Submitted:

09 January 2026

Posted:

12 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

3. Methodology

3.1. Purpose and Design of Study

3.2. Data and Sources

| Variable | Description | Source | Expected impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| EXPVALUE | Export size (log version) | UN Comtrade | Target variable |

| GDPexp, GDPimp | GDP of exporting and importing countries | World Bank (WDI) | (+) |

| Distance | Distance between two countries (km) | CEPII | (–) |

| LPIEXP, LPIIMP | Logistics index (exporter, importer) | World Bank (LPI) | (+) |

| ASEAN, EAEU, APTA, NEA | Institutional and regional integration variables | WTO, FTU | (+) |

| TWPHASE1, TWPHASE2 | Phases of the US-China trade war | IMF, WTO | (–) |

| TariffRate, REER | Tariff level and real exchange rate | UNCTAD, IMF | (±) |

3.3. Theoretical Basis of the Model

3.4. Statistical Methods and Interaction Analysis

| Method | Purpose of use | Theoretical and practical basis |

| OLS (log–log regression) | Baseline assessment | Easily interpretable, flexible, and able to detect the direction of correlation (Head & Mayer, 2014) |

| PPML (Poisson Pseudo Maximum Likelihood) | Main assessment method | “Zero trade flow”, commonly used to correct heteroskedasticity problems (Santos Silva & Tenreyro, 2006) |

| Negative Binomial (NB) | Control overdispersion | More suitable in the case of variance > mean (Cameron & Trivedi, 2010) |

| Poisson GLM (Fixed Effects) | Verification | Reduce unobserved differences by controlling for cross-country and time fixed effects. |

| Research question | Method used | Relationship under review |

| 1. What are the determinants of export performance? | OLS, PPML | GDP, Distance, REER |

| 2. What are the logistical and institutional implications? | PPML, NB | LPIEXP, LPIIMP, ASEAN, EAEU |

| 3. What are the moderating effects of the phases of the trade war? | PPML + Interaction Terms | TWPHASE1, TWPHASE2 × EAEU |

4. Result

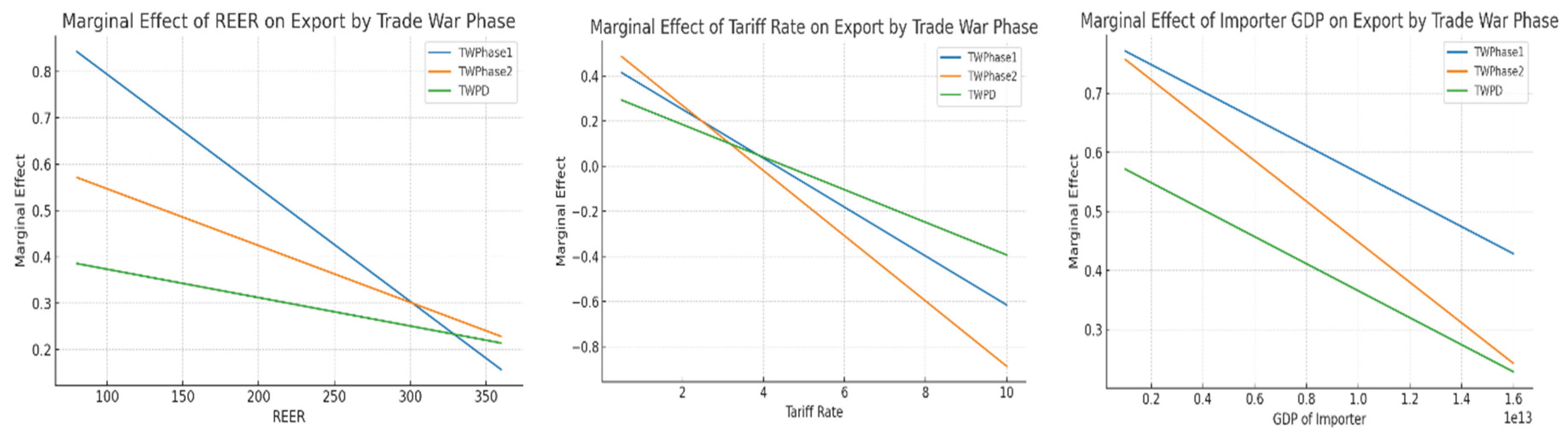

4.1. Annual Export Changes and the Impact of External Shocks

4.2. Estimation Results of the Baseline Gravity Model

4.3. Estimation Results of the Augmented Gravity Model

| Variables | Negative Binomia | Poisson GLM | Poisson QML + FE | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | p-value | Coefficient | p-value | Coefficient | p-value | |

| C | -17.714 | 0.000 *** | -18.357 | 0.000 *** | -17.352 | 0.000 *** |

| LOG(GDPEX) | 1.011 | 0.000 *** | 1.004 | 0.000 *** | 0.980 | 0.000 *** |

| LOG(GDPIMP) | 0.263 | 0.000 *** | 0.367 | 0.000 *** | 0.394 | 0.000 *** |

| LOG(DISTANCE) | -1.167 | 0.000 *** | -0.886 | 0.000 *** | -0.917 | 0.000 *** |

| BORDER | 0.344 | 0.000 *** | -0.041 | 0.000 *** | -0.181 | 0.000 *** |

| COMLANG | 0.259 | 0.074 * | 0.248 | 0.001 *** | 0.190 | 0.000 *** |

| LOG(LPIEXP) | 4.653 | 0.000 *** | 2.204 | 0.000 *** | 2.249 | 0.000 *** |

| LOG(LPIIMP) | 3.004 | 0.036 ** | 1.644 | 0.000 *** | 1.201 | 0.000 *** |

| TARIFFRATE | -0.034 | 0.006 *** | -0.084 | 0.000 *** | -0.088 | 0.000 *** |

| TWPHASE1 | -0.196 | 0.097 * | -0.025 | 0.000 *** | -0.026 | 0.000 *** |

| TWPHASE2 | -0.228 | 0.054 * | -0.081 | 0.000 *** | -0.078 | 0.000 *** |

| NEA | 1.057 | 0.000 *** | 0.690 | 0.000 *** | 0.721 | 0.000 *** |

| TWPD × EAEU | -0.585 | 0.084 * | -0.323 | 0.000 *** | -0.302 | 0.000 *** |

| @CROSSID | -0.004 | 0.000 *** | ||||

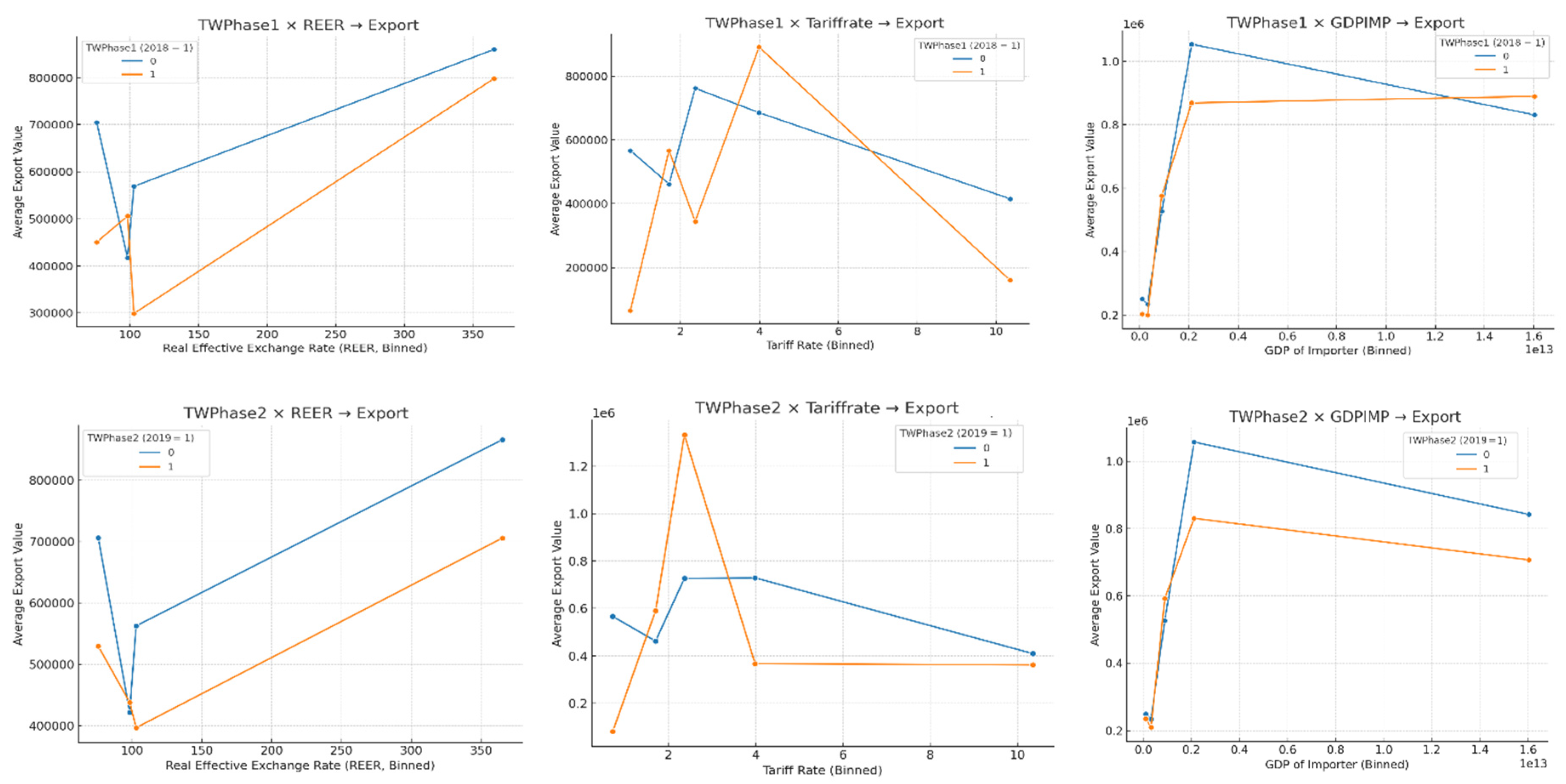

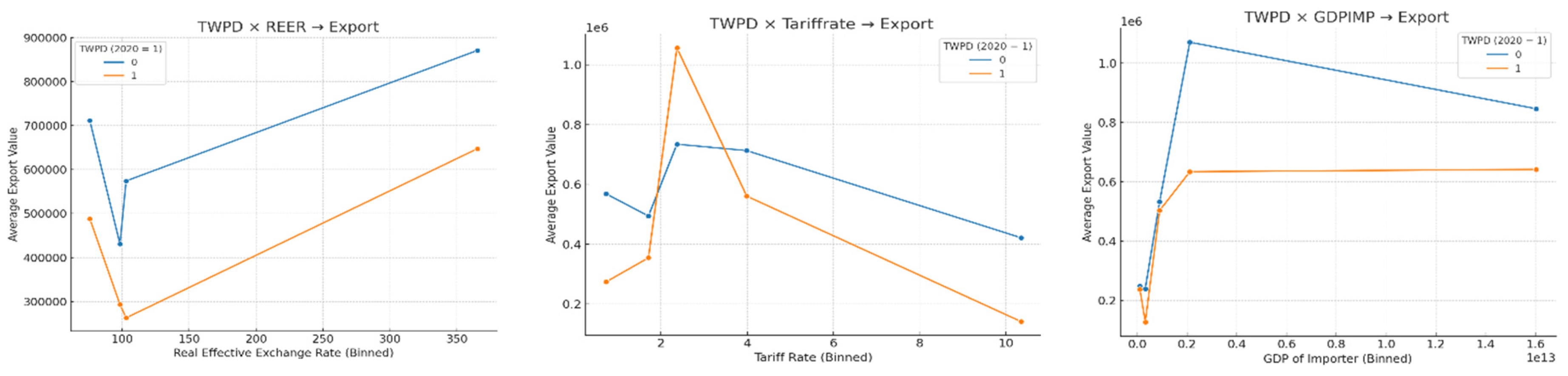

4.4. The Impact of Trade War Phases and Macroeconomic Indicators on Exports

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

References

- Anderson, J.E.; van Wincoop, E. Gravity with gravitas: A solution to the border puzzle. Am. Econ. Rev. 2003, 93, 170–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillmann, A.M.; Jung, I.J. Reproducible air passenger demand estimation. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2023, 106, 102320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumol, W.J. The Free-Market Innovation Machine: Analyzing the Growth Miracle of Capitalism; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2002; Available online: https://press.princeton.edu/books/paperback/9780691090927/the-free-market-innovation-machine.

- Chor, D.; Li, J. Illuminating the effects of the U.S.–China trade conflict in Southeast Asia (NBER Working Paper No. 29349); National Bureau of Economic ResearchL: Cambridge, MA, USA. [CrossRef]

- Dansranbavuu, L.; Sodnomdavaa, T.; Tsedendorj, E. Dutch disease symptoms in Mongolian economy and ways to reduce its negative effects. Int. J. Emerg. Multidiscip. Res. 2018, 2, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noviyani, D.S.; Tanjung, W.T. Indonesian export efficiency: A stochastic frontier gravity model approach. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2019, 8, 488–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogah, K.E. Effect of trade and economic policy uncertainties on regional systemic risk: Evidence from ASEAN. Econ. Model. 2021, 99, 105497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajgelbaum, P.D.; Goldberg, P.K.; Kennedy, P.J.; Khandelwal, A.K. The Return to Protectionism (NBER Working Paper No. 25638); National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.Y.; Mahendran, S. Determinants of export: A gravity model analysis of Malaysia’s electrical and electronic industries. J. High. Educ. Orient. Stud. 2023, 3, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayakawa, K.; Ito, T. The Trade Impact of the U.S.–China Conflict in Southeast Asia (IDE Discussion Paper No. 873); Institute of Developing Economies, JETRO: Chiba, Japan, 2022; Available online: https://www.ide.go.jp/English/Publish/Discussion_Papers/873.html.

- Kahn, M.E.; McLaren, J.; Zhang, M. How the U.S.–China Trade War Accelerated Urban Economic Growth and Environmental Progress in Northern Vietnam (NBER Working Paper No. 33126); National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, R.C.; Cooray, A. Export performance of developing countries: Does landlockedness matter? World Econ. 2018, 41, 2861–2886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swenson, D.L. Trade-war tariffs and supply chain trade. Asian Econ. Pap. 2025, 24, 66–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yones, R.F. Macroeconomic determinants of air passenger demand in Egypt. Sci. J. Financ. Commer. Stud. Res. 2023, 4, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadhan, S. U.S. Tariffs and Europe’s Slowdown Reshape Global Solar Panel Trade; Reuters: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2025; Available online: https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/boards-policy-regulation/us-tariffs-europe-slowdown-reshape-global-solar-panels-trade-2025-05-07/.

- World Trade Organization. Easing Trade Bottlenecks in Landlocked Developing Countries; WTO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/publications_e/landlocked2021_e.htm.

- United Nations Development Programme. Landlocked Developing Countries: Looking Back and Ahead—Accelerating Action in the Next 10 Years; UNDP: New York, NY, USA, 2025; Available online: https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/2025-08/undp-landlocked-developing-countries-looking-back-and-ahead-v2.pdf.

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. Mapping the Size of New U.S. Tariffs for Developing Countries; UNCTAD: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025; Available online: https://unctad.org/news/mapping-size-new-us-tariffs-developing-countries.

- International Trade Centre. U.S. Tariffs Impact; United Nations Office at Geneva Multimedia Newsroom: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025; Available online: https://www.unognewsroom.org/story/en/2710/us-tariffs-impact-itc.

- Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific. Asia-Pacific Trade and Investment Report 2019: Navigating the New Normal in Trade and Investment; United Nations ESCAP: Bangkok, Thailand, 2019; Available online: https://repository.unescap.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/93123bda-646d-42e1-a689-fb7c7d37ef77/content.

| Country | China | USA | Country | China | USA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | 2.1 | 0.3 | Laos | 75.5 | 1.6 |

| Armenia | 8.4 | 0.0 | Mongolia | 91.4 | 1.1 |

| Azerbaijan | 0.0 | 0.0 | Nepal | 12.0 | 0.4 |

| Bhutan | 0.9 | 0.1 | Tajikistan | 27.6 | 0.0 |

| Kazakhstan | 18.3 | 2.4 | Turkmenistan | 69.6 | 0.1 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 3.3 | 0.0 | Uzbekistan | 5.8 | 0.7 |

| Variables | OLS (Log-Log) | PPML (Baseline) | PPML+ Year FE | PPML+ Pair&Year FE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | t-stat | Coef. | z-stat | Coef. | z-stat | Coef. | z-stat | |

| Intercept | -17.352 *** | -15.22 | -18.210 *** | -18.97 | -18.045 *** | -18.65 | -18.002 *** | -18.61 |

| LOG(GDPEX) | 1.716 *** | 21.31 | 0.962 *** | 19.42 | 0.947 *** | 19.05 | 0.950 *** | 19.10 |

| LOG(GDPIMP) | 0.522 *** | 13.18 | 0.406 *** | 11.97 | 0.402 *** | 11.86 | 0.398 *** | 11.75 |

| LOG(DISTANCE) | -1.258 *** | -25.44 | -0.887 *** | -23.50 | -0.873 *** | -23.15 | -0.865 *** | -22.91 |

| BORDER | 0.384 ** | 2.55 | 0.283 *** | 3.89 | 0.275 *** | 3.78 | 0.270 *** | 3.72 |

| COMLANG | 0.840 *** | 5.69 | 0.207 *** | 3.11 | 0.203 *** | 3.05 | 0.200* ** | 3.00 |

| Observations=2700 | Pseudo | Pseudo | Pseudo | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).