1. Introduction

Deep learning models have become foundational components in systems that process temporal and sequential data, enabling applications ranging from wearable health monitoring and autonomous navigation to algorithmic trading and industrial process control. The discovery that neural networks are vulnerable to adversarial examples—carefully crafted perturbations that are imperceptible to humans yet cause systematic misclassification—has raised fundamental security concerns for these deployed systems [

1,

2]. While adversarial robustness has been extensively characterized for image classifiers, temporal systems present

distinct rather than necessarily greater vulnerabilities. Empirical findings in human activity recognition (HAR) demonstrate severe accuracy degradation—from 95.1% to merely 3.4% under FGSM attacks for DNN classifiers, and from 93.1% to 16.8% for CNN-based models [

3]. However, these dramatic drops must be interpreted within their modality-specific context: unlike image perturbations constrained primarily by pixel-level imperceptibility, time series attacks face fundamentally different constraints including signal continuity, sensor measurement bounds, and inter-sensor correlations that can either amplify or attenuate vulnerability depending on the deployment scenario.

The adversarial robustness of image classifiers has received extensive research attention, yielding well-established attack methodologies, defense mechanisms, and evaluation benchmarks. However, adversarial attacks targeting time series and reinforcement learning (RL) systems present

qualitatively distinct challenges that remain inadequately addressed. Crucially, the vulnerability landscape differs fundamentally across temporal system modalities.

On-body sensor systems (accelerometers, gyroscopes, magnetometers) require perturbations that respect physical measurement constraints and maintain inter-sensor correlations inherent to rigid-body motion dynamics.

Device-free RF sensing systems (WiFi CSI, mmWave radar) face non-differentiable signal processing pipelines and propagation-path constraints that fundamentally alter the attack surface [

4]. These modality-specific characteristics necessitate tailored attack and defense strategies rather than direct adaptation of image-domain techniques.

Time series data exhibits temporal dependencies, variable sequence lengths, and domain-specific physical constraints that are absent in static image data. Unlike images where perturbations are constrained primarily by perceptual imperceptibility, time series attacks must additionally respect signal continuity requirements, sensor measurement bounds, inter-sensor correlations, and energy constraints inherent to battery-powered wearable devices—constraints that vary significantly across sensor modalities and deployment contexts. Reinforcement learning systems face sequential decision-making vulnerabilities where adversarial perturbations can compound across time steps, potentially leading to catastrophic failures in safety-critical applications.

The practical implications of these vulnerabilities extend across multiple critical domains. In healthcare monitoring, recent work has demonstrated that adversarial perturbations can manipulate fall detection systems, potentially causing life-threatening delays in emergency response for elderly patients [

5]. Smart home gesture recognition systems based on radar sensing have been shown vulnerable to attacks that perturb only the padding regions of input sequences without modifying actual gesture frames [

6]. Financial trading systems face manipulation through ephemeral perturbations that induce suboptimal buy/sell decisions while remaining statistically undetectable [

7].

1.1. Motivation and Scope

The increasing deployment of deep learning in safety-critical temporal applications motivates urgent investigation of adversarial vulnerabilities. We examine several representative scenarios that illustrate the breadth and severity of potential attacks.

In healthcare monitoring, wearable devices continuously classify user activities for fall detection, cardiac arrhythmia identification, and medication adherence. An adversary who can subtly perturb sensor readings may cause dangerous misclassifications, potentially delaying emergency responses. The ADAR framework demonstrated that adversarial attacks exhibit four distinct transferability dimensions in wearable HAR systems: between different ML models, across different users, across sensor body locations, and across different datasets [

3]. This multi-dimensional transferability implies that an adversary need not have knowledge of the specific deployment configuration to craft effective attacks.

In autonomous systems, vehicles rely on temporal sensor fusion across cameras, LiDAR, radar, and inertial measurement units for perception and planning. Adversarial perturbations targeting these temporal streams can cause navigation failures with life-threatening consequences. Recent work on millimeter-wave radar sensing has shown that physically realizable attacks using low-cost meta-material tags can achieve 97% accuracy in manipulating range estimation, 96% for angle estimation, and 91% for speed estimation—at costs 10-100× lower than existing attack methods [

8].

In financial systems, algorithmic trading increasingly depends on time series forecasting models processing market data, news feeds, and transaction records. Adversarial attacks on these systems can exploit the temporal structure of financial data through targeted perturbations that manipulate predictions in specific directions (bullish or bearish), at particular amplitudes, or during critical time windows [

9].

Beyond traditional deep learning architectures, the emergence of large language models (LLMs) for time series analysis introduces novel vulnerability dimensions. Recent work has demonstrated that LLM-based time series forecasters—including TimeGPT, GPT-4, LLaMA, and Mistral variants—exhibit distinct adversarial susceptibilities compared to conventional neural architectures [

10,

11]. Xiao et al. [

12] demonstrated learning-based attacks specifically targeting temporal forecasting models through directional, amplitudinal, and temporal perturbation strategies. These findings suggest that the rapid adoption of foundation models for temporal applications may be outpacing security analysis, creating an urgent need for comprehensive adversarial assessment.

This survey addresses three interconnected domains with particular emphasis on sensor-specific vulnerabilities:

Time series adversarial attacks: We comprehensively examine HAR systems with detailed analysis of attacks targeting individual sensor modalities (accelerometer, gyroscope, magnetometer) and their combinations, WiFi channel state information (CSI) and radar-based sensing systems, skeleton-based action recognition, and medical/financial time series applications.

Reinforcement learning attacks: We analyze state observation perturbations, reward poisoning mechanisms, adversarial policy training, and the emerging paradigm of using RL algorithms for generating attacks on deep neural networks.

Cross-cutting themes: We identify critical patterns spanning explainability-guided attack generation, multi-sensor fusion vulnerabilities, physical realizability constraints, and certified defense mechanisms.

1.2. Gaps in Existing Surveys

Despite substantial growth in adversarial machine learning research, existing surveys exhibit significant coverage gaps for temporal and sequential systems.

Table 1 presents a systematic comparison with representative surveys published between 2019 and 2025, revealing several critical limitations.

First, there is an absence of dedicated time series coverage. Foundational work by Fawaz et al. [

13] investigated attacks on time series classification but did not provide comprehensive survey coverage. Subsequent surveys have focused predominantly on computer vision [

14,

15,

16,

17], natural language processing [

18,

19], or domain-agnostic adversarial machine learning [

20,

21]. None of these surveys address the unique characteristics of sensor-based time series data, including the constraints imposed by physical measurement processes, the multi-modal nature of wearable sensor systems, or the temporal dependencies inherent in sequential activity data. Furthermore, emerging threats targeting time series anomaly detection systems [

22] and autoregressive forecasting models [

23] remain unexamined within a unified adversarial framework.

Second, existing HAR and sensor system security analyses are limited. Prior HAR surveys [

24,

25] emphasize recognition methodologies rather than adversarial robustness. Sensor system surveys address signal processing techniques without systematic treatment of adversarial threats. The notable exception is Sakka et al. [

5], who examined security issues in HAR systems but focused primarily on medical IoT applications without comprehensive analysis of attack methodologies, threat models, or defense mechanisms across the broader HAR landscape.

Third, no existing survey provides a unified temporal and RL perspective. Despite the shared sequential nature of time series and RL systems—and their increasing co-deployment in real-world applications such as autonomous vehicles and robotic systems—no existing survey bridges these domains within a coherent analytical framework. Recent RL security surveys [

26,

27,

28] focus exclusively on RL agent vulnerabilities without considering the application of RL techniques for attack generation against non-RL systems.

Fourth, the critical dimension of sensor-specific vulnerabilities remains unaddressed. Existing work has demonstrated that different sensor modalities (accelerometer vs. gyroscope vs. magnetometer) exhibit dramatically different vulnerability profiles, with cross-sensor transferability ranging from 0% to over 80% depending on body placement and sensor type [

3,

29]. No existing survey systematically analyzes these sensor-specific characteristics or their implications for attack and defense design.

Fifth, novel architectural paradigms present uncharacterized vulnerabilities. Spiking neural networks (SNNs) for time series classification—increasingly deployed for energy-efficient edge inference—exhibit adversarial susceptibility patterns distinct from conventional architectures [

30]. Similarly, attention-based forecasting models face query-specific vulnerabilities through black-box attack strategies [

31]. No existing survey systematically addresses these architectural diversity considerations within the temporal domain.

1.3. Contributions

This survey makes the following contributions:

First unified temporal attack survey with sensor-specific and modality-aware analysis. We provide an integrated treatment of adversarial attacks on time series and reinforcement learning systems, establishing detailed taxonomies spanning HAR with emphasis on individual sensor modalities (accelerometer, gyroscope, magnetometer, IMU fusion), WiFi CSI and radar-based sensing, skeleton-based action recognition, and RL agent policies. Our analysis uniquely examines how attack effectiveness varies across sensor types, body placements, fusion strategies, and—critically—distinguishes between on-body and device-free sensing paradigms that present fundamentally different attack surfaces.

Systematic literature analysis. We systematically review over 120 papers published between 2019 and 2025, comprising time series attack papers across multiple application domains, RL attack papers spanning state perturbation to reward poisoning, and papers addressing cross-cutting themes including physical realizability and certified defenses.

Comprehensive comparison framework with quantitative analysis. We present detailed comparison tables cataloging attack methods with standardized metadata including datasets, threat models, attack success rates, perturbation constraints, key contributions, and identified limitations. We provide quantitative analysis of attack effectiveness across different sensor configurations and threat model assumptions.

Critical analysis of methodological limitations. Beyond cataloging existing work, we provide critical analysis of methodological limitations in current research, including the prevalence of unrealistic threat models, the gap between digital and physical attack validation, and the lack of standardized evaluation protocols for temporal adversarial attacks.

Coverage of emerging architectural vulnerabilities. We extend analysis beyond conventional CNN/LSTM architectures to address adversarial susceptibilities in transformer-based temporal models, spiking neural networks for edge deployment, and LLM-based time series forecasters—architectural paradigms that are rapidly being adopted but whose security properties remain undercharacterized.

Research roadmap. We articulate eight critical research gaps at the intersections of explainability, sensor targeting, temporal optimization, and RL-based attack generation, providing concrete directions for future investigation.

1.4. Survey Methodology

This survey follows systematic review guidelines adapted for computer science literature [

32], incorporating elements of PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) methodology where applicable to empirical adversarial machine learning research.

1.4.1. Search Strategy and Databases

We conducted a systematic literature search across IEEE Xplore, ACM Digital Library, Springer, Elsevier ScienceDirect, and arXiv using query terms including “adversarial attack,” “time series,” “human activity recognition,” “wearable sensor,” “accelerometer,” “gyroscope,” “IMU,” “WiFi sensing,” “reinforcement learning,” “sensor attack,” and “temporal perturbation.” The search covered publications from January 2019 through December 2025. Boolean combinations were employed to maximize recall while maintaining precision: (“adversarial” OR “perturbation” OR “attack”) AND (“time series” OR “temporal” OR “sequential”) AND (“classification” OR “recognition” OR “forecasting” OR “reinforcement learning”).

1.4.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria required papers to: (1) propose novel attack or defense methods for temporal or RL systems, (2) provide empirical evaluation on established benchmarks or real-world datasets, (3) be published in peer-reviewed venues or appear as preprints with substantial citation counts, and (4) provide sufficient methodological detail for reproducibility assessment.

Exclusion criteria removed papers that: (1) focused exclusively on image or text domains without temporal components, (2) presented only theoretical analysis without empirical validation, (3) were superseded by extended journal versions from the same authors, (4) lacked quantitative attack success metrics or defense evaluation, or (5) were not available in English.

We additionally applied quality filters prioritizing publications in top-tier venues including IEEE TPAMI, Pattern Recognition, NeurIPS, ICML, ICLR, CVPR, ICCV, AAAI, IJCAI, ACM CCS, USENIX Security, IEEE S&P, ACM UbiComp/IMWUT, IEEE TMC, and ACM MobiCom. For emerging topics with limited top-tier coverage, we included carefully vetted arXiv preprints with verified experimental results and citation counts exceeding 10.

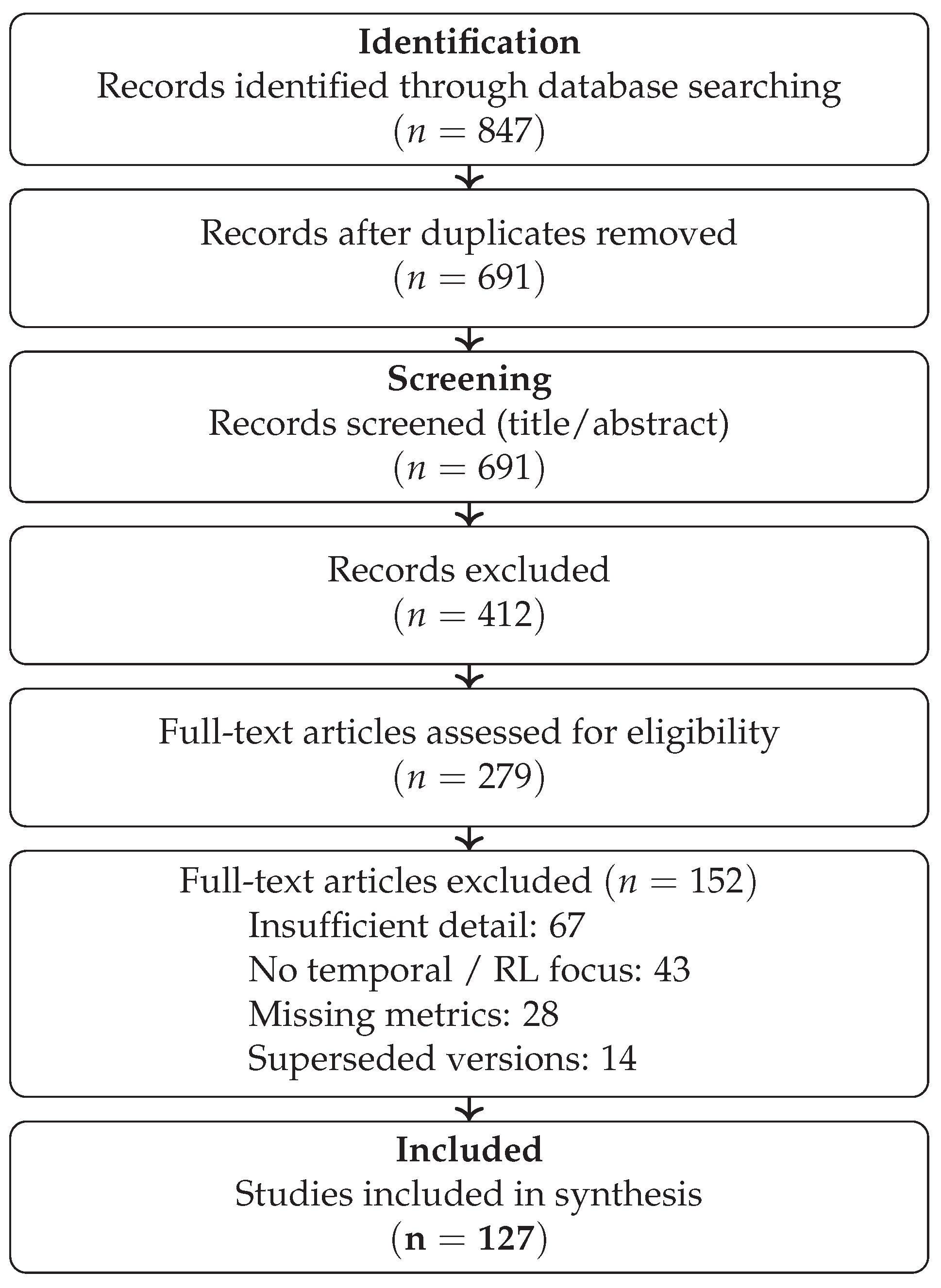

1.4.3. Study Selection Process

Figure 1 illustrates our study selection process following PRISMA guidelines. Initial database searches yielded 847 potentially relevant records. After removing 156 duplicates, 691 records underwent title and abstract screening by two independent reviewers (AK and MGP). Screening disagreements were resolved through discussion, achieving inter-rater agreement of

(Cohen’s kappa), indicating substantial agreement.

Of the 691 screened records, 412 were excluded based on title/abstract review (primarily due to focus on image/NLP domains or lack of empirical evaluation). The remaining 279 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. Of these, 152 were excluded: 67 for insufficient methodological detail, 43 for lack of temporal/RL focus, 28 for missing quantitative metrics, and 14 for being superseded by extended versions.

Our final corpus comprises 127 papers, distributed across time series classification and HAR (42 papers, 33.1%), WiFi and radar sensing (18 papers, 14.2%), skeleton-based recognition (15 papers, 11.8%), medical and financial time series (14 papers, 11.0%), reinforcement learning attacks (23 papers, 18.1%), and defense mechanisms (15 papers, 11.8%).

1.4.4. Risk-of-Bias Assessment

We developed a domain-specific risk-of-bias rubric to assess the quality and reliability of included studies. Each paper was evaluated across four dimensions, scored on a scale of 1 (low quality) to 3 (high quality):

Threat model realism (TMR): Evaluates whether the assumed attacker capabilities are realistic for the target deployment scenario. Score 3: Physically validated attacks with realistic constraints; Score 2: Digital attacks with physical constraints (sensor bounds, smoothness); Score 1: Unconstrained digital attacks assuming direct model input access.

Evaluation rigor (ER): Assesses the comprehensiveness of empirical evaluation. Score 3: Multiple datasets, multiple model architectures, ablation studies, statistical significance testing; Score 2: Single dataset with multiple models or multiple datasets with single model; Score 1: Single dataset, single model, no ablations.

Reproducibility (REP): Evaluates the availability of implementation details and code. Score 3: Open-source code with documented parameters; Score 2: Detailed algorithmic description enabling reimplementation; Score 1: High-level description only.

Baseline comparison (BC): Assesses comparison with prior work. Score 3: Comprehensive comparison with ≥3 recent baselines under identical conditions; Score 2: Comparison with 1-2 baselines; Score 1: No baseline comparison or incomparable setups.

Table 2 summarizes the distribution of risk-of-bias scores across included studies. We observe that threat model realism (mean: 1.7) represents the most significant quality concern, with the majority of studies assuming unrealistic white-box access. Reproducibility has improved in recent years (mean: 2.3 for 2023-2025 vs. 1.8 for 2019-2022), reflecting growing emphasis on open science practices.

1.4.5. Data Extraction and Synthesis

For each included study, we extracted: (1) attack/defense methodology and key algorithmic contributions, (2) target domain and sensor modalities, (3) threat model assumptions, (4) datasets and experimental setup, (5) quantitative results (ASR, robust accuracy, perturbation magnitude), (6) claimed limitations, and (7) code/data availability. Extraction was performed by DLH and verified by AK.

Due to heterogeneity in experimental setups, perturbation budgets, and evaluation protocols across studies, formal meta-analysis was not feasible for most comparisons. Instead, we provide narrative synthesis organized by our taxonomic framework, with quantitative comparisons where methodological alignment permits.

Section 7 presents aggregated findings for comparable experimental conditions.

1.4.6. Limitations of This Review

We acknowledge several limitations of our systematic review:

Selection bias: Prioritization of top-tier venues may exclude relevant work from regional conferences or emerging venues. Rapid developments in LLM-based temporal systems may result in coverage gaps for very recent preprints.

Publication bias: Published studies likely over-represent successful attacks and effective defenses, potentially inflating reported success rates relative to real-world performance.

Heterogeneity: Variation in experimental protocols, perturbation budgets, and evaluation metrics limits quantitative synthesis across studies.

Language bias: Restriction to English-language publications may exclude relevant non-English literature.

Despite these limitations, our systematic approach provides the most comprehensive coverage of temporal adversarial attacks to date, with transparent methodology enabling future updates and extensions.

1.5. Organization

The remainder of this survey is organized as follows.

Section 2 establishes foundational concepts in adversarial attacks and presents our taxonomic framework for temporal systems, with particular attention to sensor-specific characteristics.

Section 3 comprehensively reviews time series adversarial attacks across HAR (with sensor-specific analysis), WiFi/radar sensing, skeleton-based recognition, and financial/medical domains.

Section 4 analyzes RL adversarial attacks including state perturbations, reward poisoning, adversarial policies, and RL-based attack generation.

Section 5 addresses cross-cutting themes including physical realizability, multi-modal vulnerabilities, and certified defenses.

Section 6 discusses defense mechanisms with attention to temporal system requirements.

Section 7 presents evaluation methodologies and benchmark datasets.

Section 8 identifies critical research gaps and future directions.

Section 9 concludes with a synthesis of key findings.

2. Background and Taxonomy

This section establishes the foundational concepts underlying adversarial attacks on temporal systems and introduces our taxonomic framework. We place particular emphasis on the unique characteristics of sensor-based time series data that distinguish it from static image data and necessitate specialized attack and defense methodologies. Critically, we distinguish between fundamentally different sensing paradigms—on-body inertial measurement and device-free RF sensing—that present distinct attack surfaces and defense requirements.

2.1. Adversarial Attack Fundamentals

Adversarial attacks exploit the sensitivity of neural networks to carefully crafted input perturbations. Given a classifier

and a clean input

x with true label

y, an adversarial example

satisfies:

where

is a distance metric and

bounds the perturbation magnitude. We characterize attacks along three primary dimensions: attacker knowledge, attack objectives, and attack timing.

2.1.1. Threat Models Based on Attacker Knowledge

White-box attacks assume complete model access, including architecture, parameters, and gradients. This setting enables gradient-based optimization of perturbations and represents the strongest adversary. In sensor-based HAR systems, white-box attacks are particularly powerful because gradient information can reveal which time steps and sensor channels are most vulnerable to perturbation [

3].

Gray-box attacks assume partial information, such as knowledge of the model architecture without access to trained parameters, or access to a related surrogate model trained on similar data. This threat model is especially relevant for HAR systems where attackers may know the general architecture (e.g., CNN or LSTM) used for activity recognition without having access to the specific trained weights deployed on a target device.

Black-box attacks restrict the adversary to input-output access only. Within this category,

score-based attacks can observe prediction confidence scores, while

decision-based attacks receive only hard classification labels. Black-box attacks on HAR systems face additional challenges because query access may be limited by network connectivity, battery constraints on wearable devices, or rate limiting by cloud-based inference services. Recent advances in query-efficient black-box methods include square-based attacks using simulated annealing that significantly reduce query complexity while maintaining attack effectiveness [

31].

No-box attacks represent a recently introduced paradigm that requires neither model access nor queries. Lu et al. [

33] demonstrated that domain-specific priors—such as natural human motion dynamics for skeleton-based action recognition—can guide attack generation without any interaction with the target model. This paradigm is particularly concerning for deployed HAR systems where attackers can leverage publicly available motion capture datasets to craft transferable attacks.

2.1.2. Attack Objectives

Untargeted attacks aim to cause any misclassification, formally expressed as achieving . For HAR systems, an untargeted attack might cause a “walking” activity to be misclassified as any other activity.

Targeted attacks force a specific misclassification

to an adversary-chosen class. In healthcare monitoring contexts, targeted attacks pose severe risks—for example, causing “fall” activities to be classified as “sitting” could disable emergency response systems [

5].

Universal attacks seek a single perturbation pattern effective across multiple inputs. Recent work has demonstrated universal attacks on millimeter-wave HAR systems achieving greater than 95% success rates with a single learned perturbation pattern [

34]. Universal attacks are particularly threatening for deployed systems because they can be pre-computed offline and applied in real-time without iterative optimization.

2.1.3. Attack Timing

Evasion attacks operate at test time, manipulating inputs to an already-deployed model. The majority of HAR adversarial attacks fall into this category.

Poisoning attacks corrupt training data to influence model behavior, either degrading overall performance or introducing backdoors that trigger on specific inputs. Label flipping attacks against wearable HAR systems have been demonstrated to successfully manipulate MLP, Decision Tree, Random Forest, and XGBoost classifiers during data collection phases [

35]. Backdoor attacks on skeleton-based recognition can embed triggers using infrequent, imperceptible actions that activate malicious behavior during inference [

36]. For autoregressive models, data poisoning attacks can corrupt sequential dependencies, causing cascading prediction failures that persist across multiple forecast horizons [

37].

2.2. Perturbation Constraints for Temporal Data

Adversarial perturbations are typically constrained to preserve imperceptibility. The most common formulation bounds perturbations by

norms:

where

denotes the perturbation and

the perturbation budget.

However,

norms developed for image perturbations are often inadequate for time series data. Belkhouja et al. [

38] demonstrated that Dynamic Time Warping (DTW) provides a more appropriate distance metric for time series because DTW accounts for temporal alignment variations that are natural in human activity data. Their DTW-AR framework achieved superior imperceptibility compared to Euclidean-norm-constrained attacks while maintaining high attack success rates.

Beyond distance metrics, time series attacks must respect additional constraints absent in image attacks:

Signal continuity: Sensor measurements evolve continuously; abrupt discontinuities in accelerometer or gyroscope readings are physically implausible and easily detectable. Pialla et al. [

39,

40] introduced smoothness constraints using Gaussian process priors to ensure perturbations maintain natural signal characteristics.

Measurement bounds: Physical sensors have finite measurement ranges. Accelerometers typically measure to , while gyroscopes measure to degrees per second. Perturbations that exceed these bounds are physically unrealizable.

Inter-sensor correlations: In multi-sensor systems, readings from different sensors (e.g., accelerometer and gyroscope on the same device) are physically correlated. Perturbations that violate these correlations may be detectable by consistency checking [

41].

Energy constraints: For attacks requiring signal injection into wearable devices, battery limitations constrain the total perturbation energy that can be sustained over time.

Probabilistic output constraints: For probabilistic forecasting models that output prediction distributions rather than point estimates, adversarial perturbations must consider both mean predictions and uncertainty estimates. Dang-Nhu et al. [

23] demonstrated that attacks on autoregressive models can exploit the sequential nature of predictions, where perturbations at early time steps propagate through the forecast horizon with amplifying effects.

2.3. Canonical Attack Methods

Several foundational attack methods have been adapted across domains:

Fast Gradient Sign Method (FGSM) [

1] generates perturbations in a single gradient step:

where

denotes the classification loss. While computationally efficient, FGSM attacks on time series often produce perturbations with unnatural spike patterns that violate temporal smoothness [

39].

Projected Gradient Descent (PGD) [

2] extends FGSM through iterative optimization with projection onto the feasible perturbation set:

where

projects onto the

-ball around

x and

is the step size. PGD attacks on HAR systems typically require 10-40 iterations to converge, with attack success rates increasing monotonically with iteration count until saturation [

3].

Carlini-Wagner (C&W) attack [

42] formulates adversarial example generation as constrained optimization:

where

g is an objective function encouraging misclassification and

c balances perturbation magnitude against attack success. C&W attacks typically produce smaller perturbations than PGD but require significantly more computation, making them less practical for real-time attacks on streaming sensor data.

Zeroth-Order Optimization (ZOO) [

43] enables black-box attacks by estimating gradients through finite differences:

where

is the

i-th standard basis vector and

h is a small constant. ZOO attacks require

queries per gradient estimate for

d-dimensional inputs, which can be prohibitive for long time series.

Square Attack and Variants [

31] provide query-efficient black-box attacks through random search in square-shaped regions. Liu et al. demonstrated that combining square-based perturbations with simulated annealing achieves competitive attack success rates on time series classification while requiring significantly fewer queries than gradient estimation methods. This approach is particularly relevant for attacking deployed HAR systems where query budgets are constrained.

2.4. Unique Characteristics of Sensor-Based Time Series

Sensor-based HAR data exhibits several properties that fundamentally distinguish it from image data and necessitate specialized attack methodologies:

Temporal dependencies: Activity patterns unfold over time with characteristic dynamics. Walking exhibits periodic patterns at approximately 1-2 Hz, while transitions between activities involve distinctive acceleration profiles. Perturbations must maintain temporal coherence to remain imperceptible.

Multi-sensor configurations: Modern wearable devices incorporate multiple sensors (accelerometer, gyroscope, magnetometer, barometer) that provide complementary information. Attack effectiveness varies significantly depending on which sensors are perturbed. Kurniawan et al. [

29] demonstrated that adversarial attacks can succeed by compromising only one of three sensor devices in multi-modal systems.

Body placement sensitivity: The same activity produces different sensor signatures depending on device placement (wrist, chest, ankle, hip). Cross-location transferability of attacks varies from 0% to over 80% depending on the specific location pair [

3].

User variability: Different users perform the same activities with individual variations in speed, amplitude, and style. Attacks that transfer across users are more concerning than user-specific attacks, but cross-user transferability is generally lower than within-user attack success.

Sampling rate effects: HAR systems operate at sampling rates from 20 Hz to 200 Hz. Higher sampling rates provide more temporal resolution but also increase the attack surface by providing more individual samples that can be perturbed.

Anomaly detection context: Beyond classification, time series systems increasingly employ anomaly detection for identifying unusual patterns. Tariq et al. [

22] demonstrated that anomaly detection models exhibit distinct adversarial vulnerabilities, where perturbations can cause either false negatives (missed anomalies) or false positives (spurious alerts), each with different operational consequences.

2.5. Emerging Architectural Paradigms

The rapid evolution of deep learning architectures introduces novel vulnerability surfaces that extend beyond conventional CNN and LSTM models:

2.5.1. Spiking Neural Networks for Temporal Data

Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs) are increasingly deployed for time series classification on edge devices due to their energy efficiency and natural temporal processing capabilities. However, Hutchins et al. [

30] demonstrated that SNNs exhibit distinct adversarial susceptibility patterns compared to conventional architectures. Black-box attacks on SNNs for time series data achieve high success rates while exploiting the spike-timing-dependent nature of these networks. The discrete, event-driven nature of SNNs creates attack surfaces absent in continuous-valued networks, necessitating specialized adversarial analysis for neuromorphic deployments.

2.5.2. Large Language Models for Time Series

The application of Large Language Models (LLMs) to time series analysis represents an emerging paradigm with significant security implications. Foundation models including TimeGPT, GPT-4, LLaMA, and Mistral variants have demonstrated competitive performance on forecasting and anomaly detection tasks [

10,

11]. However, these models inherit vulnerabilities from their language model foundations while introducing temporal-specific attack surfaces:

Prompt-based vulnerabilities: LLM-based time series models often rely on textual prompts to specify forecasting tasks, creating injection attack vectors absent in traditional neural architectures.

Tokenization artifacts: The discretization of continuous time series into token sequences introduces quantization boundaries that can be exploited by adversarial perturbations.

Context window limitations: Fixed context lengths may truncate relevant historical information, creating blind spots exploitable by adversaries who can manipulate which portions of time series enter the context window.

Xiao et al. [

12] introduced learning-based attacks specifically targeting temporal forecasting models, demonstrating that adversarial perturbations can manipulate predictions along three dimensions:

directional (bullish vs. bearish bias),

amplitudinal (magnitude of predicted changes), and

temporal (timing of predicted events). These attacks achieve high success rates while maintaining statistical properties that evade conventional anomaly detection.

Alnegheimish et al. [

10] evaluated LLMs as anomaly detectors for time series, revealing that while these models achieve competitive detection performance, their reasoning processes can be manipulated through adversarial examples that exploit the models’ reliance on pattern matching rather than domain-specific physical constraints. This finding suggests that LLM-based temporal systems may be particularly vulnerable to attacks that appear statistically normal but violate domain semantics.

2.6. Taxonomy of Temporal Adversarial Attacks

We organize the surveyed literature along four dimensions that capture the key design choices in temporal adversarial attacks. Critically, we distinguish between on-body sensing and device-free RF sensing paradigms, which present fundamentally different attack surfaces despite both processing temporal data.

Dimension 1: Target domain and sensor modality.

We partition sensing modalities into two fundamental categories based on their physical operating principles:

Category A: On-body inertial and physiological sensing. These systems require physical contact with the subject and measure mechanical or electrical properties directly:

Wearable IMU systems: Attacks targeting accelerometer, gyroscope, and magnetometer sensors on smartphones and dedicated wearables. Attack vectors include direct sensor manipulation, firmware compromise, and electromagnetic interference. Perturbations must respect rigid-body motion dynamics and inter-sensor correlations.

Medical physiological sensors: Attacks on ECG, EEG, EMG, and other bioelectrical signal classifiers. Clinical plausibility constraints require perturbations to maintain physiological realism [

44].

Category B: Device-free RF and vision-based sensing. These systems operate without physical contact, sensing through electromagnetic wave propagation or optical capture:

WiFi CSI sensing: Attacks on channel state information-based recognition systems. These face fundamentally different constraints than IMU attacks: signal processing pipelines include non-differentiable operations (Hampel filtering, phase sanitization) that prevent direct gradient-based optimization [

4]. Physical attacks require RF signal injection synchronized with legitimate WiFi traffic.

Millimeter-wave and FMCW radar: Attacks on 60-77 GHz sensing systems. Attack vectors include active signal injection and passive reflection manipulation using meta-material tags [

8]. Propagation-path constraints differ fundamentally from wearable sensor perturbations.

Skeleton-based recognition: Attacks on pose estimation and skeleton sequence classifiers. Perturbations must maintain anatomical plausibility and natural motion dynamics [

45].

Category C: Financial and industrial time series. These systems process non-physical temporal data with domain-specific constraints:

Category D: Sequential decision systems.

Dimension 2: Perturbation strategy.

Gradient-based: Methods adapting FGSM, PGD, and related techniques for temporal data.

Optimization-based: C&W-style attacks with temporal constraints.

Generative: GAN-based [

47] and diffusion model approaches producing natural-appearing perturbations.

Search-based: Evolutionary algorithms, tree search [

48], square-based random search [

31], and RL policies [

49] for discrete perturbation selection.

Frequency-domain: Attacks manipulating Fourier or wavelet representations of time series.

Learning-based: Neural network-based attack generators that learn perturbation strategies from data, enabling rapid attack generation without iterative optimization at test time [

12].

Dimension 3: Temporal scope.

Point-wise: Independent perturbations at each time step.

Window-wise: Coherent perturbations over contiguous windows.

Sparse: Perturbations targeting only critical time steps identified through attention or gradient analysis.

Global: Single perturbation pattern applied across entire sequences (universal attacks).

Causal/sequential: Perturbations designed to exploit temporal dependencies, where early perturbations influence predictions at later time steps through autoregressive or recurrent mechanisms [

23].

Dimension 4: Physical realizability.

Table 3 summarizes the key differences between sensing modality categories, highlighting the distinct attack surfaces and constraint types that necessitate modality-specific adversarial analysis.

7. Evaluation Methodology

Standardized evaluation methodology is essential for comparing attack and defense methods across studies. This section reviews evaluation metrics, benchmark datasets, and protocols for temporal adversarial research.

7.1. Attack Evaluation Metrics

7.1.1. Standard Metrics

Attack Success Rate (ASR) measures the fraction of adversarial examples that successfully fool the classifier:

Robust Accuracy measures classifier accuracy on adversarial inputs:

Perturbation Magnitude quantifies attack strength, typically using

norms:

Transferability Rate measures attack success when perturbations generated against a surrogate model are applied to a different target model.

7.1.2. Temporal-Specific Metrics

Standard metrics developed for image attacks may not adequately capture attack characteristics for temporal data. We identify several temporal-specific metrics:

DTW Distance: Dynamic Time Warping provides a more perceptually meaningful distance measure for time series than Euclidean distance, accounting for temporal alignment variations [

38]:

Smoothness Score: Quantifies perturbation smoothness to assess detectability [

39]:

Physical Realizability Score (PRS): Measures perturbation feasibility under physical constraints:

Temporal Sparsity: Fraction of time steps with significant perturbation, relevant for attacks targeting critical moments [

80].

7.2. Defense Evaluation Metrics

Beyond robust accuracy, defense evaluation requires additional metrics:

Clean Accuracy Degradation: The accuracy loss on unperturbed inputs after applying defense, measuring the robustness-accuracy trade-off.

Certified Radius: For certified defenses, the maximum perturbation magnitude with provable prediction stability [

98].

Detection Rate / False Positive Rate: For detection-based defenses, the trade-off between catching attacks and incorrectly flagging clean inputs.

Computational Overhead: Training time increase and inference latency, critical for resource-constrained deployments.

7.3. Benchmark Datasets

7.3.1. HAR and Time Series Benchmarks

UCR Archive [

111] comprises 128 univariate time series datasets spanning diverse domains. While valuable for general TSC evaluation, UCR datasets may not fully represent the characteristics of sensor-based HAR data including multi-variate signals, subject variability, and realistic noise patterns.

UCI-HAR [

112] includes smartphone accelerometer and gyroscope data from 30 subjects performing 6 activities. As one of the most widely used HAR benchmarks, UCI-HAR enables comparison across studies but may not capture the complexity of modern multi-sensor wearable systems.

PAMAP2 [

113] provides IMU data from 9 subjects performing 18 activities with sensors on wrist, chest, and ankle. The multi-location sensor configuration enables evaluation of cross-location transferability [

3].

Opportunity [

114] includes 72 sensors monitoring 4 subjects performing activities of daily living. The high sensor density makes Opportunity valuable for evaluating multi-modal fusion vulnerabilities.

MHealth [

115] provides data from 10 subjects with 3 sensor locations, specifically designed for mobile health applications. Kurniawan et al. [

29] demonstrated partial sensor attacks achieving 50-100% success on this dataset.

7.3.2. Skeleton and Video Benchmarks

NTU RGB+D 60/120 [

116] provides 3D skeleton sequences for 60/120 action classes captured with Kinect sensors. The RobustBenchHAR benchmark [

53] standardizes evaluation on NTU datasets with 7 models, 10 attacks, and 2 defenses.

Kinetics-400 [

117] contains 400 human action classes from YouTube videos. While primarily a video dataset, skeleton extraction enables skeleton-based evaluation at scale.

UCF-101 and HMDB-51 provide video action recognition benchmarks with 101 and 51 classes respectively, widely used for video adversarial attack evaluation.

7.3.3. WiFi and Radar Benchmarks

Widar3.0 [

118] provides WiFi CSI data for 22 gesture classes from 16 users across 3 environments. WiAdv [

4] demonstrated physically realizable attacks achieving >70% success on Widar3.0.

SignFi [

119] provides WiFi CSI data for sign language recognition, enabling evaluation of fine-grained gesture attacks.

7.3.4. Medical Benchmarks

PhysioNet 2017 [

120] provides ECG data for arrhythmia classification, used for evaluating attacks on cardiac monitoring systems [

44,

70].

CHB-MIT [

121] provides EEG data for seizure detection, enabling evaluation of BCI adversarial attacks [

73,

75].

7.3.5. RL Benchmarks

Atari provides discrete-action game environments for evaluating state perturbation attacks on DQN agents.

MuJoCo provides continuous control tasks for evaluating attacks on PPO, SAC, and DDPG agents.

Safety Gym [

122] provides constrained RL environments for evaluating attacks on safety-critical systems.

D4RL [

123] provides offline RL benchmarks for evaluating reward poisoning attacks on offline learning [

91].

7.4. Evaluation Protocols

We identify several evaluation protocol considerations for temporal adversarial research:

AutoAttack adaptation: The AutoAttack protocol [

110], standard for image robustness evaluation, requires adaptation for time series. The ensemble of AutoPGD-CE, AutoPGD-DLR, FAB, and Square Attack should be configured with temporal-appropriate perturbation constraints.

Adaptive attack evaluation: Following Tramer et al. [

109], defenses should be evaluated against adaptive attacks specifically designed to defeat them. Claims of defense effectiveness against standard attacks may not generalize to adaptive adversaries.

Cross-dataset evaluation: Given the domain shift between HAR datasets [

3], attacks and defenses should be evaluated on multiple datasets to assess generalization.

Physical validation requirements: For attacks claiming physical realizability, evaluation should include hardware-in-the-loop validation beyond digital simulation.

7.5. Proposed Unified Benchmark Suite

The absence of standardized evaluation protocols prevents direct comparison across studies and hinders progress assessment. We propose a unified benchmark suite for temporal adversarial research, specifying dataset configurations, attack parameters, and evaluation procedures.

7.5.1. Standardized Dataset Configurations

Table 13 specifies fixed train-test splits and preprocessing for representative datasets. Adopting these configurations enables apples-to-apples comparison across studies.

7.5.2. Standardized Attack Parameters

We specify common attack budgets to enable cross-study comparison.

Table 14 defines perturbation constraints for different modalities.

Attack algorithm configurations:

PGD: 40 iterations, step size , random start.

C&W: Binary search over , 1000 iterations.

AutoAttack: Standard configuration with temporal adaptations.

Black-box: Maximum 10,000 queries for score-based; 20,000 for decision-based.

7.5.3. Sequence Length Handling

Variable sequence lengths in temporal data require standardized handling protocols:

Fixed-length datasets (HAR): Use dataset-specific window sizes as specified in

Table 13. Report results separately for different window configurations if exploring this dimension.

Variable-length datasets (Skeleton, Video):

Padding approach: Zero-pad to maximum length in batch; mask padded positions in attention.

Truncation approach: Truncate to fixed length (e.g., 300 frames for NTU).

Sampling approach: Uniform temporal sampling to fixed number of frames.

Report which approach is used; compare attack effectiveness across approaches if evaluating this dimension.

Padding attacks: Following Ozbulak et al. [

6], evaluate whether attacks can succeed by perturbing only padding regions without modifying actual data. Report padding-only ASR separately.

7.5.4. Evaluation Reporting Template

We provide a standardized reporting template for temporal adversarial research. Papers should include

Table 15 or equivalent:

7.6. Domain-Specific Metrics Enhancement

Beyond the temporal-specific metrics introduced in

Section 7, we identify additional domain-specific metrics that capture modality-specific attack characteristics.

7.6.1. Frequency-Domain Metrics

Time-frequency analysis reveals attack characteristics invisible in time-domain metrics:

Spectral Energy Ratio (SER): Measures perturbation energy distribution across frequency bands [

124]:

where

is the wavelet or Fourier coefficient at frequency

f, and

is the frequency band characteristic of human activities (typically 0.5–20 Hz for HAR). Attacks concentrating energy outside activity bands may be more detectable.

Wavelet Coherence: Quantifies time-frequency consistency between original and perturbed signals. Wavelet-domain HAR systems [

124] may exhibit different vulnerability patterns than time-domain systems.

7.6.2. Multi-Sensor Consistency Metrics

Cross-Sensor Correlation Preservation (CSCP): Measures whether perturbations maintain expected inter-sensor relationships:

where

denotes correlation,

and

are accelerometer and gyroscope signals respectively. CSCP near 1.0 indicates perturbations preserve sensor consistency; low CSCP suggests detectability by consistency-based defenses.

Rigid-Body Constraint Violation (RBCV): For IMU data, measures whether perturbed signals violate rigid-body motion dynamics:

where

is the rotation implied by gyroscope readings. Non-zero RBCV indicates physically implausible perturbations.

7.6.3. Activity-Specific Metrics

Confusion-Weighted ASR: Weights attack success by semantic severity of misclassification. Causing “fall” to be classified as “sit” is more severe than “walk” to “run”:

where

is the number of class

i samples misclassified as class

j, and

is the severity weight for this confusion pair.

Temporal Expert Confusion: For mixture-of-experts architectures [

125], measures whether attacks cause routing errors to inappropriate temporal experts, distinct from final classification errors.

7.6.4. RL-Specific Metrics

Cumulative Reward Degradation: For RL attacks, measures total reward loss over episodes:

Safety Violation Rate: For safety-constrained RL [

122], measures the fraction of episodes where attacks cause constraint violations:

where

is the constraint cost in episode

e.

Policy Entropy Change: Measures whether attacks cause policy to become more uncertain:

Positive indicates attacks inducing policy confusion rather than confident wrong actions.

7.7. Quantitative Synthesis of Attack Effectiveness

While heterogeneity in experimental setups limits formal meta-analysis, we present aggregated findings for studies with comparable methodological conditions.

Table 16 summarizes attack success rates stratified by modality, attack type, and validation level.

Key findings from quantitative synthesis:

(1) White-box attacks achieve near-complete success across modalities. Under white-box threat models with unconstrained perturbations, ASR consistently exceeds 85% across all sensor modalities, with robust accuracy dropping below 20%. This highlights the theoretical vulnerability of temporal systems but may overstate practical risk given unrealistic threat assumptions.

(2) Physical validation significantly reduces reported success rates. Studies with hardware-in-the-loop validation report ASR 10–20% lower than digital-only evaluations on comparable tasks, suggesting that physical constraints meaningfully limit attack effectiveness.

(3) Cross-sensor and cross-user transferability exhibits high variance. Transfer attack success varies from near 0% to over 80% depending on source-target pairs, indicating that transferability patterns are not yet well understood and represent a critical research gap.

(4) Defense effectiveness remains inconsistent. Adversarial training reduces ASR by 30–60% but incurs 5–15% clean accuracy degradation. Certified defenses provide provable guarantees but with 15–30% accuracy cost, limiting practical deployment.

These findings should be interpreted with caution given methodological heterogeneity. We encourage future work to adopt standardized evaluation protocols (

Section 7.4) to enable more rigorous quantitative synthesis.

8. Research Gaps and Future Directions

Our systematic review identifies eight critical research gaps that define priority directions for advancing adversarial robustness in temporal systems. For each gap, we provide concrete research questions, potential approaches informed by recent advances, and specific datasets and evaluation pipelines for operationalization.

Table 17 presents a prioritization framework based on research impact and implementation feasibility.

8.1. Research Gap Prioritization Framework

We prioritize the eight identified research gaps along two dimensions: (1) Research Impact—the potential contribution to advancing adversarial robustness in temporal systems, considering both theoretical novelty and practical relevance; and (2) Implementation Feasibility—the availability of datasets, computational resources, and methodological foundations required for investigation.

Priority 1 (P1) gaps represent high-impact research directions with strong feasibility due to available datasets and established methodological foundations. These should be prioritized for immediate investigation.

Priority 2 (P2) gaps offer significant impact potential but face methodological or computational challenges requiring foundational work before full investigation.

Priority 3 (P3) gaps represent important long-term research directions that currently lack necessary infrastructure (hardware testbeds, standardized multi-agent environments) but will become increasingly relevant as the field matures.

8.2. Gap 1: XAI-Guided Attacks for Temporal Systems

No framework exists systematically using explainability techniques to guide adversarial attack generation for HAR systems. Key research questions include:

Q1.1: How can temporal attention patterns in transformer-based HAR reveal susceptible time windows? Recent work [

126] shows transformers are more vulnerable than CNNs/LSTMs for HAR, but the relationship between attention mechanisms and adversarial susceptibility remains unexplored.

Q1.2: Can SHAP or LIME attributions identify sensor channels that contribute weakly to classification but are highly vulnerable to perturbation?

Q1.3: Do robust vs. non-robust features identified via explainability transfer across activities and subjects?

Potential approach: Develop XAI-guided attack frameworks that compute feature attributions, identify low-importance high-vulnerability features, and concentrate perturbations accordingly. This could yield more efficient attacks requiring smaller perturbation budgets.

Recommended evaluation pipeline:

Train baseline HAR models on UCI-HAR, PAMAP2, and NTU-60 datasets.

Compute temporal and channel-wise SHAP/LIME attributions for test samples.

Generate XAI-guided attacks concentrating perturbations on low-attribution regions.

Compare ASR vs. perturbation budget against uniform and gradient-based baselines.

Evaluate transferability of identified vulnerability patterns across subjects and activities.

8.3. Gap 2: Sensor-Targeted Optimization

Cross-sensor transferability varies dramatically (0–80%) [

3,

29], yet no work strategically exploits these patterns. Unexplored dimensions include:

Q2.1: Can multi-modal coordinated attacks simultaneously perturbing accelerometer, gyroscope, and magnetometer achieve higher success than single-sensor attacks while evading consistency-based detection [

41]?

Q2.2: How do body-location-aware strategies adapting perturbations to sensor placement affect attack effectiveness?

Q2.3: At what fusion layer (early, late, attention-based) are multi-modal HAR systems most vulnerable?

Potential approach: Develop attack optimization frameworks that jointly consider sensor modality, body placement, and fusion architecture to maximize attack effectiveness while minimizing detectability.

Recommended evaluation pipeline:

Use PAMAP2 and MHealth datasets with all sensor modalities at multiple body locations.

Construct transfer matrices measuring ASR retention across all modality pairs.

Implement coordinated attacks maintaining inter-sensor correlations (CSCP > 0.9).

Evaluate evasion of consistency-based detection [

41].

Compare attack effectiveness across early, late, and attention-based fusion architectures.

8.4. Gap 3: RL Attacks on Non-RL Systems

RL-based adversarial research almost exclusively targets RL agents. Application to attack DNNs for HAR, time series classification, and forecasting remains virtually unexplored despite natural fit:

Q3.1: Can RL policies learn attack strategies that transfer across HAR models and datasets, addressing the transferability challenge?

Q3.2: How should reward functions encode physical realizability, imperceptibility, and energy constraints for HAR attacks?

Q3.3: Can RL-based attacks learn to defeat specific defenses through continued learning during attack deployment?

Potential approach: Formulate HAR adversarial attack generation as a sequential decision problem where the RL agent selects which time steps and sensors to perturb, with rewards encoding attack success and constraint satisfaction.

Recommended evaluation pipeline:

Define MDP: states = (current perturbation, model confidence), actions = (timestep, sensor, magnitude), rewards = weighted combination of success and constraints.

Train RL attack policies using PPO/SAC on UCI-HAR and Widar3.0.

Evaluate transfer to unseen models and datasets without retraining.

Test continued learning against adaptive defenses over multiple attack-defense iterations.

Compare query efficiency against gradient-based and search-based baselines.

8.5. Gap 4: Temporal Attack Sophistication

Time series attacks predominantly apply spatial methods frame-by-frame without exploiting temporal structure. Missing capabilities include:

Q4.1: How can attacks optimize perturbations considering causal effects on predictions 10–100 timesteps in the future?

Q4.2: Can attacks identify “critical moments” in activity sequences where perturbations have maximum impact?

Q4.3: How do temporal transferability patterns between activities (e.g., walking→running vs. walking→sitting) affect attack design?

Potential approach: Develop recurrent attack generators that model temporal dependencies in perturbation effectiveness, enabling lookahead optimization for sequential data.

Recommended evaluation pipeline:

Use UCR Archive (long sequences) and NTU-120 (variable-length skeleton) datasets.

Implement critical timestep identification using gradient magnitude over time.

Develop lookahead attack optimization considering future prediction impacts.

Compare sparse (critical-only) vs. dense perturbation strategies on ASR vs. sparsity trade-off.

Construct activity-pair transfer matrices to characterize temporal transferability patterns.

8.6. Gap 5: Transformer Vulnerabilities

Leite et al. [

126] demonstrate transformer-based HAR models show lower robustness than CNNs/LSTMs, but detailed vulnerability analysis is lacking:

Q5.1: Which attention heads are most vulnerable to adversarial manipulation?

Q5.2: Can multi-head exploitation strategies target specific attention patterns to amplify attack effectiveness?

Q5.3: How do positional encoding mechanisms create attack vectors absent in CNN/LSTM architectures?

Potential approach: Develop transformer-specific attacks that analyze and exploit attention patterns, informed by the sharp minima hypothesis underlying transformer vulnerability.

Recommended evaluation pipeline:

Train transformer, CNN, and LSTM models on UCI-HAR, NTU-60, and Widar3.0 for controlled comparison.

Analyze attention head vulnerability through head-ablation and gradient attribution studies.

Develop attention-targeted attacks manipulating specific heads identified as vulnerable.

Compare robust accuracy degradation curves across architectures under T-AutoAttack.

Investigate positional encoding manipulation as a transformer-specific attack vector.

8.7. Gap 6: Certified Temporal Defenses

Certified defense methods assuming i.i.d. data require extension to temporal data. Despite recent advances [

99,

100], significant challenges remain:

Q6.1: How can certification methods handle sequential dependencies where perturbations at time t affect predictions at time ?

Q6.2: Can certified radii be efficiently computed for variable-length sequences exceeding 1000 timesteps?

Q6.3: How should certification methods handle DTW-based perturbation constraints rather than norms?

Potential approach: Develop temporal certification methods that propagate robustness guarantees through recurrent computation, potentially leveraging interval bound propagation or abstract interpretation.

Recommended evaluation pipeline:

Extend randomized smoothing to handle temporal correlations using autoregressive noise models.

Evaluate on UCR Archive and UCI-HAR with sequence lengths from 100 to 2000 timesteps.

Report certified radius vs. clean accuracy trade-off curves.

Measure computational scalability: certification time vs. sequence length.

Compare , , and DTW-based certification approaches.

8.8. Gap 7: Physical Attack Validation

Only WiFi CSI [

4,

50] and radar attacks [

8,

62] have undergone rigorous physical validation. IMU and medical time series attacks remain largely theoretical:

Q7.1: What hardware capabilities are required to inject adversarial perturbations into wearable IMU sensors?

Q7.2: How do environmental factors (temperature, electromagnetic interference, motion artifacts) affect physical attack success rates?

Q7.3: Would physical attacks be detected by standard sensor quality monitoring systems?

Potential approach: Establish hardware-in-the-loop testbeds for systematic physical attack validation across sensor modalities, with standardized evaluation protocols for reproducibility.

Recommended testbed specifications:

IMU testbed: Controllable vibration platform, EMI injection equipment, reference IMU for ground truth, environmental chamber for temperature/humidity variation.

WiFi testbed: Software-defined radio (USRP), multiple access points, RF shielded chamber, mobility platform for controlled subject motion.

Radar testbed: mmWave radar (TI AWR1642), meta-material tag fabrication capability, anechoic chamber, outdoor test area.

Evaluation protocol: Measure ASR with 95% CI across ≥100 trials per condition, report environmental parameters, include detection analysis.

8.9. Gap 8: Multi-Agent and RLHF Poisoning Scenarios

Growing relevance in autonomous vehicles, multi-robot systems, and LLM alignment demands investigation of coordinated attacks and poisoning scenarios:

Q8.1: How do adversarial perturbations propagate through multi-agent communication channels?

Q8.2: What game-theoretic equilibria emerge in adversarial multi-agent scenarios?

Q8.3: Can collective defense mechanisms provide robustness beyond individual agent defenses?

Potential approach: Extend adversarial policy research [

85,

87] to realistic multi-agent HAR scenarios such as collaborative activity recognition in smart spaces.

8.9.1. RLHF Poisoning Connections to Safety-Critical Systems

Recent advances in RLHF poisoning attacks [

93] have significant implications for safety-critical temporal systems that we highlight explicitly:

Connection to Safety Gym benchmarks: Safety Gym [

122] provides constrained RL environments where agents must maximize reward while satisfying safety constraints. RLHF poisoning can corrupt the learned reward model underlying safety constraints, potentially causing agents to violate safety requirements while believing they are acting safely. This creates a particularly insidious attack vector for autonomous systems.

Implications for D4RL offline datasets: Standard offline RL datasets such as D4RL [

123] are increasingly used for training policies without online interaction. Xu et al. [

91] demonstrated universal reward poisoning attacks on offline RL that:

Corrupt apparent rewards of high-performing trajectories to appear low-quality.

Corrupt apparent rewards of low-performing trajectories to appear high-quality.

Cause offline algorithms to learn suboptimal or dangerous policies from poisoned data.

These attacks are particularly concerning because:

Persistence: Poisoned datasets remain corrupted indefinitely, affecting all models trained on them.

Scalability: A single poisoning attack affects all downstream users of the dataset.

Detectability: Subtle reward modifications may not trigger obvious anomalies during dataset inspection.

Safety implications: Corrupted safety constraints in RLHF-trained models may not manifest until deployment in safety-critical scenarios.

Recommended evaluation pipeline for RLHF/offline RL security:

Evaluate reward poisoning attacks on Safety Gym (PointGoal, CarGoal, DoggoGoal) with constraint violation as primary metric.

Test offline RL poisoning on D4RL locomotion and manipulation tasks.

Measure attack transferability across offline algorithms (CQL, IQL, TD3+BC).

Develop detection methods for reward corruption in offline datasets.

Propose certification methods for offline RL with provable robustness to bounded reward perturbation.

8.10. Summary of Prioritized Research Agenda

Based on our gap analysis and prioritization framework, we recommend the following phased research agenda:

Phase 1 (Year 1): Focus on P1 gaps (G1, G2, G5) where datasets and methodological foundations exist. Establish XAI-guided attack frameworks, characterize cross-modal transfer patterns, and systematically analyze transformer vulnerabilities.

Phase 2 (Years 1–2): Address P2 gaps (G3, G4, G6) requiring methodological development. Develop RL-based attack generation, temporal attack sophistication, and extend certified defenses to temporal data.

Phase 3 (Years 2–3): Tackle P3 gaps (G7, G8) requiring infrastructure development. Establish physical attack testbeds, develop multi-agent adversarial evaluation environments, and address RLHF poisoning implications for safety-critical systems.

This phased approach ensures that foundational work enables subsequent investigation, while prioritizing gaps with immediate impact potential.

9. Conclusion

This survey provides the first comprehensive treatment of adversarial attacks on time series and reinforcement learning systems, systematically reviewing 127 papers published between 2019 and 2025. Our analysis reveals both the severity of temporal system vulnerabilities and the substantial gaps in current understanding and defense capabilities.

9.1. Principal Findings

Our systematic review yields seven principal findings, each supported by quantitative evidence synthesized across included studies:

Finding 1: Severe baseline vulnerability. Deep learning models for HAR exhibit extreme vulnerability to adversarial attacks under white-box conditions. FGSM attacks reduce DNN accuracy from 95.1% to 3.4% and CNN accuracy from 93.1% to 16.8% [

3]. However, these results must be interpreted within their threat model context—white-box attacks with unconstrained perturbations represent theoretical upper bounds rather than practical threat levels (

Section 5).

Finding 2: High variability in cross-domain transfer. Attack transferability varies dramatically across dimensions. Cross-model transfer exceeds 70% for similar architectures, but cross-location transfer ranges from 0% to 80% depending on body placement, and cross-user transfer is generally lower than within-user success [

3,

29]. This variability creates both challenges (unpredictable attack success) and opportunities (exploitable for defense design) (

Section 3).

Finding 3: Physical attack validation gap. A critical disparity exists between digital attack success rates (85–98%) and physically validated attacks. Only WiFi/radar modalities have demonstrated hardware-in-the-loop validation, achieving 70–97% success rates in controlled conditions [

4,

8]. Wearable IMU physical attacks remain entirely unvalidated, suggesting that immediate threat levels for wearable HAR may be lower than digital results imply (

Section 5,

Table 8).

Finding 4: Defense effectiveness under adaptive attacks. Current defenses show significant degradation when evaluated against adaptive adversaries. Our analysis reveals 6–23% performance gaps between standard and adaptive attack evaluations across defense categories, with certified defenses exhibiting the smallest gap (6%) and lightweight augmentation methods showing the largest (23%) (

Section 6,

Table 12).

Finding 5: Architecture-dependent vulnerability. Transformer-based HAR models demonstrate lower adversarial robustness than CNN and LSTM alternatives despite competitive clean accuracy [

126]. This finding has important implications for security-sensitive deployments where transformer architectures are increasingly adopted (

Section 5).

Finding 6: Emerging LLM-based temporal system risks. The rapid adoption of large language models for time series forecasting and anomaly detection introduces novel vulnerability surfaces including prompt injection, tokenization exploitation, and context window manipulation [

10,

12]. Security analysis has not kept pace with deployment, creating urgent research needs (

Section 2).

Finding 7: RL system compounding vulnerabilities. Reinforcement learning systems face unique sequential vulnerabilities where perturbations at early timesteps compound through decision trajectories. Adversarial policies achieve >95% success against trained agents [

85], and reward poisoning can corrupt offline learning from standard datasets [

91] (

Section 4).

9.2. Key Contributions

This survey contributes:

Unified taxonomy spanning HAR (IMU, WiFi, radar, skeleton), medical/financial time series, and RL systems, with explicit distinction between on-body and device-free sensing paradigms.

Systematic analysis of 127 papers with PRISMA-compliant methodology, risk-of-bias assessment, and transparent inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Quantitative synthesis of attack effectiveness across modalities, validation levels, and threat models, enabling evidence-based threat assessment.

Defense evaluation framework including adaptive attack benchmarks (T-AutoAttack) and clear distinction between provable certification and implicit robustness approaches.

Prioritized research roadmap identifying eight critical gaps with specific datasets, evaluation pipelines, and implementation timelines.

9.3. Recommendations for Practitioners

Based on our analysis, we offer the following recommendations for deploying HAR and RL systems in security-sensitive contexts:

For wearable HAR deployments: The gap between theoretical vulnerability and physical attack validation suggests that immediate threat levels may be manageable. Prioritize detection-based defenses exploiting multi-sensor consistency [

41], and avoid transformer architectures in favor of CNN/LSTM alternatives until transformer robustness improves.

For WiFi/radar sensing deployments: Physical attacks have been demonstrated with 70–97% success, warranting serious security consideration. Deploy defense-in-depth combining adversarial training with anomaly detection, and monitor RF environments for attack signatures.

For RL system deployments: Adversarial policy and reward poisoning attacks pose significant risks. Employ ensemble methods for observation robustness [

108], validate offline datasets for reward corruption before training, and consider certified approaches for safety-critical applications.

For LLM-based temporal systems: Exercise caution in deploying LLM-based forecasters and anomaly detectors in security-sensitive contexts until adversarial robustness properties are better understood. Monitor for prompt injection and ensure robust preprocessing of temporal inputs.

9.4. Limitations of This Survey

We acknowledge several limitations that should inform interpretation of our findings:

Scope limitations: Our focus on HAR, time series classification, and RL excludes related domains such as speech recognition, video understanding beyond skeleton-based methods, and autonomous vehicle perception systems. These domains share temporal characteristics but may exhibit distinct vulnerability patterns.

Selection bias: Prioritization of top-tier venues may exclude relevant work from regional conferences or emerging venues. The rapidly evolving nature of LLM-based temporal systems means that very recent developments may not be captured.

Publication bias: Published studies likely over-represent successful attacks and effective defenses, potentially inflating reported success rates relative to real-world performance.

Quantitative synthesis limitations: Heterogeneity in experimental protocols, perturbation budgets, and evaluation metrics limited our ability to conduct formal meta-analysis. The quantitative synthesis presented should be interpreted as indicative ranges rather than precise estimates.

Evolving threat landscape: Adversarial machine learning is a rapidly evolving field. Findings regarding current defense effectiveness may not generalize to future attack methodologies, particularly as adaptive attacks become more sophisticated.

9.5. Future Research Priorities

Our gap analysis identifies immediate priorities aligned with the seven principal findings:

(1) XAI-guided attacks and transformer vulnerabilities (addressing Findings 1, 5) represent high-impact, high-feasibility research directions with available datasets and methodological foundations.

(2) Sensor-targeted optimization and cross-modal transfer characterization (addressing Finding 2) will enable both more effective attacks and more targeted defenses.

(3) Physical attack validation for wearable IMU (addressing Finding 3) is essential for accurate threat assessment in the most widely deployed HAR modality.

(4) Adaptive attack evaluation and certified temporal defenses (addressing Finding 4) will establish reliable defense benchmarks and provable robustness guarantees.

(5) LLM temporal system security (addressing Finding 6) requires urgent attention given rapid deployment outpacing security analysis.

(6) RLHF poisoning and offline RL security (addressing Finding 7) has implications extending beyond RL to foundation model safety.

9.6. Closing Remarks

The proliferation of deep learning in safety-critical temporal applications—from healthcare monitoring to autonomous navigation to algorithmic trading—makes adversarial robustness a paramount concern. Our systematic review reveals a field with substantial progress in characterizing vulnerabilities, emerging defense mechanisms, and growing awareness of the gap between theoretical and practical threats.

However, significant challenges remain. The disparity between digital and physical attack validation, the vulnerability of emerging architectures (transformers, LLMs), and the absence of standardized evaluation protocols collectively impede progress toward deployable robust systems.

We hope this comprehensive survey catalyzes research addressing these critical gaps, ultimately contributing to temporal systems that are both capable and secure. The prioritized research roadmap and evaluation frameworks we provide offer concrete starting points for advancing this essential agenda.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for systematic literature selection. Inter-rater agreement for screening: .

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for systematic literature selection. Inter-rater agreement for screening: .

| Insufficient detail: 67 |

| No temporal / RL focus: 43 |

| Missing metrics: 28 |

| Superseded versions: 14 |

Table 1.

Systematic comparison with representative adversarial attack surveys (2019–2025). This survey uniquely addresses sensor-specific vulnerabilities in HAR systems and the intersection of time series and RL attack methodologies.

Table 1.

Systematic comparison with representative adversarial attack surveys (2019–2025). This survey uniquely addresses sensor-specific vulnerabilities in HAR systems and the intersection of time series and RL attack methodologies.

| Survey |

Year |

Scope |

Primary Focus |

Gaps Addressed Here |

| Qiu et al. [17] |

2025 |

CV |

10-year retrospective, LVLMs |

No temporal/RL/sensor coverage |

| Costa et al. [16] |

2024 |

CV |

DL attacks/defenses, ViT |

Limited to static images |

| Pawlicki et al. [21] |

2025 |

General |

Meta-survey, diffusion models |

Lacks domain-specific depth |

| Ilahi et al. [28] |

2024 |

RL |

Attacks and countermeasures |

No time series/sensor integration |

| Schott et al. [26] |

2024 |

RL |

Observation/dynamics attacks |

No TS/HAR integration |

| Goyal et al. [19] |

2023 |

NLP |

Defense mechanisms |

No temporal/sensor data focus |

| Sakka et al. [5] |

2023 |

HAR |

Medical IoT vulnerabilities |

Limited attack methodology analysis |

| Sah & Ghasemzadeh [3] |

2019 |

HAR |

Transferability analysis |

Single-domain, no RL coverage |

| This Survey |

2025 |

TS+RL |

Unified temporal/sequential with sensor-specific analysis |

First comprehensive HAR+RL survey |