1. Introduction

Urology residency training is undergoing rapid evolution globally as advances in surgical technology, expanding sub-specialization, and increasing expectations for procedural competence reshape the demands placed on trainees (1–3). Significant differences still persist across countries in the structure and delivery of urological education, including operative exposure, simulation resources, academic requirements, and systems of competency assessment (4). These disparities carry important implications for resident preparedness and for the quality and consistency of urological care worldwide. Global efforts to modernize and harmonize training are ongoing, yet reliable comparative data on how urology residents experience their training in different regions remain scarce (5–9).

Understanding trainee perspectives, including perceived preparedness, learning preferences, training satisfaction, and career expectations, is essential for informing future reforms and for aligning educational strategies with the realities of contemporary practice (2,10).

To address this lack of cross-national trainee-level data, we conducted an international online survey submitted to urology residents from 21 different countries, on the occasion of a major urological congress held in Florence in November 2024 by the Société Internationale d'Urologie (SIU) (SIU Regional Meeting: Residents). The survey systematically examined program characteristics, clinical and surgical training exposure, self-reported abilities, educational preferences, and resident perceptions of the adequacy of their training. By capturing perspectives from trainees across diverse health systems and cultural contexts, this study provides an updated and comprehensive overview of global urology residency training. The findings aim to inform ongoing efforts to improve training quality, promote greater equity in educational opportunities, and support the development of harmonized international standards for urological education.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey and Target Population

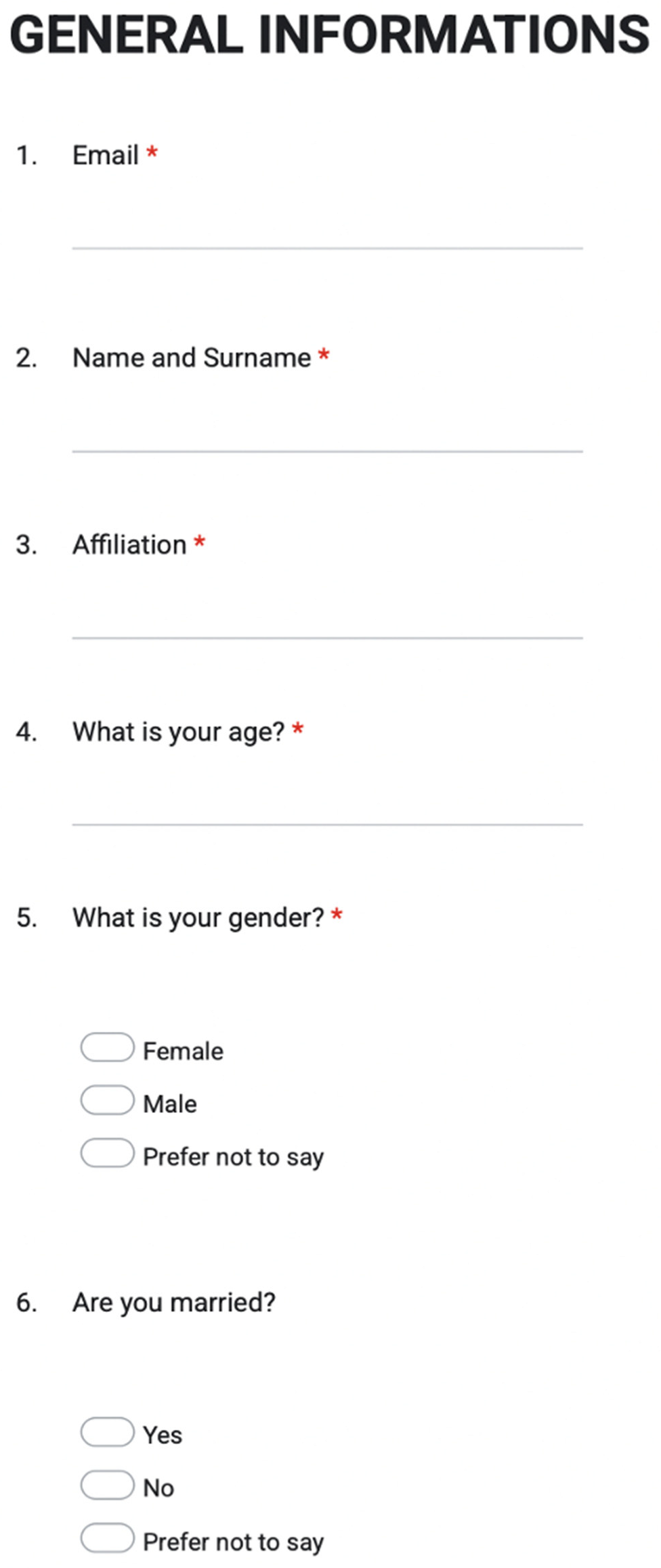

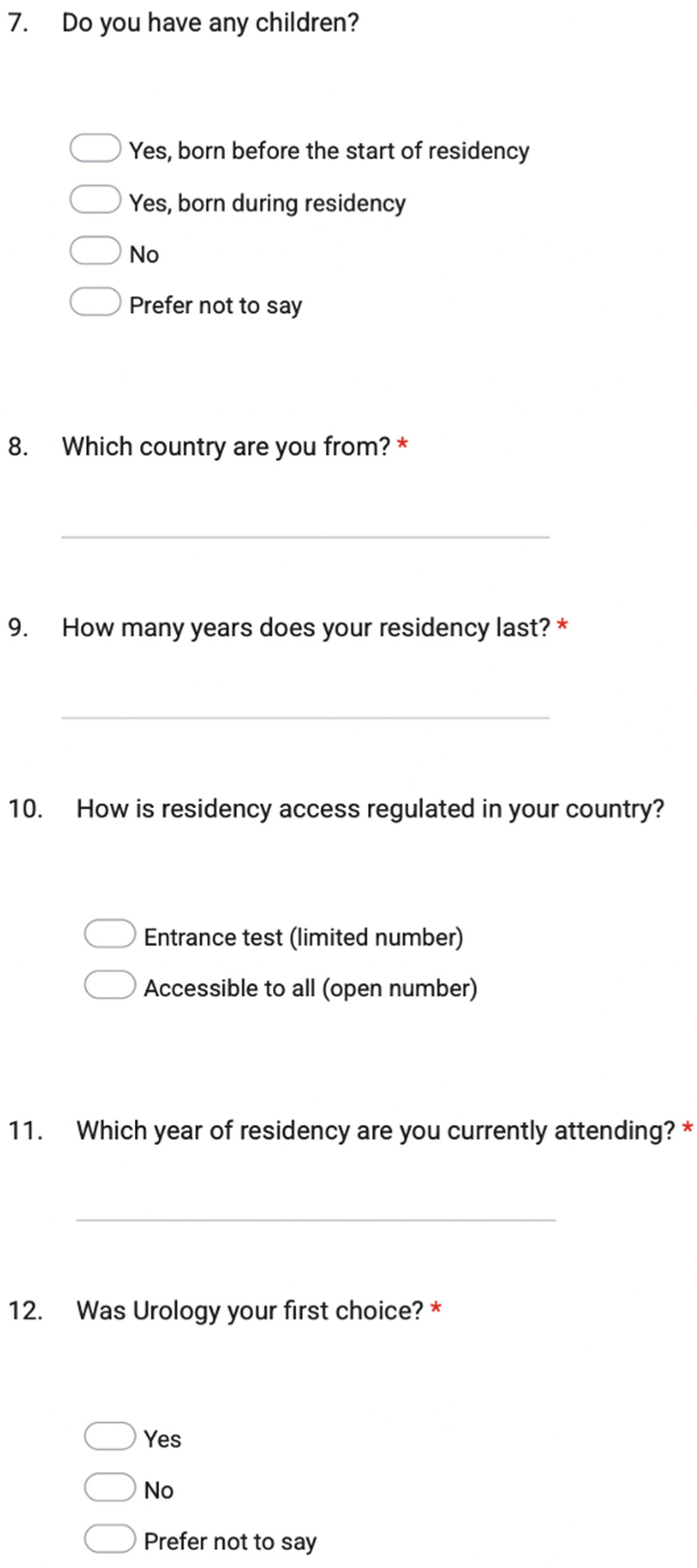

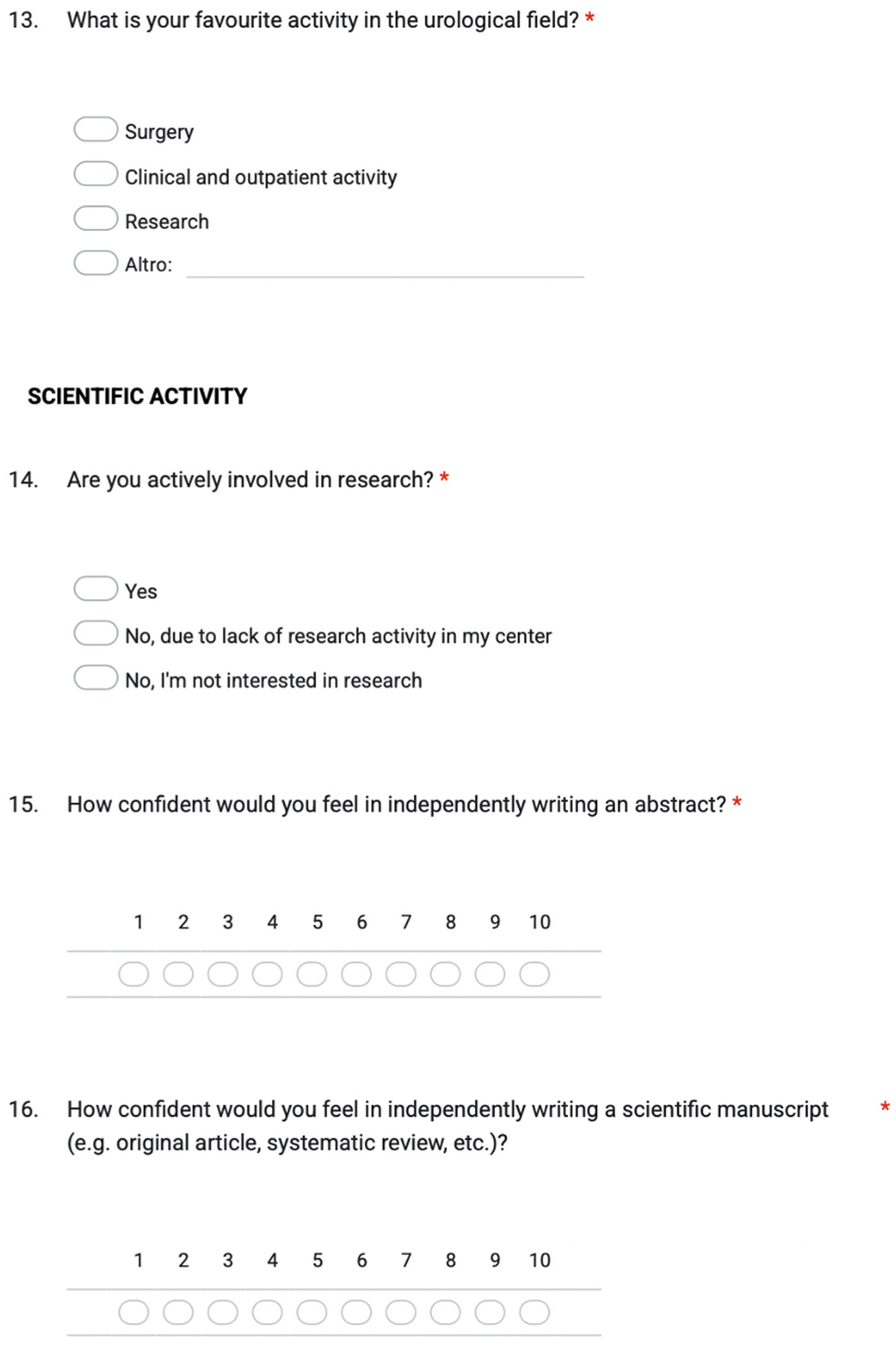

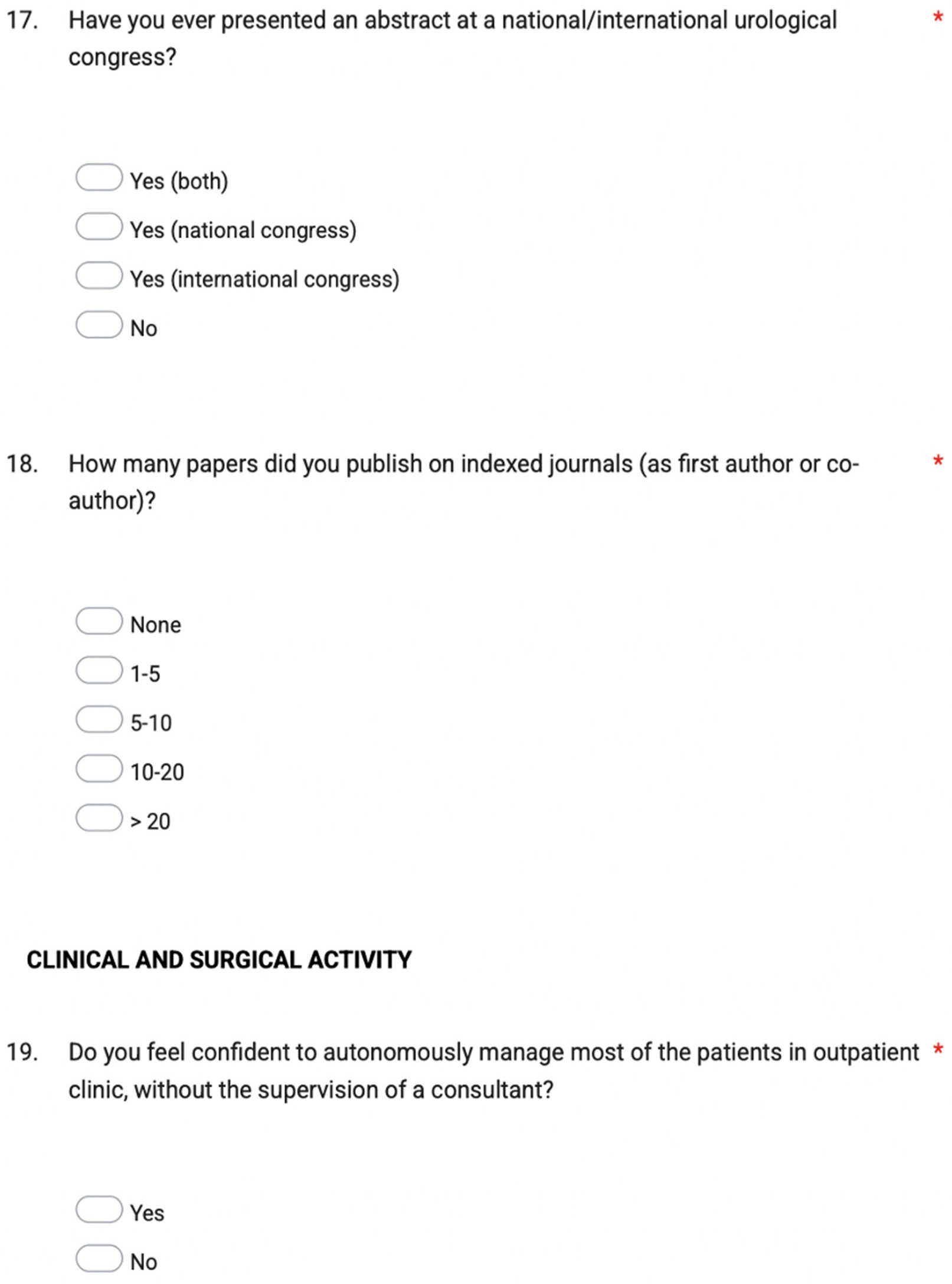

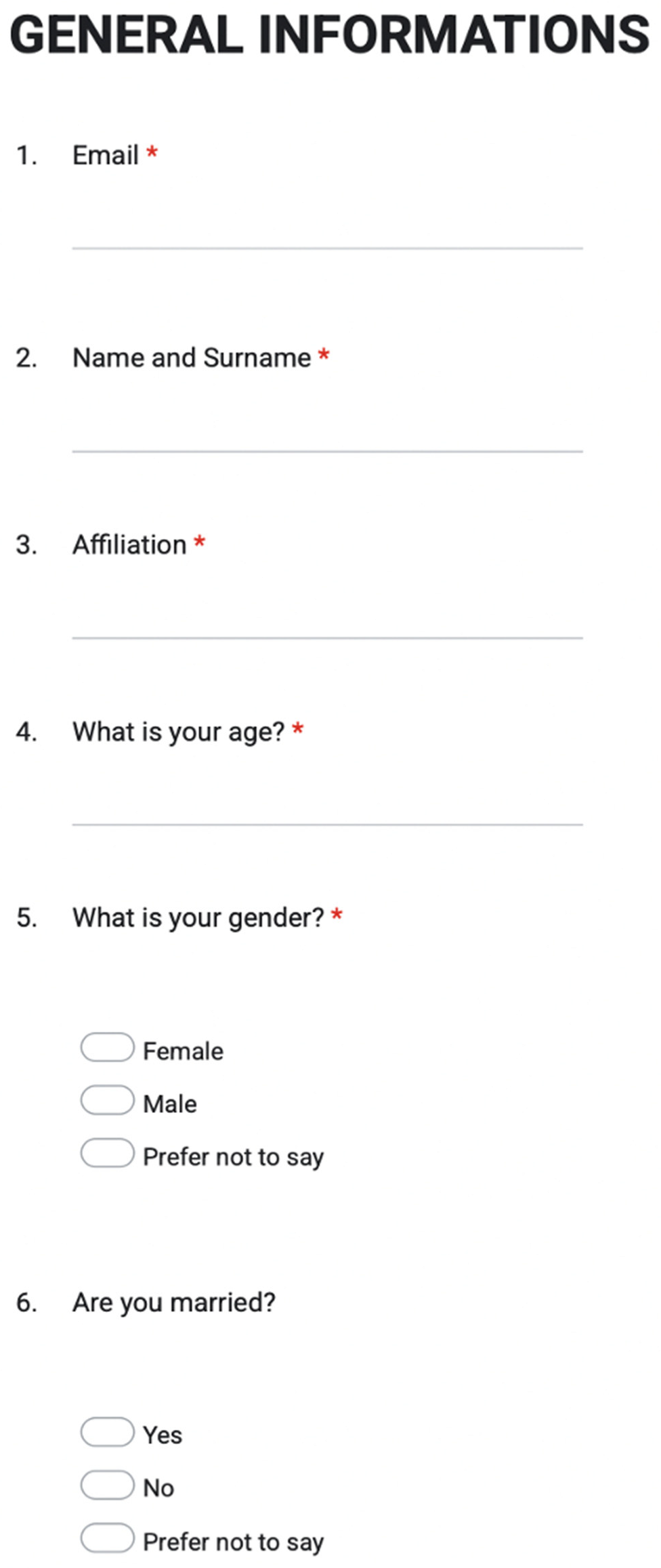

A voluntary invitation to an online survey (using Google Form) consisting of 39 questions was submitted to all urology residents on the occasion of a major urological congress held in Florence in November 2024 (SIU Regional Meeting: Residents).

Questions selected by the authors covered the main aspects of urology residency. Two Italian urology opinion leaders reviewed the quality of the survey (M.G and S.S.), and the survey was tested before its administration to assess usability and functionality.

The survey was conducted according to the Checklist for reporting results of internet e-Surveys (CHERRIES) (11).

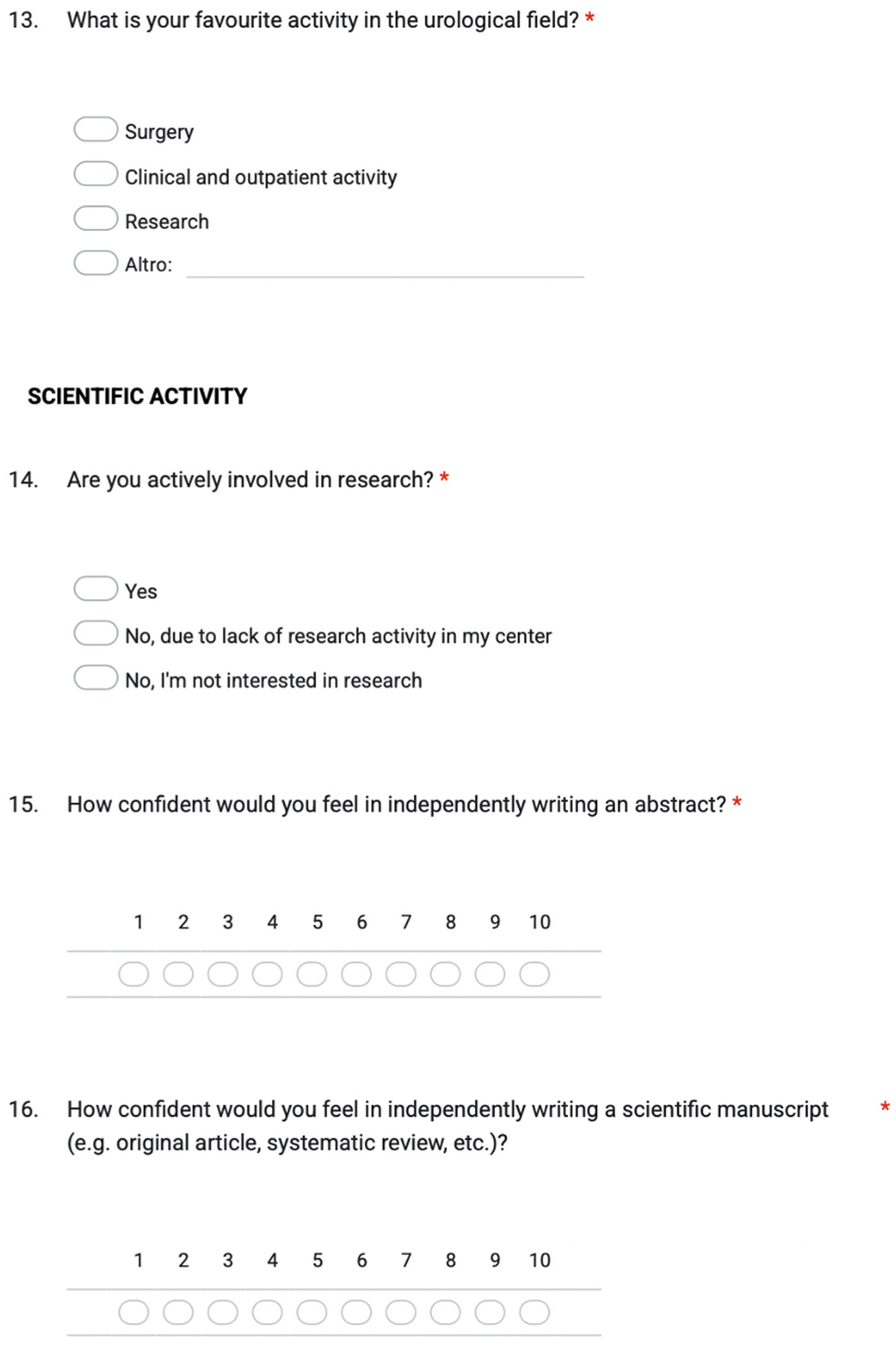

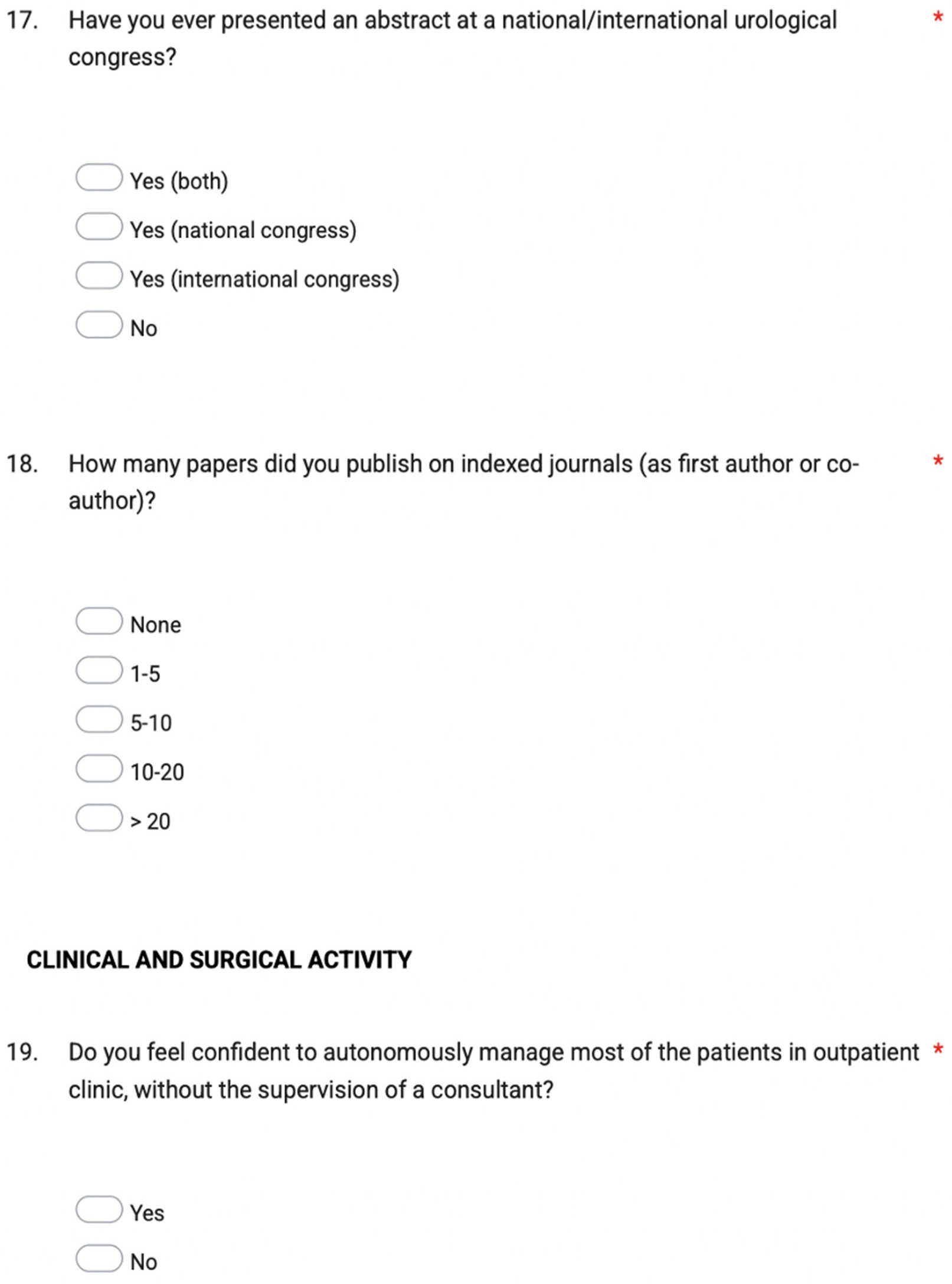

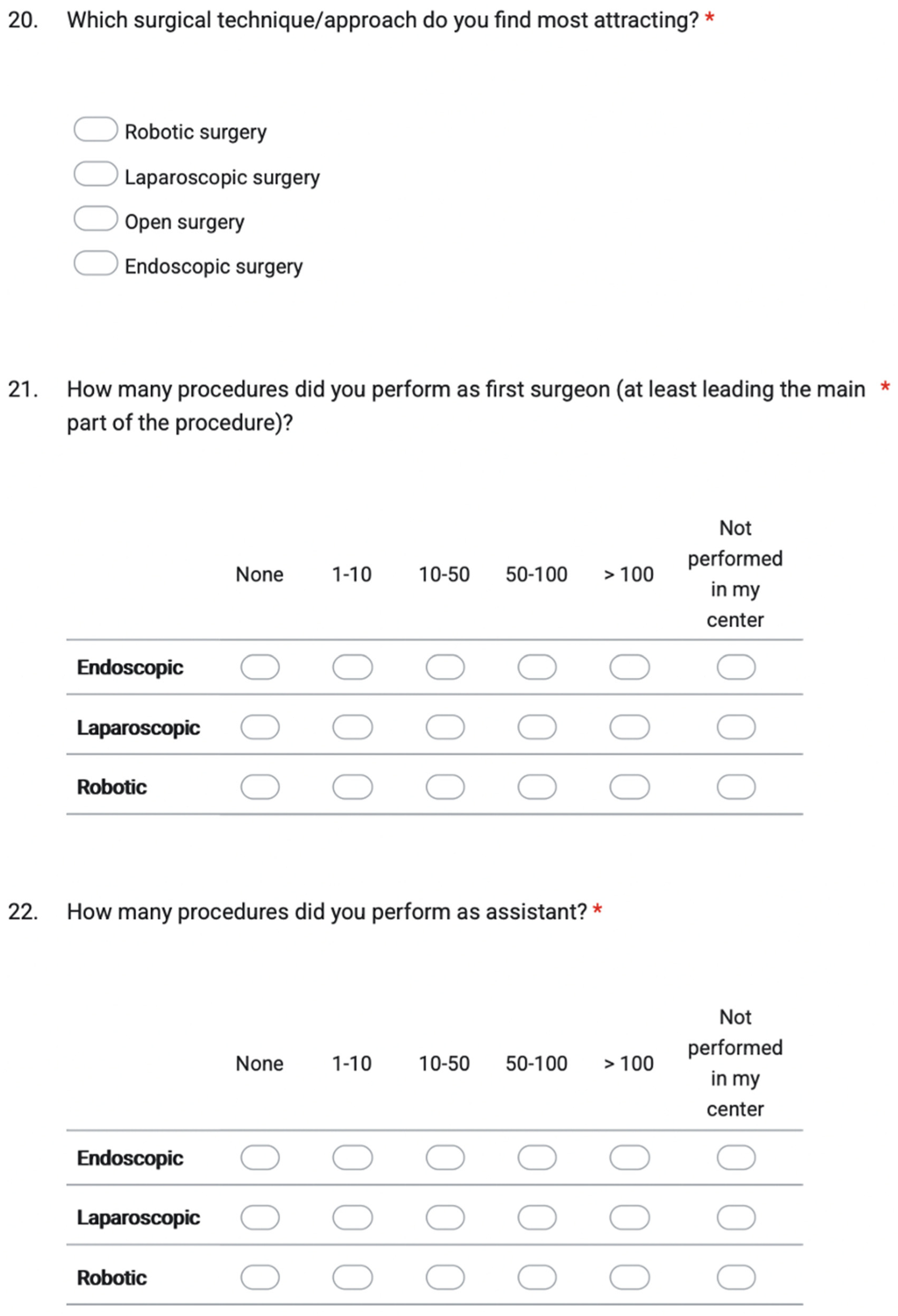

The questionnaire was divided into 5 sections: 1) General information and respondents’ demographics; 2) Scientific activity; 3) Clinical and surgical activity; 4) Residency training program, workload and international fellowship; 5) Satisfaction and future perspectives.

The survey was formulated as multiple choice, open-ended, or Likert scale questions, as appropriate. The complete list of questions of the survey is available in Supplementary Figure 1.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software version V28.0.1.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive analysis used frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Medians and interquartile range (IQR) were reported for continuous variables.

Comparisons between trainees at different postgraduate year (PGY) were performed using the χ² test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. For continuous variables, Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U-Test were used. Likert-scale items assessing attitudes, preferences, and perceived abilities were treated as ordinal variables. Between-group differences in Likert responses were evaluated using nonparametric tests (Mann–Whitney U or Kruskal–Wallis).

To explore associations between demographic or program characteristics and key outcomes, univariable and multivariable logistic regression models were constructed. Statistically significant co-variates at univariable level were further tested in the multivariable models.

All tests were two-tailed, and a p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Baseline Characteristics of the Study Cohort

Statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software version V28.0.1.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive analysis used frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Medians and interquartile range (IQR) were reported for continuous variables.

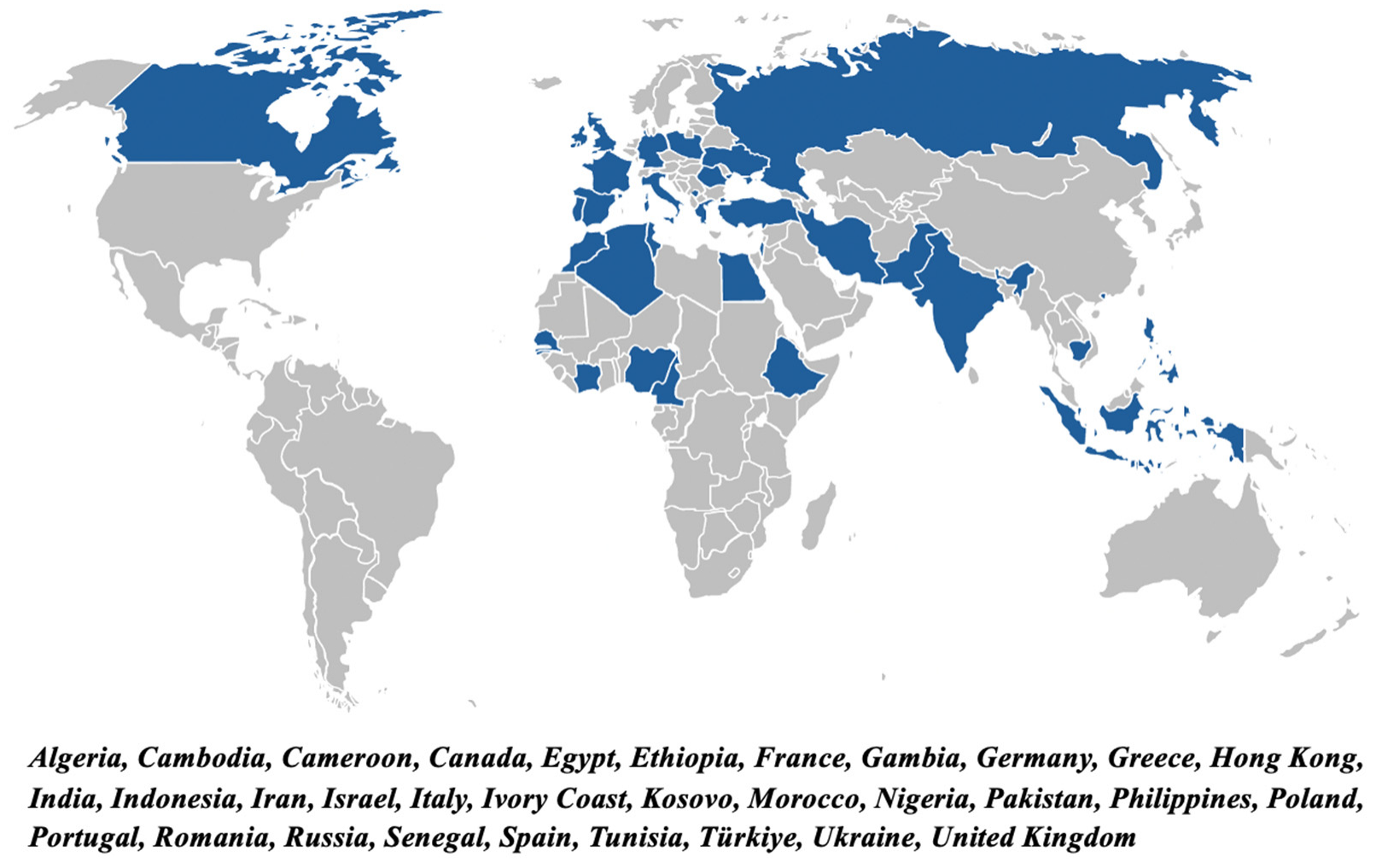

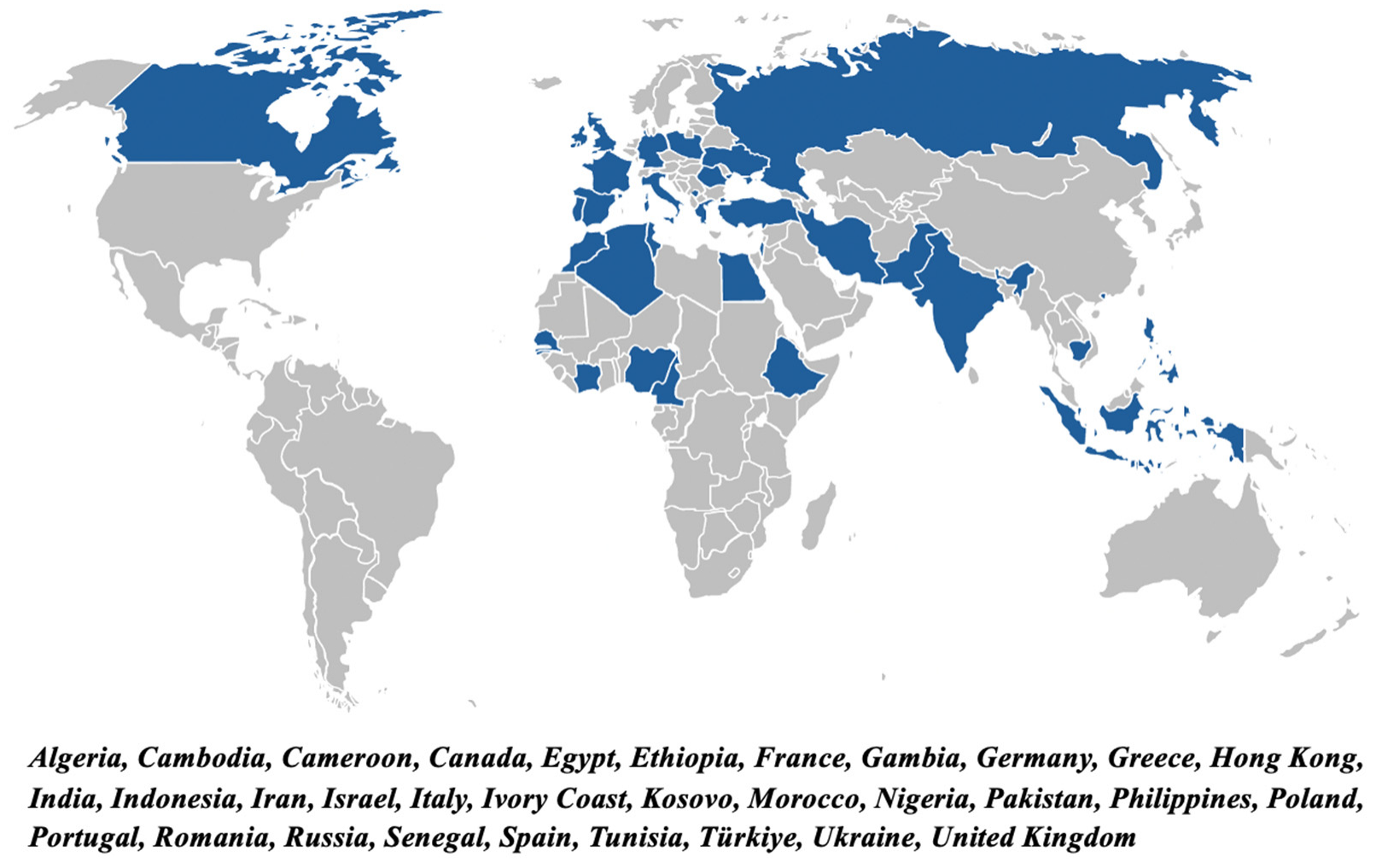

Overall, 415 urology residents from 32 different countries across Europe, Asia, Africa and North America attended the congress (SIU Regional Meeting: Residents) on November 22 and 23, 2025. Of these, 208 (50%) participants from 21 different countries completed the online survey. Supplementary Figure 2 depicts the geographic distribution of participating urology residents by country of origin.

The majority of residents who attended the congress and completed the survey were males (n = 147 – 70.7%), while females were less represented (n = 61 – 29.3%). Median age was 29 years (IQR: 28–31). Of these, 4.8% (10/208), 15.4% (32/208), 20.7% (43/208), 39.4% (82/208), 18.3% (38/208), and 1.4% (3/208) were PGY -1, -2, -3, -4, -5, and -6, respectively.

Table 1 reports descriptive data of the urology residents who completed the survey.

3.2. Scientific Activity and Research

When questioned about their involvement in research and scientific activity most of the residents reported being actively engaged (159/208, 76.4%), while only a minority were not involved because not interested (11/208, 5.3%) or due to lack of research activity in their center, despite their willingness to actively participate (38/208, 18.3%).

Most of the trainees interviewed had already presented scientific papers/abstracts at national (70/208, 33.7%), international (5/208, 2.4%) or both (59/208, 28.4%) congresses, while 35.6% (74/208) did not have any experience in such field.

When they were asked “How confident would you feel in independently writing an abstract (on a scale 1-10)?” 63 (30.3%) trainees replied with a rate < 6 (median 7, IQR 5-8). Stratifying these scores by PGY, a significant association was found between PGY and residents’ perceived confidence in independently writing an abstract (p = 0.008). Post-hoc pairwise comparisons showed statistically significant difference between PGY5 and PGY<3 residents (p<0.05), with younger trainees reporting substantially lower levels of confidence. Similarly, most of the participants replied to the question: “How confident would you feel in independently writing a scientific manuscript (e.g. original article, systematic review, etc.) (on a scale 1-10)?” with a median score of 6 (IQR: 4-7). Of the 208 residents included, 139 replied with a rate < 6, highlighting a non-negligible insecurity in scientific production and research.

We then investigated how many articles were published on indexed journals (as first author or co-author): 22.1% (46/208) reported they never participated in a publication, while 97 (46.6%), 35 (16.8%), 20 (9.6%), and 10 (4.8%) residents published 1-5, 5-10, 10-20, or >20 papers, respectively. Stratifying by PGY, a statistically significant association (p = 0.0004) between year of residency and the number of scientific publications emerged. The distribution of publication varied across training levels, with early-year residents predominantly reporting “no publications” or “1–5 publications”, whereas senior residents (PGY4–5) were more active in scientific production (5–10, 10–20, and >20 papers).”

Table 2.

reports data on the involvement in research and scholarly work of the urology residents.

Table 2.

reports data on the involvement in research and scholarly work of the urology residents.

| Table 2. Resident Involvement in Research and Scientific Activities. |

|---|

“Are you actively involved in research?”, n (%)

Yes

No, lack of research activity in my center

No, not interested in research |

159 (76.4)

38 (18.3)

11 (5.3) |

“How confident would you feel in independently writing an abstract

(on a scale 1-10)?”, median (IQR) |

7 (5-8) |

“How confident would you feel in independently writing a scientific manuscript (e.g. original article, systematic review, etc.)

(on a scale 1-10)?”, median (IQR) |

6 (4-7) |

“Have you ever presented an abstract at a national/international urological congress?”, n (%)

Yes, only national congress

Yes, only international congress

Yes, both national and international congresses

No |

70 (33.7)

5 (2.4)

59 (28.4)

74 (35.6) |

“How many papers did you publish on indexed journals

(as first author or co-author)?”, n (%)

None

1-5 papers

5-10 papers

10-20 papers

> 20 papers |

46 (22.1)

97 (46.6)

35 (16.8)

20 (9.6)

10 (4.8) |

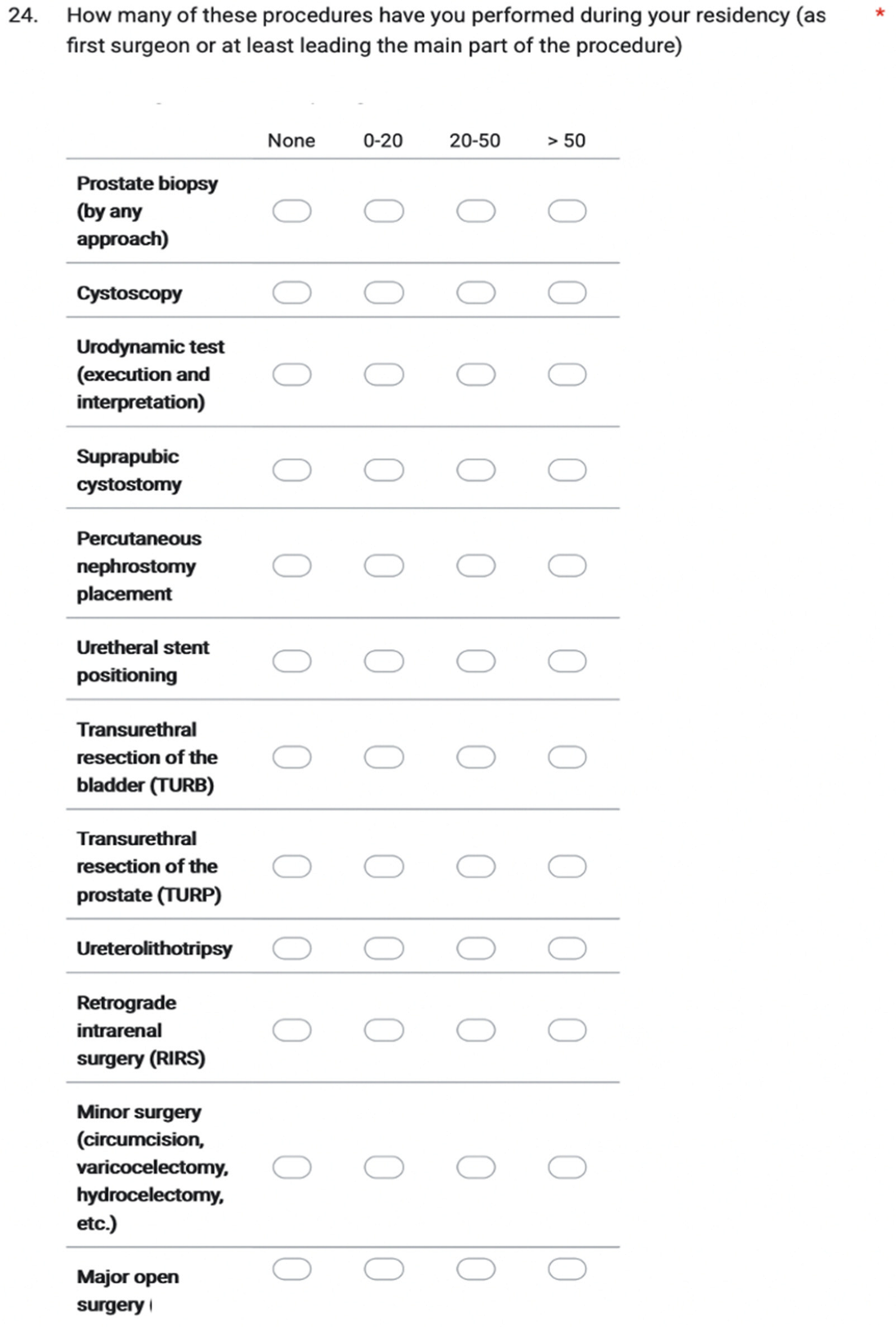

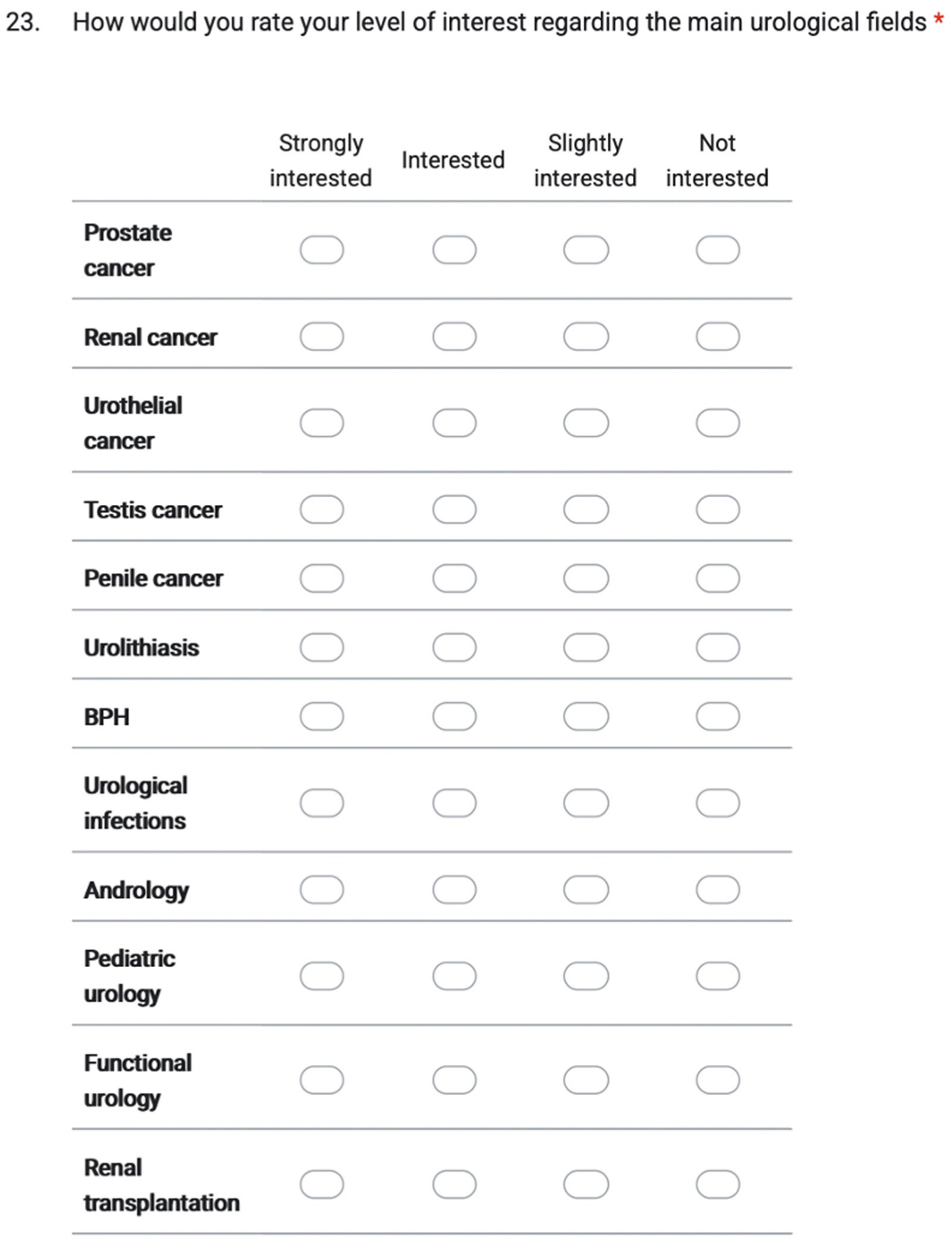

3.3. Urological Fields of Interest

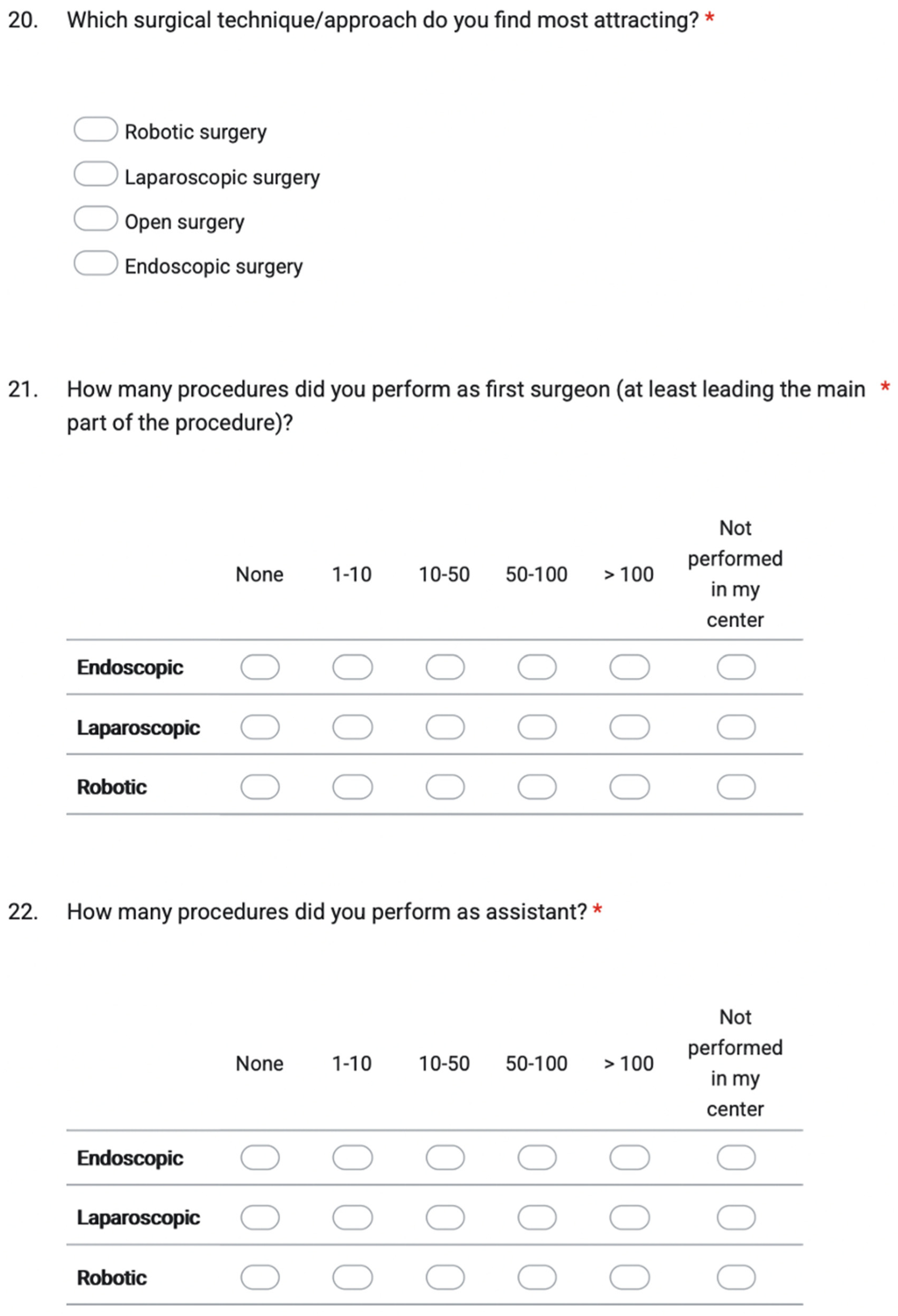

We asked the trainees: “Which surgical technique/approach do you find most attracting?”. The order of preferences among the 208 participants to the survey was robotic surgery (98/208, 47.1%), endoscopy (73/208, 35.1%), open surgery (21/208, 10.1%), and laparoscopy (16/208, 7.7%). No significant difference was assessed stratifying residents according to PGY.

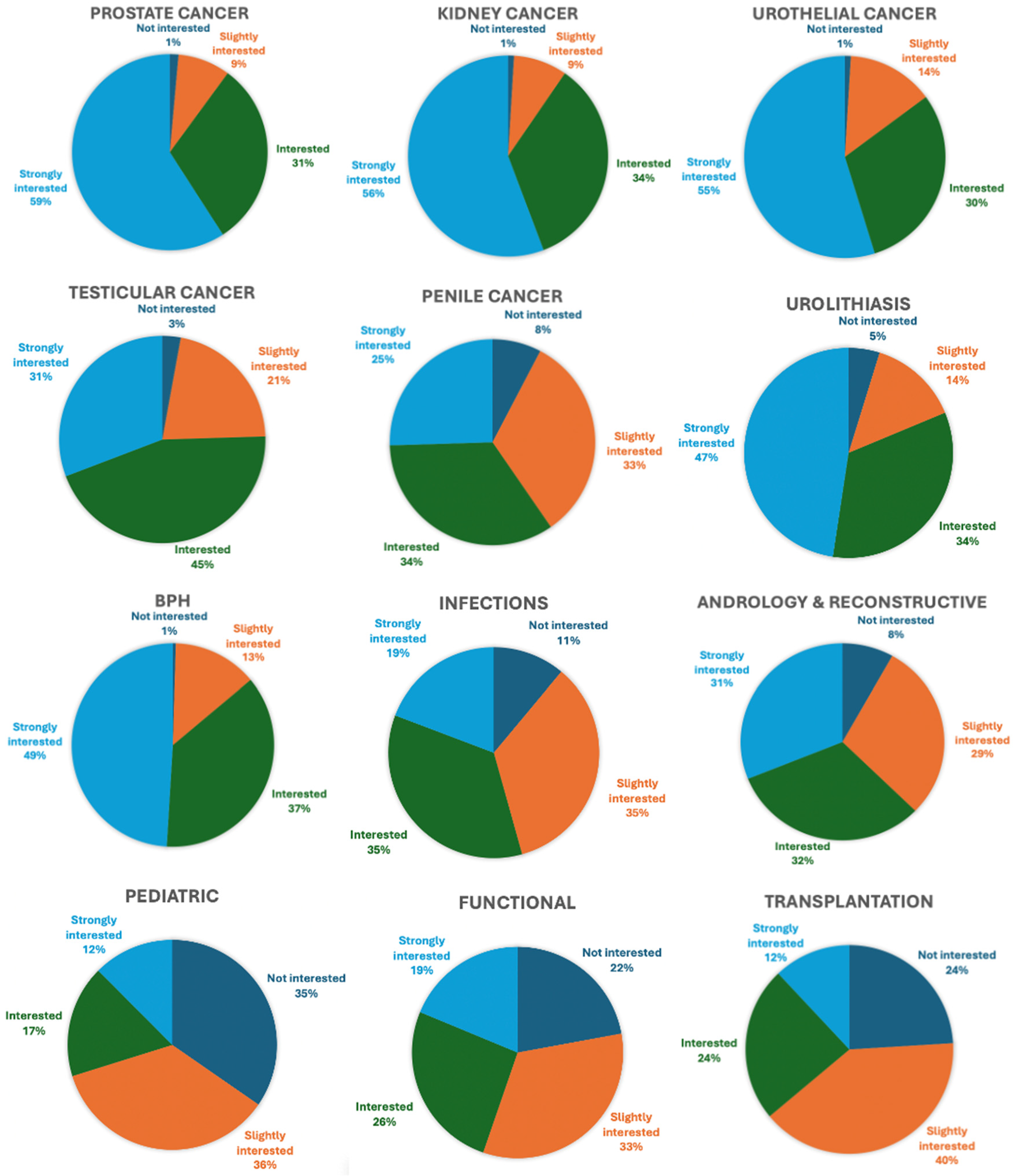

Data on the level of interest in specific urologic topics were collected using a 4-items Likert Scale (Not interested / Slightly interested / Interested / Strongly interested). The most attracting topics were prostate, kidney and urothelial cancers (> 55% of residents declared being “strongly interested”, while only 1% was “not interested” in these fields), followed by BPH (49% “strongly interested” and only 1% “not interested”) and urolithiasis (47% “strongly interested”, 5% “not interested”). According to the results of the survey, pediatric, transplantation and functional urology were the less appealing subspecialties (< 50% of responders being at least “Interested”). Overall data on the main urological fields and the level of interest reported by residents are depicted in

Figure 1.

Stratifying the interest ratings according to PGY, no statistically significant differences emerged between the various groups of residents and the individual urological topics (p > 0.05 for all).

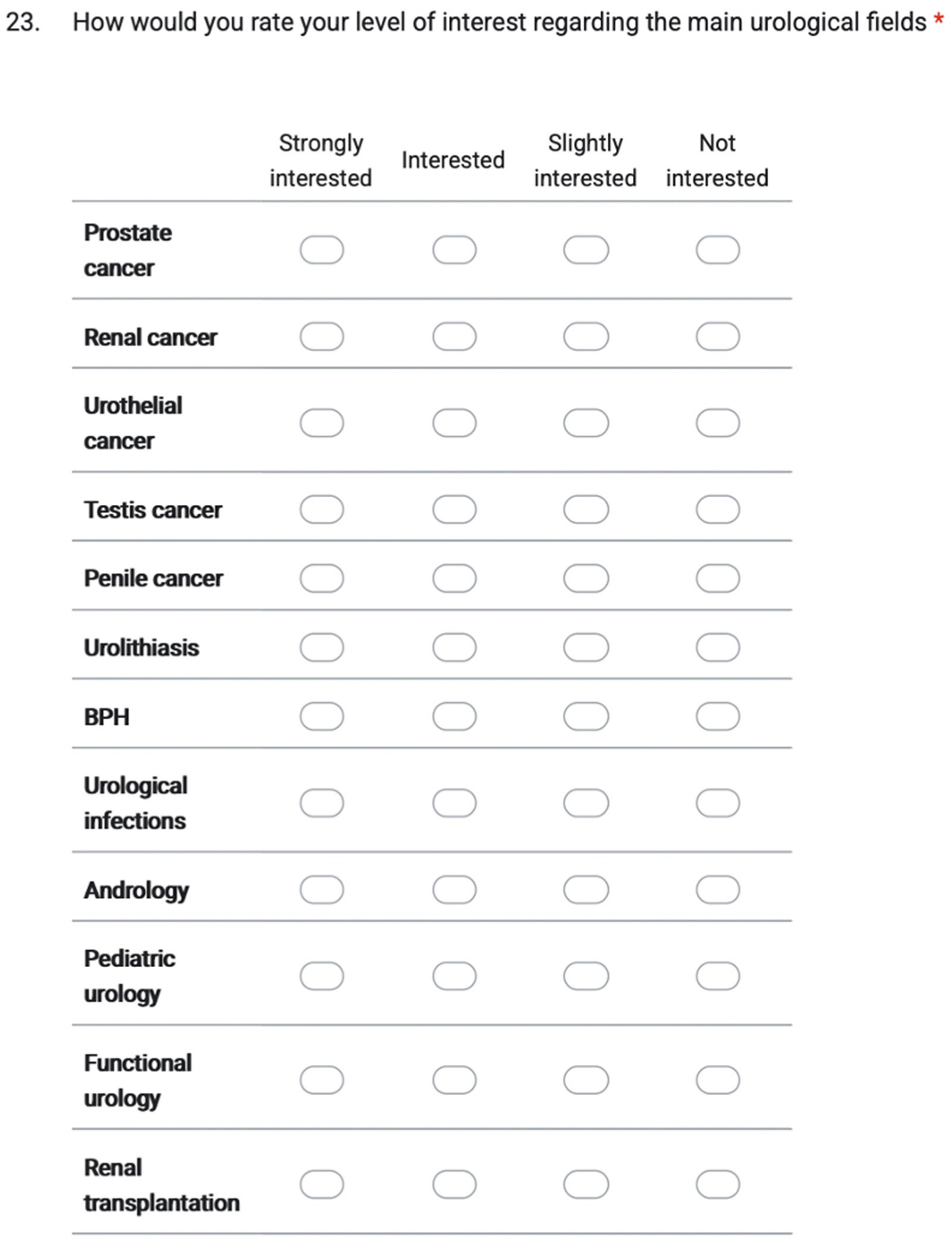

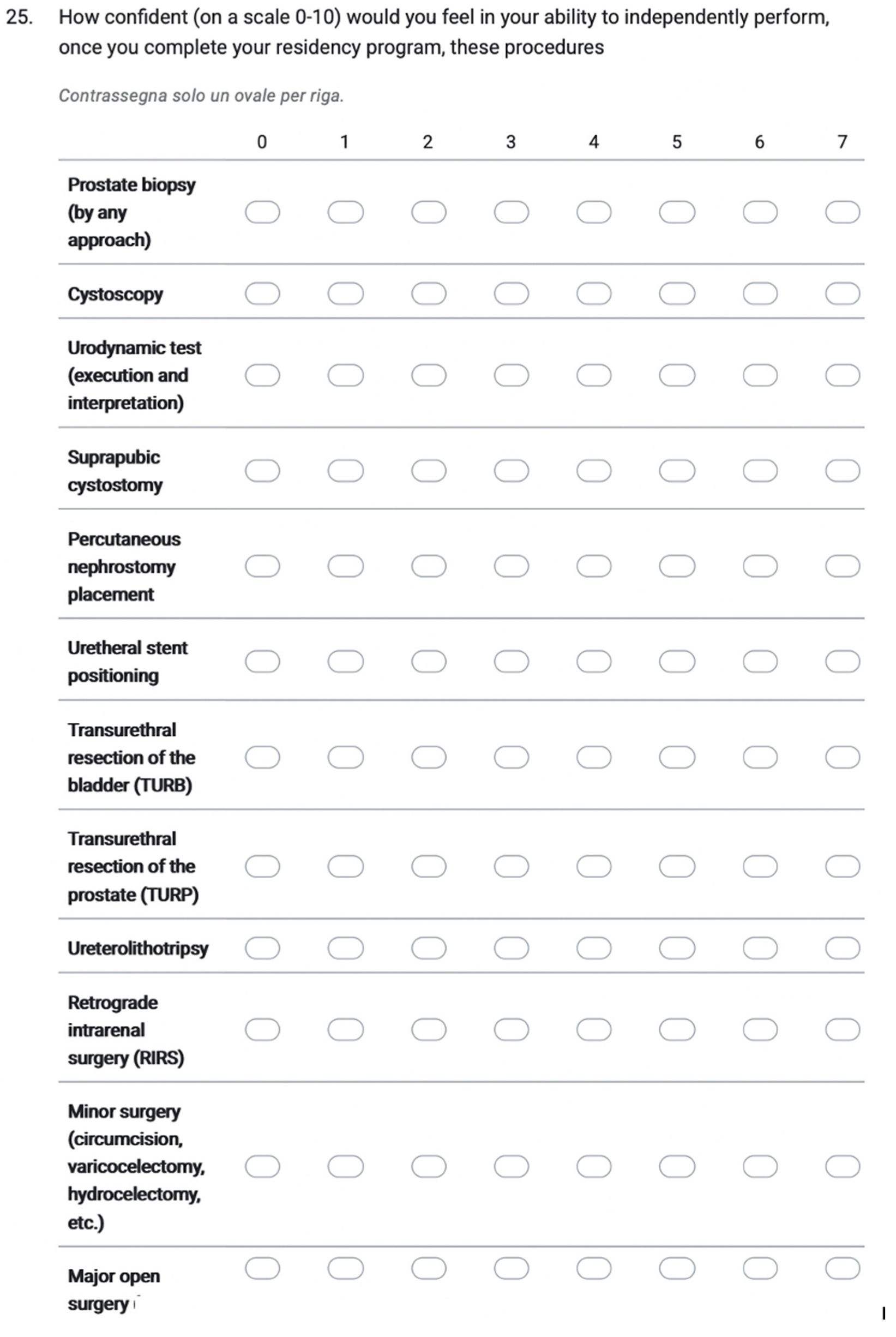

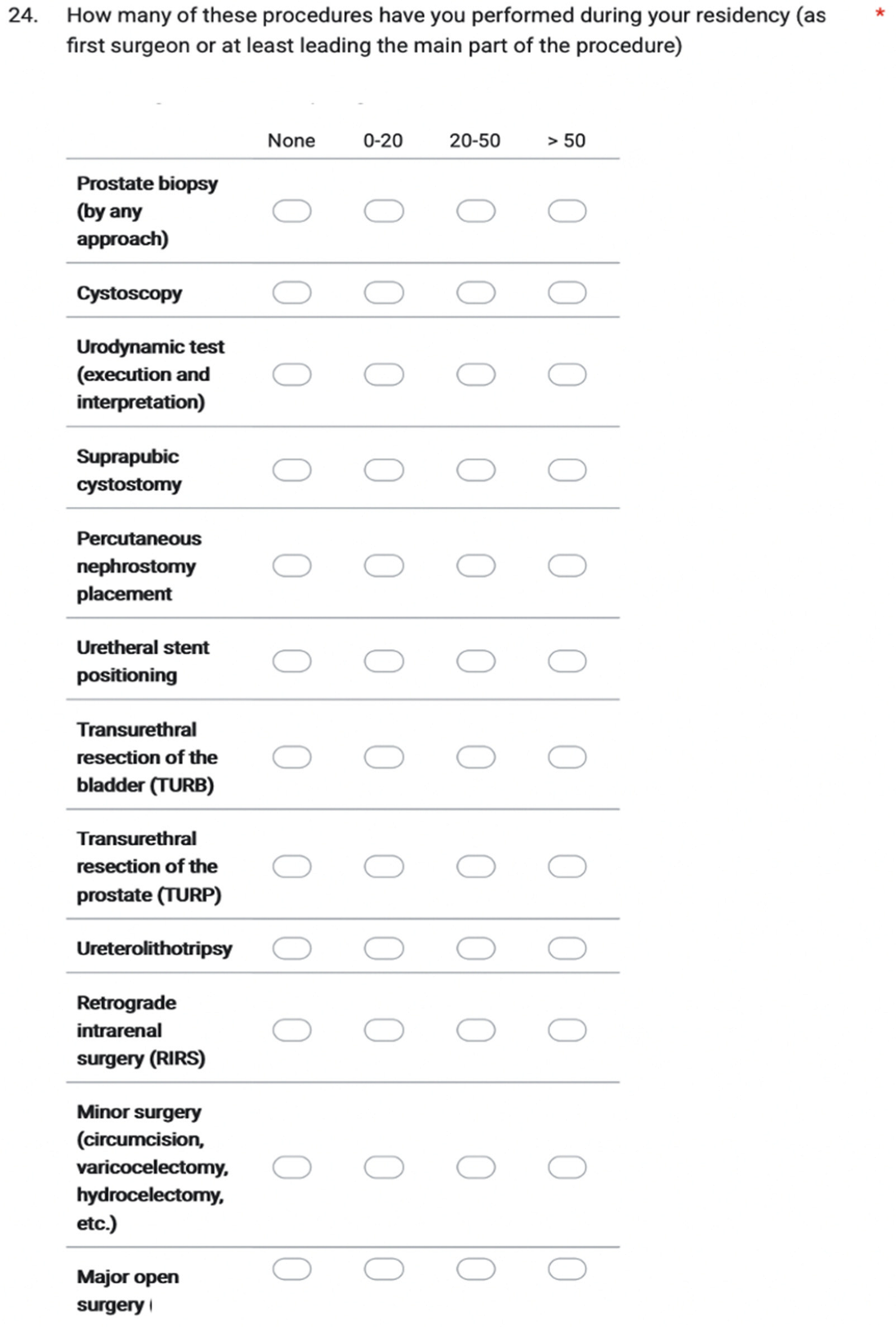

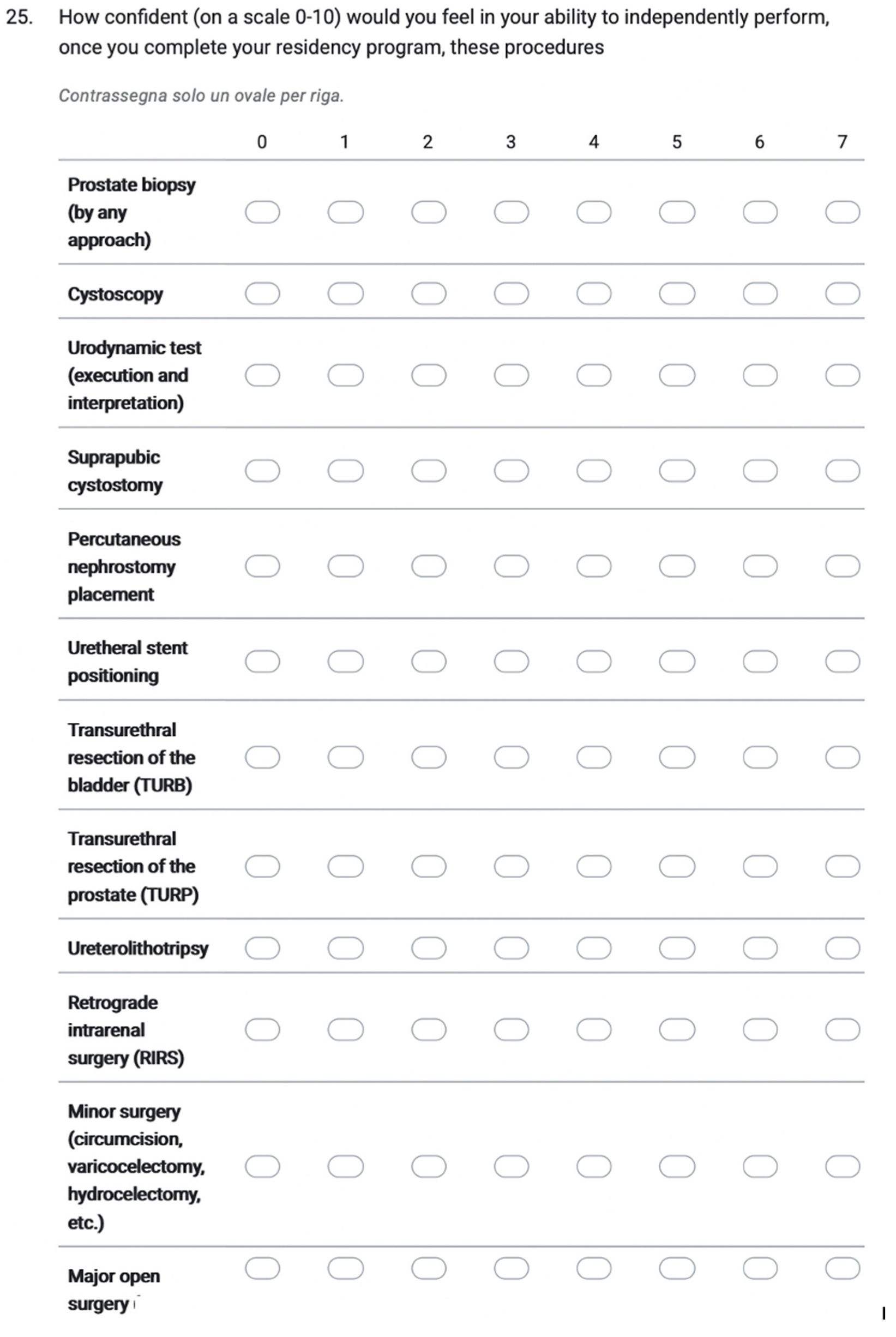

3.4. Surgical Experience

A dedicated section of the survey explored the surgical experience of residents, both in terms of the number of procedures performed (considering minor surgery, endoscopic, laparoscopic, and robotic interventions) and their expectation of autonomy in performing such interventions once they will complete their postgraduate training program.

Table 3 depicts data on surgical experience in endoscopic, laparoscopic and robotic surgery (both as first surgeon/at least leading the main part of the procedure and as assistant), as reported by the residents interviewed. As expected, significant differences in surgical exposure across residency years were observed, especially for endoscopic and laparoscopic procedures (both as first surgeon and assistant, all p < 0.01), whereas robotic surgery showed no significant differences across PGY levels (reflecting the uniformly limited exposure to console time across all training years). Post-hoc pairwise comparisons revealed that PGY1–2 residents consistently performed fewer endoscopic and laparoscopic procedures compared to PGY4–5 residents, with PGY3 trainees showing intermediate levels of exposure.

Operative exposure among trainees demonstrated substantial variability across urological procedures, revealing a clear stratification between high-volume interventions and more complex surgical domains. Cystoscopy represented the most consistently performed procedure, with 75.5% of residents reporting >50 cases, followed by prostate biopsy (42.3%). Transurethral Resection of Bladder Tumor (TURBT) and Transurethral Resection of the Prostate (TURP) showed intermediate exposure, with 22.1% and 15.4% of trainees, respectively, performing >50 procedures. In contrast, experience with advanced interventions remained markedly limited: nearly half of residents (47.1%) had never performed a percutaneous nephrostomy, while 57.2% and 56.7% reported no exposure as first operator to RIRS and major open surgery, respectively.

Expectations regarding procedural autonomy after completing the postgraduate training program mirrored these disparities. Residents anticipated the highest degree of independence for prostate biopsy and cystoscopy, and intermediate autonomy for TURBT and TURP. Conversely, procedures requiring more advanced technical proficiency (such as RIRS, percutaneous nephrostomy, and major open surgery) were associated with substantially lower expected autonomy (median 6, 5, and 2, respectively).

Complete data on surgical experience and expected autonomy in different urological procedure, as reported by the population interviewed, is depicted in

Table 4.

3.5. Clinical Workload and Educational Support

Structured theoretical teaching was inconsistently integrated across training programs. While the majority of residents (128/208, 61.5%) reported having scheduled theoretical lessons with professors or tutors, a substantial proportion (78/208, 37.5%) indicated that such sessions were not offered despite expressing interest in receiving them. Only a negligible minority (2/208, 1.0%) reported a lack of both formal lessons and interest in attending them.

Weekly clinical workload of trainees was assessed asking “How many hours per week do you usually work (scientific activity not considered)?”. Only a small proportion of residents reported working fewer than 30 or 30-40 hours/week (both 16/208, 7.7%), while a larger group reported a workload of 40–50 hours/week (52/208, 25%). Notably, the majority of residents (124/208, 59.6%) indicated working more than 50 hours per week, underscoring a substantial clinical burden across training programs.

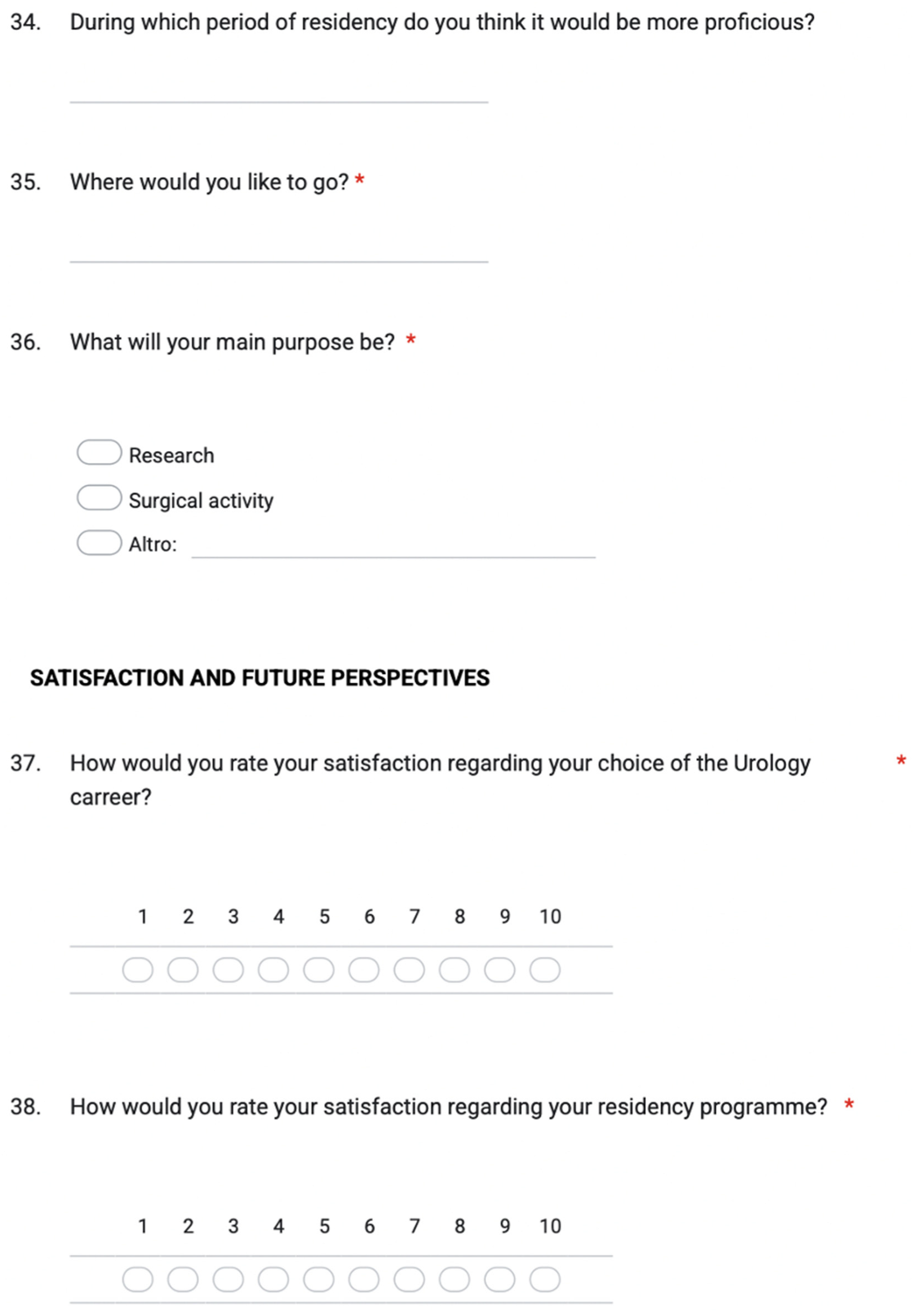

3.6. Fellowship and Surgical Rotation Between Departments

Overall, 120 (57.7%) residents reported that surgical rotation between departments is planned in their training school. Of the remaining, 65 (31.3%) answered they had not participated in training networks, but they would like to be exposed to a different environment for a period of time, while a smaller percentage (11%) reported not being interested in such experience.

When considering international fellowships, only 38 (18.3%) residents already experienced a period outside the main school of urology. Of these, 2 (5.3%), 3 (7.9%), 14 (36.8%), 11 (28.9%), 7 (18.4%), and 1 (2.6%) were PGY-1, -2, -3, -4, -5, and -6, respectively. Focusing on the main topic of their experience, in 14 (36.8%) cases the main purpose was research, 23 (60.5) were mostly interested in surgical activity, and 1 (2.6%) in purely clinical activity. Among those who had not been yet exposed to international fellowships, 90.6% (154/170) said they would be interested in such experience in the future, mostly (132/154, 85.7%) with the aim of improving surgical experience.

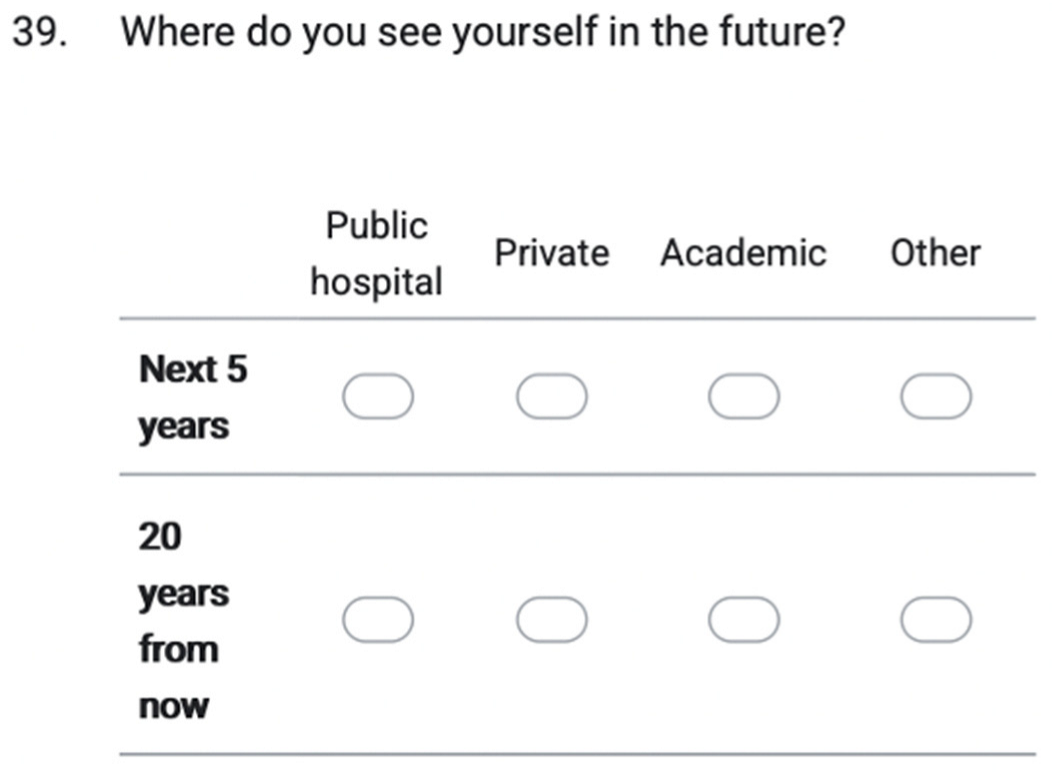

3.7. Overall Satisfaction and Future Perspectives

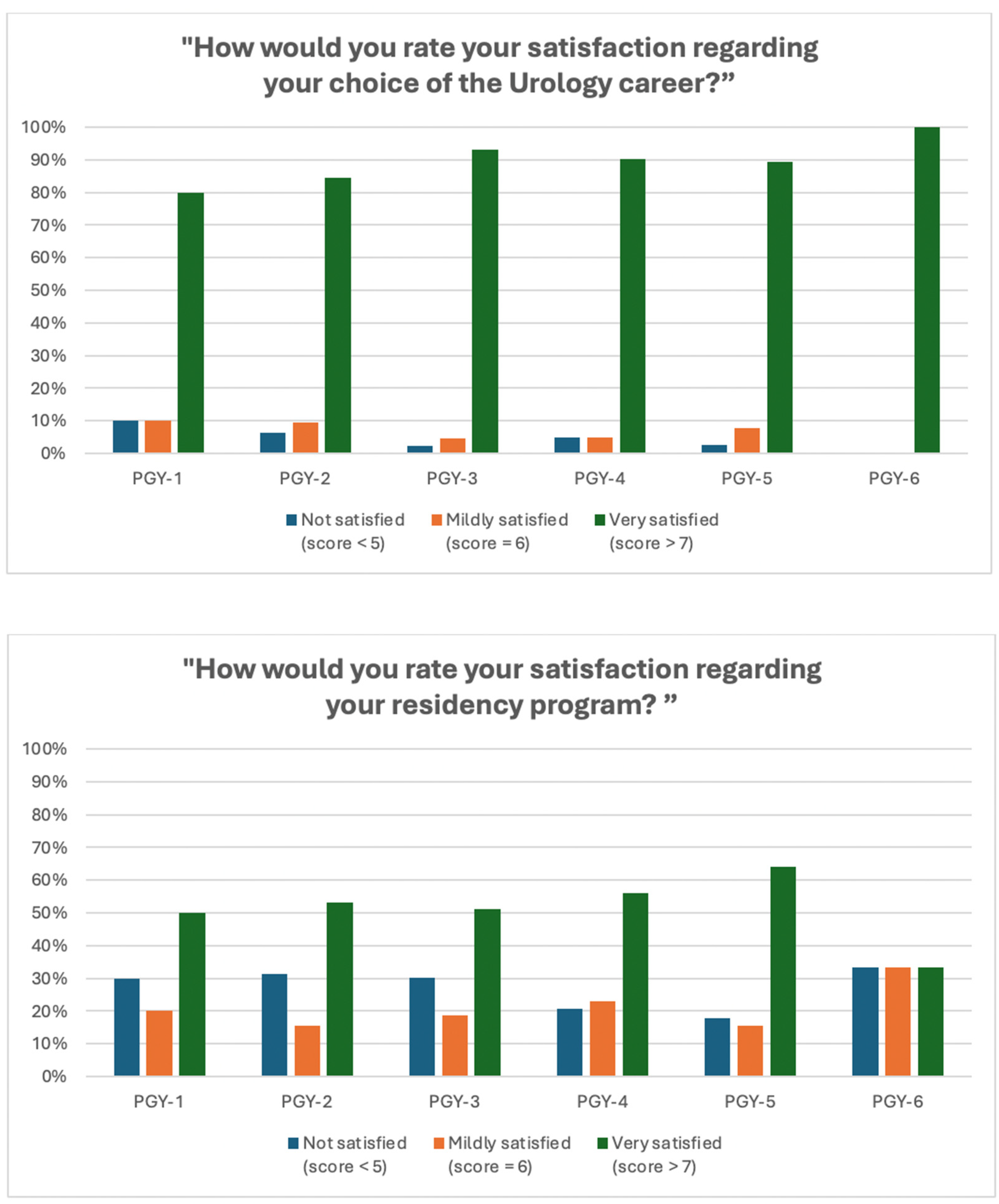

Satisfaction with the choice of urology as a specialty was consistently high across all training years, with no evidence of significant variation between PGY levels (p > 0.4). Overall, only a minority (respectively, 9/208 - 4.3%, and 13/208 – 6.3%) of residents reported being “not satisfied” (score 4-5 on a scale 0 to 10) or “mildly satisfied” (score = 6), whereas the vast majority (186/208, 89.4%) described themselves as “very satisfied” (score > 7). When specifically questioned about satisfaction rate regarding their residency program and Urology school, 116 (55.8%) still reported being pleased with their training urological course (score > 7), 41 (19.7%) were “mildly satisfied” (score = 6), and 51 (24.5%) were “unconvinced” (score 1-5) by their Urology school. Stratifying by PGY, the distribution of residents reporting low, mild, or high satisfaction did not vary significantly between PGY groups (p = 0.889).

Figure 2 depicts overall satisfaction level among residents (stratified by PGY).

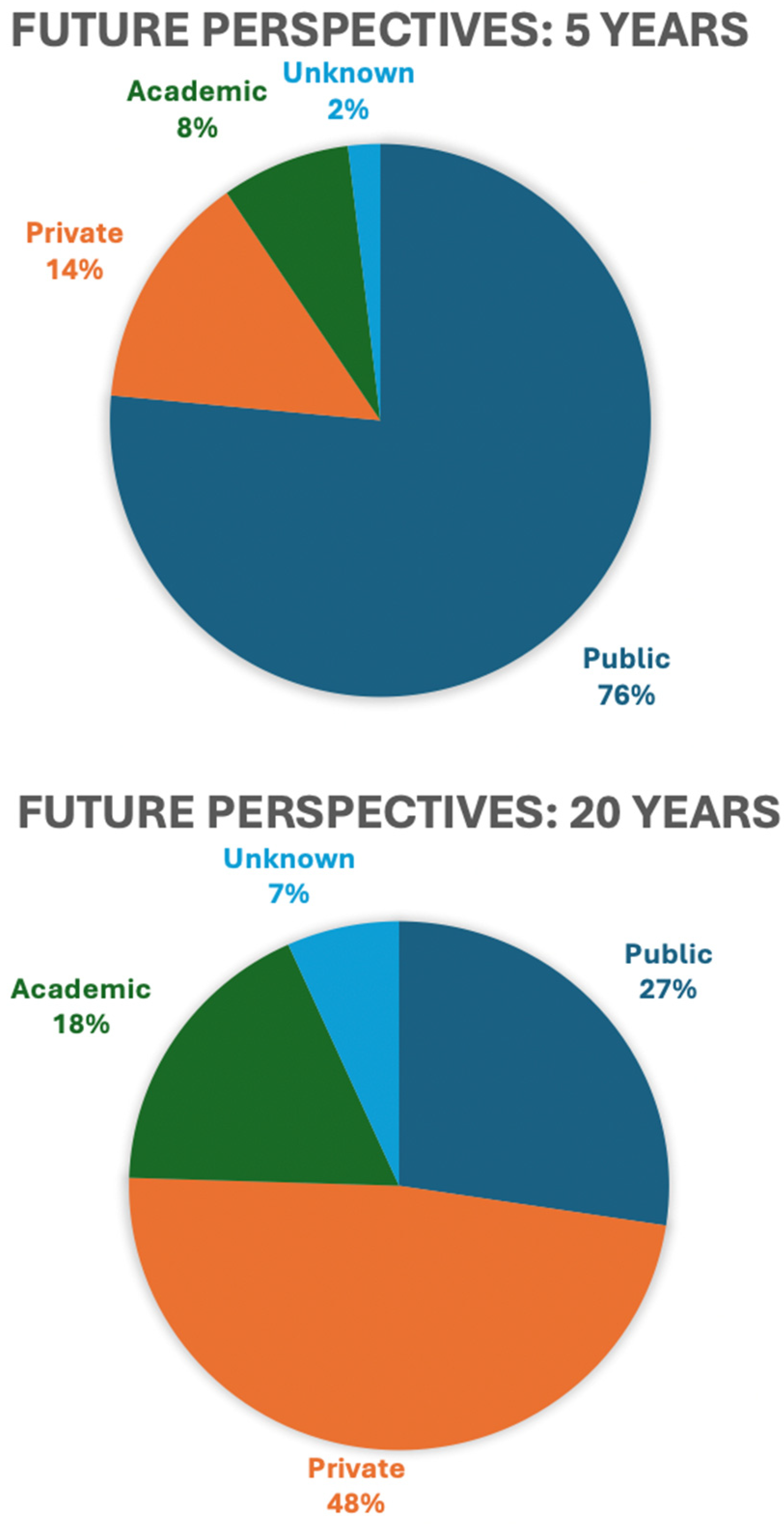

To explore residents’ professional trajectories and future perspectives, we assessed their preferred employment setting at 5- and 20-years post-training (public, private, or academic). In the short term, the majority anticipated working in a public hospital (159/208, 76.4%), whereas substantially fewer envisioned a career in the private sector (29/208, 13.9%) or within an academic institution (16/208, 7.7%). In contrast, 20-year projections revealed a substantial shift toward the private sector, which became the most frequently selected option (100/208, 48.1%), followed by public hospitals (57/208, 27.4%) and academic institutions (37/208, 17.8%), while 14 residents (6.7%) were uncertain about their long-term career setting.

Figure 3 visualizes the evolution of residents’ career expectations across 5- and 20-year horizons.

4. Discussion

This international survey involving urology residents from 32 different countries all across the world provides compelling insight into the current landscape of urology training and career aspirations. Previous surveys investigated these topics among urology trainees (7–9,12,13). However, most of these studies were limited to a single country or within European centers, while no previous studies, to the best of our knowledge, evaluated residents’ experiences and perspectives from so many different nations and continents. Several critical themes emerge from our data, some encouraging and others highlighting persistent gaps, that merit reflection and may inform future educational strategies.

First of all, despite a great increase in recent years, female representation in Urology remains quite low, highlighting a persistent gender gap also among residents. Considering the participants at the congress, and more specifically those who completed the survey, only about 30% were women. This data confirms previous findings from similar studies (8,9,12,14) and is consistent with the results provided by Halpern et al. (15). In their study, they report that although urology demonstrated the greatest increase over time in the proportion of women among all specialties, female representation still remains a minority among urology residents (less than 25%). This contrasts with other surgical specialties, historically considered "more feminine", such as gynecology, which reach peaks of up to 80% (15). Recent studies showed how women encounter significant barriers along their surgical training, including lack of support, lower surgical training, less opportunities to get leading roles and academic positions, impaired work-life balance and pay equity (16–20). All these factors negatively impact their academic and professional development, leading female students to less likely pursue surgical specialties (21). Being aware of this, efforts should be made focusing on equal education of future surgeons to improve disparities.

Second, when investigating residents’ involvement in research and scientific activity, most of them reported being actively engaged (76.4%) and already having played the role of speaker at urological congresses (64.4%). However, when questioned “How confident would you feel in independently writing a scientific manuscript?”, 67% of them reported a non-negligible insecurity.

As defined by Prof. Heidenreich, educational research should be “the motivated guidance of residents to be involved and to conduct structured research” (22). In his paper he reports that a structured research curriculum, based on participation to conferences, literature analysis, support from mentors, and scientific production, should be integrated into residency programs, not only with the goal to promote residents for an academic career, but to improve individual competence in urology. In fact, as reported by Lee et al. (23) and Yang et al. (24), residency programs should offer dedicated research time during training, as it proved being associated with significant increases in future career academic success.

We then investigated residents’ surgical experience, revealing significant differences in surgical exposure across residency years. Despite the great interest shown for robotic surgery, a very limited exposure to console time across all training years was reported. Similarly, while simple interventions (such as cystoscopy and prostate biopsy) are ubiquitous, with a majority of residents reporting high case volumes, access to more advanced surgical procedures (e.g., percutaneous nephrostomy, RIRS, major open surgery) remains limited for many, revealing pronounced inequality in procedural exposure across the urology curriculum. Corresponding to procedural exposure, residents' expected autonomy mirrors this discrepancy: highest for low-risk endoscopic tasks, markedly lower for complex surgeries.

In fact, urologic training has undergone significant change over time, due to different factors (rise of new minimally invasive/robotic procedures, increasing numbers of residents, changes in teaching philosophy, etc.) with resident-reported role as “surgeon” and their autonomy significantly decreasing (13,25–28). As surgical independence is a key milestone in competency-based education, structured curricula, eLearning, and hands-on simulation platforms should be considered to bridge these gaps. Various programs, such as the EuropeaN Training in uRologY (ENTRY) project (29), the European Urology Residents Education Programme (EUREP) (12,30), The European Association of Urology Robotic Training Curriculum (31–33), as well as other structured educational models (14,34–37) emerged in the last years, providing surgical training and education. In this context, Hanelin et al. (38) proposed to create “procedure-specific autonomy maps” to visually depict expected levels of independence for key steps of common urologic operations, providing a standardized framework for skill progression over the course of residency and promoting a more structured and equitable model of surgical education in urology. Although there is still no certainty as to which strategy will give the best results, increased focus and awareness on resident education and surgical autonomy is vital for training the next generation of surgeons.

Resident workload is substantial: nearly 60% of respondents report working over 50 hours per week, although specialization contracts generally set a maximum limit of working hours per week (e.g. 38 h/week in Italy and up to 48 h/week for other EU and non-EU countries), in accordance with the European Working Time Directive (Directive 2003/88/EC) (39). Despite this intensity, structured educational support remains uneven: although more than 60% of residents have formal theoretical sessions with tutors, more than one-third lack such teaching. This data suggests that educational curricula may not be fully aligned with trainee needs, particularly in systems where resource constraints or clinical demands limit protected teaching time.

As reported by previous studies (20,40–42), excessive workload, causing an imbalanced work-life equilibrium (prolonged work hours, frequent transitions from day to night shifts, irregular patterns of eating, sleeping, and exercise), as well as unsatisfactory working conditions are among the main causes of burnout in doctors and trainees. Professional burnout, beyond having an impact on the lives of workers themselves (higher rates of depression, physicians switching careers or leaving the medical profession), it also has repercussions on patient care, increasing medical errors (43). Prevalence of burnout presents high variability amongst the various countries and residents’ groups, up to almost 70% in some studies, probably due to the different organization of training programs and health systems, workloads, availability of mental health services and psychological support, (40,41). As reported by Degraeve et al. (44), “when residents work less, they feel better”. In this regard, interventions providing basic needs and encouraging healthy lifestyle habits (facilitating physical wellness and social engagement among residents) might result in sustained reductions in burnout (45). Moreover, structured mentorship programs, coaching interventions, as well as mental health and psychological support showed promising results in reducing burnout symptoms (45–47).

Despite these problems, overall satisfaction with the choice of urology as specialty remains high: nearly 90% of respondents are “very satisfied” with their choice, suggesting that urology remains an attractive and fulfilling specialty for trainees globally. When looking at projected career trajectories, the majority of residents foresee early employment in the public sector. However, 20-year projections reveal a pronounced shift toward the private sector. This trend may reflect broader socio-economic dynamics, perceived financial incentives, or limited academic career pipelines. Strategic planning by academic institutions and national societies may be needed to sustain interest in academic careers, especially as many residents envision private practice as their long-term setting.

The strengths and limitations of our survey should be interpreted considering established guidelines for the design and reporting of web-based questionnaires. The CHERRIES framework (11) emphasizes the importance of transparency, prevention of sampling bias, and completeness of reporting. Many prior surveys on urology training have been hindered by low response rates or non-representative samples, underscoring the importance of rigorous methodology to ensure reliability and reproducibility. Moreover, our survey was not limited by single-country data, but we tried to summarize global perceptions, including a large, multi-national sample of trainees from 32 different countries.

However, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, survey data are subject to selection bias, as residents who attended the SIU congress and completed the questionnaire may be more academically or professionally motivated than their peers. Moreover, our results only reflect responders’ judgements and perceptions, rather than being an objective assessment. Second, our cross-sectional design captures perceptions at a single timepoint and may not reflect evolving attitudes over time. Third, although this great heterogeneity in the population interviewed represents the main strength of our study, as training environments vary greatly across regions (different infrastructural resources, case volumes, faculty supervision, training programs, national health systems, etc.), our findings may not be generalizable to all urology residency programs.

5. Conclusions

This multi-national survey highlights that urology residents across the globe are deeply engaged in research, largely satisfied with their career choice, and highly motivated toward future mobility. However, significant inequities in procedural exposure and confidence in scientific production, as well as the persistence of a gender gap and excessive workload, suggest opportunities for curriculum development, structured mentorship programs, and changes in training organization. Addressing these areas through thoughtful, competency-based initiatives could strengthen the training pipeline and ensure that all residents achieve their full potential.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A. and R.N.; methodology, A.L.H., J.P.S. and P.S.; validation and review of the quality of the survey, M.G., F.C. and S.S.; formal analysis, R.C., L.T. and A.U.; resources, G.M., D.D., A.A.M. and N.P.; writing—original draft, A.A. and R.N.; data curation, G.C., O.F., I.F., W.F.M., H.G. and C.K.; writing—review and editing, S.G., H.H.W., P.E.S., J.M.Z,.; supervision, M.P.L., J.dlR. and M.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

This was a spontaneous survey, as so no formal informed consent is required.

Data Availability Statement

The data reported in this paper are available from the corresponding author upon request. Data is not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

All participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Supplementary Figure 1. List of question of the online survey

Appendix A.2. Supplementary Figure 2. Countries represented by participants at the SIU congress

References

- Hanelin DG, Tripp J, Sankin A, Abraham, N. Urology Autonomy Maps: Evaluation of Attending Surgeon Expectations for Resident Competencies in Common Urology Procedures. Urology. 2025 Sep;

- Yong, C. Educating the Educator: Understanding Essential Components of Contemporary Urology Residency Training. Curr Urol Rep. 2025 Dec 26;26(1):33. [CrossRef]

- Cruz AP, Skolarus TA, Ambani SN, Hafez K, Kraft KH. Aligning Urology Residency Training With Real-World Workforce Needs. J Surg Educ. 2021 May;78(3):820–7. [CrossRef]

- Carrion DM, Rodriguez-Socarrás ME, Mantica G, Esperto F, Cebulla A, Duijvesz, D., et al. Current status of urology surgical training in Europe: an ESRU–ESU–ESUT collaborative study. World J Urol. 2020 Jan 13;38(1):239–46. [CrossRef]

- Buffi N, Paciotti M, Gallagher AG, Diana P, De Groote R, Lughezzani, G., et al. European training in urology ( ENTRY ): quality-assured training for European urology residents. BJU Int. 2023 Feb 21;131(2):177–8. [CrossRef]

- Borgmann H, Arnold HK, Meyer CP, Bründl J, König J, Nestler T, et al. Training, Research, and Working Conditions for Urology Residents in Germany: A Contemporary Survey. Eur Urol Focus. 2018 May;4(3):455–60.

- Tzelves L, Glykas I, Lazarou L, Zabaftis C, Fragkoulis C, Leventi, A., et al. Urology residency training in Greece. Results from the first national resident survey. Actas Urológicas Españolas (English Edition). 2021 Oct;45(8):537–44. [CrossRef]

- Cocci A, Patruno G, Gandaglia G, Rizzo M, Esperto F, Parnanzini, D., et al. Urology Residency Training in Italy: Results of the First National Survey. Eur Urol Focus. 2018 Mar;4(2):280–7.

- NAPOLITANO L, MAGGI M, SAMPOGNA G, BIANCO M, CAMPETELLA M, CARILLI M., et al. A survey on preferences, attitudes, and perspectives of Italian urology trainees: implications of the novel national residency matching program. Minerva Urology and Nephrology. 2023 Dec;75(6). [CrossRef]

- Kate, V., Kalayarasan, R. Advancing Surgical Education Globally: Training NextGen Surgeons. International Journal of Advanced Medical and Health Research. 2024 Jan;11(1):1–3. [CrossRef]

- Eysenbach, G. Improving the Quality of Web Surveys: The Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES). J Med Internet Res. 2004 Sep 29;6(3):e34.

- Carrion DM, Rodriguez-Socarrás ME, Mantica G, Esperto F, Cebulla, A., Duijvesz, D., et al. Current status of urology surgical training in Europe: an ESRU–ESU–ESUT collaborative study. World J Urol. 2020 Jan 13;38(1):239–46. [CrossRef]

- Borgmann H, Arnold HK, Meyer CP, Bründl J, König J, Nestler T, et al. Training, Research, and Working Conditions for Urology Residents in Germany: A Contemporary Survey. Eur Urol Focus. 2018 May;4(3):455–60. [CrossRef]

- Somani B, Gomez-Rivas J, Oliveira TR de, Veneziano D, Brouwers T, Herrmann, C., et al. Trends of European School of Urology (ESU) training and resident education: an overview of 2 decades of EAU education programme. World J Urol. 2024 Oct 7;42(1):564. [CrossRef]

- Halpern JA, Lee UJ, Wolff EM, Mittal S, Shoag JE, Lightner DJ, et al. Women in Urology Residency, 1978-2013: A Critical Look at Gender Representation in Our Specialty. Urology. 2016 Jun;92:20–5. [CrossRef]

- Stephens EH, Heisler CA, Temkin SM, Miller, P. The Current Status of Women in Surgery. JAMA Surg. 2020 Sep 1;155(9):876.

- Yang G, Villalta JD, Weiss DA, Carroll PR, Breyer BN. Gender Differences in Academic Productivity and Academic Career Choice Among Urology Residents. Journal of Urology. 2012 Oct;188(4):1286–90. [CrossRef]

- Olivencia MN, Lam NB, Stewart S, Miller-Hammond K, Johnson, S., Nembhard CE, et al. Disparities in Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in Surgical Residency Education: A Systematic Review. Am Surg. 2025 Sep 7;91(9):1405–18.

- Marchetti KA, Ferreri CA, Bethel EC, Lesser-Lee B, Daignault-Newton S, Merrill, S., et al. Gender-based Disparity Exists in the Surgical Experience of Female and Male Urology Residents. Urology. 2024 Mar;185:17–23. [CrossRef]

- Minore A, Cacciatore L, Cindolo L, Gravas S, de la Rosette, J., Laguna MP, et al. Work–Life Integration, Professional Stress, and Gender Disparities in the Urological Workforce: Findings from a Worldwide Cross-Sectional Study. Société Internationale d’Urologie Journal. 2025 Dec 18;6(6):74. [CrossRef]

- Bennett CL, Baker O, Rangel EL, Marsh RH. The Gender Gap in Surgical Residencies. JAMA Surg. 2020 Sep 1;155(9):893.

- Heidenreich, A. Lehrforschung in der Urologie. Urologe. 2019 Feb 24;58(2):114–25. [CrossRef]

- Lee A, Namiri N, Rios N, Enriquez A, Hampson LA, Pruthi RS, et al. Dedicated Residency Research Time and Its Relationship to Urologic Career Academic Success. Urology. 2021 Feb;148:64–9. [CrossRef]

- Yang G, Zaid UB, Erickson BA, Blaschko SD, Carroll PR, Breyer BN. Urology Resident Publication Output and Its Relationship to Future Academic Achievement. Journal of Urology. 2011 Feb;185(2):642–6. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen AT, Oliver JB, Jain K, Hingu J, Kunac A, Sadeghi-Nejad, H., et al. Urology Resident Autonomy in the Veterans Affairs Healthcare System. J Surg Educ. 2025 Feb;82(2):103370.

- Neuzil K, Wallen E, Potts III JR, DeWitt-Foy ME. See more, do less?—resident-reported training trends in reconstructive urology. Transl Androl Urol. 2025 Aug;14(8):2358–64.

- Nguyen AT, Anjaria DJ, Sadeghi-Nejad, H. Advancing Urology Resident Surgical Autonomy. Curr Urol Rep. 2023 Jun 14;24(6):253–60.

- Rodríguez-Socarrás ME, Gómez Rivas J, García-Sanz M, Pesquera L, Tortolero-Blanco L, Ciappara, M., et al. Actividad médico-quirúrgica y estado actual de la formación de los residentes de urología en España: Resultados de una encuesta nacional. Actas Urol Esp. 2017 Jul;41(6):391–9.

- Buffi N, Paciotti M, Gallagher AG, Diana P, De Groote R, Lughezzani, G., et al. European training in urology ( ENTRY ): quality-assured training for European urology residents. BJU Int. 2023 Feb 21;131(2):177–8. [CrossRef]

- Somani BK, Van Cleynenbreugel B, Gozen A, Palou J, Barmoshe, S., Biyani, S., et al. The European Urology Residents Education Programme Hands-on Training Format: 4 Years of Hands-on Training Improvements from the European School of Urology. Eur Urol Focus. 2019 Nov;5(6):1152–6.

- Volpe A, Ahmed K, Dasgupta P, Ficarra V, Novara G, van der Poel, H., et al. Pilot Validation Study of the European Association of Urology Robotic Training Curriculum. Eur Urol. 2015 Aug;68(2):292–9.

- Ahmed K, Khan R, Mottrie A, Lovegrove C, Abaza R, Ahlawat R, et al. Development of a standardised training curriculum for robotic surgery: a consensus statement from an international multidisciplinary group of experts. BJU Int. 2015 Jul 23;116(1):93–101. [CrossRef]

- Mottrie A, Novara G, van der Poel H, Dasgupta P, Montorsi, F., Gandaglia, G. The European Association of Urology Robotic Training Curriculum: An Update. Eur Urol Focus. 2016 Apr;2(1):105–8.

- Chow AK, Sherer BA, Yura E, Kielb S, Kocjancic, E., Eggener, S., et al. Urology Residents’ Experience and Attitude Toward Surgical Simulation: Presenting our 4-Year Experience With a Multi-institutional, Multi-modality Simulation Model. Urology. 2017 Nov;109:32–7. [CrossRef]

- Fukuta K, Fukawa T, Kobayashi S, Shiozaki K, Sasaki, Y., Seto, K., et al. Efficacy of educational stepwise robot-assisted radical prostatectomy procedure for urology residents. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2024 Jul 3;17(3).

- Pinto LOAD, Silva RC, Santos Junior HCF dos, Bentes LG de B, Otake MIT, Bacelar HPH de, et al. Simulators in urology resident’s training in retrograde intrarenal surgery. Acta Cir Bras. 2024;39. [CrossRef]

- Bouvette MJ, Lee, B., Bradley, N. Robotic simulation in urology training: implementation, curricula, and barriers across U.S. residency programs. J Robot Surg. 2025 Jul 20;19(1):406.

- Hanelin DG, Tripp J, Sankin A, Abraham, N. Urology Autonomy Maps: Evaluation of Attending Surgeon Expectations for Resident Competencies in Common Urology Procedures. Urology. 2025 Sep; [CrossRef]

- European Doctors Working Conditions - A FEMS White Book. https://www.fems.net/images/Fems_documents/Documents/2024/FEMS__Digital_1.pdf.

- Marchalik, D., C.; Goldman, C., F.L.; Carvalho, F., Talso, M., H.; Lynch, J., Esperto, F., et al. Resident burnout in USA and European urology residents: an international concern. BJU Int. 2019 Aug 8;124(2):349–56. [CrossRef]

- Hanna KF, Koo, K. Professional Burnout and Career Choice Regret in Urology Residents. Curr Urol Rep. 2024 Dec 17;25(12):325–30.

- Koo K, Javier-DesLoges JF, Fang, R., North AC, Cone EB. Professional Burnout, Career Choice Regret, and Unmet Needs for Well-Being Among Urology Residents. Urology. 2021 Nov;157:57–63. [CrossRef]

- Tawfik DS, Profit J, Morgenthaler TI, Satele, D. V., Sinsky CA, Dyrbye LN, et al. Physician Burnout, Well-being, and Work Unit Safety Grades in Relationship to Reported Medical Errors. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018 Nov;93(11):1571–80. [CrossRef]

- Degraeve A, Lejeune S, Muilwijk T, Poelaert F, Piraprez, M., Svistakov, I., et al. When residents work less, they feel better: Lessons learned from an unprecedent context of lockdown. Progrès en Urologie. 2020 Dec;30(16):1060–6. [CrossRef]

- Anaissie J, Popat S, Mayer WA, Taylor JM. Innovative Approaches to Battling Resident Burnout in a Urology Residency Program. Urol Pract. 2021 May;8(3):387–92. [CrossRef]

- Glick H, Ganesh Kumar N, Olinger TA, Vercler CJ, Kraft KH. Resident Mental Health and Burnout: Current Practices and Perspectives of Urology Program Directors. Urology. 2022 Feb;160:40–5. [CrossRef]

- Fainstad T, Mann A, Suresh K, Shah P, Dieujuste N, Thurmon, K., et al. Effect of a Novel Online Group-Coaching Program to Reduce Burnout in Female Resident Physicians. JAMA Netw Open. 2022 May 6;5(5):e2210752. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).