Submitted:

08 January 2026

Posted:

09 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- 1.

- An end-to-end specification of an email–OTP access gate with endpoint-specific, multi-key rate limiting in a low-code orchestration setting.

- 2.

- A platform-oriented threat model emphasizing low-code integrity risks and connector/webhook security.

- 3.

- Security-critical implementation guidance: CSPRNG; HMAC verifiers with explicit context; constant-time compare; TTL/attempt limits; atomic OTP rotation; session fixation and CSRF defenses; key management and rotation.

- 4.

- Standardized pseudo-code and configuration templates.

- 5.

- Vendor-agnostic platform validation checklists and a replay-resistant external state-store pattern with monotonic signed transitions and revocation semantics.

- 6.

2. Background, Standards, and Related Work

2.1. Lightweight Access Gates and Alternatives

- Magic links: signed, single-use URLs with short TTL (similar security envelope to email OTP but different UX and replay considerations).

- TOTP apps: stronger than mailbox-control if the shared secret is protected and phishing is mitigated; standardized in RFC 6238 [8].

- WebAuthn/passkeys: phishing-resistant public-key credentials for web applications [16].

2.2. Identity Assurance and Best-Practice Guidance

2.3. Rate Limiting

2.4. Continuous Human Verification and Greylisting

2.5. Enterprise RAG Frameworks and Measurements in the Wild

2.6. Low-Code Orchestration and LLM Security Posture

2.7. Privacy and Governance

3. Threat Model and Assumptions

3.1. Assets

3.2. Adversaries

- perform OTP spraying (high-volume OTP requests across many emails),

- attempt online guessing of OTPs under rate limits,

- enumerate allowlists via errors, timing, or deliverability side channels,

- exploit NAT/VPN/rotating IPs to evade simplistic limiters,

- attempt session fixation or replay across tabs/devices,

- target webhooks/connectors (credential theft, replay, SSRF-like egress abuse),

- inject adversarial content (prompt injection) to subvert downstream tools.

3.3. Trust Anchors and Validation

4. System Overview

4.1. Workflow Stages

- 1.

- Rate limiting: endpoint-specific token buckets composed across session/user id, email, and IP.

- 2.

- Authentication check: if session is authenticated and TTL-valid, route to chat.

- 3.

- OTP issuance: if an eligible email is provided, issue OTP and store only a verifier.

- 4.

- OTP submission: validate OTP under TTL/attempt caps; set authenticated state on success.

- 5.

- Post-auth routing: forward prompts to the LLM via a gateway and enforce downstream guardrails.

4.2. State Variables

-

Session: session_id, auth_state, session_issued_at,session_expires_at, session_version, session_kid

-

OTP: otp_email, otp_nonce, otp_verifier,otp_issued_at, otp_attempts, otp_kid

- Operational: reject_reason (safe user-facing), structured audit logs (server-side), and optional greylist_until.

4.3. Control Flow Protocol

- 1.

- Determine endpoint type: request-OTP, submit-OTP, or post-auth chat.

- 2.

- Apply endpoint-specific multi-key rate limiting (Section 7). If blocked, return a uniform message.

- 3.

- If auth_state=1 and session TTL valid, route message to LLM (with downstream guardrails).

- 4.

- Else if message is an eligible email, issue OTP (store verifier, send email) subject to greylisting checks.

- 5.

- Else if message is an OTP submission, validate (TTL + attempts + constant-time verifier compare + binding).

- 6.

- Else return a uniform guidance message (do not reveal allowlist membership or email existence).

5. Security-Critical Implementation Details

5.1. OTP Generation and Parameters

5.2. CSPRNG Requirement

5.3. Hashed-at-Rest Verifier with Explicit Context (Domain Separation)

5.4. Constant-Time Comparison

5.5. Key Management, Rotation, and Binding to kid

5.6. Key-Compromise Resilience and Offline-Verification Risk

- Prefer non-exportable keys: keep inside a KMS/HSM/TEE and invoke HMAC via an authenticated API (rate-limited and audited). Non-exportability reduces the feasibility of large offline guessing even if the OTP state store is exposed.

- Minimize verifier exposure: store OTP state in a dedicated backend store with least privilege; never log otp_nonce or otp_verifier; delete records on success and after TTL+grace. Treat access to OTP state as sensitive as access to session cookies.

- Increase brute-force cost when needed: enlarge N (e.g., 8 digits or short alphanumeric), shorten TTL, and reduce attempt caps for higher-stakes contexts.

- Key separation: derive purpose-specific keys (OTP verifiers vs. session assertions vs. rate-limit keyed hashes) using HKDF to avoid cross-protocol key reuse [33].

5.7. Binding, Atomic Rotation, and Concurrency

5.8. TTL, Attempt Caps, Cooldown, One-Time Use

5.9. Email Parsing, Canonicalization, and Allowlist Correctness

- Enforce allowlists via exact domain match, unless policy explicitly allows subdomains.

5.10. Shared Mailboxes, Role Accounts, and Forwarding Aliases

- Define eligible mailbox types: personal staff/student accounts where a single person is accountable for mailbox access.

- Maintain a denylist for non-person entities: (i) known role accounts, (ii) shared mailboxes, and (iii) distribution lists. A conservative default is to deny addresses whose local-part matches common role patterns (e.g., admin, support, help, noreply) unless explicitly excepted.

- Prefer directory-backed validation when available: if the institution has an identity directory export (LDAP/AD/SCIM), validate that the address corresponds to an active person record and (optionally) that it is not marked as a group/distribution mailbox. This avoids relying on string heuristics alone.

- Treat forwarding as reduced assurance: if policy permits forwarded addresses, communicate that accountability is weaker and consider requiring step-up (TOTP/WebAuthn) for sensitive actions.

6. Quantifying Online-Guessing Risk

7. Multi-Key Rate Limiting and Composition

7.1. Limiter Model

7.2. Staged Composition Policy: Hard Gates, Soft Backstops, Greylisting

- Hard gates: enforce per-email and per-session buckets for OTP request and OTP submit.

- Soft backstops: treat IP buckets primarily as anomaly signals rather than immediate blocks (except for extreme abuse).

- Escalation: when IP anomalies occur (e.g., many distinct emails), require greylisting friction before OTP issuance; do not send OTP until greylist is satisfied.

7.3. Concrete Policy Template

| Endpoint | Primary keys | Example policy (token bucket) |

|---|---|---|

| Request OTP | email + session | 3/10min per email; 10/10min per session. |

| IP (soft) | Greylist if >20 distinct emails/10min per IP; hard block if >200 requests/10min. | |

| Submit OTP | email + session | 5 attempts/10min per email; 8/10min per session; 15min cooldown after cap. |

| Post-auth chat | session/user id | 60 msgs/hour; daily token budget; separate cap for tool calls. |

7.4. Composing Conflicting Signals

- 1.

- For OTP endpoints: require email AND session to pass; if IP is anomalous, return a greylist challenge (not a hard block) unless extreme.

- 2.

- For chat: enforce session/user limits and optionally apply IP limits only at extreme thresholds to avoid penalizing campus NAT.

7.5. Distributed Spraying Beyond Per-IP Throttling

- per-domain quotas (cap OTP sends per domain/time),

- global anomaly metrics (distinct emails per time, failure ratios),

- reputation signals (known bad ASNs, prior failure ratios),

- greylisting friction (CAPTCHA/proof-of-work) that cannot be bypassed by API calls (Section 9).

7.6. Tuning for Bursty Legitimate Usage Behind Shared IPs

- Keep hard gates on email/session: these scale with people rather than with network topology.

- Raise IP anomaly thresholds in campus networks: treat IP primarily as a soft signal and only hard-block at extreme levels; otherwise escalate to greylisting.

- Prefer greylisting to blanket IP blocks: when an IP looks anomalous (many distinct emails), require a human challenge before sending OTPs. This aligns with continuous-human-effort principles (HCO-style) where sustained scale incurs sustained effort [32].

- Use time-of-day and cohort signals: if the institution knows scheduled lab times or cohorts, temporarily widen buckets for known windows while maintaining per-email limits.

| Profile | Environment | Suggested adjustments |

|---|---|---|

| Campus lab NAT | Many users share one IP | Increase IP anomaly thresholds; keep per-email request caps; prefer greylist over IP hard-blocking. |

| Remote workforce | Low IP sharing | Treat IP as a stronger anomaly signal; lower greylist thresholds; shorten greylist windows. |

8. Deliverability, Anti-Enumeration, and Assurance Communication

8.1. Assurance Statement Template

Assurance level. This service uses email code verification to confirm control of an eligible mailbox. It is intended for controlled pilots and does not provide the same assurance as SSO (OIDC) or phishing-resistant MFA (WebAuthn). Do not share codes. If you suspect mailbox compromise, stop using the service and contact support.

8.2. Deliverability and Anti-Phishing Measures

8.3. Anti-Enumeration and Bounce Side Channels

- 1.

- Uniform envelope: return the same HTTP status and response shape for all outcomes of request-OTP and submit-OTP (success, ineligible, rate-limited, wrong code).

- 2.

- No early exits: run a constant “baseline” amount of server work on every path (e.g., compute a dummy HMAC and perform a constant-time comparison) before responding.

- 3.

- Timing equalization: enforce a minimum response time (e.g., a fixed response “envelope”) and add bounded jitter on failures to reduce oracle precision for automated probing.

- 4.

- Side-channel hygiene: do not expose SMTP/DMARC failures, allowlist membership, or rate-limit key selection in UI text; log these server-side only.

- 5.

- Measure leakage: instrument and periodically compare response-time distributions for eligible vs. ineligible paths; treat a consistent gap beyond network noise as a defect to remediate.

8.4. Data Minimization, Retention, and Institutional Compliance

- Do not log OTP codes. Avoid logging OTP nonces or verifiers unless strictly required for debugging, and never in plaintext.

- Short retention for OTP state: keep OTP issuance state for at most TTL+grace (minutes), then delete.

- Bounded retention for security events: keep authentication/rate-limit audit events for a limited period (e.g., 30–90 days) consistent with incident response needs and institutional policy.

- Minimize IP storage: where feasible, store truncated or hashed IPs for anomaly detection, and restrict access to raw IPs.

- Separate auth telemetry from chat content: store access-gate telemetry separately from conversation transcripts, with independent retention and access controls.

9. Low-Code Platform Hardening and Reference External State Pattern

9.1. Vendor-Agnostic Platform Validation Checklist

- 1.

- Server-side enforcement: can clients modify conversation variables or system messages?

- 2.

- Isolation: are variables isolated per user/session and protected from cross-tenant leakage?

- 3.

- Provenance: is message history treated as untrusted input (no privilege escalation via injected roles), consistent with LLM risk guidance [20]?

- 4.

- Connector scope: are secrets stored in a vault with least privilege and rotation [17]?

- 5.

- Webhook security: are webhook endpoints authenticated and replay-protected (timestamp + nonce)?

9.2. Replay-Resistant External State-Store with Monotonic Signed Transitions

9.3. Concrete Web Primitives for Session Fixation and CSRF Defenses

- Session cookies: Secure, HttpOnly, and SameSite=Lax (or Strict where feasible).

- Rotate session identifiers: issue a fresh session_id after successful OTP verification (mitigates fixation).

- CSRF: require POST for submit-OTP; validate Origin/Referer headers; and use either synchronizer tokens or double-submit cookies.

- CORS: do not allow cross-origin credentials except the intended origin.

9.4. Greylisting Mechanism That Cannot Be Bypassed

10. Standardized Pseudo-Code Snippets

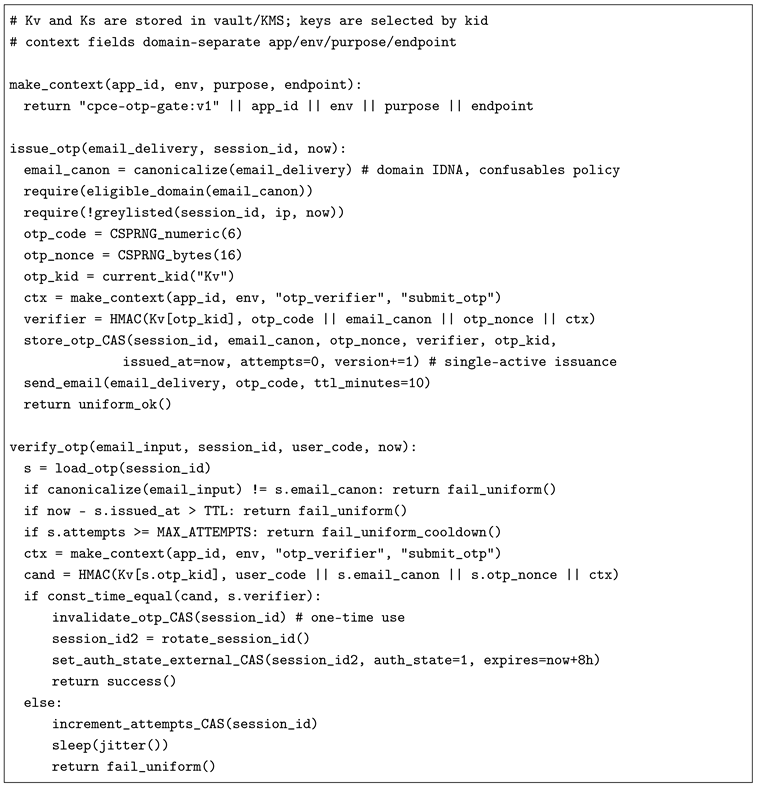

10.1. OTP Issuance and Verification

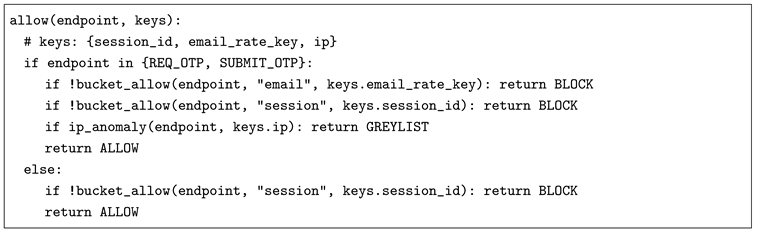

10.2. Token Bucket and Staged Multi-Key Composition

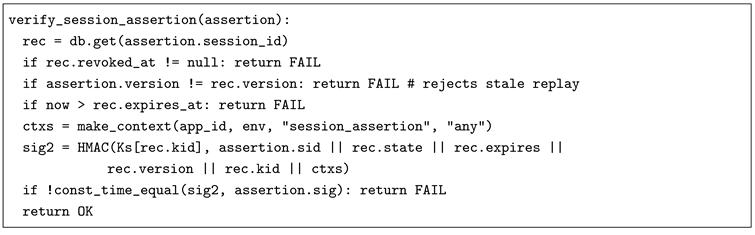

10.3. Signed Transition Verification (External State-Store)

11. Operational Evaluation Protocol

- authentication completion rate and P50/P95 time-to-auth,

- OTP deliverability latency distribution, bounce/spam-folder incidence, and support tickets,

- limiter trigger rate and false-positive analysis for shared IPs (campus NAT),

- model usage and cost before/after gating,

- sensitivity analyses for code length/TTL/attempt caps and anomaly thresholds,

- adversarial load tests (spraying across rotating IPs and emails) and greylist effectiveness.

12. Migration and End-to-End Security Posture

13. Limitations

14. Conclusion

References

- Markus Anderljung and Julian Hazell. Protecting society from AI misuse: when are restrictions on capabilities warranted? arXiv:2303.09377, 2023. arXiv:2303.09377.

- Ece Gumusel, Kyrie Zhixuan Zhou, and Madelyn Rose Sanfilippo. User privacy harms and risks in conversational AI: a proposed framework. arXiv:2402.09716, 2024. arXiv:2402.09716.

- Mutahar Ali, Arjun Arunasalam, and Habiba Farrukh. Understanding users’ security and privacy concerns and attitudes towards conversational AI platforms. arXiv:2504.06552, 2025. arXiv:2504.06552.

- NIST. Digital Identity Guidelines (SP 800-63 suite). Available online: https://pages.nist.gov/800-63-3/.

- Paul A. Grassi, James L. Fenton, et al. NIST Special Publication 800-63-3: Digital Identity Guidelines. National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2017 (updates posted online). https://pages.nist.gov/800-63-3/sp800-63-3.html.

- Paul A. Grassi, James L. Fenton, et al. NIST SP 800-63B: Authentication and Lifecycle Management. NIST Computer Security Resource Center. https://csrc.nist.gov/pubs/sp/800/63/b/upd2/final.

- D. M’Raihi, M. Bellare, F. Hoornaert, and D. Naccache. RFC 4226: HOTP: An HMAC-Based One-Time Password Algorithm. IETF, 2005. https://www.ietf.org/rfc/rfc4226.txt.

- D. M’Raihi, J. Rydell, M. Pei, S. Machani, and J. Erlandson. RFC 6238: TOTP: Time-Based One-Time Password Algorithm. IETF, 2011. https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc6238.

- D. Hardt. RFC 6749: The OAuth 2.0 Authorization Framework. IETF, 2012. https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc6749.

- M. Jones and D. Hardt. RFC 6750: The OAuth 2.0 Authorization Framework: Bearer Token Usage. IETF, 2012. https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc6750.

- E. Hammer-Lahav, D. Recordon, and D. Hardt. RFC 6819: OAuth 2.0 Threat Model and Security Considerations. IETF, 2013. https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc6819.

- N. Sakimura, J. Bradley, and N. Agarwal. RFC 7636: Proof Key for Code Exchange by OAuth Public Clients. IETF, 2015. https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc7636.

- T. Lodderstedt, M. Jones, and D. Hardt. RFC 9700: OAuth 2.0 Security Best Current Practice. IETF, 2025. https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/rfc9700/.

- OAuth Working Group. The OAuth 2.1 Authorization Framework (Internet-Draft). IETF Datatracker, accessed 2026-01. https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/draft-ietf-oauth-v2-1/ (accessed on 2026-01).

- OpenID Foundation. OpenID Connect Core 1.0 incorporating errata set 2. https://openid.net/specs/openid-connect-core-1_0.html.

- W3C. Web Authentication: An API for accessing Public Key Credentials. https://www.w3.org/TR/webauthn-3/.

- OWASP. OWASP Application Security Verification Standard (ASVS). https://owasp.org/www-project-application-security-verification-standard/.

- OWASP. OWASP Authentication Cheat Sheet. https://cheatsheetseries.owasp.org/cheatsheets/Authentication_Cheat_Sheet.html.

- OWASP. OWASP Multifactor Authentication Cheat Sheet. https://cheatsheetseries.owasp.org/cheatsheets/Multifactor_Authentication_Cheat_Sheet.html.

- OWASP. OWASP Top 10 for Large Language Model Applications. Available online: https://owasp.org/www-project-top-10-for-large-language-model-applications/.

- J. Klensin. RFC 5321: Simple Mail Transfer Protocol. IETF, 2008. https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc5321.

- P. Resnick. RFC 5322: Internet Message Format. IETF, 2008. https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc5322.

- J. Klensin. RFC 5890: Internationalized Domain Names for Applications (IDNA): Definitions and Document Framework. IETF, 2010. https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc5890.

- Unicode Consortium. UTS #39: Unicode Security Mechanisms. Available online: https://www.unicode.org/reports/tr39/.

- Henrik Schiøler, John Leth, and Shibarchi Majumder. Markovian performance model for token bucket filter with fixed and varying packet sizes. arXiv:2009.11085, 2020. https://arxiv.org/abs/2009.11085.

- Dmitry Kogan, Nathan Manohar, and Dan Boneh. T/Key: second-factor authentication from secure hash chains. arXiv:1708.08424, 2017. arXiv:1708.08424.

- Boudhayan Gupta. A replay-attack resistant message authentication scheme using time-based keying hash functions and unique message identifiers. arXiv:1602.02148, 2016. arXiv:1602.02148.

- Shashank Shreedhar Bhatt, Tanmay Rajore, Khushboo Aggarwal, et al. Enterprise AI must enforce participant-aware access control. arXiv:2509.14608, 2025. arXiv:2509.14608.

- Manideep Reddy Chinthareddy. Enterprise Identity Integration for AI-Assisted Developer Services: Architecture, Implementation, and Case Study. arXiv:2601.02698, 2026. arXiv:2601.02698.

- Rama Akkiraju et al. FACTS About Building Retrieval Augmented Generation-based Chatbots. arXiv:2407.07858, 2024. arXiv:2407.07858.

- Xinyi Hou, Jiahao Han, Yanjie Zhao, and Haoyu Wang. Unveiling the Landscape of LLM Deployment in the Wild: An Empirical Study. arXiv:2505.02502, 2025. arXiv:2505.02502.

- Homayoun Maleki, Nekane Sainz, and Jon Legarda. Human Challenge Oracle: Designing AI-Resistant, Identity-Bound, Time-Limited Tasks for Sybil-Resistant Consensus. arXiv:2601.03923, 2026. arXiv:2601.03923.

- H. Krawczyk and P. Eronen. RFC 5869: HMAC-based Extract-and-Expand Key Derivation Function (HKDF). IETF, 2010. https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc5869.

- M. Jones, J. Bradley, and N. Sakimura. RFC 7519: JSON Web Token (JWT). IETF, 2015. https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc7519.

- A. Biryukov, D. Dinu, and D. Khovratovich. RFC 9106: The Argon2 Memory-Hard Function for Password Hashing and Proof-of-Work Applications. IETF, 2021. https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc9106.

- OWASP. OWASP Password Storage Cheat Sheet. Available online: https://cheatsheetseries.owasp.org/cheatsheets/Password_Storage_Cheat_Sheet.html.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).