1. Introduction

Over the past two decades, the prevalence of sedentary and office-based work has increased substantially. A Eurostat survey conducted in 2017 reported that 39 % employees in the European Union (EU) perform sedentary work [

1], a trend is expected to continue in the future. Office work is predominately characterised by low-variability activities, including prolonged sitting, often accompanied by static postures [

2]. Prolonged static sitting has been linked to lower back, neck, and shoulder pain, type 2 diabetes, cardiovasclular diseases, obesity, among other adverese health conditions [

2,

3]. Moreover, high job demands combined with low job resources impact office workers’ psychosocial well-being [

4]. The compound effect of these factors contribute to the development of work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WRMDs), stress, depression, and anxiety, which affect 7.4 % of workers in the EU [

5]. WRMDs negatively impact worker productivity, increase absenteeism resulting in increased economic costs and medical burdens for individuals and organizations [

6,

7]. Given their complex, multifactorial nature, the prevention of WRMDs and associated mental health conditions requires goal-oriented strategies that target various factors, including exposure to physical, psychosocial, and environmental risks [

8].

Assessing these occupational risk factors effectively requires a context-aware assessment framework, meaning that it is needed to know which activity the worker is carrying out at any moment throughout the work day. Such contextual information enables the extraction of activity-specific features relevant for characterising occupational risks, such as posture-related indicators during sitting or standing, and gait-related indicators during walking, among others. A suitable approach for adressing this problem is machine learning (ML)-based human activity recognition (HAR). HAR aims to identify human physical activities using sensor or video data [

8,

9]. In office environments, sensor-based HAR is preferable, as video-based methods may compromise worker privacy.

Although several sensor-based HAR datasets have been proposed, many are limited to a small set of highly constrained activities, often exhibiting low inter- and intra-class variability and being recorded over short durations. Moreover, a substantial portion of existing datasets focuses on activities of daily living rather tan office-specific work tasks. As a result, these datasets do not adequately reflect the variability, temporal continuity, and contextual ambiguity ecnoutered in real-world office environments. Furthermore, most available datasets are collected under controlled conditions capturing clearly defined activities, limiting their utility for evaluating model generlisation and robustness in unconstrained, real-world settings. Consequently, there remains a need for datasets that capture realisitic work activities and support the evaluation of ML models under both controlled and real-world conditions.

The presented work addresses this gap by introducing a novel smartphone sensor-based dataset: the PrevOccupAI-HAR dataset. It consists of two labeled sub-datasets: a model development (MD) dataset capturing nine-sub-activities that can be associated to three main activities (sitting, standing, and walking), performed by 20 subjects in a controlled environment, and a model evaluation (MD) dataset comprising six hour-long recordings from 13 subjects performing their daily office work. In addition to the proposed datasets, the current manuscript evaluates how identifiable are each activity in each set. Three ML models, namely k-nearest neighbours (KNN), support vector machine (SVM), and Random Forest (RF) are trained on the MD dataset and subsequently evaluated on the ME dataset to establish a performance baseline and assess differences between activity identification in controlled and unrestricted scenarios.

This study is conducted within the scope of the PrevOccupAI+ project (Prevention of Occupational Disorders in Public Administration based on Artificial Intelligence PLUS), a follow-up to the PrevOccupAI project, which aims to characterise daily working activities, working conditions, and potential risk factors associated to the occupational environment, on an individual and organisational level, within the Public Administration. The project is carried out in cooperation with the Camâra Municipal de Lisboa (Municipality of Lisbon).

2. Related Work

HAR is a complex task influenced by several factors, including the diversity and number of activities under study, the duration of these activities, intersubject variability, since individuals may perform the same activity differently, and intrasubject variability over time. These factors can impact HAR frameworks, often limiting their generalizability [

10]. In the literature, there is often a distinction between basic and complex activities. Basic activities typically involve low/variability movements that can consist of clear, repetitive patterns, making them easier to distinguish. In contrast, complex activities usually consist of compound actions that may include combinations of basic activities, interactions with objects, or sequences of movements, resulting in much higher variability [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16].

Some of the most commonly used datasets for HAR focus on basic activities. Examples include the UCI-HAR [

17], WISDM [

18], MHEALTH [

19], and HARTH [

20] datasets. The UCI-HAR dataset contains data from 30 subjects performing six basic activities: standing, sitting, walking, lying down, and going up and down the stairs. Each activity was recorded for 30 seconds using a smartphone placed at the waist, which collected accelerometer (ACC) and gyroscope (GYR) data. WISDM includes a similar set of activities, except lying down. Data was collected from 29 participants using a smartphone positioned on the leg, recording ACC data for a total of 25 minutes per subject. The MHEALTH dataset also includes these basic activities, with additional movements such as waist bending forward, crouching, and front arm raises, each lasting one minute. Data was collected from ten subjects using multiple wearable sensors, capturing ACC, GYR, and magnetoemter (MAG) data. Finally, the HARTH dataset was collected from 22 adults using two tri-axial ACCs on the right thigh and lower back, with additional video recordings for annotation. It includes twelve labeled activities: sitting, standing, lying, walking, running, stairs (ascending/descending), shuffling (standing with leg movement), cycling (sitting/standing), and transport (sitting/standing). Recordings were conducted in a controlled session of one to two hours per participant and a free-living session of approximately one hour per participant.

Other datasets focus on more complex activities, such as SKODA [

21], PAMAP2 [

22], and REALDISP [

23]. SKODA involves ten activities performed by eight subjects on a car assembly line, with an Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) placed on the back of their hands. The PAMAP2 dataset includes 18 different activities, ranging from sports (e.g., playing football, rope jumping) to household tasks (e.g., computer work, house cleaning), recorded from nine subjects over nearly ten hours. Each subject wore three IMUs: one on the chest, one on the dominant wrist, and one on the dominant ankle. REALDISP features 33 fitness exercises performed by 17 subjects, with data collected using nine IMUs placed on both arms, both legs, and the back.

Despite the wide range of publicly available HAR datasets, from basic activities to complex, multi-component tasks, none specifically captures the activities characteristic of office work. While Kim et al. [

24] proposed a dataset for HAR in office environments, it is limited to a conference room setting and relies solely on ambient sensors, leaving a gap in datasets that capture unrestricted office work in realistic settings. Such data is essential for developing context-aware occupational health assessment systems for office workers. Furthermore, current datasets are collected in controlled environments and used for training and testing HAR models, offering no validation of their performance in unrestricted, real-world settings. Therefore, there is a need for datasets that specifically capture office work tasks and include unrestricted, real-world activities. This work introduces the PrevOccupAI-HAR dataset, which consists of two sub-datasets: one capturing office work activities in a controlled environment, and a second containing full-workday recordings of unrestricted office work tasks.

3. Materials and Methods

The following sections describe the proposed approach for smartphone-based Human Activity Recognition in office environments, including a description of the two acquired labeled datasets. This is followed by an explanation of the applied signal pre-processing and feature extraction pipelines. Finally, three machine learning models, namely KNN, SVM, and RF are trained on the first dataset and subsequently deployed and evaluated on the second. The dataset can be downloaded by requesting access via prevoccupai-har@dfki.de and the utilized Python code base is publicly available at https://github.com/p-probst/PrevOccupAI_HAR_JA.

3.1. Datasets

With the purpose of performing HAR in office environments, two datasets were acquired: (1) a dataset acquired under controlled conditions for ML model development and (2) a dataset acquired in a real-world setting for model evaluation.

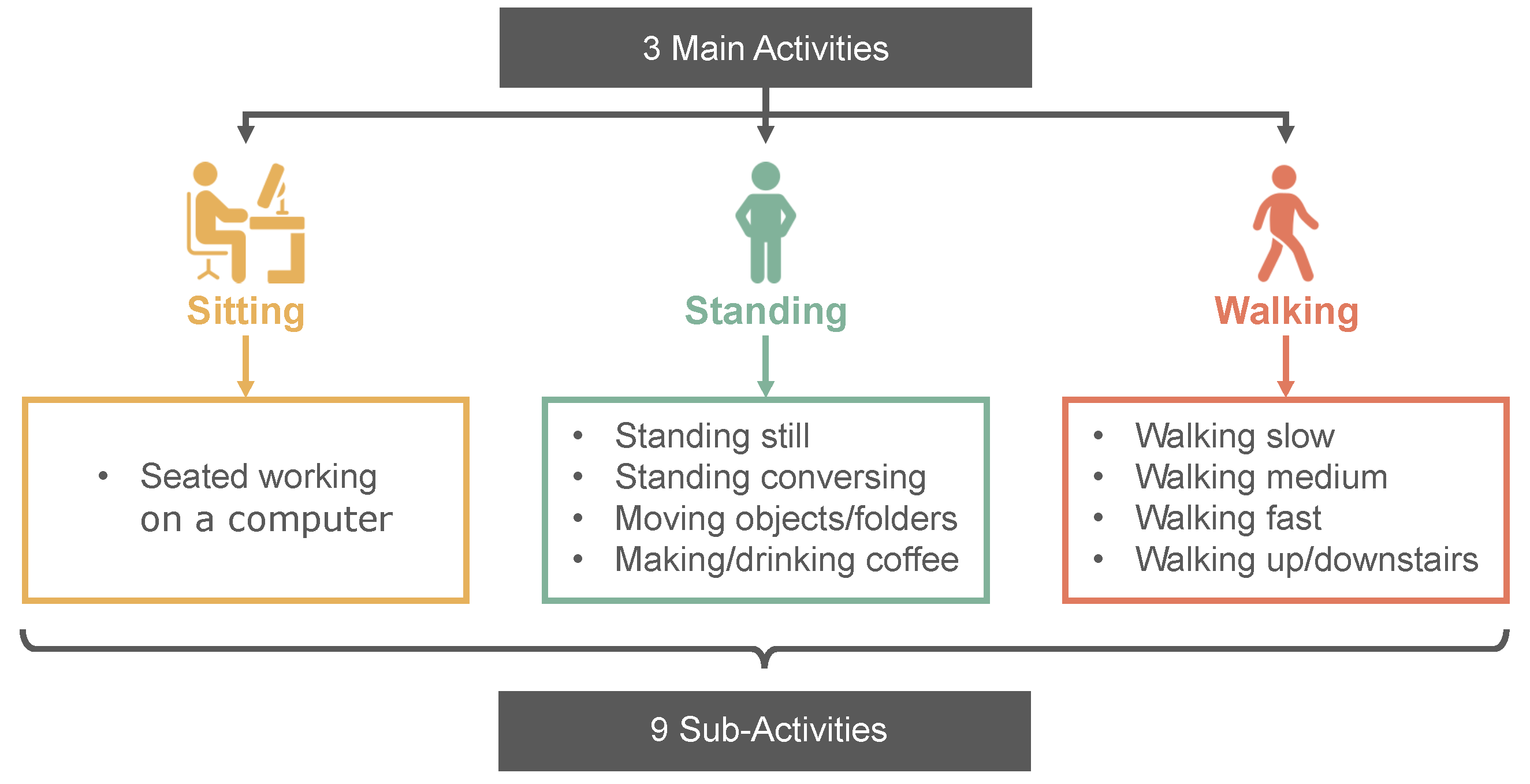

The MD dataset contains data from 20 healthy subjects, comprising of 14 women and six men, aged between 19 and 54 years (27.0 ± 8.7 years). The dataset was acquired on the premises of the NOVA School of Science and Technology, specifically at the LIBPhys Biosignals lab and the surrounding area. The dataset contains nine sub-activities that can be associated to three main activities. This structure was chosen based on hierarchical task analysis [

25], an ergonomic technique that decomposes complex tasks into main activities and their corresponding sub-activities. Following this approach, workers in office settings typically engage in activities associated with sitting, standing, and walking. The corresponding sub-activities were chosen based on common tasks executed in daily office work. For activities associated to standing, four sub-activities were chosen, namely standing still, standing while conversing (i.e., talking with a colleague), making / drinking coffee or tea, and moving objects / folders inside a tall cabinet with objects placed at different levels, ensuring that subjects had to reach up and down. For walking, it was chosen to collect data at different walking speeds. Subjects walked slow, medium (i.e., preferred walking pace), and fast. Additionally, walking stairs up and down was also recorded. Finally, for sitting, standard computer work was chosen. The resulting hierarchical structure is presented in

Figure 1.

The ME dataset comprises of 13 healthy subjects, eight women and five men, aged between 18 and 34 years (24.2 ± 3.7 years). Some of these subjects participated in the data collection for the MD dataset. For this dataset, subjects carried out their daily work tasks for six hours.

The subject details for both datasets, comprising of subject ID, sex, age, and participation in which of the datasets, are described in

Table 1. The presented study was approved by the Universidade Nova de Lisboa Ethics Committee and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants were asked to sign an informed consent after receiving a thorough explanation of the purpose of the study and the acquisition protocol.

3.2. Sensor Setup

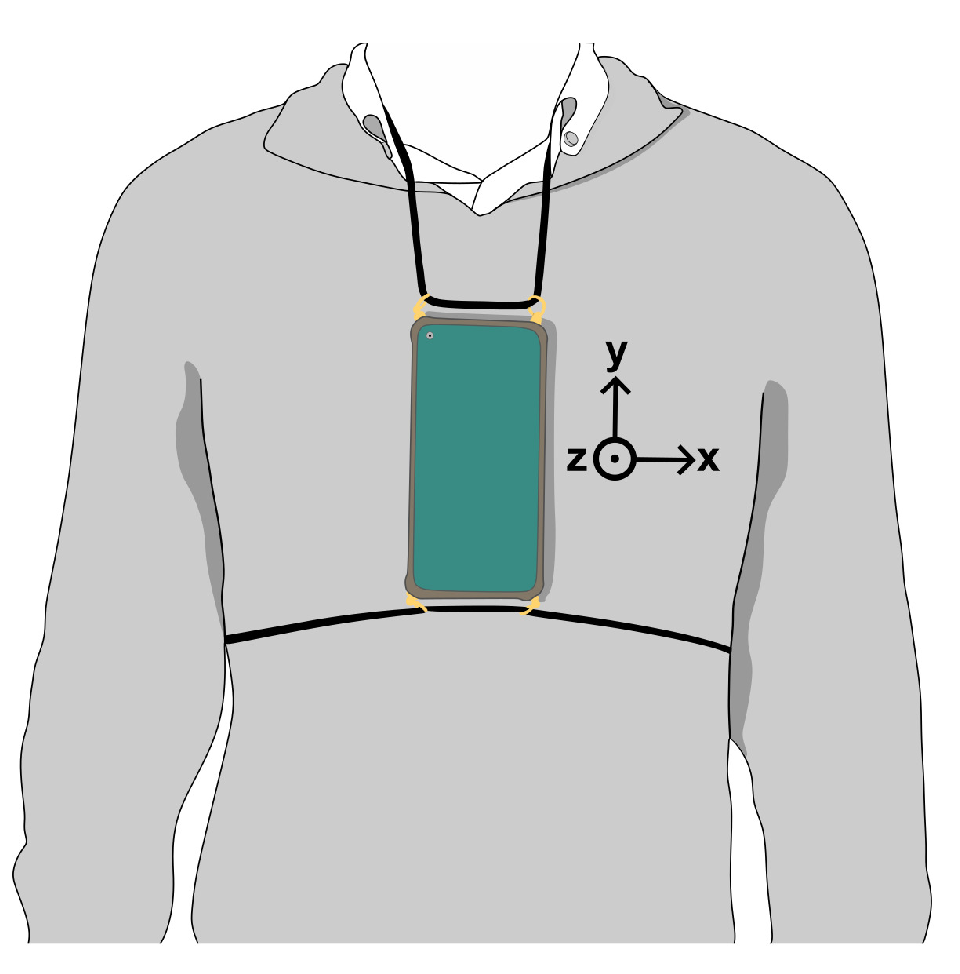

For both datasets, data was acquired using a Xiamoi Redmi Note 9 smartphone that was strapped to the subject’s chest, as shown in

Figure 2. This placement follows the sensor placement setup utilized in the PrevOccupAI project [

26]. The purpose of this placement is two-fold: (1) it allows for tracking human activities and (2) when the subject is seated the trunk movement can be collected, effectively allowing for characterization of seated postures throughout the work day. Additionally, this placement can also be utilized as a proxy for development of sensorised garments.

The utilized smartphone runs on the Android operating system and was used to acquire tri-axial ACC, GYR, and MAG data, as well as rotation vector (ROT) data. Data collection was carried out using the PrevOccupAI application [

27] which allows for acquiring data from the internal smartphone sensors. ACC, GYR, and ROT were acquired at 100 Hz, while MAG was sampled at 50 Hz due to restrictions of Android OS.

3.3. Acquisition Protocol

3.3.1. Model Development Dataset

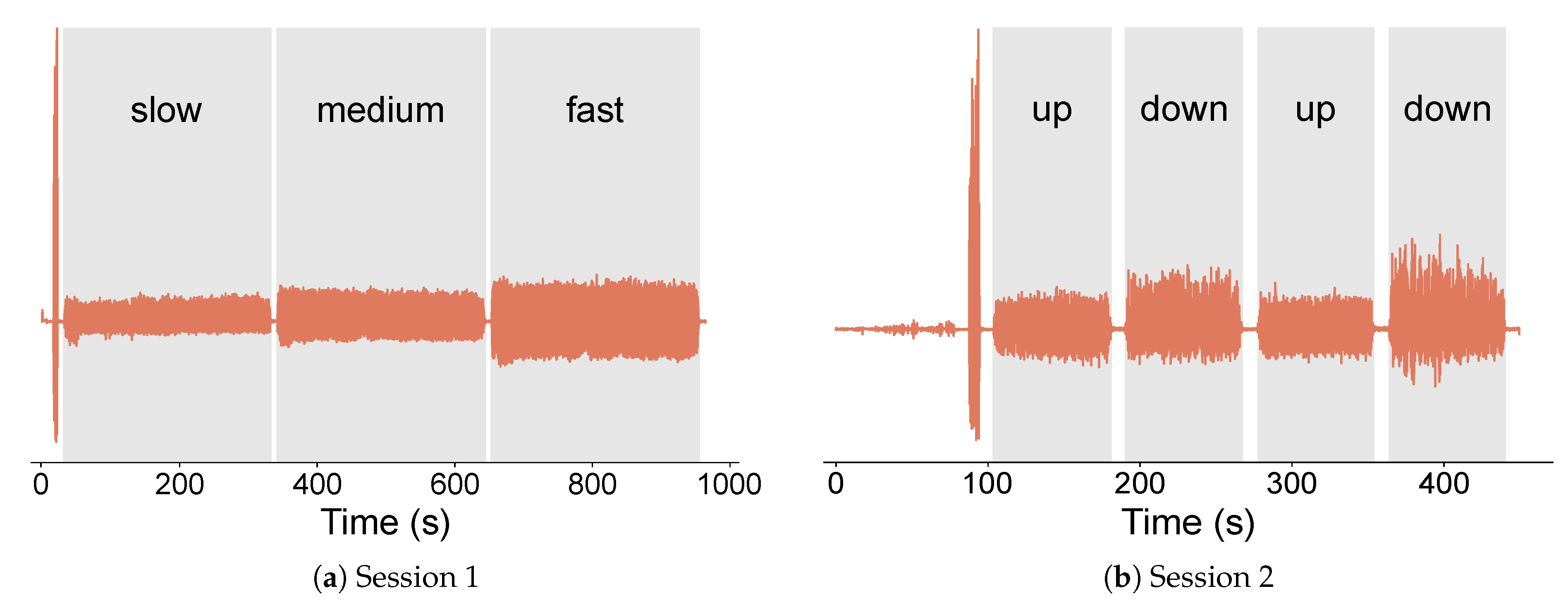

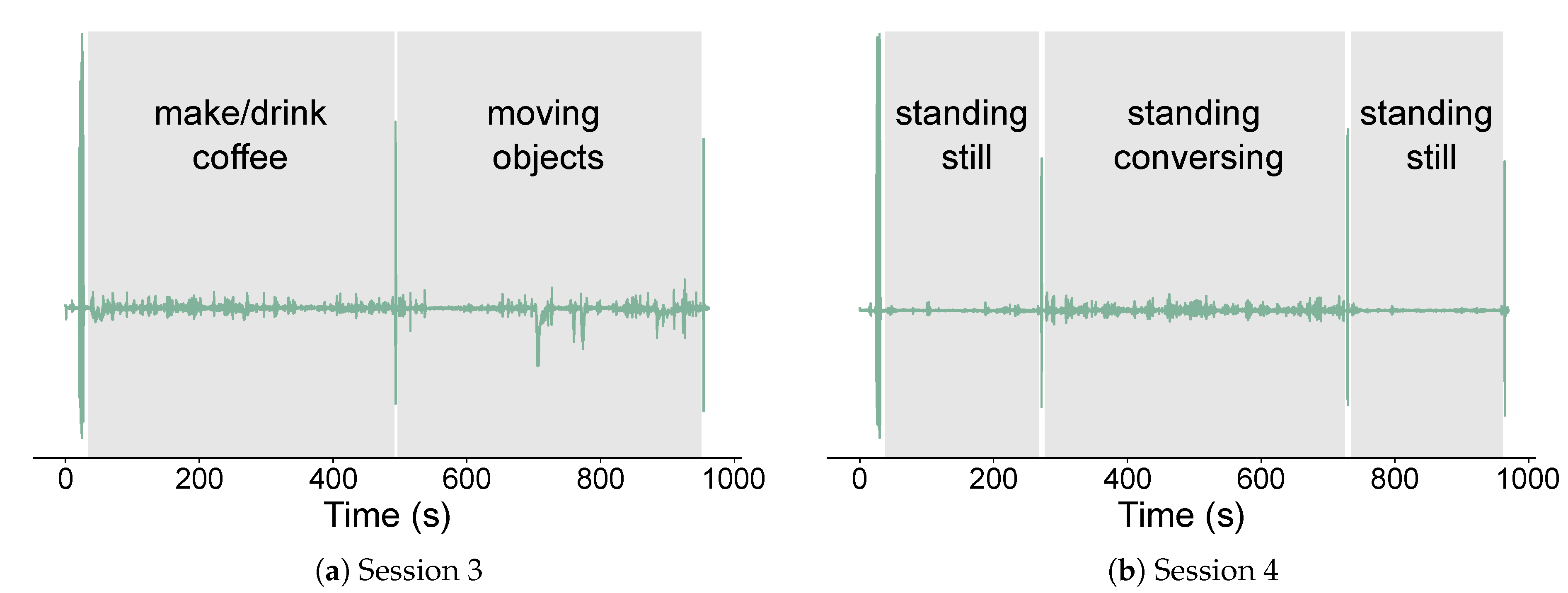

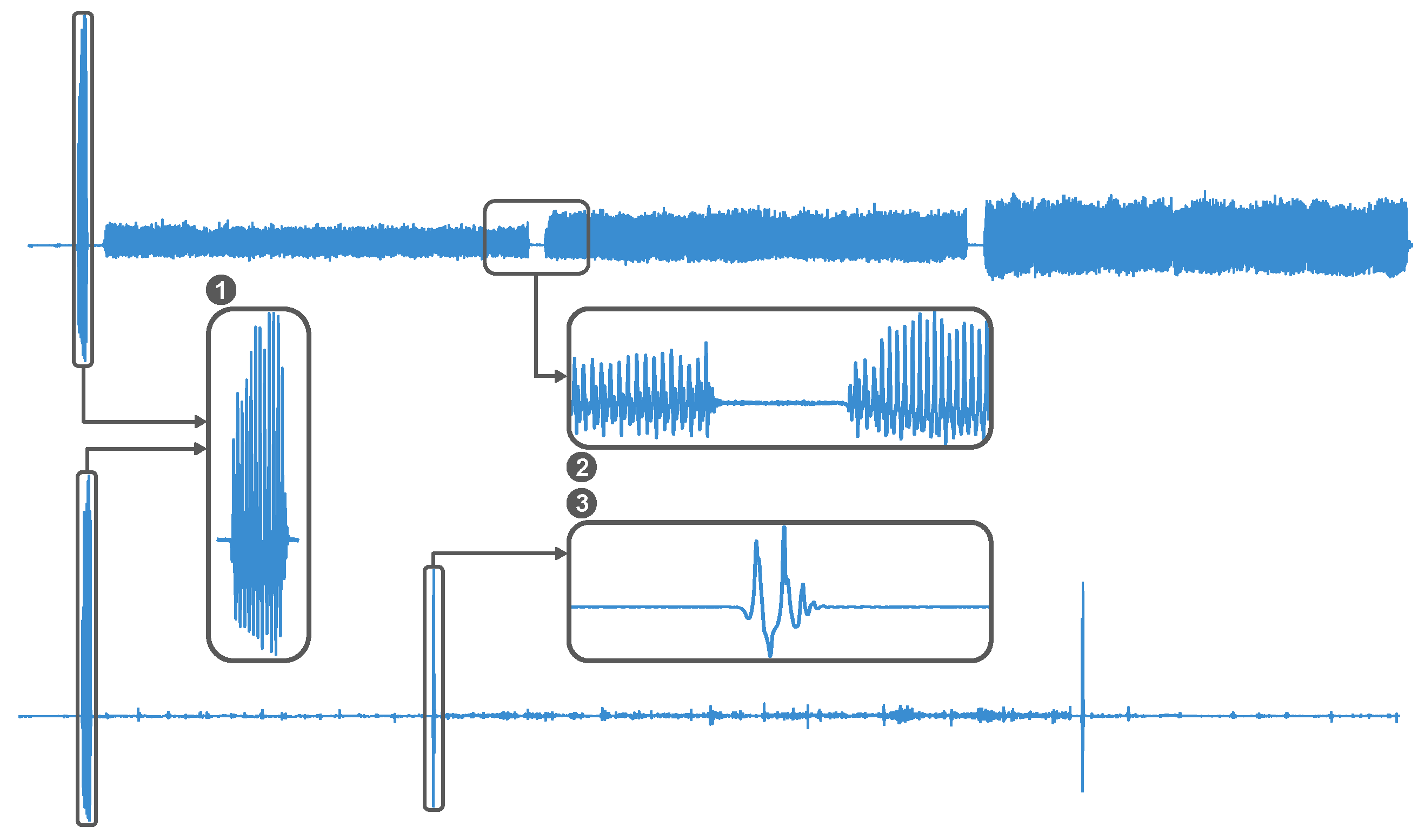

Following HTA, a total of 15 minutes, 30 minutes, and 20 minutes were acquired for sub-activities that can be associated to sitting, standing, and walking, respectively. Similar sub-activities were grouped together to form five separate sessions. Each session included clearly defined sections in which the subject was instructed to perform a specific sub-activity. At the beginning of each recording session, each subject performed roughly ten jumps for synchronization purposes. To facilitate the segmentation of the sub-activities performed in the same recording, short pauses were introduced in between. These pauses were ten-seconds stops (no movement) for activities associated with walking, and ten-seconds stops with a jump in the middle for activities performed while standing. The described segmentation patterns are shown in

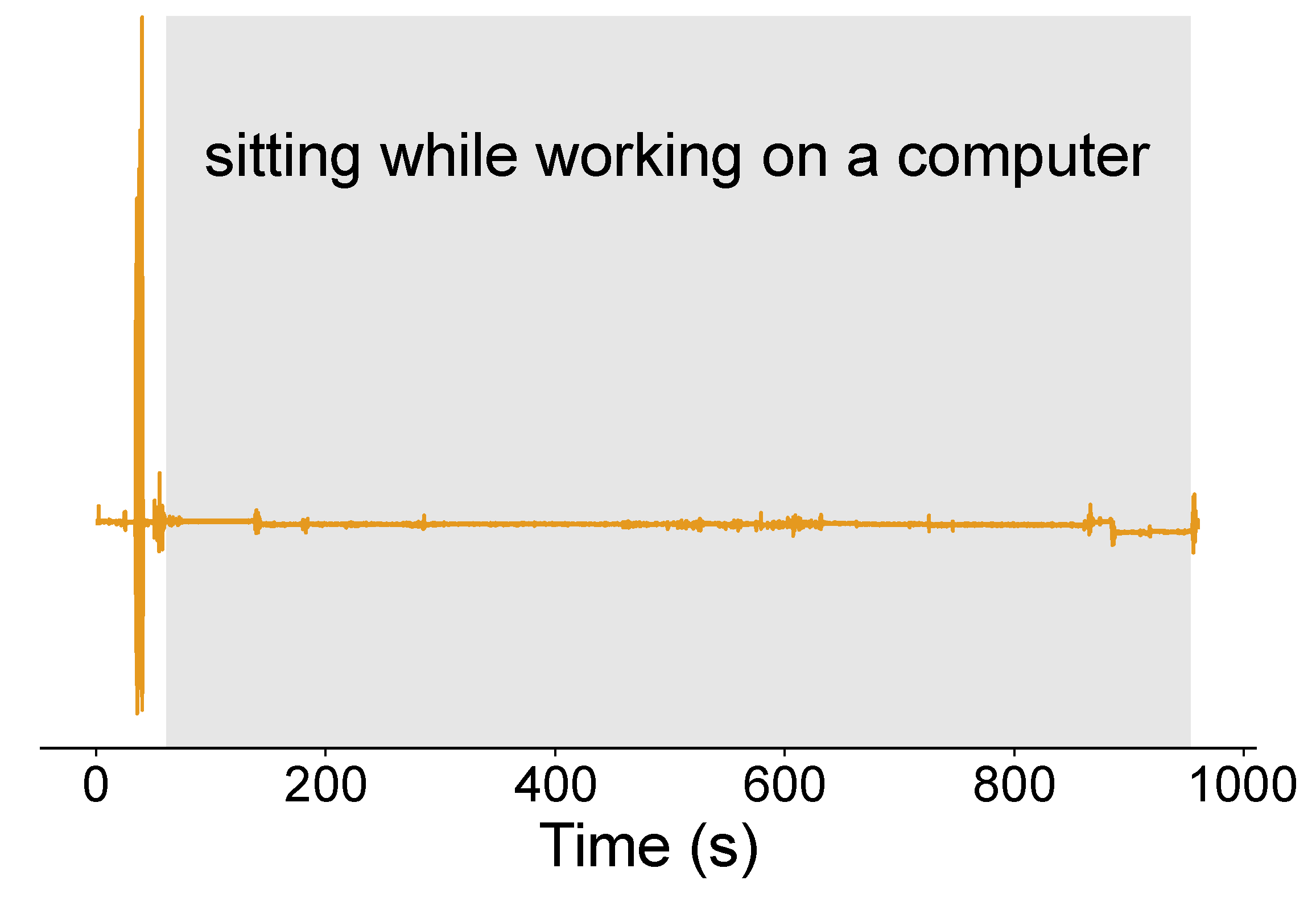

Figure 3 for a walking and a standing-related acquisition. The sitting acquisition was performed continuously.

The first session involved subjects walking at their personal slow, medium, and fast paces. The recordings were performed on even and stable grounds. Each walking speed was acquired for five minutes, totaling 15 minutes. The second session comprised of walking up and down the stairs, alternately, for four segments (two stairs up and two stairs down) of one minute and 15 seconds, totaling five minutes. Some subjects, namely P002, P004, and P007, performed eight segments (four stairs up and four stairs down) of around 35 seconds, due to the acquisition taking place at a shorter staircase. The third session included two standing tasks involving a cabinet, each lasting seven minutes and 30 seconds (for a total of 15 minutes). The first task simulated the preparation and drinking of coffee or tea, while during the second task subjects were asked to organize items like folders, papers, boxes, among others, within the cabinet. The fourth recording consisted of standing still and standing while conversing for seven minutes and 30 seconds each, totaling 15 minutes. The standing still task was divided into two segments for the subjects’ comfort. Subjects were instructed to stand as if they were waiting for an elevator, a colleague, or in front of a conference room. Finally, the fifth session comprised of sitting while working on a computer for 15 minutes. Figures depicting each of the described session are presented in appendix

Figure A1,

Figure A2, and

Figure A3.

3.3.2. Dataset for Model Evaluation in a Real-World Office Setting

No specific instructions were given to the subjects during the data acquisition for the model evaluation dataset, as the purpose was to acquire data in a real-world office environment. Participants were encouraged to carry out their typical daily work tasks while labeling the three main activities: sitting, standing, and walking.

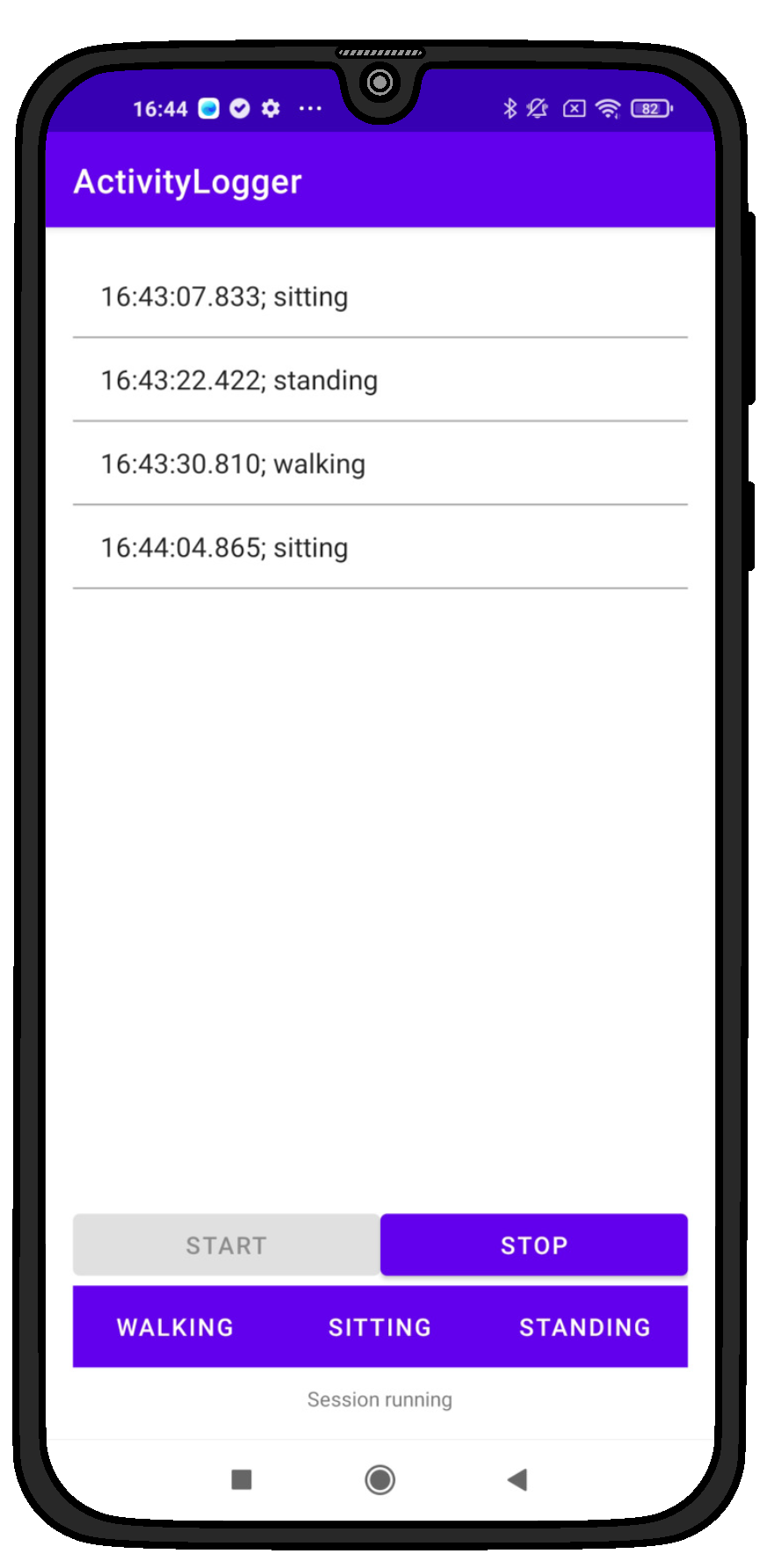

To facilitate the process of annotating/labeling the performed activities throughout the work day, an android application was implemented, as shown in

Figure 4. This application allows for logging the start of an activity. Given that the goal of the proposed models is to classify the main activity (sitting, standing, or walking), regardless of the sub-activity, the application provides three buttons, to indicate which activity is currently being carried out. Once the button has been pressed, the application logs the activity together with the timestamp into a semicolon-separated TXT-file. Additionally the log is also presented in the activity. To provide a high resolution, the timestamp records the hour, minute, second, and millisecond of the button press in the format "HH:MM:SS.ms". Subjects were indicated to press the corresponding activity button once the initiated an activity.

Accounting for delays introduced by participant reaction times during manual labeling, as well as potential omissions or mislabeling events, all generated label files were systematically reviewed and corrected by two independent experts. The correction process involved visual inspection of the activity labels in conjunction with the corresponding sensor signals, with particular emphasis on the y-axis of the accelerometer (ACC) data. Label timestamps were adjusted to align with the estimated onset of each activity. The independently revised label sets were subsequently jointly reviewed by both experts and merged through consensus to produce the final corrected annotation files.

3.4. Data Pre-Processing

3.4.1. Signal Alignment and Resampling

The Android operating system is not optimized for continuous data acquisition, resulting in some inconsistencies during data collection process. These are that the sensors do not start and stop to collect data synchronously, and that they are not acquiring at a fixed sampling rate. To obtain equidistantly and synchronously acquired sensor data, the signals were first cropped to the same length based on the timestamps of the latest starting and earliest stopping sensor and subsequently padded using same-padding, if necessary. Once the sensors have been aligned in time, the data of each sensor were re-sampled to 100 Hz using cubic-spline interpolation for the inertial sensors (ACC, GYR, and MAG) and spherical linear interpolation (SLERP) for the rotation vector data.

3.4.2. Task Segmentation for Model Development Dataset

Since multiple sub-activities were performed in the same recording for the MD dataset, the corresponding tasks needed to be segmented ensuring that each segment only contains data from a single sub-activity. Given the introduction of different segmentation patterns for activities related to walking and standing, two segmentation algorithms based on the ACC y-axis were implemented. Before applying the segmentation pipeline, the synchronization jumps at the beginning of each recording were removed. The signal was then pre-processed using the pre-processing scheme described in [

28] with some additional steps. This scheme consists of a median filter with a window size of

and a 3rd order butterworth low-pass filter with a cutoff frequency of 20 Hz. Additionally, the signal is then normalized by its maximum value followed by the removal of the gravitational component through subtraction of the low-pass filtered (

) signal.

To extract the sub-activities associated with walking, an onset-based task segmentation approach was implemented. After pre-processing, the signal is rectified and smoothed using a root-mean-square filter () to obtain the signal’s envelope. The signal is then binarized, setting to one the values with an amplitude above the threshold (experimentally found) and below to zero. Finally, The first-order discrete difference is calculated to detect the start and stop points of each walking sub-activity. Resulting segments that are shorter than are discarded to remove falsely detected instances. The signals are then cropped using these indices.

A peak-based approach was used to segment the standing sub-activities. This consists in detecting the jumps performed in between sub-activities using the

findpeaks function from SciPy [

29] with a peak height

and a peak distance of

(two minutes). Since the jump occurs in the middle of the ten-second stop, the peak is approximately centered. Therefore, the start and end of each sub-activity are set to five seconds before and after the peak, respectively. The signals are then cropped using these indices.

For some of the subjects the above-mentioned parameters had to be adapted to obtain a valid segmentation. The used parameters and the corresponding subjects are presented in

Table A1. After segmentation of each sub-activity, the resulting file is labeled accordingly. The utilized naming convention was "{activity}_{sub-activity}" (e.g., "walking_medium") and "{activity}_{sub-activity}_{repetition}" for activities with multiple repetitions, as the walking stairs up/down and standing still (e.g., "stairs_up_1").

3.4.3. Signal Pre-Processing

After segmentation of the sub-activities, each signal was pre-processed. For pre-processing of the inertial sensor data (ACC, GYR, and MAG) the approach described in [

28] is followed, with the additional steps for the ACC as described in

Section 3.4.2. For the ROT data, first non-unit quaternions are removed from the data. These can occur due to inaccuracies in Android sensor readings. The cleaned series is then smoothed using SLERP with a smoothing factor of 0.3 (experimentally found), as described in [

30] and following the implementation offered by The Mathworks Inc [

31]. Using SLERP for smoothing quaternion series is equal to applying a single-pole low-pass filter, where the parameter alpha corresponds to the smoothing factor.

3.5. Feature Extraction

After pre-processing the signals, the data was windowed using a window size of

and an overlap of 50 percent. For each sensor axis 15 features were extracted per window. Feature extraction was performed using the Time Series Feature Extraction Library (TSFEL) [

32]. The TSFEL library allows for extracting features from along three domains, namely spectral, statistical, and temporal. The extracted features with their corresponding domains are presented in

Table 2

Additionally, quaternion-based features were extracted for the rotation vector data. For each window the geodesic distance between all quaternions was calculated and from this the mean distance, standard deviation, and the total distance (sum of geodesic distances) were calculated. Thus a total of 197 features (15 features per sensor axis plus the three quaternion-based features) were extracted for each window.

3.6. Model Development

The supervised ML models used in this study are KNN, SVM, and RF, as these are frequently used for HAR [

13,

17,

20]. The objective of these models is to classify the three main activities (sitting, standing, and walking) regardless of the specific sub-activity being performed. The features for the RF were passed without scaling, while for the KNN and SVM a standard scaler was utilised.

3.6.1. Data Balancing and Train-Test Split

Given that the MD dataset described in

Section 3.3.1, exhibits an imbalanced distribution across the three main activity classes (sitting, standing, and walking), a class balancing procedure was applied prior to model training. Class imbalance can bias the learning process of distance-based and ensemble-based classifiers such as KNN and RF, by favouring majority classes and degrading minority class perfomance. To mitigate this effect and ensure a fair comparison across activity classes, the dataset was balanced through a deterministic sub-sampling procedure applied at the level of the sub-activities. The corresponding algorithm for this process is shown in Algorithm 1.

|

Algorithm 1:Balancing of Main Activity Classes |

|

Input: Subject-by-sub-activity instance matrix

Output: Number of instances to sample per sub-activity for Sit, Stand, and Walk

Compute the minimum number of instances per sub-activity across all subjects:

Determine the minimum available instances among walking sub-activities:

Determine the minimum available instances among standing sub-activities:

Compute total feasible instances per main class:

Select the limiting total number of instances:

Compute instances per sub-activity:

Assign

return

|

After balancing, the data were divided into training and testing sets using a predefined, subject-independent split. All samples from a given subject were assigned exclusively to either the training or testing set, thereby preventing data leakage across splits. Furthermore, none of the subjects included in the ME dataset were present in the training set of the MD dataset, ensuring that the ME dataset represents a completely unseen population when deploying the trained models in the unrestricted real-world scenario. Specifically, subjects ’P001’, ’P002’, ’P005’, ’P012’, and ’P015’ were reserved for the testing set of the MD dataset. This split corresponds to a 70/30 train-test split, comprising 7756 training instances and 3324 testing instances, respectively.

This method provides a randomized train/test split while ensuring that all samples from a given subject are assigned to only one of the sets, thereby preventing data leakage. In this case, 80 % of the subjects were randomly assigned to the training set, and the remaining 20 %, namely subjects ’P001’, ’P002’, ’P016’, and ’P018’, to the test set.

3.6.2. Feature Selection

To reduce the dimensionality of the feature vector, a model agnostic feature selection pipeline was implemented. This pipeline consists of removing (1) low variance features with , (2) features exhibiting a pairwise Pearson’s correlation coefficient of , and (3) selecting the k-best features based on the ANOVA F-value between each feature and the main class labels. To evaluate model performance across different feature set sizes, different values for k were tested, namely .

3.6.3. Hyperparameter Tuning

Hyperparameter tuning was performed via grid search for each of the three ML models and for each of the

k-best feature sets, using a

GroupKFold with

ensuring that samples from the same subject were never distributed across the training and validation folds. Model accuracy was utilised as the optimization criterion. The hyperparameters and corresponding values tested for the KNN, SVM, and RF, are shown in

Table 3. The feature set that resulted in the highest accuracy, along with the corresponding best hyperparameters, were then used to train the models on the training set and evaluate them on the test set using accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score as evaluation metrics.

3.7. Model Evaluation

The trained models were evaluated on the ME dataset, to validate their performance in real-world office settings. The pre-processing pipeline described and windowing, and feature extraction pipeline as for the MD dataset was applied to the entire six hour signal. The models were evaluated subject-wise based on accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score. Subsequently, the mean over all subjects for the respective metrics were calculated.

4. Results

4.1. Model Development Dataset

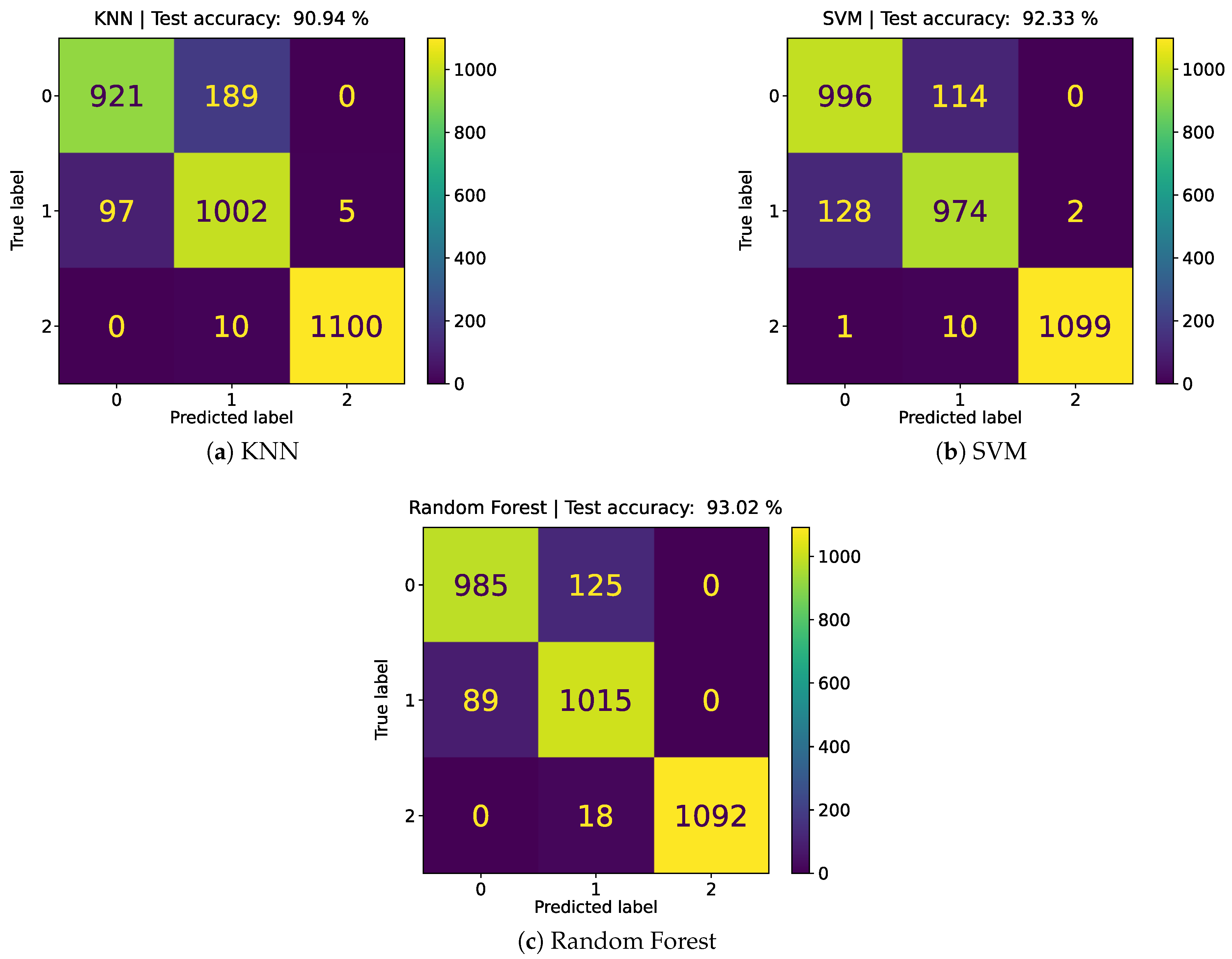

Table 4 shows the best model configurations for KNN, SVM, and RF, along with their corresponding training and testing metrics. Training accuracy is high among all models, with all of them reaching values above 90 %. The RF model reaches a training accuracy of 100 %. With regards to the test accuracy, The RF model achieved the highest test at 93.02 % using 25 features, followed by the SVM with 92.33 % (-0.69 %) using 25 features, and the KNN with 90.94 % (-2.08 %) using 35 features.

Figure 5 shows the confusion matrices for the three models. All models struggled most with distinguishing sitting from standing, with the KNN having the most confusion. Confusion with regards to the walking class is the lowest, with RF exhibiting the most misclassified instances.

4.2. Model Evaluation Dataset

The models achieving the highest performance on the development dataset were subsequently deployed on the ME dataset to evaluate their performance in real-world settings. Subject-specific results as well as overall mean and standard deviation are shown in

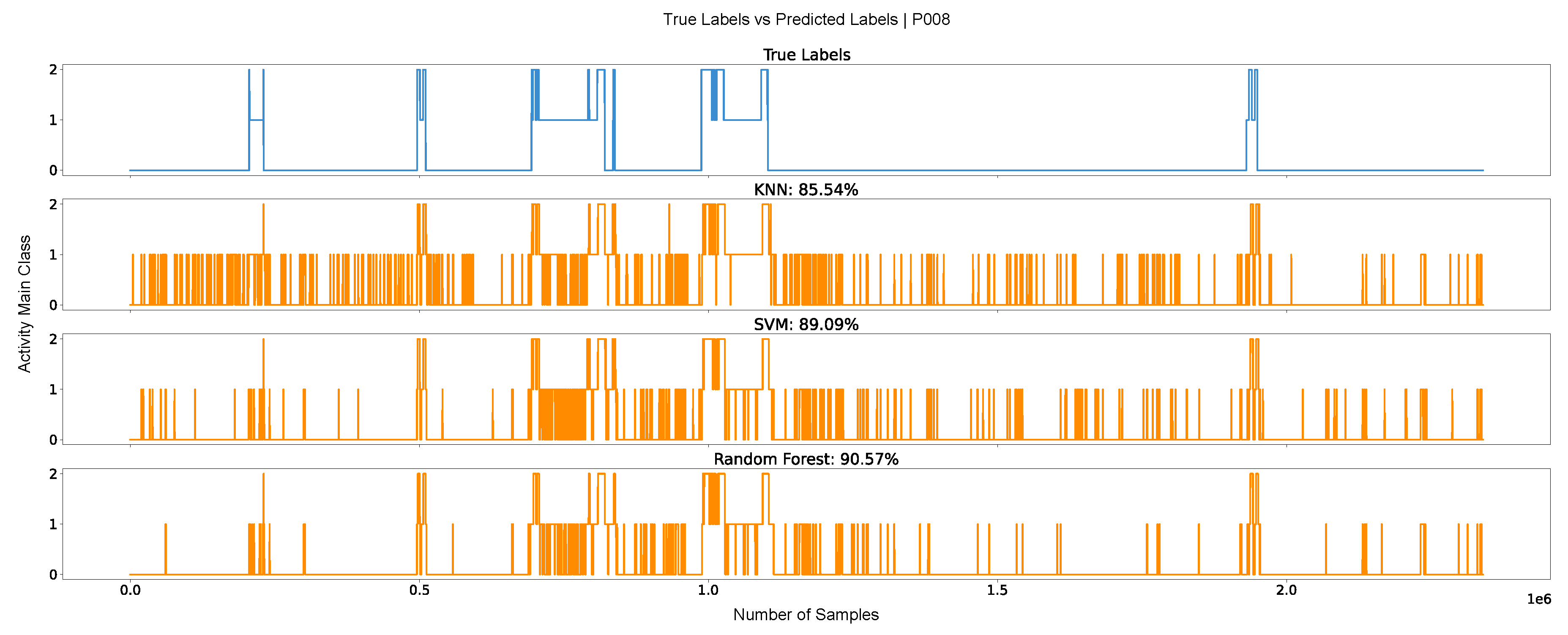

Table 5. In this dataset, all three models decreased in accuracy with the KNN exhibiting the largest drop (-21.62 %), followed by the RF (-14.21 %), and the SVM (-12.90 %). Given this, the SVM achieved the highest accuracy of 79.43 %, followed by the RF with 77.81 %, and finally the KNN with 69.32 %. The standard deviations for the KNN, SVM, and RF were 10.21 %, 5.84 %, and 7.50 %, respectively. To better understand model behavior when classifying real-world, six-hour recordings, plots were generated for each subject, displaying the true labels over time alongside the predictions from the three models.

Figure 6 shows this plot for the subject with the highest overall accuracy (P008). As shown, the classifiers frequently introduced brief misclassifications between sitting and standing, resulting in an jittery output. This behaviour can be observed among all subjects in the ME dataset.

5. Discussion

As shown in

Table 4, all three classification models demonstrate good performance on the MD dataset. Based on the metrics for the training and testing sets, there is no indication of substantial overfitting. Moreover, the similarity across the four evaluation metrics indicates that the models do not favor any particular class, which is expected given that this dataset was previously balanced. From the confusion matrices in

Figure 5, it can be concluded that misclassifications mostly occurs between the sitting and standing classes. These activities involve minimal movement, particularly sitting and standing still, and are therefore harder to distinguish from each other compared to more dynamic activities like walking. With the smartphone positioned on the chest, the accelerometer signals for sitting and standing can be very similar, leading to overlapping feature representations. Some walking instances were also misclassified as standing and vice versa, particularly in the KNN and RF models. This is likely due to standing activities that involve trunk movement, such as conversing or reaching into a tall cabinet, which in some instances can exhibit cyclic patterns that can resemble walking in the sensor data.

Regarding the results of the KNN, SVM, and RF on the real-world (ME) dataset, there was an overall decrease in performance, as depicted in

Table 5. These results show that, although models often achieve high performance on balanced and lab-collected datasets, such as the MD dataset, their ability to identify activities decreases considerably when applied to real-world, full-day recordings. In real-world settings where subjects are not restricted in their activities and recordings are long in duration, intra- and inter-subject variability increases, which can lead to confusion in the models. In this dataset, KNN remains the worst-performing model, while SVM now outperforms RF. However, when evaluating the results on a subject-basis, RF sometimes outperforms the SVM. Several factors may explain this shift. The SVM may achieve better generalization than the RF, resulting in higher results in real-world conditions. Additionally, the features that were informative for the RF on the MD dataset may not have the same relevance in the ME dataset. Analyzing the SDs, these being relatively high, indicate that the models perform better on some subjects, likely those with more static behaviors and lower variability in their movements. Finally, Traditional ML metrics can be insufficient for evaluating models in HAR, as illustrated by the jittery plots in

Figure 6. Although Subject P008 shows high overall accuracy, the models fail to correctly identify continuous segments of the same activity, particularly sitting and standing. This issue arises not only because these activities are commonly confused, as shown in the confusion matrices, but also because the KNN, SVM, and RF models do not take into account the temporal dimension of the signals.

The performance patterns observed in both datasets provide indirect evidence for the quality and reliability of the collected data and labeling process. The high performance on the MD dataset indicates that the controlled acquisition and the corresponding labels resulting from the segmentation process are sufficiently informative for discriminating among the main activity classes. Similarly, although some performance degradation can be observed on the ME dataset, the models’ ability to correctly identify the majority of activities, suggests that the real-world recordings were accurately labeled and reflect the variability of office work tasks. These observations support the validity of the dataset for office-based HAR.

For future work, models that account for the temporal structure of the signals, such as Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, should be considered for HAR, particularly when aiming to apply these models in real-world scenarios like office environments. Additionally, post-processing methods could be explored to refine and correct the models’ predictions.

6. Conclusions

This article introduces PrevOccupAI-HAR a new publicly available dataset for smartphone-based HAR in office environments. The dataset consists of a dataset for model development, collected under controlled conditions, comprising from data of 20 subjects performing nine sub-activities that can be associated to three main-activities: sitting, standing, and walking. Additionally a dataset for model evaluation collected in a real-world office setting in which 13 subjects are recorded for six hours while performing their daily office work. Three ML models, namely Random Forest, SVM, and KNN, were trained on the model development dataset with the objective of classifying the three main activities regardless of the sub-activity. The models were subsequently deployed and evaluated on the real-world dataset. Test accuracies on the model development dataset reached 90.94 %, 92.33 %, and 93.02 % for the KNN, SVM, and Random Forest, respectively. When deploying the models on the real-world dataset, obtained mean accuracies were 69.32 % (-21.62 %) for the KNN, 79.43 % (-12.90 %) for the SVM, and 78.81 % (-14.21 %) for the Random Forest. Inspection of the sequential output of the models on the real-world dataset revealed that all models frequently introduce brief misclassifications, mostly between sitting and standing classes, resulting in a jittery output. The main focus of future work should be to improve model performance making them more accurate and consistent in their prediction over time. This could be tackled by either employing models that account for the temporal structure of the data, such as LSTMs or developing post-processing algorithms to improve model output.

Acknowledgments

This research was partly supported by the Science and Technology Foundation (FCT) under the project PrevOccupAI+ (2024.07630.IACDC). P. Probst was supported by the doctoral grant RT/BD/152843/2021 financed by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT), and with funds from State Budget, under the MIT Portugal Program.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| WRMDs |

Work-related musculoskeletal disorders |

| HAR |

Human activity recognition |

| ML |

Machine learning |

| MD |

Model development |

| ME |

Model evaluation |

| KNN |

k-Nearest Neighbor |

| SVM |

Support Vector Machine |

| RF |

Random Forest |

| ACC |

Accelerometer |

| GYR |

Gyroscope |

| MAG |

Magnetometer |

| ROT |

Rotation Vector |

| SLERP |

Spherical linear interpolation |

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Recording sessions for activities related to walking (a) Session 1: walking at three different paces. (b) Session 2: ascending and descending stairs.

Figure A1.

Recording sessions for activities related to walking (a) Session 1: walking at three different paces. (b) Session 2: ascending and descending stairs.

Figure A2.

Recording sessions for activities related to standing (a) Session 3: preparing coffee and moving objects in a cabinet. (b) Session 4: standing still and standing while conversing.

Figure A2.

Recording sessions for activities related to standing (a) Session 3: preparing coffee and moving objects in a cabinet. (b) Session 4: standing still and standing while conversing.

Figure A3.

Session 5: sitting while working on a computer.

Figure A3.

Session 5: sitting while working on a computer.

Table A1.

Chosen parameters for activity segmentation within the MD dataset.

Table A1.

Chosen parameters for activity segmentation within the MD dataset.

| Subject ID |

|

|

|

| P009 |

100 |

0.5 |

120 s |

| P012, P015, P017, P020 |

300 |

0.4 |

120 s |

| P019 |

100 |

0.35 |

60 s |

| All other |

100 |

0.4 |

120 s |

Table A2.

Optimized feature sets obtained from the MD dataset for each model.

Table A2.

Optimized feature sets obtained from the MD dataset for each model.

| Domain |

KNN |

SVM |

Random Forest |

| Spectral |

x-ACC Median frequency

x-ACC Power bandwidth

y-ACC Max. Power Spectrum

y-ACC Power bandwidth

z-ACC Median frequency

x-GYR Power bandwidth

x-GYR Median frequency

y-GYR Median frequency

y-GYR Power bandwidth

z-GYR Median frequency

z-GYR Power bandwidth

x-MAG Power bandwidth

y-MAG Power bandwidth

z-MAG Power bandwidth |

x-ACC Median frequency

y-ACC Power bandwidth

z-ACC Median frequency

x-GYR Median frequency

y-GYR Median frequency

y-GYR Power bandwidth

z-GYR Median frequency

z-GYR Power bandwidth

x-MAG Power bandwidth

y-MAG Power bandwidth

z-MAG Power bandwidth |

x-ACC Median frequency

y-ACC Power bandwidth

z-ACC Median frequency

x-GYR Median frequency

y-GYR Median frequency

y-GYR Power bandwidth

z-GYR Median frequency

z-GYR Power bandwidth

x-MAG Power bandwidth

y-MAG Power bandwidth

z-MAG Power bandwidth |

| Statistical |

x-ACC Interquartile range

y-ACC Interquartile range

y-ACC Max.

z-ACC Interquartile range

z-ACC Max.

z-ACC Min.

x-GYR Max.

x-GYR Min.

y-GYR Interquartile range

y-GYR Max.

y-GYR Min.

z-GYR Min.

x-MAG Interquartile range

y-MAG Interquartile range

z-MAG Interquartile range

y-ROT Mean |

x-ACC Interquartile range

y-ACC Interquartile range

y-ACC Max.

z-ACC Interquartile range

z-ACC Max.

z-ACC Min.

x-GYR Max.

x-GYR Min.

y-GYR Interquartile range

y-GYR Max.

y-GYR Min.

z-GYR Min.

x-MAG Interquartile range

z-MAG Interquartile range |

x-ACC Interquartile range

y-ACC Interquartile range

y-ACC Max.

z-ACC Interquartile range

z-ACC Max.

z-ACC Min.

x-GYR Max.

x-GYR Min.

y-GYR Interquartile range

y-GYR Max.

y-GYR Min.

z-GYR Min.

x-MAG Interquartile range

z-MAG Interquartile range |

| Temporal |

— |

— |

— |

| Quaternion |

— |

— |

— |

References

- Eurostat. Sit at work? You are one of 39%. 2019. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/ddn-20190305-1 (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Peereboom, K.; de Langen, N.; Bortkiewicz, A.; Copsey, S. Prolonged static sitting at work: Health effects and good practice advice. Executive summary. Technical report, European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA), Luxembourg, 2021. Available online: https://osha.europa.eu/sites/default/files/Sitting_at_work_%20summary_EN.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Owen, N.; Healy, G.N.; Dempsey, P.C.; Salmon, J.; Timperio, A.; Clark, B.K.; Goode, A.D.; Koorts, H.; Ridgers, N.D.; Hadgraft, N.T.; et al. Sedentary behavior and public health: integrating the evidence and identifying potential solutions. Annual review of public health 2020, 41, 265–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A.B.; De Vries, J.D. Job Demands–Resources theory and self-regulation: New explanations and remedies for job burnout. Anxiety, stress, & coping 2021, 34, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA). Estimating the cost of work-related accidents and ill-health. Technical report, European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA), Luxembourg, 2019. Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/2d75613d-1878-11e9-8d04-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Punnett, L.; Wegman, D.H. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders: the epidemiologic evidence and the debate. Journal of electromyography and kinesiology 2004, 14, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA). Work-related musculoskeletal disorders. Technical report, European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA), Luxembourg, 2020. Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/5819be4f-0393-11eb-a511-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Langella, F.; Christensen, S.W.M.; Palsson, T.S.; Høgh, M.; Gagni, N.; Bellosta-López, P.; Christiansen, D.H.; Delle Chiaie, M.; Domenéch-García, V.; Johnston, V.; et al. Development of the Prevent for Work questionnaire (P4Wq) for assessment of musculoskeletal risk in the workplace: part 1—literature review and domains selection. BMJ open 2021, 11, e043800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De-La-Hoz-Franco, E.; Ariza-Colpas, P.; Quero, J.M.; Espinilla, M. Sensor-based datasets for human activity recognition–a systematic review of literature. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 59192–59210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Zhao, S.; Zheng, C.; Chen, H.; Liu, L.; Chen, G. HierHAR: Sensor-Based Data-Driven Hierarchical Human Activity Recognition. IEEE Sensors Journal 2021, 21, 3353–3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dentamaro, V.; Gattulli, V.; Impedovo, D.; Manca, F. Human activity recognition with smartphone-integrated sensors: A survey. Expert Systems with Applications 2024, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ige, A.O.; Mohd Noor, M.H. A survey on unsupervised learning for wearable sensor-based activity recognition. Applied Soft Computing 2022, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.A.; Le-Khac, N.A. Sok: Behind the accuracy of complex human activity recognition using deep learning. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), 2024; IEEE; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara, O.D.; Labrador, M.A. A Survey on Human Activity Recognition using Wearable Sensors. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2013, 15, 1192–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omolaja, A.; Otebolaku, A.; Alfoudi, A. Context-Aware Complex Human Activity Recognition Using Hybrid Deep Learning Models. Applied Sciences 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Rani, V.; Kumar, M. Human activity recognition: A comprehensive review. Expert Systems 2024, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguita, D.; Ghio, A.; Oneto, L.; Parra, X.; Reyes-Ortiz, J.L. A Public Domain Dataset for Human Activity Recognition using Smartphones. In Proceedings of the The European Symposium on Artificial Neural Networks, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kwapisz, J.R.; Weiss, G.M.; Moore, S.A. Activity recognition using cell phone accelerometers. SIGKDD Explor. Newsl. 2011, 12, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banos, O.; Garcia, R.; Holgado-Terriza, J.A.; Damas, M.; Pomares, H.; Rojas, I.; Saez, A.; Villalonga, C. mHealthDroid: A Novel Framework for Agile Development of Mobile Health Applications. In Proceedings of the Ambient Assisted Living and Daily Activities; Springer International Publishing, 2014; pp. 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logacjov, A.; Bach, K.; Kongsvold, A.; Bårdstu, H.B.; Mork, P.J. HARTH: A Human Activity Recognition Dataset for Machine Learning. Sensors 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stiefmeier, T.; Roggen, D.; Ogris, G.; Lukowicz, P.; Tröster, G. Wearable Activity Tracking in Car Manufacturing. IEEE Pervasive Computing 2008, 7, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiss, A.; Stricker, D. Introducing a New Benchmarked Dataset for Activity Monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2012 16th International Symposium on Wearable Computers, 2012; pp. 108–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baños, O.; Damas, M.; Pomares, H.; Rojas, I.; Tóth, M.A.; Amft, O. A benchmark dataset to evaluate sensor displacement in activity recognition. In Proceedings of the 2012 ACM Conference on Ubiquitous Computing, 2012; Association for Computing Machinery; pp. 1026–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kim, G.; Lee, T.; Kim, K.; Lee, D. A dataset of ambient sensors in a meeting room for activity recognition. Scientific Data 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanton, N.A. Hierarchical task analysis: Developments, applications, and extensions. Applied Ergonomics 2006, 37, 55–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliosi, E.; Probst, P.; Rodrigues, J.; Silva, L.; Zagalo, D.; Cepeda, C.; Gamboa, H. Week-long Multimodal Data Acquisition of Occupational Risk Factors in Public Administration Workers. In Proceedings of the 2023 19th International Conference on Intelligent Environments, IE 2023 - Proceedings. IEEE, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva., S.; Cepeda., C.; Rodrigues., J.; Probst., P.; Gamboa, H. Assessing Occupational Health with a Cross-platform Application based on Self-reports and Biosignals. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 15th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2022) - HEALTHINF. INSTICC, SciTePress, 2022; pp. 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguita, D.; Ghio, A.; Oneto, L.; Parra, X.; Reyes-Ortiz, J.L. A Public Domain Dataset for Human Activity Recognition Using Smartphones. In Proceedings of the ESANN 2013 proceedings, European Symposium on Artificial Neural Networks, Computational Intelligence and Machine Learning, Bruges (Belgium), 2013; Available online: https://i6doc.com.

- Virtanen, P.; Gommers, R.; Oliphant, T.E.; Haberland, M.; Reddy, T.; Cournapeau, D.; Burovski, E.; Peterson, P.; Weckesser, W.; Bright, J.; et al. SciPy 1.0: Fundamental Algorithms for Scientific Computing in Python. Nature Methods 2020, 17, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoemake, K. Animating rotation with quaternion curves. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 12th annual conference on Computer graphics and interactive techniques, 1985; pp. 245–254. [Google Scholar]

- The MathWorks; Inc. Lowpass Filter Orientation Using Quaternion SLERP. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Barandas, M.; Folgado, D.; Fernandes, L.; Santos, S.; Abreu, M.; Bota, P.; Liu, H.; Schultz, T.; Gamboa, H. TSFEL: Time Series Feature Extraction Library. SoftwareX 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).