1. Introduction

Nocturia is a prevalent and clinically relevant lower urinary tract symptom (LUTS) defined by the International Continence Society (ICS) as the need to wake from sleep one or more times to void [

1]. The terminology and clinical definition used in this manuscript follow ICS standards, specifying that nocturnal voiding occurs after sleep onset and before final awakening. While a single nighttime void may be tolerated by many individuals, recurrent awakenings are associated with impaired daily functioning, reduced vitality, and diminished well-being [

2]. Nocturia is therefore recognized as a symptom reflecting underlying physiological or pathological processes rather than a normal consequence of aging.

According to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11), nocturia is classified as a lower urinary tract symptom and defined as waking one or more times during the main sleep period to void (ICD-11: MB40.0). This definition aligns with ICS terminology, distinguishing nocturia as a clinical symptom linked to sleep interruption and urinary physiology rather than a behavioral or psychiatric condition. Importantly, nocturia is not defined in the DSM-5, as it does not constitute a mental health disorder; instead, it may contribute secondarily to psychological distress or reduced well-being through sleep fragmentation and chronic symptom burden.

Nocturia is highly prevalent in clinical practice, particularly among older adults, where it is frequently associated with fragmented sleep, daytime fatigue, reduced productivity and diminished quality of life [

3,

4]. Despite this clinical relevance, evidence regarding nocturia and its impact on sleep and health-related quality of life in Greek clinical settings remains limited. Understanding patient-reported outcomes is essential, as nocturia represents a subjective and multifactorial symptom that cannot be fully characterized by urological parameters alone. The Athens Insomnia Scale (AIS) provides a standardized measure of sleep disturbance, and the EQ-5D assesses health-related quality of life, including a single dimension on anxiety/depression [

5,

6,

7]. These tools do not assess mental health as a clinical construct; rather, they offer insight into how nocturnal awakenings influence sleep quality and perceived well-being.

Given the increasing recognition of nocturia as a complex symptom associated with reduced life satisfaction and impaired functioning, further research is warranted to better characterize its burden in real-world clinical populations. The primary aim of this study was to examine the frequency of nocturia episodes and their association with sleep disturbance and health-related quality of life in individuals presenting to a urology outpatient clinic. By focusing on patient-reported outcomes, this study seeks to contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of nocturia and its implications for daily living. Given the limited research conducted in Greek clinical populations, the study focuses on individuals presenting to a urology outpatient clinic, without aiming to establish population-level prevalence.

2. Nocturia

Nocturia is not a symptom exclusive to older adults, as it may occur at any age. Its estimated prevalence in children is approximately 15% at the age of five, decreasing to about 4% in adolescence [

5]. The prevalence then increases substantially in adulthood, reaching 58% and 66% among men and women aged 50–59 years, respectively, and rising further to 72% and 91% in individuals over 80 years of age [

6,

7].

This age-related increase is not only attributable to the burden of comorbid conditions frequently observed in older individuals but also to physiological changes associated with aging. The kidneys progressively lose their ability to concentrate urine, which leads to increased nocturnal urine production when renal perfusion rises in the recumbent position during sleep [

8,

9]. Patients with nocturia may experience varying degrees of distress: some are significantly bothered by their symptoms, while others consider the condition tolerable. Ultimately, the level of discomfort often determines whether individuals seek medical attention [

1].

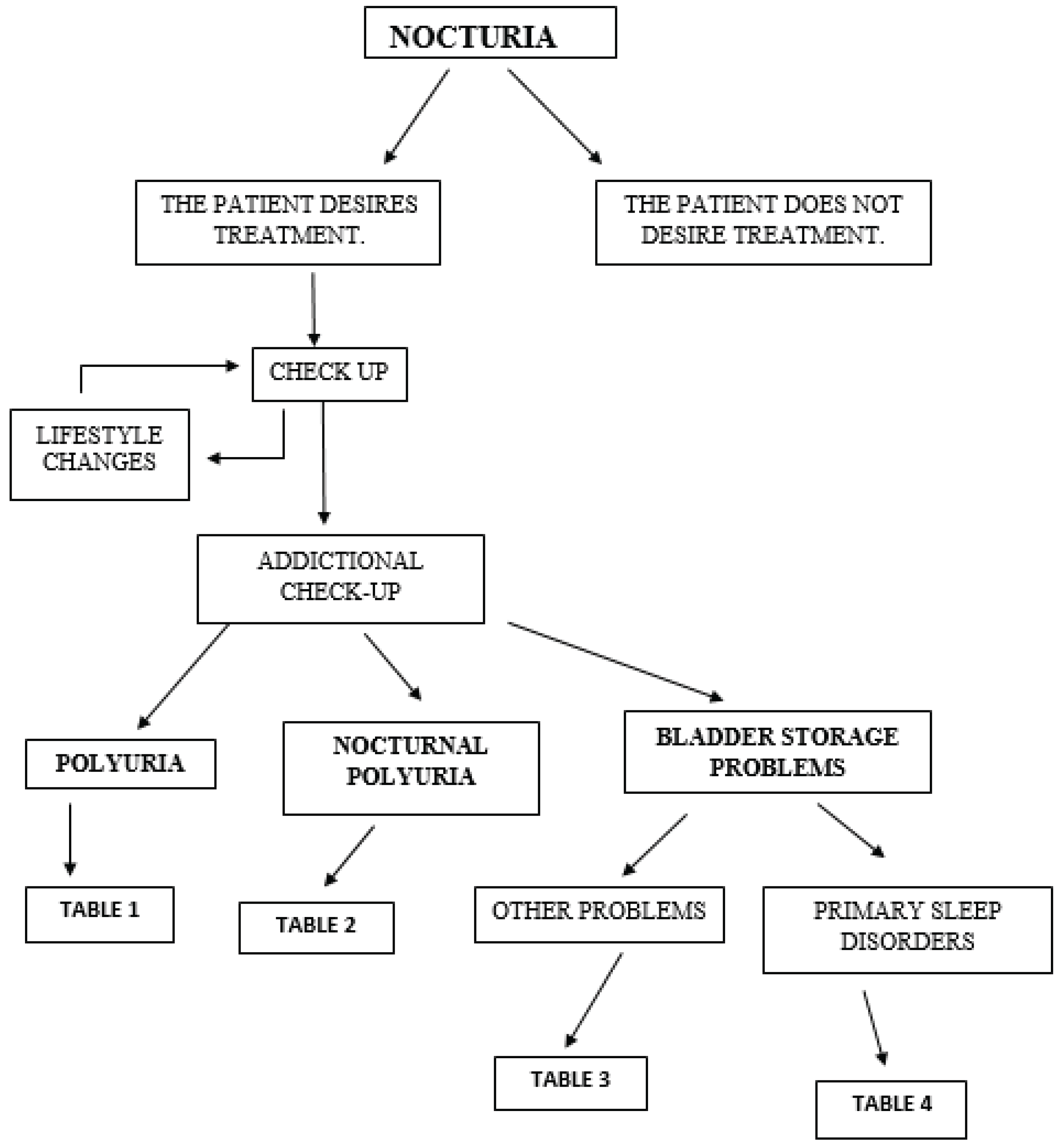

The initial assessment of nocturia is guided by a simple diagnostic algorithm, illustrated schematically in

Figure 1.

Like urinary frequency, nocturia may result from either increased urine production or reduced bladder storage capacity [

1]. Daytime urinary frequency in the absence of nocturia is often psychogenic in origin and is most commonly associated with anxiety disorders [

10]. Nocturia can also occur in individuals who consume large volumes of fluid late in the day, particularly caffeinated or alcoholic beverages, which exert a pronounced diuretic effect [

11,

12].

Patients presenting with nocturia may seek consultation from various medical specialties, each applying its own clinical approach. A standardized definition is therefore essential to ensure consistent diagnosis and therapeutic decision-making across disciplines [

13,

14]. Shared clinical terminology promotes uniform evaluation and management and reduces fragmentation in care.

Lifestyle modification represents the first-line intervention. Reducing the intake of caffeine, alcohol, and fluids during the evening hours may be beneficial. Extreme fluid restriction, however, should be avoided, particularly in individuals with unrecognized diabetes insipidus [

12]. If these initial measures fail to improve symptoms, patients should be advised to seek further clinical evaluation [

13,

14].

Diagnostic workup should begin with a 1–3-day voiding diary documenting fluid consumption, timing and volume of urination, sleep patterns, and subjective sleep quality. Although assessing quality of life is crucial, no single questionnaire comprehensively captures the overall burden of nocturia [

15,

16]. In cases where nocturia coexists with suspected sleep pathology, polysomnography (PSG) may aid in identifying contributory disorders [

17,

18]. A thorough and systematic evaluation enables identification of the underlying etiology and supports individualized treatment planning [

15,

16].

2.1. Nocturia, Sleep Disorders & Quality of Life

In older adults, particularly those with insomnia, frequent nocturnal voiding further disrupts already compromised sleep quality. Numerous studies have demonstrated that increasing nighttime urination is associated with poorer sleep outcomes [

19]. Nocturia may cause sleep disturbances in up to 75% of elderly individuals [

6]. More than 60% of older adults experience nocturia, although the condition remains largely underrecognized by the general population. The resulting sleep loss and fragmentation can lead to fatigue, mood changes, daytime somnolence, reduced productivity, impaired concentration, elevated accident risk, and cognitive decline [

20,

21]. Notably, approximately 25% of falls among older individuals occur at night, with a substantial proportion of these events happening when patients rise to void [

1]. Furthermore, nocturia has been associated with increased morbidity and mortality [

22,

23,

24].

Nocturia negatively affects not only sleep, but also multiple dimensions of quality of life, often extending to the patient’s partner or family [

25,

26]. Both the frequency of nocturnal episodes and the timing of awakenings play a critical role in determining disease burden. Given these wide-ranging consequences, nocturia must be recognized as an important health condition that contributes to substantial morbidity, reduced life satisfaction, and psychological and social strain. Diagnostic tools are available to facilitate early and accurate identification, and several therapeutic approaches exist to alleviate symptoms [

3,

27]. Nevertheless, additional research is required to guide the development of targeted and individualized treatment strategies.

Although several instruments for evaluating quality of life are available, the concept of Quality-Adjusted Life Years (QALYs) has gained notable attention among clinicians and health economists over the past two decades. QALYs integrate life expectancy with quality of life and represent the number of years lived in full health [

28,

29]. This internationally recognized metric, introduced in the 1970s, is calculated by weighting the duration spent in a given health state with a utility score derived from standardized assessments [

30]. Despite being less sensitive to chronic conditions and preventive interventions, QALYs may offer valuable insights for assessing treatment strategies and healthcare interventions for nocturia [

31].

2.2. Causes of Nocturia

2.2.1. Polyuria

Polyuria is defined as a 24-hour urine output exceeding 40 mL per kilogram of body weight—equivalent to more than 3000 mL per day in an adult weighing approximately 70 kg [

32,

33]. When polyuria is suspected, diagnostic evaluation should first determine whether the condition is attributable to diabetes mellitus or diabetes insipidus, and subsequently identify the specific subtype (

Table 1).

Assessment typically includes measurement of glucose levels in serum and urine over a 24-hour period, complemented by targeted diagnostic tests to differentiate among etiologies and resolve the diagnostic uncertainty [

34,

35].

2.2.2. Nocturnal Polyuria

Nocturnal polyuria refers to the excessive production of urine during nighttime sleep. Measurement includes the total urine volume produced from the time an individual lies down to sleep until the first awakening to void [

11]. In younger individuals, nocturnal polyuria is defined as nighttime urine output exceeding 20% of the total 24-hour urine volume, whereas in individuals aged 65 years or older, this threshold increases to more than 33% [

11,

36]. In such cases, the increased nocturnal urine production is typically accompanied by a compensatory reduction in daytime output, resulting in a preserved total 24-hour urine volume. The principal etiologies of nocturia are summarized in

Table 2 [

10].

Certain populations represent exceptions to these criteria. Patients with diabetes insipidus and individuals whose sleep duration significantly deviates from the standard eight-hour cycle may demonstrate altered urine output patterns that fall outside conventional definitions [

3]. Nocturnal polyuria is also common among patients with congestive heart failure or peripheral edema, in whom recumbency increases venous return and intravascular volume, subsequently enhancing renal perfusion and urine production during sleep [

8].

2.2.3. Bladder Storage Disorders

Patients with nocturia who do not exhibit polyuria are more likely to experience reduced bladder storage capacity or disturbances in sleep architecture. Reduced functional bladder capacity can be identified through the use of a voiding diary, comparing the nocturnal voided volume with the individual’s maximum functional bladder capacity at any given time [

37]. However, the distinction between normal and abnormal nocturnal urine volumes is not clearly standardized, and relying solely on this comparison may lead to inaccurate assessment (

Table 3). To more accurately evaluate nocturia, several quantitative indices have been developed, including the nocturia index—defined as the ratio of average nocturnal urine volume to functional bladder capacity—and the nocturnal polyuria index, calculated as the ratio of average nocturnal urine volume to total 24-hour urine output [

38].

This table highlights several factors that impair bladder storage capacity and can contribute to symptoms such as urgency, incontinence, or nocturia [

39]. In men, benign prostatic hyperplasia is the most prevalent cause of obstructive lower urinary tract symptoms, including nocturia [

40,

41]. In women, nocturia is most commonly associated with overactive bladder, a condition that frequently remains undiagnosed [

42].

It is also important to recognize that, despite suggestive voiding diaries, the underlying cause of nocturia may be a sleep disorder. Individuals who awaken during the night and subsequently void—even when passing only small volumes of urine—may suffer from sleep-related disturbances [

19,

43]. Additional sleep disorders associated with nocturia are listed in

Table 4 [

19,

43]. In such cases, accurate diagnostic evaluation is critical to ensure appropriate management.

2.3. Treatment of Nocturia

The primary objective in treating nocturia is symptom reduction. Therefore, identifying the underlying etiology—whether behavioral, medical, or surgical—is essential in guiding appropriate management [

1]. The effectiveness of treatment varies according to contributing factors and is closely linked to improvements in patient well-being. Core therapeutic goals include decreasing the number of nocturnal voids, minimizing symptom-related distress, prolonging the time before the first awakening, increasing total sleep duration, and addressing comorbid medical conditions [

1,

4].

Initial management typically focuses on lifestyle modification, although evidence from controlled clinical trials remains limited. Fluid intake during the evening and caffeine consumption in older adults do not appear to be directly associated with increased nocturia, and a 25% reduction in overall daily fluid intake has demonstrated limited clinical benefit [

44]. Physical exercise, particularly pelvic floor muscle training and bladder retraining, has proven effective for patients with overactive bladder [

45]. Furthermore, engaging in a 30-minute evening walk over an eight-week period has been associated with a reduction in nocturia episodes and a 50% improvement in quality-of-life scores [

46]. These findings underscore the role of physical activity in enhancing bladder function and patient well-being, although many individuals struggle to modify established lifestyle habits.

Pharmacological therapy is typically considered when behavioral measures are insufficient. Desmopressin, a synthetic analogue of the antidiuretic hormone, is widely used in both pediatric and adult populations. Administered orally or intranasally, it reduces urine production for approximately 7–12 hours and maintains therapeutic efficacy for more than 12 months [

47]. Notably, desmopressin has been shown to reduce nocturia episodes by more than 50%, with a 34% reduction in nocturnal urine volume observed in women and a 20% reduction in men [

48].

Loop diuretics, administered 4–6 hours before bedtime, represent an alternative or adjunctive strategy, provided that the patient does not present with obstructive uropathy [

49]. Among these, furosemide is the most potent short-acting agent. Combination therapy with furosemide and desmopressin has demonstrated significant reductions in nocturnal urine output and nocturia frequency, while also improving the duration of uninterrupted sleep [

50]. These interventions have been associated with improved sleep continuity, enhanced quality of life, and increased productivity.

Antimuscarinic agents are frequently used in patients with nocturia secondary to detrusor overactivity. While clinical outcomes vary, nighttime administration can reduce urgency-associated nocturnal voiding [

51]. α-blockers have been shown to alleviate nocturia and lower urinary tract symptoms in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia, while also improving the nocturnal polyuria index and restoring circadian rhythms of urine production [

52].

Surgical interventions for benign prostatic hyperplasia may lead to short-term reductions in nocturia; however, among lower urinary tract symptoms, nocturia tends to show minimal sustained improvement over time [

40].

Sedatives and hypnotics have demonstrated efficacy in the short-term management of nocturia and may also benefit male patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia who have an inadequate response to α-blocker therapy [

53]. Additionally, treatment of obstructive sleep apnea with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) has been shown to reduce nocturia episodes in older adults [

54].

Ultimately, the effectiveness of nocturia treatment should be assessed from a patient-centered perspective, taking into account the degree of symptom-related discomfort and its impact on daily functioning. Further research is needed to better characterize the economic burden of nocturia, elucidate its pathophysiological mechanisms, and clarify its interactions with sleep stages and sleep disorders.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Setting and Participants

This study employed an observational, cross-sectional design conducted at the Urology Outpatient Clinic of the General Hospital of Eastern Achaia. The primary variable was the frequency of nocturnal awakenings to void. Secondary variables included sleep disturbance measured by the Athens Insomnia Scale (AIS), nocturia-related quality of life measured by the Nocturia Quality of Life questionnaire (N-QOL), and health-related quality of life measured using the EQ-5D and EQ-VAS instruments. Demographic and clinical characteristics (age, gender, diabetes mellitus, benign prostatic hyperplasia, overactive bladder symptoms, and use of diuretics) were evaluated as potential explanatory or modifying factors.

All patients presenting to the clinic between November 2023 and May 2024 who reported nocturia were invited to participate. The clinic serves a mixed population from both urban and rural regions of Aigialeia and Kalavryta. Participants were recruited using consecutive non-probability sampling, including all individuals who reported nocturia during their visit to the Urology Outpatient Clinic within the study period.

3.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria were:

Self-reported nocturia (≥ 1 nocturnal voiding episode),

Age ≥ 18 years,

Ability to understand and complete the questionnaire.

No exclusion criteria were applied, as the aim was to capture real-world presentations of nocturia. All individuals who reported nocturia were eligible for inclusion, irrespective of additional urological or non-urological conditions, psychological status, ongoing life stressors, or concurrent medications. This approach was adopted to preserve ecological validity and accurately reflect the clinical population presenting with nocturia in this healthcare setting.

3.3. Data Collection Procedure

After obtaining informed consent, participants completed a structured questionnaire administered in paper form during the clinic visit. Demographic characteristics (age, gender, marital status, employment, and education), medical history (diabetes mellitus, benign prostatic hyperplasia, overactive bladder), current medication use (including diuretics, anxiolytics, and antidepressants), and daily fluid intake were recorded. Pairwise post hoc comparisons were not conducted, as the analyses aimed to assess overall group effects rather than identify specific pairwise differences.

3.4. Assessment Instruments

3.4.1. N-QOL (Nocturia Quality of Life Questionnaire)

The Nocturia Quality of Life (N-QOL) questionnaire evaluates the impact of nocturia on daily functioning and psychological burden. It consists of 12 items scored on a 5-point Likert scale (0–4). The items are grouped into two domains:

Scores are converted to a 0–100 scale, with higher scores indicating better quality of life. The Greek version of the questionnaire was approved by the Mapi Research Institute in 2006 to ensure conceptual equivalence.

3.4.2. OAB-V8 (Overactive Bladder Awareness Tool)

The OAB-V8 consists of 8 items scored on a 0–5 scale (0 = “not at all” and 5 = “very much”). It screens for symptoms associated with overactive bladder, including urgency, urge incontinence, daytime frequency, and nocturia. A total score ≥ 8 indicates probable overactive bladder. The validated Greek version was certified in 2005 by Corporate Translations Inc.

3.4.3. Athens Insomnia Scale (AIS)

The Athens Insomnia Scale (AIS) comprises 8 items assessing nocturnal sleep disturbance and daytime functioning. Each item is scored from 0–3 or 0–4, yielding a total score from 0–24. The first five items evaluate sleep initiation, awakenings, duration, and quality, while the last three measure fatigue, functioning, and well-being during the day. Higher scores indicate greater severity of insomnia. The AIS is validated in Greek and based on ICD-10 diagnostic criteria.

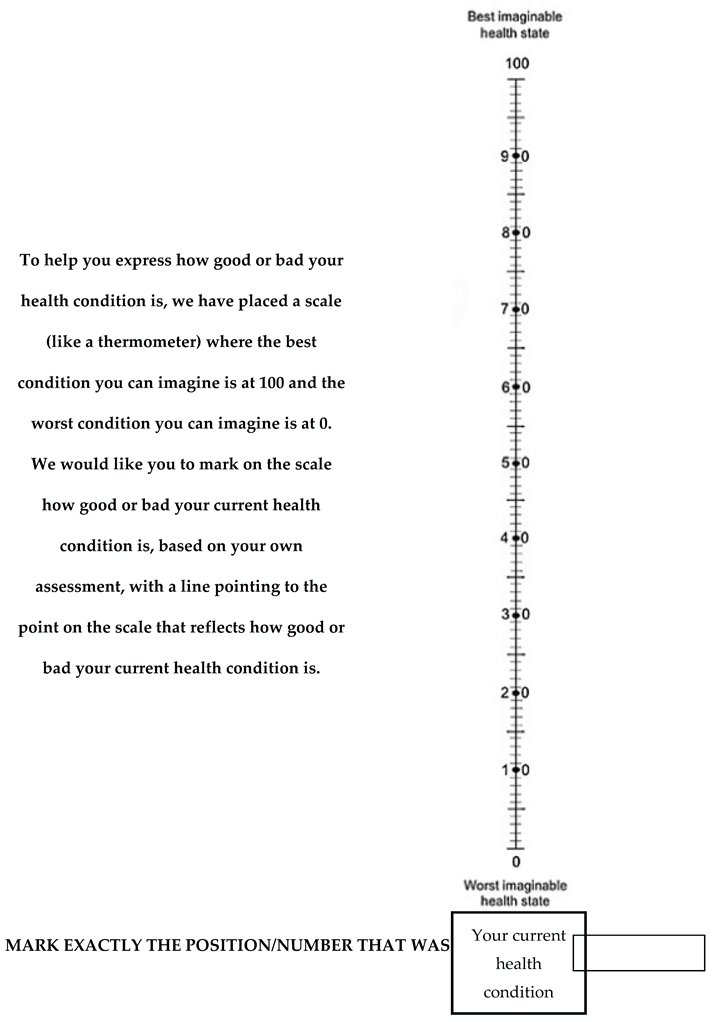

3.4.4. EQ-5D

The EQ-5D assesses health-related quality of life across five domains: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression. Each dimension is rated on a three-level scale (1 = no problem, 2 = moderate problems, 3 = severe problems), enabling 243 possible health states. Respondents also complete the EQ-VAS, a visual analogue scale rating global health from 0 (“worst imaginable health”) to 100 (“best imaginable health”). The Greek version was validated in 2001.

3.5. Ethical Considerations

The study was approved by the Scientific Committee of the General Hospital of Eastern Achaia. Participation was voluntary, and anonymity was ensured. All procedures complied with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

3.6. Objective of the Study and Hypothesis

The objective of this study was to characterize nocturia in a cohort of patients presenting to the Urology Outpatient Clinic of the General Hospital of Eastern Achaia and to examine its association with sleep quality and health-related quality of life. Rather than estimating population-level prevalence, the study reports the incidence of nocturia among clinic attendees during the study period.

A secondary objective was to evaluate the relationship between the number of nocturnal voids and patient-reported outcomes, including sleep disturbance (AIS), nocturia-related quality of life (N-QOL), and perceived health status (EQ-5D/EQ-VAS). We further explored whether demographic or clinical factors (BPH, diabetes, OAB symptoms) predicted poorer outcomes.

We hypothesized that the frequency of nocturnal awakenings would be negatively associated with quality-of-life indicators and sleep quality. Specifically, we expected individuals with more nocturia episodes to report lower N-QOL scores, greater sleep disruption on the Athens Insomnia Scale, and reduced health-related well-being on EQ-5D/EQ-VAS. We further hypothesized that clinical factors such as benign prostatic hyperplasia or symptoms of overactive bladder would be associated with poorer outcomes.

4. Statistical Analysis

Responses from all subsections of the questionnaire were initially compiled. In accordance with the scoring protocol of the OAB instrument, an additional 2 points were added to the total score of each male participant.

For the N-QOL questionnaire, two subscales were constructed:

Sleep/Energy, comprising six items related to concentration, energy, daytime sleepiness, productivity, instrumental daily activities, and sleep–wake disturbances.

Bother/Concern, comprising six items addressing concerns about water intake, disturbing others at home, awakening due to urinary urge, fear of symptom progression, apprehension regarding ineffective treatment, and general nocturia-related distress.

The following score transformations were applied:

For all scales, lower values indicated worse outcomes, while higher values reflected more favorable conditions.

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Univariate analyses were performed to examine relationships between questionnaire scores and demographic or clinical variables. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare two independent groups, whereas the Kruskal–Wallis test was applied for comparisons across more than two groups. Non-parametric tests were chosen instead of t-tests or ANOVA due to significant skewness in the distribution of scores and the relatively small sample size.

These non-parametric methods are not inferior in efficiency when normality assumptions are violated and show only limited loss of efficiency when the distribution is normal. Categorical variables, expressed as percentages, were compared using the Mantel–Haenszel chi-square test for linear trend or Pearson’s chi-square (χ²). Fisher’s exact test was employed when expected cell counts were fewer than five. Spearman rank correlation coefficients were calculated to assess associations between quantitative variables.

Distributional assumptions were examined and the scale variables demonstrated marked skewness. Given the non-normality of the data and the limited sample size, non-parametric methods were applied throughout the analysis. Independent group comparisons were performed using the Mann–Whitney U or Kruskal–Wallis test, while correlations between quantitative variables were evaluated using Spearman rank coefficients.

Univariate analyses were used to explore the effect of individual parameters, followed by multivariable regression models to evaluate the independent influence of these variables while controlling for potential confounders. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. All analyses were performed using SAS statistical software, version 9.3.

5. Results

The study was conducted between November 2013 and May 2014 and included 89 participants with a mean age of 68.6 years. All individuals attended the regular morning Urology Outpatient Clinic of the General Hospital of Eastern Achaia, which operates twice weekly. Participants were enrolled if nocturia was either their primary complaint or part of a broader clinical presentation. Given the exploratory nature of this study and the limited literature on nocturia in Greek clinical populations, item-level distributions from all validated instruments are reported to provide greater transparency and allow a detailed interpretation of patient-reported symptom burden and functional impact.

A statistically significant age difference was observed between male and female participants (p < 0.0001). The mean age of men was 70.6 ± 9.21 years, whereas that of women was 54.1 ± 15.6 years. Among women, 63.6% were younger than 60 years, while 76.9% of men were between 60 and 79 years of age. Additionally, 15.7% of participants were older than 80 years, almost exclusively men (

Table 5).

Most individuals were married and had two children (47.19%). The majority were unemployed (75.3%), and 70.8% had primary-level education. These characteristics are largely attributable to the demographic composition of the clinic’s population, which predominantly consisted of retired male farmers.

Responses to the primary questionnaire item assessing nocturnal voiding frequency are presented in

Table 6. The majority of participants reported a moderate degree of nocturia, corresponding to 2–3 nighttime awakenings. A considerable proportion (21.3%) experienced severe nocturia. It is noteworthy that, although a single nocturnal void is often considered clinically insignificant, 9% of respondents—comprising exclusively individuals younger than 64 years and employed—reported being bothered by waking once to urinate. This finding highlights that even low-frequency nocturia can be perceived as distressing and lead to healthcare-seeking behavior.

Analysis of the N-QOL questionnaire responses indicated that the most prominent issue associated with nocturia was the discomfort caused by waking during the night to void (1.78 ± 0.97). This was followed by concern regarding potential symptom progression (1.71 ± 1.19), which may be compounded by anxiety about the lack of effective treatment options (1.56 ± 1.12). A similar burden was observed for reduced nocturnal sleep (1.57 ± 1.20), concern about the need to wake to urinate (1.38 ± 1.31), perceived need for daytime rest (1.35 ± 1.12), and low energy levels the following day (1.26 ± 1.14).

Additional difficulties were reported to a lesser extent, including reduced productivity (1.17 ± 1.17), impaired concentration (1.15 ± 1.17), and diminished engagement in preferred activities (0.96 ± 1.11). Less frequent concerns involved the possibility of disturbing others at home (0.66 ± 1.01) and increased attention to fluid intake (0.53 ± 0.71). These findings are summarized in

Table 7. While overall scores provide a general indication of quality of life and sleep disturbance, item-level distributions illustrate the specific domains in which nocturia affects patients, allowing clinicians to appreciate the heterogeneity of its impact.

Responses to the overactive bladder (OAB) items indicated that the greatest discomfort was associated with awakening during the night (2.55 ± 1.32) and nocturnal urination (2.53 ± 1.35), with approximately one in three participants reporting significant or very significant distress. These were followed by frequent daytime urination (1.74 ± 1.49). The remaining items reflected substantially lower levels of discomfort, with mean scores ranging from 0.70 to 0.47 (

Table 8).

The sleep questionnaire revealed that the most prominent issue was awakening during the night (1.57 ± 0.66), with 98.9% of participants reporting at least a minor disturbance. This was followed by problems related to perceived sleep quality, total sleep duration, sleep onset, and final awakening relative to the desired time. Additional difficulties included reduced well-being, daytime drowsiness, and impaired functionality the following day (

Table 9).

Finally, analysis of the health status questionnaire showed that the most frequently reported issue was anxiety/depression, affecting 61.8% of participants (0.80 ± 0.73). Substantially lower levels of concern were observed for other dimensions, including pain/discomfort (0.19 ± 0.42), mobility problems (0.13 ± 0.34), difficulties with daily activities (0.12 ± 0.33), and limitations in self-care (0.09 ± 0.29) (

Table 10).

A total of 15 out of the 243 possible EQ-5D health states were reported. The most frequent were health states 11111 (full health) and 11112 (moderate anxiety/depression), each accounting for 33.7% of participants. These were followed by state 11113 (severe anxiety/depression), observed in 12.3% of respondents. For these three states, the mean EQ-VAS scores were similar (71.3, 71.4, and 72.7, respectively). Notably, the mean EQ-5D index score was high (0.826), indicating that the majority of participants perceived themselves to be in very good overall health (

Table 11).

The potential factors that could influence quality of life and sleep among individuals reporting nocturia were examined using univariate analyses. These variables included the number of nocturia episodes, demographic characteristics (age, gender, marital status, employment status, and educational level), diabetes mellitus (DM), benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), the overactive bladder score, and daily fluid consumption (

Table 12).

The use of the Overactive Bladder questionnaire (OAB-V8) in this study served two primary purposes. First, overactive bladder syndrome has been consistently shown to be strongly associated with nocturia, as well as with impaired sleep and reduced quality of life—even among individuals who remain unaware of their condition, a phenomenon that appears to be relatively common in the Greek population. In addition, OAB is frequently linked to conditions involved in the development and pathophysiology of nocturia, such as diabetes mellitus and benign prostatic hyperplasia.

Second, the instrument was included to facilitate a general estimation of how frequently symptoms suggestive of detrusor overactivity are present among individuals with nocturia. Given the potential influence of this factor on nocturia severity, a preliminary exploratory analysis was deemed necessary. Consequently, although a univariate analysis was performed, the results are presented descriptively (

Table 12) without detailed interpretation, as further emphasis would extend beyond the scope of this study and would not meaningfully contribute to its primary research objectives.

The analysis demonstrated that an OAB-V8 score of ≥ 8 occurred more frequently with increasing age, rising from 50.0% in participants younger than 60 years to 85.7% in those aged 80 years or older (p = 0.040). A statistically significant difference was also observed with respect to educational level: individuals with basic or technical education scored ≥ 8 at rates of 66.7% and 82.3%, respectively, while only 11.1% of participants with higher education showed similarly elevated scores (p = 0.034).

Employment status also showed a statistically significant association, with 70.1% of employed individuals demonstrating OAB-V8 scores ≥ 8, compared with 45.5% of unemployed participants (p = 0.036). Although no statistically significant difference was identified with respect to gender alone, stratification by benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) status among men yielded meaningful distinctions (p = 0.001). Specifically, 87.5% of men with BPH had scores ≥ 8, compared with 45.3% of men without BPH and 72.7% of women. For the remaining parameters examined, no statistically significant associations were observed.

Univariate analysis revealed that nocturia severity had a significant impact on N-QOL scores. Mean values decreased progressively with increasing number of nocturnal awakenings, declining from 84.4 ± 13.4 among individuals who woke once to 43.8 ± 17.1 among those who woke five or more times (p < 0.0001). Similar trends were identified for the Sleep/Energy subscale (ranging from 43.0 ± 8.2 to 18.0 ± 12.2; p < 0.0001) and the Bother/Concern subscale (ranging from 41.4 ± 7.7 to 24.8 ± 6.8; p = 0.0003). Spearman correlation coefficients further supported these findings (N-QOL: r = −0.55, p < 0.0001; Sleep/Energy: r = −0.49, p < 0.0001; Bother/Concern: r = −0.57, p < 0.0001) (

Table 13).

The remaining survey data revealed that only 9 participants (10.1%) were unmarried or divorced. Approximately 70% had completed basic education, nearly 20% had received technical or vocational training, and about 10% held a higher education degree. In addition, three out of four participants were not employed, predominantly due to retirement. Based on the OAB-V8 questionnaire, 64.0% of respondents scored ≥ 8, indicating a strong likelihood of overactive bladder syndrome. Among male participants, 32 of 78 (41.0%) reported benign prostatic hyperplasia. The influence of these parameters on quality of life in individuals with nocturia was assessed using the N-QOL total score and its subcomponents (

Table 13).

No statistically significant differences were observed across the three N-QOL scales with respect to age at the 5% level, although the lowest values were recorded in individuals aged ≥ 80 years. Women showed lower scores than men on the Sleep/Energy subscale (26.3 ± 13.9 vs. 35.6 ± 12.7, p = 0.034), whereas no statistically significant differences were found between sexes for the remaining two subscales. When men were stratified according to the presence of BPH, statistically significant differences emerged across all three scales (p = 0.004 for N-QOL; p = 0.016 for Sleep/Energy; p = 0.005 for Bother/Concern). No statistically significant associations were observed with marital or employment status. Educational level, however, demonstrated a significant effect: participants with technical education had lower scores across all three scales compared with those with basic education, whereas individuals with higher education achieved the highest scores (p = 0.003 for N-QOL; p = 0.049 for Sleep/Energy; p < 0.001 for Bother/Concern) (

Table 14).

Significant differences were also observed between participants with OAB-V8 scores < 8 and those with scores ≥ 8 across all three N-QOL scales (p < 0.0001 for each). There were no statistically significant differences associated with diabetes or the use of diuretic medications.

For the Sleep scale, scores declined significantly as the number of nocturia episodes increased, from 88.0 ± 12.7 among those waking once to 42.1 ± 20.9 among those waking five or more times (p < 0.0001). The Spearman correlation coefficient confirmed this negative relationship (r = −0.63, p < 0.0001). Women generally scored lower than men (60.2 ± 25.0 vs. 75.5 ± 20.9), although the difference approached but did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.057). Stratifying men according to the presence of BPH revealed a significant difference across three categories (men without BPH: 80.6 ± 18.3; men with BPH: 68.1 ± 22.3; women: 60.2 ± 25.0; p = 0.004). The lowest scores were observed among participants aged ≥ 80 years (60.4 ± 23.2), followed by those younger than 60 (68.4 ± 23.9), a group in which women outnumbered men (7 vs. 5). The highest scores corresponded to individuals aged 60–69 and 70–79 (79.2 ± 22.5 and 75.7 ± 17.2, respectively). Participants scoring ≥ 8 on the OAB-V8 scale showed lower performance on the Sleep scale (64.8 ± 22.0 vs. 89.3 ± 8.9, p < 0.0001). The presence of anxiety/depression was also associated with reduced scores (69.5 ± 23.3 vs. 80.3 ± 17.7). No statistically significant associations were observed with other demographic or clinical variables.

For the EQ-5D index, results were broadly similar to those of the Sleep scale. The difference according to nocturia frequency was not statistically significant under the Kruskal–Wallis test (p = 0.142), although Spearman correlation indicated a weak but significant negative association (r = −0.26, p = 0.013). This discrepancy reflects the aims of the two tests: the Kruskal–Wallis test assesses differences in medians across groups, whereas the Spearman coefficient evaluates monotonic relationships across the entire distribution. Women scored lower than men overall, and this difference increased when men were stratified by BPH status (men without BPH: 0.89 ± 0.19; men with BPH: 0.82 ± 0.24; women: 0.60 ± 0.24; p = 0.001). Participants aged ≥ 80 years had the lowest EQ-5D scores (0.65 ± 0.33), followed by those < 60 years (0.72 ± 0.23), whereas individuals in the 60–69 and 70–79 age groups had the highest scores (0.87 ± 0.20 and 0.90 ± 0.15, respectively). Participants with OAB-V8 scores ≥ 8 demonstrated lower EQ-5D values (0.78 ± 0.25 vs. 0.92 ± 0.15; p = 0.011). No other demographic or clinical characteristics showed statistically significant associations with this index.

For the EQ-VAS scale, the number of nocturia episodes showed a clear effect, with scores declining from 78.1 ± 8.0 among individuals who woke once to 53.4 ± 12.7 among those who woke five or more times (p = 0.003). A significant negative correlation was also noted (r = −0.38, p = 0.0003). No statistically significant differences were found between men and women (p = 0.254) or with regard to BPH (p = 0.061). EQ-VAS declined with increasing age, from 74.7 ± 12.6 in individuals younger than 60 years to 54.6 ± 16.6 in those ≥ 80 years (p = 0.0008), with a corresponding correlation coefficient of r = −0.42 (p < 0.0001). Employment status was also associated with score differences: employed participants scored higher than unemployed individuals (76.1 ± 7.8 vs. 64.8 ± 14.4; p = 0.001). No other statistically significant associations were observed.

The Spearman correlation coefficients between the examined scales were statistically significant in all comparisons (p < 0.006). The strongest associations were observed among the Sleep/Energy, Bother/Concern, N-QOL, OAB-V8, and Athens Insomnia Scale scores, all of which demonstrated absolute correlation values greater than 0.69. In contrast, the EQ-5D and EQ-VAS scales showed weaker correlations with the other instruments (ranging from 0.33 to 0.56), and the weakest correlation was observed between EQ-5D and EQ-VAS themselves (r = 0.29) (

Table 15).

At the conclusion of the study, an exploratory analysis was conducted to determine whether nocturia and its associated parameters were related to anxiety or depressive symptoms. To this end, the final item of the last questionnaire was used, capturing the respondent’s subjective experience of anxiety and distress at the time of assessment. The findings of this analysis are presented in

Table 16.

With regard to symptoms of anxiety and depression, a borderline statistically significant difference was observed between men and women (57.7% vs. 90.9%, respectively; p = 0.046). However, this difference became borderline non-significant when men were stratified according to the presence or absence of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). No statistically significant associations were found with respect to age, marital status, educational level, employment status, nocturia frequency, diabetes, or diuretic use.

Regression analyses were performed for all outcome measures, and in the case of the N-QOL instrument, separate models were constructed for its two subscales. The analysis indicated that increasing frequency of nocturnal awakenings was associated with a reduction in overall N-QOL score (regression coefficient: −6.7, 95% CI: −10.4 to −3.1). Furthermore, individuals scoring ≥ 8 on the OAB-V8 scale demonstrated poorer N-QOL performance (regression coefficient: −17.3, 95% CI: −26.7 to −8.0) (

Table 17).

For the Sleep/Energy subscale, regression analysis demonstrated that increasing nocturia frequency was associated with a decline in performance (regression coefficient: −4.6, 95% CI: −6.8 to −2.4). Individuals with OAB-V8 scores ≥ 8 also had significantly lower Sleep/Energy scores (regression coefficient: −8.6, 95% CI: −14.4 to −2.9). In addition, women exhibited poorer performance compared with men without BPH (regression coefficient: −9.6, 95% CI: −16.7 to −2.5) (

Table 18).

A similar pattern was observed for the Bother/Concern subscale. An increase in nocturia frequency was associated with a reduction in score (regression coefficient: −2.2, 95% CI: −4.0 to −0.3). Individuals with OAB-V8 scores ≥ 8 also demonstrated poorer performance on this subscale (regression coefficient: −8.7, 95% CI: −13.6 to −3.8) (

Table 19). In contrast, participants with higher education exhibited better outcomes on the Bother/Concern scale (regression coefficient: 7.4, 95% CI: 0.6 to 14.2) (

Table 18 and

Table 19).

Regression analysis demonstrated that increasing nocturia frequency was associated with a decline in Athens Insomnia Scale scores (regression coefficient: −10.3, 95% CI: −13.8 to −6.9). Women also exhibited lower scores compared with men (regression coefficient: −13.5, 95% CI: −24.3 to −2.7). The presence of anxiety symptoms, included as an independent variable, was associated with reduced performance on the scale (regression coefficient: −7.0, 95% CI: −13.9 to −0.2). Additionally, a higher OAB-V8 score (≥ 8) was linked to a borderline statistically non-significant decline in Athens Insomnia Scale performance (regression coefficient: −8.5, 95% CI: −17.1 to 0.1) (

Table 20).

In conclusion, regression analysis of health status demonstrated that increasing nocturia frequency was associated with a reduction in EQ-5D scores, although this effect was only borderline statistically significant (regression coefficient: −0.05, 95% CI: −0.094 to −0.0001). Women also exhibited lower EQ-5D scores compared with men (regression coefficient: −0.28, 95% CI: −0.423 to −0.133). A 10-year increase in age did not reach statistical significance at the 5% level (regression coefficient: −0.073, 95% CI: −0.122 to 0.005; p = 0.073) (

Table 21).

Regression analysis of the EQ-VAS scale demonstrated that increasing nocturia frequency was associated with a reduction in self-reported health status (regression coefficient: −2.9, 95% CI: −5.4 to −0.3). A 10-year increase in age was also linked to lower EQ-VAS scores (regression coefficient: −5.4, 95% CI: −8.8 to −2.0). In contrast, being married was associated with higher perceived health (regression coefficient: 14.3, 95% CI: 5.6 to 23.1). Additionally, participants with OAB-V8 scores ≥ 8 tended to perform worse on the EQ-VAS scale (regression coefficient: −6.5, 95% CI: −12.5 to 0.4). Diabetes was also included in the model due to its known multifactorial effects on overall health status (

Table 22). These findings provide a granular perspective on the components of daily functioning most affected by nocturia, which would not be evident from total scores alone. Given the absence of standardized Greek tools for nocturia evaluation, the item-level analysis provides valuable clinical information that may assist practitioners in understanding patient perceptions and priorities.

6. Discussion

Nocturia represents a common lower urinary tract symptom that adversely affects sleep and quality of life, particularly among older adults. Despite its clinical relevance, relatively few studies have examined its impact on patient-reported quality of life outcomes. The present study aimed to highlight the burden of nocturia and investigate its association with sleep quality and overall well-being in affected individuals. The present study demonstrates a clear, dose-dependent relationship between the frequency of nocturia episodes and deterioration in patient-reported outcomes. Specifically, increasing nocturnal voiding was associated with poorer nocturia-specific quality of life, greater sleep disturbance, and reduced perceived health status. These findings are consistent with previous research showing that nocturia is one of the most disruptive lower urinary tract symptoms and is strongly associated with impaired daily functioning and reduced subjective well-being [

1,

2,

3].

Several limitations should be acknowledged. The primary challenge derives from the characteristics of the rural Greek population, where individuals—especially women—are less likely to seek medical consultation for urological symptoms. The small sample size of 89 participants, combined with the limited time frame of data collection and the operational constraints of a morning outpatient clinic, restricts generalizability. Furthermore, the underrepresentation of women hinders meaningful conclusions regarding the broader female population. As many women preferentially consult gynecologists for urinary complaints, cases may remain undocumented in urology clinics. Additionally, cultural factors, embarrassment, and health literacy barriers may further discourage rural women from seeking specialist care. Most female participants in this study were younger, employed, and resided in urban areas. Lastly, nocturia is often underappreciated as a clinical concern and may not prompt individuals to seek care, potentially influencing the sample composition.

An interesting observation is that daily fluid intake did not demonstrate a statistically significant association with nocturia severity or any of the related clinical scales. Consequently, it was not included in the regression analyses. This finding may reflect seasonal variation, as the study was conducted during winter months, when fluid consumption typically decreases. Similarly, neither diuretic use nor diabetes showed a significant effect on the reported indicators. This is noteworthy given the established association between poorly controlled type II diabetes and nocturia [

57].

In the international literature, Bing et al. examined the causes of nocturia in males aged 60–80 years and found that multiple comorbidities—including hypertension, diabetes, heart failure, and neurological disorders—did not significantly differ in frequency between patients with and without nocturia [

58]. These findings align with the current study, suggesting that nocturia cannot be explained solely by underlying systemic disease.

Sleep disruption represents a central mechanism linking nocturia to broader impairment. Fragmented sleep is associated with reduced REM sleep, decreased deep sleep phases, and increased sleep latency upon reawakening. Previous studies have shown that nocturia contributes to sleep fragmentation in up to 75% of older adults, leading to daytime somnolence, mood instability, and increased risk of falls [

6,

20,

21]. Our findings are consistent with this evidence, as participants with more frequent nocturnal awakenings consistently reported poorer sleep quality.

The findings of the present research clearly demonstrate a dose-dependent relationship between nocturia frequency and all evaluated outcomes. As the number of nighttime voids increased, sleep quality, quality of life, and general health perception deteriorated. These results support the validity of the instruments employed. Regression analysis indicated that each additional nocturia episode reduced the overall N-QOL score by 6.7 (95% CI: −10.4 to −3.1). Participants reporting a single nocturnal void had a mean score of 84.4 ± 13.4, whereas those reporting four episodes demonstrated a markedly lower score of 56 ± 19.7, indicating substantial impairment in daily functioning. These results are consistent with large clinical and epidemiological studies showing that two or more nightly awakenings are typically perceived as highly disruptive by patients [

1,

59,

60]. The association between nocturia frequency and reduced N-QOL scores aligns with large-scale international surveys, which similarly report that two or more nocturnal awakenings are perceived as clinically disruptive [

59,

60]. In these studies, patients frequently describe reduced vitality, daytime fatigue, and limitations in social or occupational functioning. Our finding that each additional nocturnal void is associated with a measurable decline in quality of life further reinforces the clinical relevance of nocturia, even when not accompanied by other lower urinary tract symptoms.

Comparable patterns were observed for both the EQ-5D and EQ-VAS measures. Interestingly, for EQ-VAS, nocturia frequency was not the strongest predictor of lower perceived health; marital status and age demonstrated more pronounced effects. This may be explained by the subjective nature of the EQ-VAS, which evaluates current perceived health rather than nocturia-related functional impairment. Older age typically reflects a greater burden of comorbidities, which may negatively influence global health perception. While a systematic review has shown age to be the strongest predisposing factor for nocturia—impairing sleep and quality of life in both sexes through hormonal changes and lower urinary tract aging [

61]—the present study did not confirm such findings. Age differences in univariate analyses achieved only borderline significance, with poorer outcomes seen primarily in individuals over 80 years. In multivariate models, age was generally not a significant predictor. This may reflect insufficient statistical power due to sample size. Additionally, nocturia is a poorly discriminated symptom; it remains unclear in many cases whether individuals wake to void, or merely void once awakened for other reasons. The deterioration observed in EQ-5D and EQ-VAS scores reflects a broader perception of compromised daily functioning. Importantly, this result does not imply formal psychiatric morbidity; rather, it suggests that recurrent interruptions of sleep can trigger discomfort, decreased energy, and heightened concern about one’s health status. Similar patterns have been described in population-based studies in which individuals with chronic nocturia report worse subjective health despite similar comorbidity profiles [

22,

23,

24].

Gender differences in nocturia are often insufficiently recognized in published research. Although both sexes experience nocturia, underlying etiologies may diverge. In men, benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is a well-established contributor, whereas in women, reproductive history, childbirth trauma, and hormonal fluctuations—especially after menopause—play important roles. In most epidemiological studies, nocturia prevalence in men exceeds that in women across age groups [

61]. For example, Chartier-Kastler et al. demonstrated profound sleep disruption among men with BPH, including increased insomnia [

62]. Conversely, Choo et al. found that women aged 18–49 had a higher prevalence of nocturia than men, with a three-fold increase among women aged 18–29 [

63].

In the present study, the small number of female participants precludes reliable subgroup analysis. Notably, women consistently scored lower across all scales than men. To account for disease-specific burden, men were stratified based on the presence or absence of BPH. The rationale is sound, as nocturia is a primary symptom of BPH and is known to negatively impact quality of life. Sarikaya et al. reported reduced sleep duration and increased daytime somnolence among BPH patients [

64]. Surprisingly, although a large proportion of affected individuals in this study reported BPH, regression analysis did not reveal sustained statistical significance. This may reflect the use of non-BPH men as the reference category, the masking effect of confounders, or underreporting of symptoms, particularly in older men.

No other demographic variables demonstrated consistent associations with the evaluated scales. Notably, individuals with technical education performed worse on the N-QOL scale, whereas married participants reported better global health status. Social dynamics may explain this observation: in Greek society, individuals with familial obligations may neglect personal health due to occupational and domestic responsibilities, whereas those living alone may adopt heightened vigilance or exaggerate symptom burden.

With respect to overactive bladder, the OAB-V8 questionnaire was initially employed in an exploratory capacity. Nevertheless, meaningful insights emerged, particularly the finding that 64% of respondents scored ≥ 8, strongly suggestive of OAB. Overactive bladder remains significantly underrecognized by both the general public and healthcare providers. Its prevalence is likely considerably higher than reported, as it is typically investigated only in the presence of pronounced urgency or urge incontinence. Increased awareness and routine screening may therefore be warranted. Regarding nocturia, the findings confirm its multidimensional impact on quality of life and sleep, with worsening symptoms intensifying nocturnal awakenings. The strong association between elevated OAB-V8 scores and poorer quality-of-life outcomes is expected, given the shared pathophysiological pathways between detrusor overactivity and nocturnal voiding. Symptoms such as urgency and frequent daytime urination indicate altered bladder storage capacity, predisposing individuals to awaken overnight. Previous research has highlighted that untreated or unrecognized OAB contributes to both nocturia prevalence and symptom severity [

41,

42]. In our population, two-thirds of patients exceeded the screening threshold, reinforcing the need for earlier identification and regular assessment.

Another noteworthy observation is the lack of studies linking nocturia to anxiety and psychosomatic disorders in the international literature. In the present study, only the sleep questionnaire demonstrated a meaningful correlation with anxiety, likely reflecting the well-established association between sleep disturbances and anxiety disorders. Most participants described their anxiety as moderate, which is unsurprising given prevailing socioeconomic stressors. Importantly, 38.2% reported no anxiety at all, and only two reported severe distress.

The pathophysiology of nocturia is multifactorial. This complexity likely contributes to insufficient recognition of nocturia as an independent clinical disorder. Underlying mechanisms may be urological or systemic, and can vary substantially between individuals. Inadequate assessment can lead to suboptimal treatment and unfavorable therapeutic outcomes. Nocturia alone has been associated with reduction in 14 of the 15 dimensions of health-related quality of life scales, worsening proportionally with each additional nocturnal episode. The symptom affects adults of all ages, but younger individuals may experience a disproportionately negative impact due to occupational and caregiving responsibilities. Given its diverse etiologies and complex management, additional targeted research—particularly in Greece—is needed to better characterize its burden and establish effective intervention strategies. Taken together, these findings demonstrate that nocturia is not only a urological symptom but a multidimensional clinical burden. Its impact arises from both direct interruption of sleep and secondary consequences such as reduced vitality, decreased productivity, and persistent concern about bodily function. Understanding nocturia from the patient’s perspective therefore offers valuable insight into treatment priorities and may guide more patient-centered management strategies.

7. Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, its cross-sectional design prevents the establishment of causal relationships between nocturia and the examined clinical, psychological, or quality-of-life measures. The relatively small sample size (n = 89) further limits the statistical power of subgroup analyses and may increase the likelihood of type II error, particularly in comparisons involving women and older age groups. Additionally, the study population was drawn from a single outpatient urology clinic, which may not be representative of the wider Greek population. The predominance of retired male patients and the underrepresentation of women, particularly those from rural areas, may introduce selection bias and restrict the generalizability of the findings. The absence of exclusion criteria may have allowed confounding factors such as concurrent medical conditions, psychological stress, or medication use to influence symptom severity, but this reflects the real-world clinical burden of nocturia in our patient population.

Second, the assessment of nocturia relied on self-reported data without confirmation through objective measurements such as frequency–volume charts, voiding diaries, or polysomnography. This introduces a potential recall bias and limits the ability to discriminate between nocturnal awakenings caused by urinary urgency and those attributable to unrelated sleep disturbances. The reliance on a single-item measure to assess anxiety and emotional distress constitutes another limitation, as it cannot capture the full clinical spectrum of psychological conditions such as generalized anxiety disorder or depression.

Third, the use of translated and culturally adapted questionnaires, although validated, may still introduce nuances in interpretation that differ from their original versions. The absence of formally validated Greek questionnaires specifically designed to assess nocturia further complicates the evaluation, potentially affecting the precision of results.

Finally, the study was conducted during winter months, which may have influenced fluid intake patterns and nocturnal behavior, limiting the ecological validity of the findings. Longer observational periods and more diverse seasonal data would likely yield a more accurate representation of nocturia patterns and their impact on daily functioning.

8. Future Directions

Future research should build upon these findings by examining nocturia in larger and more diverse populations using multicenter or population-based sampling. Longitudinal designs would allow for a clearer understanding of the causal relationship between nocturnal voiding, sleep disruption, and quality of life, and would help distinguish whether nocturia is a direct driver of psychological burden or a consequence of other age-related comorbidities. Incorporating objective measures of sleep, such as actigraphy or polysomnography, alongside validated patient-reported outcomes could provide a more nuanced picture of the physiological and behavioral mechanisms that link nocturia to functional impairment.

In addition, future studies should explore the contribution of modifiable factors—such as hydration habits, medication use, or management of overactive bladder symptoms—and the interaction between nocturia and systemic conditions like diabetes or cardiovascular disease. Interventional research aimed at reducing nocturia episodes, improving sleep continuity, or enhancing patient awareness may help identify effective treatment strategies that address both clinical symptoms and quality-of-life domains. Ultimately, more comprehensive approaches that integrate urological, sleep medicine, and psychosocial perspectives are needed to improve care for individuals affected by nocturia.

9. Conclusion

Nocturia is a common and multifactorial condition that significantly impairs sleep quality, daily functioning, and overall well-being. Our findings show a clear dose-dependent relationship between the number of nocturnal awakenings and deterioration in quality-of-life measures, with overactive bladder contributing notably to this burden. Despite its prevalence, nocturia is often underestimated by patients and clinicians, leading to delayed diagnosis and suboptimal management. Recognizing nocturia as more than a benign consequence of aging is essential, and a comprehensive clinical approach that incorporates urinary symptoms, comorbidities, sleep disturbances, and psychosocial factors is required. These findings reinforce that nocturia has a measurable and cumulative effect on individuals’ daily functioning. Rather than reflecting background demographic or comorbid characteristics, the burden of nocturia is primarily linked to the frequency of night-time awakenings. Further research in larger and more diverse populations is needed to better characterize the condition and to guide targeted interventions aimed at improving patient outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.L, D.L and I.M; Methodology, T.V, F.M, A.A, P.D.P, E.L, I.M and G.T; Software, V.L and E.S; Validation, F.M, A.A, D.L, E.L, I.M and G.T; Formal analysis, F.M, V.L, E.S, D.L and P.D.P; Investigation, T.V, F.M, V.L and G.T; Resources, E.S, A.A, D.L, P.D.P and E.L; Data curation, F.M, E.S, D.L, P.D.P and G.T; Writing – original draft, T.V, F.M, E.S, A.A, D.L and P.D.P; Writing – review & editing, T.V, F.M, V.L, E.L, I.M and G.T; Visualization, F.M, V.L, P.D.P and G.T; Supervision, F.M, E.L, I.M and G.T; Project administration, T.V, F.M and D.L; Funding acquisition, E.S, A.A, E.L and G.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of the General Hospital of Eastern Achaia (No. ES29 06-06-2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix

QUESTIONNAIRE

Full Name:

Age: Gender: Dateofbirth:

Marital Status: Single ?Married?Divorced?

Number of Children:

Education Level:

No education

Primary education

Technical School

University

Master’s degree

Other:

Occupation:

Unemployed

Retired

Farmer

Public Sector Employee

Private Sector Employee

Self-employed

Other:

Health conditions/issues:

Medication:

Dailyfluidintake:

In the last month, how many times did you usually need to get up to urinate from the moment you went to bed until the moment you woke up in the morning?

☐ None

☐ Once

☐ Twice

☐ Three times

☐ Four times

☐ Five or more times

In the last 15 days, the fact that I had to get up during the night to urinate:

-

It made it difficult for me to concentrate the next day

☐ Every day ☐ Most days ☐ Some days ☐ Rarely ☐ Never

-

Made me feel generally low on energy the next day

☐ Every day ☐ Most days ☐ Some days ☐ Rarely ☐ Never

-

Made me feel the need to sleep during the day

☐ Every day ☐ Most days ☐ Some days ☐ Rarely ☐ Never

-

Made me less productive the next day

☐ Every day ☐ Most days ☐ Some days ☐ Rarely ☐ Never

-

Forced me to engage less in activities I enjoy

☐ Every day ☐ Most times ☐ Sometimes ☐ Rarely ☐ Never

-

Made me pay attention to when and how much I drink

☐ Every day ☐ Most times ☐ Sometimes ☐ Rarely ☐ Never

-

Caused me trouble sleeping enough at night

☐ Every night ☐ Most nights ☐ Some nights ☐ Rarely ☐ Never

-

It made me worry I was disturbing others at home because I had to get up at night to urinate

☐ To an excessive degree ☐ To a large degree ☐ To a moderate degree ☐ To a small degree ☐ Not at all

-

Made me worry about having to get up at night to urinate

☐ Constantly ☐ Most of the time ☐ Sometimes ☐ Rarely ☐ Never

-

Made me worry that this condition would worsen in the future

☐ To an excessive degree ☐ To a large degree ☐ To a moderate degree ☐ To a small degree ☐ Not at all

-

Made me worry that there is no effective treatment for this condition (having to get up at night to urinate)

☐ To an excessive degree ☐ To a large degree ☐ To a moderate degree ☐ To a small degree ☐ Not at all

-

Overall, how bothersome was it to have to get up at night to urinate during the last 15 days?

☐ Not at all ☐ To a small degree ☐ To a moderate degree ☐ To a large degree ☐ To an excessive degree

How bothered have you been by:

-

Frequent urination during the day

☐ Not at all ☐ Slightly ☐ A little ☐ Quite a bit ☐ Very much ☐ Extremely

-

Unpleasant urge to urinate

☐ Not at all ☐ Slightly ☐ A little ☐ Quite a bit ☐ Very much ☐ Extremely

-

Sudden urge to urinate with little or no warning

☐ Not at all ☐ Slightly ☐ A little ☐ Quite a bit ☐ Very much ☐ Extremely

-

Unexpected loss of a small amount of urine

☐ Not at all ☐ Slightly ☐ A little ☐ Quite a bit ☐ Very much ☐ Extremely

-

Nighttime urination

☐ Not at all ☐ Slightly ☐ A little ☐ Quite a bit ☐ Very much ☐ Extremely

-

Waking up during the night because you had to urinate

☐ Not at all ☐ Slightly ☐ A little ☐ Quite a bit ☐ Very much ☐ Extremely

-

Uncontrollable urge to urinate

☐ Not at all ☐ Slightly ☐ A little ☐ Quite a bit ☐ Very much ☐ Extremely

-

Loss of urine associated with a strong urge to urinate

☐ Not at all ☐ Slightly ☐ A little ☐ Quite a bit ☐ Very much ☐ Extremely

At least 3 days a week on average in the last month, one or more of the following occurred:

-

Sleep onset

☐ Very fast ☐ Slightly delayed ☐ Delayed ☐ Very delayed or did not sleep at all

-

Awakenings during the night

☐ No problem ☐ Minor problem ☐ Moderate problem ☐ Severe problem or did not sleep at all

-

Final awakening compared to the desired time

☐ At the desired time ☐ Slightly earlier ☐ Quite earlier ☐ Much earlier or did not sleep at all

-

Total sleep duration

☐ Adequate ☐ Rather inadequate ☐ Inadequate ☐ Very inadequate or did not sleep at all

-

Sleep quality

☐ Satisfactory ☐ Moderate ☐ Unsatisfactory ☐ Poor

-

Well-being the next day

☐ Fully ☐ Slightly reduced ☐ Quite reduced ☐ Very reduced or absent

-

Functionality the next day

☐ Full ☐ Slightly reduced ☐ Quite reduced ☐ Very reduced or absent

-

Sleepiness the next day

☐ None ☐ Mild ☐ Moderate ☐ Severe

Which of the following statements best describes your current health condition?

- a)

I havenoproblemswalking

- b)

I havesomeproblemswalking

- c)

I ambedridden

- 2.

Self-care

- a)

I have no problems with self-care

- b)

I have some problems with washing and dressing

- c)

I am unable to wash or dress myself

- 3.

Daily Activities (e.g., work, studies, household chores, family or social activities)

- a)

I have no problems performing my usual activities

- b)

I have some problems performing my usual activities

- c)

I am unable to perform my usual activities

- 4.

Pain / Discomfort

- a)

I feel no pain or discomfort

- b)

I feel moderate pain or discomfort

- c)

I feel excessive pain or discomfort

- 5.

Anxiety / Depression

- a)

I feel no anxiety or depression

- b)

I feel moderate anxiety or depression

- c)

I feel excessive anxiety or depression

- 6.

Compared to my health condition over the past 12 months, my current condition is

- a)

Better

- b)

The same

- c)

Worse

References

- Leslie SW, Sajjad H, Singh S. Nocturia. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 [cited 2025 Feb 10]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK518987/.

- Olsson LE, Johansson M, Zackrisson B, Blomqvist LK. Basic concepts and applications of functional magnetic resonance imaging for radiotherapy of prostate cancer. Phys Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2019 Feb 25;9:50–7. [CrossRef]

- Aucar N, Fagalde I, Zanella A, Capalbo O, Aroca-Martinez G, Favre G, et al. Nocturia: its characteristics, diagnostic algorithm and treatment. Int Urol Nephrol. 2023 Jan 1;55(1):107–14. [CrossRef]

- Furtado D. Nocturia × disturbed sleep: a review. International Urogynecology Journal [Internet]. 2011 Jan 1 [cited 2025 Feb 10]; Available from: https://www.academia.edu/126357006/Nocturia_disturbed_sleep_a_review.

- Ong LM, Chan JMF, Koh GEMY, Gopal PEW, Leow EHM, Ng YH. Approach to nocturnal enuresis in children. Singapore Med J. 2024 Apr 23;65(4):242–8. [CrossRef]

- Duffy JF, Scheuermaier K, Loughlin KR. Age-Related Sleep Disruption and Reduction in the Circadian Rhythm of Urine Output: Contribution to Nocturia? Curr Aging Sci. 2016;9(1):34–43. [CrossRef]

- Zumrutbas AE, Bozkurt AI, Alkis O, Toktas C, Cetinel B, Aybek Z. The Prevalence of Nocturia and Nocturnal Polyuria: Can New Cutoff Values Be Suggested According to Age and Sex? Int Neurourol J. 2016 Dec;20(4):304–10. [CrossRef]

- Lombardo R, Tubaro A, Burkhard F. Nocturia: The Complex Role of the Heart, Kidneys, and Bladder. Eur Urol Focus. 2020 Dec 15;6(3):534–6. [CrossRef]

- Ridgway A, Cotterill N, Dawson S, Drake MJ, Henderson EJ, Huntley AL, et al. Nocturia and Chronic Kidney Disease: Systematic Review and Nominal Group Technique Consensus on Primary Care Assessment and Treatment. European Urology Focus. 2022 Jan 1;8(1):18–25. [CrossRef]

- Kass-Iliyya A, Hashim H. Nocturnal polyuria: Literature review of definition, pathophysiology, investigations and treatment. Journal of Clinical Urology [Internet]. 2018 Feb 22 [cited 2025 Feb 6]; Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/2051415818756792?journalCode=urob . [CrossRef]

- Tyagi S, Chancellor MB. Nocturnal polyuria and nocturia. Int Urol Nephrol. 2023 Jun;55(6):1395–401. [CrossRef]

- Robinson D, Suman S. Managing nocturia: The multidisciplinary approach. Maturitas. 2018 Oct 1;116:123–9. [CrossRef]

- Smith M, Dawson S, Andrews RC, Eriksson SH, Selsick H, Skyrme-Jones A, et al. Evaluation and Treatment in Urology for Nocturia Caused by Nonurological Mechanisms: Guidance from the PLANET Study. European Urology Focus. 2022 Jan 1;8(1):89–97. [CrossRef]

- Oelke M, De Wachter S, Drake MJ, Giannantoni A, Kirby M, Orme S, et al. A practical approach to the management of nocturia. Int J Clin Pract. 2017 Nov;71(11):e13027.

- Jimenez-Cidre MA, Lopez-Fando L, Esteban-Fuertes M, Prieto-Chaparro L, Llorens-Martinez FJ, Salinas-Casado J, et al. The 3-day bladder diary is a feasible, reliable and valid tool to evaluate the lower urinary tract symptoms in women. Neurourol Urodyn. 2015 Feb;34(2):128–32. [CrossRef]

- Cameron AP, Wiseman JB, Smith AR, Merion RM, Gillespie BW, Bradley CS, et al. Are Three-Day Voiding Diaries Feasible and Reliable? Results from the Symptoms of Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction Research Network (LURN) Cohort. Neurourol Urodyn. 2019 Nov;38(8):2185–93. [CrossRef]

- Tsou YA, Chou ECL, Shie DY, Lee MJ, Chang WD. Polysomnography and Nocturia Evaluations after Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty for Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome. J Clin Med. 2020 Sep 25;9(10):3089. [CrossRef]

- Lu CH, Chang HM, Chang KH, Ou YC, Hsu CY, Tung MC, et al. Effect of nocturia in patients with different severity of obstructive sleep apnea on polysomnography: A retrospective observational study. Asian Journal of Urology. 2024 Jul 1;11(3):486–96. [CrossRef]

- Papworth E, Dawson S, Henderson EJ, Eriksson SH, Selsick H, Rees J, et al. Association of Sleep Disorders with Nocturia: A Systematic Review and Nominal Group Technique Consensus on Primary Care Assessment and Treatment. Eur Urol Focus. 2022 Jan 1;8(1):42–51. [CrossRef]

- Madan Jha V. The prevalence of sleep loss and sleep disorders in young and old adults. Aging Brain. 2023 Jan 1;3:100057.

- Pilcher JJ, Morris DM. Sleep and Organizational Behavior: Implications for Workplace Productivity and Safety. Front Psychol [Internet]. 2020 Jan 31 [cited 2025 Feb 12];11. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00045/full . [CrossRef]

- Bliwise DL, Wagg A, Sand PK. Nocturia: A Highly Prevalent Disorder With Multifaceted Consequences. Urology. 2019 Nov 1;133:3–13. [CrossRef]

- Moon S, Kim YJ, Chung HS, Yu JM, Park II, Park SG, et al. The Relationship Between Nocturia and Mortality: Data From the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Int Neurourol J. 2022 Jun;26(2):144–52. [CrossRef]

- Lightner DJ, Krambeck AE, Jacobson DJ, McGree ME, Jacobsen SJ, Lieber MM, et al. Nocturia is associated with an increased risk of coronary heart disease and death. BJU Int. 2012 Sep;110(6):848–53.

- Kulakaç N, Sayılan AA. Determining the quality of life and the sleep quality in patients with benign prostate hyperplasia. International Journal of Urological Nursing. 2020;14(1):13–7. [CrossRef]

- Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms, Sexual Function, and the Quality of Life of Married Women with Urinary Incontinence [Internet]. [cited 2025 Feb 12]. Available from: http://ouci.dntb.gov.ua/en/works/7XgMarX9/.

- Miotła P, Dobruch J, Lipiński M, Drewa T, Kołodziej A, Barcz E, et al. Diagnostic and therapeutic recommendations for patients with nocturia. Cent European J Urol. 2017;70(4):388–93. [CrossRef]

- Aydin Sayilan A, Kulakac N. The effect of transurethral resection of the prostate on sexual life quality in patient spouses. International Journal of Urological Nursing. 2024;18(1):e12384.

- Andersson F, Anderson P, Holm-Larsen T, Piercy J, Everaert K, Holbrook T. Assessing the impact of nocturia on health-related quality-of-life and utility: results of an observational survey in adults. Journal of Medical Economics. 2016 Dec 1;19(12):1200–6. [CrossRef]

- Spencer A, Rivero-Arias O, Wong R, Tsuchiya A, Bleichrodt H, Edwards RT, et al. The QALY at 50: One story many voices. Social Science & Medicine. 2022 Mar 1;296:114653. [CrossRef]

- Van Wilder L, Devleesschauwer B, Clays E, Van der Heyden J, Charafeddine R, Scohy A, et al. QALY losses for chronic diseases and its social distribution in the general population: results from the Belgian Health Interview Survey. BMC Public Health. 2022 Jul 7;22:1304. [CrossRef]

- Nigro N, Grossmann M, Chiang C, Inder WJ. Polyuria-polydipsia syndrome: a diagnostic challenge. Intern Med J. 2018 Mar;48(3):244–53. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Guerrero G, Müller-Ortiz H, Pedreros-Rosales C. Polyuria in adults. A diagnostic approach based on pathophysiology. Revista Clínica Española (English Edition). 2022 May 1;222(5):301–8.

- Refardt J. Diagnosis and differential diagnosis of diabetes insipidus: Update. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020 Sep;34(5):101398. [CrossRef]

- Robertson GL. Diabetes insipidus: Differential diagnosis and management. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016 Mar;30(2):205–18. [CrossRef]

- Weiss JP, Monaghan TF, Epstein MR, Lazar JM. Future Considerations in Nocturia and Nocturnal Polyuria. Urology. 2019 Nov 1;133:34–42. [CrossRef]

- Sinha S, Cameron AP, Tse V, Panicker J. Storage-dominant lower urinary tract symptoms in the older male: Practical approach, guidelines recommendations and limitations of evidence. Continence. 2024 Sep 1;11:101320. [CrossRef]

- Bladder Dysfunction: Practice Essentials, Pathophysiology, Etiology. 2024 Dec 23 [cited 2025 Feb 10]; Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/321273-overview?form=fpf.

- Mayo Clinic [Internet]. [cited 2025 Feb 10]. Overactive bladder - Symptoms and causes. Available from: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/overactive-bladder/symptoms-causes/syc-20355715.

- Singam P, Hong GE, Ho C, Hee TG, Jasman H, Inn FX, et al. Nocturia in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia: evaluating the significance of ageing, co-morbid illnesses, lifestyle and medical therapy in treatment outcome in real life practice. The Aging Male. 2015 Apr 3;18(2):112–7. [CrossRef]

- Bekou E, Mulita A, Seimenis I, Kotini A, Courcoutsakis N, Koukourakis MI, et al. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Techniques for Post-Treatment Evaluation After External Beam Radiation Therapy of Prostate Cancer: Narrative Review. Clinics and Practice. 2025 Jan;15(1):4. [CrossRef]

- Abu Mahfouz I, Asali F, Abdel-Razeq R, Ibraheem R, Abu Mahfouz S, Jaber H, et al. Bladder sensations in women with nocturia due to overactive bladder syndrome. Int Urogynecol J. 2020 May 1;31(5):1041–8. [CrossRef]