Submitted:

08 January 2026

Posted:

09 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Clinical Records

3.1. Blood Chemistry Values

3.2. Surgical Details

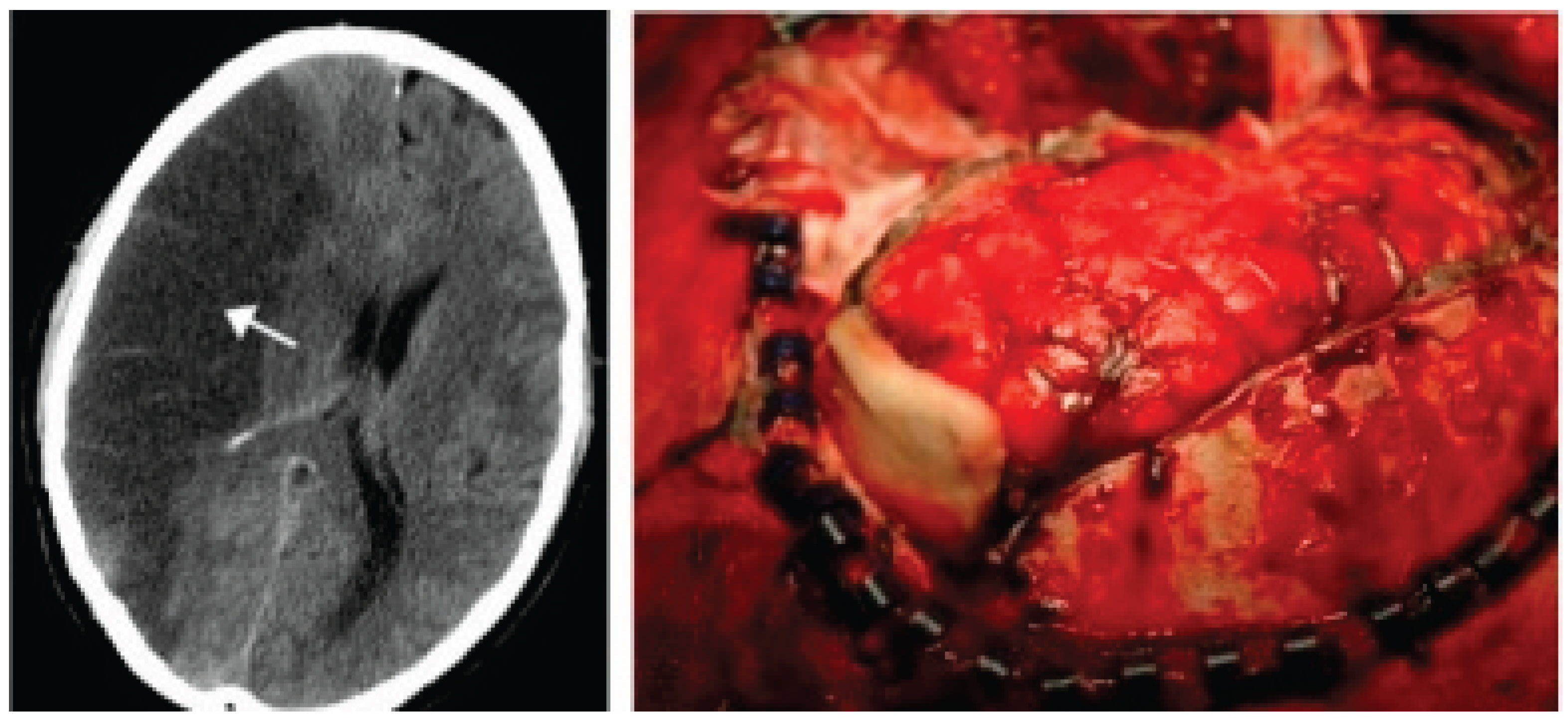

3.3. Neuroradiological Imaging

4. Statistical Analysis

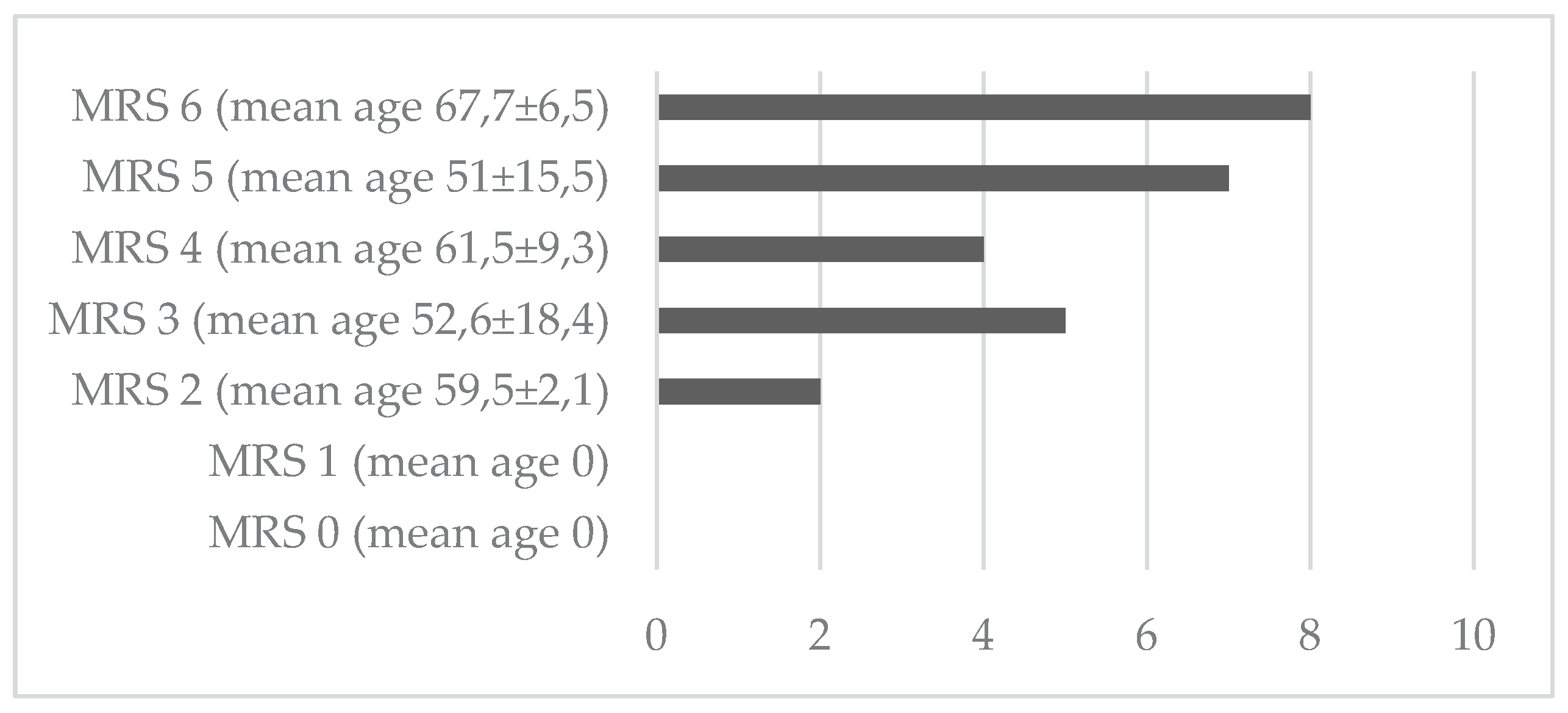

5. Results

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

References

- Lammy, S; Al-Romhain, B; Osborne, L; St George, EJ. 10-Year Institutional Retrospective Case Series of Decompressive Craniectomy for Malignant Middle Cerebral Artery Stroke (mMCAI). World Neurosurg;Epub 2016, 96, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J; Su, YY; Zhang, Y; Zhang, YZ; Zhao, R; Wang, L; Gao, R; Chen, W; Gao, D. Decompressive hemicraniectomy in malignant middle cerebral artery infarct: a randomized controlled trial enrolling patients up to 80 years old. Neurocrit Care 2012, 17(2), 161–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vahedi, K; Hofmeijer, J; Juettler, E; Vicaut, E; George, B; Algra, A; Amelink, GJ; Schmiedeck, P; Schwab, S; Rothwell, PM; Bousser, MG; van der Worp, HB; Hacke, W. DECIMAL, DESTINY, and HAMLET investigators. Early decompressive surgery in malignant stroke of the middle cerebral artery: a pooled analysis of three randomised controlled trials. Lancet Neurol 2007, 6(3), 215–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moughal, S; Trippier, S; Al-Mousa, A; Hainsworth, AH; Pereira, AC; Minhas, PS; Shtaya, A. Strokectomy for malignant middle cerebral artery stroke: experience and meta-analysis of current evidence. J Neurol 2022, 269(1), 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tartara, F; Colombo, EV; Bongetta, D; Pilloni, G; Bortolotti, C; Boeris, D; Zenga, F; Giossi, A; Ciccone, A; Sessa, M; Cenzato, M. Strokectomy and Extensive Cisternal CSF Drain for Acute Management of Malignant Middle Cerebral Artery Stroke: Technical Note and Case Series. Front Neurol 2019, 10, 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Heiss, WD; Rosner, G. Functional recovery of cortical neurons as related to degree and duration of ischemia. Ann Neurol 1983, 14(3), 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, Z; Chang, X; Zhou, H; Lin, S; Liu, M. A Cohort Study of Decompressive Craniectomy for Malignant Middle Cerebral Artery Stroke: A Real-World Experience in Clinical Practice. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015, 94(25), e1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wu, J; Wei, W; Gao, YH; Liang, FT; Gao, YL; Yu, HG; Huang, QL; Long, XQ; Zhou, YF. Surgical Decompression versus Conservative Treatment in Patients with Malignant Stroke of the Middle Cerebral Artery: Direct Comparison of Death-Related Complications. World Neurosurg 2020, 135, e366–e374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, TK; Chen, SM; Huang, YC; Chen, PY; Chen, MC; Tsai, HC; Lee, TH; Chen, KT; Lee, MH; Yang, JT; Huang, KL. The Outcome Predictors of Malignant Large Stroke and the Functional Outcome of Survivors Following Decompressive Craniectomy. World Neurosurg;Epub 2016, 93, 133–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Y; Liu, W; Yang, X; Hu, W; Li, G. Is decompressive craniectomy for malignant middle cerebral artery territory stroke of any benefit for elderly patients? Surg Neurol 2005, 64(2), 165–9; discussion 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harscher, S; Reichart, R; Terborg, C; Hagemann, G; Kalff, R; Witte, OW. Outcome after decompressive craniectomy in patients with severe ischemic stroke. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2006, 148(1), 31–7; discussion 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rai, VK; Bhatia, R; Prasad, K; Padma Srivastava, MV; Singh, S; Rai, N; Suri, A. Long-term outcome of decompressive hemicraniectomy in patients with malignant middle cerebral artery stroke: a prospective observational study. Neurol India 2014, 62(1), 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dasenbrock, HH; Robertson, FC; Vaitkevicius, H; Aziz-Sultan, MA; Guttieres, D; Dunn, IF; Du, R; Gormley, WB. Timing of Decompressive Hemicraniectomy for Stroke: A Nationwide Inpatient Sample Analysis. Stroke;Epub 2017, 48(3), 704–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsawaf, A; Galhom, A. Decompressive Craniotomy for Malignant Middle Cerebral Artery Stroke: Optimal Timing and Literature Review. World Neurosurg 2018, 116, e71–e78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, K; Nakao, Y; Yamamoto, T; Maeda, M. Early external decompressive craniectomy with duroplasty improves functional recovery in patients with massive hemispheric embolic stroke: timing and indication of decompressive surgery for malignant cerebral stroke. Surg Neurol 2004, 62(5), 420-9; discussion 429-30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwab, S; Steiner, T; Aschoff, A; Schwarz, S; Steiner, HH; Jansen, O; Hacke, W. Early hemicraniectomy in patients with complete middle cerebral artery stroke. Stroke 1998, 29(9), 1888–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, KW; Chang, WN; Ho, JT; Chang, HW; Lui, CC; Cheng, MH; Hung, KS; Wang, HC; Tsai, NW; Sun, TK; Lu, CH. Factors predictive of fatality in massive middle cerebral artery territory stroke and clinical experience of decompressive hemicraniectomy. Eur J Neurol 2006, 13(7), 765–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmeijer, J; Kappelle, LJ; Algra, A; Amelink, GJ; van Gijn, J; van der Worp, HB; HAMLET investigators. Surgical decompression for space-occupying cerebral stroke (the Hemicraniectomy After Middle Cerebral Artery stroke with Life-threatening Edema Trial [HAMLET]): a multicentre, open, randomised trial. Lancet Neurol 2009, 8(4), 326–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, BR; Yoo, CJ; Kim, MJ; Kim, WK; Choi, DH. Analysis of the Outcome and Prognostic Factors of Decompressive Craniectomy between Young and Elderly Patients for Acute Middle Cerebral Artery Stroke. J Cerebrovasc Endovasc Neurosurg;Epub 2016, 18(3), 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Frank, JI. Large hemispheric stroke, deterioration, and intracranial pressure. Neurology 1995, 45(7), 1286–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwab, S; Aschoff, A; Spranger, M; Albert, F; Hacke, W. The value of intracranial pressure monitoring in acute hemispheric stroke. Neurology 1996, 47(2), 393–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuroki, K; Taguchi, H; Sumida, M; Yukawa, O; Murakami, T; Onda, J; Eguchi, K. Decompressive craniectomy for massive stroke of middle cerebral artery territory; No Shinkei Geka: Japanese, Sep 2001; Volume 29, 9, pp. 831–5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mattos, JP; Joaquim, AF; Almeida, JP; Albuquerque, LA; Silva, EG; Marenco, HA; Oliveira, Ed. Decompressive craniectomy in massive cerebral stroke. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2010, 68(3), 339–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, YP; Hou, MZ; Lu, GY; Ciccone, N; Wang, XD; Dong, L; Cheng, C; Zhang, HZ. Neurologic Functional Outcomes of Decompressive Hemicraniectomy Versus Conventional Treatment for Malignant Middle Cerebral Artery Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World Neurosurg 2017, 99, 709–725.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uhl, E; Kreth, FW; Elias, B; Goldammer, A; Hempelmann, RG; Liefner, M; Nowak, G; Oertel, M; Schmieder, K; Schneider, GH. Outcome and prognostic factors of hemicraniectomy for space occupying cerebral stroke. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2004, 75(2), 270–4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vahedi, K; Vicaut, E; Mateo, J; Kurtz, A; Orabi, M; Guichard, JP; Boutron, C; Couvreur, G; Rouanet, F; Touzé, E; Guillon, B; Carpentier, A; Yelnik, A; George, B; Payen, D; Bousser, MG. DECIMAL Investigators. Sequential-design, multicenter, randomized, controlled trial of early decompressive craniectomy in malignant middle cerebral artery stroke (DECIMAL Trial). Stroke 2007, 38(9), 2506–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jüttler, E; Schwab, S; Schmiedek, P; Unterberg, A; Hennerici, M; Woitzik, J; Witte, S; Jenetzky, E; Hacke, W; DESTINY Study Group. Decompressive Surgery for the Treatment of Malignant Stroke of the Middle Cerebral Artery (DESTINY): a randomized, controlled trial. Stroke 2007, 38(9), 2518–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabinstein, AA; Mueller-Kronast, N; Maramattom, BV; Zazulia, AR; Bamlet, WR; Diringer, MN; Wijdicks, EF. Factors predicting prognosis after decompressive hemicraniectomy for hemispheric stroke. Neurology 2006, 67(5), 891–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maramattom, BV; Bahn, MM; Wijdicks, EF. Which patient fares worse after early deterioration due to swelling from hemispheric stroke? Neurology 2004, 63(11), 2142–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holtkamp, M; Buchheim, K; Unterberg, A; Hoffmann, O; Schielke, E; Weber, JR; Masuhr, F. Hemicraniectomy in elderly patients with space occupying media stroke: improved survival but poor functional outcome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2001, 70(2), 226–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Woertgen, C; Erban, P; Rothoerl, RD; Bein, T; Horn, M; Brawanski, A. Quality of life after decompressive craniectomy in patients suffering from supratentorial brain ischemia. Acta Neurochir (Wien) Epub. 2004, 146(7), 691–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomon, NA; Glick, HA; Russo, CJ; Lee, J; Schulman, KA. Patient preferences for stroke outcomes. Stroke 1994, 25(9), 1721–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walz, B; Zimmermann, C; Böttger, S; Haberl, RL. Prognosis of patients after hemicraniectomy in malignant middle cerebral artery stroke. J Neurol 2002, 249(9), 1183–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerkhoff, G. Spatial hemineglect in humans. Prog Neurobiol 2001, 63(1), 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Göttsche, J; Flottmann, F; Jank, L; Thomalla, G; Rimmele, DL; Czorlich, P; Westphal, M; Regelsberger, J. Decompressive craniectomy in malignant MCA stroke in times of mechanical thrombectomy. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2020, 162(12), 3147–3152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beez, T; Munoz-Bendix, C; Steiger, HJ; Beseoglu, K. Decompressive craniectomy for acute ischemic stroke. Crit Care 2019, 23(1), 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Das, S; Mitchell, P; Ross, N; Whitfield, PC. Decompressive Hemicraniectomy in the Treatment of Malignant Middle Cerebral Artery Stroke: A Meta-Analysis. World Neurosurg 2019, 123, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohan Rajwani, K; Crocker, M; Moynihan, B. Decompressive craniectomy for the treatment of malignant middle cerebral artery stroke. Br J Neurosurg 2017, 31(4), 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daou, B; Kent, AP; Montano, M; Chalouhi, N; Starke, RM; Tjoumakaris, S; Rosenwasser, RH; Jabbour, P. Decompressive hemicraniectomy: predictors of functional outcome in patients with ischemic stroke. J Neurosurg 2016, 124(6), 1773–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatima, N; Razzaq, S; El Beltagi, A; Shuaib, A; Saqqur, M. Decompressive Craniectomy: A Preliminary Study of Comparative Radiographic Characteristics Predicting Outcome in Malignant Ischemic Stroke. World Neurosurg;Epub 2020, 133, e267–e274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pallesen, LP; Barlinn, K; Puetz, V. Role of Decompressive Craniectomy in Ischemic Stroke. Front Neurol 2019, 9, 1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schwab, S; Aschoff, A; Spranger, M; Albert, F; Hacke, W. The value of intracranial pressure monitoring in acute hemispheric stroke. Neurology 1996, 47(2), 393–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poca, MA; Benejam, B; Sahuquillo, J; Riveiro, M; Frascheri, L; Merino, MA; Delgado, P; Alvarez-Sabin, J. Monitoring intracranial pressure in patients with malignant middle cerebral artery infarction: is it useful? J Neurosurg 2010, 112(3), 648–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vahedi, K; Vicaut, E; Mateo, J; Kurtz, A; Orabi, M; Guichard, JP; Boutron, C; Couvreur, G; Rouanet, F; Touzé, E; Guillon, B; Carpentier, A; Yelnik, A; George, B; Payen, D; Bousser, MG. DECIMAL Investigators. Sequential-design, multicenter, randomized, controlled trial of early decompressive craniectomy in malignant middle cerebral artery infarction (DECIMAL Trial). Stroke 2007, 38(9), 2506–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fotakopoulos, G; Gatos, C; Georgakopoulou, VE; Lempesis, IG; Spandidos, DA; Trakas, N; Sklapani, P; Fountas, KN. Role of decompressive craniectomy in the management of acute ischemic stroke (Review). Biomed Rep. 2024, 20(2), 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hofmeijer, J; Kappelle, LJ; Algra, A; Amelink, GJ; van Gijn, J; van der Worp, HB; HAMLET investigators. Surgical decompression for space-occupying cerebral infarction (the Hemicraniectomy After Middle Cerebral Artery infarction with Life-threatening Edema Trial [HAMLET]): a multicentre, open, randomised trial. Lancet Neurol 2009, 8(4), 326–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Bonis, P; Sturiale, CL; Anile, C; Gaudino, S; Mangiola, A; Martucci, M; Colosimo, C; Rigante, L; Pompucci, A. Decompressive craniectomy, interhemispheric hygroma and hydrocephalus: a timeline of events? Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2013, 115(8), 1308–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Patients (n=26) |

|---|---|

| Sex male (n,%) female (n,%) |

16 (59.25) 10 (40.74) |

| Age (years, mean±DS°) | 58.7±13.6 |

| Anamnestic data Precedent cardiovascular event (n,%) Diabetes (n,%) Hypertension (n,%) Dyslipidemia (n,%) Neoplastic pathology (n,%) Hereditary coagulation pathology (n,%) Autoimmune disorders (n,%) Overweight/Obesity (n,%) |

13 (50) 12 (46.1) 18 (69.2) 15 (57.7) 5 (19.2) 7 (26.9) 4 (15.4) 15 (57.7) |

| Preoperative GCS score * < 8 (n,%) 8-12 (n,%) > 12 (n,%) Postoperative complication Syndrome of the trephined (n,%) Systemic infection (n,%) Redo surgery for hemorrhage (n,%) Surgical site infection (n,%) |

23 (88.5) 3 (11.5) 0 (0) 1 (3.8) 15 (57.7) 0 (0) 0 (0) |

| Characteristics | Patients (n=11) |

|---|---|

| Sex Male (n,%) Female (n,%) Revascularization treatments (n,%) Territory of ischemia Right CMA (n,%) Left CMA (n,%) Left CMA and ACA (n,%) |

5 6 6 (23.1) 7 (63.6) 3 (27.3) 1 (9.0) |

| Volume of ischemic alteration (mm3, mean ±DS°) Timing of surgery from admission (n,%) < 48 hours > 48 hours |

412.2±194.6 5 (45.5) 6 (54.5) |

| Characteristics | Pre-operative | Post-operative | p-value (< 0.05) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Midline shift Compression of curtical sulci Obliteration of basal cystern of quadrigeminal cystern of ambiens cystern of Silvian cystern |

20 21 14 22 23 |

17 16 5 13 13 |

0.179 0.045 0.002 0.019 0.020 |

| Variables | Coef. | Std Error | t | P value | IC 95% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Presence of curtical sulci Obliteration of basal cystern of quadrigeminal cystern of ambiens cystern of Silvian cystern |

-0.282 0.560 -1.817 -0.202 |

0.615 0.739 0.786 0.788 |

-0.46 0.76 -2.31 -0.26 |

0.652 0.459 0.034 0.459 |

-1.587/1.021 -1.007/2.128 -3.485/-0.150 -1.007/2.128 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).