Submitted:

08 January 2026

Posted:

13 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

The optimal dietary balance between n‑6 and n‑3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), the safe upper intake of n‑6 PUFAs—particularly linoleic acid—and the physiological consequences of their metabolic competition remain unresolved in the context of the Western diet. Since the 1980s, Bill Lands and colleagues have argued that high n‑6 PUFA intake can shift the balance of n‑3–derived pathways and eicosanoid signaling, potentially influencing processes relevant to non‑communicable diseases. Despite its potential public‑health implications, this hypothesis has received limited systematic attention. In this narrative review, we synthesize key aspects of Lands’ work, evaluate supportive and contradictory evidence, and highlight mechanistic insights into lipid competition and inflammatory regulation. We conclude that these unresolved but testable hypotheses warrant renewed investigation, as their corroboration could reshape dietary guidelines and strategies for chronic disease prevention.

Keywords:

1. Introduction - Why This Article Was Written

2. The Essence of Lands’ Hypotheses

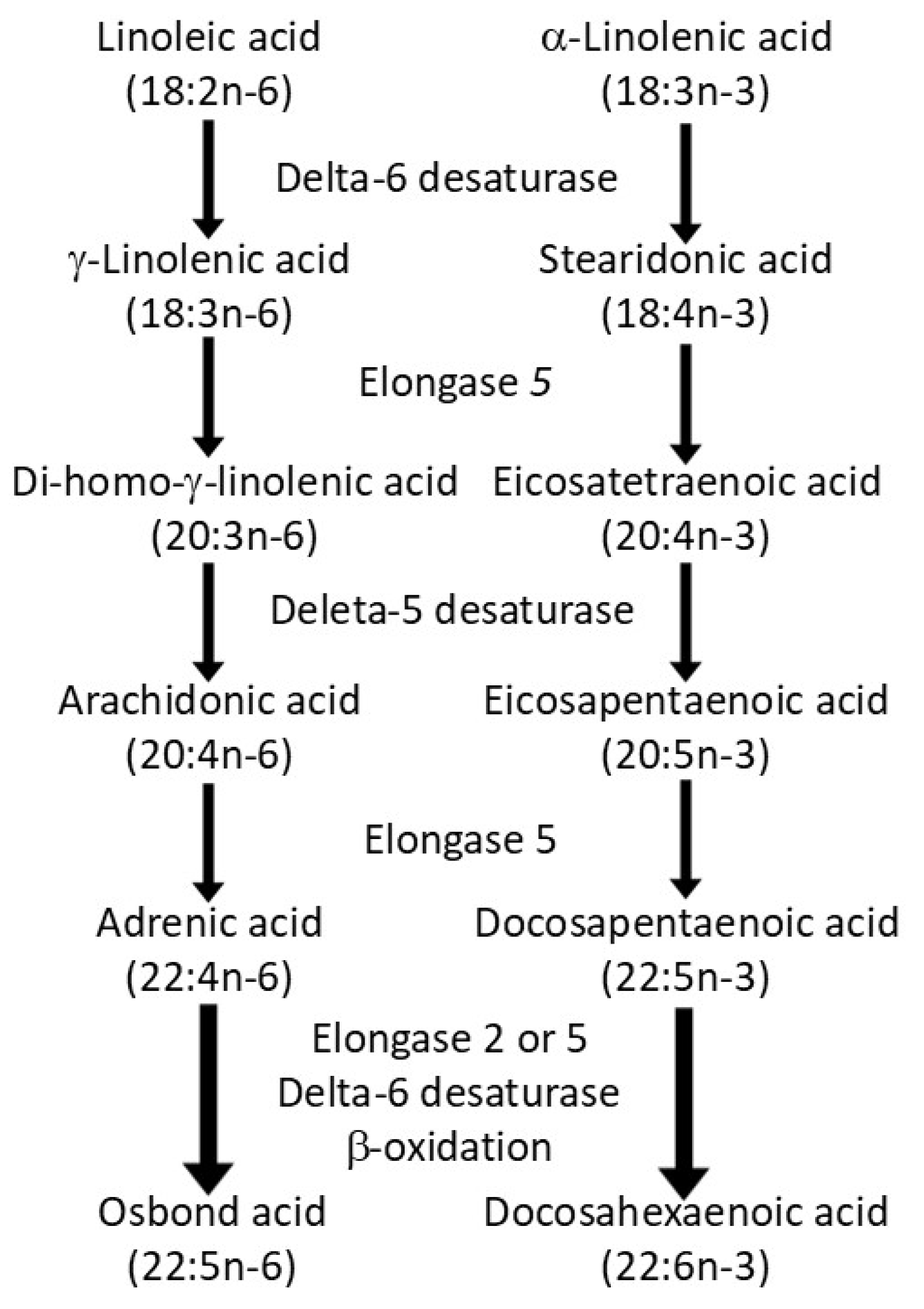

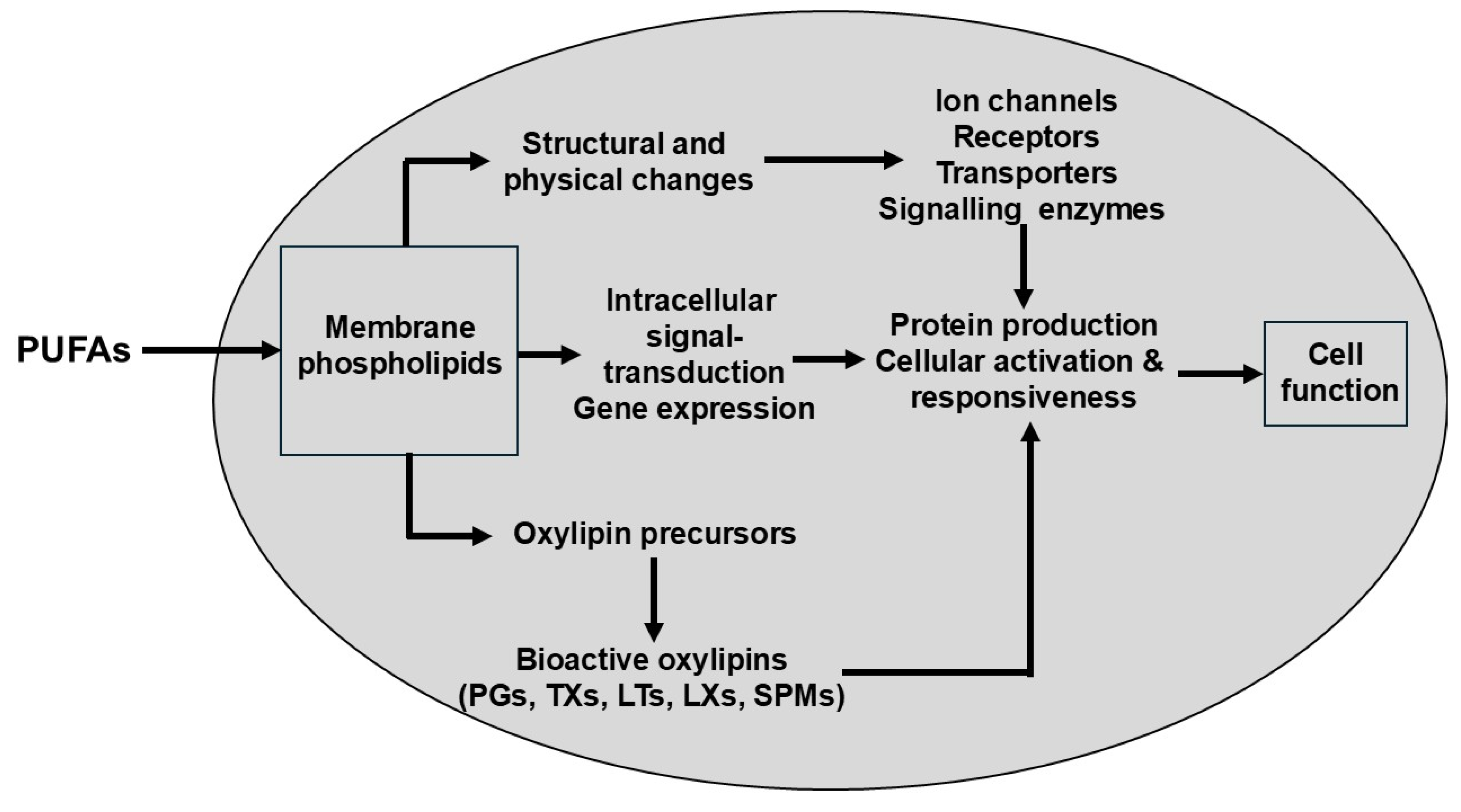

2.1. The Dietary Mixture of Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (PUFAs) Determines Cellular Fatty Acid Profiles and Thereby Shapes the Non-Energetic Biological Actions of These Lipids

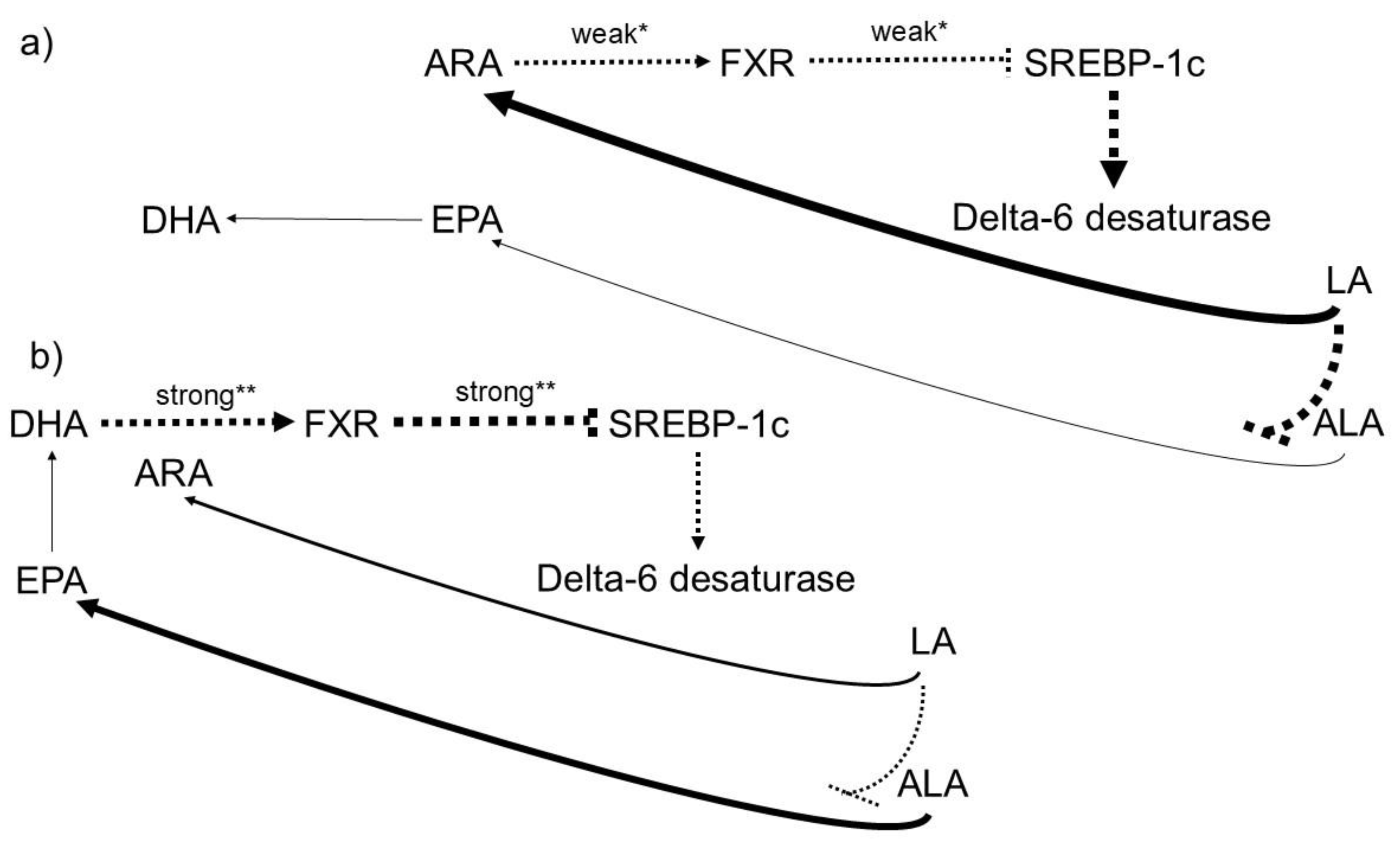

2.2. n-6 and n-3 Highly Unsaturated Fatty Acids (HUFAs) Influence Each Other Metabolically, Differ in Their Biochemical Efficacy, and Give Rise to Distinct Organ- and System-Level Functions

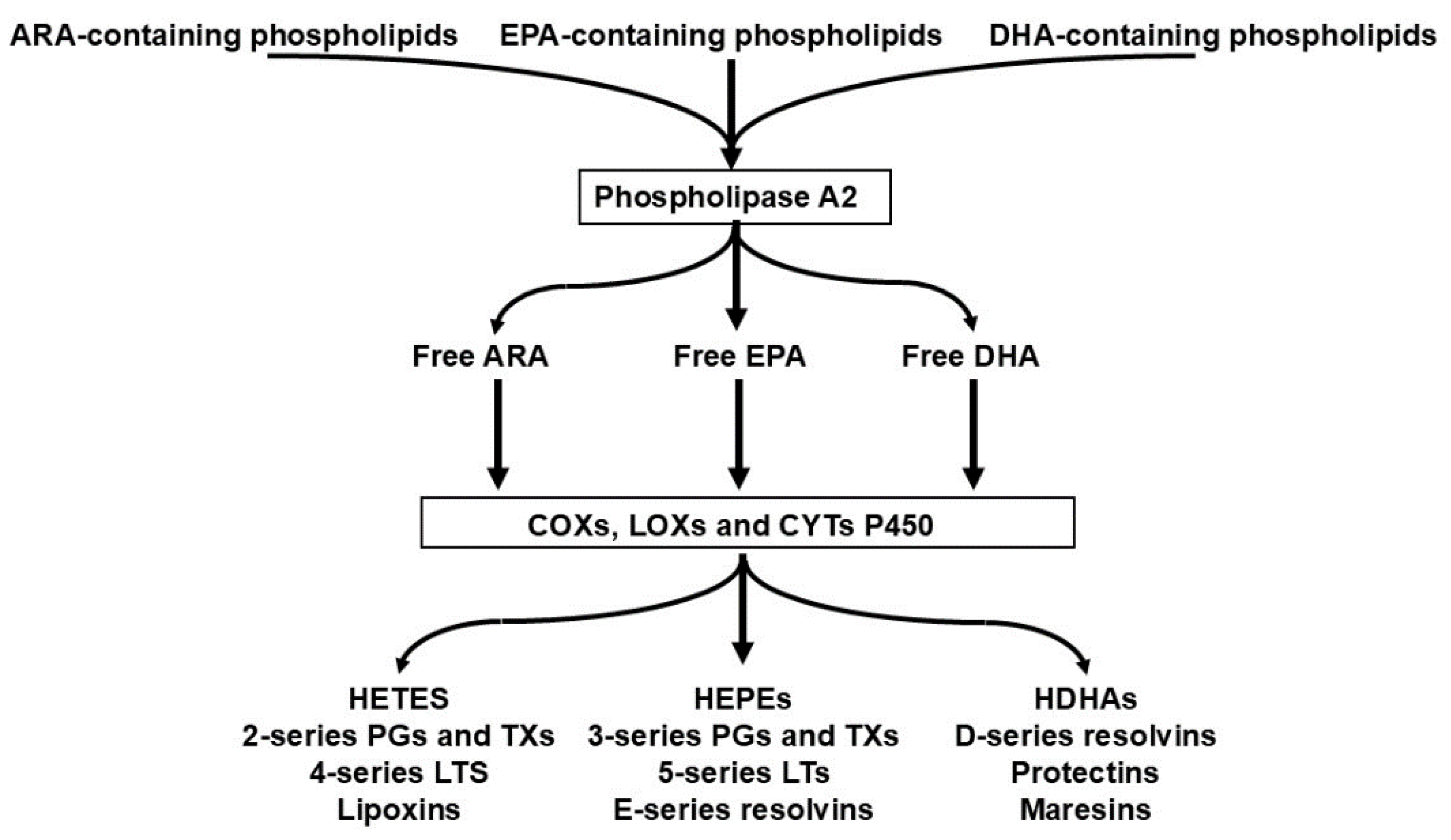

2.3. The Competition of n-6 and n3 HUFAs for Shared Metabolic Enzymes (COX, LOX, CYP) Is the Primary Determinant of Downstream Lipid Mediator Profiles

2.4. The Quantitative Relationship Between Dietary PUFA Intake and HUFA Composition Is Predictable and Can Be Modelled with High Accuracy, Enabling Mechanistic Forecasting of Biological Outcomes

2.5. The Long Standing Neglect of Dietary PUFA Imbalance May Contribute to the Continued Rise of Non-Communicable Diseases

2.6. Dietary Interventions Can Lower the Percentage of n-6 in HUFA, with Potential Health Benefits and Associated Reductions in Healthcare Costs

2.7. The Individual n-6 HUFA Profile Serves as a Valuable Surrogate Biomarker Because It Reflects Both Dietary Inputs and Pathophysiological Outcomes

2.8. Combining Reduced n-6 with Increased n-3 PUFA Intake Most Effectively Lowers the Percentage of n-6 in HUFA, Owing to the Predictable Quantitative Dynamics of the Competing HUFA Families

2.9. Failure to Account for the Population Wide Oversupply of n 6 PUFAs May Help Explain Inconsistent Results in Randomized Controlled Trials Evaluating the Clinical Efficacy of n 3 PUFAs.

2.10. Measures of Basal as Well as Final n-6 and n-3 HUFA Status Should Be Considered Important and Valid Biomarkers for Designing and Monitoring Effective Nutritional Strategies

2.11. A Range of Non-Communicable Diseases Appears to Be Associated with Elevated n-6 HUFA Levels, and the Underlying Pathophysiological Mechanisms Are Increasingly Understood

2.12. In Cardiovascular Disease (CVD), Preliminary Evidence Already Suggests a Potential Causal Role for an Increased n-6 HUFA Profile

2.13. Achieving An n-6 HUFA Percentage near 50% May Help Reduce Annual Healthcare Expenditures and Improve the Cost Effectiveness of Public Health Interventions

3. What Evidence-Based Concepts Support Lands’ Hypotheses?

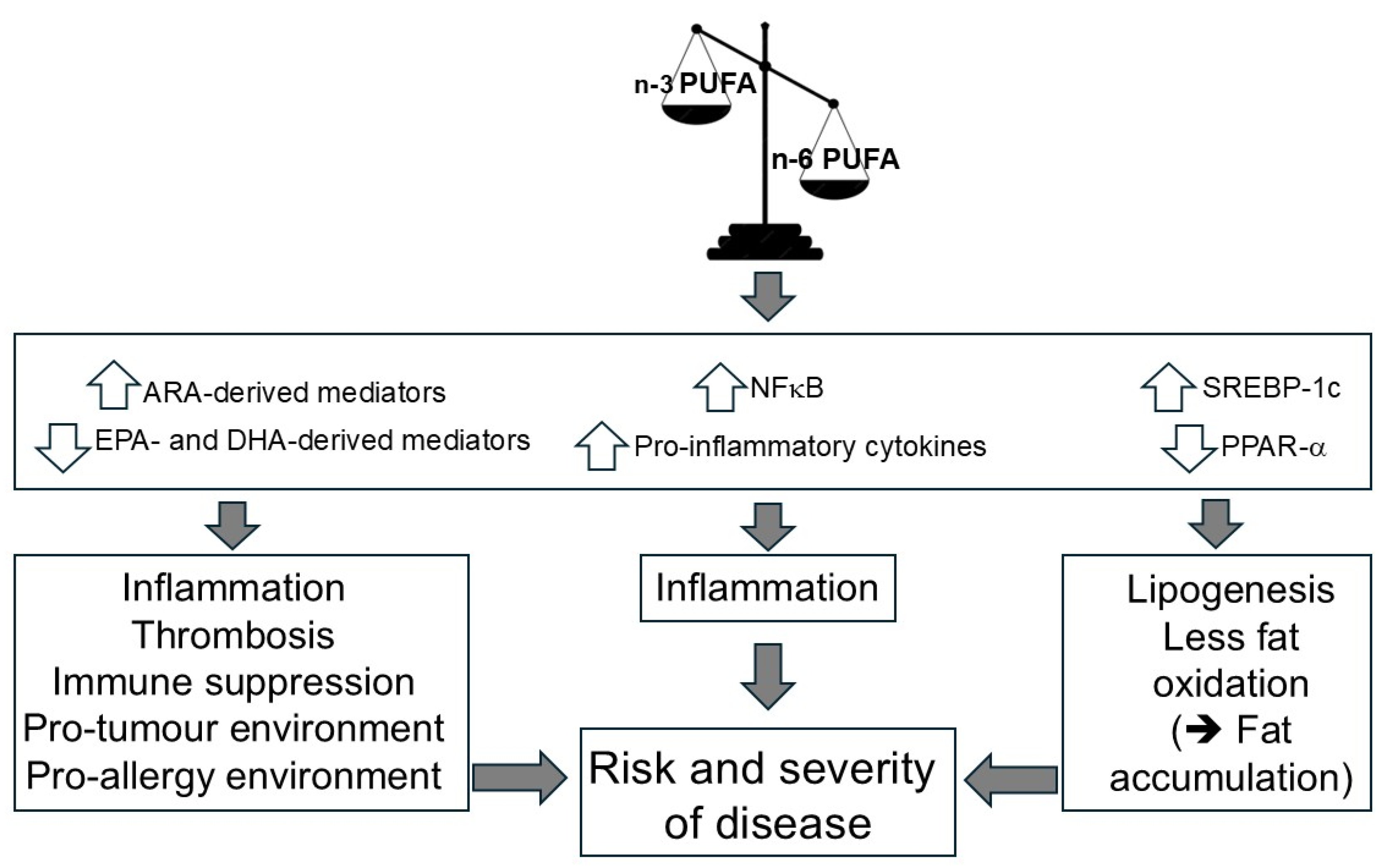

3.1. The n-6/n-3 HUFA Balance Governs Inflammatory, Immunologic, and Metabolic Signaling

3.2. Excessive n-6 PUFA and HUFA Abundance Drives Molecular, Cellular, and Organ-Level Pathomechanisms Linked to Chronic Disease

3.3. Increasing Linoleic Acid Intake May Amplify HUFA-Mediated Pathomechanisms in n-6–Dominant Physiological States

3.4. The Concept of a Dietary Toxicity Threshold for Linoleic Acid Appears to Be Supported by Available Evidence, Yet Remains Debated

3.5. The Availability of n-3 PUFAs in Individuals Consuming the “Western Diet” High in n 6 PUFAs Is Steadily Declining.

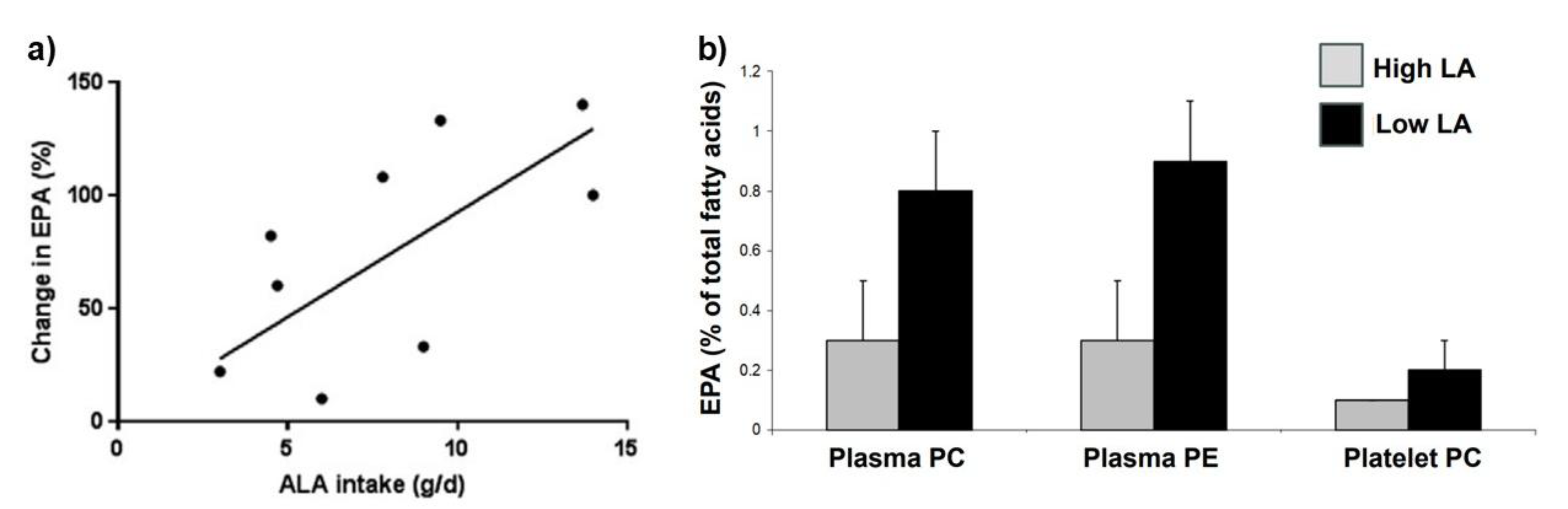

- An impairment of the conversion of ALA to stearidonic acid (18:4 n-3) and on to EPA (20:5 n-3) due to competition of LA with ALA for D6-desaturase [159].

- An impairment of the incorporation of EPA, DPA (22:5n-3), and DHA into cell membranes due to competition with ARA (which is abundant) for esterification into the sn-2 position of phospholipids [91].

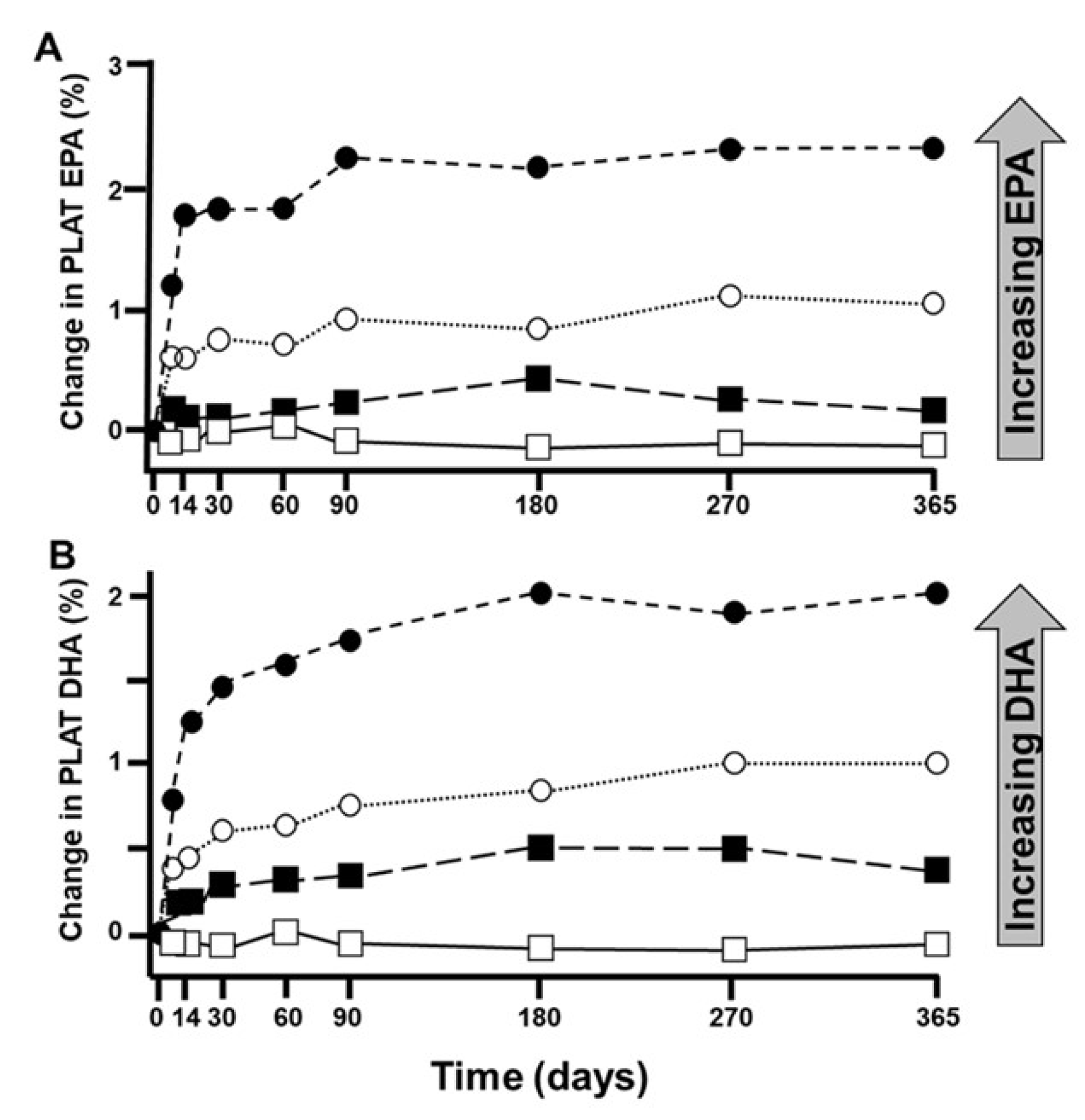

3.6. The Appropriate Dietary n-3 HUFA Uptake Depends on the Individual Cellular n-6 HUFA Availability

4. What Data and Concepts May Disprove Lands' Hypotheses?

5. Summary and Concluding Remarks

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- O'Donnell, VB. New appreciation for an old pathway: the Lands Cycle moves into new arenas in health and disease. Biochem Soc Trans. 2022, 50(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lands, B. Historical perspectives on the impact of n-3 and n-6 nutrients on health. Prog Lipid Res. 2014, 55, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lands, B. Highly unsaturated fatty acids (HUFA) mediate and monitor food's impact on health. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2017, 133, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lands, B. Benefit-Risk Assessment of Fish Oil in Preventing Cardiovascular Disease. Drug Saf. 2016, 39(9), 787–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lands, B. Omega-3 PUFAs Lower the Propensity for Arachidonic Acid Cascade Overreactions. Biomed Res Int. 2015, 2015, 285135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, PC. Eicosanoids. Essays Biochem. 2020, 64(3), 423–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, N; Serhan, CN. Specialized pro-resolving mediator network: an update on production and actions. Essays Biochem. 2020, 64(3), 443–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, PC. Functional Roles of Fatty Acids and Their Effects on Human Health. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2015, 39(1 Suppl), 18S–32S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lands, B; Bibus, D; Stark, KD. Dynamic interactions of n-3 and n-6 fatty acid nutrients. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 2018, 136, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

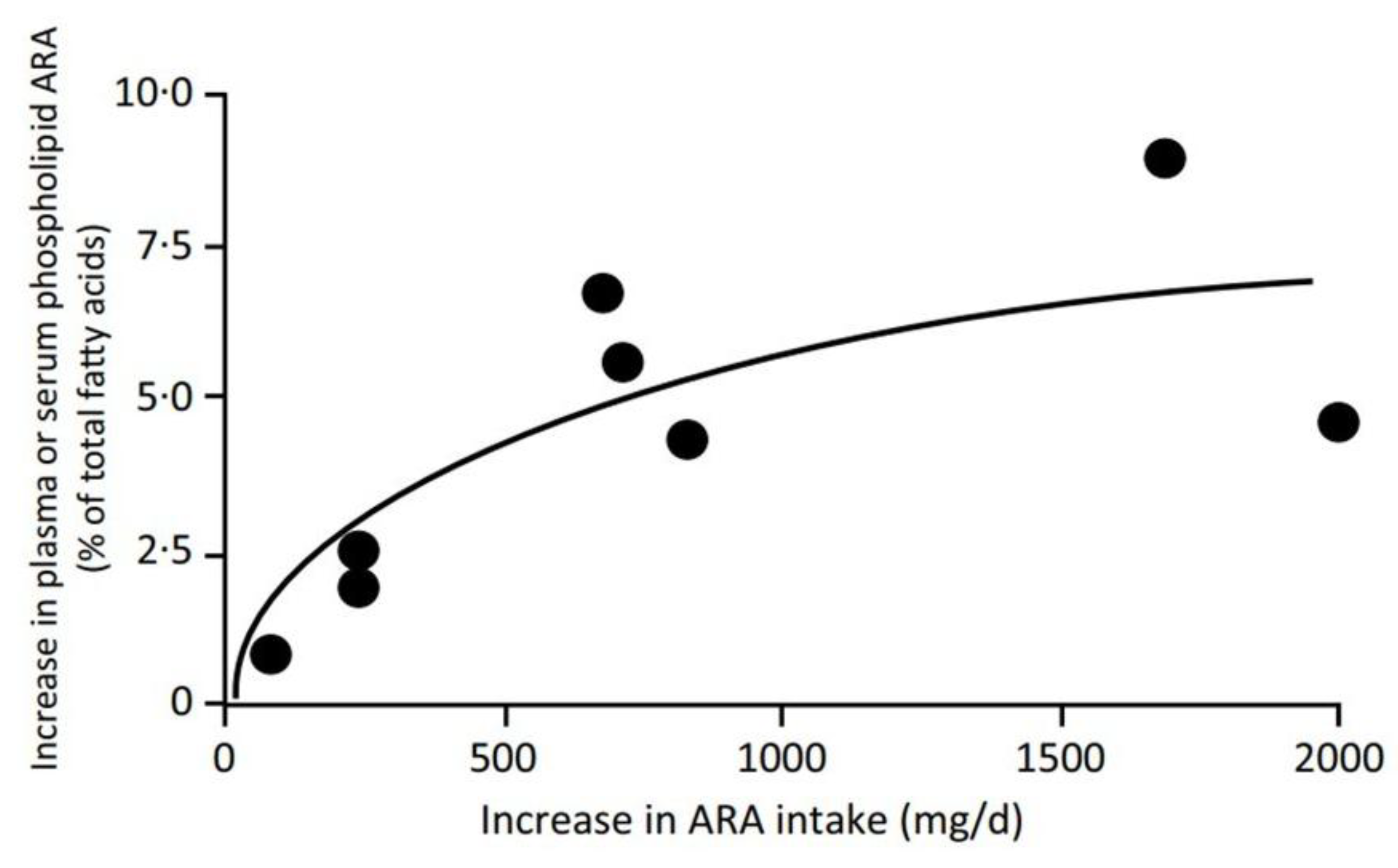

- Rett, BS; Whelan, J. Increasing dietary linoleic acid does not increase tissue arachidonic acid content in adults consuming Western-type diets: a systematic review. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2011, 8, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, PC. Dietary arachidonic acid: harmful, harmless or helpful? Br J Nutr. 2007, 98(3), 451–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagve, TA; Christophersen, BO. Effect of dietary fats on arachidonic acid and eicosapentaenoic acid biosynthesis and conversion to C22 fatty acids in isolated rat liver cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 1984, 796(2), 205–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, HM; Brenna, JT. Simultaneous measurement of desaturase activities using stable isotope tracers or a nontracer method. Anal Biochem. 1998, 261(1), 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christophersen, BO; Hagve, TA; Christensen, E; Johansen, Y; Tverdal, S. Eicosapentaenoic- and arachidonic acid metabolism in isolated liver cells. Scand J Clin Lab Invest Suppl. 1986, 184, 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, EJ; Miles, EA; Burdge, GC; Yaqoob, P; Calder, PC. Metabolism and functional effects of plant-derived omega-3 fatty acids in humans. Prog Lipid Res. 2016, 64, 30–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, JK; McDonald, BE; Gerrard, JM; Bruce, VM; Weaver, BJ; Holub, BJ. Effect of dietary alpha-linolenic acid and its ratio to linoleic acid on platelet and plasma fatty acids and thrombogenesis. Lipids 1993, 28(9), 811–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, PC; Campoy, C; Eilander, A; Fleith, M; Forsyth, S; Larsson, PO; et al. A systematic review of the effects of increasing arachidonic acid intake on PUFA status, metabolism and health-related outcomes in humans. Br J Nutr. 2019, 121(11), 1201–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, LM; Walker, CG; Mander, AP; West, AL; Madden, J; Gambell, JM; et al. Incorporation of eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acids into lipid pools when given as supplements providing doses equivalent to typical intakes of oily fish. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012, 96(4), 748–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, CG; West, AL; Browning, LM; Madden, J; Gambell, JM; Jebb, SA; et al. The Pattern of Fatty Acids Displaced by EPA and DHA Following 12 Months Supplementation Varies between Blood Cell and Plasma Fractions. Nutrients 2015, 7(8), 6281–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameur, A; Enroth, S; Johansson, A; Zaboli, G; Igl, W; Johansson, AC; et al. Genetic adaptation of fatty-acid metabolism: a human-specific haplotype increasing the biosynthesis of long-chain omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids. Am J Hum Genet. 2012, 90(5), 809–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenna, JT; Kothapalli, KSD. New understandings of the pathway of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2022, 25(2), 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothapalli, KSD; Park, HG; Brenna, JT. Polyunsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis pathway and genetics. implications for interindividual variability in prothrombotic, inflammatory conditions such as COVID-19. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 2020, 162, 102183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, G; Li, YN; Davies, JR; Block, RC; Kothapalli, KS; Brenna, JT; et al. Fatty acid desaturase insertion-deletion polymorphism rs66698963 predicts colorectal polyp prevention by the n-3 fatty acid eicosapentaenoic acid: a secondary analysis of the seAFOod polyp prevention trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2024, 120(2), 360–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hull, MA; Sprange, K; Hepburn, T; Tan, W; Shafayat, A; Rees, CJ; et al. Eicosapentaenoic acid and aspirin, alone and in combination, for the prevention of colorectal adenomas (seAFOod Polyp Prevention trial): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 2 × 2 factorial trial. Lancet 2018, 392(10164), 2583–2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calder, PC. Very long-chain n-3 fatty acids and human health: fact, fiction and the future. Proc Nutr Soc. 2018, 77(1), 52–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troesch, B; Eggersdorfer, M; Laviano, A; Rolland, Y; Smith, AD; Warnke, I; et al. Expert Opinion on Benefits of Long-Chain Omega-3 Fatty Acids (DHA and EPA) in Aging and Clinical Nutrition. Nutrients 2020, 12(9), 2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djuricic, I; Calder, PC. Beneficial Outcomes of Omega-6 and Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids on Human Health: An Update for 2021. Nutrients 2021, 13(7), 2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lands, B. A critique of paradoxes in current advice on dietary lipids. Prog Lipid Res. 2008, 47(2), 77–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lands, B; Lamoreaux, E. Using 3-6 differences in essential fatty acids rather than 3/6 ratios gives useful food balance scores. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2012, 9(1), 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohrhauer, H; Holman, RT. The effect of dose level of essential fatty acids upon fatty acid composition of the rat liver. J. Lipid Res. 1963, 4, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lands, WE. Diets could prevent many diseases. Lipids 2003, 38(4), 317–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serhan, CN. Discovery of specialized pro-resolving mediators marks the dawn of resolution physiology and pharmacology. Mol Aspects Med. 2017, 58, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serhan, CN; Chiang, N; Dalli, J. New pro-resolving n-3 mediators bridge resolution of infectious inflammation to tissue regeneration. Mol Aspects Med. 2018, 64, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serhan, CN; Levy, BD. Proresolving Lipid Mediators in the Respiratory System. Annu Rev Physiol. 2025, 87(1), 491–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, DN; Giddens, DP; Zarins, CK; Glagov, S. Pulsatile flow and atherosclerosis in the human carotid bifurcation. Positive correlation between plaque location and low oscillating shear stress. Arteriosclerosis 1985, 5(3), 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddens, DP; Zarins, CK; Glagov, S. The role of fluid mechanics in the localization and detection of atherosclerosis. J Biomech Eng. 1993, 115(4B), 588–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theofilis, P; Sagris, M; Oikonomou, E; Antonopoulos, AS; Siasos, G; Tsioufis, C; et al. Inflammatory Mechanisms Contributing to Endothelial Dysfunction. Biomedicines 2021, 9(7), 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z; Deng, L; Fang, F; Zhao, T; Zhang, Y; Li, G; et al. Endothelial cells under disturbed flow release extracellular vesicles to promote inflammatory polarization of macrophages and accelerate atherosclerosis. BMC Biol. 2025, 23(1), 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, M; DeLong, CJ; Hong, YH; Rieke, CJ; Song, I; Sidhu, RS; et al. Enzymes and receptors of prostaglandin pathways with arachidonic acid-derived versus eicosapentaenoic acid-derived substrates and products. J Biol Chem. 2007, 282(31), 22254–22266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, TH; Sethi, T; Crea, AE; Peters, W; Arm, JP; Horton, CE; et al. Characterization of leukotriene B3: comparison of its biological activities with leukotriene B4 and leukotriene B5 in complement receptor enhancement, lysozyme release and chemotaxis of human neutrophils. Clin Sci (Lond) 1988, 74(5), 467–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsden, CE; Hibbeln, JR; Lands, WE. Letter to the Editor re: Linoleic acid and coronary heart disease. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids (2008), by W.S. Harris. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2009, 80(1), 77; author reply 77–78. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, JH; Lemaitre, RN; King, IB; Song, X; Psaty, BM; Siscovick, DS; et al. Circulating omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids and total and cause-specific mortality: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Circulation 2014, 130(15), 1245–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marklund, M; Wu, JHY; Imamura, F; Del Gobbo, LC; Fretts, A; de Goede, J; et al. Biomarkers of Dietary Omega-6 Fatty Acids and Incident Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality. Circulation 2019, 139(21), 2422–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercola, J; D'Adamo, CR. Linoleic Acid: A Narrative Review of the Effects of Increased Intake in the Standard American Diet and Associations with Chronic Disease. Nutrients 2023, 15(14), 3129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, KH; Harris, WS; Belury, MA; Kris-Etherton, PM; Calder, PC. Beneficial effects of linoleic acid on cardiometabolic health: an update. Lipids Health Dis. 2024, 23(1), 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, KS; Maki, KC; Calder, PC; Belury, MA; Messina, M; Kirkpatrick, CF; et al. Perspective on the health effects of unsaturated fatty acids and commonly consumed plant oils high in unsaturated fat. Br J Nutr. 2024, 132(8), 1039–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeppke, R; Taitel, M; Haufle, V; Parry, T; Kessler, RC; Jinnett, K. Health and productivity as a business strategy: a multiemployer study. J Occup Environ Med. 2009, 51(4), 411–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lands, B. Prevent the cause, not just the symptoms. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2011, 96(1-4), 90–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essential fatty acids - Balancing omega 3 and 6 fats gives better health. Available online: http://efaeducation.org/omega-3-6-apps/.

- Clark, C; Lands, B. Creating benefits from omega-3 functional foods and nutraceuticals. Food Nutr. Sci. 2015, 6, 1613–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, PC; Deckelbaum, RJ. Dietary lipids: more than just a source of calories. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 1999, 2(2), 105–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, PC. Fatty acids and inflammation: the cutting edge between food and pharma. Eur J Pharmacol. 2011, 668 Suppl 1, S50–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calder, PC. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and inflammatory processes: Nutrition or pharmacology? Brit. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013, 75, 645–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calder, PC. Comment on Christiansen et al.: When food met pharma. Brit. J. Nutr. 2015, 114, 1109–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyall, SC; Balas, L; Bazan, NG; Brenna, JT; Chiang, N; da Costa Souza, F; et al. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and fatty acid-derived lipid mediators: Recent advances in the understanding of their biosynthesis, structures, and functions. Prog Lipid Res. 2022, 86, 101165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, ML; Lorenzetti, F. Role of eicosanoids in liver repair, regeneration and cancer. Biochem Pharmacol. 2021, 192, 114732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigrahy, D; Gilligan, MM; Serhan, CN; Kashfi, K. Resolution of inflammation: An organizing principle in biology and medicine. Pharmacol Ther. 2021, 227, 107879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredman, G; Serhan, CN. Specialized pro-resolving mediators in vascular inflammation and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2024, 21(11), 808–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serhan, CN; Sulciner, ML. Resolution medicine in cancer, infection, pain and inflammation: are we on track to address the next Pandemic? Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2023, 42(1), 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schebb, NH; Kühn, H; Kahnt, AS; Rund, KM; O'Donnell, VB; Flamand, N; et al. Formation, Signaling and Occurrence of Specialized Pro-Resolving Lipid Mediators-What is the Evidence so far? Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 838782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Donnell, VB; Schebb, NH; Milne, GL; Murphy, MP; Thomas, CP; Steinhilber, D; et al. Failure to apply standard limit-of-detection or limit-of-quantitation criteria to specialized pro-resolving mediator analysis incorrectly characterizes their presence in biological samples. Nat Commun. 2023, 14(1), 7172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parchem, K; Letsiou, S; Petan, T; Oskolkova, O; Medina, I; Kuda, O; et al. Oxylipin profiling for clinical research: Current status and future perspectives. Prog Lipid Res. 2024, 95, 101276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harayama, T; Shimizu, T. Roles of polyunsaturated fatty acids, from mediators to membranes. J Lipid Res. 2020, 61(8), 1150–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Rodas, MC; Valenzuela, R; Echeverría, F; Rincón-Cervera, MÁ; Espinosa, A; Illesca, P; et al. Supplementation with Docosahexaenoic Acid and Extra Virgin Olive Oil Prevents Liver Steatosis Induced by a High-Fat Diet in Mice through PPAR-α and Nrf2 Upregulation with Concomitant SREBP-1c and NF-kB Downregulation. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2017, 61(12), 1700479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wall, R; Ross, RP; Fitzgerald, GF; Stanton, C. Fatty acids from fish: the anti-inflammatory potential of long-chain omega-3 fatty acids. Nutr Rev. 2010, 68(5), 280–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, JY; Sohn, KH; Rhee, SH; Hwang, D. Saturated fatty acids, but not unsaturated fatty acids, induce the expression of cyclooxygenase-2 mediated through Toll-like receptor 4. J Biol Chem. 2001, 276(20), 16683–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y; Joshi-Barve, S; Barve, S; Chen, LH. Eicosapentaenoic acid prevents LPS-induced TNF-alpha expression by preventing NF-kappaB activation. J Am Coll Nutr. 2004, 23(1), 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weatherill, AR; Lee, JY; Zhao, L; Lemay, DG; Youn, HS; Hwang, DH. Saturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids reciprocally modulate dendritic cell functions mediated through TLR4. J Immunol. 2005, 174(9), 5390–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, PC. n-3 PUFA and inflammation: from membrane to nucleus and from bench to bedside. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 2020, 79(4), 404–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Caterina, R; Spiecker, M; Solaini, G; Basta, G; Bosetti, F; Libby, P; et al. The inhibition of endothelial activation by unsaturated fatty acids. Lipids 1999, 34 Suppl, S191–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, A; Repa, JJ; Evans, RM; Mangelsdorf, DJ. Nuclear receptors and lipid physiology: opening the X-files. Science 2001, 294(5548), 1866–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kota, BP; Huang, TH; Roufogalis, BD. An overview on biological mechanisms of PPARs. Pharmacol Res. 2005, 51(2), 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadi, AR; Shirani, F; Abiri, B; Siavash, M; Haghighi, S; Akbari, M. Impact of omega-3 fatty acids supplementation on the gene expression of peroxisome proliferator activated receptors-γ, α and fibroblast growth factor-21 serum levels in patients with various presentation of metabolic conditions: a GRADE assessed systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of clinical trials. Front Nutr. 2023, 10, 1202688. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bensinger, SJ; Tontonoz, P. Integration of metabolism and inflammation by lipid-activated nuclear receptors. Nature 2008, 454(7203), 470–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poynter, ME; Daynes, RA. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha activation modulates cellular redox status, represses nuclear factor-kappaB signaling, and reduces inflammatory cytokine production in aging. J Biol Chem. 1998, 273(49), 32833–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H; Ruan, XZ; Powis, SH; Fernando, R; Mon, WY; Wheeler, DC; Moorhead, JF; Varghese, Z. EPA and DHA reduce LPS-induced inflammation responses in HK-2 cells: evidence for a PPAR-gamma-dependent mechanism. Kidney Int. 2005, 67(3), 867–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, E; Wall, R; Fitzgerald, GF; Ross, RP; Stanton, C. Health implications of high dietary omega-6 polyunsaturated Fatty acids. J Nutr Metab. 2012, 2012, 539426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yessoufou, A; Wahli, W. Multifaceted roles of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) at the cellular and whole organism levels. Swiss Med Wkly. 2010, 140, w13071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botta, M; Audano, M; Sahebkar, A; Sirtori, CR; Mitro, N; Ruscica, M. PPAR Agonists and Metabolic Syndrome: An Established Role? Int J Mol Sci. 2018, 19(4), 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperling, LS; Nelson, JR. History and future of omega-3 fatty acids in cardiovascular disease. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016, 32(2), 301–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, PC. Omega-3 fatty acids and metabolic partitioning of fatty acids within the liver in the context of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2022, 25(4), 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzini, A; Lunger, L; Demetz, E; Hilbe, R; Weiss, G; Ebenbichler, C; et al. The Role of Omega-3 Fatty Acids in Reverse Cholesterol Transport: A Review. Nutrients 2017, 9(10), 1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teran-Garcia, M; Adamson, AW; Yu, G; Rufo, C; Suchankova, G; Dreesen, TD; Tekle, M; et al. Polyunsaturated fatty acid suppression of fatty acid synthase (FASN): evidence for dietary modulation of NF-Y binding to the Fasn promoter by SREBP-1c. Biochem J. 2007, 402(3), 591–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J; Nakamura, MT; Cho, HP; Clarke, SD. Sterol regulatory element binding protein-1 expression is suppressed by dietary polyunsaturated fatty acids. A mechanism for the coordinate suppression of lipogenic genes by polyunsaturated fats. J Biol Chem. 1999, 274(33), 23577–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J; Teran-Garcia, M; Park, JH; Nakamura, MT; Clarke, SD. Polyunsaturated fatty acids suppress hepatic sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1 expression by accelerating transcript decay. J Biol Chem. 2001, 276(13), 9800–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howell, G, 3rd; Deng, X; Yellaturu, C; Park, EA; Wilcox, HG; Raghow, R; et al. N-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids suppress insulin-induced SREBP-1c transcription via reduced trans-activating capacity of LXRalpha. Biochim Biophys Acta 2009, 1791(12), 1190–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, G; Ecker, J. The opposing effects of n-3 and n-6 fatty acids. Prog Lipid Res. 2008, 47(2), 147–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuzaka, T; Shimano, H; Yahagi, N; Amemiya-Kudo, M; Yoshikawa, T; Hasty, AH; et al. Dual regulation of mouse Delta(5)- and Delta(6)-desaturase gene expression by SREBP-1 and PPARalpha. J Lipid Res. 2002, 43(1), 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarty, MF; DiNicolantonio, JJ. Minimizing Membrane Arachidonic Acid Content as a Strategy for Controlling Cancer: A Review. Nutr Cancer 2018, 70(6), 840–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, A; Yu, J; Lew, JL; Huang, L; Wright, SD; Cui, J. Polyunsaturated fatty acids are FXR ligands and differentially regulate expression of FXR targets. DNA Cell Biol. 2004, 23(8), 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesen, RW; Innis, SM. Linoleic acid is associated with lower long-chain n-6 and n-3 fatty acids in red blood cell lipids of Canadian pregnant women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010, 91(1), 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

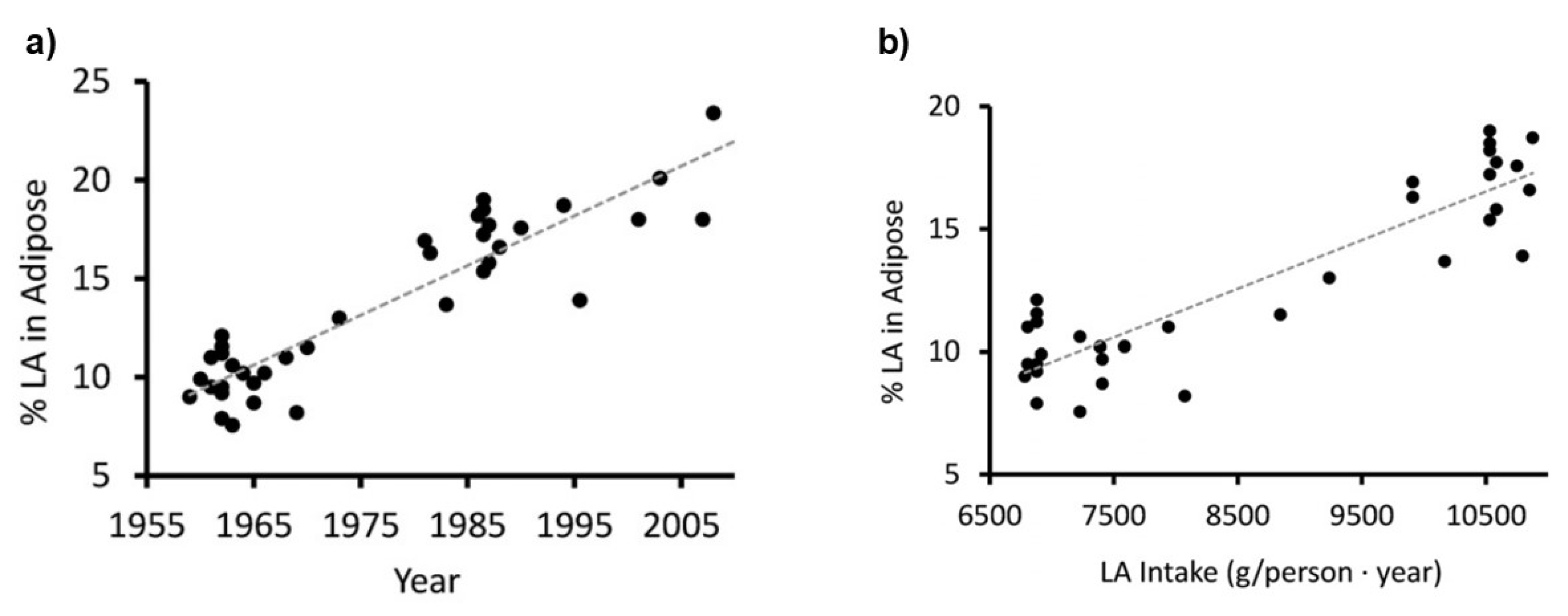

- Blasbalg, TL; Hibbeln, JR; Ramsden, CE; Majchrzak, SF; Rawlings, RR. Changes in consumption of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids in the United States during the 20th century. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011, 93(5), 950–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guyenet, SJ; Carlson, SE. Increase in adipose tissue linoleic acid of US adults in the last half century. Adv Nutr. 2015, 6(6), 660–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaqoob, P; Pala, HS; Cortina-Borja, M; Newsholme, EA; Calder, PC. Encapsulated fish oil enriched in alpha-tocopherol alters plasma phospholipid and mononuclear cell fatty acid compositions but not mononuclear cell functions. Eur J Clin Invest. 2000, 30(3), 260–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B; Wu, L; Chen, J; Dong, L; Chen, C; Wen, Z; et al. Metabolism pathways of arachidonic acids: mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021, 6(1), 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leaf, A. Omega-3 fatty acids and prevention of ventricular fibrillation. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 1995, 52(2-3), 197–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, CM; Cedars, A; Gross, RW. Eicosanoid signalling pathways in the heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2009, 82(2), 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Incontro, S; Musella, ML; Sammari, M; Di Scala, C; Fantini, J; Debanne, D. Lipids shape brain function through ion channel and receptor modulations: physiological mechanisms and clinical perspectives. Physiol Rev. 2025, 105(1), 137–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naganuma, T; Fujinami, N; Arita, M. Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid-Derived Lipid Mediators That Regulate Epithelial Homeostasis. Biol Pharm Bull. 2022, 45(8), 998–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durkin, LA; Childs, CE; Calder, PC. Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and the Intestinal Epithelium-A Review. Foods 2021, 10(1), 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biernacki, M; Skrzydlewska, E. Metabolic pathways of eicosanoids-derivatives of arachidonic acid and their significance in skin. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2025, 30(1), 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodur, M; Yilmaz, B; Ağagündüz, D; Ozogul, Y. Immunomodulatory Effects of Omega-3 Fatty Acids: Mechanistic Insights and Health Implications. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2025, 69(10), e202400752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanger, L; Holinstat, M. Bioactive lipid regulation of platelet function, hemostasis, and thrombosis. Pharmacol Ther. 2023, 246, 108420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Y; Taylor, CG; Aukema, HM; Zahradka, P. Role of oxylipins generated from dietary PUFAs in the modulation of endothelial cell function. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 2020, 160, 102160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, EJ; Yusof, MH; Yaqoob, P; Miles, EA; Calder, PC. Omega-3 fatty acids and leukocyte-endothelium adhesion: Novel anti-atherosclerotic actions. Mol Aspects Med. 2018, 64, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, PB; Yang, JS; Park, Y. Adaptations of Skeletal Muscle Mitochondria to Obesity, Exercise, and Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids. Lipids 2018, 53(3), 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broome, SC; Whitfield, J; Karagounis, LG; Hawley, JA. Mitochondria as Nutritional Targets to Maintain Muscle Health and Physical Function During Ageing. Sports Med. 2024, 54(9), 2291–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulkin, M; Pimpin, L; Bellinger, D; Kranz, S; Fawzi, W; Duggan, C; et al. n-3 Fatty Acid Supplementation in Mothers, Preterm Infants, and Term Infants and Childhood Psychomotor and Visual Development: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Nutr. 2018, 148(3), 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauritzen, L; Brambilla, P; Mazzocchi, A; Harsløf, LB; Ciappolino, V; Agostoni, C. DHA Effects in Brain Development and Function. Nutrients 2016, 8(1), 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campoy, C; Escolano-Margarit, MV; Anjos, T; Szajewska, H; Uauy, R. Omega 3 fatty acids on child growth, visual acuity and neurodevelopment. Br J Nutr. 2012, 107 Suppl 2, S85–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, AJ. Docosahexaenoic acid and the brain- what is its role? Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2019, 28(4), 675–688. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini, B; Nourmohamadi, M; Hajipour, S; Taghizadeh, M; Asemi, Z; Keshavarz, SA; et al. The Effect of Omega-3 Fatty Acids, EPA, and/or DHA on Male Infertility: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Diet Suppl. 2019, 16(2), 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esmaeili, V; Shahverdi, AH; Moghadasian, MH; Alizadeh, AR. Dietary fatty acids affect semen quality: a review. Andrology 2015, 3(3), 450–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M; Liu, D; Wang, L. Role of oxylipins in ovarian function and disease: A comprehensive review. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024, 178, 117242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firouzabadi, FD; Shab-Bidar, S; Jayedi, A. The effects of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids supplementation in pregnancy, lactation, and infancy: An umbrella review of meta-analyses of randomized trials. Pharmacol Res. 2022, 177, 106100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, EJ; Calder, PC; Kermack, AJ; Brown, JE; Mustapha, M; Kitson-Reynolds, E; et al. Omega-3 LC-PUFA consumption is now recommended for women of childbearing age and during pregnancy to protect against preterm and early preterm birth: implementing this recommendation in a sustainable manner. Front Nutr. 2024, 11, 1502866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myatt, L; Lye, SJ. Expression, localization and function of prostaglandin receptors in myometrium. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 2004, 70(2), 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibb, W. The role of prostaglandins in human parturition. Ann Med. 1998, 30(3), 235–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molloy, C; Doyle, LW; Makrides, M; Anderson, PJ. Docosahexaenoic acid and visual functioning in preterm infants: a review. Neuropsychol Rev. 2012, 22(4), 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J; Zhang, Y; Zhao, X. The Effects and Mechanisms of n-3 and n-6 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in the Central Nervous System. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2025, 45(1), 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leow, JWH; Chan, ECY. CYP2J2-mediated metabolism of arachidonic acid in heart: A review of its kinetics, inhibition and role in heart rhythm control. Pharmacol Ther. 2024, 258, 108637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drenjančević, I; Pitha, J. Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids-Vascular and Cardiac Effects on the Cellular and Molecular Level (Narrative Review). Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23(4), 2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodson, L; Rosqvist, F; Parry, SA. The influence of dietary fatty acids on liver fat content and metabolism. Proc Nutr Soc. 2020, 79(1), 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merheb, C; Gerbal-Chaloin, S; Casas, F; Diab-Assaf, M; Daujat-Chavanieu, M; Feillet-Coudray, C. Omega-3 Fatty Acids, Furan Fatty Acids, and Hydroxy Fatty Acid Esters: Dietary Bioactive Lipids with Potential Benefits for MAFLD and Liver Health. Nutrients 2025, 17(6), 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, CM; Breyer, MD. Physiologic and pathophysiologic roles of lipid mediators in the kidney. Kidney Int. 2007, 71(11), 1105–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, UN; Hacimüftüoglu, A; Akpinar, E; Gul, M; Abd El-Aty, AM. Crosstalk between renin and arachidonic acid (and its metabolites). Lipids Health Dis. 2025, 24(1), 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGlory, C; Calder, PC; Nunes, EA. The Influence of Omega-3 Fatty Acids on Skeletal Muscle Protein Turnover in Health, Disuse, and Disease. Front Nutr. 2019, 6, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaauw, R; Calder, PC; Martindale, RG; Berger, MM. Combining proteins with n-3 PUFAs (EPA + DHA) and their inflammation pro-resolution mediators for preservation of skeletal muscle mass. Crit Care 2024, 28(1), 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, T; Mandal, CC. Omega-3 fatty acids in pathological calcification and bone health. J Food Biochem. 2020, 44(8), e13333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Z; Al-Ghouti, MA; Abou-Saleh, H; Rahman, MM. Unraveling the Omega-3 Puzzle: Navigating Challenges and Innovations for Bone Health and Healthy Aging. Mar Drugs 2024, 22(10), 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golanski, J; Szymanska, P; Rozalski, M. Effects of Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and Their Metabolites on Haemostasis-Current Perspectives in Cardiovascular Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22(5), 2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabi, SM; Bahari, H; Chambari, M; Bahrami, LS; Mohaildeen Gubari, MI; Watts, GF; et al. Omega-3 fatty acids and endothelial function: A GRADE-assessed systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Invest. 2024, 54(2), e14109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz Del Campo, LS; Rodrigues-Díez, R; Salaices, M; Briones, AM; García-Redondo, AB. Specialized Pro-Resolving Lipid Mediators: New Therapeutic Approaches for Vascular Remodeling. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23(7), 3592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serini, S; Calviello, G. New Insights on the Effects of Dietary Omega-3 Fatty Acids on Impaired Skin Healing in Diabetes and Chronic Venous Leg Ulcers. Foods 2021, 10(10), 2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasukawa, K; Okuno, T; Yokomizo, T. Eicosanoids in Skin Wound Healing. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21(22), 8435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srnic, N; Westcott, F; Caney, E; Hodson, L. Dietary fat quantity and composition influence hepatic lipid metabolism and metabolic disease risk in humans. Dis Model Mech. 2025, 18(1), dmm050878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsden, CE; Ringel, A; Feldstein, AE; Taha, AY; MacIntosh, BA; Hibbeln, JR; et al. Lowering dietary linoleic acid reduces bioactive oxidized linoleic acid metabolites in humans. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 2012, 87(4-5), 135–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, N; Sawada, K; Takahashi, I; Matsuda, M; Fukui, S; Tokuyasu, H; et al. Association between Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid and Reactive Oxygen Species Production of Neutrophils in the General Population. Nutrients 2020, 12(11), 3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, N; Caprio, S; Giannini, C; Kim, G; Kursawe, R; Pierpont, B; et al. Oxidized fatty acids: A potential pathogenic link between fatty liver and type 2 diabetes in obese adolescents? Antioxid Redox Signal 2014, 20(2), 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzino, G; Irrera, N; Cucinotta, M; Pallio, G; Mannino, F; Arcoraci, V; et al. Oxidative Stress: Harms and Benefits for Human Health. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017, 2017, 8416763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simopoulos, AP. The importance of the ratio of omega-6/omega-3 essential fatty acids. Biomed Pharmacother 2002, 56(8), 365–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simopoulos, AP. An Increase in the Omega-6/Omega-3 Fatty Acid Ratio Increases the Risk for Obesity. Nutrients 2016, 8(3), 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

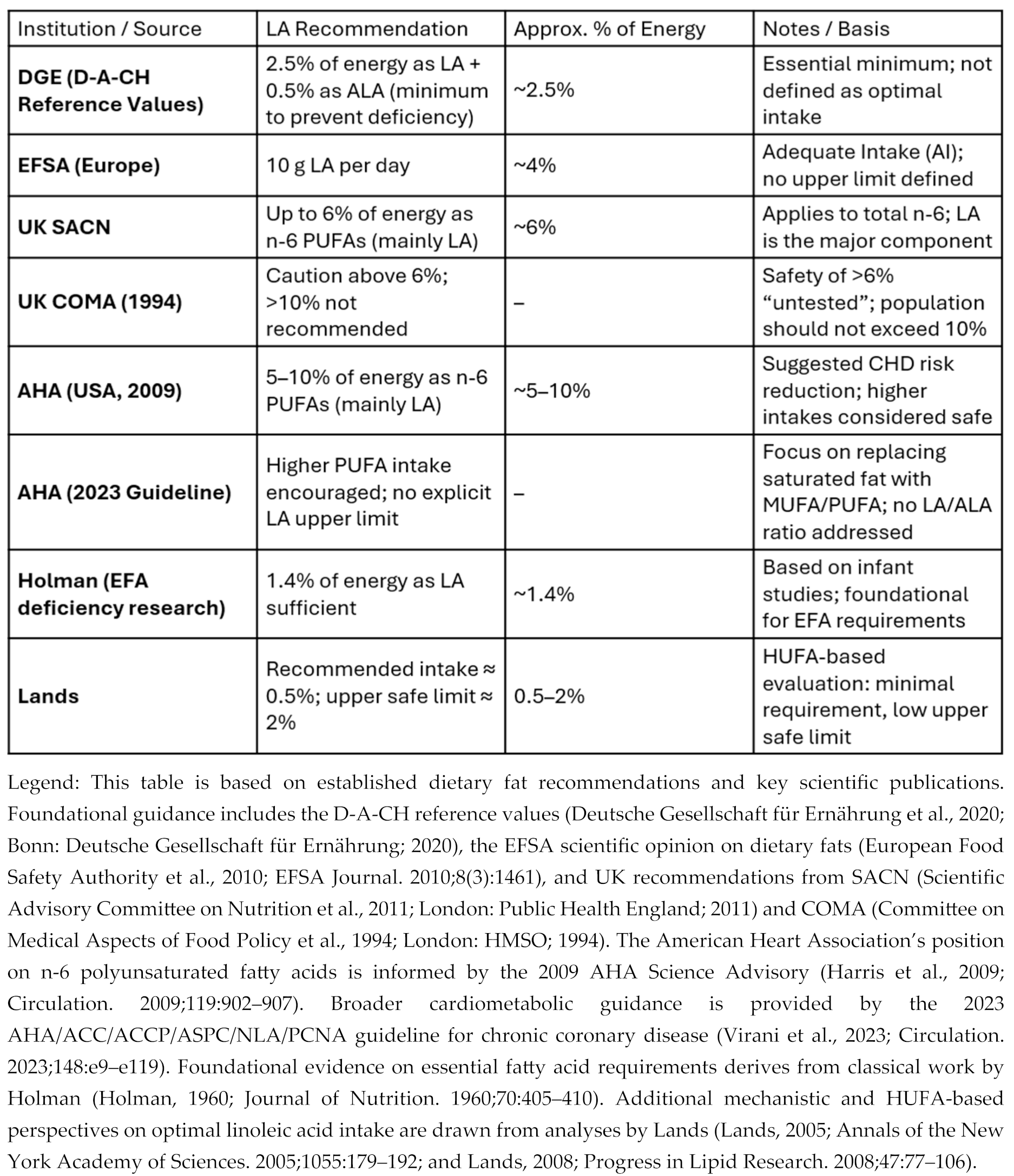

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Ernährung (DGE). Referenzwerte für die Nährstoffzufuhr: Linolsäure und α-Linolensäure; DGE: Bonn, 2020; Available online: https://www.dge.de/wissenschaft/referenzwerte/linolsaeure-und-alpha-linolensaure/ (accessed on 3 Jan 2026).

- Mariamenatu, AH; Abdu, EM. Overconsumption of Omega-6 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (PUFAs) versus Deficiency of Omega-3 PUFAs in Modern-Day Diets: The Disturbing Factor for Their "Balanced Antagonistic Metabolic Functions" in the Human Body. J Lipids 2021, 2021, 8848161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aranceta, J; Pérez-Rodrigo, C. Recommended dietary reference intakes, nutritional goals and dietary guidelines for fat and fatty acids: a systematic review. Br J Nutr. 2012, 107 Suppl 2, S8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jandacek, RJ. Linoleic Acid: A Nutritional Quandary. Healthcare (Basel) 2017, 5(2), 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, LH; Dunn, GD; Brennan, MF. Essential fatty acid deficiency during total parenteral nutrition. Ann Surg. 1981, 193(3), 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, RT; Caster, WO; Wiese, HF. The essential fatty acid requirement of infants and the assessment of their dietary intake of linoleate by serum fatty acid analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 1964, 14, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, WS; Mozaffarian, D; Rimm, E; Kris-Etherton, P; Rudel, LL; Appel, LJ; et al. Omega-6 fatty acids and risk for cardiovascular disease: a science advisory from the American Heart Association Nutrition Subcommittee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; and Council on Epidemiology and Prevention. Circulation 2009, 119(6), 902–907. [Google Scholar]

- Czernichow, S; Thomas, D; Bruckert, E. n-6 Fatty acids and cardiovascular health: a review of the evidence for dietary intake recommendations. Br J Nutr. 2010, 104(6), 788–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, PC. The American Heart Association advisory on n-6 fatty acids: evidence based or biased evidence? Br J Nutr. 2010, 104(11), 1575–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsden, CE; Hibbeln, JR; Majchrzak, SF; Davis, JM. n-6 fatty acid-specific and mixed polyunsaturate dietary interventions have different effects on CHD risk: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Nutr. 2010, 104(11), 1586–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virani, SS; Newby, LK; Arnold, SV; Bittner, V; Brewer, LC; Demeter, SH; et al. 2023 AHA/ACC/ACCP/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline for the Management of Patients With Chronic Coronary Disease: A Report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2023, 148(9), e9–e119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products; Nutrition; and Allergies (NDA). Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for fats, including saturated fatty acids, polyunsaturated fatty acids, monounsaturated fatty acids, trans fatty acids, and cholesterol. European Food Safety Authority. EFSA Journal 2010, 8(3), 1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Report of the Panel on DRVs of the Committee on Medical Aspects of Food Policy (COMA) of the Department of Health, Dietary reference values (DRVs) for Food Energy and Nutrients for the UK. Report on Health and Social Subjects no. 41. London: The Stationery Office, 1991. Dietary_Reference_Values_for_Food_Energy_and_Nutrients_for_the_United_Kingdom_1991_.pdf.

- Report of the Cardiovascular Review Group of the Committee on Medical Aspects of Food Policy (COMA) of the Department of Health, Nutritional Aspects of Cardiovascular Disease. Report on Health and Social Subjects no. 46. London: The Stationery Office, 1994. Nutritional_Aspects_of_Cardiovascular_Disease__1994_.pdf.

- Lands, W.E.M. Fish, Omega-3 and Human Health, Second Edition; Imprint AOCS Publishing: New York, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newport, MT; Dayrit, FM. The Lipid-Heart Hypothesis and the Keys Equation Defined the Dietary Guidelines but Ignored the Impact of Trans-Fat and High Linoleic Acid Consumption. Nutrients 2024, 16(10), 1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holman, RT. The slow discovery of the importance of omega 3 essential fatty acids in human health. J Nutr. 1998, 128(2 Suppl), 427S–433S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, MT; Nara, TY. Essential fatty acid synthesis and its regulation in mammals. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 2003, 68(2), 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitson, AP; Stroud, CK; Stark, KD. Elevated production of docosahexaenoic acid in females: potential molecular mechanisms. Lipids 2010, 45(3), 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, AY; Cheon, Y; Faurot, KF; Macintosh, B; Majchrzak-Hong, SF; Mann, JD; et al. Dietary omega-6 fatty acid lowering increases bioavailability of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in human plasma lipid pools. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 2014, 90(5), 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harnack, K; Andersen, G; Somoza, V. Quantitation of alpha-linolenic acid elongation to eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acid as affected by the ratio of n6/n3 fatty acids. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2009, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibbeln, JR; Nieminen, LR; Blasbalg, TL; Riggs, JA; Lands, WE. Healthy intakes of n-3 and n-6 fatty acids: estimations considering worldwide diversity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006, 83(6 Suppl), 1483S–1493S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, KE; Lau, A; Mantzioris, E; Gibson, RA; Ramsden, CE; Muhlhausler, BS. A low omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid (n-6 PUFA) diet increases omega-3 (n-3) long chain PUFA status in plasma phospholipids in humans. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 2014, 90(4), 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maki, KC; Eren, F; Cassens, ME; Dicklin, MR; Davidson, MH. ω-6 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and Cardiometabolic Health: Current Evidence, Controversies, and Research Gaps. Adv Nutr. 2018, 9(6), 688–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, JHY; Marklund, M; Imamura, F; Tintle, N; Ardisson Korat, AV; de Goede, J; et al. Omega-6 fatty acid biomarkers and incident type 2 diabetes: pooled analysis of individual-level data for 39 740 adults from 20 prospective cohort studies. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017, 5(12), 965–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjermo, H; Iggman, D; Kullberg, J; Dahlman, I; Johansson, L; Persson, L; et al. Effects of n-6 PUFAs compared with SFAs on liver fat, lipoproteins, and inflammation in abdominal obesity: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012, 95(5), 1003–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, J; Li, L; Ren, L; Sun, J; Zhao, H; Sun, Y. Dietary n-3 and n-6 fatty acid intakes and NAFLD: A cross-sectional study in the United States. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2021, 30(1), 87–98. [Google Scholar]

- Mocciaro, G; Allison, M; Jenkins, B; Azzu, V; Huang-Doran, I; Herrera-Marcos, LV; et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is characterised by a reduced polyunsaturated fatty acid transport via free fatty acids and high-density lipoproteins (HDL). Mol Metab. 2023, 73, 101728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, A; Sun, Z; Zhang, M; Li, J; Pan, X; Chen, P. Associations between dietary fatty acid patterns and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in typical dietary population: A UK biobank study. Front Nutr. 2023, 10, 1117626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaegashi, A; Kimura, T; Wakai, K; Iso, H; Tamakoshi, A. Associations of Total Fat and Fatty Acid Intake With the Risk of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Among Japanese Adults: Analysis Based on the JACC Study. J Epidemiol. 2024, 34(7), 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfhili, MA; Alsughayyir, J; Basudan, A; Alfaifi, M; Awan, ZA; Algethami, MR; et al. Blood indices of omega-3 and omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids are altered in hyperglycemia. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2023, 30(3), 103577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, JC; Elsom, RL; Calder, PC; Griffin, BA; Harris, WS; Jebb, SA; et al. UK Food Standards Agency Workshop Report: the effects of the dietary n-6:n-3 fatty acid ratio on cardiovascular health. Br J Nutr. 2007, 98(6), 1305–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, WS. The omega-6/omega-3 ratio and cardiovascular disease risk: uses and abuses. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2006, 8(6), 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poli, A; Agostoni, C; Visioli, F. Dietary Fatty Acids and Inflammation: Focus on the n-6 Series. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24(5), 4567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsden, CE; Zamora, D; Leelarthaepin, B; Majchrzak-Hong, SF; Faurot, KR; Suchindran, CM; et al. Use of dietary linoleic acid for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease and death: evaluation of recovered data from the Sydney Diet Heart Study and updated meta-analysis. BMJ 2013, 346, e8707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsden, CE; Zamora, D; Majchrzak-Hong, S; Faurot, KR; Broste, SK; Frantz, RP; et al. Re-evaluation of the traditional diet-heart hypothesis: analysis of recovered data from Minnesota Coronary Experiment (1968-73). BMJ Erratum in: BMJ. 2024 Jun 28;385:q1450. 2016, 353, i1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y; Sun, Y; Yu, Q; Song, S; Brenna, JT; Shen, Y; et al. Higher ratio of plasma omega-6/omega-3 fatty acids is associated with greater risk of all-cause, cancer, and cardiovascular mortality: A population-based cohort study in UK Biobank. Elife 2024, 12, RP90132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, GH; Fritsche, K. Effect of dietary linoleic acid on markers of inflammation in healthy persons: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Acad Nutr Diet 2012, 112(7), 1029-41, 1041.e1-15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galli, C; Agradi, E; Petroni, A; Tremoli, E. Differential effects of dietary fatty acids on the accumulation of arachidonic acid and its metabolic conversion through the cyclooxygenase and lipoxygenase in platelets and vascular tissue. Lipids 1981, 16(3), 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Hypothesis |

| 1 | The dietary mixture of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) determines cellular fatty-acid profiles and thereby shapes the non-energetic biological actions of these lipids. |

| 2 | n-6 and n-3 highly unsaturated fatty acids (HUFAs) influence each other metabolically, differ in their biochemical efficacy, and give rise to distinct organ- and system-level functions. |

| 3 | The competition of n-6 and n-3 HUFAs for shared metabolic enzymes (COX, LOX, CYP) is the primary determinant of downstream lipid mediator profiles. |

| 4 | The quantitative relationship between dietary PUFA intake and HUFA composition is predictable and can be modelled with high accuracy, enabling mechanistic forecasting of biological outcomes. |

| 5 | The long-standing neglect of dietary PUFA imbalance may contribute to the continued rise of non-communicable diseases. |

| 6 | Dietary interventions can lower the percentage of n-6 in HUFA, with potential health benefits and associated reductions in healthcare costs. |

| 7 | The individual n-6 HUFA profile serves as a valuable surrogate biomarker because it reflects both dietary inputs and pathophysiological outcomes. |

| 8 | Combining reduced n-6 with increased n-3 PUFA intake most effectively lowers the percentage of n-6 in HUFA, owing to the predictable quantitative dynamics of the competing HUFA families. |

| 9 | Failure to account for the population-wide oversupply of n-6 PUFAs may help explain inconsistent results in randomized controlled trials evaluating the clinical efficacy of n-3 PUFAs. |

| 10 | Measures of basal as well as final n-6 and n-3 HUFA status should be considered important and valid biomarkers for designing and monitoring effective nutritional strategies. |

| 11 | A range of non-communicable diseases appears to be associated with elevated n-6 HUFA levels, and the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms are increasingly understood. |

| 12 | In cardiovascular disease, preliminary evidence already suggests a potential causal role for an increased n-6 HUFA profile. |

| 13 | Achieving an n-6 HUFA percentage near 50% may help reduce annual healthcare expenditures and improve the cost-effectiveness of public-health interventions. |

| No. | Concept |

| 1 | The n-6/n-3 HUFA balance governs inflammatory, immunologic, and metabolic signaling |

| 2 | Excessive n-6 PUFA and HUFA abundance drives molecular, cellular, and organ-level pathomechanisms linked to chronic disease |

| 3 | Increasing linoleic acid intake may amplify HUFA-mediated pathomechanisms in n-6–dominant physiological states |

| 4 | The concept of a dietary toxicity threshold for linoleic acid appears to be supported by available evidence, yet remains debated |

| 5 | The availability of n-3 PUFAs in individuals consuming the “Western diet” high in n-6 PUFAs is steadily declining. |

| 6 | The appropriate dietary n-3 HUFA uptake depends on the individual cellular n-6 HUFA availability. |

| System | Examples |

| Molecular: Cell signalling, gene expression and protein production Ion channels and membrane transporters |

Probably all cell types [6,95] Many cell types including cardiomyocytes [96,97] and neurones [98] |

| Cellular: Activation, proliferation and responsiveness Mitochondrial biogenesis and function |

Probably all cell types, including intestinal epithelial cells [99,100], skin cells [99,101], immune and inflammatory cells [69,102], platelets [6,103] and endothelial cells [104,105] Probably all cell types [106,107] |

| Organ development: | Probably all organs, but especially eye and brain [108,109,110,111] |

| Organ function and (life-stage) physiology: Fertility (both male and female) Pregnancy Parturition Vision Brain function/cognition Cardiac function Liver function Renal function Skeletal muscle function Bone homeostasis Inflammation Immune defence Haemostasis Vasoconstriction/vasodilation/blood flow/blood pressure Wound healing Lipid metabolism (synthesis, oxidation, deposition, mobilisation) |

[112,113,114] [115,116] [117,118] [119] [110,111,120] [121,122] [123,124] [125,126] [127,128] [129,130] [65,69] [102] [6,103,131] [132,133] [134,135] [81,136] |

| Impact of excessive high abundance of n-6 PUFAs and HUFAs | Expected morbidity* |

| Low n-3 HUFA availability in early life | Poorer visual development |

| Low n-3 HUFA availability in early life | Poorer cognitive development (-> childhood learning and behavioural disorders) |

| Low n-3 HUFA availability and excessive pro-parturition n-6 HUFA-derived oxylipins during pregnancy | Pre-term birth |

| Low n-3 HUFA availability during pregnancy and excessive n-6 HUFA-derived oxylipins | Gestational diabetes |

| Low n-3 HUFA availability during pregnancy and excessive n-6 HUFA-derived oxylipins | Post-natal depression |

| Low n-3 HUFA availability and excessive pro-proliferative, anti-apoptotic n-6 HUFA-derived oxylipins | Many cancers |

| Low n-3 HUFA availability and excessive pro-inflammatory n-6 HUFA-derived oxylipins | High-grade inflammatory conditions (rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel diseases, inflammatory skin diseases) |

| Low n-3 HUFA availability and excessive pro-inflammatory n-6 HUFA-derived oxylipins | Migraine, pain |

| Low n-3 HUFA availability and excessive pro-allergic n-6 HUFA-derived oxylipins | Allergy, asthma |

| Low n-3 HUFA availability and excessive pro-inflammatory n-6 HUFA-derived oxylipins | Low-grade inflammatory conditions (cardiovascular diseases (e.g. coronary heart disease, peripheral vascular disease, stroke), metabolic diseases (e.g. type-2 diabetes, fatty liver disease, more severe fatty liver disease), kidney disease, cognitive decline, loss of lean mass (muscle and bone) -> sarcopenia) |

| Low n-3 HUFA availability and excessive pro-inflammatory n-6 HUFA-derived oxylipins | Psychological and psychiatric diseases |

| Low n-3 HUFA availability and excessive pro-inflammatory n-6 HUFA-derived | Poor wound healing |

| Low n-3 HUFA availability and excessive pro-inflammatory n-6 HUFA-derived oxylipins | Critical illness following a severe physical insult |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).