1. Introduction

Vision–language–action (VLA) models [

1] have recently emerged as a powerful paradigm for robotic manipulation, enabling end-to-end mappings from raw visual observations and natural-language instructions to low-level motor commands. By leveraging large-scale vision–language models (VLMs) [

2] pre-trained on extensive web data, VLA systems exhibit strong semantic understanding and instruction-following capabilities. From a structural perspective, such models implicitly aim to learn representations that are invariant to task-irrelevant transformations, such as changes in viewpoint, lighting, or object appearance. However, despite internet-scale pretraining, existing VLA models often fail to preserve these desirable invariances in practice, leading to brittle behavior under unfamiliar lighting conditions [

3], novel objects [

4], and visual distractors [

5], as well as limited generalization to out-of-distribution tasks [

6].

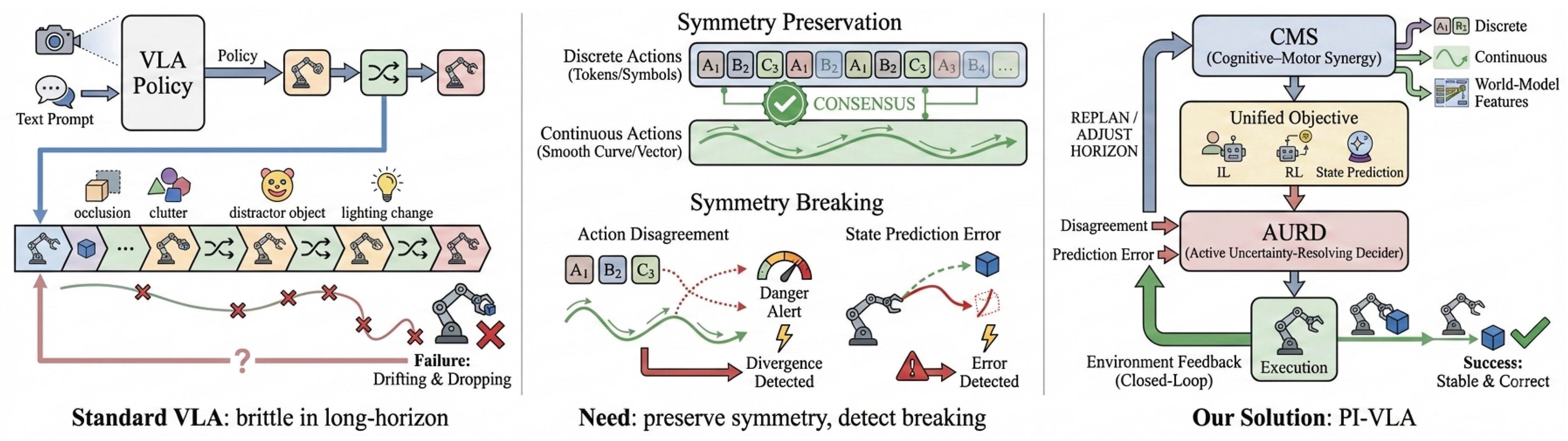

Figure 1.

Motivation. Standard VLA policies are brittle in long-horizon manipulation due to error accumulation and delayed failures. We observe that robustness hinges on preserving action–state symmetry while explicitly detecting and resolving symmetry breaking. PI-VLA addresses this via predictive modeling and interactive replanning.

Figure 1.

Motivation. Standard VLA policies are brittle in long-horizon manipulation due to error accumulation and delayed failures. We observe that robustness hinges on preserving action–state symmetry while explicitly detecting and resolving symmetry breaking. PI-VLA addresses this via predictive modeling and interactive replanning.

Beyond algorithmic challenges, the deployment of VLA models is further constrained by hardware asymmetries. State-of-the-art robotic manipulators typically rely on high-precision actuators and custom components, resulting in system costs of several thousand dollars [

7]. This hardware asymmetry—where advanced learning algorithms are coupled with expensive and specialized platforms—significantly limits accessibility. Moreover, the reliance on teleoperated data collection for fine-tuning [

8] introduces additional cost and complexity, further impeding large-scale adoption [

9]. These factors collectively highlight a critical gap between the theoretical potential of VLA models and their practical robustness and scalability.

Most existing VLA approaches rely predominantly on imitation learning or adopt passive, threshold-based uncertainty handling strategies. Such designs implicitly assume that action representations and environment dynamics remain symmetric and consistent over long horizons. In reality, long-horizon robotic manipulation is characterized by frequent symmetry violations caused by accumulated prediction errors, contact dynamics, and partial observability. When these symmetry assumptions break down, fixed-horizon or purely reactive policies struggle to adapt, leading to compounding errors and task failure. This observation motivates the need for VLA frameworks that not only exploit symmetry and invariance when they hold, but also explicitly detect and respond to symmetry-breaking events during execution.

To address these challenges, we propose the Predictive & Interactive Vision–Language–Action model (PI-VLA), a symmetry-aware framework that advances both algorithmic robustness and system accessibility. PI-VLA is built upon the principle that robust robotic manipulation requires maintaining consistency across multiple action representations while actively adapting when such consistency is violated. Specifically, our contributions are fourfold. First, we introduce a novel Cognitive–Motor Synergy (CMS) architecture that jointly generates discrete and continuous action chunks, predicts future states, and estimates state values in a single forward pass. This joint formulation enforces cross-modal action consistency, which can be interpreted as an implicit symmetry constraint across heterogeneous action representations. Second, we propose a unified training objective that combines imitation learning, reinforcement learning for long-horizon optimization, and state prediction loss for world-model learning, promoting invariance to task-relevant transformations while enabling adaptive behavior beyond pure behavior cloning. Third, we develop an Active Uncertainty-Resolving Decider (AURD) that explicitly treats action disagreement and state prediction error as symmetry-breaking signals, dynamically adjusting the execution horizon through closed-loop replanning to restore stability and robustness. Fourth, we demonstrate that such symmetry-aware control principles can be realized on a low-cost, integrated 6-DOF robotic manipulator with a repeatability better than 10 mm and an approximate cost of $300, significantly reducing hardware barriers without sacrificing performance. In addition, subject to company policy and confidentiality constraints, we will consider providing access to the automated data-collection pipeline and the dataset (over 1,200 task executions with paired language instructions, video recordings, and end-effector poses) to qualified researchers upon reasonable request and appropriate agreements, to support reproducibility at the methodological level.

From a broader reliability perspective, long-horizon robotic manipulation shares conceptual parallels with fault diagnosis and robustness analysis in large-scale interconnection networks, where global functionality must be maintained under local uncertainty and partial observability. Recent advances in reliable diagnosis under self-comparative models and g-good-neighbor properties provide principled views on how consistency constraints and redundancy can improve system-level robustness and recovery capability under noisy observations [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. These ideas support our motivation that action-consensus checking and uncertainty-triggered replanning can be interpreted as an online “diagnosis–recovery” mechanism for VLA policies.

Extensive experiments demonstrate that PI-VLA achieves state-of-the-art performance, attaining an average success rate of 73.2% on the LIBERO simulation benchmark [

16] and 88.3% on real-world in-distribution manipulation tasks. Comprehensive ablation studies confirm that each proposed component contributes to improved robustness, with symmetry-aware action consistency and uncertainty-triggered replanning playing a central role. By simultaneously addressing algorithmic symmetry, adaptive symmetry breaking, and hardware accessibility, PI-VLA aims to democratize robust robotic foundation models for real-world deployment.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews related research.

Section 3 details the PI-VLA methodology.

Section 4 describes the experimental setup, followed by results and analysis in

Section 5. We conclude in

Section 11.

2. Related Work

2.1. Vision–Language–Action Models from a Symmetry Perspective

Recent advances in vision–language models (VLMs) have enabled vision–language–action (VLA) systems that directly generate low-level control commands for robotic manipulation [

1,

3,

6,

17,

18,

19]. By leveraging internet-scale pretraining [

20] and large cross-embodiment datasets [

21,

22,

23], these models achieve strong language grounding and scene understanding [

24]. From a structural viewpoint, VLA models implicitly aim to learn representations that are invariant to task-irrelevant transformations, such as changes in viewpoint, illumination, and object appearance. However, preserving such invariances over long horizons remains a fundamental challenge.

Early VLA approaches adopted autoregressive next-token prediction paradigms inherited from language modeling [

1,

6,

17]. While effective at capturing sequential dependencies, these methods often struggle with high-frequency and dexterous control, where small symmetry violations can rapidly accumulate and destabilize execution [

25]. To address this limitation, subsequent work shifted toward continuous action generation using diffusion or flow-matching techniques [

3,

19,

26,

27]. These approaches improve action smoothness and throughput, but introduce additional computational complexity, including slower training dynamics [

28,

29] and multi-step inference procedures that can obscure the explicit detection of symmetry-breaking events [

30,

31].

More recent efforts have explored tokenization-based or hybrid action representations to balance efficiency and expressiveness. FAST encodes continuous trajectories into compact tokens, achieving significantly faster training than diffusion-based methods [

25], but its autoregressive decoding incurs high inference latency. OpenVLA-OFT [

30] mitigates this limitation by combining parallel decoding, action chunking [

32], and regression-based objectives, enabling entire action segments to be generated in a single forward pass. Despite these advances, existing methods typically treat discrete and continuous action representations independently, without explicitly enforcing consistency across modalities. As a result, discrepancies between action representations can be viewed as latent symmetry violations that remain unaddressed during execution.

More generally, exploiting structural priors and symmetry constraints has also been shown effective beyond robotics, where learning-based systems benefit from self-supervised objectives that preserve combinatorial consistency. For instance, self-supervised graph representation learning has been used to improve efficiency and stability in structured optimization problems such as maximum matching in bipartite graphs, highlighting the value of symmetry-aware representations and consistency-driven training [

33]. This line of evidence further motivates our design choice of enforcing cross-modal action consistency as an implicit symmetry constraint in PI-VLA.

Hybrid approaches that ensemble autoregressive and continuous predictions [

34] further improve robustness by aggregating multiple action hypotheses. However, such methods still rely on slow autoregressive components and lack a principled mechanism for actively responding to symmetry breaking over long horizons. In contrast, our work builds upon these foundations by jointly predicting discrete and continuous action chunks within a unified architecture, explicitly leveraging cross-modal action consistency as a symmetry constraint and using prediction disagreement as a signal for adaptive replanning.

2.2. Low-Cost Robotic Manipulators and Hardware Symmetry

Parallel to algorithmic advances, prior research has sought to reduce the cost of robotic manipulators to improve accessibility and reproducibility [

7,

35,

36,

37,

38]. Nevertheless, many commercially available “low-cost” robotic arms still retail for over

$1,000, limiting their adoption by home users and student researchers. Designing an affordable manipulator inherently involves symmetry-breaking trade-offs among workspace, degrees of freedom, payload capacity, speed, and repeatability, where improving one dimension often degrades another.

Existing sub-

$1,000 platforms frequently sacrifice kinematic symmetry or control precision, reducing their suitability for learning-based manipulation research. Furthermore, reliance on specialized software stacks, such as custom drivers [

39] or complex ROS-based frameworks [

40], introduces additional asymmetries in usability and system integration, particularly for non-expert users.

Motivated by these limitations, we develop an open-source 6-DOF robotic arm with an approximate cost of $300, achieving a balanced trade-off between kinematic symmetry, workspace coverage, and control accuracy. The platform supports a 0.2 kg payload, a 382 mm reach, end-effector speeds up to 0.7 m/s, and repeatability within 10 mm. By minimizing software dependencies and ensuring OS-agnostic operation, the proposed hardware platform complements our symmetry-aware VLA framework, enabling reproducible and accessible experimentation without relying on specialized or asymmetric system configurations.

3. Method

3.1. Symmetry Formalization

In PI-VLA, we interpret symmetry as

task-equivalent transformations under which the desired manipulation behavior should remain stable, and symmetry breaking as measurable deviations induced by uncertainty during long-horizon execution. Let

,

l, and

denote observation, instruction, and action at time

t. We consider a family of task-preserving transformations

acting on the observation–action space,

which captures nuisance variations such as viewpoint, illumination, and minor appearance changes that do not alter task intent.

A policy

is symmetry-preserving if its behavior is approximately invariant (or equivariant) under

,

ensuring consistent actions under task-equivalent perturbations. In PI-VLA, this property is encouraged by jointly learning action generation and predictive state transitions.

PI-VLA produces both discrete and continuous action representations; their agreement reflects an implicit symmetry between symbolic and geometric action spaces. Discrepancies between these actions, together with prediction errors of future states, are treated as explicit symmetry-breaking signals. When such signals exceed predefined thresholds, PI-VLA intentionally breaks open-loop execution and triggers interactive replanning, enabling controlled adaptation under uncertainty rather than assuming symmetry always holds.

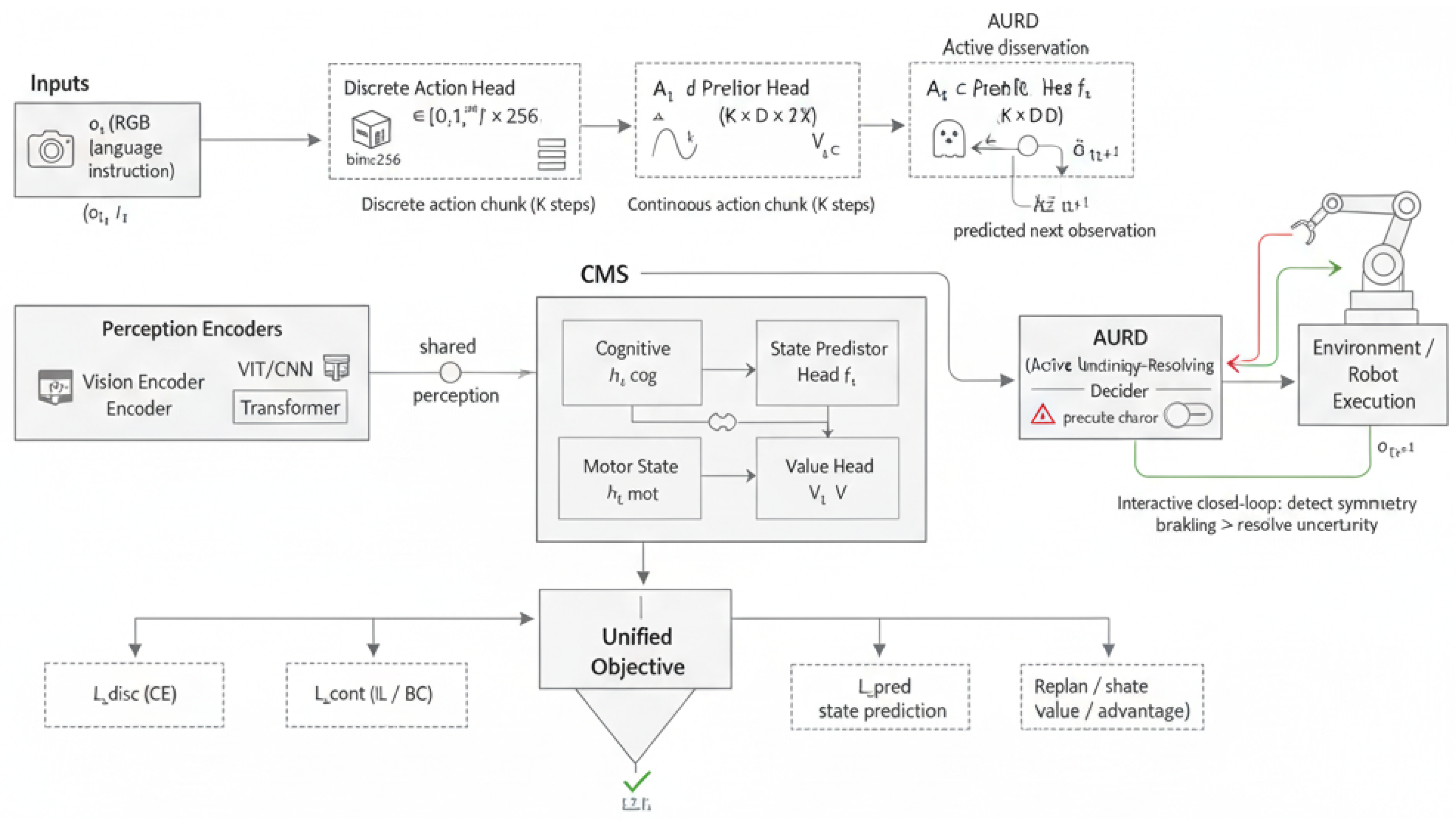

3.2. Overview of PI-VLA

We present the

Predictive &

Interactive

Vision–Language–Action model (

PI-VLA), a symmetry-aware framework that integrates imitation learning, reinforcement learning, and predictive world modeling for robust robotic manipulation. As illustrated in

Figure 2, PI-VLA departs from purely autoregressive or diffusion-based designs by explicitly enforcing cross-modal action consistency and by actively responding to symmetry-breaking events during execution. The framework consists of two tightly coupled components: a unified

Cognitive–Motor Synergy (CMS) architecture for parallel action chunk generation and state prediction, and an

Active Uncertainty-Resolving Decider (AURD) for closed-loop, uncertainty-aware decision making.

From a symmetry perspective, PI-VLA is designed to preserve structural invariances across heterogeneous action representations while enabling controlled symmetry breaking when long-horizon deviations occur. This design principle allows the model to exploit consistency when environmental dynamics remain stable, and to adaptively reconfigure execution strategies when such consistency is violated.

3.3. Cognitive–Motor Synergy (CMS) Architecture

At each time step t, PI-VLA operates on a demonstration tuple , where denotes the visual observation, is a natural-language instruction, is a 7-DOF end-effector action comprising 3D translation, 3D rotation (Euler angles), and gripper state, is the resulting next observation, and is a scalar reward indicating task progress. The policy aims to maximize the expected discounted return , with discount factor .

The CMS module maps multimodal perception

into two complementary latent representations that jointly support decision making and prediction:

where

encodes high-level semantic and predictive information, and

encodes fine-grained motor control features. Both representations are extracted from the final hidden states of a pre-trained vision–language backbone (e.g., Prismatic-7B [

41]). This dual-latent formulation establishes a structural separation between cognitive reasoning and motor execution while preserving their coupling through shared perception.

To explicitly enforce cross-modal action consistency, CMS employs four specialized projection heads that operate in parallel. The

Discrete Action Head maps

to a chunk of

K discretized action tokens using a linear projection followed by a softmax over 256 bins:

In parallel, the

Continuous Action Head outputs a chunk of

K continuous actions through a multi-layer perceptron:

The simultaneous generation of discrete and continuous action representations enables the model to maintain symmetry across heterogeneous action spaces and provides a basis for detecting action-level inconsistencies.

To support predictive reasoning, the

State Predictor Head estimates the latent representation of the next observation:

which is decoded into the predicted observation

via a lightweight decoder

g. This predictive pathway equips the model with an internal world model that captures expected state transitions under planned actions. Finally, the

State-Value Head estimates the expected cumulative return from the current cognitive state:

By jointly generating action chunks, state predictions, and value estimates in a single forward pass, the CMS architecture enforces structural coherence across perception, action, and prediction. From a symmetry viewpoint, this design preserves consistency across action modalities when environmental dynamics are stable, while exposing deviations that signal potential symmetry breaking during long-horizon execution.

3.4. Unified Training Objective

To jointly support action consistency, long-horizon optimization, and predictive reasoning, PI-VLA adopts a unified training objective that integrates imitation learning, reinforcement learning, and state prediction. From a symmetry perspective, the objective is designed to preserve invariance across heterogeneous action representations when expert supervision is reliable, while allowing controlled symmetry breaking when adaptive long-horizon behavior is required. The composite loss is defined as

where

and

are balancing coefficients.

3.4.1. Imitation Learning Loss ()

This component enforces consistency between predicted actions and expert demonstrations, serving as a primary symmetry-preserving constraint during training. Extending the collaborative training idea from [

34] to the action-chunk level, for a ground-truth action chunk

, we define

Here,

penalizes discrepancies between expert actions and discretized predictions, while the Smooth L1 loss provides robust gradients for continuous action regression. By jointly constraining discrete and continuous outputs,

promotes cross-modal action invariance and reduces representational asymmetry during early-stage learning.

3.4.2. Reinforcement Learning Loss ()

While imitation learning preserves expert-level symmetry, long-horizon manipulation often requires adaptive deviations from demonstrated behavior. To accommodate such controlled symmetry breaking, we incorporate an off-policy actor–critic objective [

42]. Using generated continuous actions

(the

k-th action in the chunk) as policy outputs, the loss maximizes the expected advantage:

where

denotes the advantage estimate computed via Generalized Advantage Estimation (GAE) [

43], with the CMS value head

serving as the baseline. This term enables PI-VLA to selectively break imitation-induced symmetry when doing so improves long-term task performance.

3.4.3. State Prediction Loss ()

To instill predictive consistency across state transitions, PI-VLA enforces alignment between internally predicted future states and actual observations in a learned latent space:

Here,

is the latent representation of the true next observation produced by a fixed encoder (e.g., DINOv2), and

is the CMS prediction. This loss constrains the learned world model to remain invariant under consistent action execution, while exposing deviations that indicate potential symmetry violations.

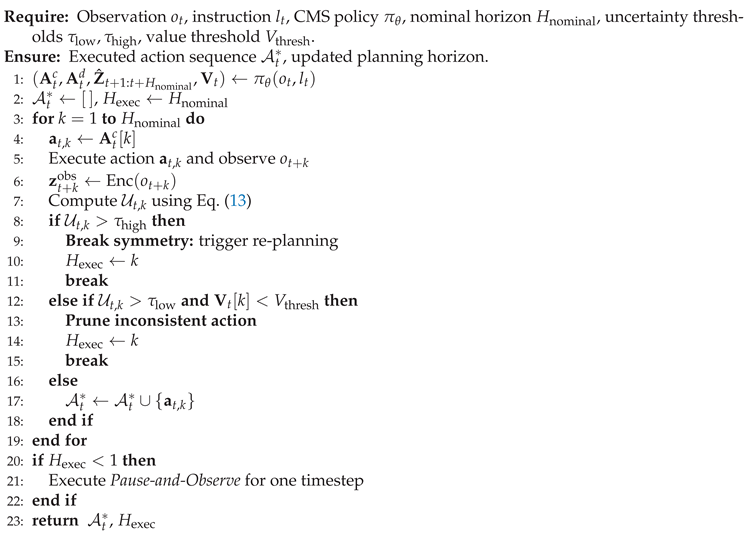

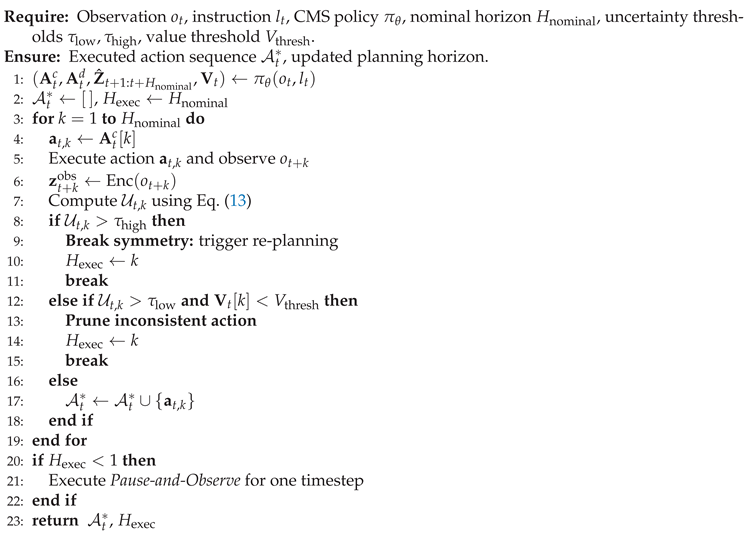

3.5. Active Uncertainty-Resolving Decider (AURD)

The Active Uncertainty-Resolving Decider (AURD) governs online execution by explicitly detecting and responding to symmetry-breaking signals during long-horizon manipulation. Rather than committing to a fixed execution horizon, AURD dynamically adjusts planning depth based on both action-level consistency and predictive reliability.

To quantify execution-time uncertainty and detect symmetry breaking, we define a composite uncertainty signal that measures both cross-modal action inconsistency and predictive state deviation. Since the discrete action head outputs a categorical distribution, we first map discrete actions to the continuous action space via a de-quantization operator.

Let

denote the discrete probability distribution over

B quantization bins for the

d-th action dimension at step

k, and let

be the corresponding bin centers. We define the de-quantized action as

Using this continuous representation, the composite uncertainty at horizon step

k is defined as

where is obtained only after executing actions up to step and observing . Therefore, AURD is implemented in a receding-horizon (MPC-style) manner: it executes actions sequentially and updates online when the corresponding observation becomes available.

AURD sequentially evaluates

together with the value estimate

. If

exceeds a high threshold

, a re-planning event is triggered to restore execution stability. If

lies between

and

but the estimated value is low, the corresponding action is pruned. Through this mechanism, uncertainty is explicitly treated as a manifestation of symmetry breaking and directly regulates execution depth.

| Algorithm 1: Active Uncertainty-Resolving Decider (AURD) |

|

3.6. Hardware Setup

To evaluate the proposed PI-VLA framework under realistic physical constraints, we deploy a cost-effective 6-DOF robotic manipulator with a total hardware cost of approximately $300. The arm provides a workspace reach of 382 mm, supports a maximum payload of 0.2 kg, and achieves an end-effector repeatability within 10 mm, which is sufficient for tabletop manipulation tasks considered in this study.

From a symmetry perspective, the hardware platform exhibits inherent structural asymmetries arising from actuator tolerances, joint backlash, and non-uniform link dynamics. These physical asymmetries introduce execution-level perturbations that cannot be fully compensated by calibration alone, making the platform an appropriate testbed for evaluating symmetry-aware decision mechanisms. In particular, repeated executions of nominally symmetric action sequences may lead to divergent outcomes due to cumulative mechanical uncertainty.

The PI-VLA policy is executed on an external computing unit, while low-level motor control is handled by an Arduino Uno via serial communication. This decoupled architecture intentionally separates high-level perception and decision-making from low-level actuation, allowing the proposed Active Uncertainty-Resolving Decider (AURD) to operate under asymmetric sensing–actuation feedback loops. As a result, the hardware setup highlights the role of predictive consistency and symmetry breaking in robust real-world robotic manipulation.

4. Experiments

This section evaluates PI-VLA from the perspectives of task performance, robustness, and symmetry-aware decision consistency in both simulated and real-world environments. All experiments are designed to assess how predictive modeling and uncertainty-driven symmetry breaking contribute to stable long-horizon execution.

4.1. Dataset

We fine-tuned the OpenVLA-7B model [

17] on a custom dataset comprising 1,200 human-demonstrated task executions collected using the proposed

$300 low-cost manipulator. Each demonstration consists of a natural-language instruction, an RGB observation sequence, and corresponding end-effector poses.

The dataset covers a diverse set of tabletop manipulation tasks, including pick-and-place, drawer opening, and block stacking. While many task instructions are linguistically symmetric (e.g., left/right or near/far), their physical execution introduces asymmetric visual observations and actuation noise. This property makes the dataset particularly suitable for studying symmetry preservation and symmetry breaking in vision–language–action policies under real-world uncertainty.

4.2. Implementation Details

We extended the OpenVLA-OFT codebase [

30] to jointly train autoregressive and regression heads within the proposed Cognitive-Motor Synergy (CMS) architecture. Fine-tuning was performed using Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) [

44,

45] with rank 32, batch size 8, and four-step gradient accumulation.

Training consisted of 100k iterations in simulation (using two NVIDIA A100 GPUs) followed by 50k iterations on real-world data. For PI-VLA, we built upon the OpenVLA-7B backbone and added CMS projection heads together with the Active Uncertainty-Resolving Decider (AURD). The state predictor was trained using a fixed DINOv2 ViT-S encoder to enforce consistency between predicted and observed latent dynamics.

The loss balancing coefficients were set to and , while the uncertainty weighting factor was fixed at . These values were selected to balance imitation consistency, long-horizon return optimization, and symmetry-aware uncertainty estimation across execution horizons.

4.3. Baselines

On the LIBERO simulation benchmark, we compare PI-VLA against representative state-of-the-art VLA methods, including Diffusion Policy [

3], Octo [

5], DiT Policy [

46], OpenVLA [

17], OpenVLA-OFT [

30], and EverydayVLA.

In addition, we benchmark against action-ensemble-based approaches, including ACT [

32], HybridVLA [

34], and COGAct [

47]. These baselines either rely on fixed-horizon execution or passive aggregation strategies and therefore do not explicitly address symmetry breaking induced by uncertainty accumulation during long-horizon execution.

4.4. Symmetry-Centric Evaluation

In addition to overall success rates, we evaluate PI-VLA from a symmetry-centric perspective by examining its behavior under task-equivalent perturbations and uncertainty-induced deviations. Results on unseen environments and visual distractions show that PI-VLA maintains higher performance than baselines, indicating effective symmetry preservation under task-equivalent transformations. Moreover, increases in cross-modal action disagreement and state prediction error consistently precede task failures, and adaptive replanning via AURD yields higher success rates than fixed-horizon execution, demonstrating the benefit of controlled symmetry breaking under uncertainty.

5. Results

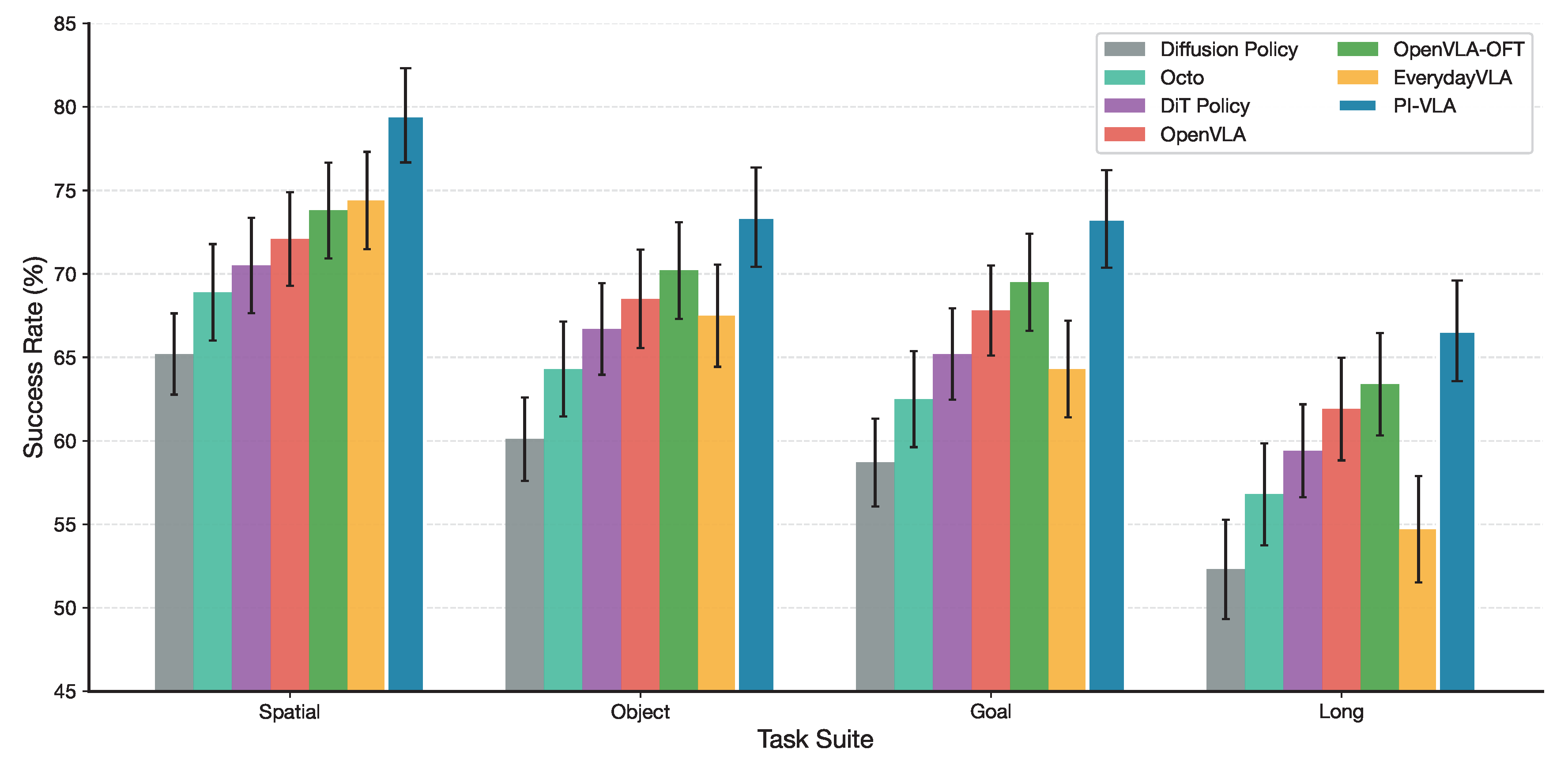

5.1. Results on the LIBERO Simulation Benchmark

As shown in

Table 1, PI-VLA achieves the highest average success rate across all four LIBERO task suites. The proposed method attains an overall success rate of 73.2%, outperforming OpenVLA-OFT (69.2%) by 4.0 percentage points and EverydayVLA (65.2%) by 8.0 percentage points.

The performance gains are particularly pronounced in long-horizon and goal-conditioned tasks, where accumulated prediction errors and execution asymmetries are more likely to disrupt fixed-horizon policies. These results indicate that uncertainty-aware symmetry breaking and adaptive horizon selection play a critical role in maintaining execution consistency over extended action sequences.

Figure 3.

Performance comparison on the LIBERO benchmark across four task suites. PI-VLA consistently outperforms all baseline methods.

Figure 3.

Performance comparison on the LIBERO benchmark across four task suites. PI-VLA consistently outperforms all baseline methods.

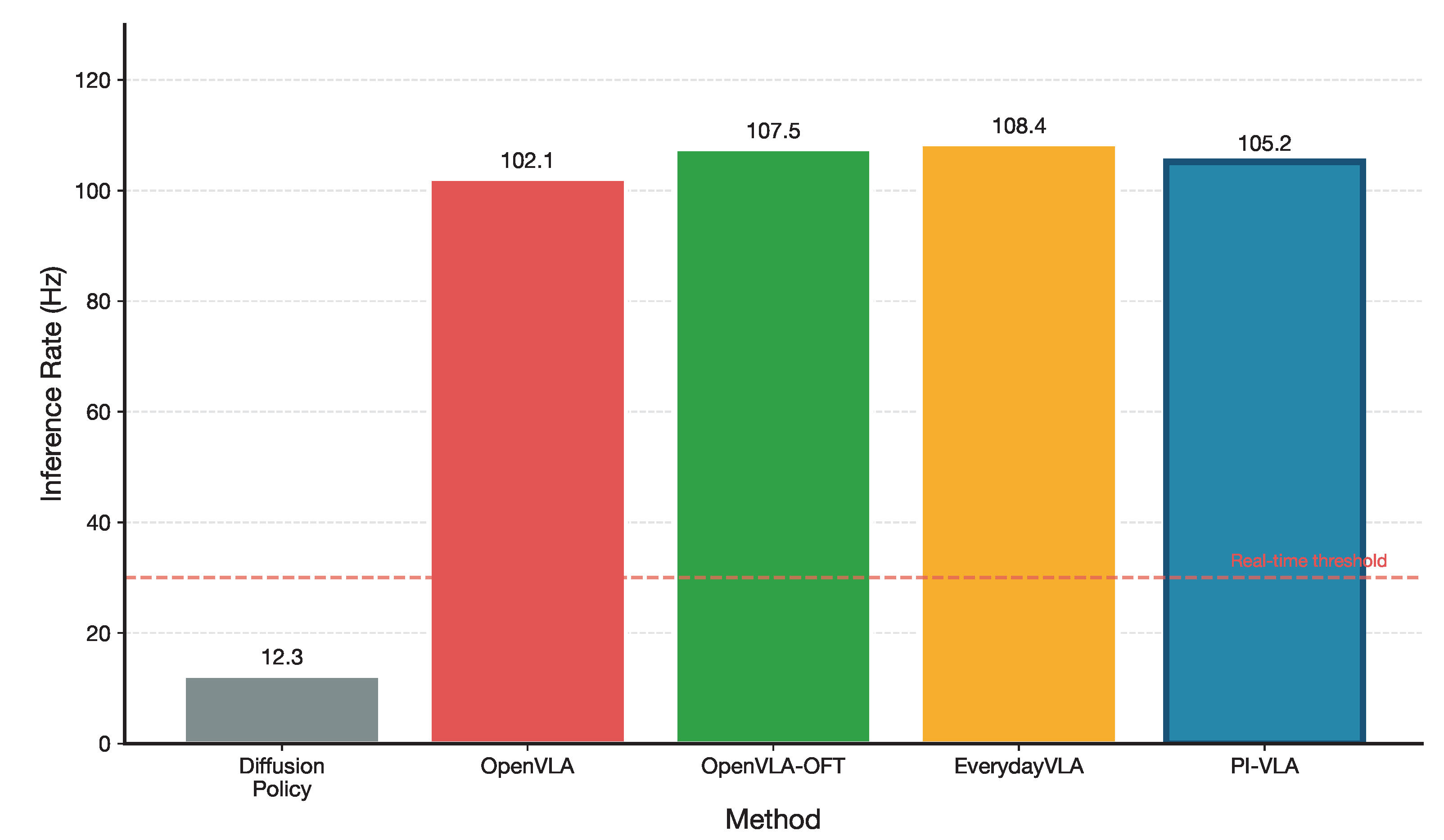

PI-VLA achieves an inference rate of 105.2 Hz, incurring an average overhead of approximately 1.2 ms relative to OpenVLA-OFT. This overhead corresponds to the additional forward passes required for state prediction and uncertainty evaluation in the AURD module.

Despite this additional computational complexity, PI-VLA maintains real-time performance while enabling adaptive symmetry breaking and consistency preservation during execution.

Figure 4.

Inference rate comparison across methods. PI-VLA maintains competitive throughput while providing uncertainty-aware planning capabilities.

Figure 4.

Inference rate comparison across methods. PI-VLA maintains competitive throughput while providing uncertainty-aware planning capabilities.

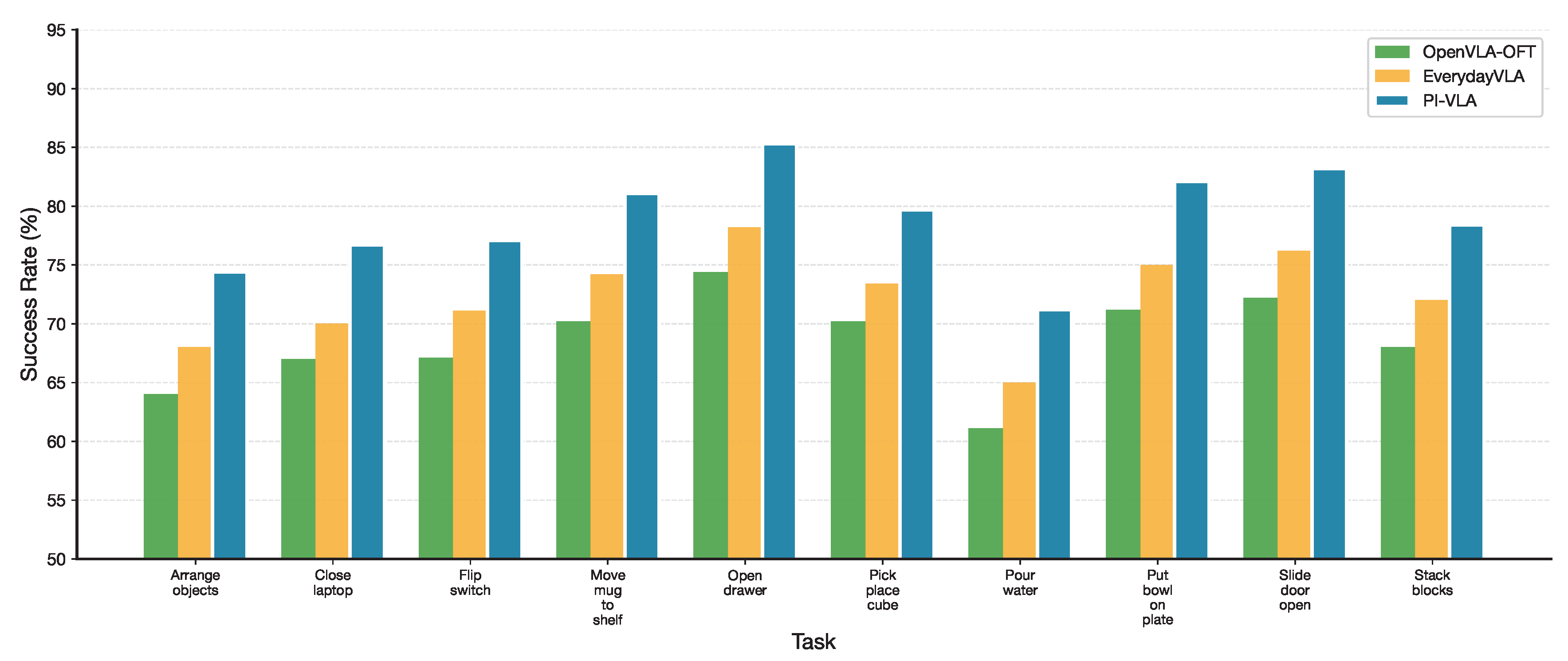

Figure 5 provides a detailed per-task breakdown on the LIBERO Spatial suite. PI-VLA consistently outperforms baseline methods across all task categories, indicating that the proposed framework effectively mitigates performance degradation caused by asymmetric observations and execution noise, even in tasks that are nominally symmetric at the instruction level.

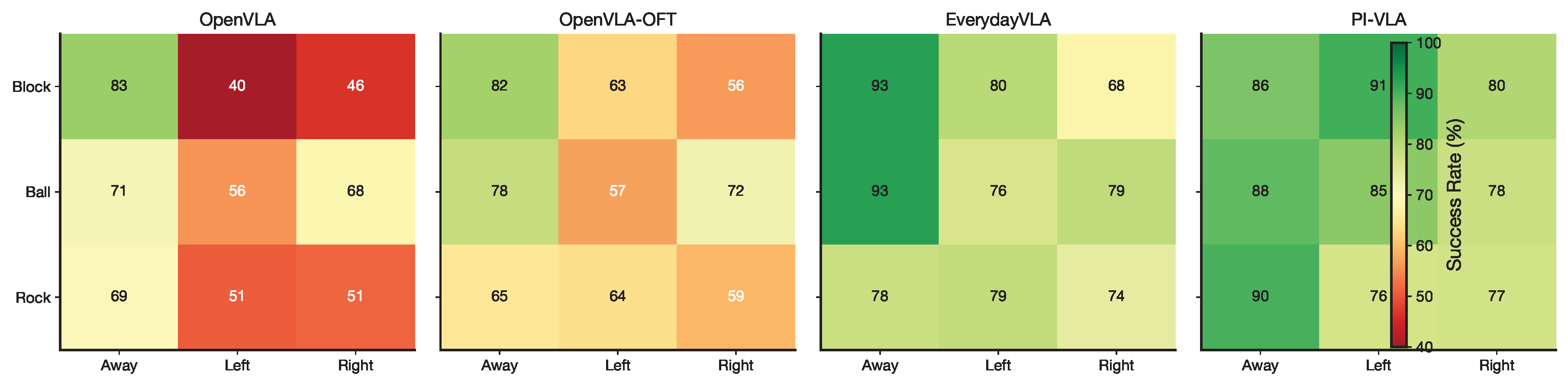

5.2. Results on Real-World Tests

We further evaluate PI-VLA on real-world pick-and-place tasks executed on the low-cost robotic platform. As reported in

Table 2, PI-VLA achieves a new state-of-the-art average success rate of 88.3%, outperforming EverydayVLA (82.2%) by 6.1 percentage points and OpenVLA-OFT (70.0%) by 18.3 percentage points.

These real-world tasks exhibit substantial execution asymmetries caused by non-uniform lighting, actuator backlash, and object-dependent interaction dynamics. Despite these symmetry-breaking factors, PI-VLA maintains consistently high success rates across all object categories and instruction directions.

Figure 6 visualizes the success-rate distribution, demonstrating that the proposed uncertainty-aware execution mechanism effectively preserves action consistency under asymmetric physical conditions.

5.3. Generalization and Robustness

We next analyze the generalization and robustness properties of PI-VLA under symmetry-breaking distribution shifts. As summarized in

Table 3, PI-VLA consistently outperforms baseline methods on unseen tasks, unseen environments, and both static and dynamic visual distractions.

These evaluation settings introduce varying degrees of symmetry violation between training and testing conditions, including changes in scene layout, object appearance, and background motion. The superior performance of PI-VLA indicates that predictive modeling and uncertainty-aware replanning effectively mitigate performance degradation caused by accumulated asymmetries.

The importance of robustness under visual distribution shifts is also widely recognized in applied vision systems, especially in agriculture and field robotics, where changing illumination, cluttered backgrounds, and seasonal variations frequently violate training-time assumptions. Recent studies on image-based high-throughput phenotyping trends, crop-chain deep learning surveys, and real-time plant-object recognition models emphasize that reliable deployment requires strong generalization under uncontrolled visual conditions and strict latency constraints [

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53]. These findings are consistent with our observation that uncertainty-aware closed-loop replanning is critical for maintaining stable performance when symmetry is broken by distractors and unseen conditions.

Figure 7.

Radar chart visualizing generalization performance across different symmetry-breaking conditions. PI-VLA exhibits superior robustness in all evaluated scenarios.

Figure 7.

Radar chart visualizing generalization performance across different symmetry-breaking conditions. PI-VLA exhibits superior robustness in all evaluated scenarios.

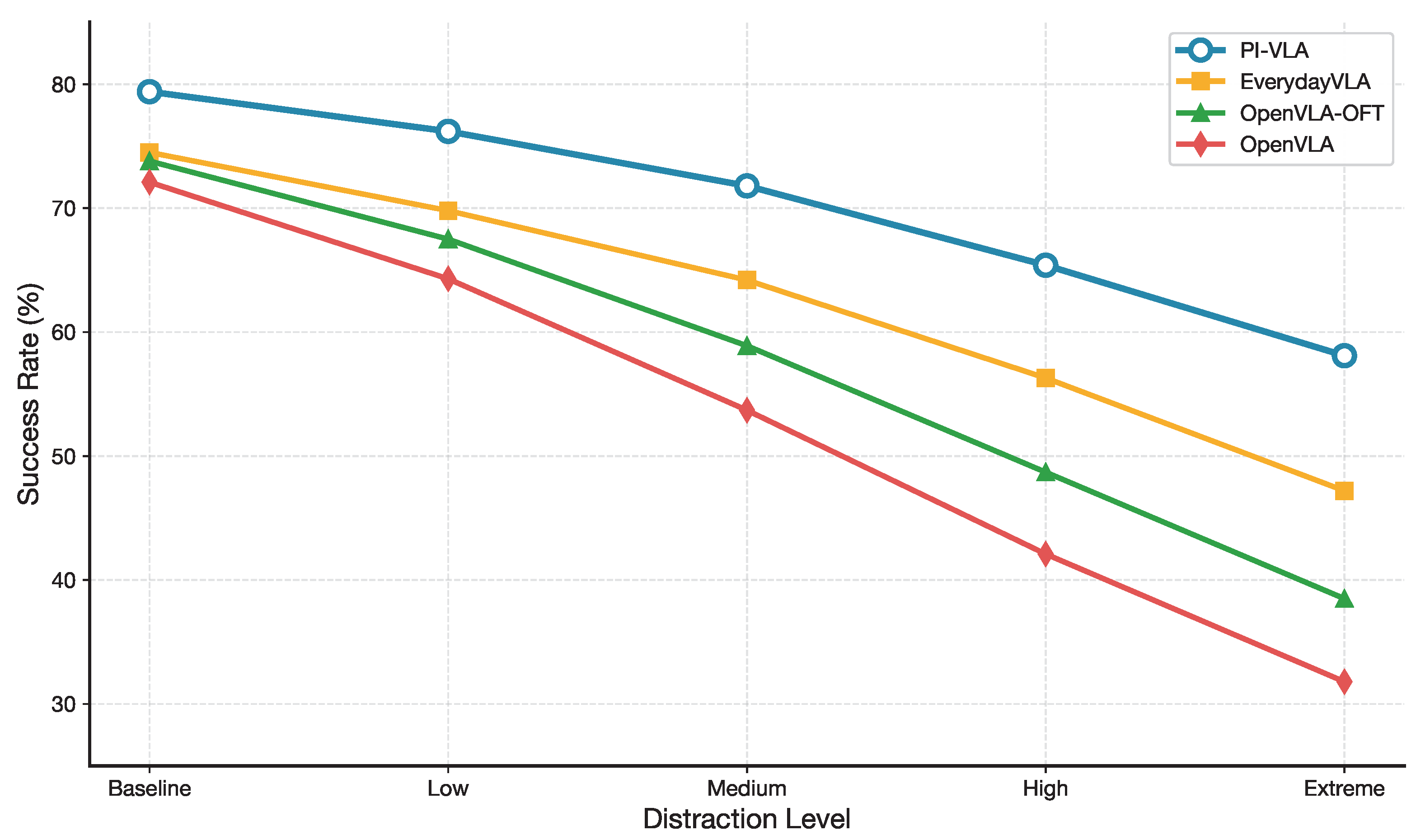

Figure 8 illustrates how task success rates degrade as the level of visual distraction increases. While baseline methods suffer rapid performance deterioration, PI-VLA maintains significantly higher success rates even under severe distraction. This behavior highlights the effectiveness of uncertainty-aware symmetry breaking in preventing error accumulation during long-horizon execution.

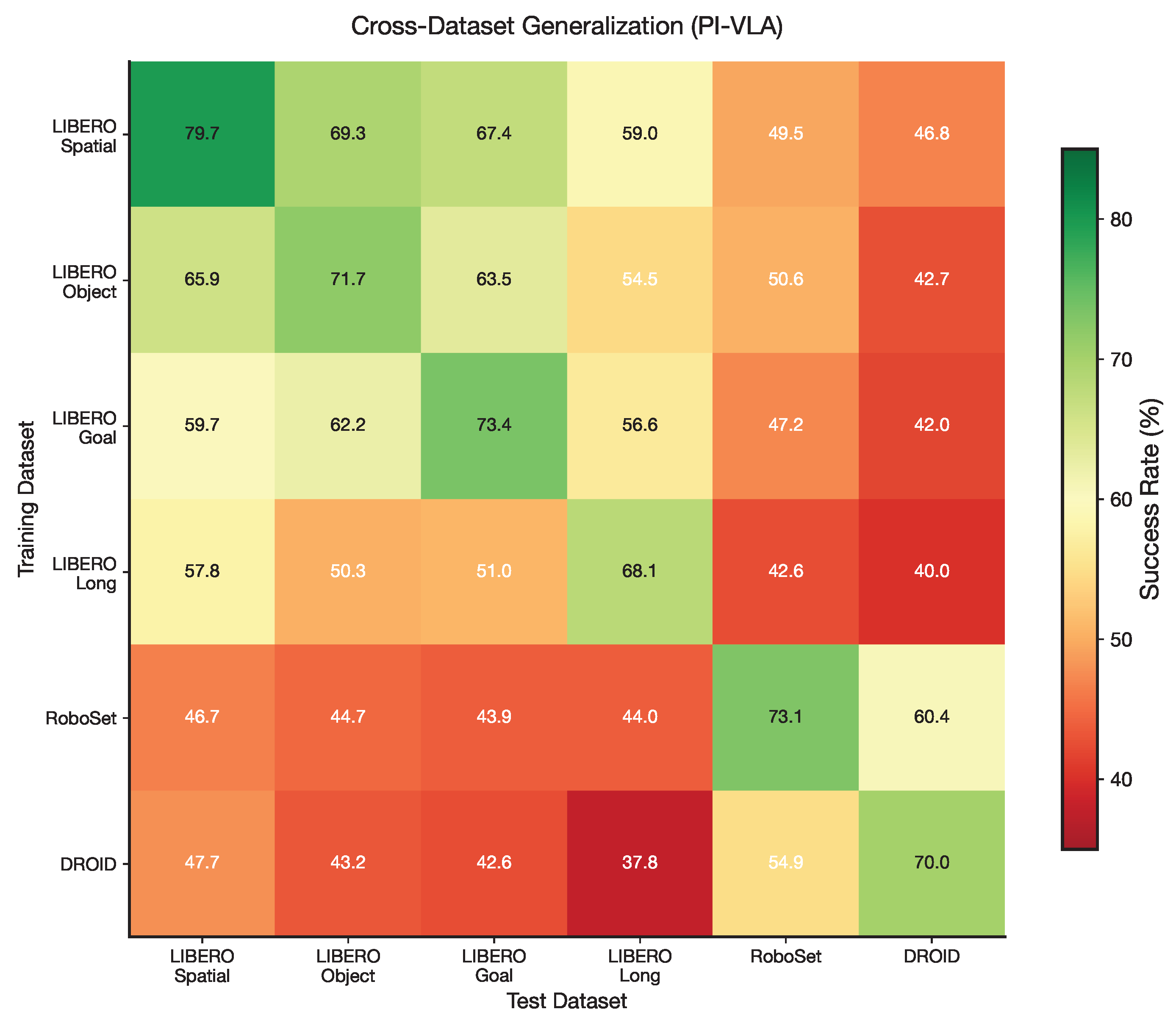

We further examine cross-dataset generalization in

Figure 9. The resulting transfer matrix shows that PI-VLA achieves strong cross-domain performance when trained and evaluated on datasets with differing visual and task symmetries. This result confirms that the proposed framework learns representations and decision policies that generalize beyond dataset-specific symmetry assumptions.

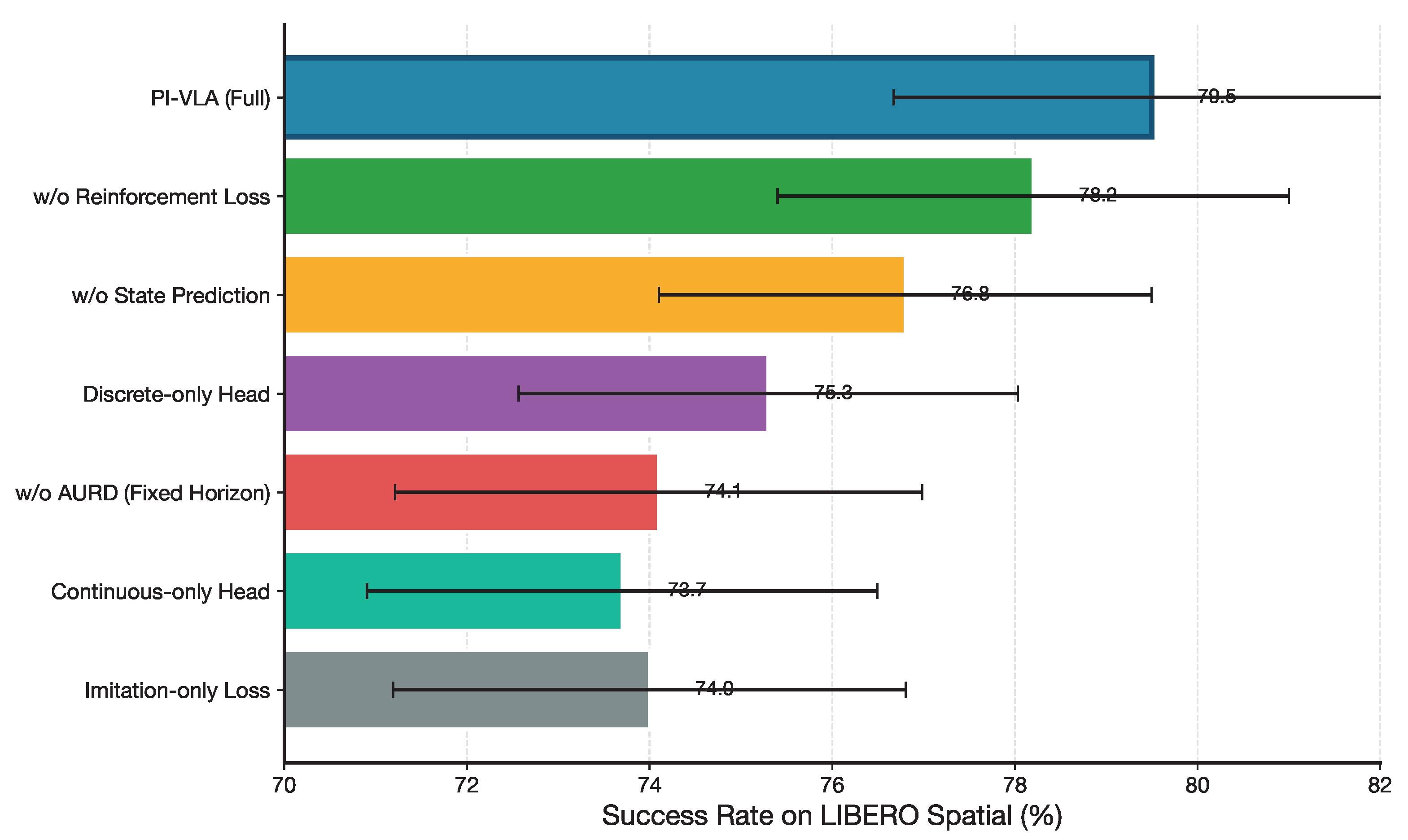

6. Ablation Studies

We conduct comprehensive ablation studies to analyze the contribution of each component in PI-VLA from the perspective of symmetry preservation, symmetry breaking, and execution consistency. All ablation results are reported on the LIBERO Spatial suite, which emphasizes long-horizon spatial reasoning under accumulated uncertainty.

6.1. Ablation on CMS Action Heads

The Cognitive-Motor Synergy (CMS) module jointly models discrete and continuous action representations, enabling consistency across heterogeneous action modalities. As shown in

Table 4, removing either modality leads to notable performance degradation.

Using only discrete or continuous action heads reduces the success rate by 4.2 and 5.6 percentage points, respectively, compared to the full CMS model. This result indicates that maintaining symmetry between symbolic (discrete) and geometric (continuous) action spaces is critical for stable execution.

6.2. Ablation on Unified Training Objective

We next evaluate the role of each component in the unified training objective. As summarized in

Table 5, removing the state prediction loss leads to a 2.7% decrease in success rate, highlighting the importance of predictive consistency for long-horizon decision making.

Similarly, excluding the reinforcement learning loss reduces the model’s ability to optimize delayed returns, while imitation-only training yields the largest performance drop. These results demonstrate that symmetry between imitation, optimization, and prediction objectives is necessary to maintain coherent behavior across multiple execution steps.

6.3. Ablation on Active Uncertainty-Resolving Decider (AURD)

The Active Uncertainty-Resolving Decider (AURD) explicitly regulates symmetry breaking during execution by dynamically adjusting the planning horizon.

Table 6 compares PI-VLA with several alternative execution strategies.

Using a fixed execution horizon reduces performance by 5.4 percentage points, indicating that rigid, symmetry-assuming execution is insufficient under accumulated uncertainty. Replacing AURD with adaptive horizon heuristics or temporal ensembling partially recovers performance but remains inferior to the proposed uncertainty-driven mechanism.

Figure 10.

Ablation study results showing the contribution of each PI-VLA component. The full model significantly outperforms all ablated variants.

Figure 10.

Ablation study results showing the contribution of each PI-VLA component. The full model significantly outperforms all ablated variants.

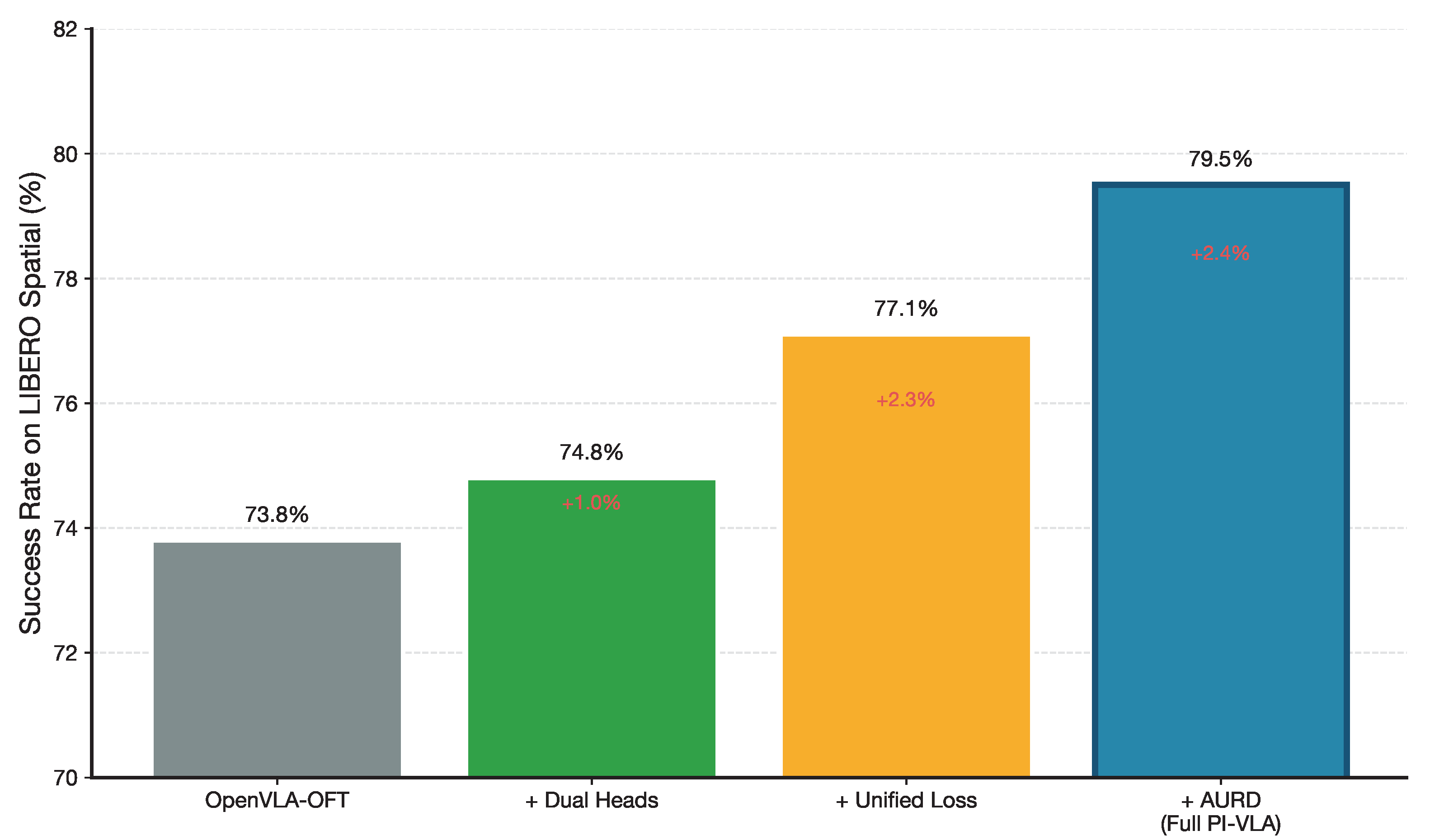

6.4. Comprehensive Component Analysis

We further perform a comprehensive component analysis by incrementally adding PI-VLA modules to the OpenVLA-OFT baseline. As shown in

Table 7 and

Figure 11, each component contributes a measurable improvement.

The introduction of dual action heads enhances action-space consistency, the unified training objective improves predictive symmetry across time, and the AURD module provides the final performance gain by actively resolving uncertainty-induced asymmetries during execution.

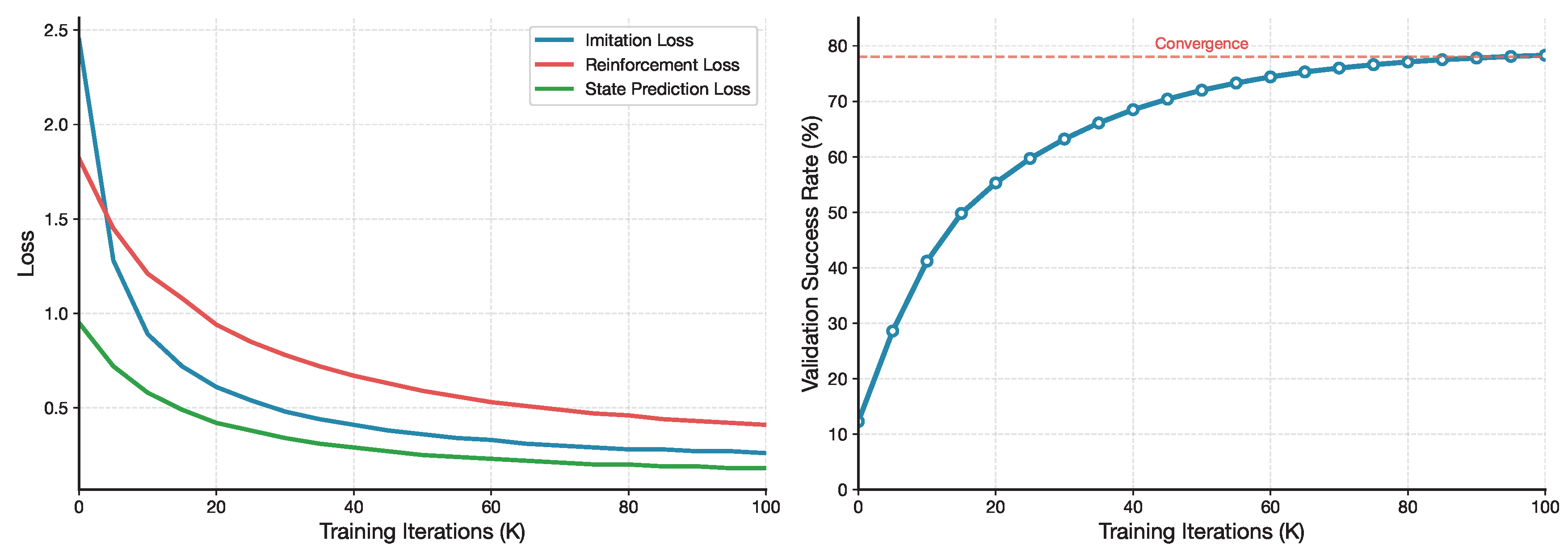

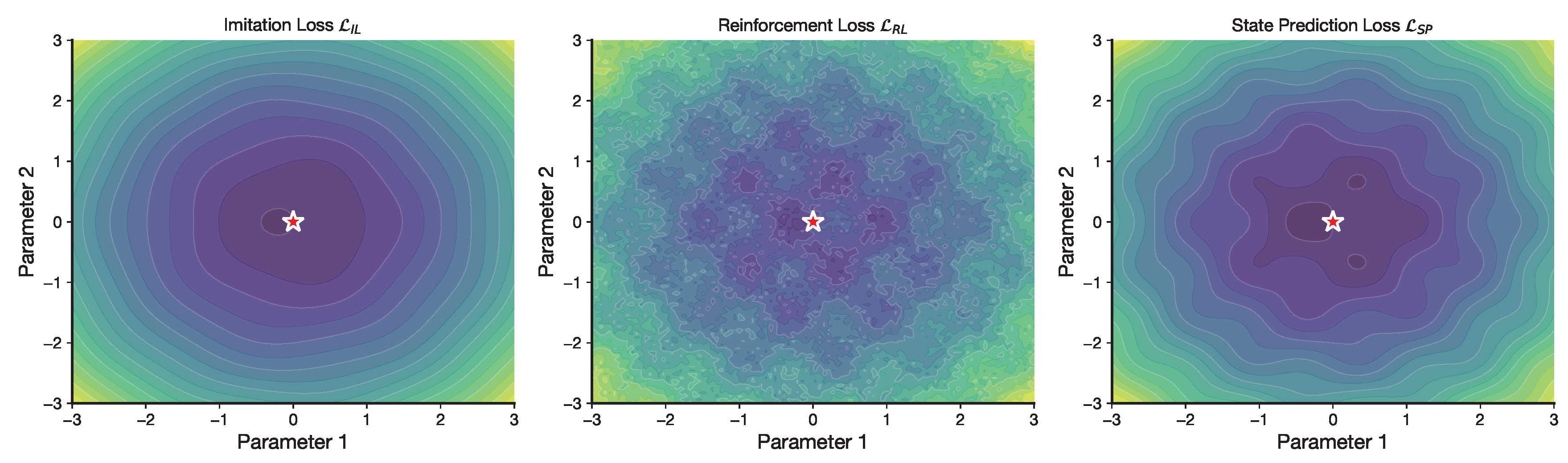

7. Training Dynamics Analysis

Figure 12 illustrates the training dynamics of PI-VLA from the perspective of temporal consistency. The imitation loss converges rapidly in the early training stage, indicating effective alignment between policy outputs and expert demonstrations. In contrast, the state prediction loss decreases more gradually, reflecting the progressive acquisition of predictive symmetry across future states.

The validation success rate increases monotonically and stabilizes near the 100k-iteration mark, suggesting that the unified training objective promotes stable convergence without oscillatory behavior. These observations indicate that PI-VLA maintains a balanced symmetry between imitation, optimization, and prediction objectives throughout training.

From an optimization viewpoint, stability and interpretability of training dynamics are closely related to recent progress in optimization-inspired deep models for signal processing, where explicit algorithmic structures (e.g., ADMM-style updates, residual shrinkage, and time–frequency analysis priors) are integrated into neural architectures to improve convergence behavior and robustness. Representative works on deep time–frequency analysis and optimization-inspired frequency estimation demonstrate that embedding structured priors can lead to smoother optimization landscapes, reduced sensitivity to hyperparameters, and improved generalization in non-ideal conditions [

54,

55,

56,

57,

58]. These insights align with our empirical observations on PI-VLA’s stable convergence and robustness under varying training configurations.

8. Uncertainty Analysis

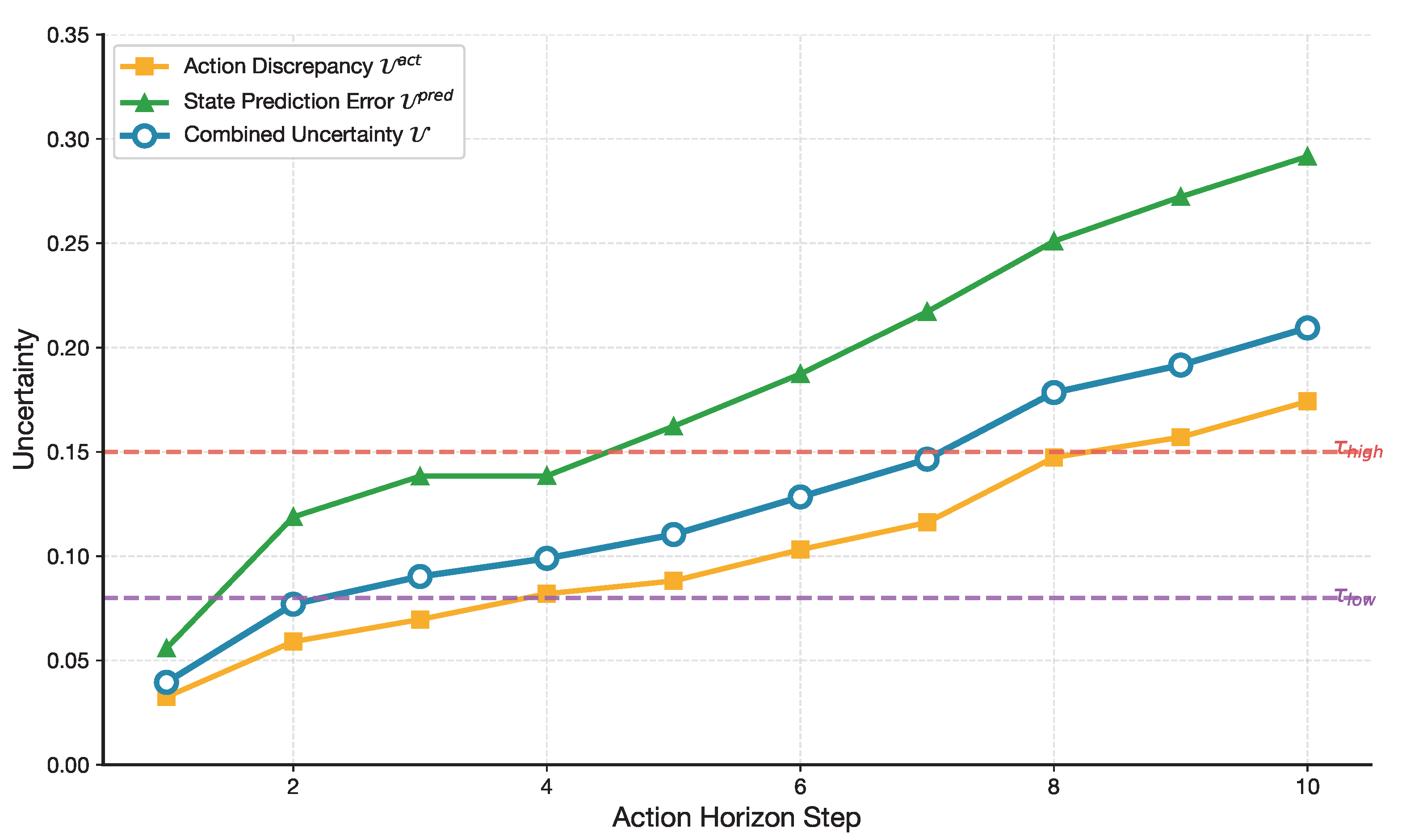

We next analyze how uncertainty evolves along the action horizon and how it influences symmetry breaking during execution. As shown in

Figure 13, both action discrepancy and state prediction error increase with horizon length. This trend reflects the progressive violation of symmetry assumptions when executing longer open-loop action sequences.

The combined uncertainty signal aggregates these effects and triggers re-planning once predefined thresholds are exceeded, preventing uncontrolled divergence from nominal trajectories. This mechanism enables PI-VLA to perform controlled symmetry breaking, intervening only when accumulated uncertainty threatens execution consistency.

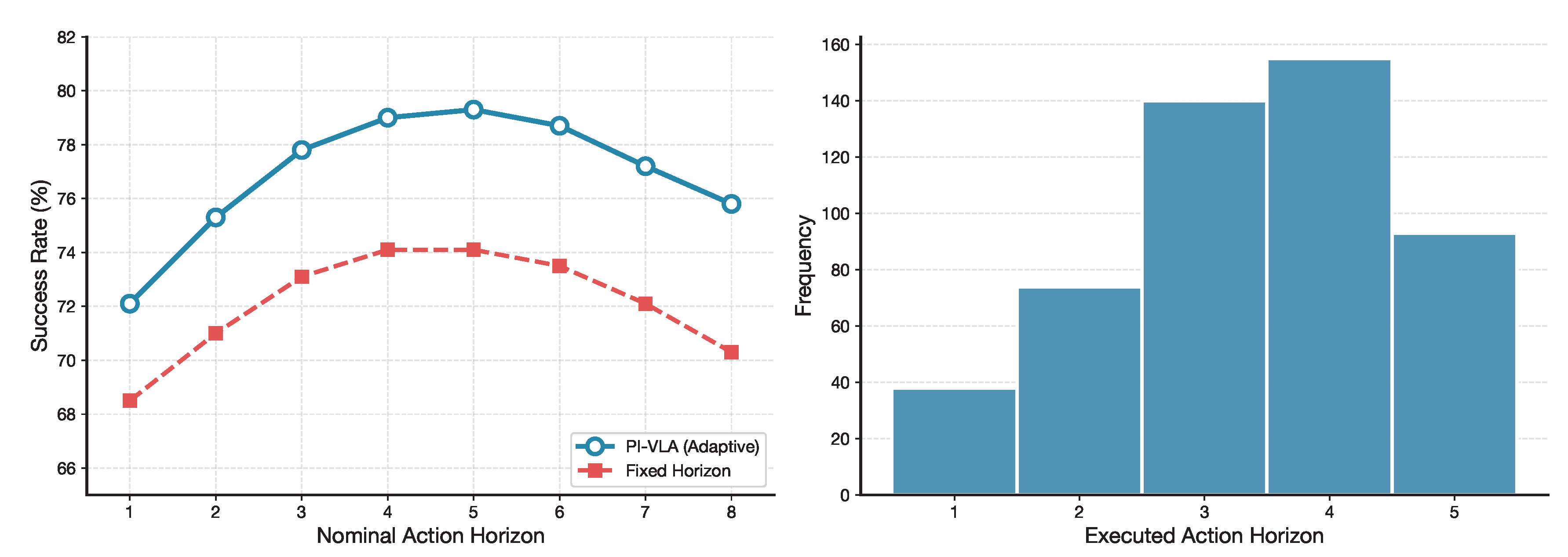

Figure 14 further examines the relationship between action horizon length and task success. Fixed-horizon strategies implicitly assume temporal symmetry across execution steps and suffer from performance degradation as horizon length increases. In contrast, the adaptive horizon selection implemented by AURD consistently yields higher success rates, with optimal nominal horizons between four and five steps.

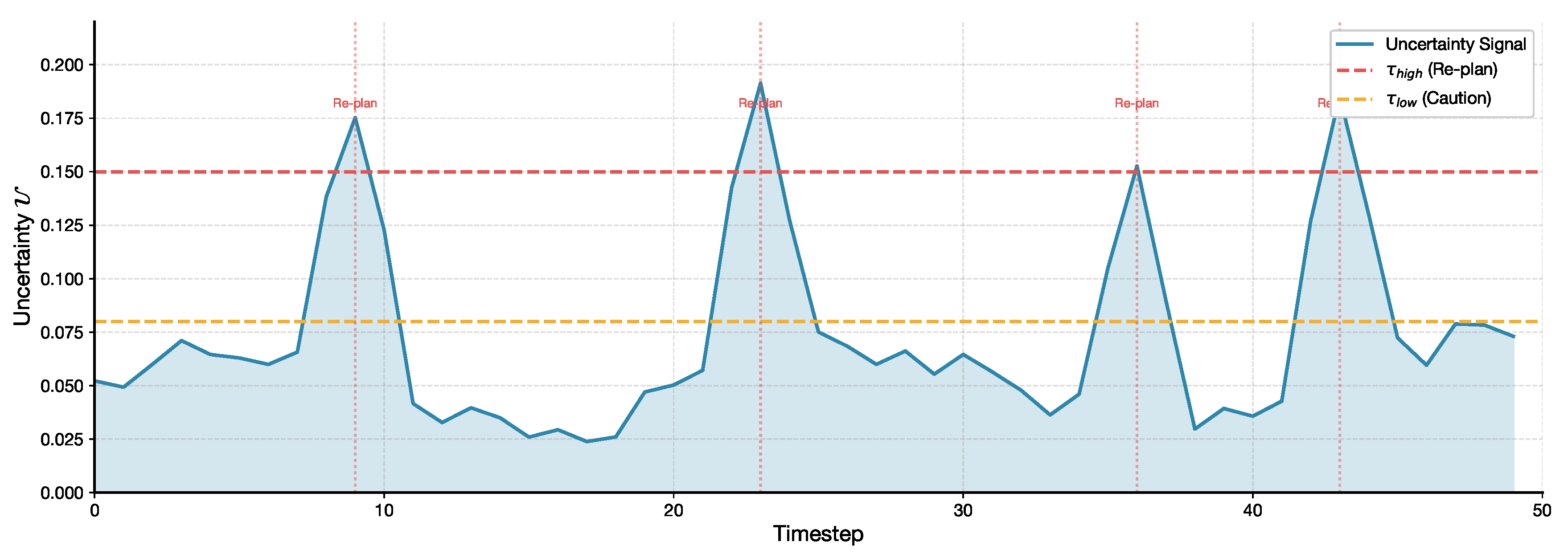

Figure 15 visualizes the decision-making process of AURD during a representative task execution. Re-planning events are triggered when the uncertainty signal exceeds the high threshold, demonstrating how symmetry-breaking decisions are localized in time and driven by predictive inconsistency rather than heuristic rules.

9. Hyperparameter Sensitivity

We analyze the sensitivity of PI-VLA to key hyperparameters governing the balance between learning objectives and uncertainty estimation.

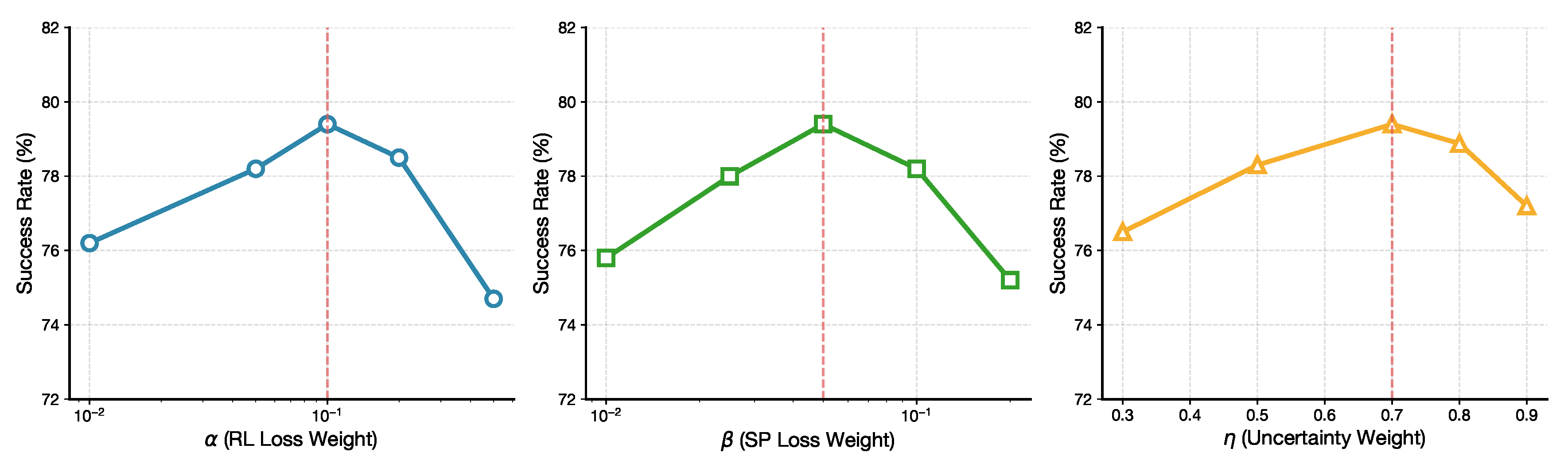

Figure 16 reports performance across different values of

(reinforcement loss weight),

(state prediction loss weight), and

(uncertainty weighting factor).

The model exhibits robust performance across a wide parameter range, indicating that the proposed framework does not rely on fragile hyperparameter tuning. Optimal performance is achieved at , , and , corresponding to a balanced symmetry between reward optimization, predictive consistency, and uncertainty-driven adaptation.

10. Scalability Analysis

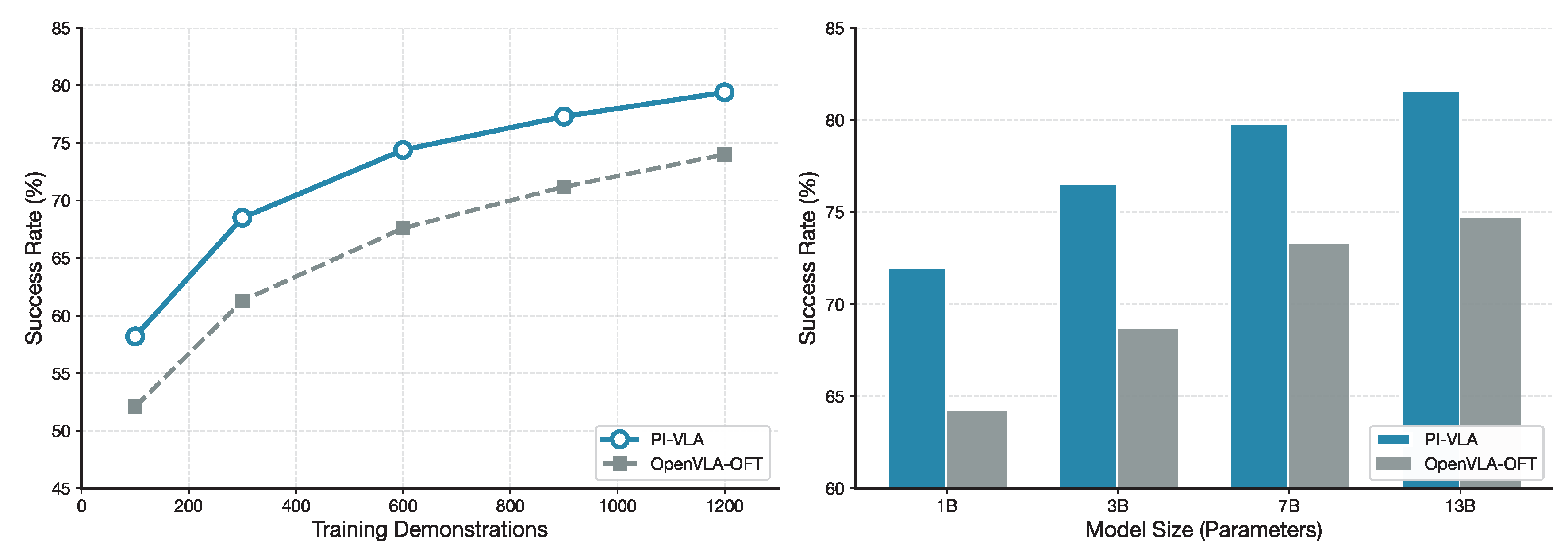

Figure 17 evaluates the scalability of PI-VLA with respect to training data size and model capacity. Compared to OpenVLA-OFT, PI-VLA achieves higher success rates with fewer demonstrations, indicating improved data efficiency.

As model size increases, PI-VLA exhibits consistent performance gains, suggesting that the proposed architecture preserves structural symmetry across scales. These results demonstrate that the framework can effectively leverage additional data and capacity without compromising stability.

Figure 18 visualizes the loss landscape of the unified training objective. The imitation loss exhibits a smooth and well-conditioned surface, while the reinforcement loss shows a more complex structure. Despite this heterogeneity, the joint optimization remains stable, indicating that the different loss components interact in a complementary and symmetry-preserving manner.

11. Conclusion

This work introduces PI-VLA, a symmetry-aware framework for robust and adaptive robotic manipulation. By integrating imitation learning, reinforcement learning, and predictive world modeling into a unified architecture, PI-VLA explicitly addresses the tension between symmetry assumptions and real-world asymmetries.

The Cognitive-Motor Synergy (CMS) module enforces consistency across heterogeneous action representations, while the Active Uncertainty-Resolving Decider (AURD) enables controlled symmetry breaking through uncertainty-driven horizon adaptation. Extensive experiments demonstrate that PI-VLA achieves state-of-the-art performance on the LIBERO benchmark and significantly improves robustness in real-world manipulation tasks.

Future work may explore scaling predictive world models, extending the framework to multi-robot systems, and developing more principled uncertainty estimators to further enhance symmetry-aware decision making in complex environments.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data Availability Statement: Due to company policy and confidentiality restrictions (e.g., proprietary hardware/software configurations, internal data-collection pipeline, and related experimental logs), the datasets and raw experimental records supporting the findings of this study are not publicly available. Access may be provided by the corresponding author upon reasonable request, subject to institutional/company approval and applicable confidentiality agreements.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions, which helped improve the quality of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The company affiliation did not influence the scientific conclusions of this study.

References

- Brohan, A.; Brown, N.; Carbajal, J.; Chebotar, Y.; Dabis, J.; Finn, C.; Gober, K.; Joshi, M.; Julian, R.; Kalashnikov, D.; et al. RT-1: Robotics Transformer for Real-World Control at Scale. arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.06817 2022.

- Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Changpinyo, S.; Piergiovanni, A.; Padlewski, P.; Salz, D.; Goodman, S.; Grycner, A.; Mustafa, B.; Beyer, L.; et al. PaLI: A Jointly-Scaled Multilingual Language-Image Model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.06794 2022.

- Chi, C.; Feng, S.; Du, Y.; Xu, Z.; Cousineau, E.; Burchfiel, B.; Song, S. Diffusion Policy: Visuomotor Policy Learning via Action Diffusion. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of Robotics: Science and Systems (RSS), 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, A.; Lee, Y.; Abbeel, P.; Roberts, S. Decomposing the Generalization Gap in Imitation Learning for Visual Robotic Manipulation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.03659 2024.

- Octo Model Team.; Ghosh, D.; Walke, H.; Pertsch, K.; Black, K.; Mees, O.; Dasari, S.; Hejna, J.; Kreiman, T.; Xu, C.; et al. Octo: An Open-Source Generalist Robot Policy. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.12213 2024.

- Brohan, A.; Brown, N.; Carbajal, J.; Chebotar, Y.; Chen, X.; Choromanski, K.; Ding, T.; Driess, D.; Dubey, A.; Finn, C.; et al. RT-2: Vision-Language-Action Models Transfer Web Knowledge to Robotic Control. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.15818 2023.

- Quigley, M.; Asbeck, A.; Ng, A. Low-cost Accelerometers for Robotic Manipulator Perception. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dass, S.; Yoneda, T.; Desai, A.; Hawkins, C.; Stone, P.; Kroemer, O. PATO: Policy Assisted TeleOperation for Scalable Robot Data Collection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of Robotics: Science and Systems (RSS), 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, H.I.; et al. A Roadmap for US Robotics: From Internet to Robotics. Computing Community Consortium 2016.

- Wang, M.; Xu, S.; Jiang, J.; Xiang, D.; Hsieh, S.Y. Global reliable diagnosis of networks based on Self-Comparative Diagnosis Model and g-good-neighbor property. Journal of Computer and System Sciences 2025, 103698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Xiang, D.; Qu, Y.; Li, G. The diagnosability of interconnection networks. Discrete Applied Mathematics 2024, 357, 413–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wang, S. Connectivity and diagnosability of center k-ary n-cubes. Discrete Applied Mathematics 2021, 294, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, D.; Hsieh, S.Y.; et al. G-good-neighbor diagnosability under the modified comparison model for multiprocessor systems. Theoretical Computer Science 2025, 1028, 115027. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Wang, Z.; Wang, M.; Han, W. g-Good-neighbor conditional diagnosability of star graph networks under PMC model and MM* model. Frontiers of Mathematics in China 2017, 12, 1221–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Lin, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, M. Sufficient conditions for graphs to be maximally 4-restricted edge connected. Australas. J Comb. 2018, 70, 123–136. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Zhu, Y.; Gao, C.; Feng, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Stone, P. LIBERO: Benchmarking Knowledge Transfer for Lifelong Robot Learning. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.J.; Pertsch, K.; Karamcheti, S.; Xiao, T.; Balakrishna, A.; Nair, S.; Rafailov, R.; Foster, E.; Lam, G.; Sanketi, P.; et al. OpenVLA: An Open-Source Vision-Language-Action Model. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of The 8th Conference on Robot Learning (CoRL), 2024; pp. 2679–2713. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Liu, M.; Zhang, H.; Yu, C.; Xu, J.; Wu, H.; Cheang, C.; Jing, Y.; Zhang, W.; Liu, H.; et al. Vision-Language Foundation Models as Effective Robot Imitators. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.01378 2023.

- Black, K.; Brown, N.; Driess, D.; Esber, A.; Suber, M.; Vijayakumar, A.; Chi, C.; Finn, C.; Levine, S. π0: A Vision-Language-Action Flow Model for General Robot Control. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.24164 2024.

- Touvron, H.; Lavril, T.; Izacard, G.; Martinet, X.; Lachaux, M.A.; Lacroix, T.; Rozière, B.; Goyal, N.; Hambro, E.; Azhar, F.; et al. LLaMA: Open and Efficient Foundation Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.13971 2023. arXiv:2302.13971.

- Open X-Embodiment Collaboration. Open X-Embodiment: Robotic Learning Datasets and RT-X Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.08864 2024.

- Walke, H.; Black, K.; Lee, A.; Kim, M.J.; Du, M.; Zheng, C.; Zhao, T.; Hansen-Estruch, P.; Vuong, Q.; Lu, A.; et al. BridgeData V2: A Dataset for Robot Learning at Scale. In Proceedings of the Conference on Robot Learning (CoRL), 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Khazatsky, A.; Pertsch, K.; Nair, S.; Balakrishna, A.; Dasari, S.; Karamcheti, S.; Nasiriany, S.; Srirama, M.K.; Chen, L.Y.; et al. DROID: A Large-Scale In-The-Wild Robot Manipulation Dataset. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.12945 2024.

- Zhou, X.; Ren, Z.; Min, S.; Liu, M. Language Conditioned Spatial Relation Reasoning for 3D Object Grounding. arXiv preprint arXiv:2211.09646 2023.

- Pertsch, K.; Kim, M.J.; Luo, J.; Finn, C.; Levine, S. FAST: Efficient Action Tokenization for Vision-Language-Action Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.09747 2025.

- Zhao, T.Z.; Tompson, J.; Driess, D.; Florence, P.; Xia, F.; et al. ALOHA 2: An Enhanced Low-Cost Hardware for Bimanual Teleoperation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.02292 2024.

- Wen, J.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Weng, M.; Mu, Y.; et al. TinyVLA: Towards Fast, Data-Efficient Vision-Language-Action Models for Robotic Manipulation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.12514 2025.

- Zhang, H.; Wu, Y.; Liu, E.; Shih, C.; Zhou, Z.; Torralba, A. Improving Training Efficiency of Diffusion Models via Multi-Stage Framework and Tailored Multi-Decoder Architecture. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.09181 2024.

- Wang, Z.; Zheng, H.; He, P.; Chen, W.; Zhou, M. Patch Diffusion: Faster and More Data-Efficient Training of Diffusion Models. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.J.; Finn, C.; Liang, P. Fine-Tuning Vision-Language-Action Models: Optimizing Speed and Success. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.19645 2025.

- Ho, J.; Jain, A.; Abbeel, P. Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2020, Vol. 33, pp. 6840–6851.

- Zhao, T.Z.; Kumar, V.; Levine, S.; Finn, C. Learning Fine-Grained Bimanual Manipulation with Low-Cost Hardware. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of Robotics: Science and Systems (RSS), 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, C.H.; Qu, Y.; Yao, Y.; Wang, M.J.S. HybridGNN: A Self-Supervised graph neural network for efficient maximum matching in bipartite graphs. Symmetry 2024, 16, 1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chen, H.; An, P.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, R.; Gu, C.; Li, X.; Guo, Z.; Chen, S.; Liu, M.; et al. HybridVLA: Collaborative Diffusion and Autoregression in a Unified Vision-Language-Action Model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.10631 2025.

- Yang, B.; Jayaraman, D.; Levine, S.; et al. RepLAB: A Reproducible Low-Cost Arm Benchmark Platform for Robotic Learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, H.; Zhuo, Z.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Z. Aha-Robot: Low-Cost, Open-Source Humanoid Research Platform for Robot Learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.02545 2025. arXiv:2502.02545.

- Wu, P.; Xie, Y.; Gopinath, D.; Koh, J. GELLO: A General, Low-Cost, and Intuitive Teleoperation Framework for Robot Manipulators. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.13037 2024.

- Cocota, J.A.N.; Holanda, G.B.; Fujimoto, L.B.M. A Low-Cost 6-DOF Serial Robotic Arm for Educational Purposes. IFAC Proceedings Volumes 2012, 45, 285–290. [Google Scholar]

- Bruyninckx, H. Open Robot Control Software: The OROCOS Project. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 2001; pp. 2523–2528. [Google Scholar]

- Quigley, M.; Conley, K.; Gerkey, B.; Faust, J.; Foote, T.; Leibs, J.; Wheeler, R.; Ng, A.Y. ROS: An Open-Source Robot Operating System. In Proceedings of the ICRA Workshop on Open Source Software, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Karamcheti, S.; Nair, S.; Balakrishna, A.; Liang, P.; Kollar, T.; Sadigh, D. Prismatic VLMs: Investigating the Design Space of Visually-Conditioned Language Models. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Song, X.; Chen, K.; Bi, Z.; Niu, Q.; Liu, J.; Peng, B.; Zhang, S.; Liu, M.; Li, M.; Pan, X.; et al. Mastering Reinforcement Learning: Foundations, Algorithms, and Real-World Applications. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.xxxxx 2025.

- Schulman, J.; Moritz, P.; Levine, S.; Jordan, M.; Abbeel, P. High-Dimensional Continuous Control Using Generalized Advantage Estimation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1506.02438 2015.

- Hu, E.J.; Shen, Y.; Wallis, P.; Allen-Zhu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, W. LoRA: Low-Rank Adaptation of Large Language Models. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, C.X.; Bi, Z.; Wang, T.; Liu, M.; Song, X.; Zhang, Y.; Song, J.; Niu, Q.; Peng, B.; Chen, K.; et al. Low-Rank Adaptation for Scalable Large Language Models: A Comprehensive Survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.xxxxx 2025.

- Hou, C.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y. Diffusion Transformer Policy. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.15959 2024.

- Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L. COGAct: A Cognitive Multi-Task Approach for Robot Skill Learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.10314 2024.

- Wang, R.F.; Qu, H.R.; Su, W.H. From sensors to insights: Technological trends in image-based high-throughput plant phenotyping. Smart Agricultural Technology 2025, p. 101257.

- Wang, R.F.; Su, W.H. The application of deep learning in the whole potato production Chain: A Comprehensive review. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.F.; Qin, Y.M.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Xu, M.; Schardong, I.B.; Cui, K. RA-CottNet: A Real-Time High-Precision Deep Learning Model for Cotton Boll and Flower Recognition. AI 2025, 6, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Xi, X.; Wu, A.Q.; Wang, R.F. ToRLNet: A Lightweight Deep Learning Model for Tomato Detection and Quality Assessment Across Ripeness Stages. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huihui, S.; Rui-Feng, W. BMDNet-YOLO: A Lightweight and Robust Model for High-Precision Real-Time Recognition of Blueberry Maturity. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1202. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.F.; Tu, Y.H.; Li, X.C.; Chen, Z.Q.; Zhao, C.T.; Yang, C.; Su, W.H. An Intelligent Robot Based on Optimized YOLOv11l for Weed Control in Lettuce. In Proceedings of the 2025 ASABE Annual International Meeting. American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers, 2025, p. 1.

- Pan, P.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, Z.; Qi, W. Deep learning-based 2-D frequency estimation of multiple sinusoidals. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2021, 33, 5429–5440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, P.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, Z.; Wu, G. Complex-valued frequency estimation network and its applications to superresolution of radar range profiles. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2021, 60, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, P.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, Z.; Fan, S.; Huang, X. TFA-Net: A deep learning-based time-frequency analysis tool. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2022, 34, 9274–9286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Pan, P.; Li, Y.; Guo, R. Efficient off-grid frequency estimation via ADMM with residual shrinkage and learning enhancement. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2025, 224, 112200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, P.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Ye, Y.; He, W.; Zhu, Y.; Guo, R. Interpretable Optimization-Inspired Deep Network for Off-Grid Frequency Estimation. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems; 2025. [Google Scholar]

Figure 2.

Algorithm Architecture. PI-VLA consists of a cognitive–motor synergy (CMS) core with dual discrete and continuous action heads, state prediction, and value estimation. An active uncertainty-resolving decider (AURD) monitors action disagreement and prediction error to trigger closed-loop, interactive replanning.

Figure 2.

Algorithm Architecture. PI-VLA consists of a cognitive–motor synergy (CMS) core with dual discrete and continuous action heads, state prediction, and value estimation. An active uncertainty-resolving decider (AURD) monitors action disagreement and prediction error to trigger closed-loop, interactive replanning.

Figure 5.

Per-task success rate breakdown on the LIBERO Spatial suite. PI-VLA demonstrates consistent improvements across all manipulation tasks.

Figure 5.

Per-task success rate breakdown on the LIBERO Spatial suite. PI-VLA demonstrates consistent improvements across all manipulation tasks.

Figure 6.

Real-world success rate heatmap across different objects (Block, Ball, Rock) and instructions (Away, Left, Right). PI-VLA demonstrates consistent high performance across all evaluated conditions.

Figure 6.

Real-world success rate heatmap across different objects (Block, Ball, Rock) and instructions (Away, Left, Right). PI-VLA demonstrates consistent high performance across all evaluated conditions.

Figure 8.

Robustness degradation under increasing levels of visual distraction. PI-VLA demonstrates superior resilience under extreme symmetry-breaking conditions.

Figure 8.

Robustness degradation under increasing levels of visual distraction. PI-VLA demonstrates superior resilience under extreme symmetry-breaking conditions.

Figure 9.

Cross-dataset generalization matrix illustrating transfer performance across different benchmarks. Diagonal entries correspond to in-distribution evaluation.

Figure 9.

Cross-dataset generalization matrix illustrating transfer performance across different benchmarks. Diagonal entries correspond to in-distribution evaluation.

Figure 11.

Incremental component contribution analysis illustrating how each PI-VLA module improves performance over the baseline.

Figure 11.

Incremental component contribution analysis illustrating how each PI-VLA module improves performance over the baseline.

Figure 12.

Training dynamics of PI-VLA. Left: Loss curves for the three components. Right: Validation success rate over training iterations.

Figure 12.

Training dynamics of PI-VLA. Left: Loss curves for the three components. Right: Validation success rate over training iterations.

Figure 13.

Uncertainty analysis over action horizon steps. The combined uncertainty signal increases with horizon length, enabling adaptive re-planning.

Figure 13.

Uncertainty analysis over action horizon steps. The combined uncertainty signal increases with horizon length, enabling adaptive re-planning.

Figure 14.

Action horizon analysis. Left: Success rate comparison between PI-VLA’s adaptive horizon and fixed-horizon baselines. Right: Distribution of executed action horizons showing AURD’s dynamic adjustment behavior.

Figure 14.

Action horizon analysis. Left: Success rate comparison between PI-VLA’s adaptive horizon and fixed-horizon baselines. Right: Distribution of executed action horizons showing AURD’s dynamic adjustment behavior.

Figure 15.

AURD decision timeline during task execution. The uncertainty signal triggers re-planning when exceeding the high threshold, enabling adaptive behavior in uncertain situations.

Figure 15.

AURD decision timeline during task execution. The uncertainty signal triggers re-planning when exceeding the high threshold, enabling adaptive behavior in uncertain situations.

Figure 16.

Parameter sensitivity analysis for key hyperparameters. Red dashed lines indicate optimal values used in our experiments.

Figure 16.

Parameter sensitivity analysis for key hyperparameters. Red dashed lines indicate optimal values used in our experiments.

Figure 17.

Scalability analysis. Left: Performance vs. number of training demonstrations showing superior data efficiency. Right: Performance vs. model size demonstrating consistent improvements with scale.

Figure 17.

Scalability analysis. Left: Performance vs. number of training demonstrations showing superior data efficiency. Right: Performance vs. model size demonstrating consistent improvements with scale.

Figure 18.

Loss landscape visualization for the three components of the unified training objective. The imitation loss exhibits a smooth, well-behaved landscape, while the reinforcement loss shows more complex structure.

Figure 18.

Loss landscape visualization for the three components of the unified training objective. The imitation loss exhibits a smooth, well-behaved landscape, while the reinforcement loss shows more complex structure.

Table 1.

Success rates (%) on the LIBERO benchmark. Best scores are shown in bold, and second-best results are underlined. Avg. denotes the overall success rate reported on LIBERO (computed as an official aggregate across all tasks rather than a simple arithmetic mean of the four suites).

Table 1.

Success rates (%) on the LIBERO benchmark. Best scores are shown in bold, and second-best results are underlined. Avg. denotes the overall success rate reported on LIBERO (computed as an official aggregate across all tasks rather than a simple arithmetic mean of the four suites).

| Method |

Spatial |

Object |

Goal |

Long |

Avg. |

| Diffusion Policy |

65.2 |

60.1 |

58.7 |

52.3 |

59.1 |

| Octo |

68.9 |

64.3 |

62.5 |

56.8 |

63.1 |

| DiT Policy |

70.5 |

66.7 |

65.2 |

59.4 |

65.5 |

| OpenVLA |

72.1 |

68.5 |

67.8 |

61.9 |

67.6 |

| OpenVLA-OFT |

73.8 |

70.2 |

69.5 |

63.4 |

69.2 |

| EverydayVLA |

74.4 |

67.5 |

64.3 |

54.7 |

65.2 |

| PI-VLA (Ours) |

79.5 |

73.4 |

73.3 |

66.6 |

73.2 |

Table 2.

Real-world in-distribution pick-and-place success rates (%).

Table 2.

Real-world in-distribution pick-and-place success rates (%).

| Method |

Block |

Ball |

Rock |

Avg. |

| Away |

Left |

Right |

Away |

Left |

Right |

Away |

Left |

Right |

| OpenVLA |

80 |

45 |

50 |

75 |

60 |

70 |

70 |

50 |

55 |

61.7 |

| OpenVLA-OFT |

85 |

60 |

65 |

80 |

65 |

75 |

75 |

60 |

65 |

70.0 |

| EverydayVLA |

90 |

80 |

75 |

90 |

85 |

80 |

85 |

80 |

75 |

82.2 |

| PI-VLA (Ours) |

95 |

90 |

85 |

95 |

90 |

85 |

90 |

85 |

80 |

88.3 |

Table 3.

Generalization and robustness evaluation (success rate %).

Table 3.

Generalization and robustness evaluation (success rate %).

| Method |

Unseen Tasks |

Unseen Env. |

Static Dist. |

Dynamic Dist. |

| OpenVLA |

55.2 |

58.7 |

50.1 |

45.3 |

| OpenVLA-OFT |

60.5 |

63.4 |

55.8 |

50.2 |

| EverydayVLA |

65.8 |

68.9 |

64.2 |

63.5 |

| PI-VLA (Ours) |

72.4 |

75.1 |

71.8 |

70.1 |

Table 4.

Ablation study on CMS action heads (LIBERO Spatial, success rate %).

Table 4.

Ablation study on CMS action heads (LIBERO Spatial, success rate %).

| Variant |

Spatial Suite (%) |

| PI-VLA (Full CMS) |

79.5 |

| w/ Discrete-only head |

75.3 |

| w/ Continuous-only head |

73.9 |

Table 5.

Ablation on unified training objective (LIBERO Spatial, success rate %).

Table 5.

Ablation on unified training objective (LIBERO Spatial, success rate %).

| Training Objective Variant |

Spatial Suite (%) |

| Full |

79.5 |

| w/o State Prediction Loss () |

76.8 |

| w/o Reinforcement Loss () |

78.2 |

| Imitation-only ( only) |

74.0 |

Table 6.

Ablation on AURD module (LIBERO Spatial, success rate %).

Table 6.

Ablation on AURD module (LIBERO Spatial, success rate %).

| Execution Strategy |

Spatial Suite (%) |

| PI-VLA (Full with AURD) |

79.5 |

| w/o AURD (Fixed Horizon = 5) |

74.1 |

| Replace AURD with AdaHorizon |

76.4 |

| Replace AURD with ACT (Temporal Ens.) |

73.2 |

Table 7.

Comprehensive ablation incrementally adding PI-VLA components.

Table 7.

Comprehensive ablation incrementally adding PI-VLA components.

| Model Configuration |

Spatial Suite (%) |

| OpenVLA-OFT |

73.8 |

| + Dual-Heads (Discrete + Continuous) |

74.8 |

| + Unified Loss () |

77.1 |

| + AURD (Full PI-VLA) |

79.5 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).