2.1. Description of the KfW Program

This section gives an overview of the rules of KfW’s lending program, built specifically to deal with the pandemic episode starting in 2019, and it presents summary statistics on the allocation and the volumes of the offered public loan contracts. Explanations and rationalizations are mostly left for later sections of the paper. KfW is the German development bank, acting within national boundaries and also in the EU and in less developed countries (Mertens (2021)).

The initiative for a KfW loan contract may be taken by a firm or by its bank, provided that the eligibility conditions of the contract are met. Both have to agree.Typically, KfW has no prior experience with a firm asking for a loan. It relies on the bank as an intermediary. The implied cost saving is particularly essential for programs targeting many small firms. As public loans include some gift of the taxpayer, access to these loans needs to be constrained. Constraints include restrictions on the quality of the subsidized firm, on the maximum amount and the maximum maturity of public loans, and restrictions on the firm´s use of the money ( see also Bundesrechnungshof 2022). In the following, we present the essential restrictions for each contract variant.

a) Rules on Instant Loans, Entrepreneur Loans, Direct Participation in Syndicated Lending

During the pandemic episode, KfW offered three different types of loan facilities, the Instant Loan (Schnellkredit), the Entrepreneur Loan (Unternehmerkredit) including the Loan for Young Firms (Gründerkredit), and Direct Participation in Syndicated Lending (syndicate lending, SL, see KfW (2020a)). For all three KfW-contract variants, the loan must not be used to substitute for bank loans, and the firm is not allowed to pay dividends, pay out profits or repay equity capital until the loan is fully repaid.

SL started in March 2020, soon after the pandemic started. In SL, KfW joins a syndicate and contributes at least €25 m to the syndicate loan. The lead arranger of the syndicate is usually a bank closely related to the firm. KfW may take an active role in project screening and deal structuring. A firm is eligible only if it is not in default, there is no moratorium, no serious covenant breach and if the firm has a viable business model. The maximum loan amount is limited to at most ¼ of the revenues in 2019, twice the labor cost in 2019, 50% of the firm´s total debt and to liquidity needs for the next twelve month. Maturity is limited to 6 years. Collateral and covenants may be included in the loan contract. KfW absorbs up to 80% of the default losses experienced by the syndicate.

As we focus on public loans to SMEs, we mostly exclude SL in the following sections.

In April 2020, KfW started the Entrepreneur Loan and the Instant Loan programs. Among the eligibility criteria for applying firms is a 1-year default probability of not more than 10% as estimated by the bank filing the application

4. Applications for the Entrepreneur Loan also required that the firm was not an ‘undertaking in difficulty’ (see EU-Regulation 651/2014, Art. 2 #18) at the end of 2019 and whose funding in 2020 would not have been in difficulties without the pandemic.

For an Entrepreneur Loan, the loan volume is limited to 100 million EUR and maturity between 6 and 10 years. The same caps for the loan amount apply as for SL, except that for SMEs liquidity needs are limited to 18 months. KfW absorbs 90% [80%] of the default losses in case of SMEs [larger firms]. It charges an interest rate between 1 to 1.46% for SMEs and 2% to 2.12% for larger firms. In the case of a larger loan, KfW may analyze the loan risk and charge a lower interest rate if the debtor has a better rating or if collateralization of the loan is stronger. The risk margin of the loan is split between KfW and the bank according to the default risk. KfW´s risk margin is inversely related to the loan´s default risk so that the bank´s risk margin increases with default risk and, thus, motivates the bank to take a higher default risk. For undisbursed parts of the loan KfW charges 0.15% per month. The loan can be redeemed anytime without penalty interest. Several restrictions are designed to deal with the risk of free riding (see KfW (2020b)). Normal remuneration to owners being natural persons is allowed.

For the Instant Loan_there are different eligibility conditions. Only firms can apply which were profitable in the previous year (i.e. in 2019), or on average over the last three years (see KfW (2020c)). Instant loans are firm size dependent, initially with an upper limit of €300,000 for firms with up to 10 employees, €500,000 for firms with up to 50 employees and €800,000 for larger firms. These limits were raised later on. The loan must not exceed ¼ of the revenues in 2019. Maturity of the loan is limited to 10 years. KfW bears 100% of all potential default losses and charges an interest rate of 3% per year. Collateral for the KfW-loan is not allowed.The full amount of the loan has to be drawn down within one month after KfW-acceptance. The loan can be redeemed costlessly anytime. Management compensation is limited to 150,000 € p.a. per person.

KfW uses a fully automated procedure for handling the application for an Instant Loan. This is also true for Entrepreneur Loans up to €3 m. Fully automated means: KfW relies completely on banks for due diligence, as information intermediaries and as service agents, without explicit risk analysis and without renegotiations. After signing a contract with the bank, KfW transmits the loan volume to the bank which is obliged to transmit it to the firm. It collects interest payments and loan repayments of the firm and transmits these to KfW. The bank monitors the firm and passes new important information about the firm. Yet, KfW may have quite limited information about the firm. When it comes to a workout/restructuring of the firm, KfW typically retains the right to interfere and to be involved in decision making.

The fully automated procedure not only reduces the transaction cost of a KfW loan, it also allows for near-instant KfW-decisions on applications – a feature particularly welcome in a crisis. Automatization involves a tradeoff between lower transaction costs and increased risk for the taxpayer, due to the absence of KfW´s credit risk analysis and the exclusion of (re)negotiations of KfW with the firm. This underlines the important role played by tier-1 banks in determining the success of an automated lending program. Given this tradeoff, KfW restricted the automatic procedure to Entrepreneur Loans up to 3 mio €. For larger loans, KfW gets increasingly involved in the decision process. For loans between €3 and 10 m, KfW may use a simplified risk analysis including not only the firm risk, but also aiming at a „fair“ sharing of the default risk with banks. For loans between €10m and €100m, KfW carefully analyzes the firm risk including future business prospects and negotiates details of the loan terms including collaterals and the term structure of repayments. For example, banks may be urged by KfW to extend the term structure of their loan repayments.

b) Selected evidence on KfW’s support program

Next, we present some evidence on loan applications and granted loans to better understand the economic importance of the KfW pandemic program. KfW generously provided us this evidence.

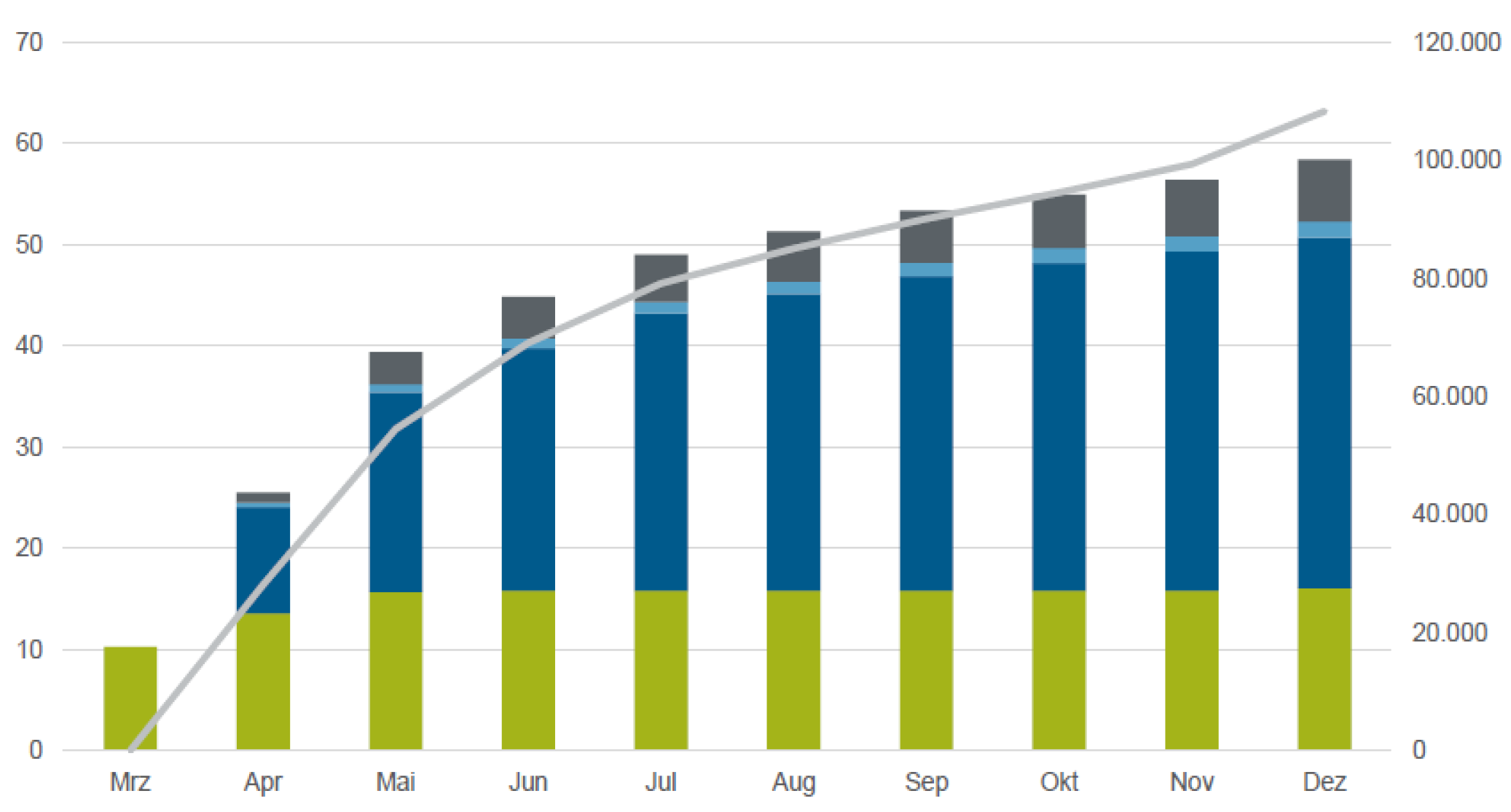

Figure 1 shows monthly application volumes (bn. €) of the special program from the start in March 2020 to November 2021. The November 2021 figure represents only the first third of the month.

Table 1.

Annual numbers of applications and of accepted applications for the KfW-pandemic program, in addition annual application volumes, accepted volumes and average of accepted volumes

5.

Table 1.

Annual numbers of applications and of accepted applications for the KfW-pandemic program, in addition annual application volumes, accepted volumes and average of accepted volumes

5.

| year |

# applications |

# accepted applications |

Application volume (bn. €) |

Accepted volume (bn. €) |

Average application volume (€) |

| 2020 |

108,444 |

102,833 |

60.659 |

45.870 |

559,358 |

| 2021 |

44,992 |

43,807 |

8.640 |

8.390 |

192.123 |

| total |

153,436 |

146,640 |

69.303 |

54.260 |

- |

Clearly applications peaked in March to June 2020 when the program started, and the economy was severely hit by a lockdown. This lockdown ended in June, firms became more optimistic and applications dropped significantly until October 2020 when infection numbers strongly increased again and a selective lockdown was imposed on some branches, in particular hotels and restaurants. The application volume dropped to €1.7 billion in October and increased to € 2.0 billion in December. Even though the selective lockdown was removed gradually ending in May 2021, application volumes dropped to € 1.2 billion in January 2021 and then declined further. This is presumably also related to satiation effects. And firms could not apply to the special program more than once.

A closer look at the critical year 2020 shows: More than 108,000 applications were received, almost 103,000 applications were accepted, with a volume of almost €44 billion. While the average volume of accepted applications was about 446,000 €, the median volume was only €115,000. This is also explained by the demand for the different contract variants as depicted in

Figure 2.

Volume of applications (bn. €, cumulative) total number of accepted applications (cumulative)

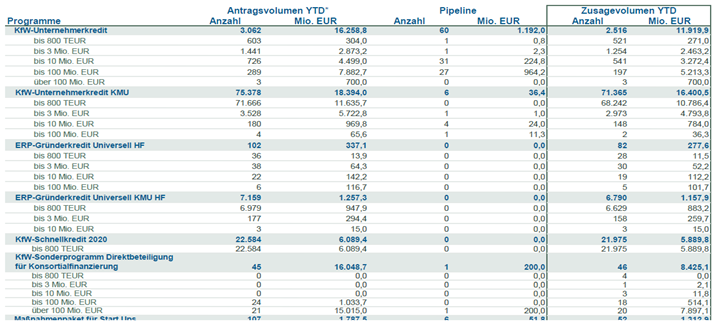

Direct Participation in Syndicate Lending started in March, before the other programs. Big firms had filed 35 of the overall 45 applications already by the end of April 2020. The application volume totaled €16.249 bn. in 2020. 42 applications were accepted and granted € 8.425 bn. Out of 21 applications for more than €100 m with a volume of €15.015 bn. 20 were accepted and granted €7.897 bn., with an average of almost €395 m. Officially rejected were 4 applications. Internally KfW classified about 15% of all formal and informal applications as rejected, with about 5% being rejected by KfW and about 10% being rejected by firms due to additional contract terms imposed by KfW.

By far the most important contract variant was the Entrepreneur Loan. 85,701 applications were filed in 2020 with a volume of €36,247 bn., including 82,537applications from SMEs. 80,753 applications were granted € 29.755 bn., with an average of about €368,500. In particular, applications for larger volumes were not successful. For the Instant Loan out of 22,584 applications with a volume of €6.089 bn. 21,975 applications were accepted with a volume of € 5.890 bn., implying an average volume of about €268,000. No application was officially rejected.

The low official rejection numbers are also explained by the tier 1-banks´ role. They had to check the formal requirements for a KfW-loan. KfW accepted 99% of the applications by an automated procedure. The distribution of loan volumes is strongly skewed. While the average for each contract variant is above €200,000, the median of all granted loans is only €115,000. 97% of the applications in 2020 were from SMEs.

The total accepted volume of the pandemic program at the end of 2020 was €45.87 billion which is 1.33% of the German 2019 GDP. This may appear as rather small. The KfW special program, however, is only a small part of a rather comprehensive German program of many different public stimulus measures for the economy.

6

The overall disbursement ratio of granted volumes was about 2/3 at the end of 2020. Roughly 1/3 of the large loans, checked in detail by KfW, were already fully repaid or canceled. For the smaller loans this ratio was about 15%.

Due to the long maturity of many loans, it is too early to estimate the default rate of the Covid -19 program. Dörr et al. (2021) analyse credit rating and insolvency data of actively rated German firms and conclude that the policy response to COVID-19 has triggered a backlog of insolvencies in Germany that is particularly pronounced among financially weak, small firms.

2.2. Targeted Lending: Aims, Constraints, Restrictions and (Suitable) Contractual Design

a) Aims of public support programs and empirical evidence

Public support to firms in a crisis aims to prevent permanent damage, using cost effective means (Lucas 2020). Observed Covid-19 programs reveal a large variety of programs across countries, including public loans, public loan guarantees, moratoria for existing loans, short labor money, financial support á fonds perdu, etc. Public lending schemes are intended to tilt financing flows from what they would be under zero support conditions to what they ought to be, in the eyes of policy makers. However, according to Art. 107, 1 of the Lisbon Treaty, state-aid which distorts or threatens to distort competition, is generally not permitted. Exceptions are related to market disorder and to damages caused by natural disasters, or other exceptional events. The principal economic rationale for public support is “that market failures may lead to less investment and, thus, slower future growth than would be economically efficient, and that an institution with a public mandate is better placed than private operators to overcome these market failures”. “Asymmetric information can lead to market failures, for example, “credit rationing and high return requirements due to banks' high transaction costs” (EU 2015, p. 3). At the same time, public support should be designed so as to avoid undesirable effects “such as maintaining inefficient market structures, sectors with overcapacity or supporting undertakings in difficulty; crowding out of private sector financiers, thus holding back financial sector development” (EU 2015, p. 4). To minimize market distortions, public aid designs should copy well-established market mechanisms, achieving a second best.

According to the Group of Thirty (2020, p. 3f) “Public support should adapt to new business realities rather than trying to preserve the status quo”, in particular facing an L-shape . “Private sector expertise should be tapped to optimize resource allocation, where possible. Properly functioning markets can help allocate resources … using existing expertise and funding channels.” “Minimize risk and maximize upside potential for taxpayers while ensuring stakeholders share in losses and do not receive unjustified windfalls.”

The empirical evidence suggests that primarily firms obtained public support which were heavily affected by the Covid-19 crisis, but not close to financial distress . Altavilla et al (2021) find for EU-countries that guaranteed loans are overwhelmingly awarded to small firms which are heavily affected by Covid-19, excluding firms close to distress before Covid-19. Bonaccorsi di Patti et al (2024) observe that firms facing bigger illiquidity shocks due to a revenue collapse more likely demanded guarantees. Ex ante-riskier borrowers were less likely to get guaranteed loans. Mateus et al (2022) observed in Portugal that guaranteed loans were mostly given to ex ante low risk-firms which suffered most from Covid-19. The riskier firms paid higher interest rates and obtained smaller loans, but benefited more from moratoria. Goldberg et al (2024) also find in the EU that more guarantees are given to firms more affected by Covid-19, to smaller firms and to less risky firms. Moreover, more guarantees are observed at larger banks. According to Jiménez et al (2024), in Spain banks provide more public guaranteed loans to riskier firms in which banks have a higher pre-crisis share in firm total credit. Weaker banks shift riskier corporate loans to taxpayers. Huneeus et al (2023) find for the partial guarantee program in Chile that lending shifted towards riskier firms. But the implied macro risk was small because banks had skin in the game. According to Cao et al (2024), in some countries publicly supported firms are riskier, also the involved banks. But in the majority of countries, bank risk and size do not matter.

These empirical studies do not distinguish between public support driven by need and driven by damage. This distinction is difficult to validate empirically because, apart from fincancially strong firms and zombies, need and damage are positively correlated. The empirical findings provide some evidence that zombies tend to be excluded from public support. But care should be taken when linear regressions of public lending on firm quality are applied, as in the quoted studies. First, if weak firms get public support, but neither very strong nor very weak firms, then there exists a substantial non-linearity between public lending and firm quality. Thus, linear regressions support misleading conclusions. Second, whether more or less risky firms get public support, can only be answered in relative terms if the frequency distribution of firm quality is taken into consideration.

Next, we will discuss approaches to design state-aid in view of important frictions, in particular, asymmetric information, externalities and market power (European Commission 2015, sect. 2.1; see also Group of 30, 2020). In addition, state-aid design should take into account macro uncertainty, i.e. the nature of the economic shock is only gradually revealed.

b) V-shape or L-shape?

Regarding the nature of the shock, in a V-shaped recovery business activity resumes after a short time, and if public support is offered, it is disbursed widely among business subjects so as to retain a level playing field in the economy at large. In contrast, in a longer lasting L-shaped recovery, overall economic activity will not resume where it stopped before the crisis. Instead, besides of the fall in economic activity, typically business conditions are changing, including changes of consumer demand for goods and services and changes of supply chains. Moreover, technological innovations and new regulations, some of which are driven by the very crisis event, may force firms to invest in new technologies or different business processes. L-shaped recoveries, therefore, also motivate firms to reorganize and restructure their activities.

The incidence of V-shape or L-shape is typically unsung until after the crisis has unfolded for some time. How the crisis unfolds, depends also on the speed and effectiveness of state-aid so that a lack of state-aid may promote an L-shape. As a consequence, state-aid must not only take into consideration the rebuilding and restructuring needs, it should also support (disruptive) innovations. In other words, a planned state aid program has to encompass the corporate restructuring aspect from day one on, along with the purely liquidity-oriented bridge financing aspect.

Over time, as more information intrudes and V and L shapes may be identified better, the support program should be adjusted accordingly. The main insight at this point is that due to the ambiguity on V and L, government support programs need to be versatile enough to be supportive in both scenarios, the pure liquidity crisis requesting bridge loans, and the deeper solvency crisis requesting, in addition, support for business transformation.

c) Direct or intermediated design of lending scheme?

To minimize market distortions state-aid should be managed by a national development bank (NDB). Public aid designs should copy well-established market mechanisms, achieving a second best. Therefore, support programs typically rely on a 2-tier intermediation structure which allows to take advantage of the available information at the level of financial intermediaries, esp. banks. Banks, which we designate as “tier-1 banks”, manage the lending relationship with firms, while the allocation of subsidies to firms and to tier-1 banks, in the form of subsidized refinancing, is managed by a “tier-2” institution, typically the NDB. This 2-layer set-up preserves much of the existing financial architecture of the economy.

Yet, this special arrangement of a private public partnership poses many problems as discussed by Fabre et al (2023). The well-known agency problems of bank lending are now 2-tiered as well. That is, the NDB has to deal with the risk that its client tier-1 banks may use the subsidies for themselves rather than channeling them in full to their own clients, the ultimate borrowers. The taxpayer faces adverse selection and moral hazard not only of borrowing firms, but also of banks, acting separately or jointly.

d) Restricting Adverse Selection

α) A Partially Revealing Signaling Equilibrium

Information asymmetries favor adverse selection by firms and banks such that they extract more public lending benefits than socially desirable. As discussed before, in line with European law and economic arguments, we use the “need model” as a benchmark for social desirability and not the “damage model” which gauges public support to the damage incurred by a firm in the economic crisis. Very weak firms and very strong firms should not get public support, the latter because they can cover their financial needs in the market, the former because public money would be wasted ruling out social desirability

7. A tier-1 bank would probably benefit from channeling a NDB-loan to a zombie firm to which it is exposed. In order to prevent this, the financial rating of the firm should satisfy given standards. The tier 1-bank knowing the firm is best suited for such rating. In its Covid program, KfW imposes this burden for small loans on the tier 1-bank which has to confirm that the 1 year-PD of the firm does not exceed 10%. This PD, equivalent to a rating, might be a rather crude instrument to rule out zombie financing. KfW assumes that tier-1 banks report PDs truthfully.

Cao et al (2024) find that in all countries very weak firms are excluded from public support, often defined by bad ratings. This also prohibits evergreening, i.e. prolonging loans so as to avoid default (Faria-e-Castro et al, 2023). Also, there are always caps on public loans/guarantees provided to firms (Cao et al, 2024) limiting public support to some measures of firm size. Many countries impose restrictions for the use of public money, for example using it only for working capital. This kind of cap likely ignores the needs of firms in a L-shape crisis.

Some countries prohibit substitution of bank loans by public loans (Cao et al (2024)).

Another reason for rationing the loan supply is that a firm may have unobservable alternative funding options so that there is no need for more public funding. These hard-to-observe funding sources comprise loans from other lenders, including the very bank handling the loan request. Rationing public loans also helps to prevent arbitrage of the firm by investing cheap public funds in the market. The imposed limits on the loan volume may still leave room for some public “overfunding”.

In order to minimize adverse selection, we propose a partially revealing signaling equilibrium (PRSE) in which each firm chooses a public funding contract whose subsidy increases with the firm´s needs. The NDB offers a set of lending contracts (state-aid options) from which a firm selects, in its own best interest, a contractual option which reveals its quality to the lender. To explain the idea of truth-telling, we sketch an argument borrowed from the literature

8, relying on the concept of a PRSE. In such a model, the SME´s choice of a particular state-aid option reveals its financial strength/weakness as a byproduct. For this mechanism of self-selection to work, the NDB has to offer a suitable set of contractual options from which potential borrowers can choose one. In a PRSE, the self-selection reveals the publicly unknown “true” borrower quality. We will illustrate a PRSE in an abstract model first, and then turn to the implications.

Assume that all firms are risk-neutral. Moreover, as a potential borrower, it prefers loans with a higher subsidy, everything else being the same. The NDB offers various one period-loans j, each with maximum volume V(j) and nominal interest rate i(j), j=1,..J. The firm can only apply for one of these loans. It chooses the maximum volume to maximize the subsidy. The NDB can invest in a risk-free asset yielding the risk-free rate r, or it may grant a subsidized loan to the firm. The firm repays V(j) (1+i(j)) after one period with probability (1-PD) and zero otherwise. PD is the probability of default of the firm under the condition that it receives a subsidized loan according to its needs. The subsidy inherent in the loan is

The subsidy is positive for i(j) ≤ r and increases in PD. To discourage firm requests for high loan volumes beyond need, the interest rate should increase with the maximum loan volume so that V(1) <V(2) < … V(J) and i(1) < i(2) < … < i(J) ≤ r. Hence, the firm´s choice involves tradeoffs of higher volumes against higher interest rates. The loan which maximizes the subsidy depends on the firm´s PD, unknown to the NDB.

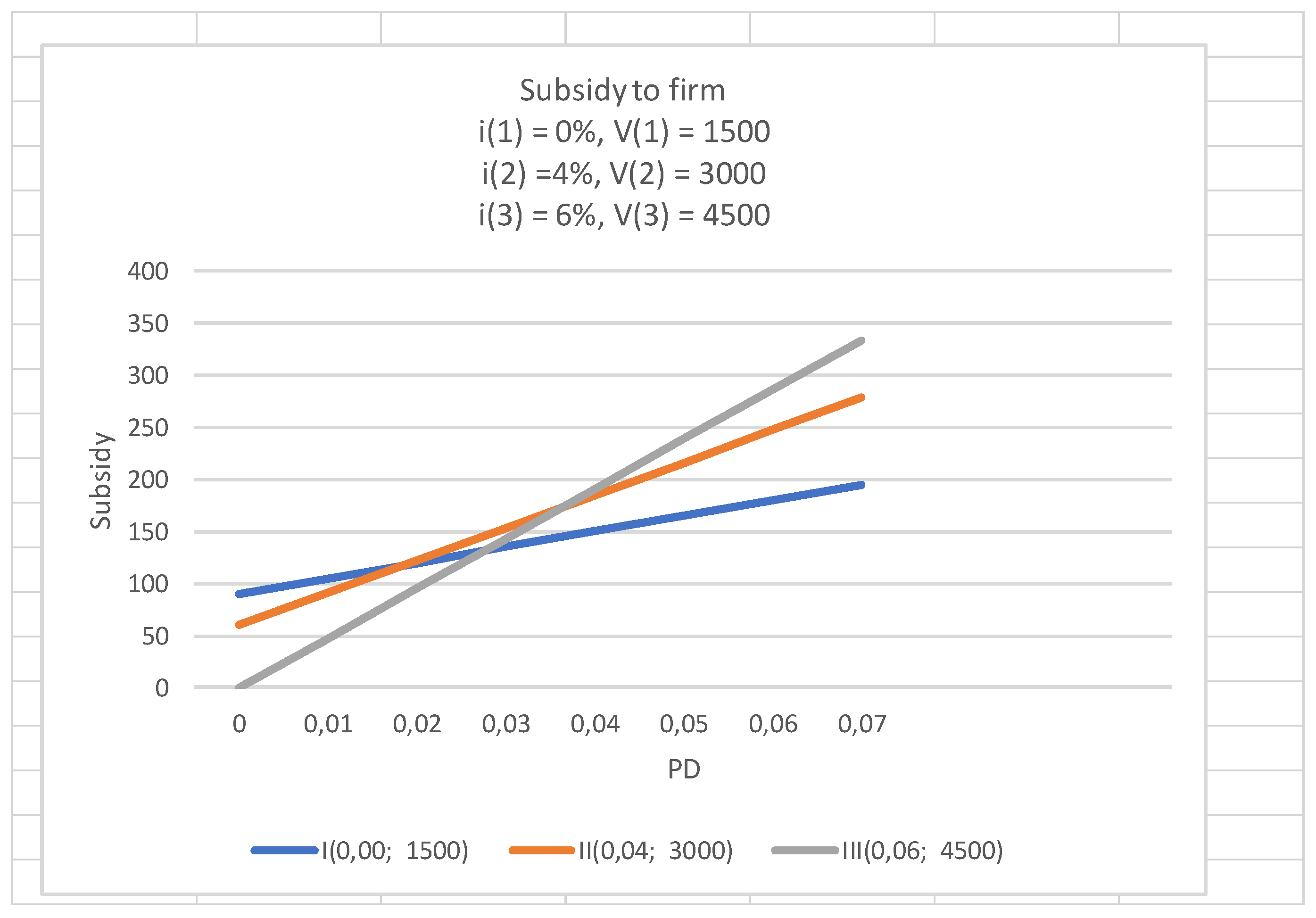

Figure 3 illustrates the subsidy for three different loans as a function of the firm´s PD.

Loan (1) with a volume limit of 1500 € charges no interest, loan (2) with 3000 € charges 4% and loan (3) with 4500 € 6%. Given a risk-free rate of 6%, loan (1) yields the highest subsidy for a PD < 1.85%, loan (2) for a PD between 1.85 and 3.64% and loan (3) for a PD above 3.64%. A resilient firm (low PD) prefers option 1 with a low volume and zero interest rate, while a weak firm (high PD) prefers option 3 with a high volume and a high interest rate. Thus, the contract choice reveals the firm´s PD-range.

In general, the limits V(j) and the interest rates i(j) need to be chosen so that the upper envelope of the linear curves is convex. The more loan options are offered by the NDB, the smaller is the PD-range which maximizes the subsidy for a particular option, the more granular is the PD-signal. Obviously, given different sizes of SMEs, the loan limits V(j) have to be adjusted to firm size, for example, by an asset based or a cashflow based size measure as done by KfW.

In the PRSE the subsidy increases in the firm´s PD which increases with the firm´s need V. Weak/strong firms receive large/small public loans with strong/small subsidies. This is in line with the “need” model and the EU-rules for public support. A stronger need for public support signals a higher PD and justifies a higher subsidy. To avoid zombie financing, there is an upper limit on the PD, enforced by the bank, so that the horizontal axis in

Figure 3 would stop at that PD. In this model, one period loans can be replaced by multi period loans defining the overall subsidy as the present value of subsidies in all periods until maturity.

So far, a higher loan volume commands a higher interest rate so that the loan choice reveals the quality of the firm. Alternatively, the disciplining mechanism of a higher interest rate may be replaced by stricter covenants or more collateral. Essential is that there is a tradeoff between the contract options so that the subsidy-maximizing choice reveals the quality of the firm. The government can preselect the general subsidy level by choosing the terms of the offered loans in line with social preferences.

A larger variety of contract options would induce firms and banks to reveal more information by a more granular signal. This information enables the NDB to better constrain adverse selection through the design of contract options. It also renders further information collection by the NDB largely redundant. Typically, writing a loan agreement involves the collection of initial information and sequential information through renegotiation. Given a rather granular quality signal in a PRSE, renegotiation is rather useless so that the fast, automatic decision routine used by KfW for small loans which precludes renegotiation appears to be efficient.

For illustration, KfW offered the Entrepreneur and the Instant Loan. Given a small loan, the firm can choose between both loans. As the interest rate is higher for the Instant Loan and delayed withdrawal of funds is not permitted, but the other terms are similar for both contracts, the firm always prefers the Entrepreneur Loan, in contrast to a PRSE. The bank, however, prefers the Instant Loan, in particular for weak borrowers, because the bank does not share the default risk of this loan, n contrast to the Entrepreneur Loan. Thus, the choice of the Entrepreneur Loan is firm driven, the choice of the Instant Loan is bank driven. This mechanism differs from a PRSE in which only the firm is acting.

ß) How to avoid windfall gains by public funding?

Exogenous shocks may lead to windfall gains of some players. But public funding should not automatically award windfall gains to firms and banks.

First, the “need model” excludes financially resilient firms from public lending. If only weaker viable firms qualify for public support, they might enjoy a windfall gain because excluded resilient firms may not be able to capitalize on their strengths. Public support programs should be designed in a way that mitigates such anti-competitive effects, but at the same time prohibits undesirable concentration of market power. However, the windfall gain argument overlooks the fact that resilient firms have easy access to market funding and, therefore, can pursue their competitive advantage without public funding. Thus, windfall gains of weaker firms are unlikely.

Second, to avoid windfall gains of resilient firms, a well defined support program would not exclude these, but leave their exclusion to the better informed tier 1- banks. An appropriate mechanism is a design of the public loan contract options so that the bank prefers to lend itself to the firm instead of filing an application for a public loan contract. Consider a simple stylized model.

Due to the macro shock, the firm faces a liquidity gap with volume V. The bank can fill this gap by providing an additional loan at some interest rate i*. Alternatively, the firm receives a public loan at an interest rate ip. Apart from the difference in interest rates, the firm´s PD is the same in both cases as the firm´s liquidity stays the same. Given a risk-free rate r, an extension of the bank loan changes the bank´s expected profit by V (i* - r) -V(1+ i*) PD. In the case of a public loan, the bank has to take the share δ of the default risk of the public loan with an expected cost of δ V(1+ip) PD.

Hence, the difference in the bank´s expected profit, ΔEP

B, is

As i* > r, the first term is positive while the second term converges with PD to 0. Therefore, the bank prefers extending its own loan instead of asking for a public loan if the firm is resilient, i.e. PD is sufficiently small. Hence, resilient firms do not get subsidized loans

9. The bank is better off with a subsidized loan if the firm is weak

10.

Third, does public support provide a windfall gain to tier-1 banks? Windfall gains would accrue to banks if they would not take a share of the default losses of public loans given to their customers. In the absence of new private funding, a public loan reduces a firm´s PD and, thereby, also the default risk of private loans. A public loan without any risk sharing would strongly motivate the bank to exploit the taxpayer by searching for public support, in particular for weak firms. Such support would be a free lunch for the bank at the expense of the taxpayer.

If banks are financially resilient, then a free lunch to banks has no justification, it violates European aid law. If banks are in trouble themselves due to the macro shock, then there are more effective ways to support banks directly than indirectly through support of their debtors. Hence, banks and the taxpayer should share the default risk of public loans for firms.

Cao et al (2024) find a coverage ratio (= share of default risk of the public loan/guarantee, absorbed by the NDB) of 100% only for small public loans to SMEs in some countries.

The take-away from this modeling exercise is this: a public lending scheme which offers a viable firm various lending options so that the firm´s choice reveals its quality, reduces information asymmetry and, thus, alleviates the welfare cost of asymmetric information through a PRSE. This PRSE renders automated lending without renegotation less dangerous for the NDB.The tradeoff between different options implies that weaker firms, i.e. those with a stronger need for financial support, obtain more funding and higher subsidies. Public lending to resilient firms is unattractive to the intermediating tier 1-banks and, thereby, ruled out, in accordance with European law. These properties enhance welfare by strengthening the market mechanism and prohibiting windfall gains to firms through public funding.

e) Restricting Moral Hazard

Moral hazard also plays an important role in the business relationship between the bank and the NDB. Once the public loan has been granted, both typically compete for the firms´s cash flows until the final repayment of the public loan. If the firm’s default risk goes up, the bank may ask the firm to repay its loan using public funds or, later on, to early repay its seasoned loan by delaying repayment of the subsidized loan. To avoid that, the NDB has to put up barriers against substitution of private by public loans, for example, by covenants or seniority requirements. But it is difficult for the NDB to distinguish between loan substitution enforced by the bank, and normal repayment of bank loans using public money. This is almost impossible when then NDB has no communication with the firm and fully relies on the bank as an intermediary.

A second source of moral hazard relates to asset liquidation proceeds in the case of a borrower default, as the bank and the NDB are competing for repayment, and the remaining assets will likely fall short of the outstanding nominal claims. Therefore, the NDB may request higher seniority for its credit, for example, by explicit seniority rules, valuable collateral, or by shortened loan duration.

The restructuring or liquidation procedure itself is a source of moral hazard if the NDB stays passive. While liquidation is largely governed by law and contractual arrangements, often restructuring requires difficult, information-sensitive decisions, including loan prolongations, moratoria, asset sales and fresh funding. These decisions may require changes in seniority rules and collateral arragements, also there may be a need for fresh public money. To protect the taxpayer, the NDB cannot delegate such decisions to a bank even if there are specific contractual provisions ensuring equal treatment of all lenders (the time-honoured rule of

par conditio creditorum)

11. The NDB has to take an active role in restructuring procedures.

Equally important is moral hazard of owners and managers of the firm. Debt holders face the risk of loss due to untimely carve outs, be it through excessive dividend payments, share buybacks, increased management compensation or bonuses, and related-parties payments. Therefore, KfW prohibited profit payouts, equity repayments and constrained management compensation until full repayment of the public Covid loan. This covenant is not cost-free, however, because it tends to crowd out other funding sources, in particular new equity financing.

Another source of moral hazard emerges when the firm´s “need” for public support is gone, but it does not repay the public loan to benefit from the interest subsidy further on. This amounts to delayed substitution of bank loans. If public funding does not copy market mechanisms such as charging a higher interest rate for a longer loan maturity like markets do, then this discrepancy may create an arbitrage or pseudo-arbitrage opportunity for the firm at the expense of the taxpayer. Therefore, public loans should copy market mechanisms as far as possible.

So far, empirical evidence on adverse selection and moral hazard in Covid-19 support programs is sparse. Cao et al (2024) find no evidence for moral hazard of banks while Bonaccorsi di Patti et al (2024) neither find adverse selection nor moral hazard in public guarantees.

2.3. Targeted Public Lending in Practice: The COVID Years in Germany

In this section, we use results of the previous section to analyze the choices of firms and their banks with respect to the lending facilities offered by KfW during the Covid years. The aim is to detect behavioral patterns that can be used to improve the design of NDBs´ financial products. Wherever possible, we base our conclusions on evidence obtained from discussions with senior bank managers

12 and on KfW lending data. The focus is on public support for SMEs. The findings together with previous results will be used in the final section for policy recommendations on how state-aid should be designed to assure an effective and “fair” risk sharing between taxpayers (via tier-2 lending), firms (as ultimate borrowers), and banks (as tier-1 lenders).

a) Firm Rating and Contract Choice

We start with the impact of firm rating on contract choice, assuming that the KfW-restrictions for subsidized loans are satisfied. An application for state-aid requires a firm and its bank to agree on filing such an application. Thus, the first question is under what circumstances can we expect firms/banks to apply for subsidized contracts?

Proposition 1:

a) For a firm with a strong rating the relationship bank does not support a KfW loan application, but prefers to extend its own loan.

b) For a firm with a weak rating an application will be filed if the firm´s owners value the subsidy higher than the “costs” of the KfW-restrictions.

State-aid is designed to provide benefits to banks and firms at the expense of the taxpayer. The benefit to the bank is at best low, given a strong rating of the firm. The bank prefers to raise its expected profit by extending its own loans, without taking a substantial risk. Hence the bank likely rejects an application. This motivates Prop. 1 a). For a firm with a weak rating, the bank likely supports an application as a public loan would lower its overall default risk in the firm

13. The firm would benefit from the subsidy in the loan, but would have to bear the burden of the KfW-restrictions so that there is a tradeoff between the “costs” of this burden and the earned subsidy. Hence, mildly weak firms may reject public aid. This motivates Prop. 1 b).

In our discussions, senior bank managers predominantly confirmed Prop. 1a). One manager argued that state-aid should only be available if it is difficult for a firm to obtain a loan on the market. Another manager said that „his“ bank would not refuse an application of a strongly rated firm if it insists. But the bank would present alternative solutions which likely are market based.

Given a firm with a weak rating, how would the bank and the firm choose between the Entrepreneur Loan and the Instant Loan? As argued in the previous section, firms prefer the Entrepreneur Loan if they look for a small loan. This is evident looking at the number of applications and applied volumes for both types of loans, subject to a volume limit of € 0.8 m. In 2020, 78,645 applications with a volume of € 12,585 bio were filed for the Entrepreneur Loan, 22,584 applications with a volume of € 6,089 bio for the Instant Loan. The importance of disbursement flexibility of the Entrepreneur Loan is also indicated by a disbursement ratio of the granted volumes of about 2/3 for the overall pandemic program at the end of 2020, i.e. about 1/3 was still kept as an unused credit line.

Given a relatively good rating, the bank can underwrite 10% of the default risk of the Entrepreneur Loan easily, supporting the firm´s preference for this loan. If the rating is weak, however, the bank will insist on an Instant Loan because it takes no risk. This suggests

Consider a firm without a strong rating, but PD<10%.

a) Given a relatively good rating an application for the Entrepreneur Loan will be filed, b) given a relatively weak rating an application for the Instant Loan will be filed.

As KfW does not have data on the rating of firms, we cannot check directly the validity of Prop. 2. Some indirect evidence is provided by the average loan size of both loan types. Regarding KfW-loans with at most € 800,000, the average volume of the Entrepreneur Loan is € 156,000 and € 268.000 for the Instant Loan (numbers are derived from the Table in the

Appendix A, provided by KfW). The higher average volume of the Instant Loan indicates weaker firms so that banks prefer the Instant loan (where the banks take no risk) and push the firms to agree, despite of the higher interest rate and disbursement inflexibility. It should be noted that KfW uses the automatic procedure for both types of small loans so that it does not interfere in the choice between both loans.

The KfW representative considered Prop. 2 as plausible. Also, bank managers did not object to this proposition.

The observed combination of a higher volume and a higher interest rate of the Instant Loan relative to the Entrepreneur Loan is seemingly consistent with the PRSE in the previous section. But the choice of the Instant Loan, given a rather weak firm, is enforced by the bank which maximizes its own benefit even though the firm prefers the Entrepreneur Loan.

Altavilla et al (2021) find for EU-countries that public support is driven mainly by firms when they are solvent and have low liquidity needs, but by banks when firms are risky with strong liquidity needs. This is consistent with Prop. 2.

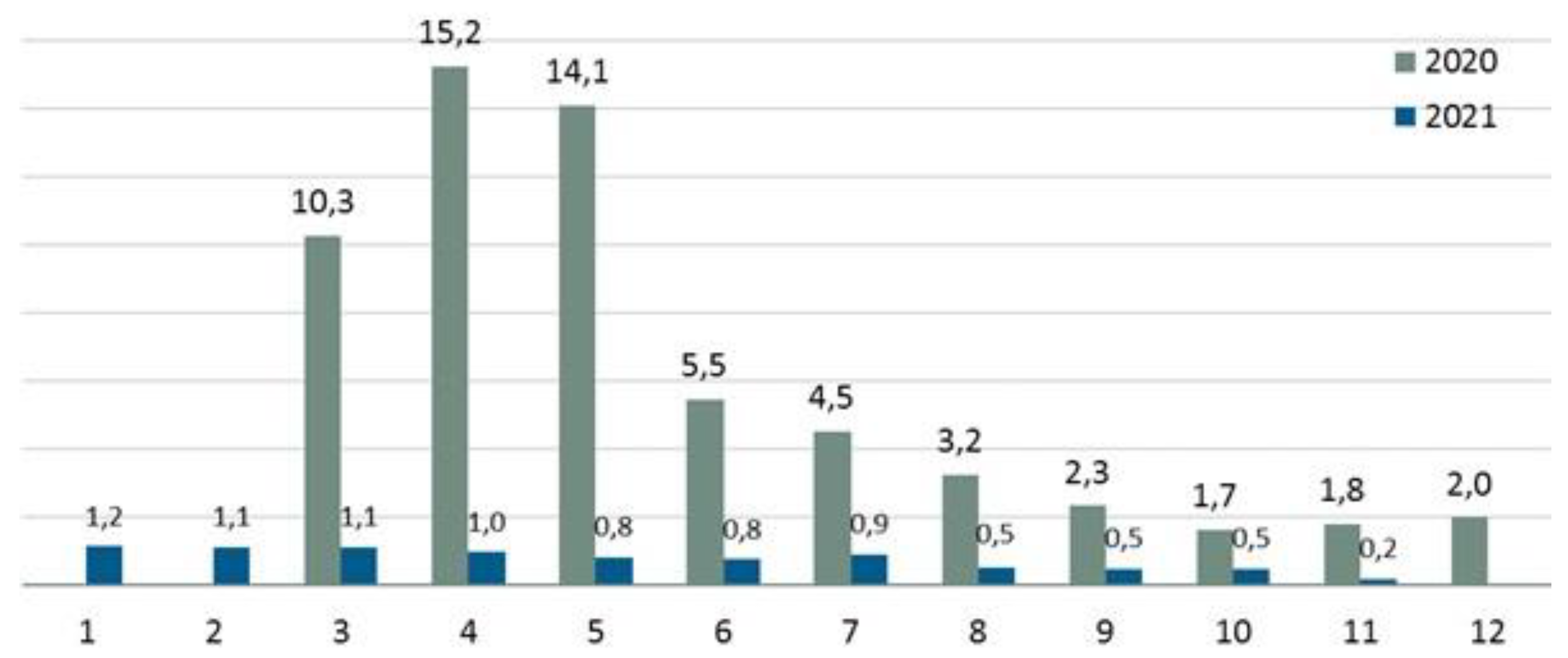

Some evidence for Prop. 2 is also provided by the application volumes for both types of loans across different time periods. The banks´ preference for the Instant Loan which imposes no risk on the banks should be stronger in periods of higher new infection numbers/stricter lockdown measures. This motivates

The data in

Table 2 support Prop. 3. We consider monthly growth rates of cumulated application volumes in 2020.

As the Entrepreneur Loans started on April 6 and the Instant Loans on April 22, the observed growth rates in May reflect an initialization bias. In the first half of June the lockdown still existed, perhaps motivating stronger growth of the Instant Loan. Then infection numbers went down strongly and optimism recurred which might explain the lower growth rates for the Instant Loan from July to October. The second infection wave started in October reviving pessimism which might have reversed the ranking of growth rates in November and December. In December the growth rate for the Instant Loan was about 2 ½ times as large as that for the Entrepreneur Loan. These numbers are consistent with Prop. 3.

This evidence is also consistent with Prop. 2. A negative shock impairs most firms´ ratings. The rating decline will be stronger for weaker firms (see Alter et al. 2023), these firms are affected, in particular. Therefore, the fraction of firms with a rather weak rating increases overproportionally. Thus, an increase in the number of Corona infections motivates banks even more to file more applications for the Instant Loan. This incentive may be stronger for weaker banks as suggested by Jiménez et al (2024) who find that in Spain weaker banks shift riskier corporate loans to taxpayers.

b) Uncertainty and Contract Choice

At the beginning of the pandemic, nobody could tell whether the crisis would be L- or V-shaped. Given a high level of uncertainty, firms had to prepare for temporary illiquidity shortages, but also for long-term changes in business models and liquidity needs. Similar to the great financial crisis, firms were very concerned about their liquidity and cut back cash outflows, and tried to secure credit lines as a liquidity backstop. Also banks were keen to secure their liquidity and reluctant to extend credit lines to firms. Firms and banks were awaiting public liquidity facilities. The KfW program offered these

14.

In the first lockdown, the high level of uncertainty about the duration of the lockdown and its implications for future cash flows motivated firms´ search for long-term loans with flexible disbursements and repayments. Only the Entrepreneur Loan offered a credit line with disbursement flexibility. Therefore the high level of uncertainty reinforced firms´ preference for the Entrepreneur Loan, but it raised the default risk and, thus, strengthened banks´ preference for the Instant Loan. This motivates

Proposition 4: Consider firms with a weak rating. Strong uncertainty in the initial months of the pandemic reinforced firms´ preference for the Entrepreneur Loan, but banks´ preference for the Instant Loan. When uncertainty decreased, banks` preference for the Instant Loan was weakened.

The ratio of applications for the Entrepreneur loan over those for the Instant Loan was 2.92 in May, 3.91 in June, 4.58 in July and 5.05 in August 2020. Hence, when uncertainty declined in the second quarter of 2020, the number of applications for the Entrepreneur loan increased relatively faster than that for the Instant Loan. This indicates less resistance of banks to the Entrepreneur Loan, imposing more risk on them. It allowed firms to benefit more from disbursement flexibility and lower interest rates of the Entrepreneur Loan, in line with Prop. 4.

Also, reputation may play a role. Participating in the pandemic aid program may be interpreted as a signal of financial weakness of a firm and, thus, impair reputation. The negative reputation effect is likely stronger if the firm gets an Instant Loan as this indicates a lower rating. Therefore, firms likely prefer the Entrepreneur Loan also for reputational reasons. Reputation damage together with the other constraints on firms, imposed by KfW, may also explain why about 1/3 of the larger Entrepreneur Loans, checked in detail by KfW, were fully repaid or canceled by the end of 2020. This ratio was only 15% for the smaller loans, presumably indicating less ability for early repayment of firms using Instant Loans.

c) Contract terms: maturity, seniority, collateral and covenants

The KfW program offers a free choice of the contract maturity up to prespecified limits. The other contract terms, in particular the interest rate, do not vary with the chosen maturity, thus ignoring the higher default risk of longer maturity. Moreover, an early retirement option is attached to these loans which is also costless. Thus, extending maturity is a costless option

15. Therefore, firms are likely to choose a long maturity regardless of their prospective

needs, thus not revealing these in a signaling equilibrium.This motivates Prop. 5a). However, as long as the loan is not completely repaid, banks and firms have to observe the covenants of the KfW-contract, restraining the freedom of banks and/or firms. Therefore they are costly to them. But they also provide a way to self-commit under asymmetric information so that other contract terms may be improved. This explains Prop. 5 b).

Proposition 5: a) Firms and banks prefer a KfW loan with longer maturity as the interest rate does not vary with maturity and early repayment is costless.

b) Firms and banks prefer a KfW loan with lower seniority and less collateral/ covenants unless these improve other contract terms.

In our discussions, the senior bank managers said that they try to optimize the bank´s position, even at the expense of KfW. They need to act in the interest of their employer. At the same time, they acknowledged that KfW should negotiate the terms of larger loans to attain a fair risk sharing. In case of automatic KfW acceptance, all terms are fixed, however.

Regarding proposition 5a), in most applications KfW observed requests for maturities between 5 and 10 years. Maturity of the Entrepreneur Loan was limited to 10 years for volumes up to € 0.8 m (later € 1.8 m) and to 6 years for larger volumes. By the end of November 2021, 13% of the Entrepreneur Loans had a maturity of only 2 years, 23 (31)% a maturity of 5 (6) years and 23 % a maturity of 10 years. For the Instant Loan with a maturity of at most 10 years the volume-weighted average maturity was 9.72 years as of November 2021. Thus, it appears that many firms chose a long maturity, in particular, weaker firms which opted for the Instant Loan. This confirms Prop. 5a).

Why did some firms opt for short maturities? In a separate investigation KfW included a sample of 4000 firms which received a KfW loan. 64% responded that they used the loan to pay their suppliers, 61% for personnel expenses and 43% for rent payments. Only 20% used the money for investments in new marketing channels even though KfW encouraged all sustainable investments. It appears that most firms used funds for short term liquidity needs.

The preference for a longer maturity should be particularly strong for weak firms. In line with this, Pagano (2024) finds for EU-countries that primarily weaker firms benefit from longer maturities and stronger interest rate reductions in public loans.

There may be also a conflict between firms/banks and KfW regarding the exercise of the early repayment option. If the firm has a relatively good rating and suffered less than expected from the pandemic, then the bank or other financiers may be happy to substitute the KfW-loan by a new loan at market terms. Also, the firm may wish to terminate the KfW-restrictions on its policy and reputation impairments of public aid. Early repayment signals financial strength of the firm. This motivates

As KfW does not know the rating of the firms which obtained small loans, there is no direct test of this hypothesis. But KfW knows the ratings of those firms whose risk it analyzed. As of November 2021, almost all firms with an investment grade repaid or canceled their loans so that the remaining loan portfolio comprised almost only loans from subinvestment grade firms. Insofar Prop. 6 is confirmed.

Also, the discussion with bank managers addressed loan substitution. The rules of the KfW-program prohibit substitution of bank loans by a KfW loan. But enforcement of this rule is very difficult. Consider, for example, firms which choose KfW loans with long maturity. Often bank loans have shorter maturities. Therefore, the KfW loan may be used to repay bank loans. This kind of substitution could be curtailed by shorter maturities of the KfW loan. If KfW negotiates contract terms with the banks, it might urge banks to extend the maturity of existing bank loans. Looking at the cited KfW-study, only 20% of the firms used the KfW loan for investments. Most used these loans for paying off debt claims. This indicates delayed loan substitution. The KfW manager gave examples of applications for large KfW-loans where KfW checked the risk carefully. A discussion emerged between KfW and some banks so that KfW actually insisted on an extension of the maturity of the bank loans. Sometimes banks refused and retracted the application. There are even cases when applications for high loan volumes were replaced by applications for small volumes - which were automatically granted. These are clearly examples of an inefficient self-selection scheme.

Several studies investigate potential inefficiencies in public lending which might show up in loan substitution. Goldberg et al (2024) observe loan substitution for almost all firms that received guaranteed loans in Italy and Spain and for about ¾ of firms in France and Germany. They expect substitution to be driven by banks for quite risky firms and by resilient firms, consistent with Prop. 2. Similarly, Cascarino et al (2022) also find substantial loan substitution in Italy. The ratio of all loans over the guarantee amount is rather independent of firm characteristics, it is highest for guarantees with 100% risk coverage. According to Altavilla et al (2021), in the EU-countries loan substitution is higher for smaller, riskier firms, also if healthier banks are involved. Pagano (2024) investigates loan substitution over the period February to August 2020 in France, Germany, Italy and Spain and finds positive substitution of roughly 30% for banks with a guaranteed loan. Substitution is higher for weaker firms.

Evaluation of undesirable loan substitution requires a model of what should be expected in the absence of misbehavior of firms and banks. Lucas (2020) and Hong et al (2024) expect a significant share of public funds to be retained rather than spent because of depressed economic activity, reducing the need for a working balance, and because of precautionary hoarding money in a phase of strong uncertainty about future cash needs

16. A convenient way of profitable hoarding is to use public money for repaying costly short term bank loans, upholding credit lines for future cash needs. Such hoarding stabilizes firms financially and may be socially desirable. Moreover, the specifications of public funds may play a role. For instance, in Germany the Instant Loan offered by the NDB requires the firm to fully withdraw the loan within one month, otherwise the Instant Loan expires. This may enforce temporary loan substitution.

However, if cheap public funding is mainly used to substitute for expensive bank funding and to transfer default risk to the NDB, this violates the “need model” and indicates adverse selection. Moral hazard is likely if after some time “need” is gone, but public money is not repaid, but used to substitute for private loans (delayed substitution). Thus, the flipside of Prop. 6 is delayed repayment of the public loan. Testing for such behavior requires long term observations.

KfW attempts to constrain misbehavior of banks. From time to time, it examines ex post a bank´s behavior in accepted loan deals together with default rates. If KfW detects misbehavior, it may ask the bank for indemnification of losses. KfW exercises this examen option rarely, however.

Direct Participation In Syndicate Lending

Direct Participation In Syndicate Lending  Entrepreneur Loan

Entrepreneur Loan  Entrepreneur Loan for Young Firms

Entrepreneur Loan for Young Firms  Instant Loan.

Instant Loan.

Direct Participation In Syndicate Lending

Direct Participation In Syndicate Lending  Entrepreneur Loan

Entrepreneur Loan  Entrepreneur Loan for Young Firms

Entrepreneur Loan for Young Firms  Instant Loan.

Instant Loan.