1. The Distribution and Pollution of Se in Water

Se is a trace element widely present in the environment. The average concentration of Se in freshwater worldwide is 0.02 μg/L, and in seawater is below 0.08 μg/L [

1,

2]. Due to direct contact with rocks, groundwater generally contains higher levels of Se than surface waters [

3]. The Se levels in the surface water are time and climate dependent, the variation trend of Se concentration in surface water with time is flood season > mean flow season > dry season [

4,

5]. Dinh et al. [

6] found that the total concentrations of Se in drinking water in China ranged from 0.017 μg/L to 46.0 μg/L; according to the different selenium content, drinking water can be classified into the following grades: selenium deficiency (0.08 μg/L) < selenium marginal (0.29 μg/L) < selenium sufficient (0.49 μg/L) < selenium rich (1.84 μg/L) < selenium excessive (26.93 μg/L).

Mines are the main source of Se released into the environment. Se production is expected to be around 2500-2800 tons per year [

7]. Most Se exists in the form of associated elements in other elemental deposits. At present, the known independent Se deposits include El Dragon Se deposit, Pacajake Se deposit in Bolivia, and Yutangba Se deposit in Enshi, Hubei Province, China [

8,

9]. Mining effluent represents the initial route of Se introduction into surface water and soil-plant system through acid mine water drainage [

10]. In China, the average content of Se in the Se mine can reach 3,637.50 mg/kg, the maximum concentration can even reach 84,000 mg /kg in some mining areas; the Se content detected in the surface water of Enshi ranged from 0.27 to 342.86 μg /L, and the Se content in drinking water was ranged from 0.37 to 40.9 μg /L, which was higher than the global freshwater Se content of 0.2 μg /L [

11]. The Se content in wastewater reported by other mines generally ranges from 3 μg/L to more than 12 mg/L [

3], with uranium mine wastewater at 1.6 mg/L and gold mine wastewater at 0.2 to 33 mg/L [

12]. The Se coal mine groundwater is 3 to 330 μg/L [

3]. The Se in the oil refinery wastewater is 15 to 75 μg/L [

13,

14].

2. The Impact of Se on Health and Its Limit Requirements in Drinking Water

Se is one of the essential trace elements of human, can cause various diseases and dysfunction of human tissues due to Se deficiency and excessive intake [

15]. The toxicity, fluidity, bioavailability and reactivity of Se depend on its chemical form and the different oxidation states of Se in aqueous solutions. Se has four common oxidation states (-Ⅱ, 0, IV, VI). Elemental Se [Se(0) ] is non-toxic because it is not easily dissolved and absorbed. Se compounds include inorganic Se compounds and organic Se compounds, and the toxicity of inorganic Se is about 40 times higher toxicity than that of organic Se. Inorganic Se includes selenite [SeO3

2-, Se(IV)], selenate [SeO4

2-, Se(VI)], selenide [Se

2-, Se(-Ⅱ)]. Se(IV) and Se(VI) are water-soluble, while the metal selenides in Se and Se(-Ⅱ) are insoluble in water. Organic Se has low toxicity, high bioactivity and high bioavailability. Selenomethionine, selenocysteine and other selenium-amino acid derivatives are available organic Se sources for humans and animals. Kieliszek and Bano [

16] summarized mammalian Selenoproteins and their functions in the body. Haug et al. [

17] reported that selenomethionine was the major selenocompound in cereal grains, grassland legumes and soybeans, while methylselenocysteine was the major selenocompound in Se-enriched plants such as garlic, onions, sprouts, broccoli and wild leeks.

Se deficiency can lead to Keshan, Kashin-Beck, and Alzheimer’s disease [

18,

19,

20]. Se supplementation can improve the body’s immunity and fertility, as well as anti-oxidant, anti-cancer, and anti-heavy metal [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. Excessive intake of Se can cause poisoning and injury, chronic Se intoxication is mainly related to continuous exposure and long-term intake of Se-contaminated drinking water and high Se crops [

27]. Wang et al. provided a comprehensive summary of the relationship between selenium, the gut microbiota and some diseases [

28]. China, South Korea, USA, Canada, Australia and New Zealand have established recommended daily intake levels for adults with a maximum safe dose of 400 µg.

Therefore, all countries have stipulated the maximum allowable content of selenium in water. The limit of selenium in drinking water in most countries or regions is 10-50 µg/L in

Table 1, with 10 μg/L being the most common [

29]. All countries around the world have recommended intake standards for selenium. In China, the Nutrition Society released the recommended intake of dietary selenium for different populations in the 2023 edition of the Reference Intake of Dietary Nutrients for Chinese Residents [

30].

Table 1.

Maximum contaminant level of Se in drinking water as stipulated by various agencies in worldwide [

29].

Table 1.

Maximum contaminant level of Se in drinking water as stipulated by various agencies in worldwide [

29].

| Countries and organizations |

Maximum acceptable concentration (MAC) |

UNICEF, Quebec, Saskatchewan, New Brunswick, Ontario, British Columbia, Oklahoma, Oceania Australia, Papua New Guinea, Fiji, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, United Kingdom, Germany, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Belarus, Turkey, France, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Ecuador, Panama, Peru, Bolivia, Argentina, Cambodia, China, Taiwan, Israel, Japan, India, Bangladesh, Malaysia, Thailand, Yemen, Mozambique, Morocco, Rwanda, Egypt,

Ethiopia, East African Community, Uganda, Tanzania |

10 µg/L |

| Jordan |

15 µg/L |

| European Union, Switzerland, |

20 µg/L |

| California Environmental Protection Agency |

30 µg/L |

| WHO, New Zealand, Brazil, Mexico, Abu Dhabi, Singapore, Saudi Arabia, |

40 µg/L |

| Health Canada, US EPA, California, Ukraine, Dominican Republic, South Africa, |

50 µg/L |

Table 2.

Dietary selenium reference intakes of Chinese residents [

30].

Table 2.

Dietary selenium reference intakes of Chinese residents [

30].

| Age |

Average demand (μg/d) |

Recommended intake (μg/d) |

The maximum tolerable intake (μg/d) |

| 0~ |

– |

15 |

55 |

| 0.5~ |

– |

20 |

80 |

| 1~ |

20 |

25 |

80 |

| 4~ |

25 |

30 |

120 |

| 7~ |

30 |

40 |

150 |

| 9~ |

40 |

45 |

200 |

| 12~ |

50 |

60 |

300 |

| 15~ |

50 |

60 |

350 |

| 18~ |

50 |

60 |

400 |

| Pregnancy |

54 |

65 |

400 |

| Lactation period |

65 |

78 |

400 |

3. Selenium Detection Technology in Water

Se exists in biological systems in a variety of chemical forms, and its bioavailability and toxicity depend on its chemical form and concentration. The determination method of Se needs to consider the accuracy, concentration range of analyte, standardized volume of sample, physical and chemical properties of detection substrate and possible interfering substances. At present, the detection method of Se in water quality is generally based on the specific reaction between Se (IV) and reagents. The determination of total Se is to convert various forms of Se into the same valence state to determine its total content. The methods for detecting selenium in water include hydride - atomic spectrometry, fluorescence spectrometry, ultraviolet spectrophotometry, chromatography, voltammetry, etc. Here, China is taken as an example, the standard detection methods for selenium in water were showed in

Table 3.

In

Table 3, atomic spectrometry and mass spectrometry require large-scale and expensive instruments, these methods need to be operated by professionals, have complex pretreatment (extraction, enrichment or separation steps) and high detection costs. However, their sensitivity (0.2-50 μg/L) does not have a significant advantage over spectrofluorometry or UV-Vis spectrophotometry (0.25-10 μg/L). Therefore, in general, just choose the spectrofluorometry or UV-Vis spectrophotometry method. At present, the instruments used in spectrofluorometry or UV-Vis spectrophotometry methods are quite widespread and affordable, making them more suitable for daily testing work. Especially in on-site rapid testing, since there are portable handheld colorimeters available for spectrofluorometry or UV-Vis spectrophotometry methods, the testing process is more convenient and faster. When the timeliness requirement for water quality detection is not strong and when detecting extremely trace amounts of selenium in water, atomic spectrometry and mass spectrometry may demonstrate some advantages by optimizing pretreatment methods. By comparing with

Table 1 and

Table 3, it can be seen that spectrofluorometry and atomic spectrometry can meet the detection requirements of drinking water in almost all countries. The detection sensitivity of other methods is relatively low, and it is necessary to conduct further in-depth research on sample enrichment and anti-interference in pretreatment.

3.1. Atomic Spectrometry

Atomic spectrometry includes atomic absorption spectrometry (AAS) and atomic fluorescence spectrometry (AFS). The method is always combined by hydride generation (HG) production technology, by which Se was separated as a gas from water. AAS method has higher sensitivity compared with AFS in China standard method GB/T 5750.6-2023 (

Table 3). Abdolmohammad-Zadeh et al. [

35] used a nano-structured nickel-aluminum layered double hydroxide as adsorbents for solid phase extraction of Se before continuous-flow HG-AAS, with a detection limit of 10 ng/L. Ali et al. [

36] used ammonium pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate to form a hydrophobic complex with Se, which was extracted by a dispersing medium of Triton X-114 and 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate ionic liquid. The Se hydrophobic complex was detected by graphite furnace atomic absorption spectrometry with a detection limit of 0.07 µg/L. Muslim et al. [

37] prepared an extraction solvent with undecanoic acid and tetrabutylammonium hydroxide. It was used for air-assisted solidified floating organic drop coupled to a hydride generation atomic absorption spectrometer to detect selenium. The detection limit was 0.07 µg/L. This method was more environmentally friendly and practical. Muhammet and Dilek [

38] developed a new ultra-sensitive method for Se determination by combining a Pd-coated W-coil atom trap and hydride generation atomic absorption spectrometry (HG-AAS), its sensitivity was 38 times more than the conventional HG-AAS method. Marco et al. [

39] detected selenium in tap water samples by high performance liquid chromatography-continuous flow hydride generation (containing an online pre-reduction process)-flame atomic absorption spectrometry, the limit of detection of Se(IV) and Se(VI) were 0.09/0.31 mg/kg, the limit of quantitation of Se(IV) and Se(VI) were 0.23/0.77 mg/kg. HG-AFS is the first method to detect Se in water quality in the national standard (GB/T 5750.6-2023) [

31]. Due to the low concentration of Se(IV) and the complexity of the environmental sample, direct analysis of Se(IV) using HG-AFS is often disturbed, therefore, separation or enrichment step are required before instrumental determination. Lu et al. [

40] determined Se (IV) in natural water by online polytetrafluoroethylene fiber filled microcolumn preconcentration combined with HG-AFS, with a detection limit of 4 ng/L. Wang et al. [

41] based on solidified floating drops of 1-undecanol that were capable of extracting the target analyte after chelation with a water soluble ligand and subsequent ultrasound-assisted back-extraction into an aqueous solution, and then determined Se (IV) by HG-AFS, with a detection limit of 7.0 ng/L. It was seen that, no matter AAS method or AFS method, researchers mainly focused on pre-treatment optimization, focusing on selenium enrichment or extraction, in order to improve the detection sensitivity.

3.2. Spectrofluorometry

The 2,3-diaminonaphthalene fluorescence photometric method is common in spectrofluorometry, it is often a national standard method, such as China standard method GB/T 5750.6-2023 [

31], 2,3-diaminonaphthalene reacts with Se(IV) in acidic solution to produce green fluorescent substances, which is extracted by cyclohexane to quantitatively determine the content of Se. The diamino naphthalene fluorescence method is a classical method for the determination of Se. It has high sensitivity, but the operation is cumbersome and time-consuming. Serra et al. [

42] improved the determination method of selenium (IV) by taking advantage of the principle that selenite reacts with 2,3-diaminaphthalene (DAN), combined with solid-phase extraction and automatic flow injection analysis techniques. The detection limit sensitivity was increased to 1.7 μg/L. Feng et al. [

43] used a ligand 2-(2-(2-aminoethylamino)ethyl)-3’,6’-bis(ethylamino)-2’,7’-dimethylspiro[isoindoline-1,9’-xanthen]-3-one that was synthesized from rhodamine 6G as a fluorescent probe to detect Se(IV), with significant sensitivity and selectivity, and its detection limit was 0.22 μg/L. Thakur et al. [

44] synthesized Sn-doped carbon quantum dots fluorescent probe by microwave irradiation, and used Se-Sn cross-linked complex to induce fluorescence quenching to detect Se (IV). The probe was also selective in the presence of common interfering ions, and the detection limit was 0.011 μg/L. Aimaitiniyazi et al. [

45] proposed a visual detection method with DAN as fluorescent ligand and 9-anthrene ethanol as the fluorescent reagent, which improved the sensitivity of the method with a detection limit of 1.6 µg/L. It successfully applied the visualization based on fluorescence to the detection of Se using a portable smartphone platform. The emergence of the fluorescent probe to improve the sensitivity of spectrofluorometry, it will be the direction of future development and research.

3.3. Ultraviolet-Visible Spectrophotometry

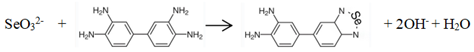

The ultraviolet-visible spectrophotometry is simple and easy to operate, but it lacks sufficient sensitivity and selectivity when detecting low levels of Se in the environment. Therefore, it usually combines with extraction and concentration for determination. The reaction of 3,3’-diaminobenzidine (DAB) and Se (IV) is a traditional method, which chemical reaction is as follows:

Selenite 3,3’-Diaminobenzidine 3,4-diaminophenyl piazaselenol

After the water sample was digested with mixed acid, the selenium element inside was converted into Se (IV), it reacted with DAB to form a yellow product, which was extracted with toluene and measured at 420 nm by chromometer [

32]. The functional group of 3,3’-diaminobenzidine reacting with Se is the o-diamine, and its semi-molecule o-phenylenediamine has the functional group that can react with Se. Chen et al. [

46] analyzed selenium in water of hot spring by ultraviolet-visible spectrophotometry with o-phenylenediamine as color reagent. Its detection wavelength was 333 nm, the linear relationship was from 0.05 to 0.40 μg/mL. Cloud point extraction (CPE) is a liquid-liquid extraction technique. Sounderajan et al. [

47] reported the method to determine the content of Se (IV) and Se (VI) in water by CPE, that is based on Se-DAB complex with Triton X-114. Its detection limit was 0.0025 μg/L. Agrawal et al. [

48] determined Se (IV) by the reaction mechanism of ion-association complex, and the detection limit was 10 ng/mL. Nayanova et al. [

49] determined Se (IV) by the oxidation of methylene blue and of Se(VI) by its interaction with the specified reagent with the formation of an ion pair. The limits of detection are 1 μg/L and 0.8 μg/L, respectively. Xiong et al. [

50] selected thiol cotton as the functional material for simple solid-phase extraction separation of Se(IV). Then, based on the intensity changes of blue color produced by iodine and starch under the catalysis of Se, multimodal detection methods using spectrophotometric detection, smartphone app-based colorimetric detection, and naked-eye colorimetric detection were developed for Se detection. The spectrophotometric detection mode exhibited a linear response from 0.01 to 8.0 µg/mL with a detection limit of 0.0047 µg/mL; the smartphone app-based colorimetric detection mode was linear from 1.0 to 6.0 µg/mL with a detection limit of 0.05 µg/mL; and Se levels of 0.1 µg/mL could be clearly distinguished by the naked eye. Wang et al. [

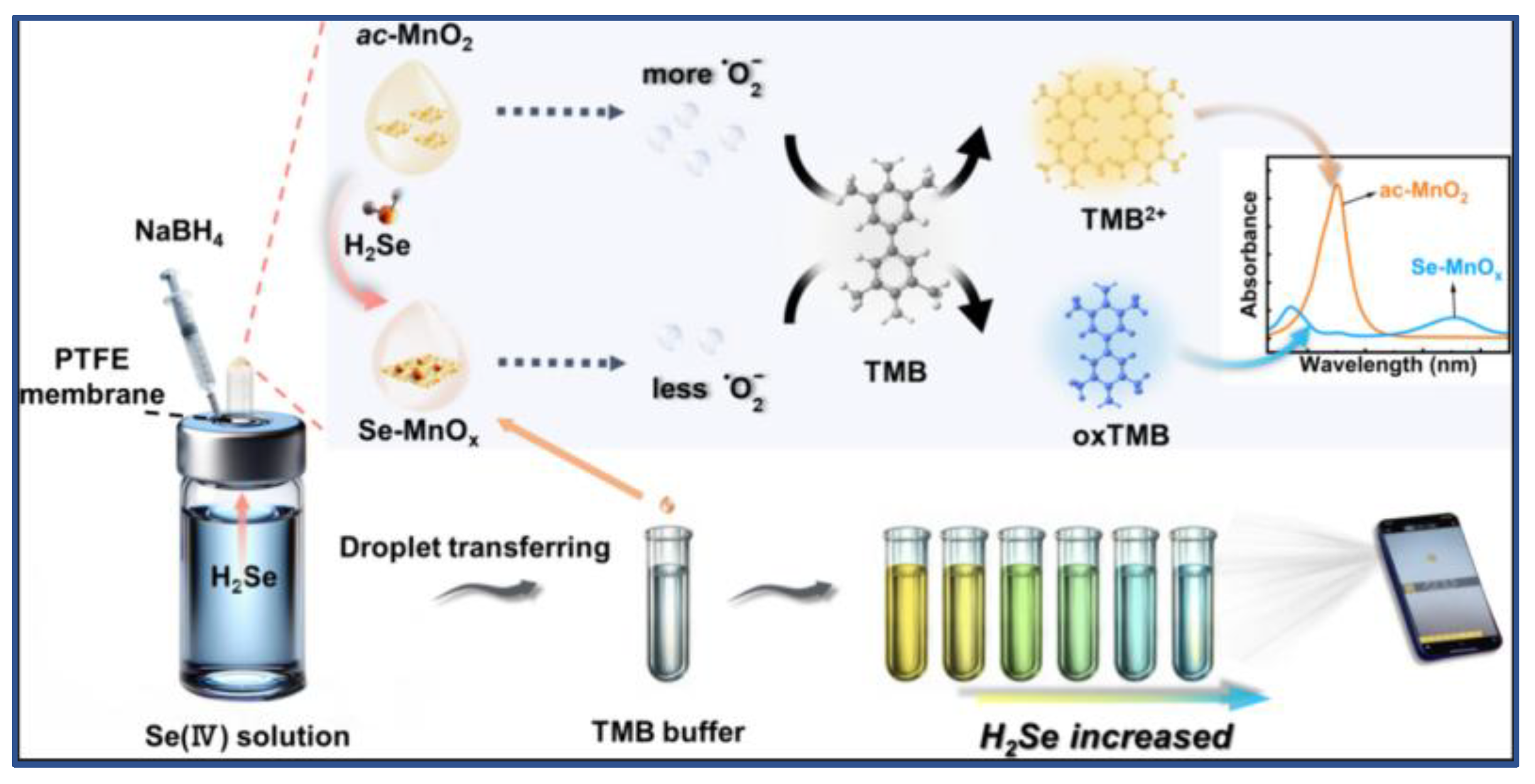

51] reduced Se(IV) in samples into volatile selenium hydride (H

2Se) by chemical reaction, H

2Se oxidized with ac-MnO

2 and the Se-MnOx was produced (

Figure 1). It oxidated 3,3’,5,5’-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) to a blue substance, the degree of color change is linearly related to Se concentration. This method could realize sensitive multicolor visual detection, the Se(IV) detection range was 10 to 600 μg/L and the limit of detection was 1.8 μg/L. How to make visible spectrophotometry more convenient, rapid, highly sensitive and easily directly judged by the human eye will be an important research direction for Ultraviolet-Visible spectrophotometry.

3.4. Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry

Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) always combines chromatography, which includes gas chromatography (GC) and high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). GC can be used to quantify volatile organic Se compounds. And the analysis of inorganic Se requires the conversion of compounds into volatile compounds, such as hydrogenated Se and alkyl Se compounds. Species-specific isotope dilution are excellent methods for accurately quantifying element speciation. Breuninger et al. [

52] established a method for the determination of the various Se chemical fractions, used species-specific isotope dilution gas chromatography coupled to inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Sensitivity was improved by increasing pre-concentration factors through larger sample volumes, using larger injection volumes or individual injections of derivatives of Se(IV) and Se(VI). The detection limit of this method reached 0.9-3.1 ng/L. HPLC is commonly used to detect non-volatile Se, including Se(VI) and Se(IV). The Se compounds in water were separated by HPLC and detected by ICP-MS. For example, Martínez-Bravo et al. [

53] used anion-exchange liquid chromatography coupled with ICP-MS to detect Se compounds. The detection limits of Se(IV) and Se(VI) were 1.2 μg/L and 1.4 μg/L, respectively. And this method realized synchronous detection of arsenic, Se and chromium(VI). Luo et al. [

54] mixed Se (IV) and Se(VI) separated from HPLC with MIL-125-NH

2 nanoparticles and formic acid in the photochemical vapor generation reactor to form gaseous Se-containing species under ultraviolet irradiation, which was introduced into ICP-MS to determine Se. The limits of detection of Se(IV) and Se(VI) were both as low as 0.8 ng/mL, and the relative standard deviations of 4.6% and 3.7%, respectively. Song et al. [

55] analyzed the nano-Se (nSe) captured by polyvinylidene fluoride and nylon microporous filtration membranes by ICP-MS, its retention rate was more than 91.0 ± 0.87%. At the same time, HPLC and ICP-MS were used to analyze the selenite and selenate ions escaping from the membranes, and the separation and determination of nSe and ionic Se were realized. The recoveries of nSe ranged from 70.2% to 85.8% at a spike level of 0.2 µg/L, and the recoveries of 0.2 µg/L nSe and 0.55 µg/L Se(IV) and Se(VI) were 70.2% - 85.8% and 83.6% - 101%, respectively. Compared with other analysis methods, the most advantage of ICP-MS is that it can analyze the content of Se in different forms. In contrast, other methods usually convert different forms of selenium into a single form of inorganic selenium for determination through pre-treating (especially digesting), mainly to measure the total selenium content. For instance, the ICP-MS method in China standard GB/T 5750.6-2023 directly states that this method can simultaneously determine selenocysteine with detection limit of 1.0μg/L, methylselenocysteine with detection limit of 1.4μg/L, selenite with detection limit of 1.0μg/L, selenomethionine with detection limit of 2.0μg/L, and selenate with detection limit of 1.0μg/L [

31]. This method is more appropriate when understanding the content of selenium in different forms in water bodies.

3.5. Voltammetry

Voltammetry pre-concentrates the ions to be measured onto the electrode surface by electrodeposition, and then strips the enriched ions by reverse scanning voltage [

56]. Voltammetry typically uses stripping analysis with a pre-enrichment step, it can achieve lower detection limit. Voltammetry includes adsorptive cathodic stripping voltammetry and anodic stripping voltammetry. The working electrodes used for the determination of Se include glassy carbon electrode, hanging mercury electrode, mercury plating electrode and so on. Recently, different kinds of functional materials have been employed to modify electrode surface to improve detection performance, including carbon-based nanomaterials, noble metals and conductive polymers [

57,

58,

59,

60].

Ashournia and Aliakbar [

61] found that Se(IV) and I

− can react quickly and completely to produce Se-I

2 under acid catalysis. They used bovine albumin as the medium for adsorption accumulation of Se-I

2 on a thin mercury film electrode, and the adsorbed Se-I

2 was stripped in HCl solution by differential pulse cathodic potential scanning. Due to the influence of bovine albumin on the adsorption accumulation of Se-I

2, the sensitivity of this method was improved. Ashournia and Aliakbar [

62] developed a thin mercury electrode based on the principle that o-phenylenediamine reacts with Se (IV) in acidic solution to produce 5-nitropiazselenol, which has a high tendency of self-accumulation on it. The adsorbed 5-nitropiazselenol was stripped in HCl solution by cathodic potential scanning for the determination of Se in natural water. Ramadan et al. [

63] studied the differential pulse anodic stripping voltammetry (DPASVA) determination of Se (IV) with a vitamin E-nafion modified gold electrode. The sensitivity was 200 times more than the bare gold electrode. Ramadan and Mandil [

64] studied the DPASVA at a methylene blue-nafion modified gold electrode. The sensitivity was 5 times more than the vitamin E-nafion modified gold electrode, and 1000 times more than the bare gold electrode. Ramadan et al. [

65] studied the DPASVA at a gold electrode modified with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine, its sensitivity was more than 20000 times than the bare gold electrode. Ramadan et al. [

66] studied the DPASVA at a gold electrode modified with o-phenylenediamine-nafion. The sensitivity was 2000 times more than the bare gold electrode. Tan et al. [

67] designed a gold nanocages/fluorinated graphene nanocomposite modified glassy carbon electrode (GCE) for the electrochemical determination of selenium by square wave anodic stripping voltammetry, its detection limit was 0.27 μg/L. Yue et al. [

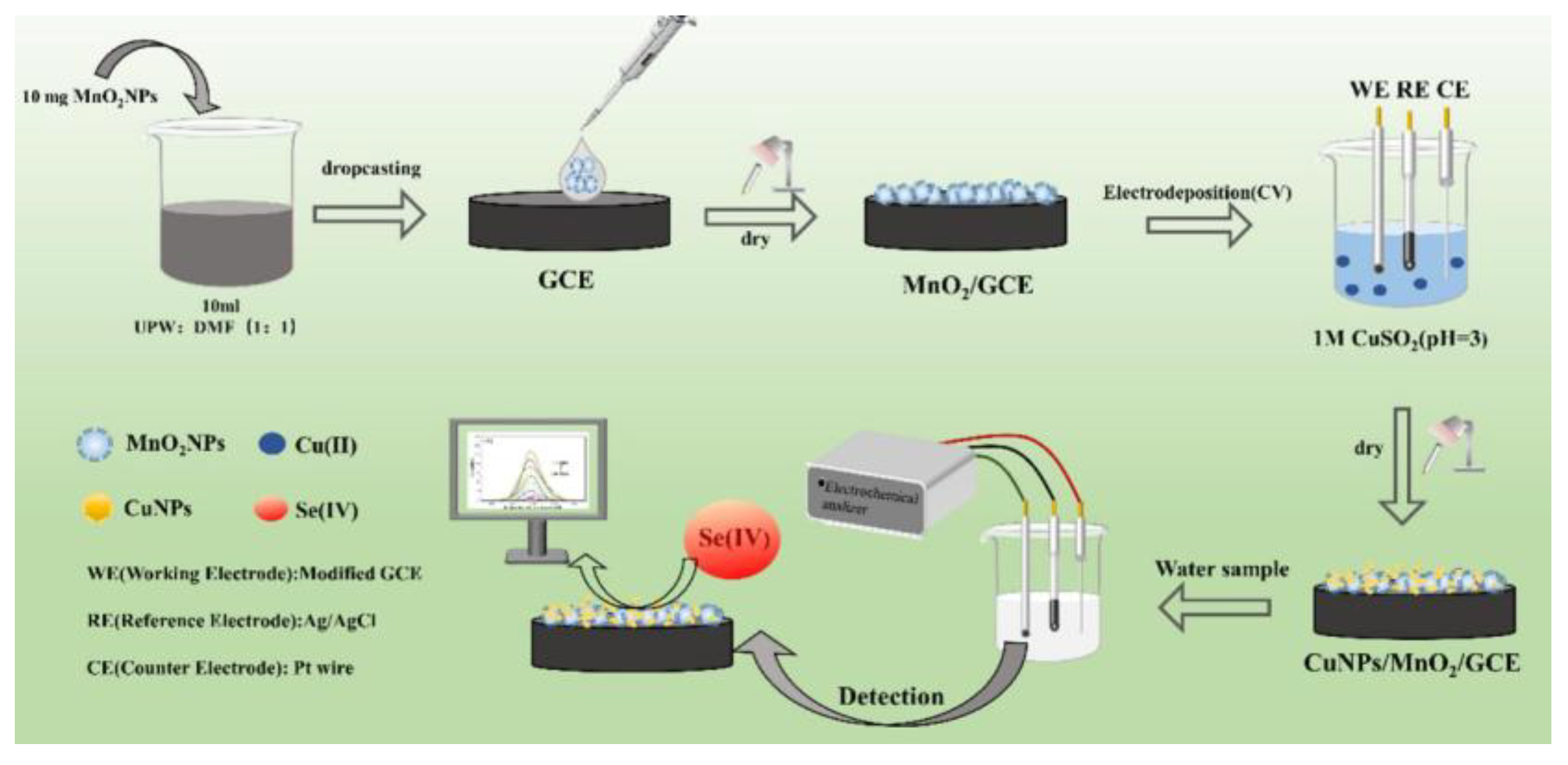

68] carried out a nanocomposite-based electrochemical sensor that enhanced the Se(IV) adsorption and accelerated electron transfer by sequentially immobilizing manganese dioxide and electrodeposited copper nanoparticles onto a glassy carbon electrode (

Figure 2), it had synergistic effects to enhance electrochemical performance, its detection limit was 3.7 μg/L (linear response range of 0.01 to 1 mg/L). Voltammetry has the advantages of high sensitivity, short response time, small instrument size and simple operation. It has attracted much attention in the in-situ rapid detection of selenium ions. However, it is still necessary to design and synthesize suitable working electrode modification materials to make them have better stability, anti-interference ability, high detection sensitivity and lower detection limit, so as to achieve in-situ rapid detection of water samples in the field.

3.6. Other Methods

Of course, in addition to the common detection methods, there are other methods used to determine Se. The determination of Se is typically carried out after pre-concentration with adsorbent, but it is difficult to achieve separation and preconcentration in the solutions containing high concentrations of SO4

2-. Nakakubo et al. [

69] used dithiocarbamate-modified cellulose (DMC) for selective extraction and preconcentration of Se, and used portable liquid electrode plasma-optical emission spectrometry for quantitative analysis. DMC was found to have significant selectivity for Se(IV), and quantitative extraction of Se(IV) is achieved even in a high concentration SO4

2- solution. Qiu et al. [

70] developed a novel localized surface plasmon resonance sensor to detect Se(IV) based on the extraordinary lateral etching of gold nanorods. The detection limit was 25.4 nmol/L. Yang et al. [

71] prepared hapten modification and bioconjugates for selenium, established an indirect competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, the linear range was 17 – 207 pmol/ mL and the detection limit was 3.9 pmol/mL. Recovery tests from 4 different Se compounds in water samples showed good recoveries ranging from 80% to 108% were achieved, with CVs ranging from 2.1% to 11%. With the development of analytical chemistry and instrument science, more and more selenium detection techniques will be developed.

4. Conclusions

With the extensive development of industrial activities and economic development, Se pollution is inevitable, the analysis technology of Se becomes particularly important. The ICP-MS method and electrochemical methods can analyze different forms of inorganic and organic selenium, other methods can only determine a single form of selenium. But electrochemical methods are currently mainly focused on the detection of Se(IV). Therefore, the ICP method has a good advantage in the multi-form analysis of selenium in environmental samples. The instruments required for spectrofluorometry and ultraviolet-visible spectrophotometry are relatively economical and practical, have a high popularity rate, and are easy to operate. The instruments used in atomic spectrometry and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry are expensive, bulky, complex to operate and require more professional technicians. Spectrofluorometry has higher sensitivity and selectivity compared with ultraviolet-visible spectrophotometry, and its sensitivity can catch up with atomic spectrometry. By synthesizing fluorescent probes and adding fluorescent reagents, its anti-interference ability can be improved. This method will be one of the important directions for the future development of selenium determination technology. Voltammetry has great potential in in-situ rapid detection. Its sensitivity and selectivity largely depend on the analytical characteristics of the sensor material or electrode. This method also has great potential in in-situ rapid detection.

Selenium compounds in the natural environment vary significantly at different times and spaces. Therefore, it is necessary to select the detection method based on the actual situation, such as the sensitivity requirements for detection, whether multi-form selenium analysis is needed, and the requirements for detection timeliness, etc. Various detection methods complement each other, establishing a safety monitoring mechanism with large-scale instrument analysis as the main body and on-site rapid screening detection methods as a supplement, providing effective technical support for the detection of selenium in water quality and pollution monitoring under actual environmental conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.W. and W.B; methodology, D.W.,W.B and F.X.; validation, D.W. and F.X.; formal analysis, D.W.; investigation, D.W. and F.X.; resources, D.W. and W.B; data curation, D.W. and F.X.; writing—original draft preparation, D.W. and F.X.; writing—review and editing, D.W.and X.Y; supervision, D.W. and X.Y; project administration, W.B.; funding acquisition, W.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Provincial Natural Science Fund (LGN21C200017), SchoolEnterprise cooperation project (2023-KYY-513110-0001 and 2023-KYY-513110-0016).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Experimental Teaching Center of Zhejiang University for providing the scientific research platform.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| AAS |

Atomic absorption spectrometry |

| AFS |

Atomic fluorescence spectrometry |

| CPE |

Cloud point extraction |

| DAB |

3,3’-diaminobenzidine |

| DAN |

2,3-diaminonaphthalene |

| DMC |

Dithiocarbamate-modified cellulose |

| DPASVA |

Differential pulse anodic stripping voltammetry |

| GC |

Gas chromatography |

| GCE |

Glassy carbon electrode |

| H2Se |

Selenium hydride |

| HG |

Hydride generation |

| HG-AAS |

Hydride generation atomic absorption spectrometry |

| HG-AFS |

Hydride generation atomic fluorescence spectrometry |

| HPLC |

High performance liquid chromatography |

| ICP |

Inductively coupled plasma |

| ICP-MS |

Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry |

| nSe |

Nano-Se |

| TMB |

3,3’,5,5’-tetramethylbenzidine |

| Se |

Selenium |

| WHO |

World Health Organisation |

| UNICEF |

United Nations Children’s Fund |

| US EPA |

United States Environmental Protection Agency |

References

- Fernádez-Martínez, A.; Charlet, L. Selenium environmental cycling and bioavailability: a structural chemist point of view. Reviews in Environmental Science and Bio/Technology 2009, 8, 81–110. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, K.; Mason, P.R.D.; Cappellen, P.V.; Johnson, T.M.; Gill, B.C.; Owens, J.D.; Diaz, J.; Ingall, E.D.; Reichart, G.J.; Lyons, T.W. Selenium as paleo-oceanographic proxy: a first assessment. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 2012, 89, 302–317. [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.; Ungureanu, G.; Boaventura, R.; Botelho, C. Selenium contaminated waters: An overview of analytical methods, treatment options and recent advances in sorption methods. Science of The Total Environment 2015, 521–522, 246–260. [CrossRef]

- Wellen, C.C.; Shatilla, N.J.; Carey, S.K. Regional scale selenium loading associatedwith surface coal mining, Elk Valley, British Columbia, Canada. Science of the total environment 2015, 532, 791-802. [CrossRef]

- Chen, M. Study on the Transfer Rule of Hg, As, Se for Weihe River in Xi’an. Master Thesis, Chang ‘an University, Xi’an, Shaanxi Province, China, 2016. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=35M_ufc67zsvZSMKiyXr5JlNnuUAg9nDgPo7uNUbU_oi33nKO3IfuobfAHfvM0XGVlXjM-Wb0PPSypY50O1_s2IDfk8t_fk6Ym00cQiD2Df3KbFifQacorBVv8A7noTqilBbFVkehbyTr4FsJ8nEcW3slegOjD6Z9QWCNzIbJMnfEcR-ybuK-A==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS.

- Dinh, Q.T.; Cui, Z.; Huang, J.; Tran, T.A.T.; Wang, D.; Yang, W.; Zhou, F.; Wang, M.; Yu, D. (). Selenium distribution in the Chinese environment and its relationship with human health: A review. Environment International 2018, 112, 294–309. [CrossRef]

- Ullah, H.; Liu, G.; Yousaf, B.; Ali, M.U.; Irshad, S.; Abbas, Q.; Ahmad, R. A comprehensive review on environmental transformation of selenium: recent advances and research perspectives. Environ Geochem Health 2019, 41, 1003-1035. [CrossRef]

- Redwood, S.D.Famous mineral localities: the Pacajake selenium mine, Potosi, Bolivia. Mineralogical Record 2003, 34, 339–357. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/famous-mineral-localities-pacajake-selenium-mine/docview/211710504/se-2.

- Wang, G.; Liu, J.; Liu, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhang, B.; Wang, Z.; Wang, L. Types, distribution and resource potential of selenium deposits in China. China Mining Magazine 2024, 33, 39–50. [CrossRef]

- Etteieb, S.; Magdouli, S.; Zolfaghari, M.; Brar, S.K. Monitoring and analysis of selenium as an emerging contaminant in mining industry: A critical review. Science of the Total Environment 2020, 698, 134339. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wwan, H.; Zhu, Y.; Ming, J.; Xiang, J.; Yin, H.; Yang, Y. Progress on utilization and characteristic of natural selenium resources in enshi autonomous prefecture. Current Biotechnology 2017, 5, 545–550. https://link.cnki.net/doi/10.19586/j.2095-2341.2017.0099.

- Twidwell, L.; McCloskey, J.; Joyce, H.; Dahlgren, E.; Hadden, A. Removal of selenium oxyanions from mine waters utilizing elemental iron and galvanically coupled metals, Innovations in Natural Resource Processing-Proceedings of the Jan. D. Miller Symposium. Englewood, CO, USA: SME. 2005.https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235348992.

- Lemly, A.D. Aquatic selenium pollution is a global environmental safety issue. Ecotoxicology and environmental safety 2004, 59, 44–56. [CrossRef]

- Ostovar, M.; Saberi, N.; Ghiassi, R. Selenium contamination in water; analytical and removal methods: a comprehensive review. Separation Science and Technology 2022, 57, 2500–2520. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/360585296_Selenium_contamination_in_water_analytical_and_removal_methods_a_comprehensive_review. [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, B.R.; Cominetti, C.; Seale, L.A. Editorial: Selenium, Human Health and Chronic Disease. Frontiers in Nutrition 2022, 8, 827759. [CrossRef]

- Kieliszek, M.; Bano, I. Selenium as an important factor in various disease states-a review. EXCLI journal 2022, 21, 948–966. [CrossRef]

- Haug, A.; Graham, R.D.; Christophersen, O.A.; Lyons, G.H. How to use the world’s scarce selenium resources efficiently to increase the selenium concentration in food. Microbial Ecology in Health and Disease 2007, 19, 209-228. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Wang, T.; Li, Q.; Li, D. Prevention of Keshan Disease by selenium Supplementation: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Biological Trace Element Research 2018, 186, 98–105. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yin, J.; Yang, B.; Qu, C.; Lei, J.; Han, J.; Guo, X. Serious selenium Deficiency in the Serum of Patients with Kashin-Beck Disease and the Effect of Nano-selenium on Their Chondrocytes. Biological Trace Element Research 2019, 194, 96–104. [CrossRef]

- Pillai, R.; Uyehara-Lock, J.H.; Bellinger, F.P. Selenium and selenoprotein function in brain disorders. IUBMB Life 2014, 66, 229–239. [CrossRef]

- Avery, J.C.; Hoffmann, P.R. Hoffmann, Selenium, Selenoproteins, and Immunity. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1203. [CrossRef]

- Ghafarizadeh, A.A.; Vaezi, G.; Shariatzadeh, M.A.; Malekirad, A.A. Effect of in vitro selenium supplementation on sperm quality in asthenoteratozoospermic men. Andrologia 2017, 50, e12869. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Roh, Y.J.; Han, S.-J.; Park, I.; Lee, H.M.; Ok, Y.S.; Lee, B.C.; Lee, S.-R. Role of Selenoproteins in Redox Regulation of Signaling and the Antioxidant System: A Review. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 383. [CrossRef]

- Kuršvietienė, L.; Mongirdienė, A.; Bernatonienė, J.; Šulinskienė, J.; Stanevičienė, I. Selenium Anticancer Properties and Impact on Cellular Redox Status. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 80. [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Hossain, M.A.; Fujita, M. Exogenous selenium pretreatment protects rapeseed seedlings from cadmium-induced oxidative stress by upregulating antioxidant defense and methylglyoxal detoxification systems. Biological Trace Element Research 2012, 149, 248–261. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Ding, J.; Shi, Y.; Fang, Y.; Li, P.; Fan, F.; Wu, J.; Hu, Q. Deciphering the role of selenium-enriched rice protein hydrolysates in the regulation of Pb2+-induced cytotoxicity: an in vitro Caco-2 cell model study. International Journal of Food Science and Technology 2021, 56, 420–428. [CrossRef]

- Ruj, B.; Bishayee, B.; Chatterjee, R.P.; Mukherjee, A.; Saha, A.; Nayak, J.; Chakrabortty, S. An economical strategy towards the managing of selenium pollution from contaminated water: A current state-of-the-art review. Journal of Environmental Management 2022, 304, 114143. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhong, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, N.; Chen, X.; Wang, F.; Wang, L.; Chen, C.; He, J. Li, S. Gut microbiota: a new perspective for bioavailability of selenium and human health. npj Sci Food 2025, 9, 228. [CrossRef]

- Vinceti, M.; Mazzoli, R.; Wise, L.A.; Veneri, F.; Filippini, T. Calling for a comprehensive risk assessment of selenium in drinking water. Science of The Total Environment 2025, 966, 178700. [CrossRef]

- Niu, J.; Zuo, G.; Xia, Z.; Yang, J.; Hu, Y.; Liu, G.; Sun, L. Selenium-enriched livestock and poultry products for human health (in Chinese). Scientia Sinica Vitae, 2025, 55: 508–517. [CrossRef]

- China Administration for Market Regulation Standardization Administration. Standard examination methods for drinking water - Part 6: Metal and metalloid indices (GB/T 5750.6-2023). China National Standard, Beijing, china, 2023. https://openstd.samr.gov.cn/bzgk/gb/newGbInfo?hcno=198D49FEEC0BD7ED8A39773C9F516AFE.

- SEPA. Water quality - Determination of total selenium 3,3’-Diaminobenzidine spectrophotometric method (HJ811-2016), China Environmental Protection Administration, China National Standard, Beijing, china, 2016. https://std.samr.gov.cn/hb/search/stdHBDetailed?id=A2B6DC4932F1C601E05397BE0A0A633C.

- Ministry of Water Resources of China. Water quality- Determination of total selenium Iron(I)-O-phenanthroline indirect spectrophotometry (ST/L 272-2001). China National Standard, Beijing, china,2001. https://file4.foodmate.net/foodvip/zengbu/SLT272-2001.pdf.

- MEP. Water quality determination of 65 elements- Inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (HJ700-2014). China National Standard, Beijing, china, 2014. https://file4.foodmate.net/foodvip/biaozhun/2015/HJ700-2014.pdf.

- Abdolmohammad-Zadeh, H.; Jouyban, A.; Amini, R.; Sadeghi, G. Nickel-aluminum layered double hydroxide as a nano-sorbent for the solid phase extraction of selenium, and its determination by continuous flow HG-AAS. Microchimica Acta 2013, 180, 619–626. [CrossRef]

- Ali, J.; Tuzen, M.; Feng, X.; Kazi, T.G. Determination of trace levels of selenium in natural water, agriculture soil and food samples by vortex assisted liquid-liquid microextraction method: multivariate techniques. Food Chemistry 2021, 344, 128706. [CrossRef]

- Muslim, N.M.; Abbood, F.K.; Hammood, N.H.; Azooz, E.A. Air-assisted solidified floating organic drop microextraction method based on green supramolecular solvent for arsenic and selenium quantification in water and food samples. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2024, 134, 106558. [CrossRef]

- Muhammet, A.; Dilek, Y. Novel palladium coated tungsten coil atom trap for ultra-trace determination of selenium by hydride generation atomic absorption spectrometry (HGAAS). Analytical Letters 2024, 57, 1892–1906. [CrossRef]

- Marco, V.; Riccardo, M.; Lauren, A. Wise, Federica Veneri, Tommaso Filippini, Calling for a comprehensive risk assessment of selenium in drinking water. Science of The Total Environment 2025, 966, 178700. [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.Y.; Yan, X.P.; Zhang, Z.P.; Wang, Z.P.; Liu, L.W. Flow injection on-line sorption preconcentration coupled with hydride generation atomic fluorescence spectrometry using a polytetrafluoroethylene fiber-packed microcolumn for determination of Se(IV) in natural water. Journal of Analytical Atomic Spectrometry 2004, 19, 277–281. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Luo, X.; Tang, J.; Hu, X. Determination of Se(IV) using solidified floating organic drop microextraction coupled to ultrasound-assisted back-extraction and hydride generation atomic fluorescence spectrometry. Microchimica Acta 2011, 173, 267–273. [CrossRef]

- Serra, A.M.; Estela, J.M.; Coulomb, B.; Boudenne, J.L.; Cerdà,V. Solid phase extraction - Multisyringe flow injection system for the spectrophotometric determination of selenium with 2,3-diaminonaphthalene. Talanta 2010, 81, 572–577. [CrossRef]

- Feng, G.; Dai, Y.; Jin, H.; Xue, P.; Huan, Y.; Shan, H.; Fei, Q. A highly selective fluorescent probe for the determination of Se(IV) in multivitamin tablets. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2014, 193, 592–598. [CrossRef]

- Thakur, A.; Devi, P. A Novel Fluorescent “Turn-Off” Probe for selenium (IV) Detection in Water and Biological Matrix. Transactions of the Indian National Academy of Engineering 2021, 6, 255–263. [CrossRef]

- Aimaitiniyazi, M.; Muhammad, T.; Yasen, A.; Abula, S.; Dolkun, A.; Tursun, Z. Determination of selenium in Selenium-Enriched Products by Specific Ratiometric Fluorescence. Sensors 2023, 23, 9187. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Xie, Wei.; Su, H.; Huang, Z. Determination of selenium content in Lisong hot spring water by UV-visible spectrophotometry. Modern Chemical Industry (in China), 2018, 38, 233–235. https://link.cnki.net/doi/10.16606/j.cnki.issn0253-4320.2018.04.054.

- Sounderajan, S.; Kumar, K.G.; Udas, A. Cloud point extraction and electrothermal atomic absorption spectrometry of Se(IV)-3,3′-diaminobenzidine for the estimation of trace amounts of Se(IV) and Se(VI) in environmental water samples and total selenium in animal blood and fish tissue samples. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2009, 175, 666–672. [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, K.; Patel, K.S.; Shrivas, K. Development of surfactant assisted spectrophotometric method for determination of selenium in waste water samples. Journal of hazardous materials 2009, 161, 1245–1249. [CrossRef]

- Nayanova, E.V.; Sergeev, G.M.; Elipasheva, E.V. Selective photometric determination of low conentrations of selenium (IV) and selenium (VI) in bottled drinking water. Journal of Analytical Chemistry 2016, 71, 379–385. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Li, F.; Wang, J.; Huang, A.; Wu, M.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, D.; Xie, W.; Duan, Z.; Su, L. Simple multimodal detection of selenium in water and vegetable samples by catalytic chromogenic method. Analytical Methods 2018, 10, 2102–2107. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Pu, S.; Ma, B.; Zou, X.; Xiong, Q.; Hou, X.; Xu, K. Selenium hydride-induced oxidase-like activity inhibition of amorphous/crystalline manganese dioxide: Colorimetric assay for selenium detection. Analytical Chemistry 2024, 96, 18718–18726. [CrossRef]

- Breuninger, E.S.; Tolu, J.; Bouchet, S.; Winkel, L.H.E. Sensitive analysis of selenium speciation in natural seawater by isotope-dilution and large volume injection using PTV-GC-ICP-MS, Analytica Chimica Acta 2023, 1279, 341833. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Bravo, Y.; Roig-Navarro, A.F.; López, F.J.; Hernández, F. Multielemental determination of arsenic, selenium and chromium (VI) species in water by high-performance liquid chromatography–inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Journal of Chromatography A 2001, 926, 265–274. [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Hu, Z.; Xu, F.; Geng, D.;Tang, X. MIL-125-NH2 catalyzed photochemical vapor generation coupled with HPLC-ICPMS for speciation analysis of selenium. Microchemical Journal 2022, 174, 107053. [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Zheng, R.; Yang, R.; Yu, S.; Xiao, J.; Liu, J. Species selective concentration and determination of nano-selenium and inorganic selenium species in environmental waters by micropore membrane filtration and ICP-MS. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 2024, 416, 3271–3280. [CrossRef]

- Devi, P.; Jain, R.; Thakur, A.; Kumar, M.; Labhsetwar, N.K.; Nayak, M.; Kumar, P. A systematic review and meta-analysis of voltammetric and optical techniques for inorganic selenium determination in water. Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2017, 95, 69–85. [CrossRef]

- Fakude, C. T.; Arotiba, O. A.; Moutloali, R.; Mabuba, N. Nitrogen-doped graphene electrochemical sensor for selenium (IV) in water. International Journal of Electrochemical Science 2019, 14, 9391–9403. [CrossRef]

- Galal, A. A.; Fatehy, A. M.; Mohamed, B. A.; Ali, A. G.; Altahan, M. F. Voltammetric and impedimetric determinations of selenium(IV) by an innovative gold-free poly(1-aminoanthraquinone)/multiwall carbon nanotube-modified carbon paste electrode. RSC Advances 2022, 12, 4988–5000. [CrossRef]

- Ma6rtins, F. C. O. L.; De Souza, D. Ultrasensitive determination of selenium in foodstuffs and beverages using an electroanalytical approach. Microchemical Journal 2021, 164, 105996. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, J.; Liu, J.; Yu, H.; Yang, Z.; Liu, W.; Liu, A. Pyridine-assisted electrodeposition of Au (111)-dominant gold nanonetworks on glassy carbon electrode for anodic stripping voltammetry analysis of as (III), se (IV) and cu (II). Microchemical Journal 2024, 200, 110311. [CrossRef]

- Ashournia, M.; Aliakbar, A. Determination of selenium in natural waters by adsorptive differential pulse cathodic stripping voltammetry. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2009, 168, 542–547. [CrossRef]

- Ashournia, M.; Aliakbar, A.Determination of Se(IV) in natural waters by adsorptive stripping voltammetry of 5-nitropiazselenol. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2010, 174, 788–794. [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, A.A.; Mandil, H.; Ozoun, A. Differential Pulse Anodic Stripping Voltammetric Determination of Selenium(IV) With a Vitamin E-Nafion Modified Gold Electrode. Asian Journal of Chemistry 2011, 23, 843–846. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/286162488.

- Ramadan, A.A.; Mandil, H.; Ozoun, A. Differential Pulse Anodic Stripping Voltammetric Determination of Selenium(IV) with A Methylene Blue-Nation Modified Gold Electrode. Asian Journal of Chemistry 2012, 24, 391–394. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/286163779.

- Ramadan, A.A.; Mandil, H.; Shikh-Debes, A.A. Differential Pulse Anodic Stripping Voltammetric Determination of Selenium(IV) at a Gold Electrode Modified With 3,3′-Diaminobenzidine. 4HCl-Nafion. International Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences 2014, 6, 148–153. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282406465.

- Ramadan, A.A.; Mandil, H.; Shikh-Debes, A. Abdulrahman, Differential pulse anodic stripping voltammetric analysis of selenium (IV) at a gold electrode modified with O-Phenylenediamine-Nafion. Research Journal of Pharmacy and Technology 2018, 11, 2030–2035. [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Wu, W.; Yin, N.; Jia, M.; Chen, X.; Bai, Y.; Wu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Li, P. Determination of selenium in food and environmental samples using a gold nanocages/fluorinated graphene nanocomposite modified electrode. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2020, 94, 103628. [CrossRef]

- Yue, S.; Wang, X.; Xue, Q.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, N. Highly efficient detection of tetravalent selenium in water using manganese dioxide and copper nanoparticles modified glassy carbon electrode. Microchemical Journal 2025, 215, 114362. [CrossRef]

- Nakakubo, K.; Nishimura, T.; Biswas, F.B.; Endo, M.; Wong, K.H.; Mashio, A.S.; Taniguchi, T.; Nishimura, T.; Maeda, K.; Hasegawa, H. Speciation analysis of inorganic selenium in wastewater using a highly selective cellulose-based adsorbent via liquid electrode plasma optical emission spectrometry. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2022, 424, 127250. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Dong, Y.; Yu, X.; Ai, Q.; Yuan, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, D. Highly selective localized surface plasmon resonance sensor for selenium diagnosis in selenium-rich soybeans. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2024, 478, 135632. [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Dias, A.C.P.; Zhang, X. Monoclonal antibody based immunoassay: an alternative way for aquatic environmental selenium detection. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 858, 159909. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |