1. Introduction

Artificial intelligence is rapidly transforming the informational, economic, and cognitive environments in which human systems operate. Tasks once considered stable and professionalized are increasingly automated, augmented, or restructured, producing steep gradients that require continuous adaptation rather than one-time optimization. Task-based accounts of technological change emphasize that automation reallocates work by reshaping task compositions and skill demands, creating both displacement and continual reinvention pressures across the labor market [

1,

2]. In this emerging landscape, the most practically relevant example of a complex adaptive system interacting with artificial intelligence is not an organization or a market in the abstract, but the coupled human–AI system itself.

Historically, many individuals in professional societies have followed what may be called a

blueprint philosophy: one studies early, qualifies into a profession, stabilizes into an identity, and then exploits that competence over decades. This model presumes a relatively stationary environment in which early optimization confers long-term robustness. However, AI-driven change undermines this stability, particularly in traditionally professionalized domains where specialization and credentialing are strongest. In the blueprint regime, retraining was episodic and optional; in the AI regime, retraining becomes continuous and often unavoidable [

1,

2]. This shift creates a structural vulnerability: systems that cooled early into narrow roles and identities can become brittle when gradients steepen later under irreversible constraints.

A parallel literature in human–automation interaction shows that intelligent assistance fails as often through

relational and

epistemic breakdowns as through technical limitations. Classic results describe misuse, disuse, and abuse of automation as recurrent failure modes when uncertainty and responsibility are poorly calibrated [

3,

4]. Trust is likewise central: appropriate reliance depends on how competence, intent, and uncertainty are communicated [

5,

6]. More recent work emphasizes calibration in modern predictive systems and highlights the risk of both overconfidence and underuse in AI-supported decisions [

7,

8]. These results motivate our focus on

agency as a structural property of the coupled system, not a matter of willpower.

The present work also draws on three mature technical foundations. First, nonequilibrium thermodynamics explains how structured systems arise and persist far from equilibrium while dissipating gradients and producing entropy [

9,

10]. Stochastic thermodynamics extends these ideas to fluctuating systems and provides modern fluctuation relations that sharpen the connection between irreversibility, work, and entropy production [

11,

12,

13]. Second, information theory formalizes uncertainty, rate limits, and channel capacity, establishing hard constraints on reliable information integration [

14,

15]. Landauer’s principle makes the bridge explicit by relating logical irreversibility (e.g., erasure) to minimal thermodynamic dissipation [

16]. Third, stochastic optimization provides constructive methods for escaping local optima in rugged landscapes. Simulated annealing and related Markov chain methods show how controlled noise and cooling schedules can discover globally viable configurations without assuming a known blueprint of the optimum [

17,

18,

19,

20]. Closely related “deterministic annealing” approaches make the same exploration–commitment trade-off explicit as a variational free-energy balance [

21,

22]. At a foundational level, these methods connect directly to Langevin dynamics and diffusion-based sampling [

23,

24] and to Bayesian learning dynamics [

25,

26].

The novelty of this paper lies in making these connections

domain-agnostic and inspectable while extending them to the self and to human–AI coupling. Prior frameworks already share family resemblance with this ambition. In particular, Friston’s Free Energy Principle and active inference formalize adaptive biological systems as minimizing variational free energy (reducing surprise) under generative models [

27,

28]. Interpretive and critical discussions emphasize that the principle is best read as a constrained dynamical account rather than a teleological claim [

29]. Separately, work on “psychological entropy” treats uncertainty and prediction error as central drivers of affect and motivation [

30]. However, these literatures typically do not connect (i) controlled

reheating as a proactive mechanism (ambition as temperature control), (ii) explicit

capacity bounds from Shannon theory as a failure condition for agency, and (iii) practical decision protocols for high-stakes human life choices and professional adaptation under AI.

At the cognitive and behavioral level, evidence supports the relevance of explicit capacity constraints. Cognitive load theory shows that learning and performance degrade when processing demands exceed working-memory and integration limits [

31]. Information overload is a well-studied organizational failure mode [

32,

33], and choice overload can reduce decision quality and motivation even as the option set grows [

34]. These findings align with a central diagnosis of the AI age: AI can increase the effective

option velocity and information rate faster than human systems can reliably integrate, thereby destabilizing agency.

This paper addresses these gaps by proposing a unified annealing-based framework linking thermodynamic entropy, information entropy, and a formally defined self-entropy. Within this framework, ambition is reinterpreted not as goal pursuit but as temperature control: the capacity to sustain stochastic exploration in the absence of immediate external pressure. Premature stabilization—cooling too early in environments of safety or abundance—produces locally coherent but globally brittle configurations. AI steepens gradients and accelerates information flow, making premature cooling increasingly costly in professional societies where the blueprint trajectory has historically been rewarded.

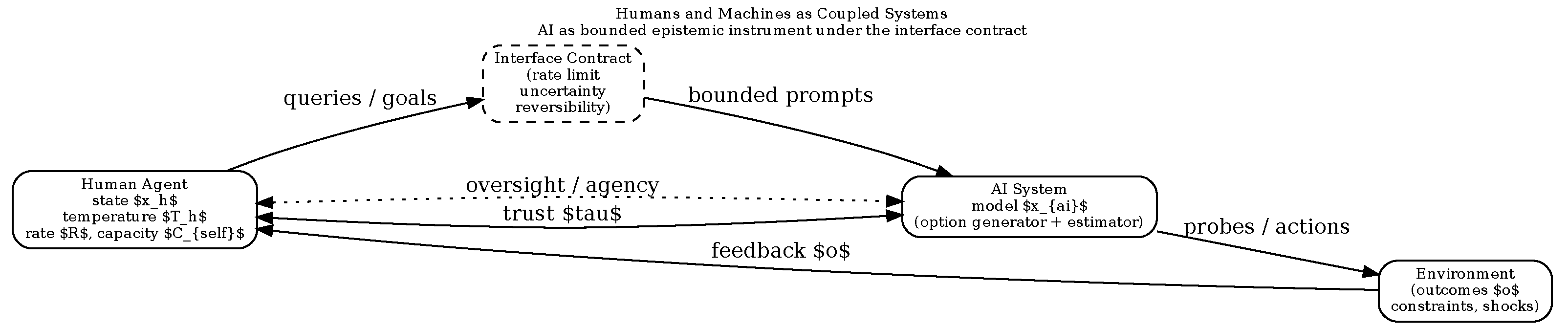

A particularly relevant instance of such complex adaptive systems is the human–AI dyad itself. As AI systems increasingly mediate professional work, learning, and decision-making, they function not merely as tools but as gradient multipliers—accelerating rates of change while leaving human adaptive capacity largely unchanged. Understanding adaptation in this setting therefore requires a framework that treats humans and AI as coupled dynamical systems, rather than as independent optimizers.

The main aim of this work is threefold. First, we formalize a unified stochastic dynamical model that governs adaptation across physical systems, learning systems, and human lives. Second, we apply this model to human–AI systems, explaining why blueprint-based career and identity formation fail under accelerating informational change and task displacement [

1,

2]. Third, we derive practical implications for decision-making, education, and lifelong learning, emphasizing that capacity and exploration tolerance must be trained early—before external AI gradients force abrupt reheating that exceeds integration limits.

Existing approaches to human–AI adaptation emphasize static optimization, equilibrium notions of rationality, or the minimization of surprise and error. While effective in slowly varying environments, these models implicitly assume that identity, skill sets, and goals can stabilize before external conditions shift. We advance the alternative hypothesis that adaptation under accelerating AI-driven change is fundamentally annealing-limited: failure arises not from suboptimal goals, but from premature entropy collapse and rate–capacity mismatch.

The principal conclusion is that adaptation in the AI age cannot be achieved by optimizing static targets such as happiness, certainty, or professional success. Instead, viable human–AI systems must optimize for the continuity of agency: the maintained ability to explore, commit, and reconfigure in response to changing gradients. Entropy-aware annealing is not merely a metaphor for this process; it is its governing structure.

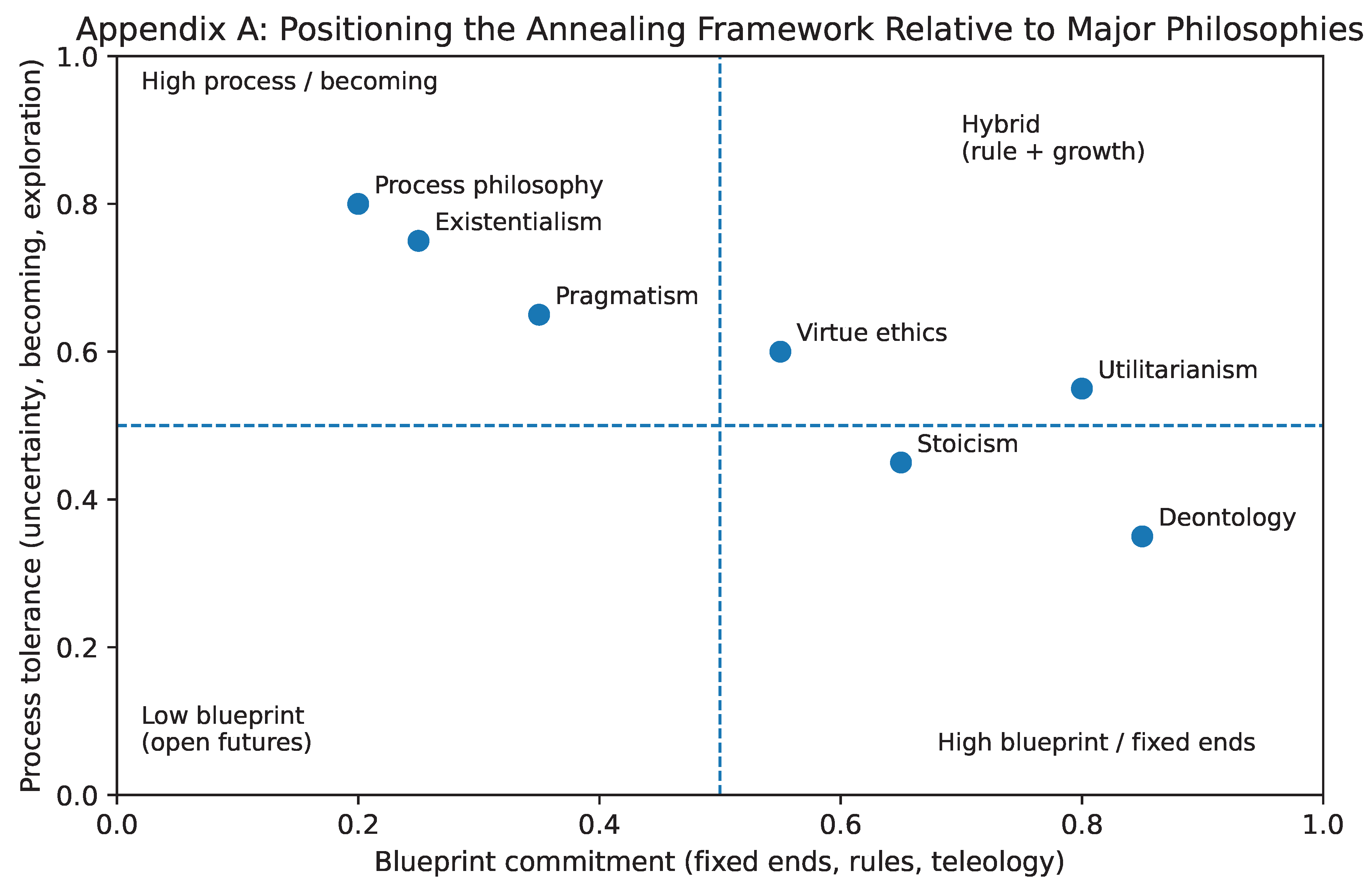

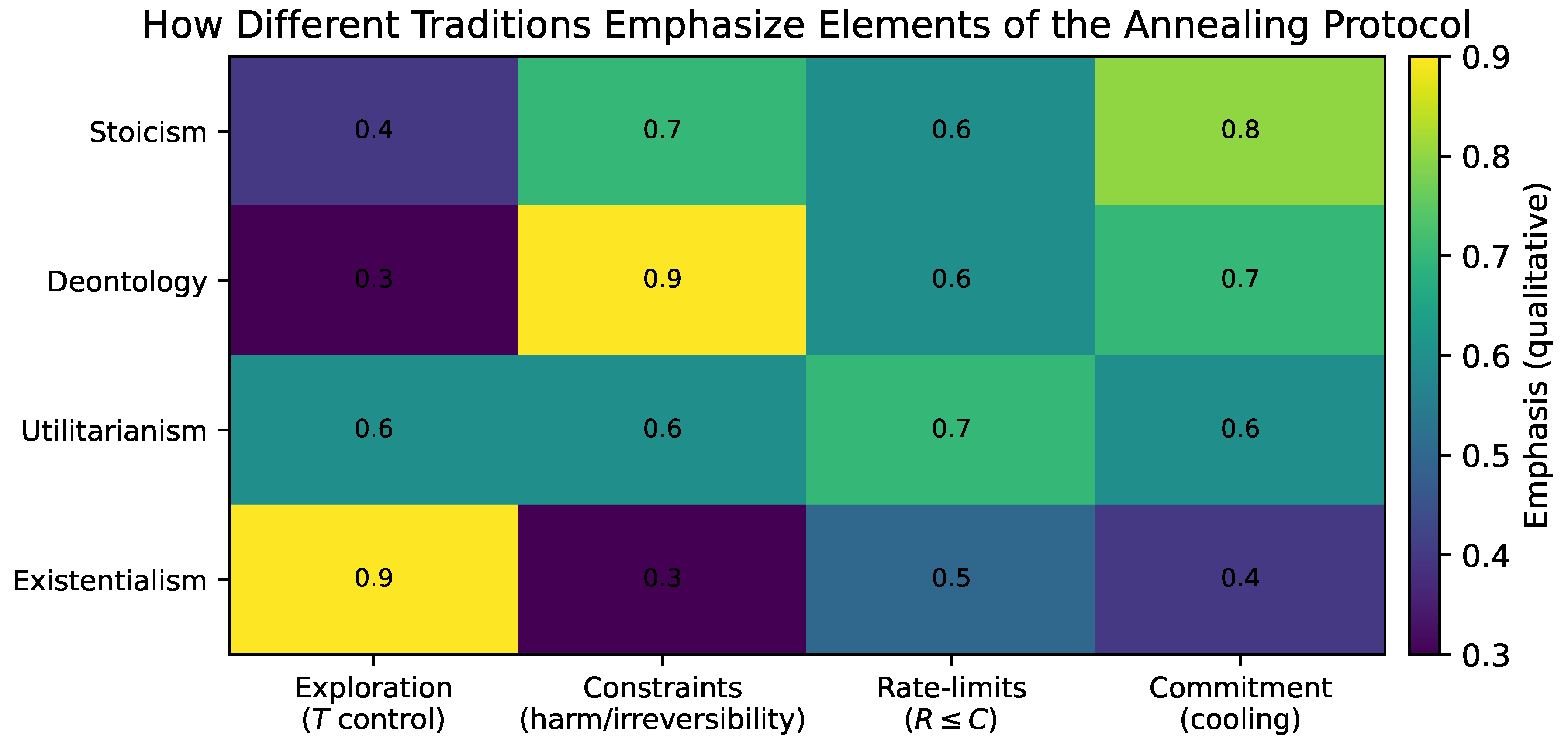

For readers interested in how this framework relates to existing philosophical traditions—including Stoicism, utilitarianism, existentialism, and process philosophies—a concise comparative positioning is provided in Appendix A.

2. Life as a Consequence of Nature

Life did not arise as the execution of a plan. It emerged as a consequence of physical law: matter driven far from equilibrium by persistent gradients can form, maintain, and reproduce structured states while exporting entropy to the environment. This is the central thermodynamic insight behind the classic view of organisms as “order” maintained through dissipation rather than equilibrium [

9,

10]. In modern terms, living systems are best understood as open, nonequilibrium processes whose stability depends on sustained flows and on the continual processing of gradients [

11].

This framing matters for the aims of this paper. If life is a consequence of how systems behave under gradients and constraints, then it is legitimate—and often necessary—to use the same structural language (gradients, entropy, capacity, exploration, stabilization) when reasoning about biological, cognitive, and social adaptation. The claim is not that humans are reducible to physics, but that humans are part of nature, and therefore subject to the same constraint logic that governs other complex adaptive systems.

2.1. Gradients as the Universal Change Catalyst

A gradient is a spatial or temporal difference in a quantity that can drive flux and enable work. Physical examples include temperature differences, chemical potential differences, and concentration gradients; when such gradients exist, systems can extract work and undergo irreversible change. When gradients vanish, systems relax toward equilibrium and dynamics slow or cease.

The crucial point is that gradients do not encode outcomes. A gradient specifies an opportunity for change, not a blueprint for what the system should become. As a result, the structures that emerge under gradients are not designed from above. They are discovered through local interactions and constrained by what is dynamically accessible.

2.2. Bottom-Up Emergence and the Failure of Blueprints

Blueprint thinking treats complex outcomes as if they were specified in advance: one chooses a goal, commits to a plan, and executes. This intuition is powerful in engineering and institutions, but it is not how natural complex systems operate. In bottom-up systems, components respond locally to constraints and signals; global organization emerges from interaction, feedback, and selection among viable configurations.

This distinction becomes practically important under changing environments. Blueprint strategies perform well when the landscape is stable: early specialization and early commitment can be optimal if gradients and demands remain predictable. But when the landscape shifts, early commitment can create brittleness. In the language developed later, blueprints correspond to premature stabilization: the system “cools” into a narrow set of configurations before it has sampled enough of the space to remain robust to future gradients.

2.3. Stability Is Contingent, Not Guaranteed

From an entropy-based perspective, stability is not the default state of nature; it is a transient achievement under continuing flux. Ordered structures persist only so long as (i) gradients continue to supply usable free energy, and (ii) the structure remains an effective pathway for dissipating those gradients. When gradients change or constraints tighten, previously stable configurations can become maladaptive or collapse.

This reframes “success” as conditional. A configuration can be locally optimal under yesterday’s gradients and fragile under tomorrow’s. This is not a moral claim; it is a structural one. Nature rewards neither comfort nor ambition. It simply enforces constraints and selects what remains viable under shifting conditions.

2.4. Implications for Professional Life in the AI Age

The AI age makes this natural-law framing operational. Task-based accounts of automation emphasize that technological change reallocates work by reshaping task compositions, often requiring continual reconfiguration rather than once-off qualification [

1,

2]. This introduces a steep external gradient for individuals and organizations: the need to retrain, respecialize, and redefine roles at a rate that can exceed historical norms.

The most exposed populations are often those whose careers were built as blueprints. Traditionally professional societies reward early specialization, credentialing, and identity locking (medicine, law, engineering, actuarial science). Under slow change, that strategy is robust. Under rapid AI-driven change, it can become a liability: the system has cooled early into a deep local minimum, with high irreversibility and reduced optionality. When displacement and retraining pressures arrive late, adaptation is required under tighter constraints and with less reversibility.

This motivates a central thesis of the paper: in nonstationary environments, the key variable is not whether one has chosen the “right” blueprint, but whether one has preserved and trained the capacity for exploration and reconfiguration before gradients become unavoidable. The next section formalizes these intuitions in thermodynamic terms by defining entropy, gradients, and free energy precisely, establishing the mathematical substrate for the later move to information, capacity, and self-entropy.

3. Thermodynamic Entropy and the Role of Gradients

Thermodynamic entropy provides the first and most fundamental setting in which the logic of this work can be stated precisely. Long before concepts such as information, learning, or agency arise, physical systems already exhibit a universal pattern: when gradients exist, structure forms; when gradients vanish, dynamics stagnate. Life itself emerges not as an exception to thermodynamic law, but as a consequence of it [

9,

10].

3.1. Entropy as a State Variable

In classical thermodynamics, entropy

S is a state function that quantifies the number of microscopic configurations compatible with a macroscopic description. For a system with internal energy

U, volume

V, and particle number

N, entropy is defined (up to an additive constant) by

where

is the reversible heat absorbed and

T the absolute temperature. The second law of thermodynamics states that entropy increases in isolated systems.

However, entropy alone does not explain the emergence of structure. A homogeneous equilibrium state has maximal entropy but is dynamically inert. What matters is not entropy as a scalar quantity, but entropy production driven by gradients.

3.2. Gradients as Drivers of Irreversible Dynamics

A gradient is a spatial or temporal variation in an intensive quantity such as temperature, chemical potential, or pressure. Formally, gradients appear as derivatives of thermodynamic potentials, for example

Gradients break symmetry and generate fluxes. Heat flows down temperature gradients, particles diffuse down chemical potential gradients, and mechanical work is extracted from pressure gradients.

The local rate of entropy production

can be written schematically as

where

are fluxes and

the corresponding thermodynamic forces [

10,

11]. Without gradients (

), fluxes vanish and the system ceases to evolve.

3.3. Open Systems and the Emergence of Structure

Living systems are open systems maintained far from equilibrium by sustained gradients—solar radiation, redox potentials, and nutrient flows. Under these conditions, entropy production does not destroy structure; it enables it. Dissipative structures such as convection cells, chemical oscillations, and metabolic networks arise precisely because they process gradients efficiently [

10].

This observation is foundational: order does not arise despite entropy, but because entropy production is constrained by structure. Systems that process gradients more effectively persist longer.

3.4. Cooling, Trapping, and Metastability

As gradients weaken or are exhausted, systems relax toward equilibrium. In rugged energy landscapes, this relaxation often leads to metastable states—local minima separated by barriers. Rapid cooling suppresses fluctuations and prevents exploration of alternative configurations, while slow cooling allows broader sampling before stabilization.

This physical insight foreshadows simulated annealing, where controlled stochasticity enables systems to escape local optima before committing to stable configurations.

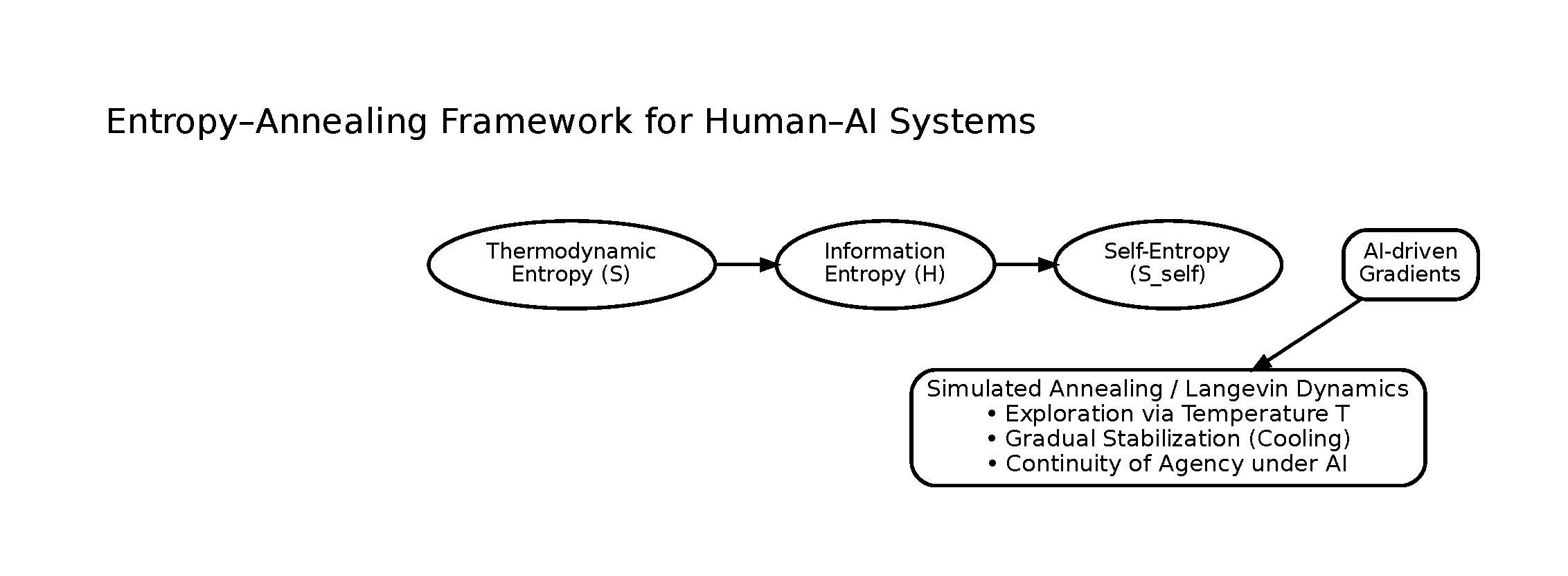

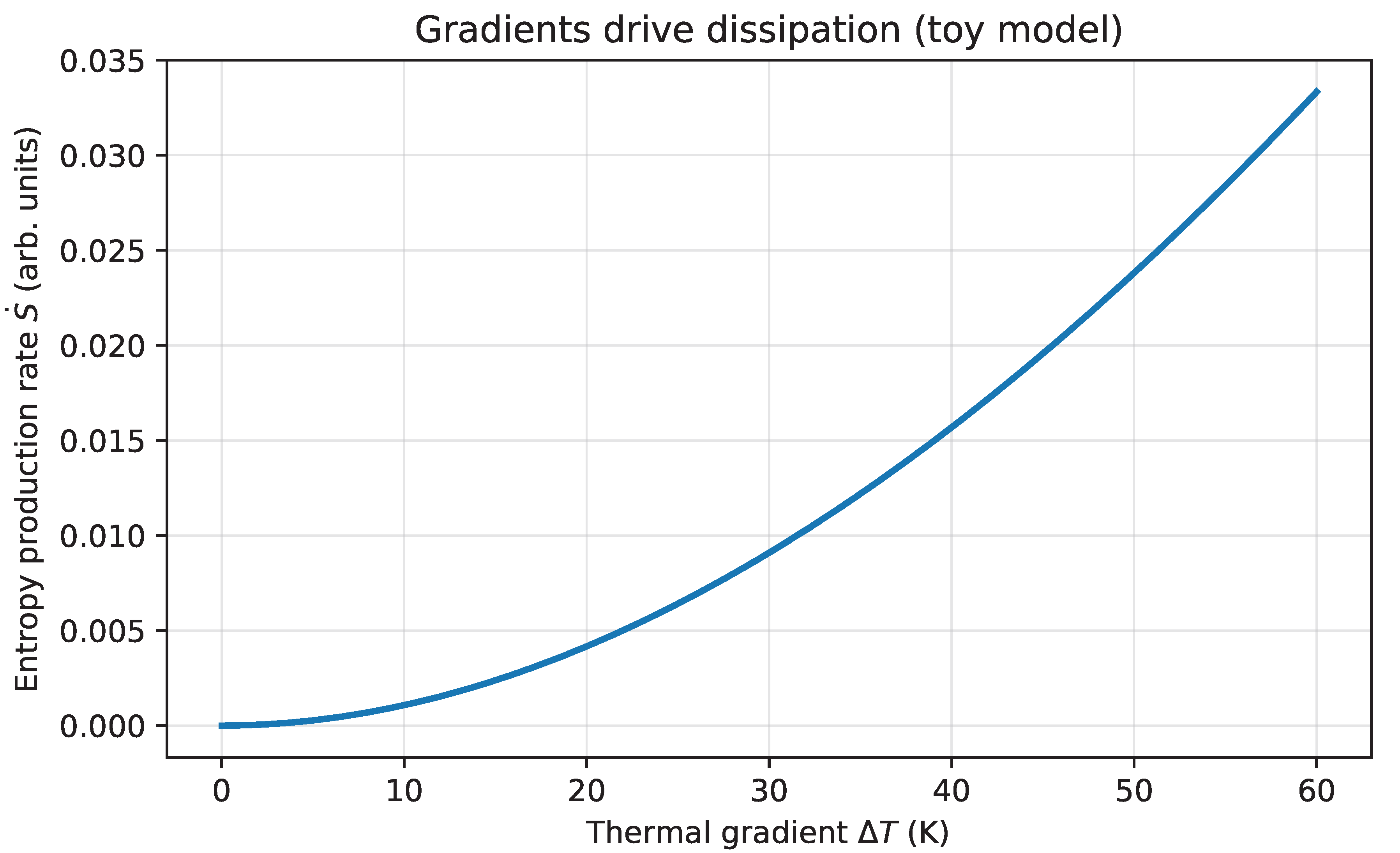

Figure 1.

Gradients drive dissipation in a minimal toy model: as a temperature gradient increases, the associated entropy production rate increases. This figure is schematic and intended to build intuition for the role of gradients as the driver of irreversible change.

Figure 1.

Gradients drive dissipation in a minimal toy model: as a temperature gradient increases, the associated entropy production rate increases. This figure is schematic and intended to build intuition for the role of gradients as the driver of irreversible change.

3.5. Why Gradients Matter Beyond Physics

The role of gradients generalizes beyond thermodynamics. In later sections, we show that informational uncertainty, learning dynamics, and human identity evolution follow the same structural logic. Change occurs only when gradients are encountered; stagnation occurs when systems cool too early.

This distinction becomes practically important under changing environments. When gradients steepen—whether due to environmental shocks or technological change—systems that have prematurely stabilized struggle to adapt. Those that have preserved exploratory capacity respond more robustly.

The next section makes the thermodynamic–informational bridge explicit, showing how entropy, free energy, and gradients reappear in the mathematics of inference and learning.

4. From Thermodynamics to Information

Section 3 established the core physical logic: gradients generate fluxes; fluxes generate entropy production; and far-from-equilibrium conditions can support persistent structure. The purpose of this section is to make explicit why it is valid to move from thermodynamic entropy to information-theoretic entropy without changing the underlying constraint logic. The bridge is not metaphorical. It is structural: both domains are governed by probability distributions over accessible states, and both admit variational principles in which uncertainty (entropy) trades off against cost.

4.1. Entropy as Uncertainty over Accessible States

In statistical physics, a macroscopic description of a system corresponds to a probability distribution over microscopic configurations. The Gibbs entropy for a discrete state space

with probabilities

is

where

converts dimensionless uncertainty into physical units. In information theory, Shannon introduced the analogous quantity for a random variable

X,

measured in bits (log base 2) or nats (natural log) [

14,

15]. The functional identity between is not accidental. In both cases entropy measures the effective breadth of the distribution: how many states are meaningfully accessible under the constraints that define

p.

The difference is interpretive and dimensional. Thermodynamic entropy is uncertainty over microstates consistent with a macroscopic description; Shannon entropy is uncertainty over symbols, hypotheses, or messages. But in both cases, entropy quantifies uncertainty under constraint. This shared structure is precisely what allows the thermodynamic language of gradients and dissipation to be carried into informational settings.

4.2. Free Energy and the Cost–Uncertainty Trade-Off

Thermodynamic equilibrium at temperature

T is characterized by the Boltzmann distribution

where

is the physical energy. A central result is that Equation (

6) can be derived variationally:

minimizes the Helmholtz free-energy functional

over distributions

q [

25]. The structure is explicit: expected energy is traded against entropy. High temperature weights entropy and yields broad exploration; low temperature weights energy and concentrates probability mass into low-energy regions.

In learning and inference, the same mathematics reappears when we interpret

x as a hypothesis or parameter vector and define an informational energy by negative log probability. For observed data

D,

Low energy corresponds to high posterior plausibility. Substituting Equation (

8) into Equation (

7) yields the same cost–uncertainty trade-off, now interpreted as balancing explanatory fit against uncertainty over explanations. This variational viewpoint underlies deterministic annealing and related methods in which optimization proceeds via controlled entropy reduction [

21,

22].

4.3. Information Is Physical

The thermodynamics→information bridge is further strengthened by the fact that information processing has irreducible physical costs. Landauer’s principle shows that logically irreversible operations (such as bit erasure) require a minimal dissipation of heat [

16]. In modern stochastic thermodynamics, irreversibility along trajectories is quantified directly through entropy production [

11]. Taken together, these results justify treating information as a constrained physical resource rather than an abstract bookkeeping device.

This point becomes important when we later discuss capacity limits and agency collapse. If uncertainty reduction and information integration are constrained processes, then the ability of a system to remain adaptive is bounded not only by preferences or motivation, but by hard rate limits on what can be processed reliably over time.

4.4. Why This Bridge Matters for the AI Age

AI systems increase the volume, velocity, and availability of information. They can generate predictions, counterfactuals, and options at rates that exceed the integration capacity of individuals and organizations. Empirical work on cognitive load and information overload is consistent with a simple structural diagnosis: performance and learning degrade when processing demands exceed integrative capacity [

31,

33], and expanding choice sets can reduce decision quality and motivation [

34].

The implication is that informational gradients can destabilize agency in the same way that steep physical gradients can destabilize fragile structures. This motivates the next section, where we define information entropy, informational gradients, and channel capacity explicitly. The thesis is that the AI age changes human outcomes not merely by adding tools, but by steepening the informational landscape in which coupled human–AI systems must adapt.

5. Information Entropy and Informational Gradients

Section 4 established the formal continuity between thermodynamic and informational entropy: both quantify uncertainty over accessible states, and both support a variational interpretation in which uncertainty trades off against cost. We now develop the information-theoretic side explicitly. The purpose is twofold: (i) to define the quantities that will later serve as primitives for “self-entropy”; and (ii) to introduce

rate limits—hard constraints on reliable integration—that become decisive in the AI age.

5.1. Shannon Entropy, Conditional Entropy, and Mutual Information

Let

X be a discrete random variable with distribution

. Shannon entropy is

measuring uncertainty in bits (log base 2) or nats (natural log) [

14,

15].

For two random variables

with joint distribution

, the conditional entropy

quantifies residual uncertainty about

X after observing

Y. The mutual information

measures the expected reduction in uncertainty about one variable gained by observing the other [

15]. These quantities provide a precise language for “how much the system learns” when it receives a signal.

5.2. Informational Gradients as Uncertainty Reduction Under Interaction

In physical systems, gradients in intensive variables drive fluxes. In informational systems, the analogous drivers are

differences in uncertainty over outcomes, states, or explanations. A simple representation is to treat negative log probability as an informational “energy” [

25]:

so that high-probability states have low informational energy. Changes in evidence, context, or interaction reshape

and therefore reshape the energy landscape.

An

informational gradient can then be operationalized as a local sensitivity of uncertainty (or surprise) to controllable variables (actions, queries, attention allocation). For example, suppose an agent selects an action

a that influences an observation

Y. A natural objective of exploration is to maximize expected information gain,

i.e., choose actions that are expected to reduce uncertainty most. This is the informational analogue of following a gradient: the system moves toward actions that produce the steepest expected reduction in uncertainty [

15].

This idea also clarifies why “more information” is not always beneficial. Information gain is only valuable to the extent that it can be integrated and used to update beliefs, policies, and commitments. That constraint is formalized by channel capacity.

5.3. Rate, Capacity, and the Reliability of Integration

Shannon’s channel coding theorem establishes that reliable communication over a noisy channel is possible only when the information rate

R does not exceed channel capacity

C:

where

C is the maximum achievable mutual information per channel use under the channel constraints [

14,

15]. When

, error rates cannot be driven arbitrarily low by any coding scheme.

This inequality will later become the central formal constraint on agency. The key move is to treat human adaptation and decision-making as an integration process operating under limited cognitive, emotional, and temporal bandwidth. If incoming options, signals, and counterfactuals arrive at an effective rate R that exceeds the system’s integrative capacity, then reliable updating fails: decisions become unstable, learning becomes noisy, and commitment collapses into either paralysis or premature closure.

Empirical literatures in cognitive load and information overload are consistent with this structural diagnosis: performance and learning degrade when processing demands exceed integrative limits [

31,

33], and expanding choice sets can reduce decision quality and motivation [

34]. Information theory provides the hard bound underlying these observed phenomena.

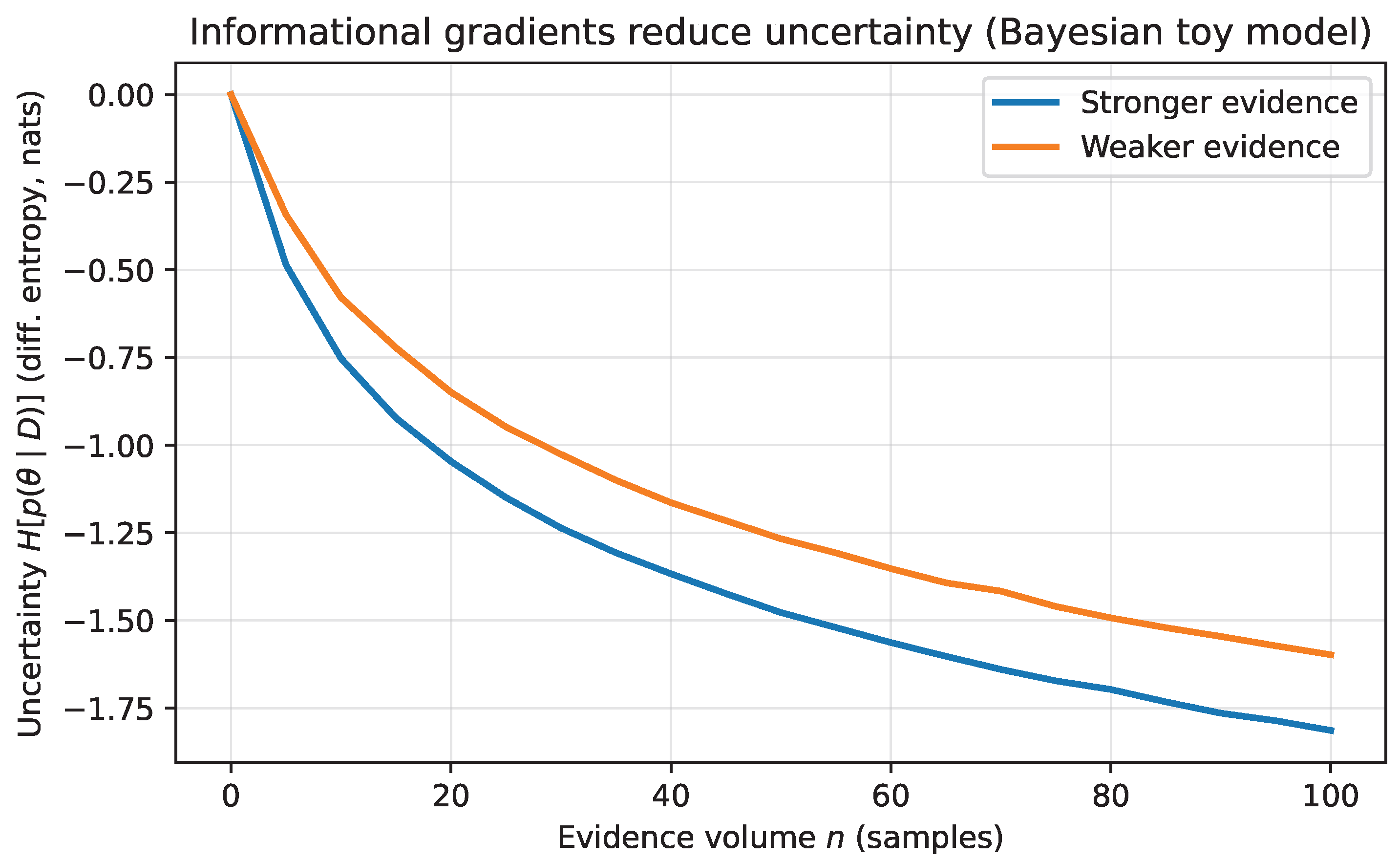

Figure 2.

Informational gradients reduce uncertainty: a simple Bayesian toy model illustrates how evidence concentrates the posterior distribution and reduces entropy. Stronger evidence produces faster entropy collapse than weaker evidence.

Figure 2.

Informational gradients reduce uncertainty: a simple Bayesian toy model illustrates how evidence concentrates the posterior distribution and reduces entropy. Stronger evidence produces faster entropy collapse than weaker evidence.

5.4. Implications for the AI Age

AI steepens informational gradients by increasing the volume and velocity of predictions, options, and comparisons. It can also reduce the marginal cost of generating new hypotheses and plans, encouraging constant exploration. This changes the landscape in which individuals and institutions must operate: the effective rate R of actionable information can rise faster than human integrative capacity, pushing coupled human–AI systems toward the regime .

The next section extends these concepts into the existential domain by defining a state space of the self and a corresponding self-entropy. The goal is to show that the same structural objects—entropy, gradients, rate limits, and controlled exploration—govern adaptation not only in physics and learning, but in the evolution of identity and agency under accelerating AI-driven change.

6. Self-Entropy and Capacity

Section 3,

Section 4 and

Section 5 established two domains in which the same structural logic repeats: (i) gradients create pressure for change; (ii) entropy quantifies the breadth of accessible states; and (iii) stabilization is a regulated reduction of that breadth under constraint. We now extend this logic to the existential domain by defining a state space for the self and a corresponding self-entropy. The purpose is not to reduce lived experience to a scalar, but to introduce an

inspectable object that can later be coupled to informational gradients and capacity limits in the AI age.

6.1. State Space of the Self

Let denote a set of possible self-states available to an individual at time t. Each represents a coherent configuration of identity: roles, values, commitments, skills, relationships, and narrative stance. The precise content of a state is application dependent; what matters is that represents plausible ways of being that the individual experiences as accessible.

At any moment, the individual implicitly assigns a probability distribution over this space,

shaped by prior experience, culture, biology, environment, and accumulated commitments. In practice

need not be explicit; it is encoded in preference, affect, perceived feasibility, and habitual action.

6.2. Definition of Self-Entropy

We define self-entropy as the Shannon entropy of the distribution over self-states:

Self-entropy measures the breadth of identity space experienced as available. High corresponds to a wide sense of possibility: multiple futures feel live and reachable. Low corresponds to a narrow identity distribution: a small number of futures dominate, and alternatives feel remote or impossible.

This definition is descriptive, not normative. High self-entropy is not inherently good, nor is low self-entropy inherently bad. As in thermodynamics and information theory, what matters is how entropy changes under constraint, and whether reduction is regulated or premature.

6.3. Self-Entropy Is Not Chaos

It is tempting to equate high self-entropy with confusion or instability. This is a mistake. Entropy measures uncertainty over accessible states, not dysfunction. In physical systems, high entropy does not imply random motion; it implies many accessible microstates. In inference, high entropy does not imply ignorance; it implies openness to revision. Likewise, high self-entropy does not imply lack of identity; it implies that identity has not collapsed into a single narrow narrative.

Conversely, low self-entropy may reflect coherence, commitment, and purpose. But it may also reflect premature closure: a collapse of possibility induced by safety, external expectations, or institutional reinforcement. The mathematics does not judge; it clarifies the structural regime.

6.4. Experiential Gradients and Pressure to Change

As in the physical and informational domains, self-entropy does not change spontaneously. It changes under gradients. In the existential domain, gradients appear as experienced discrepancies between (i) current self-states and environmental demands, (ii) current identity and internal drives, or (iii) current life and perceived alternatives. These gradients may be felt as boredom, restlessness, dissatisfaction, ambition, attraction, or crisis.

A useful formal correspondence is to define an “energy” over self-states using negative log plausibility:

so that highly plausible identities have low energy and implausible identities have high energy. Experiences that introduce new information, new exemplars, or new constraints reshape

and therefore reshape

. When a previously unlikely identity becomes salient—through exposure, success, failure, or encounter—a gradient is introduced that pressures the distribution to shift.

Importantly, gradients create necessity. Without gradients, the distribution remains static: the system “cools” into a stable basin and self-entropy collapses through routine reinforcement.

6.5. Capacity as a Hard Constraint on Integration

Self-entropy describes

how many futures feel available. Capacity describes

how fast the system can integrate change. Information theory provides the relevant concept: a rate limit on reliable integration. For a noisy channel, Shannon’s theorem implies that reliable transmission is possible only when the information rate does not exceed channel capacity [

14,

15]:

We interpret

as the effective capacity of the human system to integrate information into stable updates of belief, behavior, and commitment. This capacity is constrained by cognitive resources, time, emotional regulation, social context, and physiological state. Empirical work supports the general form of this constraint: performance and learning degrade when processing demands exceed integrative limits [

31,

33], and expanding option sets can reduce decision quality and motivation [

34].

When , updating becomes unreliable. The subjective signature is familiar: overwhelm, fragmentation, paralysis, impulsive commitment, or oscillation. This is not primarily a failure of willpower. It is a violation of a rate constraint.

6.6. AI as an Amplifier of Informational Gradients

AI systems can dramatically increase the effective rate by producing more options, faster feedback, more counterfactuals, and more comparisons. In coupled human–AI systems, this can push individuals and organizations into the regime , causing a collapse of agency even as the system appears to be “more informed”. This mechanism will be developed explicitly in later sections; here we emphasize the structural implication: in the AI age, preserving agency requires managing rate as much as managing choice.

6.7. Meaning as Regulated Entropy Reduction

A final point is critical for the arc of the paper. Self-entropy must eventually decrease if the self is to become coherent. Commitment is, in a precise sense, entropy reduction: probability mass concentrates into a narrower set of identities and trajectories. The question is not whether entropy should decrease, but whether the reduction is regulated—supported by sufficient exploration and integration capacity—or premature, producing a brittle local optimum that later destabilizes under steep gradients. This is the basis for the annealing dynamics introduced next.

The next section will unify the physical, informational, and existential domains under a single stochastic dynamical form and interpret simulated annealing as the general mechanism by which complex systems without foresight discover order under constraint.

7. Unified Dynamics and Simulated Annealing

Section 3,

Section 4,

Section 5 and

Section 6 developed three parallel domains: thermodynamic entropy (structure under physical gradients), information entropy (uncertainty under informational gradients), and self-entropy (possibility under existential gradients) subject to capacity constraints. We now unify these domains under a single dynamical form. The purpose of this section is to state, clearly and formally, the process that connects gradients to exploration and exploration to stabilization:

controlled stochastic gradient flow. This is the common mechanism by which complex systems without foresight discover viable structure under constraint.

7.1. A Single Dynamical Form Across Domains

Let

denote a system state evolving in time. The interpretation of

x depends on domain: a physical configuration, a hypothesis or parameter vector, or a self-state in identity space. Let

be an effective energy (or cost) landscape, capturing what is locally stable or costly under the system’s constraints at time

t. We consider the canonical continuous-time model of overdamped Langevin dynamics:

where

is standard Brownian motion and

is an effective temperature controlling stochastic exploration [

23,

24]. The first term drives descent along local gradients; the second injects fluctuations that enable exploration and barrier crossing.

At fixed temperature

T, the stationary distribution of Equation (

19) under appropriate conditions is a Gibbs distribution,

making explicit the role of temperature as a knob controlling distributional breadth: higher

T spreads probability mass across more states; lower

T concentrates it into lower-energy basins [

24].

7.2. Domain Instantiations

Thermodynamics.

In thermodynamics,

x represents a physical configuration,

is physical energy, and

T is temperature. Cooling reduces entropy by confining the distribution to lower-energy regions, but only if sufficient thermal exploration occurs first; otherwise the system becomes trapped in metastable local minima. This is the physical origin of annealing logic [

10,

11].

Learning and inference.

In learning,

x represents hypotheses or model parameters, and a natural energy is negative log posterior,

so that low energy corresponds to high posterior plausibility. Temperature corresponds to the degree of exploration in hypothesis space: high

T tolerates unlikely explanations; low

T concentrates around dominant models. This connects directly to Bayesian learning dynamics and stochastic-gradient sampling [

25,

26]. Deterministic annealing makes the trade-off explicit by minimizing a free-energy functional that balances expected cost against entropy [

21,

22].

The self.

In the existential domain, x denotes a configuration of identity and commitments (a point in self-state space). The energy encodes misfit, fragility, ethical load, irreversible loss, and loss of agency. Temperature corresponds to tolerance for uncertainty and the capacity to explore: trying new roles, projects, relationships, or ways of being. Premature cooling traps the individual in locally stable but potentially misaligned identities; failure to cool at all yields fragmentation and incoherence. A viable self is one that anneals.

7.3. Simulated Annealing as Controlled Entropy Reduction

Simulated annealing is the strategy of controlling

to discover low-energy configurations in rugged landscapes [

17,

18,

19,

20]. High initial temperature enables barrier crossing and broad exploration; gradual cooling concentrates probability mass into stable basins. Crucially, simulated annealing does not assume that the global optimum is known in advance. It assumes only that local gradients are observable, exploration is costly but informative, and constraints tighten over time.

The structural lesson generalizes: exploration is not the opposite of optimization; it is the precondition for meaningful optimization in rugged, nonconvex landscapes. Without stochastic sampling, systems converge reliably—but locally. They settle into configurations that are stable relative to their immediate surroundings, not necessarily those that are globally viable or future-robust.

7.4. Ambition as Temperature Control

Within this framework, ambition can be reinterpreted as the ability to sustain non-zero effective temperature in the absence of external pressure. In environments of abundance and safety, gradients are muted and natural cooling dominates; decays, exploration collapses, and the system stabilizes early. Ambition counteracts this decay by injecting controlled randomness: the deliberate sampling of new regions of state space before external gradients force abrupt reheating.

This interpretation has a practical implication that will recur throughout the paper: in nonstationary environments, robustness is achieved not by early convergence, but by maintaining the capacity to explore and reconfigure at a rate that remains within integration bounds (

Section 6).

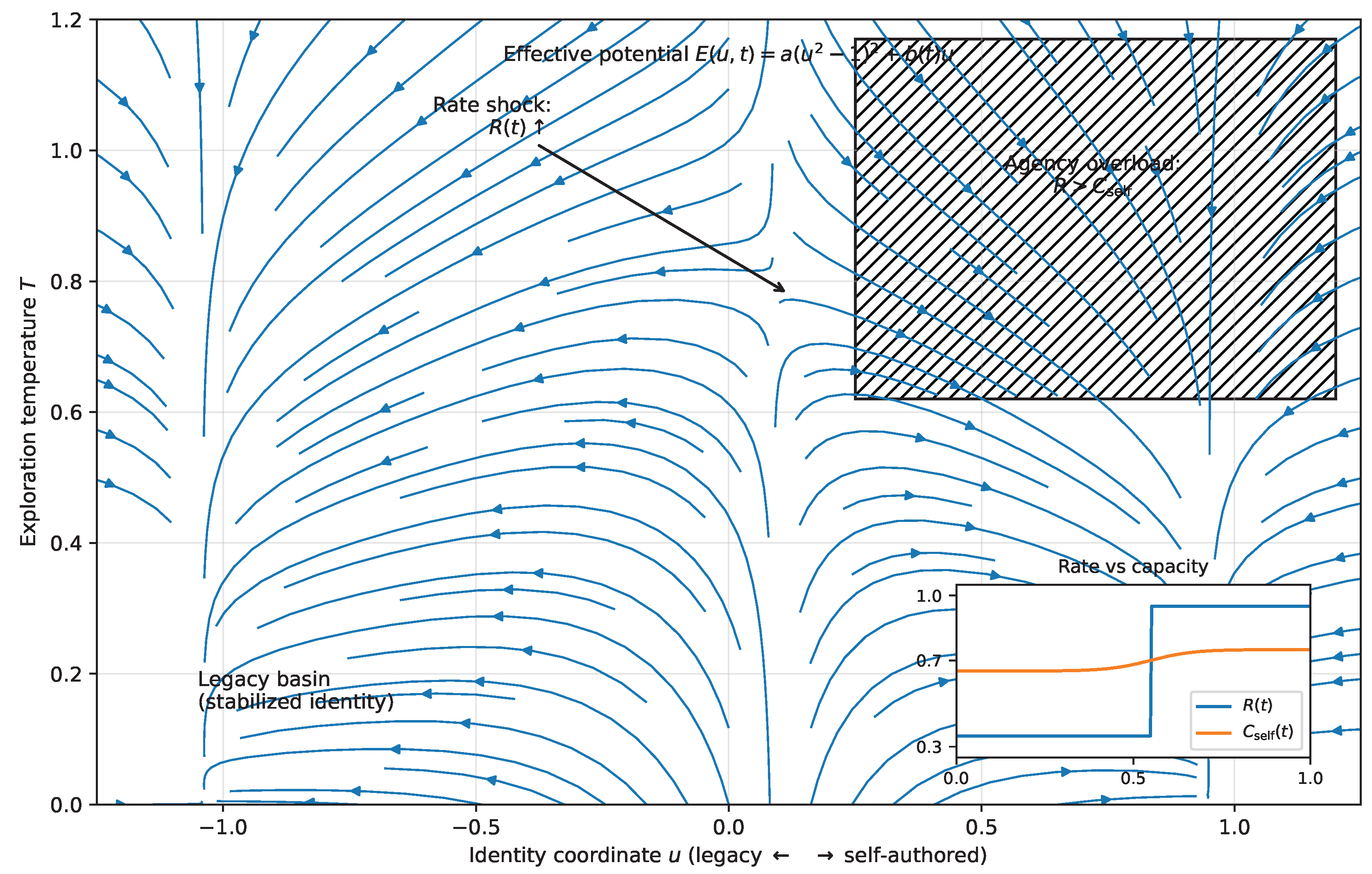

7.5. A Phase Portrait as Intuition for the Unified Dynamics

Although Equation (

19) is high-dimensional in most realistic settings, its qualitative behavior can be visualized in low-dimensional projections. In later sections we will project the self-state dynamics onto a reduced coordinate

u (along the dominant self-gradient) and the effective temperature

T, yielding a phase portrait that distinguishes regimes of (i) premature cooling and entropic collapse, (ii) healthy exploration and gradual stabilization, and (iii) overheating and fragmentation.

This phase-portrait view is not merely illustrative: it provides a geometric language for decision protocols. If identity evolution is an annealing process, then guidance consists of controlling temperature schedules, preserving reversibility when possible, and ensuring that exploration proceeds at a rate the system can integrate.

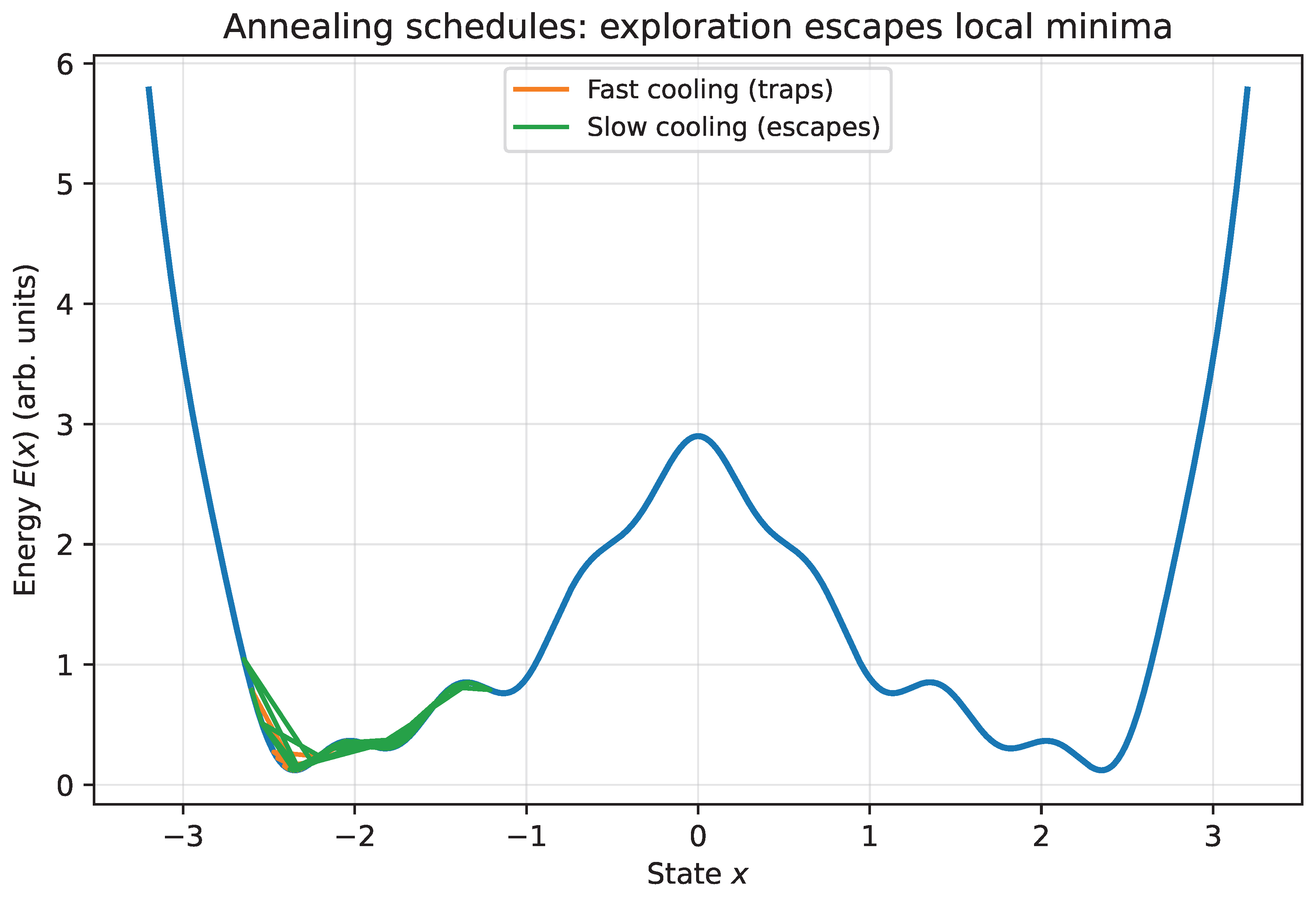

Figure 3.

Annealing schedules in a rugged landscape: slower cooling permits exploration and escape from local minima; faster cooling tends to trap the trajectory. This is a schematic illustration of why stochastic sampling is a precondition for robust optimization in rugged landscapes.

Figure 3.

Annealing schedules in a rugged landscape: slower cooling permits exploration and escape from local minima; faster cooling tends to trap the trajectory. This is a schematic illustration of why stochastic sampling is a precondition for robust optimization in rugged landscapes.

7.6. Relation to Active Inference

The annealing dynamics used here are closely related to the variational formulations of active inference, where biological agents minimize a free-energy functional balancing expected cost against entropy [

28,

35]. In that framework, adaptive behavior emerges through inference over hidden states under a generative model of the world. The present work adopts the same mathematical structure, but treats temperature as an explicit, time-dependent control parameter rather than an implicit constant. This distinction becomes critical in non-stationary environments, where gradients steepen faster than inference alone can stabilize identity or policy. Under such conditions, premature entropy reduction leads to brittle commitments, even when prediction error is locally minimized.

Unlike standard active inference formulations, which emphasize surprise minimization, the annealing perspective foregrounds controlled exploration under constraint as the prerequisite for meaningful stabilization. This shift is essential in environments shaped by artificial intelligence, where option generation and informational gradients accelerate beyond biological integration limits.

Section 9 introduces a concrete instantiation of premature cooling under abundance—Anna—as a worked example. Her case illustrates how late reheating under tight constraints produces oscillation and paralysis, and why this pattern becomes increasingly common in the AI age.

8. Materials and Methods

This study is theoretical and computational in nature. No human or animal subjects were involved, and no empirical data were collected. The methods consist of analytical modeling, numerical illustration, and qualitative synthesis grounded in established principles from statistical physics, information theory, and dynamical systems.

8.1. Unified Stochastic Dynamics

The central modeling framework is based on overdamped Langevin dynamics and simulated annealing. System evolution is described by stochastic differential equations of the form

where

denotes the system state,

an effective energy or cost functional,

a time-dependent temperature controlling exploration, and

a Wiener process. This formalism is applied consistently across physical, informational, and existential domains by appropriate interpretation of the state variables and energy functions.

Phase portraits and reduced-order models are constructed by projecting high-dimensional dynamics onto dominant order parameters, such as identity alignment and effective exploration capacity. Analytical results are supported by schematic simulations illustrating qualitative system behavior under varying temperature schedules and rate constraints.

8.2. Information-Theoretic Capacity Constraints

Agency is formalized as a rate-limited process using Shannon’s channel capacity framework. The relationship between environmental change rate R and individual capacity is expressed through inequalities of the form , with qualitative failure modes analyzed when this bound is violated. These formulations are analytical and conceptual rather than empirical.

8.3. Computational Tools

All figures and simulations were generated using Python (version 3.11). Visualization employed Matplotlib (version 3.8) for continuous plots and Graphviz (version 9.0) for block diagrams and system schematics. Numerical examples are illustrative and intended to clarify structural dynamics rather than provide quantitative prediction. Source code used to generate figures is available from the author upon reasonable request.

8.4. Use of Generative Artificial Intelligence

Generative artificial intelligence tools were used to assist with drafting, code generation for figures, and iterative refinement of mathematical exposition. All theoretical formulations, interpretations, and conclusions were developed and verified by the author.

9. Premature Cooling Under Abundance: Anna as a Professional Shock Case

We now introduce Anna as a concrete instantiation of the dynamics developed in

Section 6Section 7. The purpose is not biographical detail for its own sake, but clarification: to show how a common professional trajectory becomes brittle under AI-driven gradients. Anna is representative of a class of highly successful professionals whose lives followed a stable blueprint: early specialization, credentialing, steady promotion, and identity consolidation in a buffered environment [

1,

2].

Anna grew up in an environment of exceptional stability and expectation. Both of her parents are medical professionals. On her father’s side, the family is well established, respected, and embedded in public institutions. On her mother’s side, there is a strong narrative of upward mobility: her maternal grandfather was an entrepreneur, and her mother was the first in her family to study medicine. Together, these forces created a world that was materially secure, intellectually demanding, and ethically coherent.

From early on, the signal Anna received was clear: safety was abundant, and excellence— particularly intellectual excellence—was expected. Achievement was rewarded not as exploration, but as confirmation of competence and worth. Anna responded optimally to this landscape. She performed at the top of her class, excelled at university, and qualified as an actuary. Her professional career progressed rapidly. Promotions followed. External validation accumulated. By conventional standards, Anna’s life is a success.

Anna is married to a lawyer whose career followed a similar blueprint. His professional path was likewise defined by early specialization, credentialing, and institutional stability. Together, they form a household whose financial risk is buffered and whose social standing is secure. Their world is small, but stable. Even in the face of disruption, their immediate economic survival is unlikely to be threatened.

Structurally, however, this environment suppressed gradients. Financial risk was absorbed. Career paths were predictable. Identity and self-worth were tightly coupled to professional competence and institutional recognition. In annealing terms, Anna’s life cooled early. Her effective temperature declined not because of fear or constraint, but because nothing in her environment required continued stochastic exploration. Local minima were deep, comfortable, and continuously reinforced.

This is abundance at its most effective—and its most dangerous.

The AI age introduces the missing gradient. As automation, model-driven decision systems, and task decomposition accelerate, roles that once appeared stable are restructured or eliminated [

1,

2]. Suppose Anna’s actuarial role is significantly altered or displaced. New tools, new workflows, and new expectations appear. The volume and velocity of information required to remain professionally viable increase rapidly. Retraining is no longer episodic; it becomes continuous.

Crucially, the dominant loss in this scenario is not financial fragility. Household resources and family support buffer economic shock. The primary loss is a loss of identity-based self-worth and perceived agency. Anna’s stabilizing basin was built on competence-signaling: being needed, being relied upon, being correct. When the role collapses, the system loses its main source of coherence. This produces a sharp increase in an effective loss term associated with narrative continuity and status, and an even sharper increase in an agency penalty: the felt inability to steer outcomes despite sustained effort.

In the language of

Section 6, AI-driven restructuring also increases the effective information rate

: tool churn, retraining demands, and option velocity rise sharply. Even when economic fragility remains low, an agency collapse occurs when

exceeds the system’s integrative capacity

. Learning becomes noisy, decisions destabilize, and commitment oscillates.

The situation is compounded by coupling. Anna’s husband faces similar pressures in the legal profession, where AI-assisted research, document generation, and case analysis restructure traditional roles. The household therefore experiences correlated gradients. Two early-cooled systems are reheated simultaneously. Mutual reinforcement that once stabilized the system now amplifies uncertainty.

Anna’s subjective experience is therefore not mysterious. She may feel overwhelmed, fragmented, or paralyzed despite being intelligent, disciplined, and historically successful. This is exactly what one expects from a system that cooled early in a buffered landscape and is now reheated abruptly under tight constraints.

Importantly, this analysis is not moral. It does not claim that Anna lacks resilience or courage. It identifies a structural regime: premature stabilization under abundance, followed by late gradient exposure. The relevant question is no longer “What is the right blueprint?” but:

How can exploration be reintroduced at a rate the system can integrate, while preserving reversibility and minimizing irreversible loss?

This question admits of principled answers. It requires pacing, temperature control, and capacity-aware exploration rather than binary decisions.

9.1. Why Professionals Are Uniquely Vulnerable

A distinctive feature of the AI transition is that it targets occupations historically treated as protected by credentials. Medicine, law, actuarial science, accounting, and related professions have long operated as “blueprint careers”: a front-loaded investment in education followed by decades of relatively stable identity and practice. This structure encourages early cooling. Competence becomes narrowly defined by a fixed corpus of knowledge, institutional signaling substitutes for continued exploration, and long time horizons reinforce commitment to a single basin of expertise.

AI steepens gradients precisely where this model is most rigid. The relevant shift is task-based: professional work is decomposed into smaller units, many of which are automatable or re-allocatable between humans and machines [

1,

2]. Even when entire occupations persist, the internal task composition changes rapidly, and the rate at which tools, standards, and competitive baselines update increases. For the individual professional, this manifests as a rise in effective information rate

and an increase in volatility of the local energy landscape

: what counted as competence last year may not count next year.

The result is a specific fragility of early-cooled systems. Professionals often have high general intelligence but low practiced exploration: their training optimized for convergence on a single validated pathway. When AI imposes abrupt retraining demands, the dominant loss is frequently not economic survival but agency and self-worth, because competence-signaling is the core stabilizer of identity. In the terms of

Section 6, agency failure emerges when the option and retraining rate exceeds integration capacity,

. In such regimes, more information and more options do not increase freedom; they increase error, oscillation, and premature closure.

This observation has direct implications for policy and education. If AI-driven gradients make continuous reskilling structurally necessary, then capacity must be trained early, before steep gradients arrive. A schooling system designed around one-time specialization is optimized for a world with slow-changing landscapes. In the AI age, education must explicitly cultivate controlled exploration: the ability to sample new domains, update priors, and rehearse transition moves without catastrophic loss. In later sections we return to this implication and argue that “learning how to learn” is not an aspirational slogan but an annealing requirement: systems that do not practice exploration while constraints are loose become brittle when constraints tighten.

The next section formalizes Anna’s situation using the unified annealing dynamics and introduces a phase-portrait representation that will later support an explicit decision protocol for AI-driven professional adaptation.

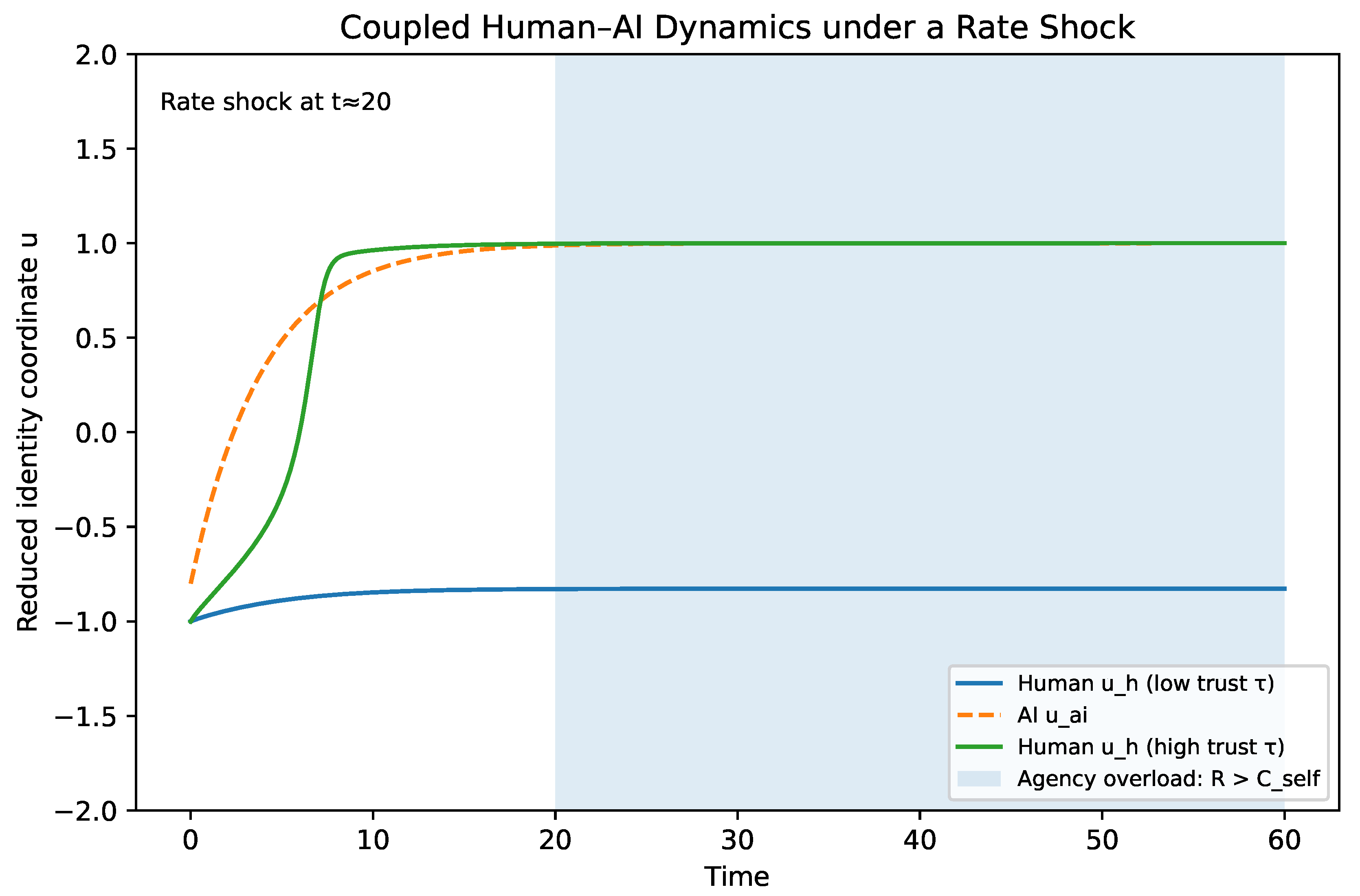

10. Phase Portrait: Identity, Agency, and Rate

The unified dynamics in

Section 7 describe high-dimensional stochastic gradient flow. For interpretability and for protocol design, we now reduce the self-dynamics to a low-dimensional phase portrait that makes three quantities explicit:

identity (where the system is in self-space),

agency (whether the system can reliably update), and

rate (how fast information and demands arrive).

10.1. A Reduced Coordinate for Identity

Let denote a reduced coordinate along the dominant axis of identity change. The left side () corresponds to the inherited/stabilized professional identity (legacy basin), while the right side () corresponds to a reconfigured, self-authored, and exploratory identity (novel basin). This projection does not claim that the self is one-dimensional; it claims only that in many high-stakes transitions, a single axis dominates decision-relevant motion.

We represent stability and misalignment by an effective potential

with (typically) multiple basins. A canonical choice is a double-well landscape whose relative depths can shift with time, representing a moving professional environment:

where

controls barrier height and

tilts the landscape as the environment changes.

10.2. Temperature as Controlled Exploration

Let

denote the effective self-temperature introduced in

Section 7. In the reduced model,

T governs how much stochastic exploration is possible in identity space. High

T enables barrier crossing and sampling of alternative selves; low

T collapses exploration and produces early stabilization.

A minimal mean-field dynamics consistent with the unified Langevin form is:

where

is the natural cooling rate (routine, reinforcement, comfort),

is the experienced gradient magnitude (pressure to change), and

captures sensitivity to gradients.

10.3. Rate and Capacity as the Agency Constraint

To make agency explicit, we introduce the information-rate constraint from

Section 6. Let

denote the effective rate at which the individual must integrate actionable information to adapt: tool churn, retraining demands, options, and evaluation updates. Let

denote integrative capacity.

Agency fails when

exceeds capacity:

For phase-portrait purposes, define an

agency margin (positive when stable, negative when overloaded):

When , updates become unreliable and the system exhibits oscillation, impulsive closure, or paralysis even if motivation is high. This makes “loss of agency” a structural condition rather than a moral interpretation.

To couple agency back into the identity landscape, we can include an agency penalty term in the effective energy:

where

is a nonnegative increasing function for

(e.g.,

) and

sets the strength of agency loss in the landscape. Intuitively, overload makes all moves feel more costly: exploration is punished by error and exhaustion.

10.4. Interpreting Anna’s Trajectory Under AI Shock

Anna’s situation (

Section 9) is a textbook case of a system that cooled early in a buffered professional environment and then encountered a late, steep gradient under AI-driven task restructuring. In this phase portrait:

Identity (u): Anna begins deep in the legacy basin (), because her professional blueprint encouraged early convergence.

Exploration (T): Natural cooling dominated for years, driving , collapsing self-entropy.

Rate (R): AI increases abruptly (tool churn and reskilling velocity), while cannot increase instantly.

Agency (): When , the agency margin becomes negative and the system enters an overload regime in which motion is noisy but integration is poor.

The critical point is that Anna can remain financially safe while still losing agency: the dominant loss is not economic fragility but identity coherence and self-worth (competence-signaling). This is why credentialed professionals are uniquely vulnerable: their stability is often built on narrow identity basins that are disrupted by task-level AI gradients.

10.5. The Phase Portrait Figure

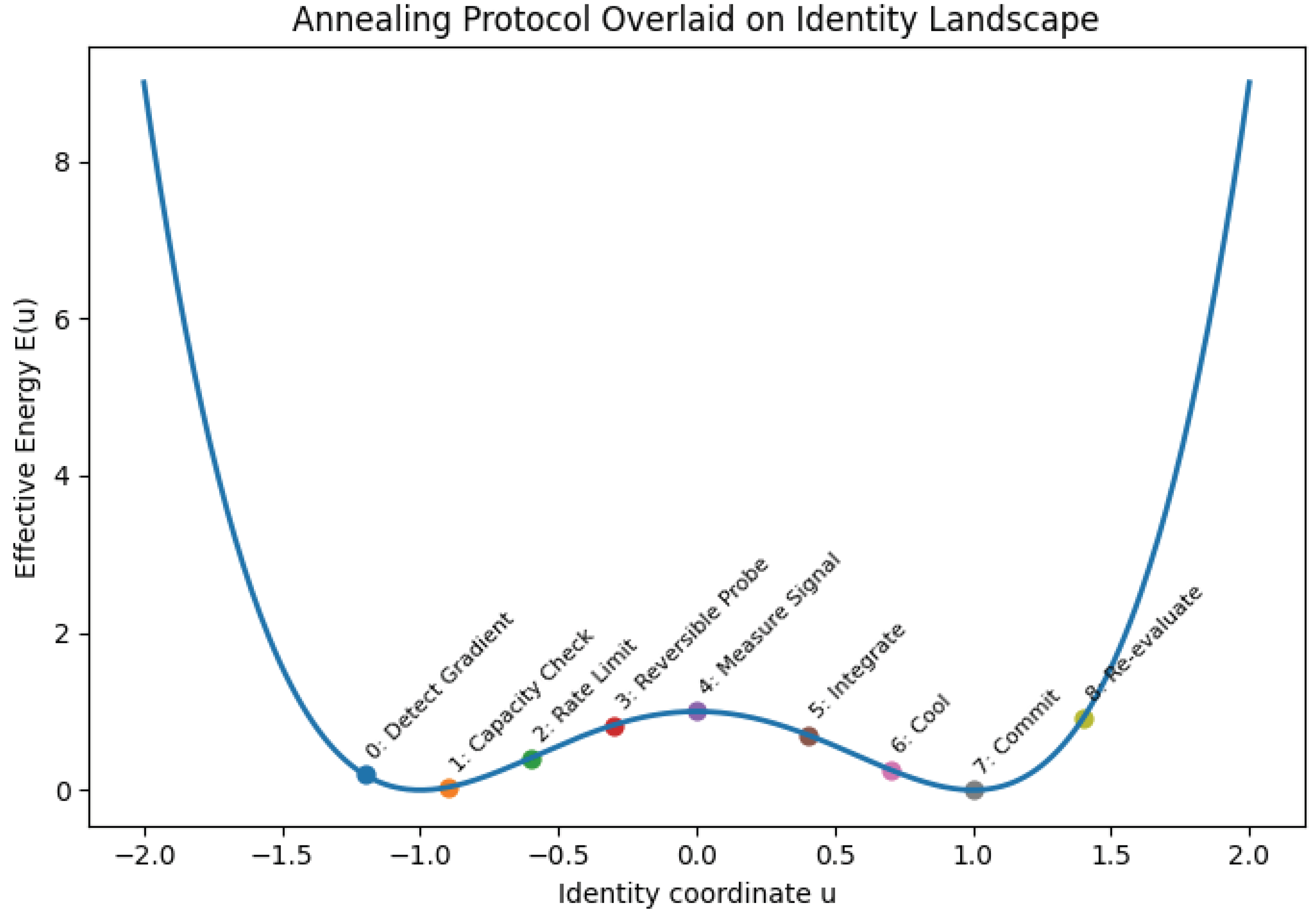

Figure 4 visualizes the reduced dynamics. The horizontal axis is identity (

u), the vertical axis is temperature (

T), and the shaded/annotated region indicates the

agency overload regime where

and updates become unreliable. The schematic trajectory illustrates premature cooling (drift toward low

T in the left basin), followed by AI-induced reheating (increased

T from steepened gradients), and then oscillation when reheating occurs under tight constraints and high rate.

This phase portrait is more than illustration: it provides an operational geometry for intervention. The decision protocol developed later will be derived from controlling and so that exploration remains possible without pushing the system into sustained overload (), enabling regulated entropy reduction rather than premature closure or fragmentation.

11. AI as a Gradient Multiplier in Professional Landscapes

The preceding sections establish a single structural claim: complex systems that cool early in buffered environments become brittle when gradients steepen, and agency collapses when the effective information rate exceeds integration capacity (). The AI age intensifies both mechanisms simultaneously. It steepens gradients in the environment and increases the rate at which actionable information arrives. This section formalizes these effects and explains why AI is not merely a new tool but a regime change in the annealing conditions of professional life.

11.1. Why AI Steepens Gradients

A gradient is any systematic pressure that changes the relative viability of states in the landscape. In the professional domain, the landscape is the set of roles, skills, reputations, and institutional niches that constitute employability and status. AI steepens gradients in at least three ways.

First, AI reduces the cost of producing high-quality cognitive outputs (drafts, code, analyses, summaries), compressing the advantage historically conferred by expertise and time. This changes the slope of the competitive landscape: what was previously scarce becomes abundant, and differences between agents are reweighted toward those who can define problems, validate outputs, and adapt quickly [

1,

36].

Second, AI accelerates task decomposition. Occupations persist, but the internal task composition shifts rapidly as specific tasks are automated, rearranged, or recombined [

1,

2]. From the perspective of the energy function, this means that the effective potential

becomes time-dependent and nonstationary: basins that were deep can become shallow, and barriers that maintained stability can erode.

Third, AI increases the rate at which new tools, workflows, and evaluation criteria appear. Even when an individual remains in the same occupation, the mapping from skill to value changes faster than traditional training pipelines can accommodate. This steepens the experienced gradient not only at moments of job displacement but continuously during ordinary work.

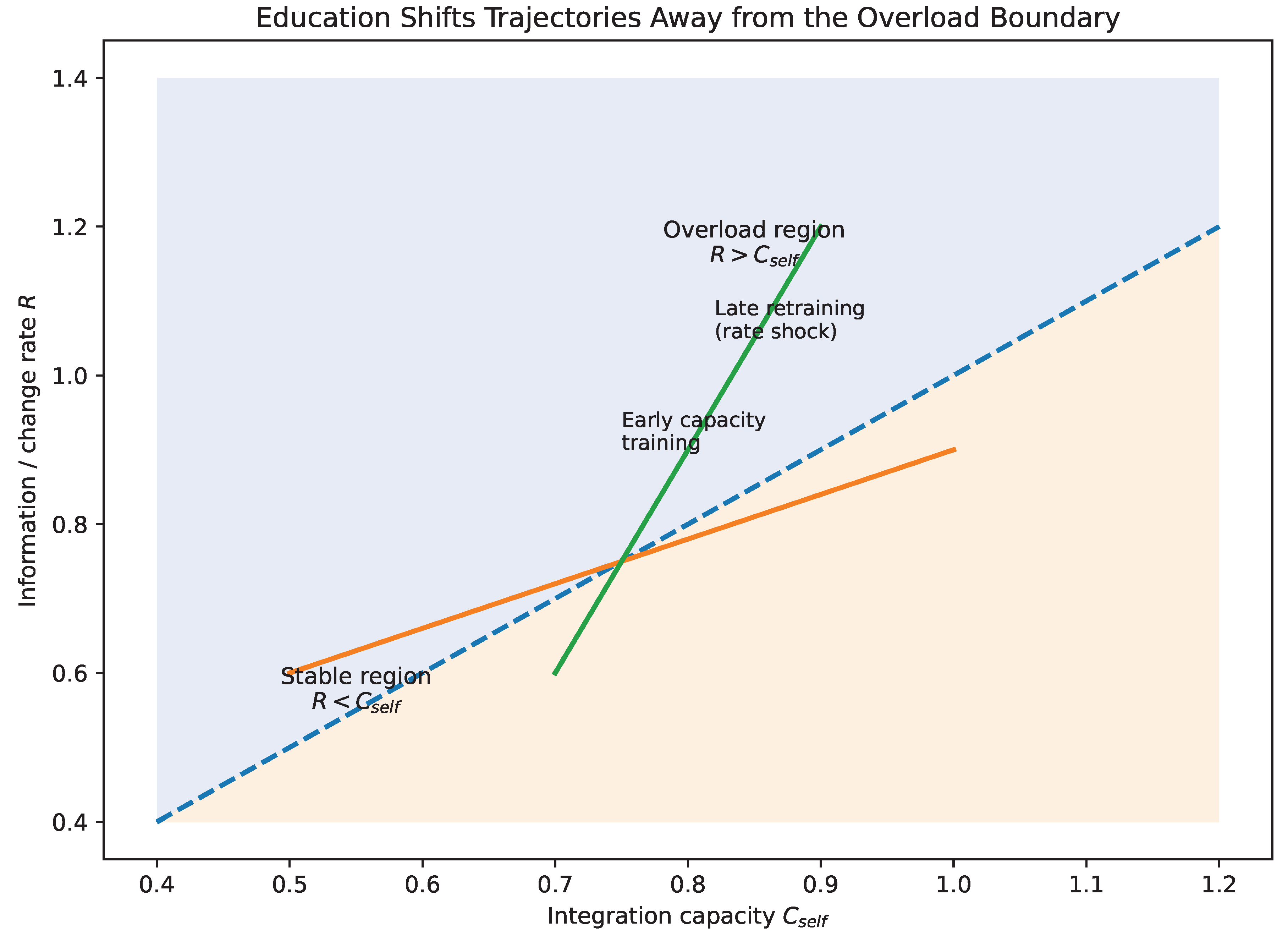

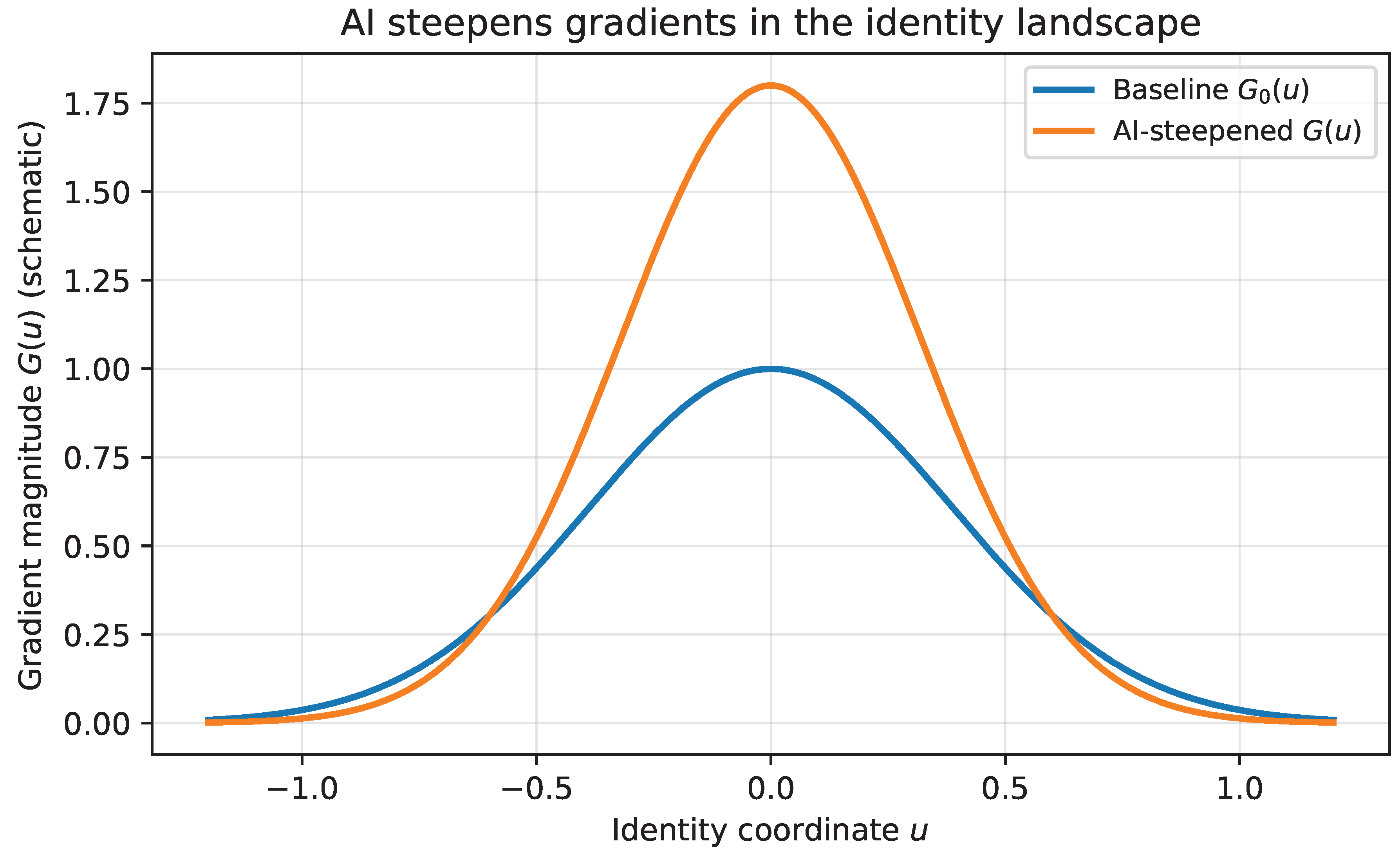

This effect is illustrated schematically in

Figure 5, where AI increases the effective gradient magnitude

and thereby raises the pressure to move across the landscape.

This mechanism is illustrated schematically in

Figure 5, where AI acts to amplify the effective gradient

, increasing the pressure on the system to move across identity and capability space.

11.2. AI Increases Effective Information Rate

Steep gradients are necessary but not sufficient for agency collapse. The second effect is a rate effect: AI increases the option velocity of the environment. Let denote the effective information rate an individual must integrate to remain adaptive. In AI-mediated settings, increases because:

the number of plausible actions expands (more options),

feedback loops tighten (faster updates),

social comparison accelerates (more visible counterfactuals),

and tool ecosystems churn (continuous onboarding).

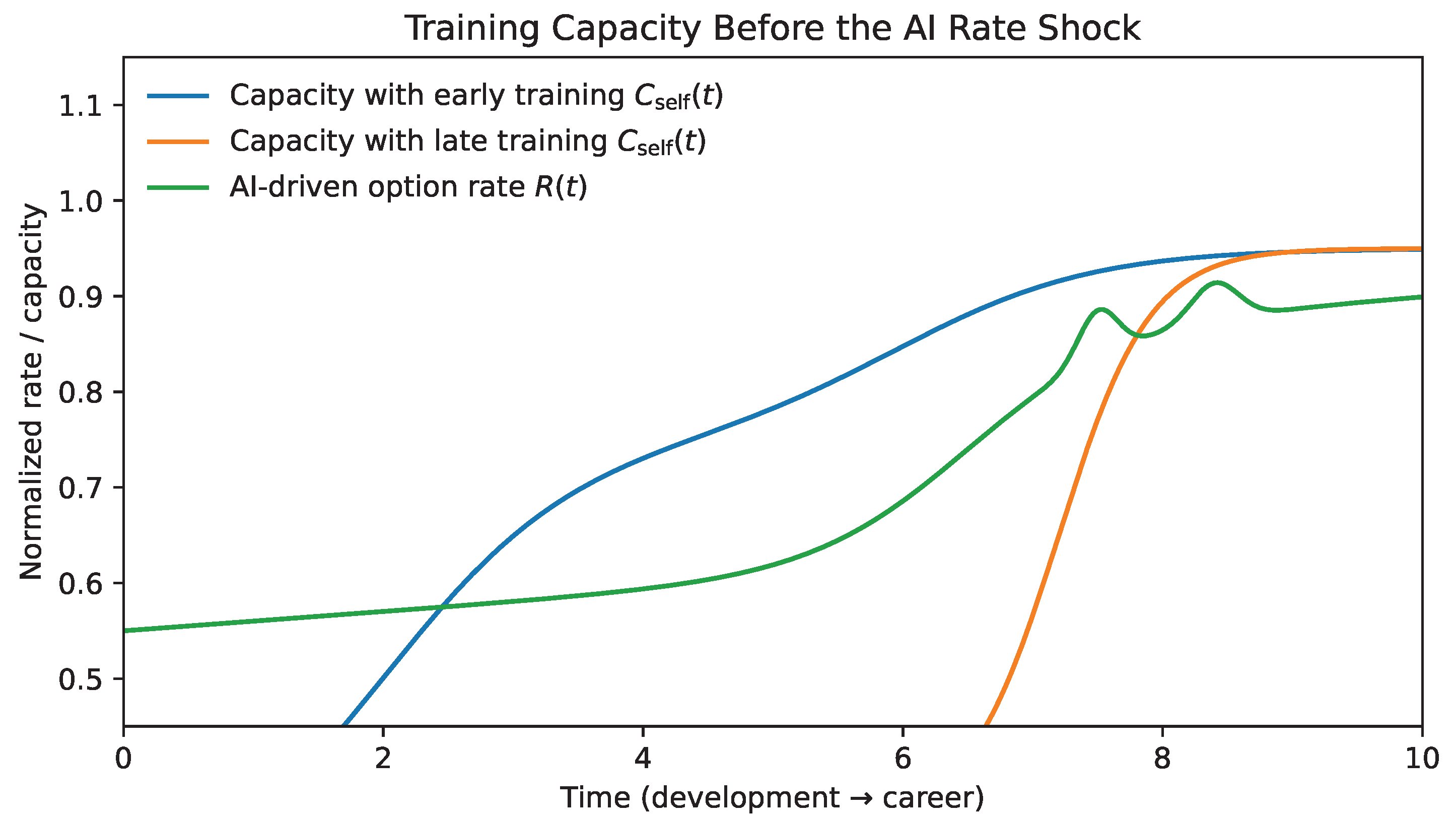

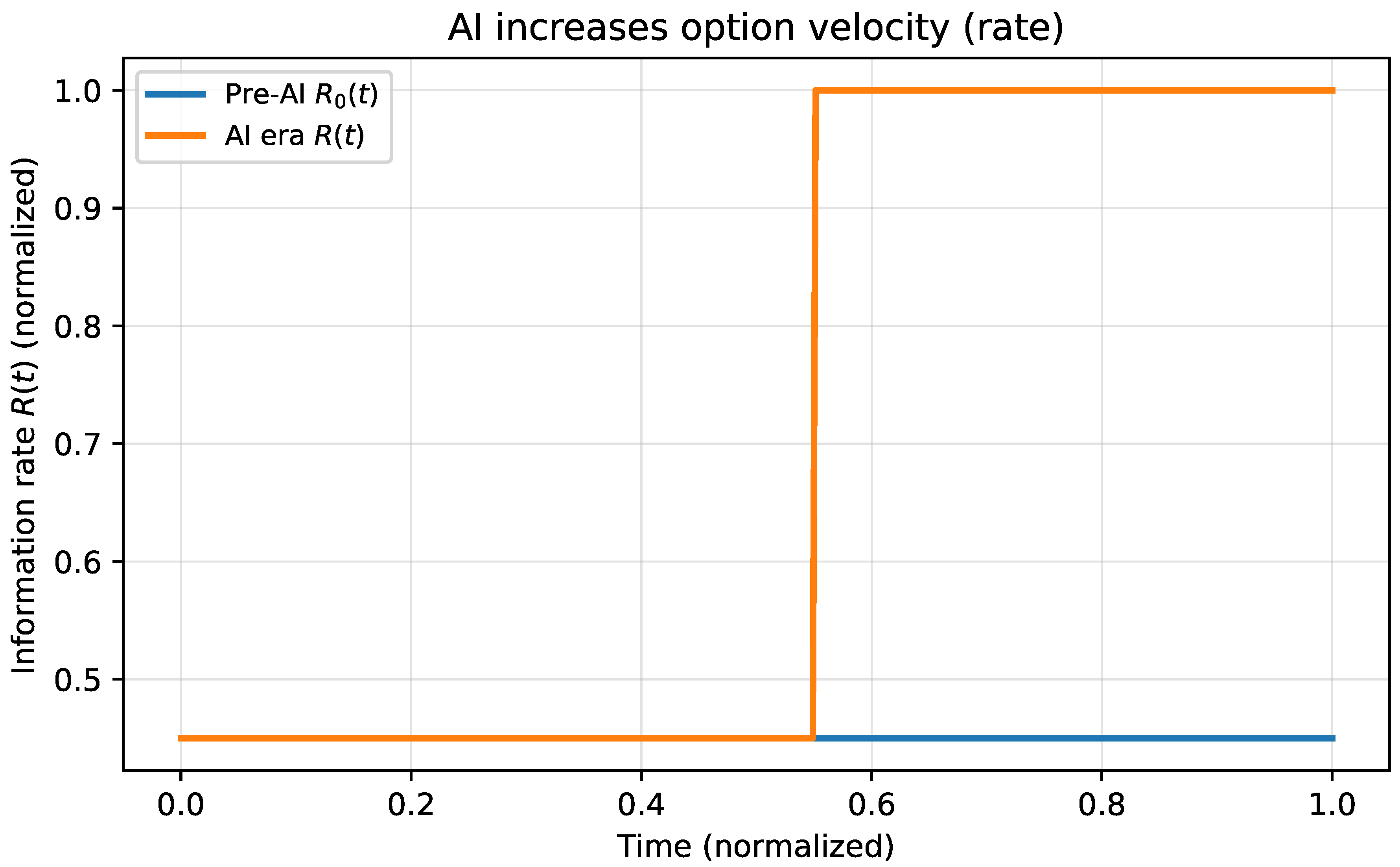

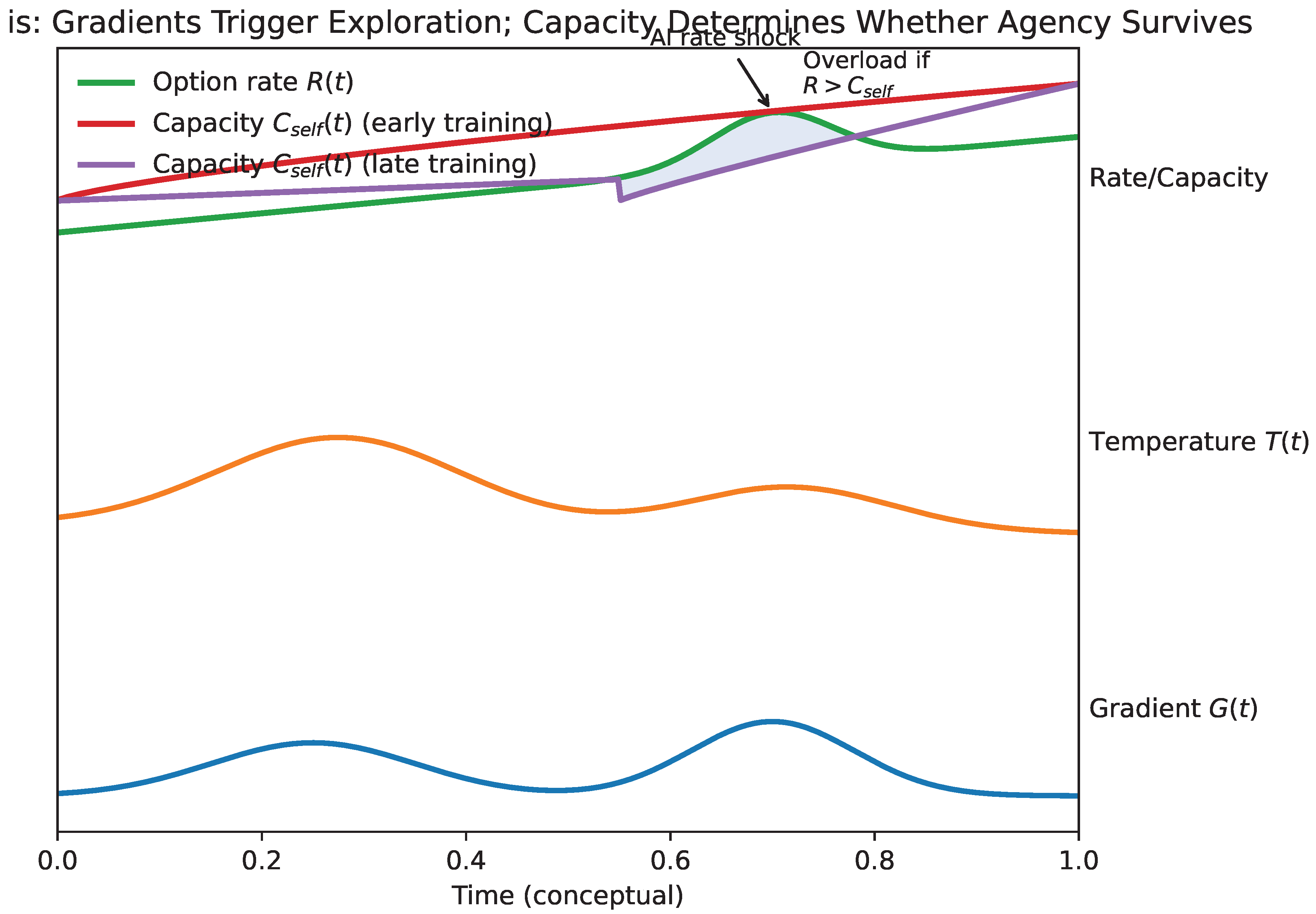

Figure 6 shows this rate effect schematically as a discontinuous increase in

(option velocity) under an AI-driven shock.

Figure 6 visualizes this effect as a sharp increase in the rate

induced by AI-mediated option proliferation.

Rate matters because integration is bounded.

Section 6 defined an integration capacity

(a channel-capacity analogue) and

Section 10 introduced the agency margin

. When

, additional information does not increase effective choice; it increases error. This reframes a central experience of modern professional life: overload is not a character flaw but a rate-limit violation.

11.3. A Minimal Coupling Model: AI as Gradient and Rate Amplifier

We can express AI as a multiplier on gradients and rates in the reduced phase portrait. Let

denote the intensity of AI-mediated change in the individual’s environment (tool adoption, organizational restructuring, market pressure). A minimal coupling is:

where

and

are baseline (pre-AI) gradient and rate, and

quantify AI-induced amplification. Substituting into the temperature dynamics and agency margin makes the mechanism explicit:

while agency becomes fragile when:

Equation (

32) captures a practical asymmetry:

can increase rapidly via external change, while

can increase only through training and time. This makes early-cooled systems vulnerable. When exploration was deferred for decades, the system has not practiced the transition dynamics required to keep

under shocks.

11.4. Why Job Loss Is a Special Case of the Same Mechanism

Job displacement is the most visible gradient encounter, but it is not the only one. It is best interpreted as a discontinuity in the landscape: a basin disappears or becomes inaccessible. In that case, both and spike, and the system must traverse state space under high irreversibility. This is the worst case for prematurely cooled identities, because exploration must be reintroduced late, when constraints are tight and errors are costly.

This is why professionals who appear safe and successful can be uniquely destabilized by AI change. When income is buffered, the dominant loss is agency and self-worth: the collapse of competence-signaling as the primary stabilizer of identity. The framework predicts this outcome directly, without assuming pathology.

11.5. Implication

AI changes the annealing conditions of professional life. It steepens gradients and increases rates. In such a regime, the central practical task is not accumulating more options but managing exploration so that it remains within capacity. The next section formalizes the failure mode: how information overload produces the collapse of agency and why “more willpower” is the wrong response.

When gradients steepen faster than the system’s capacity to integrate them, agency does not expand but collapses—a dynamic examined formally in

Section 12.

12. Information Overload and the Collapse of Agency

The AI age does not merely change what is possible; it changes the

rate at which possibility arrives. The preceding section formalized this as a rate amplification

and showed how rate interacts with exploration via the phase portrait in

Section 10. We now make explicit the central failure mode for human–AI systems:

agency collapses when the environment demands adaptation faster than the self can integrate. This section formalizes that failure mode and clarifies why “more willpower” is often counterproductive under overload.

12.1. Capacity as a Hard Constraint

Let

denote the effective information rate the individual must integrate to remain adaptive: tool churn, reskilling demands, option velocity, feedback loop speed, and organizational update rate. Let

denote the effective integration capacity of the self, introduced in

Section 6. The structural condition for reliable adaptation is:

When Equation (

33) is violated, behavior may remain energetic and even hyperactive, but it becomes poorly integrated. The system produces actions without consolidation. Decision making becomes noisy. Commitments are made impulsively and then reversed. Alternatively, the system freezes, experiencing a subjective paralysis: many options are visible but none can be stably selected.

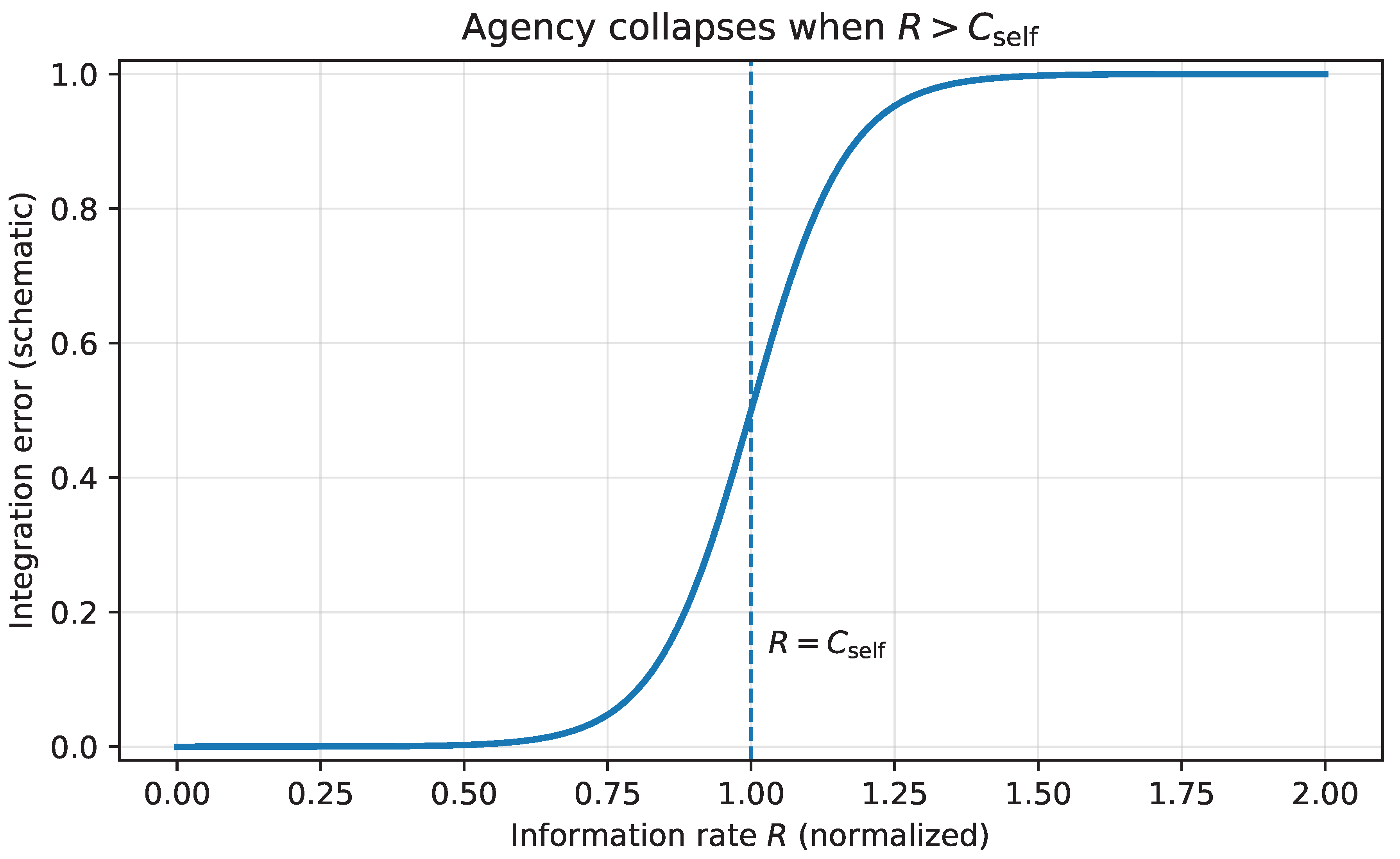

This transition is illustrated schematically in

Figure 7. As the incoming rate

R approaches capacity, performance degrades smoothly. Once

R exceeds

, error grows superlinearly. Beyond this threshold, additional effort cannot restore agency; it only amplifies noise and fragmentation.

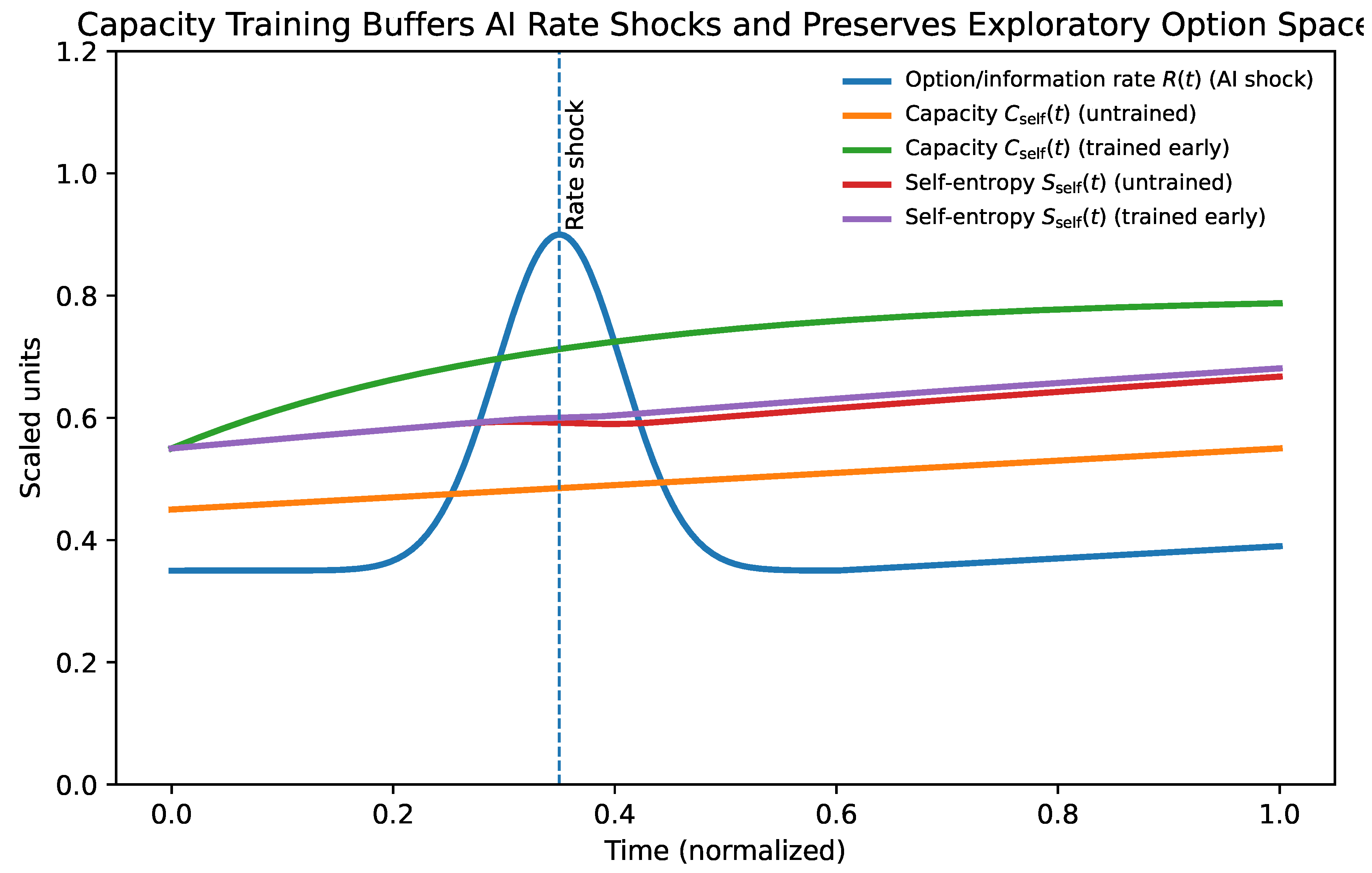

Figure 8 contrasts two trajectories under an identical external rate shock. In the untrained system, capacity is exceeded immediately, leading to collapse. In the trained system, prior exposure to manageable gradients has expanded

, allowing the same shock to be integrated without loss of coherence.

To express this compactly we reuse the agency margin from

Section 10:

Agency is robust when and degrades when .

12.2. Why Overload Increases Error Rather than Freedom

A common intuition is that more options increase freedom. Under capacity constraints the opposite can occur. When rises, an individual can attempt to “keep up” by increasing effort. However, effort does not increase capacity instantaneously. In rate-limited regimes, pushing more information through a fixed channel increases error. The practical signature is not ignorance but mis-integration: learning fragments into uncoordinated pieces, and choices cannot be maintained long enough to yield evidence.

This mechanism explains a characteristic pattern in AI-mediated work. Generative systems increase the number of plausible next actions and accelerate iteration. If the human attempt to evaluate all outputs, track all options, and respond to all signals, can exceed even when the human is competent. The result is a paradoxical reduction of agency: the system sees more but chooses less.

12.3. Overload Couples Back into the Energy Landscape

Overload is not only a rate issue; it reshapes the experienced landscape

. When

, exploration becomes costly. Errors accumulate. Confidence degrades. The subjective cost of change rises, and the system is pulled toward premature closure as a defense. A minimal way to express this feedback is an agency penalty term:

where

is increasing for

(e.g.,

) and

sets the strength of the overload penalty. In words: when the world is arriving too fast, every move feels more expensive.

This feedback produces two common failure modes that can be misread as personality.

Premature freezing: the system drives to reduce decision load, collapsing self-entropy rapidly into an available “safe” basin. This may restore short-term stability while increasing long-term brittleness.

Unstable reheating: the system remains hot because gradients are steep, but cannot cool into a stable basin because integration is failing. The result is oscillation: activity without settlement.

Both are predictable consequences of Equation (

33); neither requires a moral explanation.

12.4. Capacity Can Be Trained, but Not Instantly

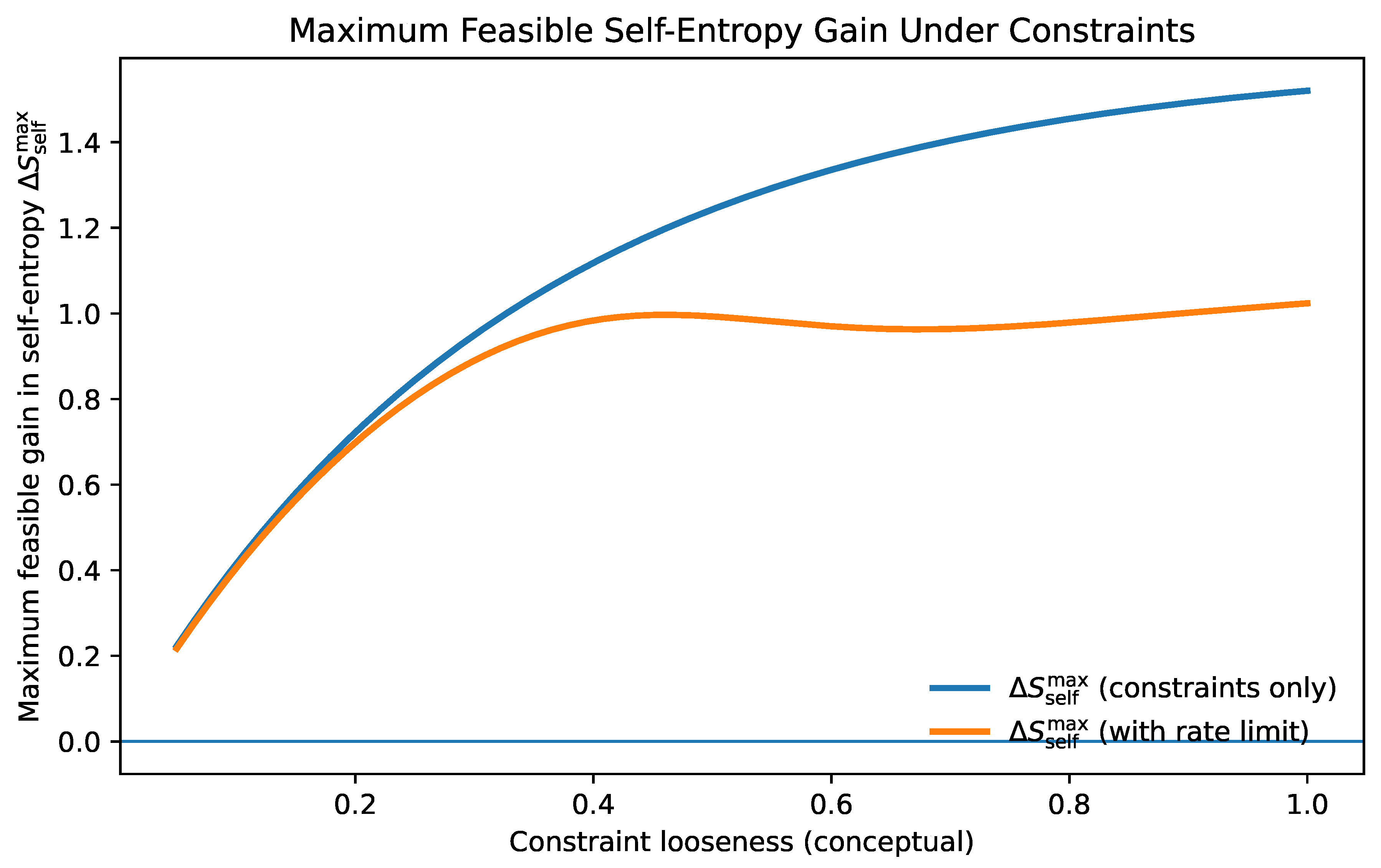

A central implication follows. Capacity is plastic over long time scales but constrained over short ones. Increases in require repeated practice of integration under bounded load: learning-to-learn, tool onboarding, and the deliberate rehearsal of transitions. This is why the timing matters. If exploration and reskilling are deferred until the AI gradient arrives, can jump faster than can grow, making collapse likely. Conversely, systems that maintain non-zero exploration under low stakes gradually expand capacity and can absorb higher later.

This observation reframes a basic claim about education and professional development. Training is not only the acquisition of content; it is the expansion of integration capacity and the acquisition of rate management skills (how to reduce by selecting, batching, and constraining inputs). This will be returned to explicitly in the decision protocol.

12.5. Implication for Intervention

The immediate intervention target under overload is not motivation but rate control. When , the system must reduce (triage, constraints, batching, deliberate narrowing) and/or temporarily increase effective capacity (sleep, recovery, social support, scaffolding) before attempting high-stakes exploration. Without this step, advice to “explore more” is destabilizing: it increases further and deepens overload.

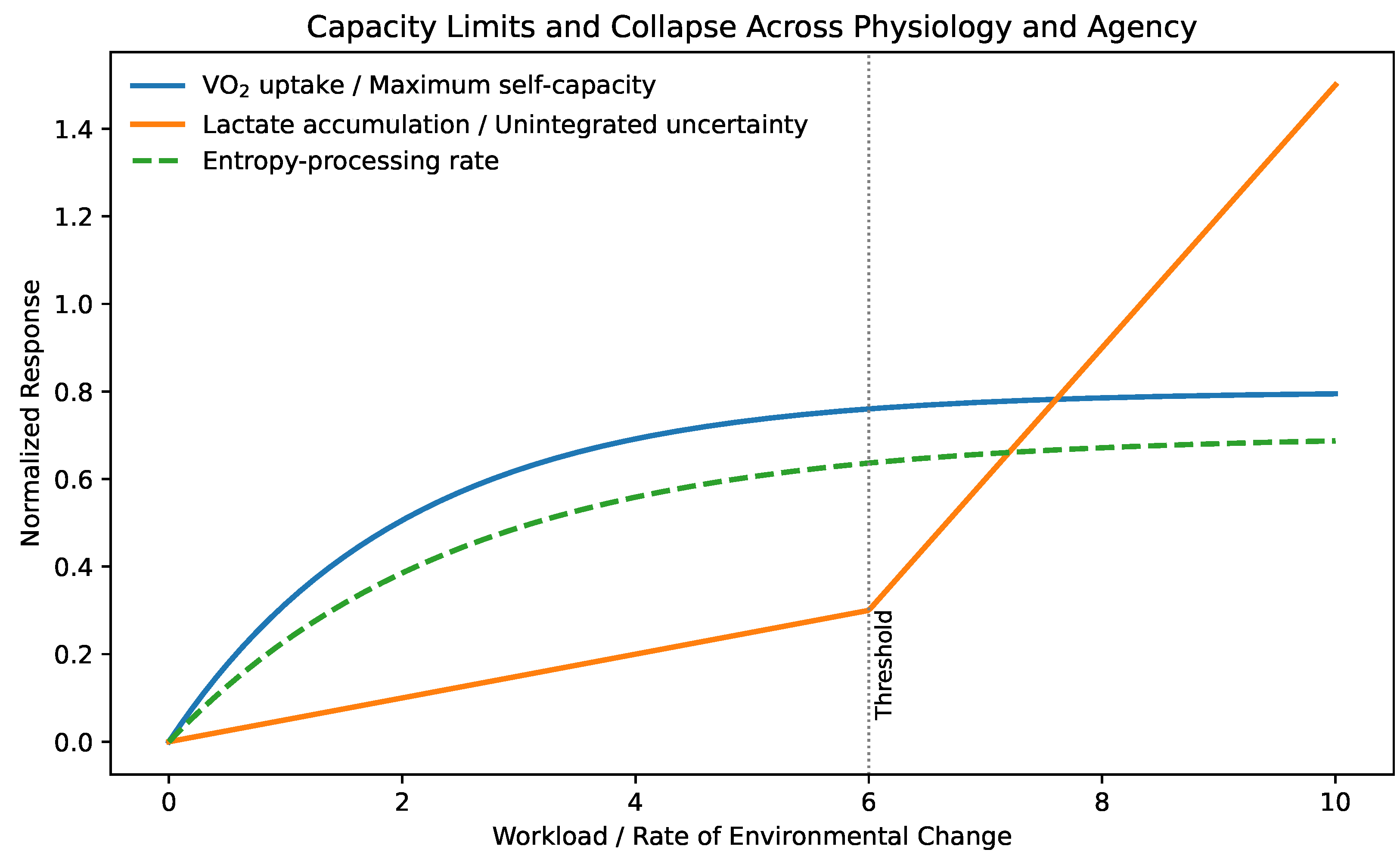

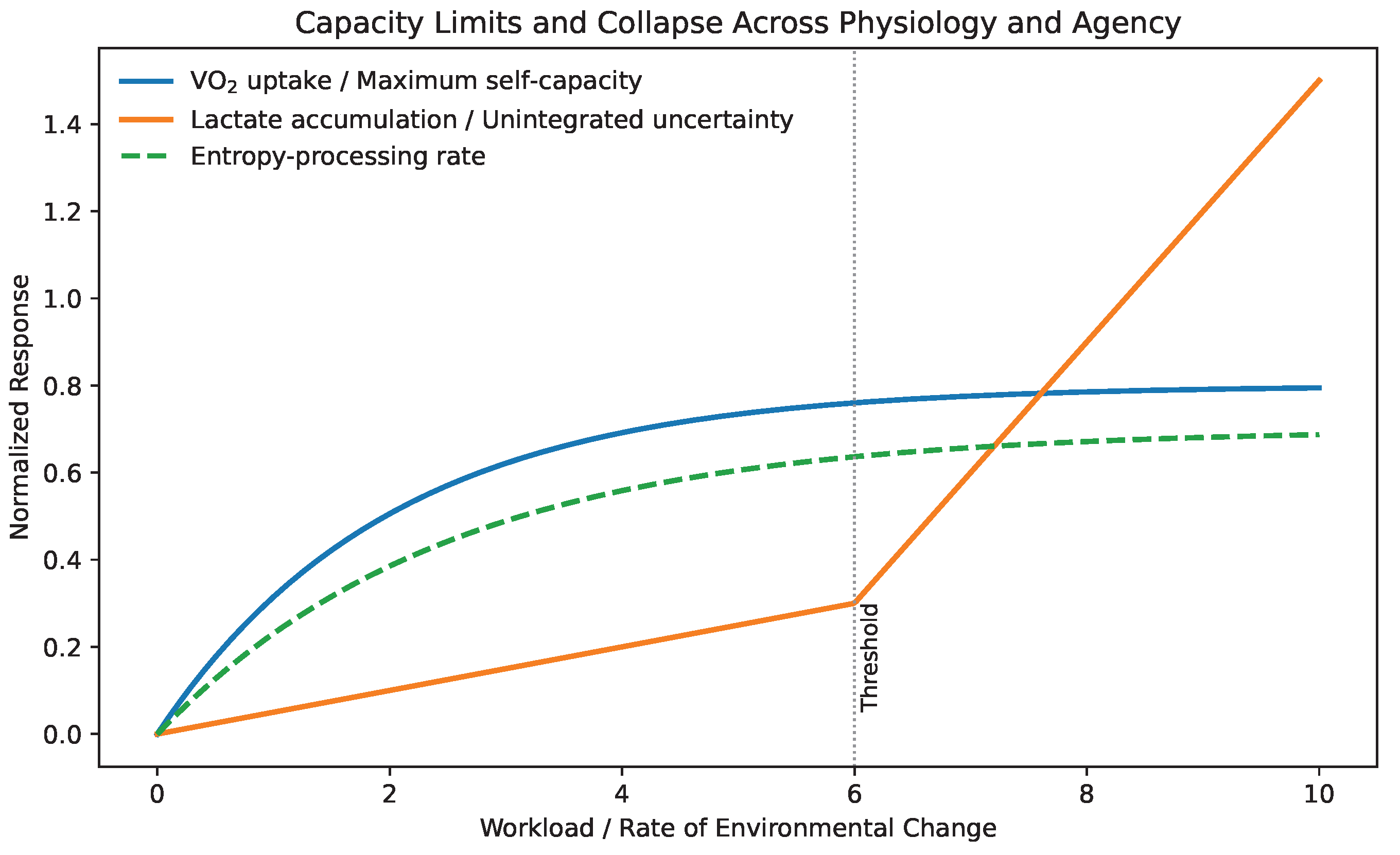

12.6. Capacity as a Physiological Analogue: VO2max Lactate Threshold, and Entropy Rate

In human physiology, maximal oxygen uptake (

max) is widely regarded as one of the strongest integrative indicators of health, resilience, and longevity, as it reflects the upper bound on sustainable metabolic energy production under load [

37,

38]. Crucially,

max does not describe typical performance, but rather the maximum rate at which energy can be mobilized when required.

We argue that an analogous quantity exists for adaptive cognition and agency: a self-capacity , representing the maximum sustainable rate at which an individual can absorb novelty, update internal models, and reorganize identity under changing conditions. As with max, this capacity is shaped jointly by genetics, developmental history, training, and environment, and it is not directly observable through behavior alone.

Physiology further distinguishes between absolute capacity and

thresholds. In endurance sports, the lactate threshold marks the transition beyond which metabolic demand exceeds clearance capacity, leading to rapid fatigue and loss of performance [

39]. Operating persistently above this threshold results in accumulation rather than integration.

The same distinction applies to adaptive systems. When the externally imposed rate of change exceeds an individual’s effective capacity , unintegrated informational load accumulates. In the present framework, this manifests as entropy accumulation without consolidation, producing stress, indecision, identity fragmentation, or collapse of agency. Below this threshold, exploration remains metabolizable; above it, adaptation degrades.

Figure 9 illustrates this analogy explicitly, mapping physiological capacity and thresholds onto cognitive–existential dynamics. Capacity determines what is possible; thresholds determine what is sustainable.

This distinction has immediate implications for the AI age. Artificial intelligence increases the rate of environmental change without regard for individual capacity. Systems optimized solely for efficiency or output risk pushing humans chronically above their adaptive threshold. Preserving agency therefore requires active regulation of rate, not merely expansion of choice.

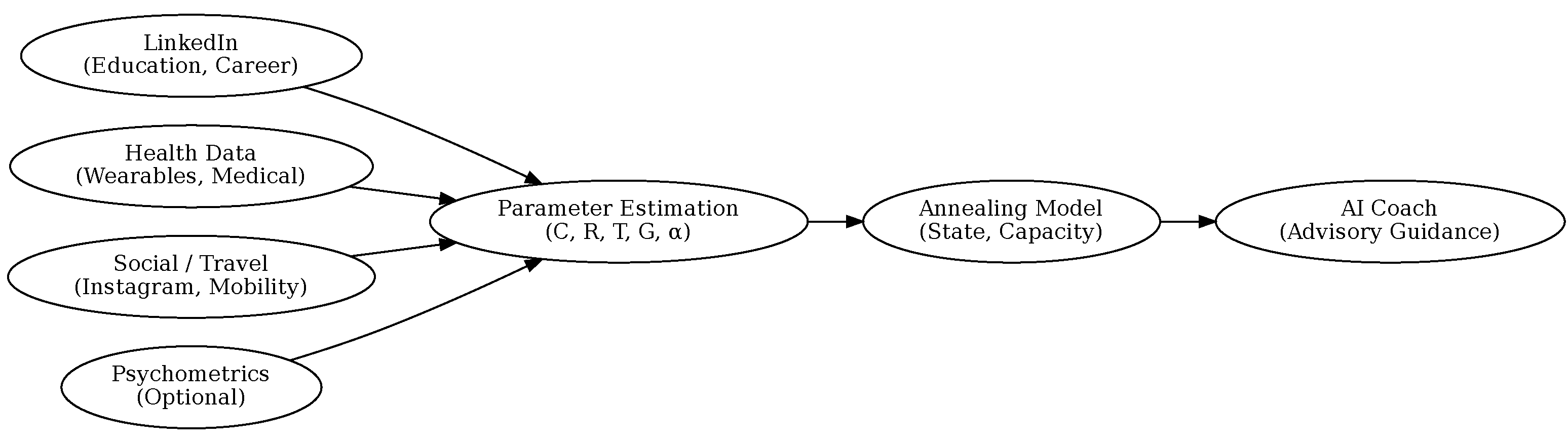

Operationally, while max can be measured through graded exercise testing, must be inferred indirectly. In Appendix H, we outline a protocol for estimating adaptive capacity using longitudinal multimodal data, including wearable physiology, cognitive load proxies, work-pattern variability, and recovery dynamics. This enables capacity-aware guidance analogous to modern endurance training, where load is modulated relative to physiological thresholds rather than absolute demand.

Table 1 highlights a close structural analogy between well-established concepts in exercise physiology and the dynamics of self-capacity introduced here. In physiology,

max provides a robust, integrative measure of an individual’s maximal aerobic capacity and is among the strongest predictors of long-term health and mortality. Analogously, maximum self-capacity characterizes the upper bound on the rate at which an individual can process uncertainty, novelty, and adaptive demands without loss of coherence.

The lactate threshold is particularly instructive. Below this threshold, metabolic byproducts are cleared and integrated; above it, lactate accumulates and performance degrades despite adequate raw capacity. In the present framework, this corresponds to a sustainable entropy-processing rate. When environmental or informational change exceeds this rate, unintegrated uncertainty accumulates, eventually producing agency collapse. Importantly, failure arises not from insufficient capacity per se, but from a mismatch between imposed rate and adaptive bandwidth.

This analogy clarifies why resilience depends critically on pacing. Just as physiological capacity is expanded through controlled threshold training rather than maximal exertion, self-capacity is increased through regulated exploration and gradual reheating. Conversely, sustained overload leads to burnout or premature cooling, mirroring the effects of overtraining in biological systems.

In the next section, we translate these constraints into an explicit optimality criterion that avoids subjective collapse and then derive a practical annealing protocol for AI-assisted decision making.

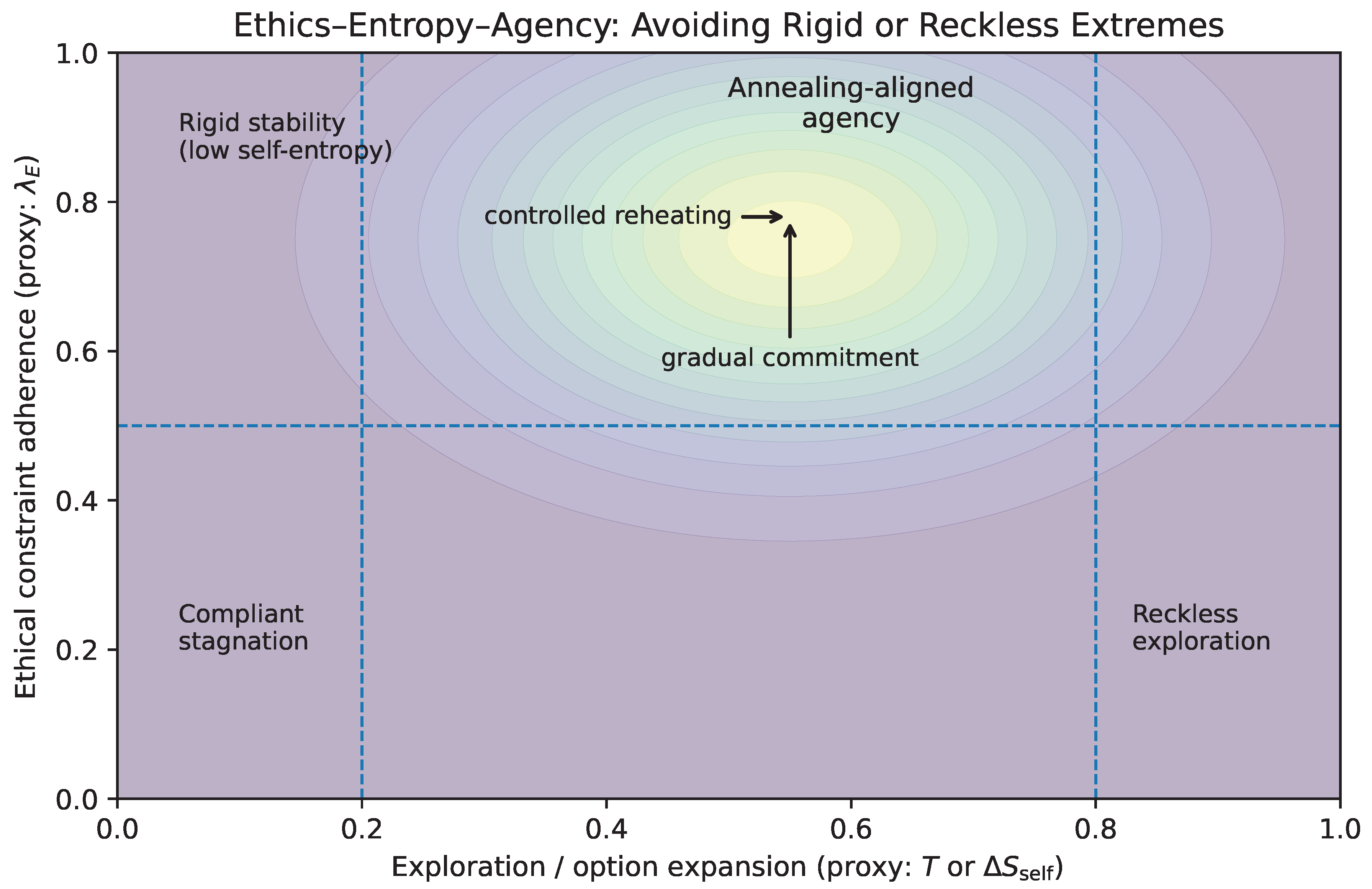

13. What Should We Optimize For?

Section 11 and

Section 12 establish a constraint-driven diagnosis: AI steepens gradients and increases the effective information rate

, while the self has finite integration capacity

. When

, agency collapses. The remaining question is normative but can be stated structurally:

what objective function can be defended without collapsing into subjective targets (e.g., happiness, certainty, success), yet remains actionable under capacity constraints?

13.1. Why Naive Objectives Fail Under Gradients

Classical “blueprint” objectives implicitly assume a stationary landscape: pick a target (career identity, lifestyle, value set), then optimize toward it. In nonstationary, gradient-driven environments, this approach is brittle for two reasons. First, the energy landscape

moves: what is locally optimal today may become unstable tomorrow. Second, the process is capacity-limited: even if a target were well-defined, the rate at which the target must be revised may exceed

, producing error and fragmentation instead of control (

Section 12).

The annealing framework suggests that the correct objective is not a final state, but a property of the process that keeps a system viable under change.

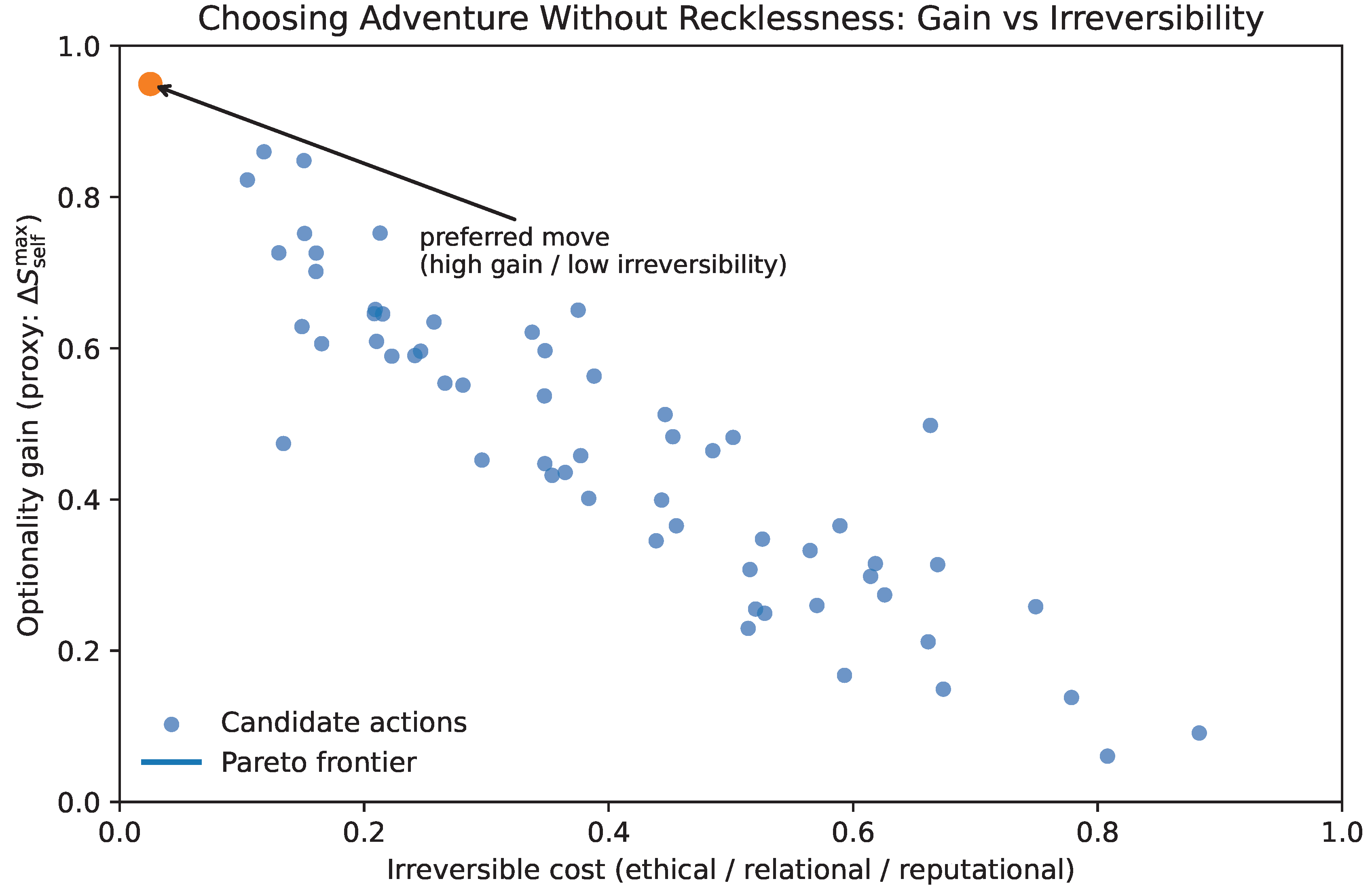

13.2. A Structural Objective: Preserve Future Feasibility of Controlled Annealing

Recall the unified dynamics (

Section 7), in which adaptation requires both (i) exploration (stochastic sampling) and (ii) stabilization (cooling/commitment). The failure modes are: premature cooling (brittle local minima) and perpetual reheating (fragmentation). A defensible objective should therefore reward neither maximal exploration nor maximal stability, but the ability to

regulate the transition between them.

We formalize this as the preservation of future feasibility of controlled annealing. Informally: the system should act so that, at future times, it can still (a) explore when needed, (b) commit when appropriate, and (c) remain within capacity constraints.

One convenient way to express this is as a margin condition:

where

indicates that the system can integrate the rate of change without losing coherence, and

indicates overload. A structural optimization criterion is then:

where

is a discount/priority weight and

is a planning horizon. This objective does not specify what to value. Instead, it preserves the precondition for coherent valuation under change: continued agency.

13.3. Meaning as Regulated Reduction, Not Maximization

The framework developed here supports a precise claim that is often misunderstood: meaning does not arise from maximizing self-entropy nor from minimizing it, but from its regulated reduction under constraint. Exploration increases accessible possibility; stabilization compresses possibility into commitment. Meaning is the subjective signature of committing after sufficient sampling, and then bearing the irreversibility of the commitment.

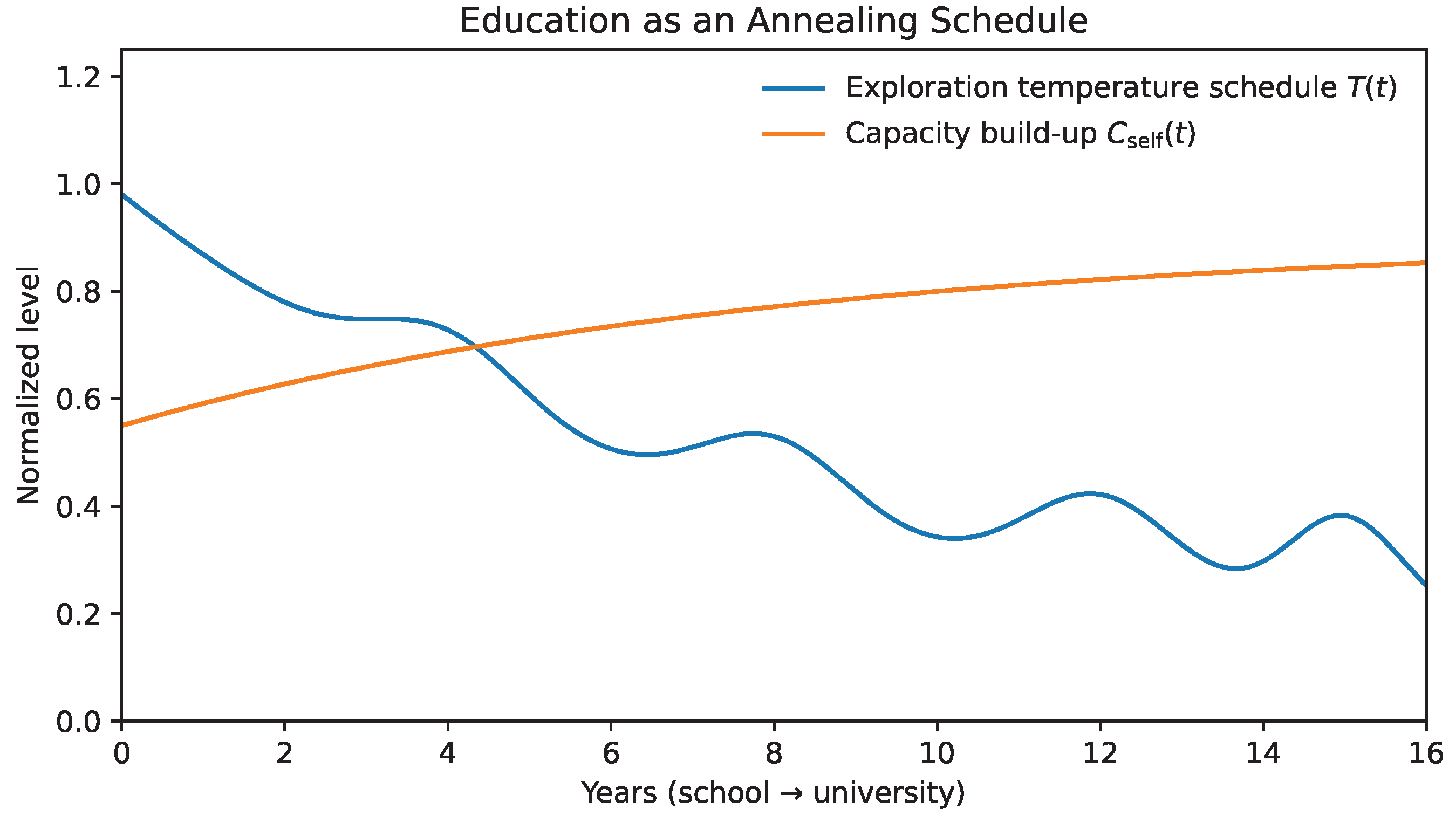

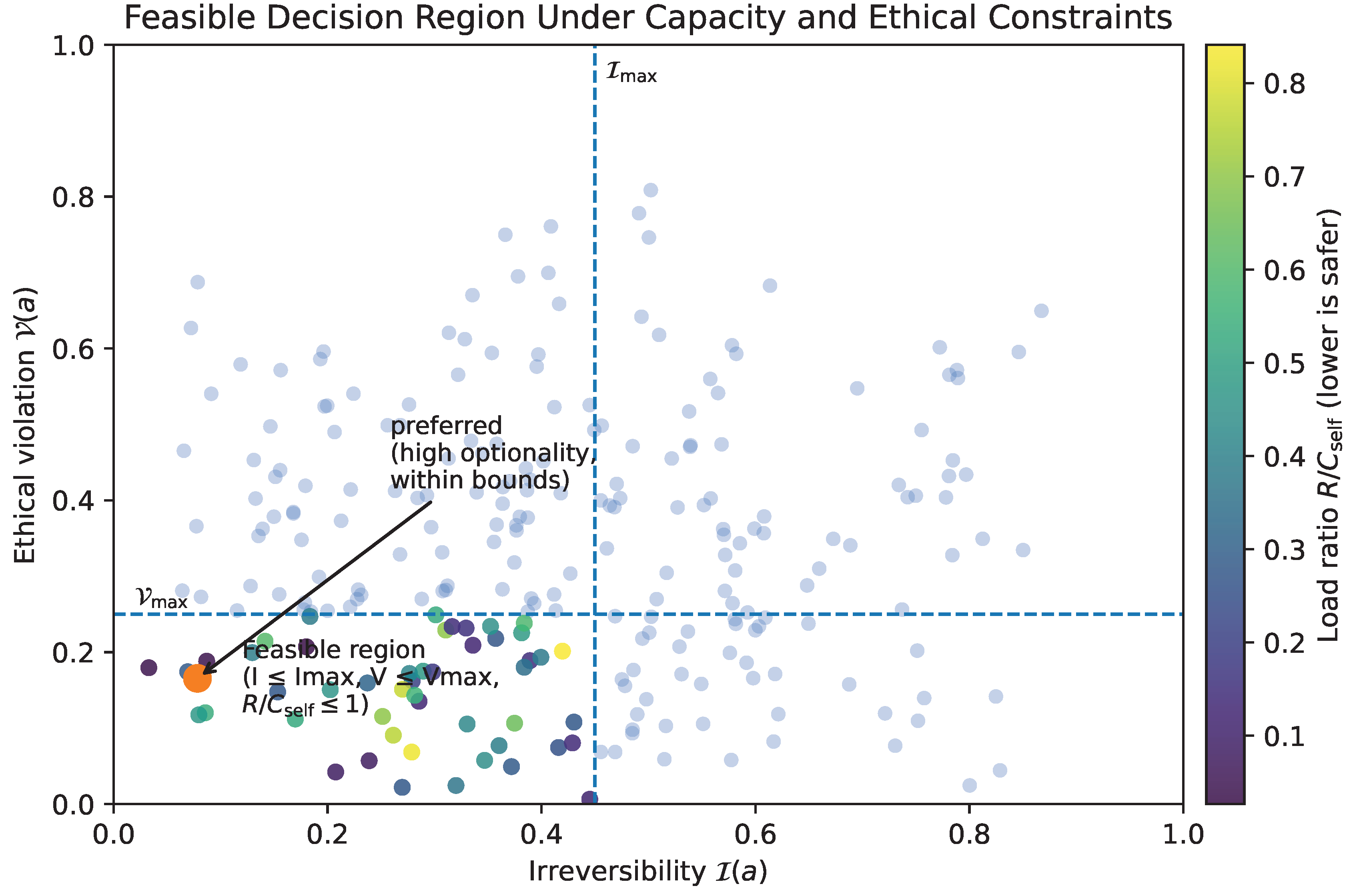

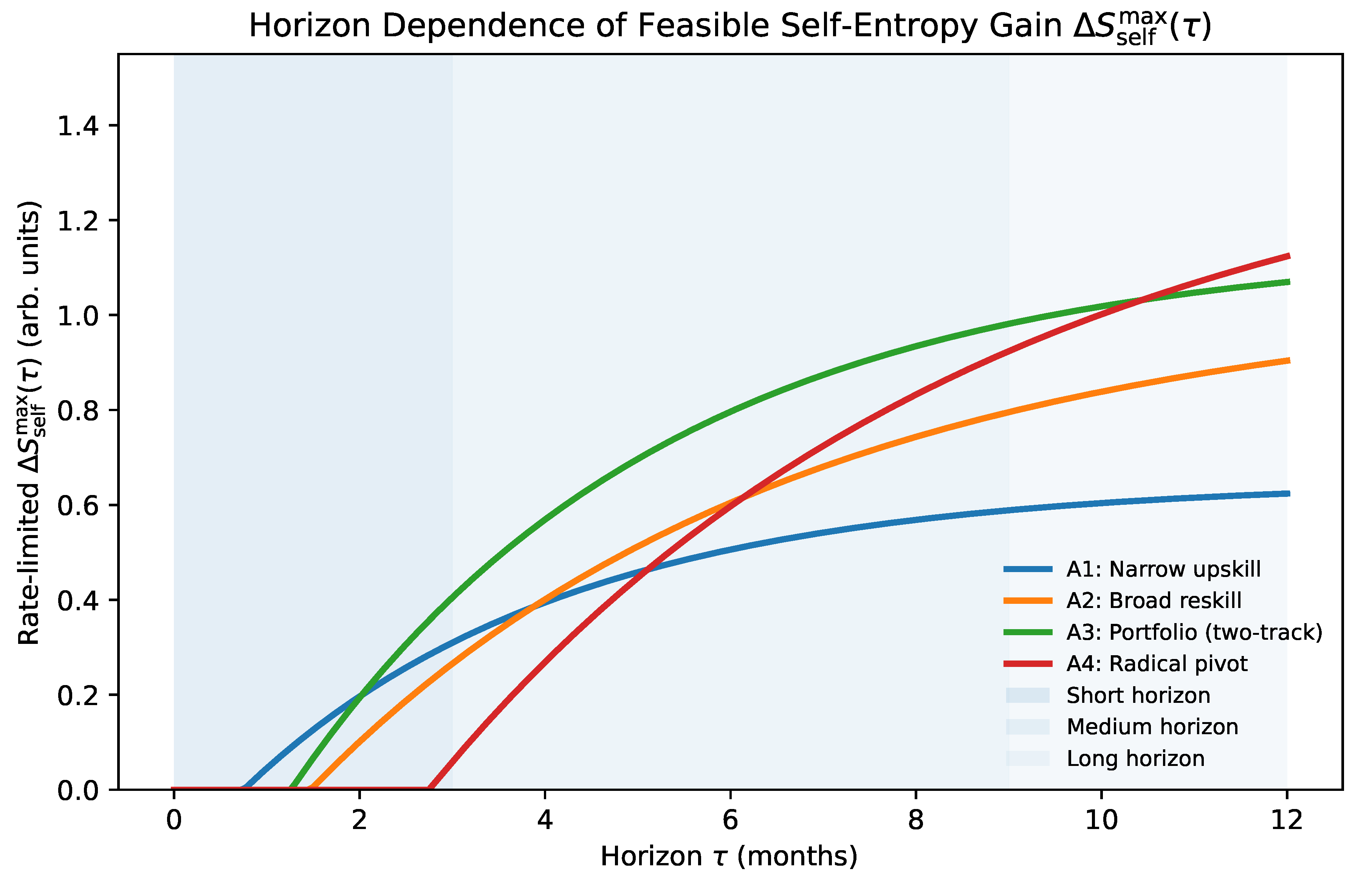

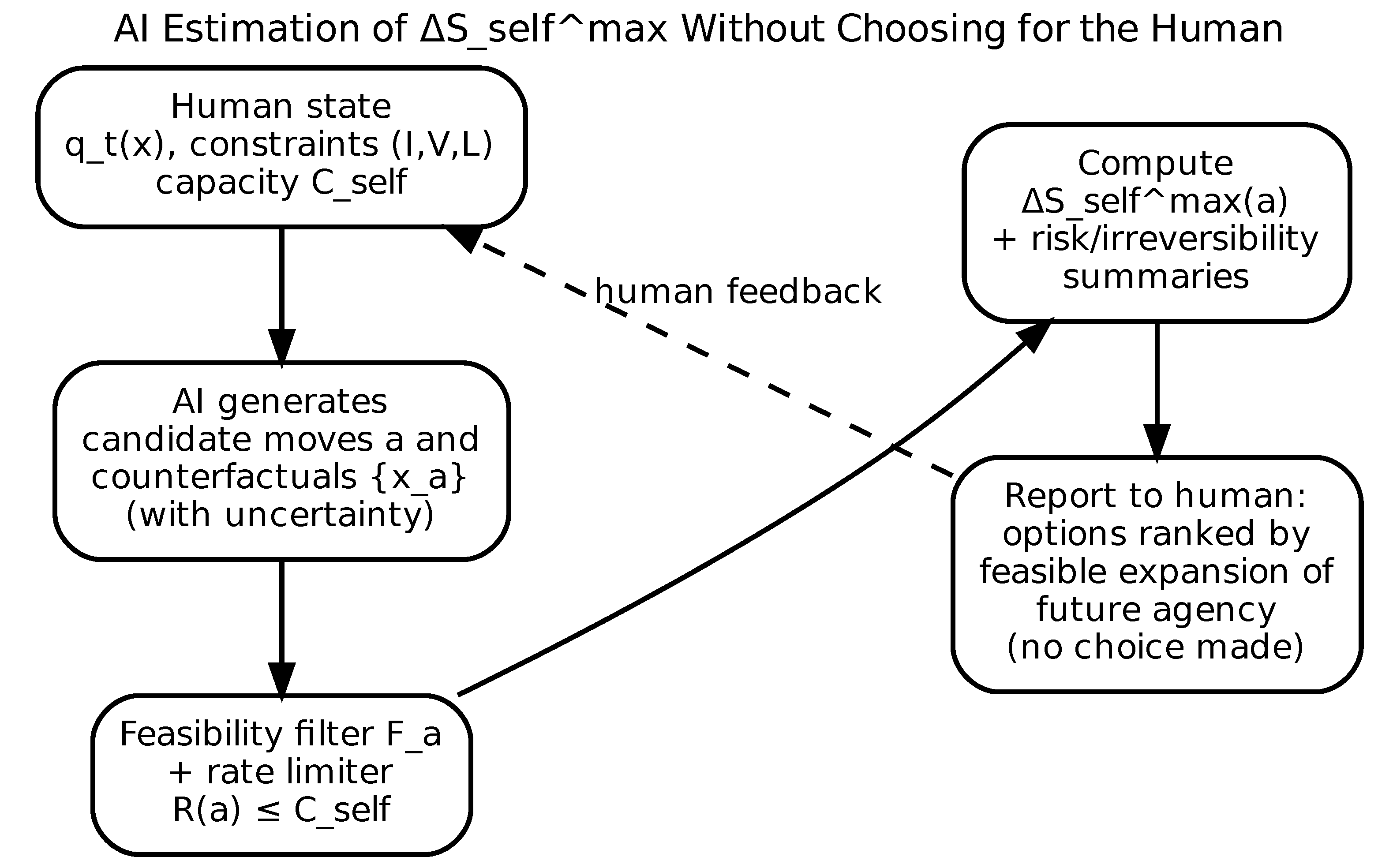

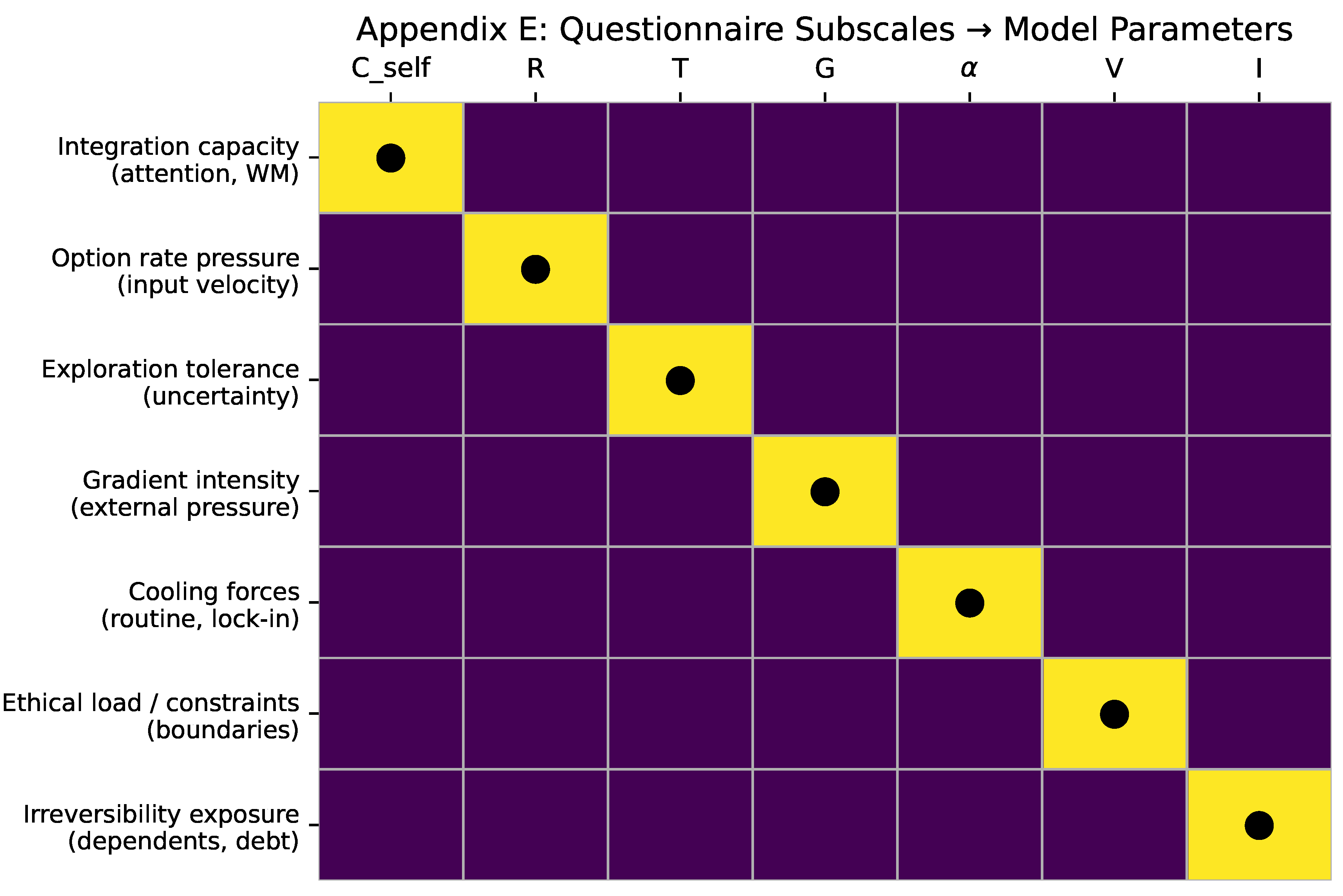

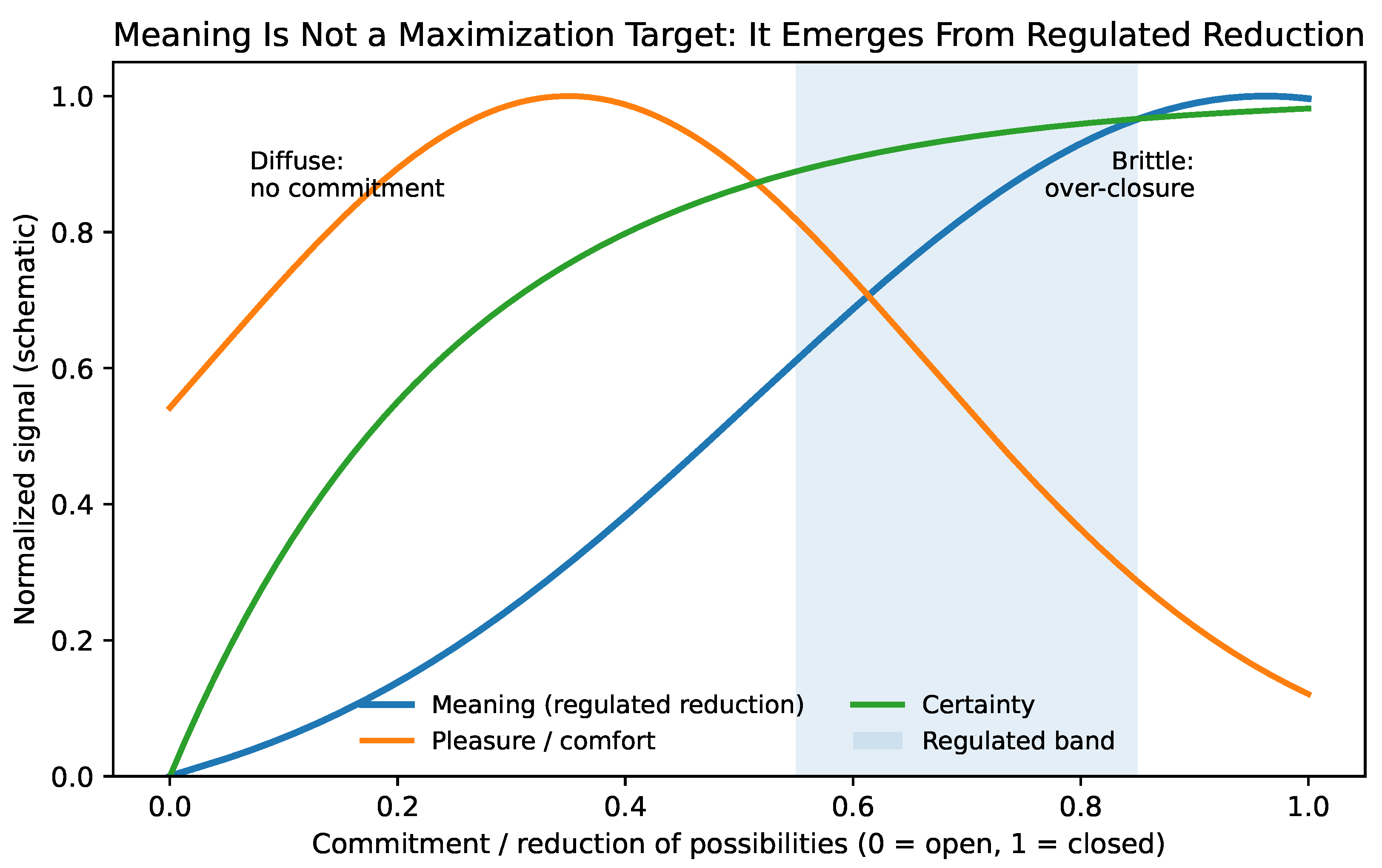

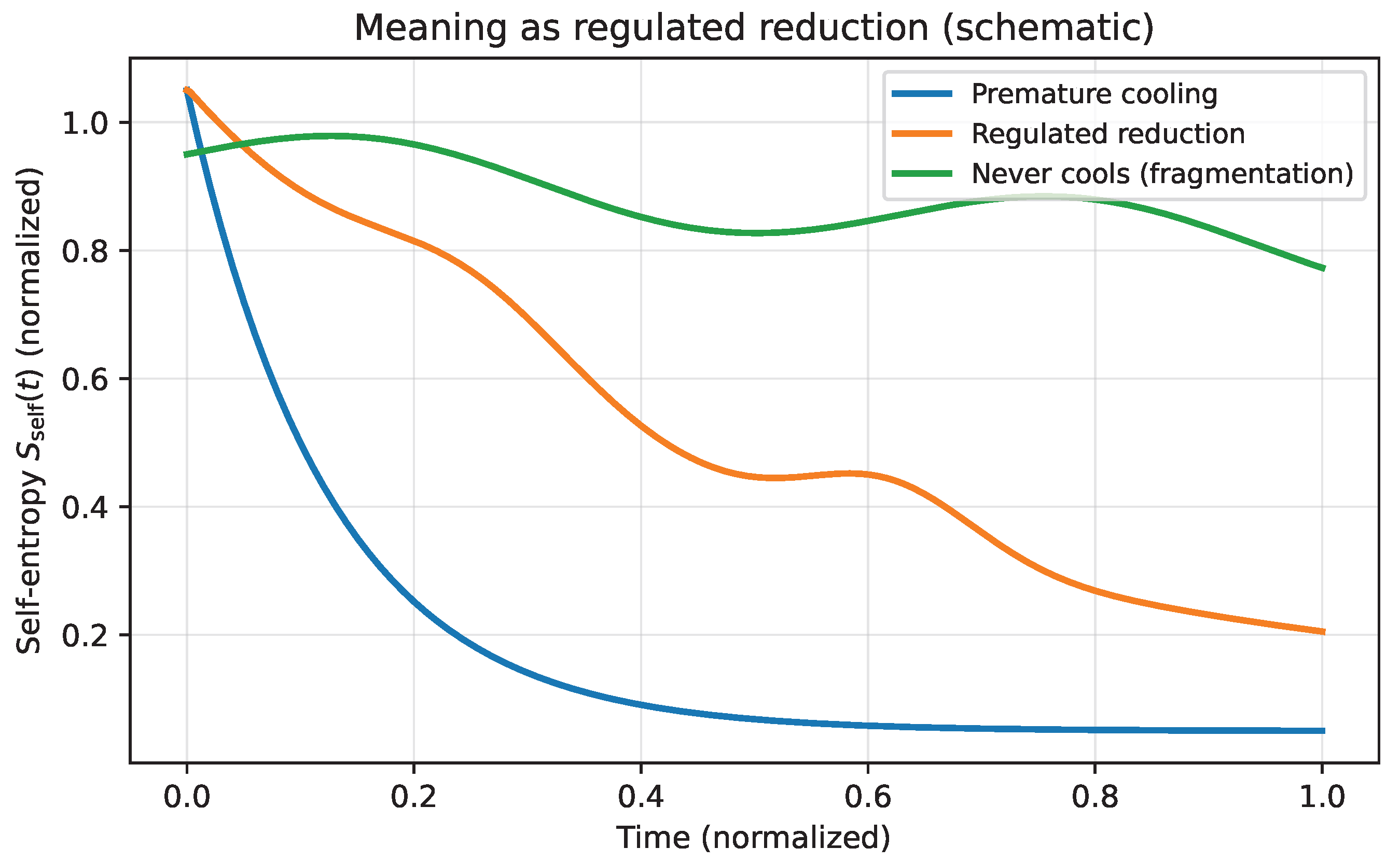

Figure 10 illustrates three schematic regimes in terms of