natural Sciences Edition), 2025, 1-8. https://link.cnki.net/urlid/32.1161.S.20240403.0928.002.

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Shu, H., et al. Study on the number of Bursaphelenchus xylophilus carried by Monochamus saltuarius adult.Journal of Beijing Forestry University 2023, 45(08), 142-147. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=OfZxIIxxsvCvPB5vpfTfwAeXJR-sYH8kZKbQrSUYk_ZDPecHh7RiSylxypagDZvPxf7aRr2OTn1woJsycVqn3aVJGVxHThnJF5txjpnTD6D__5Jq1SLAMcelk6ZHwVQPFYzRWykCwTsImArw42KJXymj5EB_fPjpbawZqanweYe0xoxhNPVIpQ==&uniplatform=NZKPT&languag.

- Dong, Z.; Nie, H.; Zhong, C., et al. Feeding preferences of adult Monochamus saltuarius on four host pine trees. Contemporary Horticulture. 2022, 45(20), 18-19+53. [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Shi, Y.; Jiang, S., et al. Study on the species of Longhorned beetles carrying Bursaphelenchus xylophilus in Liaoning. Forest Research. 2021, 34(06), 174-181. [CrossRef]

- Haran, J.; Rousselet, J.; Tellez, D., et al. Phylogeography of Monochamus galloprovincialis, the European vector of the pinewood nematode. Pest Sci. 2018, 91(1), 247-257. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhao, X.; Mo, X., et al. Host vegetation connectivity is decisive for the natural spread of pine wilt disease. Pest Manag. Sci. 2024, 80(10), 5141-5156. [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Huang, J.; Li, X., et al. The interaction of environmental factors increases the risk of spatiotemporal transmission of pine wilt disease. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 133, 108394. [CrossRef]

- Strengthen quarantine law enforcement of infected trees and make every effort to control the spread of pine wood nematode. Land Greening. 2019, (09), 50-51. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=OfZxIIxxsvDVzstd9eEdvjhwFo98ZPcOdKkys_zJ0W4SIgSMilVtASHwsSN4MgqA2duwiGAWugLnLr4CkowzebuPpQYu4E1QQM1Rq4DL8m5ENS4-BAFS5D-ibf6eEXJZ_lZPdiSuESpaZIHyJaPaUNiU4D7ndysYjViLkBhevTfLC49ryGtguw==&uniplatform=NZKPT&languag.

- Hao, Z.; Huang, J.; Zhou, Y., et al. Spatiotemporal Pattern of Pine Wilt Disease in the Yangtze River Basin. Forests. 2021, 12(6), 731-731. [CrossRef]

- Gao R; Wang Z; Wang H, et al. Relationship between Pine Wilt Disease Outbreaks and Climatic Variables in the Three Gorges Reservoir Region. Forests. 2019, 10(9), 816-816. [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Niu, S. The Effects of Climatic Factors on Pine Wilt Disease. Forest Resources Management. 2008, (04), 70-76. [CrossRef]

- Yutaka, O.; Takehisa, Y.; Etsuko, S., et al. Disentangling the drivers of invasion spread in a vector-borne tree disease. Anim. Ecol. 2018, 87(6), 1512-1524. [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, C. Bursaphelenchus Xylophilus (pine wilt nematode). CABI, Compend. 2022; CABI Compendium,10448.Downloaded from. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Guo, Q.; Xie, N., et al. Predicting the global potential distribution of Bursaphelenchus xylophilus using an ecological niche model: expansion trend and the main driving factors. BMC ecol. evol. 2024, 24(1), 48-48. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Huang, J.; Yang, T. Natural Factors Play a Dominant Role in the Short-Distance Transmission of Pine Wilt Disease. Forests. 2023, 14(5), 1059. [CrossRef]

- Eli,S.; Abdukerim, R.; Mamtimin, Y., et al. Assessment of Habitat Suitability for Gazella subgutturosa in the Xinjiang Based on the MaxEnt Modeling. Chinese Journal of Wildlife. 2019, 40(01), 27-32. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F.; S. D. P.; Ye. L., et al. Collinearity in ecological niche modeling: Confusions and challenges. Ecol Evol. 2019, 9(18), 10365-10376. [CrossRef]

- Hu, G. Study on the Harm and Comprehensive Control Measures of Pine Wood Nematode Disease. Journal of Agricultural Catastropholgy. 2021, 11(12), 31-32. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=OfZxIIxxsvBEi3ya9WYln3nO8r2qa1xFPzSaor_-De9gibyVQ7rP0orh51cOn--AvsQQ5mI-OWvfntFeacVFbIA80RI-cHvhSdtl9HbkgFgV7XQqqGDXZhE9zP-b_C6nU5ahKsIxpY40yOAeF35jnOD3YDVP0Q_D-q_FSWe2-gTl9TlW1-4Mjg==&uniplatform=NZKPT&languag.

- Zhou, H.; Xie, M.; Koski, M. T., et al. Epidemiological model including spatial connection features improves prediction of the spread of pine wilt disease.Ecol. Indic. 2024, 163, 112103. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).